mercredi, 28 décembre 2011

Nel deserto dell’umano. Potenza e Machenschaft nel pensiero di Martin Heidegger

Nel deserto dell’umano.

Nel deserto dell’umano. di Salvatore Spina

Fonte: recensionifilosofiche

il termine, che in italiano viene reso – non senza problemi ermeneutici – come “macchinazione”, indica il modo in cui l’essere si dispiega nell’era della tecnica, ovvero nell’epoca del compimento della modernità. Il lavoro di Gorgone, prendendo come punto di partenza questi testi e muovendosi in modo trasversale all’interno della sterminata produzione heideggeriana, vuole essere un’analisi del pensiero del filosofo di Messkirch dopo la svolta, e nel contempo il tentativo di individuare nel concetto di Machenschaft la chiave di volta di tutta la riflessione heideggeriana, che, dopo il fallimento del progetto di Essere e tempo, subisce quella “svolta ontologica” che ne delinea i tratti caratteristici in maniera peculiare lungo tutto il percorso successivo.

Tante altre notizie su www.ariannaeditrice.it

00:14 Publié dans Livre, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, allemagne, faisabilité, philosophie, martin heidegger, révolution conservatrice, technique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 27 décembre 2011

La critica di Spengler a Marx è di non aver capito il capitalismo moderno

di Francesco Lamendola

Fonte: Arianna Editrice [scheda fonte]

È quasi incredibile il fatto che neppure la crisi gravissima che le nostre società stanno attraversando abbia sollecitato negli ambienti culturali, oltre che in quelli economici, un serio dibattito sulle origini di essa e sui meccanismi della finanza che consentono di eludere il fisco e di spostare continuamente ingenti capitali al di fuori di qualsiasi controllo; meccanismi così capillari e pervasivi che perfino il più modesto cittadino, attraverso la trasformazione del risparmio in titoli azionari, diventa possessore teorico di proprietà delle quali non conosce assolutamente nulla se non il controvalore, sempre mutevole, in quotazioni borsistiche.

Questa arretratezza culturale quasi inconcepibile o, per dir meglio, questa assordante assenza di riflessione e di dibattito è, in larga misura, uno dei tanti effetti negativi che l’egemonia del marxismo ha avuto nella mentalità occidentale, anche fra coloro che lo hanno avversato e che lo hanno combattuto.

Una volta stabilito, in via definitiva, che Marx indiscutibilmente era un genio dell’economia politica, non restava che prendere per buona la sua analisi e attrezzarsi di conseguenza, sia che si auspicasse la rivoluzione comunista da lui propugnata, sia che la si paventasse; per cui non solo milioni di cittadini comuni, ma anche quasi tutta la schiera degli economisti e moltissimi filosofi dell’economia, sono rimasti letteralmente ipnotizzati dalle sue formule, dai suoi slogan e dai suoi mantra, ripetuti all’infinito con monotona ed esasperante insistenza.

Senonchè, Marx non era, forse, quel genio dell’economia che tutti affermano: la sua analisi dell’economia politica parte dalla realtà storica del 1848, ma vista - come osserva acutamente Oswald Spengler - con gli occhi di un liberale del 1789; in altre parole, le sue basi culturali erano quelle del diciottesimo secolo, e del capitalismo moderno egli aveva compreso poco o nulla, benché la rapida evoluzione di esso fosse proprio sotto i suoi occhi.

In particolare, Marx non si rese conto della crescente, inarrestabile trasformazione del capitale industriale in capitale finanziario e basò la sua riflessione su una figura quasi mitologica, quella del capitano d’industria che sfrutta gli operai della fabbrica, secondo il modello di Charles Dickens, mentre ben altri erano i meccanismi in movimento e ben altre le modalità di accumulazione capitalistica, assai più complesse e meno spettacolari.

E tuttavia, per quasi un secolo e mezzo, le masse occidentali sono rimaste affascinate e incantate da quella mitologia, da quello schema in bianco e nero, che presentava tutto come semplice e chiaro: di qua gli sfruttatori, alcuni loschi individui in cilindro e redingote, di là le masse sfruttate e sofferenti, gli onesti operai dalle mani callose, costretti a farsi schiavi delle macchine per impinguare i forzieri dei loro insaziabili padroni.

Lo stereotipo ingenuamente manicheo ha retto almeno fino al 1968, aiutato dal fatto, invero paradossale, che la cultura egemone in Italia, e in buona parte del mondo, fino a quella data e ancora oltre, è stata quella di matrice marxista, ma senza che praticamente nessuno di quanti la professavano si fosse dato in realtà la pena di leggere i ponderosi, noiosissimi volumi de «Il Capitale», e tanto meno di leggerli con un minimo di spirito critico. Non si legge un testo religioso con spirito critico, specialmente se si è degli apostoli zelanti: e tali si sentivano milioni di giovani e di meno giovai rivoluzionari” di sinistra, che facevano il tifo - oltre che per Marx - per Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Ho-chi-min e “Che” Guevara. I testi religiosi si citano come verità rivelata e si brandiscono come spade, magari per chiudere la bocca a qualche arrogante infedele.

L’immagine marxiana di una semplicistica contrapposizione fra “capitalista” e “proletario” è rimasta inalterata anche quando Engels, e soprattutto Lenin, hanno ripreso il discorso, riprendendolo là dove Marx di fatto lo aveva lasciato e sviluppando l’analisi del capitalismo finanziario, dei trust, dei cartelli e delle forme impersonali del capitale; ed è rimasta inalterata per la buona ragione che è molto più semplice creare un immaginario collettivo a sfondo mitologico, come ben sanno gli ideatori delle varie forme di pubblicità, specialmente televisiva, che non modificarlo o riequilibrarlo, una volta ch’esso si sia imposto.

Scriveva, dunque, Spengler ne «La rigenerazione del Reich» (titolo originale: «Neubau des Deutschen Reiches», Munchen, 1924; traduzione italiana di Carlo Sandrelli, Edizioni di Ar, Padova, 1992, pp. 92-95):

«L’ideale delle imposte dirette, calcolate in base ad una corretta valutazione fiscale dei propri redditi e pagate personalmente da ogni concittadino, oggi domina così incondizionatamente che la sua equità ed efficacia sembrano evidenti. La critica si rivolge ad aspetti particolari, non al principio in quanto tale. Eppure esso deriva non da considerazioni ed esperienze pratiche, ed ancor meno dalla preoccupazione di sostenere la vita economica, bensì DALLA FILOSOFIA DI ROUSSEAU. Ai crudi metodi degli appaltatori e degli esattori del 18° secolo, volti esclusivamente alla realizzazione di un profitto, esso contrappone il concetto dei diritti umani nati, fondato sulla rappresentazione dello Stato come frutto di un libero contratto sociale - figura, questa, che a sua volta viene contrapposta alle forme statali storicamente sviluppatesi. Secondo questa concezione, è dovere del singolo cittadino e rientra nella sua dignità umana stimare personalmente e pagare personalmente la propria partecipazione al pagamento dei carichi che gravano sull’intera società. Da questo momento la moderna politica fiscale si fonda, dapprima inconsapevolmente poi in modo sempre più chiaro, in corrispondenza con la crescente democratizzazione dell’opinione pubblica, su una Weltanschauung che cede ai sentimenti e agli stati d’animo politici, alla fine escludendo completamente un riflessione spregiudicata sull’adeguatezza dei procedimenti correnti. Quel concetto tuttavia era allora sostenibile. A quell’epoca, la struttura dell’economia era tale che i singoli redditi erano tutti palesi e facilmente accertabili. Essi derivavano dall’agricoltura, da un ufficio oppure dal commercio e dall’industria., dove, in virtù di un’organizzazione corporativa, ognuno poteva conoscere la situazione dell’altro. Non esistevano entrate maggiori da tener nascoste. Inoltre, allora i patrimoni erano un possesso immobile e visibile: terra e campi, case, aziende ed imprese che ognuno sapeva a chi appartenevano. Ma proprio con la fine de secolo è intervenuto nell’ambito economico un sovvertimento che ne ha interamente modificatola struttura interna, il ciclo ed il significato, e che risulta molto più importante di ciò che Marx intende per capitalismo”, ossia l’egemonia dei capitani d’industria. Proprio la dottrina di Marx, poiché parte da una segreta invidia e perciò può scorgere soltanto la superficie delle cose, per un secolo intero ha disegnato con linee false l’immagine riconosciuta dell’economia. L’influenza delle sue formule speciose è stata tanto maggiore in quanto essa ha rimosso i giudizi riferiti all’esperienza, soppiantandoli con i giudizi dettati dal sentimento. È stata così grande che nemmeno i suoi avversari vi si sono sottratti e che la normativa moderna sul lavoro poggia totalmente sui concetti fondamentali interamente marxisti di “prestatore di lavoro”e “datori di lavoro” (come se questi ultimi non lavorassero). Poiché queste formule si riferiscono agli operai delle grandi città, la dottrina rifletteva la svolta decisiva intervenuta verso la metà del XIX secolo con la rapida crescita della grande industria. Ma proprio nell’ambito della grande tecnica lo sviluppo era stato assai regolare. Un’industria meccanica esisteva già dal 18° secolo. Agisce piuttosto da fattore decisivo il progressivo svanire della proprietà intesa come qualità naturale delle cose possedute, con l’introduzione di certificati di valore, quali i crediti, le partecipazioni o le azioni. I patrimoni individuali diventano mobili, invisibili e inafferrabili Essi non CONSTANO più di cose visibili, giacché in queste ultime sono INVESTITI ed in ogni momento possono mutare il luogo e le modalità di investimento. Il PROPRIETARIO delle aziende si è contemporaneamente trasformato in POSSESSORE di azioni. Gli azionisti hanno perduto qualsiasi rapporto naturale, organico con le aziende. Essi nulla capiscono delle loro funzioni e capacità produttive, né se ne interessano: badano solo al profitto. Possono cambiare rapidamente, essere molti o pochi, e trovarsi in qualsiasi luogo; le quote di partecipazione possono essere riunite in poche mani, oppure disperse o addirittura finire all’stero. Nessuno sa a chi realmente appartenga un’azienda. Nessun proprietario conosce le cose che possiede. Conosce soltanto il valore monetario di questa proprietà secondo le quote di Borsa. Non si sa mai quante delle cose che si trovano entro i confini di un Paese appartengono ai suoi abitanti. Infatti, da quando esiste un servizio elettrico di trasmissione delle notizie - che con una semplice disposizione orale consente di cambiare anche la titolarità delle azioni oppure di trasferirle all’estero -, la partecipazioni di azionisti azionali in aziende del nostro Paese può aumentare o ridursi di quantità impressionanti in un’ora di Borsa, a seconda che gli stranieri cedano o acquistino pacchetti azionari, magari in un solo giorno. Oggi in tutte le Nazioni ad economia avanzata oltre la metà delle proprietà è diventata mobile ed i suoi mutevoli proprietari sono disseminati per tutta la terra, avendo perduto ogni interesse che non sia finanziario al lavoro effettivamente compiuto. Anche l’imprenditore è diventato sempre più un impiegato ed un oggetto di questi ambienti. Tutto questo non è riconoscibile nelle aziende medesime e non è accettabile con alcun metodo fiscale. Così però svanisce la possibilità di verificare l’assolvimento del dovere fiscale della singola persona, se il possessore di valori variabili non lo vuole. Lo stesso vale in misura crescente per i redditi. La mobilità, la libertà professionale, la soppressione delle corporazioni sottrae il singolo al controllo dei suoi compagni di lavoro. Da quando esistono ferrovie, piroscafi, giornali e telegrammi, la circolazione delle notizie ha assunto forme che liberano L’acquisto e la vendita dal limite del tempo e dello spazio. La vendita a distanza domina l’economia. Le transazioni a termine superano il semplice scambio tra produttori e consumatori. Il fabbisogno locale per il quale lavorava la corporazione viene ora soddisfatto dalla Borsa merci, che approfitta dei nessi tra la produzione, la distribuzione e il consumo di cose per realizzare guadagni speculativi. Per le banche, al posto delle operazioni di cambio del 18° secolo,la fonte principale di guadagno diventa l’erogazione di crediti, mentre la speculazione con i valori diventati mobili decide da un giorno all’altro nella Borsa valori sull’ammontare del patrimonio nazionale. Così anche i profitti commerciali e speculativi risultano sottratti a qualsiasi controllo ufficiale, alla fine rimangono soltanto i redditi medio-bassi che, come i salari e gli stipendi, sono così modesti che non è proprio possibile sbagliarsi sulla loro entità.»

Può essere una scoperta, per quanti hanno sempre considerato Spengler semplicemente come un filosofo della storia, scoprire in lui una tale acutezza nell’analisi dell’economia politica e una tale indipendenza di giudizio rispetto a un “mostro sacro” come Marx, del quale coglie tutta l’insufficienza speculativa, nonché i sotterranei meccanismi psicologici (la «segreta invidia» del piccolo borghese declassato rispetto ai ricchi imprenditori; salvo poi vivere senza alcun imbarazzo, si potrebbe aggiungere, sul portafoglio di quegli aborriti signori, tramite l’amico Engels che era, appunto, figlio di un capitano d’industria).

In effetti, la fama - positiva o negativa, questo non importa - de «Il tramonto dell’Occidente» ha messo alquanto in ombra le altre opere di questo filosofo e gli svariati e molteplici aspetti del suo itinerario speculativo.

Ma forse, vi è un’altra ragione per cui il cliché mitologico marxiano del capitalismo ha avuto tanto successo, nonostante la sua palese rozzezza e inverosimiglianza: il fatto che ampliare l’analisi dei meccanismi finanziari speculativi avrebbe recato un colpo decisivo all’immagine del proletario moralmente sano e antropologicamente differente dal bieco capitalista.

La verità è che, nella speculazione finanziaria, il cittadino comune è contemporaneamente vittima e carnefice: vittima, perché i suoi risparmi sono risucchiati in un mostruoso, anonimo meccanismo che li utilizza in modi a lui sconosciuti e, comunque, incomprensibili; carnefice, perché egli stesso si avvantaggia della legge della giungla che domina nelle Borse, e realizza margini di profitto ogni qualvolta si indeboliscono titoli e azioni detenuti da altri piccoli risparmiatori, simili a lui.

Tutto questo, naturalmente, non si accorda con il mito dell’operaio e del “lavoratore” senza macchia e senza paura, versione marxista del roussoiano “buon selvaggio”, perciò andava rimosso: le bandiere della rivoluzione andavano sventolate in omaggio a dei fantasmi ideologici, non alla realtà.

Tante altre notizie su www.ariannaeditrice.it

00:08 Publié dans Economie, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : économie, philosophie, oswald spengler, karl marx, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 26 décembre 2011

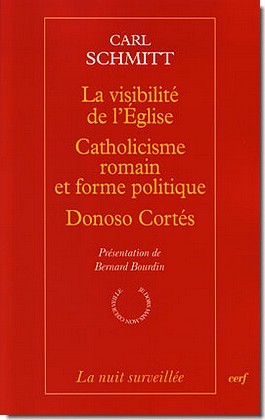

Carl Schmitt et la théologie politique...

Carl Schmitt et la théologie politique...

Ex: http://metapoinfos.hautetfort.com

Les éditions du Cerf viennent de publier un recueil comportant quatre essais inédits du juriste et philosophe politique allemand Carl Schmitt. Le volume est présenté par Bernard Bourdin, professeur de philosophie et de théologie à l'université de Metz, et préfacé par Jean-François Kervégan, auteur récent d'un essai intitulé Que faire de Carl Schmitt ? (Gallimard, 2011).

"L'expression « théologie politique » n'a jamais été utilisée en tant que telle par les théologiens chrétiens. Elle n'apparaît pour la première fois que dans le titre d'un ouvrage majeur de la philosophie du XVIIe siècle, le « Traité théologico-politique » de Spinoza. L'intention de son auteur était de conjoindre la souveraineté et la liberté de pensée, et par là même de régler le « problème théologico-politique ». Il faut attendre l'anarchiste Bakounine, au XIXe siècle, pour « réhabiliter » la théologie politique à des fins révolutionnaires, puis pour dénoncer le déisme de Mazzini.

En 1922, en rédigeant son premier texte sur la théologie politique, Carl Schmitt prend le contre-pied de l'anarchisme révolutionnaire. Avec le juriste rhénan, la théologie politique est désormais identifiée à la théorie de la souveraineté. C'est par une formule lapidaire, devenue célèbre, qu'il commence son essai : « Est souverain celui qui décide de la situation exceptionnelle. » Dès la fin du IIe Reich, puis dans le context de la république de Weimar, tout le projet intellectuel de Schmitt est d'articuler sa théorie du droit et du politique à une structure de pensée théologico-politique. Le problème de la démocratie libérale est son incapacité à disposer dune véritable théorie de la représentation, en raison de l'individualisme inhérent à la pensée libérale. Face à cette impuissance, le catholicisme, par sa structure ecclésiologique, offre au contraire tous les critères de la représentation politique et de la décision.

Les textes que Bernard Bourdin présente dans ce volume, parus entre 1917 et 1944, sont des plus explicites s'agissant de ces aspects de la théorie schmittienne : institution visible de l'Église, forme représentative et décisionnisme. Ils mettent de surcroît en évidence la double ambivalence de la pensée de Schmitt dans son rapport au christianisme (catholique) et à la sécularisation. En raison de son homologie de structure entre Dieu, État et Église, la nécessité d'une transcendance théologico-politique plaide paradoxalement pour une autre approche d'une pensée politique séculière. Ambivalence qui ne sera pas non plus sans équivoque."

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : carl schmitt, révbolution conservatrice, catholicisme, théologie politique, théorie politique, politologie, philosophie, sciences politiques, droit, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Generation Lovecraft: Die Flucht in den konservierten Raum

| Generation Lovecraft: Die Flucht in den konservierten Raum |

|

Geschrieben von: Dietrich Müller |

|

Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de/ |

|

Heute ist nichts mehr im Überfluss vorhanden. Das Wort Freizeit, vorher noch Gebot der Stunde, hat einen schalen Klang bekommen, sogar einen leicht despektierlichen. Von meinen Bekannten und Freunden gleichen Alters sind ungefähr ein Viertel durch Suizid abgetreten, ein großer Teil hat immerhin hart dorthin gearbeitet. |

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lovecraft, réflexions personnelles, philosophie, déclin, nihilisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 13 décembre 2011

Lumière de Herder

Lumière de Herder

En cette période de montée des nationalismes – voire des « ethnicismes » – en Europe comme ailleurs, les ethnologues, qui redoutaient naguère d’être considérés comme des suppôts du colonialisme, éprouvent souvent aujourd’hui, à l’inverse, l’angoisse d’être, malgré eux, de par la nature et l’objet même de leur discipline, des apôtres du tribalisme, des défenseurs inconscients d’un romantisme contre-révolutionnaire exaltant les valeurs particularistes contre l’universalisme des Droits de l’homme et du citoyen.

En cette période de montée des nationalismes – voire des « ethnicismes » – en Europe comme ailleurs, les ethnologues, qui redoutaient naguère d’être considérés comme des suppôts du colonialisme, éprouvent souvent aujourd’hui, à l’inverse, l’angoisse d’être, malgré eux, de par la nature et l’objet même de leur discipline, des apôtres du tribalisme, des défenseurs inconscients d’un romantisme contre-révolutionnaire exaltant les valeurs particularistes contre l’universalisme des Droits de l’homme et du citoyen.

En penseur, qu’on a pris récemment, un peu rapidement, pour l’emblème même de ce tribalisme (1), semble, au contraire, être un de ceux dont l’œuvre peut aider à lever cette angoisse, en ouvrant le chemin à un rationalisme rénové, apte à comprendre le lien qui, à l’est de l’Europe en particulier, mais à l’ouest parfois aussi, unit nationalisme et recherche de la démocratie. Ce penseur, c’est Johann Gottfried Herder.

Herder et l’Aufklärung

Herder, honni par Joseph de Maistre (2) et vénéré, au contraire, par Edgar Quinet, Thomas Mazaryk et d’autres grandes figures de la démocratie européenne et américaine, est un héritier éclatant de la pensée des Lumières, de l’Aufklärung du XVIIe siècle, même s’il la critique parfois. En fait cette critique est une critique « de gauche », dirait-on aujourd’hui, et non « de droite », comme celle de Maistre ou Bonald. Comme l’a écrit Ernst Cassirer, en Herder, la philosophie des Lumières se dépasse elle-même et atteint son « sommet spirituel » (Cassirer 1970 : 237).

Effectivement, il n’est guère de thèmes fondamentaux de sa pensée, du relativisme à la philosophie de l’histoire, du naturalisme au déisme, etc., dont on ne retrouve les antécédents, au XVIIe et au XVIIIe siècle, chez les meilleurs représentants de la philosophie des Lumières, qu’il s’agisse de Saint-Evremont ou de Voltaire, de l’abbé Du Bos ou de David Hume, d’Adam Fergusson ou de D. Diderot. Y compris le thème du Nationalgeist. Y compris celui du relativisme (je préférerais dire « perspectivisme »).

Ce n’est pas Herder, mais Hume qui, dans ses Essais de morale, écrit : « Vous n’avez point eu assez d’égard aux mœurs et aux usages de différents siècles. Voudriez-vous juger un Grec ou un Romain d’après les lois d’Angleterre ? Écoutez-les se défendre par leurs propres maximes, vous vous prononcerez ensuite. Il n’y a pas de mœurs, quelque innocentes et quelque raisonnables qu’elles soient, que l’on ne puisse rendre odieuses ou ridicules lorsqu’on les jugera d’après un modèle inconnu aux auteurs » (Hume 1947 : 192). Il est vrai que ce souci d’équité ethnologique ne signifie pas, pour Hume, qu’il ne faut pas souhaiter l’effacement de différences nationales. Mais, dans l’idéal, Herder le souhaite pareillement. S’il lui arrive de faire l’éloge des « préjugés », c’est-à-dire des présupposés culturels attachés à telle ou telle nation ou civilisation, c’est uniquement dans la mesure où cela peut donner aux pensées la force et l’effectivité qui risquent de leur manquer lorsqu’elles s’efforcent d’atteindre l’humain et l’universel seulement par un refus abstrait du particulier. L’idée est d’ailleurs dans Rousseau. Elle n’empêche pas de poser que « l’amour de l’humanité est véritablement plus que l’amour de la patrie et de la cité » (Herder 1964 : 327).

Quant au Nationalgeist, Montesquieu le nomme « esprit du peuple », « caractère de la nation ». Même chez Voltaire on trouve les notions de « génie d’une langue » et de « génie national » (3). Il est vrai que, chez eux, ce ne sont sans doute pas des principes originels, mais qu’ils dépendent d’autres facteurs historiques. Cependant, il n’en est pas autrement chez Herder. En fait, Herder voit dans le peuple ou la nation un effet statistique, produit par un ensemble de particularités individuelles, modelées par un même milieu, un même climat, des circonstances historiques communes, des emprunts similaires à d’autres peuples et la tradition qui en résulte. La nation n’apparaît comme une entité substantielle qu’à un regard éloigné, qu’à une vue d’ensemble. Herder est, au fond, sur le plan de la théorie sociale, comme il l’est d’ailleurs sur le plan éthique, un individualiste (4). La primauté de la société ne signifie rien d’autre, chez Herder, que l’idée que l’histoire ne peut être que celle des peuples, celle du peuple, et non celle des rois et de leurs ministres ; elle ne peut être que celle de la civilisation. Et, de ce point de vue, Herder est un voltairien qui ne s’ignore pas…

Une anthropologie de la diversité

Il y a cependant deux sources majeures de la pensée de Herder, sans lesquelles il n’est pas facile de la comprendre, et toutes deux ont eu une énorme influence sur l’Aufklärung allemande : ce sont l’œuvre de Leibniz et celle de Rousseau.

Sans Rousseau, il n’est pas possible de comprendre la logique qui unit le rationalisme de Herder à son anthropologie de la diversité. C’est Rousseau qui, le premier sans doute, nous a fait comprendre que la raison et la liberté étaient une seule et même chose. Herder lui emboîte le pas. Précurseur de Bolk et de Géza Roheim (5), théoricien de l’immaturité essentielle de l’homme ou, tout au moins, de son indétermination, qui fait sa liberté, mais qui est également la raison même de sa raison, Herder montre clairement que la diversité des cultures est la conséquence directe de l’existence de cette raison, qui n’est pas une faculté distincte, mais, en quelque sorte, l’être même de l’homme. La différence entre l’homme et l’animal n’est pas une différence de facultés, mais, comme il le dit dans le Traité sur l’origine de la langue, une différence totale de direction et de développement de toutes ses facultés (1977 : 71).

Mais si la raison n’est pas une faculté séparée et isolée, elle est présente dès l’enfance, dès l’origine, dans le moindre effort de langage. La raison herderienne est une raison du sens, non une raison du calcul, une raison vichienne, non une raison cartésienne, mais c’est une raison tout de même. Et fort importante, puisque la seconde ne va pas sans la première ; et puis parce que la raison cartésienne ne fonde ni morale ni droit.

Herder, comme Vico, a pressenti à quoi conduisait un certain cartésianisme. S’il n’existe pas un trésor de sens, où chacun puisse puiser ce qui le fait cet être unique et, en même temps, de part en part dicible (donc, par là même, en qui subsiste toujours du non-dit), qu’est un être humain, alors on parvient rapidement à l’humpty-dumptisme, qui est la pire des tyrannies. Chacun va décréter le sens des mots dans la mesure du pouvoir dont il dispose. Il n’y aura plus aucun contrat possible, aucune entente, sinon par le pouvoir despotique de quelque Léviathan. La politique de Descartes, ce ne pourrait être, effectivement, dans ces conditions, que le monstre froid que décrit Hobbes et où c’est, effectivement, le souverain qui décide du sens des mots. C’est bien ce monstre que les grands hommes d’Etat du XVIIe siècle cherchent à réaliser, à commencer par le cardinal de Richelieu. Cela aboutit finalement à la fameuse « langue de bois », même si cela ne commence que par d’apparemment innocentes académies.

Un eudémonisme relativiste

L’idée de l’essentielle variabilité humaine conduit à une éthique d’une grande souplesse, puisque, pour Herder, la raison est d’abord inhérente à la sensibilité ; et donnant pour fin à l’homme le bonheur, elle en modèle la figure idéale en fonction de la diversité des besoins et des sentiments. L’infinie variété des circonstances produit aussi une infinie variété des aspirations et le bonheur, qui est le but de notre existence, ne peut être atteint partout de la même façon : « Même l’image de la félicité change avec chaque état de choses et chaque climat – car qu’est-elle, sinon la somme de satisfactions de désirs, réalisations de buts et de doux triomphes des besoins qui tous se modèlent d’après le pays, l’époque, le lieu ? » C’est que « la nature humaine… n’est pas un vaisseau capable de contenir une félicité absolue…, elle n’en absorbe pas moins partout autant de félicité qu’elle le peut : argile ductile, prenant selon les situations, les besoins et les oppressions les plus diverses, des formes également diverses » (Herder 1964 : 183).

Il y a donc chez Herder une sorte d’eudémonisme relativiste que Kant ne pourra supporter, et qui signifie que, pour Herder, l’individu n’est pas fait pour l’État ni, d’ailleurs, pour l’espèce. Les générations antérieures ne sont pas faites pour les dernières venues, ni les dernières venues pour les futures. Ainsi le sens de la vie humaine n’est pas dans le progrès de l’espèce, mais dans la possibilité pour chacun, à toute époque, de réaliser son humanité, quelle que soit la société dans laquelle il vit et la culture propre à cette société. Il y a là un humanisme qui s’oppose à celui de Kant, pour qui nous devons accepter que les générations antérieures sacrifient leur bonheur aux générations ultérieures ; celles-ci, seules, pourront en jouir. Herder, au contraire, pense que chaque époque a son bonheur propre ; chaque époque, chaque peuple et même chaque individu. Car chaque période, mais aussi chaque individu forme, pour ainsi dire, un tout qui a sa fin en soi. C’est pourquoi Herder en vient même à récuser tout finalisme dans l’explication historique, de peur d’avoir à subordonner le destin des individus au cours de l’histoire globale. Dieu n’agit dans l’histoire que par des lois générales naturelles, non téléologiques, et par l’effet de notre propre liberté.

Des monades dans l’histoire

Mais Herder est aussi un leibnizien. C’est dire que son individualisme n’est pas atomistique, mais monadique ; ce qui signifie qu’il a un caractère dynamique et que l’individu y intègre l’universel qui est dans la totalité organique de l’histoire.

Ce que dit Ernst Cassirer de la conception leibnizienne de l’individuel éclaire la conception herderienne :

« Chaque substance individuelle, au sein du système leibnizien, est, non pas seulement une partie, un fragment, un morceau de l’univers, mais cet univers même, vu d’un certain lieu et dans une perspective particulière… toute substance, tout en conservant sa propre permanence et en développant ses représentations selon sa propre loi, se rapporte cependant, dans le cours même de cette création individuelle, à la totalité des autres et s’accorde en quelque façon avec elle » (Cassirer 1970 : 65).

Pourtant, il y a, dans Une autre philosophie de l’histoire (Auch eine Philosophie der Geschichte), un passage où Herder semble nous dénier la possibilité d’être, comme il dit, « la quintessence de tous les temps et de tous les peuples ». En fait, il admet que nous avons en nous toutes les dispositions, toutes les aptitudes, toutes les potentialités qui se sont manifestées comme réalités achevées dans les diverses civilisations du passé. De ce point de vue, il y a, en chacun de nous une égale quantité de forces et un même dosage de ces forces. Mais un leibnizien ne sépare pas l’individualité des circonstances qui modèlent son développement. L’individualité est dans la continuité d’un développement qui intègre les circonstances qui permettent à cette individualité de se manifester.

Or chaque civilisation, chaque culture réalise un des possibles de l’humain et en occulte d’autres (6). Au cours de l’histoire, il se peut donc que l’ensemble des virtualités de la nature humaine se trouvent réalisées, mais tour à tour, non simultanément. Chaque moment, cependant, fruit d’une égale nécessité, possède un égal mérite. Cela ne contredit pas l’idée d’un progrès d’ensemble, mais va contre un évolutionnisme pour lequel l’humain ne se réalise pleinement qu’au terme de l’histoire (ou de la préhistoire, pour parler le langage d’un certain marxisme).

Herder utilise, au fond, le principe auquel Haeckel donnera son nom en le formulant en termes biologiques, mais qui est aussi la maxime d’une vieille métaphore : la phylogénèse se retrouve dans l’ontogénèse ; et on comprend à partir de là comment il peut concilier progression – Fortgang – et égalité de valeur. L’enfance vaut par elle-même, elle a ses propres valeurs, son propre bonheur ; l’adolescence, de même. Mais c’est quand même l’adulte qui est l’homme achevé, l’homme dans sa maturité.

Mais, mieux encore, l’égalité herderienne des cultures et des époques trouve sa justification dans ce que Michel Serres (1968 : 265) appelle, chez Leibniz, « la notion d’altérité qualitative dans une stabilité des degrés » : « En passant du plaisir de la musique à celui de la peinture, dit Leibniz, le degré des plaisirs pourra être le même, sans que le dernier ait pour lui d’autre avantage que celui de la nouveauté… Ainsi le meilleur peut être changé en un autre qui ne lui cède point, et qui ne le surpasse point. » Il n’en reste pas moins qu’« il y aura toujours entre eux un ordre, et le meilleur ordre qui soit possible ». S’il est vrai qu’« une partie de la suite peut être égalée par une autre partie de la même suite », néanmoins « prenant toute la suite des choses, le meilleur n’a point d’égal (7) ». Mais on peut aller beaucoup plus loin, et dire que, de même qu’il y a équipotence entre, non seulement la suite des nombres pairs et la suite des carrés, mais la suite des carrés, par exemple, et la suite des entiers, le meilleur a même puissance dans une partie de la suite et dans l’ordre du tout.

Chez Herder, il se peut donc que chaque phase ou chaque époque soit la meilleure, que chaque culture soit la meilleure, mais qu’il y ait, en plus, un meilleur dans l’ordre de succession, c’est-à-dire un ordre progressif, où le meilleur n’est atteint que dans le progrès même, en tant que succession bien ordonnée. Au-delà, on peut dire aussi que l’universel – un universel dynamique, celui de l’histoire comme totalité non fermée – est présent dans la singularité des cultures et des individus.

Inversement, d’ailleurs, l’universel n’existe qu’incarné dans des singularités historiques. C’est le cas, par exemple, du christianisme, religion universelle par excellence, mais qui n’existe que sous telle ou telle forme, particulière à telle ou telle époque, à telle ou telle civilisation : « Il était radicalement impossible que cette odeur délicate pût exister, être appliquée, sans se mêler à des matières plus terrestres dont elle a besoin pour lui servir en quelque sorte de véhicule. Tels furent naturellement la tournure d’esprit de chaque peuple, ses mœurs et ses lois, ses penchants et ses facultés… plus le parfum est subtil, plus il tendrait par lui-même à se volatiliser, plus aussi il faut le mélanger pour l’utiliser » (Herder 1964 : 209-211).

Un patriotisme cosmopolite

La présence de l’universel dans le singulier et le fait que le singulier et l’universel ne puissent être séparés rend compte de la possibilité, pour Herder, d’être à la fois cosmopolite et patriote, comme le furent ultérieurement quelques-uns de ses grands disciples. Le cosmopolite selon Herder n’est donc pas l’adepte d’un cosmopolitisme abstrait qui s’étonne de ne pas retrouver en chacun l’homme universel qu’il prétend lui-même incarner. Le cosmopolitisme de Herder est un cosmopolitisme de la compréhension entre les peuples et entre les cultures, c’est un cosmopolitisme « dialogique ».

De 1765 (année où il prononce à Riga son discours, Avons-nous encore un public et une patrie commune comme les Anciens ?) jusqu’à la fin de sa vie, Herder gardera cette position humaniste, hostile au particularisme aveugle, favorable seulement à un patriotisme qui ouvre sur l’universel. Herder récuse le patriotisme exclusif des anciens, qui regarde l’étranger comme un ennemi. Il veut, quant à lui, voir et aimer tous les peuples en l’humanité, dont il dit qu’elle est notre seule vraie patrie.

Il est vrai que cette vertu d’humanité, il pensera finalement que le peuple allemand sera, dans la période de l’histoire qui vient, celui qui l’incarnera probablement le mieux et que son aptitude à la philosophie en fait un excellent porteur d’universalité ; ce qui n’est pas si mal vu, si l’on pense à l’éclatante lignée de penseurs que l’Allemagne produira, de Kant à Marx et au-delà. De Lessing, Herder et Kant, avec Schiller et Goethe, Herzen (1843) dira que leur but commun fut de « développer les caractères nationaux pour leur donner un sens universel ».

On pourrait en dire autant de la génération suivante, celle des romantiques, pour laquelle on affiche quelquefois en France un bien curieux mépris. De Tieck, Novalis, Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl (1890 : 336) écrivait : « Ce n’est pas un sentiment de patriotisme qui poussait ces écrivains à exhumer les trésors de l’Allemagne du Moyen Age. Le contraire est plutôt vrai : ce fut l’Allemagne du Moyen Age, retrouvée et passionnément aimée, qui réveilla en eux le patriotisme. Encore n’arrivèrent-ils à l’Allemagne que par un long et capricieux circuit, en faisant le tour du monde. Ils se seraient reproché, sans nul doute, de s’enfermer dans l’étude des antiquités germaniques. Elle eût offert à elle seule un champ de travail assez vaste ; mais les Romantiques ne s’y attardèrent point. Ils le parcoururent un peu, comme on l’a dit, en chevaliers errants. Leur humeur vagabonde, d’accord avec leur cosmopolitisme, les emportait bientôt ailleurs. »

Herder est préromantique dans la mesure où il y a, dans le romantisme, une sorte d’universalisme du populaire, où l’universalisme se concilie fort bien avec le pluralisme. En fait, ce qu’on retrouve dans le pluralisme littéraire de Goethe, de Herder et des romantiques d’Allemagne et d’ailleurs, c’est la volonté de réhabiliter le sensible et de fonder une esthétique, au sens large et au sens étroit. Peut-être même faut-il dire que le romantisme est là d’abord, et, de ce point de vue, il est déjà chez le Kant de la Critique du jugement, voire même chez Leibniz.

Mais cette réhabilitation du sensible est, en même temps et du même coup, une réhabilitation du sens, c’est-à-dire de la langue. Tout part de là chez Herder et tout y aboutit ; chez Herder comme aussi, par exemple chez Schlegel. Il s’agit d’édifier une science où l’on puisse vivre. Mais cette science est déjà présente dans la culture populaire, dans les cultures populaires. Cette réhabilitation du sensible s’intéresse donc au « populaire » en général, à l’« ethnique » si l’on veut, mais aussi à autrui, à l’autre en tant que tel, car autrui, c’est d’abord du sensible et il n’y a pas de monde sensible sans autrui. Autrui n’est accessible que comme sensible, et ce sensible ne peut être réduit. Feuerbach, de ce point de vue, est dans la postérité du romantisme, et le romantisme est peut-être ce qui a rendu possible l’ethnologie.

Herder « gauchiste »

Herder, cependant, reste un Aufklärer, mais, nous l’avons dit, un Aufklärer de gauche ; de gauche, et même d’extrême gauche. Et c’est la raison pour laquelle certains croient voir en lui un adversaire des Lumières, voire même un contre-révolutionnaire, ce qui constitue un assez joli contresens.

Il y a une autre raison de cette méprise, chez les auteurs français tout au moins : c’est que Herder se réclame du christianisme. C’est même un homme d’Église, un pasteur ; à l’époque (1784) où il écrit les Ideen (Herder 1962), il est évêque de Weimar. Or les Français pensent généralement que les Lumières sont nécessairement antichrétiennes, ce qui est une grave erreur historique, surtout en ce qui concerne l’Allemagne. Herder, en fait, est dans la tradition allemande de la Guerre des paysans, au temps de la Réforme, guerre dont l’idéologie fut celle d’un protestantisme populaire, millénariste et extrêmement avancé sur le plan social. C’est de Herder que Goethe tire l’idée de Goetz von Berlichingen. Mais on retrouve la même attitude chez le Herder tardif des Ideen, lorsqu’il fait l’éloge des hussites, de anabaptistes, des mennonites, etc., après avoir fait celui des bogomiles et des cathares pour les mêmes raisons. On le voit bien, dans ce chapitre des Ideen, où il se situe (Herder 1962 : 483-489). Cette position « gauchiste » de Herder aboutit effectivement à une critique de la philosophie des Lumières sur un certain nombre de points : théorie mystificatrice du contrat social, goût du despotisme « éclairé », tolérance envers l’esclavagisme et l’exploitation coloniale, avec sa brutalité destructrice, racisme, etc. Il s’agit bien d’une critique « de gauche », dont nous avons déjà vu une manifestation dans le refus de soumettre les individus aux « fins de l’histoire ».

En ce qui concerne la doctrine du contrat social, il ne faut pas oublier qu’elle a pris diverses formes et que chez certains de ses plus illustres défenseurs, elle aboutit à une légitimation de l’absolutisme. C’est le cas non seulement de la doctrine de Hobbes, mais de celles de Grotius et de Pufendorf. On oublie généralement le côté par où la théorie du contrat prétend engendrer la cité en engendrant le gouvernement de la cité. Hormis Rousseau, c’est le cas de nombre de ses adeptes. Et, dans ces conditions, ils admettront souvent que le gouvernement de la cité, quelles que soient sa nature et son origine de fait (y compris la conquête), existe par contrat tacite, ce qui n’est en fait, la plupart du temps, qu’une légitimation a posteriori de la force. C’est ce côté de la doctrine du contrat qu’attaque Herder, le côté par où, par une série de confusions, entre gouvernement et État, puis entre État et société, elle risque d’aboutir à l’absolutisme.

Herder est, avant tout, un adversaire du « despotisme éclairé », à la manière de Frédéric II et de quelques autres. Son soutien à ce que nous appellerions peut-être aujourd’hui des « ethnies » a principalement ce fondement. A tort ou à raison, il pense que la diversité ethnique, comme la multiplicité des corps intermédiaires (communautés diverses, villes-cités, etc.) est un puissant contrepoids à la force niveleuse du despotisme.

L’envers de cette haine du despotisme sous toutes ses formes, y compris le prétendu despotisme éclairé, c’est l’esprit démocratique. En dénonçant le nationalisme de Herder, on oublie que son nationalisme est lié à cet esprit démocratique. Les sujets d’un monarque n’ont pas de patrie. Le despotisme a aussi pour effet de freiner le développement des sciences et des arts. La culture, qui est créativité et non réception passive d’une tradition, est démocratique et nationale, tout à la fois et indissolublement.

Un nationalisme anarchiste

A vrai dire, Herder est non seulement antiabsolutiste, mais antiétatiste, contre l’État, anarchiste en ce sens-là. Contrairement à beaucoup de penseurs des Lumières, il soutient que l’État est, en lui-même, plutôt contraire au bonheur de l’individu que l’agent principal de ce bonheur. C’est un point important parce qu’il est à rattaché à cette méprise qui fait dire à Herder, par des citations isolées de leur contexte, qu’il est contre le mélange des nations et des cultures. Il n’est pas contre le mélange (8), il est contre l’État conquérant et impérialiste, qui groupe sous sa domination une foule de peuples divers dont il étouffe la diversité. C’est ce mélange-là que Herder repousse.

Herder est pour les peuples parce qu’il est pour le peuple, et il est pour le peuple parce qu’il est contre l’État, contre toute forme étatique, contre l’absurdité de la monarchie héréditaire (et la tradition, pour lui, sur le plan politique en tout cas, ne légitime rien du tout), contre la tyrannie des aristocraties, contre le Léviathan démocratique, dans la mesure où la démocratie reste un État, dans la mesure où elle est toujours cratie, même si elle est démo. Herder est aussi contre les classes sociales, qui vont contre la nature parce qu’elles ne sont établies que par la tradition, encore une fois – ce qui montre que Herder n’a rien d’un traditionaliste !

Pour Herder, tous les gouvernements éduquent les hommes pour les laisser dans l’état de minorité, dans une détresse infantile qui permet de mieux les dominer. Et, de ce point de vue, Herder retourne l’Aufklärung kantienne contre elle-même. Car c’est à Kant qu’il faut attribuer le principe cité par Herder dans les Ideen : « L’homme est un animal qui a besoin d’un maître et attend de ce maître ou d’un groupe de maîtres le bonheur de sa destination finale. » C’est un résumé de la position kantienne telle qu’elle est exprimée dans l’Idée d’une histoire universelle du point de vue cosmopolitique (Kant 1947 : 67 et sq.). Herder réplique : « L’homme qui a besoin d’un maître est une bête ; dès qu’il devient homme, il n’a plus besoin d’un maître à proprement parler… La notion d’être humain n’inclut pas celle d’un despote qui lui soit nécessaire et qui serait lui aussi un homme » (Herder 1962 : 157). Kant le prendra assez mal, mais c’est bien lui qui, dans sa philosophie de l’histoire prend position contre l’autonomie, et c’est Herder qui la défend.

L’antiétatisme de Herder est à relier à son antiartificialisme, à son antimécanicisme, et à cet organicisme dont on ne voit pas que, loin de subordonner l’individu aux finalités du tout, comme une pièce de la machine au fonctionnement de la mécanique entière, lui confère, au contraire, l’activité d’un organe sans lequel le tout ne pourrait s’animer. Il y a du Herder chez Stein, le ministre libéral de Frédéric-Guillaume IV, lorsqu’il soutient que l’Etat doit être non une machine, mais un organisme. Cette idée, précisément, est au fondement du libéralisme de Stein. Elle signifie que les sujets ne doivent pas être des instruments passifs aux mains de l’État, mais des organes actifs, capables d’initiatives.

L’antimilitarisme de Herder, sa polémique contre le principe de l’équilibre européen, invoqué par les princes pour mener leurs sujets au combat, sont à rattacher au même état d’esprit. La guerre est un instrument du totalitarisme de l’Etat monarchique, où personne « n’a plus le droit de savoir… ce que c’est que la dignité personnelle et la libre disposition de soi » (ibid. : 277), où le grain de sable qu’est l’individu ne pèse rien dans la machine (ibid. : 279).

Anticolonialisme

Mais Herder va plus loin dans le refus de certaines conséquences de la philosophie des Lumières, philosophie qui prône les vertus du commerce et de l’économie marchande. Dans une des pages les plus saisissantes de Une autre philosophie de l’histoire, il dénonce, avec une ironie voltairienne, les dévastations que fait subir à l’humanité la prédominance de cette économie marchande. C’est là une des clés de la pensée de Herder, qui a fort bien vu le lien étroit qu’il y a entre la colonisation « extérieure » et la colonisation « intérieure ».

Encore une fois, le point de vue de Herder est celui de la révolution paysanne. Herder est issu d’une famille de paysans pauvres et il a vécu à Riga, qui fut touchée par la révolte des anabaptistes au XVIe siècle. On peut peut-être rendre compte de son attitude à partir de là.

Il écrit donc : « Où ne parviennent pas, et où ne parviendront pas à s’établir des colonies européennes ! Partout les sauvages, plus ils prennent goût à notre eau-de-vie et à notre opulence, deviennent mûrs pour nos efforts de conversion ! Se rapprochent partout, surtout à l’aide de l’eau-de-vie et de l’opulence, de notre civilisation – seront bientôt, avec l’aide de Dieu, tous des hommes comme nous ! Des hommes bons, forts, heureux.

« Commerce et papauté, combien avez-vous déjà contribué à cette grande entreprise ! » Plus loin, il poursuit : « Si cela marche dans les autres continents, pourquoi pas en Europe ? C’est une honte pour l’Angleterre que l’Irlande soit si longtemps restée sauvage et barbare : elle est policée et heureuse. ».

Herder fait ensuite allusion au sort de l’Écosse. Mais il n’y en a pas que pour l’Angleterre ; la France n’est pas oubliée : « Quel royaume en notre siècle n’est devenu grand et heureux par la culture ! Il n’y en avait qu’un qui s’étalait au beau milieu, à la honte de l’humanité, sans académies ni sociétés d’agriculture, portant des moustaches et nourrissant par suite des régicides. Et vois tout ce que la France généreuse, à elle seule, a déjà fait de la Corse sauvage ! Ce fut l’œuvre de trois… moustaches : en faire des hommes comme nous ! des hommes bons, forts, heureux ! »

« L’unique ressort de nos États : la crainte et l’argent ; sans avoir aucunement besoin de la religion (ce ressort enfantin !), de l’honneur et de la liberté d’âme et de la félicité humaine. Comme nous savons bien saisir par surprise, comme un second Protée, le dieu unique de tous les dieux : Mammon ! et le métamorphoser ! et obtenir de lui par force tout ce que nous voulons ! Suprême et bienheureuse politique ! » (Herder 1964 : 271-273).

Plus loin encore, il récidivera, mettant cette fois en cause ce qu’il appelle le « système du commerce », et qui embrasse, semble-t-il, à la fois l’idéologie sous-jacente à la science économique et le capitalisme commercial, industriel et agraire : « Notre système commercial ! Peut-on rien imaginer qui surpasse le raffinement de cette science qui embrasse tout ? … En Europe, l’esclavage est aboli parce qu’on a calculé combien ces esclaves coûteraient davantage et rapporteraient moins que des hommes libres ; il n’y a qu’une chose que nous nous soyons permise : utiliser comme esclaves trois continents, en trafiquer, les exiler dans les mines d’argent et les sucreries – mais ce ne sont pas des Européens, pas des chrétiens, et en retour nous avons de l’argent et des pierres précieuses, des épices, du sucre, et… des maladies intimes ! Cela à cause du commerce, et pour une aide fraternelle réciproque et la communauté des nations ! « Système du commerce. » Ce qu’il y a de grand et d’unique dans cette organisation est manifeste : trois continents dévastés et policés par nous, et nous, par eux, dépeuplés, émasculés, plongés dans l’opulence, l’exploitation honteuse de l’humanité et la mort : voilà qui est s’enrichir et trouver son bonheur dans le commerce » (ibid. : 279-281).

On a rarement dénoncé avec autant de véhémence les ravages qui ont rendu possible l’édification de notre « économie-monde ». Herder a fort bien vu que l’entreprise, malgré « l’humanisme » de ses hérauts et thuriféraires, prenait volontiers appui sur un racisme ordinaire ou extraordinaire.

Antiracisme

Herder a fort bien vu aussi ce que la notion même de race, appliquée au genre humain, comporte de racisme implicite, dans la mesure où elle suppose, en fait, un polygénisme. Ceux qui, comme Buffon ou Kant se veulent monogénistes, mais parlent néanmoins de races humaines, sont donc, au moins, inconséquents. Herder est, lui, résolument monogéniste, contrairement à Voltaire, par exemple, qui pensait que « les Blancs et les Nègres, et les Rouges, et les Lapons et les Samoyèdes et les Albinos ne viennent certainement pas du même sol. La différence entre toutes ces espèces est aussi marquée qu’entre les chevaux et les chameaux »… Le monogénisme chrétien est donc à rejeter : « Il n’y a… qu’un brahmane mal instruit et entêté qui puisse prétendre que tous les hommes descendent de l’Indien Damo et de sa femme (9). »

Herder croit à la profonde unité de l’espèce humaine parce qu’il croit à la profonde unité des traditions. L’apparente diversité de ce qu’on appelle les races humaines n’est qu’un effet de la diversité des climats qui ne peut, tout au plus, produire que des variétés, mais qui ne pourrait, en aucun cas, engendrer des espèces. Cette diversité n’est donc pas un fait d’histoire naturelle, mais plutôt, pourrait-on dire, de géographie historique ou d’histoire géographique ; histoire qui témoigne, en tout cas, de la souplesse d’organisation de l’espèce humaine, c’est-à-dire de sa raison. Chez Herder, l’universalité de la raison prend appui non seulement sur la diversité des cultures, mais même sur la diversité d’apparence physique, de race, si l’on veut.

Selon lui, on perd le fil de l’histoire quand on a une prédilection pour une race quelconque et qu’on méprise tout ce qui n’est pas elle. L’historien de l’humanité doit être impartial et sans passion, comme le naturaliste, qui donne une valeur égale à la rose et au chardon, au ver de terre et à l’éléphant. La nature fait lever tous les genres possibles selon le lieu, le temps, la force. Conformément à l’inspiration leibnizienne de la pensée de Herder, « les nations se modifient selon le lieu, le temps et leur caractère interne », mais « chacune porte en elle l’harmonie de sa perfection, non comparable à d’autres » (Herder 1962 : 275). On retrouve ici ce que nous avons développé plus haut.

Herder est donc opposé également au racisme d’un Buffon, chez qui le racisme ou, comme dit Todorov, le « racialisme », entraîne la justification de l’esclavage et, bien entendu et a fortiori, de la colonisation et de la conquête (10). Mais il est probable qu’il ne pouvait non plus approuver Kant, pour qui, certes, même chez les Lapons, les Groenlandais, les Samoyèdes, même les « indigènes des mers du Sud » dont il est question dans les Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs (1957 : 141) ont droit à notre respect, mais qui n’en sont pas moins à considérer comme moralement condamnables : en premier lieu parce qu’ils n’ont pas su constituer d’État. Or l’État est la condition pour que nous ayons quelque chance d’atteindre à la moralité. En second lieu, et surtout, parce qu’ils ne s’appliquent pas à développer leurs aptitudes par le travail, bref, parce qu’ils n’ont pas notre culture. Plaçant le droit, le droit « rationnel » moderne au-dessus du bonheur et, avec le droit, le travail, l’activité productive qui éveille en l’homme l’idée de la supériorité de la raison sur les sens, Kant aboutit en fait à un naïf européocentrisme, peu en accord avec la philosophie de Herder.

Un nouveau Vico

En Europe même, la prétention à se faire l’éducateur du genre humain risque d’aboutir à une dictature platonicienne des « spécialistes de l’universel ». L’anthropologie herderienne nous propose une conception de la culture qui relativise par avance l’opposition : culture (au singulier) / cultures (au pluriel) ou, plus clairement, l’opposition pensée / culture (au sens de l’anthropologie). Que les cultures, au pluriel, ne contiennent aucune pensée active, aucune créativité, n’est vrai que dans la mesure où « les cultures » ont été écrasées, tronçonnées, émiettées, ôtées à leurs courants d’échange « naturels », mais cela se révèle faux partout où on les laisse s’épanouir normalement.

Herder est un nouveau Vico, qui a compris qu’une éducation purement cartésienne, une éducation de la « table rase », laisse l’homme désemparé, privé de tout repère moral et politique, arraché aux dimensions sociales de son être. L’éducation de la pure pensée doit se compléter d’une éducation des sens et des sentiments, d’une éducation « humaniste » qui fasse place aux certitudes morales, c’est-à-dire au plus probable. Les arts du langage y doivent tenir leur rang, trop souvent méconnu : l’art du discours et des lettres, l’art de la traduction également, nécessaire à la connaissance morale d’autrui, et sans lequel on conçoit mal que puisse se constituer une raison « dialogique ».

Cette raison a besoin aussi de connaissances ethnologiques et historiques, elle a besoin de ce décentrement de la pensée qu’elles procurent, et sans lequel il n’y a point de reconnaissance d’autrui. L’histoire anthropologique, à la manière de Vico ou de Herder réunit ces deux types de connaissances. Elle préfigure l’histoire telle qu’elle a été pratiquée de nos jours, depuis Fustel de Coulanges jusqu’à Michel Foucault, en passant par l’école des Annales. Conformément à l’esprit herderien, cette histoire est, non plus histoire des gouvernants et des hommes de guerre, mais histoire des peuples, histoire des gens, histoire de tous. L’histoire continuiste, dont certains ont la nostalgie, c’est la mythologie du pouvoir, de ce pouvoir qui est, d’ailleurs, souvent responsable précisément des coupures, des cassures dans l’histoire des simples gens et de leurs mentalités, comme il est responsable de l’enfermement des ethnies en elles-mêmes, de leur emprisonnement dans des frontières fermées, bloquant les échanges spontanés entre cultures.

Ce que dit Giuseppe Cocchiara (1981 : 21) de Gian Battista Vico, à savoir qu’avec lui, les traditions populaires entrent, de manière décisive, dans l’histoire, qu’avec lui aussi, les peuples dits « primitifs » sont appelés à faire partie de l’histoire de l’humanité et qu’à ce titre, il est un précurseur des méthodes de l’ethnologie, on pourrait le redire de Herder. Il n’y a pas de peuple qui ne soit dans l’histoire. L’égalité des peuples, c’est aussi cela, c’est l’égale vocation à entrer dans l’histoire et c’est l’égale sympathie que doit leur vouer l’historien. Les insuffisances de l’Aufklärung sur ce point ont persisté souvent jusqu’à nos jours.

Conclusions

Si nous ne perdons pas de vue que la culture allemande des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles a apporté beaucoup à celle de l’Est européen, en Russie même et chez les nations qui connaissent aujourd’hui un réveil démocratique, l’importance de Herder, qui y fut souvent lu et apprécié, n’échappera à personne.

Bien loin d’être un danger pour la démocratie, l’esprit herderien peut être un facteur qui permette d’exorciser les fantômes d’un nationalisme rétrograde et agressif, et d’intégrer les valeurs ethniques et nationales à un esprit démocratique rénové, où l’individualisme ne fasse pas obstacle au sens de la communauté et la recherche du bien-être à la créativité culturelle.

Mais pour que cela soit possible, il ne faut pas caricaturer la pensée de Herder et dévaloriser systématiquement l’une des conquêtes les plus précieuses de l’esprit scientifique, à savoir le perspectivisme, dans la mesure même où il nous permet de rendre justice à toutes les formes d’humanité.

En fait, il est paradoxal que l’on trouve aujourd’hui, du côté des philosophes et des spécialistes des sciences humaines, une remise en cause du perspectivisme et du particularisme linguistique et culturel, à un moment précisément où, à l’inverse, les spécialistes des sciences « dures » et des techniques haut de gamme en viennent au perspectivisme eux aussi – consciemment, car ils l’ont toujours pratiqué en fait – et, dans le travail même de la recherche et de l’invention technique et scientifique, vantent les mérites de la tradition culturelle et son potentiel de créativité.

L’utilisation de l’ordinateur va elle-même dans le sens du perspectivisme. Presque toujours l’ordinateur calcule faux, et il faut trouver son chemin dans le brouillard des erreurs. Or il y a plusieurs chemins possibles…

Dans la physique moderne, l’absence d’ambiguïté et le caractère prédictible des phénomènes a disparu, du fait, en particulier, de l’absence de simplicité du point de départ de la ligne d’événements à prévoir. Comme l’écrit l’épistémologue italien Tito Arecchi (1989), « l’existence d’un point de vue privilégié pour effectuer la mesure, sur laquelle tous les physiciens étaient d’accord, est tombée en disgrâce ». C’est du sein même de la théorie et de la pratique expérimentale physiciennes que surgit le perspectivisme.

Mais il y a un point sur lequel des physiciens et des techniciens se retrouvent pour rapprocher la science moderne des savoirs anciens : dans la recherche de la créativité, l’étude de la dynamique de l’invention scientifique et technique fait ressortir l’importance de l’oral, de l’expression parlée, dans la science et, par conséquent, l’importance de la langue et de l’enracinement de cette langue dans un terreau culturel particulier. Ce sont les physiciens et les technologues, aujourd’hui, qui deviennent herderiens. Je cite Jean-Marc Lévy-Leblond (1990 : 25-26), physicien théoricien : « On peut… tranquillement affirmer que la science, en France, est faite de beaucoup plus de mots français (parlés) qu’anglais (écrits). Qu’il soit nécessaire de rappeler cette évidence montre à quel point le débat est faussé par une grave erreur de conception sur la nature de la recherche scientifique, identifiée à son produit final (les publications), plutôt qu’à son activité réelle. Or cette vitalité de la langue naturelle dans la science est utile et féconde. La science se fait comme elle se parle. A s’énoncer, donc à se penser, dans une langue autre que la langue ambiante, elle perdrait son enracinement dans le terreau culturel commun et serait ipso facto privée d’une source essentielle, même si elle est souvent invisible, de sa dynamique. Les mots ne sont pas des habits neutres pour les idées : c’est souvent par leur jeu libre et inattendu que se fait l’émergence des idées neuves… Et cela est encore plus vrai si l’on considère l’autre versant de la recherche scientifique, celui non de la création novatrice, mais de la réflexion critique. »

Et André-Yves Portnoff, directeur délégué de Science et technologie, va dans le même sens. Avec David Landes, il regrette que beaucoup de responsables du tiers monde « cultivent l’illusion de moderniser leur pays en faisant table rase de leur héritage historique », alors qu’« aujourd’hui, la créativité technologique et industrielle, comme la créativité artistique, fait appel à l’imaginaire », et que, de ce point de vue, « chaque langue, dans toute son épaisseur historique, avec toutes ses strates de mémoire collective, constitue un instrument d’une richesse indispensable » (1990 : 26).

A entendre de tels propos, l’ombre de Herder frémirait d’aise dans l’au-delà. Mais à propos de Herder faut-il parler d’ombre ? Ou de lumière ? Nous optons pour la lumière.

Max Caisson,

« Lumière de Herder », Terrain, numero-17 – En Europe, les nations (octobre 1991)

———————————

Bibliographie :

Arecchi T., 1989. « Chaos et complexité », Le Monde/Liber, n° 1, oct.

Cassirer E., 1970. La philosophie des Lumières, Paris, Fayard (Die Philosophie der Aufklärung, Tübingen, 1932).

Cocchiara G., 1981. Storia del folklore in Italia, Palerme, Sellerio.

Finkielkraut A., 1987. La défaite de la pensée, Paris, Gallimard.

Herder J. G., 1977. Traité sur l’origine de la langue, Paris, Aubier (Abhändlung über den Ursprung der Sprache, 1770).

1964. Une autre philosophie de l’histoire, Paris, Aubier (Auch eine Philosophie der Geschichte, 1774).

1962. Idées pour la philosophie de l’histoire de l’humanité, Paris, Aubier (Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit, 1784).

Herzen A. I., 1843. « Le dilettantisme dans la science », Annales de la patrie.

Hume D., 1947 (1751). Essai de morale, in Enquête sur les principes de la morale, trad. de A. Leroy, Paris, Aubier.

Kant E., 1947. Philosophie de l’Histoire (Opuscules), trad. de St. Piobetta, Paris, Aubier.

1957 (1797). Fondements de la métaphysique des mœurs, trad. de V. Delbos, Paris, Delagrave.

Lévi-Bruhl L., 1890. L’Allemagne depuis Leibniz, Paris, Hachette.

Lévy-Leblond J.-M., 1990. « Une recherche qui se fait comme elle se parle… », Le Monde diplomatique, janv.

Portnoff A.-Y., 1990. « La créativité victime des jargons », Le monde diplomatique, janv.

Roheim G., 1972. Origine et fonction de la culture, Paris, Gallimard.

Serres M., 1968. Le système de Leibniz et ses modèles mathématiques, I, Paris, PUF.

Todorov T., 1989. Nous et les autres, Paris, Le Seuil.

———————–

Notes :

1 – Cf. Finkielkraut (1987).

2 – J. de Maistre appelle Herder « l’honnête comédien qui enseignait l’Evangile en chaire et le panthéisme dans ses écrits ». C’est dire la sympathie qu’il éprouvait pour lui…

3 – Cf. l’article « Français » dans l’Encyclopédie.

4 – En ce qui concerne l’éthique herderienne, voir, dans le présent article, le paragraphe intitulé « Un eudémonisme relativiste. ».

5 – Voir notamment Roheim 1972.

6 – On pourrait, sur ce point, comparer la pensée de Herder avec certaines thèses de Cl. Lévi-Strauss.

7 – Leibniz, 1710. Essais de Théodicée : paragraphe 202.

8 – La preuve est que, pour lui, la prééminence actuelle de l’Europe est due, pour une part, à l’extraordinaire mélange de populations et de cultures qui la caractérise : « En aucun continent les peuples ne se sont autant mélangés qu’en Europe ; en aucun autre ils n’ont si radicalement et si souvent changé de résidences, et avec celles-ci de mode de vie et de mœurs… fusion sans laquelle l’esprit général européen aurait difficilement pu s’éveiller » (Herder 1962 : 309).

9 – Voltaire, Essai sur l’histoire générale et l’esprit des nations depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à nos jours, ch. III.

10 – Voir particulièrement le chapitre intitulé « Les voies du racialisme » dans l’ouvrage de Todorov (1989 : 179 et sq.).

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, herder, allemagne, différentialisme, 18ème siècle, idéologie des lumières, lumières, enracinement, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, romantisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 03 décembre 2011

Equidad (epieikéia), la excepción ante la ley

Equidad (epieikéia), la excepción ante la ley

Alberto Buela (*)

Cuando algo no se tiene claro en filosofía lo primero que se recomienda es comenzar por la cuestión del nombre, el quid nominis, qué es lo que significa el término.

Equidad, una palabra cada vez más en desuso, proviene del latín aequitas que es la traducción del término griego epiéikeia. Vocablo constituido por el prefijo épi= alrededor de, sobre, acerca de, y el verbo éiko= semejar, ser conveniente, estar bien, cuyo participio presente eikós significa: parecido, semejante, conveniente, razonable, natural verosímil, vemos entonces como todos estos conceptos se pueden resumir en el término “equitativo”.

Aristóteles, siempre Aristóteles, fue el primero que se detuvo a pensar sobre la equidad, y en su principal obra sobre el obrar humano, La ética nicomaquea, afirma: “lo equitativo es una corrección de los justo legal= tò nomikón (1137 b 13). Y en La Retórica lo confirma cuando sostiene que: “lo equitativo es aquello justo que está más allá de la ley escrita= parà tón gegramménon nómon (1374 a 28).

Como la ley considera lo que se da las más de las veces, el legislador busca encontrar una expresión universal pero sabiendo va a haber excepciones a la ley, ya sean errores o casos no contemplados, porque no es posible abarcar todos los casos en su singularidad, entonces interviene la equidad.

Ahora bien, la equidad no surge por una falencia de la ley o un error del legislador sino que está fundada en la naturaleza de la cosa, pues así es la materia concerniente a las acciones de los hombres. Es que el obrar humano se mueve en el plano de la verosímil, de la plausible, de la contingencia y no podemos exigirle a él la exactitud matemática, sino a lo sumo el rigor moral de hacer el bien y evitar el mal.

La equidad viene a socorrer a la ley y corregir su omisión en los casos singulares. “Y esa es la naturaleza de lo equitativo: ser corrección de la ley en tanto que ésta incurre en omisiones a causa de su índole general” (1137 b 26-27).

Así lo equitativo siendo lo justo es mejor que lo justo “relativamente”, en la aplicación de los casos particulares, pero no es mejor que lo justo “absolutamente”. Lo justo es aplicable al género mientras que lo equitativo a cada una de sus especies.

Como todo no se puede legislar, existen infinidad de cosas y situaciones que no se pueden someter a la ley. Para ello los gobiernos cuentan con los “decretos”, que a diferencia de la ley= nómos, que es de carácter general, se aplican a una situación o caso singular. El hombre equitativo, el spoudaios, no se atiene a la rigidez de la ley sino que va más acá o más allá y cede en orden al castigo fijado por la ley, buscando la indulgencia y diferenciando entre el error, el acto desafortunado y el acto injusto, pero teniendo siempre “a la ley como defensora” (1138 a 2). La equidad no deroga la ley sino que aprovecha el propio pliegue o resquicio no contemplado por la universalidad de la ley. Es un correctivo a la justicia legal.

Para la jurisprudencia romana, la aequitas era la moderación del rigor de la ley por causas éticas, políticas o culturales, mientras que para la patrística cristiana era la moderación por causas o motivos de caridad y misericordia.

Para la teólogos escolásticos medievales era la justicia supralegal, sobre lo especial y excepcional. Retoman, en cierta medida, la visión griega clásica con el adagio: summun ius, summa inuria, mientras que para la ciencia jurídica moderna, es la interpretación de la ley, caracterizada por un máximo de libertad y flexibilidad.

Para el denominado ius naturalismo contemporáneo, es la justicia natural, o derecho justo, mientras que para la jurisprudencia anglosajona, la equidad, es un cuerpo especial de la norma jurídica consuetudinaria.

La equidad es una virtud, que como tal, es considerada como un término medio entre dos extremos opuestos, sea por exceso o sea por defecto. Así por exceso desemboca en la permisividad y por defecto, no tiene nombre ese vicio. Pero como toda virtud moral no se encuentra en un término medio matemático, la equidad se encuentra más inclinada hacia la permisividad que hacia el rigor. “Ser indulgente con las cosas humanas es también de equidad” (Retorica, 1374 b 11).

En el 2002 el máximo representante de los liberals norteamericanos, John Rawls publicó un libro titulado Justicia como equidad en donde responde a las críticas a su libro Teoría de la justicia de 1971. Allí sostiene que solo el socialismo democrático o liberal pueden constituir una sociedad equitativa, el resto de las opciones contemporáneas violan elementos o principios de justicia. “Los individuos bajo un velo de ignorancia eligen el principio de igual trato” (sic).

El esfuerzo teórico de Rawls, si bien loable, no supera la ideología del igualitarismo liberal nacido hace doscientos años y que se resuelve en una vacía formalidad de ordenanzas y decretos, que nos recuerdan “el como sí” de la máxima kantiana.

La equidad no se funda en la igualdad de trato, ni en la igualdad de oportunidades ni en la igualdad ante la ley, sino que tiene su fundamento en el spoudaios, en el hombre íntegro, noble y cabal que como tal se alza como norma del obrar humano, incluso sobre la ley misma en aquello que falla.

Y es en la formación de este tipo de hombre en que radica la mayor y mejor equidad de nuestras sociedades.

Surge aquí una vez más la clara distinción entre aquellos, como Rawls y Kant que privilegian el deber sobre el bien, y así para ellos el hombre es bueno o equitativo (en este caso) cuando realiza actos buenos, esto es, actos que debe realizar. En cambio para otros, aquellos que privilegian el bien, el hombre realiza actos buenos porque ya es bueno, este hombre no obra por deber sino por inclinación de su propia índole, que se fue formando a través de su tiempo de vida, principalmente en la niñez y juventud. (Siempre hay que recordar el viejo dicho criollo: Burro viejo, no agarra trote).

La pregunta por el bien es más amplia que la pregunta por el deber, puesto que no podemos saber qué hacer sino sabemos qué es el bien. Así como posee mayor jerarquía moral un “hombre bueno” que un “buen hombre”. Pues este último hace lo que debe hacer, mientras que aquél va más allá del deber y la justicia.

Esta disyuntiva fatal se nota en forma evidente en la vida espiritual cuando erróneamente se le exige a todos igual capacidad de sacrificio y privaciones, por el deber de realizarlas. Cuando en realidad, en la vida del espíritu cada uno tiene su tope o maximun y no se le puede exigir más pues, de lo contrario, fracasan y terminan abandonando la tarea propuesta y malográndose personalmente. Cuantas vocaciones laudables se han fracasado por un rigorismo moral inadecuado a la naturaleza del postulante. Y cómo ello ha funcionado como fuente del resentimiento espiritual que, en la práctica, no tiene cura.

En la vida del espíritu es donde más y mejor se nota la desigualdad entre los hombres. Es donde se pone de manifiesto que, no solo somos personas: seres singulares e irrepetibles, morales y libres sino que además tenemos distintas jerarquías. La plenitud de uno puede ser mínima pero es plenitud (una copa pequeña pero llena hasta el tope) y la plenitud de otros puede ser mediana o máxima pero es plenitud (copas más grandes pero hasta el tope). De lo contrario se fracasa por exigencia en exceso.

Esto, está magníficamente reflejado en le grito desesperado de Salieri, aquel oscuro músico que se comparaba con el genio de Mozart cuando arrojando el crucifijo al fuego, grita: “Toma, porqué me has dado la vocación y no los talentos”.

El hombre equitativo es el que auna en sí: talento y vocación para llenar el vacío que dejo la universalidad de la ley en el caso singular. Funciona así como criterio de los actos para los cuales la ley es insuficiente.

Para aquellos que privilegian el deber el hombre es bueno cuando realiza actos buenos, esto es, los actos que debe realizar. En cambio para los otros, los que privilegian el bien, el hombre realiza actos buenos porque es bueno, este hombre no obra por deber sino por inclinación de su buena índole.

Al respecto, alguna vez comentando el mito platónico de Giges hemos sostenido que: “Esta teoría (la de la justicia, la del obrar por deber) tiene una limitación, y es que muchas veces y en muchas ocasiones, el hombre honrado para ser justo, para seguir siendo “buen hombre” debe ir más allá de la justicia, hecho no contemplado por John Rawls. Así por ejemplo, quien se deja calumniar sin defenderse para no traicionar la confianza de un amigo. Quien no vuelve la espalda a un hombre injustamente perseguido y la da cobijo. Quien da consejo en una disputa familiar a riesgo de ser odiado por ambas partes. Quien paga una deuda de un hermano o de un amigo sin tener obligación de hacerlo. En todos estos casos, aquél “buen hombre” se transforma en un “hombre bueno”.” [1]

Este ejemplo nos muestra objetivamente como la pregunta por el bien es más amplia que la pregunta por el deber, puesto que no podemos saber qué hacer sino sabemos qué es el bien.

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, droite, exception, alberto buela, argentine, amérique latine, amérique du sud |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 27 novembre 2011

Goethe and the Indo-European religiosity

Goethe and the Indo-European religiosity

Hans Friedrich Karl Günther

The greatest ideas of mankind have been conceived in the lands between India and Germania, between Iceland and Benares (where Buddha began to teach) amongst the peoples of Indo-European language; and these ideas have been accompanied by the Indo-European religious attitude which represents the highest attainments of the mature spirit. When in January 1804, in conversation with his colleague, the philologist Riemer, Goethe expressed the view that he found it “remarkable that the whole of Christianity had not brought forth a Sophocles”, his knowledge of comparative religion was restricted by the knowledge of his age, yet he had unerringly chosen as the precursor of an Indo-European religion the poet Sophocles, “typical of the devout Athenian… in his highest, most inspired form”,41 a poet who represented the religiosity of the people, before the people (demos) of Athens had degenerated into a mass (ochlos). But where apart from the Indo-European, has the world produced a more devout man with such a great soul as the Athenian, Sophocles?

Where outside the Indo-European domain have religions arisen, which have combined such greatness of soul with such high flights of reason (logos, ratio) and such wide vision (theoria)? Where have religious men achieved the same spiritual heights as Spitama Zarathustra, as the teachers of the Upanishads, as Homer, as Buddha and even as Lucretius Carus, Wilhelm von Humboldt and Shelley?

Goethe wished that Homer’s songs might become our Bible. Even before the discovery of the spiritual heights and power of the pre-Christian Teuton, but especially after Lessing, Winckelmann and Heinrich Voss, the translator of Homer, the Indo-European outlook renewed itself in Germany, recalling a world of the spirit which was perfected by great German poets and thinkers during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Since Goethe’s death (1832), and since the death of Wilhelm von Humboldt (1835), the translator of the devout Indo-European Bhagavad Gita, this Indo-European spirit, which also revealed itself in the pre-Christian Teuton, has vanished.

Goethe had a premonition of this decline of the West: even in October 1801 he remarked in conversation with the Countess von Egloffstein, that spiritual emptiness and lack of character were spreading — as if he had foreseen what today characterises the most celebrated literature of the Free West. It may be that Goethe had even foreseen, in the distant future, the coming of an age in which writers would make great profits by the portrayal of sex and crime for the masses. As Goethe said to Eckermann, on 14th March 1830, “the representation of noble bearing and action is beginning to be regarded as boring, and efforts are being made to portray all kinds of infamies”. Previously in a letter to Schiller of 9th August 1797, he had pointed out at least one of the causes of the decline: in the larger cities men lived in a constant frenzy of acquisition and consumption and had therefore become incapable of the very mood from which spiritual life arises. Even then he was tortured and made anxious, although he could observe only the beginnings of the trend, the sight of the machine system gaining the upper hand; he foresaw that it would come and strike (Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre, Third Book, Chapter 15, Cotta’s Jubilee edition, Vol. XX, p. 190). In a letter to his old friend Zelter, on 6th June 1825, he pronounced it as his view that the educated world remained rooted in mediocrity, and that a century had begun “for competent heads, for practical men with an easy grasp of things, who [...] felt their superiority above the crowd, even if they themselves are not talented enough for the highest achievements”; pure simplicity was no longer to be found, although there was a sufficiency of simple stuff; young men would be excited too early and then torn away by the vortex of the time. Therefore Goethe exhorted youth in his poem Legacy of the year 1829:

In increasing degree since approximately the middle of the nineteenth century poets and writers as well as journalists — the descendants of the “competent heads” by whom Goethe was alarmed even in the year 1801 — have made a virtue out of necessity by representing characterlessness as a fact. With Thomas Mann this heartless characterlessness first gained world renown. Mann used his talent to conceal his spiritual desolation by artifices which have been proclaimed by contemporary admirers as insurpassable. But the talent of the writers emulating Thomas Mann no longer sufficed even to conceal their spiritual emptiness, although many of their readers, themselves spiritually impoverished, have not noticed this.