Reconnu pour son ouvrage La psychologie des foules prophétisant dès 1895 les mécanismes psychologiques sur lesquels se sont appuyés les régimes totalitaires du XXe siècle et les démocraties modernes, Gustave Le Bon s’est aussi intéressé aux racines historiques des psychologies collectives. Médecin et psychologue mais également anthropologue passionné par les civilisations orientales, ce penseur français était convaincu que chaque peuple est doté d’une âme propre, garante du maintien de son identité collective à travers les siècles.

Gustave Le Bon affirme que l’évolution des institutions politiques, des religions ou des idéologies n’est qu’un leurre. Malgré des changements superficiels, une même âme collective continuerait à s’exprimer sous des formes différentes. Farouche opposant du socialisme de son époque, Gustave Le Bon ne croit pas pour autant au rôle de l’individu dans l’histoire. Il conçoit les peuples comme des corps supérieurs et autonomes dont les cellules constituantes sont les individus. La courte existence de chacun s’inscrit par conséquent dans une vie collective beaucoup plus longue. L’âme d’un peuple est le résultat d’une longue sédimentation héréditaire et d’une accumulation d’habitudes ayant abouti à l’existence d’un « réseau de traditions, d’idées, de sentiments, de croyances, de modes de penser communs » en dépit d’une apparente diversité qui subsiste bien sûr entre les individus d’un même peuple. Ces éléments constituent la synthèse du passé d’un peuple et l’héritage de tous ses ancêtres : « infiniment plus nombreux que les vivants, les morts sont aussi infiniment plus puissants qu’eux » (lois psychologiques de l’évolution des peuples). L’individu est donc infiniment redevable de ses ancêtres et de ceux de son peuple.

Gustave Le Bon affirme que l’évolution des institutions politiques, des religions ou des idéologies n’est qu’un leurre. Malgré des changements superficiels, une même âme collective continuerait à s’exprimer sous des formes différentes. Farouche opposant du socialisme de son époque, Gustave Le Bon ne croit pas pour autant au rôle de l’individu dans l’histoire. Il conçoit les peuples comme des corps supérieurs et autonomes dont les cellules constituantes sont les individus. La courte existence de chacun s’inscrit par conséquent dans une vie collective beaucoup plus longue. L’âme d’un peuple est le résultat d’une longue sédimentation héréditaire et d’une accumulation d’habitudes ayant abouti à l’existence d’un « réseau de traditions, d’idées, de sentiments, de croyances, de modes de penser communs » en dépit d’une apparente diversité qui subsiste bien sûr entre les individus d’un même peuple. Ces éléments constituent la synthèse du passé d’un peuple et l’héritage de tous ses ancêtres : « infiniment plus nombreux que les vivants, les morts sont aussi infiniment plus puissants qu’eux » (lois psychologiques de l’évolution des peuples). L’individu est donc infiniment redevable de ses ancêtres et de ceux de son peuple.

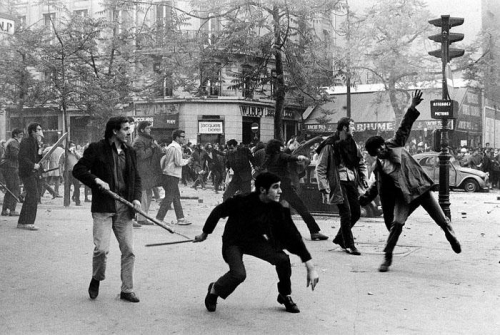

Le psychologue français prétend que les événements historiques ne sont capables de modifier que les qualités accessoires d’un peuple mais n’altèrent pas son âme. Même soumis à des événements violents et de grande envergure, les peuples retournent inéluctablement à leurs aspirations profondes « comme la surface d’un lac après un orage ». Tant qu’elles ne s’attaquent pas à la substance même d’un peuple, les ruptures historiques ne sont donc que superficielles. Le système français jacobin s’est par exemple révélé tout autant centralisateur, autoritaire et despotique que la monarchie française qu’il prétendait détruire. Pour Gustave Le Bon, les institutions de la Révolution française se conformaient à la réalité de l’âme du peuple français, peuple majoritairement latin favorable à l’absorption de l’individu par l’état. Peuple également enclin à rechercher l’homme providentiel à qui se soumettre et que Napoléon incarna. D’une toute autre mentalité, le peuple anglais a construit son âme autour de l’amour de la liberté. Gustave Le Bon rappelle comment ce peuple anglais a refusé à travers les siècles les dominations et ingérences étrangères avec les rejets successifs du droit romain et de l’Eglise catholique. Ce goût de l’indépendance et du particularisme résonne jusqu’à nos jours à travers les relations conflictuelles qu’entretient l’Angleterre avec le continent européen. Ces réflexions amènent Le Bon à juger sévèrement l’idéal colonial de son temps en ce qu’il prône l’imposition d’institutions politiques et d’idéologies à des peuples qui y sont étrangers. S’opposant frontalement à l’héritage des penseurs des Lumières et à leur quête du système politique parfait et universel, il estime que de bonnes institutions politiques sont avant tout celles qui conviennent à la mentalité profonde du peuple concerné.

La dilution des religions dans l’âme des peuples

La dilution des religions dans l’âme des peuples

Pour l’essentiel, l’âme des peuples reste également insensible aux révolutions religieuses. La conversion d’un peuple à une nouvelle religion se traduit le plus souvent avec le temps par l’adaptation de celle-ci aux aspirations profondes du peuple converti. Fasciné par la civilisation indienne, Gustave Le Bon rappelle que l’islam, religion égalitaire, n’est jamais parvenu à remettre en question durablement le système des castes en Inde. L’islam encore n’a pas imposé la polygamie orientale aux populations berbères pourtant converties depuis des siècles. De même, le catholicisme s’est très largement laissé imprégner par les traditions païennes européennes, dissimulant souvent par une christianisation de forme les concessions faites aux croyances des peuples convertis. C’est encore par l’âme des peuples concernés que Gustave Le Bon explique la naissance du protestantisme en pays germaniques et les succès de la religion réformée dans le nord de l’Europe. Amoureux de liberté individuelle, d’autonomie et d’indépendance, ces peuples nordiques et germaniques étaient enclins à discuter individuellement leur foi et ne pouvaient accepter durablement la médiation de l’Eglise que la servilité latine était plus propice à accepter. Dans la civilisation de l’Inde, l’anthropologue français explique également comment le bouddhisme indien, issu d’une révolution religieuse, a peu à peu été absorbé par l’hindouisme, religion charnelle des peuples indiens et de leurs élites indo-iraniennes.

Chaque peuple fait apparaître les particularités de son âme dans des domaines différents. La religion, les arts, les institutions politiques ou militaires sont autant de terrains sur lesquels une civilisation peut atteindre l’excellence et exprimer le meilleur de son âme. Convaincu de la capacité instinctive des artistes à traduire l’âme d’un peuple, Gustave Le Bon accorde un intérêt particulier à l’analyse des arts. Il remarque que les romains ont peiné à développer un art propre mais se sont distingués par leurs institutions politiques et militaire et leur littérature. Cependant, même dans leur architecture largement inspirée par la Grèce, les romains exprimaient une part d’eux mêmes. Les palais, les bas reliefs et les arcs de triomphe romains incarnaient le culte de la force et la passion militaire. Gustave Le Bon admet bien sûr que les peuples ne vivent pas en autarcie et s’inspirent mutuellement, notamment dans le domaine artistique. Pourtant, il soutient que ces inspirations ne sont qu’accessoires. Les éléments importés ne sont qu’une matière brute que les aspirations profondes du peuple importateur ne manquent jamais de remodeler.

Ainsi, l’art de l’Egypte ancienne a irrigué la création artistique d’autres peuples pendant des siècles. Mais cet art, essentiellement religieux et funéraire et dont l’aspect massif et imperturbable rappelait la fascination des égyptiens pour la mort et la quête de vie éternelle, reflétait trop l’âme égyptienne pour être repris sans altérations par d’autres. D’abord communiqué aux peuples du Proche-Orient, cet art égyptien a inspiré les cités grecques. Mais Gustave Le Bon estime que ces influences égyptiennes ont irrigué ces peuples à travers le prisme de leur propre esprit. Tant qu’il ne s’est pas détaché des modèles orientaux, l’art grec s’est maintenu pendant plusieurs siècles à un stade de pâle imitation. Ce n’est qu’en se métamorphosant soudainement et en rompant avec l’art oriental que l’art grec connut son apogée à travers un art authentiquement grec, celui du Parthénon. A partir, d’un matériau identique qu’est le modèle égyptien transmis par les Perses, la civilisation indienne a abouti à un résultat radicalement différent de l’art grec. Parvenu à un stade de raffinement élevé dès les siècles précédant notre ère mais n’ayant que très peu évolué ensuite, l’art indien témoigne de la stabilité organique du peuple indien : « jusqu’à l’époque où elle fut soumis à la loi de l’islam, l’Inde a toujours absorbé les différents conquérants qui l’avaient envahie sans se laisser influencer par eux ».

Ainsi, l’art de l’Egypte ancienne a irrigué la création artistique d’autres peuples pendant des siècles. Mais cet art, essentiellement religieux et funéraire et dont l’aspect massif et imperturbable rappelait la fascination des égyptiens pour la mort et la quête de vie éternelle, reflétait trop l’âme égyptienne pour être repris sans altérations par d’autres. D’abord communiqué aux peuples du Proche-Orient, cet art égyptien a inspiré les cités grecques. Mais Gustave Le Bon estime que ces influences égyptiennes ont irrigué ces peuples à travers le prisme de leur propre esprit. Tant qu’il ne s’est pas détaché des modèles orientaux, l’art grec s’est maintenu pendant plusieurs siècles à un stade de pâle imitation. Ce n’est qu’en se métamorphosant soudainement et en rompant avec l’art oriental que l’art grec connut son apogée à travers un art authentiquement grec, celui du Parthénon. A partir, d’un matériau identique qu’est le modèle égyptien transmis par les Perses, la civilisation indienne a abouti à un résultat radicalement différent de l’art grec. Parvenu à un stade de raffinement élevé dès les siècles précédant notre ère mais n’ayant que très peu évolué ensuite, l’art indien témoigne de la stabilité organique du peuple indien : « jusqu’à l’époque où elle fut soumis à la loi de l’islam, l’Inde a toujours absorbé les différents conquérants qui l’avaient envahie sans se laisser influencer par eux ».

Néanmoins, Gustave Le Bon admet que les idées puissent pénétrer un peuple en son âme. Il reconnaît aux idées religieuses une force particulière, capable de laisser une empreinte durable dans la psychologie collective même si elles ne sont le plus souvent qu’éphémères et laissent ressurgir le vieux fonds populaire. Seul un nombre infime d’idées nouvelles a vocation à modifier l’âme d’un peuple et ces idées nécessitent pour cela beaucoup de temps. Elles sont d’abord défendues par un petit nombre d’individus ayant développé une foi intense en elles. Estimant que « les foules se laissent persuader par des suggestions, jamais par les démonstrations », Gustave Le Bon explique que ces idées se propagent par le prestige de leur représentants ou par les passions collectives que ceux-ci savent attiser. Après avoir dépassé le stade intellectuel, trop fragile, pour se muer en sentiments, certaines idées accèdent au statut de dogmes. Elles sont alors solidement ancrées dans les mentalités collectives et ne peuvent plus être discutées. Gustave Le Bon estime que les civilisations ont besoin de cette fixité pour se construire. Ce n’est que lors des phases de décadence que les certitudes d’un peuple pourront être remises en question.

La genèse des peuples

La genèse des peuples

Gustave Le Bon n’élude pas la question de la naissance des peuples et de l’âme qu’ils incarnent. Loin de tout dogmatisme, l’anthropologue français souligne que c’est la dynamique de l’histoire qui accouche des peuples. Seuls des peuples marginaux vivant retirés du monde pourraient prétendre ne pas être le fruit de l’histoire et des brassages de populations. Les peuples historiques, tels qu’ils existent aujourd’hui, se sont édifiés avec le temps par de lentes accumulations héréditaires et culturelles qui ont homogénéisé leurs mentalités. Les périodes historiques produisant des fusions de populations constituent le meilleur moyen de faire naître un nouveau peuple. Cependant, leur effet immédiat sera de briser les peuples fusionnés provoquant ainsi la décadence de leurs civilisations. Le Bon illustre ses propos par l’exemple de la chute de l’empire romain. Pour lui, celle-ci eut pour cause première la disparition du peuple romain originel. Conçues par et pour ce peuple fondateur, les institutions romaines ne pouvaient pas lui survivre. La dilution des romains dans les populations conquises aurait fait disparaître l’âme romaine. Les efforts déployés par les conquérants pour maintenir les institutions romaines, objet de leur admiration, ne pouvaient donc qu’être vains.

Ainsi, de la poussière des peuples disparus, de nouveaux peuples sont appelés à naître. Tous les peuples européens sont nés de cette façon. Ces périodes de trouble et de mélange sont également des périodes d’accroissement du champ des possibles. L’affaiblissement de l’âme collective renforce le rôle des individus et favorise la libre discussion des idées et des religions. Les événements historiques et l’environnement peuvent alors contribuer à forger de nouvelles mentalités. Cependant, privées de tout élan collectif et freinées par l’hétérogénéité des caractères, de telles sociétés décadentes ne peuvent édifier que des balbutiements de civilisation. En décrivant ainsi la genèse et la mort des peuples, Gustave Le Bon révèle que sa théorie des civilisations repose sur l’alternance du mouvement et de la fixité. A la destruction créatrice provoquée par des mélanges de populations succèdent des périodes de sédimentation qui laissent une place conséquente à l’histoire et parfois aux individus. Ce n’est qu’après l’achèvement de cette sédimentation que la fixation des mentalités collectives permettra d’édifier une nouvelle âme, socle d’une nouvelle civilisation. Tant que cette âme n’aura pas été détruite, le destin de son peuple dépendra étroitement d’elle.

Le psychologue français défend également le rôle du « caractère » dans le destin d’un peuple. Contrairement à l’âme qui est fixe, le caractère d’un peuple évolue selon les époques. Le caractère se définit par la capacité d’un peuple à croire en ses dogmes et à s’y conformer avec persévérance et énergie. Tandis que l’âme incarne le déterminisme collectif des peuples et alors que l’intelligence est une donnée individuelle inégalement répartie au sein d’un même peuple, le caractère est le fruit d’une volonté collective également répartie au sein d’un peuple. La teneur du caractère détermine la destinée des peuples par rapport à leur rivaux : « c’est par le caractère que 60.000 Anglais tiennent sous le joug 250 millions d’Hindous, dont beaucoup sont au moins leurs égaux par l’intelligence, et dont quelques uns les dépassent immensément par les goûts artistiques et la profondeur des vues philosophiques ». Admiratif du caractère des peuples anglais et américain de son époque, Gustave Le Bon affirme qu’ils sont parmi les seuls à égaler celui du peuple romain primitif.

Archétype de l’intellectuel généraliste du XIXe siècle, Gustave Le Bon a développé une réflexion originale de la notion de peuple. Irriguée par une solide culture historique, sa pensée se distingue tant de l’idéalisme abstrait des Lumières que d’un matérialisme darwinien. L’âme et le caractère sont chez lui des notions qui mêlent hérédité et histoire en laissant également sa place à la volonté collective.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

In his Parmenides, Martin Heidegger contributed an interesting remark in regards to the Greek term “polis”, which once again confirms the importance and necessity of serious etymological analysis. By virtue of its profundity, we shall reproduce this quote in full:

In his Parmenides, Martin Heidegger contributed an interesting remark in regards to the Greek term “polis”, which once again confirms the importance and necessity of serious etymological analysis. By virtue of its profundity, we shall reproduce this quote in full:

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

While Rome had also been founded as “a biopolitical regime” and had some policies to promote fertility and eugenics (120), this was far less central to Roman than to Greek thought, and gradually declined with the Empire. Political ideology seems to have followed political realities. The Stoics and Cicero posited a “natural law” not deriving from a particular organism, but as a kind of cosmic, disembodied moral imperative, and tended to emphasize the basic commonality of human beings (e.g. Cicero, Laws, 1.30).

While Rome had also been founded as “a biopolitical regime” and had some policies to promote fertility and eugenics (120), this was far less central to Roman than to Greek thought, and gradually declined with the Empire. Political ideology seems to have followed political realities. The Stoics and Cicero posited a “natural law” not deriving from a particular organism, but as a kind of cosmic, disembodied moral imperative, and tended to emphasize the basic commonality of human beings (e.g. Cicero, Laws, 1.30).

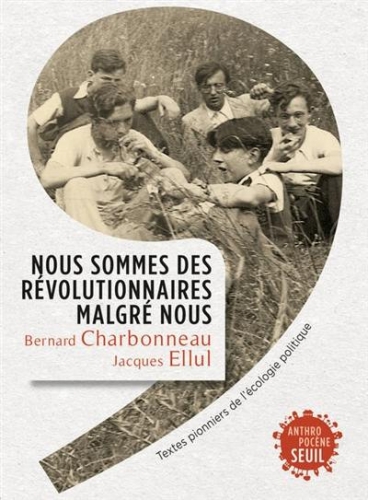

L'homme est au centre de l'univers selon Charbonneau, qui ouvre son texte de bien belle façon en affirmant qu'avant «l'acte divin, avant la pensée, il n'y a ni temps, ni espace : comme ils disparaîtront quand l'homme aura disparu dans le néant, ou en Dieu» (1). Si l'homme se trouve au centre d'une dramaturgie unissant l'espace et le temps, c'est qu'il a donc le pouvoir non seulement d'organiser ces derniers mais aussi, bien évidemment, de les déstructurer, comme l'illustre l'accélération du temps et le rapetissement de l'espace dont est victime notre époque car, «si nous savons faire silence en nous, nous pouvons sentir le sol qui nous a jusqu'ici portés vibrer sous le galop accéléré d'un temps qui se précipite», et comprendre que nous nous condamnons à vivre entassés dans un «univers concentrationnaire surpeuplé et surorganisé» (le terme concentrationnaire est de nouveau employé à la page 31, puis à la page 50), où l'espace à l'évidence mais aussi le temps nous manqueront, alors que nous nous disperserons «dans un vide illimité, dépourvu de bornes matérielles, autant que spirituelles».

L'homme est au centre de l'univers selon Charbonneau, qui ouvre son texte de bien belle façon en affirmant qu'avant «l'acte divin, avant la pensée, il n'y a ni temps, ni espace : comme ils disparaîtront quand l'homme aura disparu dans le néant, ou en Dieu» (1). Si l'homme se trouve au centre d'une dramaturgie unissant l'espace et le temps, c'est qu'il a donc le pouvoir non seulement d'organiser ces derniers mais aussi, bien évidemment, de les déstructurer, comme l'illustre l'accélération du temps et le rapetissement de l'espace dont est victime notre époque car, «si nous savons faire silence en nous, nous pouvons sentir le sol qui nous a jusqu'ici portés vibrer sous le galop accéléré d'un temps qui se précipite», et comprendre que nous nous condamnons à vivre entassés dans un «univers concentrationnaire surpeuplé et surorganisé» (le terme concentrationnaire est de nouveau employé à la page 31, puis à la page 50), où l'espace à l'évidence mais aussi le temps nous manqueront, alors que nous nous disperserons «dans un vide illimité, dépourvu de bornes matérielles, autant que spirituelles».  Hélas, l'homme moderne ne semble avoir de goût, comme le pensait Max Picard, que pour la fuite et, fuyant sans cesse, il semble précipiter la création entière dans sa propre vitesse s'accroissant davantage, la fuite appelant la fuite, bien qu'il ne faille pas confondre cette accélération avec le «rythme d'une existence humaine [qui] est celui d'une tragédie dont le dénouement se précipite». Ainsi, la «nuit d'amour dont l'aube semblait ne jamais devoir se lever n'est plus qu'un bref instant de rêve entre le jour et le jour; du printemps au printemps, les saisons sont plus courtes que ne l'étaient les heures. Vient même un âge qui réalise la disparition du présent, qui ne peut plus dire : je vis, mais : j'ai vécu; où rien n'est sûr, sinon que tout est déjà fini» (p. 22).

Hélas, l'homme moderne ne semble avoir de goût, comme le pensait Max Picard, que pour la fuite et, fuyant sans cesse, il semble précipiter la création entière dans sa propre vitesse s'accroissant davantage, la fuite appelant la fuite, bien qu'il ne faille pas confondre cette accélération avec le «rythme d'une existence humaine [qui] est celui d'une tragédie dont le dénouement se précipite». Ainsi, la «nuit d'amour dont l'aube semblait ne jamais devoir se lever n'est plus qu'un bref instant de rêve entre le jour et le jour; du printemps au printemps, les saisons sont plus courtes que ne l'étaient les heures. Vient même un âge qui réalise la disparition du présent, qui ne peut plus dire : je vis, mais : j'ai vécu; où rien n'est sûr, sinon que tout est déjà fini» (p. 22).

Porque a fines del siglo XX España podía presumir de poseer su propia tradición filosófica. Y no lo queríamos ver. Desde sus aulas de Oviedo yo tuve el privilegio de aprender de don Gustavo Bueno que la lengua castellana era tan buena como la que más, buena para el cultivo de la filosofía. De mi maestro aprendí que había que rebajar ínfulas al predominio editorial y académico del inglés, del francés o del alemán.

Porque a fines del siglo XX España podía presumir de poseer su propia tradición filosófica. Y no lo queríamos ver. Desde sus aulas de Oviedo yo tuve el privilegio de aprender de don Gustavo Bueno que la lengua castellana era tan buena como la que más, buena para el cultivo de la filosofía. De mi maestro aprendí que había que rebajar ínfulas al predominio editorial y académico del inglés, del francés o del alemán.  En el caso de Trías, y su "filosofía del límite" también contamos con una expresión del quehacer filosófico español de gran calidad, de enorme altura, aunque muy distinta de la obra buenista en formato, lenguaje y preocupaciones si la comparamos con la obra de Bueno. Triunfa el Arte y la Metáfora como recursos y temas en el pensador barcelonés, mientras que la Lógica y la Ciencia son ineludibles en el ovetense. Pero, como no hay espacio ni ocasión para analizar a estos dos gigantes, no quiero cerrar mi reflexión, sin conducir la mirada del lector hacia el tercer sistema filosófico que ahora, muy acallado por los medios, viene lanzando a la palestra hispana el profesor Fernández Lorenzo.

En el caso de Trías, y su "filosofía del límite" también contamos con una expresión del quehacer filosófico español de gran calidad, de enorme altura, aunque muy distinta de la obra buenista en formato, lenguaje y preocupaciones si la comparamos con la obra de Bueno. Triunfa el Arte y la Metáfora como recursos y temas en el pensador barcelonés, mientras que la Lógica y la Ciencia son ineludibles en el ovetense. Pero, como no hay espacio ni ocasión para analizar a estos dos gigantes, no quiero cerrar mi reflexión, sin conducir la mirada del lector hacia el tercer sistema filosófico que ahora, muy acallado por los medios, viene lanzando a la palestra hispana el profesor Fernández Lorenzo.

Acheter

Acheter  Évidemment, tout, absolument tout étant lié, surtout lorsqu'il s'agit des affinités électives existant entre les grands esprits qui appréhendent le monde en établissant des arches, parfois fragiles mais stupéfiantes de hardiesse, entre des réalités qu'en apparence rien ne relie (cf. p. 38), je ne pouvais, poursuivant la lecture de cet excellent petit livre qui m'a fait découvrir le fulgurant (et, apparemment, horripilant) Jacob Taubes, que finalement tomber sur le nom qui, selon ce dernier, reliait Maritain à Schmitt, qualifié de «profond penseur catholique» : Léon Bloy, autrement dit le porteur, le garnt ou, pourquoi pas, le «signe secret» (p. 96) lui-même. Après Kafka saluant le génie de l'imprécation bloyenne, c'est au tour du surprenant Taubes, au détour de quelques mots laissés sans la moindre explication, comme l'une de ces saillies propres aux interventions orales, qui stupéfièrent ou scandalisèrent et pourquoi pas stupéfièrent et scandalisèrent) celles et ceux qui, dans le public, écoutèrent ces maîtres de la parole que furent Taubes et Kojève (cf. p. 47). Il n'aura évidemment échappé à personne que l'un et l'autre, Kafka et le grand commentateur de la Lettre aux Romains de l'apôtre Paul, sont juifs, Jacob Taubes se déclarant même «Erzjude» «archijuif», traduction préférable à celle de «juif au plus profond» (p. 67) que donne notre petit livre : «l'ombre de l'antisémitisme actif se profilait sur notre relation, fragile comme toujours» (p. 47), écrit ainsi l'auteur en évoquant la figure de Carl Schmitt qui, comme Martin Heidegger mais aussi Adolf Hitler, est un «catholique éventé» dont le «génie du ressentiment» lui a permis de lire «les sources à neuf» (p. 112).

Évidemment, tout, absolument tout étant lié, surtout lorsqu'il s'agit des affinités électives existant entre les grands esprits qui appréhendent le monde en établissant des arches, parfois fragiles mais stupéfiantes de hardiesse, entre des réalités qu'en apparence rien ne relie (cf. p. 38), je ne pouvais, poursuivant la lecture de cet excellent petit livre qui m'a fait découvrir le fulgurant (et, apparemment, horripilant) Jacob Taubes, que finalement tomber sur le nom qui, selon ce dernier, reliait Maritain à Schmitt, qualifié de «profond penseur catholique» : Léon Bloy, autrement dit le porteur, le garnt ou, pourquoi pas, le «signe secret» (p. 96) lui-même. Après Kafka saluant le génie de l'imprécation bloyenne, c'est au tour du surprenant Taubes, au détour de quelques mots laissés sans la moindre explication, comme l'une de ces saillies propres aux interventions orales, qui stupéfièrent ou scandalisèrent et pourquoi pas stupéfièrent et scandalisèrent) celles et ceux qui, dans le public, écoutèrent ces maîtres de la parole que furent Taubes et Kojève (cf. p. 47). Il n'aura évidemment échappé à personne que l'un et l'autre, Kafka et le grand commentateur de la Lettre aux Romains de l'apôtre Paul, sont juifs, Jacob Taubes se déclarant même «Erzjude» «archijuif», traduction préférable à celle de «juif au plus profond» (p. 67) que donne notre petit livre : «l'ombre de l'antisémitisme actif se profilait sur notre relation, fragile comme toujours» (p. 47), écrit ainsi l'auteur en évoquant la figure de Carl Schmitt qui, comme Martin Heidegger mais aussi Adolf Hitler, est un «catholique éventé» dont le «génie du ressentiment» lui a permis de lire «les sources à neuf» (p. 112). C'est l'importance, capitale, de cette thématique que Jacob Taubes évoque lorsqu'il affirme que les écailles lui sont tombées des yeux quand il a lu «la courbe tracée par Löwith de Hegel à Nietzsche en passant par Marx et Kierkegaard» (p. 27), auteurs (Hegel, Marx et Kierkegaard) qu'il ne manquera pas d'évoquer dans son Eschatologie occidentale (Nietzsche l'étant dans sa Théologie politique de Paul) en expliquant leur philosophie par l'apocalyptique souterraine qui n'a à vrai dire jamais cessé d'irriguer le monde (4) dans ses multiples transformations, et paraît même s'être orientée, avec le régime nazi, vers une furie de destruction du peuple juif, soit ce peuple élu jalousé par le catholiques (et même les chrétiens) conséquents. Lisons l'explication de Taubes, qui pourra paraître une réduction aux yeux de ses adversaires ou une fulgurance dans l'esprit de ses admirateurs : «Carl Schmitt était membre du Reich allemand avec ses prétentions au Salut», tandis que lui, Taubes, était «fils du peuple véritablement élu par Dieu, suscitant donc l'envie des nations apocalyptiques, une envie qui donne naissance à des fantasmagories et conteste le droit de vivre au peuple réellement élu» (pp. 48-9, le passage plus haut cité suit immédiatement ces lignes).

C'est l'importance, capitale, de cette thématique que Jacob Taubes évoque lorsqu'il affirme que les écailles lui sont tombées des yeux quand il a lu «la courbe tracée par Löwith de Hegel à Nietzsche en passant par Marx et Kierkegaard» (p. 27), auteurs (Hegel, Marx et Kierkegaard) qu'il ne manquera pas d'évoquer dans son Eschatologie occidentale (Nietzsche l'étant dans sa Théologie politique de Paul) en expliquant leur philosophie par l'apocalyptique souterraine qui n'a à vrai dire jamais cessé d'irriguer le monde (4) dans ses multiples transformations, et paraît même s'être orientée, avec le régime nazi, vers une furie de destruction du peuple juif, soit ce peuple élu jalousé par le catholiques (et même les chrétiens) conséquents. Lisons l'explication de Taubes, qui pourra paraître une réduction aux yeux de ses adversaires ou une fulgurance dans l'esprit de ses admirateurs : «Carl Schmitt était membre du Reich allemand avec ses prétentions au Salut», tandis que lui, Taubes, était «fils du peuple véritablement élu par Dieu, suscitant donc l'envie des nations apocalyptiques, une envie qui donne naissance à des fantasmagories et conteste le droit de vivre au peuple réellement élu» (pp. 48-9, le passage plus haut cité suit immédiatement ces lignes).  Cette complexité se retrouve dans le jugement de Jacob Taubes sur Carl Schmitt qui, ce point au moins est évident, avait une réelle importance intellectuelle à ses yeux, était peut-être même l'un des seuls contemporains pour lequel il témoigna de l'estime, au-delà même du fossé qui les séparait : «On vous fait réciter un alphabet démocratique, et tout privat-docent en politologie est évidemment obligé, dans sa leçon inaugurale, de flanquer un coup de pied au cul à Carl Schmitt en disant que la catégorie ami / ennemi n'est pas la bonne. Toute une science s'est édifiée là pour étouffer le problème» (p. 115), problème qui seul compte, et qui, toujours selon Jacob Taubes, a été correctement posé par le seul Carl Schmitt, problème qui n'est autre que l'existence d'une «guerre civile en cours à l'échelle mondiale» (p. 109). Dans sa belle préface, Elettra Stimilli a du reste parfaitement raison de rapprocher, de façon intime, les pensées de Schmitt et de Taubes, écrivant : «Révolution et contre-révolution ont toujours évolué sur le plan linéaire du temps, l'une du point de vue du progrès, l'autre de celui de la tradition. Toutes deux sont liées par l'idée d'un commencement qui, depuis l'époque romaine, est essentiellement une «fondation». Si du côté de la tradition cela ne peut qu'être évident, étant donné que déjà le noyau central de la politique romaine est la foi dans la sacralité de la fondation, entendue comme ce qui maintient un lien entre toutes les générations futures et doit pour cette raison être transmise, par ailleurs, nous ne parviendrons pas à comprendre les révolutions de l'Occident moderne dans leur grandeur et leur tragédie si, comme le dit Hannah Arendt, nous ne le concevons pas comme «autant d'efforts titanesques accomplis pour reconstruire les bases, renouer le fil interrompu de la tradition et restaurer, avec la fondation de nouveaux systèmes politiques, ce qui pendant tant de siècles a conféré dignité et grandeur aux affaires humaines» (pp. 15-6).

Cette complexité se retrouve dans le jugement de Jacob Taubes sur Carl Schmitt qui, ce point au moins est évident, avait une réelle importance intellectuelle à ses yeux, était peut-être même l'un des seuls contemporains pour lequel il témoigna de l'estime, au-delà même du fossé qui les séparait : «On vous fait réciter un alphabet démocratique, et tout privat-docent en politologie est évidemment obligé, dans sa leçon inaugurale, de flanquer un coup de pied au cul à Carl Schmitt en disant que la catégorie ami / ennemi n'est pas la bonne. Toute une science s'est édifiée là pour étouffer le problème» (p. 115), problème qui seul compte, et qui, toujours selon Jacob Taubes, a été correctement posé par le seul Carl Schmitt, problème qui n'est autre que l'existence d'une «guerre civile en cours à l'échelle mondiale» (p. 109). Dans sa belle préface, Elettra Stimilli a du reste parfaitement raison de rapprocher, de façon intime, les pensées de Schmitt et de Taubes, écrivant : «Révolution et contre-révolution ont toujours évolué sur le plan linéaire du temps, l'une du point de vue du progrès, l'autre de celui de la tradition. Toutes deux sont liées par l'idée d'un commencement qui, depuis l'époque romaine, est essentiellement une «fondation». Si du côté de la tradition cela ne peut qu'être évident, étant donné que déjà le noyau central de la politique romaine est la foi dans la sacralité de la fondation, entendue comme ce qui maintient un lien entre toutes les générations futures et doit pour cette raison être transmise, par ailleurs, nous ne parviendrons pas à comprendre les révolutions de l'Occident moderne dans leur grandeur et leur tragédie si, comme le dit Hannah Arendt, nous ne le concevons pas comme «autant d'efforts titanesques accomplis pour reconstruire les bases, renouer le fil interrompu de la tradition et restaurer, avec la fondation de nouveaux systèmes politiques, ce qui pendant tant de siècles a conféré dignité et grandeur aux affaires humaines» (pp. 15-6).

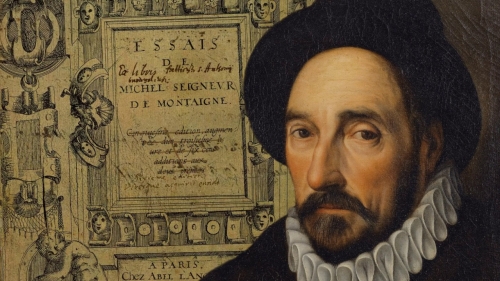

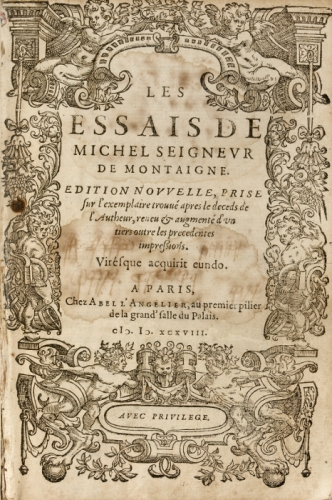

« Tout le monde redoute d’être contrôlé et épié ; les grands le sont jusque dans leurs comportements et leurs pensées, le peuple estimant avoir le droit d’en juger et intérêt à le faire. »

« Tout le monde redoute d’être contrôlé et épié ; les grands le sont jusque dans leurs comportements et leurs pensées, le peuple estimant avoir le droit d’en juger et intérêt à le faire. »

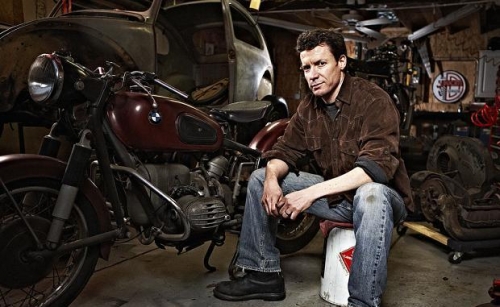

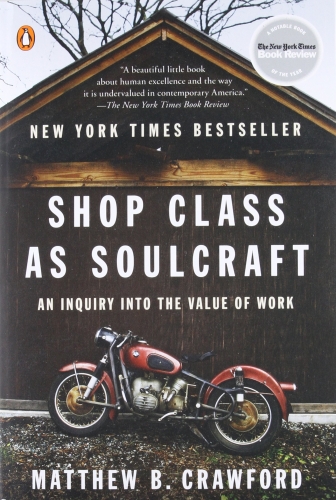

Matthew Crawford is a new but powerful intellectual. His debut in the public sphere began in 2009 with his book Shop Class as Soulcraft, which was affectionately dubbed “Heidegger and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” by

Matthew Crawford is a new but powerful intellectual. His debut in the public sphere began in 2009 with his book Shop Class as Soulcraft, which was affectionately dubbed “Heidegger and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” by  Such a design philosophy does not make people more free. By placing their “free will” beyond the reach of their material environment, we make room for all sorts of impositions on people’s ability to act in their own interests, and we may even make them vulnerable to exploitation. In the casino, this can include exploitation “to extinction.”

Such a design philosophy does not make people more free. By placing their “free will” beyond the reach of their material environment, we make room for all sorts of impositions on people’s ability to act in their own interests, and we may even make them vulnerable to exploitation. In the casino, this can include exploitation “to extinction.”

N.A. -

N.A. -

- 4 - Là était la beauté de l'ancien ordre aristocratique : chacun était pleinement respecté dans son caractère spécifique, à son rang reconnu, et chacun se comportait sincèrement selon ce rang, de sorte qu'il ne pouvait y avoir de conflits nés de la jalousie ou de l'envie.

- 4 - Là était la beauté de l'ancien ordre aristocratique : chacun était pleinement respecté dans son caractère spécifique, à son rang reconnu, et chacun se comportait sincèrement selon ce rang, de sorte qu'il ne pouvait y avoir de conflits nés de la jalousie ou de l'envie. - 11 - Pour moi, dès ma prime jeunesse, je n'étais jamais tombé amoureux ; en tout cas je ne m'étais jamais avoué qu'un amour germait en moi, car mon inconscient très puritain n'admettait pas la simple possibilité d'une chute dans la sensualité, condamnée comme une faiblesse. En outre la conscience des hommes baltes de ma génération qui furent plus ou moins mes contemporains, était encore entièrement déterminée par la tension : sanctuaire inviolable - vice […] ce qui les conduisait d'une part à idéaliser démesurément la femme dite "comme il faut", d'autre part à traîner dans la boue, avec autant d'exagération, toute femme qui menait une vie contraire à l'idéal, ce qui excluait une vie amoureuse libre sous la forme de la beauté.

- 11 - Pour moi, dès ma prime jeunesse, je n'étais jamais tombé amoureux ; en tout cas je ne m'étais jamais avoué qu'un amour germait en moi, car mon inconscient très puritain n'admettait pas la simple possibilité d'une chute dans la sensualité, condamnée comme une faiblesse. En outre la conscience des hommes baltes de ma génération qui furent plus ou moins mes contemporains, était encore entièrement déterminée par la tension : sanctuaire inviolable - vice […] ce qui les conduisait d'une part à idéaliser démesurément la femme dite "comme il faut", d'autre part à traîner dans la boue, avec autant d'exagération, toute femme qui menait une vie contraire à l'idéal, ce qui excluait une vie amoureuse libre sous la forme de la beauté.

Dans une enquête de grande ampleur, qui évoque notamment le radicalisme chrétien d’Orestes Brownson (1803-1876), le transcendantalisme de Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), le mouvement de résistance non violente de Martin Luther King (1929-1968), en passant par le socialisme de guilde de George Douglas Howard Cole (1889-1959), Lasch met en évidence tout un gisement de valeurs relatives à l’humanisme civique, dont les Etats-Unis et plus largement le monde anglo-saxon ont été porteurs en résistance à l’idéologie libérale du progrès. Il retrouve, par-delà les divergences entre ces œuvres, certains constances : l’habitude de la responsabilité associée à la possession de la propriété ; l’oubli volontaire de soi dans un travail astreignant ; l’idéal de la vie bonne, enracinée dans une communauté d’appartenance, face à la promesse de l’abondance matérielle ; l’idée que le bonheur réside avant tout dans la reconnaissance que les hommes ne sont pas faits pour le bonheur. Le regard historique de Lasch, en revenant vers cette tradition, n’incite pas à la nostalgie passéiste pour un temps révolu. A la nostalgie, Lasch va ainsi opposer la mémoire. La nostalgie n’est que l’autre face de l’idéologie progressiste, vers laquelle on se tourne lorsque cette dernière n’assure plus ses promesses. La mémoire quant à elle vivifie le lien entre le passé et le présent en préparant à faire face avec courage à ce qui arrive. Au terme du parcours qu’il raconte dans Le Seul et Vrai Paradis, le lecteur garde donc en mémoire le fait historique suivant : il a existé un courant radical très fortement opposé à l’aliénation capitaliste, au délabrement des conditions de travail, ainsi qu’à l’idée selon laquelle la productivité doit augmenter à la mesure des désirs potentiellement illimités de la nature humaine, mais pourtant tout aussi méfiant à l’égard de la conception marxiste du progrès historique. Volontiers raillée par la doxa marxiste pour sa défense « petite bourgeoise » de la petite propriété, tenue pour un bastion de l’indépendance et du contrôle sur le travail et les conditions de vie, la pensée populiste visait surtout l’idole commune des libéraux et des marxistes, révélant par là même l’obsolescence du clivage droite/gauche : le progrès technique et économique, ainsi que l’optimisme historique qu’il recommande. Selon Lasch qui, dans le débat entre Marx et Proudhon, opte pour les analyses du second, l’éthique populiste des petits producteurs était « anticapitaliste, mais ni socialiste, ni social-démocrate, à la fois radicale, révolutionnaire même, et profondément conservatrice ».

Dans une enquête de grande ampleur, qui évoque notamment le radicalisme chrétien d’Orestes Brownson (1803-1876), le transcendantalisme de Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), le mouvement de résistance non violente de Martin Luther King (1929-1968), en passant par le socialisme de guilde de George Douglas Howard Cole (1889-1959), Lasch met en évidence tout un gisement de valeurs relatives à l’humanisme civique, dont les Etats-Unis et plus largement le monde anglo-saxon ont été porteurs en résistance à l’idéologie libérale du progrès. Il retrouve, par-delà les divergences entre ces œuvres, certains constances : l’habitude de la responsabilité associée à la possession de la propriété ; l’oubli volontaire de soi dans un travail astreignant ; l’idéal de la vie bonne, enracinée dans une communauté d’appartenance, face à la promesse de l’abondance matérielle ; l’idée que le bonheur réside avant tout dans la reconnaissance que les hommes ne sont pas faits pour le bonheur. Le regard historique de Lasch, en revenant vers cette tradition, n’incite pas à la nostalgie passéiste pour un temps révolu. A la nostalgie, Lasch va ainsi opposer la mémoire. La nostalgie n’est que l’autre face de l’idéologie progressiste, vers laquelle on se tourne lorsque cette dernière n’assure plus ses promesses. La mémoire quant à elle vivifie le lien entre le passé et le présent en préparant à faire face avec courage à ce qui arrive. Au terme du parcours qu’il raconte dans Le Seul et Vrai Paradis, le lecteur garde donc en mémoire le fait historique suivant : il a existé un courant radical très fortement opposé à l’aliénation capitaliste, au délabrement des conditions de travail, ainsi qu’à l’idée selon laquelle la productivité doit augmenter à la mesure des désirs potentiellement illimités de la nature humaine, mais pourtant tout aussi méfiant à l’égard de la conception marxiste du progrès historique. Volontiers raillée par la doxa marxiste pour sa défense « petite bourgeoise » de la petite propriété, tenue pour un bastion de l’indépendance et du contrôle sur le travail et les conditions de vie, la pensée populiste visait surtout l’idole commune des libéraux et des marxistes, révélant par là même l’obsolescence du clivage droite/gauche : le progrès technique et économique, ainsi que l’optimisme historique qu’il recommande. Selon Lasch qui, dans le débat entre Marx et Proudhon, opte pour les analyses du second, l’éthique populiste des petits producteurs était « anticapitaliste, mais ni socialiste, ni social-démocrate, à la fois radicale, révolutionnaire même, et profondément conservatrice ».

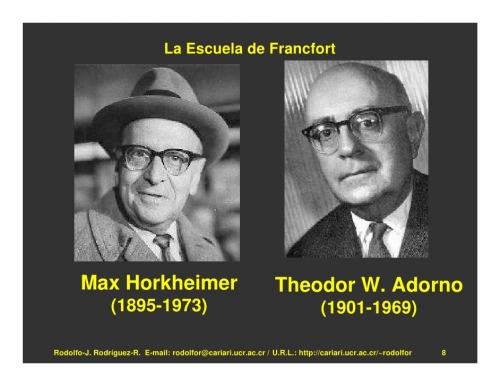

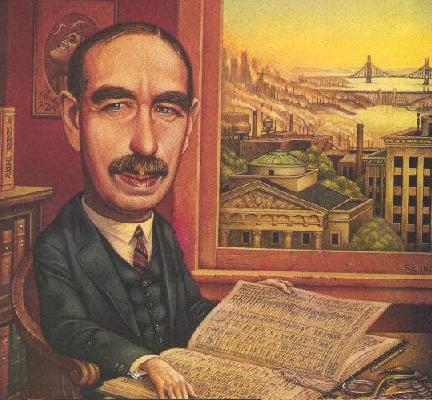

However, the Frankfurt School suggested a different road to the communist paradise than that chosen by Lenin and Stalin in Soviet Russia. The direct intellectual precursors of the Frankfurt School, the Italian Antonio Gramsci (1891 – 1937) and the Hungarian Georg Lukács (1885 – 1971) (photo), had recognized that further west in Europe there was an obstacle on this path which could not be eliminated by physical violence and terror: the private, middle class, classical liberal bourgeois culture based on Christian values. These, they concluded, needed to be destroyed by infiltration of the institutions. Their followers have succeeded in doing so. The sorcerer's apprentices of the Frankfurt School conjured up an army of hobgoblins who empty their buckets over us every day. Instead of water, the buckets are filled with what Lukács had approvingly labelled ‘cultural terrorism.’

However, the Frankfurt School suggested a different road to the communist paradise than that chosen by Lenin and Stalin in Soviet Russia. The direct intellectual precursors of the Frankfurt School, the Italian Antonio Gramsci (1891 – 1937) and the Hungarian Georg Lukács (1885 – 1971) (photo), had recognized that further west in Europe there was an obstacle on this path which could not be eliminated by physical violence and terror: the private, middle class, classical liberal bourgeois culture based on Christian values. These, they concluded, needed to be destroyed by infiltration of the institutions. Their followers have succeeded in doing so. The sorcerer's apprentices of the Frankfurt School conjured up an army of hobgoblins who empty their buckets over us every day. Instead of water, the buckets are filled with what Lukács had approvingly labelled ‘cultural terrorism.’ The sorcerer's apprentices of the Frankfurt School dreamt of a communist paradise on earth. Initially, among the hard left they were the only ones aware of the fact that this brutal path to paradise would fail. With the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, however, this failure was obvious to all. This was the New Left’s moment. It was only then that they got any traction and noticeable response. At least in Western Europe. In the US, this moment of truth may have come a little later. Gary North contends in his book ‘Unholy Spirits’ that John F. Kennedy’s death was “the death rattle of the older rationalism.” A few weeks later, Beatlemania came to America. However, the appearance of the book ‘Silent Spring’ by Rachel Carson in September 1962, which heralded the start of environmentalism, points to the Berlin Wall as the more fundamental game changer in the West. A few years later, the spellbound hobgoblins began their long march through the institutions.

The sorcerer's apprentices of the Frankfurt School dreamt of a communist paradise on earth. Initially, among the hard left they were the only ones aware of the fact that this brutal path to paradise would fail. With the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, however, this failure was obvious to all. This was the New Left’s moment. It was only then that they got any traction and noticeable response. At least in Western Europe. In the US, this moment of truth may have come a little later. Gary North contends in his book ‘Unholy Spirits’ that John F. Kennedy’s death was “the death rattle of the older rationalism.” A few weeks later, Beatlemania came to America. However, the appearance of the book ‘Silent Spring’ by Rachel Carson in September 1962, which heralded the start of environmentalism, points to the Berlin Wall as the more fundamental game changer in the West. A few years later, the spellbound hobgoblins began their long march through the institutions.

Bell’s masterwork,

Bell’s masterwork,  Rage against bourgeois order and embrace of Dionysian expression, said Bell, furthers the “loss of coherence in culture, particularly in the spread of an antinomian attitude to moral norms and even to the idea of cultural judgment itself.” What Bell called a consumption ethic, grafted to a life unregulated by church, family, or school, and a fun morality, were blooming into a new zeitgeist. Bell could not perfectly foresee universal smartphones, multiculturalism, or Beyoncé, for example, but he surely glimpsed the appeal of their antecedents.

Rage against bourgeois order and embrace of Dionysian expression, said Bell, furthers the “loss of coherence in culture, particularly in the spread of an antinomian attitude to moral norms and even to the idea of cultural judgment itself.” What Bell called a consumption ethic, grafted to a life unregulated by church, family, or school, and a fun morality, were blooming into a new zeitgeist. Bell could not perfectly foresee universal smartphones, multiculturalism, or Beyoncé, for example, but he surely glimpsed the appeal of their antecedents. “Despite the shambles of modern culture, some religious answer surely will be forthcoming,” Bell asserted. Religion is a “constitutive part of man’s consciousness.” It grows out of the “primordial need” for “a set of meanings that will establish a transcendent response to self; and the existential need to confront the finalities of suffering and death.” What that religion might be or become going forward cannot yet be known. The grand Western traditions were Antiquity and Church, both of them now compromised and slandered. In the contemporary

“Despite the shambles of modern culture, some religious answer surely will be forthcoming,” Bell asserted. Religion is a “constitutive part of man’s consciousness.” It grows out of the “primordial need” for “a set of meanings that will establish a transcendent response to self; and the existential need to confront the finalities of suffering and death.” What that religion might be or become going forward cannot yet be known. The grand Western traditions were Antiquity and Church, both of them now compromised and slandered. In the contemporary

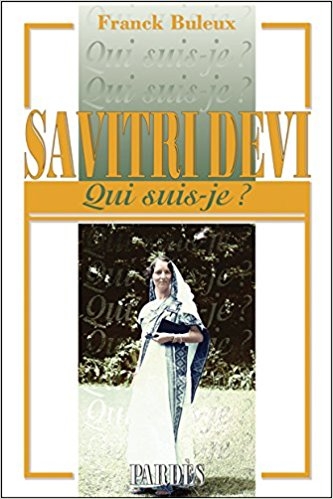

Franck Buleux: Écrire une biographie sur Savitri Devi, c’est surtout avoir la capacité préalable, et nécessaire, d’éloigner de son propre esprit la reductio ad hitlerum dont elle a fait – et fait toujours – l’objet et, il faut bien le dire, dans laquelle elle a baigné de son plein gré. Toutefois, refuser de réduire une personne à un mythe même convenu – et accepté -est l’essence même du respect de la nature humaine, par définition complexe.

Franck Buleux: Écrire une biographie sur Savitri Devi, c’est surtout avoir la capacité préalable, et nécessaire, d’éloigner de son propre esprit la reductio ad hitlerum dont elle a fait – et fait toujours – l’objet et, il faut bien le dire, dans laquelle elle a baigné de son plein gré. Toutefois, refuser de réduire une personne à un mythe même convenu – et accepté -est l’essence même du respect de la nature humaine, par définition complexe.

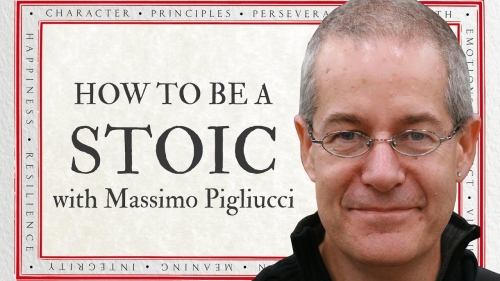

There is a lot of wisdom here. At the very least, it leads one to ask questions: What is the role of a young man with regard to the fitness and well-being of the species? What is the role of a young woman? What is the role of a European in a context of decline? And so on. Stoicism represents one powerful way in which postmodern Westerners, conquered by liberalism, can learn to stop being so frivolous, narcissistic, and selfish, and begin living our lives in a mindful and communitarian fashion.

There is a lot of wisdom here. At the very least, it leads one to ask questions: What is the role of a young man with regard to the fitness and well-being of the species? What is the role of a young woman? What is the role of a European in a context of decline? And so on. Stoicism represents one powerful way in which postmodern Westerners, conquered by liberalism, can learn to stop being so frivolous, narcissistic, and selfish, and begin living our lives in a mindful and communitarian fashion.