Ce faisant, il va être mêlé à une fabuleuse page de l’histoire antique se déroulant en 480 avant notre ère, pendant l’invasion de la Grèce par le roi de Perse Xerxès, fils de Darius: la bataille du défilé des Thermopyles.

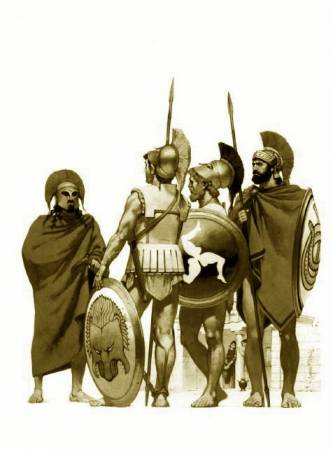

Six jours durant, sous le regard des dieux, cet étroit passage sera le théâtre de combats sans merci, lors de laquelle trois cents spartiates et quatre mille combattants grecs d’autres cités vont opposer une résistance farouche aux armées de l’empire perse.

Celles-ci rassemblant, selon l’historien Hérodote, deux millions d’hommes, traversèrent l’Hellespont, c’est-à-dire l’actuel détroit des Dardanelles, afin d’envahir et asservir la Grèce. Racontée par un survivant, c’est ce choc inégal – et, au-delà, toute l’histoire et la vie quotidienne de Sparte – que fait revivre Steven Pressfield dans ce roman traversé par «un formidable souffle d’authenticité».

L’objectif n’est pas seulement de rappeler cette page guerrière de l’histoire mais également de porter un regard sur la Grèce Antique, les Cités grecques et leur indépendance les unes par rapport aux autres, qui conduisait d’ailleurs celles-ci à se livrer des guerres incessantes.

Ainsi, nous apprenons les règles de vie très strictes et martiales de la Cité spartiate. La vie des hommes et des femmes n’était réglée que par rapport à l’organisation militaire et à la guerre, du moins en ce qui concerne ceux qui étaient considérés comme les Citoyens. Il n’y a apparemment aucun doute sur l’importance de cette Cité à cette époque et l’exemple qu’elle pouvait donner au reste du monde antique.

L’auteur a pris comme trame la vie d’un jeune homme qui ne pouvait prétendre devenir l’un de ces guerriers spartiates mais qui en revanche les a servis et approchés de près. Cette astuce permet à l’auteur de nous livrer à la fois une vision extérieure et une vision intérieure sur la philosophie martiale animant cette Cité, dressant ainsi un portrait saisissant, fruit d’une érudition certaine et d’une recherche documentaire approfondie.

La bataille du défilé des Thermopyles étant une glorieuse page de l’histoire de la Grèce (les trois cents spartiates étant morts jusqu’au dernier), cela donne au roman un souffle épique indéniable. En effet, trois cents Spartiates et leurs alliés y retinrent les envahisseurs pendant six jours. Puis, leurs armes brisées, décimés, ils furent contraints de se battre “avec leurs dents et leurs mains nues“, selon Hérodote, avant d’être enfin vaincus.

Les Spartiates et leurs alliés béotiens de Thespies moururent jusqu’au dernier, mais le modèle de courage que constitua leur sacrifice incita les Grecs à s’ unir. Au printemps et à l’automne de cette année-là, leur coalition défit les Perses à Salamine et à Platée. Ainsi furent préservées les ébauches de la démocratie et de la liberté occidentale.

Deux mémoriaux se dressent aujourd’hui aux Thermopyles. L’un, moderne, appelé “monument à Léonidas”, en l’honneur du roi spartiate qui mourut là, porte gravée sa réponse à Xerxes qui lui ordonnait de déposer les armes. Réponse laconique : Molon labe (“viens les prendre”).

L’autre, ancien, est une simple stèle qui porte également gravée les paroles du poète Simonide :

Passant, va dire aux Spartiates

Que nous gisons ici pour obéir à leurs lois.

Hérodote écrit dans ses Histoires : “Tout le corps des spartiates et des Thespiens fit preuve d’un courage extraordinaire, mais le plus brave de tous fut de l’avis général le Spartiate Dienekès. On rapporte que, à la veille de la bataille, un habitant de Trachis lui déclara que les archers perses étaient si nombreux que, lorsqu’ils décrochaient leurs flèches, le soleil en était obscurci. “Bien, répondit Dienekès, nous nous battrons donc à l’ombre.”

«On finit ce livre essoufflé d’avoir combattu au coude à coude. C’est ce que j’appelle un roman homérique.» – Pat Conroy

Extrait 1: Le contraire de la peur (Trouvé sur le blog de notre lecteur Boreas)

Tandis que les autres chasseurs festoyaient autour de leurs feux, Dienekès fit place à ses côtés à Alexandros et Ariston et les pria de s’asseoir. Je devinai son intention. Il allait leur parler de la peur. Car il savait qu’en dépit de leur réserve, ces jeunes gens sans expérience de la bataille se rongeaient à la perspective des épreuves prochaines.

Tandis que les autres chasseurs festoyaient autour de leurs feux, Dienekès fit place à ses côtés à Alexandros et Ariston et les pria de s’asseoir. Je devinai son intention. Il allait leur parler de la peur. Car il savait qu’en dépit de leur réserve, ces jeunes gens sans expérience de la bataille se rongeaient à la perspective des épreuves prochaines.

— Toute ma vie, commença-t-il, une question m’a hanté : quel est le contraire de la peur ?

La viande de sanglier était prête, nous mourions de faim et l’on nous apporta nos portions. Suicide vint, portant des bols pour Dienekès, Alexandros, Ariston, lui même, le servant d’Ariston, Démade et moi. Il s’assit par terre, près de Dienekès. Deux chiens, qui connaissaient sa générosité notoire à leur égard, prirent place de part et d’autre de Suicide, attendant des reliefs.

— Lui donner le nom de manque de peur, aphobie, n’a pas de sens. Ce ne serait là qu’un mot, une thèse exprimée comme antithèse. Je veux savoir quel est vraiment le contraire de la peur, comme le jour est le contraire de la nuit et le ciel est l’opposé de la terre.

— Donc tu voudrais que ce fût un terme positif, dit Ariston.

— Exactement !

Dienekès hocha la tête et dévisagea les deux jeunes gens. L’écoutaient-ils ? Se souciaient-ils de ce qu’il disait ? S’intéressaient-ils vraiment comme lui à ce sujet ?

— Comment surmonte-t-on la peur de la mort, la plus élémentaire des peurs, celle qui circule dans notre sang comme dans tout être vivant, homme ou bête ?

Il montra les chiens qui encadraient Suicide.

— Les chiens en meute ont le courage d’attaquer un lion. Chaque animal connaît sa place. Il craint l’animal qui lui est supérieur et se fait craindre de son inférieur. C’est ainsi que nous, Spartiates, tenons en échec la peur de la mort : par la peur plus grande du déshonneur. Et de l’exclusion de la meute.

Suicide jeta deux morceaux aux chiens. Leurs mâchoires happèrent promptement la viande dans l’herbe, le plus fort des deux s’assurant le plus gros morceau. Dienekès eut un sourire sarcastique.

— Mais est-ce là du courage ? La peur du déshonneur n’est-elle pas essentiellement l’expression de la peur ?

Alexandros lui demanda ce qu’il cherchait.

— Quelque chose de plus noble. Une forme plus élevée du mystère. Pure. Infaillible.

Il déclara que pour toutes les autres questions, l’on pouvait interroger les dieux.

— Mais pas en matière de courage. Qu’est-ce qu’ils nous apprendraient ? Ils ne peuvent pas mourir. Leurs âmes ne sont pas, comme les nôtres, enfermées dans ceci, dit-il en indiquant son corps. L’atelier de la peur.

» Vous autres, les jeunes, reprit-il, vous vous imaginez qu’avec leur longue expérience de la guerre, les vétérans ont dominé la peur. Mais nous la ressentons aussi fortement que vous. Plus fortement, même, parce que nous en avons une expérience plus intime. Nous vivons avec la peur vingt-quatre heures par jour, dans nos tendons et dans nos os. Pas vrai, ami ?

Suicide eut un sourire entendu. Mon maître sourit aussi.

— Nous forgeons notre courage sur place. Nous en tirons la plus grande part de sentiments secondaires. La peur de déshonorer la cité, le roi, les héros de nos lignées. La peur de ne pas nous montrer dignes de nos femmes et de nos enfants, de nos frères, de nos compagnons d’armes. Je connais bien tous les trucs de la respiration et de la chanson. Je sais comment affronter mon ennemi et me convaincre qu’il a encore plus peur que moi. C’est possible. Mais la peur reste présente.

Il observa que ceux qui veulent dominer leur peur de la mort disent souvent que l’âme ne meurt pas avec le corps.

— Mais pour moi, ça ne veut rien dire. Ce sont des fables. D’autres, et surtout les Barbares, disent aussi que, lorsque nous mourons, nous allons au paradis. S’ils le croient vraiment, je me demande pourquoi ils n’abrègent pas leur voyage et ne se suicident pas sur-le-champ.

Alexandros demanda s’il y avait quelqu’un de la cité qui témoignait du vrai courage viril.

— Dans tout Sparte, c’est Polynice qui s’en approche le plus, répondit Dienekès. Mais je trouve que même son courage est imparfait. Il ne se bat pas par peur du déshonneur, mais par désir de gloire. C’est sans doute noble et moins bas, mais est-ce que c’est vraiment le courage ?

Ariston demanda alors si le vrai courage existait.

— Ce n’est pas une fiction, dit encore Dienekès avec force. Le vrai courage, je l’ai vu. Mon frère Iatroclès l’avait par moments. Quand cette grâce le possédait, j’en étais saisi. Elle rayonnait de façon sublime. Il se battait alors non comme un homme, mais comme un dieu. Léonidas a parfois aussi ce type de courage, mais pas Olympias. Ni moi, ni personne d’entre nous ici. Il sourit. Vous savez qui possède cette forme pure du courage plus que tout autre que j’aie connu ?

Personne ne lui répondit.

— Ma femme.

Et se tournant vers Alexandros :

— Et ta mère, Paraleia. Ça me semble significatif. Le courage supérieur réside, il me semble, dans ce qui est féminin.

On voyait que ça lui faisait du bien de parler de tout cela. Il remercia ses auditeurs de l’avoir écouté.

— Les Spartiates n’aiment pas ces analyses, poursuivit-il. Je me rappelle avoir demandé à mon frère, en campagne, un jour qu’il s’était battu comme un immortel, ce qu’il avait ressenti au fond de lui. Il m’a regardé comme si j’étais devenu fou. Et il m’a répondu : « Un peu moins de philosophie, Dienekès, et un peu plus d’ardeur. » Autant pour moi ! conclut Dienekès en riant.

Il détourna le visage, comme pour mettre un point final à ces considérations. Puis son regard revint à Ariston, dont le visage exprimait cette tension que les jeunes éprouvent quand il leur faut parler devant des aînés.

— Eh bien, parle donc, lui lança Dienekès.

— Je pensais au courage des femmes. Je crois qu’il est différent de celui des hommes. Il hésita. Son expression semblait dire qu’il craignait de paraître présomptueux à parler de choses dont il n’avait pas l’expérience. Mais Dienekès le pressa :

— De quelle façon différent ?

Ariston jeta un coup d’œil à Alexandros, qui l’encouragea à parler. Le jeune homme prit donc son souffle :

— Le courage de l’homme quand il donne sa vie pour son pays est grand, mais il n’est pas extraordinaire. Est-ce que ce n’est pas dans la nature des mâles, que ce soient des animaux ou des humains, de s’affronter et de se battre ? C’est ce que nous sommes nés pour faire, c’est dans notre sang. Regarde n’importe quel petit garçon. Avant même qu’il ait appris à parler, l’instinct le pousse à s’emparer du bâton et de l’épée, alors que ses sœurs répugnent à ces instruments de conflit et préfèrent prendre dans leur giron un petit chat ou une poupée.

Qu’est-ce qui est plus naturel pour un homme que de se battre et pour une femme, que d’aimer ? Est ce que ce n’est pas l’injonction physique de la femme que de donner et de nourrir, surtout quand il s’agit du fruit de ses entrailles, ces enfants qu’elle a accouchés dans la douleur ? Nous savons tous qu’une lionne ou une louve risquera sa vie sans hésiter pour sauver ses rejetons. Les femmes agissent de même. Alors, observez ce que nous appelons le courage des femmes.

Il reprit son haleine.

— Qu’est-ce qui pourrait être le plus contraire à la nature d’une femme et d’une mère que de regarder froidement ses fils aller à la mort ? Est-ce que toutes les fibres de son corps ne crient pas leur souffrance et leur révolte dans cette épreuve ? Est-ce que son cœur ne crie pas : non ! Pas mon fils ! Épargnez-le ! Le fait que les femmes arrivent à rassembler assez de courage pour faire taire leur nature la plus profonde est la raison pour laquelle nous admirons nos mères, nos sœurs et nos femmes. C’est cela, je crois, Dienekès, l’essence du courage féminin et la raison pour laquelle il est supérieur au courage masculin.

Mon maître hocha la tête. Mais Alexandros s’agita. On voyait qu’il n’était pas satisfait.

— Ce que tu as dit est vrai, Ariston. Je n’y avais jamais pensé. Mais il faut dire ceci. Si la supériorité des femmes tenait à ce qu’elles sont capables de rester impassibles quand leurs fils vont à la mort, cela en soi-même ne serait pas seulement contre nature, ce serait aussi grotesque et même monstrueux. Ce qui prête de la noblesse à leur comportement est qu’elles agissent ainsi au nom d’une cause plus élevée et désintéressée.

Ces femmes que nous admirons donnent les vies de leurs fils à leur pays, afin que leur nation puisse survivre, même si leurs fils périssent. Nous avons entendu depuis notre enfance l’histoire de cette mère qui, apprenant que ses cinq fils étaient morts à la guerre, a demandé : « Est-ce que nous avons gagné ? » Et, quand elle a appris que nous avions gagné, en effet, elle est retournée chez elle sans une larme et elle a dit : « Dans ce cas, je suis contente. » Est-ce que ce n’est pas cette noblesse-là qui nous émeut dans le sacrifice des femmes ?

Ces femmes que nous admirons donnent les vies de leurs fils à leur pays, afin que leur nation puisse survivre, même si leurs fils périssent. Nous avons entendu depuis notre enfance l’histoire de cette mère qui, apprenant que ses cinq fils étaient morts à la guerre, a demandé : « Est-ce que nous avons gagné ? » Et, quand elle a appris que nous avions gagné, en effet, elle est retournée chez elle sans une larme et elle a dit : « Dans ce cas, je suis contente. » Est-ce que ce n’est pas cette noblesse-là qui nous émeut dans le sacrifice des femmes ?

— Tant de sagesse dans la bouche de la jeunesse ! s’écria Dienekès en riant.

Il donna une tape sur les épaules des deux garçons, puis ajouta :

— Mais tu n’as pas répondu à ma question : qu’est-ce qui est le contraire de la peur ?

(…)

Je songeai au marchand éléphantin. Suicide était celui qui, dans tout le camp, s’était le plus attaché à ce personnage à l’humeur vive et gaie ; ils étaient rapidement devenus amis. À la veille de ma première bataille, tandis que le peloton de mon maître préparait le souper, ce marchand arriva. Il avait vendu tout ce qu’il avait et même sa charrette et son âne, même son manteau et ses sandales.

Et là, il circulait distribuant des poires et de petits gâteaux aux guerriers. Il s’arrêta près de notre feu. Mon maître procédait souvent le soir à un sacrifice ; pas grand-chose, un bout de pain et une libation ; sa prière était silencieuse, juste quelques paroles du fond de son cœur à l’intention des dieux. Il ne disait pas la teneur de sa prière, mais je la lisais sur ses lèvres ; il priait pour Aretê et ses filles.

— Ce sont ces jeunes hommes qui devraient prier avec autant de piété, observa le marchand, et pas vous, vétérans ronchonneurs.

Dienekès invita avec empressement le marchand à s’asseoir. Bias, qui était encore vivant, s’était moqué du manque de prévoyance du marchand ; comment s’échapperait-il, maintenant, sans charrette et sans âne ?

Éléphantin ne répondit pas.

— Notre ami ne s’en ira pas, dit doucement Dienekès, fixant le sol du regard.

Alexandros et Ariston étaient arrivés sur ces entrefaites avec un lièvre qu’ils avaient marchandé à des gamins d’Alpenoï. On se moqua de leur acquisition, un lièvre d’hiver si maigre qu’il nourrirait à peine deux hommes et certes pas seize. Le marchand sourit et regarda mon maître.

— Vous trouver, vous les vétérans, aux Murailles de Feu, c’est normal. Mais ces gamins, dit-il en indiquant d’un geste les servants et moi-même, qui sortions à peine de l’adolescence. Comment pourrais-je partir alors que ces enfants sont ici ? Je vous envie, reprit-il quand l’émotion dans sa voix se fut apaisée. J’ai cherché toute ma vie ce que vous possédez de naissance, l’appartenance à une noble cité.

Il montra les feux alentour et les jeunes et les vieux assis devant.

— Ceci sera ma cité. Je serai son magistrat et son médecin, le père de ses orphelins et son amuseur public.

Puis il nous donna ses poires et se leva pour aller à un autre feu, et encore un autre, et l’on entendait les rires qu’il déclenchait sur son passage.

Les Alliés étaient alors postés aux Portes depuis quatre jours. Ils avaient mesuré les forces perses sur terre et sur mer et ils savaient les dangers insurmontables qui les attendaient. Ce ne fut qu’alors que je pris conscience de la réalité du péril qui menaçait l’Hellade et ses défenseurs. Le coucher du soleil me trouva pensif.

Un long silence suivit le passage de l’éléphantin. Alexandros écorchait le lièvre et j’étais en train de moudre de l’orge. Médon bâtissait le feu sur le sol, Léon le Noir hachait des oignons, Bias et Léon Vit d’Âne étaient allongés contre un fût de chêne abattu pour son bois. À la surprise générale, Suicide prit la parole.

— Il y a dans mon pays une déesse qu’on appelle Na’an, dit-il. Ma mère en était la prêtresse, si l’on peut user d’un aussi grand mot pour une paysanne qui avait passé toute sa vie à l’arrière d’un chariot. J’y pense à cause de la charrette que ce marchand appelle sa maison.

On n’avait jamais entendu Suicide parler autant. Tout le monde croyait qu’il avait vidé là son sac. Et pourtant, il poursuivit. Sa prêtresse de mère lui avait appris que rien sous le soleil n’est réel ; que la terre et tout ce qu’il y a dessus n’étaient que des paravents, les matérialisations de réalités beaucoup plus profondes et plus belles au-delà, invisibles pour les mortels. Que tout ce que nous appelons réalité est animé par cette essence plus subtile, inévitable et indestructible.

— La religion de ma mère enseigne que seules sont réelles les choses qui ne peuvent pas être perçues par les sens. L’âme. L’amour maternel. Le courage. Ces choses sont plus proches des dieux parce qu’elles sont les mêmes des deux côtés de la mort, devant et derrière le rideau. Quand je suis arrivé à Lacédémone et que j’ai vu la phalange à l’exercice, j’ai pensé qu’elle pratiquait la forme de guerre la plus absurde que j’eusse vue.

Dans mon pays, nous nous battons à cheval. C’est la seule glorieuse manière de se battre, c’est un spectacle qui excite l’âme. Mais j’admirais les hommes de la phalange et leur courage, qui me semblait supérieur à celui de toutes les autres nations que j’avais vues. Ils étaient pour moi une énigme.

Mon maître écoutait avec attention ; il était évident que cette profusion de paroles de Suicide était pour lui aussi inattendue que pour tous les autres.

— Te rappelles-tu, Dienekès, quand nous nous battions contre les Thébains à Érythrée ? Quand ils ont flanché et pris la fuite ? C’était la première déroute à laquelle j’assistais. J’en étais horrifié. Existe-t-il quelque chose de plus bas, de plus dégradant sous le soleil qu’une phalange qui se désintègre de peur ? Cela donne honte d’être un mortel, d’être aussi ignoble en face de l’ennemi. Cela viole les lois suprêmes des dieux. Le visage de Suicide, qui n’avait été qu’une grimace de dédain, s’éclaira. Ah, mais à l’opposé, une ligne qui tient ! Qu’est-ce qui est plus beau, plus noble !

Je rêvai une nuit que je marchais avec la phalange, reprit Suicide. Nous avancions sur une plaine à la rencontre de l’ennemi. J’étais terrifié. Mes camarades marchaient autour de moi, devant, derrière, à droite et à gauche, et tous étaient moi. Moi vieux, moi jeune. J’étais encore plus terrifié, comme si je me désagrégeais.

Et puis ils se sont mis à chanter, tous ces moi, et, comme leurs voix s’élevaient dans une douce harmonie, la peur me quitta. Je me réveillai le cœur paisible et je sus que ce rêve venait des dieux. Je compris que c’était ce qui faisait la grandeur de la phalange, le ciment qui assurait sa cohésion. Je compris que cet entraînement et cette discipline que vous Spartiates aimez vous imposer, ne sert pas vraiment à enseigner la technique ou l’art de la guerre, mais à créer ce ciment.

Médon se mit à rire.

— Et quel ciment as-tu donc dilué, Suicide, qui fait qu’enfin tes mâchoires se desserrent avec une expansivité si peu scythe ?

Les flammes éclairèrent un sourire de Suicide. C’était, disait-on, Médon qui lui avait donné son surnom quand, coupable d’un meurtre dans son pays, le Scythe s’était enfui à Sparte et qu’il demandait à tout le monde de le tuer.

— Je n’aimais d’abord pas ce surnom. Mais avec le temps, j’en reconnus la profondeur, même si elle n’était pas intentionnelle. Car qu’est-ce qui est plus noble que de se tuer ? Pas littéralement, pas avec une épée dans le ventre, mais de tuer le moi égoïste à l’intérieur, cette partie de soi qui ne vise qu’à sa conservation, qui ne veut que sauver sa peau. C’est la victoire que vous, Spartiates, avez remportée sur vous-mêmes. C’était le ciment, c’était ce que vous aviez appris et qui m’a fait rester.

Léon le Noir avait écouté tout le discours du Scythe.

— Ce que tu dis, Suicide, si je peux t’appeler ainsi, est vrai, mais tout ce qui est invisible n’est pas noble. Les sentiments bas sont également invisibles. La peur, la cupidité et la lubricité. Qu’en fais-tu ?

— Oui, mais ils puent, ils rendent malade. Les choses nobles invisibles sont comme la musique dans laquelle les notes les plus hautes sont les plus belles. C’est une autre chose qui m’a étonné quand je suis arrivé à Sparte. Votre musique. Combien il y en avait, pas seulement les odes martiales et les chants de guerre que vous entonnez quand vous allez vers l’ennemi, mais également les danses, les chœurs, les festivals, les sacrifices. Pourquoi ces guerriers consommés honorent-ils la musique alors qu’ils interdisent le théâtre et l’art ? Je crois qu’ils sentent que les vertus sont comme la musique, elles vibrent sur des registres plus élevés, plus nobles.

Il se tourna vers Alexandros.

C’est pourquoi Léonidas t’a choisi parmi les Trois Cents, mon jeune maître, bien qu’il ait su que tu n’avais jamais fait partie des trompettes. Il croit que tu chanteras ici, aux Portes, dans ce sublime registre, pas avec ceci – et il indiqua la gorge – mais avec cela – et, de la main, il se toucha le cœur.

Puis il se ressaisit, soudain embarrassé. Autour du feu, tout le monde le regardait avec gravité et respect. Dienekès rompit le silence en disant, avec un rire :

— Tu es philosophe, Suicide.

— Oui, dit le Scythe en souriant, ouvre l’œil sur ça !

Un messager vint mander Dienekès au conseil que tenait Léonidas. Mon maître me fit signe de l’accompagner. Quelque chose avait changé en lui ; je le sentais à la manière dont nous traversions le réseau de sentiers qui s’entrecroisaient dans le camp des Alliés.

— Te rappelles-tu cette nuit, Xéon, où nous discutions avec Ariston et Alexandros de la peur et de son opposé ?

Je répondis que je me la rappelais.

— J’ai la réponse à ma question. Nos amis le marchand et le Scythe me l’ont soufflée.

Il parcourut du regard les feux du camp, les unités des nations assemblées et leurs officiers qui se dirigeaient vers le feu du roi, pour répondre à ses besoins et recevoir ses instructions.

— L’opposé de la peur, dit Dienekès, est l’amour.

Extrait 2: Qu’est-ce que la mort ?

Je me suis toujours demandé ce que c’était de mourir. Il y avait un exercice que nous pratiquions quand nous servions d’escorte et de souffre-douleur à l’infanterie lourde Spartiate. Cela s’appelait «le chêne», parce que nous prenions nos positions le long d’une rangée de chênes à la lisière de la plaine de l’Otona, où les Spartiates et les Néodamodes s’entraînaient l’automne et l’hiver.

Nous nous mettions en ligne par dix rangs, bardés sur toute notre hauteur de boucliers d’osier tressé, crantés dans la terre, et les troupes de choc venaient nous donner l’assaut ; elles arrivaient sur la plaine par huit rangs, d’abord au pas, puis plus rapidement et finalement en courant à perdre haleine.

Le choc de leurs boucliers tressés était destiné à nous épuiser et ils y parvenaient. C’était comme si l’on était heurté par une montagne. En dépit de nos efforts pour rester debout, nos genoux cédaient comme de jeunes arbres dans un tremblement de terre ; en un instant le courage désertait nos cœurs. Nous étions déracinés comme des épis morts sous la pelle du laboureur.

Et l’on apprenait alors ce qu’était mourir. L’arme qui m’a transpercé aux Thermopyles était une lance d’hoplite égyptien, qui pénétra sous le sternum de ma cage thoracique. Mais la sensation ne fut pas ce qu’on aurait cru, ce ne fut pas celle d’être transpercé, mais plutôt assommé, comme nous les apprentis, la chair à hacher, l’avions ressenti dans la chênaie.

J’avais imaginé que les morts s’en allaient dans le détachement. Qu’ils considéraient la vie d’un regard sage et froid. Mais l’expérience m’a démontré le contraire.

L’émotion dominait tout. Il me sembla qu’il ne restait plus rien que l’émotion. Mon cœur souffrit à se rompre, comme jamais auparavant dans ma vie. Le sentiment de perte m’envahit avec une puissance déchirante. J’ai revu ma femme et mes enfants, ma chère cousine Diomaque, celle que j’aimais. J’ai vu mon père Scamandride et ma mère Eunice, Bruxieus, Dekton et Suicide, des noms qui ne disent rien à Sa Majesté, mais qui pour moi étaient plus chers que la vie et qui, maintenant que je meurs, me deviennent encore plus chers.

Ils se sont éloignés. Et moi, je me suis éloigné d’eux.

Extrait 3: [Polynice, un des meilleurs commandants spartiates, interroge le jeune Alexandros]

- Tu voulais voir la guerre, reprit Polynice. Comment avais-tu imaginé que ce serait ?

Alexandros était requis de répondre avec une parfaite brièveté, à la spartiate. Devant le carnage, ses yeux avait été frappés d’horreur et son cœur d’affliction, lui dit-on ; mais alors, à quoi croyait-il que servait une lance ? Un bouclier ? Une épée ? Ces questions et d’autres lui furent posées sans cruauté ni sarcasme, ce qui eût été facile à endurer, mais de manière froide et rationnelle, exigeant une réponse concise.

Il fut prié de décrire les blessures que pouvaient causer une lance et le type de mort qui s’en suivrait. Une attaque de haut devait-elle viser la gorge ou la poitrine ? Si le tendon de l’ennemi était sectionné, fallait-il s’arrêter pour l’achever ou bien aller de l’avant ? Si l’on enfonçait une lance dans le pubis, au-dessus des testicules, fallait-il la retirer tout droit ou bien prolonger l’estocade vers le haut, pour éviscérer l’homme ? Alexandros rougit, sa voix trembla et se brisa.

- Veux-tu que nous nous interrompions, mon garçon ? Cette instruction est-elle trop rude pour toi? Réponds de manière brève. Peux-tu imaginer un monde où la guerre n’existe pas? Peux-tu espérer de la clémence d’un ennemi? Décris les conditions dans lesquelles Lacédémone se trouverait sans armée pour la défendre.

Qu’est-ce qui vaut mieux, la victoire ou la défaite? Gouverner ou être gouverné? Faire une veuve de l’épouse de l’ennemi ou bien de sa propre femme? Quelle est la suprême qualité d’un homme? Pourquoi? Qui admires-tu le plus dans toute la cité? Et pourquoi? Définis le mot « miséricorde ». Définis le mot « compassion ». Sont-ce là des vertus pour le temps de guerre ou le temps de paix? Sont-ce des vertus masculines ou féminines? Et sont-ce bien des vertus?

De tous les pairs qui harcelaient Alexandros ce soir-là, Polynice n’apparaissait guère comme le plus acharné ni comme le plus sévère. Ce n’était pas lui qui menait l’ arosis et ses questions n’était ni franchement cruelles, ni malicieuses. Il ne lui laissait tout simplement pas de répit.

Dans les voix des autres, aussi pressantes que fussent leurs questions, résonnait tacitement l’inclusion : Alexandros était l’un des leurs et ce qu’ils faisaient ce soir-là et feraient d’autres soirs ne visait pas à le décourager ni à l’écraser comme un esclave, mais à l’endurcir, à fortifier sa volonté, à le rendre plus digne d’être un jour appelé guerrier, comme eux, et à assumer son rang de pair et de Spartiate.

Extrait 4. [L'armée perse s'avance, pour le premier affrontement]

Léonidas avait maintes fois recommandé aux officiers thespiens de veiller à ce que les boucliers, les jambières et les casques de leurs hommes fussent aussi brillants que possible ; et là, c’était des miroirs. Par-dessus les bords des boucliers de bronze, les casques rutilaient, surmontés par des crinières de queue de cheval qui, lorsqu’elles frissonnaient au vent, ne créaient pas seulement une impression de haute taille, mais dégageaient aussi une indicible menace.

Ce qui ajoutait au spectacle terrifiant de la phalange hellénique et qui pour moi était le plus effrayant, c’étaient les masques sans expression des casques grecs, avec leurs nasales épaisses comme le pouce, les jugulaires écartées et les fentes sinistres des yeux, qui recouvraient tout le visage et donnaient à l’ennemi le sentiment qu’il affrontait, non pas des créatures de chair comme lui-même, mais quelque atroce machine, invulnérable, impitoyable.

J’en avais ri avec Alexandros moins de deux heures auparavant, quand il avait posé son casque sur son bonnet de feutre ; l’instant d’avant, avec le casque posé posé à l’arrière du crâne, il paraissait juvénile et charmant, et puis quand il eut rebattu la jugulaire et ajusté le masque, toute l’humanité du visage était partie. La douceur expressive des yeux avait été remplacée par deux insondables trous noirs dans les orbites de bronze. L’aspect du personnage avait changé. Plus de compassion. Rien que le masque aveugle du meurtre.

- Enlève-le ! Avais-je crié. Tu me fais peur !

Et je ne plaisantais pas.

Dienekès vérifiait à ce moment-là l’effet des armures hellènes sur l’ennemi. Il parcourait leurs rangs du regard. Les taches sombres de l’urine maculaient plus d’un pantalon, ça et là, les pointes de lances tremblaient. Les Mèdes se mirent en formation, les rangs trouvèrent leurs marques, les commandants prirent leurs postes.

Le temps s’étira encore. L’ennui le céda à l’angoisse. Les nerfs se tendirent. Le sang battait aux tempes. Les mains devinrent gourdes et les membres insensibles. Le corps sembla tripler de poids et se changer en pierre froide. On s’entendait implorer les dieux sans savoir si c’étaient des voix intérieures ou si on criait réellement et sans vergogne des prières.

Sa majesté se trouvait sans doute trop haut sur la montagne pour s’être avisée du coup du ciel qui précipita l’affrontement. Tout d’un coup, un lièvre dévala la montagne, passant entre les deux armées, à une trentaine de pieds de Xénocratide, le commandant thespien.

Steven Pressfield, Les murailles de feu, édité en mars 2007

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Agis was thus led to the execution chamber, and, according to Plutarch;

Agis was thus led to the execution chamber, and, according to Plutarch;

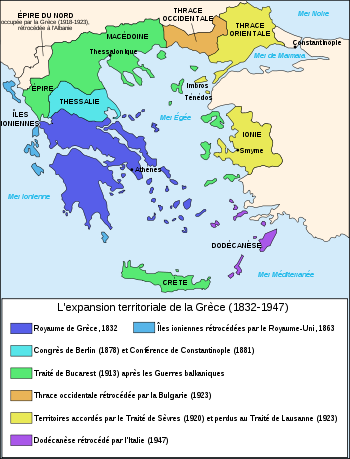

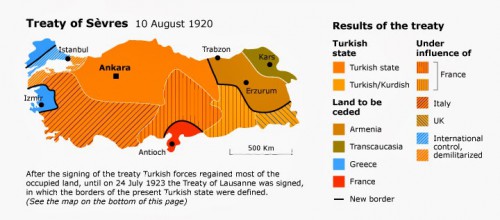

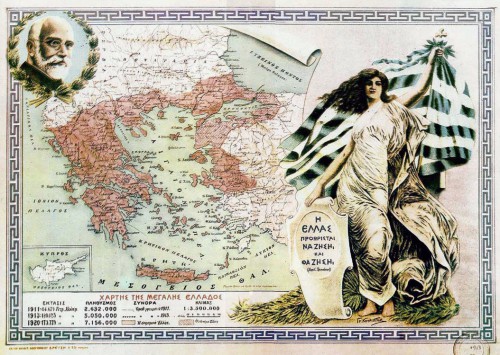

C'est sous son règne que le territoire national grec s'est agrandi: en 1864, il acquiertl es Iles Ioniennes avec Corfou; en 1881, il s'adjoint la Thessalie; en 1913, de vastes zones s'ajoutent au royaume au Nord et à l'Est. C'est là le résultat des guerres balkaniques, où le Prince Constantin, fort de sa formation militaire auprès de l'état-major général allemand, mène ses troupes à la victoire. Constantinople a vraiment été à portée de main…

C'est sous son règne que le territoire national grec s'est agrandi: en 1864, il acquiertl es Iles Ioniennes avec Corfou; en 1881, il s'adjoint la Thessalie; en 1913, de vastes zones s'ajoutent au royaume au Nord et à l'Est. C'est là le résultat des guerres balkaniques, où le Prince Constantin, fort de sa formation militaire auprès de l'état-major général allemand, mène ses troupes à la victoire. Constantinople a vraiment été à portée de main…

La suite attendue du film « 300 » de Zach Snyder, intitulée « l’Avènement d’un Empire » (Rise of an Empire), est récemment sortie sur nos écrans. A la musique, Tyler Bates a cédé la place à Junkie XL, qui nous propose une bande originale brillante, finissant en apothéose en mêlant son dernier morceau à une mélodie de Black Sabbath.

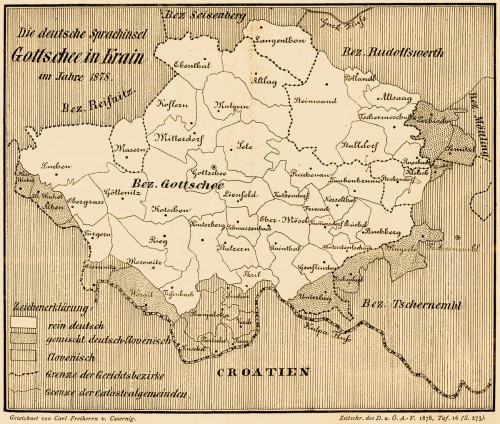

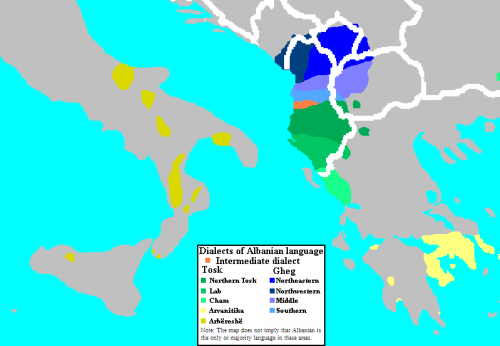

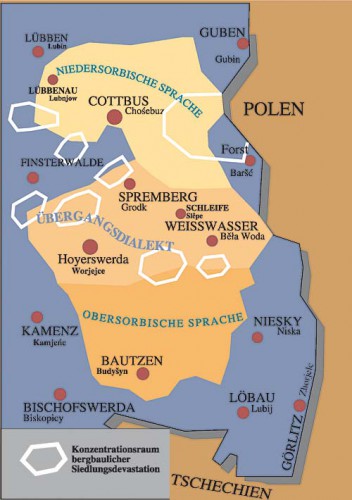

La suite attendue du film « 300 » de Zach Snyder, intitulée « l’Avènement d’un Empire » (Rise of an Empire), est récemment sortie sur nos écrans. A la musique, Tyler Bates a cédé la place à Junkie XL, qui nous propose une bande originale brillante, finissant en apothéose en mêlant son dernier morceau à une mélodie de Black Sabbath. Dans l’ABC politique qui nous est cher, déplorer avec anxiété la disparition des faits communautaires, des communautés humaines réelles, de chair et de sang, est une constante, couplée à une anthropologie pessimiste qui ne voit pas de “progrès” dans leur disparition mais qui constate, amèrement, que ce que l’on baptise “progrès” est en réalité une terrible “régression” dans la diversité humaine. Bon nombre d’ethnologues, d’écologistes, d’anthropologues déplorent, à très juste titre, la disparition de langues et de petites communautés ethniques dans la jungle d’Amazonie ou dans les coins les plus reculés de Bornéo ou de la Nouvelle-Guinée. Mais ce triste phénomène se passe en Europe aussi, sous l’oeil indifférent de toutes les canailles qui donnent le ton, qui détiennent les clefs du pouvoir politique et économique, qui n’ont aucune empathie pour les éléments humains constitutifs d’une réalité charnelle irremplaçable si elle venait à disparaître. Pour se rappeler que le phénomène de la “mort ethnique” n’est pas seulement d’Amazonie ou d’Insulinde, il suffit de mentionner la disparition des Kachoubes, des Polaques de l’Eau ou des derniers locuteurs de la vieille langue prussienne (du groupe des langues baltiques), suite à la seconde guerre mondiale.

Dans l’ABC politique qui nous est cher, déplorer avec anxiété la disparition des faits communautaires, des communautés humaines réelles, de chair et de sang, est une constante, couplée à une anthropologie pessimiste qui ne voit pas de “progrès” dans leur disparition mais qui constate, amèrement, que ce que l’on baptise “progrès” est en réalité une terrible “régression” dans la diversité humaine. Bon nombre d’ethnologues, d’écologistes, d’anthropologues déplorent, à très juste titre, la disparition de langues et de petites communautés ethniques dans la jungle d’Amazonie ou dans les coins les plus reculés de Bornéo ou de la Nouvelle-Guinée. Mais ce triste phénomène se passe en Europe aussi, sous l’oeil indifférent de toutes les canailles qui donnent le ton, qui détiennent les clefs du pouvoir politique et économique, qui n’ont aucune empathie pour les éléments humains constitutifs d’une réalité charnelle irremplaçable si elle venait à disparaître. Pour se rappeler que le phénomène de la “mort ethnique” n’est pas seulement d’Amazonie ou d’Insulinde, il suffit de mentionner la disparition des Kachoubes, des Polaques de l’Eau ou des derniers locuteurs de la vieille langue prussienne (du groupe des langues baltiques), suite à la seconde guerre mondiale.

En 805, les armées de Charlemagne s’ébranlent pour convertir les païens saxons et slaves (les “Wenden”), les inclure dans l’Empire franc afin qu’ils paient tribut. Seuls les Sorabes résistent et tiennent bon: de Magdebourg à Ratisbonne (Regensburg), l’Empereur est contraint d’élever le “limes sorbicus”. Assez rapidement toutefois, la tribu est absorbée par le puissant voisin et connaît des fortunes diverses pendant 1200 ans, sans perdre son identité, en dépit des progressistes libéraux du “Kulturkampf”, qui entendaient éradiquer la “culture réactionnaire” et des nationaux-socialistes qui suppriment en 1937 tout enseignement en sorabe et envisagent le déplacement à l’Est, en territoires exclusivement slaves, de cette “population wende résiduaire” (“Reste des Wendentums”).

En 805, les armées de Charlemagne s’ébranlent pour convertir les païens saxons et slaves (les “Wenden”), les inclure dans l’Empire franc afin qu’ils paient tribut. Seuls les Sorabes résistent et tiennent bon: de Magdebourg à Ratisbonne (Regensburg), l’Empereur est contraint d’élever le “limes sorbicus”. Assez rapidement toutefois, la tribu est absorbée par le puissant voisin et connaît des fortunes diverses pendant 1200 ans, sans perdre son identité, en dépit des progressistes libéraux du “Kulturkampf”, qui entendaient éradiquer la “culture réactionnaire” et des nationaux-socialistes qui suppriment en 1937 tout enseignement en sorabe et envisagent le déplacement à l’Est, en territoires exclusivement slaves, de cette “population wende résiduaire” (“Reste des Wendentums”).

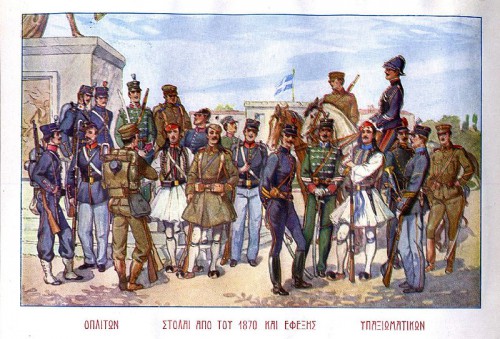

In contrast, Metaxas had no such concerns. His ideas were clear-cut from the early 1910s on and stamped on the Reservists Movement. These Reservists were people who had taken part in the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars, somewhat like the French anciens combattants. This Greek variety of the Far Right had, therefore, the following characteristics:

In contrast, Metaxas had no such concerns. His ideas were clear-cut from the early 1910s on and stamped on the Reservists Movement. These Reservists were people who had taken part in the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars, somewhat like the French anciens combattants. This Greek variety of the Far Right had, therefore, the following characteristics:

This story of materialistic ideas that were spread in the Balkans by the Greek Orthodox Church is a long (and very interesting) one. The roots are to be found in Byzantium itself. For from the eleventh century on, a revival of Platonism and neo-Platonism took place in Constantinople; and this revival led up to a kind of crypto-paganism. The 1453 capture of the Byzantine capital by the Ottomans put an end to this neo-platonic current; and Gennadius I Scholarius, the first Constantinopolitan Patriarch to be in office following the fall of the Byzantine Empire, directed the philosophical research of his flock towards the “beacon of Aristotle’s thought.” Still, this direction was to have very important consequences.

This story of materialistic ideas that were spread in the Balkans by the Greek Orthodox Church is a long (and very interesting) one. The roots are to be found in Byzantium itself. For from the eleventh century on, a revival of Platonism and neo-Platonism took place in Constantinople; and this revival led up to a kind of crypto-paganism. The 1453 capture of the Byzantine capital by the Ottomans put an end to this neo-platonic current; and Gennadius I Scholarius, the first Constantinopolitan Patriarch to be in office following the fall of the Byzantine Empire, directed the philosophical research of his flock towards the “beacon of Aristotle’s thought.” Still, this direction was to have very important consequences.

Beispielhaft entfaltet wird dies schon in Kondylis’ Dissertation über Die Entstehung der Dialektik (1979) bei Hölderlin, Schelling und Hegel und der damit zusammenhängenden Studie über Die Aufklärung im Rahmen des neuzeitlichen Rationalismus (1981), wo er zeigt, »wie sich ein systematisches Denken als Rationalisierung einer Grundhaltung und -entscheidung allmählich herauskristallisiert, und zwar im Bestreben, Gegenpositionen argumentativ zu besiegen«. Die Ausformung jener Dialektik, wie sie nach Hegel im Marxismus Ideologie einer weltgeschichtlich wirksamen Macht wurde, erweist sich als Teil eines konfliktreichen, schon im Spätmittelalter einsetzenden Prozesses der Ablösung von Weltbildern, in dem die formal-begrifflichen Strukturen der jeweils älteren Metaphysik stillschweigend übernommen und polemisch umgedeutet werden.

Beispielhaft entfaltet wird dies schon in Kondylis’ Dissertation über Die Entstehung der Dialektik (1979) bei Hölderlin, Schelling und Hegel und der damit zusammenhängenden Studie über Die Aufklärung im Rahmen des neuzeitlichen Rationalismus (1981), wo er zeigt, »wie sich ein systematisches Denken als Rationalisierung einer Grundhaltung und -entscheidung allmählich herauskristallisiert, und zwar im Bestreben, Gegenpositionen argumentativ zu besiegen«. Die Ausformung jener Dialektik, wie sie nach Hegel im Marxismus Ideologie einer weltgeschichtlich wirksamen Macht wurde, erweist sich als Teil eines konfliktreichen, schon im Spätmittelalter einsetzenden Prozesses der Ablösung von Weltbildern, in dem die formal-begrifflichen Strukturen der jeweils älteren Metaphysik stillschweigend übernommen und polemisch umgedeutet werden.

Just as Mussolini looked to Ancient Rome for the model of a healthy, organic society, the Ancient Romans looked to Sparta. In the first century (A.D.), as Rome continued its imperial ascent to near-hemispheric domination, the distance between the virtuous Republican nobility and the garish imperial nobility began to alert many to the potential for social degeneration. One of these was Plutarch, a Roman scholar of Greek birth.

Just as Mussolini looked to Ancient Rome for the model of a healthy, organic society, the Ancient Romans looked to Sparta. In the first century (A.D.), as Rome continued its imperial ascent to near-hemispheric domination, the distance between the virtuous Republican nobility and the garish imperial nobility began to alert many to the potential for social degeneration. One of these was Plutarch, a Roman scholar of Greek birth.

Le premier roi du royaume de Grèce fut le prince bavarois Otto, sacré Otto I. Son accession au trône fut aussi un faux-fuyant. Tandis que des investisseurs capitalistes britanniques et français faisaient des affaires juteuses en Grèce, des fondations privées allemandes finançaient, sans aucun esprit de lucre, les infrastructures naissantes de l‘Etat grec et contribuaient à la renaissance de l’hellénité. Il semble que l’histoire se répète...

Le premier roi du royaume de Grèce fut le prince bavarois Otto, sacré Otto I. Son accession au trône fut aussi un faux-fuyant. Tandis que des investisseurs capitalistes britanniques et français faisaient des affaires juteuses en Grèce, des fondations privées allemandes finançaient, sans aucun esprit de lucre, les infrastructures naissantes de l‘Etat grec et contribuaient à la renaissance de l’hellénité. Il semble que l’histoire se répète...