Presseschau

September 2018

AUßENPOLITISCHES

Patriotische Globalisierungskritik

https://recherche-dresden.de/patriotische-globalisierungs...

Welt ohne Geld - Wie die Abschaffung von Banknoten vorangetrieben wird

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJCsxZSWtWE&t=2280s

Bayer-Aktie

Wie ein Urteil zehn Milliarden Euro Börsenwert auslöscht

Weil die Konzerntochter Monsanto 290 Millionen Dollar Schmerzensgeld an einen Hausmeister zahlen soll, stürzt der Kurs der Bayer-Aktie ab. Wie kann das sein?

http://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/unternehmen/bayer-und-mo...

(Salvini schmeckt ihnen nicht…)

Rechtspopulist

Italiens Innenminister Salvini empört mit Mussolini-Anspielung

https://www.welt.de/politik/article180189144/Rechtspopuli...

Spaniens Außenminister kritisiert Salvini und lobt Merkel

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/spaniens-au...

Affäre Benalla

Macron wird abgeschminkt

von Jürgen Liminski

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/macron-wird...

Schweden: Neue Partei will 500.000 Einwanderer ausweisen und Asylsystem komplett abschaffen

https://www.unzensuriert.at/content/0027161-Schweden-Neue...

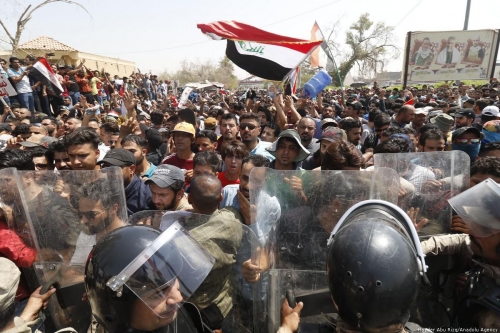

Brandstiftung

Schweden – Jugendbanden zerstören rund 100 Autos in mehreren Städten

https://www.handelsblatt.com/video/panorama/brandstiftung...

Vermummte setzen in Schweden Dutzende Autos in Brand

https://www.derwesten.de/panorama/vermummte-setzen-in-sch...

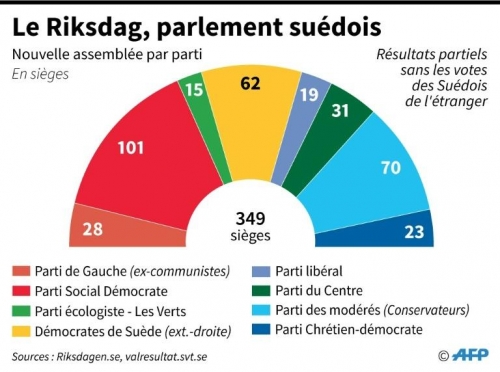

Parlamentswahlen

Schwedens Klimawandel durch die Rechtspopulisten

https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/schweden-schwedens-kl...

"Sehen aus wie Briefkästen"

Nach Shitstorm und Parteizoff: Rowan Atkinson verteidigt Boris Johnsons Burka-Witz

https://www.stern.de/lifestyle/leute/rowan-atkinson-verte...

Terror in Westminster

Attentäter von London wohnte in Islamistenviertel

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/attentaeter...

Ermittler: Messerattacke in Amsterdam war Terroranschlag

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/politik/ermittler-messeratta...

Schweiz

Lausanne

Gleichberechtigung contra Religionsfreiheit

Handschlag verweigert: Schweizer Stadt lehnt Einbürgerung ab

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/handschlag-...

Streit ums Denkmal: Wie Russlands Ex-Staatsführer die Gemüter erhitzen

https://de.rbth.com/kultur/geschichte/2017/08/09/streit-u...

Konflikt zwischen Nato-Partnern USA und Türkei

Nach sonderbarem Erdogan-Aufruf an Türken: Lira im Sturzflug - Trump in Höchstlaune

https://www.merkur.de/politik/lira-im-sturzflug-erdogan-w...

Die Folgen der Strafzölle

Türkische Lira fällt und fällt – und zieht den Euro mit sich

https://www.t-online.de/nachrichten/ausland/international...

USA überholen unter Trump Italien bei Verschuldung

In den kommenden Jahren soll fast überall eine Trendwende bei den Schulden einsetzen. Nur die USA scheren aus

https://www.derstandard.de/story/2000078276614/usa-ueberh...

Walk of Fame

Stadtrat in Hollywood gegen Trump-Stern

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/stadtrat-in...

Proteste gegen US-Präsident

Secret Service untersucht Morddrohungen der Antifa gegen Trump

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/secret-serv...

("mehrheitlich junge Weiße"…)

North Carolina

Demonstranten feiern Sturz von Südstaaten-Denkmal

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/demonstrant...

(Krawalle an US-Westküste)

Ultrarechte Eskalationsstrategie

https://www.heise.de/tp/features/Ultrarechte-Eskalationss...

Space Force: USA wollen bis 2020 Weltraumstreitkraft gründen

Die US-Regierung hat das Ziel ausgegeben, die Dominanz im Weltall zu erlangen. Dies sei wichtig, um die Interessen des Landes zu schützen, sagt Vizepräsident Mike Pence.

https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2018-08/space-force-u...

USA schieben früheren KZ-Aufseher nach Deutschland ab

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/panorama/usa-schieben-fruehe...

„Allianz für den Multilateralismus“

Maas setzt auf Kanada als Partner für Gegengewicht zu den USA

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/maas-setzt-...

"Niemand hört uns": Jesidin trifft IS-Peiniger in Deutschland wieder

https://www.svz.de/deutschland-welt/panorama/Jesidin-trif...

Kommunistische Regierung in Nepal

Neustart mit Hammer und Sichel

Seit Februar regiert in Nepal eine demokratisch gewählte Allianz aus zwei kommunistischen Parteien. Sie muss sich großen Herausforderungen stellen.

http://www.taz.de/!5526610/

Bolivien

Morales bezieht pompösen Präsidententurm

http://www.lessentiel.lu/de/news/story/Morales-bezieht-po...

http://www.dtoday.de/startseite/politik_artikel,-Bolivien...

Bankpleiten befürchtet: Land-Enteignungen könnten Südafrika teuer zu stehen kommen

http://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/mehr-wirtschaft/lan...

May unterstützt Landreform in Südafrika

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/may-unterst...

INNENPOLITISCHES / GESELLSCHAFT / VERGANGENHEITSPOLITIK

Dysfunktionaler Staat

Deutschland ist abgebrannt

von Nicolaus Fest

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/deutschla...

Fast eine Billion Euro

FDP-Chef Lindner: „Der Sozialstaat gerät außer Kontrolle“

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/fdp-che...

Zinsderivate

Hessen verspekuliert Hunderte Millionen Euro an Steuergeldern

https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article181299256/Zinsderiv...

Genossen im Umfragetief

Mitgliederzahl der SPD schrumpft: So reagiert Nahles

https://www.merkur.de/politik/mitgliederzahl-spd-schrumpf...

Nahles-Vorschlag zur Türkei

„Mit Wirtschaftshilfen stabilisiert man nur das System Erdogan“

https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article181235588/...

Merkel besucht den Senegal

Das Thema Migration ist schon da

https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Das-Thema-Migration-ist-schon...

ARD-Sommerinterview

Merkel ist übergeschnappt

Von Rainer Zitelmann

https://www.wallstreet-online.de/nachricht/10821041-ard-s...

(Ihr scheinbar größtes Problem…)

Bundesfamilienministerin: "Mit Hakenkreuzen spielt man nicht"

Verfassungswidrige Symbole dürfen seit kurzem in Videospielen gezeigt werden. Franziska Giffey kritisiert dies nun scharf. Auch aus der Union kommt Kritik.

http://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/diginomics/franzisk...

Söder schreibt die SPD als politischen Gegner ab

https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article181280198/...

Koalitionen mit Linkspartei

Günther setzt Merkels Links-Kurs der CDU fort

von Jörg Kürschner

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/guenther-...

Kramp-Karrenbauer

Die CDU will schwuler werden – aber jetzt noch nicht

https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/plus181303896/Kra...

Moderne Großstadtpartei CDU

Den anderen linken Parteien einen Schritt voraus

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/den-ander...

Bundeswehr-Generalinspekteur gegen Wiedereinführung der Wehrpflicht

https://www.pfalz-express.de/bundeswehr-generalinspekteur...

Liederprobleme bei der Bundeswehr

„Jawohl, Frau Kapitän!“

von Felix Krautkrämer

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/jawohl-...

Wegen Tweet zu Chemnitz

Pazderski fordert Disziplinarverfahren gegen Chebli

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/pazders...

(Zu Heiko Maas…)

Wegen Auschwitz in die Politik. Oder umgekehrt?

Von Henryk M. Broder

https://www.achgut.com/artikel/wegen_auschwitz_in_die_pol...

(BRD-Wahnsinn…)

Besuch in Buchenwald

„Leidet Ramelow an Nazitourette?“

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/leidet-...

Antisemitismus

Land setzt mit Ernennung von Felix Semmelroth Zeichen

Zum ersten Mal in der Geschichte des Bundeslandes hat Hessen einen Antisemitismusbeauftragten. Für sein Amt hat sich Felix Semmelroth zwar eine Menge vorgenommen. Ob er dabei viel bewirken kann, hängt aber nicht nur von ihm allein ab.

http://www.fnp.de/rhein-main/Land-setzt-mit-Ernennung-von...

(Besserwisser interpretieren ungeklärte Geschichte)

Beutekunst

Historisches Museum gibt neun Exponate zurück

Das Historische Museum Frankfurt am Main hat neun Exponate mutmaßlichen NS-Raubguts in seiner Sammlung entdeckt und an das Jüdische Museum übergeben. Die Forschung nach der Herkunft und Verwendung erwies sich als sehr schwierig.

http://www.fnp.de/lokales/frankfurt/Historisches-Museum-g...

Deutsche Kolonialzeit

Bundesregierung gibt Herero- und Nama-Gebeine zurück

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/2018/bundesregierung-gibt...

(Noch?...)

Schulfahrten zu NS-Gedenkstätten bleiben freiwillig

http://www.fnp.de/rhein-main/Schulfahrten-zu-NS-Gedenksta...

Opfer der DDR

Die große Gleichgültigkeit

von Jörg Kürschner

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-gross...

Nach Eklat in KZ-Gedenkstätte

Auschwitz-Komitee schockiert wegen AfD-Besuchergruppe

Eine AfD-Gruppe hat in der KZ-Gedenkstätte Sachsenhausen an Gaskammern gezweifelt. Die Staatsanwaltschaft ermittelt wegen des Verdachts auf Volksverhetzung.

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/nach-eklat-in-kz-gede...

LINKE / KAMPF GEGEN RECHTS / ANTIFASCHISMUS / RECHTE

Repression – im Gespräch mit Caroline Sommerfeld

https://sezession.de/59361/repression-im-gespraech-mit-ca...

(Linke Einwanderungslobby – Jakob Augstein und Konsorten)

Ein amerikanischer Alptraum (1) – Grundlagen

https://sezession.de/59186/ein-amerikanischer-alptraum-1-...

(Linke Einwanderungslobby)

#metwo-Kampagne

Nimm zwei

von Fabian Schmidt-Ahmad

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/nimm-zwei...

(Zwar von 2015, aber aktueller denn je. Eine finale Abrechnung mit Heribert Prantl, über dessen Geisteszustand nicht mehr spekuliert zu werden braucht.)

"Festung Europa"? Flüchtlinge als Bauern in Mecklenburg ansiedeln

https://www.welt.de/debatte/kommentare/article141708971/F...

(Ein weiterer Fall von Wirklichkeitsverdrehung)

Chemnitz

Angstforscher: Fremdenfeindlichkeit „genetisch veranlagt“

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/2018/angstforscher-fremde...

Wagenknecht, die »soziale Frage« und wir (3)

https://sezession.de/59103/wagenknecht-die-soziale-frage-...

„Aufstehen“

36.000 Anmeldungen für Wagenknechts Sammlungsbewegung

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/36-000-...

Tweet zum 13. August

Holm: Linksjugend solid verharmlost Mauertote

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/holm-li...

Linksfraktion im Bundestag

Wer ist da Koch, und wer ist Kellner?

von Felix Krautkrämer

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/wer-ist...

(SPD möchte noch mehr schrumpfen…)

Wegen neuem Buch

Führende SPD-Politiker wollen Thilo Sarrazin erneut loswerden

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/fuehren...

Thilo Sarrazin

Im Fegefeuer der Rassistenjäger

von Lukas Mihr

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/im-fegefe...

Franziska Schreiber, eine Verleumdung und das Gericht

https://sezession.de/59194/franziska-schreiber-eine-verle...

Thüringens Ministerpräsident

Ramelow macht AfD für wachsenden Antisemitismus mitverantwortlich

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/ramelow...

(…wer´s glaubt, wird selig…)

Durchsichtige Stimmungsmache

Parlamentsfraktionen zerpflücken islamfeindliche Anträge der AfD

https://www.op-online.de/offenbach/durchsichtige-stimmung...

Beobachtung durch Verfassungsschutz gefordert

Oppermann wirft AfD Zusammenarbeit mit Neonazis vor

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/opperma...

Verfassungsschutz

Niedersachsen und Bremen lassen Junge Alternative beobachten

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/nieders...

(SPD-Forderungen willfährig journalistisch sekundiert…Zitat: "Darüber hinaus wird es Zeit, geschichtsklitternde Feinde von Demokratie und Zivilisation zu ächten." Wenn das mal kein hetzerischer Aufruf ist?...)

Wenn der Eklat zum Programm wird

Kommentar: AfD gehört beobachtet

https://www.op-online.de/politik/kommentar-gehoert-beobac...

(Linksradikale wollen anonym bleiben)

Namen von Studentenausschuß

Nach AfD-Anfrage: Humboldt-Uni verklagt Studentenvertretung

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/nach-af...

("Antifa"-Anprangerungsartikel gegen AfD-Politiker)

Peter Felser im völkischen Lebensbund

http://rechte-jugendbuende.de/?p=2345

(Kleine Tricksereien)

Vorstoß von Bürgermeister

München sperrt AfD aus dem Rathaus

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/muenche...

Der Paritätische Wohlfahrtsverband auf linken Abwegen

https://irisnieland.wordpress.com/2018/08/31/der-paritaet...

„Nicht im Einklang mit unseren Werten“

SV Darmstadt 98 will keine AfD-Anhänger unter seinen Fans

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/sv-darm...

„Der Verein tut sich keinen Gefallen“

AfD wirft SV Darmstadt 98 Politisierung und Spaltung der Fans vor

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/afd-wir...

Kampagne gegen AfD

FSV Mainz 05 protestiert gegen Gauland-Auftritt

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/fsv-mai...

(Hier geht die Saat des linken Hasses auf…)

Vorpommern

Linksextremist attackiert AfD-Mitarbeiter in Wahlkreisbüro

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/linksex...

(Angriff gegen den saarländischen AfD-Landtagsabgeordnete Lutz Hecker)

Brutaler Anschlag auf AfD-Politiker: „Ursache ist ist die tägliche Stigmatisierung der AfD“

https://www.journalistenwatch.com/2018/08/13/der-naehrbod...

Dresden

Antifa, Bundeswehr-Distanzierung und trotzdem erfolgreich

https://recherche-dresden.de/antifa-bundeswehr-distanzier...

(Nach linken Feindeslisten wird in den Medien nicht gefragt…)

Rechtsextreme Szene

25.000 Namen auf "Feindeslisten"

https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/feindeslisten-neonazis-1...

Verhärtung

Von Johannes Poensgen

https://sezession.de/59347/verhaertung

(Die nächste Alt-Antifa-Medienaktion)

Neu-Isenburg

Aktionen gegen Ressentiments

Neue Initiative gegen Rechts: „Solidarität statt Hetze“

https://www.op-online.de/region/neu-isenburg/neue-initiat...

EINWANDERUNG / MULTIKULTURELLE GESELLSCHAFT

Die Asymmetrie des Rassenhasses

https://sezession.de/59322/die-asymmetrie-des-rassenhasses

Statistik

Gibt es wirklich mehr AfD-Wähler, wo weniger Ausländer sind?

von Lukas Mihr

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/gibt-es...

Migration

Wenn die Einheimischen auf einmal in der Minderheit sind

In einigen großen Städten stellen Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund schon die Mehrheit. Das weckt Ängste. Doch die sind oft unbegründet. Eine Kolumne.

Von Barbara John

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/migration-wenn-die-ei...

Bundespräsident

Steinmeier dankt Einwanderern für Deutschlands Wohlstand

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/steinme...

(Großverdiener machen PR…)

"Menschlichkeit ist Pflicht": Herbert Grönemeyer und andere Prominente setzen sich für Seenot-Retter ein

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/politik/menschlichkeit-pflic...

(Alt-68er Leggewie verbreitet mal wieder seine Thesen zu "Rassismus"…)

#MeTwo : Rassismus – Alltag in Deutschland?

https://www.shz.de/nachrichten/meldungen/rassismus-alltag...

(#MeTwo-Kampagne, die natürlich keinen "Rassismus" gegen Deutsche kennt)

Niedersachsens Ministerpräsident

Weil: „Deutschland hat ein Rassismus-Problem“

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/weil-de...

Ist Deutschland zu weiß? (1)

https://sezession.de/59258/ist-deutschland-zu-weiss-1

Ist Deutschland zu weiß? (2)

https://sezession.de/59290/ist-deutschland-zu-weiss-2

Weiße Männer – Allzweckwaffe der Diskriminierungsindustrie (1)

https://sezession.de/59326/weisse-maenner-allzweckwaffe-d...

Weiße Männer – Allzweckwaffe der Diskriminierungsindustrie (2)

https://sezession.de/59339/weisse-maenner-allzweckwaffe-d...

Studie zu Zuwanderern aus der Türkei

Verbundenheit zu Deutschland nimmt ab

https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/studie-zu-zuwanderern-aus-...

Fördergelder in Millionenhöhe

Flüchtlingshilfe lohnt sich

von Felix Krautkrämer

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/fluecht...

Katrin Göring-Eckardt

Grüne erklären Asyl zum Menschenrecht

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/gruene-...

„Jugend Rettet“

Evangelische Kirche: Flüchtlingshelfer im Mittelmeer sind Helden

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/gesellschaft/2018/evangel...

Flüchtlingsschiff

„Aquarius“ darf in Malta anlegen: Auch Deutschland nimmt Einwanderer auf

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/aquarius-da...

Flüchtlingsboot „Aquarius“

Shuttle-Kapitän Seehofer

von Felix Krautkrämer

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/shuttle-k...

Hilfe von befreundeten Staaten

Syrien: Komitee soll Rückkehr von Flüchtlingen organisieren

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/syrien-komi...

Abgelehnte Asylbewerber

Bleibeperspektive: SPD und FDP stellen sich hinter Günther

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/bleibep...

Einwanderung

Die Abfahrt längst verpaßt

von Michael Paulwitz

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-abfah...

Abschiebungen ausländischer Fachkräfte

Wirtschaftsinstitut: „Jeder verlorene Mitarbeiter tut weh“

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/wirtsch...

Online-Debatte

Bedford-Strohm entsetzt über Zurückweisung von Flüchtlingen

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/bedford...

"Würdevolle Migration"

Grüne Jugend fordert Staatsbürgerschaft für Klima-Flüchtlinge

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/gruene-...

Steigene Zahlen

AfD fordert härteres Vorgehen gegen Kirchenasyl

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/afd-for...

Gesundheitsamt: Alarmierende Lücken

Immer weniger Schulanfänger können Deutsch

https://www.op-online.de/offenbach/immer-weniger-koennen-...

An einem Tag

Spanische Küstenwache bringt 460 Migranten nach Europa

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/spanische-k...

Abkommen von 1992

Spanien schiebt Ceuta-Eindringlinge postwendend ab

von Marco Pino

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/spanien-sch...

Migrationsvereinbarung

Lambsdorff nennt Spanienabkommen einen „Witz“

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/lambsdorff-...

Wiedereinreise trotz Sperre

Knapp 700.000 abgelehnte Asylbewerber in Deutschland

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/knapp-7...

Rekordzahlen

Starker Anstieg ausländischer Kindergeld-Empfänger

https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article180843060/...

Umstrittene Zahlung von Kindergeld an EU-Ausländer: Das Beispiel Duisburg

https://www.tagesschau.de/multimedia/video/video-435303.h...

Überweisungen ins Ausland

EU-Kommission lehnt Kindergeld-Reform ab

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/eu-komm...

Kindergeldzahlungen an Ausländer

Sinti und Roma: SPD soll sich von Duisburger Bürgermeister distanzieren

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/sinti-u...

Ruhrgebiet

Der Kampf einer Essener Mutter um einen Kita-Platz

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/der-kam...

Bundesagentur für Arbeit

Integration von Flüchtlingen im Arbeitsmarkt läuft gut

https://www.welt.de/politik/article181247264/Bundesagentu...

Baden-Württemberg

Schrotthaufen vor Asylunterkunft: „Das wird eine Radwerkstatt“

von Martina Meckelein

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/schrott...

Baden-Württemberg

Die Geschichte einer dubiosen Radwerkstatt für Flüchtlinge

von Martina Meckelein

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/die-ges...

Racial Profiling

Urteil fernab der Realität

von Boris T. Kaiser

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/urteil-fe...

Verlängerte Rückführungsfrist

Bedford-Strohm kritisiert verschärfte Regeln fürs Kirchenasyl

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/bedford...

„Flüchtlingskirche“

Unbekannte attackieren Kirche unter „Allahu Akbar“-Rufen

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/unbekan...

(Opfer-Story…)

Hockenheim

Burkini-Streit: Schwimmbadleitung widerspricht Moslemin

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/burkini...

Zunahme um fast 60 Prozent

Zahl der Moscheen in Baden-Württemberg wächst stark

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/zahl-de...

DITIB plant spektakuläre Moschee in Norderstedt

https://dieunbestechlichen.com/2018/06/ditib-plant-spekta...

Kampagne für den Gottesstaat

Verfassungsfeindliche Gruppe mobilisiert in Offenbach und Hanau gegen „Kopftuchverbot“

https://www.op-online.de/offenbach/kampagne-gottesstaat-1...

Schwedische „Aktivistin“ verhinderte Abschiebung – jetzt kommt heraus, der Afghane ist ein verurteilter Frauenschläger

https://www.journalistenwatch.com/2018/08/11/schwedische-...

Haftbefehle

Chemnitz: Syrer und Iraker unter Tatverdacht

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/chemnit...

Tatverdächtiger Iraker

Chemnitzer Messerstecher war vorbestraft

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/chemnit...

Nach tödlicher Messerattacke

Chemnitz : Verletzte nach Zusammenstößen bei Trauerkundgebung

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/verletz...

(Der Ausgangspunkt der „Hetzjagd“-Medienlüge von Chemnitz)

Wie man den Ausnahmezustand herbeischreibt

Autor Vera Lengsfeld

https://vera-lengsfeld.de/2018/08/30/wie-man-den-ausnahme...

#CHEMNITZ - Ein Insiderbericht - Frank Stoner im Gespräch mit Frank Höfer

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDU1vo0Tz6A&app=desktop

«Ich bin Oma, kein Rassist»: Chemnitz fühlt sich zu unrecht als rechtsradikal abgestempelt – eine Reportage

https://www.nzz.ch/international/das-schlimmste-was-passi...

„Übertriebene Erzählungen“

Chemnitzer Lokalzeitung widerspricht „Hetzjagd“-Berichten

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/chemnit...

Fall Chemnitz

Haftbefehl veröffentlicht und suspendiert: Beamter erklärt Beweggründe

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/haftbef...

(dazu…)

Sonntagsheld – Ein Diamant im Getriebe

Euer Widerstand soll funkeln…

https://sezession.de/59359/sonntagsheld-74-ein-diamant-im...

Tödliche Messerattacke: Bundesregierung verurteilt „Hetzjagden“

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/toedlic...

Kanzlerin und Minister äußern sich

Chemnitz: Merkel beklagt „Haß auf der Straße“

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/chemnit...

Generalstaatsanwalt überführt Merkel der Lüge: „Es hat in Chemnitz keine Hetzjagd gegeben“

https://www.journalistenwatch.com/2018/09/02/generalstaat...

Trotz gegenteiliger Erkenntnisse

Chemnitz: Bundesregierung verteidigt Hetzjagd-Vorwurf

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/chemnit...

(Hetze-verdächtiges Zitat: „Hier wird überdeutlich, dass sich Kritiker der Europa- und Flüchtlingspolitik zu Gehilfen der Braunen machen lassen.“)

Stadt in der Defensive: Kommentar zur Lage in Chemnitz

https://www.hna.de/politik/stadt-in-defensive-kommentar-z...

(Campino und Co. spannen sich mal wieder vor den Karren der etablierten Eliten)

„Wir sind mehr“ in Chemnitz: Das müssen Sie über das Konzert gegen Rechts wissen

Die Toten Hosen, Marteria, Casper und K.I.Z. rocken unter dem Motto #wirsindmehr in Chemnitz, um ein Zeichen gegen Rechtsextremismus zu setzen. Auch die Band Madsen bezieht mit einem Konzert am Samstag Stellung.

http://www.haz.de/Nachrichten/Kultur/Uebersicht/Wir-sind-...

Chemnitz: Tanz auf dem Grab – Staatskünstler stützen Merkelpolitik

http://unser-mitteleuropa.com/2018/08/31/chemnitz-tanz-au...

Blablacar und Flixbus-Gründer

Gratis-Fahrtkarten zu „Anti-Rechts“-Konzert in Chemnitz

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/gratis-...

(Bundespräsident fördert Linksradikale)

Feine Sahne Fischfilet und der Bundespräsident

Pazderski kritisiert Steinmeiers Werbung für linksextreme Band

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/pazders...

Linksradikale Punkband in Chemnitz

„Feine Sahne Fischfilet“: Polizeigewerkschaft kritisiert Bundespäsidenten

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/feine-s...

CDU-Spitze rügt Bundespräsident Frank-Walter Steinmeier wegen Unterstützung von Feine Sahne Fischfilet

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/politik/cdu-spitze-ruegt-bun...

Konzert in Chemnitz - Mehr als 60.000 setzen Zeichen gegen Rechts

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/politik/konzert-chemnitz-500...

Demonstrationen in Chemnitz

Die Haltungszyniker löschen Feuer mit Benzin

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-haltu...

Chemnitz

Die angestaute Wut auf Merkel explodiert

von Dieter Stein

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-anges...

Chemnitz und die Medien

Die Indoktrination scheitert am ostdeutschen Widerstandswillen

von Karlheinz Weißmann

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-indok...

Chemnitz: Was gesagt werden muss

https://einprozent.de/blog/aktiv/chemnitz-was-gesagt-werd...

Chemnitz – zehn Punkte für die nächsten Tage

Von Götz Kubitschek

https://sezession.de/59342/chemnitz-zehn-punkte-fuer-die-...

Aktualisierung

Trauermarsch für Daniel H. wird nach Blockaden aufgelöst

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/trauerm...

(dazu…)

Nicht nur der Rechtsstaat hat in Chemnitz kapituliert

https://sezession.de/59356/nicht-nur-der-rechtsstaat-hat-...

(dazu…)

Chemnitz – Zwickmühle und Schlußfolgerung

https://sezession.de/59357/chemnitz-zwickmuehle-und-schlu...

Fehlerhafte Berichterstattung

Chemnitz: „Tagesthemen“ mischen Hitler-Hooligans in AfD-Demo

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/chemnit...

Broder über Sachsens Regierungschef: "Der Mann ist ein sprachloser Schwätzer"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h9lCyRITtFo

#chemnitz

"Araber stellen die gefährlichste Gruppe" - klare Worte zur Causa Chemnitz

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=40RN37g9IZA

Arabische Großfamilien

Und plötzlich ist die Clan-Kriminalität ein Problem

von Felix Krautkrämer

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/und-plo...

Großclans

Kriminell erzogen

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/kriminell...

"Drogenservice" mit "Bunkerfahrzeug" in Schöneberg

Haftbefehle gegen Mitglieder von arabischer Großfamilie erlassen

https://www.rbb24.de/panorama/beitrag/2018/08/berlin-haft...

Gefängnisse in Deutschland

Fast jeder dritte Häftling ist Ausländer

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/fast-je...

Inhaftierungsraten

Die Mär vom strukturellen Rassismus

von Lukas Mihr

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-maer-...

Video sorgt für Empörung

Ausländer attackieren Polizisten in Plauen

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/auslaen...

Video aufgetaucht: Polizei-Einsatz in Plauen eskaliert

https://www.tag24.de/nachrichten/plauen-postplatz-polizis...

(dazu…)

Gewalt gegen Polizisten

Die „dünne blaue Linie“

von Alice Weidel

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-duenn...

Sextäter am Wochenende

Begrapscht, vergewaltigt, belästigt, mißbraucht

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/gesellschaft/2018/begraps...

Frauen und Mädchen erneut Opfer von Übergriffen

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/frauen-...

Übergriffe und Belästigungen

Beim Joggen und auf dem Heimweg: Sex-Täter überfallen Frauen

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/beim-jo...

Dank Merkels Völkerwanderung: Alle 15 Stunden ein sexueller Übergriff in Leipzig

http://unser-mitteleuropa.com/2018/08/20/dank-merkels-voe...

Rosenheim: Zwei Asylbewerber nach Vergewaltigung verhaftet

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/rosenhe...

Brandenburg

„Bedauerlicher Einzelfall“: Afghanen belästigen Frauen und verletzen Polizist

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/bedauer...

Hamburg

Afghane vergewaltigt 14jähriges Mädchen

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/gesellschaft/2018/afghane...

Niedersachsen

Getötete Obdachlose: Polizei verhaftet Asylbewerber

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/getoete...

Mißbraucht und geschlagen

Hobby-Rapper zwingt 14jährige zur Prostitution: Bewährung

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/gesellschaft/2018/hobby-r...

Offenburg

Nach Messerattacke: Demonstrationen bleiben ruhig

https://www.schwarzwaelder-bote.de/inhalt.offenburg-nach-...

Tatverdächtiger Asylbewerber

Offenburg-Mord: Palmer kritisiert ausbleibende Berichterstattung

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/offenbu...

Unna

Schlägerei am Rathaus: Polizei gibt Statement ab – Weiterer Augenzeuge: „Das war Krieg. Unna hat seine Unschuld verloren.“

https://www.rundblick-unna.de/2018/08/06/schlaegerei-am-r...

Massenschlägerei wird nach Polizeieinsatz fortgesetzt - dann aber mit Waffen

https://www.pz-news.de/pforzheim_artikel,-Massenschlaeger...

Massenschlägereien in Pforzheim: City-Streife stößt an die Grenzen

https://www.pz-news.de/pforzheim_artikel,-Massenschlaeger...

Freiburg

Massenschlägerei mit Verletzten

20 Leute geraten in Regionalzug aneinander

https://www.n-tv.de/panorama/20-Leute-geraten-in-Regional...

Streit über Zwangsverheiratung eskaliert

Zwölf Jahre Haft nach Mordversuch in Offenbach

https://www.op-online.de/offenbach/streit-ueber-zwangsver...

Streit nach Stadtfest in Chemnitz: Ein Toter und zwei Verletzte

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/panorama/streit-stadtfest-ch...

Mia V.

Mordfall Kandel: Afghane zu acht Jahren und sechs Monaten verurteilt

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/gericht...

Nachtclub in Frankfurt Oder

Angriff mit „Allahu Akbar“-Rufen: Bürgermeister prüft Abschiebung

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/angriff...

KULTUR / UMWELT / ZEITGEIST / SONSTIGES

Stephan Trüby bläst erneut linke Trübsal

Linker Architekturtheoretiker wittert überall „Rechte“

http://www.pi-news.net/2018/08/linker-architekturtheoreti...

(Einwanderung, Naturschutz und Städtebau…)

Klima-Oase Frankfurt – keine Spur!

Harmlose Plauderstunde zu Frankfurts Grün- und Bauplanungen

http://www.bff-frankfurt.de/artikel/index.php?id=1327

(3 Jahre alt, aber bezeichnend für das Goethe-Institut)

Tschechien

„Deutsch, fremd und nicht sonderlich sympathisch“

https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article149978357/Deut...

Auslandsrundfunk

„Haßbotschaften“: Deutsche Welle schaltet Kommentarfunktion ab

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/medien/2018/hassbotschaft...

ZDF-Journalisten behindert?

Göring-Eckardt zweifelt an demokratischer Gesinnung Kretschmers

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/goering...

Kontrolle des ZDF-Teams

Einsatz bei Anti-Merkel-Demonstration: Wendt verteidigt Polizisten

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/einsatz...

Mord in Offenburg

Palmer: Gniffke setzt Ruf der Tagesschau aufs Spiel

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/palmer-...

Tagesschau rechtfertigt Verschweigen von Asylantengewalt

http://unser-mitteleuropa.com/2018/08/27/tagesschau-recht...

"Divers" ist das neue Geschlecht: Kabinett beschließt dritte Möglichkeit

https://web.de/magazine/politik/divers-geschlecht-kabinet...

Universitäten

AfD fordert Überprüfung der Gender-Lehrstühle

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/afd-for...

Männerdiskriminierung an der Berliner Humboldt-Uni

Männer sind Schweiger

von Boris T. Kaiser

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/maenner-s...

Feministischer Männerhaß auf Twitter

Jammern und hassen auf höchstem Niveau

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/jammern-u...

Konservativer YouTube-Star

Argumentative Angriffslust

von Björn Harms

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/2018/argumentative-angrif...

Signal für Deutschland – Zeitschrift

https://www.signal-online.de/zeitschrift/

Papier ade´

Die Tageszeitung „taz“ gibt auf: Ende der Printausgabe angekündigt

https://www.tichyseinblick.de/kolumnen/alexander-wallasch...

Vorwürfe gegen den DFB

Manuel Neuer: Özil hat in Nationalelf keinen Rassismus erfahren

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/manuel-...

Gehören die zu uns?

Von Ibrahim Naber

In mehreren Ländern wird während der WM heftig über die Identität der Nationalmannschaft diskutiert. Im Fokus: Spieler mit Migrationshintergrund

https://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/sport/article178943118...

Vielfalt

Wolfsburg-Spieler spricht sich gegen Regenbogenbinde aus

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/2018/wolfsburg-spieler-sp...

Verein Deutsche Sprache

DFB ist „Sprachpanscher des Jahres“

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/2018/dfb-ist-sprachpansch...

Patrick Bahners und die „habituelle Diskriminierung“

Die Abwendung von den Eigenen

von Karlheinz Weißmann

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-abwen...

Konservative in der „Black Community“

Kanye West fürchtet wegen Trump-Lob um Karriere

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/kanye-west-...

Nie zweimal in denselben Fluß. Björn Höcke im Gespräch

https://sezession.de/59327/nie-zweimal-in-denselben-fluss...

Der Riese Marx in Trier

https://irisnieland.wordpress.com/2018/08/22/der-riese-ma...

Duisburg

Sie verdiente mehr als Merkel: Chefin von Behinderten-Werkstatt entlassen

https://www.tag24.de/nachrichten/sie-verdiente-mehr-als-m...

ESC: Türkei bleibt dem Eurovision Song Contest weiterhin fern

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/unterhaltung/musik/esc/esc-t...

(Lebensgefährlicher Trend)

"Balconing" auf Mallorca

Nach 8. Todesopfer: Experten schalten sich ein

https://www.tonight.de/news/aktuelles/balconing-auf-mallo...

Verdrängt die Sprachsteuerung die Fernbedienung?

https://www.internetworld.de/technik/sprachassistent/verd...

Kino

Spike Lees "BlacKkKlansman": Clevere Satire über Rassismus

https://www.volksstimme.de/kino/filmbesprechung/spike-lee...

U2-Sänger

Bono sieht Europa durch Nationalisten gefährdet

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/2018/bono-sieht-europa-du...

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

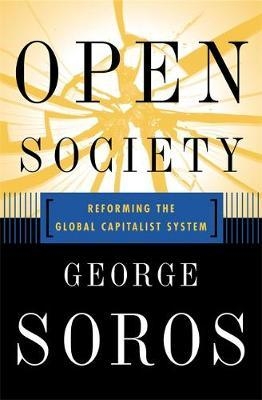

Truyens considera que la elección de Emmanuel Macron es, sin duda, un efecto de la estrategia popperiana de Georges Soros. Macron no tenía un partido detrás, sino un movimiento de muy reciente constitución, puesto en marcha rápidamente según las tácticas aprobadas por la fundación que Soros había aplicado en otras partes del mundo. Tanto si Soros ha financiado como si no el movimiento “En marcha” de Macron, la política de éste, como la de Merkel y otros supuestos “líderes” europeos sigue una lógica Popper-sorosiana de disolución de los pueblos, sociedades y Estados en mayor medida que la lógica sesentayochista derivada de la Escuela de Frankfurt, instrumento que ahora consideran inadecuado porque podría tener los efectos contrarios a los esperados.

Truyens considera que la elección de Emmanuel Macron es, sin duda, un efecto de la estrategia popperiana de Georges Soros. Macron no tenía un partido detrás, sino un movimiento de muy reciente constitución, puesto en marcha rápidamente según las tácticas aprobadas por la fundación que Soros había aplicado en otras partes del mundo. Tanto si Soros ha financiado como si no el movimiento “En marcha” de Macron, la política de éste, como la de Merkel y otros supuestos “líderes” europeos sigue una lógica Popper-sorosiana de disolución de los pueblos, sociedades y Estados en mayor medida que la lógica sesentayochista derivada de la Escuela de Frankfurt, instrumento que ahora consideran inadecuado porque podría tener los efectos contrarios a los esperados.

En tant que théologien et philosophe, il est bien conscient de l’importance de la nécessité pour la société de légitimer religieusement son autorité séculière, d’offrir à son peuple un bouclier contre la terreur et les craintes multiples de la vie par un mythe protecteur qui a été utilisé avec succès par les États-Unis pour terroriser les autres, de montrer comment les termes selon lesquels les États-Unis sont légitimés comme « nation choisie » par Dieu et les Américains comme « peuple élu » par Dieu ont évolué au fil du temps, à la lumière de l’avancée des processus de sécularisation et de pluralisme qui se sont développés. Les noms ont changé, mais la signification est la même. Dieu est de notre côté, et quand c’est ainsi, l’autre côté est maudit et peut être tué par le peuple de Dieu, qui se bat toujours contre le Diable.

En tant que théologien et philosophe, il est bien conscient de l’importance de la nécessité pour la société de légitimer religieusement son autorité séculière, d’offrir à son peuple un bouclier contre la terreur et les craintes multiples de la vie par un mythe protecteur qui a été utilisé avec succès par les États-Unis pour terroriser les autres, de montrer comment les termes selon lesquels les États-Unis sont légitimés comme « nation choisie » par Dieu et les Américains comme « peuple élu » par Dieu ont évolué au fil du temps, à la lumière de l’avancée des processus de sécularisation et de pluralisme qui se sont développés. Les noms ont changé, mais la signification est la même. Dieu est de notre côté, et quand c’est ainsi, l’autre côté est maudit et peut être tué par le peuple de Dieu, qui se bat toujours contre le Diable.

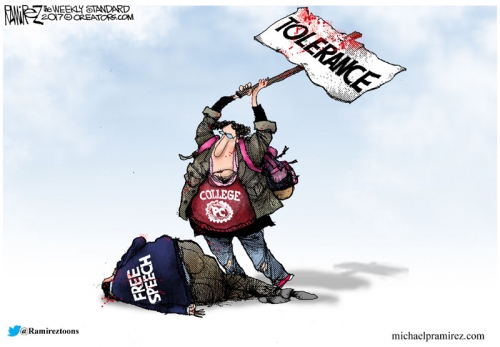

Doug Casey:

Doug Casey: The fact that the average American still puts up with this kind of nonsense and treats it with respect is a bad sign. PC values are continually inculcated into kids that go off to college—which, incidentally, is another idiotic mistake that most people make for both economic and philosophical reasons. It’s a real cause for pessimism.

The fact that the average American still puts up with this kind of nonsense and treats it with respect is a bad sign. PC values are continually inculcated into kids that go off to college—which, incidentally, is another idiotic mistake that most people make for both economic and philosophical reasons. It’s a real cause for pessimism.

Dans Un populisme à l’italienne ?, Jérémy Dousson, directeur général adjoint du magazine Alternatives économiques, apporte un éclairage intéressant. Le livre étudie un véritable « ovni » politique qui a permis l’avènement en Europe du premier « populisme de gouvernement » ! Paru avant les résultats des législatives du 4 mars 2018, l’ouvrage n’évoque pas bien sûr la nouvelle coalition gouvernementale. L’auteur précisait alors que « le mouvement ne s’allie pas avec les partis qui ont échoué; il gouverne seul ou il ne gouverne pas (p. 110) ». Pas sûr toutefois que Jérémy Dousson aurait conservé sa belle sérénité s’il avait appris l’entente avec la Ligue… Pourtant, « en tant que partis qui expriment, d’une manière différente, la mentalité populiste, prévient Marco Tarchi, leurs vues ne sont pas, sur le fond, incompatibles, donc une alliance est possible et, peut-être, viable (1) »

Dans Un populisme à l’italienne ?, Jérémy Dousson, directeur général adjoint du magazine Alternatives économiques, apporte un éclairage intéressant. Le livre étudie un véritable « ovni » politique qui a permis l’avènement en Europe du premier « populisme de gouvernement » ! Paru avant les résultats des législatives du 4 mars 2018, l’ouvrage n’évoque pas bien sûr la nouvelle coalition gouvernementale. L’auteur précisait alors que « le mouvement ne s’allie pas avec les partis qui ont échoué; il gouverne seul ou il ne gouverne pas (p. 110) ». Pas sûr toutefois que Jérémy Dousson aurait conservé sa belle sérénité s’il avait appris l’entente avec la Ligue… Pourtant, « en tant que partis qui expriment, d’une manière différente, la mentalité populiste, prévient Marco Tarchi, leurs vues ne sont pas, sur le fond, incompatibles, donc une alliance est possible et, peut-être, viable (1) » C’est Beppe Grillo qui pose dès le départ les interdits fondamentaux qui rendent le M5S si singulier. Les eletti (élus) n’existent pas, mais il y a des portavoci, les porte-parole. Avant une approbation en ligne sur la plateforme Rousseau, les éventuels candidats à une fonction élective s’engagent à ne pas cumuler de mandat, à n’effectuer que deux mandats consécutifs, à ne pas embaucher des membres de leur famille au titre d’assistants et à ne pas se parachuter dans une circonscription gagnable. Enfin, tous doivent présenter un casier judiciaire vierge. C’est la raison pour laquelle Beppe Grillo n’a jamais été candidat. Outre que « le comique a fait ou fait encore l’objet d’environ quatre-vingt-dix procès (p. 31) » pour des diffamations publiques, il a été condamné en 1981 pur un homicide involontaire lors d’un accident de la route. En 2014, un tribunal l’a aussi condamné à quatre mois de prison pour avoir brisé des scellés apposées sur le chantier du Lyon – Turin (5).

C’est Beppe Grillo qui pose dès le départ les interdits fondamentaux qui rendent le M5S si singulier. Les eletti (élus) n’existent pas, mais il y a des portavoci, les porte-parole. Avant une approbation en ligne sur la plateforme Rousseau, les éventuels candidats à une fonction élective s’engagent à ne pas cumuler de mandat, à n’effectuer que deux mandats consécutifs, à ne pas embaucher des membres de leur famille au titre d’assistants et à ne pas se parachuter dans une circonscription gagnable. Enfin, tous doivent présenter un casier judiciaire vierge. C’est la raison pour laquelle Beppe Grillo n’a jamais été candidat. Outre que « le comique a fait ou fait encore l’objet d’environ quatre-vingt-dix procès (p. 31) » pour des diffamations publiques, il a été condamné en 1981 pur un homicide involontaire lors d’un accident de la route. En 2014, un tribunal l’a aussi condamné à quatre mois de prison pour avoir brisé des scellés apposées sur le chantier du Lyon – Turin (5).

Mais les Jeux Olympiques de 1980 sont passés par là, amenant avec eux une série de magazines sur papier glacé qui montraient comment les gens vivaient dans le monde entier. Ce n’était pas de la propagande et cela ne critiquait personne ; tout était très positif. Il n’y avait pas de comparaison entre deux variétés de pommes ; c’était une exposition, pas un concours. Et donc, ici, nous avions une image d’un soudeur américain qui vivait dans sa propre maison, qui faisait des barbecues avec ses amis et voisins, et qui avait une famille heureuse et une femme dont la cuisine ressemblait au panneau de commande d’un petit vaisseau spatial très stylé.

Mais les Jeux Olympiques de 1980 sont passés par là, amenant avec eux une série de magazines sur papier glacé qui montraient comment les gens vivaient dans le monde entier. Ce n’était pas de la propagande et cela ne critiquait personne ; tout était très positif. Il n’y avait pas de comparaison entre deux variétés de pommes ; c’était une exposition, pas un concours. Et donc, ici, nous avions une image d’un soudeur américain qui vivait dans sa propre maison, qui faisait des barbecues avec ses amis et voisins, et qui avait une famille heureuse et une femme dont la cuisine ressemblait au panneau de commande d’un petit vaisseau spatial très stylé. Tout comme les Jeux olympiques de 1980 ont montré aux Russes à quoi ressemblait la vie en dehors de l’URSS, les matchs de la Coupe du monde 2018 ont montré au monde à quoi ressemble la vie en Russie. L’image de la Russie en tant que Mordor totalitaire, pauvre et en ruines, a été brisée pour laisser apparaître l’image d’une Russie joyeuse, libre, sûre, bien dirigée et prospère. Au fur et à mesure que cette réalité suinte, de plus en plus d’Américains doivent commencer à penser qu’ils ne seraient pas du tout opposés à vivre comme les Russes, sans déménager en Russie, mais d’amener un peu de Russie dans leur pays d’origine. Plus précisément, beaucoup d’entre eux ne verraient pas de problème à avoir une direction un peu à la Poutine, respecté, et faisant autorité tout en étant autoritaire, compétent et populaire, au lieu de ces faces indignes et leurs bandes d’amis et d’ennemis que l’on ne peut pas distinguer.

Tout comme les Jeux olympiques de 1980 ont montré aux Russes à quoi ressemblait la vie en dehors de l’URSS, les matchs de la Coupe du monde 2018 ont montré au monde à quoi ressemble la vie en Russie. L’image de la Russie en tant que Mordor totalitaire, pauvre et en ruines, a été brisée pour laisser apparaître l’image d’une Russie joyeuse, libre, sûre, bien dirigée et prospère. Au fur et à mesure que cette réalité suinte, de plus en plus d’Américains doivent commencer à penser qu’ils ne seraient pas du tout opposés à vivre comme les Russes, sans déménager en Russie, mais d’amener un peu de Russie dans leur pays d’origine. Plus précisément, beaucoup d’entre eux ne verraient pas de problème à avoir une direction un peu à la Poutine, respecté, et faisant autorité tout en étant autoritaire, compétent et populaire, au lieu de ces faces indignes et leurs bandes d’amis et d’ennemis que l’on ne peut pas distinguer.

Il protestantesimo, e a maggior ragione le sue derive fondamentaliste, costituiscono dunque la recisa opposizione al Cristianesimo “tradizionale”, annoverando tra i loro principi fondanti un’antropologia tendenzialmente disincarnata, il recupero di una dimensione morale che sfocia spesso nel moralismo, la tesi della predestinazione assoluta calvinista, che rischia di ridurre l’uomo a “burattino” della divinità, la critica del ritualismo cattolico; si aggiungano a ciò il totale misconoscimento della nozione di gerarchia, operato in virtù di un livellamento democratico ed egualitario tipicamente anglosassone, e la commistione tra un’ostentata morigeratezza pubblica (cui non sempre corrisponde un’analoga condotta privata…) ed un individualismo che trova la sua sublimazione nel liberismo economico: uno dei classici topoi, quest’ultimo, del discorso di certo protestantesimo, estremizzato dalla asserzione calvinista secondo cui il successo economico è segno della benedizione divina. A questo proposito, si dovrà prima o poi riconoscere che le presunte “conquiste” della società postmoderna (comunque quasi esclusivamente di ordine tecnologico e materiale) dipendono in larga misura dal notevole abbassamento degli standards morali in uso presso la civiltà occidentale

Il protestantesimo, e a maggior ragione le sue derive fondamentaliste, costituiscono dunque la recisa opposizione al Cristianesimo “tradizionale”, annoverando tra i loro principi fondanti un’antropologia tendenzialmente disincarnata, il recupero di una dimensione morale che sfocia spesso nel moralismo, la tesi della predestinazione assoluta calvinista, che rischia di ridurre l’uomo a “burattino” della divinità, la critica del ritualismo cattolico; si aggiungano a ciò il totale misconoscimento della nozione di gerarchia, operato in virtù di un livellamento democratico ed egualitario tipicamente anglosassone, e la commistione tra un’ostentata morigeratezza pubblica (cui non sempre corrisponde un’analoga condotta privata…) ed un individualismo che trova la sua sublimazione nel liberismo economico: uno dei classici topoi, quest’ultimo, del discorso di certo protestantesimo, estremizzato dalla asserzione calvinista secondo cui il successo economico è segno della benedizione divina. A questo proposito, si dovrà prima o poi riconoscere che le presunte “conquiste” della società postmoderna (comunque quasi esclusivamente di ordine tecnologico e materiale) dipendono in larga misura dal notevole abbassamento degli standards morali in uso presso la civiltà occidentale

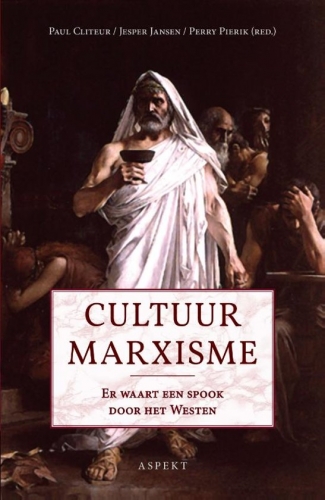

Het probleem van zo’n essaybundel, waarin we naast Cliteur namen terugvinden als

Het probleem van zo’n essaybundel, waarin we naast Cliteur namen terugvinden als  Sid Lukkassen komt tot een andere conclusie: de culturele hegemonie van links moeten we laten voor wat ze is. We moeten compleet nieuwe, eigen media, netwerken en instellingen oprichten die niet ‘besmet’ zijn door het virus en voor echte vrijheid gaan: ‘De enige weg voorwaarts is dus het scheppen van een eigen thuishaven, een eigen Nieuwe Zuil met bijbehorende instituties en cultuurdragende organen. Die alternatieve media zijn volop aan het doorschieten, Doorbraak is er een van.

Sid Lukkassen komt tot een andere conclusie: de culturele hegemonie van links moeten we laten voor wat ze is. We moeten compleet nieuwe, eigen media, netwerken en instellingen oprichten die niet ‘besmet’ zijn door het virus en voor echte vrijheid gaan: ‘De enige weg voorwaarts is dus het scheppen van een eigen thuishaven, een eigen Nieuwe Zuil met bijbehorende instituties en cultuurdragende organen. Die alternatieve media zijn volop aan het doorschieten, Doorbraak is er een van.

Un Maître espion « représentant personnel du président Macron pour la Syrie »

Un Maître espion « représentant personnel du président Macron pour la Syrie »