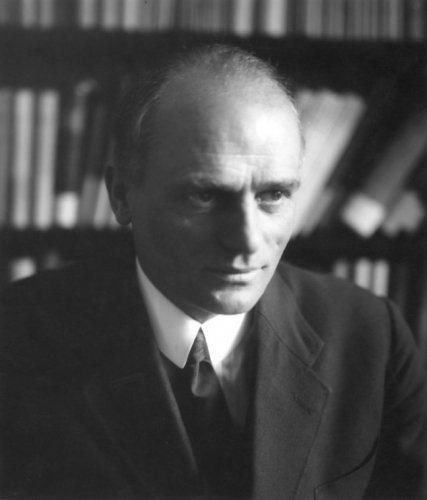

The ideas of Carl Schmitt (1888-1985), a man known as ‘the crown jurist of the Third Reich’, have enjoyed enormous currency among mainland Chinese scholars since the 2000s. The role of prominent academics such as Liu Xiaofeng 刘小枫, Gan Yang 甘阳 and Wang Shaoguang 王绍光 in promoting Schmitt’s ideas, and the fact that his theories on the state help legitimise one-party rule, have ensured that China’s ‘Schmittian’ discourse has been both fashionable and profitable (the usually heavy hand of the censors touches only ever so lightly on articles and books inspired by Schmitt).

Schmitt joined the German National Socialist, Nazi, party in 1933 when Adolf Hitler became Reichskanzler of the Third Reich and enthusiastically participated in the purge of Jews and Jewish influence from German public life. The anti-liberal and anti-Semitic Schmitt was a keen advocate of National Socialist rule and he sought to become the Third Reich’s official legal theorist. By late 1936, however, articles in the Schutzstaffel (SS) newspaper Das Schwarze Korps accused him of opportunism and Catholic recidivism. Despite the protection of Herman Göring, Schmitt’s more lofty ambitions were frustrated and thereafter he concentrated on teaching and writing.

Schmitt’s stark view of politics has attracted much criticism and debate in Euro-American scholarship. Thinkers on the left are ambivalent about his legacy, although despite the odeur of his Nazi past, he remains popular among theory-seeking academics. They see Schmitt’s ideas as deeply flawed while acknowledging his acuity and studying his writings for the insights they offer into the limitations of liberal politics, even as they impotently argue from the lofty sidelines of contemporary real-world governmentality.

In China, the reception of Schmitt’s ideas has been more straightforward; after all, even Adolf Hitler has enjoyed a measure of uncontested popularity in post-Mao China. Mainland scholars who seek to strengthen the one-party system have found in Schmitt’s writings useful arguments to bolster the role of the state, and that of the paramount leader (or Sino-demiurge), in maintaining national unity and order.

To date, Schmitt’s Chinese intellectual avatars have neglected a few key concepts in the meister’s oeuvre that could serve well the party-state’s ambitions under Big Daddy Xi Jinping. We think in particular of Schmitt’s views of Grossraum (‘Big Area’), or spheres of influence. Inspired by his understanding of the Monroe Doctrine propounded by the US in support of its uncontested hegemony in the ‘New World’, Schmitt’s Grossraum was to justify the German Reich’s European footprint and legalise its dominion. As China promotes its Community of Shared Destiny 命运共同体 in Asia and the Pacific (see our 2014 Yearbook on this theme), the concept of spheres of influence is enjoying a renewed purchase on the thinking of some international relations thinkers. See, for instance, the Australian scholar Michael Wesley’s unsettling analysis in Restless Continent: Wealth, Rivalry and Asia’s New Geopolitics (Black Ink, 2015).

During her time at the Australian Centre on China in the World in late 2013, the legal specialist Flora Sapio presented a seminar on the subject of Schmitt in China, and she kindly responded to our request to write a substantial essay on this important ‘statist’ trend in mainland intellectual culture for The China Story.

Flora Sapio is a visiting fellow at the Australian Centre on China in the World. Her research is focused on criminal justice and legal philosophy. She is the author of Sovereign Power and the Law in China (Brill, 2010); co-editor of The Politics of Law and Stability in China (Edward Elgar, 2014); and, Detention and its Reforms in China (forthcoming, Ashgate, 2016). — The Editors

___________________

We set up an ideal form [eidos],

which we take to be a goal [telos],

and we then act in such a way

as to make it become fact. [1]

The Schmittian intellectual likes to play Russian roulette but with an intriguing new twist: she believes that a single round has been placed in the revolver but she also knows this may not be the case. In fact, the only one who knows the truth is the Sovereign, a figure whose will the Schmittian cannot fathom. The Sovereign decides who plays the game and how many times. If the Schmittian turns downs this offer that can’t be refused, she would be declared an enemy and shot. Given how this intellectual predicament, masquerading as a position, commits one to always comply with the Diktat of the Sovereign, we must ask ourselves: why have several prominent Chinese intellectuals elected Herr Professor Carl Schmitt, Crown Jurist of the Third Reich, to be their intellectual patron saint?

Fulfilling a dream of wealth and power has been a feature of Chinese history and intellectual life since the late-nineteenth century. Chinese dreams, whether they be those dreamt up around the time of the 1919 May Fourth Movement, or the visions conjured up almost a century later by party-state-army leader Xi Jinping, involve a conviction that China is endowed with a distinctive national essence 国粹. The national essence is to China what the soul is to man. Just as (religious) man seeks to ascend to heaven by cultivating and purifying his soul, China can become wealthy and powerful if its national essence is enhanced and cleansed of polluting influences. The New Enlightenment Movement which emerged following the ideological thaw of the late 1970s saw traditionalism and feudalism being accused of holding China back. In the 1980s, Chinese intellectuals argued over how to revive the nation’s true nature, with many recommending an eclectic combination of Western values, theories and models in the process.[2] The Movement would witness a reversal of fortunes after the 1989 Beijing Massacre. Powerful nationalist sentiments followed in the 1990s, fuelled in part by the state and in part by a reaction to the inequalities of market reform, coupled with the public’s response to external events.

Telling Friend from Enemy

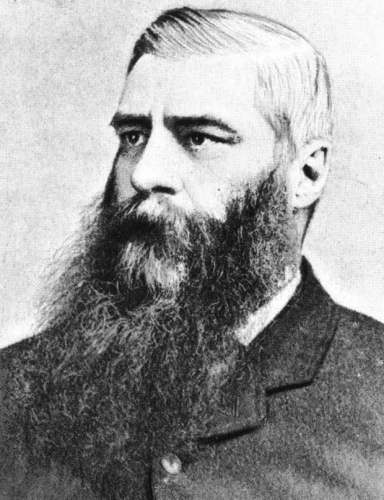

Liu Xiaofeng

It is against this fast-changing backdrop that China’s Carl Schmitt fever must be situated. It would be wrong to see the ‘invisible hand’ of the State at work behind the fad.[3] The reception of Carl Schmitt by Chinese intellectuals, some of whom are key members of the New Left, was possible only because of the work undertaken by the influential scholar Liu Xiaofeng 刘小枫 (currently a professor at Renmin University in Beijing) to translate, comment on and promote Schmitt’s opera omnia. The holder of a theology doctorate from the University of Basel, Liu argued in his PhD thesis for Christianity to be separated from both its ‘Western’ and ecclesiastical dimensions, thereby allowing Christian thought to be treated purely as an object of academic research. Christian thought, so conceived, could thus be put in dialogue with other disciplines and contribute, among other things, to the modernisation of Chinese society. Liu related the development of Christianity to the development of nations and their identities, reflecting Max Weber’s argument in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, a book that was widely read in Chinese translation and highly influential in 1980s’ mainland intellectual circles.

Liu argued that in China Christianity took root in a unique way and was independent of missionary evangelisation. Liu’s sinicisation of Christian theology enabled the development of a Sino-Christian discourse in mainland intellectual circles focused on solving ‘Chinese problems’.[4] This was, and remains, a discourse that engages with such issues as economic development, social justice, social stability and most important of all, the political legitimacy of Communist Party rule.

Liu calls himself a ‘cultural Christian’, meaning a Christian without church affiliation: one who conducts research on theological arguments and concepts for the benefit of his nation. It is no surprise then that by understanding research in these terms, Liu soon developed a fervid interest in Carl Schmitt. To Carl Schmitt, the state has a theological origin — it must be conceived of as a divine-like entity if it is to hold back chaos and disorder so as to secure peace and prosperity. Schmitt’s thesis also implies that all modern political concepts originate in theology, which in turn makes theology amenable to being treated as a form of statecraft.[5] From the outset, Liu showed himself highly receptive to these Schmittian ideas. We must also note the ease with which the writings of Carl Schmitt succeeded in China. Unlike Chinese scholarship based on Western liberal-democratic models, which was and remains prone to censorship, Chinese aficionados of Schmitt’s ‘friend-enemy’ distinction and his critique of parliamentary democracy were unimpeded in their pursuits.

As a conservative Catholic, Schmitt understood politics (which he termed ‘the Political’, in an attempt to capture its essence) as based ultimately in the friend-enemy distinction. For Chinese intellectuals who had been brought up on Maoist rhetoric,[6] and were familiar with the adaptation of this dyad of friend-enemy 敌我 for post-Maoist political use,[7] Schmitt’s friend-enemy distinction had a powerful resonance. This was a distinction that could be used to name any pair of antagonists, as long as the attributes of the named antagonists could be demonstrated to be so thoroughly incommensurable as to make them want to destroy each other, in order for each to preserve its own identity.

The friend-enemy distinction was a central feature of Schmitt’s political and constitutional theory: it grounded his critique of parliamentary democracy as well as his ideas about ‘the state of exception’ and sovereignty. Liberal democracies, Schmitt held, were trapped in false political categories: they ignored the crucial distinction between friend and enemy and therefore exposed themselves to the risk of capture by the interests of wealthy individuals and factions, who would use the state for their own goals rather than for the greater good of the people. According to Schmitt, liberal polities pretended that the government and the people were subject to the demands of reliable legal norms but the pretence was shattered whenever an internal or external enemy threatened the nation and national security. Reliance on parliamentary debates and legal procedures, he argued, posed the risk of throwing a country into chaos because they hampered the adoption of an effective and immediate response.

Schmitt held that sovereignty resides not in the rule of law but in the person or the institution who, in a time of extreme crisis, has the authority to suspend the law in order to restore normality. The authority to declare a state of emergency or Ausnahmezustand thus has unquestioned legitimacy, regardless of whether it takes the form of an actual (written) constitution or an implicit (unwritten) one. Yet how can a sovereign power that exists above and outside the law enjoy any legitimacy? Wouldn’t such a power be self-referential and premised on sheer violence? According to Schmitt, the legitimacy of such a power can be defended if one delinks the concepts of liberalism and democracy. He held that the two were substantially distinct and set about redefining the latter.

Schmitt argued that a polity founded on the sways of popular opinion could hardly be legitimate. He appealed instead to ideas about equality and the will of the people.[8] For Schmitt, political equality meant a relationship of co-belonging between the ruler and the ruled. As long as both ruler and ruled were members of the same group, or ‘friends’ holding identical views about who the enemy was, a polity was democratic. Schmitt held that where the will of the people mirrored the sovereign’s decision, rule was, indeed, by the people. Such a popular will need not be formed or expressed in terms of universal suffrage: the demands made at a public rally were sufficient to convey a popular will at work.[9]

Schmitt’s eclectic definition of the popular will led him to conceive of democracy as a democratic dictatorship. This way of thinking was very attractive to intellectuals who favoured statist and nationalist solutions to political problems and issues of international relations.[10]

Why Schmitt?

The reasons for Chinese intellectuals’ fascination with Carl Schmitt are straightforward. The related concepts of ‘friend and enemy’, ‘state of exception’ and ‘decisionism’ are simple and usable. Policy advisors and policy-makers can easily apply these concepts in their analysis of situations. Schmitt’s vocabulary can also lend theoretical weight to the articulation of reform proposals, to serve as a source of inspiration or to furnish building blocks in the construction of pro-state arguments in political science and constitutionalism. Moreover, Schmitt’s friend-enemy distinction complements and provides justification for the many narratives of nationalism and cultural exceptionalism that have become influential in Chinese scholarship in recent years. These narratives are by no means unique to China but we must note that they are at odds with the universalist and internationalist aspects of Chinese Communism as state doctrine. The gist of the Chinese Schmittian argument is that the world is not politically homogeneous but a pluriverse where radically different political systems exist in mutual antagonism. China, accordingly, is not only entitled to but must find and defend its own path to power and prosperity.

The Chinese Schmittian argument justifies the party-state’s view that Western parliamentary democracy, thick versions of the rule of law, civil society, and the values and institutions of Western constitutionalism are all unsuitable for China. Schmitt’s argument allows those who hold this view to say that such ideas belong to an ‘alien’ liberal cosmopolitanism that is ultimately damaging for the Chinese way of life. In 2013, a state directive dubbed ‘Document 9’, outlined these ideas as posing a serious threat to China’s ‘ideological sphere.’[11]

Carl Schmitt’s views have now become influential in mainland Chinese scholarship and he is frequently quoted as a foreign authority in arguments mounted against ‘liberalism’ and Western or US-inspired models of economic and political development. But the fact that Schmitt’s philosophy premises politics on exclusion and even the physical elimination of the enemy (should such an elimination be deemed necessary to the achievement of an ideological goal), is something never raised in Chinese intellectual discourse. The friend-enemy distinction encourages a stark form of binary thinking. The category of friend, however substantively defined, can be conceived only by projecting its opposite. ‘Friend’ acquires meaning through knowing what ‘enemy’ means. The attributes used to define a ‘friend’ can, as Schmitt pointed out, be drawn from diverse sources. Religion, language, ethnicity, culture, social status, ideology, gender or indeed anything else can serve as the defining element of a given friend-enemy distinction.

The friend-enemy distinction is a public distinction: it refers to friendship and enmity between groups rather than between individuals. (Private admiration for a member of a hostile group is always possible). The markers of identity, however, are relatively fluid because a political community is formed via the common identification of a perceived threat.[13] In other words, it is through singling out ‘outsiders’ that the community becomes meaningful as an ‘in-group’. This Schmittian way of defining a ‘people’ elides the necessity of a legal framework. A ‘people’, as a political community in the Schmittian sense, is primarily concerned about whether a different political community (or individuals capable of being formed into a community) poses a threat to their way of life. For Schmitt, the friend-enemy distinction is a purely political distinction and to be treated as entirely separate from ethics.[14] Since the key concern is the survival of the ‘in-group’ as a ‘people’ and a political community, Schmitt’s argument implies that the elimination of a perceived enemy can be justified as a practical necessity.[15] Hence, those who call themselves Schmittian intellectuals should be aware that Schmitt’s argument is framed around necessity. So long as a there is a necessary cause to defend, any number of deaths can be justified.

Moreover, necessity is premised on antagonism. The friend-enemy distinction grounds every aspect of Schmitt’s thinking about politics and constitutionalism. But this is precisely why Schmittian concepts have inspired some of the most effective analyses of Chinese politics and constitutionalism. Schmitt’s view of sovereignty as requiring the ruler to have the freedom to intervene as necessary for the good of the whole country is of a piece with the ‘statist intellectual trend’ 国家主义思潮 in Chinese scholarship of which Wang Shan 王山 and Wang Xiaodong 王小东 were and remain key proponents.

This movement led to the development of an argument around the importance of ‘state capacity’. In an influential 2001 work, the political scientists Wang Shaoguang 王绍光 and Hu Angang 胡鞍钢 presented ‘state capacity’ as the key to good governance and policy. They argued against democratic decision-making processes by outlining their adverse consequences. According to them, such processes can involve lengthy discussions, leading to delays in policy implementation or even to political and institutional paralysis. They saw ‘the capacity on the part of the state to transform its preference into reality’ as crucial for protecting the nation’s well-being.[16] Since then, there have been many academic publications in mainland China that present ‘state capacity’ with its corollaries of social control and performance-based legitimacy as a viable alternative to parliamentary democracy.

Quotable and Useful Ideas

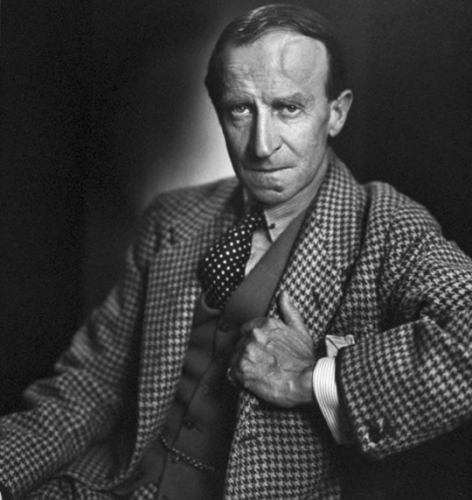

Wang Shaoguang

In a subsequent work provocatively titled Four Chapters on Democracy,[17] Wang Shaoguang pays implicit tribute to Carl Schmitt’s Four Chapters on the Concept Sovereignty. Like Schmitt, Wang rejects representative democracy on the pragmatic and utilitarian grounds that such a system is ultimately incapable of improving the welfare of the entire population. Echoing the Schmittian argument of parliamentarianism’s capture by interest groups, Wang argues that universal suffrage plays into the hands of those endowed with financial means, while reducing the have-nots to the role of passive spectators.

Wang also presents a Schmittian-inspired notion of ‘the people’ as the basis of a responsive democracy, arguing that countries with a strong assimilative capacity and steering capacity (that is, the people united under a strong leader) have a higher quality of democracy. Some of Wang’s vocabulary has come from democratic political theorist Robert Dahl, but it is Schmitt’s argument that underlies Wang’s explanations of responsive democracy and state effectiveness.[18]

The ‘state capacity’ argument advanced by Wang, Hu and others has enjoyed the attention of Western scholarship on contemporary China for a decade or more. It is frequently cited in academic publications about China’s economy, political economy and public administration.

In many of these published studies (in English and other European languages), ‘state capacity’ is treated as having afforded the Chinese government an effective means for accelerating China’s economic development. The evidence of China’s economic success, in turn, has also encouraged some academics to propose that an authoritarian government may be more efficient in delivering economic growth than a liberal-democratic one. It is baffling that among those who hold this view, some have also claimed to ‘support China’s transition to a more open society based on the rule of law and human rights’.[19] If by ‘more open’ they mean greater freedom of the liberal-democratic variety, then this goal is at odds with their argument that the Chinese Communist Party’s one-party system must be strengthened through a range of capacity-building initiatives.

Schmitt’s argument has also been very influential in mainland scholarship on constitutional theory. After Mao, the party-state needed — and to an extent still needs — a distinctively Chinese political ontology. This ontology — or way of conceptualizing and understanding the world — has to include a bipartite political system, in which an extensive party apparatus exists both inside and outside the law, wielding supreme power over the state. Furthermore, this party-state system has to be internally coherent: capable of self-perpetuation to enjoy legitimacy in the eyes of both the Chinese people and foreigners. Chinese legal academics such as Qiang Shigong 強世功, who view constitutionalism in these terms, began in the 2000s to defend their position by deploying the whole arsenal of Schmittian philosophy. The result was a trinity of concepts: ‘the state of exception’, ‘constituting and constituted power’ and ‘political representation by consensus’ (representing respectively the terms State, Movement and People as used by Schmitt in his 1933 work, Staat, Bewegung, Volk), which these academics hailed as the true essence of Chinese law.

When Schmitt is directly quoted, his influence is obvious. But there are scholars such as Cui Zhiyuan 崔之元 who have made tacit use of Schmitt in their theorising about governance and politics in China. Schmitt’s influence is evident in Cui’s understanding of China as a ‘mixed constitution’ involving ‘three political levels’.[20] Similarly, Chen Ruihong’s 陈瑞洪 notion of ‘virtuous unconstitutionality’;[21] Han Yuhai’s 韩毓海 doctrine of ‘constitutionalism in a proletarian state’;[22] Hu Angang’s 胡鞍钢 rebranding of the Politburo as a ‘collective presidency’;[23] Qiang Shigong’s 强世功 model of ‘shared sovereignty under a party-state leader’,[24] are other prominent Schmittian-inspired arguments to have emerged in the last two decades. These theories belong to different areas of Chinese constitutional scholarship,[25] but they all recast the Schmittian sovereign in Chinese party-state garb. Specifically, each of these theories defends political representation by consensus, linking consensus to broad acceptance of the Diktat of the party-state. In one way or another, they also all present the ‘West’ and its political and legal institutions as unsuited for China.

To date, Western legal scholarship has properly examined neither these influential arguments nor their legal and political ramifications. But there are several scholars who have indicated the relevance of these arguments for China. For instance, Randall Pereenboom presents a useful account of the Chinese legal system as a pluriverse populated by different conceptions of the rule of law.[26] Michael Dowdle has argued, in sympathy with the New Left position, that liberal conceptions of constitutionalism are limited and that there is room for state power to be legitimated in other ways.[27] Larry Catà Backer has conceived the Party and the State as a unitary whole, a theoretical construct inspired by the reality of Chinese institutions, which allows for shuanggui 双规 detention on legal grounds.[28] These works can be read as putting the finger in the wound of some of our own contradictions. We may criticise the Chinese legal system from the purview of an idealised model of the Western legal system but at the same time we cannot avoid dealing with Chinese law as it is discussed and presented, and as it exists within the People’s Republic of China.

Several mainland intellectuals have pointed out that although Chinese Schmittians are fond of attacking the West, they don’t explain why they rely on a German political thinker to do so.[29] This criticism is useful, but it ignores how advocates of indigenous concepts and models, ‘Third Way’ proponents and Western-style liberals alike have yet to examine their uses of a logic that belongs more to Western metaphysics than to indigenous Chinese thought (Confucian or other forms of thinking derived from pre-Qin sources). This Western logic requires one to construct an ideal model of how a political system, a legal system, a society or truly any other entity should be, into which we then attempt to ‘fit’ reality, often without heeding the consequences of doing so.

At any rate, we can see that Schmittian concepts have become far more dominant than liberal ones in mainland legal scholarship. Political moderates such as He Baogang 何包钢[30] have sought to accommodate the arguments of both sides by proposing, for instance, that a constitutional court should have the power to decide on what constitutes a ‘state of exception’, on which the absolute authority of a Schmittian sovereignty is predicated. But such attempts at accommodation only reveal the weakness of the liberal position by comparison with the Schmittian one. Professor He reflects the quandary of those who seek to defend elements of a liberal democratic model (such as judicial independence) within an unaccommodating Schmittian friend-enemy paradigm.

Schmitt und Xi

Since Xi Jinping became China’s top leader in November 2012, the friend-enemy distinction so crucial to Carl Schmitt’s philosophy has found even wider applications in China, in both ‘Party theory’ and academic life. The selective revival of the Maoist rhetoric of struggle to launch a new mass line education campaign on 18 June 2013 is a good example of how the friend-enemy distinction has been adapted for present-day one-party rule.

To see the consequences of Schmittian reasoning, it is important that we consider the motivations behind Carl Schmitt’s privileging of the friend-enemy distinction and absolute sovereignty. Schmitt believed that he was theorising on behalf of the greater good. His philosophy can be rightly described as a political theology because it was inspired by the Biblical concept of kathechon [from the Greek τὸ κατέχον, ‘that what withholds’, or ὁ κατέχων, ‘the one who withholds’] — the power that restrains the advent of the Anti-Christ.[31] Schmitt transposed kathechon into a political register, defining it as the power that maintains the status quo.[32] This power can be exercised by an institution (such as the nation-state) or by the sovereign (whether as dictator or defender of the constitution). A logical consequence of Schmitt’s belief in the kathecon was the conflation of religious and political imagery. Forces which were against a given sovereignty were nothing less than evil enemies sowing the seeds of chaos and disorder. Accordingly, to protect one’s nation or sovereign was a sacred duty and the path to salvation.

We may fundamentally disagree with Chinese intellectuals who have opted to promote a Schmittian worldview. But if we are to defend intellectual pluralism, we must accept that people are free to choose their own point of view. In fact, the emergence of a Chinese Schmittian discourse in academic scholarship augments the current range of Schmittian-inspired arguments produced as much by scholars on the right as on the left in European and American settings.

We must also note that in China, as everywhere else, political differences of the left and right, or between the New Left and liberals, emerge out of and remain largely trapped in a common setting: what may be called a common political-theological paradigm, to use Schmitt’s vocabulary. Political differences are made meaningful in a common setting, out of which people receive and develop their mental schemes, their political vocabularies and the entire universe of concepts for thinking politics. The political-theological paradigm of one-party rule in the People’s Republic of China has ensured that Chinese intellectuals are bound to the mental schemes, vocabularies and concepts that this paradigm has allowed to be generated. What we must bear in mind is that Western ideas must also be accommodated into the paradigm.

Living in a country that has witnessed a rapid rise to economic wealth and global power over three decades, Schmittian intellectuals in today’s China have sought to marry a philosophy that emerged and developed in Germany from the 1920s to the 1940s with ideas about statehood that first became popular in China in the 1980s. This mix of Schmittian thinking and ‘statism’ has now become very influential in Chinese academic circles. But there doesn’t seem to be much concern about the destructive potential of Carl Schmitt’s philosophy.

_____________

Notes:

* The author would like to thank the editors of The China Story, in particular Gloria Davies, for their intellectual and stylistic contributions to this study. Subheadings have been added by the editors.

[1] François Jullien, A Treatise on Efficacy: Between Western and Chinese Thinking, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004, p.1.

[2] On the New Enligthenment Movement, see Xu Jilin, ‘The Fate of an Enlightenment — Twenty Years in the Chinese Intellectual Sphere (1978–1998)’, Geremie R Barmé and Gloria Davies, trans, East Asian History, n.20 (2000): 169–186. More generally, and critically, see Zhang Xudong, ed., Whither China: Intellectual Politics in Contemporary China, Durham: Duke University Press, 2001, Part I.

[3] The study of European philosophy was not a priority of the Ninth Five Year Plan on Research in the Social Sciences and Philosophy 国家哲学社会科学研究九五规划重大课题, which covered the period from 1996 to 2000, and Liu Xiaofeng’s first publication on Carl Schmitt, a review of Renato Cristi’s book Carl Schmitt and Authoritarian Liberalism, dates to 1997. See Liu Xiaofeng 刘小枫, ‘Shimite gushide youpai jiangfa: quanwei ziyouzhyi?’ 施米特故事的右派讲法: 权威自由主义? , 28 September 2005, online at: http://www.aisixiang.com/data/8911.html. On the Ninth Five Year Plan, see Guojia Zhexue Shehui Kexue Yanjiu Jiuwu (1996–2000) Guihua Bangongshi 国家哲学社会科学研究九五 (1996–2000) 规划办公室, Guojia Zhexue Shehui Kexue Yanjiu Jiuwu (1996–2000) Guihua 国家哲学社会科学研究九五 (1996–2000) 规划, Beijing 北京: Xuexi chubanshe 学习出版社, 1997.

[4] Liu Xiaofeng 刘小枫, ‘Xiandai yujing zhongde hanyu jidu shenxue’ 现代语境中的汉语基督神学, 2 April 2010, online at: http://www.aisixiang.com/data/32790.html. On Sino-Christian theology, see also Yang Huiling and Daniel HN Yeung, eds, Sino-Christian Studies in China, Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006; Pan-chiu Lai and Jason Lam, eds, Sino-Christian Theology: A Theological Qua Cultural Movement in Contemporary China, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2010; and, Alexander Chow, Theosis, Sino-Christian Theology and the Second Chinese Enlightenment: Heaven and Humanity in Unity, New York: Peter Lang, 2013. For a mainstream commentary on Chinese Schmittianism, see Mark Lilla, ‘Reading Strauss in Beijing’, The New Republic, 17 December 2010, online at: http://www.newrepublic.com/article/magazine/79747/reading-leo-strauss-in-beijing-china-marx

[5] Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty, George Schwab, trans, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005 p.36.

[6] Mao Zedong, ‘On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People’, Selected Works of Chairman Mao Tsetung, Volume 5, edited by the Committee for Editing and Publishing the Works of Chairman Mao Tsetung, Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1977, pp.348–421.

[7] For an exploration of its uses in the field of public security, see Michael Dutton, Policing Chinese Politics: A History, Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

[8] Carl Schmitt, Dictatorship: From the origin of the modern concept of sovereignty to proletarian class struggle, Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward, trans, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014.

[9] Carl Schmitt, The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy, Ellen Kennedy, trans, Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2000; and, Carl Schmitt, Constitutional Theory, Jeffrey Seitzer, trans, Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

[10] On the statist and nationalist intellectual trend, see Xu Jilin 许纪霖, ‘Jin shinianlai Zhongguo guojiazhuyi sichaozhi pipan’ 近十年来中国国家主义思潮之批判, 5 July 2011, online at: http://www.aisixiang.com/data/41945.html

[11] ‘Communiqué on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere. A Notice from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China’s General Office’, online at: http://www.chinafile.com/document-9-chinafile-translation.

[12] As, for instance, a relationship of agonism, where the Schmittian enemy becomes an adversary. In this context, see Chantal Mouffe, On the Political. London and New York: Routledge, 2005.

[13] Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, George Schwab, trans, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007, p.38.

[14] Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, pp.25–27.

[15] Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, pp.46–48.

[16] By which Wang and Hu mean: ‘the ratio between the actual degree of intervention that the state is capable of realizing and the scope of intervention that the state hopes to achieve.’ See Wang Shaoguang and Hu Angang, The Chinese Economy in Crisis: State Capacity and Tax Reform, New York: ME Sharpe, 2001, p.190.

[17] Wang Shaoguang 王绍光, Minzhu sijiang 民主四讲, Beijing 北京: Sanlian shudian 三联书店, 2008.

[18] Wang Shaoguang, ‘The Problem of State Weakness’, Journal of Democracy 14.1 (2003): 36-42. By the same author, see ‘Democracy and State Effectiveness’, in Natalia Dinello and Vladimir Popov, eds, Political Institutions and Development: failed expectations and renewal hopes, London: Edward Elgar, 2007, pp.140-167.

[19] ‘EU-China Human Rights Dialogue’, online at: http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/china/eu_china/political_relations/humain_rights_dialogue/index_en.htm

[20] Cui Zhiyuan 崔之元, ‘A Mixed Constitution and a Tri-level Analysis of Chinese Politics’ 混合宪法与对中国政治的三层分析, 25 March 2008, online at: http://www.aisixiang.com/data/18117.html

[21] Chen Ruihong 陈瑞洪, ‘A World Cup for Studies of Constitutional Law: a Dialogue between Political and Constitutional Scholars on Constitutional Power’ 宪法学的知识界碑 — 政治学者和宪法学者关于制宪权的对话, 5 October 2010, online at: http://www.aisixiang.com/data/36400.html; and, also Xianfa yu zhuquan 宪法与主权, Beijing 北京: Falü chubanshe 法律出版社, 2007.

[22] Han Yuhai 韩毓海, ‘The Constitution and the Proletarian State’ 宪政与无产阶级国家 online at: http://www.globalview.cn/ReadNews.asp?NewsID=34640.

[23] Hu Angang, China’s Collective Presidency, New York: Springer, 2014.

[24] Qiang Shigong 强世功, ‘The Unwritten Constitution in China’s Constitution’ 中国宪法中的不成文宪法, 19 June 2010, online at: http://www.aisixiang.com/data/related-34372.html.

[25] See also the special issue ‘The Basis for the Legitimacy of the Chinese Political System: Whence and Whither? Dialogues among Western and Chinese Scholars VII’, Modern China, vol.40, no.2 (March 2014).

[26] Randall Peerenboom, China’s Long March Towards the Rule of Law, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[27] Michael Dowdle, ‘Constitutional Listening’, Chicago Kent Law Review, vol.88, issue 1, (2012-2013): 115–156.

[28] Larry Catá Backer and Keren Wang, ‘The Emerging Structures of Socialist Constitutionalism with Chinese Characteristics: Extra Judicial Detention (Laojiao and Shuanggui) and the Chinese Constitutional Order’, Pacific Rim Law and Policy Journal, vol.23, no.2 (2014): 251–341.

[29] Liu Yu 刘瑜, ‘Have you read your Schmitt today?’ 你今天施密特了吗?, Caijing, 30 August 2010, online at: http://blog.caijing.com.cn/expert_article-151338-10488.shtml option=com_content&view=article&id=189:2010-10-08-21-43-05&catid=29:works&Itemid=69&lang=en

[30] He Baogang 何包钢, ‘In Defence of Procedure: a liberal’s critique of Carl Schmitt’s theory of exception’ 保卫程序 一个自由主义者对卡尔施密特例外理论的批评, 26 December 2003, online at: http://www.china-review.com/sao.asp?id=2559

[31] ‘Let no man deceive you by any means: for that day shall not come, except there come a falling away first, and that man of sin be revealed, the son of perdition; Who opposeth and exalteth himself above all that is called God, or that is worshipped; so that he as God sitteth in the temple of God, shewing himself that he is God. Remember ye not, that, when I was yet with you, I told you these things? And now ye know what withholdeth that he might be revealed in this time. For the mystery of iniquity doth already work: only he who know letteth will tell, until he be taken out of the way’. See, The Bible: New Testament, 2 Thessalonians 2: 3-8.

[32] For a simple illustration, see Gopal Balakrishnan, The Enemy: An Intellectual Portrait of Carl Schmitt, London: Verso, 2002, Chapter 17. An overview of debates about the role of the katechon and a genealogy of the concept in Carl Schmitt’s political theology can be found in Julia Hell, ‘Katechon: Carl Schmitt’s Imperial Theology and the Ruins of the Future’, The Germanic Review, vol.84, issue 4, (2009): 283-325.

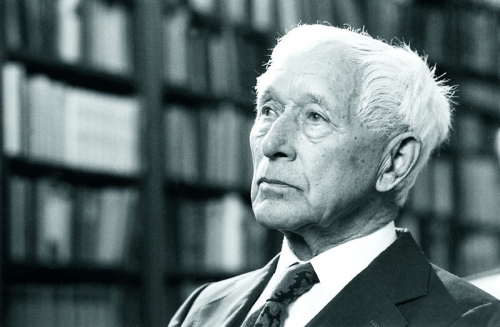

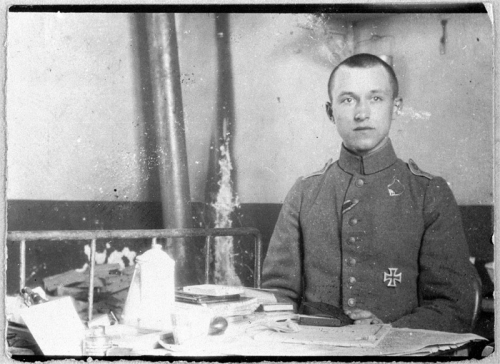

Ernst Jünger was one of the true luminaries of the intellectual Right in the 20th century. A popular hero of the First World War, famous for his memoir of the conflict entitled The Storm of Steel, he became aligned with the German conservative revolutionary movement in the interbellum years, and as such advocated a radical, authoritarian, militarist nationalism. This being said, he never made the fatal gesture Heidegger made, and was never associated with National Socialism; his relationship with Nazism began as coolly ambivalent, progressing into antipathy and finally open hostility (he was even peripherally involved with 20 July Plot to assassinate Hitler). This being said, his contribution to political theory outside his initial context was, essentially, minimal. However, he was regarded as a figure of great literary stature in post-war Europe. He was a prolific novelist, and his incredibly long lifespan (over a century) gave him an enviable vantage point to comment from: he was a grown man when the German Empire collapsed, he was present during the rise and fall of the Third Reich, and lived to see the reunification of Germany (comfortably outliving the German Democratic Republic). His fans included a variety of contradictory figures, including Hitler, Goebbels, Francois Mitterand, Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht. As well as writing, he was also a well-educated botanist and entomologist. He was even one of the very earliest experimenters with LSD. He was a man who embodied the very paradoxes and contradictions of recent European existence.

Ernst Jünger was one of the true luminaries of the intellectual Right in the 20th century. A popular hero of the First World War, famous for his memoir of the conflict entitled The Storm of Steel, he became aligned with the German conservative revolutionary movement in the interbellum years, and as such advocated a radical, authoritarian, militarist nationalism. This being said, he never made the fatal gesture Heidegger made, and was never associated with National Socialism; his relationship with Nazism began as coolly ambivalent, progressing into antipathy and finally open hostility (he was even peripherally involved with 20 July Plot to assassinate Hitler). This being said, his contribution to political theory outside his initial context was, essentially, minimal. However, he was regarded as a figure of great literary stature in post-war Europe. He was a prolific novelist, and his incredibly long lifespan (over a century) gave him an enviable vantage point to comment from: he was a grown man when the German Empire collapsed, he was present during the rise and fall of the Third Reich, and lived to see the reunification of Germany (comfortably outliving the German Democratic Republic). His fans included a variety of contradictory figures, including Hitler, Goebbels, Francois Mitterand, Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht. As well as writing, he was also a well-educated botanist and entomologist. He was even one of the very earliest experimenters with LSD. He was a man who embodied the very paradoxes and contradictions of recent European existence. This is a deeply reactionary novel, and doesn't make for easy reading. Jünger's writing meanders, straying into lengthy digressions into his narrator's memory; his pace is languid, virtually glacial in fact. Although his prose is beautiful, even poetic, it feels incredibly indulgent and is often, frankly, dull. Very little happens as such in the novel, the bulk of it simply being Richard's recollections. And yet, what is curious is how this achingly slow piece of writing is able to convey the sheer speed with which modernity did away with the old world. The narrator, like Jünger, grew up in a world were the horse was still yet to be rendered obsolete by the automobile.

This is a deeply reactionary novel, and doesn't make for easy reading. Jünger's writing meanders, straying into lengthy digressions into his narrator's memory; his pace is languid, virtually glacial in fact. Although his prose is beautiful, even poetic, it feels incredibly indulgent and is often, frankly, dull. Very little happens as such in the novel, the bulk of it simply being Richard's recollections. And yet, what is curious is how this achingly slow piece of writing is able to convey the sheer speed with which modernity did away with the old world. The narrator, like Jünger, grew up in a world were the horse was still yet to be rendered obsolete by the automobile.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

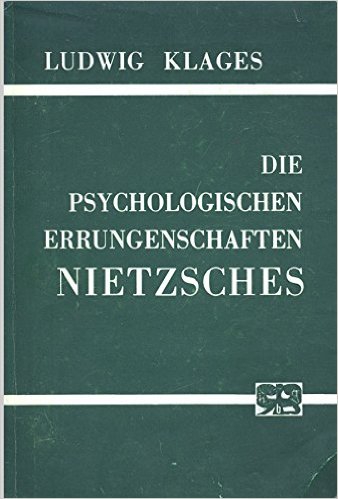

Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over.

Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over.

The hatred of the ‘West’ and of ‘Europe’ is the hatred for a Civilisation that had already reached an advanced state of decay into materialism and sought to impose its primacy by cultural subversion rather than by combat, with its City-based and money-based outlook, ‘poisoning the unborn culture in the womb of the land’. (Spengler, 1971, II, 194). Russia was still a land where there were no bourgeoisie and no true class system but only lord and peasant, a view confirmed by Berdyaev, writing:

The hatred of the ‘West’ and of ‘Europe’ is the hatred for a Civilisation that had already reached an advanced state of decay into materialism and sought to impose its primacy by cultural subversion rather than by combat, with its City-based and money-based outlook, ‘poisoning the unborn culture in the womb of the land’. (Spengler, 1971, II, 194). Russia was still a land where there were no bourgeoisie and no true class system but only lord and peasant, a view confirmed by Berdyaev, writing:  Spengler states above that the Russians do not ‘fight’ capital. (Ibid., 495). Yet their young soul brings them into conflict with money, as both oligarchy from inside and plutocracy from outside contend with the Russian soul for supremacy. It was something observed by both Gogol and Dostoyevski. The anti-capitalism and ‘world revolution’ of Stalinism took on features that were drawn more from Russian messianism than from Marxism, reflected in the struggle between Trotsky and Stalin. The revival of the Czarist and Orthodox icons, martyrs and heroes and of Russian folk-culture in conjunction with a campaign against ‘ rootless cosmopolitanism’, reflected the emergence of primal Russian soul amidst Petrine Marxism. (Brandenberger, 2002). Today the conflict between two world-views can be seen in the conflicts between Putin and certain ‘oligarchs’ and the uneasiness Putin causes among the West.

Spengler states above that the Russians do not ‘fight’ capital. (Ibid., 495). Yet their young soul brings them into conflict with money, as both oligarchy from inside and plutocracy from outside contend with the Russian soul for supremacy. It was something observed by both Gogol and Dostoyevski. The anti-capitalism and ‘world revolution’ of Stalinism took on features that were drawn more from Russian messianism than from Marxism, reflected in the struggle between Trotsky and Stalin. The revival of the Czarist and Orthodox icons, martyrs and heroes and of Russian folk-culture in conjunction with a campaign against ‘ rootless cosmopolitanism’, reflected the emergence of primal Russian soul amidst Petrine Marxism. (Brandenberger, 2002). Today the conflict between two world-views can be seen in the conflicts between Putin and certain ‘oligarchs’ and the uneasiness Putin causes among the West.

Als strenger Theist ist Vico der Ansicht, dass die Geschichte, die ihm immer eine Geschichte der „Völker und Nationen“, niemals von Individuen ist, zwar von Menschen gemacht ist, dass aber hinter den Menschen und selbst durch die Menschen hindurch unentwegt die göttliche Vorsehung wirkt. Die Selbsterkenntnisfähigkeit des menschlichen Geistes ist ein Beweis für dieses Wirken der Vorsehung, ja, sie nähert den Menschen selbst in gewisser Weise an Gott an.

Als strenger Theist ist Vico der Ansicht, dass die Geschichte, die ihm immer eine Geschichte der „Völker und Nationen“, niemals von Individuen ist, zwar von Menschen gemacht ist, dass aber hinter den Menschen und selbst durch die Menschen hindurch unentwegt die göttliche Vorsehung wirkt. Die Selbsterkenntnisfähigkeit des menschlichen Geistes ist ein Beweis für dieses Wirken der Vorsehung, ja, sie nähert den Menschen selbst in gewisser Weise an Gott an. Als tief einem in der Tradition verwurzelten Katholiken fehlte Vico jeder Begriff von „Fortschritt“. Trotzdem beinhaltet seine „Neue Wissenschaft“ eine intensive Auseinandersetzung mit dem Aufstieg und Verfall der Völker und Nationen. Nach Vico liegt der Anfang der Völker in einem dunklen Heroenzeitalter. Dies ist gekennzeichnet durch barbarische Gefühlsausbrüche und körperliche Sinnlichkeit. Doch gerade dieses unmenschliche Zeitalter der rohen Gewalt und Barbarei ist ganz im Sinn der Vorsehung, und zwar zum Besten der Menschen: sie sind der Urkeim eines wahrhaft geselligen Zustandes, der erst ein menschenwürdiges Zusammenleben möglich macht. Obwohl Vico nicht mit groben Bezeichnungen für seine barbarischen Helden spart, behandelt er diese Vorzeit mit Liebe und Verständnis, ja sogar mit Sympathie für die „Riesen und Polypheme“, wie er die Barbaren nennt. Ihr Zeitalter ist das einer unschuldigen Jugend, reichlich ausgestattet mit Phantasie und ursprünglicher Schaffenskraft.

Als tief einem in der Tradition verwurzelten Katholiken fehlte Vico jeder Begriff von „Fortschritt“. Trotzdem beinhaltet seine „Neue Wissenschaft“ eine intensive Auseinandersetzung mit dem Aufstieg und Verfall der Völker und Nationen. Nach Vico liegt der Anfang der Völker in einem dunklen Heroenzeitalter. Dies ist gekennzeichnet durch barbarische Gefühlsausbrüche und körperliche Sinnlichkeit. Doch gerade dieses unmenschliche Zeitalter der rohen Gewalt und Barbarei ist ganz im Sinn der Vorsehung, und zwar zum Besten der Menschen: sie sind der Urkeim eines wahrhaft geselligen Zustandes, der erst ein menschenwürdiges Zusammenleben möglich macht. Obwohl Vico nicht mit groben Bezeichnungen für seine barbarischen Helden spart, behandelt er diese Vorzeit mit Liebe und Verständnis, ja sogar mit Sympathie für die „Riesen und Polypheme“, wie er die Barbaren nennt. Ihr Zeitalter ist das einer unschuldigen Jugend, reichlich ausgestattet mit Phantasie und ursprünglicher Schaffenskraft.

Cuando estos días prepárabamos el excursus a la "Elucidación de la tradición", dedicado en dos entregas (

Cuando estos días prepárabamos el excursus a la "Elucidación de la tradición", dedicado en dos entregas (

Troy Southgate: Aveţi un “unghi spiritual”?

Troy Southgate: Aveţi un “unghi spiritual”?

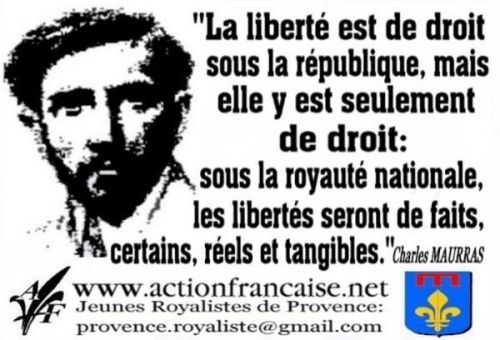

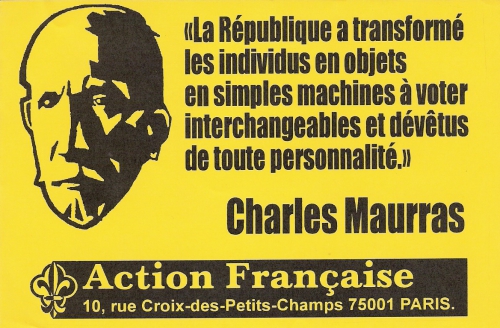

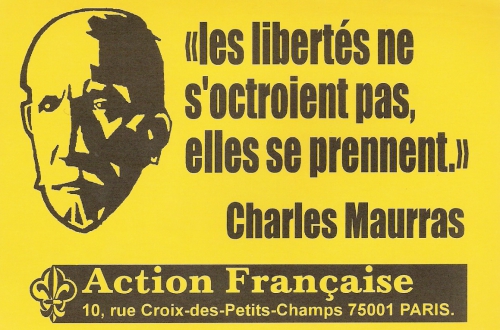

France and Algeria, of course, were joined at the hip in accordance with the Napoleonic doctrine of Algérie française. In the end, the division had to occur, but at least a million French Algerians, who were totally French of course, pieds noirs, black feet, came back from North Africa to live in the south of France where they became the bedrock for the Front National vote in the deep south of the country in generations to come.

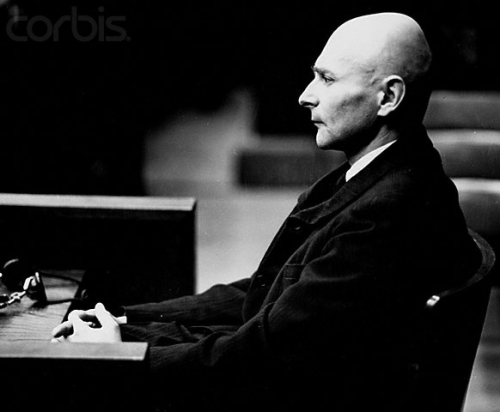

France and Algeria, of course, were joined at the hip in accordance with the Napoleonic doctrine of Algérie française. In the end, the division had to occur, but at least a million French Algerians, who were totally French of course, pieds noirs, black feet, came back from North Africa to live in the south of France where they became the bedrock for the Front National vote in the deep south of the country in generations to come. So, I think it falls upon us, as largely non-French people, to look back upon this traditionalist philosopher of the French radical Right with a degree of quiet appraisal. Maurras was a figure who could be admired as somebody who fought for his own country to the last element of his own breath. He was also somebody who’s own cultural dynamics were complicated and ingenious. To give one cogent example, the Greek play Antigone deals with the prospect of the punishment of a woman by Creon because she wishes to honor the death sacrifice of her brother. This becomes a conflict between the state and those who would seek to supplant the state’s momentary laws by laws which are regarded as matriarchal or affirmative with the chthonian or the fundamental in human life. George Steiner once commented in a book looking at the different varieties of Antigone that most critics of the Left have always supported her against Creon and most socially Right-wing commentators like T. S. Eliot have always supported Creon against Antigone. And yet Maurras supported Antigone against Creon, because she wished to bury her brother for reasons which were ancestral and chthonian and came up from under the ground and were primeval and were blood-related and were therefore more important and more profound than the laws that men had put together with pieces of parchment and bits of writing on paper.

So, I think it falls upon us, as largely non-French people, to look back upon this traditionalist philosopher of the French radical Right with a degree of quiet appraisal. Maurras was a figure who could be admired as somebody who fought for his own country to the last element of his own breath. He was also somebody who’s own cultural dynamics were complicated and ingenious. To give one cogent example, the Greek play Antigone deals with the prospect of the punishment of a woman by Creon because she wishes to honor the death sacrifice of her brother. This becomes a conflict between the state and those who would seek to supplant the state’s momentary laws by laws which are regarded as matriarchal or affirmative with the chthonian or the fundamental in human life. George Steiner once commented in a book looking at the different varieties of Antigone that most critics of the Left have always supported her against Creon and most socially Right-wing commentators like T. S. Eliot have always supported Creon against Antigone. And yet Maurras supported Antigone against Creon, because she wished to bury her brother for reasons which were ancestral and chthonian and came up from under the ground and were primeval and were blood-related and were therefore more important and more profound than the laws that men had put together with pieces of parchment and bits of writing on paper.

Ein dritter Blogbeitrag zu diesem Vordenker aus dem Mai 2012 ist bislang nie veröffentlicht worden. Er soll hiermit veröffentlicht werden. Inzwischen ist auch eine neue Biographie über Friedrich Hielscher erschienen:

Ein dritter Blogbeitrag zu diesem Vordenker aus dem Mai 2012 ist bislang nie veröffentlicht worden. Er soll hiermit veröffentlicht werden. Inzwischen ist auch eine neue Biographie über Friedrich Hielscher erschienen:

Infatti, all’interno dell’opera

Infatti, all’interno dell’opera

The volume at hand, Standardbearers, seems to have been assembled in the late 1990s to help forge a new middle-way Rightism. It was the early Tony Blair years. The Conservatives were in the wilderness, in thrall to Political Correctness, and the respectable Right had lost its way. Tony Blair had a way of dismissing his opponents’ arguments by describing them as “the past.” As Antony Flew describes in the Foreword:

The volume at hand, Standardbearers, seems to have been assembled in the late 1990s to help forge a new middle-way Rightism. It was the early Tony Blair years. The Conservatives were in the wilderness, in thrall to Political Correctness, and the respectable Right had lost its way. Tony Blair had a way of dismissing his opponents’ arguments by describing them as “the past.” As Antony Flew describes in the Foreword:

Wiewohl Sombart überhaupt den Einfluss eines säkularisierten Judentums für das Aufkommen von Kapitalismus und Sozialismus hoch anschlägt, so führt er doch nie beide kausal, d.h. schlechthin auf das Judentum zurück. Nur sei das spezifische Gepräge des modernen Kapitalismus wie des modernen Sozialismus „den Juden“ bzw. dem „jüdischen Geist“ zu verdanken, wobei Sombart übrigens letzteren – wie überhaupt alle „Volksgeister“ – von seiner leibseelischen Grundlage für ablösbar und sogar für übertragbar hält.

Wiewohl Sombart überhaupt den Einfluss eines säkularisierten Judentums für das Aufkommen von Kapitalismus und Sozialismus hoch anschlägt, so führt er doch nie beide kausal, d.h. schlechthin auf das Judentum zurück. Nur sei das spezifische Gepräge des modernen Kapitalismus wie des modernen Sozialismus „den Juden“ bzw. dem „jüdischen Geist“ zu verdanken, wobei Sombart übrigens letzteren – wie überhaupt alle „Volksgeister“ – von seiner leibseelischen Grundlage für ablösbar und sogar für übertragbar hält.

La democrazia è stata imposta all’Europa settant’anni fa con la conclusione disastrosa della seconda guerra mondiale, ma i suoi effetti deleteri hanno cominciato a diventare evidenti dopo la fine della Guerra Fredda, con la messa in atto della decisione di trasformare l’intera umanità in un’orda meticcia facilmente manovrabile dal potere dietro le quinte del sistema democratico, di recidere il legame sempre esistito e che rappresenta l’ordine normale delle cose, tra sangue e suolo.

La democrazia è stata imposta all’Europa settant’anni fa con la conclusione disastrosa della seconda guerra mondiale, ma i suoi effetti deleteri hanno cominciato a diventare evidenti dopo la fine della Guerra Fredda, con la messa in atto della decisione di trasformare l’intera umanità in un’orda meticcia facilmente manovrabile dal potere dietro le quinte del sistema democratico, di recidere il legame sempre esistito e che rappresenta l’ordine normale delle cose, tra sangue e suolo. Riguardo a Evola, è importante precisare che molti hanno voluto vedere in Evola il teorico di una dottrina spirituale della razza in contrapposizione alla visione nazionalsocialista e in particolare dell’ideologo del nazionalsocialismo, Alfred Rosenberg, che si è voluta riduttivamente interpretare come un rozzo materialismo biologico. Questa interpretazione, ci assicurano i nostri autori, è completamente falsa, riesce a stare in piedi solo se si evita e si impedisca che sia accessibile la lettura di prima mano dei testi nazionalsocialisti, e in particolare del ponderoso Mito del XX secolo di Rosenberg, secondo la prassi democratica che consiste nella censura e nell’impedire il confronto delle idee, altrimenti sarebbe chiaro che il nazionalsocialismo e Rosenberg ebbero ben chiara la dimensione spirituale connessa al “mito del sangue”.

Riguardo a Evola, è importante precisare che molti hanno voluto vedere in Evola il teorico di una dottrina spirituale della razza in contrapposizione alla visione nazionalsocialista e in particolare dell’ideologo del nazionalsocialismo, Alfred Rosenberg, che si è voluta riduttivamente interpretare come un rozzo materialismo biologico. Questa interpretazione, ci assicurano i nostri autori, è completamente falsa, riesce a stare in piedi solo se si evita e si impedisca che sia accessibile la lettura di prima mano dei testi nazionalsocialisti, e in particolare del ponderoso Mito del XX secolo di Rosenberg, secondo la prassi democratica che consiste nella censura e nell’impedire il confronto delle idee, altrimenti sarebbe chiaro che il nazionalsocialismo e Rosenberg ebbero ben chiara la dimensione spirituale connessa al “mito del sangue”.