Фридрих Ніцше як «засновник» консервативної революції

Out of intellectual phenomena and social currents that count Friedrich Nietzsche among their predecessors, Conservative Revolution (further CR. – OS) occupies a unique place as a guide for a comprehensive translation of his philosophical leitmotifs into distinct conceptions in the fields of philosophy of history, anthropology and philosophy of subject, political philosophy, including the civilizational analysis, ethnography and geopolitics, philosophy of culture, philosophy of religion and even philosophy of technology.

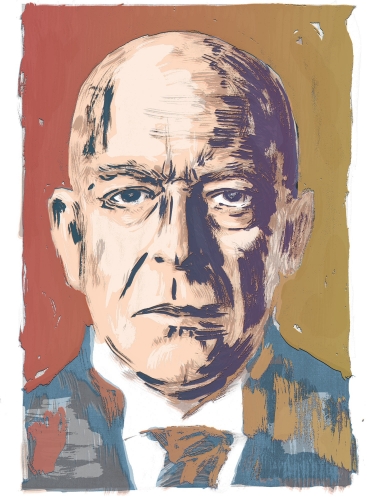

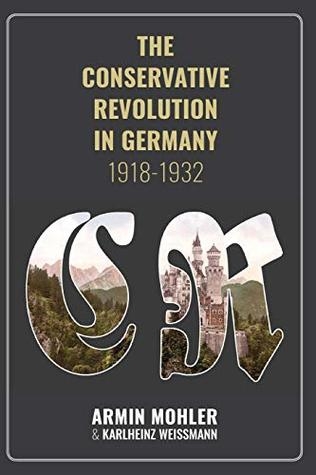

According to Swiss-German historian Armin Mohler, who introduced this formula in a prolific albeit debatable study “Conservative Revolution in Germany: 1918–1932” [80] to describe an intellectual milieu hostile to the “ideas of 1789,” CR, as a cultural and political current, has taken shape in the interwar Germany, but its conceptual relevance transcends these temporal and geographic boundaries. Although later metaphysical discussions of Nietzscheanism[1] within the current are lacking in his pioneer historiographic research (1950), the very number of critical monographs attempting to question the integrity of CR and simply deconstruct the term speaks in favor of its heuristic value[2] [81]. As of now, CR, with or without the quotation marks, gave birth to quite a rich tradition of academic investigation as a thought-provoking, interdisciplinary and even paradigm-shifting subject.

According to Swiss-German historian Armin Mohler, who introduced this formula in a prolific albeit debatable study “Conservative Revolution in Germany: 1918–1932” [80] to describe an intellectual milieu hostile to the “ideas of 1789,” CR, as a cultural and political current, has taken shape in the interwar Germany, but its conceptual relevance transcends these temporal and geographic boundaries. Although later metaphysical discussions of Nietzscheanism[1] within the current are lacking in his pioneer historiographic research (1950), the very number of critical monographs attempting to question the integrity of CR and simply deconstruct the term speaks in favor of its heuristic value[2] [81]. As of now, CR, with or without the quotation marks, gave birth to quite a rich tradition of academic investigation as a thought-provoking, interdisciplinary and even paradigm-shifting subject.

It has become a commonplace to argue that this movement’s political ambitions, regardless of palpable responsibility for the collapse of the Weimar republic, have come to end in 1933 and thus have never been fully implemented in practice. However, a descriptive value of Mohler’s monograph allowed researchers to consider the accomplished “CR” even such remote in time and space historical phenomena as the Restoration of Meiji in Japan, also regarded as the Japanese version of “modernization without westernization,” which started in 1868 [99]. Facing this broad historiographic request, one could paraphrase Voltaire by saying that even if there was no German CR, it should have been invented.

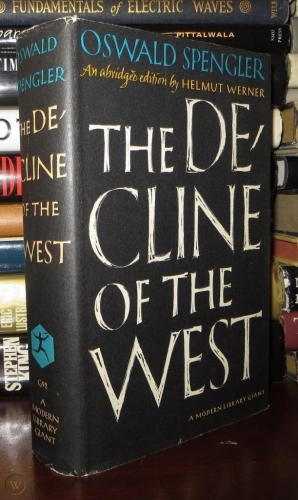

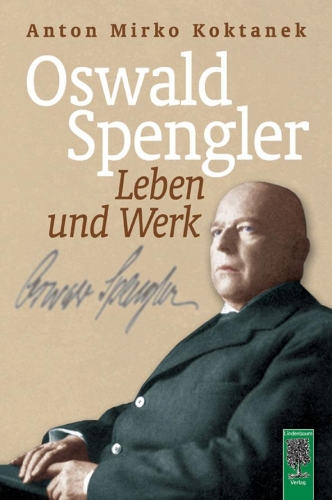

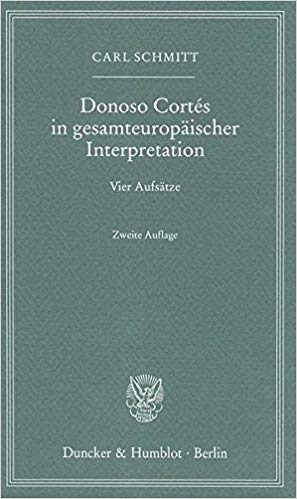

Yet, these conservative-revolutionary principles would have never been specified and applied to a wider scope of historical trends unless Friedrich Nietzsche, as an admitted “godfather” of the movement, had stated the ongoing decadence in the Western part of the world. His discussion of the European crisis in cultural, geopolitical, institutional, etc. terms corresponds with a variety of conceptual responses to this condition by key conservative-revolutionary thinkers of the 20th century (Oswald Spengler’s “decline of the West,” “Prussian Socialism” and “Caesarism,” Arthur Moeller van den Bruck’s “new conservatism / new socialism,” “young nations” and “the Third Empire,” Carl Schmitt’s geopolitics of large spaces as “pluriversum,” Ernst Jünger’s “heroic realism,” “new nationalism” and “the United States of Europe,” Werner Sombart’s “creative destruction” in economics, Gottfried Benn’s “Dionysian” expressionism and art “after nihilism,” etc.). However, they would indeed have fallen apart had it not been for a metaphysical foundation of European “illness” diagnosed by Nietzsche as the spread of the desert of nihilism[3].

Moreover, witnessing the upheaval brought by the First World War, theorists, researchers and “fellow travelers” of the conservative-revolutionary movement, above all, Ernst and Friedrich Georg Jünger, Armin Mohler and Martin Heidegger, offered the most exhaustive philosophical interpretation of Nietzscheanism as part of the discussion on a new or “the second beginning” of Western metaphysics, at least the prospects for overcoming nihilism, thus challenging a literal understanding of the “end-of-philosophy” thesis. In other words, this largely comparative, or rather genealogical study also brings out that the relation between “theoria” and “praxis” stemming from the modernity is not necessarily mediated by ideology.

That being said, far from explaining obscurum per obscurius (Nietzscheanism via CR and vice versa), the article seeks to examine metaphysical and practical conclusions drawn by the conservative-revolutionary movement from the pivotal Nietzsche’s concept of transvaluation of all values, thus suggesting a heuristic way out of the lasting “battle over Nietzsche” between the Left and the Right. A proof of Nietzsche’s visionary genius, narrow political appropriations of his name have almost cost him a place at the philosophic Olympus and should be firmly rejected. Besides, without exaggeration, Ernst Jünger’s and Martin Heidegger’s reception of Nietzscheanism, as well as their own polemic over it, is the groundbreaking milestone in Nietzsche-studies which cannot be skipped over in the given research.

More precisely, this interwar German movement, which has always been escaping strict definitions, owes its reputation of the “ideocratic,” “metapolitical,” “neither right-wing, nor left-wing” Third Way precisely to embracing Nietzscheanism as a means of Weberian “re-enchantment of the world” [63]. Indeed, in social sciences and humanities, it was no sooner than Nietzsche put forward the event of the “death of god” that ideological and, basically, purely modern perplexities of the Left and Right have become a low priority compared to transhistorical (epochal) interplay of modernism and antimodernism, broader, the progressive and regressive vector. The latter were partially grasped by derivative intuitions of reactionary modernism [38], organological supermodern [63, 109; 40], archeofuturism [10], etc. in reference to Nietzsche-inspired phenomenon of CR.

More precisely, this interwar German movement, which has always been escaping strict definitions, owes its reputation of the “ideocratic,” “metapolitical,” “neither right-wing, nor left-wing” Third Way precisely to embracing Nietzscheanism as a means of Weberian “re-enchantment of the world” [63]. Indeed, in social sciences and humanities, it was no sooner than Nietzsche put forward the event of the “death of god” that ideological and, basically, purely modern perplexities of the Left and Right have become a low priority compared to transhistorical (epochal) interplay of modernism and antimodernism, broader, the progressive and regressive vector. The latter were partially grasped by derivative intuitions of reactionary modernism [38], organological supermodern [63, 109; 40], archeofuturism [10], etc. in reference to Nietzsche-inspired phenomenon of CR.

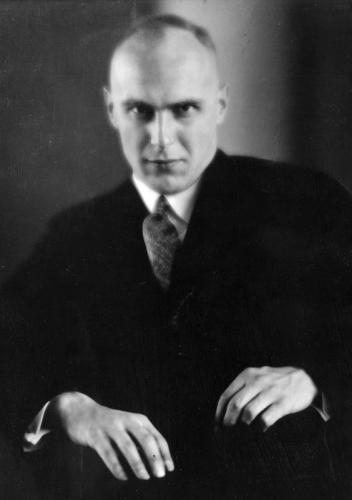

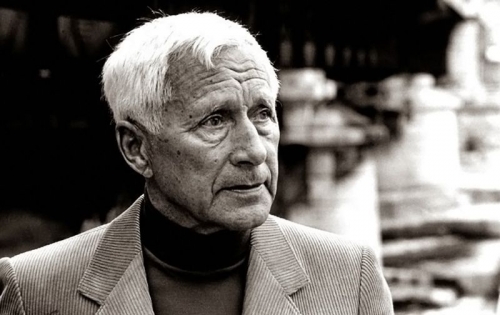

Fairly enough, the majority of conservative-revolutionary researches shedding light on the alternative of the classic triad (“premodern-modern-postmodern”) periodization are dedicated namely to Ernst Jünger’s work as a convinced follower of Nietzsche and, according to his longtime secretary Armin Mohler, the most representative theorist of CR. It is his creativity that is considered the brightest example of the alternative of the Enlightenment project of modernization and is widely known for its futuristic and even forecasting value [65]. Dramatic failed attempts by Mohler to bring Jünger back to politics and make him head the endeavors of a post-war German generation eloquently coincided with Jünger’s growing focus on the metaphysical revolution in the history of the West followed by the thematic polemic with Heidegger in the 50-s.

Despite a misleading title, which was not favored by futuristic Jünger, such a super- (not to be confused with post-) modern alignment is the main reason why it is hard to classify CR, which otherwise shows all signs of a distinct and consistent theoretic current, as the classic fourth ideology crowning liberalism, socialism and conservatism. Likewise, it shows the absurdity of any strict ideological attribution of Nietzscheanism as the intellectual legacy ahead of its time, the conviction repeatedly expressed by Nietzsche himself.

For the past over half a century since the classic study by Mohler was out (1950), little advance has been made in this field. More precisely, there is enough literature dealing with the complexity of Nietzsche’s social ideas and their place in his entire body of work; the point is that Nietzsche-debates have long reached such a level of intensity that the conflict of interpretations unfolds between recognizable humanitarian paradigms, schools and traditions rather than breaking readings of his attitude to certain “-isms.” In other words, today, there is a rivalry between the basic insights into what Nietzscheanism is all about: emancipation or the will to power, decadence or vitalism, tradition or revolution, etc.

Ukrainian historiographers of the subject are lucky to have at their disposal 1000-page research of Nietzsche’s corpus and biography [110] by leading Ukrainian specialist on Nietzscheanism Taras Lyuty, which offers an exhaustive overview of Nietzsche’s reception in Germany, including Jünger’s and Heidegger’s contribution, France, Great Britain, United States, Italy, Spain, Russia, Poland, the Eastern world and Ukraine. At the same time, multifaceted yet integral elaboration of Nietzsche’s thought within the conservative-revolutionary current deserves to be a separate challenging chapter of modern Nietzscheana.

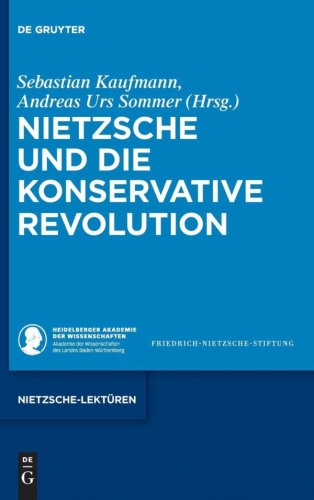

In this light, it is especially remarkable that in 2016 in Germany took place the annual Oßmannstedter Nietzsche Colloquium entitled “Nietzsche and the Conservative Revolution,” which offers a searched balanced account of Nietzscheanism beyond extremes of ideological reductionism and mere aestheticism. Held under the aegis of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar and the Nietzsche Commentary of Heidelberg Academy of Sciences headed by Prof. Andreas Urs Sommer, it has become a wide interdisciplinary event which highlighted the Nietzsche-exegesis by such diverse conservative-revolutionary authors and related figures as Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Ernst Niekisch, Armin Mohler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and others. Nietzsche and Dostoevsky, “radical aristocratism” of Rainer Maria Rilke, and Nietzsche’s merit in the very introduction of the term “CR” were also addressed at this surprise colloquium. Its results were published in an over 600-page collection of conference materials [89].

Previously, the founding Oßmannstedter Nietzsche Colloquium (2014) has already undertaken an uneasy study on the thematic complex “Nietzsche-Politics-Power,” which has prepared the audience for the lesser-known comparative background of CR. Back then, the ambiguity of Nietzsche’s exposure of contradictions tearing a bourgeois society apart was problematized as the issue begging for the further exploration. The trajectory of thought outlined by the event’s organizers was quite similar to the idea behind the given research: from the fact that Nietzsche’s works contained many apparently reactionary elements to their inherently transhistorical and, nolens volens, metaideological nature, which inevitably leads to the phenomenon of CR and the quest for a new metaphysics. Thus, the third Oßmannstedter Nietzsche Colloquium finally allowed positive yet unapologetic reconstruction of possible outcomes of his “criticism of modernity” as stated in “Ecce Homo”: “This book (1886) is in all essentials a critique of modernity, modern science, modern art, even modern politics, along with indications of an opposite type that is anything but modern, a noble, yea-saying type” [85, 80].

Indeed, so far, attempts to convert Nietzsche into politics have been mostly associated with the Nietzsche-Archiv’s destiny in the service of National Socialist ideology thanks to its ardent supporter Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, philosopher’s sister. However, the same destiny largely befell the work of conservative-revolutionary Nietzscheans, the brightest example being “The Third Empire”[4] by Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, the author of “Tschandala Nietzsche,” “Führende Deutsche” and other Nietzsche-themed writings.

Indeed, so far, attempts to convert Nietzsche into politics have been mostly associated with the Nietzsche-Archiv’s destiny in the service of National Socialist ideology thanks to its ardent supporter Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, philosopher’s sister. However, the same destiny largely befell the work of conservative-revolutionary Nietzscheans, the brightest example being “The Third Empire”[4] by Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, the author of “Tschandala Nietzsche,” “Führende Deutsche” and other Nietzsche-themed writings.

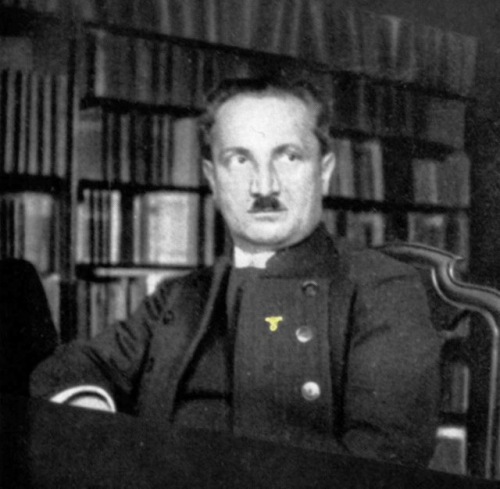

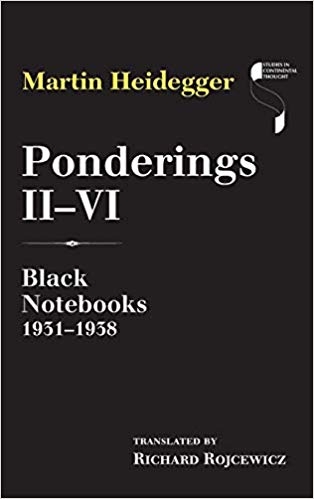

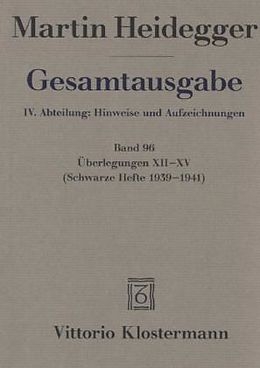

Three overviews of Nietzsche’s legacy of that period deemed the most important by Karl Jaspers were the readings by Ludwig Klages, Alfred Baeumler and Ernst Bertram [49, 467]. Oddly enough, Heidegger, who, especially in his late period, exposed Nietzsche’s biologism [28, 168–170], in the 30-s polemicized with the biological interpretation of Nietzscheanism targeting both Klages and Spengler in lectures [e.g. 24, 103–116]. To be fair, the late Heidegger’s understanding of Nietzsche, which may be already traced in “Contributions to Philosophy” (1936–38) [20, 218–219], derived Nietzsche’s biologism from metaphysics of subjectivity, more precisely, subjectivity of the “will to power,” so it was different from vitalist and organicist interpretations by Klages and Spengler. Anyway, in this, he solidarized with Baeumler [29, 297], professor of philosophy and an ideologue of National Socialism. In contrast with his colleague Ernst Krieck, Baeumler did not reject Nietzsche as a philosopher who opposed “socialism, nationalism and racial thinking” [66, 31], so only National Socialist readings of Nietzsche could overlap with the conservative-revolutionary ones, not vice versa. Likewise, Heidegger denied Nietzsche’s imperialism (“Neither does the “grand style” want an “aesthetic culture,” nor does the “grand politics” want the exploitative power politics of imperialism” [31, 158]) and provided the deepest philosophical account of Nietzscheanism in the two-volume “Nietzsche” work.

Later, thanks to the most influential left-wing readings of Nietzsche, in particular, the second issue of Georges Bataille’s review “Acéphale” (1937) eloquently entitled “Nietzsche and the Fascists: A Reparation” [2], the “blond beast’s” herald was fully rehabilitated by French postmodernist philosophers and, broadly, New Leftist thinkers like Peter Sloterdijk who incorporated Nietzsche’s legacy into the sociocultural analysis and critique of ideology following in the footsteps of Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno. But the price for this insightful yet, by and large, another arbitrary and incomplete reception of Nietzsche’s ideas was their “methodological” reduction to Paul Ricoeur’s “philosophy of suspicion” and genealogical inquiry in the vein of Michel Foucault.

As a result, such inconvenient albeit pivotal for Nietzsche concepts as great politics, a new aristocracy (“a ruling caste”) of a united Europe, anti-egalitarianism (“a pathos of distance”) and a contempt for a “democratic mediocrity” along with a reverence for free thinking, etc., which were objectively highlighted by Jaspers in his introduction to “Corpus Nietzscheanum,” were passed over in silence. Alluding to Bataille, new reparations to Nietzsche are needed.

For it is enough to look through editions like “The Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche” or “Historical Dictionary of Nietzscheanism,” to realize that, initially, reactionary elements in Nietzsche’s thought were too obvious for the succeeding generation not to be astonished by his enthusiastic readings “from the Left.” In contrast with an impressive marriage of socialism with Nietzscheanism and Social Darwinism in Jack London’s novels and short stories, Georg Lukács, one of the masterminds behind “Western Marxism,” after a short period of fascination, confidently labeled Nietzsche as “as founder of irrationalism in the imperialist period” in the eponymous chapter of his work, “The Destruction of Reason” (1952), as well as portrayed him [70, 37–94, 309–399], Arthur Schopenhauer, Wilhelm Dilthey, Oswald Spengler and others as precursors of Adolf Hitler.

On the other hand, according to Ernst Troeltsch, German philosopher of history, theologian and, along with Thomas Mann and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, one of the first promoters of the term “CR” [107, 454], only after the First World War, through “war experience,” Nietzsche’s thought was purified of its “sickly and exaggerated elements and thus had set ‘new aims’” [106, 75, quoted after 64, 48] for the German people. Jürgen Habermas confirms that Nietzsche reached the peak of popularity in Germany’s interwar period, when “the ideas of 1914” were confronted with “the ideas of 1789,” noting that “thinkers as various as Oswald Spengler, Carl Schmitt, Gottfried Benn, Ernst Jünger, Martin Heidegger, and even Arnold Gehlen show affinity with this background” [18, 209].

On the other hand, according to Ernst Troeltsch, German philosopher of history, theologian and, along with Thomas Mann and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, one of the first promoters of the term “CR” [107, 454], only after the First World War, through “war experience,” Nietzsche’s thought was purified of its “sickly and exaggerated elements and thus had set ‘new aims’” [106, 75, quoted after 64, 48] for the German people. Jürgen Habermas confirms that Nietzsche reached the peak of popularity in Germany’s interwar period, when “the ideas of 1914” were confronted with “the ideas of 1789,” noting that “thinkers as various as Oswald Spengler, Carl Schmitt, Gottfried Benn, Ernst Jünger, Martin Heidegger, and even Arnold Gehlen show affinity with this background” [18, 209].

In other words, those standing at the origins of CR partly shared discontent with Nietzsche’s “irrationalism” by a conventional line “Lukács – Frankfurt School/ Habermas.” As T. Lyuty’s research shows, Nietzsche’s reception (not only in Germany and France but also Fascist Italy and Falangist Spain) was quite complicated, getting more controversial in the aftermath of both world wars and including many instances of both leftist and rightist apologies of Nietzscheanism.

Not incidentally, the national-revolutionary wing of CR, the most left-leaning among its currents, offered the most inclusive readings of Nietzsche. Just to name a few, Jünger’s mentor Hugo Fischer, who was close to the circle of sociologist Hans Freyer, an author of programmatic “Revolution from the Right” (1931), wrote both “Lenin: Machiavelli of the East” (1933) and “Nietzsche the Apostate” (1931) [12] in which he argued that Nietzsche was a more profound diagnostician of alienation than Karl Marx [1, 194–195], and Friedrich Hielscher, an architect of pagan “Das Reich” (1931), who described Nietzsche as the “protector of the past, as crusher of the present, as transformer of the future” [41, 200, quoted after 1, 153]. National Bolshevik Ernst Niekisch admired Nietzsche in his early texts, although after 1945, in fact, he has become a founder of Marxist criticism of Nietzsche in the GDR [92].

Likewise, the French New Right in the person of their “godfather,” Italian thinker Giorgio Locchi, who polemicized with Lukács’ blaming Hitlerism on Nietzsche, agreed with postmodern counterparts like G. Bataille, Maurice Blanchot, Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard, Jacques Derrida, Jean Baudrillard and others in their positive assessment of Nietzsche’s prevailing “revisionism” of modern. It is precisely therein that we encounter contemporary attempts to interpret Nietzscheanism, at a glance, “from the Right” by converting it into a new humanitarian school, which would have hardly gained momentum without New Leftist praise of Nietzsche’s “centauric” nature and a Dionysian revolt against the modernity in the vein of Sloterdijk’s “Thinker On Stage: Nietzsche’s Materialism” (1986) [99]. Locchi, who gave an impetus to thinkers as varied as Dominique Venner (i.a., an author of “Ernst Jünger: Another European Destiny”), Robert Steuckers, Pierre Vial, Pierre Krebs, Alain de Benoist, Guillaume Faye and others, directly linked Nietzscheanism to German CR and was the first to define Nietzsche’s view of history as “spherical.”

Key works by Locchi for our study, “The Meaning of History” (1971), “Wagner, Nietzsche and the Myth of Suprahumanism” (1982), “Martin Heidegger and Conservative Revolution” (1988), also published in response to “Heidegger’s case,” etc., reveal a threefold structure of history “unlocked” by initiators of the discontinuity with the tradition of preceding two thousand years [13, 211] and founders of the suprahumanist myth: Richard Wagner, above all, as an author of “The Ring of the Nibelung” and Friedrich Nietzsche reconciled with him and portrayed as his disciple. Having paralleled Wagner’s “aristocratic socialism” with CR, Locchi criticizes not only Lukács but also Adorno’s take on Wagner along with the entire Frankfurt School. According to him, suprahumanism, inspired by Johann Fichte’s discovery of Germania[5], revolts against the “egalitarian” Judeo-Christian worldview and, as opposed to a preventive function of critical theory, carries out a creative mission [67].

Key works by Locchi for our study, “The Meaning of History” (1971), “Wagner, Nietzsche and the Myth of Suprahumanism” (1982), “Martin Heidegger and Conservative Revolution” (1988), also published in response to “Heidegger’s case,” etc., reveal a threefold structure of history “unlocked” by initiators of the discontinuity with the tradition of preceding two thousand years [13, 211] and founders of the suprahumanist myth: Richard Wagner, above all, as an author of “The Ring of the Nibelung” and Friedrich Nietzsche reconciled with him and portrayed as his disciple. Having paralleled Wagner’s “aristocratic socialism” with CR, Locchi criticizes not only Lukács but also Adorno’s take on Wagner along with the entire Frankfurt School. According to him, suprahumanism, inspired by Johann Fichte’s discovery of Germania[5], revolts against the “egalitarian” Judeo-Christian worldview and, as opposed to a preventive function of critical theory, carries out a creative mission [67].

In spite of Heidegger’s dismissal of Nietzsche’s rhetoric of values as a pinnacle of modern metaphysics of subjectivity [26, 101–102; 30, 209–267; 28, 83–94], the axiological, not cosmological understanding of the eternal recurrence by Locchi and his disciples[6] is influenced by Heidegger’s criticism of metaphysics, anthropological thinking and humanism, as well as derivative conceptions of temporality and history [21]. As a result, cyclic and especially linear conceptions of history are rejected by these followers of Nietzsche as ill-suited for the ways of a free-willed human being famously defined by Heidegger as transcendence [21, 351]. The axiological interpretation of the eternal recurrence implies that culture’s underlying values are being reaffirmed over the course of time. However, innocence of life’s becoming, within the conception, means that the past (as a reservoir of archetypal patterns) and the future (as the potentiality of conditions to re-enact them), basically, are interrelated functions of the polycentric present as a playground for historical dynamic in any possible direction [see in more detail: 90, 117–126].

For instance, Guillaume Faye, whose theory of archeofuturism as a “dynamic worldview” is largely inspired by Nietzsche, Spengler and Jünger, argued that Nietzsche’s legacy should be firmly placed on the side of the Right, or rather “revolutionary Right” in the sense discussed above, especially his vision of the united Europe [17]. To mark the difference between the “old” and “new” Right, Faye famously contrasted Nietzscheanism with the strictly anti-modern school of integral traditionalism (“For some Guénon, and for others Nietzsche” [10, 174]) implying, above all, an ability to embrace the very epitome and the vehicle of modernity – technology.

To disclose this changing worldview, Faye complemented the “deconstructive” pole of Nietzscheanism, which is usually explored by left-leaning humanitarians, with an affirmative idea of the eternal recurrence, as follows: “Needless to say, Archeofuturism is based on the Nietzschean idea of Umwertung – the radical overthrowing of the modern values – and on a spherical view of history” [10, 74]. He emphasized that the eternal recurrence concerns “the identical” rather than “the same.” Different historical forms and institutions undergo a metamorphosis, yet their function remains unchanged: for instance, a nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine as a modification of an Athenian trireme [10, 75][7].

Carefully studied by Locchi, Armin Mohler did not consider Nietzsche just one of the conservative-revolutionary “church fathers” like Martin Heidegger or Stefan George [80, 69–70]. According to Mohler, precisely Nietzsche’s philosophy, also far beyond Germany [80, 87], shaped CR as the revolt against a linear conception of history, albeit not incompatible with the latter’s elements, and the very logic of progressivism. Quite remarkably, Mohler’s thesis on CR (1949) was supervised by Karl Jaspers, another Nietzsche scholar famous in his own right.

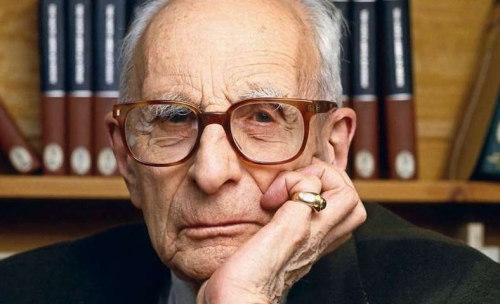

It is Heidegger’s disciple Karl Löwith (“Nietzsche’s Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence” and “From Hegel to Nietzsche: The Revolution in 19th Century Thought”)[8] who is credited by Mohler for one of the earliest insights (1935 and 1941, respectively) into the essence of Nietzscheanism as the self-overcoming of nihilism springing from the “death of god” through the will to the eternal recurrence of the same. Although Löwith detected a contradiction between the anthropological (“self-eternalization”) and cosmic (natural) eternal recurrence which includes and cancels the former [68, 60], he viewed Nietzscheanism as the quest to “renew, in the end, the ancient view of the world on the peak of anti-Christian modernity” [68, 74].

It is Heidegger’s disciple Karl Löwith (“Nietzsche’s Philosophy of the Eternal Recurrence” and “From Hegel to Nietzsche: The Revolution in 19th Century Thought”)[8] who is credited by Mohler for one of the earliest insights (1935 and 1941, respectively) into the essence of Nietzscheanism as the self-overcoming of nihilism springing from the “death of god” through the will to the eternal recurrence of the same. Although Löwith detected a contradiction between the anthropological (“self-eternalization”) and cosmic (natural) eternal recurrence which includes and cancels the former [68, 60], he viewed Nietzscheanism as the quest to “renew, in the end, the ancient view of the world on the peak of anti-Christian modernity” [68, 74].

Referring to the often-quoted Löwith’s sentence about the oscillation of the German spirit of the 19th century between the two endpoints in the persons of Hegel and Nietzsche, with lesser centers of gravity like Marx, Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky, Mohler emphatically contrasts Nietzsche with Hegel as the last great representative of the linear thought [80, 88]. Since the rebirth anticipated by conservative revolutionaries is possible only within the cyclic or mythological time enabling the access to eternity, Mohler praises Löwith’s work as the brightest philosophical-historical account of the “Interregnum,” the interim between the decline of the old order and the emergence of the new [80, 88].

Thus, temporality of the state of nihilism is clearly encrypted in Nietzsche’s allegories of the turning point in the course of the transvaluation of all values, the Great Noon in particular. The promise of the Interregnum’s end surmounted by a Superman echoes the passage from “To Genealogy of Morals,” which itself is a commentary to “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”: “… this bell stroke of noon and of the great decision that liberates the will again and restores its goal to the earth and his hope to man; this Antichrist and anti-nihilist; this victor over God and nothingness – he must come one day” [see 68, 56].

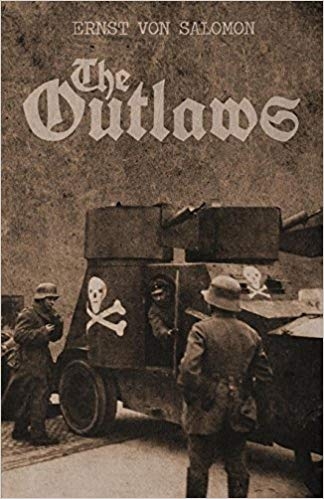

Having combined an etymological interpretation of revolution (from Latin “re-volutio”) as “rotation,” “spinning around,” “volution” with Moeller van den Bruck’s “new conservatism” as the restoration of eternal principles rather than the return to the past, Mohler made Nietzsche’s idea of eternal recurrence (meaning to the Origin) the common denominator for five different trends of CR, from Young Conservatives to National Revolutionaries (as the most influential). All of them had practical manifestation, and some of them were revolutionary also in quite a literal sense, expectedly laying stress on the “active-nihilistic” phase of the transvaluation of all values.

To recall, as follows from the notes to “The Will to Power,” posthumously complied and published Nietzsche’s magnum opus (at least for Heidegger), in which constituents of this metaphysical dynamics were for the first time revealed, so-called active nihilism is to be distinguished from its passive counterpart. Passive nihilism is a sign of the spirit’s fatigue, whereas active nihilism, quite the reverse, indicates surpassing of outworn ideals, is transitory and paves the path towards new values. This key fragment is the same both in the critical edition of Nietzsche’s Collected Works by Colli and Montinari and in the 1901 compilation [87, 350–351; 84,157–158].

Yet Old Gunpowder-Head, as Jünger used to call Nietzsche [51], provided conservative-revolutionary luminaries like him not only with recipes for social change. For historians of philosophy, connections between Nietzsche’s legacy and CR (which is the subject matter of the study) are of a special interest given that the famous “turn” of Heidegger towards a conservative criticism of technology and final abandonment of transcendentalism and voluntarism was triggered namely by his familiarization with Jünger’s conservative-revolutionary classic: “Total Mobilization” (1930) and “The Worker. Domination and Gestalt” (1932) [11, 718].

Yet Old Gunpowder-Head, as Jünger used to call Nietzsche [51], provided conservative-revolutionary luminaries like him not only with recipes for social change. For historians of philosophy, connections between Nietzsche’s legacy and CR (which is the subject matter of the study) are of a special interest given that the famous “turn” of Heidegger towards a conservative criticism of technology and final abandonment of transcendentalism and voluntarism was triggered namely by his familiarization with Jünger’s conservative-revolutionary classic: “Total Mobilization” (1930) and “The Worker. Domination and Gestalt” (1932) [11, 718].

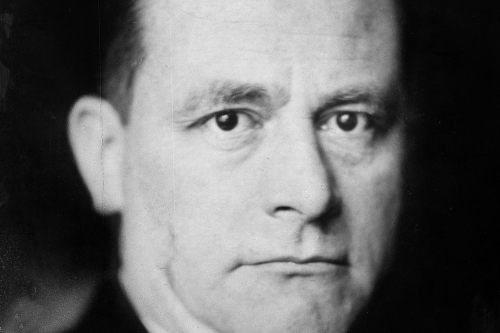

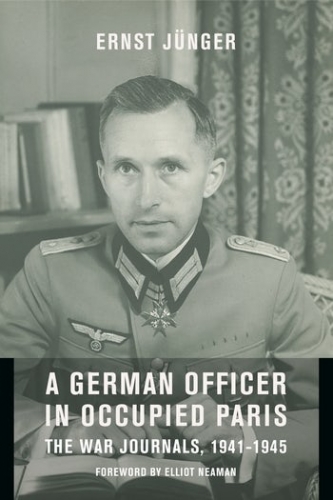

As believed by Heidegger, Jünger was the last Nietzschean and even “the only real follower of Nietzsche” [36, 227] whose early philosophy was the culminating point of Western metaphysics. Heidegger arrived at this conclusion within his two seminars on Jünger’s Worker right after it was out and during the winter semester at Freiburg University in 1939–1940. His extensive observations, as well as notes on other Jünger’s texts comprise the entire 90th volume of Heidegger’s Collected Works, “On Ernst Jünger,” which was revealed to the public in 2004 [36]. English translation of its crucial fragments may be found in “The Heidegger Reader” edited by Günter Figal [33, 189–206]. In one of them, Heidegger addresses Nietzsche’s metaphysics in relation to Western history after the First World War and claims that “only Ernst Jünger has grasped something essential there” [33, 192], i.a. contrasting his insight with “superficial” Spengler’s reading and mere cooption of certain Nietzsche’s ideas by Gabriele D’Annunzio and Benito Mussolini.

In the 1945 reflection upon his 1933 rectorial address, Heidegger recalls that Nietzsche’s words “God is dead” [25, 111] were mentioned there precisely in the light of predicted by Jünger emergence of a planetary state as a pinnacle of the modern will to power encompassing everything regardless of “whether it is called communism, or fascism, or world democracy” [22, 375–376]. In the 1933 speech entitled “The German Student as the Worker” [23, 205–206], he for the first time publically referred to Jünger and highly estimated his 1932 opus magnum. Yet Heidegger was scared of this tendency and wanted to avert it.

The late Jünger, in Heidegger’s opinion, still applied the language of old metaphysics (of subjectivity) to describe the advent of the new. Jünger’s essay “Over the Line” (1950) was published in a collection of articles dedicated to Heidegger’s 60th birthday anniversary and edited by Hans-Georg Gadamer [58; 57]. Likewise, Heidegger’s reply “On the Line” (1955) appeared in a jubilee edition in honor of Jünger turning 60 [34], and its extended version entered Heidegger’s Collected Works under the title “To the Question of Being” [37]. Their intense correspondence lasted till Heidegger’s death in 1976 [9].

In this respect, Heidegger’s early interpretation of Nietzscheanism as a search for a unifying force that is akin to the purpose of art in the age of Romanticism and thus is capable of bridging the gaps between disintegrated fields of modernity [19, 97–99] was much closer to the views on Nietzsche’s “bequest” held by Jünger brothers and Mohler. Indeed, in “The Will to Power as Art,” the lecture course on Nietzsche delivered at the University of Freiburg-im-Breisgau in 1936–37, Heidegger echoed Nietzsche’s assessment of art as “the anti-Christian, anti-Buddhist, anti-nihilist par excellence” [87, 521] by defining it as the “distinctive countermovement to nihilism” led by the “artist-philosopher” [31, 69–76].

Nietzsche as the philosopher who, in Habermas’ words, “entrusted the overcoming of nihilism to the aesthetically revived Dionysian myth” [19, 99] was explored in-depth by Friedrich Georg Jünger. In his eponymous book “Nietzsche” (1949) [60], as well as famous trilogy “Greek myths” (1947) comprised of “The Greek Gods,” “The Titans” and “The Heroes” [59], he paid a special attention to Pan as an epitome of the wild and Dionysus as a redeemer from the misery of time. Both motifs, as well as F. G. Jünger’s book “The Perfection of Technology” (written in 1939 and translated to English as “The Failure of Technology: Perfection Without Purpose” [61]), intersect with the late Heidegger’s criticism of instrumental rationality as “machination,” yet this time he considered Nietzsche’s philosophy the endpoint of Western metaphysics rather than the salvation [see 112].

Nietzsche as the philosopher who, in Habermas’ words, “entrusted the overcoming of nihilism to the aesthetically revived Dionysian myth” [19, 99] was explored in-depth by Friedrich Georg Jünger. In his eponymous book “Nietzsche” (1949) [60], as well as famous trilogy “Greek myths” (1947) comprised of “The Greek Gods,” “The Titans” and “The Heroes” [59], he paid a special attention to Pan as an epitome of the wild and Dionysus as a redeemer from the misery of time. Both motifs, as well as F. G. Jünger’s book “The Perfection of Technology” (written in 1939 and translated to English as “The Failure of Technology: Perfection Without Purpose” [61]), intersect with the late Heidegger’s criticism of instrumental rationality as “machination,” yet this time he considered Nietzsche’s philosophy the endpoint of Western metaphysics rather than the salvation [see 112].

At any rate, the spiritual-historical diagnosis of the epoch set by Nietzsche determined both Ernst Jünger’s metaphors of a great metaphysical transition (“the magical zero point [of values],” “Interregnum,” “the line,” “the wall of time,” “the return of the gods,” “approaching,” “whitening” understood not “as a nihilistic act, but rather as a counter-offensive” [56, 9] and subsequent “spiritualization,” etc.) and the middle Martin Heidegger’s conception of beyng-historical thinking “from within” the fate of Being (currently, forgetfulness). In other words, and it coincides with the scope of the article, Nietzscheanism fully underlies metaphysical teleology of CR (from subject-centric Prometheism to “summoning the gods”), which is indeed most pronounced in Ernst Jünger’s work.

In a positive sense, Mohler would fully agree with Heidegger’s opinion on Jünger’s legacy as the fullest explication of Nietzsche’s metaphysics and, in particular, the concept of the Superman[9] as a nihilist and at the same time a legislator of new values. For that purpose, he singled out three kinds of nihilism: the Western (French) one born out of satiety and weariness, just like passive nihilism described by Nietzsche, the Eastern (Russian) born out of life’s plentitude and the “spatial” rejection of any boundaries, and the German striving for its own exuberance just like many French are fond of German “barbarians” [80, 94]. However, Mohler interprets the German nihilism as conscious and volitional: as opposed to other types, it is especially dangerous as the both destructive and creative force capable of assuming new forms. Objectively highlighting the variety of conservative-revolutionary currents and manifestations, Mohler, when it comes to a metaphysical core of the subject, leaves no doubt that it boils down to Nietzscheanism as the German or active nihilism exemplified in Ernst Jünger’s work.

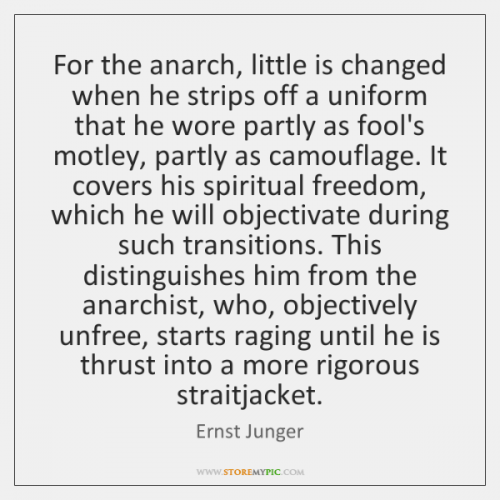

Mohler considers the gospel of this creative nihilism the first edition of “The Adventurous Heart” (1929) in which Jünger introduces a focal concept of the “magical zero point,” clearly referring to Nietzsche’s motif of the transvaluation of all values, towards which, in the interwar period, had been marching through the world on fire the “salamanders” like him. Mohler also draws attention to another representative concept invented by the German veteran and writer: the paradoxical combination of “Prussian anarchist” who rejects all existing orders, but only out of reverence for something greater [80, 96]. As Jünger himself explains, this “Prussian” rebellion needs explosives to free the living space for a new hierarchy [54, 66]. Later, it will evolve into his model of the right-wing anarchist – the Anarch[10].

Finally, in the most frequently quoted excerpt from “The Adventurous Heart,” as if Nietzschean prophecy of the “twilight of the idols” has come true, Jünger comments on a sinister reputation gained at that time by his generation. To wit, they were said to have been capable of destroying the temples. Far from denying it, Jünger, in fact, objected that such a sentence simply bore no significance in the futile epoch producing nothing but museums [53, 112].

Finally, in the most frequently quoted excerpt from “The Adventurous Heart,” as if Nietzschean prophecy of the “twilight of the idols” has come true, Jünger comments on a sinister reputation gained at that time by his generation. To wit, they were said to have been capable of destroying the temples. Far from denying it, Jünger, in fact, objected that such a sentence simply bore no significance in the futile epoch producing nothing but museums [53, 112].

Indeed, as Klemens von Klemperer observed, it was Nietzsche who, “in his paradoxical position between conservatism and nihilism, between conserving and destroying” [64, 39], gave birth to the well-known “dilemma of conservatism” that has to counter the extremities of Enlightenment by its own means [16]. Thus it comes as no surprise that the early Thomas Mann (1921) considered Nietzsche “nothing but Conservative Revolution” [75, 598] meaning the synthesis of “enlightenment and faith, freedom and bonds, spirit and flesh, ‘God’ and the ‘world’” [75, 597–598]. In this context, Mann referred to Henrik Ibsen’s search for “the third kingdom,” a Hegelian synthesis of the Pagan kingdom of man and flesh and the Christian kingdom of God and spirit [75, 597], for the first time problematized in Ibsen’s play “Emperor and Galilean” (1873) about Julian the Apostate. It brings the continuity of Nietzscheanism and CR to a whole new level, though in the introduction to the émigré journal “Measure and Value” (1937) Mann underlined the metapolitical meaning of this aware of tradition yet future-oriented blend of aristocratism and revolution [74, 801].

A new / secret kingdom and elite carrying this ideal in the vein of Nietzsche’s “On the Future of our Educational Institutions,” two basic mythologemes of the founding Young-Conservative current of CR, were introduced by Stefan George’s Circle and poetry, especially collections “The Star of the Covenant” (1914) and “The New Reich” (The Kingdom Come) (1928) [14, 15, also see Kantorowicz (62)]. In turn, they were inspired by an allegiance to “Secret Germany” found, above all, in Friedrich Hölderlin’s hymns, writings by Friedrich Schiller, Heinrich Heine, Paul de Lagarde, Julius Langbehn, as well as the legend of sleeping “mountain king” Friedrich I Barbarossa [43, 30–41].

Nietzscheanism as “radical aristocratism,” the formula first suggested by Georges Brandes and personally approved by Nietzsche [83, 213], burst into blossom in “Nietzsche: Attempt at a Mythology” (1918), the most popular book on Nietzsche in Weimar Germany by the Circle’s and Mann’s associate Ernst Bertram, as well as catalyzed Mann’s ideal of the “nobility of the spirit” [72]. Deep connections between Nietzsche, George and Austrian prodigy Hugo von Hofmannsthal who, like Mann, popularized the term “CR” in the field of cultural criticism in his 1927 address to students of the University of Munich “Literature as the Spiritual Space of the Nation,” are also widely known [44; 103]. According to Hofmannsthal, the Age of Enlightenment is nothing but a moment within the unfolding countermovement of CR of a scope unknown to Europe [44, 412–413].

Nietzscheanism as “radical aristocratism,” the formula first suggested by Georges Brandes and personally approved by Nietzsche [83, 213], burst into blossom in “Nietzsche: Attempt at a Mythology” (1918), the most popular book on Nietzsche in Weimar Germany by the Circle’s and Mann’s associate Ernst Bertram, as well as catalyzed Mann’s ideal of the “nobility of the spirit” [72]. Deep connections between Nietzsche, George and Austrian prodigy Hugo von Hofmannsthal who, like Mann, popularized the term “CR” in the field of cultural criticism in his 1927 address to students of the University of Munich “Literature as the Spiritual Space of the Nation,” are also widely known [44; 103]. According to Hofmannsthal, the Age of Enlightenment is nothing but a moment within the unfolding countermovement of CR of a scope unknown to Europe [44, 412–413].

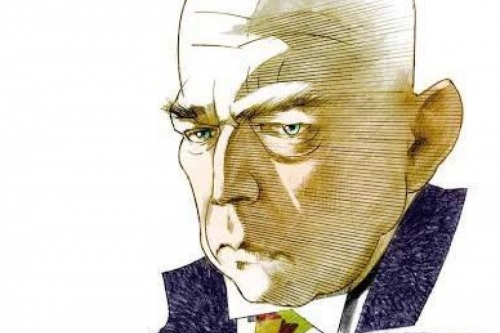

Mediated by Mann’s “Reflections of a Non-Political Man” (1918) equating the political with alien to the Germans “democraticism” [73], the myth of a new kingdom came to fruition in “The Third Empire” (1923) by the founder of Young Conservatism Moeller van den Bruck partially sharing Nietzsche’s disdain for Bismarck’s Second Reich. More politicized than Mann’s ideal of the third kingdom, just like his anti-Weimar June Club helping Franz von Papen to become the Chancellor of Germany in 1932, this conception, still, was ecumenical and strongly influenced by the Third Testament as envisaged by Dmitry Merezhkovsky, who sparked Moeller’s interest in Fyodor Dostoevsky, i.a. the motif of the Third Rome, and helped him to publish the first German translation of the writer’s Complete Works by Elisabeth Kaerrick (1906–1919) [7]. Both conceptions, in Merezhkovsky’s case, emphatically [111], echoed a heretic eschatological teaching by the 12th century mystic Joachim of Fiore, according to which the Age of the Father (Old Testament) and the Age of the Son (New Testament) will be followed by the Age of the Holy Spirit when man will ascend to the direct contact with God in freedom and love [94].

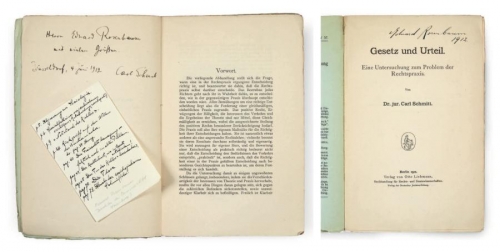

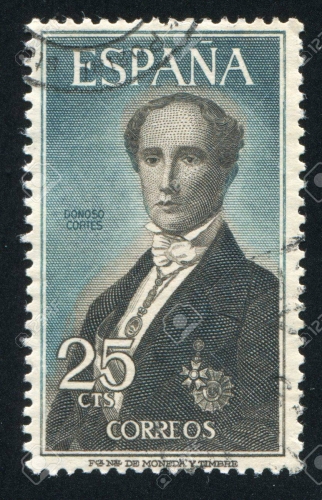

Further politicization of the term “CR” thanks to Edgar Julius Jung (1932)[11], an advisor and a speechwriter to von Papen, reached its peak in “political theology” of Reich’s “crown lawyer” Schmitt, at first, also a confidant to von Papen and General Kurt von Schleicher, the last Chancellor of Weimar Germany, initially seeking to tame Hitler’s dictatorship within the confines of a more “Prussian” state model [77, 301–302].

Again, these Nietzscheans did not fit in the real Third Reich: Moeller committed suicide in 1925 and did not witness the appropriation of “The Third Empire” by the self-proclaimed “drummer” of his ideas, Hitler [91, 278], George, who bequeathed his vision of the Secret Germany to Claus von Stauffenberg [see in more detail 93], the future leader of the anti-Hitler Prussian fronde, had emigrated and died before he could rethink Goebbels’ invitation to head the renewed Prussian Academy of Arts [105, 66], Jünger, as a popular military prosaic, sarcastically refused to join the latter [97, 143], Benn, whose expressionist embrace of decadence, including the rejection of a eugenic reading of the Superman[12], was condemned by the regime, soon enough was expelled from its ranks [96, 237–238], Hielscher, who led a clandestine resistance group, barely escaped the fate of the July 20 assassins thanks to the interference of the Ahnenerbe managing director Wolfram Sievers, albeit failed to return the favor at the trial over the latter [42: 424, 448–451], E. J. Jung, like von Schleicher, was killed by the SS during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934 [71, 220–226], Niekisch, an author of “Hitler, a German Calamity” (1932) was repressed and imprisoned in a concentration camp [82], Spengler resigned from the Board of Nietzsche Archive [108, 130–131], and so on. Only Heidegger, who eventually also left the Board [95, 144–145], and Schmitt were willing to take advantage of official positions in the Third Reich. Collaboration was so exceptional that the latest 2019 research by Mehring ranking Heidegger among conservative revolutionaries underlines that such an attribution is possible solely on the grounds of shared metaphysical ambitions [78, 33].

Apart from Hölderlin, Goethe and Nietzsche, George’s vision of the Secret Germany also strongly influenced Hielscher, a friend of Martin Buber and an editor of National-Revolutionary magazines “Der Vormarsch” and “Das Reich” who created a unique panentheistic theology and closely cooperated with Jünger [42, 216–225]. However, it was Jünger who revolutionized detached ideals of Young Conservatives by reinterpreting the Dionysian principle in Nietzsche’s philosophy of culture as the titanic principle of technology that defines the modernity. Returning Heidegger’s reproach that Jünger, employing visual metaphors of the metaphysical transition, was not a “thinker” [36, 263], Jünger claimed that Heidegger lacked a clear political vision and that is why he hoped that National Socialism would bring something new [39, 55]. At the same time, Jünger’s own “clear” vision performed a critical function, for, except for a short period of political involvement as a publicist, he remained “a seismograph of the epoch” [92, 525]. Yet, in contrast with “cultural pessimist” Heidegger who eventually concluded that “only a God could save us” [32], Jünger, in spite of an apparent impact of Heidegger’s and F.G. Jünger’s presumed “technophobia,” was unique in making the transvaluation of all values the programmatic quest of his entire body of work.

Apart from Hölderlin, Goethe and Nietzsche, George’s vision of the Secret Germany also strongly influenced Hielscher, a friend of Martin Buber and an editor of National-Revolutionary magazines “Der Vormarsch” and “Das Reich” who created a unique panentheistic theology and closely cooperated with Jünger [42, 216–225]. However, it was Jünger who revolutionized detached ideals of Young Conservatives by reinterpreting the Dionysian principle in Nietzsche’s philosophy of culture as the titanic principle of technology that defines the modernity. Returning Heidegger’s reproach that Jünger, employing visual metaphors of the metaphysical transition, was not a “thinker” [36, 263], Jünger claimed that Heidegger lacked a clear political vision and that is why he hoped that National Socialism would bring something new [39, 55]. At the same time, Jünger’s own “clear” vision performed a critical function, for, except for a short period of political involvement as a publicist, he remained “a seismograph of the epoch” [92, 525]. Yet, in contrast with “cultural pessimist” Heidegger who eventually concluded that “only a God could save us” [32], Jünger, in spite of an apparent impact of Heidegger’s and F.G. Jünger’s presumed “technophobia,” was unique in making the transvaluation of all values the programmatic quest of his entire body of work.

Approaching the article’s conclusions, let us summarize the trajectory of this quest. As the leader of the National-Revolutionary current and the author of “The Worker,” the early Jünger, reflecting upon irreversible changes brought by the first “industrial” war of 1914–18, elaborated rare positive remarks about socialism and the labor movement in Nietzsche’s notes to “The Will to Power.” According to them, the workers should learn to feel like soldiers and get honorarium instead of payment [87, 350]. They will be headed by an ascetic caste concentrating the plentitude of power. In the third section (1880) of “Human, All Too Human,” Nietzsche invoked the machine analogy for warfare and centralized party politics [86, 653]. Jünger developed both motifs [104, 146] in “The Worker” calling upon the workers[13] to feel like masters and a new frontline aristocracy laying claim to planetary domination [54: 76, 90].

Similarly to Heidegger, technology in Jünger’s thought becomes the very epitome of nihilism. Yet, he welcomes it as the most revolutionary power of the present and models the conservative-revolutionary subject after this vessel of creative nihilism. In the interwar period, Jünger describes the advent of a new human type carved by the metaphysical gestalt of the Worker and associated with unchained titan Prometheus “mobilizing the world by means of technology” [54, 165]. In the post-war period, he transformed into Gaia’s son Antaeus drawing strength from the earth and joining her revolt against the Olympians [52: 344–347, 580–582, 606–607, 650–651, 659]. Conceived by industrial total mobilization in the aftermath of the First World War, in the post-industrial society, soldier workers acquire softer protean features, but Zarathustra’s maxim of staying true to the earth stands paramount. According to the late Jünger, anthropocentric history is nothing but a layer of geohistory [52: 478–479, 502, 506–507, 533, 544, 588–589, 655–656].

That is how the early Jünger’s active nihilism counterbalanced the Young-Conservative fascination with the religious “Russian idea” and Dostoevsky’s “revolution out of conservatism” [109, 355]. Stating the ongoing “geological revolution” [114: 55–58], Jünger refers to the Joachist Age of the Holy Spirit [52, 414] only in “At the Wall of Time” (1959) when, remembering Nietzsche’s formula of the Superman as the conqueror of god and nothing, the pursued self-overcoming of nihilism enters the “creative” phase of challenging the nothing itself. Already in 1934 essay “On Pain” Jünger gives the following assessment of its proceedings: “We conclude, then, that we find ourselves in a last and indeed quite remarkable phase of nihilism, characterized by the broad expansion of new social orders with corresponding values yet to be seen” [55, 46]. In Klemperer’s words, “tough Nietzscheans” Spengler, Jünger and Moeller van den Bruck, in fact, “signed a pact with the devil” when took a risk to follow in Nietzsche’s footsteps and attempted to turn nihilism against itself [64, 153].

That is how the early Jünger’s active nihilism counterbalanced the Young-Conservative fascination with the religious “Russian idea” and Dostoevsky’s “revolution out of conservatism” [109, 355]. Stating the ongoing “geological revolution” [114: 55–58], Jünger refers to the Joachist Age of the Holy Spirit [52, 414] only in “At the Wall of Time” (1959) when, remembering Nietzsche’s formula of the Superman as the conqueror of god and nothing, the pursued self-overcoming of nihilism enters the “creative” phase of challenging the nothing itself. Already in 1934 essay “On Pain” Jünger gives the following assessment of its proceedings: “We conclude, then, that we find ourselves in a last and indeed quite remarkable phase of nihilism, characterized by the broad expansion of new social orders with corresponding values yet to be seen” [55, 46]. In Klemperer’s words, “tough Nietzscheans” Spengler, Jünger and Moeller van den Bruck, in fact, “signed a pact with the devil” when took a risk to follow in Nietzsche’s footsteps and attempted to turn nihilism against itself [64, 153].

Yet, in “Over the Line” (1950), Jünger optimistically referred to Nietzsche’s self-description as “the first perfect nihilist of Europe who, however, has even now lived through the whole of nihilism, to the end, leaving it behind, outside himself” [87, 190; 88, Preface] as well as Dostoevsky’s novels like “Crime and Punishment” promising a chance to overcome nihilism, to “recover” from it [57, 248–255]. The ways to do it he discussed in “The Forest Passage” (1951) and “Eumeswil” (1977) featuring the models of a sovereign individual: first the Forest Goer ostracized from a society, then a new Prussian anarchist, the Anarch, whose creative and meaningful nihilism is turned against sheer (passive) nihilism of “fake” emancipation theories and movements. At this point, Jünger, as the proponent of “heroic overcoming” of the technological challenge according to Rolf-Peter Sieferle [98], starts “summoning the gods” along with Heidegger and F. G. Jünger, “conservative critics of technology,” although the middle Heidegger’s remark on Jünger’s and Spengler’s technological “idolatry” (positive and negative, respectively) [35, 261] was an obvious overstatement.

Indeed, the late Jünger gets more pessimistic regarding the proximity of the anticipated metaphysical transition: according to the forecast from “The Change of the Gestalt. Prognosis for the 21 Century” (1993) resting on Hölderlin’s poem “Bread and Wine” [45], the titans will reign throughout the entire 21 century, whereas the gods will return only after a new Hesiodic titanomachia heralding the final end of the anthropocentric history [114: 40–41, 49–50, 53–54]. Promised by Joachim of Fiore “spiritualization” is again mentioned by Jünger [114, 54]. Yet another of his Hölderlin-inspired [114: 49–50, 51–52] beliefs that man should be friends both with the gods and “the iron ones,” remains unrevised. In “Nietzsche,” F. G. Jünger parallels the philosopher’s reverence for the tragic Dionysian art with the same Hölderlin’s sympathy for the titans and other primordial beings in poems like “Nature and Art or Saturn and Jupiter” [48]. Lamented by Heidegger, who discussed Nietzsche in the broader framework of lecture courses on Hölderlin and considered him superior to Nietzsche in terms of delving into the depth of Greek Dasein [27, 135; see also 76], in E. Jünger’s case, Hölderlin’s “flight of the gods” [47, 210] becomes a matter of approaching the “untethered titans” [46].

For this purpose, Jünger adds an intermediate figure of Dionysus, one of the late Nietzsche’s alter egos. As the myth tells us, once torn apart by the titans, Dionysus himself resembles them by his ecstatic overwhelming powers disclosed by Carl Gustav Jung in “Wotan” essay (1936), among others, alluding to the Unknown God from Nietzsche’s poetry [4, 311–312]. Surrounded by maenads, this “thrice-born” companion of Demeter and Persephone unites the living and the dead in a ritual procession. The god of the underworld in Orphic mysteries, Dionysus, in Jünger’s opinion, truly resides in Eleusis where the mysteries of resurrected nature are celebrated [51, 71].

As a philosophical writer, Jünger makes this observation in the technology-themed novella “Aladdin’s Problem” (1983) claiming that the true opposition is not between the Apollonian and the Dionysian, as Nietzsche believed, but between the divine and the titanic [51, 71], between the gods as patrons of creation, culture, meaning, poetry, memory, identity and borders and the titans standing for voluntarism, activism, productivity, speed, Sisyphean efforts, borderlessness, formlessness, hybris, etc. [52, also see 59]. Dionysus, accordingly, becomes a redeeming link between the anticipated breakthrough of divine timelessness and repetitive activities in concrete temples of the titans, factories, that is, work as the way to worship them, for the eternal recurrence Jünger associates precisely with the titans [114, 60–61].

Well-aware of Prussian militarism’s dangers, Nietzsche concurred on the dictum “when cannons roar, muses are silent” [86, 288–289]. Nietzsche’s disciple and Jünger’s teacher, highly influential both in Young-Conservative and National-Revolutionary circles, it was Spengler who reinterpreted the Apollonian-Dionysian opposition through the prism of Nietzsche’s phenomenology of European decadence, as well as “young” and “old” peoples as the dichotomy of culture, when a cultural organism is full of vital creative forces, and civilization, when only its “mummy” remains, as it is currently the case at the late “Caesarist” phase of Western “Faustian” soul. At this stage of the aged and “declined” West [100: 146, 194–195, 453], art, literature and architecture are far beyond the peak; only calculation, construction, spatial expansion and quantitative growth in general matter [100, 1–67]. Having borrowed Spengler’s “world-historical perspective,” also indebted to Joachim of Fiore [101, 31], and rendered the contrast of organic phases as the clash and coexistence of the divine and the titanic, Jünger made a big step forwards as compared to the Young-Conservative actualization of Nietzsche.

To sum up, starting with the very etymological level, CR may be regarded as the fullest attempted explication of Nietzscheanism as a dynamic worldview. In turn, the futuristic relevance of its pivotal message of the self-overcoming of nihilism is comprehensively elucidated by Ernst Jünger as the face of CR, according to Mohler, and the only true Nietzschean, according to Heidegger. Supplemented by Locchi’s spherical conception of history, the potential of Nietzscheanism is revealed in the discussions of Jünger and Heidegger on the prospects for the great metaphysical transition after the Interregnum, in Jünger’s terms, or the second beginning of metaphysics, in Heidegger’s. Besides, Jünger’s distinction of the gods and the titans is the insightful upgrading of Nietzsche’s dichotomy of the Apollonian and the Dionysian bringing to the surface a lacking dimension of technology in Nietzsche’s work. Filling this critical gap in the modern Nietzscheana will open new horizons for the interdisciplinary application of Nietzsche’s ideas and the “rebirth” of philosophy in the light of the conservative-revolutionary discovery of super- or altmodern.

Notes

- 1 See “Historical Dictionary of Nietzscheanism” [6].

- 2. Stefan Breuer, the most influential critic of CR as a coherent current, in the end, could not help using this term himself and listed it among the most successful inventions of contemporary history of ideas [5, 1].

- 3. Needless to say, historians of philosophy are interested in metaphysical, not strictly social aspects of CR, which otherwise would be addressed in this research in more detail. In this respect, vitalist Nietzscheanism in Jünger’s interwar political journalism is less important for this study than his rethinking of Nietzsche’s active nihilism as titanism and philosophical-historical sophistication of the “transvaluation of all values.”

- 4. Rendered as “Empire” instead of “Reich” in its condensed English edition [79] (first translated by Emily Overend Lorimer in 1934) precisely to disambiguate it from the National Socialist political regime.

- 5. Not to be confused with Nietzsche’s criticism of petty Germanness.

- 6. The opposition of the “Judeo-Christian” and “archaic” worldview, “history” and “cosmos” was popularized by Romanian historian of religion Mircea Eliade whose name is fairly included in the related tradition of thought. Although in the introduction to his magnum opus “Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return” (1949) he considered Nietzsche’s interpretation of an eponymous Greek myth purely modern [8], the longing for the world’s re-sacralization, which, according to Eliade, is promised by annual ritual participation of an archaic man in the New Year recreation of the world (partaking of the myth’s cosmological function), does correlate with “open opportunities” of the eternal recurrence as the axiological notion. This polemics with the contradiction detected in Nietzsche’s thought by Löwith (see below), actually, is shared by Eliade who believes that the myth frees humanity from the cage of history, more precisely, predestination of the Judeo-Christian eschatology rather than thrusts into the prison of nature.

- 7. Here, Nietzscheanism almost coincides with futurism the technological advantages of which, in Faye’s opinion, are artificially restrained by the egalitarian and humanistic modernity. The spherical view of history, likewise, has nothing to do with a cyclic return to the past, which, as Faye claims, has failed and has led to the catastrophe of modernity. Instead, he employs a metaphor of a billiard ball which chaotically moves across the table. After a number of spins, the same point might touch the cloth several times, but its position in space will be different. As a result, Nietzscheanism underlies the “re-emergence of archaic social configurations in a new context” [10, 74], which is the basic intuition behind archeofuturism.

- 8. However,Löwith expressed his concern with Jünger’s interwar attack on a bourgeois individual in this book [69].

- 9. The resemblance, again, is homological, for Jünger’s philosophy of subject, at least in its gestalt-related part, rests on Leibniz’s “monad,” Plato’s “idea” and Goethe’s “urplant” rather than Nietzsche’s Superman in a narrow sense.

- 10. Apart from elucidating Nietzsche’s conception of creative nihilism, such political projections help to reveal that subtle way in which Nietzscheanism may be converted into ideology, and never vice versa (when ideological postulates receive philosophical substantiation).

- 11. “By “conservative revolution” we mean the return to respect for all of those elementary laws and values without which the individual is alienated from nature and God and left incapable of establishing any true order. In the place of equality comes the inner value of the individual; in the place of socialist convictions, the just integration of people into their place in a society of rank; in place of mechanical selection, the organic growth of leadership; in place of bureaucratic compulsion, the inner responsibility of genuine self-governance; in place of mass happiness, the rights of the personality formed by the nation” [50, 352].

- 12. “Since then we have studied the bionegative values, which are rather more harmful and dangerous to the race but are a part of mind’s differentiation: art, genius, the disintegrative motifs of religion, degeneration; in short, all the attributes of creativity” [3, 383].

- 13. In “The Worker,” work is understood as the all-pervading lifestyle brought by “titanic” industrialization and has no relation to its didactic cultural purpose, individual or collective.

Literature

- Aschheim S. E. The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany : 1890–1990 / Steven E. Aschheim // Weimar and Now : German Cultural Criticism. – Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford : University of California Press, 1994. – Vol. 2. – 337 p.

- Bataille G. Nietzsche et les fascistes. Une reparation par G. Bataille, P. Klossowski, A. Masson, J. Rollin, J. Wahl / Georges Bataille // Acéphale (Religion, sociologie, philosophie). – 1937. – № 2. – P. 3–21.

- Benn G. After Nihilism / Gottfried Benn // The Weimar Republic Sourcebook ; [ed. by Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, Edward Dimendberg. First published in : Nach dem Nihilismus (Berlin : Gustav Kiepenheuer, 1932, 7–17)]. – Berkley / Los Angeles / London : University of California Press, 1995. – Pp. 380–384.

- Bishop P. The Dionysian Self : C.G. Jung’s Reception of Friedrich Nietzsche / Paul Bishop. – Berlin / New York : Walter de Gruyter, 1995. – 411 p.

- Breuer S. Anatomie der konservativen Revolution / Stefan Breuer. – Darmstadt : Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1993. – 232 S.

- Diethe C. Historical Dictionary of Nietzscheanism / Carol Diethe // Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements Series (2nd ed.). – Lanham, Maryland ; Toronto ; Plymouth, UK : Scarecrow Press, 2007. – Book 75. – 424 p.

- Dostojewski F. Sämtliche Werke in 25 Bänden ; [unter Mitarbeit von Dimitri Mereschkowski, hrsg. von Moeller van den Bruck, übertragung E. K. Rahsin, 1. Auflage] / Fjodor Dostojewski. – München : R. Piper & Co, 1922–1925.

- Eliade M.Cosmos and History : The Myth of the Eternal Return / Mircea Eliade ; [Trans. by Willard R. Trask]. – New York : Harper & Brothers, 1954. – 176 p.

- Ernst Jünger–Martin Heidegger : Briefwechsel 1949–1975 ; [Unter Mitarbeit von Simone Maier ; hrsg., kommentiert und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Günter Figal]. – Stuttgart : Klett-Cotta ; Frankfurt am Main : Vittorio Klostermann, 2008. – 317 S.

- Faye G. Archeofuturism : European Visions of the Post-Catastrophic Age ; [trans. by Sergio Knipe ] / Guillaume Faye. – London : Arktos, 2010. – 249 p.

- Figal G. Erörterung des Nihilismus. Ernst Jünger und Martin Heidegger / Günter Figal. – Etudes Germanistiques, 1996. – № 51. – S. 717–725.

- Fischer H. Nietzsche Apostata : oder Die Philosophie des Ärgernisses / Hugo Fischer. – Erfurt : K. Stenger, 1931. – 313 S.

- Forrest D. S. Suprahumanism : European Man and the Regeneration of History / Daniel S Forrest. – London : Arktos, 2014. – 268 p.

- George S. Das Neue Reich / Stefan George // Sämtliche Werke in 18 Bänden ; [Hrsg. Von Ute Oelmann, 1. Auflage]. – Band 9. – Stuttgart : Klett-Cotta, 2011. – 149 S.

- George S. Der Stern des Bundes / Stefan George // Stefan George Stiftung, bearbeitet von Ute Oelmann, 2. Auflage]. – Band 8. – Stuttgart : Klett-Cotta, 2011. – 153 S.

- Greiffenhagen M. Das Dilemma des Konservatismus in Deutschland / Martin Greiffenhagen. – München : Piper, 1977. – 425 S.

- Guillaume Faye on Nietzsche ; [trans. by Greg Johnson]. – [Електронний документ]. – Режим доступу: https://www.counter-currents.com/2012/07/guillaume-faye-o...

- Habermas J. On Nietzsche’s Theory of Knowledge : A Postscript from 1968 / Jürgen Habermas // Nietzsche, Theories of Knowledge, and Critical Theory : Nietzsche and the Sciences [ed. by Babette Babich and Robert E. Cohen]. –Dordrecht : Kluwer Academic Publishers. – Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. – Vol. 203. – Pp. 209–223.

- Habermas J. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity : Twelve Lectures [trans. by Frederick G. Lawrence] / Jürgen Habermas. – Cambridge, UK : John Wiley & Sons, 2018. – 456 p.

- Heidegger M. Beiträgе zur Philosophie (Vom Ereignis) / Маrtin Heidegger // Gesamtausgabe : in 102 Bänden;

- Heidegger M. Brief über den Humanismus / Маrtin Heidegger // Gesamtausgabe : in 102 Bänden ; [herausgegeben von Friedrich-Wilhelm von Herrmann, 1. Abteilung: Veröffentlichte Schriften 1914-1970]. – Frankfurt am Main : Vittorio Klostermann, 1989. – Bd. 9 : Wegmarken. – S. 313–364.

- Heidegger M. Das Rektorat 1933/34 – Tatsachen und Gedanken (1945) / Маrtin Heidegger // Gesamtausgabe : in 102 Bänden ; [hrsg. von Hermann Heidegger, I. Abteilung : Veröffentlichte Schriften 1910–1976]. – Frankfurt am Main : Vittorio Klostermann, 2000. – Bd. 16 : Reden und andere Zeugnisse eines Lebensweges. – S. 372–394.

- Heidegger M. Der deutsche Student als Arbeiter (Rede am 25. November 1933) / Маrtin Heidegger // Gesamtausgabe : in 102 Bänden ; [hrsg. von Hermann Heidegger, I. Abteilung : Veröffentlichte Schriften 1910–1976]. – Frankfurt am Main : Vittorio Klostermann, 2000. – Bd. 16 : Reden und andere Zeugnisse eines Lebensweges. – S. 198–208.

- Heidegger M. Die Grundbegriffe der Metaphysik. Welt – Endlichkeit – Einsamkeit (Wintersemester 1929/30) / Martin Heidegger // Gesamtausgabe : in 102 Bänden ; [Hrsg. von Friedrich-Wilhelm von Herrmann]. – Frankfurt am Main : Vittorio Klostermann, 1983. – Bd. 29/30. – 544 S.