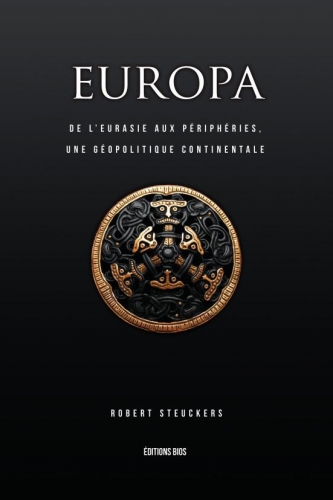

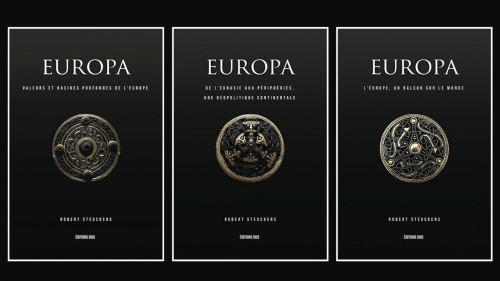

Parerga & Paralipomena for Robert Steuckers’ Europa II. De l’Eurasie aux périphéries, une géopolitique continentale (Madrid: BIOS, 2017)

Prologue: trois couleurs

Sur Bruxelles, au pied de l'archange,

Ton saint drapeau pour jamais est planté

[Over Brussels, at the feet of our archangel,

Your sacred flag has been planted for all eternity][1]

- La Brabançonne

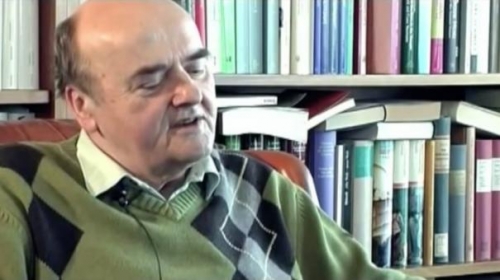

A storm of unprecedented magnitude is slowly taking shape on the cultural-historical horizon of the postmodern West: with the approaching climax of the Crisis of the Modern West - more precisely described by Jason Jorjani as the imminent ‘World State of Emergency’ - the prospect of an ‘Archaeo-Futurist Revolution’ is looming large as well.[2] The patriotic-identitarian movement which is currently showing rapid growth throughout the entire Western world may be viewed as the ‘storm bird’ harbinger of this Archaeo-Futurist Revolution.[3] It is important that this movement formulates effective metapolitical strategies in preparation for the imminent social-political bankruptcy of the present (double neo-liberal/cultural-marxist) globalist world order. The oldest metahistorical discourse available to this movement is Traditionalism. The only global geopolitical vision that currently incorporates a substantial element of Traditionalism is Eurasianism. This essay aims at a providing an introduction to the Traditionalist-inspired Neo-Eurasianism that is most succinctly expressed in the work of Russian philosopher and publicist Aleksandr Dugin. In addition, however, this essay aims at pointing out that authentic Traditionalist thinking and writing is also taking place in the Low Countries, even if it tends to be obscured by the politically-correct (self-)censorship of the academic review mill and the system media. This essay is dedicated to the most eminent - and longest-serving - writer of the typically autonomous Traditionalism that thrives in the Low Countries: Robert Steuckers. Recently, he published an encyclopaedic work on the origins, history and current state of European civilization: his triptych Europa constitutes an intellectual tour de force of a depth and width that will be impossible to smother in the politically-correct ‘cover-up’ that is the weapon of choice of (self-)censorious system-publicists. Europa is written in French and has, thus far, not been translated into English; the lamentable decline of French language instruction throughout the West renders it therefore inaccessible to much of its primary target audience: the patriotically-minded and identity-aware intellectual avant garde of young Europe. Throughout the entire Western world, this génération identitaire is preparing for the all-out final battle for its highly endangered heritage: its Western homeland - and Western civilization itself. This essay aims at (somewhat) mitigating this inaccessibility by transmitting to a wider non-francophone audience at least some of the knowledge that Steuckers presents in Europa. In the estimation of the undersigned reviewer, Steuckers’ Europa is a jewel - a small reflection of the Golden Dawn that Traditionalism and Eurasianism look back and forward to. Thus, Belgium - and Brussels - has more to offer than the counterfeit ‘Europe’ of the EU: it also offers the Archaeo-Futurist vision of Robert Steuckers’ Europa. This essay is therefore not only dedicated to Steuckers himself, but also to his country: Belgium.

Although the (French-revolutionary) orientation and (heraldic-traditional) colours of the Belgian flag are historically predictable for anybody acquainted with the unique genesis of the Belgian state, it still is very unusual in one respect. Perhaps its strange - nearly square (13:15) - proportions reflects the historical particularity of Belgium’s geopolitical configuration: effectively, Belgium represents a cultural-historical restgebied, or ‘left over’, that was legally established as a sovereign ‘buffer zone’ for the sake of the early-19th Century ‘balance of power’ compromise between Britain, France and Prussia. Only in terms of its colours can the Belgian flag claim an authentically traditional (i.e. doubly historical and symbolic) pedigree. Between the blood red colour of the land provinces of Luxembourg, Hainaut and Limburg and the sable black colour of the mighty coastal province of Flanders, it shows the gold yellow of the prosperous province of Brabant with its capital Brussels, which has been the administrative seat of pan-European power from pre-modern Burgundian state up to the post-modern European Union. The Belgian red and black have the same heraldic-symbolic charge as the Eurasian red and black: in both, red is the colour of worldly power (Nobility, army) and black is the colour of other-worldly power (Church, clergy). In the holistic vision of Traditionalist Eurasianism, these colours necessarily complement each other: together they represent the intimidating combination of the approaching storm (divinely ordained Deluge) and war (divinely ordained Holy War). Right up to this day, everyone knows that the red-and-black flag represents revolution, even if Social Justice Warrior ideologues fail to recognize the true - back-ward and up-ward - direction of every authentic re-volution (in casu: the Archaeo-Futurist Revolution). Between the Belgium blood red and sable black is found the colour that may be said to be in virtual ‘occultation’ in Eurasianism: the gold yellow that has the heraldic-symbolic charge of the heavenly light and the Golden Dawn - and thus of Traditionalism itself. A tiny ray of that light comes to us from Brabant in Steuckers’ Europa.

Although the (French-revolutionary) orientation and (heraldic-traditional) colours of the Belgian flag are historically predictable for anybody acquainted with the unique genesis of the Belgian state, it still is very unusual in one respect. Perhaps its strange - nearly square (13:15) - proportions reflects the historical particularity of Belgium’s geopolitical configuration: effectively, Belgium represents a cultural-historical restgebied, or ‘left over’, that was legally established as a sovereign ‘buffer zone’ for the sake of the early-19th Century ‘balance of power’ compromise between Britain, France and Prussia. Only in terms of its colours can the Belgian flag claim an authentically traditional (i.e. doubly historical and symbolic) pedigree. Between the blood red colour of the land provinces of Luxembourg, Hainaut and Limburg and the sable black colour of the mighty coastal province of Flanders, it shows the gold yellow of the prosperous province of Brabant with its capital Brussels, which has been the administrative seat of pan-European power from pre-modern Burgundian state up to the post-modern European Union. The Belgian red and black have the same heraldic-symbolic charge as the Eurasian red and black: in both, red is the colour of worldly power (Nobility, army) and black is the colour of other-worldly power (Church, clergy). In the holistic vision of Traditionalist Eurasianism, these colours necessarily complement each other: together they represent the intimidating combination of the approaching storm (divinely ordained Deluge) and war (divinely ordained Holy War). Right up to this day, everyone knows that the red-and-black flag represents revolution, even if Social Justice Warrior ideologues fail to recognize the true - back-ward and up-ward - direction of every authentic re-volution (in casu: the Archaeo-Futurist Revolution). Between the Belgium blood red and sable black is found the colour that may be said to be in virtual ‘occultation’ in Eurasianism: the gold yellow that has the heraldic-symbolic charge of the heavenly light and the Golden Dawn - and thus of Traditionalism itself. A tiny ray of that light comes to us from Brabant in Steuckers’ Europa.

(*)The undersigned reviewer has chosen to provide a double presentation of both Steuckers’ original - razorblade sharp and acidly abrasive - French text and an English translation. The reviewer shares the considered opinion of Dutch patriotic publicist Alfred Vierling that the French linguistic culture is quintessentially different from the globally dominant Anglo-Saxon linguistic culture to such a degree that French language skills are indispensable for any Western reader who wishes to claim a balanced worldview. The dramatic general lack of prerequisite French language skills, however, cannot be blamed entirely on young Westerners themselves: this glaring educational hiatus is caused by the long-term and deliberate ‘dumbing down’ strategy of the Western ‘hostile elite’. In the reviewer’s native Netherlands this ‘dumbing down’ program may have accelerated during the ‘slash and burn’ tenure of present Prime Minister Mark Rutte as Undersecretary of (mis-)Education, but it may be traced back all the way to the all-levelling Mammoet Wet legislation of the Beatnik generation. The reviewer has opted to present the reader with Steuckers’ original French text as well as his own somewhat (contextually) approximate English translation - obviously, he is responsible for less successful attempts at translating Steuckers’ ‘biting’ Walloon French into equivalent English expressions. A glossary with extra Steuckerian neologisms is added at the end of the text.

(**)By and large, the division of this essay into ‘question paragraphs’ (with tentative ‘answers’ provided in their motto subtitles) reflects the original organization of Chapter I of Europa Part II (which is the written version of an interview). Some adjustments have been made to allow for a quick grasp of the basic principles of Eurasianism by all interested readers.

What is the cultural-historical role of Eurasianism?

History is written by those who hang heroes

- Robert the Bruce

In introducing Eurasianism it is essential to point to its long durée perspective on Western civilization: Steuckers does this by referring to the prehistoric roots of the European peoples, which may be traced back to the end of the last Ice Age and their oldest territorial cradle between Thuringia and southern Finland. Gradually expanding outward from their oldest ancestral ground, they finally came to dominate the entire Eurasian space between the Atlantic seaboard and the Himalayan barrier. Doubtlessly, the archetypal experience of this prehistoric ‘European Adventure’ - the exploration and exploitation of the immensely varied pristine landscapes that are found between the frozen mists of Scandinavia and the steamy jungles of India - has been a decisive factor in shaping the ‘Faustian’ character of the European peoples, challenging them to bridge all horizons. This self-surpassing instinct - a subtle combination of inspired vision, all-conquering hubris and technical genius - has put an indelible stamp on the archetypes of Western Civilization, from Classic Greek Titans and Argonauts to Late Modern atom-breakers and astronauts. Taming the horse and mastering metal technique allowed the proto-Europeans to militarily control the steppe centre of the Eurasian space around the dawn of written history. Steuckers points to the fact that even at the heyday of the most ancient Indo-European empires - Achaemenid Persia, Alexandrian Macedonia, Maurya India - semi-mythical horse master peoples such as the Scythians and Sarmatians still ruled the Eurasian Steppe. It was along the geopolitical ‘world axis’, which provides a virtually ‘level playing ground’ from Hungary all the way to Manchuria, that the fate of the European peoples was decided at various crucial junctures.

Steuckers points out that the thirteen centuries of European history that followed the end of the Indo-European power monopoly over the Eurasian Steppe – as marked by the rise of Attila’s Hunnic Empire (406-453) - effectively constitute a single and continuous struggle to regain the initiative from the competing Turco-Mongolian peoples that came storming westward out of the eastern steppes. From this perspective, the Hunnic defeat on the Catalaunian Fields (451) does not represent a true European victory, but rather the - thus far - lowest ebb of the European civilization, then pushed back to barely 300 kilometres from the Atlantic coast. It is only in the course of the 16th and 17th Centuries that the Asiatic assault on Europe is finally reversed: the Ottoman threat to the European heartland is only decisively defeated after the naval victory at Lepanto (1571) and the lifting of the second siege of Vienna (1683). In this context, Steuckers points to the vital role that the Cossack cavalry armies played in the subsequent two hundred years’ reconquista of the Eurasian Steppe (archetypically expressed as ‘Rohan’ sweeping the ‘Pelennor Fields’). This great ‘push back’ finally created the ‘bridge of civilization’ that still links the two great civilizational poles of the Eurasian landmass: Europe in the west and China in the east: this bridge of civilization represents the centrepiece of the Eurasian Project.

It is the Early Modern Reconquista of the Eurasian centre that provides the foundation of Classic Modern European global power. The anchor of the global ‘European Imperium’ is found in the Diplomatic Revolution - a.k.a. the renversement des alliances - of 1756 and the subsequent strategic alliance between the great powers of Spain, France, Austria and Russia, controlling the entire Eurasian space between Finisterre and Kamchatka. The Seven Years’ War (1756-63) that follows the Diplomatic Revolution has received the fitting nickname of ‘World War Zero’: it constitutes the first round in the prolonged confrontation between Anglo-Saxon-led ‘thalassocracy’ and (proto-)Eurasianist land power. The catastrophic maritime and colonial defeats of France resulted in the loss of nearly all French possessions in North America and South Asia: this is the geopolitical foundation of the Anglo-Saxon ‘sea power’ hegemony that persists till today. Abstractly, Anglo-Saxon thalassocracy represents sea power-based Western Modernity, whereas the Eurasian continental monarchies represent land power-based Western Tradition. This civilizational divide represents the - quintessentially Traditionalist - centrepiece of Eurasian thought.

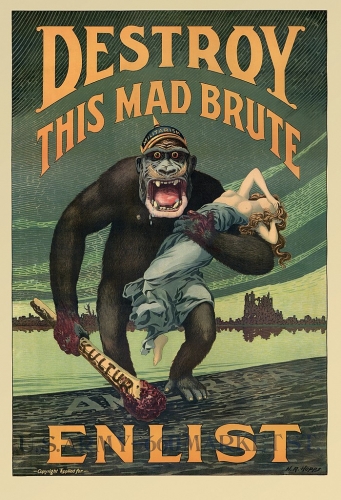

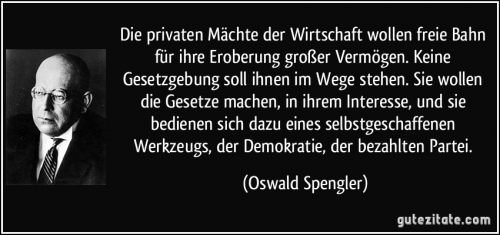

The French Revolution - ironically directly caused by the French state bankruptcy that followed the French naval revenge on Britain during the American Revolution (1775-83) - marks the point at which thalassocratic Modernity manages to create a substantial ‘bridgehead’ on the European continent. As a focal point of revolutionary upheaval and anti-Eurasianist geopolitics, France subsequently functions as a continental ‘wedge’ for the forces of thalassocratic Modernity all throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries.[4] The post-Napoleonic restoration of the Traditionalist Bourbons and the creation of the (proto-)Eurasianist Holy Alliance (1815) do not fundamentally alter this equation: in 1830 France relapses into revolutionary policies - by that time the Holy Alliance had already proven itself to be a ‘paper tiger’ by its failure to stem the revolutionary tide both inside and outside Europe. By then, nearly the entire New World has been lost to freemasonic liberalism, which shielded the Americas from Eurasianist intervention by the Monroe Doctrine. Slowly but steadily, the global balance of power shifted in favour of Atlanticist thalassocracy as it crept into the European heartland through escalating revolutionary contagion. In this context, Steuckers correctly points to the crucial significance of the Anglo-French rapprochement: in his view, the Crimean War (1853-56) marks the point at which the Eurasian space west of the Rhine is irretrievably lost. Some years later, Bismarck’s resurrected (Second) German Empire takes over the role as Eurasian ‘border guard’ that has been abandoned by France as it sinks into republican decadence. Germany’s Wacht am Rhein as guardian of the European Tradition begins. But as the Second Industrial Revolution combines with Modern Imperialism to create an irresistibly rising global règne de la quantité, the decline of Traditionalist Eurasia is a foregone conclusion. The global strategic weakness of Eurasia is most clearly illustrated by the loss of Eurasia’s last outposts in the New World (the Russian sale of Alaska in 1867 and the Spanish defeat in the Caribbean in 1898) and by the failure of mighty Germany to obtain an equitable Platz an der Sonne. After its defeat in the Naval Arms Race in 1912, Germany is forced to switch from an offensive Weltpolitik to a defensive Mitteleuropapolitik: it now faces a fatal Einkreisung by an infinitely superior alliance of thalassocratic Britain and republican France plus financially-manipulated and revolutionary-infected Russia. Historically, the inevitable defeat of Germany as the champion of the European Tradition is the result of a carefully plotted ‘ambush’. The pillars of Traditionalist Eurasia are overthrown by the Versailles’ Diktat, the fire sale of the Hapsburg Empire and the establishment of the Bolshevik terror regime in the ashes of Russia. The first version of the thalassocratic-globalist ‘New World Order’ is now in place, as symbolized by the double institutions of the League of Nations in the West and the Comintern in the East (established 1919/20). The 1937-45 ‘Axis’ revolt against this New World Order, a.k.a. the ‘Second World War’, is even more hopelessly senseless than Germany’s unequal ‘war against the world’ of 1914-18. After the final destruction of the European Tradition and the European great powers during the 1940’s (France loses its great power status in 1940, Italy in 1943, Germany in 1945 and Britain - with its Indian Empire - in 1947), the mantle of Eurasian champion devolves on an eminently unlikely candidate: Stalin’s new ‘national-communist’ Russia. The thalassocratic war on this new Eurasian citadel takes on the form of a prolonged global siege: the ‘Cold War’. Exhausted and bankrupted by this four decennia long unequal struggle against the infinitely superior resources of global thalassocracy, the Soviet Union finally collapses in 1991. Francis Fukuyama can announce the ‘End of History’ and George Bush Sr. can announce the ‘New World Order’: ‘Globalia’, the borderless ‘world state’ of unlimited ‘high finance’ power and universalist ‘culture nihilism’, is born.

The French Revolution - ironically directly caused by the French state bankruptcy that followed the French naval revenge on Britain during the American Revolution (1775-83) - marks the point at which thalassocratic Modernity manages to create a substantial ‘bridgehead’ on the European continent. As a focal point of revolutionary upheaval and anti-Eurasianist geopolitics, France subsequently functions as a continental ‘wedge’ for the forces of thalassocratic Modernity all throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries.[4] The post-Napoleonic restoration of the Traditionalist Bourbons and the creation of the (proto-)Eurasianist Holy Alliance (1815) do not fundamentally alter this equation: in 1830 France relapses into revolutionary policies - by that time the Holy Alliance had already proven itself to be a ‘paper tiger’ by its failure to stem the revolutionary tide both inside and outside Europe. By then, nearly the entire New World has been lost to freemasonic liberalism, which shielded the Americas from Eurasianist intervention by the Monroe Doctrine. Slowly but steadily, the global balance of power shifted in favour of Atlanticist thalassocracy as it crept into the European heartland through escalating revolutionary contagion. In this context, Steuckers correctly points to the crucial significance of the Anglo-French rapprochement: in his view, the Crimean War (1853-56) marks the point at which the Eurasian space west of the Rhine is irretrievably lost. Some years later, Bismarck’s resurrected (Second) German Empire takes over the role as Eurasian ‘border guard’ that has been abandoned by France as it sinks into republican decadence. Germany’s Wacht am Rhein as guardian of the European Tradition begins. But as the Second Industrial Revolution combines with Modern Imperialism to create an irresistibly rising global règne de la quantité, the decline of Traditionalist Eurasia is a foregone conclusion. The global strategic weakness of Eurasia is most clearly illustrated by the loss of Eurasia’s last outposts in the New World (the Russian sale of Alaska in 1867 and the Spanish defeat in the Caribbean in 1898) and by the failure of mighty Germany to obtain an equitable Platz an der Sonne. After its defeat in the Naval Arms Race in 1912, Germany is forced to switch from an offensive Weltpolitik to a defensive Mitteleuropapolitik: it now faces a fatal Einkreisung by an infinitely superior alliance of thalassocratic Britain and republican France plus financially-manipulated and revolutionary-infected Russia. Historically, the inevitable defeat of Germany as the champion of the European Tradition is the result of a carefully plotted ‘ambush’. The pillars of Traditionalist Eurasia are overthrown by the Versailles’ Diktat, the fire sale of the Hapsburg Empire and the establishment of the Bolshevik terror regime in the ashes of Russia. The first version of the thalassocratic-globalist ‘New World Order’ is now in place, as symbolized by the double institutions of the League of Nations in the West and the Comintern in the East (established 1919/20). The 1937-45 ‘Axis’ revolt against this New World Order, a.k.a. the ‘Second World War’, is even more hopelessly senseless than Germany’s unequal ‘war against the world’ of 1914-18. After the final destruction of the European Tradition and the European great powers during the 1940’s (France loses its great power status in 1940, Italy in 1943, Germany in 1945 and Britain - with its Indian Empire - in 1947), the mantle of Eurasian champion devolves on an eminently unlikely candidate: Stalin’s new ‘national-communist’ Russia. The thalassocratic war on this new Eurasian citadel takes on the form of a prolonged global siege: the ‘Cold War’. Exhausted and bankrupted by this four decennia long unequal struggle against the infinitely superior resources of global thalassocracy, the Soviet Union finally collapses in 1991. Francis Fukuyama can announce the ‘End of History’ and George Bush Sr. can announce the ‘New World Order’: ‘Globalia’, the borderless ‘world state’ of unlimited ‘high finance’ power and universalist ‘culture nihilism’, is born.

Steuckers points to the ideological and propagandist ‘thin red line’ that can be traced through the victorious campaign of Modernist thalassocracy against Traditionalist Eurasia: the recurring theme of the leyenda negra against the ‘losers of history’. Modern history is written by ‘those who hang heroes’: when, in 1588, Catholic Spain loses its war against Protestant England (and again, in 1648, against Protestant Holland), it is immediately stigmatized as a defeated ‘Anti-Christ’ - this is the beginning of the teleological propaganda machine of ‘Whig History’.[5] When, in 1918, ‘militarist’ Germany loses its war against the ‘peace-loving’ Entente, it is immediately burdened with ‘war guilt’ clauses.[6] When, 1991, ‘unfree’ Soviet Russia loses its Cold War against the ‘Free West’, it is permanently branded as the ‘Evil Empire’.[7] The Lügenpresse of the postmodern West continues to spin the same ‘thin red line’ of propaganda policy in the contemporary geopolitical debate as it seeks to paint all remaining non-globalist international power centres with the same leyenda negra brush. When Russia’s Vladimir Putin resists globalism and culture nihilism, he is portrayed as a bloodstained ‘anti-democratic’ tyrant. When Hungary’s Viktor Orbán’s attempts to preserve a semblance of state sovereignty and ethnic cohesion for his nation, he is portrayed as an ‘illiberal’ anti-Semite. When Turkey’s Recep Erdogan reclaims Turkey’s traditional value-system and regional power status, he is portrayed as a ‘crypto-islamist’ dictator. In the same manner, all organizations and persons that resist transnational totalitarianism and ethnic replacement in the ex-‘Free West’ are systematically portrayed as ‘populist’, ‘chauvinist’ and ‘racist’. In Steuckers’ view, effective measures against indoctrination through this ‘fake history’ and ‘fake news’ mind-control strategy should have the highest possible priority within the Eurasianist movement: Il conviendrait donc de réfléchir à annuler les effets de toutes les leyendas negras, par des efforts coordonnés, à l’échelle globale, dans tous les états européens, en Iran, au sein de toutes les puissances du BRICS (p.6). [Thus, it is appropriate to give serious thought to the cancellation of the effects of all the leyendas negras through a concerted effort at a global level, for all European states as well as for Iran and all of the BRICS powers.][8]

Steuckers predicates the future of Eurasianism - more exactly the Neo-Eurasianism that is focussed on the resurrected Russian state now led by Vladimir Putin - on a possible revival of the strategic alliances that existed in the pre-1914 world: L’eurasisme, à mon sens, doit être la reprise actualisée de l’alliance autro-franco-russe du XVIIIe siècle, de la Sainte-Alliance et de l’Union des Trois Empereurs, voire une résurrection des projets d’alliance franco-germano-austro-russe... avant 1914 (p.6). [In my view, Eurasianism should be focussed on the re-actualization of projects such as the 18th Century Austro-Franco-Russian alliance, the Holy Alliance and the Three Emperors’ League or one of the many Franco-German-Austro-Russian alliance proposals that were made... before 1914.].

What is the meaning of ‘ethnicity’ within Eurasianist thought?

Nullus enim locus sine genio est

- Servius

The Traditionalist ‘hue’ of Eurasianist thought is clearly evident in its non-biodeterministic view of the categories ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’: in Eurasianism both are interpreted as predetermined - and therefore non-negotiable - bio-evolutionary constructs of a doubly biological (physical, phenotypic) and cultural (social, psychological) nature. From this perspective, every ‘nation’ constitutes a unique historical combination of physical, psychological and spiritual particularities that is expressed in various manners. These particularities include a specific ‘phenotypic bandwidth’, a specific ‘tone signal’, a specific ‘worldly footprint’ and a specific ‘transcendental niche’; in cultural history they are known as, respectively, ‘race’, ‘language’, ‘culture’ and ‘religion’ - together they may be used to ‘triangulate’ the elusive phenomenon of ‘ethnicity’ and to describe the subjective existential condition of being a ‘people’. From this perspective, ‘scientific racism’ is a contradictio in terminis: an absolutely objective ‘evolutionary measurement’ is impossible to achieve because each people is adapted to its unique biotope in a unique manner. At most, relative measurements (ranging from pre-scientific skull and nose measurements to highly scientific IQ and DNA measurements) can hope to achieve a functional description of specific bio-evolutionary adaptations: absolute standards of ‘human quality’ cannot be derived from such a description. Elements of the Traditionalist worldview that feeds the Eurasianist vision of ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’ may be traced back to Johann Herder (e.g. ‘idealist nationalism’) and Julius Evola (e.g. ‘spiritual race’). That being said, it is necessary to emphasize the fact that the Traditionalist ‘hue’ of Eurasianism is clearly essentialist: Eurasianism aims for the preservation of holistically-defined ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’ because it recognizes the intrinsic existential value of every unique element within humanity as a whole - in this sense it is diametrically opposed to the constructivist ideologies of Modernity (liberalism, socialism, communism).[9] Given this aim - which may be viewed as applying the principles of ‘environmental conservation’ to human (bio)diversity’ - Eurasianism is bound to reject interference in the state sovereignty, cultural identity and territorial integrity of the indigenous peoples found within the Eurasian ‘biotope’. Steuckers expresses this stance as follows: Mon concept d’Eurasie est synonyme d’une confédération solidaire de peuples de souche européenne qui devront, éventuellement, occuper des territoires où vivent d’autres peoples, pour des raisons essentiellement stratégiques. ...La vision ethno-différentialiste postule que les peuples non européens ne soient pas obligés de singer les Européens, de modifier leurs substrats naturels, que ce soit par fusion, par mixage ou par aliénation culturelle (p.7-8). [My concept of Eurasia is a confederative solidarity pact between all people of European descent, where necessary expanded to the occupation of territory inhabited by other peoples for reasons of vital strategic security. ...The ethno-differentialist vision[10] stipulates that the non-European peoples should not be forced into ‘aping’ the European peoples, or to modify their natural substrate through fusion, admixture or cultural alienation.]

The ‘racial’ and ‘ethnic’ aspect of Neo-Eurasianism is strictly limited to the (re-)creation of cultural-historical ‘breathing space’ for all indigenous peoples within the Eurasian space. In this regard, Steuckers points out four basic strategic principles: (1) The need to come up with a wide definition of the term ‘European’, which can include as the entire (white, ‘Caucasian’) ethnic conglomerate that can be linguistically defined as Indo-European, Finno-Ugrian, Basque and (North, South and East) Caucasian. (2) The need for a pragmatic incorporation of the indigenous Uralo-Altaic (e.g. Turcophone) peoples within a shared ‘European Home’ on the basis of voluntary ethnic segregation and limited territorial autonomy. (3) The need to create a loose institutional framework for peaceful co-existence with the four other great civilizational poles that are directly adjacent to the (Christian) Eurasian civilizational pole: (Zoroastrian) Iran, (Hinduist) India, (Confucian) China and (Shinto) Japan. It is in the natural interest of the Eurasian heartland that the civilizational expansion of these other four autonomous poles is streamlined into a north-south direction. Thus, Iran has a natural civilizational ‘mission’ across the entire Middle East, India across the entire South Asian sphere, China across entire South-East Asia and Japan across the entire Asian ‘Pacific Rim’. (4) The need for a pragmatic geopolitical alliance with all overseas peoples of European descent, especially with the overseas Anglosphere and the post-globalist United States. Such an alliance can be based on the ‘corrected’ Amer-Eurasianist Realpolitik proposed by the older Zbigniew Brzezinski and on the Archeo-Futurist ‘boreal alliance’ vision of Guillaume Faye.

Steuckers goes on to explicitly name the main opponents of the Neo-Eurasian Project: these are the various virulent forms of hyper-universalist globalism and missionary primitivism that are rooted in the psycho-historical ‘Dark Age’ regression of (Post-)Modernity. The radical-constructivist illusions that are rooted in the historical materialism of the ‘Enlightenment’ and the all-levelling barbarisms that are rooted in reactionary neo-primitivism constitute a mortal danger to all those forms of authentic collective identity that fall under the protective umbrella of Neo-Eurasianism: religion, culture, language and ethnicity. Steucker identifies missionary neo-liberalism (socio-economic atavism based on post-protestant hyper-individualism focussed on American power) and missionary islamism (socio-economic regression based on post-islamic hyper-collectivism focussed on Saudi power) as the most deadly threats. In Steuckers’ view, it is no coincidence that these two ‘missionary’ ideologies have concluded a strategic (geopolitical) alliance. But, for the first time in a generation, stress fractures are starting to appear in the double neoliberal-islamist (‘American-Saudi’) New World Order. The tentative program that is being put forward by Donald Trump’s éminence grise, Steve Bannon, point to a re-evaluation of America’s strategy of global hegemony - a re-evaluation that is prompted by the simple calculus of America’s ‘imperial overstretch’ and China’s ‘economic miracle’. In fact, Bannon’s program can be typified as broadly aligned with Steuckers’ evaluation of the effective ideological bankruptcy of American globalism: ...[I]l faudrait que l’Amérique du Nord revienne à une pensée aristotélicienne, renaissanciste, débarrassée de tous les résidus de ce puritanisme échevelé, de cette pseudo-théologie fanatique où aucun esprit d’équilibre, de pondération et d’harmonie ne souffle, pour envisager une alliance avec les puissances du Vieux Monde (p.9). [It is necessary for Nord America to return to an Aristotelian and Renaissancist worldview cleansed from all remnants of confused puritanism - the pseudo-theological fanaticism that stifles the spirit of equilibrium, mindfulness and harmony - so that it can again conceive of an alliance with the powers of the Old World.]

What is the meaning of ‘nationalism’ within Eurasianist thought?

‘The Empire Strikes Back’

Because Eurasianism not only aims at a maximum degree of sovereignty for all European peoples but also recognizes the need for a shared defence mechanism, it needs to define the precise role and function of the many different kinds of nationalism that exist next to - and against - each other within the contemporary ‘Europe of the Nations’. In this regard, Steuckers distinguishes between two diametrically opposed visions of ‘Europe’: the ‘hard’ traditional vision and the ‘soft’ modern vision. Because the ‘hard’ Tradition-inspired vision has been removed from the lived European experience for so long now - to the extent that it has even faded from the collective memory - it is important to introduce Steuckers’ analysis of the nationalist ‘Europe of the Nations’ by a short reminder of the Traditionalist vision of supra-national (i.e. natural ‘over-national’) authority. It is important to distinguish this vision from the modern reality of trans-national (i.e. artificial ‘anti-national’) forms of authority, as exemplified by the globalist ‘letter institutions’ (UN, IMF, NATO, EU etc.).

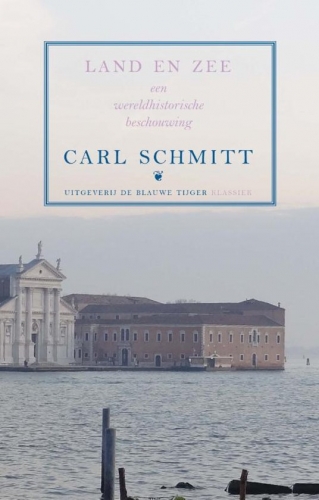

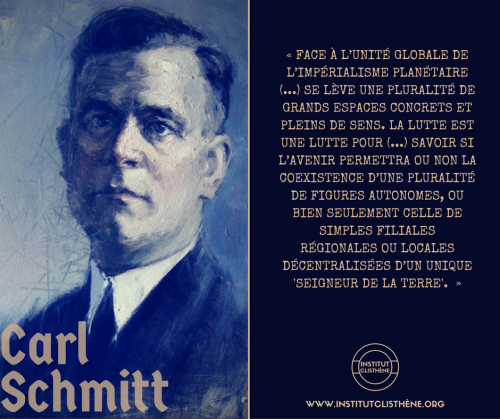

From a Traditionalist perspective, the only form of supra-national authority that is truly legitimate rests on what Carl Schmitt termed the Ernstfall, viz. the transcendentally-sanctioned Auctoritas and the charismatically-sanctioned power of Imperium that are based on a collectively recognized and collectively life-threatening clear and present danger.[11] For the Eurasianist Project this concretely means that there exists only one kind of supra-national authority that is truly legitimate and that can (temporarily) exceed that of the sovereign institutions if the European peoples, viz. the ‘emergency power’ to ward off a physical assault on the Eurasian space as a whole - and even this ‘emergency power’ can only be properly exercised if it adheres to the principle of subsidiarity to a maximum degree. In this regard, Schmitt points to the core functionality of the Traditionalist authority of the Katechon: Biblical eschatology explicitly points to the Katechon as the transcendentally legitimate ‘keeper’ of the Christendom - and thus of the entire Christian-European Tradition. From a Traditionalist perspective, every other form of trans-national ‘authority’ - whether inspired by nationalist hegemony (Napoleonic-French Europe, Hitlerian-German Europe) or by historically-materialist ideology (‘Soviet Union’, ‘European Union’) - is illegitimate. The approaching nadir of the Crisis of the Modern West, characterized by the converging emergencies of ethnic replacement, anthropogenic climate change, trans-humanist ‘technocalyps’ and hyper-matriarchal social implosion, necessitates an urgent collective recourse to the Auctoritas van de Katechon. Most urgent is the need for a common defence and counteroffensive against the barbarian invasion and colonization of Western Europe and the overseas Anglosphere: the urgent need to effectively combat the ‘mass immigration’ project that is foisted on the European peoples by globalist ideologues justifies the appointment of a new worldly Katechon as a new ‘border guard’ for the European Tradition.[12] Faute de mieux Neo-Eurasianism regards Russia, which has recently risen from the ashes of seventy years of Bolshevism and ten years of globalism, as a possible Last Katechon. Within Russia, there are signs of a socio-cultural development that point to gradual realization of this possibility: the restoration of Russian state sovereignty under Vladimir Putin, the resurrection of the Russian Orthodox Church under Patriarch Kirill and the coherent formulation of an alternative metapolitical discourse under Aleksandr Dugin. Increasingly, the anagogic direction of these developments stands in an evermore shrill contrast to the ‘katagogic’ direction of the socio-cultural development in the ‘West’ (defined as the European ‘Atlantic Rim’ plus the overseas Anglosphere).

Almost immediately after the fall of the communist dictatorship in Eastern Europe (the Soviet Union abolished itself in 1991), a globalist dictatorship was introduced in Western Europe (the European Union was established in 1992): the ‘Eastern Bloc’ was replaced by a ‘Western Bloc’. This new Western Block, characterized by an extreme anti-traditional ideology and a matriarchic-xenophile culture in which all forms of authentic authority and identity are being dissolved as in acid, is now threatening the physical survival of the European peoples in a much more direct manner than the old Eastern Bloc ever did. Whereas the Eastern Bloc insisted, at least theoretically, on an ‘anagogic’ supersession of European nationalism and on a balanced ‘brotherhood’ of separate nations, the Western Bloc insists on a physical deconstruction of the European peoples by means of anti-natalism (through social implosion) and ethnic replacement (through mass immigration). The ex-Eastern Bloc states of Central Europe that were absorbed into the Western Bloc after 2004 now recognize this difference - this is the deeper cause of the militant resistance of the Visegrad states against the Brussels Diktat of ‘open borders’. It is ironic, however, that European ‘narrow nationalism’ is actually assisting the Brussels bureaucracy in the implementation of its anti-European policy: short-sighted and artificially magnified ‘neo-nationalist’ conflicts of interest between the European peoples are distracting them from their much more substantial common interest, viz. the preservation of Western civilization. Examples of such artificial ‘conflicts’ are the north-south divide after the ‘European Sovereign Debt Crisis’ of 2010, the west-east divide after the Russian absorption of the Crimea in 2014 and the continental-insular divide after the ‘Brexit’ of 2016. In these instances, ‘narrow nationalist’ divisions are actually ‘engineered’ - and ruthlessly exploited by media propaganda - in the artificial setting of a carefully disguised but all-out globalist offensive against the greater conglomerate of all European nation-states and all European peoples together.

Almost immediately after the fall of the communist dictatorship in Eastern Europe (the Soviet Union abolished itself in 1991), a globalist dictatorship was introduced in Western Europe (the European Union was established in 1992): the ‘Eastern Bloc’ was replaced by a ‘Western Bloc’. This new Western Block, characterized by an extreme anti-traditional ideology and a matriarchic-xenophile culture in which all forms of authentic authority and identity are being dissolved as in acid, is now threatening the physical survival of the European peoples in a much more direct manner than the old Eastern Bloc ever did. Whereas the Eastern Bloc insisted, at least theoretically, on an ‘anagogic’ supersession of European nationalism and on a balanced ‘brotherhood’ of separate nations, the Western Bloc insists on a physical deconstruction of the European peoples by means of anti-natalism (through social implosion) and ethnic replacement (through mass immigration). The ex-Eastern Bloc states of Central Europe that were absorbed into the Western Bloc after 2004 now recognize this difference - this is the deeper cause of the militant resistance of the Visegrad states against the Brussels Diktat of ‘open borders’. It is ironic, however, that European ‘narrow nationalism’ is actually assisting the Brussels bureaucracy in the implementation of its anti-European policy: short-sighted and artificially magnified ‘neo-nationalist’ conflicts of interest between the European peoples are distracting them from their much more substantial common interest, viz. the preservation of Western civilization. Examples of such artificial ‘conflicts’ are the north-south divide after the ‘European Sovereign Debt Crisis’ of 2010, the west-east divide after the Russian absorption of the Crimea in 2014 and the continental-insular divide after the ‘Brexit’ of 2016. In these instances, ‘narrow nationalist’ divisions are actually ‘engineered’ - and ruthlessly exploited by media propaganda - in the artificial setting of a carefully disguised but all-out globalist offensive against the greater conglomerate of all European nation-states and all European peoples together.

Recent ‘separatist’ tendencies within existing European states (the secession of Kosovo in 2008, the Scottish independence referendum of 2014, the Catalan ‘declaration of independence’ of 2017) illustrate the acute contemporary relevance of ‘narrow nationalism’. The double burden of anachronistic international jurisprudence (‘Westphalia’: undifferentiated state sovereignty) and anachronistic territorial boundaries (‘Versailles’: arbitrary state borders) reinforces a political drift towards the ‘lowest ethnic denominator’. Steuckers points to the effect of the globalist strategy of divide et impera that operates by strengthening the modern ‘soft vision’ at the expense of the traditional ‘hard vision’ of European geopolitics. He traces the historical origins of the ‘soft vision’ to the threshold of the Modern Age, pointing out the fact that Francis I of France (r. 1515-47) was the first to obtain a modern (absolutist) sovereignty at the expense of the traditional (supra-national) higher authority of the Roman-German emperor, in casu Charles V (r 1519-56) - he was also the first European monarch to betray Europe by a non-European (Ottoman) alliance. The escalating geopolitical ‘balkanization’ of Europe - formally institutionalized in the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) - had the double effect of negating all forms of traditionally legitimate supra-national authority as well as fostering both modern-illegitimate forms of trans-national power and non-European interventions. It encourages ‘narrow nationalist’ conflicts within Europe and it deprives Europe as a whole of a shared defence mechanism: it makes Europe weak. The hard vision, based on subsidiary (layered, delegated) sovereignty finally vanishes from European Realpolitik with the collapse of its last Katechon institutions at the end of World War I (the West Roman Katechon abstractly represented by the Hapsburg Imperium and the East Roman Katechon abstractly represented by the Romanov Imperium). From that point onwards, the process of political ‘devolution’ towards ever smaller ‘nation-states’ becomes irreversible - it reaches its climax in the melt-down of some of the artificial multi-ethnic states that were ‘frozen’ during the Cold War (the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia). Thus, Europe is presently divided in over fifty - partially unrecognized - states and microstates and its centrifugal tendencies remain as strong as ever. The re-introduction of the hard vision of European geopolitics is an absolute precondition for overcoming futile and enervating ‘narrow nationalism’, for combating globalist divide-and-rule strategies and for saving the European peoples from the physical and psychological Götterdämmerung of Umvolkung (ethnic replacement) and Entfremdung (sociocultural loss of identity).

What is the Eurasianist alternative for ‘Globalia’?

Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam

- Cato Maior

To properly answer the question that heads this paragraph, a basic understanding is required of the geopolitical goals of the globalist ‘hostile elite’. To this end, Steuckers offers a helpful analysis of the most extreme representatives of the globalist ‘New World Order’ project: the ‘Neocons’ who hijacked American foreign policy in the wake of the ‘9/11’ coup d’état. Steuckers describes them as ‘reinvented trotskyists’ who are applying the principle of ‘permanent revolution’ on a global scale to maintain the ‘unipolar’ hegemony of the American superpower as a useful political and military ‘watchdog’ for their true master: the informal globalist bankers regime. There do exist, in fact, direct personal and ideological overlaps between the early-21st Century nihilist Neocons and the late-20th Century trotskyist ‘New York Intellectuals’: as early as 2006 Francis Fukuyama pointed out the fact that Neocon ideology is dedicated to the leninist-trotskyist principle of ‘accelerating history’ by the ruthless application of brute force and calculated crime. The unipolar geopolitical strategy of the Neocons is characterized by a deliberate use of every conceivable means of ‘trick and terror’ to achieve the destabilization of all other (potential) power poles across the globe. American superpower may not be sufficiently strong to directly ‘rule the world’, but it provides a perfect instrument to degrade all other power poles by means of a carefully calibrated combination of economic manipulation, political subversion and military intervention. Thus, ‘Shock Doctrine Disaster Capitalism’ is the Neocons’ weapon of choice for achieving a worldwide consumerist culture (‘McWorld’) and a global labour division (‘free trade flat world’). Similarly, ‘Flower/Colour Revolution’ (‘soft power’ and ‘black ops’ socio-political subversion) is their standard weapon for introducing corrupt - and therefore easily manipulated - ‘democratic’ practices in recalcitrant states (e.g. Georgia’s ‘Rose Revolution’ of 2003, Ukraine’s ‘Orange Revolution’ of 2004 and Egypt’s ‘Lotus Revolution’ of 2011). Finally, ‘Regime Change’ is their weapon of last resort for the forcible removal of hopelessly delinquent ‘dictators’ (e.g. Manuel Noriega 1989, Saddam Hussayn 2003, Muammar Ghadaffi 2011).

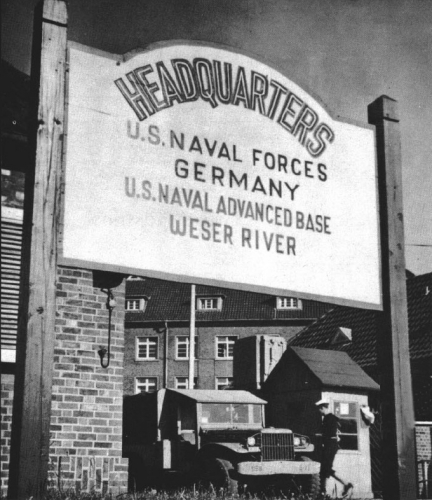

Even if the most visible application of the Neocon arsenal takes place outside of the West and outside of the Western-allied world (flexibly defined as an malleable Orwellian ‘International Community’), the strategy of the Neocon trotskyists vis-à-vis Europe is basically the same. In this regard, Steuckers points to the crucial role of Germany: to maintain their New World Order it is vitally important for the Neocons to control and restrain Europe’s geographically, demographically and economically dominant nation-state. The military destruction of the Third Reich was followed by permanent military occupation, systematic ‘denazification’, pacifist indoctrination and permanent tributary status (Wiedergutmachung, Euro monetary union, ‘development aid’). The Neocons ...considèrent l’Europe comme un espace neutralisée, gouverné par des pitres sans envergure, un espace émasculé que l’on peut piller à mieux mieux... (p.14) [...regard Europe as a neutralized space, nominally ruled by clown without any real authority, a castrated region that can be plundered at will]. But still, there remains a ‘German danger’ in the heart of Europe: despite its slavish economic tribute, its humble foreign policy and its subservient political correctness, Germany remains a permanent potential threat to the Neocons’ unipolar globalism due to its unmatched economic productivity, its remarkable social cohesion and its indomitable intellectual tradition. Neither the stupendous cost of the Wiedervereinigung, nor the monstrous expense of the Euro, nor the colossal weight of the ‘Eurozone Crisis’ has been able to substantially slow down Germany’s socio-economic powerhouse. It is with this reality in mind that the globalist strategy of Umvolkung can be understood: only the physical replacement of the German people offers a realistic ‘hope’ for the permanent elimination of the ‘German danger’. The fact that this program of wholesale ethnic replacement - historically unprecedented in scale - is conceivable at all can only be properly understood against the specific background of the deep psycho-historical trauma and the decades’ long politically correct preconditioning of Germany. The contemporary reality of the physical violation of Germany - presently realized through taḥarruš jamā‘ī en jihād bi-ssayf (systematic rape en ritual slaughter) - can only be truly understood in view of its preceding psychological violation.[13]

Even if the most visible application of the Neocon arsenal takes place outside of the West and outside of the Western-allied world (flexibly defined as an malleable Orwellian ‘International Community’), the strategy of the Neocon trotskyists vis-à-vis Europe is basically the same. In this regard, Steuckers points to the crucial role of Germany: to maintain their New World Order it is vitally important for the Neocons to control and restrain Europe’s geographically, demographically and economically dominant nation-state. The military destruction of the Third Reich was followed by permanent military occupation, systematic ‘denazification’, pacifist indoctrination and permanent tributary status (Wiedergutmachung, Euro monetary union, ‘development aid’). The Neocons ...considèrent l’Europe comme un espace neutralisée, gouverné par des pitres sans envergure, un espace émasculé que l’on peut piller à mieux mieux... (p.14) [...regard Europe as a neutralized space, nominally ruled by clown without any real authority, a castrated region that can be plundered at will]. But still, there remains a ‘German danger’ in the heart of Europe: despite its slavish economic tribute, its humble foreign policy and its subservient political correctness, Germany remains a permanent potential threat to the Neocons’ unipolar globalism due to its unmatched economic productivity, its remarkable social cohesion and its indomitable intellectual tradition. Neither the stupendous cost of the Wiedervereinigung, nor the monstrous expense of the Euro, nor the colossal weight of the ‘Eurozone Crisis’ has been able to substantially slow down Germany’s socio-economic powerhouse. It is with this reality in mind that the globalist strategy of Umvolkung can be understood: only the physical replacement of the German people offers a realistic ‘hope’ for the permanent elimination of the ‘German danger’. The fact that this program of wholesale ethnic replacement - historically unprecedented in scale - is conceivable at all can only be properly understood against the specific background of the deep psycho-historical trauma and the decades’ long politically correct preconditioning of Germany. The contemporary reality of the physical violation of Germany - presently realized through taḥarruš jamā‘ī en jihād bi-ssayf (systematic rape en ritual slaughter) - can only be truly understood in view of its preceding psychological violation.[13]

The systematic globalist strategy of Deutschland ad acta legen[14] provides an eerie reminder of Rome’s long-term strategy vis-à-vis its archenemy Carthage: it is useful for contemporary Europeans who have sunk into urban-hedonist stasis to recall this lesson of history and to revisit the harsh power political mechanisms that determine the course of human history. Similar to Carthage after the First Punic War (264-241 BC), Germany was subjected to grotesque territorial amputation and top-heavy reparation payments after the First World War - in both cases this pressure led to international weakness and domestic strife (loss of naval power, diplomatic prestige and political stability). In both cases, the crisis that followed defeat finally caused a remarkable ‘nationalist’ rebirth: in Carthage, this took the form of the ‘Barcid Empire’ and in Germany, this took the form of the Third Reich. In both cases, this rebirth led to a renewed confrontation with the implacably envious archenemy. Similar to how Rome found a spurious but convenient casus belli against Carthage in ‘Saguntum’, Britain and France proceeded against Germany on the basis of ‘Danzig’. Similar to the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), the Second World War represents the dramatic height of a deeply existential confrontation in which the loser was inevitably consigned to historiographical hell, representing an archetypal and semi-metaphysical ‘Absolute Evil’. Carthaginian war leader Hannibal Barca shook Rome’s existential foundations and, thus, Roman thinkers such as Livy and Cicero had to describe him as the most monstrous threat that Roman civilization had ever faced: to them, Hannibal was the reincarnation of barbarian cruelty and the demonic abyss. Similar to how the Latin proverb Hannibal ante portas came to express Rome’s existential fears, the name of German war leader Adolf Hitler came to express the existential Angst of the post-war Western world (reductio ad hitlerem...). Similar to the Second Punic War, the Second World War ended with even greater territorial amputations and even more monstrous reparation payments. Similar to Carthage after the Second Punic War, Germany came under direct military, political and economic tutelage of the victors of the Second World War: to them, Germany’s vassal status constitutes a permanent ‘right of conquest’. In both cases, the victor regards the defeated archenemy as a permanent source of tribute, entitled to no more than a limited degree of domestic autonomy - to the victor, the defeated archenemy can never be allowed to rise to full equality again. Even so, to the victor, the combined physical survival and socio-economic resilience of the defeated enemy represents a latent but permanent source of fear and insecurity. This explains Rome’s policy of grotesque interference in the internal affairs of the Carthaginian rump-state in the aftermath of the Second Punic War - a phenomenon that is eerily reflected in the systematic globalist policy vis-à-vis the German rump-state since the Second World War. In both cases the natural resources, the high productivity and the cultural other-ness of the defeated enemy remain a constant source of ambition, envy and fear: ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam is the dominant sentiment. Similar to how independent Carthage had to die for Roman world power to live, Germany has to disappear for globalist world power to become permanent. And so, finally, after having exploited, manipulated and deceived Carthage to the utmost - to the point of forcing it to hand over it best arms and best people - Rome drops its mask: it presents an open demand for the old and rich trading port to dismantle itself, to burn itself and to ‘replace’ itself by moving inland and reinventing itself as an agricultural colony. Confronted with this final demand after decades of self-enforced and self-abasing ‘appeasement’, Carthage finally finds the courage to stand up and die with honour - and in freedom. The Third Punic War (149-146 BC) is not so much a war as an execution: the outcome of the struggle between all-powerful Rome and death-bound Carthage is a foregone conclusion. After a heroic death struggle, Carthage is annihilated: the burnt city is levelled to the ground, its decimated populace is sold into slavery and its sequestered lands were sowed with salt. It is - just - conceivable that Germany would finally, if confronted with an open globalist demand for self-annihilation through total ethnic replacement, opt for an Ende mit Schrecken instead of a Schrecken ohne Ende.[15] The more realistic scenario, however, is the full materialization of the spectre that is already now haunting Europe: an ‘ex-German’ psycho-historical and geo-political ‘black hole’ that is swallowing up the hole of (Western) Europe in a historically unparalleled process of sadomasochistic self-annihilation. It is this trajectory of gradual self-destruction that Frau Merkel is pursuing for Germany as a palliative alternative for the Wagnerian heroic war-to-the-death that was waged by Carthage. Perhaps she can not even be blamed for her choice: who knows what terrifying vengeance the German people would wreak if they would wake up from the soothing sedatives that ‘nurse Merkel’ is administering in the run-up to their ‘voluntary’ euthanasia?

Against this background, the full significance of Steuckers’ geopolitical analysis sinks in: L’Europe-croupion, que nous avons devant les yeux, est une victime consentante de la globalisation voulue par l’hegemon américain. ...En ce sens, l’Europe actuelle, sans ‘épine dorsale’, est effectivement soumise aux diktats de la haute finance internationale (p.17). [The ‘rump-Europe’ that we presently see before our eyes is the willing victim of the globalism that is imposed by American hegemony. ...In this sense, the present ‘spineless’ Europe is effectively subject to the dictates of international ‘high finance’]. Steuckers gives a clear analysis of what is required to escape from the clutches of the globalist bankers’ regime: nothing less than a new European Renaissance, based on a restoration of maximal economic autarky (systematic re-industrialization, strategic trade treaties, de-privatized monetary supply), a re-introduction of socio-economically balanced forms of ordo-liberalism (Rhineland Model, Keysenian Socialism) and a geopolitical re-orientation towards multipolarity (Eurasian Confederacy, Boreal Alliance). A new geopolitical course in the face of the globalist storm requires not only a unified European effort but also a shrewd European navigation strategy between new geopolitical power poles: ....[P]our se dégager des tutelles exogènes... [l’Europe faut] privilégier les rapports euro-BRICS ou euro-Shanghaï, de façon à nous dégager des étaux de propagande médiatique américaine et du banksterisme de Wall Street, dans lesquels nous étouffons. La multipolarité pourrait nous donner l’occasion de rejouer une carte contestatrice... en matière de politique extérieure (p.18). [To liberate itself from alien rule... [Europe must] prioritize Euro-BRICS or Euro-Shanghai,[16] so that we can free ourselves from the vice of American media propaganda and Wall Street banksterism in which we are currently suffocating. Multipolarity provides us with a means to play a strong hand... in the field of international politics.]

Against this background, the full significance of Steuckers’ geopolitical analysis sinks in: L’Europe-croupion, que nous avons devant les yeux, est une victime consentante de la globalisation voulue par l’hegemon américain. ...En ce sens, l’Europe actuelle, sans ‘épine dorsale’, est effectivement soumise aux diktats de la haute finance internationale (p.17). [The ‘rump-Europe’ that we presently see before our eyes is the willing victim of the globalism that is imposed by American hegemony. ...In this sense, the present ‘spineless’ Europe is effectively subject to the dictates of international ‘high finance’]. Steuckers gives a clear analysis of what is required to escape from the clutches of the globalist bankers’ regime: nothing less than a new European Renaissance, based on a restoration of maximal economic autarky (systematic re-industrialization, strategic trade treaties, de-privatized monetary supply), a re-introduction of socio-economically balanced forms of ordo-liberalism (Rhineland Model, Keysenian Socialism) and a geopolitical re-orientation towards multipolarity (Eurasian Confederacy, Boreal Alliance). A new geopolitical course in the face of the globalist storm requires not only a unified European effort but also a shrewd European navigation strategy between new geopolitical power poles: ....[P]our se dégager des tutelles exogènes... [l’Europe faut] privilégier les rapports euro-BRICS ou euro-Shanghaï, de façon à nous dégager des étaux de propagande médiatique américaine et du banksterisme de Wall Street, dans lesquels nous étouffons. La multipolarité pourrait nous donner l’occasion de rejouer une carte contestatrice... en matière de politique extérieure (p.18). [To liberate itself from alien rule... [Europe must] prioritize Euro-BRICS or Euro-Shanghai,[16] so that we can free ourselves from the vice of American media propaganda and Wall Street banksterism in which we are currently suffocating. Multipolarity provides us with a means to play a strong hand... in the field of international politics.]

What is the Eurasianist perspective on the globalist program of

‘ethnic replacement’?

La vérité, l'âpre vérité

- Danton

Steuckers grasps the fundamental functionality of the globalist policy of ‘ethnic replacement’, or what he terms the ‘Great Replacement’: it constitutes a geopolitical instrument that serves to permanently weaken the European geopolitical power pole by drowning Europe in the economic and social crises that are the inevitable side-effects of artificially created overpopulation and radically unnatural ethnic ‘diversity’ (straining infrastructure, lowering economic productivity, undermining the rule of law, destroying social cohesion). He points to the simple material interests that are served by the ruthless project of ethnic replacement: Le néo-libéralisme en place est principalement une forme de capitalisme financier, et non industriel et patrimonial, qui a misé sur le court terme, la spéculation, la titrisation, la dollarisation, plutôt que sure les investissements, la recherche et le développement, le longe terme, la consolidation lente et précise des acquis, etc. ...[C’est] une idéologie fumeuse, inapplicable car irréelle... (p.19-20). [Primarily, the neo-liberal order can be understood as a form of finance capitalism - non-industrial and non-patrimonial capitalism - that ‘banks’ on short-term profit through [barely regulated] speculation, security schemes and dollarization instead of long-term gains through investment, research, development and slow and gradual capital consolidation etc. ...[It is] a nebulous ideology that does not work because it is unrealistic...] Thus, in Steuckers’ view, neo-liberalism is effectively a ‘smokescreen’ to hide the ‘Ponzi scheme’ of short-sighted financial piracy on a global scale.

Steuckers’ analysis of the ‘Great Replacement’ is especially interesting in the attention that he pays to its inhuman consequences for the millions of ‘migrants’ who have recently been brought over to Europe from Asia and Africa through globalist policies. He points to the fact that these new ‘illegals’ tend to be reduced to effective ‘slavery’, falling victim to countless forms of bestial exploitation. Les flux hétérogènes, différents des premières vagues migratoires légales vers l’Europe, génèrent, de par leur illégalité, une exploitation cruelle, assimilable à une forme d’esclavage, n’épargnant des mineurs d’âge (50% des nouveaux esclaves !) et basculant largement dans une prostitution incontrôlable. A laquelle s’ajoutent aussi les trafics [de drogues et] d’organes. Cette ‘économie’ parallèle contribue à corrompre les services de police et de justice. ...Tous ces problèmes horribles, inouïs, et le sort cruel des exploités, des enfants réduits à une prostitution incontrôlée, les pauvres hères à qui on achète les organes, les travailleurs sans protection qu’on oblige à effectuer des travaux dangereux ne font pas sourciller les faux humanistes, qui se donnent bonne conscience en défendant les ‘sans papiers’ mais qui sont, par là même, les complices évidents des mafieux... Ceux-ci peuvent ainsi tranquillement poursuivre leurs activités lucratives : en tant qu’idiots utiles, les humanistes... sont complices et donc coupable, coauteurs, des crimes commis contre ces pauvres déracinés sans protection... Nos angélistes aux discours tout de mièvrerie sont donc complices des forfaits commis, au même titre que les proxénètes, les négriers et les trafiquants. Sans la mobilisation des ‘bonnes consciences, ces derniers ne pourraient pas aussi aisément poursuivre leurs menées criminelles (p.20-1). [The recent heterogeneous migration streams differ from the earlier waves of legal immigration into Europe: through their illegality, they generate a cruel exploitation that leads to a new form of slavery which does not even spare minors (who make up half of the new slave population!) as they fall victim to uncontrollable prostitution. Added to this problem should be the trade in drugs and organs. This ‘parallel economy’ also corrupts the police apparatus and judicial systems... These terrible, unimaginable problems and the cruel fate of the exploited illegals, the children that end up in uncontrolled prostitution, the poor wretches that are selling their organs, the unprotected day-labourers that are forced into dangerous work - these problems are ignored by the fake ‘humanists’ that are showing off their ‘clean consciousnesses’ when they are defending the ‘undocumented’, but who are really accomplices to criminal gangs. These crime syndicates are allowed to continue their profitable activities undisturbed - as ‘useful idiots’ these humanists... are effectively accessories to crime: they are facilitating crimes against poor and deracinated people that are lacking in basic protection. Thus, our preachers of the ‘humanist’ discourse of fake concern are guilty as accessories to the crimes that are committed by pimps, slaveholders and human traffickers. Without the ‘humanist’ mobilization of the ‘clean consciousnesses’ these criminals would not be able to do their criminal handiwork with such ease.]

Steuckers’ ruthless analysis of the reprehensible pseudo-humanism of the ‘Social Justice Warrior’ activists and Gutmensch intelligentsia provides an important supplement to the growing public understanding of the direct interests that are served by the continuation of the globalist ‘Great Replacement’ strategy. In this regard, Steuckers’ analysis may be considered as the final intellectual nail in the coffin of the bankrupt discourse of ‘open borders.[17]

What is the Eurasianist diagnosis of Western Postmodernity?

Today we are not witnessing a crisis of civilization, but a wake around its corpse

- Nicolás Gómez Dávila

Steuckers interprets the existential reality of the contemporary West from the perspective of what Traditionalism terms the ‘Crisis of the Modern West’. He points to the absurdist - even ‘idiocratic’ - aspects of the unprecedented political degradation that can only be understood as deliberately engineered. From this perspective, the great majority of Western politicians are no more than insignificant connards et... connasses... qui titubent d’une corruption à l’autre, pour chavirer ensuite dans une autre perversité [‘cucks’ and ‘queenies’ that fall into one corruption after another, only to finally sink into yet some other perversity]. The Western ‘intelligentsia’ are nothing but festivistes écervelés qui se donnent... l’étiquette d’‘humanistes’ [brain-dead party-goers that have the temerity to call themselves ‘humanists’]. To Steuckers, the entire postmodern political enterprise is nothing but technocratisme sans épaisseur éthique [technocracy without ethical substance], led by une série de politiciens sans envergure [et] sans scrupule [a series of politicians without vision and scruples], slipping into [une] absence d’éthique dans le pôle politique qui... provoqu[e] l’implosion du pays [an ethical-political void that ends in the implosion of the nation]. The result is a déliquescence totale [complete dissolution] of state sovereignty, legal order, ethnic identity and social cohesion. In Steuckers’ estimation, France represents the European ‘ground zero’ of the postmodern globalist ‘deconstructive’ process: ...la France, depuis Sarközy et Hollande, n’est plus que la caricature d’elle-même, et la négation de sa propre originalité politico-diplomatique gaullienne... (p.24) [...since Sarkozy and Hollande, France is nothing but a caricature shadow of its former self, an inverted perversion of its Gaullist political and diplomatic original].

In the educational sphere, Steuckers notices clear signs of terminal cultural degeneracy, hastened by misapplied modern technology and resulting in démence digitale [digital dementia], characterized by a combined decline in intellectual stamina, attention spans and social skills. [L]’effondrement du niveau, où le prof doit se mettre au niveau des élèves et capter leur attention no matter what et la négligence des branches littéraires, artistiques, et musicales, qui permettent à l’enfant de tenir compte d’autrui, font basculer les nouvelles générations dans une déhumanisation problématique... (p.26). [The decline in educational standards, which now stipulate that the teacher must seek to ‘level’ with his pupils - no matter what - in order to gain their attention, and the neglect of literature, art and music - fields that allow youngsters to practice altruism - are hurtling new generations into an abyss of dehumanization...] The psycho-social impact of this educational degeneracy causes an acceleration in the ‘psychiatrization’ of Western society as a whole. In this regard, Steuckers points to the results of recent research in Belgium: [Les spécialistes voient] disparaître toute forme de ‘normalité’ et glisser nos populations vers ce qu’il[s] appelle[nt], en jargon de psychiatrie, le borderline, la ‘limite’ acceptable pour tout comportement social intégré, une borderline que de plus en plus de citoyens franchisent malheureusement pour basculer dans une forme plus ou moins douce, plus ou moins dangereuse de folie : en Belgique , 25% de la population est en ‘traitement’, 10% ingurgitent des antidépresseurs, de 2005 à 2009 le nombre d’enfants et d’adolescents contraints de prendre de la ritaline a doublé rien qu’en Flandre ; en 2007, la Flandre est le deuxième pays sur las liste en Europe quant au nombre de suicides... (p.26) [Among the general population, specialists are noticing the disappearance of ‘normality’ and a downward trend that is approaching what is known in the psychiatric profession as the ‘borderline’, i.e. the critical minimum level that is acceptable for socially adjusted behaviour - a ‘borderline’ that is breached by increasing numbers of citizens, resulting in more or less ‘soft’ as well as more or less dangerous forms of madness.

Thus, in Belgium 25% of the population is ‘in treatment’, 10% uses antidepressants and the number of children and adolescents that is forced to take ritaline in the region of Flanders alone has doubled between 2005 and 2009 and Flanders is now the second highest listed European region in terms of suicide frequency...] It should be added, that in the northern regions of the Low Countries the same trend is perhaps even more pronounced: the Dutch public sphere is now characterized by infantile regression, narcissist aggression and commercially-sponsored ‘idiocracy’ (phenomena promoted by television ‘celebrities’ such as ‘motivation coach’ Emile Ratelband, ‘model personality’ Paul de Leeuw and ‘morality anaesthetist’ Jeroen Pauw).

Thus, in Belgium 25% of the population is ‘in treatment’, 10% uses antidepressants and the number of children and adolescents that is forced to take ritaline in the region of Flanders alone has doubled between 2005 and 2009 and Flanders is now the second highest listed European region in terms of suicide frequency...] It should be added, that in the northern regions of the Low Countries the same trend is perhaps even more pronounced: the Dutch public sphere is now characterized by infantile regression, narcissist aggression and commercially-sponsored ‘idiocracy’ (phenomena promoted by television ‘celebrities’ such as ‘motivation coach’ Emile Ratelband, ‘model personality’ Paul de Leeuw and ‘morality anaesthetist’ Jeroen Pauw).

Characteristic for the psycho-social implosion of the postmodern West is a radical loss of all authentic forms of traditional identity (ethnicity, religion, birth caste, age cohort, gender, personal vocation). In this regard, Steuckers points to the clear link between the consistently deliberate ‘deconstruction’ of identity and actualized insanity: Sans identité, sans tradition, sans ‘centre’ intérieur, on devient fou... Ceux qui nous contrarient au nom de leurs chimères et leurs délires, sont, par voie de conséquence, sans trop solliciter les faits, des fous qui veulent précipiter leurs contemporains au-delà de la borderline... (p.27) [Without identity, without tradition, without inner ‘core’, people become unstable and insane... Without exaggeration, it can be stated that those who fight us in the name of their delusions and illusions are truly insane: they are madmen, driving their contemporaries across the ‘borderline’].

What is the Eurasianist prognosis for Western Postmodernity?

‘The End of the Affair’

#

Steuckers is of the opinion that the structural lack of a substantive patriotic-identitarian political opposition to the globalist ‘hostile elite’ of Europe is the result of a fatal combination of personal feuds within its leadership, politically opportunistic islamophobia (which confuses the ideology of ‘islamicism’ - Wahhabism and Salafism - with ‘Islam’ as Tradition) and short-sighted definitions of (narrow) nationalist interests. The tendency towards (hyper-)nationalist Alleingang that marks recent European history - and which still divides the European nations - is facilitating the anti-European globalist project. In this regard, Steuckers points to the great value of the alternative vision of Eurasianism: only a confederative activation of a Eurasian ‘imperial bloc’ of sovereign states can protect the peoples of Europe against the globalist ‘thalassocracy’ that is based on the Trans-Atlantic/Anglo-Saxon axis. The next logical step would be the neutralization of globalism on the basis of a ‘boreal alliance’ between the Eurasian bloc and the overseas peoples of European descent.

In the final analysis, Steuckers is not optimistic regarding the chances of a short-term translation of the metapolitical vision of Eurasianism into a real-world project. In his view, the build-up of an alternative network of coordinating metapolitical institutions is an absolute precondition for a successful challenge to the politically-correct ‘hostile elite’ that now controls Europe’s establishment universities, media and think tanks. Only such an alternative network can organize a coordinated strategy of pinpricks (debates, demonstrations, electoral preparation). It should be added that stable material facilities (legal assistance, labour union funding, professional security facilities) are absolute preconditions for any viable political and activist strategy of peaceful and legitimate civic resistance.

Steuckers predicts that the globalist New World Order and its foundational soixante-huitard discourse of neo-liberalism and cultural marxism will eventually collapse, but only after a total collapse of Western civilization in a catastrophe of unprecedented proportions. He assumes that the West has to drink its cup of ‘constructivism’ - the heaven-storming delusion of hyper-humanist absolute and universal ‘freedom’ and ‘equality’ - to its last bitter dregs. The utopian ‘imagine’ dreams of the soixante-huitards - the angelic reveries of ‘progress’ and ‘constructability’ that hide the actual practices of the demonically possessed babyboomers - will become real-life nightmares for the next generations: these will include the Asiatic and African assault of Gog and Magog on the European ‘Camp of the Saints’ and the ‘Zombie Apocalypse’ of extreme-matriarchical social implosion.[18] Selon l’adage: qui veut faire l’ange, fait la bête... Les négateurs de balises et de limites, qui voulaient tout bousculer au nom du ‘progrès’ (qu’ils imaginent au-delà de tout empirisme), vont provoquer une crise qui rendra leurs rêves totalement impossibles pour au moins une dizaine de générations, sauf si nous connaissons l’implosion totale et définitive... Quant aux solutions que nous pourrions apporter, elles sont nulles car le système a bétonné toute critique : il voulait poursuivre sa logique, sans accepter le moindre correctif démocratique, en croyant que tout trouverait une solution. Ce calcul s’est avéré faux. Archifaux. Donc tout va s’éffondrer. Devant notre lucidité. Nous rirons de la déconfiture de nos adversaires mais nous pleurerons amèrement sur les malheurs de nos peuples (p.23). [According to the adage that ‘who wants to play the angel will play the beast’... Those that ignore the traffic signs and speed limits [of civilization] and that overthrow the established order in the name of ‘progress’ (those that thought they are exempt from the rules of empiricism) will unleash a crisis that will render their dreams totally impossible for at least ten generation - unless we will actually face a total and final implosion of [Western] civilization... With regard to the solutions that we may propose: they are utterly worthless because the system voids every form of constructive criticism. Thus, the system will have to fully complete the cycle of its own [destructive] logic - it is unable to cope with even the tiniest dose of democratic correction because it is based on the assumption that there exists a ‘constructivist’ solution to all problems. This calculation has proven to be not just faulty, but dead wrong. And so everything will collapse - in front of our very eyes. We will enjoy the total defeat of our enemies, but we will bitterly weep over the misfortune of our peoples.]

Coda

Despite the disputed validity of Fichtean-Hegelian dialectic model (thesis-antithesis-synthesis) in pure philosophy, it remains valuable as a heuristic tool in the philosophically inspired culture sciences. Projected on European history, it sheds light on cyclical patterns of punctus contra punctum, patterns that are consistently followed by a sublime recapitulation. A ‘Faustian’ element of self-surpassing resurrection becomes visible - not only in the heathen-heroic half but also in the Christian-ascetic half of the European Tradition. Thus, it is only fitting that le Rouge et le Noir ends on a note that does justice to both:

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

Dabei will ich verbleiben.

Es mag mich auf die rauhe Bahn

Not, Tod und Elend treiben.

So wird Got mich

Ganz väterlich

In Seinen Armen halten:

Drum lass ich Ihn nur walten.

[What God does, is well done,

I will cling to this.

Along the harsh path

Trouble, death and misery may drive me.

Yet God will,

Just like a father,

Hold me in His arms:

Therefore I let Him alone rule.]

- BWV 12

Glossary

|

Ethic Business

|

ideologically: the neo-liberal sponsorship of diaspora economies;

economically: ‘shadow economies’ of multicultural ‘parallel societies that are structurally exempted from taxation, labour legislation and judicial oversight;[19]

|

|

Festivism

|