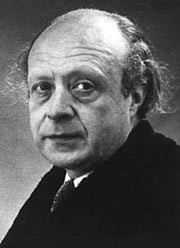

Gabriele D’Annunzio the Abruzzese

Self-proclaimed “Superman” Gabriele D’Annunzio (Photo by New York Scugnizzo)

“In men of the highest character and noblest genius there is to be found an insatiable desire for honor, command, power and glory.”

– Cicero: De Oficiis, I, 78 B.C.

The end of World War I witnessed the breakup of three of the great royal dynasties of Europe. The Hohenzollern Empire of Germany, the Hapsburg Empire of Austria-Hungary and the Romanov Empire of Russia all went the way of the Imperium Romanum before them…into the misty and romanticized pages of history. In their places were created various new geopolitical entities ranging from ethno-states like Poland to multi-national states like Czechoslovakia. With some notable exceptions (like Yugoslavia) the new governments were republics.

Centuries of authoritarian, monarchial rule plus the exorbitant costs of the war left the new crop of leaders ill-equipped to deal with the problems afflicting their respective societies. Soon a wave of demagogues, strongmen and tinpot dictators would enter the picture, attempting to carve out a legacy for themselves in the ruins of postwar Europe.

In Hungary the Bolshevik revolutionary Béla Kun (née Cohn Béla) established a brutal, short-lived Communist regime (1919) before being overthrown in a disastrous war with Romania. He fled to the nascent Soviet Union where he lived, and continued to brutalize, until he was executed under Stalin’s orders in 1938 “…because he knew too much.” Kun’s brief reign was ironically instrumental in subsequently moving Hungarian politics far to the Right.

In one of the more laughable episodes of this period, on March 13th, 1920 a group of 5,000 Freikorps (German paramilitary volunteers) led by a man named Hermann Ehrhardt seized control of the city of Berlin, drove out the Weimar government, and installed a nondescript fellow by the name of Wolfgang Kapp as figurehead ‘Chancellor’. A group of rightists led by one General Walther von Luëttwitz was the real power behind the throne.

Kapp, a bespectacled bureaucrat and journalist, lacked the charisma to make a convincing frontman. Most of the other Freikorps and military commanders as well as conservative politicians refused to have anything to do with him or his “government”. Four days later the whole scheme fell apart when the Weimar Cabinet called for a general strike and Kapp fled to Sweden. The schlemiel died of cancer two years later while in German custody in Leipzig.

The only happening during the so-called “Kapp Putsch” worth noting was the effect a singular, harsh incident associated with it (the shooting of a rambunctious, small boy by several Freikorps troops) would have on an eyewitness: a young Austrian veteran of the German Army by the name of Adolf Hitler. Several years later in his book Mein Kampf he would remark it was his first lesson in the use of force to rule the masses.

While its monarchy survived the war, Italy was not immune to the intrigues of demagogues. One, in fact, would eventually seize power in 1922. Four years later he would proclaim himself dictator while keeping the King around as a figurehead. His name was Benito Mussolini. As Il Duce he would march Italy nearly to its ruin in World War II. Before all this happened, however, he would have to contend with another forceful personality who very nearly ‘stole his thunder’. Though Mussolini won the contest, he was nonetheless profoundly influenced by this most remarkable individual whose biography is studied to this day by those fascinated with the lives of “those who dare”.

Place of birth in Pescara

(Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Gabriele D’Annunzio was born on March 12th, 1863 in the town of Pescara, Abruzzi. Just a couple of years earlier the region had been part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies before its conquest by Giuseppe Garibaldi. Some controversy apparently exists among historians as to D’Annunzio’s birth name. His father, Francesco Paolo Rapagnetta, had been adopted at the age of 13 by a childless uncle named Antonio D’Annunzio. He was raised with the surname Rapagnetta-D’Annunzio. In 1858 he married Luisa De Benedictis, by whom he had five children – three girls and two boys. According to Professor John Woodhouse (Fiat-Serena Prof. of Italian Studies, Univ. of Oxford), at the time of Gabriele’s baptism Rapagnetta had been dropped and the elder boy was officially registered as Gabriele D’Annunzio. Later in his life he would take to writing his surname as “d’Annunzio” to give it a more noble air.

Francesco Paolo had inherited half of his uncle’s fortune and as a result Gabriele and his siblings grew up fairly well off. His father, however, was a notorious drinker and womanizer who kept a string of mistresses. This caused no small amount of ill feeling between father and son. The level of dysfunctional feelings in the D’Annunzio family household was revealed when Gabriele refused to travel a short distance to be with his father before he died. After his father’s death, Gabriele realized the family had been saddled with heavy debts, forcing him to sell the D’Annunzio country home.

Gabriele D’Annunzio’s talents as a writer, as well as his disregard for personal danger, were recognized early in his life. An oft-repeated tale goes that a local fisherman had once given the boisterous lad a mussel to eat. In trying to pry it open he accidentally stabbed himself in the left thumb, bleeding profusely. Instead of running home to his mother for aid, he first ate the mollusk before binding the wound himself.

Originally tutored at home, at the age of 11 his father sent him to a prestigious boarding school, the Collegio Cicognini, in Prato, Tuscany. It must have made quite an impression on young Gabriele as years later he would describe this place as “…a plantation made in the images of the second Circle [of Dante’s Inferno], reducing the most vivacious of human saplings to ‘dried twigs with poison’. Oddly, he would later send both of his sons there when they were old enough.

D’Annunzio’s first brush with fame came in 1879 when he wrote and later published a small collection of 30 poems he entitled Primo vere. The poetry was written in the neo-Latin style of the great Tuscan poet (and future Nobel laureate) Giosuè Carducci. Against the rules of the Collegio Cicognini, he sent a complimentary copy of the book to Giuseppe Chiarini, one of Italy’s leading critics, who gave the book a mostly favorable review in the influential newspaper Il fanfulla della domenica.

Veiled bust of Eleonora Druse

(Photo by New York Scugnizzo)

It was also during his adolescent phase D’Annunzio discovered his fascination with, and his power over, women. He was known to have had at least several passionate affairs with females while still a teenager. Given his physique, this was certainly strange, for Gabriele D’Annunzio stood less than 5’6” tall, was slightly built, and had teeth that would make an Englishman envious! Yet despite this and the fact he would bald early in life, he was never lacking for female company.

In 1881 he entered l’Universita di Roma La Sapienza where he aggressively pursued a literary career by joining various literary groups and writing articles for a number of local newspapers. A year later he published his second volume of poetry, Canto novo, which illustrated his break with the austerity of Carducci’s style by its sensuality and exultation of nature. Some of the 63 poems in the book dealt with the poet’s love for the landscape of his native Abruzzi.

Shortly after this he published Terra Vergine (It: Virgin Land), a collection of short stories dealing with the hardships of peasant life in his native Abruzzi. It was inspired by the pen of noted Sicilian writer Giovanni Verga, who achieved fame by his tales of the grinding poverty in his own native Sicily. For this some accused D’Annunzio of copying Verga’s ideas and plots. Most, though, recognized the originality of D’Annunzio’s work, especially his penchant for the shocking and grotesque. This contrasted with Verga’s use of pathos to arouse sympathy in the reader. Their writings were similar only in the subject matter.

When circumstances forced him to temporarily ‘retire’ from his journalistic activities, he devoted himself to writing novels. His first, Il piacere (1889), was later translated into English as The Child of Pleasure. His next novel was Giovanni Episcopo (1891). It was his third novel, L’innocente (It: The Intruder), published in 1892 and later translated into French, that first brought him attention and acclaim from foreign critics. His pen worked feverishly after this, creating novels and books of poetry. Of the former, his novel Il fuoco (1900) is considered by many literary critics to be the most lavish glorification of any city (in this case, Venice) ever written. Of the latter, his book Il Poema Paradisiaco (1893) is considered among the finest examples of D’Annunzio’s poetry.

His entrance into upper-class Roman society came in the form of a young, attractive woman named Maria Hardouin di Gallese. He seduced and impregnated her in April of1893, marrying her four months later under a cloud of scandal. Maria was the daughter of a noble house, and her father, a duke, strongly disapproved of D’Annunzio as a son-in-law. He was even conspicuously absent from their wedding. Though initially smitten with his young bride, Gabriele would later develop the disinterest that characterized his relationships with women throughout his life. After bringing three sons into the world, D’Annunzio and his wife divorced in 1891.

It would seem only natural a man with his surpassing ambitions would develop an interest in politics, and in that regard Gabriele D’Annunzio would hardly defy convention. Taking advantage of a vacancy in the Italian Parliament, D’Annunzio campaigned for a seat representing Ortona a Mare in his native Abruzzi. It was at this time D’Annunzio the dramatist first made use of giving speeches from balconies to the masses, one of many innovations of his that his fascist protégé Benito Mussolini would later emulate.

By 1897 he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies where he sat for three years as an independent. His devil-may-care attitude, however, caused him to amass a sizable debt. He was eventually forced to flee Italy for France to escape his creditors. During his self-imposed exile he did not grow lax. Among his works he wrote the Italian libretto for Pietro Mascagni’s powerful but inordinately long opera Parasina. In 1908 he took a flight with aviation pioneer Wilbur Wright, which piqued D’Annunzio’s interest in flying. He proved to be an able aviator.

D'Annunzio's airplane navigator scroll (Photo by New York Scugnizzo)

World War I saw his return to Italy in the spring of 1915 where he campaigned extensively for that country’s entry into the war on the side of the Triple Entente (UK, France and Russia). Unbeknownst to him was the fact Italy had by April 26th, 1915 signed a treaty (known later as the Treaty of London) pledging to enter the war on the side of the entente powers. After Italy entered the war on May 23rd, 1915, he volunteered his services as a fighter pilot, taking part in many battles. The publicity he received fueled his already tremendous ego. On January 16th, 1916 while trying to fly over the city of Trieste, his flying boat was attacked by Austrian fighter aircraft. Forced to make an emergency landing, he sustained an injury to the right side of his head which left him permanently blind in his right eye.

In spite of this serious injury, he continued to fly missions into Austrian territory. In August of 1917 he led no less than three daring bombing raids on the Austrian port city of Pola (now Pula, Croatia). These raids became famous in part because of D’Annunzio’s insistence his Italian airmen celebrate the success of each raid by yelling out the ancient Greco-Roman battle cry of “Eia, eia, eia, alala!” instead of the more traditional Germanic “Ip, ip, urrah!” which he considered uncouth and barbaric.

D'Annunzio's model SVA (Photo by New York Scugnizzo)

On October 24th, 1917 Italy suffered its greatest defeat of the war in the disaster at Caporetto. On February 10-11th, 1918 he took part in a daring, if militarily unimportant raid, into Austrian territory now known as the Bakar Mockery. Though it achieved no physical military objective, it uplifted Italian morale which had suffered as a result of Caporetto while delivering a psychological blow to the Austrians.

D’Annunzio’s greatest feat during the war came on August 9th, 1918 when leading the 87th fighter squadron “La Serenissima” he dropped a total of 400,000 propaganda leaflets (50,000 of them painted in the colors of the Italian flag) over the city of Vienna, capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This daring mission is immortalized in Italy as “Il Volo su Vienna” (It: The Flight over Vienna).

At war’s end the internationally acclaimed “fighter-poet” returned to Italy, his ultra-nationalist and irredentist feelings having been hardened by years of battle. With the collapse of the Hapsburg Empire of Austria-Hungary, he dreamed of Italy expanding into the Balkans by annexing lands historically inhabited by Italian-speaking peoples. It was a dream shared by many both in Italy and on the other side of the Adriatic Sea. What would follow would catapult Gabriele D’Annunzio to the pinnacle of the fame and controversy that characterized his life.

After the war Italian armies occupied considerable territory in the Trentino, South Tyrol, Venezia Giulia, the Istrian Peninsula, Dalmatia and most of what is now Albania. In fact, these were most of the lands promised them four years earlier by the entente powers.

What threw a monkey wrench in the works was a man named Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States. The U.S. had been a late entry into the war, and in the minds of American diplomats they didn’t have to abide by the terms of the Treaty of London. Since the administration of President Teddy Roosevelt, America’s WASP elites had turned their previous continent-specific belief in “Manifest Destiny” to a global arena. At the negotiations pursuant to the infamous Treaty of Versailles, Wilson let it be known he believed every recognizable ethnos had the right to self-determination (translation: America had vested business and political interests in the creation of the pseudo-nation known as Yugoslavia).

As documented by Prof. Woodhouse, Wilson also inherited that wonderful Anglo-American tradition known as anti-Italian bigotry. This tradition had revealed itself previously on numerous occasions, most notably on March 14th, 1891 when a total of 17 Sicilian-Americans were murdered by a lynch mob comprised of a good chunk of the adult male population of the city of New Orleans, Louisiana!

During the negotiations in Paris on April 23rd, 1919 the head of the American delegation went so far as to publish a column in the French newspaper Le Temps condemning what he called “Italian imperialism”. He arrogantly claimed Italian negotiators were acting “contrary to Italian public opinion” (without stating exactly how he knew this to be true).

The crux of all this was the city of Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia). A number of powers (including America’s ‘good friend’ the UK) desired control of this strategically important area. Wilson was adamant Fiume be turned over to the nascent state of Yugoslavia to fulfill its right to ‘self-determination’. That the bulk of the citizenry was Italian-speaking and had already voted by a wide margin to become part of Italy was irrelevant.

D'Annunzio's Uniform

(Photo by New York Scugnizzo)

D’Annunzio the pan-Italian ultra-nationalist was furious with what he saw as American interference in what was basically an Italian affair. In a series of speeches he whipped up the Italian masses in preparation for his “grand adventure” in Fiume. His speeches denouncing the treachery of the Allies and the arrogance of Wilson were given wide coverage in the American press, which gratuitously heaped anti-Italian invectives on him in turn.

It also didn’t help the Italian government’s case that numerous private individuals besides D’Annunzio were taking matters into their own hands. Benito Mussolini by this time had organized his first bands of squadristi (the future Blackshirts) to battle his political opponents and pave the way for his eventual takeover of Italy. Giovanni Host-Venturi, a captain of the Arditi (elite Italian storm troopers during World War I) and a Major Giovanni Giuriati formed the Legione Fiumana (Fiume Legion) to take the port city by force, if necessary. American, British and French critics pointed to this as “proof” the Italians could not be depended upon to correctly administer the territories promised them.

On September 12th, 1919 at the head of a motley force of 2,500 irregulars, Gabriele D’Annunzio the “fighter-poet” invaded the city of Fiume. The inter-Allied force of British, American and French soldiers garrisoned there chose not to force a confrontation in order to avoid an international incident with their Italian allies. Instead they withdrew. From the governor’s balcony D’Annunzio addressed a throng of the citizenry and informed them of his plan to annex Fiume to Italy. Their wildly enthusiastic response affirmed in his mind the justness of his actions.

The Italian government, however, was not so enthusiastic. General Pietro Badoglio telegraphed the Italian soldiers who had followed D’Annunzio into Fiume that they were guilty of desertion. D’Annunzio reacted by publicly condemning the government for its weakness and indecision.

Similarly, he lashed out (though privately) at Mussolini, who up until this time was a partner in D’Annunzio’s endeavor. D’Annunzio had expected material support from Il Duce. Mussolini, however, was not yet strong enough to make such a move and chose to bide his time, instead. He even went so far as to edit and then publish the highly vituperative letter D’Annunzio had written, denouncing him, to make it seem the poet-hero was in fact supportive of him. Only in 1954 was the text of the original letter published. By then, though, D’Annunzio’s name had become so thoroughly linked with Fascism few were willing to stick their necks out to expose the true contempt he had early on developed for Mussolini and his movement.

Italian Prime Minister Francesco Saverio Nitti, realizing the weight of popular opinion was with D’Annunzio, offered him generous terms, among which was a general amnesty for him and his men. Fiume and surrounding territories would also be ultimately joined with Italy. All should have proceeded smoothly after this, but for the fact that it was now D’Annunzio himself who began to stonewall. A referendum by the people of Fiume seemed supportive of Nitti’s offer; D’Annunzio declared the vote null and void.

Apparently Gabriele D’Annunzio, like Gaius Julius Caesar 2,000 years before him, had become addicted to the powers he now wielded. The notoriety, and the legion of female admirers now at his disposal, didn’t hurt either. He rejected Nitti’s offer.

The government in Rome then demanded the plotters surrender and sent a naval task force to blockade Fiume. Things became embarrassing, however, when a number of Italian sailors, including basically the entire crew of the destroyer Espero, joined up with D’Annunzio’s forces. It has also been long alleged that a number of sympathetic rightists in Northern Italy’s industrial community clandestinely shipped supplies to D’Annunzio’s forces (in violation of the blockade) while claiming losses due to ‘piracy’.

Renato Brozzi Fiume medal

(Photo by New York Scugnizzo)

In retaliation for the blockade D’Annunzio declared Fiume an independent state, the Reggenza Italiana del Carnaro (It: Italian Regency of Carnaro) with himself as Duce. This was the closest he came to becoming the Renaissance despot he dreamed of being. As Duce he indulged his megalomania, giving balcony speeches, surrounding himself with military trappings, black-shirted followers and fostering a cult of personality.

With the help of Italian syndicalist Alceste De Ambris he wrote a constitution for Fiume, the Carta del Carnaro (It: Charter of Carnaro), which combined elements of syndicalist, corporatist and liberal republican ideals. The Charter stipulated that Fiume was a corporatist state, with nine corporations controlling various sectors of the economy and a tenth, created by D’Annunzio, representing the people he judged to be ‘superior’ (poets, prophets, heroes and “supermen”).

It must be mentioned D’Annunzio’s idea of the ‘superman’ was more in line with the philosophical vision of Nietzsche rather than the racial one of Hitler. It is also worth noting the Charter declared music to be the fundamental principle of the state. This document plus D’Annunzio’s antics in Fiume greatly interested Benito Mussolini and in no small way influenced the future course of Fascism in Italy. In fact, D’Annunzio has been described by his detractors as the “John the Baptist of Fascism”.

On November 12, 1920 Italy signed the Treaty of Rapallo with the newly-formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (renamed Yugoslavia in 1929) which, among other things, established Fiume as the independent “Free State of Fiume”, effectively ending D’Annunzio’s dictatorship. D’Annunzio responded by declaring war on Italy. By this time it was obvious his hold on the city was crumbling. On Christmas Eve Italian troops invaded Fiume in the face of stiff resistance from diehard loyalists. A naval artillery shell from the Andrea Doria through the window of his headquarters impressed upon him the wisdom of surrender.

In a way, though, he won. Fiume would be a de facto Italian possession by 1924. It would remain so until the end of World War II when the victorious Allies would pry it from Italian hands and give it to Yugoslavia (after the ‘ethnic cleansing’ of its Italian population).

Far from returning with his tail between his legs, D’Annunzio’s popularity with the Italian populace was actually enhanced by his Fiume adventure. In spite of claims by many of his Fascist sympathies, he consistently refused to have anything to do with the movement. He even ignored fascist entreaties to run in the elections on May 21, 1921.

Piazza G. D'Annunzio, Ravenna (Photo by New York Scugnizzo)

In spite of this, Mussolini regarded the erstwhile dictator as a rival for his future control of Italy. His fears were probably well-placed as by this time a number of high-ranking members of the Fascist Party of Italy, including Blackshirt leader Italo Balbo, seriously considered the idea of turning to D’Annunzio for leadership. Thus, on August 13th, 1922, when Gabriele D’Annunzio fell out of a window two days before a scheduled meeting with Mussolini and Italian PM Nitti, many believed (and still believe) he had ‘help’ from some of Il Duce’s thugs.

D’Annunzio’s injuries as a result of his fall incapacitated him, leaving him unable to witness Mussolini’s triumphal “March on Rome” (October 22-29, 1922). After this he withdrew from politics, though he still from time to time “stuck his two cents in” many of Mussolini’s decisions. In 1924, after Italy formally annexed Fiume, D’Annunzio was ennobled the Prince of Monte Nevoso by the King upon the ‘recommendation’ of Mussolini. He approved of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. However, he was adamantly opposed (along with Italo Balbo) to Mussolini having anything to do with Adolf Hitler, whom he contemptuously referred to in a letter to Mussolini as a marrano (Sp: swine).

Mussolini, for his part, was content to leave D’Annunzio alone after his ascension to power, preferring instead to regularly dole out large sums of money to him to finance his various egocentric projects. The most notable of these was a museum to himself D’Annunzio began during his lifetime, dubbed Il Vittoriale degli Italiani (It: The Shrine of Italian Victories) and located at his estate in Gardone Riviera, Lombardia. It contains his mausoleum.

Gabriele D’Annunzio died on March 1st, 1938, presumably of a stroke. His death caused a period of national mourning throughout Italy and beyond. Even in countries now hostile to Italy his passing was noted with sorrow. No less than The Times of London published this eulogy of him under the heading “The Spirit of the Cinquecento”:

Poet, novelist and politician, dramatist and demagogue, aesthete and soldier, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Prince of Monte Nevoso, is dead. No poet of our time has led a fuller life than this Byron of the modern world […] showed himself a fighter of dauntless courage and a politician who swayed the fortunes of Europe […] bore his wounds with stoic fortitude.

After his death his memory would be all but buried with him for the next 50 years. Scholars in recent decades, however, have shown a renewed interest in his life and works.

It would be simple to dismiss him as a mere hedonist and fascist (as many have done), ignoring his many contributions to the fields of journalism, poetry and drama. In truth, he was no fascist at all, for Gabriele D’Annunzio served neither Mussolini nor Fascism. He served no one and nothing other than his own ego and surpassing ambitions. His inability to form a lasting relationship with women, plus his penchant for decadent living, were perhaps his greatest personal flaws, but history has a habit of forgiving earth-shakers their frailties. His love of nature and aesthetics, as well as his utter rejection of Hitler, put him on a much higher plane than the plebe who became ruler of Italy. Had he lived in an earlier time, today he might be numbered with other tragic heroes who tried and failed like Cola di Rienzo or even Pompey the Great. His legacy is most certainly clouded by the politics of our times. His biography remains a case study of one of the most fascinating and striking personalities of the early part of the 20th century.

Niccolò Graffio

Further reading:

• John Woodhouse: Gabriele D’Annunzio: Defiant Archangel, Clarendon Press, 1998

• http://www.gabrieledannunzio.net/english/index.htm

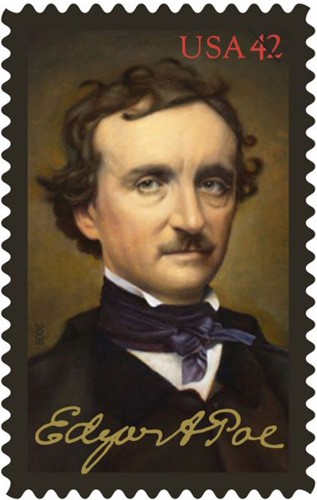

TODAY MARKS the 200th anniversary of the birth of the European-American literary genius and racially concious writer Edgar Allan Poe. I have paid my respects to the eternal memory of Edgar Poe in person at the Poe Museum in Richmond and at his and his beloved Virginia’s grave site in Baltimore, and I offer them again to all who read my words today.

TODAY MARKS the 200th anniversary of the birth of the European-American literary genius and racially concious writer Edgar Allan Poe. I have paid my respects to the eternal memory of Edgar Poe in person at the Poe Museum in Richmond and at his and his beloved Virginia’s grave site in Baltimore, and I offer them again to all who read my words today.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Or le contexte a rapidement changé après le Traité de Versailles, dont la Belgique sort largement dupée par les quatre grandes puissances (Etats-Unis, France, Grande-Bretagne, Italie), comme l’écrivait clairement Henri Davignon (photo ci-contre), dans son ouvrage « La première tourmente », consacré à ses activités diplomatiques en Angleterre pendant la première guerre mondiale. Après Versailles, nous avons Locarno (1925), qui éveille les espoirs d’une réconciliation généralisée en Europe. Ensuite, les accords militaires franco-belges sont de plus en plus contestés par les socialistes et les forces du mouvement flamand, puis, dans un deuxième temps, par le Roi et son état-major (qui critiquent l’immobilisme de la stratégie française marquée par Maginot) et, enfin, par les catholiques inquiets de la progression politique des gauches françaises. Tout cela suscite le désir de se redonner une originalité intellectuelle et littéraire marquée de « belgicismes », donc de « vernacularités » wallonne et flamande. L’univers littéraire de la droite catholique francophone va donc simultanément s’ouvrir, dès la fin des années 20, à la Flandre en tant que Flandre flamande et à la Wallonie dans toutes ses dimensions vernaculaires.

Or le contexte a rapidement changé après le Traité de Versailles, dont la Belgique sort largement dupée par les quatre grandes puissances (Etats-Unis, France, Grande-Bretagne, Italie), comme l’écrivait clairement Henri Davignon (photo ci-contre), dans son ouvrage « La première tourmente », consacré à ses activités diplomatiques en Angleterre pendant la première guerre mondiale. Après Versailles, nous avons Locarno (1925), qui éveille les espoirs d’une réconciliation généralisée en Europe. Ensuite, les accords militaires franco-belges sont de plus en plus contestés par les socialistes et les forces du mouvement flamand, puis, dans un deuxième temps, par le Roi et son état-major (qui critiquent l’immobilisme de la stratégie française marquée par Maginot) et, enfin, par les catholiques inquiets de la progression politique des gauches françaises. Tout cela suscite le désir de se redonner une originalité intellectuelle et littéraire marquée de « belgicismes », donc de « vernacularités » wallonne et flamande. L’univers littéraire de la droite catholique francophone va donc simultanément s’ouvrir, dès la fin des années 20, à la Flandre en tant que Flandre flamande et à la Wallonie dans toutes ses dimensions vernaculaires.  L’aristocrate gantois Roger Kervyn de Marcke ten Driessche (né en 1896 - photo ci-contre) franchit un pas de plus dans ce glissement vers la reconnaissance de la diversité littéraire belge, issue de la diversité dialectale et linguistique du pays. Kervyn se veut « passeur » : l’élite belge, et donc son aristocratie, doit viser le bilinguisme parfait pour conserver son rôle dans la société à venir, souligne Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre. Kervyn assume dès lors le rôle de « passeur » donc de traducteur ; il passera toutes les années 30 à traduire articles, essais et livres flamands pour la « Revue Belge » et pour les Editions Rex. On finit par considérer, dans la foulée de cette action individuelle d’un Gantois francophone, que le « monolinguisme est trahison ». Le terme est fort, bien sûr, mais, même si l’on fait abstraction du cadre étatique belge, avec ses institutions à l’époque très centralisées (le fédéralisme ne sera réalisé définitivement qu’au début des années 90 du 20ème siècle), peut-on saisir les dynamiques à l’œuvre dans l’espace entre Somme et Rhin, peut-on sonder les mentalités, en ne maniant qu’une et une seule panoplie d’outils linguistiques ? Non, bien évidemment. Néerlandais, français et allemand, avec toutes leurs variantes dialectales, s’avèrent nécessaires. Pour Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre, le bel ouvrage de Charles d’Ydewalle, « Enfances en Flandre » (1935) ne décrit que les sentiments et les mœurs des francophones de Flandre, essentiellement de Bruges et de Gand. A ce titre, il ne participe pas du mouvement que Kervyn a voulu impulser. C’est exact. Et les humbles du menu peuple sont les grands absents du livre de d’Ydewalle, de même que les représentants de l’élite alternative qui se dressait dans les collèges catholiques et dans les cures rurales (Cyriel Verschaeve !). Il n’empêche qu’une bonne lecture d’ « Enfances en Flandre » de d’Ydewalle permettrait à des auteurs flamands, et surtout à des créateurs cinématographiques, de mieux camper bourgeois et francophones de Flandre dans leurs oeuvres. Ensuite, les notes de d’Ydewalle sur le passé de la terre flamande de César aux « Communiers », et sur le dialecte ouest-flamand qu’il défend avec chaleur, méritent amplement le détour.

L’aristocrate gantois Roger Kervyn de Marcke ten Driessche (né en 1896 - photo ci-contre) franchit un pas de plus dans ce glissement vers la reconnaissance de la diversité littéraire belge, issue de la diversité dialectale et linguistique du pays. Kervyn se veut « passeur » : l’élite belge, et donc son aristocratie, doit viser le bilinguisme parfait pour conserver son rôle dans la société à venir, souligne Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre. Kervyn assume dès lors le rôle de « passeur » donc de traducteur ; il passera toutes les années 30 à traduire articles, essais et livres flamands pour la « Revue Belge » et pour les Editions Rex. On finit par considérer, dans la foulée de cette action individuelle d’un Gantois francophone, que le « monolinguisme est trahison ». Le terme est fort, bien sûr, mais, même si l’on fait abstraction du cadre étatique belge, avec ses institutions à l’époque très centralisées (le fédéralisme ne sera réalisé définitivement qu’au début des années 90 du 20ème siècle), peut-on saisir les dynamiques à l’œuvre dans l’espace entre Somme et Rhin, peut-on sonder les mentalités, en ne maniant qu’une et une seule panoplie d’outils linguistiques ? Non, bien évidemment. Néerlandais, français et allemand, avec toutes leurs variantes dialectales, s’avèrent nécessaires. Pour Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre, le bel ouvrage de Charles d’Ydewalle, « Enfances en Flandre » (1935) ne décrit que les sentiments et les mœurs des francophones de Flandre, essentiellement de Bruges et de Gand. A ce titre, il ne participe pas du mouvement que Kervyn a voulu impulser. C’est exact. Et les humbles du menu peuple sont les grands absents du livre de d’Ydewalle, de même que les représentants de l’élite alternative qui se dressait dans les collèges catholiques et dans les cures rurales (Cyriel Verschaeve !). Il n’empêche qu’une bonne lecture d’ « Enfances en Flandre » de d’Ydewalle permettrait à des auteurs flamands, et surtout à des créateurs cinématographiques, de mieux camper bourgeois et francophones de Flandre dans leurs oeuvres. Ensuite, les notes de d’Ydewalle sur le passé de la terre flamande de César aux « Communiers », et sur le dialecte ouest-flamand qu’il défend avec chaleur, méritent amplement le détour.

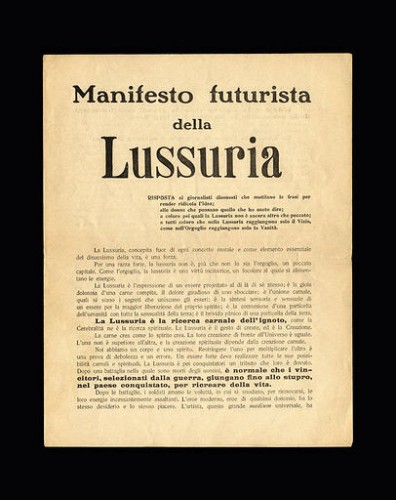

Lust, when viewed without moral preconceptions and as an essential part of life’s dynamism, is a force.

Lust, when viewed without moral preconceptions and as an essential part of life’s dynamism, is a force.

Se non ora quando? La donna e la sua dignità, il suo ruolo sociale. La posizione da assumere all’interno e nei confronti del sistema Italia. Dibattiti su dibattiti, manifestazioni, mobilitazioni in nome di una rinascita in gonnella, appelli infuocati al popolo rosa. Costruzione di una nuova identità femminile o starnazzo di gallinelle? La donna paragonata all’uomo, divisione fra sessi al centro di battaglie e rivendicazioni che sanciscono nuove superiorità o inferiorità?

Se non ora quando? La donna e la sua dignità, il suo ruolo sociale. La posizione da assumere all’interno e nei confronti del sistema Italia. Dibattiti su dibattiti, manifestazioni, mobilitazioni in nome di una rinascita in gonnella, appelli infuocati al popolo rosa. Costruzione di una nuova identità femminile o starnazzo di gallinelle? La donna paragonata all’uomo, divisione fra sessi al centro di battaglie e rivendicazioni che sanciscono nuove superiorità o inferiorità?

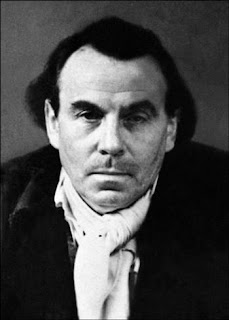

Louis-Ferdinand Céline (1894–1961) is my favorite writer I don’t enjoy reading, much as Vertigo is my favorite movie I don’t enjoy watching.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline (1894–1961) is my favorite writer I don’t enjoy reading, much as Vertigo is my favorite movie I don’t enjoy watching.

Voor zijn succes als militair schrijver, was er eerst Mabire de Alpenverkenner (De chasseurs alpins waren een verkennerseenheid van de toenmalige franse infanterie) , die al op dertigjarige leeftijd als reserve-luitenant werd opgeroepen om onder de nationale vlag zijn diensttijd uit te dienen in het Algerijnse bergland (Djebel). Een wapenonderdeel als geen ander, dat Mabire zijn hele leven trouw zou blijven. Echter niets bestemde de Normandische schrijver voor, zich te tooien met de bekende koningsblauwe ‘taart’ het hoofddeksel der verkenners.

Voor zijn succes als militair schrijver, was er eerst Mabire de Alpenverkenner (De chasseurs alpins waren een verkennerseenheid van de toenmalige franse infanterie) , die al op dertigjarige leeftijd als reserve-luitenant werd opgeroepen om onder de nationale vlag zijn diensttijd uit te dienen in het Algerijnse bergland (Djebel). Een wapenonderdeel als geen ander, dat Mabire zijn hele leven trouw zou blijven. Echter niets bestemde de Normandische schrijver voor, zich te tooien met de bekende koningsblauwe ‘taart’ het hoofddeksel der verkenners.

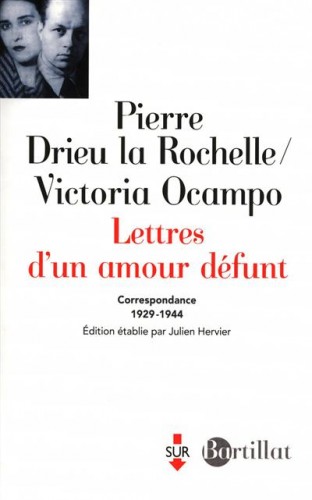

L’anno in cui si incontrarono, il 1928, Victoria Ocampo era una bella e ricca argentina non ancora quarantenne, sposata, ma di fatto separata e con un unico grande amore alle spalle, e Pierre Drieu La Rochelle un brillante trentacinquenne senza lavoro fisso, al secondo e già fallito matrimonio, con molte avventure sentimentali dietro di lui. Che cosa spingesse l’una nelle braccia dell’altro e viceversa non è facile dire: negli scrittori Victoria cercava gli uomini, anche se pur sempre come intesa di anime, più che di corpi; quanto a Drieu, la sua attrazione era figlia della prevenzione, il fascino esercitato da una donna intelligente, ovvero ai suoi occhi un controsenso, se non un elemento contro natura.

L’anno in cui si incontrarono, il 1928, Victoria Ocampo era una bella e ricca argentina non ancora quarantenne, sposata, ma di fatto separata e con un unico grande amore alle spalle, e Pierre Drieu La Rochelle un brillante trentacinquenne senza lavoro fisso, al secondo e già fallito matrimonio, con molte avventure sentimentali dietro di lui. Che cosa spingesse l’una nelle braccia dell’altro e viceversa non è facile dire: negli scrittori Victoria cercava gli uomini, anche se pur sempre come intesa di anime, più che di corpi; quanto a Drieu, la sua attrazione era figlia della prevenzione, il fascino esercitato da una donna intelligente, ovvero ai suoi occhi un controsenso, se non un elemento contro natura. Ma chi era veramente Victoria Ocampo, al di là dell’eco di un nome che oggi, escluso qualche specialista, evoca pallide frequentazioni letterarie fra le due sponde dell’Oceano Atlantico, il nome di una rivista, Sur, e di un collaboratore d’eccezione, Borges?

Ma chi era veramente Victoria Ocampo, al di là dell’eco di un nome che oggi, escluso qualche specialista, evoca pallide frequentazioni letterarie fra le due sponde dell’Oceano Atlantico, il nome di una rivista, Sur, e di un collaboratore d’eccezione, Borges?

La distanza, le differenze di opinioni politiche, la stanchezza che si insinua in ogni legame sentimentale, allenteranno nel tempo i rapporti, senza mai però reciderli. Negli anni ’30, un ciclo di conferenze in Argentina organizzato dalla Ocampo sarà per Drieu l’occasione per mettere a fuoco ideologie e scelte di campo: «È stato lì che ho capito che la vita del mondo occidentale stava uscendo dal suo torpore e che si apprestava ad essere lacerata dal dilemma fascismo-comunismo. Da quel momento, ho camminato rapidamente verso la caduta in un destino politico». La summa di tutto questo sarà, nel 1943, L’uomo a cavallo, storia di un dittatore boliviano che sogna l’unità del continente latino-americano e la riconciliazione delle classi sociali. Camilla, l’eroina del romanzo, è in realtà Victoria Ocampo, e naturalmente il loro è un amore destinato al fallimento. «Sarebbe ora che tu capissi che le donne sono anche esseri umani» gli aveva rimproverato un giorno... Perché Ocampo sapeva che «nella sua maniera di amare la Francia riconosco il suo modo di amare le donne che gli ho spesso rimproverato e che era poi così irritante, ma non meschino. Se Drieu è per una politica che non ci piace, non lo è per ragioni inconfessabili, basse o interessate. Un giorno gli dissi: Tu sei Pietro, e su questa pietra non costruirò la mia chiesa. Ma la mia tenerezza gli resta fedele, incurabilmente fedele».

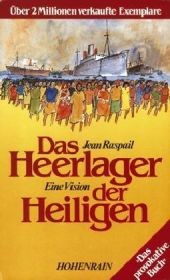

La distanza, le differenze di opinioni politiche, la stanchezza che si insinua in ogni legame sentimentale, allenteranno nel tempo i rapporti, senza mai però reciderli. Negli anni ’30, un ciclo di conferenze in Argentina organizzato dalla Ocampo sarà per Drieu l’occasione per mettere a fuoco ideologie e scelte di campo: «È stato lì che ho capito che la vita del mondo occidentale stava uscendo dal suo torpore e che si apprestava ad essere lacerata dal dilemma fascismo-comunismo. Da quel momento, ho camminato rapidamente verso la caduta in un destino politico». La summa di tutto questo sarà, nel 1943, L’uomo a cavallo, storia di un dittatore boliviano che sogna l’unità del continente latino-americano e la riconciliazione delle classi sociali. Camilla, l’eroina del romanzo, è in realtà Victoria Ocampo, e naturalmente il loro è un amore destinato al fallimento. «Sarebbe ora che tu capissi che le donne sono anche esseri umani» gli aveva rimproverato un giorno... Perché Ocampo sapeva che «nella sua maniera di amare la Francia riconosco il suo modo di amare le donne che gli ho spesso rimproverato e che era poi così irritante, ma non meschino. Se Drieu è per una politica che non ci piace, non lo è per ragioni inconfessabili, basse o interessate. Un giorno gli dissi: Tu sei Pietro, e su questa pietra non costruirò la mia chiesa. Ma la mia tenerezza gli resta fedele, incurabilmente fedele». An Jean Raspails berühmt-berüchtigten Roman

An Jean Raspails berühmt-berüchtigten Roman  Dabei gilt es auch, den gigantischen Verrat zu sehen, der zur Zeit von den Eliten der westlichen Welt an ihren Völkern begangen wird. Raspails sardonische Karikatur der landauf landab herrschenden linksliberalen Psychose, die tagtäglich neue

Dabei gilt es auch, den gigantischen Verrat zu sehen, der zur Zeit von den Eliten der westlichen Welt an ihren Völkern begangen wird. Raspails sardonische Karikatur der landauf landab herrschenden linksliberalen Psychose, die tagtäglich neue

Dans ce magma de brics et de brocs, de débris de choses jadis glorieuses, flotte un roman étonnant, celui de Gaston Compère [photo], écrivain complexe, à facettes diverses, avant-gardiste de la poésie, parfois baroque, et significativement intitulé « Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, Duc de Bourgogne ». Né dans le Condroz namurois en novembre 1924, Gaston Compère a mené une vie rangée de professeur d’école secondaire, tout en se réfugiant, après ses cours, dans une littérature particulière, bien à lui, où théâtre, prose et poésie se mêlent, se complètent. Dans le roman consacré au Duc, Compère use d’une technique inhabituelle : faire une biographique non pas racontée par un tiers extérieur à la personne trépassée, mais par le « biographé » lui-même. Le roman est donc un long monologue du Duc, approximativement deux ou trois cent ans après sa mort sur un champ de bataille près de Nancy en 1477. Compère y glisse toutes les réflexions qu’il a lui-même eues sur la mort, sur le destin de l’homme, qu’il soit simple quidam ou chef de guerre, obscur ou glorieux. Les actions de l’homme, du chef, volontaires ou involontaires, n’aboutissent pas aux résultats escomptés, ou doivent être posées, envers et contre tout, même si on peut parfaitement prévoir le désastre très prochain, inéluctable, qu’elles engendreront. Ensuite, Compère, musicologue spécialiste de Bach, fait dire au Duc toute sa philosophie de la musique, qu’il définit comme « formalisation intelligible du mystère de l’existence » ou comme « détentrice du vrai savoir ». Pour Compère, « la philosophie est un discours sur les choses et en marge d’elles ». « Si la musique, ajoute-t-il, pouvait prendre sa place, nous connaîtrions selon la musique et en elle. Alors, notre connaissance ne resterait pas extérieure ; au contraire, elle occuperait le cœur de l’être ».

Dans ce magma de brics et de brocs, de débris de choses jadis glorieuses, flotte un roman étonnant, celui de Gaston Compère [photo], écrivain complexe, à facettes diverses, avant-gardiste de la poésie, parfois baroque, et significativement intitulé « Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, Duc de Bourgogne ». Né dans le Condroz namurois en novembre 1924, Gaston Compère a mené une vie rangée de professeur d’école secondaire, tout en se réfugiant, après ses cours, dans une littérature particulière, bien à lui, où théâtre, prose et poésie se mêlent, se complètent. Dans le roman consacré au Duc, Compère use d’une technique inhabituelle : faire une biographique non pas racontée par un tiers extérieur à la personne trépassée, mais par le « biographé » lui-même. Le roman est donc un long monologue du Duc, approximativement deux ou trois cent ans après sa mort sur un champ de bataille près de Nancy en 1477. Compère y glisse toutes les réflexions qu’il a lui-même eues sur la mort, sur le destin de l’homme, qu’il soit simple quidam ou chef de guerre, obscur ou glorieux. Les actions de l’homme, du chef, volontaires ou involontaires, n’aboutissent pas aux résultats escomptés, ou doivent être posées, envers et contre tout, même si on peut parfaitement prévoir le désastre très prochain, inéluctable, qu’elles engendreront. Ensuite, Compère, musicologue spécialiste de Bach, fait dire au Duc toute sa philosophie de la musique, qu’il définit comme « formalisation intelligible du mystère de l’existence » ou comme « détentrice du vrai savoir ». Pour Compère, « la philosophie est un discours sur les choses et en marge d’elles ». « Si la musique, ajoute-t-il, pouvait prendre sa place, nous connaîtrions selon la musique et en elle. Alors, notre connaissance ne resterait pas extérieure ; au contraire, elle occuperait le cœur de l’être ».

James O’Meara on Henry James & H. P. Lovecraft

The Lesson of the Monster; or, The Great, Good Thing on the Doorstep

James J. O'Meara

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

We’ve been very pleased by the response to our essay “The Eldritch Evola,” which was not only picked up by Greg Johnson (whose own Confessions of a Reluctant Hater is out and essential reading) for his estimable website Counter-Currents, but even managed to lurch upwards and lay a terrible, green claw on the bottom rung of the “Top Ten Most Visited Posts” there in January.

Coincidentally, we’ve been delving into the newer Penguin Portable Henry James , being a sucker for the Portables in general, and especially those in which a wise editor goes to the trouble of cutting apart a life’s work of legendary unreadability and stitching together a coherent, or at least assimilable, narrative, for the convenience of us amateurs, from Malcolm Cowley’s first, the legendary Portable Faulkner

, being a sucker for the Portables in general, and especially those in which a wise editor goes to the trouble of cutting apart a life’s work of legendary unreadability and stitching together a coherent, or at least assimilable, narrative, for the convenience of us amateurs, from Malcolm Cowley’s first, the legendary Portable Faulkner that rescued “Count No-Account,” as he was known among his homies, to the recent Portable Jack Kerouac

that rescued “Count No-Account,” as he was known among his homies, to the recent Portable Jack Kerouac epic saga recounted by Ann Charters.

epic saga recounted by Ann Charters.

The “new” Portable Henry James attempts something of the sort (as opposed to the older one, which was your basic collection) by recognizing the impossibility of even including large excerpts from the “major” works, and instead gives us some of the basic short works (Daisy Miller, Turn of the Screw, “The Jolly Corner,” etc.) and then hundreds of pages of travel pieces, criticism, letters, even parodies and tributes, as well a a list of bizarre names (Cockster? Dickwinter?) and above all, in a section called “Definition and Description,” little vignettes, often only a paragraph, exemplifying the Jamesian precision, a sort of anthology of epiphanies, the great memorable moments from “An Absolutely Unmarried Woman” to “An American Corrected on What Constitutes ‘the Self’” from the novels, and similar nonfiction moments from James’ travels, such as “The Individual Jew” to “New York Power” to “American Teeth” and “The Absence of Penetralia.”

The latter section in particular is part of a defense which the editor seems to feel needs to be mounted in his Introduction, of the Jamesian “difficult” prose style (as are the collection of tributes, including the surprising, to me at least, Ezra Pound).

I bring these two together because I could not help but think of ol’ Lovecraft himself in this context. Is Lovecraft not the corresponding Master of Bad Prose? As Edmund Wilson once quipped, the only horror in Lovecraft’s corpus was the author’s “bad taste and bad art.”

One can only imagine what James would have thought of Lovecraft, although we know, from excerpts here on Baudelaire and Hawthorne, what he thought of Poe, and more importantly, of those who were fans: “to take [Poe] with more than a certain degree of seriousness is to lack seriousness one’s self. An enthusiasm for Poe is the mark of a decidedly primitive stage of reflection”; James may even have based the poet in “The Aspern Papers,” a meditation on America’s cultural wasteland, on Poe. However, his distaste is somewhat ambiguous, as compared with Baudelaire, Poe is “vastly the greater charlatan of the two, as well as the greater genius.”

For all his “better” taste and talent for reflection, it’s little realized today, as well, that James’s reputation went into steep decline after his death, and was only revived in the fifties, as part of a general reconsideration of 19th century American writers, like Melville, so that even James could be said to have, like Lovecraft, been forgotten after death except for a small coterie that eventually stage managed a revival years later.

Are James and Lovecraft as different as all that? One can’t help but notice, from the list above, that a surprising amount of James’s work, and among it the best, is in the ‘weird’ mode, and in precisely the same “long short story” form, “the dear, the blessed nouvelle,” in which Lovecraft himself hit his stride for his best and most famous work. (Both “Daisy Miller” and “At the Mountains of Madness” suffered the same fate: rejection by editors solely put off by their ‘excessive’ length for magazine publication.) The nouvelle of course accommodated James’ legendary prolixity.

The editor, John Auchard, puts James’s prolixity into the context of the 19th century ‘loss of faith.’ Art was intended to take the place of religion, principally by replacing the lost “next world” by an increased concentration on the minutia of this one. Experience might be finite, but it could still “burn with a hard, gem-like flame” as Pater famously counseled.

That counsel, of course, took place in the first, then self-suppressed, then retained afterword to his The Renaissance . René Guénon has in various places diagnosed this as the essential fraud of the Renaissance, the exchange of a vertical path to transcendence for a horizontal dissipation and dispersal among finite trivialities, usually hoked-up as “man discovered the vast extent of the world and himself,” blah blah blah. As Guénon points out, it’s a fool’s bargain, as the finite, no matter how extensive and intricate, is, compared to the infinite, precisely nothing.

. René Guénon has in various places diagnosed this as the essential fraud of the Renaissance, the exchange of a vertical path to transcendence for a horizontal dissipation and dispersal among finite trivialities, usually hoked-up as “man discovered the vast extent of the world and himself,” blah blah blah. As Guénon points out, it’s a fool’s bargain, as the finite, no matter how extensive and intricate, is, compared to the infinite, precisely nothing.

Baron Evola, on the other hand, distinguishes several types of Man, and is willing to let some of them find their fulfillment in such worldliness. It is, however, unworthy of one type of Man: Aryan Man. See the chapter “Determination of the Vocations” in his The Doctrine of Awakening: The Attainment of Self-Mastery According to the Earliest Buddhist Texts .

.

So the nouvelle length accumulation of detail and precision of judgment, in James, is intended to produce some kind of this-worldly ersatz transcendence. Was this perhaps the same intent in Lovecraft, the use of the nouvelle length tale to pile up detail until the mind breaks?

Lovecraft of course was also a thorough-going post-Renaissance materialist, a Cartesian mechanist with the best of them; when he finally got “The Call of Cthulhu” published, he advised his editor that:

Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large. One must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all.

But as John Miller notes, this is exactly what is needed to produce the Lovecraft Effect:

That’s nihilism, of course, and we’re free to reject it. But there’s nothing creepier or more terrifying than the possibility that our lives are exercises in meaninglessness.

What is there to choose, between the unrealized but metaphysically certain nothingness of the Jamesian finite detail, and the all-too-obvious nothingness of Lovecraft’s worldview?

What separates James from Lovecraft and Evola is, along the lines of our previous effort, is precisely what T. S. Eliot, in praise of James (the essay is in the Portable too): “He has a mind so fine no idea could penetrate it.” Praise, note, and contrasted with the French, “the Home of Ideas,” and such Englishmen, or I guess pseudo-Englishmen, as Chesterton, “whose brain swarms with ideas” but cannot think, meaning, one gathers, stand apart with skepticism. One notes the Anglican Eliot seeming to flinch back, like a good English gentleman, from those dirty, unruly Frenchmen like Guénon, and such Englishmen who, like Chesterton, went “too far” and went and “turned Catholic” out of their love of “smells and bells.”

What Evola and Lovecraft had was precisely an Idea, the idea of Tradition; in Lovecraft’s case, a made-up, fictional one, but designed to have the same effect. But that’s the issue: when is Tradition only made up? For Evola and Guénon, the mind of Traditional Man is indeed not “fine” enough to evade penetration by the Idea; he is open to the transcendent, vertical dimension, which is realized in Intellectual Intuition.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that Intellectual Intuition, or what Evola calls his “Traditional Method” is usefully compared with what Spengler called, speaking of his own method, “physiognomic tact.” I wrote: “A couple years ago I found a passage in one of the few books on Spengler in English, by H. Stuart Hughes, where it seemed like he was actually giving a good explication of Guénon’s metaphysical (vs. systematic philosophy) method. I think it could apply to Evola’s method as well” Hughes writes:

Spengler rejected the whole idea of logical analysis. Such “systematic” practices apply only in the natural sciences. To penetrate below the surface of history, to understand at least partially the mysterious substructure of the past, a new method — that of “physiognomic tact”— is required.

This new method, “which few people can really master,” means “instinctively to see through the movement of events. It is what unites the born statesman and the true historian, despite all opposition between theory and practice.” [It takes from Goethe and Nietzsche] the injunction to “sense” the reality of human events rather than dissect them. In this new orientation, the historian ceases to be a scientist and becomes a poet. He gives up the fruitless quest for systematic understanding. . . . “The more historically men tried to think, the more they forgot that in this domain they ought not to think.” They failed to observe the most elementary rule of historical investigation: respect for the mystery of human destiny.

So causality/science, destiny/history. Rather than chains of reasoning and “facts” the historian employs his “tact” [really, a kind of Paterian "taste"] to “see” the big picture: how facts are composed into a destiny. Rather than compelling assent, the historian’s words are used to bring about a shared intuition.

I suppose Guénon and Co. would bristle at being lumped in with “poets” but I think the general point is helpful in understanding the “epistemology” of what Guénon is doing: not objective (but empty) fact-gathering but not merely aesthetic and “subjective” either, since metaphysically “seeing” the deeper connection can be “induced” by words and thus “shared.”

What Guénon, Evola, and Spengler seek to do deliberately, what Lovecraft did fictionally or even accidentally, what James’s mind was “too fine” to do at all, is to not see mere facts, or see a lot of them, or even see them very very intently, but to see through them and thus acquire metaphysical insight, and, through the method of obsessive accumulation of detail, share that insight by inducing it in others.

To do this one must be “penetrated” by the Idea, Guénon’s metaphysics, Evola’s historical cycles, Lovecraft’s Mythos, and allow it be be generated within oneself. Only then can you see.

Speaking of “penetration,” one does note James’s obsession with “penetralia”; also one recalls the remarkable way Schuon brings out how in Christianity the Word is brought by Gabriel to Mary, who in mediaeval paintings is often shown with a stream of words penetrating her ear, thus conceiving virginally, while in Islam, Gabriel brings the Word to Muhammad, who recites (gives birth to) the Koran. Itself a wonderful example of the Traditional Method: moving freely among the material elements of various traditions to weave a pattern that re-creates an Idea in the mind of the listener. Do you see how Christianity and Islam relate? Do you see?

Finally, we should note that Lovecraft, for his own sake, did get in a preemptive shot at James:

In The Turn of the Screw, Henry James triumphs over his inevitable pomposity and prolixity sufficiently well to create a truly potent air of sinister menace; depicting the hideous influence of two dead and evil servants, Peter Quint and the governess, Miss Jessel, over a small boy and girl who had been under their care. James is perhaps too diffuse, too unctuously urbane, and too much addicted to subtleties of speech to realise fully all the wild and devastating horror in his situations; but for all that there is a rare and mounting tide of fright, culminating in the death of the little boy, which gives the novelette a permanent place in its special class.– Supernatural Horror in Literature, Chapter VIII.

Source: http://jamesjomeara.blogspot.com/