Pierre Le Vigan:

Michel Maffesoli : La « faillite des élites » ou bien plutôt « les tribus contre le peuple »?

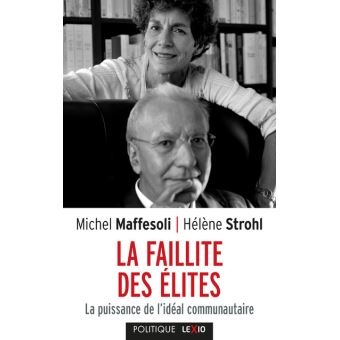

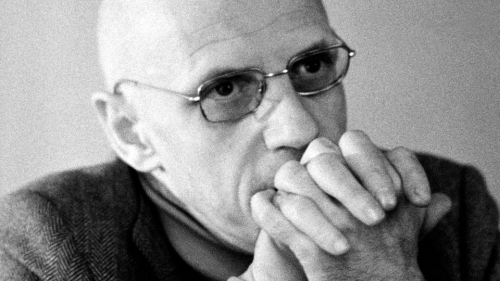

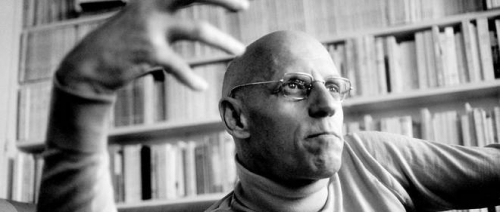

Politologue et sociologue, Michel Maffesoli décrypte depuis des décennies les mouvements profonds de notre société. Ses livres ne laissent pas indifférent. La violence totalitaire, L’ombre de Dionysos, La contemplation du monde, Le temps des tribus (1988), … tous ont marqué une étape et un approfondissement de ses thèmes. Ses constats n’échappent pas à la subjectivité dans laquelle est pris tout sociologue. Les conclusions qu’il en tire sont elles-mêmes tributaires de ses jugements de valeur. Son dernier livre, la faillite des élites, devrait une fois de plus faire l’objet de polémique. Il le mérite. Exploration de ses thèmes, et analyse critique.

Le thème principal de Michel Maffesoli est, depuis des années, le déclin de la modernité. C’est ce thème qu’il reprend avec Hélène Strohl dans La faillite des élites, sous-titré La puissance de l’idéal communautaire (Cerf, 2019). Le thème, c’est l’agonie de la modernité. C’en est fini de la démocratie parlementaire, du républicanisme civique, des syndicats, qui « se contentent de défendre des privilèges on ne peut plus dépassés » – privilèges qui, en passant, me paraissent une goutte d’eau par rapport aux privilèges des hommes du Capital, mais qui retiennent, sans originalité excessive, l’attention de Michel Maffesoli.

Selon le sociologue, ce sont toutes les catégories de la modernité qui s’effondrent : l’égalité, la raison, le progrès, les procédures formelles de validation du vrai. Et on devrait ajouter : la vérité elle-même, et la justice sociale, tout ce qui n’est pas vérifiable à hauteur d’une communauté forcément restreinte, puisque c’est celle d’affinités choisies, les affinités électives. On remarque que les catégories qui disparaissent ne se superposent pas toutes ; certaines sont même antagoniques. Les vertus civiques de la République, ce n’est pas tout à fait la même chose que la démocratie parlementaire, même si, sous la IIIe République, les deux choses se sont accommodées.

La technologie, nous dit Maffesoli, devient une technomagie, favorisant la cristallisation des émotions. A la vie de l’esprit succède « la vie de tout le corps » (Miguel de Unanumo). A une élite déconnectée du peuple succède la mise en cause de l’élite par le peuple – et on arrive ici au sens du titre du livre. Le peuple se rappelle soudain qu’il est l’instituant, et que l’Etat n’est que l’institué. Il est temps, pense le peuple, de remettre les choses à l’endroit. Bien sûr. Mais précisément, ce que furent les Gilets jaunes, c’est une demande de politique, et ce qu’ils mirent en pratique, c’est le dépassement des petites communautés (les artisans, les femmes seules au RSA, les autoentrepreneurs, etc) au profit d’un mouvement fédérateur des différences, et largement d’accord sur un point essentiel, et ce point est politique, qui est le référendum d’initiative populaire, qui est la revendication même d’un pouvoir populaire, c’est-à-dire d’un pouvoir arraché à l’oligarchie.

Résumons le constat de Michel Maffesoli, et d’Hélène Strohl : c’est la primauté de la vie sur le concept. La fin de la modernité, c’est de constater que la vie se débarrasse du concept, Le quod (le réel, la vie, le ‘’comment c’est’’) se débarrasse du quid (le concept, le ‘’ce que c’est’’). La modernité a dénié le sentiment d’appartenance. Elle a abouti à des « phénomènes communautaires paroxystiques et donc immaitrisables ». Il s’agit donc de montrer que « les communautés sont là », et que des élites aveugles ont tort de nier cette réalité ou de s’en inquiéter, ou de combattre ce phénomène. Tel est le thème du livre, et telle est sa thèse.

Qu’en penser ? Tout d’abord, le livre pose plusieurs problèmes de lecture. Ce ne sont pas des problèmes de style : il est souple, léger, et parfois précieux : « La socialité est la caractéristique de l’entièreté de l’être en commun » peut se dire plus simplement « l’être humain est un animal social ». Inutile d’être précieux quand la langue vulgaire permet d’exprimer une idée, un concept. Comme disait Diderot : « hâtons-nous de rendre la philosophie populaire ». Ce n’est pas brader la philosophie que de la rendre la plus accessible possible.

Un problème de lecture réside dans le choix de caractères d’imprimerie gris clairs, trop pâlichons. Mais le problème principal réside – on s’en doute – dans la construction même du livre. Les auteurs passent de jugements de fait à des jugements de valeur. Les jugements de fait sont censés être neutres (telle pomme est rouge). Les jugements de valeur ne le sont pas (telle pomme est meilleure qu’une autre). En outre, nous savons que les jugements de fait peuvent être présentés d’une manière non neutre. Exemple : un verre dit à moitié vide est le même que celui dit à moitié plein, mais la tonalité de l’expression n’est pas la même. Le passage d’un registre à l’autre est donc une difficulté du livre. Ce n’est pas la seule.

Il y a dans le livre plusieurs thèmes de niveaux différents. Il y a (1) une anthropologie. C’est celle qui affirme, à juste titre, que l’homme est un animal social, et même communautaire.

Il y a (2) une éthique, qui est qu’il faut s’accorder avec ce qui est. Cette éthique est ambigüe : il faut faire avec ce qui est, nous dit-on, certes, mais doit-on approuver pour autant tout ce qui est ? C’est aussi une éthique qui se veut une éthique de l’esthétique. On peut se demander si elle n’est pas plutôt une éthique de la jouissance (pourquoi pas ? Mais cela pose la question de la disparition du juste et du bien du domaine de l’éthique. Dany-Robert dufour a écrit des choses très pertinentes sur le lien entre capitalisme et idéologie de la jouissance gratuite).

Il y a (3) une vision du monde contemporain : le paradigme postmoderne (la communauté) aurait succédé au paradigme moderne (l’individu). Mais cette vision est-elle exacte ? Prend-t-elle en compte tout le réel ? Gilles Lipovetsky, qui n’est pas non plus un sociologue mineur, et Hervé Juvin, et bien d’autres observateurs ne souscrivent pas à cette analyse : ils estiment que notre société reste individualiste, sous des formes évidemment renouvelées depuis plusieurs décennies. Enfin (c’est le 4e point), les auteurs avancent une philosophie : « Les idées ne sont que la transcription des perceptions sensibles, des affects ressentis (…) » (p. 71). C’est la reprise des conceptions de David Hume. Nos auteurs auraient pu en dire plus sur cette épistémologie qu’ils font leur. Et qui est très aventurée et difficilement soutenable.

Les auteurs voient le monde contemporain comme un grand tournant et une grande libération : libération des concepts, libération de la raison, libération du cogito individuel. C’est la grande braderie des concepts. C’est aussi l’adieu à Kant. Le phénomène se débarrasse du noumène. La vie se débarrasse des théories sur la vie. Le réel se débarrasse des essences. Le sensualisme succède au rationalisme. Les catégories de la liberté et de l’égalité s’épuisent, au profit de liens choisis, et de valeurs choisies, ce qui pose un problème : nous reste-t-il, en tant que Français, quelque chose en commun ?

Point crucial : le peuple se débarrasse des élites. Ou il essaie. Il s’en débarrasse mentalement. Il les laisse tourner à vide. [Mais nos auteurs ne voient pas que l’on ne débarrasse pas si facilement des élites. Elles continuent de mettre en place leur société postnationale et liquide]. La réalité sociale foisonnante reprend conscience d’elle-même, et veut en finir avec les catégories d’ordre, de raison, de justice, qui descendent de l’Etat et des élites rationnelles vers le peuple. Un peuple assujetti devient enfin rebelle. Les instincts reprennent le pas sur la raison. La nature et la surnature (les mythes, l’imaginaire…) prennent le pas sur le culturel et le social normé (les lois, le respect des normes, la convenance…). Ce qui est archétypal (les résidus de Pareto) prendrait le pas sur ce qui rationnel (les dérivations de Pareto), sur ce qui s’objectivise, s’explique, se justifie, y compris les idéologies se piquant de logique. Les dérivations, qui sont les idéologies modernes, sont en train de mourir. L’anthropologie profonde de l’homme, communautaire, aventureuse, jouisseuse, prend sa revanche sur la raison, triste, mécanique, prévisible, travailleuse (trop travailleuse), sérieuse (trop sérieuse).

Le plaisir de l’être-ensemble prime sur le devoir-être du vivre-ensemble. Les liens choisis priment sur les liens imposés, sur les cohabitations forcées, sur les relations transactionnelles, celles qui reposent sur un contrat juridique. Au contrat social entre individus, succède le holisme. La socialité précède l’individu. Le feeling supplante le rationnel, et le calculé. L’homme retrouve sa dimension animale, trop oubliée. L’être humain se rappelle qu’il est un être-avec-autrui, un être en compagnie. Le contrat social explicite cède la place à un pacte implicite, qui est celui des affects.

Le pacte (postmoderne) est fondé sur le consensus, tandis que le contrat (moderne) est fondé sur le compromis. L’écrit cède la place à l’oral. Le contrat était tendu vers le long terme, le pacte concerne le court terme, le présent. Et il concerne la tribu, ici et maintenant. Le présent remplace le projet tout comme il remplace le progrès. Même la sexualité change : on s’accouple moins, on se lèche davantage.

Il serait toutefois raisonnable de ne pas en faire trop. Que les tribus libertines et clubs échangistes « participent à la cohésion sociale », comme l’affirment nos auteurs (p. 144), c’est tout de même beaucoup leur prêter. Par principe, il est très bien que chacun puisse vivre ce qu’il a envie de vivre entre adultes consentants. Mais de là à en faire une opération de salut public de la cohésion sociale, c’est certainement excessif. On aurait plutôt vu, dans ce rôle de facteur de cohésion sociale les retraités, souvent de milieu populaire, qui donnent gratuitement leur temps à des associations de soutien scolaire de quartiers HLM.

Le bonheur postmoderne continue d’être décliné par les auteurs : le commerce des biens, le commerce des idées et le commerce amoureux se rejoignent et se fondent en un seul ensemble. A son petit Moi, l’homme préfère le bain dans une communauté, le « Moi commun », le « moi transcendant » dont parle Novalis, c’est-à-dire le moi qui nous porte au-delà du moi, la communauté comme immersion entre pairs. « La perfection n’est pas dans un ‘’moi’’ tout puissant, mais dans un ‘’nous’’ ouvert, en constante évolution ». C’est la communauté comme élargissement du soi.

L’individu n’étant plus seul, il n’est plus assujetti à un principe unique, incarné par l’Etat. C’est ce qu’Alain Bihr a appelé « le crépuscule des Etats-nations ». A l’Etat providence, vertical, succède une solidarité horizontale : co-location, co-working, co-voiturage, etc. Tout cela réjouit Maffesoli. Ce sont bel et bien le retour à des partages horizontaux, choisis, parfois fraternels. Parfois. Car il y a des exclus de cet Eden communautaire. Le jardin des délices des uns peut être le jardin des supplices des autres. Et la jouissance des uns peut être cruelle, comme le rappelle Dany-Robert Dufour.

Les très pauvres, et en particulier les démunis en bagage culturel, ne bénéficient pas de tels outils, les co-ceci et autres uberisations plus ou moins marchandes, qui supposent maitrise de l’informatique, d’internet, de l’anglais basique. Ces coopérations horizontales entre pairs excluent, par principe, les non pairs, les isolés, et l’isolé n’est pas le cadre célibataire de centre-ville, c’est le retraité dans un village sans commerces, c’est le banlieusard d’un quartier difficile, c’est l’habitant de la cité Charles Hermitte à Paris, porte de la Chapelle, dans un quartier que tout le monde évite du fait de la présence de camps de migrants et de l’insécurité. La réduction de plus en plus nette des moyens de la politique sociale, et de l’Etat providence, qu’il serait plus juste d’appeler Etat protecteur (qui protège matériellement des accidents de la vie) laisse toute une part de la population, surtout française, sans aides, sans soutien, car, justement, tous n’ont pas accès aux solidarités horizontales, organiques. Les Français sont souvent plus désocialisés que les immigrés, dont la culture traditionnelle inclut une fratrie élargie, des solidarités de village, etc. Nous sommes plus désocialisés car plus modernes. Déclin de l’Etat protecteur : pourquoi ? Bien sûr parce que la priorité de nos sociétés est le profit de grands groupes. Mais pas uniquement. Cette réduction des moyens de la politique sociale, surtout par rapport à l’explosion de la précarité, vient de l’immigration, car c’est elle qui rend inépuisables les besoins sociaux. La poursuite de l’immigration, c’est forcément plus d’insécurité sociale pour les Français, et pour les immigrés les plus intégrés, c’est-à-dire ceux qui travaillent.

En ce sens l’Etat social, l’Etat protecteur a bien des défauts mais son principal défaut serait de ne pas exister, c’est-à-dire de laisser la place à la loi de la jungle de la société de marché. Et ce n’est qu’en recentrant cet Etat protecteur sur la base d’une préférence nationale, dissuasive de l’immigration, qu’il peut être sauvé, ainsi qu’en édictant des contreparties entre droits et devoirs.

Les auteurs de La faillite des élites, croyant faire un constat, disent des vérités, mais des vérités partielles, Ils avancent masqués. Ils ont un projet idéologique. C’est leur droit. Mais ce projet n’est pas affiché. Ils nous disent : à l’unité ontologique succède un pluralisme ontologique. « Tout coule. Rien n’est jamais à la même place. Mais le flot est incessant ». Pour être très concret, un pluralisme des valeurs succède à une unicité des valeurs, celles incarnées par la société et par l’Etat, garant de celle-ci. Une sorte de polythéisme vécu, pratique, reviendrait, sans doute dans le prolongement inconscient du christianisme médiéval et du culte pluriel des saints, tant il est vrai, comme disait Joseph de Maitre, que le christianisme – on comprend qu’il s’agit ici du catholicisme – est un « polythéisme raisonné ».

Pour Maffesoli, l’Etat français est fondamentalement unitaire. Il est « monothéiste ». Mais l’auteur se trompe. L’Etat est devenu communautariste. Il n’est plus une unité. Ne croyant plus en la France, l’Etat n’est plus que le garant d’une « société inclusive », c’est-à-dire une société dans laquelle chacun vient avec sa culture, ses croyances, sa foi mais n’envisage pas d’aller avec empathie vers le pays d’accueil, de marquer son affection (oui, il faut ici employer ce terme) envers la France et envers les Français. Ce pas vers la France, certains étrangers le font quand même encore, par exemple en donnant à leurs enfants un prénom français, mais ce pas est de moins en moins fréquent dans la mesure même où l’Etat, an nom du « respect des différences », ne fait rien pour l’encourager. D’où la panne de l’assimilation, devenue impossible quand la masse des étrangers est supérieure, dans beaucoup de quartiers, à la présence des Français de longue filiation, ceux qui constituaient encore, dans les années 1950, 95 % de la population, la France n’ayant jamais été depuis 1500 ans un pays de grande immigration.

La France devient ainsi une superposition hasardeuse de « tribus », un collage maladroit entre différentes communautés, qui s’ignorent, dans le meilleur des cas, ou s’agressent, dans le pire des cas. Finkielkraut a parlé de « balkanisation » de la France. Comment lui donner tort ? D’où une question : cette France rêvée par Michel Maffesoli, la France des tribus, n’est-ce pas une France déjà là ? Celle dans laquelle nous vivons ? N’est-ce pas la France actuelle ?

Maffesoli voit cette France qu’il dit « heureuse » et qui celle de « petite poussette » de Michel Serres, autre optimiste de principe. Dans cette France « débarrassée » des idéologies, des récits, des systèmes d’explication du monde, voire de transformation des sociétés, on aborde sans « préjugés », et plus encore sans recul, les faits du présent sans les hiérarchiser. On se laisse balloter par les émotions, et terrorisé par la marche du progrès. Car la postmodernité n’échappe pas au culte du progrès. Ceux qui pensent que « c’était mieux avant », au moins dans certains domaines, sont toujours ringardisés. « On n’est plus au Moyen-Age… »

Il y a ceux qui sont « en retard », « arriérés » et ceux qui sont « dans la vague », dans le mouvement. « Il faut avancer » : c’est la phrase qui réconcilie les modernes et les postmodernes. Les modernes voulaient avancer vers une société du travail, ou vers une société plus juste, les postmodernes veulent avancer dans la décontraction, l’esprit « cool ».

« Pas de prise de tête » est leur slogan. On passe du « dogmatisme doctrinal » à un pluralisme des opinions, nous dit Maffesoli. Ici, on s’interroge. Pluralisme ? Depuis plus de 50 ans, la liberté d’opinion n’a cessé d’être réduite par des lois, et tout autant par un journalisme-flic, dénonciateur, inquisiteur, qui somme untel de « s’expliquer », et de faire repentance pour une phrase trop spontanée, qui accuse un tel de n’être « pas clair » parce qu’il tient des propos nuancés sur des sujets où l’outrance est obligatoire, etc. Un trait d’humour à propos de l’obsession des violences sexistes amène Finkielkraut à devoir s’expliquer, lui aussi, à bien préciser que c’était de l’humour, un pas de côté pour parler avec un peu de distance de sujets « chauds ». Liberté d’opinion et d’expression à l’époque actuelle, en France ? C’est une plaisanterie que de croire cela.

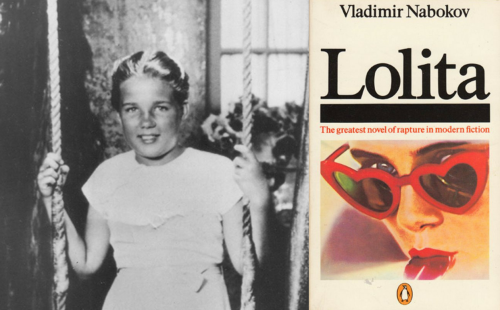

L’homme et l’œuvre sont liés désormais dans une même réprobation. Doit-on interdire le visionnage des films de Polanski parce qu’il aurait abusé d’une jeune fille il y a quelques décennies ? Faut-il rééditer tout Céline ? Telles sont les questions qui sont « débattues ». Absurdité : car il n’est nul besoin de trouver l’homme Céline sympathique, pas plus que l’homme Matzneff, pour trouver leurs œuvres de qualité. Oui, le Taureau de Phalaris est un bon livre. Oui, en même temps, la complaisance vis-à-vis de la pédophilie est déplorable. Oui, lire Céline est nécessaire pour comprendre notre époque, oui, Céline était geignard, parfois odieux, et pas trés digne. Le talent n’excuse rien, c’est entendu, mais il faut toujours distinguer l’homme et l’œuvre.

Nous en sommes là, à l’heure de « l’envie de pénal » de tous contre tous, notre époque n’ayant pas peur du ridicule. On passe de la pensée qui descend des hauteurs universitaires au « gazouillement » des blogs et de twitter. Seulement, twitter, ce n’est tout de même pas du niveau des articles de Chateaubriand, ou de Maurras (qui détestait le premier du reste).

Bien entendu, il n’est pas interdit de relever quelques aspects positifs aux relations telles qu’elles se mettent en place dans le monde postmoderne. La notion d’empathie, ou d’intropathie (connaissance de moi-même en tant que je suis affecté par autrui), supplante celle d’intérêt. Un exemple particulièrement intéressant est celui des groupes de pairs. Ce sont des groupes d’entraide dans lesquels une ou plusieurs personnes étant passés par une problématique (alcool, drogue, autisme, dépression,…) et ayant trouvé des solutions aident les autres à cheminer dans le même sens de diminution d’une souffrance et/ou d’une dépendance pathologique. Ce peut être par exemple, des anciens alcooliques, des usagers de drogues engagés dans des pratiques de réduction des risques (de transmission de virus notamment), des anciens anorexiques, etc. C’est un exemple probant du passage de solidarités mécaniques (comme la redistribution sociale effectuée par l’Etat et les pouvoirs publics) à une solidarité organique (venant des gens eux-mêmes). Qu’il y ait chez l’homme des ressources émotionnelles (un « ordo amoris » dit Max Scheler) qui puissent à la fois l’ouvrir aux autres, et le mettre en correspondance avec un ordre divin, c’est une réalité. Mais elle ne peut suffire à assurer une solidarité entre tous, et à protéger les plus faibles, qui sont les plus désocialisés.

Maffesoli en conclut que le « prétendu individualisme » est un fake (un trucage). C’est un « fake à l’usage d’histrions déphasés ». A l’individualisme aurait succédé une autre époque, celle des identifications multiples. Les identifications multiples, plurielles ne sont pourtant pas une nouveauté. Chacun est célibataire ou en couple, a une fonction professionnelle (on ne dit plus « un métier », ni une profession), a tel engagement, a telle passion, tel passe-temps. Bref, un ingénieur n’est jamais qu’un ingénieur, ce peut être aussi un homme à femmes, ou un homosexuel, un communiste, ou un identitaire, un chasseur, un grand voyageur, un amateur de bons vins, un calme, un nerveux, un sanguin, tout ce que l’on voudra. En même temps. C’est une banalité : chacun a différentes facettes de sa personnalité.

Le constat de Michel Maffesoli, c’est la grande migration des us et coutumes. Il s’en réjoui. Nous avons quitté les eaux de la modernité pour entrer dans celles de la postmodernité. En tout cas d’une certaine postmodernité, solidaire dans l’entre-soi, communautaire entre gens du même monde, décontractée, « tranquille » (chacun connait l’échange « Ca va ? Oui, Tranquille »), apaisée. C’est le temps des bobos [mais on sait qu’il y a une autre postmodernité, qui est celle des Gilets jaunes, qui est celle de la colère spontanée du peuple].

« Non, ce n’est plus l’individualisme qui prévaut » est le titre d’un chapitre du livre. Si c’est le principe qui fait l’histoire, comme le pensait Karl Marx, c’est donc, avec la postmodernité, le principe postmoderne, celui des liens horizontaux, qui fait une histoire postmoderne. C’est du reste l’unique point sur lequel Maffesoli donne raison à Marx.

De fait, la fin de l’efficacité d’un principe marque son déclin. Et une époque est effectivement toujours déterminée par un principe, ou, mieux encore, un paradigme. De même, la fin d’une époque, c’est toujours la fin du principe qui l’a générée. Dans le monde postmoderne, ce qui est donné à la communauté est pris à l’individu. C’est la communauté qui devient la référence, l’individu, lui, est éclaté entre diverses identités. « Ne me demandez pas qui je suis et ne me dites pas de rester le même, c’est une morale d’Etat Civil, elle régit nos papiers », disait Michel Foucault (L’archéologie du savoir). Les identités sont de plus en plus multiples, elles deviennent floues et de plus en plus changeantes. Au-delà des identités, il y a des identifications, et il y a des « sincérités successives ». La conséquence de cela, c’est l’éclatement du moi. On passe du « je pense » cartésien au « je suis pensé » nietzschéen. C’est le motif de la pensée postmoderne connue aux Etats Unis sous le nom de French theory (qui était d’ailleurs moins une théorie qu’une mode intellectuelle).

Le bricolage des mythes remplace le mythe du progrès. L’idéologie du progrès, le scientisme, le positivisme avaient amené à l’éclipse des images mythiques au profit des croyances en la science, amenant à des connaissances claires, précises, chiffrées des phénomènes. Jacob Taubes, dans ses deux livres qui évoquent Carl Schmitt (En divergent accord et La théologie politique de Paul), a noté que le mythe, qui parle au corps a été remplacé par la croyance en la science, qui parle à la raison. Selon Maffesoli, un mouvement de balancier nous ramène vers le corps, nous reconduit vers les sens, vers ce qui est incarné, plus que vers ce qui est prouvé (scientifiquement). Le même mouvement qui nous éloigne des progressismes nous éloigne des messianismes (juif, chrétien, musulman). Aux messianismes qui nous font miroiter une vie future parfaite, succède une sagesse qui renoue avec l’antique, avec Epicure et Lucrèce, et avec la Stoia (le Portique, l’école des stoïciens), et qui consiste à faire avec ce qui est, et à s’accorder aux autres tels qu’ils sont, et avec soi-même tel que l’on est (ce qui est sans doute plus difficile).

Il s’agit non seulement d’accepter, mais d’avoir plaisir de vivre dans la « fédération bruissante » (Maurice Barrès) de la communauté des hommes. Il s’agit de réévaluer le quotidien. Les tribus urbaines remplacent l’homme seul dans la foule. Les techniques qui avaient désenchanté le monde le réenchantent, en créant des lieux symboliques via internet. Et des liens à la suite des lieux. Les cybertribus « développent des pratiques communautaires qui peuvent être rangées sous la rubrique de l’immoralisme éthique » (morale et éthique étant le même mot dans des langues différentes, l’expression de Maffesoli est tautologique).

« Le néo-tribalisme postmoderne pourrait permettre une coexistence des appartenances au sein d’un même individu […] », écrit Hélène Strohl. Il permettrait que l’individu ne soit pas assigné à une seule identité. Ce n’est pas douteux, mais ce n’est pas du tout nouveau. L’identité professionnelle, par exemple, s’est toujours superposée à d’autres identités, ou identifications, religieuse, sexuelles, artistiques, etc. Toute la théorie de Ricoeur sur l’identité idem et l’identité ipsé, réunies dans l’identité narrative, explique cela. Ce qui est frappant avec Maffesoli, c’est que les communautés sont toujours là pour permettre à l’individu de s’épanouir. Qu’un individu soit un faisceau d’identités (culturelles, professionnelles, sportives, amoureuses, etc), cela n’est pas douteux. Personne n’y voit d’inconvénient, à une condition toutefois : il y a aussi des conditions politiques à l’épanouissement de l’individu. Et c’est là le grand impensé de Maffesoli. Or, ce n’est pas simple d’éviter la question du politique. Le court terme, qui est le plaisir de l’individu, peut être en contradiction avec le long terme, qui est la préservation d’un cadre de civilisation, et de repères culturels commun à toute une société, à toute une nation, qui, par définition, est une construction à long terme. Et c’est bien là le problème auquel se heurte Maffesoli. Du moins auquel il devrait se heurter, en toute logique. Mais il ne s'y heurte pas car il l’esquive. Il l’esquive car il n’aime pas la logique, et parce qu’il n’est pas frontal, en bon postmoderne qu’il est.

La condition d’existence des communautés choisies, affectionnées par Maffesoli, c’est la pérennité d’un certain cadre civilisationnel. La juxtaposition des communautés, cela ne marche qu’un temps. Cela ne marche plus quand la communauté nationale cesse d’exister. Nos auteurs nous disent qu’il faut accepter la coexistence de plusieurs appartenances. On peut évidemment être un bon Français et être attaché à son village natal, qu’il soit européen ou extra-européen. Mais que se passe-t-il quand les appartenances se disputent un même individu ? Ou quand ces appartenances se hiérarchisent de la façon suivante : la France pour les droits sociaux et les avantages, la patrie d’origine pour les affections ? Que se passe-t-il quand l’appartenance à la France n’est mise en avant que pour les avantages sociaux, matériels, le droit au logement, la gratuité des soins, etc, et que le moindre événement sportif dit que les attachements ne vont jamais à la France, voire sont dressés contre elle ? Chacun sait que ces cas ne sont pas rares. Et ils sont tout le problème de l’immigration.

Maffesoli explique que le postmoderne est le retour du prémoderne. C’est effectivement vrai. C’est le retour à une situation anténationale, avant les Etats-nations. Or, être Français, c’est, qu’on le veuille ou non, appartenir à une nation. A une nation politique. Que celle-ci ait vocation à intégrer une « Europe indépendante », comme disait le général de Gaulle, par la création d’une confédération préservant un certain art de vivre, ce que l’on appelle une civilisation, cela ne fait, pour moi, pas de doute. Encore faut-il ne pas revenir au temps des tribus et des allégeances féodales. Si elles préparent un Empire, c’est toujours l’Empire des autres. C’est la domination de notre pays par un Empire étranger qu’elles préparent. Une domination pas forcément physique, mais qui pourrait bien être mentale. Et qui peut être celle dont il est le plus difficile de se libérer.

Le pluralisme ontologique, ou tout simplement ce que Max Weber appelait le « polythéisme des valeurs » amène à ce qu’il ne soit plus possible de croire au Progrès – qui est par définition unique, comme un train lancé sur une seule voie. Le contraire du progrès n’est évidemment pas la régression, ou la réaction, bien qu’il soit nécessaire et sain de réagir : la réaction à un médicament veut dire qu’il fait de l’effet. Reste à savoir si c’est le bon effet. Qu’est-ce que le Progrès ? Avec un grand P cela veut dire l’idéologie du progrès, et même la religion du progrès. Le contraire du Progrès, ce n’est donc pas la régression, c’est le sens des limites. Le contraire de l’idéologie du progrès, c’est de penser aussi aux dégâts du progrès, c’est de refuser la démesure (hubris). C’est le sentiment que le progrès ne peut être sans fin, qu’il ne peut être un mouvement vers toujours plus d’arraisonnement du monde, c’est préférer Alain Finkielkraut à Philippe Forget (et Alain de Benoist à Guillaume Faye). C’est se retrouver dans les idées de Jean-Paul Dollé plus que dans celles de Luc Ferry (au demeurant excellent pédagogue). C’est préférer Robert Redeker à Michel Serres (d’un optimisme déprimant), et Sylviane Agacinski à Frédéric Worms (que l’on préfère en spécialiste de Bergson plus qu’en spécialiste de la bioéthique). Or, ce qui est très caractéristique de Michel Maffesoli, c’est que, se réjouissant de ce qu’il croit être un abandon de l’idée de progrès, il n’entre pas dans les débats évoqués ci-dessus. Ce qu’il refuse de penser, c’est que c’était mieux avant, en tout cas dans certains domaines : l’éducation, la civilité, la sécurité, le prix des logements par rapport aux salaires, la qualité de vie sociale, même et surtout dans les quartiers populaires, le contrôle plus léger dans tous les actes de la vie, auquel a succédé un flicage généralisé, l’élitisme républicain qui vaut mieux que l’ascension sociale parce que l’on est issu « de la diversité » [ce qui veut dire en clair que l’on n’est pas d’origine française]. C’était mieux avant dans tout ce qui compte pour les classes populaires, celles qui ne peuvent se protéger de l’ensauvagement des quartiers de banlieues.

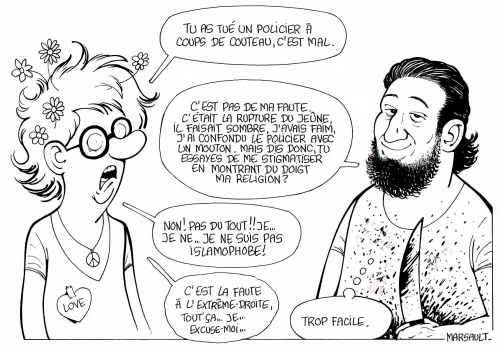

Renversant la charge des responsabilités, Maffesoli estime que « l’islamisme est relié à l’absence de bienveillance [des pouvoirs publics] envers les religions de communautés immigrés ». Etonnante remarque. N’a-t-il pas vu les affichages « bon ramadan », pour la rupture du jeune, sur les panneaux de Paris et d’autres grandes villes (et même une vidéo des joueurs du PSG !), ces grandes villes fiefs des « bobos », bastions du politiquement correct et de la pensée unique « diversitaire », et vivier de l’électoral Macron ? Ces grandes villes dont la plupart ne souhaitent à personne de « joyeuses Pâques ? Selon Maffesoli, il faut répondre à l’islamisme et aux autres extrémismes par… le relativisme, par exemple en leur laissant la possibilité de défiler. On croit rêver. Car s’il y a une différence entre l’islam et l’islamisme (je le crois, au sens où l’islamisme est un djihadisme), c’est bien que l’Islam est une religion et une civilisation (il faut alors mettre une majuscule : Islam), et si l’islamisme est autre chose, il est une volonté conquérante d’islamisation forcée. Nous savons cela. Il fut un temps où le christianisme aussi était expansionniste. Faut-il donc autoriser de telles manifestations islamistes ? Croit-on que cela ne nous mènerait pas tout droit à la guerre civile ? Nos sociétés ne sont-elles pas déjà excessivement relativistes ?

Exemple. Le respect de la possibilité de pratiquer sa religion est assuré en France, alors que ce respect n’a pas son équivalent dans les pays musulmans (être chrétien en pays musulman est souvent impossible), c’est déjà beaucoup, et c’est très bien comme cela. Nous acceptons une non réciprocité. C’est énorme. Et il faudrait aller encore plus loin, nous dit Maffesoli ? On rêve, ou on fait un cauchemar, car on sait comment se terminent les capitulations, par des capitulations encore plus grandes. Il serait encore mieux que notre tolérance soit comprise comme un acte de générosité, et non de faiblesse. Ce serait folie que d’aller au-delà. La générosité deviendrait asservissement et masochisme.

Maffesoli cite justement, en l’approuvant, Goethe (Le second Faust) « la frisson sacré est la meilleur part de l’humanité ». Il faut donc proposer du sacré, de la mystique, de l’engagement passionné, qui est tout le contraire du relativisme, de l’extrême tolérance que propose Maffesoli. On ne répond à un plein – et l’islamisme est un plein, et l’islam tout court aussi – que par un autre plein. Certainement pas par le vide des valeurs d’un laïcisme pitoyable, certainement pas par un patriotisme mou, certainement pas par des incantations à une République en oubliant de dire que la république est admirable quand c’est la République française, et que n’avons que faire d’une république de nulle part.

La fin de l’idée de progrès, c’est la fin de la Raison surplombante, et c’est la fin de la verticalité. Il s’agit désormais non pas de contracter avec l’autre (le contrat social), mais de le renifler, car si l’homme n’est pas qu’un animal, il est aussi un animal, affirment les auteurs. Bien sûr, personne de sensé ne dit le contraire. Du reste, c’est l’évacuation de l’animalité de l’homme qui a abouti à la bestialité (dans les camps de concentration), dit Maffesoli. Le point de vue est unilatéral. L’animalité est du côté du bien, la culture du côté du mal. Mais la nature de l’homme, c’est sa culture. Quant à l’animalité, elle est non pas du côté du bien, mais au-delà du bien et du mal.

La modernité était selon Maffesoli marquée par la verticalité, la postmodernité est marquée par l’horizontalité. La modernité connaissait les religions, la postmodernité connait le sacral. Ou le reconnait à nouveau, comme avec les prémodernes Mais que dit Maffesoli de la place croissante de l’islam en France ? Ce n’est pourtant du sacral, c’est une religion au sens classique, avec ses rites. Silence de l’auteur sur cette contradiction entre sa théorie et ce que nous voyons.

« L’assomption de l’individualisme était l’essentielle spécificité de l’époque moderne », et la montée des communautés serait le signe de l’entrée en postmodernité. Mais de quelles communautés parle-t-on ? M. Maffesoli et Mme Strohl ne les voient pas comme une façon de rétablir des continuités, des permanences. Ce sont des appartenances éphémères, et ce ne sont pas toujours des appartenances. « Les communautés soulignent l’importance du nomadisme comme structure anthropologique indépassable ». Le nomadisme « est une structure anthropologique retrouvant une vigueur nouvelle » dans les moments de décadence (p. 167). En haut, le nomadisme des traders, d’un hôtel international à un autre, en bas, le nomadisme des migrants, des « réfugiés », vrais ou faux, des « mineurs isolés » dont on conviendra qu’ils sont rarement isolés, et souvent moins mineurs qu’ils le disent.

Que le nomadisme soit le principal vecteur d’une communauté retrouvée laisse pour le moins dubitatif. Ce fut certes le cas au Sahara, avec les bédouins, ou dans les tribus mongoles. Cela fait tout de même un certain temps que, en Europe, les communautés se forment sur d’autres bases.

Dans le même temps, Maffesoli manifeste sa sympathie pour les Gilets Jaunes. Ceux-ci représentent une forme de retour du lien social. Des gens qui étaient isolés (mais comme nous vivons dans une époque postmoderne, nous avions cru comprendre à la lecture de Maffesoli que les isolés n’étaient que des faux isolés ?) retrouvent le plaisir du lien social. Les auteurs ont raison de saluer ce phénomène. Toutefois, on ne voit pas le lien entre ces nouvelles communautés que furent les Gilets Jaunes et le goût du nomadisme. Tout au contraire, les Gilets Jaunes témoignent du besoin de retrouver des repères, de ne plus se sentir étranger chez soi, de retrouver des stabilités et des ancrages. C’est tout le contraire du nomadisme qui caractérise les « bobos » urbains de centre-ville. Les communautés de Maffesoli sont des communions de circonstances. Les auteurs l’écrivent : « L’idéal communautaire est présentéiste ». Les solitaires « ne sont jamais isolés », croient savoir les auteurs (p. 154), car ils sont toujours en lien avec les autres, devant leur ordinateur, leur tablette, ou leur smartphone. Singulier optimisme. Combien de nos compatriotes vivent tristement de contacts virtuels déréalisants ? Ou d’une solitude complète. Combien de personnes agées que leurs enfants ne visitent jamais ? Au lieu de se pencher sur cette hypothèse comme quoi l’individu isolé serait toujours une réalité très répandue de nos sociétés, nos auteurs renvoient la critique de la vacuité de certains tribus à du ressentiment et à de la jalousie devant la « chaleur » du groupe. Eh bien oui, rollers, trottinettes et autres véhicules bizarres, aussi vite apparus que démodés, et encombrant les trottoirs, me paraissent participer du crétinisme à roulettes, dont la panoplie comporte généralement un casque, pour écouter sinon de la musique, du moins du « son ». De même, airbnb, blablacar et autres réseaux sociaux sont approuvés sans réserve par Maffesoli. Ils seraient une reliance. Ils « constituent la communion des saints postmoderne ». Rien que cela. On n’est pas obligé d’être convaincu par cette formule dont l’inattendu n’implique pas une quelconque justesse.

Certes, ces outils de partage de véhicules, ou de chambres, rendent à coup sûr bien des services, alliant l’intérêt financier à des contacts humains qui peuvent être sympathiques, bien que la plupart du temps, très superficiels. Mais nos auteurs oublient une caractéristique de tous ces réseaux. C’est la notation, ce sont les « étoiles » à affecter à chaque « partenaire », c’est la mise en ligne des « avis », ce sont les commentaires qui sont publics, etc. C’est la tyrannie de la transparence. Et alors que les auteurs critiquent les concours, ils font l’éloge des réseaux, qui impliquent un système de notation beaucoup plus inquisitorial que n’importe quel concours, une dictature de la transparence, intrusive, et plus injuste que n’importe quel concours. Les réseaux sociaux ? C’est le grand panoptique. Faire leur apologie ? C’est tuer l’intimité, la pudeur, le quant à soi. Au profit des ego, du tank à soi.

Certes, ces outils de partage de véhicules, ou de chambres, rendent à coup sûr bien des services, alliant l’intérêt financier à des contacts humains qui peuvent être sympathiques, bien que la plupart du temps, très superficiels. Mais nos auteurs oublient une caractéristique de tous ces réseaux. C’est la notation, ce sont les « étoiles » à affecter à chaque « partenaire », c’est la mise en ligne des « avis », ce sont les commentaires qui sont publics, etc. C’est la tyrannie de la transparence. Et alors que les auteurs critiquent les concours, ils font l’éloge des réseaux, qui impliquent un système de notation beaucoup plus inquisitorial que n’importe quel concours, une dictature de la transparence, intrusive, et plus injuste que n’importe quel concours. Les réseaux sociaux ? C’est le grand panoptique. Faire leur apologie ? C’est tuer l’intimité, la pudeur, le quant à soi. Au profit des ego, du tank à soi.

Les communautés postmodernes ne sont pas non plus en tension vers quelque chose qui nous dépasse. Les auteurs voient les communautés comme résolument immanentes. Ils ont certainement raison de voir la condition postmoderne définitivement au-delà de tout péché originel. Reste que la fin du péché originel n’est pas la fin de toute verticalité. Elle ne devrait, en tout cas, pas l’être car aucun monde humain ne peut se passer de verticalité.

Nous serions passés de la raison au corps, du calcul à l’instinct. Du devoir-être rigide à l’invention libre de soi. De l’universalisme des droits de l’homme au particularisme des droits des tribus. De la raison normée au bricolage des justifications, de la Morale unique à des morales par tribus, voire à des morales par situations, validées par des groupes d’appartenance restreints, et non par la société toute entière.

Il nous faudrait nous réjouir de l’affaiblissement de la culture des « concours ». Fort bien. Mais si les concours ne sont pas toujours la solution idéale, que mettre à la place ? Le copinage, les relations ? Nous savons que celles-ci jouent un rôle, mais n’est-il pas justement utile de limiter ce rôle par des concours ? On en arrive au thème de l’élitisme républicain, et on comprend ici que c’est justement ce qui n’est pas du goût de nos auteurs « postmodernes ». Et pourtant, qu’obtient-on quand on abandonne l’élitisme républicain ? M. Benalla et M. Castaner. A la place de M. Chevènement, ou de M. Peyrefitte. Ils ne sont pas dépourvus d’entregent. Est-ce le seul critère qui doit prévaloir ? Est-ce préférable à un vieux serviteur de l’Etat, qui aurait un peu plus de crédibilité ? Quand Maffesoli oppose le katholon, c’est-à-dire tout simplement la totalité de ce que nous partageons à l’universalisme, en quoi cela nous fournit-il une solution ? La mise sur le marché des idées d’un terme peu usité ne peut tenir lieu de solution. Car le bien commun à tous renvoie toujours à ce qu’est ce « tous ». S’agit-il d’une simple communauté d’affinités sportives, sexuelles, éducatives, etc ? S’agit-il d’une communauté de « gamers » ? De « traders » ? De LGBT ? Que ces communautés existent ne pose aucun problème. La socialité passe partout et cela donne des communautés, plus ou moins conflictuelles du reste, et cela est très bien ainsi. Mais ces communautés restreintes ne remplacent pas des communautés plus vastes. Dans les communautés postmodernes, il ne s’agit jamais de la nation, de notre patrie, puisqu’elle transcenderait toutes les communautés, et que nulle transcendance n’est admise dans le paradis postmoderne, le « seul et vrai paradis », celui de l’horizontalité infinie.

Mais alors, qu’est-ce qui fait sens pour nous tous ? La réponse est que nous sommes devant un pur néant. Celui-ci ne peut que légitimer la déconstruction de tout Etat. Si rien ne nous rassemble en peuple, pourquoi un garant de ce rassemblement ? Mais si l’Etat n’est pas à lui tout seul le garant du bien commun, ni même l’unique élément d’un ordre public, il en est l’un des piliers. L’Etat ne doit pas être tout, mais il couronne le tout. Déconstruire tout Etat, c’est sortir de l’histoire, en d’autres termes, c’est devenir colonisés, c’est devenir sujet de l’histoire des autres. « L’anarchie, c’est l’ordre sans l’Etat », disaient Elisée Reclus et P-J Proudhon. Mais quand règne, dans de nombreux quartiers, une forme d’ensauvagement, ce n’est le moment de supprimer l’Etat, dont l’une des fonctions essentielles est la sécurité du peuple, aussi bien la sécurité intérieure que la sécurité extérieure (on peut certes imaginer des « tribus » de sociétés privées de sécurité, et de gardes du corps, et d’ailleurs, elles existent déjà, mais la sécurité est alors proportionnelle aux moyens financiers).

Mais alors, qu’est-ce qui fait sens pour nous tous ? La réponse est que nous sommes devant un pur néant. Celui-ci ne peut que légitimer la déconstruction de tout Etat. Si rien ne nous rassemble en peuple, pourquoi un garant de ce rassemblement ? Mais si l’Etat n’est pas à lui tout seul le garant du bien commun, ni même l’unique élément d’un ordre public, il en est l’un des piliers. L’Etat ne doit pas être tout, mais il couronne le tout. Déconstruire tout Etat, c’est sortir de l’histoire, en d’autres termes, c’est devenir colonisés, c’est devenir sujet de l’histoire des autres. « L’anarchie, c’est l’ordre sans l’Etat », disaient Elisée Reclus et P-J Proudhon. Mais quand règne, dans de nombreux quartiers, une forme d’ensauvagement, ce n’est le moment de supprimer l’Etat, dont l’une des fonctions essentielles est la sécurité du peuple, aussi bien la sécurité intérieure que la sécurité extérieure (on peut certes imaginer des « tribus » de sociétés privées de sécurité, et de gardes du corps, et d’ailleurs, elles existent déjà, mais la sécurité est alors proportionnelle aux moyens financiers).

Dans une optique purement communautaire, et en fait communautariste, ce que « nous » partageons ne renvoie qu’à de petites communautés qui ne font pas l’histoire. C’est-à-dire qu’elles subissent l’histoire. Il n’y a pas, ici, de troisième voie : l’histoire, on la fait, ou on la subit. La postmodernité que défend Michel Maffesoli, c’est encore la loi des frêres qui succède à la loi des pères. Les pairs plutôt que les pères. Mais c’est justement de cette mise à égalité que notre société meurt. Les pairs sont nécessaires. Mais les pères demeurent indispensables. Les pairs ne peuvent suppléer aux pères. Les apprenants sont mis sur le même plan que les professeurs, les conseils d’élèves doublonnent les structures d’adultes. Au final, tout le monde étant responsable de tout, plus personne n’est responsable de rien.

Enfin, les pairs ne sont pas une invention de la postmodernité. Qu’était un syndicat ? Sinon un regroupement entre pairs. Que sont les Gilets Jaunes ? Sinon des pairs. Les Gilets Jaunes sont plus proches des mouvements de la modernité militante que de la postmodernité « cool » et sage et ludique. Par le simple fait qu’ils ont le sentiment clair des mensonges du pouvoir, les Gilets Jaunes ne sont pas postmodernes. Dans ce cas, ils ne croiraient à aucune vérité, donc à aucun mensonge. Dans le monde postmoderne, il n’y a plus de distinction entre honnêteté et malhonnêteté. C’est exactement cela qui créait le désespoir de Wittgenstein, le sentiment que l’honnêteté n’est plus possible intellectuellement dans un monde postmoderne redevenu antésocratique, tandis que, anthropologiquement, Wittgenstein se sentait hanté par la question de l’honnêteté.

Les temps postmodernes ne sont plus à la croyance en la vérité. Ce qui amène la fin de la croyance en une justice, et en un bien commun. Le commun n’est plus que partiel : les usagers de trottinettes, la « communauté » blablacar, etc. Les tribus sont un moyen de développer du collectif sans politique. C’est-à-dire de laisser le pouvoir aux puissances d’argent. C’est pour cela que les fondés de pouvoir du Capital, qu’ils s’appellent Macron un jour ou Tartempion le lendemain les aiment tant.

Pierre Le Vigan

Michel Maffesoli et Hélène Strohl, La faillite des élites, 228 p., Lexio, 2019.

En 1991, dans sa très pointue Guerre du Golfe qui n’a pas eu lieu, Baudrillard se lâchait en fin de texte. Je retraduis de la version espagnole :

En 1991, dans sa très pointue Guerre du Golfe qui n’a pas eu lieu, Baudrillard se lâchait en fin de texte. Je retraduis de la version espagnole :

Sourcé et documenté, mais en même temps décapant sans concessions et affranchi de tous les conventionnalismes, ce livre atypique sort résolument des sentiers battus de l’histoire des idées politiques. Son auteur, Dalmacio Negro Pavón, politologue renommé dans le monde hispanique, est au nombre de ceux qui incarnent le mieux la tradition académique européenne, celle d’une époque où le politiquement correct n’avait pas encore fait ses ravages, et où la majorité des universitaires adhéraient avec conviction, – et non par opportunisme comme si souvent aujourd’hui -, aux valeurs scientifiques de rigueur, de probité et d’intégrité. Que nous dit-il ? Résumons-le en puisant largement dans ses analyses, ses propos et ses termes:

Sourcé et documenté, mais en même temps décapant sans concessions et affranchi de tous les conventionnalismes, ce livre atypique sort résolument des sentiers battus de l’histoire des idées politiques. Son auteur, Dalmacio Negro Pavón, politologue renommé dans le monde hispanique, est au nombre de ceux qui incarnent le mieux la tradition académique européenne, celle d’une époque où le politiquement correct n’avait pas encore fait ses ravages, et où la majorité des universitaires adhéraient avec conviction, – et non par opportunisme comme si souvent aujourd’hui -, aux valeurs scientifiques de rigueur, de probité et d’intégrité. Que nous dit-il ? Résumons-le en puisant largement dans ses analyses, ses propos et ses termes: Une révolution a besoin de dirigeants, mais l’étatisme a infantilisé la conscience des Européens. Celle-ci a subi une telle contagion que l’émergence de véritables dirigeants est devenue quasiment impossible et que lorsqu’elle se produit, la méfiance empêche de les suivre. Mieux vaut donc, une fois parvenu à ce stade, faire confiance au hasard, à l’ennui ou à l’humour, autant de forces historiques majeures, auxquelles on n’accorde pas suffisamment d’attention parce qu’elles sont cachées derrière le paravent de l’enthousiasme progressiste.

Une révolution a besoin de dirigeants, mais l’étatisme a infantilisé la conscience des Européens. Celle-ci a subi une telle contagion que l’émergence de véritables dirigeants est devenue quasiment impossible et que lorsqu’elle se produit, la méfiance empêche de les suivre. Mieux vaut donc, une fois parvenu à ce stade, faire confiance au hasard, à l’ennui ou à l’humour, autant de forces historiques majeures, auxquelles on n’accorde pas suffisamment d’attention parce qu’elles sont cachées derrière le paravent de l’enthousiasme progressiste. Le réaliste authentique affirme que la finalité propre à la politique est le bien commun, mais il reconnait la nécessité vitale des finalités non politiques(le bonheur et la justice). La politique est selon lui au service de l’homme. La mission de la politique n’est pas de changer l’homme ou de le rendre meilleur (ce qui est le chemin des totalitarismes), mais d’organiser les conditions de la coexistence humaine, de mettre en forme la collectivité, d’assurer la concorde intérieure et la sécurité extérieure. Voilà pourquoi les conflits doivent être, selon lui, canalisés, réglementés, institutionnalisés et autant que possible résolus sans violence.

Le réaliste authentique affirme que la finalité propre à la politique est le bien commun, mais il reconnait la nécessité vitale des finalités non politiques(le bonheur et la justice). La politique est selon lui au service de l’homme. La mission de la politique n’est pas de changer l’homme ou de le rendre meilleur (ce qui est le chemin des totalitarismes), mais d’organiser les conditions de la coexistence humaine, de mettre en forme la collectivité, d’assurer la concorde intérieure et la sécurité extérieure. Voilà pourquoi les conflits doivent être, selon lui, canalisés, réglementés, institutionnalisés et autant que possible résolus sans violence.

Cela étant, on peut être un sceptique ou un pessimiste lucide mais refuser pour autant de désespérer. On ne peut pas éliminer les oligarchies. Soit ! Mais, comme nous le dit Dalmacio Negro Pavón, il y a des régimes politiques qui sont plus ou moins capables d’en mitiger les effets et de les contrôler. Le nœud de la question est d’empêcher que les détenteurs du pouvoir ne soient que de simples courroies de transmission des intérêts, des désirs et des sentiments de l’oligarchie politique, sociale, économique et culturelle. Les hommes craignent toujours le pouvoir auquel ils sont soumis, mais le pouvoir qui les soumet craint lui aussi toujours la collectivité sur laquelle il règne. Et il existe une condition essentielle pour que la démocratie politique soit possible et que sa corruption devienne beaucoup plus difficile sinon impossible, souligne encore Dalmacio Negro Pavón. Il faut que l’attitude à l’égard du gouvernement soit toujours méfiante, même lorsqu’il s’agit d’amis ou de personnes pour lesquelles on a voté. Bertrand de Jouvenel disait à ce propos très justement: « le gouvernement des amis est la manière barbare de gouverner ».

Cela étant, on peut être un sceptique ou un pessimiste lucide mais refuser pour autant de désespérer. On ne peut pas éliminer les oligarchies. Soit ! Mais, comme nous le dit Dalmacio Negro Pavón, il y a des régimes politiques qui sont plus ou moins capables d’en mitiger les effets et de les contrôler. Le nœud de la question est d’empêcher que les détenteurs du pouvoir ne soient que de simples courroies de transmission des intérêts, des désirs et des sentiments de l’oligarchie politique, sociale, économique et culturelle. Les hommes craignent toujours le pouvoir auquel ils sont soumis, mais le pouvoir qui les soumet craint lui aussi toujours la collectivité sur laquelle il règne. Et il existe une condition essentielle pour que la démocratie politique soit possible et que sa corruption devienne beaucoup plus difficile sinon impossible, souligne encore Dalmacio Negro Pavón. Il faut que l’attitude à l’égard du gouvernement soit toujours méfiante, même lorsqu’il s’agit d’amis ou de personnes pour lesquelles on a voté. Bertrand de Jouvenel disait à ce propos très justement: « le gouvernement des amis est la manière barbare de gouverner ».

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

La période qui s’étend du IIIe siècle de l’ère chrétienne au VIe, ce qu’il est convenu d’appeler, depuis les débuts de l’Âge moderne, le passage de l’Antiquité gréco-romaine au Moyen Âge (ou Âges gothiques), fait l’objet, depuis quelques années, d’un intérêt de plus en plus marqué de la part de spécialistes, mais aussi d’amateurs animés par la curiosité des choses rares, ou poussés par des besoins plus impérieux. De nombreux ouvrages ont contribué à jeter des lueurs instructives sur un moment de notre histoire qui avait été négligée, voire méprisée par les historiens. Ainsi avons-nous pu bénéficier, à la suite des travaux d’un Henri-Irénée Marrou, qui avait en son temps réhabilité cette époque prétendument « décadente », des analyses érudites et perspicaces de Pierre Hadot, de Lucien Jerphagnon, de Ramsay MacMullen, de Christopher Gérard et d’autres, tandis que les ouvrages indispensable, sur la résistance païenne, de Pierre de Labriolle et d’Alain de Benoist étaient réédités. Polymnia Athanassiadi, professeur d’histoire ancienne à l’Université d’Athènes, a publié, en 2006, aux éditions Les Belles Lettres, une recherche très instructive, La Lutte pour l’orthodoxie dans le platonisme tardif, que je vais essayer de commenter.

La période qui s’étend du IIIe siècle de l’ère chrétienne au VIe, ce qu’il est convenu d’appeler, depuis les débuts de l’Âge moderne, le passage de l’Antiquité gréco-romaine au Moyen Âge (ou Âges gothiques), fait l’objet, depuis quelques années, d’un intérêt de plus en plus marqué de la part de spécialistes, mais aussi d’amateurs animés par la curiosité des choses rares, ou poussés par des besoins plus impérieux. De nombreux ouvrages ont contribué à jeter des lueurs instructives sur un moment de notre histoire qui avait été négligée, voire méprisée par les historiens. Ainsi avons-nous pu bénéficier, à la suite des travaux d’un Henri-Irénée Marrou, qui avait en son temps réhabilité cette époque prétendument « décadente », des analyses érudites et perspicaces de Pierre Hadot, de Lucien Jerphagnon, de Ramsay MacMullen, de Christopher Gérard et d’autres, tandis que les ouvrages indispensable, sur la résistance païenne, de Pierre de Labriolle et d’Alain de Benoist étaient réédités. Polymnia Athanassiadi, professeur d’histoire ancienne à l’Université d’Athènes, a publié, en 2006, aux éditions Les Belles Lettres, une recherche très instructive, La Lutte pour l’orthodoxie dans le platonisme tardif, que je vais essayer de commenter. Pendant ces temps très troublés, où l’Empire accuse les assauts des Barbares, s’engage dans un combat sans merci avec l’ennemi héréditaire parthe, où le centre du pouvoir est maintes fois disloqué, amenant des guerres civiles permanentes, où la religiosité orientale mine l’adhésion aux dieux ancestraux, l’hellénisme (qui est la pensée de ce que Paul Veyne nomme l’Empire gréco-romain) est sur la défensive. Il lui faut trouver une formule, une clé, pour sauver l’essentiel, la terre et le ciel de toujours. Nous savons maintenant que c’était un combat vain (en apparence), en tout cas voué à l’échec, dès lors que l’État allait, par un véritable putsch religieux, imposer le culte galiléen. Durant trois ou quatre siècles, la bataille se déroulerait, et le paganisme perdrait insensiblement du terrain. Puis on se réveillerait avec un autre ciel, une autre terre. Comme le montre bien Polymnia Athanassiadi, cette « révolution » se manifeste spectaculairement dans la relation qu’on cultive avec les morts : de la souillure, on passe à l’adulation, au culte, voire à l’idolâtrie des cadavres.

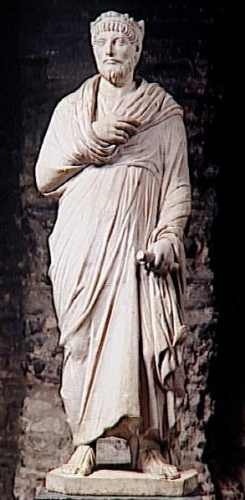

Pendant ces temps très troublés, où l’Empire accuse les assauts des Barbares, s’engage dans un combat sans merci avec l’ennemi héréditaire parthe, où le centre du pouvoir est maintes fois disloqué, amenant des guerres civiles permanentes, où la religiosité orientale mine l’adhésion aux dieux ancestraux, l’hellénisme (qui est la pensée de ce que Paul Veyne nomme l’Empire gréco-romain) est sur la défensive. Il lui faut trouver une formule, une clé, pour sauver l’essentiel, la terre et le ciel de toujours. Nous savons maintenant que c’était un combat vain (en apparence), en tout cas voué à l’échec, dès lors que l’État allait, par un véritable putsch religieux, imposer le culte galiléen. Durant trois ou quatre siècles, la bataille se déroulerait, et le paganisme perdrait insensiblement du terrain. Puis on se réveillerait avec un autre ciel, une autre terre. Comme le montre bien Polymnia Athanassiadi, cette « révolution » se manifeste spectaculairement dans la relation qu’on cultive avec les morts : de la souillure, on passe à l’adulation, au culte, voire à l’idolâtrie des cadavres. Que le monothéisme sémitique ait agi sur ce recentrement du divin sur lui-même, à sa plus simple unicité, cela est plus que probable, surtout dans cette Asie qui accueillait tous les brassages de populations et de doctrines, pour les déverser dans l’Empire. Néanmoins, il est faux de prétendre que le néoplatonisme fût une variante juive du platonisme. Il est au contraire l’aboutissement suprême de l’hellénisme mystique. Comme les Indiens, que Plotin ambitionnait de rejoindre en accompagnant en 238 l’expédition malheureuse de Gordien II contre le roi perse Chahpour, l’Un peut se concilier avec la pluralité. Jamblique place les dieux tout à côté de Dieu. Plus tard, au Ve siècle, Damascius, reprenant la théurgie de Jamblique et l’intellectualité de Plotin (IIIe siècle), concevra une voie populaire, rituelle et cultuelle, nécessairement plurielle, et une voie intellective, conçue pour une élite, quêtant l’union avec l’Un. Le pèlerinage, comme sur le mode chrétien, sera aussi pratiqué par les païens, dans certaines villes « saintes », pour chercher auprès des dieux le salut.

Que le monothéisme sémitique ait agi sur ce recentrement du divin sur lui-même, à sa plus simple unicité, cela est plus que probable, surtout dans cette Asie qui accueillait tous les brassages de populations et de doctrines, pour les déverser dans l’Empire. Néanmoins, il est faux de prétendre que le néoplatonisme fût une variante juive du platonisme. Il est au contraire l’aboutissement suprême de l’hellénisme mystique. Comme les Indiens, que Plotin ambitionnait de rejoindre en accompagnant en 238 l’expédition malheureuse de Gordien II contre le roi perse Chahpour, l’Un peut se concilier avec la pluralité. Jamblique place les dieux tout à côté de Dieu. Plus tard, au Ve siècle, Damascius, reprenant la théurgie de Jamblique et l’intellectualité de Plotin (IIIe siècle), concevra une voie populaire, rituelle et cultuelle, nécessairement plurielle, et une voie intellective, conçue pour une élite, quêtant l’union avec l’Un. Le pèlerinage, comme sur le mode chrétien, sera aussi pratiqué par les païens, dans certaines villes « saintes », pour chercher auprès des dieux le salut.

Polymnia Athanassiadi, professeur d’histoire ancienne à l’Université d’Athènes, spécialiste du platonisme tardif (le néoplatonisme) avait bousculé quelques certitudes, dans son ouvrage publié en 2006, « la lutte pour l’orthodoxie dans le platonisme tardif », en montrant que les structures de pensée dans l’Empire gréco-romain, dont l’aboutissement serait la suppression de toute possibilité discursive au sein de l’élite intellectuelle, étaient analogues chez les philosophes « païens » et les théologiens chrétiens. Cette osmose, à laquelle il était impossible d’échapper, se retrouve au niveau des structures politiques et administratives, avant et après Constantin. L’État « païen », selon Mme Athanassiadi, prépare l’État chrétien, et le contrôle total de la société, des corps et des esprits. C’est la thèse contenue dans une étude éditée en 2010, Vers la pensée unique. La montée de l’intolérance dans l’Antiquité tardive.

Polymnia Athanassiadi, professeur d’histoire ancienne à l’Université d’Athènes, spécialiste du platonisme tardif (le néoplatonisme) avait bousculé quelques certitudes, dans son ouvrage publié en 2006, « la lutte pour l’orthodoxie dans le platonisme tardif », en montrant que les structures de pensée dans l’Empire gréco-romain, dont l’aboutissement serait la suppression de toute possibilité discursive au sein de l’élite intellectuelle, étaient analogues chez les philosophes « païens » et les théologiens chrétiens. Cette osmose, à laquelle il était impossible d’échapper, se retrouve au niveau des structures politiques et administratives, avant et après Constantin. L’État « païen », selon Mme Athanassiadi, prépare l’État chrétien, et le contrôle total de la société, des corps et des esprits. C’est la thèse contenue dans une étude éditée en 2010, Vers la pensée unique. La montée de l’intolérance dans l’Antiquité tardive. Polymnia Athanassiadi rappelle les influences qui ont pu marquer cette conception positive : elle a été élaborée durant une époque où la détente d’après-guerre devenait possible, où l’individualisme se répandait, avec l’hédonisme qui l’accompagne inévitablement, où le pacifisme devient, à la fin années soixante, la pensée obligée de l’élite. De ce fait, les conflits sont minimisés.

Polymnia Athanassiadi rappelle les influences qui ont pu marquer cette conception positive : elle a été élaborée durant une époque où la détente d’après-guerre devenait possible, où l’individualisme se répandait, avec l’hédonisme qui l’accompagne inévitablement, où le pacifisme devient, à la fin années soixante, la pensée obligée de l’élite. De ce fait, les conflits sont minimisés.

Notons que Julien, le restaurateur du paganisme d’État, est mis sur le même plan que Constantin et que ses successeurs chrétien. En voulant créer une « Église païenne », en se mêlant de théologie, en édictant des règles de piété et de moralité, en excluant épicuriens, sceptiques et cyniques, il a consolidé la cohérence théologico-autoritaire de l’Empire. Il assumait de ce fait la charge sacrale dont l’empereur était dépositaire, singulièrement la dynastie dont il était l’héritier et le continuateur. Il avait conscience d’appartenir à une famille, fondée par Claude le Gothique (268 – 270), selon lui dépositaire d’une mission de jonction entre l’ici-bas et le divin.

Notons que Julien, le restaurateur du paganisme d’État, est mis sur le même plan que Constantin et que ses successeurs chrétien. En voulant créer une « Église païenne », en se mêlant de théologie, en édictant des règles de piété et de moralité, en excluant épicuriens, sceptiques et cyniques, il a consolidé la cohérence théologico-autoritaire de l’Empire. Il assumait de ce fait la charge sacrale dont l’empereur était dépositaire, singulièrement la dynastie dont il était l’héritier et le continuateur. Il avait conscience d’appartenir à une famille, fondée par Claude le Gothique (268 – 270), selon lui dépositaire d’une mission de jonction entre l’ici-bas et le divin.

Le déterminisme peut être également psychologique, en l’occurrence génétique: on ne choisit pas son corps et les caractères transmis par l’hérédité. Certains sont dits récessifs (vous les portez en vous, ils ne sont pas visibles directement, mais se manifesteront dans votre descendance), d’autres dominants (on les voit tout de suite en vous: couleur d’yeux, de cheveux, sexe, tendance au poids ou à la maigreur, à la grandeur ou à la petitesse, prédisposition à certaines maladies – cancers, hypertension, hypercholestérolémie, etc., ou héritage de maladies -diabète, hémophilie, etc.). Qui reprocherait à un adulte de développer un cancer de forte nature héréditaire? De la même manière nous échoient un tempérament sexuel ou une santé spécifique.

Le déterminisme peut être également psychologique, en l’occurrence génétique: on ne choisit pas son corps et les caractères transmis par l’hérédité. Certains sont dits récessifs (vous les portez en vous, ils ne sont pas visibles directement, mais se manifesteront dans votre descendance), d’autres dominants (on les voit tout de suite en vous: couleur d’yeux, de cheveux, sexe, tendance au poids ou à la maigreur, à la grandeur ou à la petitesse, prédisposition à certaines maladies – cancers, hypertension, hypercholestérolémie, etc., ou héritage de maladies -diabète, hémophilie, etc.). Qui reprocherait à un adulte de développer un cancer de forte nature héréditaire? De la même manière nous échoient un tempérament sexuel ou une santé spécifique.

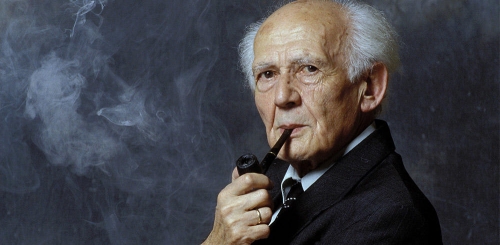

On va relire le sociologue israélo-britannique Zygmunt Bauman, auteur de remarquables essais sur notre postmoderne et zombi mondialisation. Il a bien compris que la clé c’est la peur et son exploitation (on est en 2002) :

On va relire le sociologue israélo-britannique Zygmunt Bauman, auteur de remarquables essais sur notre postmoderne et zombi mondialisation. Il a bien compris que la clé c’est la peur et son exploitation (on est en 2002) : Bauman ici explique pourquoi on croule sous d’horribles et coûteuses voitures informelles. Cela correspond à la paranoïa du « « capitalisme de catastrophe » (Ramonet) :

Bauman ici explique pourquoi on croule sous d’horribles et coûteuses voitures informelles. Cela correspond à la paranoïa du « « capitalisme de catastrophe » (Ramonet) : Il est important de rappeler cela, qu’il s’agisse de Sarkozy-Macron-Hollande, de Bush, May, Clinton-Obama, Merkel et du reste ; l’Etat fasciste-sécuritaire accompagne la dégradation-extinction de l’Etat de droit et de l’État social. L’État renonce à la carotte et a recours à la trique du CRS et au contrôle par des services plus ou moins secrets :

Il est important de rappeler cela, qu’il s’agisse de Sarkozy-Macron-Hollande, de Bush, May, Clinton-Obama, Merkel et du reste ; l’Etat fasciste-sécuritaire accompagne la dégradation-extinction de l’Etat de droit et de l’État social. L’État renonce à la carotte et a recours à la trique du CRS et au contrôle par des services plus ou moins secrets : On a tous vu la nullité brouillonne des forces du désordre à Strasbourg. Mais ce chaos fait partie de la mise en scène, et Bauman vous l’explique :

On a tous vu la nullité brouillonne des forces du désordre à Strasbourg. Mais ce chaos fait partie de la mise en scène, et Bauman vous l’explique :

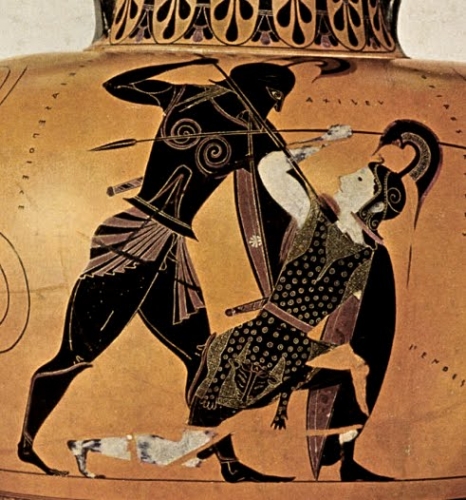

European culture formally began with the books of Homer. These European cultural stories were popularized in Europe approximately 3,000 years ago and then written down by the poet Homer about 2,700 years ago. One of the major themes in Homer is the concept of Xenia. Xenia defines the behavior expected from local European residents toward travelers, strangers, and even immigrants. Xenia also defines the behavior that is expected in return from these guests, these strangers in a strange land. The concepts presented in the Iliad and the Odyssey are considered the foundation of the European cultural tradition termed the code of hospitality or the code of courtesy.

European culture formally began with the books of Homer. These European cultural stories were popularized in Europe approximately 3,000 years ago and then written down by the poet Homer about 2,700 years ago. One of the major themes in Homer is the concept of Xenia. Xenia defines the behavior expected from local European residents toward travelers, strangers, and even immigrants. Xenia also defines the behavior that is expected in return from these guests, these strangers in a strange land. The concepts presented in the Iliad and the Odyssey are considered the foundation of the European cultural tradition termed the code of hospitality or the code of courtesy.

Certes, ces outils de partage de véhicules, ou de chambres, rendent à coup sûr bien des services, alliant l’intérêt financier à des contacts humains qui peuvent être sympathiques, bien que la plupart du temps, très superficiels. Mais nos auteurs oublient une caractéristique de tous ces réseaux. C’est la notation, ce sont les « étoiles » à affecter à chaque « partenaire », c’est la mise en ligne des « avis », ce sont les commentaires qui sont publics, etc. C’est la tyrannie de la transparence. Et alors que les auteurs critiquent les concours, ils font l’éloge des réseaux, qui impliquent un système de notation beaucoup plus inquisitorial que n’importe quel concours, une dictature de la transparence, intrusive, et plus injuste que n’importe quel concours. Les réseaux sociaux ? C’est le grand panoptique. Faire leur apologie ? C’est tuer l’intimité, la pudeur, le quant à soi. Au profit des ego, du tank à soi.

Certes, ces outils de partage de véhicules, ou de chambres, rendent à coup sûr bien des services, alliant l’intérêt financier à des contacts humains qui peuvent être sympathiques, bien que la plupart du temps, très superficiels. Mais nos auteurs oublient une caractéristique de tous ces réseaux. C’est la notation, ce sont les « étoiles » à affecter à chaque « partenaire », c’est la mise en ligne des « avis », ce sont les commentaires qui sont publics, etc. C’est la tyrannie de la transparence. Et alors que les auteurs critiquent les concours, ils font l’éloge des réseaux, qui impliquent un système de notation beaucoup plus inquisitorial que n’importe quel concours, une dictature de la transparence, intrusive, et plus injuste que n’importe quel concours. Les réseaux sociaux ? C’est le grand panoptique. Faire leur apologie ? C’est tuer l’intimité, la pudeur, le quant à soi. Au profit des ego, du tank à soi.  Mais alors, qu’est-ce qui fait sens pour nous tous ? La réponse est que nous sommes devant un pur néant. Celui-ci ne peut que légitimer la déconstruction de tout Etat. Si rien ne nous rassemble en peuple, pourquoi un garant de ce rassemblement ? Mais si l’Etat n’est pas à lui tout seul le garant du bien commun, ni même l’unique élément d’un ordre public, il en est l’un des piliers. L’Etat ne doit pas être tout, mais il couronne le tout. Déconstruire tout Etat, c’est sortir de l’histoire, en d’autres termes, c’est devenir colonisés, c’est devenir sujet de l’histoire des autres. « L’anarchie, c’est l’ordre sans l’Etat », disaient Elisée Reclus et P-J Proudhon. Mais quand règne, dans de nombreux quartiers, une forme d’ensauvagement, ce n’est le moment de supprimer l’Etat, dont l’une des fonctions essentielles est la sécurité du peuple, aussi bien la sécurité intérieure que la sécurité extérieure (on peut certes imaginer des « tribus » de sociétés privées de sécurité, et de gardes du corps, et d’ailleurs, elles existent déjà, mais la sécurité est alors proportionnelle aux moyens financiers).

Mais alors, qu’est-ce qui fait sens pour nous tous ? La réponse est que nous sommes devant un pur néant. Celui-ci ne peut que légitimer la déconstruction de tout Etat. Si rien ne nous rassemble en peuple, pourquoi un garant de ce rassemblement ? Mais si l’Etat n’est pas à lui tout seul le garant du bien commun, ni même l’unique élément d’un ordre public, il en est l’un des piliers. L’Etat ne doit pas être tout, mais il couronne le tout. Déconstruire tout Etat, c’est sortir de l’histoire, en d’autres termes, c’est devenir colonisés, c’est devenir sujet de l’histoire des autres. « L’anarchie, c’est l’ordre sans l’Etat », disaient Elisée Reclus et P-J Proudhon. Mais quand règne, dans de nombreux quartiers, une forme d’ensauvagement, ce n’est le moment de supprimer l’Etat, dont l’une des fonctions essentielles est la sécurité du peuple, aussi bien la sécurité intérieure que la sécurité extérieure (on peut certes imaginer des « tribus » de sociétés privées de sécurité, et de gardes du corps, et d’ailleurs, elles existent déjà, mais la sécurité est alors proportionnelle aux moyens financiers).

Il existe plusieurs types d’exercices spirituels liés à l’étude de la nature, et donc à la physique. Pour Pierre Hadot, le premier exercice stoïcien qui permet de mettre en pratique la physique stoïcienne, c’est l’exercice qui consiste à « se reconnaître comme partie du Tout, à s’élever à la conscience cosmique, à s’immerger dans la totalité du cosmos » (P. Hadot, 1995, p. 211). C’est

Il existe plusieurs types d’exercices spirituels liés à l’étude de la nature, et donc à la physique. Pour Pierre Hadot, le premier exercice stoïcien qui permet de mettre en pratique la physique stoïcienne, c’est l’exercice qui consiste à « se reconnaître comme partie du Tout, à s’élever à la conscience cosmique, à s’immerger dans la totalité du cosmos » (P. Hadot, 1995, p. 211). C’est

Les guerres se succédèrent, à peine la guerre (161–166) contre les Parthes (Perses) est-elle terminée, que les barbares menacent directement le nord de l’Italie. Il faut plus de cinq années (169–175) à l’empereur pour venir à bout de cette menace. C’est alors qu’une rumeur de la mort de Marc Aurèle conduit Avidius Cassius, gouverneur d’une large partie de l’Orient, à se proclamer empereur. Mais en juillet 175, celui-ci est assassiné et sa tête envoyée à Marc Aurèle. Ce dernier regretta sa mort, sûr de son repentir. Enfin, dès 177, Marc Aurèle doit repartir guerroyer sur la frontière danubienne où il y mourra (180).

Les guerres se succédèrent, à peine la guerre (161–166) contre les Parthes (Perses) est-elle terminée, que les barbares menacent directement le nord de l’Italie. Il faut plus de cinq années (169–175) à l’empereur pour venir à bout de cette menace. C’est alors qu’une rumeur de la mort de Marc Aurèle conduit Avidius Cassius, gouverneur d’une large partie de l’Orient, à se proclamer empereur. Mais en juillet 175, celui-ci est assassiné et sa tête envoyée à Marc Aurèle. Ce dernier regretta sa mort, sûr de son repentir. Enfin, dès 177, Marc Aurèle doit repartir guerroyer sur la frontière danubienne où il y mourra (180).

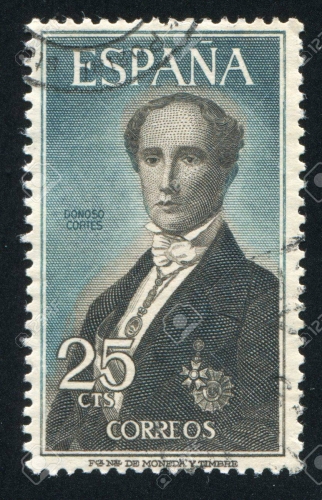

La deuxième partie de l'ouvrage est consacrée aux textes proprement dits de Carl Schmitt mais il faut attendre la page 157 de l'ouvrage, dans une étude intitulée Catholicisme romain et forme politique datant de 1923, pour que le nom de Cortés apparaisse, d'ailleurs de façon tout à fait anecdotique. Cette étude, plus ample que la première, intitulée Visibilité de l’Église et qui ne nous intéresse que par sa mention d'une paradoxale quoique rigoureuse légalité du Diable (4), mentionne donc le nom de l'essayiste espagnol et, ô surprise, celui d'Ernest Hello (cf. p. 180) mais, plus qu'une approche de Cortés, elle s'intéresse à l'absence de toute forme de représentation symbolique dans le monde technico-économique contemporain, à la différence de ce qui se produisait dans la société occidentale du Moyen Âge. Alors, la représentation, ce que nous pourrions sans trop de mal je crois appeler la visibilité au sens que Schmitt donne à ce mot, conférait «à la personne du représentant une dignité propre, car le représentant d'une valeur élevée ne [pouvait] être dénué de valeur» tandis que, désormais, «on ne peut pas représenter devant des automates ou des machines, aussi peu qu'eux-mêmes ne peuvent représenter ou être représentés» car, si l’État «est devenu Léviathan, c'est qu'il a disparu du monde du représentatif». Carl Schmitt fait ainsi remarquer que «l'absence d'image et de représentation de l'entreprise moderne va chercher ses symboles dans une autre époque, car la machine est sans tradition, et elle est si peu capable d'images que même la République russe des soviets n'a pas trouvé d'autre symbole», pour l'illustration de ce que nous pourrions considérer comme étant ses armoiries, «que la faucille et le marteau» (p. 170). Suit une très belle analyse de la rhétorique de Bossuet, qualifiée de «discours représentatif» qui «ne passe pas son temps à discuter et à raisonner» et qui est plus que de la musique : «elle est une dignité humaine rendue visible par la rationalité du langage qui se forme», ce qui suppose «une hiérarchie, car la résonance spirituelle de la grande rhétorique procède de la foi en la représentation que revendique l'orateur» (p. 172), autrement dit un monde supérieur garant de celui où faire triompher un discours qui s'ente lui-même sur la Parole. Le décisionnisme, vu de cette manière, pourrait n'être qu'un pis-aller, une tentative, sans doute désespérée, de fonder ex abrupto une légitimité en prenant de vitesse l'ennemi qui, lui, n'aura pas su ou voulu tirer les conséquences de la mort de Dieu dans l'hic et nunc d'un monde quadrillé et soumis par la Machine, fruit tavelé d'une Raison devenue folle et tournant à vide. Il y a donc quelque chose de prométhéen dans la décision radicale de celui qui décide d'imposer sa vision du monde, dictateur ou empereur-Dieu régnant sur le désert qu'est la réalité profonde du monde moderne.