Extrait de The Conservative Revolution (Moscou, Arktogaïa, 1994), The Russian Thing Vol. 1 (2001), et de The Philosophy of War (2004). – Article écrit en 1991, publié pour la première fois dans le journal Nash Sovremennik en 1992.

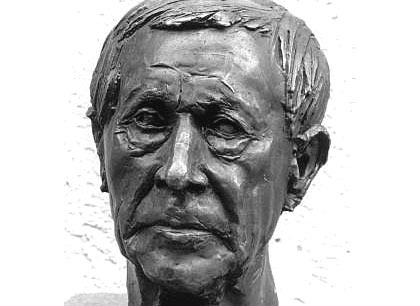

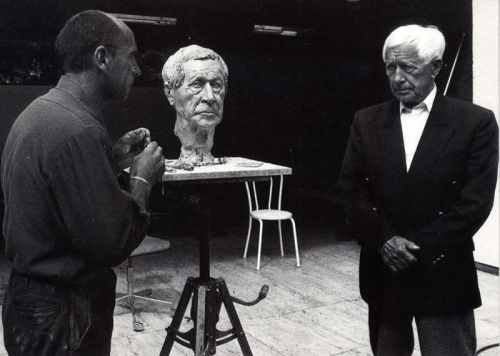

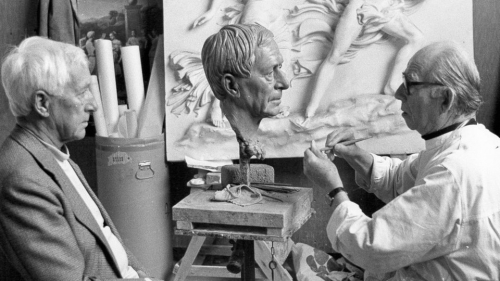

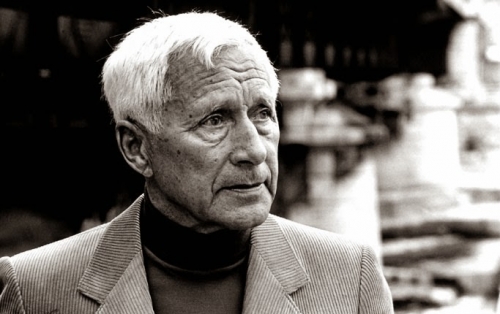

Le fameux juriste allemand Carl Schmitt est considéré comme un classique du droit moderne. Certains l’appellent le « Machiavel moderne » à cause de son absence de moralisme sentimental et de rhétorique humaniste dans son analyse de la réalité politique. Carl Schmitt pensait que, pour déterminer les questions juridiques, il faut avant tout donner une description claire et réaliste des processus politiques et sociaux et s’abstenir d’utopisme, de vœux pieux, et d’impératifs et de dogmes a priori. Aujourd’hui, l’héritage intellectuel et légal de Carl Schmitt est un élément nécessaire de l’enseignement juridique dans les universités occidentales. Pour la Russie aussi, la créativité de Schmitt est d’un intérêt et d’une importance particuliers parce qu’il s’intéressait aux situations critiques de la vie politique moderne. Indubitablement, son analyse de la loi et du contexte politique de la légalité peut nous aider à comprendre plus clairement et plus profondément ce qui se passe exactement dans notre société et en Russie.

Leçon #1 : la politique au-dessus de tout

Le principe majeur de la philosophie schmittienne de la loi était l’idée de la primauté inconditionnelle des principes politiques sur les critères de l’existence sociale. C’est la politique qui organisait et prédéterminait la stratégie des facteurs économiques internes et leur pression croissante dans le monde moderne. Schmitt explique cela de la manière suivante : « Le fait que les contradictions économiques sont maintenant devenues des contradictions politiques … ne fait que montrer que, comme toute autre activité humaine, l’économie parcourt une voie qui mène inévitablement à une expression politique » [1]. La signification de cette allégation employée par Schmitt, comprise comme un solide argument historique et sociologique, revient en fin de compte à ce qu’on pourrait définir comme une théorie de l’« idéalisme historique collectif ». Dans cette théorie, le sujet n’est pas l’individu ni les lois économiques développant la substance, mais un peuple concret, historiquement et socialement défini qui maintient, avec sa volonté dynamique particulière – dotée de sa propre loi – son existence socioéconomique, son unité qualitative, et la continuité organique et spirituelle de ses traditions sous des formes différentes et à des époques différentes. D’après Schmitt, le domaine politique représente l’incarnation de la volonté du peuple exprimée sous diverses formes reliées aux niveaux juridique, économique et sociopolitique.

Une telle définition de la politique est en opposition avec les modèles mécanistes et universalistes de la structure sociétale qui ont dominé la jurisprudence et la philosophie juridique occidentales depuis l’époque des Lumières. Le domaine politique de Schmitt est directement associé à deux facteurs que les doctrines mécanistes ont tendance à ignorer : les spécificités historiques d’un peuple doté d’une qualité particulière de volonté, et la particularité historique d’une société, d’un Etat, d’une tradition et d’un passé particuliers qui, d’après Schmitt, se concentrent dans leur manifestation politique. Ainsi, l’affirmation par Schmitt de la primauté de la politique introduisait dans la philosophie juridique et la science politique des caractéristiques qualitatives et organiques qui ne sont manifestement pas incluses dans les schémas unidimensionnels des « progressistes », qu’ils soient du genre libéral-capitaliste ou du genre marxiste-socialiste.

La théorie de Schmitt considérait donc la politique comme un phénomène « organique » enraciné dans le « sol ».

La Russie et le peuple russe ont besoin d’une telle compréhension de la politique pour bien gouverner leur propre destinée et éviter de devenir une fois de plus, comme il y a sept décennies, les otages d’une idéologie réductionniste antinationale ignorant la volonté du peuple, son passé, son unité qualitative, et la signification spirituelle de sa voie historique.

Leçon #2 : qu’il y ait toujours des ennemis ; qu’il y ait toujours des amis

Dans son livre Le concept du Politique, Carl Schmitt exprime une vérité extraordinairement importante : « Un peuple existe politiquement seulement s’il forme une communauté politique indépendante et s’oppose à d’autres communautés politiques pour préserver sa propre compréhension de sa communauté spécifique ». Bien que ce point de vue soit en désaccord complet avec la démagogie humaniste caractéristique des théories marxiste et libérale-démocratique, toute l’histoire du monde, incluant l’histoire réelle (pas l’histoire officielle) des Etats marxistes et libéraux-démocratiques, montre que ce fait se vérifie dans la pratique, même si la conscience utopique post-Lumières est incapable de le reconnaître. En réalité, la division politique entre « nous » et « eux » existe dans tous les régimes politiques et dans toutes les nations. Sans cette distinction, pas un seul Etat, pas un seul peuple et pas une seule nation ne pourraient préserver leur propre identité, suivre leur propre voie et avoir leur propre histoire.

Analysant sobrement l’affirmation démagogique de l’antihumanisme, de l’« inhumanité » d’une telle opposition, et de la division entre « nous » et « eux », Carl Schmitt note : « Si on commence à agir au nom de toute l’humanité, au nom de l’humanisme abstrait, en pratique cela signifie que cet acteur refuse toute qualité humaine à tous les adversaires possibles, se déclarant ainsi comme étant au-delà de l’humanité et au-delà de la loi, et donc menace potentiellement d’une guerre qui serait menée jusqu’aux limites les plus terrifiantes et les plus inhumaines ». D’une manière frappante, ces lignes furent écrites en 1934, longtemps avant l’invasion terroriste du Panama ou le bombardement de l’Irak par les Américains. De plus, le Goulag et ses victimes n’étaient pas encore très connus en Occident. Vu sous cet angle, ce n’est pas la reconnaissance réaliste des spécificités qualitatives de l’existence politique d’un peuple, présupposant toujours une division entre « nous » et « eux », qui conduit aux conséquences les plus terrifiantes, mais plutôt l’effort vers une universalisation totale et pour faire entrer les nations et les Etats dans les cellules des idées utopiques d’une « humanité unie et uniforme » dépourvue de toutes différences organiques ou historiques.

Commençant par ces conditions préalables, Carl Schmitt développa la théorie de la « guerre totale » et de la « guerre limitée » dénommée « guerre de forme », où la guerre totale est la conséquence de l’idéologie universaliste utopique qui nie les différences culturelles, historiques, étatiques et nationales naturelles entre les peuples. Une telle guerre représente en fait une menace de destruction pour toute l’humanité. Selon Carl Schmitt, l’humanisme extrémiste est la voie directe vers une telle guerre qui entraînerait l’implication non seulement des militaires mais aussi des populations civiles dans un conflit. Ceci est en fin de compte le danger le plus terrible. D’un autre coté, les « guerres de forme » sont inévitables du fait des différences entre les peuples et entre leurs cultures indestructibles. Les « guerres de forme » impliquent la participation de soldats professionnels, et peuvent être régulées par les règles légales définies de l’Europe qui portaient jadis le nom de Jus Publicum Europeum (Loi Commune Européenne). Par conséquent, de telles guerres représentent un moindre mal dont la reconnaissance théorique de leur inévitabilité peut protéger les peuples à l’avance contre un conflit « totalisé » et une « guerre totale ». A ce sujet, on peut citer le fameux paradoxe établi par Chigalev dans Les Possédés de Dostoïevski, qui dit : « En partant de la liberté absolue, j’arrive à l’esclavage absolu ». En paraphrasant cette vérité et en l’appliquant aux idées de Carl Schmitt, on peut dire que les partisans de l’humanisme radical « partent de la paix totale et arrivent à la guerre totale ». Après mûre réflexion, nous pouvons voir l’application de la remarque de Chigalev dans toute l’histoire soviétique. Si les avertissements de Carl Schmitt ne sont pas pris en compte, il sera beaucoup plus difficile de comprendre leur véracité, parce qu’il ne restera plus personne pour attester qu’il avait raison – il ne restera plus rien de l’humanité.

Commençant par ces conditions préalables, Carl Schmitt développa la théorie de la « guerre totale » et de la « guerre limitée » dénommée « guerre de forme », où la guerre totale est la conséquence de l’idéologie universaliste utopique qui nie les différences culturelles, historiques, étatiques et nationales naturelles entre les peuples. Une telle guerre représente en fait une menace de destruction pour toute l’humanité. Selon Carl Schmitt, l’humanisme extrémiste est la voie directe vers une telle guerre qui entraînerait l’implication non seulement des militaires mais aussi des populations civiles dans un conflit. Ceci est en fin de compte le danger le plus terrible. D’un autre coté, les « guerres de forme » sont inévitables du fait des différences entre les peuples et entre leurs cultures indestructibles. Les « guerres de forme » impliquent la participation de soldats professionnels, et peuvent être régulées par les règles légales définies de l’Europe qui portaient jadis le nom de Jus Publicum Europeum (Loi Commune Européenne). Par conséquent, de telles guerres représentent un moindre mal dont la reconnaissance théorique de leur inévitabilité peut protéger les peuples à l’avance contre un conflit « totalisé » et une « guerre totale ». A ce sujet, on peut citer le fameux paradoxe établi par Chigalev dans Les Possédés de Dostoïevski, qui dit : « En partant de la liberté absolue, j’arrive à l’esclavage absolu ». En paraphrasant cette vérité et en l’appliquant aux idées de Carl Schmitt, on peut dire que les partisans de l’humanisme radical « partent de la paix totale et arrivent à la guerre totale ». Après mûre réflexion, nous pouvons voir l’application de la remarque de Chigalev dans toute l’histoire soviétique. Si les avertissements de Carl Schmitt ne sont pas pris en compte, il sera beaucoup plus difficile de comprendre leur véracité, parce qu’il ne restera plus personne pour attester qu’il avait raison – il ne restera plus rien de l’humanité.

Passons maintenant au stade final de la distinction entre « nous » et « eux », celui des « ennemis » et des « amis ». Schmitt pensait que la centralité de cette paire est valable pour l’existence politique d’une nation, puisque c’est par ce choix que se décide un profond problème existentiel. Julien Freud, un disciple de Schmitt, formula cette thèse de la manière suivante : « La dualité ennemi-ami donne à la politique une dimension existentielle puisque la possibilité théoriquement impliquée de la guerre soulève le problème et le choix de la vie et de la mort dans ce cadre » [2].

Le juriste et le politicien, jugeant en termes d’« ennemi » et d’« ami » avec une claire conscience de la signification de ce choix, opèrent ainsi avec les mêmes catégories existentielles qui donnent aux décisions, aux actions et aux déclarations les qualités de réalité, de responsabilité et de sérieux dont manquent toutes les abstractions humanistes, transformant ainsi le drame de la vie et de la mort en une guerre dans un décor chimérique à une seule dimension. Une terrible illustration de cette guerre fut la couverture du conflit irakien par les médias occidentaux. Les Américains suivirent la mort des femmes, des enfants et des vieillards irakiens à la télévision comme s’ils regardaient des jeux vidéo du genre Guerre des Etoiles. Les idées du Nouvel Ordre Mondial, dont les fondements furent posés durant cette guerre, sont les manifestations suprêmes de la nature terrible et dramatique des événements lorsqu’ils sont privés de tout contenu existentiel.

La paire « ennemi »/« ami » est une nécessité à la fois externe et interne pour l’existence d’une société politiquement complète, et devrait être froidement acceptée et consciente. Sinon, tout le monde peut devenir un « ennemi » et personne n’est un « ami ». Tel est l’impératif politique de l’histoire.

Leçon #3 : La politique des «circonstances exceptionnelles» et la Décision

L’un des plus brillants aspects des idées de Carl Schmitt était le principe des « circonstances exceptionnelles » (Ernstfall en allemand, littéralement « cas d’urgence ») élevé au rang d’une catégorie politico-juridique. D’après Schmitt, les normes juridiques décrivent seulement une réalité sociopolitique normale s’écoulant uniformément et continuellement, sans interruptions. C’est seulement dans de telles situations purement normales que le concept de la « loi » telle qu’elle est comprise par les juristes s’applique pleinement. Il existe bien sûr des règlementations pour les « situations exceptionnelles », mais ces réglementations sont le plus souvent déterminées sur la base de critères dérivés d’une situation politique normale. La jurisprudence, d’après Schmitt, tend à absolutiser les critères d’une situation normale lorsqu’on considère l’histoire de la société comme un processus uniforme légalement constitué. L’expression la plus complète de ce point de vue est la « pure théorie de la loi » de Kelsen. Carl Schmitt, cependant, voit cette absolutisation d’une « approche légale » et du « règne de la loi » [= « Etat de droit »] comme un mécanisme tout aussi utopique et comme un universalisme naïf produit par les Lumières avec ses mythes rationalistes. Derrière l’absolutisation de la loi se dissimule une tentative de « mettre fin à l’histoire » et de la priver de son motif passionné créatif, de son contenu politique, et de ses peuples historiques. Sur la base de cette analyse, Carl Schmitt postule une théorie particulière des « circonstances exceptionnelles » ou Ernstfall.

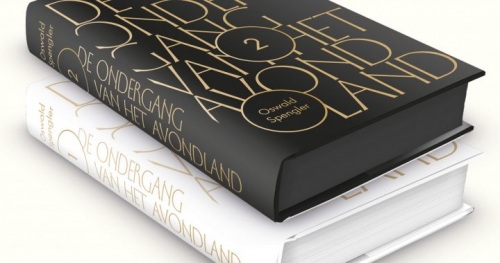

L’Ernstfall est le moment où une décision politique est prise dans une situation qui ne peut plus être régulée par des normes légales conventionnelles. La prise de décision dans des circonstances exceptionnelles implique la convergence d’un certain nombre de facteurs organiques divers reliés à la tradition, au passé historique, aux constantes culturelles, ainsi qu’aux expressions spontanées, aux efforts héroïques, aux impulsions passionnées, et à la manifestation soudaine des énergies existentielles profondes. La Vraie Décision (le terme même de « décision » était un concept clé de la doctrine légale de Schmitt) est prise précisément dans une circonstance où les normes légales et sociales sont « interrompues » et où celles qui décrivent le cours naturel des processus politiques et qui commencent à agir dans le cas d’une « situation d’urgence » ou d’une « catastrophe sociopolitique » ne sont plus applicables. « Circonstances exceptionnelles » ne signifie pas seulement une catastrophe, mais le positionnement d’un peuple et de son organisme politique devant un problème, faisant appel à l’essence historique d’un peuple, à son noyau, et à sa nature secrète qui fait de ce peuple ce qu’il est. Par conséquent, la Décision politiquement prise dans une telle situation est une expression spontanée de la volonté profonde du peuple répondant à un défi global, existentiel ou historique (ici on peut comparer les vues de Schmitt à celles de Spengler, Toynbee et d’autres révolutionnaires-conservateurs avec lesquels Carl Schmitt avait des liens personnels).

Dans l’école juridique française, les adeptes de Carl Schmitt ont développé le terme spécial de « décisionnisme », à partir du mot français décision (allemand Entscheidung). Le décisionnisme met l’accent sur les « circonstances exceptionnelles », puisque c’est dans ce cas que la nation ou le peuple actualise son passé et détermine son avenir dans une dramatique concentration du moment présent où trois caractéristiques qualitatives du temps fusionnent, à savoir le pouvoir de la source d’où est issu ce peuple dans l’histoire, la volonté du peuple de faire face à l’avenir et d’affirmer le moment précis où le « Moi » éternel est révélé et où le peuple prend entièrement la responsabilité dans ses mains, et l’identité elle-même.

En développant sa théorie de l’Ernstfall et de l’Entscheidung, Carl Schmitt montra aussi que l’affirmation de toutes les normes juridiques et sociales survient précisément durant de telles périodes de « circonstances exceptionnelles » et qu’elle est primordialement basée sur une décision à la fois spontanée et prédéterminée. Le moment intermittent de l’expression singulière de la volonté porte plus tard sur la base des normes constantes qui existent jusqu’à l’émergence de nouvelles « circonstances exceptionnelles ». Cela illustre en fait parfaitement la contradiction inhérente aux idées des partisans radicaux du « règne de la loi » : ils ignorent consciemment ou inconsciemment le fait que l’appel à la nécessité d’établir le « règne de la loi » est lui-même une décision basée précisément sur la volonté politique d’un groupe donné. En un sens, cet impératif est avancé arbitrairement et pas comme une sorte de nécessité fatale et inévitable. Par conséquent, l’acceptation ou le refus du « règne de la loi » et en général l’acceptation ou le refus de tel ou tel modèle légal doit coïncider avec la volonté du peuple ou de l’Etat particulier auquel est adressée la proposition ou l’expression de volonté. Les partisans du « règne de la loi » tentent implicitement de créer ou d’utiliser les « circonstances exceptionnelles » pour mettre en œuvre leur concept, mais le caractère insidieux d’une telle approche et l’hypocrisie et l’incohérence de cette méthode peuvent tout naturellement provoquer une réaction populaire, dont le résultat pourrait très bien apparaître comme une autre décision alternative. De plus, il est d’autant plus probable que cette décision conduirait à l’établissement d’une réalité légale différente de celle recherchée par les universalistes.

Le concept de la Décision au sens supra-légal ainsi que la nature même de la Décision elle-même s’accordent avec la théorie du « pouvoir direct » et du « pouvoir indirect » (potestas directa et potestas indirecta). Dans le contexte spécifique de Schmitt, la Décision est prise non seulement dans les instances du « pouvoir direct » (le pouvoir des rois, des empereurs, des présidents, etc.) mais aussi dans les conditions du « pouvoir indirect », dont des exemples peuvent être les organisations religieuses, culturelles ou idéologiques qui influencent l’histoire d’un peuple et d’un Etat, certes pas aussi clairement que les décisions des gouvernants mais qui opèrent néanmoins d’une manière beaucoup plus profonde et formidable. Schmitt pense donc que le « pouvoir indirect » n’est pas toujours négatif, mais d’un autre coté il ne fait qu’une allusion implicite au fait qu’une décision contraire à la volonté du peuple est le plus souvent adoptée et mise en œuvre par de tels moyens de « pouvoir indirect ». Dans son livre Théologie politique et dans sa suite Théologie politique II, il examine la logique du fonctionnement de ces deux types d’autorité dans les Etats et les nations.

Le concept de la Décision au sens supra-légal ainsi que la nature même de la Décision elle-même s’accordent avec la théorie du « pouvoir direct » et du « pouvoir indirect » (potestas directa et potestas indirecta). Dans le contexte spécifique de Schmitt, la Décision est prise non seulement dans les instances du « pouvoir direct » (le pouvoir des rois, des empereurs, des présidents, etc.) mais aussi dans les conditions du « pouvoir indirect », dont des exemples peuvent être les organisations religieuses, culturelles ou idéologiques qui influencent l’histoire d’un peuple et d’un Etat, certes pas aussi clairement que les décisions des gouvernants mais qui opèrent néanmoins d’une manière beaucoup plus profonde et formidable. Schmitt pense donc que le « pouvoir indirect » n’est pas toujours négatif, mais d’un autre coté il ne fait qu’une allusion implicite au fait qu’une décision contraire à la volonté du peuple est le plus souvent adoptée et mise en œuvre par de tels moyens de « pouvoir indirect ». Dans son livre Théologie politique et dans sa suite Théologie politique II, il examine la logique du fonctionnement de ces deux types d’autorité dans les Etats et les nations.

La théorie des « circonstances exceptionnelles » et le thème de la Décision (Entscheidung) associé à cette théorie sont d’une importance capitale pour nous aujourd’hui, puisque c’est précisément à un tel moment dans l’histoire de notre peuple et de notre Etat que nous nous trouvons, et les « circonstances exceptionnelles » sont devenues l’état naturel de la nation – et non seulement l’avenir politique de notre peuple mais aussi la compréhension et la confirmation essentielle de notre passé dépendent maintenant de la Décision. Si la volonté du peuple s’affirme et que le choix national du peuple dans ce moment dramatique peut clairement définir qui est « nous » et « eux », identifier les amis et les ennemis, et arracher une auto-affirmation politique à l’histoire, alors la Décision de l’Etat russe et du peuple russe sera sa propre décision existentielle historique qui placera un sceau de loyauté sur des millénaires de « construction du peuple » et de « construction de l’empire ». Cela signifie que notre avenir sera russe. Si d’autres prennent la décision, à savoir les partisans de l’« approche humaine commune », de l’« universalisme » et de l’« égalitarisme », qui depuis la mort du marxisme représentent les seuls héritiers directs de l’idéologie utopique et mécaniste des Lumières, alors non seulement le futur ne sera pas russe mais il sera « seulement humain » et donc il n’y aura « pas de futur » (du point de vue de l’être du peuple, de l’Etat et de la nation). Notre passé perdra tout son sens et les drames de la grande histoire russe se transformeront en une farce stupide sur la voie du mondialisme et du nivellement culturel complet au profit d’une « humanité universelle », c’est-à-dire l’« enfer de la réalité légale absolue ».

Leçon #4 : Les impératifs d’un Grand Espace

Carl Schmitt s’intéressa aussi à l’aspect géopolitique des questions sociales. La plus importante de ses idées dans ce domaine est la notion de « Grand Espace » (Grossraum) qui attira plus tard l’attention de nombreux économistes, juristes, géopoliticiens et stratèges européens. La signification conceptuelle du « Grand Espace » dans la perspective analytique de Carl Schmitt se trouve dans la délimitation des régions géographiques à l’intérieur desquelles les variantes de la manifestation politique des peuples et des Etats spécifiques inclus dans cette région peuvent être conjointes pour accomplir une généralisation harmonieuse et cohérente exprimée dans une « Grande Union Géopolitique ». Le point de départ de Schmitt était la question de la Doctrine Monroe américaine impliquant l’intégration économique et stratégique des puissances américaines dans les limites naturelles du Nouveau Monde. Etant donné que l’Eurasie représente un conglomérat beaucoup plus divers d’ethnies, d’Etats et de cultures, Schmitt postulait qu’il fallait donc parler non tant de l’intégration continentale totale que de l’établissement de plusieurs grandes entités géopolitiques, chacune devant être gouvernée par un super-Etat flexible. Ceci est assez analogue au Jus Publicum Europeaum ou à la Sainte Alliance proposée à l’Europe par l’empereur russe Alexandre 1er.

D’après Carl Schmitt, un « Grand Espace » organisé en une structure politique flexible de type impérial et fédéral équilibrerait les diverses volontés nationales, ethniques et étatiques et jouerait le rôle d’une sorte d’arbitre impartial ou de régulateur des conflits locaux possibles, les « guerres de forme ». Schmitt soulignait que les « Grands Espaces », pour pouvoir être des formations organiques et naturelles, doivent nécessairement représenter des territoires terrestres, c’est-à-dire des entités tellurocratiques, des masses continentales. Dans son fameux livre Le Nomos de la Terre, il traça l’histoire de macro-entités politiques continentales, la voie de leur intégration, et la logique de leur établissement graduel en tant qu’empires. Carl Schmitt remarquait que parallèlement à l’existence de constantes spirituelles dans le destin d’un peuple, c’est-à-dire des constantes incarnant l’essence spirituelle d’un peuple, il existait aussi des constantes géopolitiques des « Grands Espaces » qui gravitent vers une nouvelle restauration avec des intervalles de plusieurs siècles ou même de millénaires. Dans ce sens, les macro-entités géopolitiques sont stables quand leur principe intégrateur n’est pas rigide ni recréé abstraitement, mais flexible, organique, et en accord avec la Décision des peuples, avec leur volonté, et avec leur énergie passionnée capable de les impliquer dans un bloc tellurocratique unifié avec leurs voisins culturels, géopolitiques ou étatiques.

La doctrine des « Grands Espaces » (Grossraum) fut établie par Carl Schmitt non seulement comme une analyse des tendances historiques dans l’histoire du continent, mais aussi comme un projet pour l’unification future que Schmitt considérait non seulement comme possible, mais désirable et même nécessaire en un certain sens. Julien Freund résuma les idées de Schmitt sur le futur Grossraum dans les termes suivants : « L’organisation de ce nouvel espace ne requerra aucune compétence scientifique, ni de préparation culturelle ou technique dans la mesure où elle surgira en résultat d’une volonté politique, dont l’ethos transforme l’apparence de la loi internationale. Dès que ce ‘Grand Espace’ sera unifié, la chose la plus importante sera la force de son ‘rayonnement’ » [3].

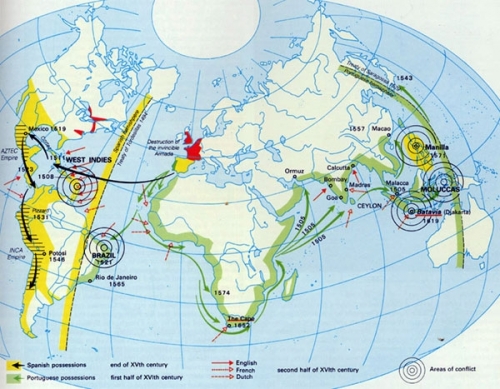

Ainsi, l’idée schmittienne du « Grand Espace » possède aussi une dimension spontanée, existentielle et volitionnelle, tout comme le sujet fondamental de l’histoire selon lui, c’est-à-dire le peuple en tant qu’unité politique. Tout comme les géopoliticiens Mackinder et Kjellen, Schmitt opposait les empires thalassocratiques (la Phénicie, l’Angleterre, les Etats-Unis, etc.) aux empires tellurocratiques (l’empire romain, l’empire austro-hongrois, l’empire russe, etc.). Dans cette perspective, l’organisation harmonieuse et organique d’un espace n’est possible que pour les empires tellurocratiques, et la Loi Continentale ne peut être appliquée qu’à eux. La thalassocratie, sortant des limites de son Ile et initiant une expansion navale, entre en conflit avec les tellurocraties et, en accord avec la logique géopolitique, commence à miner diplomatiquement, économiquement et militairement les fondements des « Grands Espaces » continentaux. Ainsi, dans la perspective des « Grands Espaces » continentaux, Schmitt revient une fois de plus aux concepts des paires ennemis/amis et nous/eux, mais cette fois-ci à un niveau planétaire. La volonté des empires continentaux, les « Grands Espaces », se révèle dans la confrontation entre les macro-intérêts continentaux et les macro-intérêts maritimes. La « Mer » défie ainsi la « Terre », et en répondant à ce défi, la « Terre » revient le plus souvent à sa conscience de soi continentale profonde.

Ainsi, l’idée schmittienne du « Grand Espace » possède aussi une dimension spontanée, existentielle et volitionnelle, tout comme le sujet fondamental de l’histoire selon lui, c’est-à-dire le peuple en tant qu’unité politique. Tout comme les géopoliticiens Mackinder et Kjellen, Schmitt opposait les empires thalassocratiques (la Phénicie, l’Angleterre, les Etats-Unis, etc.) aux empires tellurocratiques (l’empire romain, l’empire austro-hongrois, l’empire russe, etc.). Dans cette perspective, l’organisation harmonieuse et organique d’un espace n’est possible que pour les empires tellurocratiques, et la Loi Continentale ne peut être appliquée qu’à eux. La thalassocratie, sortant des limites de son Ile et initiant une expansion navale, entre en conflit avec les tellurocraties et, en accord avec la logique géopolitique, commence à miner diplomatiquement, économiquement et militairement les fondements des « Grands Espaces » continentaux. Ainsi, dans la perspective des « Grands Espaces » continentaux, Schmitt revient une fois de plus aux concepts des paires ennemis/amis et nous/eux, mais cette fois-ci à un niveau planétaire. La volonté des empires continentaux, les « Grands Espaces », se révèle dans la confrontation entre les macro-intérêts continentaux et les macro-intérêts maritimes. La « Mer » défie ainsi la « Terre », et en répondant à ce défi, la « Terre » revient le plus souvent à sa conscience de soi continentale profonde.

Comme remarque additionnelle, nous illustrerons la théorie du Grossraum avec deux exemples. A la fin du XVIIIe siècle et au début du XIXe, le territoire américain était divisé entre plusieurs pays du Vieux Monde. Le Far West, la Louisiane appartenaient aux Espagnols et plus tard aux Français ; le Sud appartenait au Mexique ; le Nord à l’Angleterre, etc. Dans cette situation, l’Europe représentait une puissance tellurocratique pour les Américains, empêchant l’unification géopolitique et stratégique du Nouveau Monde sur les plans militaire, économique et diplomatique. Après que les Américains aient obtenu l’indépendance, ils commencèrent graduellement à imposer de plus en plus agressivement leur volonté géopolitique au Vieux Monde, ce qui conduisit logiquement à l’affaiblissement de l’unité continentale du « Grand Espace » européen. Par conséquent, dans l’histoire géopolitique des « Grands Espaces », il n’y a pas de puissances absolument tellurocratiques ou absolument thalassocratiques. Les rôles peuvent changer, mais la logique continentale demeure constante.

En résumant la théorie schmittienne des « Grands Espaces » et en l’appliquant à la situation de la Russie d’aujourd’hui, nous pouvons dire que la séparation et la désintégration du « Grand Espace » autrefois nommé URSS contredit la logique continentale de l’Eurasie, puisque les peuples habitant nos terres ont perdu l’opportunité de faire appel à l’arbitrage de la superpuissance [soviétique] capable de réguler ou d’empêcher les conflits potentiels et réels. Mais d’un autre coté, le rejet de la démagogie marxiste excessivement rigide et inflexible au niveau de l’idéologie d’Etat peut conduire et conduira à une restauration spontanée et passionnée du Bloc Eurasien Oriental, puisqu’une telle reconstruction est en accord avec toutes les ethnies indigènes organiques de l’espace impérial russe. De plus, il est très probable que la restauration d’un Empire Fédéral, d’un « Grand Espace » englobant la partie orientale du continent, entraînerait au moyen de son « rayonnement de puissance » l’adhésion de ces territoires additionnels qui sont en train de perdre rapidement leur identité ethnique et étatique dans la situation géopolitique critique et artificielle prévalant depuis l’effondrement de l’URSS. D’autre part, la pensée continentale du génial juriste allemand nous permet de distinguer entre « nous » et « eux » au niveau continental.

La conscience de la confrontation naturelle et dans une certaine mesure inévitable entre les puissances tellurocratiques et thalassocratiques offre aux partisans et aux créateurs d’un nouveau Grand Espace une compréhension claire de l’« ennemi » auquel font face l’Europe, la Russie et l’Asie, c’est-à-dire les Etats-Unis d’Amérique avec leur alliée insulaire thalassocratique, l’Angleterre. En quittant le macro-niveau planétaire et en revenant au niveau de la structure sociale de l’Etat russe, il s’ensuit donc que la question devrait être posée : un lobby thalassocratique caché ne se trouve-t-il pas derrière le désir d’influencer la Décision russe des problèmes dans un sens « universaliste » qui peut exercer son influence par un pouvoir à la fois « direct » et « indirect » ?

Leçon #5 : La « paix militante » et la téléologie du Partisan

A la fin de sa vie (il mourut le 7 avril 1985), Carl Schmitt accorda une attention particulière à la possibilité d’une issue négative de l’histoire. Cette issue négative de l’histoire est en effet tout à fait possible si les doctrines irréalistes des humanistes radicaux, des universalistes, des utopistes et des partisans des « valeurs communes universelles », centrées sur le gigantesque potentiel symbolique de la puissance thalassocratique que sont les USA, parviennent à une domination globale et deviennent le fondement idéologique d’une nouvelle dictature mondiale – la dictature d’une « utopie mécaniste ». Schmitt pensait que le cours de l’histoire moderne se dirigeait inévitablement vers ce qu’il nommait la « guerre totale ».

Selon Schmitt, la logique de la « totalisation » des relations planétaires au niveau stratégique, militaire et diplomatique se base sur les points-clés suivants. A partir d’un certain moment de l’histoire, ou plus précisément à l'époque de la Révolution française et de l’Indépendance des Etats-Unis d’Amérique, commença un éloignement fatal vis-à-vis des constantes historiques, juridiques, nationales et géopolitiques qui garantissaient auparavant l'harmonie organique sur la planète et qui servaient le « Nomos de la Terre ».

Sur le plan juridique, un concept quantitatif artificiel et atomique, celui des « droits individuels » (qui devint plus tard la fameuse théorie des « droits de l'homme »), commença à se développer et remplaça le concept organique des « droits des peuples », des « droits de l’Etat », etc. Selon Schmitt, l’élévation de l’individu et du facteur individuel isolé de sa nation, de sa tradition, de sa culture, de sa profession, de sa famille, etc., au niveau d’une catégorie juridique autonome signifie le début du « déclin de la loi » et sa transformation en une chimère égalitaire utopique, s’opposant aux lois organiques de l’histoire des peuples et des Etats, des régimes, des territoires et des unions.

Au niveau national, les principes organiques impériaux et fédéraux ont fini par être remplacés par deux conceptions opposées mais tout aussi artificielles : l’idée jacobine de l’« Etat-nation » et la théorie communiste de la disparition complète de l’Etat et du début de l'internationalisme total. Les empires qui avaient préservé des vestiges de structures organiques traditionnelles, comme l’Autriche-Hongrie, l’empire ottoman, l’empire russe, etc., furent rapidement détruits sous l’influence de facteurs externes aussi bien qu’internes. Enfin, au niveau géopolitique, le facteur thalassocratique s’intensifia à un tel degré qu’une profonde déstabilisation des relations juridiques entre les « Grands Espaces » eut lieu. Notons que Schmitt considérait la « Mer » comme un espace beaucoup plus difficile à délimiter et à ordonner juridiquement que celui de la « Terre ».

La diffusion mondiale de la dysharmonie juridique et géopolitique fut accompagnée par la déviation progressive des conceptions politico-idéologiques dominantes vis-à-vis de la réalité, et par le fait qu’elles devinrent de plus en plus chimériques, illusoires et en fin de compte hypocrites. Plus on parlait de « monde universel », plus les guerres et les conflits devenaient terribles. Plus les slogans devenaient « humains », plus la réalité sociale devenait inhumaine. C’est ce processus que Carl Schmitt nomma le début de la « paix militante », c’est-à-dire un état où il n’y a plus ni guerre ni paix au sens traditionnel. Aujourd’hui la « totalisation » menaçante contre laquelle Carl Schmitt nous avait mis en garde a fini par prendre le nom de « mondialisme ». La « paix militante » a reçu son expression complète dans la théorie du Nouvel Ordre Mondial américain qui dans son mouvement vers la « paix totale » conduit clairement la planète vers une nouvelle « guerre totale ».

Carl Schmitt pensait que la conquête de l’espace était le plus important événement géopolitique symbolisant un degré supplémentaire d’éloignement vis-à-vis de la mise en ordre légitime de l’espace, puisque le cosmos est encore plus difficilement « organisable » que l’espace maritime. Schmitt pensait que le développement de l’aviation était aussi un pas de plus vers la « totalisation » de la guerre, l’exploration spatiale étant le début du processus de la « totalisation » illégitime finale.

Parallèlement à l’évolution fatale de la planète vers une telle monstruosité maritime, aérienne et même spatiale, Carl Schmitt, qui s’intéressait toujours à des catégories plus globales (dont la plus petite était « l’unité politique du peuple »), en vint à être attiré par une nouvelle figure dans l’histoire, la figure du « Partisan ». Carl Schmitt y consacra son dernier livre, La théorie du Partisan. Schmitt vit dans ce petit combattant contre des forces bien plus puissantes une sorte de symbole de la dernière résistance de la tellurocratie et de ses derniers défenseurs.

Le partisan est indubitablement une figure moderne. Comme d’autres types politiques modernes, il est séparé de la tradition et il vit en-dehors du Jus Publicum. Dans son combat, le Partisan brise toutes les règles de la guerre. Il n’est pas un soldat, mais un civil utilisant des méthodes terroristes qui, en-dehors du temps de guerre, seraient assimilées à des actes criminels gravissimes apparentés au terrorisme. Cependant, d’après Schmitt, c’est le Partisan qui incarne la « fidélité à la Terre ». Le Partisan est, pour le dire simplement, une réponse légitime au défi illégitime masqué de la « loi » moderne.

Le caractère extraordinaire de la situation et l’intensification constante de la « paix militante » (ou « guerre pacifiste », ce qui revient au même) inspirent le petit défenseur du sol, de l’histoire, du peuple et de la nation, et constituent la source de sa justification paradoxale. L’efficacité stratégique du Partisan et de ses méthodes est, d’après Schmitt, la compensation paradoxale du début de la « guerre totale » contre un « ennemi total ». C’est peut-être cette leçon de Carl Schmitt, qui s’inspirait lui-même beaucoup de l’histoire russe, de la stratégie militaire russe, et de la doctrine politique russe, incluant des analyses des œuvres de Lénine et Staline, qui est la plus intimement compréhensible pour les Russes. Le Partisan est un personnage intégral de l’histoire russe, qui apparaît toujours quand la volonté du pouvoir russe et la volonté profonde du peuple russe lui-même prennent des directions divergentes.

Dans l’histoire russe, les troubles et la guerre de partisans ont toujours eu un caractère compensatoire purement politique, visant à corriger le cours de l’histoire nationale quand le pouvoir politique se sépare du peuple. En Russie, les partisans gagnèrent les guerres que le gouvernement perdait, renversèrent les systèmes économiques étrangers à la tradition russe, et corrigèrent les erreurs géopolitiques de ses dirigeants. Les Russes ont toujours su déceler le moment où l’illégitimité ou l’injustice organique s’incarne dans une doctrine s’exprimant à travers tel ou tel personnage. En un sens, la Russie est un gigantesque Empire Partisan, agissant en-dehors de la loi et conduit par la grande intuition de la Terre, du Continent, ce « Grand, très Grand Espace » qui est le territoire historique de notre peuple.

Et à présent, alors que le gouffre entre la volonté de la nation et la volonté de l’establishment en Russie (qui représente exclusivement « le règne de la loi » en accord avec le modèle universaliste) s’élargit dangereusement et que le vent de la thalassocratie impose de plus en plus la « paix militante » dans le pays et devient graduellement une forme de « guerre totale », c’est peut être cette figure du Partisan russe qui nous montrera la voie de l’Avenir Russe au moyen d’une forme extrême de résistance, par la transgression des limites artificielles et des normes légales qui ne sont pas en accord avec les canons véritables de la Loi Russe.

Une assimilation plus complète de la cinquième leçon de Carl Schmitt signifie l’application de la Pratique Sacrée de la défense de la Terre.

Remarques finales

Enfin, la sixième leçon non formulée de Carl Schmitt pourrait être un exemple de ce que la figure de la Nouvelle Droite européenne, Alain de Benoist, nommait l’« imagination politique » ou la « créativité idéologique ». Le génie du juriste allemand réside dans le fait que non seulement il sentit les « lignes de force » de l’histoire mais aussi qu’il entendit la voix mystérieuse du monde des essences, même si celui-ci est souvent caché sous les phénomènes vides et fades du monde moderne complexe et dynamique. Nous les Russes devrions prendre exemple sur la rigueur germanique et transformer nos institutions lourdaudes et surévaluées en formules intellectuelles claires, en projets idéologiques clairs, et en théories convaincantes et impérieuses.

Aujourd’hui, c’est d’autant plus nécessaire que nous vivons dans des « circonstances exceptionnelles », au seuil d’une Décision si importante que notre nation n’en a peut-être jamais connue de telle auparavant. La vraie élite nationale n’a pas le droit de laisser son peuple sans une idéologie qui doit exprimer non seulement ce qu’il ressent et pense, mais aussi ce qu’il ne ressent pas et ne pense pas, et même ce qu’il a nourri secrètement en lui-même et pieusement vénéré pendant des millénaires.

Si nous n’armons pas idéologiquement l’Etat, un Etat que nos adversaires pourraient temporairement nous arracher, alors nous devons forcément et sans faille armer idéologiquement le Partisan Russe qui se réveille aujourd’hui pour accomplir sa mission continentale dans ce que sont maintenant les Riga et Vilnius en cours d’« anglicisation », le Caucase en train de s’« obscurcir », l’Asie Centrale en train de « jaunir », l’Ukraine en train de se « poloniser », et la Tatarie « aux yeux noirs ».

La Russie est un Grand Espace dont la Grande Idée est portée par son peuple sur son gigantesque sol eurasien continental. Si un génie allemand sert notre Réveil, alors les Teutons auront mérité une place privilégiée parmi les « amis de la Grande Russie » et deviendront « les nôtres », ils deviendront des « Asiates », des « Huns » et des « Scythes » comme nous, des autochtones de la Grande Forêt et des Grandes Steppes.

Notes

[1] Carl Schmitt, Der Begriff des Politischen, p. 127

[2] Julien Freund, « Les lignes de force de la pensée politique de Carl Schmitt », Nouvelle Ecole No. 44.

[3] Ibid.

Jünger constata que la tendencia a la estatización (a la “organización”) se hace más rara a medida que ascendemos en la escala de los animales superiores. En ellos –por ejemplo, en los lobos, en numerosos grupos de aves, etc.- es frecuente hallar ejemplos de socialización, pero muy rara vez asistiremos a los sacrificios que la estatización impone a los insectos. En ese sentido, el hombre ocupa un lugar especial: la estatización no es algo que le sea natural, aunque el proceso de desarrollo de la civilización técnica muestre claras tendencias estatizadoras. En el mundo natural, la tendencia hacia la organización es un rasgo específico de los animales sociales; en el caso de la especie humana, es el síntoma más evidente del avance del proceso de civilización. Y sin embargo, la tendencia a la organización no es inapelable, inevitable; ni siquiera natural. Ese es el sentido de la pregunta que Jünger se formula: ¿Acaso el mundo está lleno de organismos que esperan ser organizados y reivindican tal organización? No, e incluso lo contrario es lo cierto, pues por todas partes puede percibirse como actúa “la tentativa de sustraerse al poder”. De manera que la organización no es un hecho natural, o al menos no lo es más que la resistencia a la organización.

Jünger constata que la tendencia a la estatización (a la “organización”) se hace más rara a medida que ascendemos en la escala de los animales superiores. En ellos –por ejemplo, en los lobos, en numerosos grupos de aves, etc.- es frecuente hallar ejemplos de socialización, pero muy rara vez asistiremos a los sacrificios que la estatización impone a los insectos. En ese sentido, el hombre ocupa un lugar especial: la estatización no es algo que le sea natural, aunque el proceso de desarrollo de la civilización técnica muestre claras tendencias estatizadoras. En el mundo natural, la tendencia hacia la organización es un rasgo específico de los animales sociales; en el caso de la especie humana, es el síntoma más evidente del avance del proceso de civilización. Y sin embargo, la tendencia a la organización no es inapelable, inevitable; ni siquiera natural. Ese es el sentido de la pregunta que Jünger se formula: ¿Acaso el mundo está lleno de organismos que esperan ser organizados y reivindican tal organización? No, e incluso lo contrario es lo cierto, pues por todas partes puede percibirse como actúa “la tentativa de sustraerse al poder”. De manera que la organización no es un hecho natural, o al menos no lo es más que la resistencia a la organización.

Biographisches Rohmaterial

Biographisches Rohmaterial

Ernst Jüngers Rhodos-Reisen von 1938, 1964 und 1981

Ernst Jüngers Rhodos-Reisen von 1938, 1964 und 1981 Springtime for Ernst Jünger

Springtime for Ernst Jünger Stratege im Hintergrund

Stratege im Hintergrund Der Einzelne nach der Kehre

Der Einzelne nach der Kehre Unsere Total-Kalamität

Unsere Total-Kalamität

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

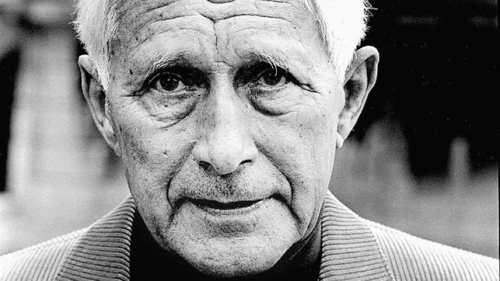

Passer des écrits d’Ernst Jünger sur la Première Guerre mondiale à la lecture de son journal parisien, tenu entre 1940 et 1944, peut surprendre. Que reste-t-il alors de l’officier héroïque de 1918 ? Que reste-t-il de celui qui célébrait avec une dimension mystique sa plongée dans la fureur de la guerre des tranchées ? Que reste-t-il encore de cette expérience combattante qui fit de lui un des officiers les plus décorés de l’armée allemande ? Au cours de ces 20 années, l’homme a incontestablement changé. De son Journal parisien, ce n’est plus l’ivresse du combat qui saisit mais, tout au contraire, l’atonie confortable de la douceur de vie parisienne. S’y exprime la sensibilité d’un homme qui ne semble avoir conservé du soldat que l’uniforme. La guerre y semble lointaine, étonnamment étrangère, alors que le monde s’embrase. L’homme enivré par le combat, le brave des troupes de choc a désormais disparu. L’écrivain semble traverser ce terrible conflit éloigné de toute ambition belliqueuse, porté par cet esprit contemplatif qu’il gardera jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Celui du poète mais aussi de l’entomologiste, l’homme des « chasses subtiles » comme il appelle lui-même ses recherches d’insectes rares. Et c’est encore, non pas en soldat, mais en naturaliste qu’il semble percevoir, dans le ciel de la capitale occupée, les immersions subites et meurtrières de la guerre. Ainsi, quand il observe, une flûte de champagne à la main, les escadrilles de bombardiers britanniques, la description qu’il en fait prend davantage la forme de celle d’un vol de coléoptères que de l’intrusion soudaine d’engins de morts, prêts à lâcher leurs bombes sur la ville.

Passer des écrits d’Ernst Jünger sur la Première Guerre mondiale à la lecture de son journal parisien, tenu entre 1940 et 1944, peut surprendre. Que reste-t-il alors de l’officier héroïque de 1918 ? Que reste-t-il de celui qui célébrait avec une dimension mystique sa plongée dans la fureur de la guerre des tranchées ? Que reste-t-il encore de cette expérience combattante qui fit de lui un des officiers les plus décorés de l’armée allemande ? Au cours de ces 20 années, l’homme a incontestablement changé. De son Journal parisien, ce n’est plus l’ivresse du combat qui saisit mais, tout au contraire, l’atonie confortable de la douceur de vie parisienne. S’y exprime la sensibilité d’un homme qui ne semble avoir conservé du soldat que l’uniforme. La guerre y semble lointaine, étonnamment étrangère, alors que le monde s’embrase. L’homme enivré par le combat, le brave des troupes de choc a désormais disparu. L’écrivain semble traverser ce terrible conflit éloigné de toute ambition belliqueuse, porté par cet esprit contemplatif qu’il gardera jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Celui du poète mais aussi de l’entomologiste, l’homme des « chasses subtiles » comme il appelle lui-même ses recherches d’insectes rares. Et c’est encore, non pas en soldat, mais en naturaliste qu’il semble percevoir, dans le ciel de la capitale occupée, les immersions subites et meurtrières de la guerre. Ainsi, quand il observe, une flûte de champagne à la main, les escadrilles de bombardiers britanniques, la description qu’il en fait prend davantage la forme de celle d’un vol de coléoptères que de l’intrusion soudaine d’engins de morts, prêts à lâcher leurs bombes sur la ville.

Acheter

Acheter  Évidemment, tout, absolument tout étant lié, surtout lorsqu'il s'agit des affinités électives existant entre les grands esprits qui appréhendent le monde en établissant des arches, parfois fragiles mais stupéfiantes de hardiesse, entre des réalités qu'en apparence rien ne relie (cf. p. 38), je ne pouvais, poursuivant la lecture de cet excellent petit livre qui m'a fait découvrir le fulgurant (et, apparemment, horripilant) Jacob Taubes, que finalement tomber sur le nom qui, selon ce dernier, reliait Maritain à Schmitt, qualifié de «profond penseur catholique» : Léon Bloy, autrement dit le porteur, le garnt ou, pourquoi pas, le «signe secret» (p. 96) lui-même. Après Kafka saluant le génie de l'imprécation bloyenne, c'est au tour du surprenant Taubes, au détour de quelques mots laissés sans la moindre explication, comme l'une de ces saillies propres aux interventions orales, qui stupéfièrent ou scandalisèrent et pourquoi pas stupéfièrent et scandalisèrent) celles et ceux qui, dans le public, écoutèrent ces maîtres de la parole que furent Taubes et Kojève (cf. p. 47). Il n'aura évidemment échappé à personne que l'un et l'autre, Kafka et le grand commentateur de la Lettre aux Romains de l'apôtre Paul, sont juifs, Jacob Taubes se déclarant même «Erzjude» «archijuif», traduction préférable à celle de «juif au plus profond» (p. 67) que donne notre petit livre : «l'ombre de l'antisémitisme actif se profilait sur notre relation, fragile comme toujours» (p. 47), écrit ainsi l'auteur en évoquant la figure de Carl Schmitt qui, comme Martin Heidegger mais aussi Adolf Hitler, est un «catholique éventé» dont le «génie du ressentiment» lui a permis de lire «les sources à neuf» (p. 112).

Évidemment, tout, absolument tout étant lié, surtout lorsqu'il s'agit des affinités électives existant entre les grands esprits qui appréhendent le monde en établissant des arches, parfois fragiles mais stupéfiantes de hardiesse, entre des réalités qu'en apparence rien ne relie (cf. p. 38), je ne pouvais, poursuivant la lecture de cet excellent petit livre qui m'a fait découvrir le fulgurant (et, apparemment, horripilant) Jacob Taubes, que finalement tomber sur le nom qui, selon ce dernier, reliait Maritain à Schmitt, qualifié de «profond penseur catholique» : Léon Bloy, autrement dit le porteur, le garnt ou, pourquoi pas, le «signe secret» (p. 96) lui-même. Après Kafka saluant le génie de l'imprécation bloyenne, c'est au tour du surprenant Taubes, au détour de quelques mots laissés sans la moindre explication, comme l'une de ces saillies propres aux interventions orales, qui stupéfièrent ou scandalisèrent et pourquoi pas stupéfièrent et scandalisèrent) celles et ceux qui, dans le public, écoutèrent ces maîtres de la parole que furent Taubes et Kojève (cf. p. 47). Il n'aura évidemment échappé à personne que l'un et l'autre, Kafka et le grand commentateur de la Lettre aux Romains de l'apôtre Paul, sont juifs, Jacob Taubes se déclarant même «Erzjude» «archijuif», traduction préférable à celle de «juif au plus profond» (p. 67) que donne notre petit livre : «l'ombre de l'antisémitisme actif se profilait sur notre relation, fragile comme toujours» (p. 47), écrit ainsi l'auteur en évoquant la figure de Carl Schmitt qui, comme Martin Heidegger mais aussi Adolf Hitler, est un «catholique éventé» dont le «génie du ressentiment» lui a permis de lire «les sources à neuf» (p. 112). C'est l'importance, capitale, de cette thématique que Jacob Taubes évoque lorsqu'il affirme que les écailles lui sont tombées des yeux quand il a lu «la courbe tracée par Löwith de Hegel à Nietzsche en passant par Marx et Kierkegaard» (p. 27), auteurs (Hegel, Marx et Kierkegaard) qu'il ne manquera pas d'évoquer dans son Eschatologie occidentale (Nietzsche l'étant dans sa Théologie politique de Paul) en expliquant leur philosophie par l'apocalyptique souterraine qui n'a à vrai dire jamais cessé d'irriguer le monde (4) dans ses multiples transformations, et paraît même s'être orientée, avec le régime nazi, vers une furie de destruction du peuple juif, soit ce peuple élu jalousé par le catholiques (et même les chrétiens) conséquents. Lisons l'explication de Taubes, qui pourra paraître une réduction aux yeux de ses adversaires ou une fulgurance dans l'esprit de ses admirateurs : «Carl Schmitt était membre du Reich allemand avec ses prétentions au Salut», tandis que lui, Taubes, était «fils du peuple véritablement élu par Dieu, suscitant donc l'envie des nations apocalyptiques, une envie qui donne naissance à des fantasmagories et conteste le droit de vivre au peuple réellement élu» (pp. 48-9, le passage plus haut cité suit immédiatement ces lignes).

C'est l'importance, capitale, de cette thématique que Jacob Taubes évoque lorsqu'il affirme que les écailles lui sont tombées des yeux quand il a lu «la courbe tracée par Löwith de Hegel à Nietzsche en passant par Marx et Kierkegaard» (p. 27), auteurs (Hegel, Marx et Kierkegaard) qu'il ne manquera pas d'évoquer dans son Eschatologie occidentale (Nietzsche l'étant dans sa Théologie politique de Paul) en expliquant leur philosophie par l'apocalyptique souterraine qui n'a à vrai dire jamais cessé d'irriguer le monde (4) dans ses multiples transformations, et paraît même s'être orientée, avec le régime nazi, vers une furie de destruction du peuple juif, soit ce peuple élu jalousé par le catholiques (et même les chrétiens) conséquents. Lisons l'explication de Taubes, qui pourra paraître une réduction aux yeux de ses adversaires ou une fulgurance dans l'esprit de ses admirateurs : «Carl Schmitt était membre du Reich allemand avec ses prétentions au Salut», tandis que lui, Taubes, était «fils du peuple véritablement élu par Dieu, suscitant donc l'envie des nations apocalyptiques, une envie qui donne naissance à des fantasmagories et conteste le droit de vivre au peuple réellement élu» (pp. 48-9, le passage plus haut cité suit immédiatement ces lignes).  Cette complexité se retrouve dans le jugement de Jacob Taubes sur Carl Schmitt qui, ce point au moins est évident, avait une réelle importance intellectuelle à ses yeux, était peut-être même l'un des seuls contemporains pour lequel il témoigna de l'estime, au-delà même du fossé qui les séparait : «On vous fait réciter un alphabet démocratique, et tout privat-docent en politologie est évidemment obligé, dans sa leçon inaugurale, de flanquer un coup de pied au cul à Carl Schmitt en disant que la catégorie ami / ennemi n'est pas la bonne. Toute une science s'est édifiée là pour étouffer le problème» (p. 115), problème qui seul compte, et qui, toujours selon Jacob Taubes, a été correctement posé par le seul Carl Schmitt, problème qui n'est autre que l'existence d'une «guerre civile en cours à l'échelle mondiale» (p. 109). Dans sa belle préface, Elettra Stimilli a du reste parfaitement raison de rapprocher, de façon intime, les pensées de Schmitt et de Taubes, écrivant : «Révolution et contre-révolution ont toujours évolué sur le plan linéaire du temps, l'une du point de vue du progrès, l'autre de celui de la tradition. Toutes deux sont liées par l'idée d'un commencement qui, depuis l'époque romaine, est essentiellement une «fondation». Si du côté de la tradition cela ne peut qu'être évident, étant donné que déjà le noyau central de la politique romaine est la foi dans la sacralité de la fondation, entendue comme ce qui maintient un lien entre toutes les générations futures et doit pour cette raison être transmise, par ailleurs, nous ne parviendrons pas à comprendre les révolutions de l'Occident moderne dans leur grandeur et leur tragédie si, comme le dit Hannah Arendt, nous ne le concevons pas comme «autant d'efforts titanesques accomplis pour reconstruire les bases, renouer le fil interrompu de la tradition et restaurer, avec la fondation de nouveaux systèmes politiques, ce qui pendant tant de siècles a conféré dignité et grandeur aux affaires humaines» (pp. 15-6).

Cette complexité se retrouve dans le jugement de Jacob Taubes sur Carl Schmitt qui, ce point au moins est évident, avait une réelle importance intellectuelle à ses yeux, était peut-être même l'un des seuls contemporains pour lequel il témoigna de l'estime, au-delà même du fossé qui les séparait : «On vous fait réciter un alphabet démocratique, et tout privat-docent en politologie est évidemment obligé, dans sa leçon inaugurale, de flanquer un coup de pied au cul à Carl Schmitt en disant que la catégorie ami / ennemi n'est pas la bonne. Toute une science s'est édifiée là pour étouffer le problème» (p. 115), problème qui seul compte, et qui, toujours selon Jacob Taubes, a été correctement posé par le seul Carl Schmitt, problème qui n'est autre que l'existence d'une «guerre civile en cours à l'échelle mondiale» (p. 109). Dans sa belle préface, Elettra Stimilli a du reste parfaitement raison de rapprocher, de façon intime, les pensées de Schmitt et de Taubes, écrivant : «Révolution et contre-révolution ont toujours évolué sur le plan linéaire du temps, l'une du point de vue du progrès, l'autre de celui de la tradition. Toutes deux sont liées par l'idée d'un commencement qui, depuis l'époque romaine, est essentiellement une «fondation». Si du côté de la tradition cela ne peut qu'être évident, étant donné que déjà le noyau central de la politique romaine est la foi dans la sacralité de la fondation, entendue comme ce qui maintient un lien entre toutes les générations futures et doit pour cette raison être transmise, par ailleurs, nous ne parviendrons pas à comprendre les révolutions de l'Occident moderne dans leur grandeur et leur tragédie si, comme le dit Hannah Arendt, nous ne le concevons pas comme «autant d'efforts titanesques accomplis pour reconstruire les bases, renouer le fil interrompu de la tradition et restaurer, avec la fondation de nouveaux systèmes politiques, ce qui pendant tant de siècles a conféré dignité et grandeur aux affaires humaines» (pp. 15-6).

- 4 - Là était la beauté de l'ancien ordre aristocratique : chacun était pleinement respecté dans son caractère spécifique, à son rang reconnu, et chacun se comportait sincèrement selon ce rang, de sorte qu'il ne pouvait y avoir de conflits nés de la jalousie ou de l'envie.

- 4 - Là était la beauté de l'ancien ordre aristocratique : chacun était pleinement respecté dans son caractère spécifique, à son rang reconnu, et chacun se comportait sincèrement selon ce rang, de sorte qu'il ne pouvait y avoir de conflits nés de la jalousie ou de l'envie. - 11 - Pour moi, dès ma prime jeunesse, je n'étais jamais tombé amoureux ; en tout cas je ne m'étais jamais avoué qu'un amour germait en moi, car mon inconscient très puritain n'admettait pas la simple possibilité d'une chute dans la sensualité, condamnée comme une faiblesse. En outre la conscience des hommes baltes de ma génération qui furent plus ou moins mes contemporains, était encore entièrement déterminée par la tension : sanctuaire inviolable - vice […] ce qui les conduisait d'une part à idéaliser démesurément la femme dite "comme il faut", d'autre part à traîner dans la boue, avec autant d'exagération, toute femme qui menait une vie contraire à l'idéal, ce qui excluait une vie amoureuse libre sous la forme de la beauté.

- 11 - Pour moi, dès ma prime jeunesse, je n'étais jamais tombé amoureux ; en tout cas je ne m'étais jamais avoué qu'un amour germait en moi, car mon inconscient très puritain n'admettait pas la simple possibilité d'une chute dans la sensualité, condamnée comme une faiblesse. En outre la conscience des hommes baltes de ma génération qui furent plus ou moins mes contemporains, était encore entièrement déterminée par la tension : sanctuaire inviolable - vice […] ce qui les conduisait d'une part à idéaliser démesurément la femme dite "comme il faut", d'autre part à traîner dans la boue, avec autant d'exagération, toute femme qui menait une vie contraire à l'idéal, ce qui excluait une vie amoureuse libre sous la forme de la beauté.

Maar het zijn protestanten in Noordwest-Europa die zich tot echte zeemachten ontwikkelen, doordat watergeuzen en piraten een primaire afhankelijkheid van de zee ontwikkelen. Het zullen uiteindelijk dan ook de Engelsen (en zij die als de Engelsen denken) zijn die de vrijgemaakte maritieme energieën beërven en het idee propageren dat de zee vrij is, dat de zee niemand toebehoort.Dat idee lijkt eerlijk genoeg, de zee is vrij dus van iedereen, niet waar? Maar als de open zee niemand toebehoort, geldt er uiteindelijk het recht van de sterkste. “De landoorlog heeft de tendens naar een open veldslag die beslissend is”, schrijft Schmitt. “In de zeeoorlog kan het natuurlijk ook tot een zeeslag komen, maar zijn kenmerkende middelen en methoden zijn beschieting en blokkade van vijandelijke kusten en confiscatie van vijandige en neutrale handelsschepen [..]. Het ligt in de aard van deze typerende middelen van de zeeoorlog, dat zij zich zowel tegen vechtenden als niet-vechtenden richten.”

Maar het zijn protestanten in Noordwest-Europa die zich tot echte zeemachten ontwikkelen, doordat watergeuzen en piraten een primaire afhankelijkheid van de zee ontwikkelen. Het zullen uiteindelijk dan ook de Engelsen (en zij die als de Engelsen denken) zijn die de vrijgemaakte maritieme energieën beërven en het idee propageren dat de zee vrij is, dat de zee niemand toebehoort.Dat idee lijkt eerlijk genoeg, de zee is vrij dus van iedereen, niet waar? Maar als de open zee niemand toebehoort, geldt er uiteindelijk het recht van de sterkste. “De landoorlog heeft de tendens naar een open veldslag die beslissend is”, schrijft Schmitt. “In de zeeoorlog kan het natuurlijk ook tot een zeeslag komen, maar zijn kenmerkende middelen en methoden zijn beschieting en blokkade van vijandelijke kusten en confiscatie van vijandige en neutrale handelsschepen [..]. Het ligt in de aard van deze typerende middelen van de zeeoorlog, dat zij zich zowel tegen vechtenden als niet-vechtenden richten.”

Ensuite, certains appliquent un verni (pseudo-)polythéiste à l’athéisme. Tel est le cas d’Alain de Benoist, notamment, à l’époque de son livre Comment peut-on être païen ? (3). Faisant fi de son athéisme, il faut tout de même saluer le « paganisme philosophique » professé dans cet ouvrage de qualité. En ce qui nous concerne, notre critique du livre d’Alain de Benoist demeure semblable à celle de l’auteur américain Collin Cleary (4) qui lui oppose un polythéisme théiste aux accents heideggériens.

Ensuite, certains appliquent un verni (pseudo-)polythéiste à l’athéisme. Tel est le cas d’Alain de Benoist, notamment, à l’époque de son livre Comment peut-on être païen ? (3). Faisant fi de son athéisme, il faut tout de même saluer le « paganisme philosophique » professé dans cet ouvrage de qualité. En ce qui nous concerne, notre critique du livre d’Alain de Benoist demeure semblable à celle de l’auteur américain Collin Cleary (4) qui lui oppose un polythéisme théiste aux accents heideggériens.  Le sujet que nous abordons constitue peut-être la racine principale de ce que l’on nomme paganisme : la relation de l’homme à sa terre, à la nature et au Kosmos; ces relations, ou plutôt interrelations, nous pourrions les réunir dans une seule expression, celle d’« écologie profonde » (ou « écologie intégrale »). Préoccupation majeure, l’écologie est malheureusement délaissée par de nombreuses personnes se réclamant de Droite au titre qu’elle serait de Gauche. Grave erreur ! La Gauche (extrême) a mis le grappin sur les questions environnementales, car la Droite radicale – sauf certains mouvements faisant exception comme feu le MAS ou, dans un registre plus « folklorique » dirons-nous, le Greenline Front – a abandonné ce thème qui fut le sien à l’origine. Heureusement vient de paraître aux éditions Akribeia un livre qui, nous espérons, remettra les pendules à l’heure, Piété pour le cosmos de l’Italien Giovanni Monastra et du Français Philippe Baillet.

Le sujet que nous abordons constitue peut-être la racine principale de ce que l’on nomme paganisme : la relation de l’homme à sa terre, à la nature et au Kosmos; ces relations, ou plutôt interrelations, nous pourrions les réunir dans une seule expression, celle d’« écologie profonde » (ou « écologie intégrale »). Préoccupation majeure, l’écologie est malheureusement délaissée par de nombreuses personnes se réclamant de Droite au titre qu’elle serait de Gauche. Grave erreur ! La Gauche (extrême) a mis le grappin sur les questions environnementales, car la Droite radicale – sauf certains mouvements faisant exception comme feu le MAS ou, dans un registre plus « folklorique » dirons-nous, le Greenline Front – a abandonné ce thème qui fut le sien à l’origine. Heureusement vient de paraître aux éditions Akribeia un livre qui, nous espérons, remettra les pendules à l’heure, Piété pour le cosmos de l’Italien Giovanni Monastra et du Français Philippe Baillet.  La première partie de l’ouvrage s’intitule « Les racines révolutionnaires-conservatrices de la pensée écologique », elle est l’œuvre de Giovanni Monastra. Celui-ci débute son exposé par un constat évident, à savoir la césure entre l’homme et la nature, séparation qui s’est d’autant plus accéléré à cause de la révolution scientifique et de la révolution industrielle. Cet état dichotomique procède de la dégradation cyclique, la relation entre l’homme et la nature n’a pas toujours été ainsi comme le rappelle l’auteur. Les sociétés traditionnelles connurent une relation empathique et holistique de la nature. « La première modalité, dominante par le passé et qui renaît de nos jours, consiste en une approche empathique et holistique, donc une approche qui perçoit et “ sent ” la réalité vivante comme un Tout au sein duquel les différentes parties, du niveau microscopique aux macrosystèmes en passant par celui où nous nous situons, ont certes leur autonomie (et cela vaut en premier lieu pour l’homme, dont la liberté est hors de question), mais où cette autonomie ne revient pas à nier les interrelations profondes qui existent entre les parties. Tout cela s’accorde avec la conception de la nature comme “ puissance ” créatrice et sacrée (pour les cultures prémodernes), force unitaire ordonnée et complexe, gouvernée par un équilibre délicat qu’il ne faut pas enfreindre, mais au contraire respecter, si bien qu’il importe de ne pas dépasser certaines “ limites ” (p. 11.). »

La première partie de l’ouvrage s’intitule « Les racines révolutionnaires-conservatrices de la pensée écologique », elle est l’œuvre de Giovanni Monastra. Celui-ci débute son exposé par un constat évident, à savoir la césure entre l’homme et la nature, séparation qui s’est d’autant plus accéléré à cause de la révolution scientifique et de la révolution industrielle. Cet état dichotomique procède de la dégradation cyclique, la relation entre l’homme et la nature n’a pas toujours été ainsi comme le rappelle l’auteur. Les sociétés traditionnelles connurent une relation empathique et holistique de la nature. « La première modalité, dominante par le passé et qui renaît de nos jours, consiste en une approche empathique et holistique, donc une approche qui perçoit et “ sent ” la réalité vivante comme un Tout au sein duquel les différentes parties, du niveau microscopique aux macrosystèmes en passant par celui où nous nous situons, ont certes leur autonomie (et cela vaut en premier lieu pour l’homme, dont la liberté est hors de question), mais où cette autonomie ne revient pas à nier les interrelations profondes qui existent entre les parties. Tout cela s’accorde avec la conception de la nature comme “ puissance ” créatrice et sacrée (pour les cultures prémodernes), force unitaire ordonnée et complexe, gouvernée par un équilibre délicat qu’il ne faut pas enfreindre, mais au contraire respecter, si bien qu’il importe de ne pas dépasser certaines “ limites ” (p. 11.). » Avant d’évoquer plusieurs précurseurs de l’écologie, et d’autres défenseurs de la nature, Giovanni Monastra se devait de mentionner le rapport entre la Gauche et les mouvements de préservation de la nature de manière générale. De nos jours, les partis écologistes sont souvent synonyme de partis d’extrême gauche, à tel point qu’un politicien comme Jean-Marie Le Pen les qualifiait de « pastèques » puisque vert à l’extérieur et rouge à l’intérieur, cette couleur désignant, bien entendu, leur véritable couleur politique. Assimiler l’écologie et la Gauche est « une énorme tromperie, qui a malheureusement pu s’appuyer aussi sur la façon de penser et le comportement concret […] d’une large faction des milieux de “ droite ” européens (p. 18) ». Pourtant, quelle soit marxiste ou pas, la Gauche ne fut pas toujours l’amie de l’écologie. « Elle a toujours exalté les vertus émancipatrices du progrès matériel sous toutes ses formes, au point de se faire la championne la plus stupide de l’industrialisme le plus exacerbé, à l’origine de toutes les pollutions. Le marxisme, lui, a toujours été intrinsèquement hostile aux perspectives écologistes. […] Selon Marx, la nature doit être “ humanisée” à travers la science afin de transformer la valeur intrinsèque du milieu en valeur d’usage pour l’homme (p. 19). »

Avant d’évoquer plusieurs précurseurs de l’écologie, et d’autres défenseurs de la nature, Giovanni Monastra se devait de mentionner le rapport entre la Gauche et les mouvements de préservation de la nature de manière générale. De nos jours, les partis écologistes sont souvent synonyme de partis d’extrême gauche, à tel point qu’un politicien comme Jean-Marie Le Pen les qualifiait de « pastèques » puisque vert à l’extérieur et rouge à l’intérieur, cette couleur désignant, bien entendu, leur véritable couleur politique. Assimiler l’écologie et la Gauche est « une énorme tromperie, qui a malheureusement pu s’appuyer aussi sur la façon de penser et le comportement concret […] d’une large faction des milieux de “ droite ” européens (p. 18) ». Pourtant, quelle soit marxiste ou pas, la Gauche ne fut pas toujours l’amie de l’écologie. « Elle a toujours exalté les vertus émancipatrices du progrès matériel sous toutes ses formes, au point de se faire la championne la plus stupide de l’industrialisme le plus exacerbé, à l’origine de toutes les pollutions. Le marxisme, lui, a toujours été intrinsèquement hostile aux perspectives écologistes. […] Selon Marx, la nature doit être “ humanisée” à travers la science afin de transformer la valeur intrinsèque du milieu en valeur d’usage pour l’homme (p. 19). » Giovanni Monastra va donc ensuite énumérer, en les présentant eux et leur idées, différents penseurs écologistes ou proche de la nature. Citons Ernst Haeckel, Ernst Moritz Arndt, Wilhelm Heinrich von Riehl, l’écrivain norvégien Knut Hamsun, les frères Friedrich Georg et Ernst Jünger, Oswald Spengler – qui dénonça « la domination de la technique [qui] nourrit la toute-puissance de l’économie et la diffusion cancérigène du marché, tout en s’en nourrissant elle-même (p. 46) » – Konrad Lorenz, Alexis Carrel, Ortega y Gasset, Julius Evola, René Guénon, etc. Parmi tous ces brillants penseurs, Giovanni Monastra s’intéresse particulièrement à un personnage regrettablement méconnu en France : Ludwig Klages (photo).

Giovanni Monastra va donc ensuite énumérer, en les présentant eux et leur idées, différents penseurs écologistes ou proche de la nature. Citons Ernst Haeckel, Ernst Moritz Arndt, Wilhelm Heinrich von Riehl, l’écrivain norvégien Knut Hamsun, les frères Friedrich Georg et Ernst Jünger, Oswald Spengler – qui dénonça « la domination de la technique [qui] nourrit la toute-puissance de l’économie et la diffusion cancérigène du marché, tout en s’en nourrissant elle-même (p. 46) » – Konrad Lorenz, Alexis Carrel, Ortega y Gasset, Julius Evola, René Guénon, etc. Parmi tous ces brillants penseurs, Giovanni Monastra s’intéresse particulièrement à un personnage regrettablement méconnu en France : Ludwig Klages (photo).  Giovanni Monastra, se réclamant de l’immense œuvre de Julius Evola, met brièvement en lumière la pensées du philosophe italien concernant la nature ou plutôt sa vision de la nature, bien qu’elle ne représente pas un sujet à part entière dans son œuvre. Notons qu’Evola critiquait tout mouvements de « retour à la nature » qu’il identifiait à une réponse catagogique à un vide existentiel, les deux émanant d’une société « crépusculaire et décomposée ». Evola connaissait bien l’un des aspects de la nature, celui qui défie les hommes et les pousse à se surpasser, quitte à y laisser la vie. Alpiniste chevronné sa vision de la nature ne se targue d’aucun matérialisme, ni d’aucun sentimentalisme, Giovanni Monastra cite le philosophe. Il « s’agit donc de rendre à la nature – à l’espace, aux choses, au paysage – ce caractère lointain et étranger à l’homme qui était couvert à l’époque de l’individualisme, quand l’homme projetait dans la réalité, pour se la rendre proche, ses sentiments, ses passions, ses petits élans lyriques. Il s’agit de redécouvrir le langage de l’inanimé […]. C’est de cette façon que la nature peut parler à la transcendance (p. 60) ».

Giovanni Monastra, se réclamant de l’immense œuvre de Julius Evola, met brièvement en lumière la pensées du philosophe italien concernant la nature ou plutôt sa vision de la nature, bien qu’elle ne représente pas un sujet à part entière dans son œuvre. Notons qu’Evola critiquait tout mouvements de « retour à la nature » qu’il identifiait à une réponse catagogique à un vide existentiel, les deux émanant d’une société « crépusculaire et décomposée ». Evola connaissait bien l’un des aspects de la nature, celui qui défie les hommes et les pousse à se surpasser, quitte à y laisser la vie. Alpiniste chevronné sa vision de la nature ne se targue d’aucun matérialisme, ni d’aucun sentimentalisme, Giovanni Monastra cite le philosophe. Il « s’agit donc de rendre à la nature – à l’espace, aux choses, au paysage – ce caractère lointain et étranger à l’homme qui était couvert à l’époque de l’individualisme, quand l’homme projetait dans la réalité, pour se la rendre proche, ses sentiments, ses passions, ses petits élans lyriques. Il s’agit de redécouvrir le langage de l’inanimé […]. C’est de cette façon que la nature peut parler à la transcendance (p. 60) ».

Philippe Baillet débute son étude avec la notion de conservatisme. Le dictionnaire Larousse propose la définition suivante : « Attitude ou tendance de quelqu’un, d’un groupe ou d’une société, définie par le refus du changement et la référence sécurisante à des valeurs ou des structures immuables (1). » Un brin réducteur tout de même que cette définition. Nonobstant les a priori partisans sur le conservatisme, le bon sens voudrait que sa définition première corresponde au maintien et à la préservation de ce qui est bien pour une société ou une nation. Ainsi préserver, conserver la nature intacte n’est-il pas, au-delà de la nécessité vitale, une question politique de bien commun ?

Philippe Baillet débute son étude avec la notion de conservatisme. Le dictionnaire Larousse propose la définition suivante : « Attitude ou tendance de quelqu’un, d’un groupe ou d’une société, définie par le refus du changement et la référence sécurisante à des valeurs ou des structures immuables (1). » Un brin réducteur tout de même que cette définition. Nonobstant les a priori partisans sur le conservatisme, le bon sens voudrait que sa définition première corresponde au maintien et à la préservation de ce qui est bien pour une société ou une nation. Ainsi préserver, conserver la nature intacte n’est-il pas, au-delà de la nécessité vitale, une question politique de bien commun ?

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man.

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man. Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his