De Laatste Golf

Reader’s Digest voor een zwart jaargetijde

door Alexander Wolfheze

Hear the trumpets, hear the pipers

One hundred million angels singing

Multitudes are marching to the big kettledrum

Voices calling, voices crying

Some are born and some are dying

It’s Alpha and Omega’s kingdom come

‘Hoor de bazuinen schallen en de fluiten schellen

Honderd miljoen engelen zingen

Mensenmassa’s marcheren achter de grote keteldrommen

Stemmen roepen, stemmen schreeuwen

Geboorte uur en stervensuur

Alfa en Omega hier en nu: Uw Koninkrijk kome’

- Johnny Cash, ‘The Man Comes Around’

(*) De auteur zal in dit essay de termen ‘wit’ en ‘blank’ pragmatisch gebruiken. Alhoewel hij van mening is dat het prachtig - subtiele - Nederlandse woord ‘blank’ de enig cultuur-historisch juiste term is voor de fenotypische typering van het (inheems-)Nederlandse volk, stelt hij zich ook op het standpunt dat dit essay een flexibel woordgebruik vergt voor een efficiënte bestrijding van het discours van de globalistische vijandige elite. Vanuit het perspectief van Nieuw Recht is het noodzakelijk dat de patriottisch-identitaire revolutie tegen de globalistische vijandige elite het hele politieke-correcte discours van die elite deconstrueert. Nieuw Rechts behoudt zich uitdrukkelijk het recht voor tot omgekeerde ‘culturele appropriatie’ van alle psy-op woord-fabricaties van de globalistische pseudo-intelligentsia - inclusief het woordje ‘wit’ voor blank. Nieuw Rechts laat zich niet in de gedachten dwangbuis van het totalitair-nihilistisch globalistisme stoppen, noch door politiek-correct woordgebruik, noch door dwangmatig afgedwongen ‘purisme’. De eindoverwinning in de metapolitieke jungleoorlog tegen het totalitair-nihilistisch globalisme vergt niets minder dan een totaaltoe-eigening van het hele vijandelijke woord- en gedachtearsenaal.

Voorwoord: ‘Paint it, Black’

(cultureel-anthropologische overwegingen)

I see a red door and I want it painted Black

No colors anymore, I want them to turn Black

‘Ik zie een rode deur - ik wil haar zwart schilderen

Het einde van de kleur - ik wil alles zwart maken’

- The Rolling Stones

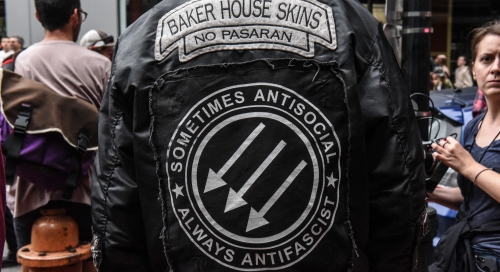

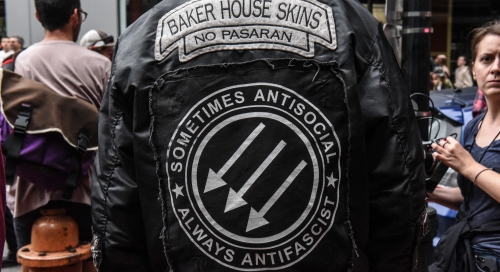

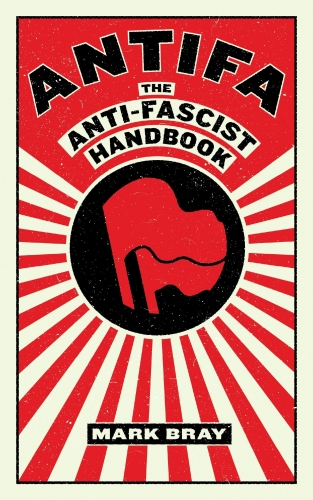

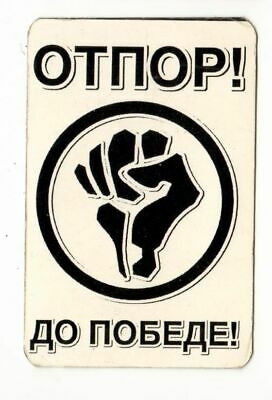

Antifa wordt nu algemeen erkend als hoofdrolspeler in de Black Lives Matter (BLM) machtsgreep van extreem-links en het is belangrijk dat Nieuw Rechts een goed beeld heeft van Antifa’s huidige motivaties. Antifa is al sinds de grote (fascistisch/nationaal-socialistische) anti-globalistische opstand van de jaren ’20 wn ’30 de straatvechters arm van de globalistische vijandige elite, maar haar rol heeft zich gedurende de afgelopen decennia steeds consistent aangepast aan de wisselende behoeften van het vigerende globalisme. De Grote Westerse Burger Oorlog, waarvan de ‘warme’ en ‘koude’ fases eindigden in 1945 en 1990, is weliswaar geëindigd in de formele overwinning van het globalisme, maar Antifa is nog steeds een nuttige organisatie voor zuivering- en politionele acties tegen hier en daar overblijvende weerstandsnesten. Antifa ontleent weliswaar haar naam aan de oudste en gevaarlijkste vijanden van het globalisme, namelijk het Europese fascisme, maar de organisatie heeft haar tactiek continu aangepast aan de strijd tegen de latere en mindere vijanden van het globalisme - in het huidige tijdsbestek zijn ‘nationaal-populistische’ politiek, ‘alt-right’ digi-activisme en Nieuw Rechtse meta-politiek de belangrijkste van die vijanden. Met een combinatie van ouderwets storm troep geweld, digitaal-opgewaardeerde surveillance en innovatieve sociale media ‘doxxing’ heeft de Antifa de globalistische vijandige elite geholpen de anti-globalistische onrustgolf van midden jaren ’10 te breken - het was deze golf die Donald Trump het Witte Huis en Boris Johnson Down Street 10 inloodste en die het hele bouwwerk van de Nieuwe Wereld Orde op zijn grondvesten deed schudden. Maar het recente defensieve postuur van de globalistische vijandelijke elite, gericht op het saboteren van Trump en Brexit, moeten worden begrepen voor wat zij zijn: achterhoede gevechten en storingsacties die tijd winnen voor een nieuw globalistisch offensief - een grootschalig eindoffensief dat ten doel heeft het anti-globalisme voor eens en altijd weg te vagen. C’était reculer pour mieux sauter.

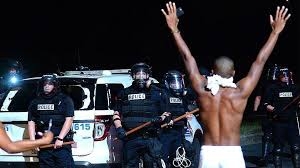

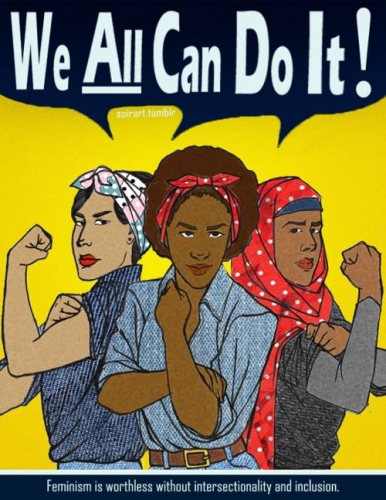

Het huidige globalistische tegenoffensief is weliswaar getimed op de ontsporing van Trump’s herverkiezing, in november 2020, maar de einddoelen ervan zijn veel ambitieuzer: het begint nu de richting en omvang aan te nemen van een slotoffensief - een alles-of-niets poging om de Westerse beschaving omver te werpen. Het lijkt goed doordacht te zijn gefaseerd in perfect geregisseerde ‘golven’. De eerste van deze wag the dog golven, de zgn. ‘Corona Crisis’ van voorjaar 2020, had overduidelijk een shock and awe doel: zij beoogde de intimidatie, verlamming en demoralisatie van de inheems-Westerse volksmassa’s - en het teniet doen, met één enkele klap, van de met bloed, zweet en tranen gekochte economische en politieke successen van Trump’s eerste ambtsperiode en Johnson’s Brexiteer regering. De tweede golf, de zgn. ‘BLM Crisis’ van zomer 2020, dient het uitbuiten van het succes van de eerste golf: zij beoogt het afkappen van de psycho-historische verbindingslijnen van de inheems-Westerse volksmassa’s met hun cultuur en hun identiteit door het wegnemen van hun laatste stukje veiligheid en continuïteit in de (fysieke en digitale) publieke ruimte - en door hun leiders tot electorale zelfmoord te dwingen met een keuze tussen brutale onderdrukking of abjecte capitulatie ten aanzien van de BLM uitdaging. Antifa speelt een essentiële rol in deze globalistische greep naar totalitaire controle over de Westerse publieke ruimte: de storm troepen van Antifa bieden fysieke focuspunten en tastbare provocatie kansen voor de verwezenlijking van een daadwerkelijke, effectieve ont-westering van de publieke ruimte. Deze ont-westering wordt gekenmerkt door de opzettelijke import van de typische eigenschappen van de publieke ruimte in de Derde Wereld: sporadische wetshandhaving, bende heerschappij, permanente onveiligheid, chaotische verkeersstromen, haperende infrastructuur, bergen zwerfvuil, vernielde groenvoorzieningen, dierenmishandeling en geruïneerde architectuur. De BLM golf introduceert deze eigenschappen opzettelijk in de Westerse urbane ruimt: kleine maar veelbetekenende signalen druppelen binnen via de alternatieve media - scènes van ‘activisten’ die politiebureaus aanvallen, winkels plunderen, publiek hun behoeften doen, parken ‘tuinieren’, huisdieren doden en standbeelden omverwerpen. De materiële ont-westering van de publieke ruimte wordt noodzakelijkerwijs gespiegeld in haar menselijke ont-westering: zwart-, bruin- en licht-getinte gezichten overheersen de nieuwe as-en-stof ex-Westerse stadslandschappen.

De Paint It Black ‘kleurenrevolutie’[1] van de BLM Crisis staat onder het teken van de rood-zwarte - anarcho-communistische - Antifa vlag. De thematische keuze voor de kleur zwart geeft essentiële informatie over de doelstelling achter de BLM revolutie: het is de kleur die symbolisch wordt geassocieerd met nacht, duister, wetteloosheid, zonde, gevaar en dood - de tegenpool van de kleur wit die staat voor dag, licht, wet, puurheid, veiligheid en leven. Het mooie Nederlandse woord dekt slecht een deelaspect van deze wit-associaties, maar voegt er subtiele betekenissen aan toe: in abstracto transparant en zuiver, in concreto pigmentarme huidskleur. Deze toegevoegde dimensies zijn essentieel voor de inheems-Nederlandse identiteit: de associatie met transparantie en zuiverheid hangt samen met typisch Nederlandse levensdoelen (ook financiële) ‘schuldvrijheid’, (ook botte) ‘eerlijkheid’ en (vooral fysieke) ‘properheid’ - de associatie met blanke huidskleur hangt samen met historisch-onloochenbare raciale en etnische afkomst. Deze speciale blank-associaties zetten de Nederlandse tak van de globalistische vijandige elite voor een ironisch dilemma: ófwel het internationale ‘zwart-goed/wit-slecht’ standaard-narratief invoeren en onnatuurlijk - geforceerd, kunstmatig - overkomen, ófwel een semantische - en dus abstracte, moeizame - discussie aangaan en daarin verzanden. Geheel voorspelbaar op de weg van de minste weerstand hebben de Nederlandse capo regimes van het globalisme - oikofobe intelligentsia, MSM top, partijkartel ideologen - gekozen voor de terminologie optie ‘wit’: zij vertrouwen op de accumulatieve effecten van post-Mammoet Wet ‘idiocratie’, maar geven daarmee de patriottisch-identitaire oppositie wel zelf het wapen in handen van het oudere, beschaafdere en mooiere ‘blank’.

En zo zitten de deugende ‘pratende klasse’ van Nederland - politiek-correcte politici, eindredacteuren, journalisten en publicisten - nu opgescheept met het goedkope, gekunstelde en lelijke ‘wit’. Maar hoe braaf zij ook hun best doen om ook met deze handicap de globalistische lijn binnenlands aan de man te brengen, zij zich blijkbaar onbewust van een veel groter gevaar, namelijk het existentiële gevaar van het klakkeloos toepassen van een conflict-symboliek die zijn dynamiek put uit een universeel-menselijke affect-oppositie: de associate wit-goed/zwart-slecht. Het gaat hier om universeel-menselijke symboliek die direct samenhangt met existentiële affecten - deze laat zich niet straffeloos misbruiken. Wat de Paint It Black BLM kleurenrevolutie feitelijk doet is een onmiskenbaar eenduidig signaal afgeven: dat de BLM revolutie zich richt tegen alles dat (ver)licht, open, legaal, onschuldig, veilig en gezond is en dat zij zich associeert met alles wat duister, gesloten, illegaal, onveilig en ziek is. De BLM kleurenrevolutie beoogt - en creëert - sociaal, etnisch en raciaal conflict door een tweevoudige - waarachtig gespleten tong - leugen: (a) zij associeert abstracte en symbolische (ethische, esthetische) categorieën met concrete en menselijke (etnische, raciale) categorieën en (b) zij draait die categorieën om, resulterend in een kortsluiting tussen de oorspronkelijke positieve en negatieve ladingen. Een vereenvoudigde structuralistische analyse van deze BLM leugens wordt in de volgende ‘stenografische’ stelling weergegeven:

(1) - [zwart : nacht : slecht] :: + [wit : dag : goed] >

(a) 0 [zwarte mensen : zonsopgang : gelijkheid] :: 0 [witte mensen : zonsondergang : gelijkheid] >

(b) + [zwarte mensen : verlicht : goed] :: - [witte mensen : verduisterd : slecht] >

(2) zwarte leven (actief, vooruitgang) - witte dood (passief, achteruitgang) = 0 (som spel)

Zo laat de Paint It Black BLM kleurenrevolutie zich herkennen als opzettelijke psychologische oorlogsvoering: het gaat om een black op van de globalistische vijandige elite, gericht op niet meer of minder dan een culturele revolutie - een reset van de klok van de geschiedenis. Ook laat zij zich herkennen als een ‘nul som spel’ dat met wiskundige zekerheid op een heuse rassenoorlog uitloopt - ook als deze oorlog vooralsnog meer in de institutionele, juridische en culturele sfeer afspeelt dan op straat. Er is maar één mogelijke uitkomst van een daadwerkelijk verwezenlijkte BLM kleurenrevolutie, namelijk een radicale omkering van de raciale verhoudingen: blanke slavernij. Haar expliciet sado-masochistische semantiek en symboliek spreekt in dit opzicht boekdelen: blanken moeten knielen, zwarte voeten kussen en boete doen. De BLM kleurenrevolutie mag slechts een klein stapje lijken in de geschiedenis van het Westen, maar zij is een grote sprong in een scenario dat zelfs de meest doemdenkende en paranoïde ‘blank-nationalistische’ ideologen zich tot nu toe niet konden voorstellen. Tot nu toe was het ‘blank-nationalistische’ worst case scenario een relatief simpele rassenoorlog eindigend met de systematische uitroeiing van het blanke ras, maar dit scenario lijkt hoe langer hoe meer op naïef wishful thinking. De BLM trend naar structurele omkering van rolpatronen schetst namelijk een veel erger scenario: een ziekelijke Zwart/Morlock versus Blank/Eloi symbiose, waarbij dan ook nog de meeste Eloi voordelen toevallen aan de Morlocks.[2] In dit scenario eindigt de war of whiteness van de vijandige elite niet in de fysieke uitroeiing van blanken, maar in de doelbewuste (zelf-)reductie van blanken tot Untermensch status: blanken vervullen dan de rol van ‘lastdieren’ (werken om anderen materieel comfort en vrije tijd te geven), ‘status huisdieren’ (bedienen van rap(p)er en role-playing fantasieën) en ‘zondebokken’ (botvieren en compenseren van minderwaardigheidscomplexen). In het huidige Westen zijn de eerste contouren van een dergelijk rolpatroon omkering allang zichtbaar: levende blanke mannen dienen als ‘belasting melkvee’ om grote groepen niet-blanke kolonisten te onderhouden, levende blanken vrouwen dienen als ‘fokvee’ om de ‘diepere’ aspiraties van deze groepen te verwezenlijken en dode blanke mannen - staatslieden, denkers, artiesten - dienen als bliksemafleider voor opzettelijk opgestookte niet-blanke minderwaardigheidscomplexen.

De BLM kleurenrevolutie is een breekpunt in de Westerse geschiedenis: de globalistische vijandige elite is haar Rubicon overgestoken en heeft zich nu niet alleen openlijk gekeerd tegen de Westerse beschaving, maar ook tegen de Westerse volkeren. Beide zijn essentieel blank: zij staan en vallen samen. Door haar ‘progressieve’ narratief opzettelijk parallel te trekken met de raciale scheidslijn en door niet-blanken op te zetten tegen blanken heeft de globalistische vijandige elite eindelijk haar oude claim als legitiem gezag over de Westerse volkeren achter zich gelaten. De globalistische vijandige elite heeft blijkbaar besloten va banque te spelen: blijkbaar voelt zij zich na decennia van omvolking-door-massa-immigratie nu sterk genoeg (lees demografisch-electoraal gesterkt) om in te zetten op haar Endsieg. Deze globalistische eindoverwinning staat gelijk aan de vernietiging van de Westers/blanke beschaving in haar hartland en de marginalisatie van de Westers/blanke volkeren in hun historische stamlanden. Voor de globalistische vijandige elite zijn de niet-blanke minderheden en immigrantenmassa’s slechts een wapen - maar wel een essentieel wapen: zij manipuleert en mobiliseert deze groepen om alle oude grenzen, instituties, monumenten, ideeën en kunstvormen van de Westerse beschaving weg te vagen. Het is redelijk om aan te nemen dat de huidige BLM golf van massademonstraties, chaos, vandalisme en beeldenstormend geweld slechts de eerste fase is van deze niet-Westerse/niet-blanke mobilisatie tegen de Westers/blanke beschaving.

De hoofdwerkzaamheden van dit eerste-fase activisme is door de globalistische vijandige elite uitbesteed aan haar Antifa storm troepen. Om deze vijand effectief te bestrijden is het nodig zijn geestesgesteldheid te kennen: Nieuw Rechts moet weten hoe de Antifa storm troepen denken - hoe hun dirigenten en sponsoren van Antifa willen dat zij denken. Laten wij Antifa daarom eens reduceren tot zijn - dubbel logische en absurde - essentie door die denktrend tot in de uiterste consequentie te volgen. En als die essentie kwaadaardig is, dan dienen we te onthouden dat zelfs de hel haar helden heeft.

‘De protocollen van Antifa’

(psycho-historische antecedenten)

Hell is empty and all the devils are here

‘De hel is leeg - alle duivels zijn hier’

- William Shakespeare, ‘The Tempest’

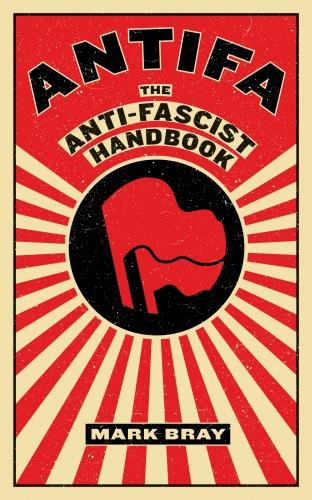

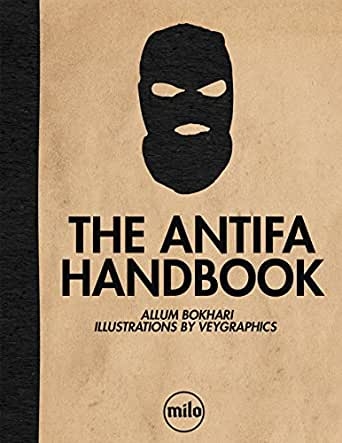

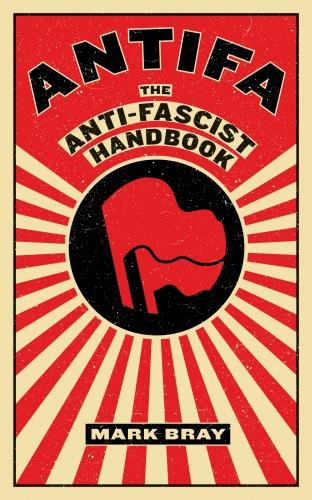

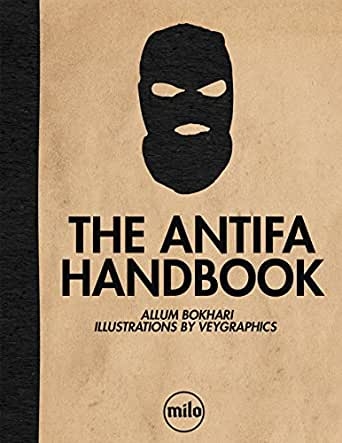

In augustus 2017, rond de tijd van de met black ops gesaboteerde Charlottesville Rally, begon in de sociale media van dissident-rechts een pamfletachtig document te circuleren met de titel The Antifa Manual, ‘Het Antifa Handboek’. Er gaan verschillende geruchten rond omtrent de dubieuze oorsprong van dit ‘handboek’: in de meest gangbare versie werd het gevonden op de campus van het Evergreen State College (Olympia, in de Amerikaanse staat Washington) en de (niet-uitgesloten maar ook wel erg voorspelbare) MSM consensus is dat het gaat om een vervalsing door ‘blank-suprematistische’ agents provocateurs.[3] Maar zelfs als dat klopt - of als het gaat om een satire in de stijl van MS Found in a Bottle[4] - dan nog is ‘Het Antifa Handboek’ nuttig als een ‘teken des tijds’: het duidt een opkomend getij van anti-Westers/blank sentiment. In die zin is ‘Het Antifa Handboek’ een vroeg-21e eeuwse tegenhanger van het beruchte vroeg-20e eeuwse document dat bekend staat onder de titel ‘De Protocollen van de Wijzen van Zion’ - ook verondersteld een vervalsing te zijn, en ook gewijd aan een veronderstelde anti-Westerse samenzwering.

In augustus 2017, rond de tijd van de met black ops gesaboteerde Charlottesville Rally, begon in de sociale media van dissident-rechts een pamfletachtig document te circuleren met de titel The Antifa Manual, ‘Het Antifa Handboek’. Er gaan verschillende geruchten rond omtrent de dubieuze oorsprong van dit ‘handboek’: in de meest gangbare versie werd het gevonden op de campus van het Evergreen State College (Olympia, in de Amerikaanse staat Washington) en de (niet-uitgesloten maar ook wel erg voorspelbare) MSM consensus is dat het gaat om een vervalsing door ‘blank-suprematistische’ agents provocateurs.[3] Maar zelfs als dat klopt - of als het gaat om een satire in de stijl van MS Found in a Bottle[4] - dan nog is ‘Het Antifa Handboek’ nuttig als een ‘teken des tijds’: het duidt een opkomend getij van anti-Westers/blank sentiment. In die zin is ‘Het Antifa Handboek’ een vroeg-21e eeuwse tegenhanger van het beruchte vroeg-20e eeuwse document dat bekend staat onder de titel ‘De Protocollen van de Wijzen van Zion’ - ook verondersteld een vervalsing te zijn, en ook gewijd aan een veronderstelde anti-Westerse samenzwering.

Voor lezers die minder bekend zijn met laatstgenoemd document zal de schrijver van dit opstel een fragment uit zijn boek Sunset vertalen: ‘Historisch gesproken is het belangrijkste “bewijs” document voor een “Joods wereld complot” het pamflet met de titel “De Protocollen van de Wijzen van Zion” dat voor het eerst verscheen in 1903 in de Russische nationalistische krant Znamya (“Banier”). Dit pamflet zegt een verslag te zijn van een 19e eeuwse vergadering van Joodse “ouderlingen” met betrekking tot een programma ter bewerkstelliging van Joodse wereldheerschappij - het geeft tevens de essentie weer van anti-semitisch samenzweringsdenken.[5] Dit pamflet, waarschijnlijk een vervalsing en wellicht gefabriceerd door Russische “Zwarte Honderden” nationalisten, werd al snel naar vele talen vertaald en kreeg in korte tijd een wereldwijde status als anti-semitisch standaard-kost. De aanvankelijke verspreiding in Rusland viel samen met de Russische nederlaag in de Russisch-Japanse Oorlog (1904-05) en de erop volgende geweldsgolf van de Eerste Russische Revolutie (1905-06) - het versterkte de wijdverspreide mening dat “Joodse ondermijning” verantwoordelijk was voor Rusland’s internationale zwakte en binnenlandse instabiliteit. Na geheim valsheid-in-geschrifte onderzoek door premier Stolypin gelastte Tsaar Nicolaas II een publicatie-verbod van de “Protocollen”, maar de verdere verspreiding ervan door illegale drukpersen bleek nauwelijks te bestrijden. Het staat buiten kijf dat de verspreiding van de “Protocollen” bijdroeg tot het steeds verder oplaaien van het anti-semitisme in Rusland - vooral toen de gebeurtenissen van de Grote Oorlog (1914-1918), de Tweede Russische Revolutie (1917) en de Russische Burger Oorlog (1917-1923) de quasiprofetieën van de “Protocollen” zeer accuraat uit leken te doen komen. Het dient te worden genoteerd dat de dubieuze historische authenticiteit van de “Protocollen” geenszins afbreuk doet aan hun ontegenzeggelijke historische betekenis. Eerder is het zo dat de “Protocollen” expliciet uitdrukking geven aan het grootste maar bijna steeds onuitgesproken vraagstuk van de 20e eeuwse mensheid: het escalerende conflict tussen Moderniteit en Traditie - en de eindstrijd tussen de achter deze twee abstracties verborgen principes. Als men het zogenaamde “Joodse wereld complot” begrijpt als “dwars-referentie” naar het conglomeraat van mondiale Modernistische ondermijning, dan kan men zonder meer stellen dat de “Protocollen” de achter het Modernisme verscholen negatieve principes en tendensen uitermate juist schetst.’[6]

De schrijver van dit essay meent dat “Het Antifa Handboek” van soortgelijk waardevolle diagnostische waarde is: dit document geeft expliciete uitdrukking aan een hoogst belangrijke spirituele - of juister: anti-spirituele - tendens in het vroeg-21e eeuwse Westen, op dezelfde manier dat de “Protocollen” dat deden in het vroeg-20e eeuwse Rusland. Deze diagnostische waarde wordt wellicht het best verwoord door de Traditionalistisch denker Julius Evola: ‘Afgezien van de kwestie van de ‘authenticiteit’ van het document in kwestie, als al dan niet waarachtige protocol van een vermeend internationaal machtsnetwerk, is het enig belangrijke en essentiële punt het volgende: dat dit geschrift onderdeel is van een groep teksten die op verschillende manieren (sommige min of meer fantaserend en sommige regelrecht fictief) uitdrukking geven aan een algemeen gevoel dat de wanorde van de afgelopen jaren geen toeval is, maar toe te schrijven is aan een plan. De fasering en het basisinstrumentarium van dit plan worden accuraat beschreven in de “Protocollen”. ...In zekere zin kan men stellen dat daarin een profetisch voorgevoel tot uitdrukking komt. Hoe dan ook is de waarde van het document onweerlegbaar als werkhypothese: het presenteert de verschillende aspecten van mondiale beschavingsondermijning (waaronder aspecten dit pas vele jaren na de publicatie van de “Protocollen” zouden worden gerealiseerd) als onderdelen van een groter geheel waarin ze op hun plaats vallen als logischerwijs en noodzakelijkerwijs samenhangend. ...Het is moeilijk te ontkennen dat deze literaire “fictie”, ontmaskerd aan het begin van [de 20e] eeuw, toch een accurate voorafspiegeling biedt van veel dat later realiteit is geworden in de loop van de moderne “vooruitgang” - en dan hebben we het nog niet over de voorspellingen die het hebben over wat ons nog verder te wachten staat. Het moet ons daarom niet verbazen dat de “Protocollen” zoveel aandacht hebben gehad binnen allerlei bewegingen die in het recente verleden hebben gepoogd het grote getij van nationaal, sociaal en moraal verval te keren.’[7]

Het staat buiten kijf dat ‘Het Antifa Handboek’ de psychologische essentie van Antifa goed tot haar recht doet komen. Het inzicht dat Nieuw Rechts eraan kan ontlenen reduceert Antifa’s zorg voor ‘zwarte levens’ (Black Lives Matter betekent immers ‘zwarte levens tellen’) tot haar ware proporties - Antifa wordt erdoor ontmaskerd als een bende huurlingen, bandieten, criminelen en vandalen in dienst van veel grotere en veel duisterder machten: ‘De enige leven die tellen [voor Antifa activisten] zijn hun eigen levens en de enige macht die ze nastreven is hun eigen macht. Zij zijn wolven in wolfskleding, gemaskerd als dieven en bandieten, slechts uit op het verwoesten van de levens van de armen en het profiteren van de angst van alle anderen. Het zijn niet anders dan mades en parasieten die leven van isolatie, vervreemding, verslaving en gebroken familiestructuren - het enige perspectief dat ze bieden is de vervanging van de huidige frustratie en angst door nog meer ongeluk en nog groter ressentiment (Theodore Rothrock, 28 juni 2020[8]).

Het staat buiten kijf dat ‘Het Antifa Handboek’ de psychologische essentie van Antifa goed tot haar recht doet komen. Het inzicht dat Nieuw Rechts eraan kan ontlenen reduceert Antifa’s zorg voor ‘zwarte levens’ (Black Lives Matter betekent immers ‘zwarte levens tellen’) tot haar ware proporties - Antifa wordt erdoor ontmaskerd als een bende huurlingen, bandieten, criminelen en vandalen in dienst van veel grotere en veel duisterder machten: ‘De enige leven die tellen [voor Antifa activisten] zijn hun eigen levens en de enige macht die ze nastreven is hun eigen macht. Zij zijn wolven in wolfskleding, gemaskerd als dieven en bandieten, slechts uit op het verwoesten van de levens van de armen en het profiteren van de angst van alle anderen. Het zijn niet anders dan mades en parasieten die leven van isolatie, vervreemding, verslaving en gebroken familiestructuren - het enige perspectief dat ze bieden is de vervanging van de huidige frustratie en angst door nog meer ongeluk en nog groter ressentiment (Theodore Rothrock, 28 juni 2020[8]).

‘Black Lies Matter’

(psycho-politieke uitgangspunten - RE: ‘Het Antifa Handboek’[9])

I look inside myself and see my heart is Black

I see my red door, I must have it painted Black

Maybe then I’ll fade away and not have to face the facts

It’s not easy facing up, when your whole world is Black

‘Ik kijk naar binnen - ik zie mijn zwarte hart

Ik zie mijn rode deur - ik moet haar zwart geschilderd hebben

Misschien zal ik nu vervagen - hoef ik de harde waarheid niet te zien

Moeilijk is het om omhoog te kijken als je de hele wereld zwart ziet’

- The Rolling Stones

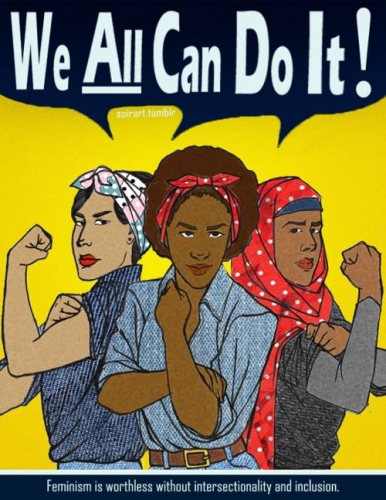

Do not distribute to any cis white males, non-PoC, non-LGBTQ peoples, a.k.a. fascists. ‘Niet doorgeven aan cis-blanke mannen, niet-kleurlingen, niet-LGBTQ mensen, d.w.z. fascisten.’

(*) New Speak[10]: ‘cis-geslacht’ = (niet-transsexueel) geboorte geslacht; PoC afkorting voor Engels People of Colour, ‘mensen met een kleur’ (effectief dus alle niet-blanken); LGBTQ = Engels Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender-Queer, ‘lesbisch, homoseksueel, biseksueel, transgender, twijfelend’ (effectief dus alle alloseksuele geaardheden[11]). Notities: (1) blanke vrouwen vallen niet onder de categorie ‘fascisten-door-geboorte’: blijkbaar nemen zij een geprivilegieerde positie in, ófwel direct, als begunstigde partij in een man-vrouw oorlog, ófwel indirect, als willige ‘oorlogsbuit’ in een blank-zwart oorlog; (2) blanke transgender ex-mannen vallen ook niet onder de categorie ‘fascisten’: blijkbaar worden ‘zelf-gecastreerde’ blanke mannen gewaardeerd als over/meelopers; (3) ‘kleurlingen’ is een zeer brede categorie: blijkbaar mikt de globalistische vijandige elite op een pragmatische alliantie, of althans een tijdelijke wapenstilstand, met gele en bruine mensen tegen de blanke hoofdvijand; (4) de globalistische vijandige elite eerste en laatste obsessie met (liefst perverse) seksualiteit (van transgender tot LGBTQ) legt haar ultieme psychologische wortels bloot: die wortels liggen in feminisme, feminisatie en misandrie. Het einddoel van de globalistische vijandige elite lijkt te liggen in het vestigen van een mondiaal matriarchaat door het systematisch elimineren van de meest formidabele vijand: blanke mannen. Anderskleurige mannen (blijkbaar verondersteld te vallen in de categorieën als ‘laag-IQ’, useful idiot of ‘edele wilde’) worden blijkbaar verondersteld ongevaarlijk te zijn: blijkbaar valt hen de rol van matriarchale buit toe - naar wens controleerbaar en manipuleerbaar.[12] Vanzelfsprekend is deze veronderstelling typisch-feministisch naïef en irreëel: het matriarchaat mag dan graag exotische mannen selecteren en importeren, maar zodra er teveel van worden geïmporteerd is het slechts een kwestie van tijd totdat ze de macht overnemen. Deze wiskundige zekerheid wordt in het Westen nu al zichtbaar in het beginnend uiteenvallen van de feministisch-islamistische alliantie die tot voor kort nog in de politiek-correcte MSM overheerste: het hele matriarchale project begint nu al te falen.

[C]is white males have inherent privilege in our society. This is the basis on which people of color, LGBTQ, the disabled, and other groups that need protection will level the playing field and form a New World Order, a.k.a. One World Government. A government by protected classes of people, for protected classes of people, for the protection and betterment of all of humanity. ‘Cis-gender blanke mannen hebben een inherent privilege in onze maatschappij. Dat is het uitgangspunt waarmee kleurlingen, LGBTQers, gehandicapten en andere beschermingsbehoeftige groepen het maatschappelijk speelveld willen effenen en een Nieuwe Wereld Orde willen vestigen. Dat betekent een Wereld Regering, een regering door beschermingsbehoeftige klassen voor beschermingsbehoeftige klassen - ter bescherming en verbetering van de hele mensheid.’

(*) New Speak: (1) ‘inherent privilege’/ ‘beschermingsbehoeftige klassen’ = dubbele New Speak taal-inversie: van klassiek-marxistische ‘klassenstrijd’ naar cultuur-marxistische ‘privilege deconstructie’ - en weer terug. Voor de globalistische vijandige elite zijn cis-gender blanke mannen een natuurlijke (voor ‘inherente’ lees ‘geboorte’) vijand: een vijandelijke (en dus ‘gepriviligeerde’) demografische categorie die zij ten koste van alles wil onderwerpen. Boven alles gaat het om macht (vijandelijke macht is ‘privilege’, eigen macht is ‘mensheidverbetering’); (2) ‘regering door beschermingsbehoeftige klassen’ = dictatuur van het feministisch-allochtone neo-proletariaat; (3) ‘maatschappelijk speelveld effenen’ = revolutionair nivelleren. Het echte doel van de globalistische vijandige elite is om alles te reduceren tot haar eigen existentiële niveau, dat wil zeggen het niveau van bruut materialisme, bestiaal hedonisme, idiocratisch anti-intellectualisme en rancuneuze lelijkheid. De globalistische vijandige elite richt zich niet op de transformatie straathoer>prinses maar op de transformatie prinses>straathoer: zij richt zich op het neerhalen van alles dat nog hoog, edel en mooi is in de wereld; (4) ‘Nieuwe Wereld Order’ = kosmologisch deconstructie. Uiteindelijk beogen alle ‘progressieve’ ideologieën van de historisch-materialistische variant (een categorie die socialisme, fascisme en liberalisme omvat) en alle ‘emancipatorische’ bewegingen van de revolutionaire variant hetzelfde doel: de nihilistische omverwerping van alle goddelijke wetten, alle menselijke wetten en alle natuurlijke wetten.

Most liberals are not Antifa (yet), but soon they will be. ‘De meeste liberalen behoren (nog) niet tot Antifa, maar zullen zich er snel bij aansluiten.’

(*) En hier hebben we dan de politieke sleutelzin van ‘Het Antifa Handboek’: hier wordt de vinger gelegd op het sleutel vraagstuk van de globalistische vijandige elite, namelijk de urgentie van een voortvarende ‘ideologie-transitie’, van het aflopende ‘festivistische’ neo-liberalisme[13] (preciezer: liberaal-normativisme) naar het opkomende totalitaire neo-fascisme. Als ‘het liberaal-normativisme de basis-ideologie is van de vijandige elite, dat wil zeggen de ideologie die haar greep op de macht legitimeert’,[14] dan is nu juist haar liberaal-normativistische discours haar Achilles hiel. In die zin kunnen de ‘Corona Crisis’ en de ‘BLM Crisis’ worden begrepen als softening up operaties waarmee de globalistische vijandelijke elite de inheems-Westerse volksmassa’s voorbereid op haar aanstaande ideologie-transitie naar een totaal-totalitaire anti-rechtstaat. Deze softening up wordt bewerkstelligd door een geraffineerde combinatie van behaviouralistische conditionering (traumasturing en gedragsdressuur), moderne technologie (algoritmische censuur en controle) en noodwetgeving (politiestaat en rechtswillekeur).[15]

[O]ur endgame... is the socialization of capital. ...Obviously, we start with healthcare. It’s after all, a basic human right. ...After healthcare, the next target... will obviously be the media. Use one of the government’s only tools against big corporations: anti-trust, anti-monopoly laws - to split the media into worker-owned... entities. ...After media, banks and finance will be our next target: ...if the workers owned and controlled their own businesses, everyone would win, except the big fat cat CEOs who would be out of a job. ‘Onze eindinzet... is de socialisatie van het kapitaal. ...Vanzelfsprekend begint dat bij de zorgsector, want medische zorg is een basaal mensenrecht. ...Na de zorgsector is de mediasector... het voor de hand liggende volgende doelwit. Hier kunnen wij één van de weinige middelen inzetten die de overheid heeft tegenover de grote corporaties: anti-trust en anti-monopolie wetgeving - zo kunnen we de media opsplitsen in kleinere eenheden die arbeiders in eigen bezit kunnen houden. ...Na de media zijn de banken en de financiële sector aan de beurt: ...als de arbeiders hun eigen zaken zouden controleren en bezitten, dan komt dat iedereen te goede - behalve de volgevreten directeuren en managers die dan hun positie verliezen.’

(*) En hier hebben we dan de psychologische angel van ‘Het Antifa Handboek’ te pakken: hier wordt verwezen naar de grootste onvervulde vraag op de Westerse politieke markt, namelijk de alles-overheersende vraag naar échte sociaal-economische rechtvaardigheid. Dit vraagstuk is relevant voor alle etnische groepen: het overschrijdt nu in bijna klassiek-marxistische zin alle etnische en raciale grenzen en daarmee heeft Antifa een zowel politieke als activistische ‘marktwaarde’ die slim wordt uitgebuit door de globalistische vijandige elite. Er heerst ook in de blanke onder- en middenklasse en - vooralsnog grotendeels latent maar exponentieel stijgende - onvrede met de huidige neo-liberale dispensatie: men heeft genoeg van de zich eindeloos herhalende ‘bezuinigingsmaatregelen’ en ‘arbeidsmarkt hervormingen’ die de Westerse volksmassa’s langzaam maar zeker hebben doen verzinken in neo-victoriaanse arbeidsomstandigheden en neo-primitieve leefomstandigheden. Aldus hebben Antifa en BLM een groot ‘woede reservoir’ - nu ook nog gevoed door de willekeurige en alom gehate Corona maatregelen - waaruit zij naar believen kunnen putten. Als Nieuw Rechts het vraagstuk van authentieke sociaal-economische rechtvaardigheid laat liggen dan zal het zijn geloofwaardigheid verliezen - en laat zij een unieke activistische en politieke kans liggen. Laat Nieuw Rechts zich herinneren dat het ooit ver boven ‘links-rechts’ tweespalt stond: Nieuw Rechts (in het Frans en het Engels duidelijker in de woorden droit en right) staat boven al voor (diep) Recht - Recht in de zin van Carl Schmitt’s Nomos.[16] Nieuw Rechts staat voor authentieke sociaal-economische gerechtigheid: voor een herstel van sociaal evenwicht door een sterke dosis sociaal-economische hervormingen. Nieuw Rechts is meer dan nationalisme, maar alleen doordat het nationalisme incorporeert in sociaal-economisch beleid. Nieuw Rechts is ook meer dan (staats-)socialisme, maar alleen als het sociaal-economisch beleid combineert met nationalisme. Zogenaamd ‘linkse’ punten zoals ‘identiteitspolitiek’, ‘sociale rechtvaardigheid’ en ‘milieubewustzijn’ zijn eigenlijk kernpunten van Nieuw Rechts - ze worden holistisch gecombineerd in klassieke Nieuw Rechtse concepten als etnische zelfbeschikking, sociaal-economisch corporatisme en diepte-ecologie.[17] Nieuw Rechts doet er goed aan te bedenken dat de Westerse volksmassa’s kansen zoeken om hun sociaal-economische verhaal te halen op de globalistische vijandige elite. Wanneer de economische prijs van de Corona Crisis eenmaal inzinkt dan zullen zij dat verhaal eerder vinden bij de Antifa/BLM gepromote neo-communistische revolutie van morgen dan bij de alt-lite/neo-con ‘populistische’ oppositie van vandaag - deze oppositie biedt slechts hetzelfde neo-liberale business-as-usual refrein als het zittende partijkartel. De geloofwaardigheid van Nieuw Rechts staat op het spel: zij valt en staat met een principiële verdedigingskring rondom de Westerse volkeren - één verdedigingsector opgeven betekent dat de ringverdediging faalt. Nieuw Rechts kan het zich compromissen met het globalisme eenvoudigweg niet veroorloven: noch populistische ‘klimaatscepsis’, noch neo-con ‘civiel nationalisme’, noch neo-randiaans ‘libertarianisme’ - dit zijn definitief gepasseerde stations. Nieuw Rechts kan zich nu het hele anti-liberale discours toe-eigenen - en zo het tapijt wegtrekken onder de Social Justice Warrior marionetten van Antifa en BLM. Nieuw Rechts kan daarmee twee essentiële engagementen herbevestigen: sociaal-economische rechtvaardigheid en nationaal-corporatieve solidariteit - beide zijn onmisbare ingrediënten voor het breken van de Antifa/BLM golf. Nieuw Rechts kan de aankomende strijd niet winnen tenzij het aan de juiste zijde van de geschiedenis staat - en de geschiedenis van het Westen wordt nu geschreven. Het is vijf minuten voor twaalf.

Independence Day’ [18]

(psycho-politiek frontverlloop - RE: President Donald Trump)

We’re fighting for our right to live, to exist

and should we win the day,

the 4th of July will no longer be known as an American holiday,

but as the day when we declared in one voice:

we will not go quietly into the night

we will not vanish without a fight

‘Wij vechten voor ons recht te leven, te bestaan

en mochten wij vandaag overwinnen

dan zal de 4e juli niet langer slechts een Amerikaanse feestdag zijn

dan zal het als de dag herinnerd worden dat wij met één stem verklaarden:

wij zullen niet vredig in de nacht verdwijnen

wij zullen niet ondergaan zonder onze dag op het slagveld’

- ‘Independence Day’

‘Er is een groeiend gevaar dat nu alles bedreigt waarvoor onze voorvaderen zo hard hebben gevochten, hebben gestreden en hebben gebloed. Onze natie is nu ooggetuige van een genadeloze campagne die gericht is op het uitwissen van onze geschiedenis, het besmeuren van onze helden, het wegvlakken van onze waarden en het indoctrineren van onze kinderen. Woedende meutes proberen standbeelden van de stichters [van onze republiek] neer te halen, onze heiligste monumenten te onteren en een golf van gewelddadige misdaad in onze steden te ontketenen. De meeste van deze mensen beseft niet waar ze mee bezig zijn, maar sommige van hen weten precies wat ze aan het doen zijn. Zij denken dat het Amerikaanse volk zwak en zacht en onderdanig is. Maar zo is het niet: het Amerikaanse volk is sterk en trots en zal niet toelaten dat ons land, onze waarden, onze geschiedenis en onze cultuur ons worden afgenomen.’

‘Eén van hun politieke wapens is de ‘annulering cultuur’ die mensen arbeid ontzegt, opponenten beschaamt en totale onderwerping eist van iedereen die anders denkt. Dit is de precieze definitie van een totalitair systeem en het is volledig vreemd aan onze cultuur en onze waarden - het heeft enkele plaats in de Verenigde Staten van Amerika. Deze aanval op onze vrijheid, onze magnifieke vrijheid, moet worden gestopt - en zal zeer snel gestopt worden. Wij zullen deze gevaarlijke beweging aan het licht brengen, de kinderen van onze natie beschermen, deze radicale aanslag verijdelen en onze geliefde Amerikaanse levenswijze behouden. In onze scholen, onze nieuws studio’s, zelfs onze zakelijke directiekamers, bestaat nu een nieuw extreem-links fascisme dat absolute trouw eist. Iedereen die de juiste taal niet spreekt, de juiste rituelen niet volgt, de juiste mantra’s niet opleest en de juiste geboden niet opvolgt wordt gecensureerd, verbannen, afgeserveerd, vervolgd en bestraft. ...We moeten ons niet in deze vijand vergissen: deze linkse culturele revolutie beoogt de omverwerping van de Amerikaanse Revolutie. Daarmee zou zij een hele beschaving teniet doen - een beschaving die miljarden mensen van armoede, ziekte, geweld en honger heeft gered en die de mensheid naar nieuwe hoogten van prestatie, ontwikkeling en vooruitgang heeft getild. Om dit te bereiken zijn zij bereid elk standbeeld, elk symbool en elke herinnering aan ons nationale erfgoed neer te halen.’ - President Donald Trump, Mount Rushmore speech 4 juli 2020.

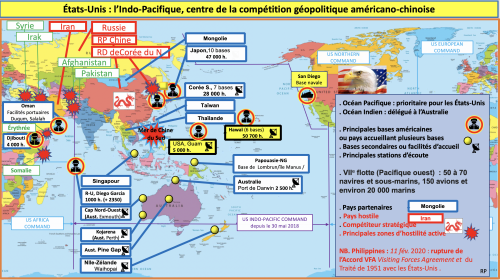

‘Saco di Roma’

(Geo-politieke uitwerkingen)

The Revolution was effected before the war commenced.

The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people...

This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments, and affections of

the people was the real American Revolution.

‘De revolutie voltrok zich vóór de oorlog begon.

De revolutie voltrok zich in de geest en het hart van het volk...

In deze radicale omslag in de principes, meningen, gevoelens en genegenheden van

het volk lag de échte Amerikaanse Revolutie’

- John Adams

(*) Independence Day Redux: ‘De [Independence Day] feestdag van 4 juli zou niet bestaan zoals hij nu bestaat zonder Francis Scott Key. Key was een jurist en een dichter - hij was degene die de tekst van het Amerikaanse volklied schreef. ...Toen hij... tijdens de oorlog van 1812... de Amerikaanse vlag nog steeds zag waaien over... Fort Henry... schreef hij de tekst die nu bekend staat als The Star-Spangled Banner. ...Ruim twee eeuwen later zijn [BLM en Antifa] terroristen bezig... Key’s standbeeld in het Golden Gate Park neer te halen. Misschien is de tijd gekomen voor de blanke bevolking van Amerika om een nieuwe identiteit aan te nemen. Als Amerika ons niet langer vertegenwoordigt en ons niet langer beschermt, waarom zouden wij dan nog loyaal moeten zijn aan Amerika, of onszelf als Amerikanen moeten identificeren? ...Misschien zal de Verenigde Staten van Amerika ‘Balkaniseren’ en zich oplossen in verschillende naties. Misschien kunnen blanke mensen naar gebieden verhuizen waar ze gemeenschappen, buurten en ondernemingen kunnen vorm samen met ander blank-positieve mensen. Misschien kunnen bepaalde Europese landen zelfs terugkeer programma’s aanbieden aan mensen met voorouders die uit die landen kwamen. Dit zijn slechts een paar verschillende ideeën voor mensen in verschillende situaties. Maar wat onze eigen situatie ook moge zijn, de tijd is gekomen voor blanke mensen om hun onafhankelijkheid uit te roepen - onafhankelijkheid van de alles onderdrukkende tirannie van de anti-blanke Verenigde Staten van Amerika. ...Soms zeggen mensen mij dat ik altijd “gewoon een Amerikaan” zal blijven, [maar] zouden zij hetzelfde zeggen tegen mensen die ooit in de Sovjet-Unie of Joegoslavië woonden? Blijven die mensen voor altijd Sovjetburger of Joegoslaaf? Nee. Die onderdrukkende regimes mogen een stempel hebben gezet op hun leven, maar zij hebben niet langer die identiteit. ...En net als alle andere grootrijken die té groot en te divers werden zal ook Amerika uiteindelijk in brand vliegen en ten onder gaan. Misschien dat blanke Amerikanen in staat zijn om uit de overgebleven as een maatschappij te herbouwen die bij hen past. ...Een nieuw land dat toegewijd is aan de bescherming van ons blanke volk - en aan de toekomst van onze blanke kinderen. ...Laat in het land der vrijen en het huis der dapperen[19] de vrijheid herleven - de vrijheid om te kiezen voor etnische soevereiniteit en blanke solidariteit.’ - ‘Fullmoon Ancestry’[20]

(*) De plutocratische revolutionairen op appel: ‘[Wat] is de rol van het [grote multinationale] zakenleven bij deze [BLM] gebeurtenissen? Vele grote firma’s haasten zich om de rellen te ondersteunen - en zelfs om plunderaars en opstandelingen te steunen tegen de regering. Onder de vele grote bedrijven die openlijk hun steun voor BLM en Antifa hebben uitgesproken zijn de volgende grote namen: The [Oscar-uitreikende] Academy, Airbnb, Adidas, Amazon (dezelfde firma die de altijd Trump-kritische New York Times in eigendom heeft), American Airlines, American Express, Bank of America, Bayer, BMW, BP, Booking.com, Burger King, Cadillac, Citigroup, Coca Cola, DHL Express, Disney, eBay, General Motors, Goldman Sachs, Google, H&M, IBM, Levi’s, Lexus, LinkedIn, Mastercard, McAfee, McDonald’s, Microsoft, Netflix, Nike, Paramount Pictures, Pepsi Co, Pfizer Inc, Porsche, Procter & Gamble, Society Generale US, Sony, Starbucks, Twitter, Uber, Verizon, Walmart, Warner Bros, YouTube en Zara. Een totaal van rond de drie honderd grote bedrijven en organisaties zijn bekend. Dit is een karakteristiek symptoom van de globalisatie-nieuwe-stijl, waarin trans-nationaal opererende bedrijven zich sterk en rijk genoeg voelen om tegen regeringen op te staan - ook al doen ze dat met indirect middelen. De bestuurders van deze vele firma’s vergeten echter een belangrijke les van de geschiedenis, namelijk dat de vele kapitalisten die ooit revoluties en coups financierden steeds onmiddellijk uit hun macht werden ontzet zodra de revolutionaire hen niet langer nodig hadden.’ - Leonid Savin[21]

(*) Terug naar de Onzichtbare Hand:[22] ‘Het is zinloos om [onze steden] te heroveren als [niemand] nog wil dat [ze deel] blijven van een gezond en redelijk gedefinieerde Amerikaanse beschaving. Laat ze maar afbranden. ...Laten Links en het linkse stemvee maar de consequenties dragen voor de onafgebroken serie politieke blunders en foute beslissingen die zij hebben gemaakt gedurende de laatste decennia. Als zij de politie haten, laten wij dan sympathiek zijn - en geen politie sturen. ...Detroit ziet er nu erger uit dan Hirosjima - en er was geen onplezierige ontmoeting met Enola Gay voor nodig om het zover te laten komen. Voor Nagasaki wilde Japan al niet meer sterven. Wij moeten even weinig nostalgie voelen voor Los Angeles. President Trump kan simpelweg de Zwarte Oehoeroe[23] afkondigen in al dat soort steden en hij kan daar dan ‘vrijheid’ laten neervallen, als zwavel en vuur op deze post-moderne versies van Sodom en Gomorra. ...Laat deze hippe, snoezige linkse hipsters zich maar uitleven. Laat hen hun eigen doctrines maar eens écht voelen - en ruiken - in al hun fantastische glorie. Laat hen hun ideologische pretentie maar opeten en inslikken, twee weken nadat de laatste supermarkt is geplunderd en neergebrand. Dan zullen ze om vrede smeken - maar dan zullen ze er geen meer kennen. De beste manier om de stedelijke rellen te beëindigen is om ze simpelweg uit te laten woeden - totdat de ammunitie op is en er niets meer is om te verbranden. ...Tot die tijd: #NoWarInAmerika - pak je popcorn en frisdrank en geniet van het vlammenspel.’ - Jonathan Peter Wilkinson[24]

‘De morele uitputting van het Westen’

(psycho-historische conditioneringen - RE: Frank Furedi[25])

Every species can smell its own extinction. The last ones left won’t have a pretty time of it. And in ten years, maybe less, [our species] will be just a bedtime story for their children–a myth, nothing more. ‘Elke soort kan haar eigen uitsterven bespeuren. De laatst-overgeblevenen zullen geen prettige tijd beleven. Tien jaar van nu, misschien eerder, zal [ons soort] nog slechts een sprookje voor het slapengaan zijn voor hun kinderen - niet meer dan een mythe.’ - ‘In the Mouth of Madness’ (John Carpenter, 1994)

(*) De oorsprong van de “Cultuur Oorlog”: ‘Ontkoppeld van de geschiedenis aan het einde van de Eerste Wereld Oorlog had de Westerse maatschappij grote moeite om een overtuigend narratief neer te zetten waarmee zij haar culturele erfgoed kon overdragen aan nieuwe generaties. Het resultaat was een fenomeen dat tegenwoordig bekend staat als de “generatie kloof”. Deze kloof ontstond na de Eerste Wereld Oorlog echter niet zozeer omdat er sprake was van een kloof tussen generaties: er was sprake van een culturele kloof, dat wil zeggen een kloof tussen de cultuur van voor de oorlog en die van na de oorlog. In de volgende decennia werd de spanning tussen “cultuur generaties” steeds meer ervaren een probleem van identiteit. ...Eén van de redenen waarom de Westerse bestuurselites niet in staat waren om hun verlies van morele autoriteit [met een nieuw narratief] te ondervangen was dat zij moesten erkennen dat hun eigen levenswijze [en waardesysteem] door verval van binnenuit niet langer levensvatbaar waren. Gedurende de jaren ’40 en ’50 waren zelfs conservatieve denker niet in staat de volle implicaties te overzien van het probleem waarmee hun traditie zich geconfronteerd zag.[26] ...De achteloze manier waarop vervolgens in de jaren ’60 traditionele taboes werden doorbroken liet aan de traditioneel-georiënteerde volksmassa zien dat traditionele waarden niet langer de boventoon voerden. ...Deze uitputting van moraal kapitaal werd bewezen door de stormachtige opkomst van de ‘tegencultuur’ [van de jaren ’60 en ‘70]... Sinds de jaren ’70 zijn de vertegenwoordigers van traditionele [Westerse waarden] steeds in de verdediging geweest. In plaat van het poneren van debatpunten en het bepalen van de debatagenda hebben zij zich beperkt tot reageren - steeds schieten zij in de verdediging om steeds weer nieuwe aanvallen op hun levenswijze te pareren. Deze cyclus van defensieve reacties komt terug in een lange serie vraagstukken, van het “homo huwelijk” en “trans-gender rechten” tot “wit privilege”...’

(*) De “Cultuur Omslag” voorbij: ‘De huidige fase van de Cultuur Oorlog begon in de jaren ’70. Het was in die jaren dat de traditionele Westerse elites de strijd tegen de in de jaren ’60 opgekomen “tegencultuur” stilletjes opgaven. Tegen het einde van de jaren ’70 beheersten de waarden van de “tegencultuur” de cultuur: ze waren geïnstitutionaliseerd, eerst in het schoolonderwijs en de cultuursector, en daarna in andere maatschappelijke sectoren. Sommige analisten karakteriseren deze ontwikkeling als de “Cultuur Omslag”. In de late jaren ’70 werd deze Cultuur Omslag toegeschreven aan een “nieuwe klasse” in de culturele elite, een klasse die zich verbond aan zogenaamd... postmateriële waarden. ...Deze nieuwe klasse legde zich toe op postmateriële behoeften, zoals de behoefte aan esthetische bevrediging, en op wat psychologen “zelfrealisatie” noemen... De leden [van deze nieuwe klasse]... begonnen therapeutische zelfhulp groepen... en raakten in toenemende mate geobsedeerd met identiteitsvraagstukken... Van meet af aan werden hun postmateriële behoeften echter niet neutraal gepresenteerd, niet als één van vele mogelijke waardesystemen. Eerder was het zo dat deze behoeften door hun voorsprekers werden gezien als [intrinsiek] superieur aan traditionele waarden zoals patriottisme, nationalisme en respect voor autoriteit...’

(*) De matriarchale revolutie: ‘De Cultuur Omslag marginaliseerde alle traditionele waarden. Meestal werd dit bereikt door een “mars door de instituties” die het socialisatie-proces bepalen. ...Met nieuwe klasse van intellectuelen en kenniswerkers bereikte de postmateriële elite als snel een monopolie-positie in de instituties van de onderwijs- en wetenschapsector, waar ze de Culturele Omslag promoten en toewerkten naar de deconstructie van traditionele culturele waarden. ...Deze ontwikkeling werd gefaciliteerd door grote veranderingen in het Westerse familieleven. In de context van stijgende welvaart verzwakten de tweelingkrachten van de vrouwenemancipatie en onderwijsdemocratisering alle vormen van patriarchale autoriteit. Dit verlaagde de capaciteit van het prevalerende socialisatiesysteem, dat tot dan toe gebaseerd was geweest op de familie: [de culturele reproductie begon te haperen en] historische waarden werden niet langer op nieuwe generaties overgedragen. ...[Er is een direct] verband tussen de verstoorde socialisatie in de familiesfeer en de intensivering van de Cultuur Oorlog...’

(*) Politisering en polarisatie: ‘[Velen] dachten dat de [Cultuur Omslag] beweging van traditionele waarden naar postmateriële waarden een positief proces was omdat het de invloed van hebzuchtig materialisme binnen de maatschappij zou verminderen. Maar de betekenis van de Cultuur Omslag lag niet zozeer in de zogenaamd postmateriële waarden die erdoor werden bevorderd, als wel in zijn [grotere] effect, namelijk de verdere politisering van cultuur en identiteit. ...De Cultuur Oorlog is niet slechts één politiek domein tussen vele anderen: het is geen conflict dat komt en gaat zoals de specifieke vraagstukken van “homo huwelijk” en Brexit. Eerder is het zo dat de Cultuur Oorlog nu het hele politiek bedrijf beheerst: het is de politiek... In zijn huidige stadium bestrijkt de Cultuur Oorlog vrijwel alle facetten van het dagelijks leven. De Cultuur Oorlog heeft een weergaloze polarisatie veroorzaakt in bereiken die ooit totaal apolitiek waren. Dat is de reden dat nu bijna alles, van het voedsel dat men eet tot de kleding die men draagt, onderwerp van zure discussie kan worden. Conflicten over waarden hebben een enorm belang gekregen in het politieke leven. Recente debatpunten, zoals abortus, euthanasie, immigratie, “homo huwelijk”, trans-gender voornaamwoorden, “witheid” en familieleven, laten zien dat er geen consensus [meer] bestaat over de meest fundamentele vraagstukken binnen [onze] maatschappij. De strijd tegen normen en waarden heeft het politieke bedrijf diep gepolariseerd. Zelfs ooit strikt persoonlijke zaken, zoals de keuze met wie men seksuele relaties heeft, worden nu als politieke stellingnamen gezien...’

(*) De Oorlog tegen het Westen: ‘[Begin jaren ’80] was de “tegencultuur” beweging geïnstitutionaliseerd: haar vertegenwoordigers domineerden niet alleen de instituties in de cultuur sector en in het hogere onderwijs, maar ook die in de publieke sector. Sinds die tijd zijn ook de zakenwereld en de private sector onder haar heerschappij gekomen. Sinds zij de hegemonie verwierven zijn de leden van het “tegenculturele” establishment steeds minder geworden om hun waarden op te leggen aan de rest van de maatschappij. Vanuit hun perspectief is [de Britse premier] Boris Johnson feitelijk niet meer dan een elite dissident en is zijn verdediging van Churchill [gedurende de BLM rellen] herinnert hen eraan dat er nog steeds obstakels bestaan tegen hun project van het losmaken van de maatschappij van de geschiedenis. Nu zijn zij het culturele establishment en zijn degenen die standbeelden van Churchill... of Lincoln willen verdedigen op hun beurt de “tegencultuur” tegenstanders van het nieuwe establishment. Op dit moment is de Cultuur Oorlog [nog steeds] een zeer eenzijdig conflict dat zich vooral richt op een [passief], defensief traditionalistisch doelwit. ...Sinds de jaren ’70 heeft de politisering van de cultuur de [voorheen] machtige ideologieën van het moderne tijdvak effectief vervangen, of tenminste getransformeerd. Binnen scholen en universiteiten zijn conservatieve en [zelfs] klassiek-liberale ideeën nu volkomen gemarginaliseerd - zelfs basale noties zoals tolerantie en democratie zijn aan het vervagen. In de grote culturele instituties [van het Westen], van de kunsten tot aan de media, worden humanistische waarden en idealen nu geassocieerd met de [zogenaamd “verouderde”] Westerse Traditie die loop van de Klassiek-Griekse filosofie tot de Renaissance en de Verlichting. Zelfs klassiek-socialistische noties als solidariteit en internationalisme zijn weggevaagd door de politisering van cultuur en identiteit. Deze ontwikkelingen vinden plaats binnen een eenzijdige oorlog tegen de geschiedenis in het algemeen en Westers erfgoed in het bijzonder. Degenen die het belang van tradities en historische continuïteit nog hoog houden lijken nu altijd in de verdediging te zijn. Meer nog: zij lijken zich er bij neer te leggen dat zij de strijd om de ziel van de samenleving hebben verloren... Deze atmosfeer van defaitisme is begrijpelijk. Degenen die principieel staan voor de grote prestaties die de [Westerse] beschaving heeft geleverd voor de mensheid hebben namelijk een eindeloze serie van nederlagen geleden gedurende de afgelopen decennia...’

(*) De Oorlog tegen de Blankheid: ‘Rond de eeuwwisseling waren Westerse onderwijsinstituties, en met name universiteiten, niet langer bezig met onderwijs. Zij waren meer bezig met her-scholing en her-socialisatie. Vooral in de Verenigde Staten wordt van nieuwe studenten nu verwacht dat zij aan allerlei workshops deelnemen waarin op “bewustwording” wordt aangestuurd met betrekking tot specifieke vraagstukken. “Bewustwording” kan daarbij het best worden begrepen als een eufemisme voor de bekering van individuele studenten tot de persoonlijk waardesystemen van de “bewustmakers”. Campus “bewustwording” initiatieven beogen de deelnemers deugden en morele kwaliteiten bij te brengen die hen zogenaamd onderscheiden van zogenaamd “onbewuste” en “onverlichte” individuen. De populaire aansporing om “wit privilege” te (h)erkennen is een belangrijk voorbeeld van dit “bewustwording” model. Zij die een bekentenis en biecht afleggen onderscheiden zich van zogenaamd enggeestige en bevooroordeelde mensen die dat niet doen. Het hebben van “bewustzijn” wordt zo een teken van superieure status - het niet-hebben is een teken van [morele] minderwaardigheid. Dat is waarom de weigering om de aansporing tot “bewustwording” op te volgen resulteert in verontwaardiging en veroordeling...’

(*) De contouren van de cultuur-nihilistische eindoverwinning: ‘Bijna ongemerkt zijn de morele waarden die mensen ooit hielpen om goed en kwaad te onderscheiden verdwenen: ...[die waarden] hebben geen invloed meer op gedrag en besluitvorming in de publieke sfeer. In [Westerse] universiteiten wordt de taal van moraliteit nu zelfs aangevallen als bedrog, of als een discours dat moet worden gedeconstrueerd en aan de kaak moet worden gesteld... Het basale vermogen goed van kwaad te onderscheiden is zwaar beschadigd door de “tegenculturele” devaluatie van alle soorten grenzen: de grenzen tussen goed en kwaad, tussen kind en volwassene, tussen man en vrouw, tussen mens en dier, tussen privésfeer en publieke sfeer. Al deze symbolische grenzen zijn de afgelopen jaren systematisch in twijfel getrokken. Zo wordt bijvoorbeeld de basale tegenstelling tussen man en vrouw aangevallen als “transfoob”. Zelfs het concept van binaire oppositie wordt gezien als anti-inclusief en discriminerend... Het belangrijkste verlies van deze oorlog tegen traditionele [ideeën en] idealen is het verlies van de status van het morele oordeel. ...[Dit totale] verlies van geloof in elk moreel oordeel laat zien hoe ver de strijd voor het behoud van basale beschavingswaarden is verloren... In het huidige tijdsgewricht wordt elk moreel oordeel - dat wil zeggen elke poging goed en kwaad te onderscheiden - gezien als verdacht, discriminerend en bevooroordeeld. In plaats daarvan overheerst nu de tegen-ethiek van het anti-oordeel: de-judgement heerst.’

‘De-Judge New Speak’

(neo-theologisch perspectief - RE: Allan Stevo[27])

Systemen van beelden, concepten van onuitgesproken oordelen, verschillend geordend in verschillende sociale klassen; systemen in beweging en daarom studieobject voor de geschiedschrijving, maar niet altijd gelijktijdig bewegend in verschillende cultuurlagen - systemen die het gedrag van mensen bepalen zonder dat zij zich er rekeningschap van geven. - Georges Duby

(*) Omgekeerde zondeleer: ‘De moderne feministische beweging schrijft binnen de menselijke verhoudingen de erfzonde toe aan de man: dit wordt tegenwoordig populair omschreven met “privilege”. Anders dan de [oude Christelijke] erfzonde is dit [nieuwe post-Christelijke] oerzonde niet digitaal en niet binair, maar analoog en gradueel. Als de man ook nog blank is, dan is zijn erfzonde nog groter. Er bestaan namelijk allerlei soorten privileges. Hoe minder geprivilegieerd men is, hoe hoger men als mens staat. Alle individueel geprivilegieerden moeten hun erfzonden publiek bekennen en naar zo nederig mogelijk het collectieve gelijk opzoeken. Hoe meer privilege men heeft, hoe meer men de biecht behoeft. Hoe minder privilege men heeft, hoe minder biechten wordt verwacht.’

(*) Omgekeerde verlossing: ‘Er bestaat [in de nieuwe De-Judge religie] geen verlossing. Iedereen kan te allen tijde worden geconfronteerd met het eigen privilege en daarop worden aangevallen door het hele collectief tegelijk. Met genoeg training elke offensieve referentie naar privilege genoeg om een tegenwerkend individu op te zadelen met een verlammend schuldcomplex. De priesters van deze [nieuwe De-Judge] religie geven geen absolutie van zonde: zij leggen zich exclusief toe op boetedoening en (zelf)kastijding. En zo zijn de geprivilegieerde aanhangers van deze religie feitelijk permanente martelaren die nooit, noch door goede werken noch door priesterlijk absolutie, kunnen worden verlost.’

(*) Omgekeerde katholiciteit: ‘Alleen mensen die via schuld en boete kunnen worden bewogen tot acceptatie van hun eigen privilege zijn zondig. Niet-boetvaardige mensen zullen fanatiek worden vervolgd, maar hun weigering tot publieke boetedoening beschermt hen toch tegen de ergste veroordeling die deze nieuwe religie kent. De zondaar moet zelf zijn rol als zondaar accepteren. Elke vorm van publieke verontschuldiging maakt iemand een zondaar binnen deze sociale rechtvaardigheid beweging. Boetedoening en excuses zijn daarom bij uitstek masochistische daden. Eenmaal een zondaar, blijft men een zondaar. Zo komt het dat een publieke verontschuldiging een vorm van doop wordt; deze doop is niet gericht op reiniging, maar stelt de gedoopte juist bloot aan herhaalde verontreiniging. Deze doop moet daarom steeds weer herhaald worden in een constant rollenspel dat uit is op vernedering en straf in plaats van spijt en boetedoening. Er bestaat geen manier om oprecht spijt te betuigen in deze religie en er bestaat ook geen mogelijkheid om verlost te worden.’

(*) Omgekeerde uitverkiezing: ‘Geboorte met de grootste opsomming van onderdrukkingskenmerken bestempelt iemand tot uitverkorene. Het vermogen een eigen narratief van het eigen slachtofferschap te creëren is een teken van hogere genade. Toch bestaat er geen pad naar verlossing: er bestaat alleen een tijdelijke status als uitverkorene - gedurende die tijd wordt men nog steeds door sommigen als een zondaar en door sommige als een heilige beschouwd, maar met meer van het tweede dan van het eerste. Men verliest de uitverkorene status zodra de proporties zich omkeren.’

(*) Omgekeerde goddelijkheid: ‘De smaak-van-de-maand trend die populair is binnen het collectief heeft de rol van het goddelijke beginsel. De rol van het goddelijke beweegt dus van groep naar groep en van tijd tot tijd. Goddelijke status geeft almacht en alziendheid, maar is zo tijdelijk dat men er vaak maar een paar dagen gebruik van kan maken.’

(*) Omgekeerde verlossingsleer: ‘Er bestaat geen Jezus. Er bestaat geen Messias. Er bestaat geen verlossing. Er is geen eindpunt. De sociale rechtvaardigheid beweging is een duivelse schepping die de hel op de aarde vestigt. Niemand kan ooit ontsnappen aan het hamster wiel waarop je altijd wordt achtervolgd door een monster. Uiteindelijk wordt iedereen neergesabeld. De uitverkoren social justice warrior van vandaag is verdoemde van morgen. Uiteindelijk is iedereen is verdoemd, maar de meest geprivilegieerde mensen vallen sneller in de verdoemenis. Er bestaat in die logica wel een bepaalde rechtvaardigheid: uiteindelijk valt iedereen in de verdoemenis, maar de diepste cirkel van deze hel is voorbehouden aan de meest geprivilegieerde mensen.’

(*) Omgekeerde demonologie: ‘Degenen die weigeren de schuld van hun privilege op zich te nemen worden gelijkgesteld met de duivel - dat wordt ook uitgedrukt in het etiket “letterlijk Hitler” of soortgelijk [aan het fascisme-nazisme gebonden] ketterij vocabulaire. Weigering privilege te erkennen en zich daarvoor in zelfvernedering te excuseren is de walgelijkst denkbare houding.’

(*) Omgekeerde profetie: ‘Alleen mensen die zich persoonlijk identificeren met een thema kunnen over dit thema spreken. Het idee dat een heteroseksuele blanke man een waardevolle mening zou kunnen hebben over racisme, abortus, homoseksualiteit en armoede is verboden. Wanneer men met mensen met minder privilege spreekt dient men zichzelf te censureren - in die situatie zijn alleen uitspraken van zelf-beschuldiging en zelf-vernedering toegestaan.’

(*) Omgekeerde orthodoxie: ‘Het Concilie van Nicea is permanent in vergadering - meestal op de sociale media. Waar zich twee of drie mensen verenigen om over sociale rechtvaardigheid te spreken, daar vindt ook het Concilie van Nicea plaats ter verwezenlijken van een nieuw dogma. De tijdelijkheid van dat nieuwe dogma doet niet af aan het gewicht en de strengheid van de uitvoering ervan - feitelijk verhoogt die tijdelijkheid de passie, de eindinzet en de extreemheid van het dogma.’

(*) Omgekeerd priesterschap: ‘De meest onderdrukte persoon kan op elk mogelijk moment tot hogepriester worden verheven. Rollen kunnen snel wisselen, al naar gelang de conjunctuur van collectieve modes en individuele grillen. De rol van god en hogepriester kunnen soms samenvallen in één persoon.’

(*) Omgekeerde autoriteit: ‘Het meest hypocriete lid van de groep dient te spreken met de luidste stem. De luidste stem is genoeg om dat groepslid de macht te geven om anderen te veroordelen.’

(*) Nieuwe geloofsartikelen: ‘Diversiteit is een onaanvechtbaar en onontkoombaar dogma. Diversiteit moet echter steeds zeer krap en zeer onduidelijk worden gedefinieerd. Zo is leeftijd diversiteit relatief onwenselijk omdat dan ook oudere en wijzere mensen zouden mogen meepraten. Raciale diversiteit is ook onwenselijk omdat dat de deur opent naar blanke mensen. Er bestaat geen acceptabel minimum getal aan blanke gesprekspartners hoger dan nul. Diversiteit in denken is alle helemaal uit den Boze. Diversiteit is het belangrijkste geloofsartikel van deze nieuwe religie.’

(*) Nieuw hiernamaals: ‘Wanneer eenmaal alle geprivilegieerde mensen zijn verdwenen, dan zal de wereld een betere plaats zijn. Wanneer eenmaal alle duivels en Hitlers zijn overwonnen, dan zal de wereld een betere plaats zijn. Deze constant wisselende definities maken het realiseren van de betere wereld moeilijk, maar dat weerhoudt niemand ervan zich met passie in deze religie te werpen. Alhoewel blanken de duidelijkst geprivilegieerde groep zijn, laat de mogelijkheid om nieuwe privileges te ontdekken een voortbestaan van deze religie toe, ook na de uitroeiing van alle blanken.’

(*) Nieuwe heilige boeken: ‘De Bijbel is eeuwenoud. Social justice warriors kunnen niets met dingen die de tand des tijds hebben doorstaan. Alleen sterke gevoelens en extreme gedragingen ingegeven door die sterke gevoelens dwingen nog respect af. Extreme kledij - bijvoorbeeld een Moslim vrouw die zich volledig bedekt - geldt als een imposant teken dat hogere status verleent. Zeldzame etniciteit - bijvoorbeeld een volbloed Amer-Indiaanse etniciteit - geeft ook hogere status. Maar die etniciteit hoeft niet eens authentiek te zijn: het is genoeg dat men een claim legt op die identiteit, ook als die niet echt is. Des te emotioneler dit wordt uitgedragen, des te meer kans maakt men op hogere religieuze status. ...Ervaringsdeskundigheid is in het algemeen van beperkte waarde. Hetzelfde geldt voor het aanhalen van logica en ervaring in gesprek met anderen: dit geeft risico op beschuldigingen van splaining (van explaining, “uitleggen”), of zelfs man-splaining (“mannelijk uitleggen”) - een zwaar vergrijp. Ervaring wordt afgedaan als van weinig waarde, zoals blijkt uit populaire frases als “OK boomer” die worden gebruikt om ervaring te ondermijnen - dit is een legitieme strategie omdat zo personen tot zwijgen kunnen worden gebracht die ervaring door privilege hebben kunnen opdoen.’

(*) Nieuwe schriftgeleerden: ‘Des te meer woke men is, des te meer invloed men heeft. Dit zijn de nieuwe farizeeën: de woke zijn niet alleen het tempelpersoneel van deze nieuwe religie, zij zijn tevens de meest succesvol-hypocriete mensen van het moment.’

(*) Nieuwe priesterkledij: ‘Piercings en gekleurd haar zijn tekenen van een echte volger van deze nieuwe religie.’

(*) Nieuwe deugden: ‘Het hoogst-aangeschreven goede werk van deze nieuwe religie is luidruchtigheid. Het effectief verweven van privilege in een aanval op anderen resulteert in de meest effectieve hermeneutiek. Logica komt na gevoel - en ligt ver achter. Logica resulteert in ongewenste verstoring van de voortvarende uitvoering van religieuze voorschriften en is daarom niet welkom.’

(*) Nieuwe wonderen: ‘Gewoon bankbiljetten drukken om de rekeningen te betalen - en gewoon nullen toevoegen. Werken is/zijn in deze nieuwe religie niet langer van belang. Er bestaat geen dag van economische gramschap. Manna valt uit de hemel en alles is gratis.’

(*) Nieuwe naam: ‘Hoewel deze nieuwe religie geen officiële naam heeft kan men haar aanduiden met de titel Democratic Judgment (“Democratisch Oordeel”) - De-Judge in het kort. Deze naam brengt haar alles-nivellerende meute-mentaliteit en snelle veroordeling instinct tot uitdrukking, evenals haar belangrijke rol in virtue signalling (“deug pronken”) en haar dogmatisch onvermogen tot rechtvaardig oordelen. De-Judge heeft de democratisch-totalitaire toekomst.’

‘Het laatste kwartier van het Westen’

(macro-historisch perspectief)

Een juist begrip van de ‘Corona Crisis’ en ‘BLM Crisis’ golven vergt een macro-historisch perspectief: een dergelijk perspectief laat zien dat deze golven niet slechts middelen zijn die globalistische vijandige elite kan gebruiken voor de versnelde deconstructie van de Westerse beschaving - het zijn tegelijk ook typische ‘eindtijd’ symptomen in de beschavingscyclus van het Westen. Voor een juist begrip van de dubbel opzettelijke en onvermijdelijke aard van deze vernietigende golven - door Oswald Spengler als ‘evolutionair’ proces geduid via zijn ‘pseudo-morphose’ analyse - is het nuttig ze te bezien vanuit het Traditionalistische concept van de Cyclische Tijd. Voor lezers die minder bekend zijn met dit concept zal de schrijver van dit opstel hier een kleine passage uit zijn boek Sunset vertalen: ‘In modern-wetenschappelijke termen kan het Traditionalistische concept van de Cyclische Tijd worden opgevat als een “werkhypothese”, dat wil zeggen een theoretisch model om bepaalde fenomenen te beschrijven en begrijpen. Afhankelijk van de precieze onderzoek parameters kan deze “werkhypothese” meer of minder, juist of onjuist blijken voor specifieke historische fenomenen. In modern-wetenschappelijke termen is het Traditionalistische concept van de Cyclische Tijd het meest relevant voor macro-historisch onderzoek. In de loop van de laat-moderne tijd (hier gedefinieerd als het tijdvak 1920-1992) herkende een aantal historici duidelijke tekenen van culturele decadentie en beschavingsverval in het Westen en zij interpreteerden die tekenen als symptomen van een grotere cyclus van historische ontwikkeling. Spengler werd langzaam maar zeker gevolgd door andere historici in zijn idee van de “Ondergang van het Avondland” - een idee waarin hij het postulaat verweeft van een universeel-toepasselijk model van macro-historische cyclische ontwikkeling. Toynbee werkte dit idee van de op handen - of eigenlijk gaande - zijnde ondergang van de Westerse beschaving uit door het te relateren aan de innerlijke degeneratie van haar creatieve elite. Beide these zijn historiografisch waardevol want daarmee ontstaat een macro-historisch perspectief. Het Traditionalisme vergt echter een nog hoger perspectief om de neergang van het Westen accuraat te duiden, namelijk een meta-historisch perspectief. Spengler’s werk baseert zich op de universele notie van een gefaseerde ontwikkelingsgang binnen alle culturen, die uiteindelijk functioneren als super-organismen met een - bij benadering - voorspelbare levenscyclus. Toybee’s werk is gebaseerd op een soortgelijke notie van “beschavingscycli”. Zowel Spengler als Toynbee herkende in gestructureerde patronen van cultuur-historische symptomen de kenmerken van een cyclische ontwikkelingsgang. In de modern-wetenschappelijke geschiedschrijving komen hun macro-historische analyses het dichtst in de buurt van een Traditionalistische interpretatie van de geschiedenis van de Moderniteit. Toch wagen zij zich aan de doelstelling van wat het Traditionalisme aanduidt als essentiële, met een hoofdletter geschreven Geschiedenis - zij wagen zich niet aan de vanuit Traditionalisch perspectief enig nuttige doel van die Geschiedenis: hogere betekenis. Voordat de moderne, met een kleine letter geschreven geschiedschrijving ooit kan fuseren met de Traditionalistische, met hoofdletter geschreven Geschiedenis in een hogere (“archeo-futuristische”) synthese zullen de perspectieven van traditionele geschiedschrijving moeten worden geïncorporeerd in de moderne geschiedschrijving. Hoe meer men te weten komt over de mythen, legenden en godsdiensten van de mensheid, hoe dringender de noodzaak om ze op één of andere wijze als geheel te begrijpen. Hun verschillende stemmen, onderlinge tegenstrijdigheden en onverenigbare dogma’s vereisen de sterke hand van een strenge scheidsrechter die zin en eenheid geeft aan het geheel.[28] Een systematische studie van de menselijke geschiedenis op grond van revolutionaire filosofisch-epistemologische principes, zoals synchroniciteit en retro-causaliteit, kan bijdrage tot een toekomstige synthese van de modern-wetenschappelijke seculiere geschiedenis en de Traditionalistische Heilige Geschiedenis.’[29] Deze overwegingen geven de lezer een indruk in welke hoek een archeo-futuristische geschiedschrijving moet worden gezocht. Uiteindelijk kan het doel van een dergelijk revolutionair-nieuwe geschiedschrijving niet minder zijn dan een macro-historisch perspectief op de micro-historische plaats van de geschiedenis-student, met andere woorden de concrete betekenis van de geschiedenis voor elk individu. Deze betekenis staat gelijk aan toegang to de hoogste vorm van de oude kunst van de geschiedschrijving: meta-geschiedenis.

‘Agora’[30]

(meta-historische perspectieven)

Oorlogen zijn ethische geschillen

- ze worden in de tempels gewonnen voordat ze ooit worden gestreden

- Sun Tzu, volgens ‘JFK’

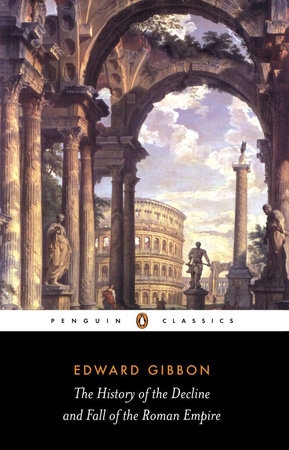

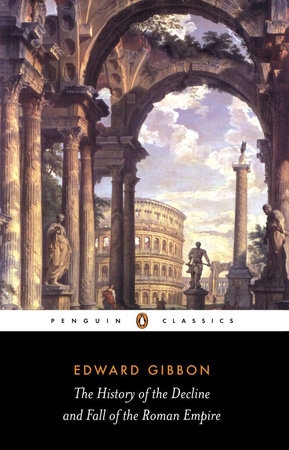

Beginnend met Edward Gibbons, die zijn meerdelige werk Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (‘Verval en Val van het Romeinse Rijk’) schreef tussen de grote omwentelingen van de Amerikaanse en Franse Revolutie, hebben sommige van de grootste Westerse historici geprobeerd de enigmatische ‘wetmatigheden’ en ‘patronen’ te reconstrueren die de levenscyclus lijken te bepalen van alle menselijke beschavingen. Met het verstrijken van de tijd en de toenemende ‘idiocratisering’ van het Westerse onderwijs- en media-systeem zijn Westerse lezers echter steeds minder in staat het basale uitgangspunt van deze schrijvers na te volgen, namelijk hun vermogen de verschuiving te volgen in de transcendente referentiepunten die de beschavingscyclus bepalen. Dit vermogen, in schrijver zowel als lezer, is logischerwijs een functie van hun eigen relatie tot de transcendente sfeer - en wordt dus noodzakelijkerwijs in de weg gestaan door elke belangrijke verstoring in de grotere relatie die hun eigen maatschappij heeft tot diezelfde sfeer.

Beginnend met Edward Gibbons, die zijn meerdelige werk Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (‘Verval en Val van het Romeinse Rijk’) schreef tussen de grote omwentelingen van de Amerikaanse en Franse Revolutie, hebben sommige van de grootste Westerse historici geprobeerd de enigmatische ‘wetmatigheden’ en ‘patronen’ te reconstrueren die de levenscyclus lijken te bepalen van alle menselijke beschavingen. Met het verstrijken van de tijd en de toenemende ‘idiocratisering’ van het Westerse onderwijs- en media-systeem zijn Westerse lezers echter steeds minder in staat het basale uitgangspunt van deze schrijvers na te volgen, namelijk hun vermogen de verschuiving te volgen in de transcendente referentiepunten die de beschavingscyclus bepalen. Dit vermogen, in schrijver zowel als lezer, is logischerwijs een functie van hun eigen relatie tot de transcendente sfeer - en wordt dus noodzakelijkerwijs in de weg gestaan door elke belangrijke verstoring in de grotere relatie die hun eigen maatschappij heeft tot diezelfde sfeer.

In dit verband is er een belangrijke vraag die zich nu aandient voor Westerse mensen: wat is het transcendente referentiepunt in onze Agora, in de grote publieke debatruimte en de ‘marktplaats van ideeën’ in het hart van onze publieke sfeer? Het antwoord is met de ‘BLM Crisis’ gegeven: onze Agora is nu gesloten, zelfs in letterlijke zin - door de quarantaine maatregelen van ‘Corona’ en door de occupy movement nieuwe stijl van ‘BLM’. De heiligdommen (waaronder kerken) worden gesloten en de standbeelden (waaronder van ‘vaderen des vaderlands’) van onze Agora worden omvergeworpen. Toegang tot onze Agora is nu gesloten voor zelfs onze meest gematigde en redelijke van onze publieke sprekers: de recente YouTube ban van een publiek spreker als Stefan Molyneux bewijst wel definitief deze uitsluiting nu is. Na het ‘vrije meningsuiting’ beginsel, dat eeuwenlang de ‘agoristische’ fabrieksinstelling van het Westerse sociaal-politiek leven was, verdwijnt nu de Westerse Agora zelf uit beeld. Om een historische parallel te vinden met een omwenteling van deze reikwijdte moeten wij terug naar de laatste fase van de Klassieke Oudheid: daar kunnen wij onderzoek doen naar het gecompliceerde maar onloochenbare verband tussen superstructuur en infrastructuur, in casu het verband tussen de val van het Romeinse Rijk en de val van het Grieks-Romeinse polytheïsme. De val van het Grieks-Romeinse heidendom en de val van het Westerse Christendom zijn niet hetzelfde en kunnen niet hetzelfde resultaat hebben, maar beide zijn wel onlosmakelijk verbonden met - of onderdeel van - de val van de beschavingen die waren ontstaan rondom hun wereldbeeld.

|

Late Oudheid (‘Val van het Romeinse Rijk)

|

Late Moderniteit (‘Val van het Westen)

|

|

Constantijn I 306-337 Christendom gelegaliseerd

312 Chi-Rho Christelijk symbool op militaire standaard

313 Edict van Milaan: Christendom gedoogd

325 Concilie van Nicea: de facto staatskerk

330 Constantinopel Christelijke als hoofdstad gewijd

|

Wereld Oorlogen 1914-1945 globalisme triomfeert

1920 Volkerenbond: proto-globalistische instituties

1922 Sovjet-Unie: proto-globalistische staat

1941 Atlantisch Handvest: globalisch programmatuur

1945 Verenigde Naties: globalistische instituties

|

|

Constantius II 337-361 anti-heidense wetgeving

353 verbod op rituele offers

357 Victoria Altaar eerstmaals verwijderd

|

Naoorlogse jaren ‘deconstructie’ van het Christendom

1961/65 Vahanian/Altizer ‘God is dood’ theology 1962-66 Tweede Vaticaans Concilie

|

|

Julianus 361-363 laat-heidense restoratie, syncretisme

362 Tolerantie Edict: vrijheid/gelijkheid van godsdienst

|

Jaren ‘60 Counter Culture, laat-Christelijk syncretisme

1968 Amerikaanse Civil Rights Act

|

|

Gratianus 367-383, Valentinianus II 375-392 (Westen);

Theodosius I 379-392 (Oosten)

verbod en vervolging van het heidendom

378 Slag bij Adrianopel: Romeinse militaire ondergang

380 Edict Thessaloniki: Christendom staatsgodsdienst

382 Victoria Altaar opnieuw verwijderd

390 vernietiging van de Tempel van Delphi

391 vernietiging Serapeum van Alexandrië

393 einde Mysteriën Eleusis & Olympische Spelen

394 einde Eeuwige Vuur & Vestaalse Maagden

|

Thatcher-Major, Reagan-Bush-Clinton 1979-2001 (Westen); Yeltsin 1991-1999 (Oosten)

globalo-liberale aanval op het Christelijke Westen

1986 Challenger & Chernobyl rampen

1989 val Berlijnse Muur: globalo-liberale NWO

1992 Fukuyama’s ‘einde der geschiedenis’

2001 9/11, Amerikaanse Patriot Act

2002 world wide web totaalbereid, digitale pornificatie

2010 laatste gedrukte Encyclopaedia Britannica

2013 zelfmoord Dominique Venner

|

|

Theodosius I 392-395 laatste keizer van verenigd rijk:

395 finale deling Romeinse Rijk

|

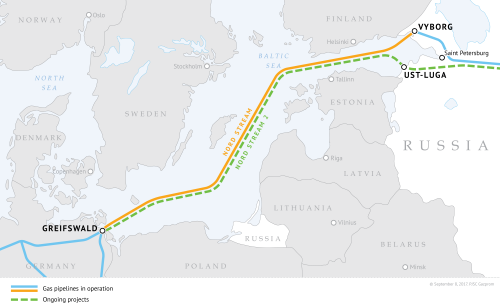

Oost-West splitsing, Nieuwe Koude Oorlog:

2004 EU/NAVO expansie

|

|

406 overtocht over de Rijn: barbaarse invasie

407 Romeinse militaire evacuatie Brittannië

408 moord op de ‘laastste Romeinse generaal’, Stilicho,

gevolgd door West-Gothische invasie, gevolgd door

410 Eerste Val van Rome