Vivimos la crisis más grave que haya conocido la Humanidad. Son los tiempos oscuros del Kali-Yuga, la era tenebrosa que cierra todo un ciclo histórico y cósmico. Estamos ante una sociedad enferma, afectada por una incurable dolencia que se encuentra ya en su fase terminal.

El mundo, y en especial el mundo occidental, se halla hoy sumido en un proceso de hundimiento y decadencia que viene caracterizado por los siguientes rasgos: caos y desorden, anarquía (sobre todo en las mentes y las conciencias), desmadre total, confusión y desorientación, inmoralidad y corrupción, desintegración y disgregación, descomposición, inestabilidad y desequilibrio (en todos los órdenes: tanto a nivel social como en la vida psicológica individual), ignorancia, ceguera espiritual, materialización y degradación de la vida, descenso del nivel intelectual y eclipse de la inteligencia, estupidez e idiotización generalizadas, demencia colectiva, ascenso de la vulgaridad y la banalidad. Por doquier se observa un fenómeno sísmico de ruina, destrucción, socavación y subversión, en el cual queda arrumbado y corroído todo aquello que da nobleza y dignidad al ser humano, todo cuanto hace la vida digna de ser vivida, mientras irrumpen fuerzas abisales que se recrean y complacen en esa oleada destructiva, amenazándonos con las peores catástrofes que haya podido imaginar la mente humana.

La crisis no es sólo económica, política o social, aunque esto sea lo más evidente a primera vista, lo que más llama la atención y de lo que se habla a todas horas en la prensa, en los telediarios y en las tertulias. La grave crisis que padecemos tiene raíces mucho más profundas de lo que solemos pensar. Es ante todo una crisis espiritual, una crisis humana, con hondas consecuencias intelectuales y morales. Es una crisis del hombre, que se halla desintegrado, angustiado, aplastado, hastiado, cansado de vivir, sin saber adónde ir ni qué hacer.

Es, por otra parte, una crisis que afecta a la existencia en su totalidad, incluso a la existencia natural y cósmica (como lo demuestra la crisis ecológica y la destrucción de la Naturaleza y el medio ambiente). No hay ningún aspecto o dimensión de la vida que escape a esta terrible crisis, a esta ola destructiva y demoledora de todo lo valioso. Todo se ve afectado por el desorden y el caos: la cultura, el arte, la filosofía, la medicina, la enseñanza, la religión, la familia, la misma vida íntima de los seres humanos.

Se pueden distinguir tres aspectos en este proceso de crisis total y ruina generalizada:

1) Ruina y destrucción de la Cultura

2) Ruina y destrucción de la Comunidad

3) Ruina y destrucción de la Persona

Podríamos decir, pues, que nos hallamos ante tres dimensiones de la crisis: una crisis cultural, una crisis social y una crisis personal. Tres formas o dimensiones de la crisis que repercuten de lleno en todos y cada uno de nosotros.

Son éstas tres formas de ruina y destrucción que se hallan íntimamente entrelazadas, no pudiendo analizarse ni solucionarse por separado. No se puede entender ninguna de ellas si no se consideran las otras dos. No se podrá dar respuesta a ninguno de tales procesos de ruina y demolición ni solucionar el mal que conlleva cada uno de ellos si se prescinde de los dos que lo acompañan.

Se trata de tres destrucciones que no son sino tres facetas de una misma y única destrucción: la destrucción de lo espiritual, la destrucción de lo humano. Es el resultado, en suma, de la persistente labor de zapa llevada a cabo por lo que los alemanes llaman der Ungeist, “el anti-espíritu”, “in-espíritu” o “des-espíritu”, esto es, la tendencia hostil a lo espiritual y trascendente, la negatividad operante, corrosiva y subversiva. La potencia más dañina y nefasta que podamos concebir, cuya acción se traduce en un socavamiento de toda espiritualidad y una total desespiritualización de la vida.

1) Ruina de la Cultura

La Cultura, que es todo aquello que eleva y ennoblece la vida del hombre (religión, filosofía, arte, música, poesía y literatura, ética y modales), se ve hoy día aplastada por la Civilización, entendida como el conjunto de las técnicas, los medios y los recursos que permiten a la Humanidad sobrevivir, defenderse de los peligros que la amenazan y mejorar su nivel de vida material (economía, organización política, ejército, burocracia, industria, transportes, medios de comunicación, hospitales, etc.).

La Civilización, que debe estar siempre al servicio de la Cultura, se ha erigido en dueña y señora, convirtiéndose en dominadora absoluta y poniendo a la Cultura a su servicio. Los factores, recursos y criterios civilizatorios, que van ligados a lo material, se han impuesto de modo omnímodo sobre los culturales y espirituales.

Se ha alterado así el orden y la jerarquía normal, con las funestas consecuencias que semejante desorden acarrea. La consecuencia más inmediata es la decadencia y ruina total de la vida cultural, que está en peligro de desaparecer por completo en Occidente ante la asfixiante presión del elemento civilizatorio. La Cultura se ve hoy obligada a mendigar como una pobre cenicienta despreciada y a pedir que le perdonen la vida, no quedándole otro remedio que refugiarse en las catacumbas.

En nuestros días la Cultura se halla amenazada por el avance de tres deplorables fenómenos hoy muy en boga, en alza y auge crecientes: la incultura (la ignorancia pura y simple, la falta de formación y el embrutecimiento desidioso), la subcultura (en la cual la vida cultural queda degradada al nivel de simple diversión, entretenimiento y espectáculo) y, lo que es más peligroso y nefasto de todo, la anticultura (esto es, la antítesis radical de la Cultura, al someter la actividad cultural a los criterios de un individualismo y un relativismo despiadados, con la consiguiente labor corrosiva, demoledora y desconstructora).

La anticultura, que va ligada a la expansión del nihilismo, se orienta frontalmente contra la Cultura, busca suplantar la genuina creación cultural por la producción de engendros ininteligibles y sin valor alguno, cuyo único impulso parece ser el afán de originalidad y el propósito rompedor. La creación cultural pasa a ser concebida como un activismo caótico y arbitrario que no debe ajustarse a normas de ningún tipo, que no debe ponerse metas de calidad y excelencia ni tiene por qué realizar ningún servicio a la comunidad y a los seres humanos. Así surge todo ese páramo demencial del “arte contemporáneo” que es en realidad antiarte, de la “poesía abstracta” que es en realidad antipoesía y de la “música de vanguardia” que es en realidad antimúsica. Igualmente nos encontramos con antiarquitectura, una antifilosofía, una antieducación, una antimoral o antiética.

Con ello se rompen todos los moldes de lo que durante milenios se había entendido por “cultura”. Y así vemos cómo se va haciendo imposible el surgir de una cultura auténtica, mientras son adulterados de manera desconsiderada e irrespetuosa los bienes culturales recibidos del pasado Véase, como ejemplo, las representaciones grotescas, ridículas y estrafalarias, de obras clásicas de teatro y óperas de grandes compositores, con el pretexto de actualizarlas y modernizarlas; o también la pretensión de expurgar o corregir antiguas obras literarias y filosóficas, como la Divina Comedia de Dante, para ajustarlas a lo políticamente correcto.

Toda esta oleada anticultural no hace sino poner de relieve la alarmante crisis de valores que sufre el mundo actual. Una crisis de valores que se va agravando a medida que avanzan la incultura, la subcultura y la anticultura, con la irresponsable colaboración activa de intelectuales, artistas, museos, prensa y órganos de comunicación, gobiernos y promotores seudo-culturales, que con sus apoyos y subvenciones a la bazofia anticultural, y poniendo al servicio de la misma, para promocionarla e imponerla, todo su aparato propagandístico, están promoviendo en realidad la destrucción o desconstrucción de la Cultura.

La Cultura es un cosmos de valores. Toda cultura normal y auténtica está basada en los valores supremos de la Verdad, el Bien (o la Bondad) y la Belleza (que lleva asociada, como una derivación lógica y natural, la Justicia). La actividad cultural no tiene otro sentido ni otra misión que servir de cauce para la realización de tales valores, procurando ponerlos al alcance de los seres humanos para así elevar, dignificar y ennoblecer sus vidas.

La Cultura está al servicio de la Humanidad. Toda creación cultural ha de estar inspirada por un hondo sentido de servicio, ha de ser consciente de sus deberes, tanto hacia los principios y normas que deben guiarla como hacia los seres humanos a los que debe servir. Cuando un organismo social está sano y tiene una cultura vigorosa y saludable, va buscando la defensa y realización de lo verdadero, lo bueno, lo bello y lo justo. Y ello, como el mejor servicio que se pueda hacer a la persona humana, para contribuir a su realización integral.

En el proceso de ruina y decadencia que vivimos en el presente estas verdades elementales se han olvidado por completo, o mejor dicho, se ha decidido relegarlas al trastero de las antiguallas y las cosas inservibles. La Cultura ha dejado de cumplir con su deber y su misión. La seudo-cultura imperante piensa que no tiene deber alguno que cumplir, que no tiene por qué servir a nada ni a nadie y, por supuesto, que no hay principio ni norma alguna a la que tenga que someterse. Para los individuos que encarnan y representan la anticultura actual sólo hay derechos: el derecho a expresarse, el derecho a hacer lo que les dé la gana, el derecho a producir cualquier cosa que se les ocurra (por muy dañina, ofensiva o repugnante que pueda ser), el derecho a pisotear todas las normas, todos los principios y todos los valores.

El resultado está a la vista de todos. Puesto que las Cultura es un orden de valores, la ruina y desmoronamiento de la Cultura tiene por fuerza que traducirse en una ruina y desmoronamiento de los valores. Así vemos cómo en la civilización actual va quedando totalmente trastocada, e incluso invertida, la escala normal de los valores. Los verdaderos valores (la nobleza, la fidelidad, la lealtad, el heroísmo, el honor, el sentido del deber y la responsabilidad, la honradez, el decoro, la valentía, etc.), que hacen que la vida adquiera sentido y permiten que los seres humanos vivan una vida libre y feliz, se ven sustituidos por los antivalores o contravalores. La Verdad, el Bien, la Belleza y la Justicia ceden quedan desplazados y arrinconados por la mentira, el mal (y la maldad), la fealdad y la injusticia.

2) Ruina de la Comunidad

El triunfo de la Civilización sobre la Cultura, el ilegítimo predominio de los elementos civilizatorios sobre los culturales y espirituales, lleva consigo la implantación de determinadas formas de vida y articulación social que, por distanciarse del orden normativo y romper los equilibrios naturales, resultan fuertemente lesivas para el normal desarrollo de la vida humana.

La vida decae o desciende desde la plenitud de lo comunitario hasta la existencia problemática y conflictiva de lo societario.

La Comunidad, que es la forma sana y normal de articulación social --con una estructura orgánica y jerárquica, basada en realidades naturales, unida por lazos afectivos y sólidos vínculos, asentada en firmes principios y valores espirituales--, ha quedado hoy día completamente destruida por los efectos disolventes del individualismo, el racionalismo y el materialismo, así como por las tendencias igualitarias y niveladoras que se han ido imponiendo en la sociedad occidental. Ese conjunto de tendencias, corrientes y fenómenos típicos de la era moderna han acabado demoliendo el armazón intelectual, ideal y moral sobre el que se asienta la vida comunitaria.

Como un proceso paralelo al que ha ocasionado el desmoronamiento de la Cultura y su aplastamiento por la Civilización técnica y material, la Comunidad ha ido retrocediendo y dejando el puesto a la Sociedad, entendida como mero conglomerado de intereses, carente de los lazos vivos que caracterizan a la vida comunitaria. Es la sociedad anónima, típica expresión civilizatoria: la sociedad desprincipiada, con estructura inorgánica, basada en abstracciones y unida por relaciones contractuales, tan frágiles como efímeras, cuando no por la fuerza y la coerción de un poder político dotado de un eficaz aparato burocrático y represivo.

El sistema societario tiende a socavar las realidades naturales en las que se apoya la vida humana para reemplazarlas por esquemas de inspiración racionalista, con lo cual la vida social queda empobrecida, desnaturalizada, confusa y seriamente tocada. Bajo este sistema el funcionamiento de la sociedad se halla completamente regido por construcciones, ideas y teorías abstractas, en extremo artificiosas, carentes de base real y natural, como el dinero, los bancos, la economía financiera, la Bolsa de valores, los partidos políticos y las formulaciones ideológicas. Todo queda supeditado y sacrificado a los impulsos, las decisiones y las directrices que emanan de semejante estructura hecha de abstracciones.

No es de extrañar que en el mundo actual, bajo la presión de las tendencias civilizatoria y societaria, las formas comunitarias vayan desapareciendo

o atraviesen una grave crisis que las hace verse seriamente amenazadas. Todas ellas experimentan el mismo retroceso, el mismo proceso desintegrador, que parece anunciar su definitiva extinción: desde la familia a la empresa, desde la región a la comunidad nacional, desde la amistad (las relaciones amistosas) a las órdenes religiosas y las comunidades monásticas. Los esquemas societarios se van imponiendo de forma arrolladora en todas partes.

En la Comunidad priman los deberes sobre los derechos. Las personas que la integran (que no son meros individuos ni actúan como tales) dan más importancia a sus deberes que a sus derechos. Saben que los deberes que tienen hacia los demás y hacia la Comunidad en cuanto tal es lo que les permite realizarse como personas. En una civilización individualista, que pone un énfasis excesivo o casi exclusivo en los derechos, los deberes pasan a un segundo plano, si es que no desaparecen por completo. Hoy se habla incluso de “una sociedad sin deber”, considerando tal aberración como una gran conquista social e histórica, la cima de la evolución progresista de la Humanidad.

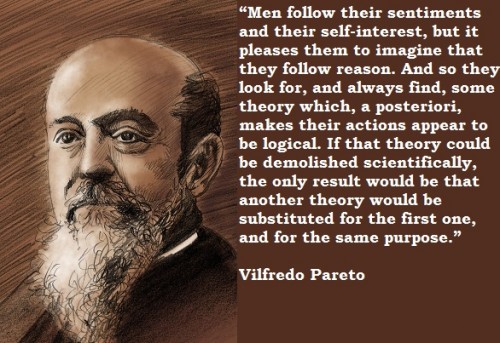

Si la Comunidad afirma, fomenta y cultiva todo lo que es calidad y cualidad, es decir, los elementos cualitativos de la existencia, que son aquellos que van ligados a los más altos valores, a lo esencial, espiritual y principial (los principios rectores, inspiradores y orientadores de la vida), la Sociedad da primacía absoluta a la cantidad, a los factores cuantitativos, lo puramente material, lo que se puede medir y pesar, comprar y vender. El mundo societario es el imperio de la cantidad: lo cuantitativo se impone por doquier. De ahí que en su seno adquiera un especial relieve y protagonismo todo lo relacionado con la economía, con la actividad mercantil y productiva (con su contrapartida consumidora o consumista). Lo que manda es el número, la masa, la decisión de las mayorías, la producción masiva, las grandes cifras y los datos estadísticos.

Si la Comunidad significa unidad, armonía, concordia y cordialidad, la Sociedad genera desunión, división, desarmonía, enfrentamiento y discordia. La Comunidad, al insertarse en el orden natural, al estar animada por el amor, al respetar las leyes de la vida y cultivar los factores cualitativos de la existencia, favorece la unión y la integración de los seres humanos. En la fase societaria, por el contrario, se acentúan las tendencias disgregadoras y desintegradoras, se multiplican los conflictos y las tensiones: lucha de clases, enfrentamiento entre partidos y sectas, pugna entre sexos, hostilidad entre generaciones, conflictos raciales y étnicos. Se exalta la agresividad y la competitividad por encima de todo, se proclama la lucha contra la religión llegando incluso a la persecución religiosa. Los choques violentos y las acciones perturbadoras (huelgas, manifestaciones, motines, altercados callejeros, atentados, actos vandálicos, amenazas y agresiones) están a la orden del día.

Al distanciarse del orden natural, el sistema societario introduce fuertes desequilibrios que afectan tanto a la vida colectiva como a la vida íntima de los individuos. Al descuidarse o abandonarse el cultivo de los valores, que únicamente es posible en una auténtica Comunidad y en una verdadera Cultura, la vida social se ve desgarrada por una brutal efervescencia de toda clase de partidismos y sectarismos, de particularismos y separatismos. La existencia de los grupos sociales experimenta agudas conmociones anímicas, hábilmente atizadas por los demagogos y agitadores que proliferan en el clima societario. No hay nada en este clima inhóspito y enrarecido que permanezca estable, sereno, aquietado y en paz.

Únicamente en el sistema societario podría tener lugar el auge de fenómenos como el colectivismo, el capitalismo, el nacionalismo, el politicismo y el totalitarismo. Así, en el campo económico, que tanta importancia adquiere en dicho sistemas, la ruina de la Comunidad acarrea el despotismo del Capital, como mero instrumento de poder material, el cual por la propia lógica de las cosas, como visceral enemigo de la verdadera propiedad, acaba asfixiando y desplazando a la propiedad personal y comunitaria (comunal, gremial, etc.), lo que no hace sino contribuir a proletarizar amplias capas de la población. Algo semejante ocurre con la invasión de la política, que pretende afirmarse como valor supremo en la jerarquía de valores y que, por las tendencias centralistas y absorbentes del sistema societario, se enseñorea de todos los ámbitos de la existencia.

Al quedar privado del clima comunitario, que es el suelo natural sobre el que crece y se desarrolla la vida personal, pues ofrece orientación, apoyo, cobijo y protección, los seres humanos se encuentran desvalidos, alienados, anulados, extraviados, desconcertados, aislados y desorientados. Y como consecuencia, acaban siendo víctimas de fuerzas irracionales, negativas y caóticas, que el sistema societario no logra dirigir, frenar ni controlar, y, peor aún, ni siquiera acierta a entender. Y por supuesto, quedan a merced de los poderes fácticos que gobiernan y dominan la vida social, siendo manipulados y esclavizados mientras sus oídos son acariciados con bellos lemas sobre la libertad y los derechos humanos de que gozan gracias al sistema bajo el que viven.

En la dura jungla humana que es la atmósfera societaria nos vemos cada vez más sometidos a la tiranía de fuerzas, instancias, influencias y potencias anónimas que son radicalmente hostiles a la realidad humana y personal, y sobre las cuales no tenemos ni podemos tener ninguna influencia: la masa, las máquinas y los mecanismos, el dinero, la finanza internacional, los mercados, las ideologías, la propaganda y los medios de adoctrinamiento masivo, los poderes supra-nacionales, la tecnocracia, los potentes resortes de una opresiva estructura civilizatoria, la religión laica mundialista y la dictadura del pensamiento único (con su correspondiente aparato inquisitorial, su cohorte de intelectuales “orgánicos” y su eficacísima policía del pensamiento), la maquinaria burocrática y partitocrática; y, finalmente, como colofón y resumen de tan amplia panoplia, un sistema político-ideológico que trata de invadir y controlar todo.

Este anormal desarrollo, este ambiente inhumano, da lugar a toda clase de enfermedades psicosomáticas, así como al gran problema de las adicciones, que no hacen sino esclavizar más aún a los individuos. La ruina de la Comunidad y la imposición de los fríos esquemas societarios han hecho surgir asimismo esa especie de dolencia social que es la soledad, verdadero flagelo de la moderna civilización individualista. Basta leer el interesante libro de David Riesmans “La muchedumbre solitaria” (The lonely crowd), que contiene una lúcida y aterradora descripción de la sociedad norteamericana

3) Ruina de la Persona

El ser humano no puede desarrollarse plenamente como persona sin la Cultura y sin la Comunidad. Necesita de ambas para gozar de una vida plena, sana, noble y digna, libre y feliz. He aquí tres conceptos que van inseparablemente unidos: Persona, Comunidad y Cultura. De la misma forma que se hallan ligados entre sí los tres conceptos antagónicos: Individuo, Sociedad (sociedad anónima o fenómeno societario) y Civilización (fenómeno o sistema civilizatorio).

Sin el apoyo, la protección y la savia nutricia que le brindan Cultura y la Comunidad resulta sumamente difícil que pueda darse la vida personal, lo que es tanto como decir la vida auténticamente humana. Quedando huérfano de esas dos fuerzas maternales y formativas, el ser humano está condenado a vivir encerrado en el mundo oprimente y problemático de la individualidad. Pero esta es la situación con la que nos encontramos en el actual clima societario y civilizatorio.

En la civilización materialista, anticomunitaria y anticultural, en la que vivimos nos encontramos con una auténtica ofensiva antipersonal: un ataque despiadado a todo lo que suponga vida personal, intimidad e interioridad, propia identidad, personalidad, carácter, autonomía y poder de decisión de la persona, ley y vocación propias (svadharma), dignidad y libertad interior del ser humano, relaciones interpersonales. La persona y el mundo de lo personal aparecen como el enemigo a abatir. Un obstáculo para la consolidación de lo que Hilaire Belloc llamaba “el Estado servil”; o sea, un escollo insalvable para la instauración de un régimen de general expropiación, de servidumbre y esclavitud.

Avanzan y se imponen de modo tan implacable como imparable los procesos de despersonalización, masificación y gregarismo, proletarización (que se ve acentuada por la destrucción de la clase media que está ocasionando la actual crisis económica), deshumanización de la formas de vida y de las relaciones sociales, asfixia e incluso desaparición de la vida íntima, cosificación o reificación de los seres humanos, banalización y anulación de las personas, que quedan convertidas en máquinas, en simples números o entes atomizados. Todo ello estrechamente ligado a la degradación de la Cultura y al avance de los procesos civilizatorios y societarios de los que antes hemos hablado.

El mundo actual es un campo minado para lo personal y espiritual, sembrado de infinidad de auténticas minas antipersona (algunas manifiestas y bien visibles, otras muchas ocultas y no fáciles de detectar o localizar). Al sistema societario y a los poderes que lo controlan les interesan individuos sin personalidad, débiles de carácter, sin convicciones y sin vocación, sin una clara conciencia de la propia identidad y con una vida personal inconsistente, estúpidos, abúlicos y desmemoriados, pues son los que más fácilmente pueden ser manipulados y sometidos.

En lugar de la Persona, que es el ser humano guiado por unos firmes principios, comprometido en la conquista de valores y la realización de una misión vital, movido por una profunda vocación, con una actitud responsable y un alto sentido de servicio, se impone el individuo, el ser humano como entidad numérica, átomo social, un simple miembro del rebaño o de la horda, sin normas ni principios, desarraigado y sin vínculos, guiado por simples consideraciones egoístas o egocéntricas: hace lo que le da la gana, no tiene en cuenta más que su propia opinión y sus propios intereses.

Como apunta Denis de Rougemont, el individuo, que el Liberalismo ha erigido en ídolo, es “el hombre aislado, un hombre sin destino, un hombre sin vocación ni razón de ser, un hombre al cual el mundo no exige nada”. Y en la misma línea se expresa Emmanuel Mounier, para quien el individuo está en los antípodas de la Persona; pues “individualidad” significa dispersión y avaricia, afán de poseer y acumular, evasión y cerrazón, “multiplicidad desordenada e impersonal”. El individuo, por lo que a mi propio ser se refiere --añade Mounier--, es “la disolución de mi Persona en la materia”: objetos, fuerzas, actividades, influencias entre las que me muevo. Lo individual no es más que “una fragmentación de lo anónimo”.

La Comunidad va inseparablemente unida a la Persona, a la idea de Personalidad, entendida como el más alto ser y la esencia misma del sujeto humano. Personalidad y Comunidad son los dos polos en torno a los cuales se articula la vida humana cuando está en plena forma, cuando goza de salud y se halla en un estado de normalidad. La Sociedad, en cambio, tiene como contrapartida al individuo, en cuanto sujeto indiferenciado y anónimo, con una existencia pre-personal o sub-personal, cuya actividad vital tiende incluso a orientarse contra la vida personal y contra todo aquello que la hace posible. Mundo individual y mundo societario, individualidad y sociedad, se exigen recíprocamente, de la misma forma que se exigen y complementan entre sí Personalidad y Comunidad.

Esto es lo que nos encontramos en el mundo actual, la ley suprema que lo rige y que inspira la mentalidad del hombre de nuestros días. Es el imperio del individualismo, que lo corroe todo al proclamar que no hay nada por encima de la razón y la voluntad individuales, y que el valor supremo son los sacrosantos derechos del individuo (reales o ficticios), la libertad individual (que cada cual pueda hacer lo que se le antoje) y el libre juego de los intereses individuales.

Ni que decir tiene que el colectivismo, en sus más diversas formas (ya sea socialista, comunista, anarquista, feminista, ecologista, nacionalista, racista o de cualquier otro tipo) no es sino una derivación de semejante tendencia individualista, pues en su centro se halla siempre la divinización del individuo, aun cuando se trate del macro-individuo colectivo. Este radical y corrosivo individualismo, sea cual sea la modalidad que presente, es el que está llevando al abismo a Europa y al Occidente.

4) Construcción de la Persona

Cualquier intento de superar la decadencia actual y dar respuesta a la terrible crisis que sufrimos ha de iniciarse en el ámbito de la vida personal.

Aquí está la clave de todo. La construcción o regeneración de la Comunidad y de la Cultura debe empezar por la construcción del hombre, la edificación de la Persona. No será posible avanzar en la empresa regeneradora o revolucionaria constructiva y positiva mientras no se hay emprendido esta labor, ardua y exigente, pero al mismo apasionante, la más fascinante que pueda imaginarse.

La superación del actual desorden requiere, como primer paso, como condición imprescindible y sine qua non, la superación del desorden interno (e incluso externo) que cada cual porta en su propio vivir personal (que más bien es anti-personal o des-personal, pues resulta gravemente despersonalizante). Lo prioritario es la edificación y renovación de nuestra propia persona, la formación y articulación de nuestro propio mundo personal. Una tarea que hay que tomarse muy en serio y que nos incumbe a todos sin excepción. En este sentido, constituye un imperativo de la mayor altura y relevancia el formarse, el cultivarse, el darse una buena y sólida cultura, el trabajarse de forma metódica y con una estricta disciplina.

Cobra aquí una importancia capital la Cultura como camino para la forja de la persona, como vía para la formación de un ser humano integral, como conjunto de medios que permite formar hombres y mujeres íntegros, cabales, dueños de sí mismos, capaces de afrontar su vida y su destino con dignidad, libertad y nobleza. Capaces asimismo de forjar un mundo mejor, por su sentido del deber, del honor y de la responsabilidad.

Pero la Cultura únicamente puede ejercer de forma plena y eficaz esa función formadora o edificadora de la Persona cuando es concebida de manera integral, holística y completa, como un todo que abarca al ser humano en su totalidad, en cuanto ser compuesto de cuerpo, alma y espíritu. No se puede desconocer ninguna de estas tres dimensiones del ser humano si queremos lograr nuestro pleno desarrollo personal, consiguiendo la unidad y la armonía en nuestra propia vida. La Cultura nos ayudará a dar unidad a esas dimensiones que conforman nuestro ser.

El trabajarnos y cultivarnos debería ser nuestra primera preocupación, pues ahí están los cimientos sobre los que luego construir un proyecto serio, digno de ser tenido en cuenta y que pueda verse coronado por el éxito.

Para poder arreglar los problemas de la sociedad, primero tendremos que haber arreglado nuestros propios problemas personales. Para hacer algo digno y valioso hay que empezar por poner orden en el propio caos y desequilibrio personal, superar la propia incultura y poner fin a la anarquía mental, intelectual y anímica (temperamental, emotiva, sentimental, instintiva) en que solemos estar instalados, generalmente con una considerable dosis de satisfacción y autocomplacencia (encantados de habernos conocido y creyéndonos superiores a los demás, considerándonos poco menos que la élite del futuro).

¿Qué vamos a poder construir, realizar o conquistar en el plano político o social si somos unos ignorantes, si tenemos graves problemas psicológicos, si padecemos una total falta de madurez y de solidez interna? ¿Qué podremos dominar o liderar, si nos dominan nuestras emociones, si somos esclavos de nuestros estados de ánimo y de nuestras pulsiones más elementales?

La falta de una adecuada formación, la carencia de esa formación integral a la que hemos aludido, es fuente de problemas de toda índole. Sobre todo de problemas y males que arrancan de la mente, que afectan al alma o psique individual, y que desgarran desde dentro al individuo, produciendo fatales secuelas que luego no pueden menos de proyectarse al entorno en el que uno se mueve. Aquí está el núcleo del problema con el que tantas veces nos topamos, la causa o raíz de tantos fracasos, de tantos abandonos, de tantas decepciones y de tantos conflictos.

Lo que falla siempre, en el fondo, es la persona, el individuo, el sujeto concreto. Y falla precisamente por no haberse hecho auténtica persona, por haber quedado en cuasi-persona, en persona fallida, en persona sin hacer o a medio hacer.

Quien adolece de falta de formación o cultivo personal, quien no se halla suficientemente formado o cultivado, no estará en modo alguno preparado para afrontar los difíciles retos que plantea un momento histórico sumamente crítico como este que actualmente atravesamos y, por ello, difícilmente podrá ser un elemento valioso en ninguna empresa de reconstrucción que requiera un especial empeño combativo. Una era tan problemática como esta del Kali-Yuga en que nos encontramos --y además en su fase álgida, más destructiva-- nos somete a tremendas tensiones, nos expone a grandes peligros y tentaciones, y nos obliga por tanto a un mayor esfuerzo formativo.

Si hablamos, por ejemplo, de reconstruir la Comunidad, hay que partir de una verdad incontestable: la verdadera Comunidad empieza por uno mismo. Si queremos avanzar hacia el ideal de la realidad comunitaria, tendremos que comenzar por construir nuestra propia realidad personal. No será posible construir nada mientas nuestra propia vida íntima esté desintegrada, empobrecida, sin cultivar y sin formar, vacía de valores y de contenido. Como decía Emanuel Mounier, es “imposible llegar a la Comunidad esquivando a la Persona, asentar la Comunidad sobre otra cosa que personas sólidamente constituidas”.

La Persona viene a ser una comunidad en pequeño, una micro-comunidad, de la misma forma que es un micro-cosmos. Debe estar articulada internamente como una auténtica comunidad: constituyendo un todo orgánico y jerárquico, guiado por sólidos principios y asentada en altos valores éticos, con unidad y armonía entre todas sus partes. Pero todo esto es inviable, completamente irrealizable, sin una paciente y profunda labor cultural, formativa y educadora (auto-educadora). Ya Platón nos enseñó que el hombre es un Estado, una República o una Polis, en escala reducida, que después ha de proyectar su propia constitución comunitaria personal al Todo que configura la comunidad política.

Si las cosas están hoy día muy mal, si discurren por cauces tan preocupantes y funestos, es en gran parte debido a nuestras propias deficiencias, a nuestros errores y defectos personales. Por nuestra incapacidad y nuestra deficiente cualificación, somos responsables de lo que está pasando y de lo que va a pasar. Si nuestra sociedad se desintegra, si España, Europa y el mundo llevan la marcha que llevan, es porque no hemos sabido maniobrar como es debido para contrarrestar tal evolución. Y si no hemos sabido hacerlo, si no hemos acertado a realizar la acción o actividad que serían necesarias, es porque nuestro estilo vital, nuestra manera de ser, de actuar y de comportarnos dejan mucho que desear.

Urge tomar conciencia de tal realidad y obrar en consecuencia, con el máximo rigor, con valentía y decisión. Hay que corregir todo cuanto tenga que ser corregido y aprender cuanto haya de ser aprendido. Hay que emprender la indispensable labor cultural, educativa y formativa si queremos tener un legítimo protagonismo en las vicisitudes de nuestra época, dar una respuesta adecuada a los problemas de la sociedad en que vivimos y cumplir con nuestro deber en el momento histórico presente.

N’importe-t-il pas, avant toute chose, non pas d’agir, mais de comprendre le sens de l’acte que l’on va accomplir ? Savoir distinguer est à la fois le premier signe de l’intelligence et le premier échelon de l’éthique. Connaître l’origine, la cause, de la maladie, c’est à quoi s’applique le médecin. De son diagnostic ne dépend pas la guérison, mais la possibilité de choisir une médication appropriée à la nature du mal.

N’importe-t-il pas, avant toute chose, non pas d’agir, mais de comprendre le sens de l’acte que l’on va accomplir ? Savoir distinguer est à la fois le premier signe de l’intelligence et le premier échelon de l’éthique. Connaître l’origine, la cause, de la maladie, c’est à quoi s’applique le médecin. De son diagnostic ne dépend pas la guérison, mais la possibilité de choisir une médication appropriée à la nature du mal.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Comme je le dis parfois, nous vivons dans un présent permanent depuis environ deux siècles. Les années 1830 sont déjà notre société et nous ne les quitterons qu’à la prochaine comète qui s’écrasera sur notre vieille planète. Ce n’est pas un hasard. Le progrès et la blafarde modernité ont paralysé l’histoire de l’humanité. Pronostiquée par Hegel en 1806, la Fin de l’Histoire n’en finit pas de prendre son congé.

Comme je le dis parfois, nous vivons dans un présent permanent depuis environ deux siècles. Les années 1830 sont déjà notre société et nous ne les quitterons qu’à la prochaine comète qui s’écrasera sur notre vieille planète. Ce n’est pas un hasard. Le progrès et la blafarde modernité ont paralysé l’histoire de l’humanité. Pronostiquée par Hegel en 1806, la Fin de l’Histoire n’en finit pas de prendre son congé.

Recent books are hardly different. Louis Dupre’s The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture (2004), traces our current critically progressive attitudes back to the Enlightenment “ideal of human emancipation.” Dupré argues (from a perspective influenced by Jurgen Habermas) that the original project of the Enlightenment is linked to “emancipatory action” today (335). Gertrude Himmelfarb’s The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (2004), offers a neoconservative perspective of the British and the American “Enlightenments” contrasted to the more radical ideas of human perfectibility and the equality of mankind found in the French philosophes. She brings up Jefferson’s hope that in the future whites would “blend together, intermix” and become one people with the Indians (221). She quotes Madison on the “unnatural traffic” of slavery and its possible termination, and also Jefferson’s proposal that the slaves should be freed and sent abroad to colonize other lands as “free and independent people.” She implies that Jefferson thought that sending blacks abroad was the most humane solution given the “deep-rooted prejudices of whites and the memories of blacks of the injuries they had sustained” (224).

Recent books are hardly different. Louis Dupre’s The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture (2004), traces our current critically progressive attitudes back to the Enlightenment “ideal of human emancipation.” Dupré argues (from a perspective influenced by Jurgen Habermas) that the original project of the Enlightenment is linked to “emancipatory action” today (335). Gertrude Himmelfarb’s The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (2004), offers a neoconservative perspective of the British and the American “Enlightenments” contrasted to the more radical ideas of human perfectibility and the equality of mankind found in the French philosophes. She brings up Jefferson’s hope that in the future whites would “blend together, intermix” and become one people with the Indians (221). She quotes Madison on the “unnatural traffic” of slavery and its possible termination, and also Jefferson’s proposal that the slaves should be freed and sent abroad to colonize other lands as “free and independent people.” She implies that Jefferson thought that sending blacks abroad was the most humane solution given the “deep-rooted prejudices of whites and the memories of blacks of the injuries they had sustained” (224). Actually, Kant, the greatest thinker of the Enlightenment, “produced the most profound raciological thought of the 18th century.” These words come from Earl W. Count’s book This is Race, cited by Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze in what is a rather good analysis of Kant’s racism showing that it was not marginal but deeply embedded in his philosophy. Eze’s analysis comes in a chapter, “

Actually, Kant, the greatest thinker of the Enlightenment, “produced the most profound raciological thought of the 18th century.” These words come from Earl W. Count’s book This is Race, cited by Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze in what is a rather good analysis of Kant’s racism showing that it was not marginal but deeply embedded in his philosophy. Eze’s analysis comes in a chapter, “

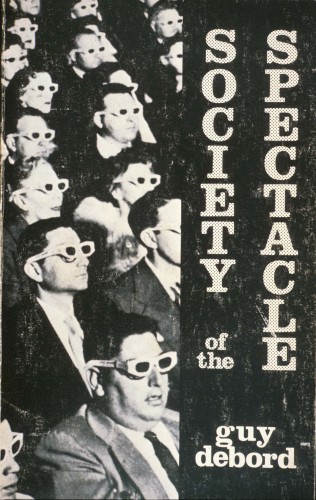

Debords Beschreibung der Totalität des Fetischismus und der Ware beginnt in unmittelbarer Anlehnung an das Marxsche "Kapital", dessen ersten Satz er paraphrasiert: "Das ganze Leben der Gesellschaften, in welchen die modernen Produktionsbedingungen herrschen, erscheint als eine ungeheure Sammlung von Spektakeln." (13) Eine explizit feststehende Definition des Begriffs Spektakel gibt Debord in seiner Schrift von 1967 nicht. Er umkreist ihn vielmehr und beschreibt ihn in seinen realen Erscheinungen und ex negativo. Im Begriff des Spektakels ist bei Debord der Begriff des Kapitals, wenn auch gegenüber der Marxschen Herleitung in vereinfachter Form, und der des Fetischismus aufgehoben: "Das Spektakel ist das Kapital in einem solchen Grad der Akkumulation, daß es zum Bild wird." (27) Er begreift das Spektakel als gesteigerte Form des Fetischismus: "Das Prinzip des Warenfetischismus ist es, (...), das sich absolut im Spektakel vollendet, wo die sinnliche Welt durch eine über ihr schwebende Auswahl von Bildern ersetzt wird, welche sich zugleich als das Sinnliche schlechthin hat anerkennen lassen." (31f.) Marx hat die Verwandlung menschlicher Beziehungen in die Beziehungen von Dingen beschrieben. Debord greift dies auf und beschreibt die Verwandlung der menschlichen Beziehungen in die Beziehung zwischen Bildern,10 die den Menschen noch äußerlicher erscheinen als die Dinge. Anders als in einigen postmodernen Diskursen hingegen, die dazu tendieren, alles in Bilder aufgelöst zu sehen, und die daher keine Realität mehr kennen, die in ihrer Gesamtheit kritisiert werden könnte, bleibt das Bild bei Debord auf die gesellschaftliche fetischistische Totalität, auf die materielle Realität rückbezogen.

Debords Beschreibung der Totalität des Fetischismus und der Ware beginnt in unmittelbarer Anlehnung an das Marxsche "Kapital", dessen ersten Satz er paraphrasiert: "Das ganze Leben der Gesellschaften, in welchen die modernen Produktionsbedingungen herrschen, erscheint als eine ungeheure Sammlung von Spektakeln." (13) Eine explizit feststehende Definition des Begriffs Spektakel gibt Debord in seiner Schrift von 1967 nicht. Er umkreist ihn vielmehr und beschreibt ihn in seinen realen Erscheinungen und ex negativo. Im Begriff des Spektakels ist bei Debord der Begriff des Kapitals, wenn auch gegenüber der Marxschen Herleitung in vereinfachter Form, und der des Fetischismus aufgehoben: "Das Spektakel ist das Kapital in einem solchen Grad der Akkumulation, daß es zum Bild wird." (27) Er begreift das Spektakel als gesteigerte Form des Fetischismus: "Das Prinzip des Warenfetischismus ist es, (...), das sich absolut im Spektakel vollendet, wo die sinnliche Welt durch eine über ihr schwebende Auswahl von Bildern ersetzt wird, welche sich zugleich als das Sinnliche schlechthin hat anerkennen lassen." (31f.) Marx hat die Verwandlung menschlicher Beziehungen in die Beziehungen von Dingen beschrieben. Debord greift dies auf und beschreibt die Verwandlung der menschlichen Beziehungen in die Beziehung zwischen Bildern,10 die den Menschen noch äußerlicher erscheinen als die Dinge. Anders als in einigen postmodernen Diskursen hingegen, die dazu tendieren, alles in Bilder aufgelöst zu sehen, und die daher keine Realität mehr kennen, die in ihrer Gesamtheit kritisiert werden könnte, bleibt das Bild bei Debord auf die gesellschaftliche fetischistische Totalität, auf die materielle Realität rückbezogen.  Die Praxis des Proletariats als revolutionäre Klasse kann für Debord "nicht weniger sein als das geschichtliche Bewußtsein, das auf die Totalität seiner Welt wirkt." (64) Damit ist aber noch nichts darüber gesagt, ob das Proletariat als real existierende und zunächst nicht besonders revolutionäre Klasse dieses geschichtliche Bewußtsein auch hat. Dennoch bleibt für Debord — zumindest noch in "Die Gesellschaft des Spektakels" — das Proletariat jene Menschengruppe, die als Klasse die Emanzipation zu verwirklichen, den Fetischismus zu durchbrechen und aufzuheben hat. Subjektiv sei das Proletariat "noch von seinem praktischen Klassenbewußtsein entfernt (...)." (102) Wenn aber das Proletariat entdeckt, "daß seine geäußerte eigene Kraft zur fortwährenden Verstärkung der kapitalistischen Gesellschaft beiträgt, (...) entdeckt es auch durch die konkrete geschichtliche Erfahrung, daß es die Klasse ist, die jeder erstarrten Äußerung und jeder Spezialisierung der Macht total feind ist." (102f.) Debord ist Ende der 60er Jahre kritisch gegenüber dem gegenwärtigen Proletariat, aber durchaus zuversichtlich für die Zukunft. Die Emanzipation wird bei ihm noch mit dem Selbstbewußtsein des Proletariats zusammengedacht. Das Proletariat erschien Debord kurz vor den Ereignissen des Pariser Mai von 1968 als "einzige(r) Bewerber um das geschichtliche Leben". (72) Erst später, in den 90er Jahren, erkannte er, auch wenn er sich von der Vorstellung vom Proletariat als Vollender der Emanzipation nicht gänzlich verabschiedete, daß die Klassenherrschaft, wie er in der Vorrede zur dritten französischen Ausgabe von "Die Gesellschaft des Spektakels" formuliert, "mit einer Versöhnung geendet hat" (8), daß also das Proletariat, statt die Feindschaft zu Staat und Kapital zu entwickeln, auf die volle Integration in das fetischistische Warenspektakel gesetzt hat und die falsche Totalität der Gesellschaft nunmehr ohne Negation, ohne Einspruch existiert. In den "Kommentaren" ist jener kritische Pessimismus, der auch die Texte anderer Gesellschaftskritiker seit dem Nationalsozialismus prägte, in potenzierter Form und mit den in solchen Zusammenhängen offensichtlich obligatorischen Übertreibungen anwesend: "Zum ersten Mal im modernen Europa versucht keine Partei oder Splittergruppe auch bloß vorzugeben, sie wolle es wagen, etwas von Belang zu ändern. (...) Es ist ein für alle Mal geschehen um jene beunruhigende Konzeption, die mehr als zweihundert Jahre vorgeherrscht hat und derzufolge man eine Gesellschaft kritisieren oder ändern, sie reformieren oder revolutionieren kann." (213)

Die Praxis des Proletariats als revolutionäre Klasse kann für Debord "nicht weniger sein als das geschichtliche Bewußtsein, das auf die Totalität seiner Welt wirkt." (64) Damit ist aber noch nichts darüber gesagt, ob das Proletariat als real existierende und zunächst nicht besonders revolutionäre Klasse dieses geschichtliche Bewußtsein auch hat. Dennoch bleibt für Debord — zumindest noch in "Die Gesellschaft des Spektakels" — das Proletariat jene Menschengruppe, die als Klasse die Emanzipation zu verwirklichen, den Fetischismus zu durchbrechen und aufzuheben hat. Subjektiv sei das Proletariat "noch von seinem praktischen Klassenbewußtsein entfernt (...)." (102) Wenn aber das Proletariat entdeckt, "daß seine geäußerte eigene Kraft zur fortwährenden Verstärkung der kapitalistischen Gesellschaft beiträgt, (...) entdeckt es auch durch die konkrete geschichtliche Erfahrung, daß es die Klasse ist, die jeder erstarrten Äußerung und jeder Spezialisierung der Macht total feind ist." (102f.) Debord ist Ende der 60er Jahre kritisch gegenüber dem gegenwärtigen Proletariat, aber durchaus zuversichtlich für die Zukunft. Die Emanzipation wird bei ihm noch mit dem Selbstbewußtsein des Proletariats zusammengedacht. Das Proletariat erschien Debord kurz vor den Ereignissen des Pariser Mai von 1968 als "einzige(r) Bewerber um das geschichtliche Leben". (72) Erst später, in den 90er Jahren, erkannte er, auch wenn er sich von der Vorstellung vom Proletariat als Vollender der Emanzipation nicht gänzlich verabschiedete, daß die Klassenherrschaft, wie er in der Vorrede zur dritten französischen Ausgabe von "Die Gesellschaft des Spektakels" formuliert, "mit einer Versöhnung geendet hat" (8), daß also das Proletariat, statt die Feindschaft zu Staat und Kapital zu entwickeln, auf die volle Integration in das fetischistische Warenspektakel gesetzt hat und die falsche Totalität der Gesellschaft nunmehr ohne Negation, ohne Einspruch existiert. In den "Kommentaren" ist jener kritische Pessimismus, der auch die Texte anderer Gesellschaftskritiker seit dem Nationalsozialismus prägte, in potenzierter Form und mit den in solchen Zusammenhängen offensichtlich obligatorischen Übertreibungen anwesend: "Zum ersten Mal im modernen Europa versucht keine Partei oder Splittergruppe auch bloß vorzugeben, sie wolle es wagen, etwas von Belang zu ändern. (...) Es ist ein für alle Mal geschehen um jene beunruhigende Konzeption, die mehr als zweihundert Jahre vorgeherrscht hat und derzufolge man eine Gesellschaft kritisieren oder ändern, sie reformieren oder revolutionieren kann." (213) Einer wollte den Führer führen. Nein: Einige wollten den Führer führen und wirkten so im Zeichen des Führers. Ob Heidegger, Rosenberg oder Spann, die Qualität ihrer Beiträge bleibt in diesem Kontext sekundär, wenn auch im Sinne der üblichen Vorwegnahme bei Spann die Betonung auf der philosophischen Stupidität liegen kann. Ihm gelang jedoch die Formierung eines Kreises, der mehr als sechzig Jahre nach seiner eigenen Entfernung von der Universität, der heutigen WU-Wien, das Gewäsch von Ganzheit wiederholt und daneben peinlich bemüht wirkt, keinen runden Geburtstag des Meisters oder seines ersten Schülers, manchmal auch des zweiten oder folgender, zu vergessen und zumeist mit einem Presseartikel, besser mit einem Jubiläumsband zu bedenken.

Einer wollte den Führer führen. Nein: Einige wollten den Führer führen und wirkten so im Zeichen des Führers. Ob Heidegger, Rosenberg oder Spann, die Qualität ihrer Beiträge bleibt in diesem Kontext sekundär, wenn auch im Sinne der üblichen Vorwegnahme bei Spann die Betonung auf der philosophischen Stupidität liegen kann. Ihm gelang jedoch die Formierung eines Kreises, der mehr als sechzig Jahre nach seiner eigenen Entfernung von der Universität, der heutigen WU-Wien, das Gewäsch von Ganzheit wiederholt und daneben peinlich bemüht wirkt, keinen runden Geburtstag des Meisters oder seines ersten Schülers, manchmal auch des zweiten oder folgender, zu vergessen und zumeist mit einem Presseartikel, besser mit einem Jubiläumsband zu bedenken.

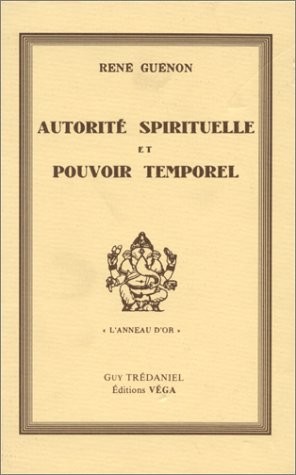

Pero más recientemente todavía y con motivo de la publicación consecutiva de las Memorias de Eliade, la perspectiva sobre la irradiación guenoniana se ha ampliado y así hemos tenido la oportunidad de leer un erudito artículo del estudioso italiano Cristiano Grottanelli, bajo el acápite de «Mircea Eliade, Carl Schmitt, René Guénon, 1942», en la Revue de l’Histoire des Religions Tome 219, fascículo 3, julio-septiembre 2002, pp. 325-356, que arroja nuevas luces y sombras sobre la cuestión claramente anticipada en el título y que amplia el panorama con la mención del gran jurista y experto en derecho internacional, Carl Schmitt, tan apreciado en los comienzos de los años 30 por el régimen nacionalsocialista, como posteriormente repudiado tanto por la SS y el nazismo que representaban, como por sus vencedores aliados.

Pero más recientemente todavía y con motivo de la publicación consecutiva de las Memorias de Eliade, la perspectiva sobre la irradiación guenoniana se ha ampliado y así hemos tenido la oportunidad de leer un erudito artículo del estudioso italiano Cristiano Grottanelli, bajo el acápite de «Mircea Eliade, Carl Schmitt, René Guénon, 1942», en la Revue de l’Histoire des Religions Tome 219, fascículo 3, julio-septiembre 2002, pp. 325-356, que arroja nuevas luces y sombras sobre la cuestión claramente anticipada en el título y que amplia el panorama con la mención del gran jurista y experto en derecho internacional, Carl Schmitt, tan apreciado en los comienzos de los años 30 por el régimen nacionalsocialista, como posteriormente repudiado tanto por la SS y el nazismo que representaban, como por sus vencedores aliados. En vísperas de Navidad del mismo año Eliade recibió Tierra y mar de parte de Schmitt, y Goruneanu le informa que el número 3 de Zalmoxis que había enviado a Schmitt lo acompañaba a Jünger en su mochila. Y esta triple relación de personas, directa, en un caso, e indirecta en el otro – por medio de la revista Zalmoxis-, se repite en 1944 y posteriormente. El primer caso se concretó por un nuevo encuentro de Schmitt -quien consideraba a Guénon: “El hombre más interesante de su tiempo” según señala Eliade en Fragmentos de Diario- con éste en Lisboa. En la visita de 1942, conjetura Grottanelli, de acuerdo con los testimonios de una simpatía recíproca de ambos personajes sobre Guénon, conversarían sobre él posiblemente no sólo como maestro sino también como teórico de la Tradición. El segundo encuentro a que nos hemos referido de Jürgen y Eliade y que nos interesa menos en este trabajo, llevó a que un tiempo después Jünger y Eliade dirigieran la revista Antaios.

En vísperas de Navidad del mismo año Eliade recibió Tierra y mar de parte de Schmitt, y Goruneanu le informa que el número 3 de Zalmoxis que había enviado a Schmitt lo acompañaba a Jünger en su mochila. Y esta triple relación de personas, directa, en un caso, e indirecta en el otro – por medio de la revista Zalmoxis-, se repite en 1944 y posteriormente. El primer caso se concretó por un nuevo encuentro de Schmitt -quien consideraba a Guénon: “El hombre más interesante de su tiempo” según señala Eliade en Fragmentos de Diario- con éste en Lisboa. En la visita de 1942, conjetura Grottanelli, de acuerdo con los testimonios de una simpatía recíproca de ambos personajes sobre Guénon, conversarían sobre él posiblemente no sólo como maestro sino también como teórico de la Tradición. El segundo encuentro a que nos hemos referido de Jürgen y Eliade y que nos interesa menos en este trabajo, llevó a que un tiempo después Jünger y Eliade dirigieran la revista Antaios. Nuevamente en este texto transparente están reunidas por Eliade las dos puntas de su posición de aceptación y crítica en relación con Guénon y otros autores vecinos por las ideas: simbolismo e ideas tradicionales garantizadores de la universalidad de las creencias sagradas como fondo organizador, pero a partir de la investigación científica. El reunir y avecinar documentos no es erudición positivista ni vacía, sino que en el allegamiento surgen ante la mente sensible y perspicaz a los fenómenos aproximadamente las ideas y principios transcendentes que subyacen. Las hierofanías, como manifestaciones de lo sagrado, revelan uniones o integraciones mediadoras que ligan a los contrarios –lo profano y lo sagrado- con equilibrio, lo organizan en sistemas estructurales en el lenguaje del símbolo y del mito, y permiten al alma religiosa arcaica y actual ascender a los orígenes constitutivos. No hay una diferencia insalvable acerca del reconocimiento del fondo espiritual entre Eliade y Guénon, sí lo hay en cuanto al método de acceso. Firmeza de la tradición y de la iniciación en cuanto a Guénon, ingreso por el reconocimiento de los fenómenos sagrados reflejados en la conciencia que cada vez exigen mayor comprensión, para Mircea Eliade. Guénon aspira a romper con lo profano para tener acceso no reflejo, sino directo a lo sagrado; Eliade, se sumerge en la dialéctica de lo sagrado y lo profano que acompaña a la vida del cosmos y la sociedad. Lo primero da una existencia digna de iniciados; lo segundo, de hombres en el mundo vitalmente sacro, que eligen diferentes destinos.

Nuevamente en este texto transparente están reunidas por Eliade las dos puntas de su posición de aceptación y crítica en relación con Guénon y otros autores vecinos por las ideas: simbolismo e ideas tradicionales garantizadores de la universalidad de las creencias sagradas como fondo organizador, pero a partir de la investigación científica. El reunir y avecinar documentos no es erudición positivista ni vacía, sino que en el allegamiento surgen ante la mente sensible y perspicaz a los fenómenos aproximadamente las ideas y principios transcendentes que subyacen. Las hierofanías, como manifestaciones de lo sagrado, revelan uniones o integraciones mediadoras que ligan a los contrarios –lo profano y lo sagrado- con equilibrio, lo organizan en sistemas estructurales en el lenguaje del símbolo y del mito, y permiten al alma religiosa arcaica y actual ascender a los orígenes constitutivos. No hay una diferencia insalvable acerca del reconocimiento del fondo espiritual entre Eliade y Guénon, sí lo hay en cuanto al método de acceso. Firmeza de la tradición y de la iniciación en cuanto a Guénon, ingreso por el reconocimiento de los fenómenos sagrados reflejados en la conciencia que cada vez exigen mayor comprensión, para Mircea Eliade. Guénon aspira a romper con lo profano para tener acceso no reflejo, sino directo a lo sagrado; Eliade, se sumerge en la dialéctica de lo sagrado y lo profano que acompaña a la vida del cosmos y la sociedad. Lo primero da una existencia digna de iniciados; lo segundo, de hombres en el mundo vitalmente sacro, que eligen diferentes destinos.

Pero, ¿cómo podría definirse la vida? ¿Qué es lo que la hace tan atractiva y valiosa?

Pero, ¿cómo podría definirse la vida? ¿Qué es lo que la hace tan atractiva y valiosa? En la vida humana es elemento esencial la dimensión trascendente. Siendo el hombre un ser espiritual, para que su vida discurra de forma sana, libre y feliz, tiene que dar a su vivir una orientación vertical, que lo proyecte hacia lo alto y tenga siempre en cuenta cuenta su fin último. La verticalidad del Espíritu ha de afirmarse por encima de la horizontalidad terrena, material, anímica y biológica, imprimiendo a esta última orden, sentido, mesura y armonía. Para vivir con dignidad y plenitud, el ser humano tiene que dar prioridad a su vida interior, que es la que le constituye como persona. Allí donde la vida se quede en lo exterior, en lo superficial, en lo puramente material, olvidando la dimensión espiritual, perderá en calidad, altura, salud y autenticidad.

En la vida humana es elemento esencial la dimensión trascendente. Siendo el hombre un ser espiritual, para que su vida discurra de forma sana, libre y feliz, tiene que dar a su vivir una orientación vertical, que lo proyecte hacia lo alto y tenga siempre en cuenta cuenta su fin último. La verticalidad del Espíritu ha de afirmarse por encima de la horizontalidad terrena, material, anímica y biológica, imprimiendo a esta última orden, sentido, mesura y armonía. Para vivir con dignidad y plenitud, el ser humano tiene que dar prioridad a su vida interior, que es la que le constituye como persona. Allí donde la vida se quede en lo exterior, en lo superficial, en lo puramente material, olvidando la dimensión espiritual, perderá en calidad, altura, salud y autenticidad. La civilización actualmente imperante, individualista, activista y materialista, desprincipiada, carente de principios y valores firmes, des-sacralizadora y profanadora de la realidad, se define por una pronunciada orientación antivida y por un impulso antivital. Odio a la vida, desprecio de la vida, miedo ante la vida, cansancio de vivir, náusea vital: estos vienen a ser los rasgos que resumen el tono existencial de la actual sociedad de masas dominada por la idolatría de lo efímero y contingente. Hay una evasión o huida de la vida que es consecuencia de lo que Max Picard llamó “la huida del Centro”, esto es, la huida o el alejamiento de Dios.

La civilización actualmente imperante, individualista, activista y materialista, desprincipiada, carente de principios y valores firmes, des-sacralizadora y profanadora de la realidad, se define por una pronunciada orientación antivida y por un impulso antivital. Odio a la vida, desprecio de la vida, miedo ante la vida, cansancio de vivir, náusea vital: estos vienen a ser los rasgos que resumen el tono existencial de la actual sociedad de masas dominada por la idolatría de lo efímero y contingente. Hay una evasión o huida de la vida que es consecuencia de lo que Max Picard llamó “la huida del Centro”, esto es, la huida o el alejamiento de Dios.