The people of North America and Western Europe now accept a level of ugliness in their daily lives which is almost without precedent in the history of Western civilization. Most of us have become so inured, that the death of millions from starvation and disease draws from us no more than a sigh, or a murmur of protest. Our own city streets, home to legions of the homeless, are ruled by Dope, Inc., the largest industry in the world, and on those streets Americans now murder each other at a rate not seen since the Dark Ages.

At the same time, a thousand smaller horrors are so commonplace as to go unnoticed. Our children spend as much time sitting in front of television sets as they do in school, watching with glee, scenes of torture and death which might have shocked an audience in the Roman Coliseum. Music is everywhere, almost unavoidable—but it does not uplift, nor even tranquilize—it claws at the ears, sometimes spitting out an obscenity. Our plastic arts are ugly, our architecture is ugly, our clothes are ugly. There have certainly been periods in history where mankind has lived through similar kinds of brutishness, but our time is crucially different. Our post-World War II era is the first in history in which these horrors are completely avoidable. Our time is the first to have the technology and resources to feed, house, educate, and humanely employ every person on earth, no matter what the growth of population. Yet, when shown the ideas and proven technologies that can solve the most horrendous problems, most people retreat into implacable passivity. We have become not only ugly, but impotent.

Nonetheless, there is no reason why our current moral-cultural situation had to lawfully or naturally turn out as it has; and there is no reason why this tyranny of ugliness should continue one instant longer.

Consider the situation just one hundred years ago, in the early 1890's. In music, Claude Debussy was completing his Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, and Arnold Schönberg was beginning to experiment with atonalism; at the same time, Dvorak was working on his Ninth Symphony, while Brahms and Verdi still lived. Edvard Munch was showing The Scream, and Paul Gauguin his Self-Portrait with Halo, but in America, Thomas Eakins was still painting and teaching. Mechanists like Helmholtz and Mach held major university chairs of science, alongside the students of Riemann and Cantor. Pope Leo XIII's De Rerum Novarum was being promulgated, even as sections of the Socialist Second International were turning terrorist, and preparing for class war.

The optimistic belief that one could compose music like Beethoven, paint like Rembrandt, study the universe like Plato and Nicolaus of Cusa, and change world society without violence, was alive in the 1890's—admittedly, it was weak, and under siege, but it was hardly dead. Yet, within twenty short years, these Classical traditions of human civilization had been all but swept away, and the West had committed itself to a series of wars of inconceivable carnage.

What started about a hundred years ago, was what might be called a counter-Renaissance. The Renaissance of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was a religious celebration of the human soul and mankind's potential for growth. Beauty in art could not be conceived of as anything less than the expression of the most-advanced scientific principles, as demonstrated by the geometry upon which Leonardo's perspective and Brunelleschi's great Dome of Florence Cathedral are based. The finest minds of the day turned their thoughts to the heavens and the mighty waters, and mapped the solar system and the route to the New World, planning great projects to turn the course of rivers for the betterment of mankind. About a hundred years ago, it was as though a long checklist had been drawn up, with all of the wonderful achievements of the Renaissance itemized—each to be reversed. As part of this "New Age" movement, as it was then called, the concept of the human soul was undermined by the most vociferous intellectual campaign in history; art was forcibly separated from science, and science itself was made the object of deep suspicion. Art was made ugly because, it was said, life had become ugly.

The cultural shift away from the Renaissance ideas that built the modern world, was due to a kind of freemasonry of ugliness. In the beginning, it was a formal political conspiracy to popularize theories that were specifically designed to weaken the soul of Judeo-Christian civilization in such a way as to make people believe that creativity was not possible, that adherence to universal truth was evidence of authoritarianism, and that reason itself was suspect. This conspiracy was decisive in planning and developing, as means of social manipulation, the vast new sister industries of radio, television, film, recorded music, advertising, and public opinion polling. The pervasive psychological hold of the media was purposely fostered to create the passivity and pessimism which afflict our populations today. So successful was this conspiracy, that it has become embedded in our culture; it no longer needs to be a "conspiracy," for it has taken on a life of its own. Its successes are not debatable—you need only turn on the radio or television. Even the nomination of a Supreme Court Justice is deformed into an erotic soap opera, with the audience rooting from the sidelines for their favorite character.

Our universities, the cradle of our technological and intellectual future, have become overwhelmed by Comintern-style New Age "Political Correctness." With the collapse of the Soviet Union, our campuses now represent the largest concentration of Marxist dogma in the world. The irrational adolescent outbursts of the 1960's have become institutionalized into a "permanent revolution." Our professors glance over their shoulders, hoping the current mode will blow over before a student's denunciation obliterates a life's work; some audio-tape their lectures, fearing accusations of "insensitivity" by some enraged "Red Guard." Students at the University of Virginia recently petitioned successfully to drop the requirement to read Homer, Chaucer, and other DEMS ("Dead European Males") because such writings are considered ethnocentric, phallocentric, and generally inferior to the "more relevant" Third World, female, or homosexual authors.

This is not the academy of a republic; this is Hitler's Gestapo and Stalin's NKVD rooting out "deviationists," and banning books—the only thing missing is the public bonfire.

We will have to face the fact that the ugliness we see around us has been consciously fostered and organized in such a way, that a majority of the population is losing the cognitive ability to transmit to the next generation, the ideas and methods upon which our civilization was built. The loss of that ability is the primary indicator of a Dark Age. And, a new Dark Age is exactly what we are in. In such situations, the record of history is unequivocal: either we create a Renaissance—a rebirth of the fundamental principles upon which civilization originated—or, our civilization dies.

I. The Frankfurt School: Bolshevik Intelligentsia

The single, most important organizational component of this conspiracy was a Communist thinktank called the Institute for Social Research (I.S.R.), but popularly known as the Frankfurt School.

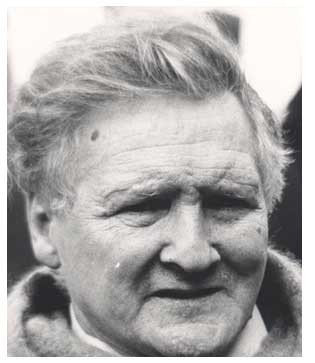

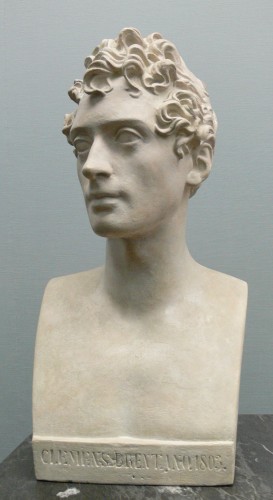

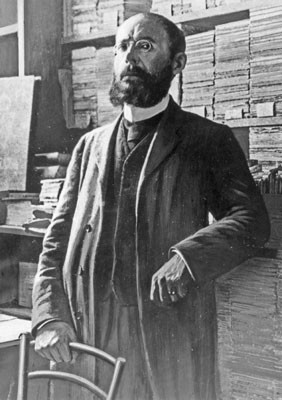

In the heady days immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, it was widely believed that proletarian revolution would momentarily sweep out of the Urals into Europe and, ultimately, North America. It did not; the only two attempts at workers' government in the West— in Munich and Budapest—lasted only months. The Communist International (Comintern) therefore began several operations to determine why this was so. One such was headed by Georg Lukacs, a Hungarian aristocrat, son of one of the Hapsburg Empire's leading bankers. Trained in Germany and already an important literary theorist, Lukacs became a Communist during World War I, writing as he joined the party, "Who will save us from Western civilization?" Lukacs was well-suited to the Comintern task: he had been one of the Commissars of Culture during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet in Budapest in 1919; in fact, modern historians link the shortness of the Budapest experiment to Lukacs' orders mandating sex education in the schools, easy access to contraception, and the loosening of divorce laws—all of which revulsed Hungary's Roman Catholic population.

In the heady days immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, it was widely believed that proletarian revolution would momentarily sweep out of the Urals into Europe and, ultimately, North America. It did not; the only two attempts at workers' government in the West— in Munich and Budapest—lasted only months. The Communist International (Comintern) therefore began several operations to determine why this was so. One such was headed by Georg Lukacs, a Hungarian aristocrat, son of one of the Hapsburg Empire's leading bankers. Trained in Germany and already an important literary theorist, Lukacs became a Communist during World War I, writing as he joined the party, "Who will save us from Western civilization?" Lukacs was well-suited to the Comintern task: he had been one of the Commissars of Culture during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet in Budapest in 1919; in fact, modern historians link the shortness of the Budapest experiment to Lukacs' orders mandating sex education in the schools, easy access to contraception, and the loosening of divorce laws—all of which revulsed Hungary's Roman Catholic population.

Fleeing to the Soviet Union after the counter-revolution, Lukacs was secreted into Germany in 1922, where he chaired a meeting of Communist-oriented sociologists and intellectuals. This meeting founded the Institute for Social Research. Over the next decade, the Institute worked out what was to become the Comintern's most successful psychological warfare operation against the capitalist West.

Lukacs identified that any political movement capable of bringing Bolshevism to the West would have to be, in his words, "demonic"; it would have to "possess the religious power which is capable of filling the entire soul; a power that characterized primitive Christianity." However, Lukacs suggested, such a "messianic" political movement could only succeed when the individual believes that his or her actions are determined by "not a personal destiny, but the destiny of the community" in a world "that has been abandoned by God [emphasis added-MJM]." Bolshevism worked in Russia because that nation was dominated by a peculiar gnostic form of Christianty typified by the writings of Fyodor Dostoyevsky. "The model for the new man is Alyosha Karamazov," said Lukacs, referring to the Dostoyevsky character who willingly gave over his personal identity to a holy man, and thus ceased to be "unique, pure, and therefore abstract."

This abandonment of the soul's uniqueness also solves the problem of "the diabolic forces lurking in all violence" which must be unleashed in order to create a revolution. In this context, Lukacs cited the Grand Inquisitor section of Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, noting that the Inquisitor who is interrogating Jesus, has resolved the issue of good and evil: once man has understood his alienation from God, then any act in the service of the "destiny of the community" is justified; such an act can be "neither crime nor madness.... For crime and madness are objectifications of transcendental homelessness."

According to an eyewitness, during meetings of the Hungarian Soviet leadership in 1919 to draw up lists for the firing squad, Lukacs would often quote the Grand Inquisitor: "And we who, for their happiness, have taken their sins upon ourselves, we stand before you and say, 'Judge us if you can and if you dare.' "

The Problem of Genesis

What differentiated the West from Russia, Lukacs identified, was a Judeo-Christian cultural matrix which emphasized exactly the uniqueness and sacredness of the individual which Lukacs abjured. At its core, the dominant Western ideology maintained that the individual, through the exercise of his or her reason, could discern the Divine Will in an unmediated relationship. What was worse, from Lukacs' standpoint: this reasonable relationship necessarily implied that the individual could and should change the physical universe in pursuit of the Good; that Man should have dominion over Nature, as stated in the Biblical injunction in Genesis. The problem was, that as long as the individual had the belief—or even the hope of the belief—that his or her divine spark of reason could solve the problems facing society, then that society would never reach the state of hopelessness and alienation which Lukacs recognized as the necessary prerequisite for socialist revolution.

The task of the Frankfurt School, then, was first, to undermine the Judeo-Christian legacy through an "abolition of culture" (Aufhebung der Kultur in Lukacs' German); and, second, to determine new cultural forms which would increase the alienation of the population, thus creating a "new barbarism." To this task, there gathered in and around the Frankfurt School an incredible assortment of not only Communists, but also non-party socialists, radical phenomenologists, Zionists, renegade Freudians, and at least a few members of a self-identified "cult of Astarte." The variegated membership reflected, to a certain extent, the sponsorship: although the Institute for Social Research started with Comintern support, over the next three decades its sources of funds included various German and American universities, the Rockefeller Foundation, Columbia Broadcasting System, the American Jewish Committee, several American intelligence services, the Office of the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany, the International Labour Organization, and the Hacker Institute, a posh psychiatric clinic in Beverly Hills.

Similarly, the Institute's political allegiances: although top personnel maintained what might be called a sentimental relationship to the Soviet Union (and there is evidence that some of them worked for Soviet intelligence into the 1960's), the Institute saw its goals as higher than that of Russian foreign policy. Stalin, who was horrified at the undisciplined, "cosmopolitan" operation set up by his predecessors, cut the Institute off in the late 1920's, forcing Lukacs into "self-criticism," and briefly jailing him as a German sympathizer during World War II.

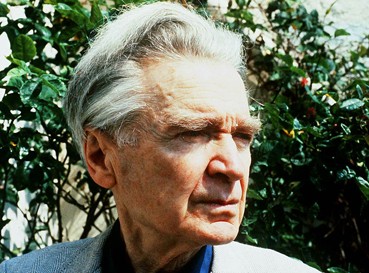

Lukacs survived to briefly take up his old post as Minister of Culture during the anti-Stalinist Imre Nagy regime in Hungary. Of the other top Institute figures, the political perambulations of Herbert Marcuse are typical. He started as a Communist; became a protégé of philosopher Martin Heidegger even as the latter was joining the Nazi Party; coming to America, he worked for the World War II Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and later became the U.S. State Department's top analyst of Soviet policy during the height of the McCarthy period; in the 1960's, he turned again, to become the most important guru of the New Left; and he ended his days helping to found the environmentalist extremist Green Party in West Germany.

Lukacs survived to briefly take up his old post as Minister of Culture during the anti-Stalinist Imre Nagy regime in Hungary. Of the other top Institute figures, the political perambulations of Herbert Marcuse are typical. He started as a Communist; became a protégé of philosopher Martin Heidegger even as the latter was joining the Nazi Party; coming to America, he worked for the World War II Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and later became the U.S. State Department's top analyst of Soviet policy during the height of the McCarthy period; in the 1960's, he turned again, to become the most important guru of the New Left; and he ended his days helping to found the environmentalist extremist Green Party in West Germany.

In all this seeming incoherence of shifting positions and contradictory funding, there is no ideological conflict. The invariant is the desire of all parties to answer Lukacs' original question: "Who will save us from Western civilization?"

Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin

Perhaps the most important, if least-known, of the Frankfurt School's successes was the shaping of the electronic media of radio and television into the powerful instruments of social control which they represent today. This grew out of the work originally done by two men who came to the Institute in the late 1920's, Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin.

Perhaps the most important, if least-known, of the Frankfurt School's successes was the shaping of the electronic media of radio and television into the powerful instruments of social control which they represent today. This grew out of the work originally done by two men who came to the Institute in the late 1920's, Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin.

After completing studies at the University of Frankfurt, Walter Benjamin planned to emigrate to Palestine in 1924 with his friend Gershom Scholem (who later became one of Israel's most famous philosophers, as well as Judaism's leading gnostic), but was prevented by a love affair with Asja Lacis, a Latvian actress and Comintern stringer. Lacis whisked him off to the Italian island of Capri, a cult center from the time of the Emperor Tiberius, then used as a Comintern training base; the heretofore apolitical Benjamin wrote Scholem from Capri, that he had found "an existential liberation and an intensive insight into the actuality of radical communism."

Lacis later took Benjamin to Moscow for further indoctrination, where he met playwright Bertolt Brecht, with whom he would begin a long collaboration; soon thereafter, while working on the first German translation of the drug-enthusiast French poet Baudelaire, Benjamin began serious experimentation with hallucinogens. In 1927, he was in Berlin as part of a group led by Adorno, studying the works of Lukacs; other members of the study group included Brecht and his composer-partner Kurt Weill; Hans Eisler, another composer who would later become a Hollywood film score composer and co-author with Adorno of the textbook Composition for the Film; the avant-garde photographer Imre Moholy-Nagy; and the conductor Otto Klemperer.

From 1928 to 1932, Adorno and Benjamin had an intensive collaboration, at the end of which they began publishing articles in the Institute's journal, the Zeitschrift fär Sozialforschung. Benjamin was kept on the margins of the Institute, largely due to Adorno, who would later appropriate much of his work. As Hitler came to power, the Institute's staff fled, but, whereas most were quickly spirited away to new deployments in the U.S. and England, there were no job offers for Benjamin, probably due to the animus of Adorno. He went to France, and, after the German invasion, fled to the Spanish border; expecting momentary arrest by the Gestapo, he despaired and died in a dingy hotel room of self-administered drug overdose.

From 1928 to 1932, Adorno and Benjamin had an intensive collaboration, at the end of which they began publishing articles in the Institute's journal, the Zeitschrift fär Sozialforschung. Benjamin was kept on the margins of the Institute, largely due to Adorno, who would later appropriate much of his work. As Hitler came to power, the Institute's staff fled, but, whereas most were quickly spirited away to new deployments in the U.S. and England, there were no job offers for Benjamin, probably due to the animus of Adorno. He went to France, and, after the German invasion, fled to the Spanish border; expecting momentary arrest by the Gestapo, he despaired and died in a dingy hotel room of self-administered drug overdose.

Benjamin's work remained almost completely unknown until 1955, when Scholem and Adorno published an edition of his material in Germany. The full revival occurred in 1968, when Hannah Arendt, Heidegger's former mistress and a collaborator of the Institute in America, published a major article on Benjamin in the New Yorker magazine, followed in the same year by the first English translations of his work. Today, every university bookstore in the country boasts a full shelf devoted to translations of every scrap Benjamin wrote, plus exegesis, all with 1980's copyright dates.

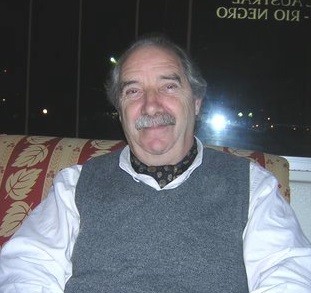

Adorno was younger than Benjamin, and as aggressive as the older man was passive. Born Teodoro Wiesengrund-Adorno to a Corsican family, he was taught the piano at an early age by an aunt who lived with the family and had been the concert accompanist to the international opera star Adelina Patti. It was generally thought that Theodor would become a professional musician, and he studied with Bernard Sekles, Paul Hindemith's teacher. However, in 1918, while still a gymnasium student, Adorno met Siegfried Kracauer. Kracauer was part of a Kantian-Zionist salon which met at the house of Rabbi Nehemiah Nobel in Frankfurt; other members of the Nobel circle included philosopher Martin Buber, writer Franz Rosenzweig, and two students, Leo Lowenthal and Erich Fromm. Kracauer, Lowenthal, and Fromm would join the I.S.R. two decades later. Adorno engaged Kracauer to tutor him in the philosophy of Kant; Kracauer also introduced him to the writings of Lukacs and to Walter Benjamin, who was around the Nobel clique.

Adorno was younger than Benjamin, and as aggressive as the older man was passive. Born Teodoro Wiesengrund-Adorno to a Corsican family, he was taught the piano at an early age by an aunt who lived with the family and had been the concert accompanist to the international opera star Adelina Patti. It was generally thought that Theodor would become a professional musician, and he studied with Bernard Sekles, Paul Hindemith's teacher. However, in 1918, while still a gymnasium student, Adorno met Siegfried Kracauer. Kracauer was part of a Kantian-Zionist salon which met at the house of Rabbi Nehemiah Nobel in Frankfurt; other members of the Nobel circle included philosopher Martin Buber, writer Franz Rosenzweig, and two students, Leo Lowenthal and Erich Fromm. Kracauer, Lowenthal, and Fromm would join the I.S.R. two decades later. Adorno engaged Kracauer to tutor him in the philosophy of Kant; Kracauer also introduced him to the writings of Lukacs and to Walter Benjamin, who was around the Nobel clique.

In 1924, Adorno moved to Vienna, to study with the atonalist composers Alban Berg and Arnold Schönberg, and became connected to the avant-garde and occult circle around the old Marxist Karl Kraus. Here, he not only met his future collaborator, Hans Eisler, but also came into contact with the theories of Freudian extremist Otto Gross. Gross, a long-time cocaine addict, had died in a Berlin gutter in 1920, while on his way to help the revolution in Budapest; he had developed the theory that mental health could only be achieved through the revival of the ancient cult of Astarte, which would sweep away monotheism and the "bourgeois family."

In 1924, Adorno moved to Vienna, to study with the atonalist composers Alban Berg and Arnold Schönberg, and became connected to the avant-garde and occult circle around the old Marxist Karl Kraus. Here, he not only met his future collaborator, Hans Eisler, but also came into contact with the theories of Freudian extremist Otto Gross. Gross, a long-time cocaine addict, had died in a Berlin gutter in 1920, while on his way to help the revolution in Budapest; he had developed the theory that mental health could only be achieved through the revival of the ancient cult of Astarte, which would sweep away monotheism and the "bourgeois family."

Saving Marxist Aesthetics

By 1928, Adorno and Benjamin had satisfied their intellectual wanderlust, and settled down at the I.S.R. in Germany to do some work. As subject, they chose an aspect of the problem posed by Lukacs: how to give aesthetics a firmly materialistic basis. It was a question of some importance, at the time. Official Soviet discussions of art and culture, with their wild gyrations into "socialist realism" and "proletkult," were idiotic, and only served to discredit Marxism's claim to philosophy among intellectuals. Karl Marx's own writings on the subject were sketchy and banal, at best.

In essence, Adorno and Benjamin's problem was Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Leibniz had once again obliterated the centuries-old gnostic dualism dividing mind and body, by demonstrating that matter does not think. A creative act in art or science apprehends the truth of the physical universe, but it is not determined by that physical universe. By self-consciously concentrating the past in the present to effect the future, the creative act, properly defined, is as immortal as the soul which envisions the act. This has fatal philosophical implications for Marxism, which rests entirely on the hypothesis that mental activity is determined by the social relations excreted by mankind's production of its physical existence.

Marx sidestepped the problem of Leibniz, as did Adorno and Benjamin, although the latter did it with a lot more panache. It is wrong, said Benjamin in his first articles on the subject, to start with the reasonable, hypothesizing mind as the basis of the development of civilization; this is an unfortunate legacy of Socrates. As an alternative, Benjamin posed an Aristotelian fable in interpretation of Genesis: Assume that Eden were given to Adam as the primordial physical state. The origin of science and philosophy does not lie in the investigation and mastery of nature, but in the naming of the objects of nature; in the primordial state, to name a thing was to say all there was to say about that thing. In support of this, Benjamin cynically recalled the opening lines of the Gospel according to St. John, carefully avoiding the philosophically-broader Greek, and preferring the Vulgate (so that, in the phrase "In the beginning was the Word," the connotations of the original Greek word logos—speech, reason, ratiocination, translated as "Word"—are replaced by the narrower meaning of the Latin word verbum). After the expulsion from Eden and God's requirement that Adam eat his bread earned by the sweat of his face (Benjamin's Marxist metaphor for the development of economies), and God's further curse of Babel on Nimrod (that is, the development of nation-states with distinct languages, which Benjamin and Marx viewed as a negative process away from the "primitive communism" of Eden), humanity became "estranged" from the physical world.

Thus, Benjamin continued, objects still give off an "aura" of their primordial form, but the truth is now hopelessly elusive. In fact, speech, written language, art, creativity itself—that by which we master physicality—merely furthers the estrangement by attempting, in Marxist jargon, to incorporate objects of nature into the social relations determined by the class structure dominant at that point in history. The creative artist or scientist, therefore, is a vessel, like Ion the rhapsode as he described himself to Socrates, or like a modern "chaos theory" advocate: the creative act springs out of the hodgepodge of culture as if by magic. The more that bourgeois man tries to convey what he intends about an object, the less truthful he becomes; or, in one of Benjamin's most oft-quoted statements, "Truth is the death of intention."

This philosophical sleight-of-hand allows one to do several destructive things. By making creativity historically-specific, you rob it of both immortality and morality. One cannot hypothesize universal truth, or natural law, for truth is completely relative to historical development. By discarding the idea of truth and error, you also may throw out the "obsolete" concept of good and evil; you are, in the words of Friedrich Nietzsche, "beyond good and evil." Benjamin is able, for instance, to defend what he calls the "Satanism" of the French Symbolists and their Surrealist successors, for at the core of this Satanism "one finds the cult of evil as a political device ... to disinfect and isolate against all moralizing dilettantism" of the bourgeoisie. To condemn the Satanism of Rimbaud as evil, is as incorrect as to extol a Beethoven quartet or a Schiller poem as good; for both judgments are blind to the historical forces working unconsciously on the artist.

Thus, we are told, the late Beethoven's chord structure was striving to be atonal, but Beethoven could not bring himself consciously to break with the structured world of Congress of Vienna Europe (Adorno's thesis); similarly, Schiller really wanted to state that creativity was the liberation of the erotic, but as a true child of the Enlightenment and Immanuel Kant, he could not make the requisite renunciation of reason (Marcuse's thesis). Epistemology becomes a poor relation of public opinion, since the artist does not consciously create works in order to uplift society, but instead unconsciously transmits the ideological assumptions of the culture into which he was born. The issue is no longer what is universally true, but what can be plausibly interpreted by the self-appointed guardians of the Zeitgeist.

Thus, for the Frankfort School, the goal of a cultural elite in the modern, "capitalist" era must be to strip away the belief that art derives from the self-conscious emulation of God the Creator; "religious illumination," says Benjamin, must be shown to "reside in a profane illumination, a materialistic, anthropological inspiration, to which hashish, opium, or whatever else can give an introductory lesson." At the same time, new cultural forms must be found to increase the alienation of the population, in order for it to understand how truly alienated it is to live without socialism. "Do not build on the good old days, but on the bad new ones," said Benjamin.

The proper direction in painting, therefore, is that taken by the late Van Gogh, who began to paint objects in disintegration, with the equivalent of a hashish-smoker's eye that "loosens and entices things out of their familiar world." In music, "it is not suggested that one can compose better today" than Mozart or Beethoven, said Adorno, but one must compose atonally, for atonalism is sick, and "the sickness, dialectically, is at the same time the cure....The extraordinarily violent reaction protest which such music confronts in the present society ... appears nonetheless to suggest that the dialectical function of this music can already be felt ... negatively, as 'destruction.' "

The purpose of modern art, literature, and music must be to destroy the uplifting—therefore, bourgeois — potential of art, literature, and music, so that man, bereft of his connection to the divine, sees his only creative option to be political revolt. "To organize pessimism means nothing other than to expel the moral metaphor from politics and to discover in political action a sphere reserved one hundred percent for images." Thus, Benjamin collaborated with Brecht to work these theories into practical form, and their joint effort culminated in the Verfremdungseffekt ("estrangement effect"), Brecht's attempt to write his plays so as to make the audience leave the theatre demoralized and aimlessly angry.

The Adorno-Benjamin analysis represents almost the entire theoretical basis of all the politically correct aesthetic trends which now plague our universities. The Poststructuralism of Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, the Semiotics of Umberto Eco, the Deconstructionism of Paul DeMan, all openly cite Benjamin as the source of their work. The Italian terrorist Eco's best-selling novel, The Name of the Rose, is little more than a paean to Benjamin; DeMan, the former Nazi collaborator in Belgium who became a prestigious Yale professor, began his career translating Benjamin; Barthes' infamous 1968 statement that "[t]he author is dead," is meant as an elaboration of Benjamin's dictum on intention. Benjamin has actually been called the heir of Leibniz and of Wilhelm von Humboldt, the philologist collaborator of Schiller whose educational reforms engendered the tremendous development of Germany in the nineteenth century. Even as recently as September 1991, the Washington Post referred to Benjamin as "the finest German literary theorist of the century (and many would have left off that qualifying German)."

The Adorno-Benjamin analysis represents almost the entire theoretical basis of all the politically correct aesthetic trends which now plague our universities. The Poststructuralism of Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, the Semiotics of Umberto Eco, the Deconstructionism of Paul DeMan, all openly cite Benjamin as the source of their work. The Italian terrorist Eco's best-selling novel, The Name of the Rose, is little more than a paean to Benjamin; DeMan, the former Nazi collaborator in Belgium who became a prestigious Yale professor, began his career translating Benjamin; Barthes' infamous 1968 statement that "[t]he author is dead," is meant as an elaboration of Benjamin's dictum on intention. Benjamin has actually been called the heir of Leibniz and of Wilhelm von Humboldt, the philologist collaborator of Schiller whose educational reforms engendered the tremendous development of Germany in the nineteenth century. Even as recently as September 1991, the Washington Post referred to Benjamin as "the finest German literary theorist of the century (and many would have left off that qualifying German)."

Readers have undoubtedly heard one or another horror story about how an African-American Studies Department has procured a ban on Othello, because it is "racist," or how a radical feminist professor lectured a Modern Language Association meeting on the witches as the "true heroines" of Macbeth. These atrocities occur because the perpetrators are able to plausibly demonstrate, in the tradition of Benjamin and Adorno, that Shakespeare's intent is irrelevant; what is important, is the racist or phallocentric "subtext" of which Shakespeare was unconscious when he wrote.

When the local Women's Studies or Third World Studies Department organizes students to abandon classics in favor of modern Black and feminist authors, the reasons given are pure Benjamin. It is not that these modern writers are better, but they are somehow more truthful because their alienated prose reflects the modern social problems of which the older authors were ignorant! Students are being taught that language itself is, as Benjamin said, merely a conglomeration of false "names" foisted upon society by its oppressors, and are warned against "logocentrism," the bourgeois over-reliance on words.

If these campus antics appear "retarded" (in the words of Adorno), that is because they are designed to be. The Frankfurt School's most important breakthrough consists in the realization that their monstrous theories could become dominant in the culture, as a result of the changes in society brought about by what Benjamin called "the age of mechanical reproduction of art."

II. The Establishment Goes Bolshevik:

"Entertainment" Replaces Art

Before the twentieth century, the distinction between art and "entertainment" was much more pronounced. One could be entertained by art, certainly, but the experience was active, not passive. On the first level, one had to make a conscious choice to go to a concert, to view a certain art exhibit, to buy a book or piece of sheet music. It was unlikely that any more than an infinitesimal fraction of the population would have the opportunity to see King Lear or hear Beethoven's Ninth Symphony more than once or twice in a lifetime. Art demanded that one bring one's full powers of concentration and knowledge of the subject to bear on each experience, or else the experience were considered wasted. These were the days when memorization of poetry and whole plays, and the gathering of friends and family for a "parlor concert," were the norm, even in rural households. These were also the days before "music appreciation"; when one studied music, as many did, they learned to play it, not appreciate it.

However, the new technologies of radio, film, and recorded music represented, to use the appropriate Marxist buzz-word, a dialectical potential. On the one hand, these technologies held out the possibility of bringing the greatest works of art to millions of people who would otherwise not have access to them. On the other, the fact that the experience was infinitely reproducible could tend to disengage the audience's mind, making the experience less sacred, thus increasing alienation. Adorno called this process, "demythologizing." This new passivity, Adorno hypothesized in a crucial article published in 1938, could fracture a musical composition into the "entertaining" parts which would be "fetishized" in the memory of the listener, and the difficult parts, which would be forgotten. Adorno continues,

The counterpart to the fetishism is a regression of listening. This does not mean a relapse of the individual listener into an earlier phase of his own development, nor a decline in the collective general level, since the millions who are reached musically for the first time by today's mass communications cannot be compared with the audiences of the past. Rather, it is the contemporary listening which has regressed, arrested at the infantile stage. Not only do the listening subjects lose, along with the freedom of choice and responsibility, the capacity for the conscious perception of music .... [t]hey fluctuate between comprehensive forgetting and sudden dives into recognition. They listen atomistically and dissociate what they hear, but precisely in this dissociation they develop certain capacities which accord less with the traditional concepts of aesthetics than with those of football or motoring. They are not childlike ... but they are childish; their primitivism is not that of the undeveloped, but that of the forcibly retarded. [emphasis aded]

This conceptual retardation and preconditioning caused by listening, suggested that programming could determine preference. The very act of putting, say, a Benny Goodman number next to a Mozart sonata on the radio, would tend to amalgamate both into entertaining "music-on-the-radio" in the mind of the listener. This meant that even new and unpalatable ideas could become popular by "re-naming" them through the universal homogenizer of the culture industry. As Benjamin puts it,

Mechanical reproduction of art changes the reaction of the masses toward art. The reactionary attitude toward a Picasso painting changes into a progressive reaction toward a Chaplin movie. The progressive reaction is characterized by the direct, intimate fusion of visual and emotional enjoyment with the orientation of the expert.... With regard to the screen, the critical and receptive attitudes of the public coincide. The decisive reason for this is that the individual reactions are predetermined by the mass audience response they are about to produce, and this is nowhere more pronounced than in the film.

At the same time, the magic power of the media could be used to re-define previous ideas. "Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Beethoven will all make films," concluded Benjamin, quoting the French film pioneer Abel Gance, "... all legends, all mythologies, all myths, all founders of religions, and the very religions themselves ... await their exposed resurrection."

Social Control: The "Radio Project"

Here, then, were some potent theories of social control. The great possibilities of this Frankfurt School media work were probably the major contributing factor in the support given the I.S.R. by the bastions of the Establishment, after the Institute transferred its operations to America in 1934.

In 1937, the Rockefeller Foundation began funding research into the social effects of new forms of mass media, particularly radio. Before World War I, radio had been a hobbyist's toy, with only 125,000 receiving sets in the entire U.S.; twenty years later, it had become the primary mode of entertainment in the country; out of 32 million American families in 1937, 27.5 million had radios — a larger percentage than had telephones, automobiles, plumbing, or electricity! Yet, almost no systematic research had been done up to this point. The Rockefeller Foundation enlisted several universities, and headquartered this network at the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. Named the Office of Radio Research, it was popularly known as "the Radio Project."

The director of the Project was Paul Lazersfeld, the foster son of Austrian Marxist economist Rudolph Hilferding, and a long-time collaborator of the I.S.R. from the early 1930's. Under Lazersfeld was Frank Stanton, a recent Ph.D. in industrial psychology from Ohio State, who had just been made research director of Columbia Broadcasting System—a grand title but a lowly position. After World War II, Stanton became president of the CBS News Division, and ultimately president of CBS at the height of the TV network's power; he also became Chairman of the Board of the RAND Corporation, and a member of President Lyndon Johnson's "kitchen cabinet." Among the Project's researchers were Herta Herzog, who married Lazersfeld and became the first director of research for the Voice of America; and Hazel Gaudet, who became one of the nation's leading political pollsters. Theodor Adorno was named chief of the Project's music section.

The director of the Project was Paul Lazersfeld, the foster son of Austrian Marxist economist Rudolph Hilferding, and a long-time collaborator of the I.S.R. from the early 1930's. Under Lazersfeld was Frank Stanton, a recent Ph.D. in industrial psychology from Ohio State, who had just been made research director of Columbia Broadcasting System—a grand title but a lowly position. After World War II, Stanton became president of the CBS News Division, and ultimately president of CBS at the height of the TV network's power; he also became Chairman of the Board of the RAND Corporation, and a member of President Lyndon Johnson's "kitchen cabinet." Among the Project's researchers were Herta Herzog, who married Lazersfeld and became the first director of research for the Voice of America; and Hazel Gaudet, who became one of the nation's leading political pollsters. Theodor Adorno was named chief of the Project's music section.

Despite the official gloss, the activities of the Radio Project make it clear that its purpose was to test empirically the Adorno-Benjamin thesis that the net effect of the mass media could be to atomize and increase lability—what people would later call "brainwashing."

Soap Operas and the Invasion from Mars

The first studies were promising. Herta Herzog produced "On Borrowed Experiences," the first comprehensive research on soap operas. The "serial radio drama" format was first used in 1929, on the inspiration of the old, cliff-hanger "Perils of Pauline" film serial. Because these little radio plays were highly melodramatic, they became popularly identified with Italian grand opera; because they were often sponsored by soap manufacturers, they ended up with the generic name, "soap opera."

The first studies were promising. Herta Herzog produced "On Borrowed Experiences," the first comprehensive research on soap operas. The "serial radio drama" format was first used in 1929, on the inspiration of the old, cliff-hanger "Perils of Pauline" film serial. Because these little radio plays were highly melodramatic, they became popularly identified with Italian grand opera; because they were often sponsored by soap manufacturers, they ended up with the generic name, "soap opera."

Until Herzog's work, it was thought that the immense popularity of this format was largely with women of the lowest socioeconomic status who, in the restricted circumstances of their lives, needed a helpful escape to exotic places and romantic situations. A typical article from that period by two University of Chicago psychologists, "The Radio Day-Time Serial: Symbol Analysis" published in the Genetic Psychology Monographs, solemnly emphasized the positive, claiming that the soaps "function very much like the folk tale, expressing the hopes and fears of its female audience, and on the whole contribute to the integration of their lives into the world in which they live."

Herzog found that there was, in fact, no correlation to socioeconomic status. What is more, there was surprisingly little correlation to content. The key factor — as Adorno and Benjamin's theories suggested it would be — was the form itself of the serial; women were being effectively addicted to the format, not so much to be entertained or to escape, but to "find out what happens next week." In fact, Herzog found, you could almost double the listenership of a radio play by dividing it into segments.

Modern readers will immediately recognize that this was not a lesson lost on the entertainment industry. Nowadays, the serial format has spread to children's programming and high-budget prime time shows. The most widely watched shows in the history of television, remain the "Who Killed JR?" installment of Dallas, and the final episode of M*A*S*H, both of which were premised on a "what happens next?" format. Even feature films, like the Star Wars and Back to the Future trilogies, are now produced as serials, in order to lock in a viewership for the later installments. The humble daytime soap also retains its addictive qualities in the current age: 70% of all American women over eighteen now watch at least two of these shows each day, and there is a fast-growing viewership among men and college students of both sexes.

The Radio Project's next major study was an investigation into the effects of Orson Welles' Halloween 1938 radioplay based on H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds. Six million people heard the broadcast realistically describing a Martian invasion force landing in rural New Jersey. Despite repeated and clear statements that the show was fictional, approximately 25% of the listeners thought it was real, some panicking outright. The Radio Project researchers found that a majority of the people who panicked did not think that men from Mars had invaded; they actually thought that the Germans had invaded.

It happened this way. The listeners had been psychologically pre-conditioned by radio reports from the Munich crisis earlier that year. During that crisis, CBS's man in Europe, Edward R. Murrow, hit upon the idea of breaking into regular programming to present short news bulletins. For the first time in broadcasting, news was presented not in longer analytical pieces, but in short clips—what we now call "audio bites." At the height of the crisis, these flashes got so numerous, that, in the words of Murrow's producer Fred Friendly, "news bulletins were interrupting news bulletins." As the listeners thought that the world was moving to the brink of war, CBS ratings rose dramatically. When Welles did his fictional broadcast later, after the crisis had receded, he used this news bulletin technique to give things verisimilitude: he started the broadcast by faking a standard dance-music program, which kept getting interrupted by increasingly terrifying "on the scene reports" from New Jersey. Listeners who panicked, reacted not to content, but to format; they heard "We interrupt this program for an emergency bulletin," and "invasion," and immediately concluded that Hitler had invaded. The soap opera technique, transposed to the news, had worked on a vast and unexpected scale.

Little Annie and the "Wagnerian Dream" of TV

In 1939, one of the numbers of the quarterly Journal of Applied Psychology was handed over to Adorno and the Radio Project to publish some of their findings. Their conclusion was that Americans had, over the last twenty years, become "radio-minded," and that their listening had become so fragmented that repetition of format was the key to popularity. The play list determined the "hits"—a truth well known to organized crime, both then and now—and repetition could make any form of music or any performer, even a classical music performer, a "star." As long as a familiar form or context was retained, almost any content would become acceptable. "Not only are hit songs, stars, and soap operas cyclically recurrent and rigidly invariable types," said Adorno, summarizing this material a few years later, "but the specific content of the entertainment itself is derived from them and only appears to change. The details are interchangeable."

The crowning achievement of the Radio Project was "Little Annie," officially titled the Stanton-Lazersfeld Program Analyzer. Radio Project research had shown that all previous methods of preview polling were ineffectual. Up to that point, a preview audience listened to a show or watched a film, and then was asked general questions: did you like the show? what did you think of so-and-so's performance? The Radio Project realized that this method did not take into account the test audience's atomized perception of the subject, and demanded that they make a rational analysis of what was intended to be an irrational experience. So, the Project created a device in which each test audience member was supplied with a type of rheostat on which he could register the intensity of his likes or dislikes on a moment-to-moment basis. By comparing the individual graphs produced by the device, the operators could determine, not if the audience liked the whole show — which was irrelevant—but, which situations or characters produced a positive, if momentary, feeling state.

Little Annie transformed radio, film, and ultimately television programming. CBS still maintains program analyzer facilities in Hollywood and New York; it is said that results correlate 85% to ratings. Other networks and film studios have similar operations. This kind of analysis is responsible for the uncanny feeling you get when, seeing a new film or TV show, you think you have seen it all before. You have, many times. If a program analyzer indicates that, for instance, audiences were particularly titilated by a short scene in a World War II drama showing a certain type of actor kissing a certain type of actress, then that scene format will be worked into dozens of screenplays—transposed to the Middle Ages, to outer space, etc., etc.

The Radio Project also realized that television had the potential to intensify all of the effects that they had studied. TV technology had been around for some years, and had been exhibited at the 1936 World's Fair in New York, but the only person to attempt serious utilization of the medium had been Adolf Hitler. The Nazis broadcast events from the 1936 Olympic Games "live" to communal viewing rooms around Germany; they were trying to expand on their great success in using radio to Nazify all aspects of German culture. Further plans for German TV development were sidetracked by war preparations.

Adorno understood this potential perfectly, writing in 1944:

Television aims at the synthesis of radio and film, and is held up only because the interested parties have not yet reached agreement, but its consequences will be quite enormous and promise to intensify the impoverishment of aesthetic matter so drastically, that by tomorrow the thinly veiled identity of all industrial culture products can come triumphantly out in the open, derisively fulfilling the Wagnerian dream of the Gesamtkunstwerk—the fusion of all the arts in one work.

The obvious point is this: the profoundly irrational forms of modern entertainment—the stupid and eroticized content of most TV and films, the fact that your local Classical music radio station programs Stravinsky next to Mozart—don't have to be that way. They were designed to be that way. The design was so successful, that today, no one even questions the reasons or the origins.

III. Creating "Public Opinion": The "Authoritarian Personality" Bogeyman and the OSS

The efforts of the Radio Project conspirators to manipulate the population, spawned the modern pseudoscience of public opinion polling, in order to gain greater control over the methods they were developing.

Today, public opinion polls, like the television news, have been completely integrated into our society. A "scientific survey" of what people are said to think about an issue can be produced in less than twenty-four hours. Some campaigns for high political office are completely shaped by polls; in fact, many politicians try to create issues which are themselves meaningless, but which they know will look good in the polls, purely for the purpose of enhancing their image as "popular." Important policy decisions are made, even before the actual vote of the citizenry or the legislature, by poll results. Newspapers will occasionally write pious editorials calling on people to think for themselves, even as the newspaper's business agent sends a check to the local polling organization.

The idea of "public opinion" is not new, of course. Plato spoke against it in his Republic over two millenia ago; Alexis de Tocqueville wrote at length of its influence over America in the early nineteenth century. But, nobody thought to measure public opinion before the twentieth century, and nobody before the 1930's thought to use those measurements for decision-making.

It is useful to pause and reflect on the whole concept. The belief that public opinion can be a determinant of truth is philosophically insane. It precludes the idea of the rational individual mind. Every individual mind contains the divine spark of reason, and is thus capable of scientific discovery, and understanding the discoveries of others. The individual mind is one of the few things that cannot, therefore, be "averaged." Consider: at the moment of creative discovery, it is possible, if not probable, that the scientist making the discovery is the only person to hold that opinion about nature, whereas everyone else has a different opinion, or no opinion. One can only imagine what a "scientifically-conducted survey" on Kepler's model of the solar system would have been, shortly after he published the Harmony of the World: 2% for, 48% against, 50% no opinion.

These psychoanalytic survey techniques became standard, not only for the Frankfurt School, but also throughout American social science departments, particularly after the I.S.R. arrived in the United States. The methodology was the basis of the research piece for which the Frankfurt School is most well known, the "authoritarian personality" project. In 1942, I.S.R. director Max Horkheimer made contact with the American Jewish Committee, which asked him to set up a Department of Scientific Research within its organization. The American Jewish Committee also provided a large grant to study anti-Semitism in the American population. "Our aim," wrote Horkheimer in the introduction to the study, "is not merely to describe prejudice, but to explain it in order to help in its eradication.... Eradication means reeducation scientifically planned on the basis of understanding scientifically arrived at."

These psychoanalytic survey techniques became standard, not only for the Frankfurt School, but also throughout American social science departments, particularly after the I.S.R. arrived in the United States. The methodology was the basis of the research piece for which the Frankfurt School is most well known, the "authoritarian personality" project. In 1942, I.S.R. director Max Horkheimer made contact with the American Jewish Committee, which asked him to set up a Department of Scientific Research within its organization. The American Jewish Committee also provided a large grant to study anti-Semitism in the American population. "Our aim," wrote Horkheimer in the introduction to the study, "is not merely to describe prejudice, but to explain it in order to help in its eradication.... Eradication means reeducation scientifically planned on the basis of understanding scientifically arrived at."

Ultimately, five volumes were produced for this study over the course of the late 1940's; the most important was the last, The Authoritarian Personality, by Adorno, with the help of three Berkeley, California social psychologists.

Ultimately, five volumes were produced for this study over the course of the late 1940's; the most important was the last, The Authoritarian Personality, by Adorno, with the help of three Berkeley, California social psychologists.

In the 1930's Erich Fromm had devised a questionnaire to be used to analyze German workers pychoanalytically as "authoritarian," "revolutionary" or "ambivalent." The heart of Adorno's study was, once again, Fromm's psychoanalytic scale, but with the positive end changed from a "revolutionary personality," to a "democratic personality," in order to make things more palatable for a postwar audience.

Nine personality traits were tested and measured, including:

- conventionalism—rigid adherence to conventional, middle-class values

- authoritarian aggression—the tendency to be on the look-out for, to condemn, reject and punish, people who violate conventional values

- projectivity—the disposition to believethat wild and dangerous things go on in the world

- sex—exaggerated concern with sexual goings-on.

From these measurements were constructed several scales: the E Scale (ethnocentrism), the PEC Scale (poltical and economic conservatism), the A-S Scale (anti-Semitism), and the F Scale (fascism). Using Rensis Lickerts's methodology of weighting results, the authors were able to tease together an empirical definition of what Adorno called "a new anthropological type," the authoritarian personality. The legerdemain here, as in all psychoanalytic survey work, is the assumption of a Weberian "type." Once the type has been statistically determined, all behavior can be explained; if an anti-Semitic personality does not act in an anti-Semitic way, then he or she has an ulterior motive for the act, or is being discontinuous. The idea that a human mind is capable of transformation, is ignored.

The results of this very study can be interpreted in diametrically different ways. One could say that the study proved that the population of the U.S. was generally conservative, did not want to abandon a capitalist economy, believed in a strong family and that sexual promiscuity should be punished, thought that the postwar world was a dangerous place, and was still suspicious of Jews (and Blacks, Roman Catholics, Orientals, etc. — unfortunately true, but correctable in a social context of economic growth and cultural optimism). On the other hand, one could take the same results and prove that anti-Jewish pogroms and Nuremburg rallies were simmering just under the surface, waiting for a new Hitler to ignite them. Which of the two interpretations you accept is a political, not a scientific, decision. Horkheimer and Adorno firmly believed that all religions, Judaism included, were "the opiate of the masses." Their goal was not the protection of Jews from prejudice, but the creation of a definition of authoritarianism and anti-Semitism which could be exploited to force the "scientifically planned reeducation" of Americans and Europeans away from the principles of Judeo-Christian civilization, which the Frankfurt School despised. In their theoretical writings of this period, Horkheimer and Adorno pushed the thesis to its most paranoid: just as capitalism was inherently fascistic, the philosophy of Christianity itself is the source of anti-Semitism. As Horkheimer and Adorno jointly wrote in their 1947 "Elements of Anti-Semitism":

Christ, the spirit become flesh, is the deified sorcerer. Man's self-reflection in the absolute, the humanization of God by Christ, is the proton pseudos [original falsehood]. Progress beyond Judaism is coupled with the assumption that the man Jesus has become God. The reflective aspect of Christianity, the intellectualization of magic, is the root of evil.

At the same time, Horkheimer could write in a more-popularized article titled "Anti-Semitism: A Social Disease," that "at present, the only country where there does not seem to be any kind of anti-Semitism is Russia"[!].

This self-serving attempt to maximize paranoia was further aided by Hannah Arendt, who popularized the authoritarian personality research in her widely-read Origins of Totalitarianism. Arendt also added the famous rhetorical flourish about the "banality of evil" in her later Eichmann in Jerusalem: even a simple, shopkeeper-type like Eichmann can turn into a Nazi beast under the right psychological circumstances—every Gentile is suspect, psychoanalytically.

This self-serving attempt to maximize paranoia was further aided by Hannah Arendt, who popularized the authoritarian personality research in her widely-read Origins of Totalitarianism. Arendt also added the famous rhetorical flourish about the "banality of evil" in her later Eichmann in Jerusalem: even a simple, shopkeeper-type like Eichmann can turn into a Nazi beast under the right psychological circumstances—every Gentile is suspect, psychoanalytically.

It is Arendt's extreme version of the authoritarian personality thesis which is the operant philosophy of today's Cult Awareness Network (CAN), a group which works with the U.S. Justice Department and the Anti-Defamation League of the B'nai B'rith, among others. Using standard Frankfurt School method, CAN identifies political and religious groups which are its political enemies, then re-labels them as a "cult," in order to justify operations against them.

The Public Opinion Explosion

Despite its unprovable central thesis of "psychoanalytic types," the interpretive survey methodology of the Frankfurt School became dominant in the social sciences, and essentially remains so today. In fact, the adoption of these new, supposedly scientific techniques in the 1930's brought about an explosion in public-opinion survey use, much of it funded by Madison Avenue. The major pollsters of today—A.C. Neilsen, George Gallup, Elmo Roper—started in the mid-1930's, and began using the I.S.R. methods, especially given the success of the Stanton-Lazersfeld Program Analyzer. By 1936, polling activity had become sufficiently widespread to justify a trade association, the American Academy of Public Opinion Research at Princeton, headed by Lazersfeld; at the same time, the University of Chicago created the National Opinion Research Center. In 1940, the Office of Radio Research was turned into the Bureau of Applied Social Research, a division of Columbia University, with the indefatigable Lazersfeld as director.

After World War II, Lazersfeld especially pioneered the use of surveys to psychoanalyze American voting behavior, and by the 1952 Presidential election, Madison Avenue advertising agencies were firmly in control of Dwight Eisenhower's campaign, utilizing Lazersfeld's work. Nineteen fifty-two was also the first election under the influence of television, which, as Adorno had predicted eight years earlier, had grown to incredible influence in a very short time. Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborne — the fabled "BBD&O" ad agency—designed Ike's campaign appearances entirely for the TV cameras, and as carefully as Hitler's Nuremberg rallies; one-minute "spot" advertisements were pioneered to cater to the survey-determined needs of the voters.

This snowball has not stopped rolling since. The entire development of television and advertising in the 1950's and 1960's was pioneered by men and women who were trained in the Frankfurt School's techniques of mass alienation. Frank Stanton went directly from the Radio Project to become the single most-important leader of modern television. Stanton's chief rival in the formative period of TV was NBC's Sylvester "Pat" Weaver; after a Ph.D. in "listening behavior," Weaver worked with the Program Analyzer in the late 1930's, before becoming a Young & Rubicam vice-president, then NBC's director of programming, and ultimately the network's president. Stanton and Weaver's stories are typical.

Today, the men and women who run the networks, the ad agencies, and the polling organizations, even if they have never heard of Theodor Adorno, firmly believe in Adorno's theory that the media can, and should, turn all they touch into "football." Coverage of the 1991 Gulf War should make that clear.

The technique of mass media and advertising developed by the Frankfurt School now effectively controls American political campaigning. Campaigns are no longer based on political programs, but actually on alienation. Petty gripes and irrational fears are identified by psychoanalytic survey, to be transmogrified into "issues" to be catered to; the "Willy Horton" ads of the 1988 Presidential campaign, and the "flag-burning amendment," are but two recent examples. Issues that will determine the future of our civilization, are scrupulously reduced to photo opportunities and audio bites—like Ed Murrow's original 1930's radio reports—where the dramatic effect is maximized, and the idea content is zero.

Part of the influence of the authoritarian personality hoax in our own day also derives from the fact that, incredibly, the Frankfurt School and its theories were officially accepted by the U.S. government during World War II, and these Cominternists were responsible for determining who were America's wartime, and postwar, enemies. In 1942, the Office of Strategic Services, America's hastily-constructed espionage and covert operations unit, asked former Harvard president James Baxter to form a Research and Analysis (R&A) Branch under the group's Intelligence Division. By 1944, the R&A Branch had collected such a large and prestigeous group of emigré scholars that H. Stuart Hughes, then a young Ph.D., said that working for it was "a second graduate education" at government expense. The Central European Section was headed by historian Carl Schorske; under him, in the all-important Germany/Austria Section, was Franz Neumann, as section chief, with Herbert Marcuse, Paul Baran, and Otto Kirchheimer, all I.S.R. veterans. Leo Lowenthal headed the German-language section of the Office of War Information; Sophie Marcuse, Marcuse's wife, worked at the Office of Naval Intelligence. Also at the R&A Branch were: Siegfried Kracauer, Adorno's old Kant instructor, now a film theorist; Norman O. Brown, who would become famous in the 1960's by combining Marcuse's hedonism theory with Wilhelm Reich's orgone therapy to popularize "polymorphous perversity"; Barrington Moore, Jr., later a philosophy professor who would co-author a book with Marcuse; Gregory Bateson, the husband of anthropologist Margaret Mead (who wrote for the Frankfurt School's journal), and Arthur Schlesinger, the historian who joined the Kennedy Administration. Marcuse's first assignment was to head a team to identify both those who would be tried as war criminals after the war, and also those who were potential leaders of postwar Germany. In 1944, Marcuse, Neumann, and Kirchheimer wrote the Denazification Guide, which was later issued to officers of the U.S. Armed Forces occupying Germany, to help them identify and suppress pro-Nazi behaviors. After the armistice, the R&A Branch sent representatives to work as intelligence liaisons with the various occupying powers; Marcuse was assigned the U.S. Zone, Kirchheimer the French, and Barrington Moore the Soviet. In the summer of 1945, Neumann left to become chief of research for the Nuremburg Tribunal. Marcuse remained in and around U.S. intelligence into the early 1950's, rising to the chief of the Central European Branch of the State Department's Office of Intelligence Research, an office formally charged with "planning and implementing a program of positive-intelligence research ... to meet the intelligence requirements of the Central Intelligence Agency and other authorized agencies." During his tenure as a U.S. government official, Marcuse supported the division of Germany into East and West, noting that this would prevent an alliance between the newly liberated left-wing parties and the old, conservative industrial and business layers. In 1949, he produced a 532-page report, "The Potentials of World Communism" (declassified only in 1978), which suggested that the Marshall Plan economic stabilization of Europe would limit the recruitment potential of Western Europe's Communist Parties to acceptable levels, causing a period of hostile co-existence with the Soviet Union, marked by confrontation only in faraway places like Latin America and Indochina—in all, a surprisingly accurate forecast. Marcuse left the State Department with a Rockefeller Foundation grant to work with the various Soviet Studies departments which were set up at many of America's top universities after the war, largely by R&A Branch veterans.

Part of the influence of the authoritarian personality hoax in our own day also derives from the fact that, incredibly, the Frankfurt School and its theories were officially accepted by the U.S. government during World War II, and these Cominternists were responsible for determining who were America's wartime, and postwar, enemies. In 1942, the Office of Strategic Services, America's hastily-constructed espionage and covert operations unit, asked former Harvard president James Baxter to form a Research and Analysis (R&A) Branch under the group's Intelligence Division. By 1944, the R&A Branch had collected such a large and prestigeous group of emigré scholars that H. Stuart Hughes, then a young Ph.D., said that working for it was "a second graduate education" at government expense. The Central European Section was headed by historian Carl Schorske; under him, in the all-important Germany/Austria Section, was Franz Neumann, as section chief, with Herbert Marcuse, Paul Baran, and Otto Kirchheimer, all I.S.R. veterans. Leo Lowenthal headed the German-language section of the Office of War Information; Sophie Marcuse, Marcuse's wife, worked at the Office of Naval Intelligence. Also at the R&A Branch were: Siegfried Kracauer, Adorno's old Kant instructor, now a film theorist; Norman O. Brown, who would become famous in the 1960's by combining Marcuse's hedonism theory with Wilhelm Reich's orgone therapy to popularize "polymorphous perversity"; Barrington Moore, Jr., later a philosophy professor who would co-author a book with Marcuse; Gregory Bateson, the husband of anthropologist Margaret Mead (who wrote for the Frankfurt School's journal), and Arthur Schlesinger, the historian who joined the Kennedy Administration. Marcuse's first assignment was to head a team to identify both those who would be tried as war criminals after the war, and also those who were potential leaders of postwar Germany. In 1944, Marcuse, Neumann, and Kirchheimer wrote the Denazification Guide, which was later issued to officers of the U.S. Armed Forces occupying Germany, to help them identify and suppress pro-Nazi behaviors. After the armistice, the R&A Branch sent representatives to work as intelligence liaisons with the various occupying powers; Marcuse was assigned the U.S. Zone, Kirchheimer the French, and Barrington Moore the Soviet. In the summer of 1945, Neumann left to become chief of research for the Nuremburg Tribunal. Marcuse remained in and around U.S. intelligence into the early 1950's, rising to the chief of the Central European Branch of the State Department's Office of Intelligence Research, an office formally charged with "planning and implementing a program of positive-intelligence research ... to meet the intelligence requirements of the Central Intelligence Agency and other authorized agencies." During his tenure as a U.S. government official, Marcuse supported the division of Germany into East and West, noting that this would prevent an alliance between the newly liberated left-wing parties and the old, conservative industrial and business layers. In 1949, he produced a 532-page report, "The Potentials of World Communism" (declassified only in 1978), which suggested that the Marshall Plan economic stabilization of Europe would limit the recruitment potential of Western Europe's Communist Parties to acceptable levels, causing a period of hostile co-existence with the Soviet Union, marked by confrontation only in faraway places like Latin America and Indochina—in all, a surprisingly accurate forecast. Marcuse left the State Department with a Rockefeller Foundation grant to work with the various Soviet Studies departments which were set up at many of America's top universities after the war, largely by R&A Branch veterans.

At the same time, Max Horkheimer was doing even greater damage. As part of the denazification of Germany suggested by the R&A Branch, U.S. High Commissioner for Germany John J. McCloy, using personal discretionary funds, brought Horkheimer back to Germany to reform the German university system. In fact, McCloy asked President Truman and Congress to pass a bill granting Horkheimer, who had become a naturalized American, dual citizenship; thus, for a brief period, Horkheimer was the only person in the world to hold both German and U.S. citizenship. In Germany, Horkheimer began the spadework for the full-blown revival of the Frankfurt School in that nation in the late 1950's, including the training of a whole new generation of anti-Western civilization scholars like Hans-Georg Gadamer and Jürgen Habermas, who would have such destructive influence in 1960's Germany. In a period of American history when some individuals were being hounded into unemployment and suicide for the faintest aroma of leftism, Frankfurt School veterans—all with superb Comintern credentials — led what can only be called charmed lives. America had, to an incredible extent, handed the determination of who were the nation's enemies, over to the nation's own worst enemies.

At the same time, Max Horkheimer was doing even greater damage. As part of the denazification of Germany suggested by the R&A Branch, U.S. High Commissioner for Germany John J. McCloy, using personal discretionary funds, brought Horkheimer back to Germany to reform the German university system. In fact, McCloy asked President Truman and Congress to pass a bill granting Horkheimer, who had become a naturalized American, dual citizenship; thus, for a brief period, Horkheimer was the only person in the world to hold both German and U.S. citizenship. In Germany, Horkheimer began the spadework for the full-blown revival of the Frankfurt School in that nation in the late 1950's, including the training of a whole new generation of anti-Western civilization scholars like Hans-Georg Gadamer and Jürgen Habermas, who would have such destructive influence in 1960's Germany. In a period of American history when some individuals were being hounded into unemployment and suicide for the faintest aroma of leftism, Frankfurt School veterans—all with superb Comintern credentials — led what can only be called charmed lives. America had, to an incredible extent, handed the determination of who were the nation's enemies, over to the nation's own worst enemies.

IV. The Aristotelian Eros: Marcuse and the CIA's Drug Counterculture

In 1989, Hans-Georg Gadamer, a protégé of Martin Heidegger and the last of the original Frankfurt School generation, was asked to provide an appreciation of his own work for the German newspaper, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. He wrote,

One has to conceive of Aristotle's ethics as a true fulfillment of the Socratic challenge, which Plato had placed at the center of his dialogues on the Socratic question of the good.... Plato described the idea of the good ... as the ultimate and highest idea, which is supposedly the highest principle of being for the universe, the state, and the human soul. Against this Aristotle opposed a decisive critique, under the famous formula, "Plato is my friend, but the truth is my friend even more." He denied that one could consider the idea of the good as a universal principle of being, which is supposed to hold in the same way for theoretical knowledge as for practical knowledge and human activity.