La genèse de la postmodernité

Robert STEUCKERS

Conférence prononcée à l'école des cadres du GRECE ("Cercle Héraclite"), juin 1989

Ex: http://vouloir.hautetfort.com/

La post-modernité. On en parle beaucoup sans trop savoir ce que c'est. Le mot fascine et mobilise quantité de curiosités, tant dans notre microcosme “néo-droitiste/ gréciste” (le néologisme est d'Anne-Marie Duranton-Crabol) (1) que dans d'autres.

La post-modernité. On en parle beaucoup sans trop savoir ce que c'est. Le mot fascine et mobilise quantité de curiosités, tant dans notre microcosme “néo-droitiste/ gréciste” (le néologisme est d'Anne-Marie Duranton-Crabol) (1) que dans d'autres.

Le fait de nous être nommés “Nouvelle Droite” ou d'avoir accepté cette étiquette qu'on nous collait sur le dos, signale au moins une chose : le terme “nouveau” indique une volonté de rénovation, donc un rejet radical du vieux monde, des idéologies dominantes et, partant, des modes de gestion pratiques, économiques et juridiques qu'elles ont produits. Dans ces idéologies dominantes, nous avons répété et dénoncé les linéaments d'universalisme, la prétention à déployer une rationalité qui serait unique et exclusive, ses implications pratiques de facture jacobine et centralisatrice, les stratégies homogénéisantes de tous ordres, les ratés dus aux impossibilités physiques et psychologiques de construire pour l'éternité, pour les siècles des siècles, une cité rationnelle et mécanique, d'asseoir sans heurts et sans violence un droit individualiste, etc.

Les avatars récents de la philosophie universitaire, éloignés — à cause de leur jargon obscur au premier abord — des bricolages idéologiques usuels, du tam-tam médiatique et des équilibrismes politiciens, nous suggèrent précisément des stratégies de défense contre cette essence universaliste des idéologies dominantes, contre le monothéisme des valeurs qui caractérise l'Occident tant dans son illustration conservatrice et religieuse — la New Right fondamentaliste l'a montré aux États-Unis — que dans son illustration illuministe, rationaliste et laïque. L'erreur du mouvement néo-droitiste, dans son ensemble, c'est de ne pas s'être mis plus tôt à l'écoute de ces nouveaux discours, de ne pas en avoir vulgarisé le noyau profond et d'avoir ainsi, dans une certaine mesure, raté une bonne opportunité dans la bataille métapolitique.

“Konservative Revolution” et École de Francfort

Il nous faut confesser cette erreur tactique, sans pour autant sombrer dans l'amertume et le pessimisme et brûler ce que nous avons adoré. En effet, notre recours direct à Nietzsche — sans passer par les interprétations modernes de son œuvre — au monde allemand de la tradition romantique, aux philosophies et sociologies organicistes/vitalistes et à la Konservative Revolution du temps de Weimar, a fait vibrer une corde sensible : celle de l'intérêt pour l'histoire, la narration, l'esthétique, la nostalgie fructueuse des origines et des archétypes (ici, en l'occurrence, les origines immédiates d'une nouvelle tradition philosophique). L'effort n'a pas été vain : en se dégageant du carcan rationaliste/positiviste, l'espace linguistique francophone s'est enrichi d'apports germaniques — organicistes et vitalistes — considérables, tout comme, dans la sphère même des idéologies dominantes, il apprenait à maîtriser simultanément les textes de base de l'École de Francfort (Adorno, Horkheimer) et les démonstrations audacieuses de Habermas, parce qu'il a parfois fallu 40 ou 50 ans pour trouver des traductions françaises sur le marché du livre.

Explorer les univers de Wagner, de Jünger, de Thomas Mann, de Moeller van den Bruck, de Heidegger, de Carl Schmitt (2), a donné, à notre courant de pensée, des assises historiques solidissimes et, à terme, une maîtrise sans a priori des origines philosophiques de toutes les pensées identitaires, maîtrise que ne pourront jamais détenir ceux qui ont amorcé leurs démarches dans le cadre des universalismes/rationalismes occidentaux ou ceux qui restent paralysés par la crainte d'égratigner, d'une façon ou d'une autre, les vaches sacrées de ces universalismes/rationalismes. Une plus ou moins bonne maîtrise des origines, découlant de notre méthode archéologique, nous assure une position de force. Mais cette position est corollaire d'une faiblesse : celle de ne pas être plongé dans la systématique contemporaine, de ne pas être sur la même longueur d'onde que les pionniers de l'exploration philosophique, de ne pas être en même temps qu'eux à l'avant-garde des innovations conceptuelles. D'où notre flanc se prête assez facilement à la critique de nos adversaires qui disent, sans avoir tout à fait tort : “vous êtes des passéistes, germanolâtres de surcroît”.

Comment éviter cette critique et, surtout, comment dépasser les blocages, les facilités, les paresses qui suscitent ce type de critique ? Se référer à la tradition romantique, avec son recours aux identités, opérer une quête du Graal entre les arabesques de la Konservative Revolution (KR), sont des atouts majeurs autant qu'enrichissants dans notre démarche. Si enrichissants qu'on ne peut en faire l'économie. Les prémisses du romantisme/vitalisme philosophique (mis en exergue par Gusdorf) (3), les fulgurances littéraires de leur trajectoire, la carrière inépuisable qu'est la KR, avec son esthétisme et sa radicalité, s'avèrent indispensables — sans pour autant être suffisants — afin de marquer l'étape suivante dans le développement de notre vision du monde. Jettons maintenant un coup d'œil sur le fond-de-monde où s'opèrent ce glissement, cette rénovation du substrat philosophique romantique/vitaliste, cette rénovation de l'héritage de la KR. En Allemagne, matrice initiale de ce substrat, l'après-guerre a imposé un oubli obligatoire de tout romantisme/vitalisme et conforté une vénération officielle, quasiment imposée, de la tradition adverse, celle de l'Aufklärung, revue et corrigée par l'École de Francfort. Hors de cette tradition, toute pensée est désormais suspecte en Allemagne aujourd'hui.

Devant la mise au pas de la philosophie en RFA, la bouée de sauvetage est française

Mais le perpétuel rabâchage des idéologèmes francfortistes et des traditions hégéliennes, marxistes et freudiennes a conduit la pensée allemande à une impasse. On assiste depuis peu à un retour à Nietzsche, à Schopenhauer (notamment à l'occasion du 200ème anniversaire de sa naissance en 1988), aux divers vitalismes. Mais ce simple retour, malgré la bouffée d'air qu'il apporte, demeure intellectuellement insuffisant. Les défis contemporains exigent un aggiornamento, pas seulement un approfondissement. Mais, si tout aggiornamento d'un tel ordre postule une réinterprétation de l'œuvre de Nietzsche et une nouvelle exploration de “l'irrationalisme” prénietzschéen, il postule aussi et surtout un nouveau plongeon dans les eaux tumultueuses de la KR. Or un tel geste rencontrerait des interdits dans la RFA d'aujourd'hui. Les philosophes rénovateurs allemands, pour sortir de l'impasse et contourner ces interdits, ces Denkverbote francfortistes, font le détour par Paris. Ainsi, les animateurs des éditions Merve de Berlin, Gerd Bergfleth, à qui l'on doit de splendides exégèses de Bataille, Bernd Mattheus et Axel Matthes (4) sollicitent les critiques de Baudrillard, la démarche de Lyotard, les audaces de Virilio, le nietzschéisme particulier de Deleuze, etc. La bouée de sauvetage, dans l'océan soft du (post-)francfortisme, dans cette mer de bigoterie rationaliste/illuministe, est de fabrication française. Et l'on rencontre ici un curieux paradoxe : les Français, qui sont fatigués des platitudes néo-illuministes, recherchent des médicaments dans la vieille pharmacie fermée qu'est la KR ; les Allemands, qui ne peuvent plus respirer dans l'atmosphère poussiéreuse de l'Aufklärung revue et corrigée, trouvent leurs potions thérapeutiques dans les officines parisiennes d'avant-garde.

Dès lors, pourquoi ceux qui veulent rénover le débat en France, ne conjugueraient-ils pas Nietzsche, la KR, la “droite révolutionnaire” française (révélée par Sternhell, stigmatisée par Bernard-Henri Lévy dans L'idéologie française, Grasset, 1981), Péguy, l'héritage des non-conformistes des années 30 (5), Heidegger, leurs philosophes contemporains (Foucault, Deleuze, Guattari, Derrida, Baudrillard, Maffesoli, Virilio), pour en faire une synthèse révolutionnaire ?

La présence de ces recherches nouvelles désamorcerait ipso facto les critiques qui mettent en avant le “passéisme” et la “germanolâtrie” de ceux et celles qui refusent d'adorer encore et toujours les vieilles lunes de l'âge des Lumières. De plus, cette présence autorise d'emblée une participation active et directe dans le débat philosophique contemporain, auquel une intervention néo-droitiste, portée par le souci pédagogique qui lui est propre, aurait sans doute conféré un langage moins hermétique. L'hermétisme du langage a été, de toute évidence, l'obstacle à l'incorporation des philosophes français contemporains dans un projet de nature métapolitique.

Dépasser l'humanisme, penser le pluriel

Il conviendrait donc, pour reprendre pleinement pied dans l'arène philosophique contemporaine ; de concilier 2 langages : d'une part, celui, didactique, narratif et historique qu'avait fait sien la ND dans les colonnes du Figaro Magazine, de Magazine-Hebdo ou d'Éléments et, d'autre part, un langage pionnier, prospectif, innovateur, celui des corpus deleuzien, foucaldien, etc. J'entends déjà les objections : Deleuze et Foucault s'inscrivent dans le cadre de la gauche intellectuelle, militent dans les réseaux “anti-racistes”, se font les apologistes des marginalités les plus bizarres, etc. Entre les opinions personnelles amplifiées par les médias, les engouements légitimes pour telle ou telle marginalité, et une épistémologie, exprimée dans un vocabulaire spécialisé et ardu, il faut savoir faire la distinction.

L'idée du dépassement de l'humanisme mécaniciste/rationaliste et la vision du surhumanisme nietzschéen (6) ont pourtant plus d'un point commun, preuve que les intuitions et les aphorismes de Nietzsche, les visions et les proclamations des autres auteurs de la tradition “surhumaniste”, se sont capillarisées dans les circuits intellectuels européens et ne pourront plus jamais en être délogés, en dépit des efforts lancinants de leurs adversaires, accrochés déséspérément à leurs vieilles chimères. Si la ND a ouvertement démasqué les hypocrisies des discours dominants, signalé les simulacres et déchiré les voiles, des philosophes comme Deleuze ont habilement camouflé leur travail de sape, si bien qu'il peut apparaître inattendu d'apprendre que, pour lui, le mouvement des droits de l'homme cherche naïvement à « reconstituer des transcendances ou des universaux ». Mais pour le philosophe de la “polytonalité” et des “multiplicités” — qui a pensé le pluriel de façon radicalement autre que la ND, mais a néanmoins aussi pensé le pluriel — est-ce si étonnant ?

Classer les courants post-modemes

Mais ces réflexions sur le destin de la ND et sur les philosophes français pourraient s'éterniser à l'infini, si l'on ne définit pas clairement un cadre historique et chronologique où elle s'inscriront, si l'on ne panoramise pas les faits post-modernes de philosophie et les virtualités qui en découlent. Il est en effet nécessaire de se doter d'un canevas didactique, afin de ne pas glosser dans le désordre et la confusion. Toutes les introductions à la pensée et aux philosophies postmodernes commencent par en souligner l'hétérogénéité, la diversité, l'absence de dénominateur commun : toutes caractéristiques qui, de prime abord, interdisent la clarté... Une chatte n'y retrouverait pas ses jeunes... Heureusement, un homme quasi providentiel est venu mettre de l'ordre dans ce désordre : Wolfgang Welsch, auteur d'un ouvrage “panoramique” sur la question, d'où ressort, limpide, une vision de l'histoire intellectuelle post-moderne (Unsere postmoderne Moderne, Acta Humaniora, Weinheim, 1987 ; en abrégé pour la suite du présent exposé : UPM).

Car c'est de cela qu'il s'agit : d'abord, montrer comment, progressivement, la philosophie s'est dégagée de la cangue rationaliste/moderniste/universaliste pour aborder le réel de façon moins étriquée, et, ensuite, indiquer à quel stade ce long cheminement est parvenu aujourd'hui, à quelles résistances têtues ce dégagement se heurte encore. Conseillant vivement une lecture de l'ouvrage de Welsch dans un article de Criticón, Armin Mohler, l'auteur de Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1919-1933, explique combien proche de notre anti-universalisme est l'interprétation welschienne de la post-modemité. De plus, la chronologie et la vision “panoramique” de Welsch, dévoilent l'évolution des idées, un peu comme on montre un processus biologique ou chimique en accéléré dans les documentaires scientifiques.

Posthistoire, postmodernité, société postindustrielle, une seule et même chose ?

Premier souci de Welsch : se débarrasser d'une confusion usuelle, celle qui dit que “posthistoire”, postmodernité et société postindustrielle sont une seule et même chose. Pour la posthistoire, décrite par Baudrillard, plus aucune innovation n'est possible et toutes les virtualités historiques ont été déjà jouées ; le diagnostic suggère la passivité, I'amertume, le cynisme et la grisaille.

Le mouvement du monde serait arrivé à un stade final, que Baudrillard nomme “l'hypertélie”, où les possibilités se neutraliseraient mutuellement dans “l'indifférence”, transformant notre civilisation en une gigantesque machinerie (la “mégamachine” de Rudolf Bahro ?) à homogénéiser toutes les “différences” produites par la vie. De ce fait, la texture du monde, qui consiste à produire des “différences”, se mue en un mode de production d'indifférence. En d'autres mots, la dialectique de la différenciation renverse ses potentialités en produisant de l'indifférence. Tout s'est déjà passé : inutile de rêver à une utopie, un monde meilleur, des lendemains qui chantent. Il ne se produit plus qu'une chose : le clonage infini et/ou la prolifération cancériforme du même, sans nouveauté, dans une “obésité obscène”. Notre époque, celle du “transpolitique”, ne travaille plus ses contradictions internes (ne cherche ni ne crée plus de solutions), mais s'engloutit dans l'extase de son propre narcissisme.

Le bilan de Baudrillard est sombre, noir. Son amertume, pense Welsch, est le signe de son hypermodernisme et non celui d'une éventuelle postmodernité. La faillite des utopies désole Baudrillard, alors qu'elle fait sourire les postmodernes. Baudrillard déplore l'évanouissement des utopies et accuse la postmodernité de ne plus avoir de dimension utopique. La postmodernité, elle, est active, optimiste, bigarrée, offensive ; elle n'est pas utopique, mais elle n'est pas non plus résignée et ne se lamente pas. Toute lamentation quant à la disparition des projets utopiques/modernes est la preuve d'un attachement sentimental et désillusionné aux affects qui soustendent la modernité.

Postmodemité et société postindustrielle

Pour réfuter les arguments de ceux qui posent l'équation “postmodernité = société postindustrielle”, Welsch commence par rappeler le moment où, en sociologie, le terme “postmoderne” est apparu pour la première fois. C'était en 1968, dans un ouvrage d'Amitai Etzioni : The Active Society : A Theory of Societal and Political Processes (New York). Pour Etzioni, la postmodernité ne signifie ni résignation devant l'effondrement des grandes utopies sociales, ni répétition du même à l'infini, sur le mode de la “mégamachine”. La postmodernité, au contraire, signifie dynamisme, créativité et action. Sur bon nombre de plans, l'analyse d'Etzioni rejoint les diagnostics de David Riesman (La foule solitaire, Arthaud, 1964 ; l'éd. am. date de 1958), d'Alain Touraine et surtout de Daniel Bell (Les contradictions culturelles du capitalisme, PUF, 1979 ; éd. am.: 1976). Mais, en dernière instance, les conclusions d'Etzioni et de Bell sont foncièrement différentes. Pour Bell, théoricien majeur de la société postindustrielle, le grand projet technocratique — faire le bonheur des masses par quantitativisme — demeure en place, même si l'on observe un passage des technologies machinistes aux technologies intellectuelles (informatique, p.ex.). Pour Etzioni, en revanche, les technologies les plus récentes relativisent le vieux projet technocratique. Pour Bell, nous sommes entrés dans un “stade final”, où il s'agit de mettre de l'ordre dans la société de masse, issue du “grand projet” technocratique. Pour Etzioni, nous glissons hors de la passivité technocratique pour entrer dans un âge “actif”, dans une société qui s'auto-définit et se transforme sans cesse.

Affronter efficacement le monde contemporain, pour Etzioni et Welsch, c'est savoir manier une pluralité de rationalités, de systèmes de valeurs, de projets sociaux et non se contenter d'une rationalité unique, d'un monothéisme des valeurs stérilisant et d'ériger en fétiche un et un seul modèle social. C'est face à cette offensive silencieuse d'un néo-pluralisme que Bell se trouve confronté à un dilemme qu'il ne peut résoudre : il sait que le projet technocratique, monolitihique dans son essence, ne peut satisfaire à long terme les aspirations démocratiques humaines, puisque celles-ci sont diverses ; mais, par ailleurs, on ne peut raisonnablement se débarrasser des acquis de l'ère technocratique, pense Bell, inquiet devant les nouveautés qui s'annoncent. Et face à ce complexe technocratique, composé de linéaments positifs et négatifs, indissociables et totalement imbriqués les uns dans les autres, s'est instaurée une sphère culturelle que Bell qualifie de “subversive”, car elle est hostile au projet technocratique et le sape. Le conflit majeur, qui risque de détruire la société capitaliste selon Bell, est celui qui oppose la sphère technique à la sphère culturelle. Cette opposition est, somme toute, assez manichéenne et ne perçoit pas qu'innovations sicentifiques/techniques et innovations culturelles/artistiques/littéraires surgissent d'un même fond de monde, d'une même révolution qui s'opère dans les mentalités. Arnold Gehlen, lui, avait bien vu que la culture (au sens où l'entend Bell), même hyper-critique à l'endroit de la mégamachine, n'était qu'épiphénomène et créatrice de gadgets, d'opportunités marchandes. La société marchande, la mégamachine bancaire et industrielle, récupèrent les velléités contestatrices et les transforment en marchandises consommables.

La postmodernité n'est ni le schéma catastrophiste de Bell ni le pessimisme de Gehlen et Baudrillard. Elle admet le caractère “radicalement disjonctif” des sociétés contemporaines. Elle admet, en d'autres mots, que les rationalités économiques, industrielles, politiques, culturelles et sociales sont différentes, parfois divergentes, et peuvent, très logiquement, mener à des conflits épineux. Mais la postmodernité, contrairement à la posthistoire ou à la société postindustrielle de Bell, n'évacue pas le conflit ni ne le déplore et accepte sa présence dans le monde, sans moralisme inutile.

Quelle modernité réfute la postmodernité ?

Si la postmodernité (PM) n'est ni la posthistoire ni la société postindustrielle, qu'est-elle et quelle modernité remplace-t-elle ? Les textes aussi nombreux que divers qui tentent de cerner l'essence de la PM, ne sont pas unanimes à désigner et définir cette modernité, qui, en toute logique, est chronologiquement antérieure à la PM. Plusieurs “modernités” sont concernées, nous explique Welsch ; d'abord celle de la Neuzeit (l'âge moderne, les Lumières, la “dialectique de la Raison”, etc.) ; Habermas s'insurge contre la PM, précisément parce qu'elle s'oppose au “grand projet de l'Aufklärung”, dans ses dimensions scientifiques comme dans ses dimensions morales. Karl Heinz Bohrer (7), pour sa part, estime que la PM réagit contre la modernité esthétique du XIXe. Pour Charles Jencks, le grand historien américain des mouvements en architecture (8), la PM (architecturale) est une réaction au rationalisme utilitariste et fonctionnaliste (Mies van der Rohe, École de Chicago) de l'architecture du XXe siècle. Mais Welsch préfère s'en tenir aux définitions de Jean-François Lyotard : la modernité, que dépasse la PM, a commencé avec le programme cartésien visant à soumettre la nature (les faits organiques) à un “projet géométrique”, pour se poursuivre, à un niveau philosophique et moral, dans les “grands récits” du XVIIIe et du XIXe (l'émancipation de l'Homme, la téléologie hégélienne de l'Esprit, etc.).

La définition de Lyotard

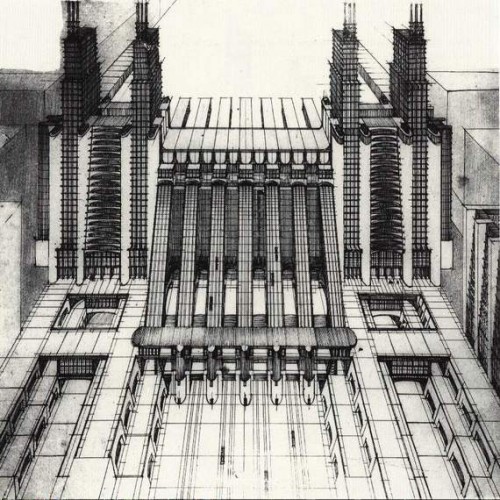

Cette perspective de Lyotard, qui enferme dans le concept “moderne” le cartésianisme, le newtonisme, les mécanicismes des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, les Lumières, l'hégélianisme et le marxisme, a été fructueuse ; on lui a donné des ancêtres, notamment l'augustinisme politique, cherchant à “construire” une Cité parfaite et attribué un dénominateur commun : le projet d'élaborer une mathesis universalis, de disséquer la nature (Bacon) et d'épouser le “pathos du renouveau radical”. Chez Descartes, la métaphore de la ville illustre parfaitement l'enjeu du projet de mathesis universalis et du pathos du renouveau ; les villes anciennes, dit Descartes, sont des enchevêtrements non coordonnés ; l'architecte moderne doit tout détruire, même les éléments qui, isolés, sont beaux, pour reconstruire tout selon un plan rationnel, afin de créer une cohérence rationnelle parfaite et à biffer les imperfections organiques. Résultat : l'uniformité atone des villes de béton contemporaines. La modernité à évacuer, dans les perspectives de Lyotard, de Welsch et des architectes postmodernes, c'est celle qui a prétendu, jadis, gommer toutes les particularités au bénéfice d'une méthode, d'un projet, d'une histoire (récapitulative de touteS les histoireS locales et particulières).

Une opposition deux fois centenaire au projet de “mathesis universalis”

Le cartésianisme universaliste a eu ses adversaires dès le XVIIIe siècle. Vico rejette l'image mobilisatrice du progrès au profit d'une conception cyclique de l'histoire ; vers 1750, année-clef, Rousseau, dans son Discours sur les Sciences et les Arts, critique le programme scientifique du cartésianisme et Baumgarten, dans son Aesthetica, réclame une « compensation esthétique » à la sécheresse rationaliste. Depuis, les critiques se sont succédé : Schlegel en appelle à une révolution esthétique ; Baudelaire, Nietzsche et Gottfried Benn, chacun à leur manière, célèbrent l'art comme « espace de survie dans des conditions invivables », comme réponse à l'aridité cartésienne/rationaliste/technocratique. Mais, les réponses de la Gegen-Neuzeit, de la contre-modernité qui se déploie de 1750 à nos jours, se veulent également exclusives, radicales et universelles. Le schéma unitaire et monolithique, sous-jacent à la modernité cartésienne n'est pas éliminé. Au contraire, les courants de la Gegen-Neuzeit ne font qu'ajouter un zeste d'esthétique à un monde qui ne cesse d'amplifier, d'accroître et de dynamiser les forces relevant de la Neuzeit cartésienne. Chez Vico et Rousseau, le salut ne peut provenir que d'un et un seul renversement radical de perspective ; ils ne comprennent pas que leur solution de rechange n'est qu'une possibilité parmi plusieurs possibilités et ils affirment détenir la clef de la seule voie de salut.

Le “saut qualitatif” de la physique du XXe siècle

La nécessité qui s'impose est donc de procéder à un “saut qualitatif”, de ne pas répondre au programme de la modernité par un programme aussi global et aussi fermé sur lui-même. Vico, Rousseau, les Romantiques, ont certes deviné intuitivement les pistes qu'il s'agissait d'emprunter pour échapper à l'enfermement de la modernité/Neuzeit, mais ils n'ont pas su exprimer leur volonté par un programme aussi radical et complet, aussi scientifique et concret, aussi clair et pragmatique, que celui de la dite modernité.

Leurs revendications apparaissaient trop littéraires, pas assez scientifiques (malgré l'impact des médecines romantiques, des recherches sur les maladies psychosomatiques, etc.). La réaction contre la Neuzeit semblait n'être qu'une réaction passionnelle et émotive contre les sciences pratiques et physiques, déterminées par les méthodes mécanicistes de Newton et de Descartes. Cela changera dès le début du XXe siècle. Grâce aux travaux des plus éminents phycisiens, les concepts de pluralité et de particularité ne sont plus catalogués comme des manies littéraires mais deviennent, dans le champ scientifique luimême, des valeurs dominantes et incontournables. Partant des domaines des sciences physiques et biologiques, ces concepts glisseront petit à petit dans les domaines des sciences humaines, de la sociologie et de la philosophie.

La Neuzeit s'était prétendue scientifique : or voilà que le domaine scientifique, impulsé au départ par la modernité cartésienne, révise radicalement les a priori de la Neuzeit et adopte d'autres assises épistémologiques. Plus question de raisonner à partir de totalités fermées sur elle-mêmes, homogènes et universelles. Ouvertures, hétérogénéités et particularités expliquent désormais la trame complexe et multiple de l'univers. La théorie restreinte de la relativité chez Einstein induit les philosophes à admettre qu'il n'y a plus aucun concept de totalité qui soit acceptable ; il ne reste plus que des relations entre des systèmes indépendants les uns des autres dans la simultanéité ; l'action du temps, de surcroît, rend ces simultanéités caduques et éphémères. Heisenberg démontre, par sa théorie de la Unschärferelation (relation d'incertitude), que les grandeurs définies dans un même système de relations ne peuvent jamais être déterminées de façon figée et simultanée. Finalement, Gödel, par son axiome d'incomplétude, ruine définitivement le rêve de la modernité et des universalismes, celui de construire une mathesis universalis, puisque toute connaissance est limitée, par définition.

Une pluralité de modèles et de paradigmes

Cette révolution dans les sciences physiques se poursuit toujours actuellement : la théorie des fractales de Mandelbrot (fonctions discontinues en tous points), la théorie des catastrophes chez Thom, la théorie des structures dissipatives chez Prigogine, la théorie du chaos synergétique de Haken, etc., confirment que déterminisme et continuité n'ont de validité que dans des domaines limités, lesquels n'ont entre eux que des rapports de discontinuité et d'antagonisme. D'où le réel n'est pas agencé selon un modèle unique mais selon des modèles différents ; il est structuré de manière conflictuelle et dramatique ; nous dirions “tragique”, parce qu'il ne laisse plus de place désormais aux visions iréniques, bonheurisantes et paradisiaques que nous avaient proposées les sotériologies religieuses et laïques.

Il n'est plus possible de proposer sérieusement un programme valable pour tous les hommes en tous les lieux de la planète, puisque nous nous acheminons, sous l'impulsion de l'épistémologie physique en marche depuis le début du siècle, vers l'acception d'une pluralité de modèles et de paradigmes, en concurrence les uns avec les autres : les solutions simples, univoques, monopolistiques, universalistes, figées et exclusives relèvent dorénavant du rêve, non plus du possible. La philosophie postmoderne prend donc le relais des sciences physiques contemporaines et tente de transposer dans les consciences et dans le quotidien ce pluralisme méthodologique.

Postmodernité anonyme et postmodernité diffuse

Comme les “méta-récits”, critiqués par Lyotard, étaient monopolistiques et universalistes dans leur essence et dans leur projet, la physique du XXe siècle leur ôte le socle sur lequel ils reposaient. Mais, tout comme les réactions du XVIIIe et du XIXe, les réactions contemporaines à l'encontre des reliquats des méta-récits sont diverses et souvent imprécises. Pour Welsch, la stratégie postmoderne qui prend le relais de l'épistémologie scientifique est précise et solide. Face à cette précision et cette solidité, se positionnent d'autres stratégies postmodernes, nous explique Welsch, qui n'en ont ni la rigueur ni la force ; celle de la postmodernité anonyme qui englobe les théories et travaux qui ne se définissent pas proprement comme postmodernes mais se moulent, consciemment ou inconsciemment, sur l'épistémologie pluraliste induite par les sciences physiques ; la palette est large : on peut y inclure Wittgenstein, Kuhn (9), Feyerabend (10), l'herméneutique de Gadamer, le “post-structuralisme” de Derrida et de Deleuze, etc. Ensuite, il y a la postmodernité diffuse ; c'est celle que vulgarisent la grande presse et les “feuilletonistes”, qui profitent de l'effondrement de la modernité rigide pour parler de postmodernité sans avoir trop conscience de ses enjeux épistémologiques réels. C'est la postmodernité du pot-pourri, d'un Disneyland intellectuel ; c'est un irrationalisme contemporain qui ne va pas à l'essentiel comme n'allait pas à l'essentiel une quantité de romantiques réagissant contre le cartésianisme.

Pour Welsch, la postmodernité précise, scientifique, consciente de la rupture signalée par les sciences physiques, s'avérera efficiente, tandis que la PM anonyme demeurera imprécise et la PM diffuse, contre-productive. Seule la PM précise emporte son adhésion, car elle est systématique, cohérente, porteuse d'avenir. Pour Welsch, la “modernité du XXe siècle”, c'est la scientificité qui annonce la postmodernité, qui consomme la rupture avec la rigidité monopolistique et universaliste de la modernité/Neuzeit. La postmodernité qui prend le relais de la “modernité du XXe siècle” est ouverte à l'innovation, n'est pas strictement réactive à la mode rousseauiste ou romantique.

Or, on pourrait formuler une objection : les technologies modernes, phénomènes du XXe siècle, contribuent à uniformiser la planète , restant du coup dans la même logique que celle de la Neuzeit. Face à cet état de choses, il convient d'adopter le langage suivant, dit Welsch : quand les technologies s'avèrent uniformisantes, elles sont au service d'une logique politique issue de la Neuzeit et sont ipso facto contestées par les postmodernes conséquents ; quand, en revanche, elles fonctionnent dans le sens d'une pluralité, elles participent à la dissolution des pesanteurs modernes et sont dès lors acceptées par les postmodernes. Ce n'est pas une technologie en soi qui est bonne ou mauvaise, c'est la logique au service de laquelle elle fonctionne qui est soit obsolète soit grosse d'avenir. Welsch expose cette problématique de sang froid, sans dire — même si c'est implicite — qu'il est grand temps de se débarrasser des logiques politiques issues de la Neuzeit... La logique de la discontinuité, du tragique et de la dissipativité prigoginienne, etc., est passée de la science à la philosophie ; il faut maintenant qu'elle passe de la philosophie à la politique et au quotidien. Pour cela, il y aura bien des résistances à briser.

Un parallèle évident avec la “Nouvelle Droite”

Ce que propose Welsch dans son livre (UPM), et qui enchante Armin Mohler, c'est une chronologie de l'histoire intellectuelle occidentale et européenne, dans laquelle notre mouvement de pensée peut tout entier s'imbriquer. Dans divers articles de Nouvelle École, Giorgio Locchi a suggéré, lui aussi, une chronologie, marquée de « périodes axiales » (Jaspers, Mohler, etc.) (11), où les grandes idées motrices, dont le christianisme, passent par le stade initial du mythe, pour aboutir, via un stade idéologique, à un stade scientifique. L'incapacité du christianisme à accéder à un stade scientifique cohérent annonce l'avènement d'un autre mythe, incarné par de multiples linéaments diffusés et véhiculés par la musique européenne, par le romantisme et par Wagner, mythe qui devra se muer en idéologie et en science.

L'effondrement des fascismes quiritaires, au cœur aventureux, a provoqué, explique Locchi (12), la disparition du stade “idéologique”, tandis que la percée de nature scientifique poursuivait son chemin de Heisenberg à Prigogine, Haken, etc. Le surhumanisme — Locchi utilise ce vocable pour désigner les réactions idéologiques et littéraires contre la modernité — a donc son mythe, wagnérien et nietzschéen, et sa science, la physique contemporaine, mais pas son articulation politique. Si l'on procède à la fusion des chronologies suggérées par Locchi et par Welsch, on obtient un instrument critique d'orientation, qui est de grande valeur pour comprendre la dynamique de notre siècle, sans devoir retomber dans une paraphrase stérile des fascismes.

Or, pour les derniers défenseurs de la modernité, dont Habermas (chez qui Welsch perçoit tout de même d'importantes concessions à la postmodernité, parce que Habermas ne peut renoncer aux acquis de la science physique moderne, née pendant la Neuzeit, et parce que sa théorie de “l'agir communicationnel” implique tout de même un relâchement des rigidités monopolistiques), est “fascisme” ou “fascistoïde” tout ce qui critique la modernité et ses avatars ou s'en distancie. Georg Lukacs, dans Die Zerstörung der Vernunft, stigmatise comme “irrationalismes” toutes les philosophies, sociologies et nouveautés littéraires qui s'opposent au déterminisme rationaliste et matérialiste du grand récit marxiste (né des grands récits hégélien et anglo-libéral).

Notre vision du monde doit s'asseoir dans l'avenir sur 2 chronologies : celle de Locchi et celle de Welsch, tout en maîtrisant correctement celles, adverses, de l'École de Francfort et d'Habermas (cf. Horkheimer et Adorno, La dialectique de la Raison), ainsi que celle du marxisme particulier de Lukacs. Une attention spéciale doit également être réservée aux chronologies néolibérales (cf. Alain Laurent, L'individu et ses ennemis, LP/Pluriel, 1987), hostiles aux dimensions holistes de tous ordres. Le débat idéologique est certes la confrontation d'idées et de thématiques idéologiques différentes ; il est aussi et surtout confrontation entre des chronologies différentes, des visions de l'histoire où sont mises en exergue des valeurs précises, au moment où elles font irruption dans l'histoire : dans le cas de l'historiographie libérale/néo-marxiste, c'est le triomphe des stratégies de mathesis universalis, assorties d'un déterminisme physicaliste ; pour les néo-libéraux, c'est l'avènement de l'individu et des méthodologies individualistes en sociologie et en économie. Pour nous, ce sont les étapes d'une pensée plurielle, où l'ouverture d'esprit est due à la reconnaissance des innombrables possibilités en jachère dans la nature et dans l'histoire ; autant de différences, d'ordre somatique ou d'ordre culturel, autant de virtualités.

De l'épistémologie mécaniciste à l'épistémologie botaniciste

Si nous récapitulons l'histoire intellectuelle de l'Europe occidentale et germanique, nous constatons, entre 1750 et le milieu du XIXe siècle, l'émergence d'une quantité de réactions dans le désordre, contre les projets de mathesis universalis, contre la “volonté géométrique” de la modernité. À la logique mécanique et géométrique, le Sturm und Drang allemand, le romantisme, le Kant de la Critique de la faculté de juger, Schiller, Burke, les doctrinaires allemands de la vision organique de la politique et de l'histoire opposent une autre logique, une logique botaniciste, qui pose une analogie entre l'arbre (ou la plante vivante) et l'État (ou la Nation) au lieu de poser l'analogie cartésienne/newtonienne entre l'État et un système d'horlogerie, entre les lois du politique et les lois régissant les mouvements de la matière morte (13). La rupture épistémologique de la fin du XVIIIe, qui enclenche l'émergence de la pensée organiciste et vitaliste, amorce une pluralité, dans le sens où, désormais, 2 logiques, l'une organiciste/vitaliste, l'autre rationaliste/ mécaniciste, vont se juxtaposer. Mais la physique, perçue comme socle ultime du réel, demeure ancrée dans ses présupposés newtoniens ; aucune alternative sérieuse ne peut encore remplacer, sur le plan scientifique, les assises newtoniennes et cartésiennes de la physique. Georges Gusdorf, dans ses études sur le “savoir romantique”, montre comment le passage à une pensée “glandulaire” après l'impasse d'une pensée “cérébro-spinale”, a suscité un intérêt pour la biologie, la cénesthésie (14), la psychologie et les maladies psycho-somatiques, l'anthropocosmomorphisme de Carus et Oken (15), etc. Dénominateur commun de cette démarche : tout être vivant, homme, animal ou plante, possède un noyau identitaire propre, non interchangeable, unique ; au départ des noyaux identitaires, lieux d'irradiation du monde, un pluriversum, un monde pluriel, surgit, qui ne se laisse plus violenter par des schémas géométriques.

L'irruption de Nietzsche

À la fin du XIXe siècle, la scène philosophique européenne connaît l'irruption de Nietzsche. Celui-ci, se situant à la charnière entre la rupture épistémologique romantique/organiciste/vitaliste, magistralement étudiée par Gusdorf, et la rupture épistémologique provoquée par les découvertes de la physique au début du XXe, rejette les grands récits de l'Aufklärung et se moque, en stigmatisant le wagnérisme, des insuffisances des réponses romantiques. Mais son œuvre ne brise pas encore totalement le semblant d'évidence que revêtent les positivismes/rationalismes, détenteurs de la seule théorie physique qui tienne à l'époque. D'où, de la part des chrétiens et des positivistes, le reproche d'incohérence et de contradiction adressé à l'œuvre de Nietzsche ; pour ces perspectives, Nietzsche est fou ou Nietzsche est un philosophe incomplet ; il nous lègue une logique anarchique qui permet de tout casser (au marteau, pour reprendre son expression). Ce sont notamment les interprétations de Deleuze et de Kaulbach (16). Pour Reinhard Löw, cette interprétation du message nietzschéen est insuffisante, car s'il est vrai que Nietzsche souhaite “casser” au marteau certaines idoles philosophiques, son entreprise de démolition vise essentiellement les «psittacismes», c'est-à-dire les discours qui répètent le schéma eschatologique et providentialiste chrétien, en lui conférant des oripeaux idéalistes (chez Hegel) ou matérialistes (chez les marxistes et quelques darwiniens). L'avènement de l'esprit, du prolétariat, d'un homme moins “singe”, ne sont que des novismes calqués sur un même schéma. Schéma qu'il s'agit de dissoudre, afin qu'il ne puisse plus produire de “récits” aliénants parce que répétitifs et non innovateurs. La positivité de Nietzsche, différente de sa négativité de philosophe au marteau, consiste, écrit Löw (17), à nous éduquer, afin que nous ne continuions pas, à l'infini, à ajouter des psittacismes aux psittacismes qui nous ont précédés.

La logique du XIXe a donc été, dans une première phase, de rompre le psittacisme more geometrico du projet cartésien de mathesis universalis, puis, avec Nietzsche, de signaler le danger permanent du psittacisme pour, enfin, découvrir, avec les physiciens du début du XXe, que la trame la plus profonde du réel n'autorise, en fin de compte, aucune forme de psittacisme et que le mythe de la continuité linéaire est une illusion humaine. La post-modernité (la “précise” selon la classification de Welsch) prend acte de cette évolution et veut en être l'héritière. Mais franchir le cap d'une telle prise de conscience est dur : entre les fulgurances aphoristiques de Nietzsche et la révolution intellectuelle impulsée par la physique du XXe siècle, la littérature et la poésie de la fin du XIXe siècle a effectué un travail de deuil, le deuil des “totalités perdues”, des référentiels évanouis, sur fond d'angoisse et de nostalgie. Chez Musil, représentant emblématique de cette angoisse, on découvre le constat que la modernité, arrivée à terme au moment de la “Belle époque”, n'est pas le paradis escompté ; c'est, au contraire, le règne de la mort froide, de la rigidité cadavérique, laquelle s'abat sur une humanité victime d'une “épidémie géométrique”.

L'apport de Lyotard

Revenons à Welsch, disciple de Lyotard, philosophe français contemporain qui, en 1979, publie aux éditions de Minuit La condition postmoderne. Que pense Welsch de cet ouvrage qui indique clairement la thématique philosophique qu'il entend cerner ? Il en pense du bien, mais non exagérément. Le livre pose les bonnes questions, dit-il, mais ne les explicite guère. Pour Welsch, il faut “savoir faire quelque chose du livre”, en tirer l'essentiel, profiter de la perspective qu'il nous ouvre. Quant au reste de l'œuvre de Lyotard, il abonde dans le sens d'une postmodernité précise, héritière de la physique du XXe siècle. Chez Lyotard, la postmodernité n'apparaît pas comme un irrationalisme mais comme une rupture par rapport à la modernité qui critique la raison de la modernité avec les armes de la raison ; comme une rupture qui ne rejette pas la raison pour la remplacer par des instances diverses, posées arbitrairement comme moteur du monde et des choses. C'est ici que les démarches de Lyotard et de Welsch se distinguent de celle d'un Bergfleth, qui remplace la raison et la rationalité moderne/francfortiste par l'éros, la cruauté, la passion, l'amour, etc. tels que les envisagent Artaud, Bataille, Klages, etc.

Du point de vue plus directement (méta)politique, Lyotard nous enseigne que les totalités, et, partant, les universalismes, sont toujours les produits absoluisés de sentiments ou d'intérêts particuliers ; que ce que le groupe ou l'individu x proclame comme universel est l'absoluisation de ses intérêts particuliers. D'où être démocrate et tolérant, c'est refuser cette logique d'absoluisation, porté par un prosélytisme sourd aux particularités des autres. Refuser les totalités et les universalismes, c'est aller davantage au fond des choses, c'est respecter les particularités des peuples, des classes, des individus. Penser le pluriel, c'est être davantage “démocrate” que ceux qui uniformisent à outrance. Le monde est plurivers ; il est un pluriversum et ne saurait être saisi dans toute son amplitude par une et une seule logique.

L'apport de Gianni Vattimo

Gianni Vattimo, dans La fin de la modernité (Seuil, 1987), nous explique que la modernité, c'est le “novisme”, démarche dont s'était moqué Nietzsche, père de l'ère postmoderne. Le “novisme” est produit de l'historicisme ; il est répétition du même vieux schéma linéaire métaphysique et chrétien sous un travestissement tantôt idéaliste, tantôt matérialiste. À ces novismes d'essence providentialiste. Nietzsche a successivement répondu par 2 stratégies ; d'abord, celle qui consistait à affirmer des valeurs éternelles transcendant l'histoire, transcendant les prétentions des historicismes qui croyaient pouvoir les dépasser ou les contourner ; ensuite, en affirmant l'éternel retour, démenti définitif aux providentialismes. La postmodernité est donc l'absence de providentialisme, la disparition des réflexes mentaux et idéologiques dérivés des providentialismes métaphysiques et chrétiens. Après Nietzsche, Heidegger prend le relais, explique Vattimo, et nous enseigne de ne pas dépasser (überwinden) la modernité laïque/ métaphysique/providentialiste, mais de la contourner (verwinden) ; en effet, l'idée d'un dépassement garde quelque chose d'eschatologique, donc de métaphysique/chrétien/moderne. L'idée d'un contournement suggère au contraire le passage tranquille à une autre perspective, qui est plurielle et non plus monolithique, herméneutique (dans le sens où elle “interprète” le réel au départ de données diverses, dont les logiques intrinsèques sont hétérogènes sinon contradictoires) et non plus dogmatique. Le futurisme, en dépit de ses apparences “novistes”, est un phénomène postmoderne, affirme Vattimo, parce qu'il entremêle différents langages et codes, permettant ainsi une ouverture sur plusieurs univers culturels, développe une multiplicité de perspectives sans chercher à les synthétiser, à les soumettre à un idéal (violent ?) de conciliation. La modernité, chez Vattimo, n'est pas rejetée, elle est absorbée comme composante d'une postmodemité marquée du signe du pluriel.

L'apport de Michel Foucault

L'apport de Foucault à la pensée contemporaine, c'est surtout la suggestion d'une histoire intellectuelle nouvelle, d'une chronologie de la pensée qui bouleverse les conformismes. Foucault voit la succession de diverses ruptures dans l'histoire intellectuelle européenne depuis la Renaissance ; au XVIIe, l'Europe passe de la tradition au classicisme ; au XIXe, du classicisme au modernisme (et ici le terme “moderne” prend une autre acception que chez Welsch et Lyotard, où la notion de “modernité” recouvre plus ou moins la notion foucaldienne de “classicisme”). Il est très intéressant de noter, dit Welsch, que Foucault oppose la “doctrine des ordres” de Pascal au projet de mathesis universalis de Descartes. Chez Pascal, en effet, l'ordre de l'Amour, l'ordre de l'Esprit et l'ordre de la Chair ont chacun leur propre “rationalité” ; la logique de la foi n'est pas la logique de la raison ni la logique de l'action. D'où la pensée de Pascal postule des “différences” et non une unique mathesis universalis ; elle est donc foncièrement différente de la tradition monolithique de Descartes qui a eu le dessus en France. Foucault nous indique que Pascal représente une potentialité de la pensée française qui est demeurée inexploitée.

L'apport de Foucault à la pensée contemporaine, c'est surtout la suggestion d'une histoire intellectuelle nouvelle, d'une chronologie de la pensée qui bouleverse les conformismes. Foucault voit la succession de diverses ruptures dans l'histoire intellectuelle européenne depuis la Renaissance ; au XVIIe, l'Europe passe de la tradition au classicisme ; au XIXe, du classicisme au modernisme (et ici le terme “moderne” prend une autre acception que chez Welsch et Lyotard, où la notion de “modernité” recouvre plus ou moins la notion foucaldienne de “classicisme”). Il est très intéressant de noter, dit Welsch, que Foucault oppose la “doctrine des ordres” de Pascal au projet de mathesis universalis de Descartes. Chez Pascal, en effet, l'ordre de l'Amour, l'ordre de l'Esprit et l'ordre de la Chair ont chacun leur propre “rationalité” ; la logique de la foi n'est pas la logique de la raison ni la logique de l'action. D'où la pensée de Pascal postule des “différences” et non une unique mathesis universalis ; elle est donc foncièrement différente de la tradition monolithique de Descartes qui a eu le dessus en France. Foucault nous indique que Pascal représente une potentialité de la pensée française qui est demeurée inexploitée.

Outre Pascal, Gaston Bachelard influence Foucault dans son élaboration d'une histoire intellectuelle de l'Occident. Pour Bachelard, l'évolution des sciences et du savoir ne procède pas de façon continue (linéaire), mais plutôt par crises et par “coupures épistémologiques”, par fulgurances. Chacune de ces coupures ou fulgurances provoque un renversement du système du savoir ; elles induisent de brèves “périodes axiales”, où les institutions, les coutumes, les pratiques politiques doivent (ou devraient) s'adapter aux innovations scientifiques. Foucault a retenu cette vision rupturaliste de Bachelard, où des “différences” fulgurent dans l'histoire, et sa pensée est ainsi passée d'une phase structuraliste à une phase potentialiste (18). Le structural structuralisme, avec Lévy-Strauss, avait tenté de trouver Le Code universel, l'invariant immuable (lui se cachait quelque part derrière la prolixité des faits et des phénomènes. En cela, le structuralisme était en quelque sorte le couronnement de la modernité. Foucault, dans la première partie de son œuvre, a souscrit à ce projet structuraliste, pour découvrir, finalement, que rien ne peut biffer, supplanter, régir ou surplomber l'hétérogénéité fondamentale des choses. Aucune “différence” ne se laisse reconduire à une unité quelconque qui serait LA dernière instance. Une telle unité, hypothétique, baptisée tantôt mathesis universalis, tantôt “Code”, participe d'une logique de l'en l'enfermement, refus têtu et obstiné du divers et du pluriel.

L'apport de Gilles Deleuze

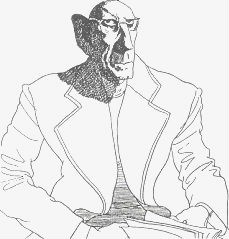

[Ci-contre : dessin de Béatrice Cleeve, montrant bien la complicité qui unit les co-auteurs de L'Anti-Œdipe et de Mille plateaux]

Gilles Deleuze entend affirmer une philosophie de la “libre différence”. Son interprétation de Nietzsche (19) révèle clairement cette intention : « ... car il appartient essentiellement à l'affirmation d'être elle-même multiple, pluraliste, et à la négation d'être une, ou lourdement moniste » (p. 21). « Et dans l'affirmation du multiple, il y a la joie pratique du divers. La joie surgit, comme le seul mobile à philosopher. La valorisation des sentiments négatifs ou des passions tristes, voilà la mystification sur laquelle le nihilisme fonde son pouvoir » (p. 30). Affirmer, c'est donc démolir gaillardement les rigidités lourdement monistes au marteau, c'est briser à jamais la prétention des unités, des totalités, des instances décrétées immuables par les “faibles”. Une “différence” n'indique pas une unité sous-jacente mais au contraire des autres différences. D'où, pour Deleuze comme pour Foucault, il n'y a pas de Code mais bien un chaos informel, qu'il s'agit d'accepter joyeusement. Ce chaos prend, chez Deleuze, le visage du rhizome. Métaphore organiciste, le rhizome [filament racinaire en réseau] se distingue de l'arbre des traditions romantiques, dans le sens où il ne constitue pas une sorte d'unité séparée d'autres unités semblables ; le rhizome est un grouillement en croissance ou en décroissance perpétuelle, qui s'empare des chaînes évolutives étrangères et suscite des liaisons transversales entre des lignes de développement divergentes ; c'est un fondu enchaîné, un dégradé de couleur qui se mixe à un autre dégradé. Deleuze, bon connaisseur de Leibniz, prend congé ici de la philosophie des monades pour affirmer une philosophie nomade ; une philosophie des rhizomes nomades qui produisent des différences non systématiques et inattendues, qui fragmentent et ouvrent, abandonnent et relient, différencient et synthétisent simultanément (UPM, p. 142).

Gilles Deleuze entend affirmer une philosophie de la “libre différence”. Son interprétation de Nietzsche (19) révèle clairement cette intention : « ... car il appartient essentiellement à l'affirmation d'être elle-même multiple, pluraliste, et à la négation d'être une, ou lourdement moniste » (p. 21). « Et dans l'affirmation du multiple, il y a la joie pratique du divers. La joie surgit, comme le seul mobile à philosopher. La valorisation des sentiments négatifs ou des passions tristes, voilà la mystification sur laquelle le nihilisme fonde son pouvoir » (p. 30). Affirmer, c'est donc démolir gaillardement les rigidités lourdement monistes au marteau, c'est briser à jamais la prétention des unités, des totalités, des instances décrétées immuables par les “faibles”. Une “différence” n'indique pas une unité sous-jacente mais au contraire des autres différences. D'où, pour Deleuze comme pour Foucault, il n'y a pas de Code mais bien un chaos informel, qu'il s'agit d'accepter joyeusement. Ce chaos prend, chez Deleuze, le visage du rhizome. Métaphore organiciste, le rhizome [filament racinaire en réseau] se distingue de l'arbre des traditions romantiques, dans le sens où il ne constitue pas une sorte d'unité séparée d'autres unités semblables ; le rhizome est un grouillement en croissance ou en décroissance perpétuelle, qui s'empare des chaînes évolutives étrangères et suscite des liaisons transversales entre des lignes de développement divergentes ; c'est un fondu enchaîné, un dégradé de couleur qui se mixe à un autre dégradé. Deleuze, bon connaisseur de Leibniz, prend congé ici de la philosophie des monades pour affirmer une philosophie nomade ; une philosophie des rhizomes nomades qui produisent des différences non systématiques et inattendues, qui fragmentent et ouvrent, abandonnent et relient, différencient et synthétisent simultanément (UPM, p. 142).

L'apport de Jacques Derrida

L'apport de Derrida démarre avec un texte de 1968, « La fin de l'Homme », repris dans une anthologie intitulée Marges de la philosophie. Derrida y explique que la pluralité est la clef de l'au-delà de la métaphysique. La pluralité, c'est savoir parler plusieurs langages à la fois, solliciter conjointement plusieurs textes. Le parallèle est aisé à tracer avec la “physiologie” de Nietzsche, qui prend acte des multiplicités du monde sans vouloir les réduire à un dénominateur commun mutilant (20). Le réel, ce sont des pistes qui traversent des champs différents, ce sont des enchevêtrements. Différentiste et non rupturaliste, Derrida voit la trame du monde comme un processus de différAnce, de dissémination, producteur de différEnces. Derrida nous impose cette subtilité lexicographique (le A et le E) non sans raison. La différAnce implique un principe actif de différentiation par dissémination, tandis que parler de différEnce(s) peut laisser suggérer que le monde, le réel, soit une juxtaposition sans dynamisme et sans interaction de différEnces non enchevêtrées. Derrida veut ainsi échapper à une pensée musa musaïque où les différEnces seraient exposées les unes à côté des autres comme des pièces dans une vitrine de musée. Mais le souci de montrer l'enchevêtrement de toutes choses — avec, pour corollaire leur non-réductibilité à quelqu'unum que ce soit — conduit Derrida à affirmer que la différAnce productrice de différEnces finit par produire une panade d'indifférEnce, comparable à l'hypertélie obèse de Baudrillard. Dans cette panade peuvent s'engouffrer les vulgarisateurs de la “PM diffuse”, critiquée par Welsch (cf. supra).

Mais même si Derrida se rétracte quelque peu avec sa théorie de la « panade d'indifférEnce » (qui a forcément des relents d'universalisme, puisque les différEnces y sont malaxées), même si, par ailleurs, il évoque la “mystique juive” pour se mettre au diapason de la farce qu'est le “réarmement théologique” du “nouveau philosophe” BHL, nous n'oublions pas qu'il a dit un jour qu'« est chimère tout projet de langage universel ». Mieux : il a posé l'équation Apocalypse = mort = vérité. L'Apocalypse, prélude à un monde meilleur, est la mort parce qu'elle prétend être la vérité et que la vérité n'est qu'un euphémisme pour désigner la mort. La vérité, c'est le vœu, l'utopie, de la présence accomplie, du présentisme où tout devenir est enrayé, stoppé, où la différAnce cesse d'être productrice de différEnces. Pour Derrida, comme pour Pierre Chassard, analyste néo-droitiste de la pensée nietzschéenne (21), il faut déconstruire le complexe “apocalypse”, le providentialisme producteur de psittacismes, dérivé des vulgates platonicienne et chrétienne.

Postmodernité “soft” et postmodernité “hard”

On peut dire que Lyotard et Derrida partagent une conception commune : pour l'un comme pour l'autre, la postmodernité n'est pas une époque nouvelle, ce n'est pas l'avènement d'une espèce de parousie de nouvelle mouture, survenue après une rupture/catastrophe, mais le passage, le contournement (Heidegger/Vattimo) inéluctable qui nous mène vers une attitude de l'esprit et des sentiments, qui a toujours déjà été là, qui a toujours été virtualité, mais qui, aujourd'hui, se généralise, malgré les tentatives “réactionnaires” que sont le “réarmement théologique”, assorti de son culte de la “Loi” et corroboré par les démarches anti-68 de Ferry et Renaut. La postmodernité, ce sont des ouvertures aux pluralités, aux diversifications.

Peut-on parler de postmodernité soft et de postmodernité hard ? La distinction peut paraître oiseuse voire mutilante mais, par commodité, on pourrait qualifier de soft la PM différentiste de Deleuze et de Derrida, avec sa pensée nomade et son indifférence finale, et de hard la PM rupturiste de Lyotard. Dans ce cas, cette double qualification désignerait, d'une part, un différentialisme qui s'enliserait dans l'indifférence, dans la purée, la panade du “tout vaut tout” et retournerait subrepticement au Code, un Code non plus intégrateur, rassembleur et totalisant, mais un Code négatif, discret, non intégrant et non agonal. Pour un Lyotard, une rupture signale toujours l'incommensurabilité d'une différEnce, même si cette différEnce n'est pas éternelle, immuable. Les ruptures signalent toujours une densité particulière, laquelle se recompose sans cesse par télescopage avec des faits nouveaux. L'hypertélie de Baudrillard n'estelle pas analogue, sur certains points, avec la chute dans l'indifférence (Derrida) et la nomadisation deleuzienne ? La fin est là, nous explique Baudrillard dans Amérique (Grasset, 1986), comme quand la différAnce, à être trop féconde, ne produit plus que de l'indifférEnce, de la métastabilité.

Une dynamique de la transgression

[Leibniz, philosophe des monades, a été réinterprété récemment par G. Deleuze. Celui-ci voit en lui le philosophe des “plis” et des “replis”, lesquels recèleraient des potentialités en jachère, prêtes à intervenir sur la trame du réel puis à se retirer ou se disperser]

Contre l'ennui sécrété par la juxtaposition de métastabilités ou par le règne d'une grande et unique métastabilité, il faut instrumentaliser une logique transversale, qui brise les homogénéités fermées et force leurs séquelles à se recomposer de manières diverses et infinies. Sur le plan idéologique et politique, c'est pour une logique de la transgression qu'il faut opter, une logique qui refuse de tenir compte des enfermements imposés par les idéologies dominantes et par les pratiques politiciennes ; Marco Tarchi, leader de la ND italienne, a théorisé la « dynamique de la transgression » (22), laquelle part du constat de l'hétérogénéité fondamentale des discours politiques ; en effet, existe-t-il une gauche et une droite ou des gauches et des droites ? Toutes ces strates ne se combinent-elles pas à l'infini et n'est-on pas alors en droit de constater que la seule réalité qui soit en dernière instance, c'est un magma de desiderata complexes. La logique de la transgression va droit à ce magma et contourne les facilités dogmatiques, les totems idéologiques et partisans qui résument quelques bribes de ce magma et érigent leurs résumés en vérités intangibles et pérennes. La logique et la dynamique de la transgression postulent de ne rejeter aucun fait de monde, de combiner sans cesse des logiques décrétées antagonistes, d'agir en conciliant des desiderata divergents, sans pour autant mutiler et déforcer ces desiderata. La dynamique de la transgression prend le relais de la vision de la coincidentia oppositorum de Maître Eckhardt et de Nicolas de Cues.

Contre l'ennui sécrété par la juxtaposition de métastabilités ou par le règne d'une grande et unique métastabilité, il faut instrumentaliser une logique transversale, qui brise les homogénéités fermées et force leurs séquelles à se recomposer de manières diverses et infinies. Sur le plan idéologique et politique, c'est pour une logique de la transgression qu'il faut opter, une logique qui refuse de tenir compte des enfermements imposés par les idéologies dominantes et par les pratiques politiciennes ; Marco Tarchi, leader de la ND italienne, a théorisé la « dynamique de la transgression » (22), laquelle part du constat de l'hétérogénéité fondamentale des discours politiques ; en effet, existe-t-il une gauche et une droite ou des gauches et des droites ? Toutes ces strates ne se combinent-elles pas à l'infini et n'est-on pas alors en droit de constater que la seule réalité qui soit en dernière instance, c'est un magma de desiderata complexes. La logique de la transgression va droit à ce magma et contourne les facilités dogmatiques, les totems idéologiques et partisans qui résument quelques bribes de ce magma et érigent leurs résumés en vérités intangibles et pérennes. La logique et la dynamique de la transgression postulent de ne rejeter aucun fait de monde, de combiner sans cesse des logiques décrétées antagonistes, d'agir en conciliant des desiderata divergents, sans pour autant mutiler et déforcer ces desiderata. La dynamique de la transgression prend le relais de la vision de la coincidentia oppositorum de Maître Eckhardt et de Nicolas de Cues.

Des traductions politiques du défi postmodeme sont-elles possibles ?

Notre mouvement de pensée, en constatant que le chaos synergétique des physiciens modernes s'est transposé du domaine des sciences naturelles au domaine de la philosophie, doit se donner pour tâche de faire passer le message de la physique moderne dans l'opinion puis dans la sphère du politique. Ce serait répondre à sa vocation métapolitique. Passer dans le domaine du politique et de la politique, c'est travailler à substituer au droit individualiste moderne un droit adapté aux différences humaines, que celles-ci soient d'ordre social, ethnique, régional, etc. ; c'est travailler à ruiner les idéologies économiques modernes et à leur substituer une économie basée sur la « dynamique des structures » (François Perroux) ; c'est travailler à l'avènement de nouvelles formes de représentation politique, où les multiples facettes de l'agir humain seront mieux représentées (modèles : le Sénat des régions et des professions de De Gaulle ; les projets analogues du Professeur Willms, etc.).

Le travail à accomplir est énorme, mais lorsque l'on constate que les linéaments de notre vision tragique du monde et de l'univers sont présents partout, il n'y a nulle raison de désespérer...

♦ Wolfgang Welsch, Unsere postmoderne Moderne, VCH – Acta Humantora, Weinheim, 1987, 344 p.

► Robert Steuckeurs, Vouloir n°54/55, 1989.

◘ Notes :

- (1) Anne-Marie Duranton-Crabol, Visages de la Nouvelle Droite : Le G.R.E.C.E. et son histoire, Presses de la Fondation Nationale des sciences politiques, Paris, 1988.

- (2) Cf. Nouvelle École n°30, 31-32 (Wagner), n°40 (Jünger), n°41 (Thomas Mann), n°35 (Moeller van den Bruck), n°37 (Heidegger), n°44 (Carl Schmitt). Cf. Éléments n°40 (Jünger).

- (3) Georges Gusdorf, Fondements du savoir romantique, Payot, 1982. G.G., L'homme romantique, Payot, 1984. G.G., Le savoir romantique de la nature, Payot 1985.

- (4) Éditions Mme, Crellestrasse 22, Postfach 327, D1000 Berlin 62.

- Parmi les livres du trio non-conformiste Matthes, Mattheus et Berglleth, citons : Gerd Bergfleth et alii, Zur Kritik der palavernden Aufklärung, 1984 (cf. recension in Vouloir n°27) ; Gerd Bergfleth, Theorie der Verschwendung : Einführung in Georges Batailles Antiökonomie, 1985, 2ème éd. Bernd Mattheus & Axel Matthes (Hrsg.), Ich gestatte mir die Revolte, 1985. Bernd Mattheus, heftige stille, andere notizen, 1986. La somme de Mattheus sur Bataille est en 2 volumes : 1) Georges Bataille : Eine Thanatographie, Band I : Chronik 1897-1939 ; 2) Band II : Chronik 1940-1951. Tous ces volumes sont disponibles chez Matthes u. Seitz Verlag, Mauerkircher Strasse 10, Postfach 860528, D-8000 München 86.

- (5) J.-L. Loubet del Bayle, Les non-conformistes des années 30 : Une tentative de renouvellement de la pensée politique française, Seuil, 1969.

- (6) Pour Nietzsche, il faut aller au-delà de l'homme (moyen) ; cette quête, cette transgression de la moyenne, c'est le propre du “surhomme” et, partant, de ce que l'on pourrait appeler le “surhumanisme”. Dans les circuits néo-droitistes, chez Giorgio Locchi et Guillaume Faye, le terme “surhumanisme” a été utilisé dans ce sens, dans cette volonté de dégager l'homme de sa définition rationaliste/illuministe trop étriquée eu égard à l'abondante diversité du réel.

- (7) Kart Heinz Bohrer, Die Ästhetik des Schreckens : Die pessimistische Romantik und Ernst Jüngers Frühwerk, Ullstein, Frankfurt a.M., 1983 (2° éd.). Les linéaments de la PM se dessinent déjà, pour l’auteur, dans les visions littéraires de Jünger et dans son refus de l'anthropologie modeme/bourgeoise.

- (8) Pour saisir toute la diversité de la PM architecturale, on se référera au livre de Charles Jencks, Die Postmoderne : Der nette Klassizismus in Kunst und Architektur, Klett-Cotta, 1987. La version anglaise de cette ouvrage est parue simultanément : Post-Modernism, Academy Editions, London, 1987 (adresse : ACADEMY GROUP Ltd, 7/8 Holland Street, London W8 4NA).

- (9) Pour comprendre l'importance de Thomas S. Kuhn sur le plan de l'épistémologie scientifique et de la problématique qui nous intéresse ici, on se référera utilement aux explications que nous donne le philosophe Walter Falk dans 2 de ses livres : 1) Vom Strukturalismus zum Potentialismus : Ein Versuch zur Geschichts- und Literaturtheorie (Alber, Freiburg i.B., 1976, pp. 111 à 120 ; recension dans Vouloir, n°15/16, 1985) et 2) Die Ordnung in der Geschichte : Eine alternative Deutung des Fortschritts (Burg Verlag, Sachsenheim, 1985 ; pp. 111 à 114).

- (10) Outre les ouvrages de Feyerabend lui-même, on consultera Angelo Capecci, La scienza tra fede e anarchia : L'epistemologia di P. Feyerabend, La goliardica editrice, Roma, 1977.

- (11) Pour Mohler, la Konservative Revolution fonde de nouvelles valeurs, qui transcendent les frayeurs et les déceptions du nihilisme occidental ; l'Umschlag de la KR n'affronte plus la décadence avec une volonté de la stopper mais, au contraire, en accélérant au maximum ces tendances de façon à ce qu'elles puissent atteindre le plus rapidement possible leur phase terminale. La KR est en ce sens fondatrice de valeurs nouvelles, tout comme la période autour de – 500 l'était pour les Grecs selon Jaspers qui utilise, lui, le terme Achsenzeit, période axiale (cf. Karl Jaspers, Introduction à la philosophie, UGE/10-18, 1965 ; cf. aussi l'interprétation pertinente qu'en donne John Macquarrie, in Existentialism, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1973).

- (12) cf. Giorgio Locchi, L'Essenza del Fascismo : Un saggio e un intervista a cura di Marco Tarchi, Edizioni del Tridente, s.l., 1981.

- (13) cf. Barbara Stolberg-Rilinger, Der Staat als Maschine : Zur politischen Metaphorik des absoluten Fürstenstaats, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, 1986 (recension in Vouloir n°37-38-39, 1987).

- (14) Cf. George Gusdorf, L'homme romantique, op. cit., pp. 243 à 245.

- (15) Georges Gusdorf, lbid., pp. 159 à 173.

- Pour davantage de précision quant à la personnalité de Carus, lire : Ekkchard Meffert, Carl Gustav Carus, Sein Leben - seine Anschauung von der Ende, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart, 1986 ; Carl Gustav Carus, Zwölf Briefe über das Erdleben, Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart, 1986.

- (16) Friedrich Kaulbach, Sprachen der ewigen Wiederkunft : Die Denksituation des Philosophen Nietzsche und ihre Sprachstile, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg, 1985. À propos de ce livre, cf. R. Steuckers, « Regards nouveaux sur Nietzsche », in Orientations n°9, 1987.

- (17) Reinhard Löw, Nietzsche, Sophist und Erzieher : Philosophische Untersuchungen zum systematischen Ort von Friedrich Nietzsches Denken, Acta Humaniora, Weinheim, 1984. À propos de ce livre, cf. R. Steuckers, art. cit. in nota (16).

- (18) À propos du potentialisme de Foucault, cf. Walter Falk, Vom Strukruralismus zum..., op. cit. in nota (9), pp. 120 à 130 ; cf. aussi Walter Falk, Die Ordnung..., op. cit. in nota (9), pp. 114 à 116.

- (19) Gilles Deleuze, Nietzsche, PUF, 1968.

- (20) Helmut Pfotenhauer, Die Kunst als Physiologie : Nietzsches ästhetische Theorie und literarische Produktion, J.B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart, 1985. À propos de ce livre, cf. R. Steuckers, art. cit. in nota (16).

- (21) Pierre Chassard, La philosophie de l'histoire dans la philosophie de Nietzsche, GRECE, Paris, 1975.

- (22) cf. Marco Tarchi, « Dinamica della trasgressione : dal "Né destra né sinistra" all "Se destra e sinistra" », in Trasgressioni n°1, 1986.

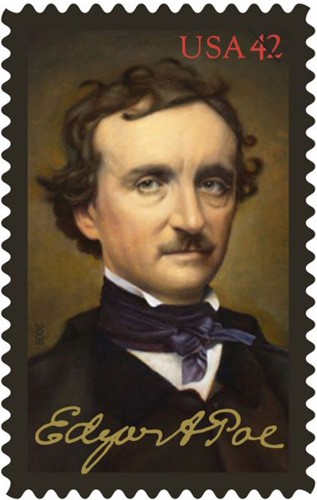

TODAY MARKS the 200th anniversary of the birth of the European-American literary genius and racially concious writer Edgar Allan Poe. I have paid my respects to the eternal memory of Edgar Poe in person at the Poe Museum in Richmond and at his and his beloved Virginia’s grave site in Baltimore, and I offer them again to all who read my words today.

TODAY MARKS the 200th anniversary of the birth of the European-American literary genius and racially concious writer Edgar Allan Poe. I have paid my respects to the eternal memory of Edgar Poe in person at the Poe Museum in Richmond and at his and his beloved Virginia’s grave site in Baltimore, and I offer them again to all who read my words today.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Il y a 170 ans, W. H. Riehl naissait, le 6 mai 1823, à Bieberich dans le pays de Hesse, aux environs de Giessen. Je m’étonne que son nom ne soit plus cité dans les publications conservatrices ou dextristes. Récemment, la très bonne revue allemande “Criticon” a consacré un article à Riehl. En 1976 était paru, dans une collection de livres publiés par l’éditeur Ullstein, le texte “Die bürgerliche Gesellschaft”, un des plus importants écrits socio-politiques de notre auteur, paru pour la première fois en 1851.

Il y a 170 ans, W. H. Riehl naissait, le 6 mai 1823, à Bieberich dans le pays de Hesse, aux environs de Giessen. Je m’étonne que son nom ne soit plus cité dans les publications conservatrices ou dextristes. Récemment, la très bonne revue allemande “Criticon” a consacré un article à Riehl. En 1976 était paru, dans une collection de livres publiés par l’éditeur Ullstein, le texte “Die bürgerliche Gesellschaft”, un des plus importants écrits socio-politiques de notre auteur, paru pour la première fois en 1851.

[1]

[1]

Elle nous fait bouger de plus en plus vite, ou surtout, elle nous fait croire que ce qui est bien c’est de bouger de plus et plus, et de plus en plus vite. En cherchant à aller de plus en plus vite, et à faire les choses de plus en rapidement, l’homme prend le risque de se perdre de vue lui-même. Goethe écrivait : « L’homme tel que nous le connaissons et dans la mesure où il utilise normalement le pouvoir de ses sens est l’instrument physique le plus précis qu’il y ait au monde. Le plus grand péril de la physique moderne est précisément d’avoir séparé l’homme de ses expériences en poursuivant la nature dans un domaine où celle-ci n’est plus perceptible que par nos instruments artificiels. »

Elle nous fait bouger de plus en plus vite, ou surtout, elle nous fait croire que ce qui est bien c’est de bouger de plus et plus, et de plus en plus vite. En cherchant à aller de plus en plus vite, et à faire les choses de plus en rapidement, l’homme prend le risque de se perdre de vue lui-même. Goethe écrivait : « L’homme tel que nous le connaissons et dans la mesure où il utilise normalement le pouvoir de ses sens est l’instrument physique le plus précis qu’il y ait au monde. Le plus grand péril de la physique moderne est précisément d’avoir séparé l’homme de ses expériences en poursuivant la nature dans un domaine où celle-ci n’est plus perceptible que par nos instruments artificiels. » Hartmut Rosa montre que la désynchronisation des évolutions socio-économiques et la dissolution de l’action politique font peser une grave menace sur la possibilité même du progrès social. Déjà Marx et Engels affirmaient ainsi que le capitalisme contient intrinsèquement une tendance à « dissiper tout ce qui est stable et stagne ». Dans Accélération, Hartmut Rosa prend toute la mesure de cette analyse pour construire une véritable « critique sociale du temps susceptible de penser ensemble les transformations du temps, les changements sociaux et le devenir de l’individu et de son rapport au monde ».

Hartmut Rosa montre que la désynchronisation des évolutions socio-économiques et la dissolution de l’action politique font peser une grave menace sur la possibilité même du progrès social. Déjà Marx et Engels affirmaient ainsi que le capitalisme contient intrinsèquement une tendance à « dissiper tout ce qui est stable et stagne ». Dans Accélération, Hartmut Rosa prend toute la mesure de cette analyse pour construire une véritable « critique sociale du temps susceptible de penser ensemble les transformations du temps, les changements sociaux et le devenir de l’individu et de son rapport au monde ».

Der 2009 verstorbene Philosoph Franco Volpi hatte bereits einige kleine Textsammlungen zu Arthur Schopenhauer herausgegeben, darunter Die Kunst, glücklich zu sein. Nun ist ein weiterer Band dieser Reihe erschienen. Die Kunst, sich Respekt zu verschaffen ist eine heitere Lektüre, die gegen einen Aberglauben über die Ehre ankämpft.

Der 2009 verstorbene Philosoph Franco Volpi hatte bereits einige kleine Textsammlungen zu Arthur Schopenhauer herausgegeben, darunter Die Kunst, glücklich zu sein. Nun ist ein weiterer Band dieser Reihe erschienen. Die Kunst, sich Respekt zu verschaffen ist eine heitere Lektüre, die gegen einen Aberglauben über die Ehre ankämpft.

Unlike Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, Louis de Bonald devoted little space to analyzing the French Revolution itself. His focus instead was on understanding the traditional society which had been swept away. His review of Mme. de Staël’s

Unlike Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, Louis de Bonald devoted little space to analyzing the French Revolution itself. His focus instead was on understanding the traditional society which had been swept away. His review of Mme. de Staël’s

Brett and Kate McKay

The Art of Manliness: Classic Skills and Manners for the Modern Man

Cincinnati: How Books, 2009

It’s hard not to like this book. However, it’s really the idea of the book that I like, rather than the book itself. In fact, I almost hesitate to write this review (which will not be wholly positive) because I think the authors have their hearts in the right place, and because I like their website http://artofmanliness.com/

When I showed this book to a young friend of mine he was incredulous: “Do we really need a manual on being a man?” he asked. Well, yes it appears we do. As the authors say in their introduction “something happened in the last fifty years to cause . . . positive manly virtues and skills to disappear from the current generations of men.” They don’t really tell us what they think that something is, but two paragraphs later they remark: “Many people have argued that we need to reinvent what manliness means in the twenty-first century. Usually this means stripping manliness of its masculinity and replacing it with more sensitive feminine qualities. We argue that masculinity doesn’t need to be reinvented.”

I wanted to let out a cheer at this point, but I was sitting in the American Film Academy Café in Greenwich Village, surrounded by young white male geldings and their Asian girlfriends. So I kept my mouth shut and noted to myself that the McKays are clearly not PC, though there are minor nods to political correctness here are there. One gets the feeling that they know more than they are letting on in this book. And one gets the feeling they are employing a simple and sound strategy: to seduce male readers with the natural appeal of traditional manliness – while revealing just-so-much of their political incorrectness so as not to completely alienate their over-socialized readers.

Still, the McKays are pretty socialized themselves, and one sees this immediately on opening the book and finding that it is dedicated to two members of “the greatest generation.” Ugh. Yes, I do think there’s much to admire about my grandfather’s generation, but I long ago came to detest the conventional-minded romanticism about America’s great crusade in WWII. And the very use of the phrase “greatest generation” has become a cliché.

However, the real trouble begins after the introduction, when one finds that the first section of the book is devoted to how to get fitted for a suit. Then we are instructed in how to tie a tie. For some unaccountable reason the tying of the Windsor knot is included here. (Like Ian Fleming, I have always regarded the Windsor knot as a mark of a vain and unserious man.) This is followed by sections on how to select a hat, how to iron a shirt, how to shave, and how not to be a slob at the dinner table. So far so good: I know all this stuff, so I guess I’m pretty manly. Of course, the problem here is that this is all in the realm of appearance. To be fair, the McKays do go on to include much in their book about character, but one must wade through a lot of inessential stuff to get there.

At one point we are instructed in how to deliver a baby. The McKays’ core piece of advice here is “get professional help!” Curiously, this is also the central tenet of their brief lectures on dealing with a snakebite and landing a plane. The baby having been delivered, the reader will find further instructions on how to change a diaper and how to braid your daughter’s hair. (This is what happens when you co-author a book with your wife.) The McKays’ advice on raising children is sound. They advise us not to try and be our child’s best friend.

Once you have tended to your daughter’s snakebite and braided her hair (in that order, please), you can turn to manlier things like how to win a fight, how to break down a door, how to change a flat tire, how to jump start a car, how to go camping, how to navigate by the stars, and how to tie knots. Then it will be Miller time, and you will want some manly friends to hang out with.

The section on male friendship, in fact, is one of the best parts of the book. The McKays remind us that in ancient times “men viewed male friendship as the most fulfilling relationship a person [i.e., a man] could have.” They attribute this, however, to the fact that men saw women as inferior. This is at best a half-truth. The real reason men saw male friendship as more fulfilling than relations with women is because it is. There are vast differences between men and women, and while they may be able to have close, loving relationships they never really understand each other, and their values clash.

Women are primarily concerned with the perpetuation of the species. They are the peacemakers, who just want us all to get along, because their main concern is what Bill Clinton called “the children.” By contrast, men find their greatest fulfillment in achieving something outside the home: they are only fully alive when they are fighting for some kind of value. A man can only be truly understood by another man.

Thus was born what the McKays refer to as “the heroic friendship”: “The heroic friendship was a friendship between two men that was intense on an emotional and intellectual level. Heroic friends felt bound to protect one another from danger.” The McKays devote some discussion to the decline of close male friendships, and they have a lot to say about the disappearance of affection among male friends.