Wieder einmal muss ich mich bei Tobias Wimbauer bedanken für den Hinweis auf diesen Artikel aus "Jungen Freiheit":

JF, 2/11 / 14. Oktober 2011

Michael Böhm

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

Gottfried Benn und sein Denken

Bewährungsprobe des Nationalismus

Arno Bogenhausen

Ex: http://www.hier-und-jetzt-magazin.de/

Eine neuerschienene Biographie des Dichterphilosophen gibt uns Anlaß, über das Verhältnis von nationalem Bekenntnis und geistigem Solitär nachzudenken. Gunnar Decker, der mit seiner Arbeit weit mehr bietet als Raddatz („Gottfried Benn, Leben – niederer Wahn“) und auch gegenüber Helmut Lethens gelungenem Werk („Der Sound der Väter“) einen Zugewinn erbringt, ist als Angehöriger des Jahrgangs 1965 eindeutiger Nachachtundsechziger, damit weniger befangen und im Blick getrübt als die Vorgänger. Bei ihm finden sich Unkorrektheiten wie die beiläufige Bemerkung: „Es gehört zur Natur der Politik, daß sie jeden, egal wie gearteten, Gedanken konstant unter Niveau verwirklicht.“ Dennoch sind auch für ihn Benns Berührungen mit dem Nationalsozialismus und die folgende „aristokratische Form der Emigration“ im Offizierskorps der Deutschen Wehrmacht ein Grund zu längerer Reflexion; allein drei der sechs Kapitel sind den Jahren des Dritten Reiches gewidmet.

Benns Hinwendung zum NS, die 1933 in Rundfunkreden, Aufsätzen und dem Amt des Vizepräsidenten der „Union nationaler Schriftsteller“ zum Ausdruck kam, ist unbestritten. Sie war nicht äußerer Anpassung geschuldet, sondern beruhte auf der Überzeugung, an einer historisch folgerichtigen Wende zu stehen. Der Verächter des Fortschrittsgedankens und jeder programmatischen Erniedrigung des Menschen hoffte, „daß ein letztes Mal im Nachklang ferner dorischer Welten Staat und Kunst zu einer großen, einander begeisternden Form fänden“ (Eberhard Straub). Am 23. 9. 1933 schrieb er einer Freundin in die Vereinigten Staaten, „daß ich und die Mehrzahl aller Deutschen … vor allem vollkommen sicher sind, daß es für Deutschland keine andere Möglichkeit gab. Das alles ist ja auch nur ein Anfang, die übrigen Länder werden folgen, es beginnt eine neue Welt; die Welt, in der Sie und ich jung waren und groß wurden, hat ausgespielt und ist zu Ende.“

Diese Haltung wird ihm bis heute zum Vorwurf gemacht. Es beginnt 1953 mit Peter de Mendelssohns Buch „Der Geist der Despotie“, in dem zugleich Hamsun und Jünger in Moralin getaucht werden. Sehr schön liest sich bei Decker, warum die Vorwürfe ihr Thema verfehlen: „Auf immerhin fast fünfzig Seiten wird Benns Versagen behandelt, das letztlich in seinem Unwillen gegen ein moralisches Schuldeingeständnis gründet. Das überzeugt den Leser nur halb, denn de Mendelssohn argumentiert fast ausschließlich moralisch – und da fühlt Benn sich immer am wenigsten gemeint. In diesem Buch klingt einem ein Ton entgegen, wie später bei den 68ern mit ihrer ebenso ekstatischen wie pauschalen Anklage der Vätergeneration. Oder auch – auf anderer Ebene – wie bei manchem DDR-Bürgerrechtler, dem die DDR abhanden gekommen ist und der darum aus seinem Bürgerrechtssinn eine Ikone macht, die er pflegt.“

Benn hat seinen zahllosen Interpreten, die nach Erklärungen suchten, ihre Arbeit kaum erleichtert. Tatsächlich sind weder gewundene Rechtfertigungsversuche noch tiefenpsychologische Studien, wie sie Theweleit betrieb, vonnöten, um das angeblich „Unverständliche“ zu deuten. Der Denker selbst hat 1950 in öffentlicher Ansprache eine ganz schlichte, in ihrer Einfachheit allen Theorienebel beiseite fegende Aussage getroffen: „Es war eine legale Regierung am Ruder; ihrer Aufforderung zur Mitarbeit sich entgegenzustellen, lag zunächst keine Veranlassung vor.“

Das eigentliche Problem liegt somit nicht in Benns Entscheidung, mit der er – auch unter Intellektuellen – nun wirklich nicht alleine stand, sondern in der Unfähigkeit der Verantwortlichen, mit ihr umzugehen. Klaus Mann stellte als inzwischen ausländischer Beobachter nicht ohne Befriedigung fest: „seine Angebote stießen auf taube bzw. halbtaube Ohren … Benn hört vor allem deshalb auf, Ende 1934, Faschist zu sein oder zu werden, weil es keine passende Funktion für ihn gibt im nationalsozialistischen Züchtungsstaat.“

Vom NS-Ärztebund, der diskriminierende Anordnungen erließ, über fanatische Zeitungsschreiber, die ihm ungenügende völkische Gesinnung attestierten, bis zu Funktionären, denen der Expressionismus insgesamt undeutsch vorkam, schlug ihm Ablehnung entgegen. Seine virile Unbefangenheit in sexuellen Angelegenheiten wurde ihm 1936 von einem Anonymus im „Schwarzen Korps“ verübelt: „er macht auch in Erotik, und wie er das macht, das befähigt ihn glatt zum Nachfolger jener, die man wegen ihrer widernatürlichen Schweinereien aus dem Hause jagte.“ Benn sah sich danach zu der ehrenwörtlichen Erklärung gezwungen, nicht homophil zu sein. Die Parteiamtliche Prüfungskommission zum Schutze des nationalsozialistischen Schrifttums hielt der Deutschen Verlags-Anstalt vor, „völlig überholte Arbeiten“ zu publizieren und übermittelte der Geheimen Staatspolizei, Gedichte Benns zeugten von „pathologischer Selbstbefleckung“, weshalb zu bedenken sei, „ob der Verleger nicht zur Rechenschaft gezogen werden soll“. Ein mit der „Säuberung“ der Kunst befaßter Maler-Autor warf ihm „Perversitäten“ vor, die an „Bordellgraphik und Obszönitätenmalerei“ erinnerten; es sei angebracht, seine Aufnahme in das Offizierskorps „rückgängig zu machen“. Boshafte Unterstellungen gipfelten darin, seinen Familiennamen auf das semitische „ben“ zurückzuführen und ihm eine jüdische Herkunft anzudichten. Lediglich seinem Fürsprecher Hanns Johst, der bei Himmler intervenierte, verdankte Benn, nicht mit weiterreichenden Maßnahmen überzogen zu werden.

Worum es hier geht, ist nicht die Beweinung eines „dunklen Kapitels deutscher Geschichte“. Benn selbst schrieb 1930 an Gertrud Hindemith: „Vergessen Sie nie, der menschliche Geist ist als Totschläger entstanden und als ein ungeheures Instrument der Rache, nicht als Phlegma der Demokraten, er galt dem Kampf gegen die Krokodile der Frühmeere und die Schuppentiere in den Höhlen – nicht als Puderquaste“. Die Agonalität des Lebens war ihm vertraut, und angesichts der Praxis heutiger Bürokratien, die mißliebige Geister einer durchaus größeren Drangsal überantworten, als sie ihm widerfuhr, soll auch nicht leichthin der Stab über eine „offene Diktatur“ gebrochen werden. Daß aber die einmalige Gelegenheit vertan wurde, eine Persönlichkeit dieses Grades für den neuen Staat zu gewinnen, war kaum verzeihlich. Jene Nationalsozialisten, die Benn schlechthin verwarfen, begaben sich – man muß es so hart sagen – auf das Niveau des Bolschewismus herab. In kleinbürgerlich-egalitären Horizonten und ideologisch miniaturisierten Maßstäben befangen, erkannten sie nicht, daß ihnen ein Großer gegenüberstand, dessen Werk – was immer man im einzelnen ablehnen mag – den Deutschen zur Ehre gereichte. (Dasselbe gilt für eine Reihe weiterer, die alles andere als vaterlandslose Gesellen waren, aber ins Abseits gerieten; man denke nur an George, Jünger, Niekisch, Schmitt und Spengler, von dem übrigens Benn schon 1946 schrieb, er „wäre heute genauso unerwünscht und schwarzbelistet wie er es bei den Nazis war“.)

Das traurige Bild, das der Nationalsozialismus in diesem Punkte abgab, wird besonders deutlich im Vergleich mit dem faschistischen Italien, das es verstand, die vitalen Impulse des Futurismus aufzunehmen und in seine vorbildliche Pluralität zu integrieren. Benn versuchte in mehreren Aufsätzen, die futuristische Idee auch den Berliner Staatsmännern schmackhaft zu machen. Als Marinetti, der Verfasser des Futuristischen Manifestes, in seiner Eigenschaft als Präsident des italienischen Schriftstellerverbandes Berlin besuchte und ihm zu Ehren ein Bankett gegeben wurde, hielt Benn in Vertretung für Hanns Johst die Laudatio. Doch sein Mühen blieb vergeblich. Unterlagen doch selbst die weit weniger buntscheckigen Expressionisten, um deren Bewertung zunächst noch ein innernationalsozialistischer Richtungsstreit tobte, den Dogmatikern des Volkstümlichen.

Nach der sog. „Niederschlagung des Röhm-Putsches“ schreibt Benn seinem Lebensfreund Friedrich Wilhelm Oelze: „Ein deutscher Traum, wieder einmal zu Ende.“ Später wird er die Gebrechen des nationalsozialistischen Staates so beschreiben: „Ein Volk will Weltpolitik machen, aber kann keinen Vertrag halten, kolonisieren, aber beherrscht keine Sprachen, Mittlerrollen übernehmen, aber faustisch suchend – jeder glaubt, er habe etwas zu sagen, aber keiner kann reden, – keine Distanz, keine Rhetorik, – elegante Erscheinungen nennen sie einen Fatzke, – überall setzen sie sich massiv ein, ihre Ansichten kommen mit dicken Hintern, – in keiner Society können sie sich einpassen, in jedem Club fielen sie auf“.

Dennoch schließt sich Benn nach 1945 nicht den Bewältigern an. Seine Rückschau bleibt auf wenige Anmerkungen beschränkt und verfällt zu keiner Zeit in Hyperbeln. „Der Nationalsozialismus liegt am Boden, ich schleife die Leiche Hektors nicht.“ Die von den Siegern geschaffene Nachkriegsordnung analysiert er nicht weniger beißend: „Ich spreche von unserem Kontinent und seinen Renovatoren, die überall schreiben, das Geheimnis des Wiederaufbaus beruhe auf ‚einer tiefen, innerlichen Änderung des Prinzips der menschlichen Persönlichkeit’ – kein Morgen ohne dieses Druckgewinsel! –, aber wo sich Ansätze für diese Änderung zeigen wollen, setzt ihre Ausrottungsmethodik ein: Schnüffeln im Privat- und Vorleben, Denunziation wegen Staatsgefährlichkeit … diese ganze bereits klassische Systematik der Bonzen-, Trottel- und Lizenzträgerideologie, der gegenüber die Scholastik hypermodern und die Hexenprozesse universalhistorisch wirken“.

Anwürfe seiner „jüngsten Vergangenheit“ wegen lassen ihn kalt. Einem denunzierenden Journalisten teilt er mit: „Über mich können Sie schreiben, daß ich Kommandant von Dachau war oder mit Stubenfliegen Geschlechtsverkehr ausübe, von mir werden Sie keine Entgegnung vernehmen“. Und entschuldigt hat er sich nie.

Völlig falsch wäre es, Benns Haltung gegenüber dem NS als die eines Linksstehenden begreifen zu wollen. Was ihn von parteiförmigen Nationalsozialisten unterschied, läßt sich in derselben Weise von seinem Verhältnis zu den linksgerichteten Elementen sagen: eine erhabene Position gegenüber geistiger Konfektionsware und ein Bestehen auf der ehernen Reinheit des Wortes, das nicht im trüben Redefluß der Gasse untergehen soll. Im Todesjahr schreibt er: „Im Anfang war das Wort und nicht das Geschwätz, und am Ende wird nicht die Propaganda sein, sondern wieder das Wort. Das Wort, das bindet und schließt, das Wort der Genesis, das die Feste absondert von den Nebeln und den Wassern, das Wort, das die Schöpfung trägt.“

Bereits 1929 erregte Max Hermann-Neiße mit einer Rezension in der linksgerichteten „Neuen Bücherschau“ Aufsehen, in der er Benn anläßlich des Erscheinens seiner „Gesammelten Prosa“ so charakterisierte: „Es gibt auch in dieser Zeit des vielseitigen, wandlungsfähigen Machers, des literarischen Lieferanten politischer Propagandamaterialien, des schnellfertigen Gebrauchspoeten, in ein paar seltenen Exemplaren das Beispiel des unabhängigen und überlegenen Welt-Dichters, des Schöpfers eines nicht umfangreichen, aber desto schwerer wiegenden Werkes, das mit keinem anderen zu verwechseln ist.“ In dieser Distanz zur politischen Reklame liege aber nicht – und dies ist der entscheidende Punkt – ein Mindermaß an Radikalität, sondern vielmehr eine Größe, die weit über das kleinliche Tagesgeschehen hinausgehe: „Er macht den Schwindel nicht mit. Den hurtige, auf billigen Erfolg versessene Schreiber dieser niveaulosen Epoche schuldig zu sein glauben, sich dümmer stellen, als sie sind, und mit biederer Miene volkstümlich zu reden, wenn einem der Schnabel ganz anders und viel komplizierter wuchs. Und bleibt mit einem Stil, der das Gegenteil von populär ist, zuverlässiger, weiter gehend und weiter wirkend Revolutionär, als die wohlfeilen, marktschreierischen Funktionäre und Salontiroler des Propagandabuntdrucks. Statt des gewohnten ‚kleinen Formats’ der Sekretäre eines politischen Geplänkels um Macht- und Krippenvorteile spricht hier ein Rebell des Geistes, ein Aufruhrphilosoph, der in Kulturkreisen denkt und mit Jahrhundertputschen rechnet.“ Hermann-Neißes Darstellung rief bei den Kollegen des Redaktionskollegiums, den KPD-Funktionären Kisch und Becher, Empörung hervor. Beide traten unter verbalen Kanonaden aus der Schriftleitung aus, womit sie nachträglich bewiesen, zu eben jenen zu gehören, die kritisiert worden waren.

Zu einem gleichartigen Vorfall kam es zwei Jahre später, als Benn eine Rede zum sechzigsten Geburtstag Heinrich Manns auf einem Bankett des Schutzverbandes Deutscher Schriftsteller hielt und wenig später einen Essay über den Literaten veröffentlichte. Obgleich er viel Lobenswertes an ihm fand, bewies er erneut seinen klaren Blick, indem er feststellte, „daß harmlose junge Leute bei ihm den Begriff des nützlichen Schriftstellers ausliehen, mit dem sie sich etwas Rouge auflegten, in dem sie ganz vergehen vor Opportunismus und Soziabilität. Beides, was für Verdunkelungen!“ Nun war es so weit: beginnend mit dem schriftstellernden Architekten Werner Hegemann wurde das Etikett des „Faschisten“ an Benns tadellosen Anzug geklebt.

Der so Entlarvte antwortete mit einem Artikel in der „Vossischen Zeitung“ und mokierte sich, ob es ein Verbrechen sei, den Dichter als Dichter und nicht als Politiker zu feiern. „Und wenn man das in Deutschland und auf einem Fest der schriftstellerischen Welt nicht mehr tun kann, ohne von den Kollektivliteraten in dieser ungemein dreisten Weise öffentlich angerempelt zu werden, so stehen wir allerdings in einer neuen Metternichperiode, aber in diesem Fall nicht von seiten der Reaktion, sondern von einer anderen Seite her.“

Noch Jahre später, als Benn im Reich schon auf verlorenem Posten stand, versäumten es marxistische Ideologen nicht, ihn zu attackieren. 1937 brachte Alfred Kurella, der es einmal zum DDR-Kulturfunktionär bringen sollte, im Emigrantenblatt „Das Wort“ seine „Entrüstung“ über Benn zum Ausdruck und stellte fest, der Expressionismus sei „Gräßlich Altes“ und führe „in den Faschismus“.

Benn hatte seine weltanschauliche Verortung schon im Januar 1933 auf den Punkt gebracht, als eine linkstotalitäre Phalanx unter Führung Franz Werfels in der Deutschen Akademie den Antrag stellte, man müsse gegen Paul Fechters „Dichtung der Deutschen“ mit einem Manifest vorgehen. (Decker hierzu: „Nimmt man heute Paul Fechters Buch zur Hand, schüttelt man erstaunt den Kopf … Das große Skandalon, den Haß, die Geistfeindschaft, den Rassismus, gegen die eine ganze Dichterakademie glaubte protestieren zu müssen, sucht man in dem Buch vergeblich.“) Damals schrieb Benn in einer eigenen Manifestation: „Wer es also unternimmt, den denkenden, den forschenden, den gestaltenden Geist von irgendeinem machtpolitisch beschränkenden Gesichtswinkel aus einzuengen, in dem werden wir unseren Gegner sehen. Wer es gar wagen sollte, sich offen zu solcher Gegnerschaft zu bekennen und Geisteswerte wie etwas Nebensächliches oder gar Unnützes abzutun, oder sie als reine Tendenzwerte den aufgebauschten und nebelhaften Begriffen der Nationalität, allerdings nicht weniger der Internationalität, unterzuordnen, dem werden wir geschlossen unsere Vorstellung von vaterländischer Gesinnung entgegensetzen, die davon ausgeht, daß ein Volk sich … trägt … durch die immanente geistige Kraft, durch die produktive seelische Substanz, deren durch Freiheit wie Notwendigkeit gleichermaßen geprägte Werke … die Arbeit und den Besitz, die Fülle und die Zucht eines Volkes in die weiten Räume der menschlichen Geschichte tragen.“

In dieser Formulierung ist Benns Verständnis der Nation als eines geistig begründeten Raumes fokussiert. Unter Berufung auf die Großen der Vergangenheit (Schiller und Herder werden namentlich genannt) plädiert er schließlich für „unser drittes Reich“, weit oberhalb der von Klassen-, Massen- und Rassenpolitik durchfurchten Ebene.

Benn dachte nach 1933 nicht daran, Deutschland zu verlassen, und seine Meinung von denen, die es taten, war nie eine gute. 1949 schrieb er an Oelze: „Wer heutzutage die Emigranten noch ernst nimmt, der soll ruhig dabei bleiben … Sie hatten vier Jahre lang Zeit; alles lag ihnen zu Füßen, die Verlage, die Theater, die Zeitungen hofierten sie … aber per saldo ist doch gar nichts dabei zutage gekommen, kein Vers, kein Stück, kein Bild, das wirklich von Rang wäre“. Noch gegen Ende seines Lebens konstatierte er in Gegenwart von Freunden, die über die Grenzen gegangen waren, Emigration sei eine ganz und gar nutzlose Sache.

1948, als alle versuchen, sich als gute Schüler der Demokratie zu erweisen, wagt er es, im „Berliner Brief“ ebendieser „Vermittelmäßigungsmaschinerie“ für die künstlerische Existenz eine Absage zu erteilen: sie sei „zum Produktiven gewendet absurd. Ausdruck entsteht nicht durch Plenarbeschlüsse, sondern im Gegenteil durch Sichabsetzen von Abstimmungsergebnissen, er entsteht durch Gewaltakt in Isolation.“ Decker kommentiert lakonisch, es handle sich um „eine feine Unterscheidung, die ihm bis heute noch keiner widerlegt hat“, und: „Da ist er wieder, der Barbar, ohne den das Genie nicht vorkommt“.

Benns Geistesverwandtschaft mit Ernst Jünger ist hier unverkennbar, wenngleich vieles in Perspektive und Stilistik (im weitesten Wortsinne) die beiden trennt. Sie korrespondieren sparsam, doch bemerkt Benn 1950, „wie sehr sich seine und meine Gedankengänge z. T. berühren“, und berichtet über einen Besuch Jüngers – den wohl längsten, den er je zuhause gestattete: „Wir tranken ganz reichlich, und dabei kamen wir uns näher und wurden offen miteinander.“ So hat Decker recht, wenn er resummiert: „Sie haben gemeinsame Themen und im Alter eine ähnlich stoische Haltung zur Welt. Sie sehen in der Parteien-Demokratie einen untauglichen Versuch, das Überleben der Menschheit an der Schwelle zum 21. Jahrhundert zu sichern, verachten die Politik und kultivieren den Mythos als Erneuerung der Menschheit. Jüngers ‚Waldgänger’ und erst recht sein ‚Anarch’ sind Benns ‚Ptolemäer’ und dem ‚Radardenker’ verwandt.“

Der „Ptolemäer“, ein 1949 publizierter Essay, bekennt sich schon im Titel zu einem „erdzentrierten“, statischen Weltbild, dem jede Aufwärtsbewegung fremd ist. Diese treffliche Erkenntnis ist gleichwohl nicht mit Resignation zu verwechseln, sondern ruft zum Dasein nach eigenem Gesetz: „halte auch du dich in dem Land, in das dich deine Träume ziehen und in dem du da bist, die dir auferlegten Dinge schweigend zu vollenden“. Während die Masse im Strudel der Nichtigkeiten taumelt, ist es das Amt weniger, sich zu bewähren. In einer Vision des monologisierenden Sprechers findet sich das schöne Bild: „Die Orden, die Brüder werden vor dem Erlöschen noch einmal auferstehen. Ich sehe an Wassern und auf Bergen neue Athos und neue Monte Cassinos wachsen, – schwarze Kutten wandeln in stillem, in sich gekehrtem Gang.“

Als Exponent autonomen Künstlertums steht Benn beispielhaft gegen jede Art von Unterwerfung des Geistes unter politische Zwecke (was die Symbiose auf gleicher Höhe nicht ausschließt, also keineswegs eine apolitische Geistigkeit fordert). Damit ist er von der Ochlokratie unserer Tage ebenso weit entfernt wie von totalitären Systemen. „Was er nicht erträgt, ist eine falsche Gläubigkeit, die das Wesen der Kunst verkennt und diese auf ihre Nebenzwecke reduziert … Und eben inmitten von Konsum und Unterhaltung, den großen Verdurchschnittlichungsmächten, die aus der Verbindung von Kapitalismus und parlamentarischem System hervorgehen, schwindet das Wissen um diese elementare Gewalt der Kunst, die eine geistige Gegenwelt behauptet“ (Decker).

Heute ist der deutsche Nationalismus Äonen davon entfernt, die Hebel der Macht zu bedienen. Insofern stellt sich die Frage, ob er mit der Erfahrung der letzten siebzig Jahre gelernt habe, dem großen Einzelnen bedingungslose Freiheit zuzugestehen, nicht als praktische. Gegebenenfalls wird man einer geschichtlichen Verantwortung nur dann gerecht werden können, wenn nicht allein die „Banalität des Guten“ zugunsten einer „neuen deutschen Härte“ überwunden ist, sondern auch fatale Dummheiten nicht wiederholt werden – von denen Talleyrand bekanntlich gesagt hat, sie seien schlimmer als Verbrechen.

Heft 5/07 – „Gottfried Benn und sein Denken“ – Bewährungsprobe des Nationalismus von Arno Bogenhausen, S. 32 bis 37

Decker, Gunnar: Gottfried Benn. Genie und Barbar, Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2006, 544 S., 26,90 €

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : gottfried benn, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes, poésie, expressionnisme, allemagne, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://www.ernst-juenger.org/

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ernst jünger, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

A Guerra como Experiência Interior

"Para o soldado - escreve Philippe Masson em L'Homme en Guerre 1901-2001 - para o verdadeiro combatente, a guerra se identifica com estranhas associações, uma mescla de fascinação e horror, humor e tristeza, ternura e crueldade. No combate, o homem pode manifestar covardia ou uma loucura sanguinária. Encontra-se sujeito entre o instinto pela vida e o instinto mortal, pulsões que podem lhe conduzir à morte mais abjeta ou ao espírito de sacrifício.

"Para o soldado - escreve Philippe Masson em L'Homme en Guerre 1901-2001 - para o verdadeiro combatente, a guerra se identifica com estranhas associações, uma mescla de fascinação e horror, humor e tristeza, ternura e crueldade. No combate, o homem pode manifestar covardia ou uma loucura sanguinária. Encontra-se sujeito entre o instinto pela vida e o instinto mortal, pulsões que podem lhe conduzir à morte mais abjeta ou ao espírito de sacrifício.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Militaria, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, révolution conservatrice, ernst jünger, première guerre mondiale, littérature, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature allemande, militaria |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Vient de paraître : Le Bulletin célinien n°337. Au sommaire :

Vient de paraître : Le Bulletin célinien n°337. Au sommaire : On sait que les titres des brûlots céliniens font l’objet de contresens. Lors du colloque de février, à Beaubourg, un vétéran du célinisme voulut spécifier leur signification véritable. Tentative d’explication rejetée avec fracas. Feu mon ami Pierre Monnier, mobilisable en 1939, rappelait volontiers la bande de Bagatelles – « Pour bien rire dans les tranchées » –, afin d’indiquer de quel massacre il s’agissait dans l’esprit de Céline (1). Précision toujours d’actualité : pour beaucoup, dès lors qu’il s’agit de massacre sous la plume de Céline, cela ne peut être que celui des juifs.

On sait que les titres des brûlots céliniens font l’objet de contresens. Lors du colloque de février, à Beaubourg, un vétéran du célinisme voulut spécifier leur signification véritable. Tentative d’explication rejetée avec fracas. Feu mon ami Pierre Monnier, mobilisable en 1939, rappelait volontiers la bande de Bagatelles – « Pour bien rire dans les tranchées » –, afin d’indiquer de quel massacre il s’agissait dans l’esprit de Céline (1). Précision toujours d’actualité : pour beaucoup, dès lors qu’il s’agit de massacre sous la plume de Céline, cela ne peut être que celui des juifs.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : revue, céline, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

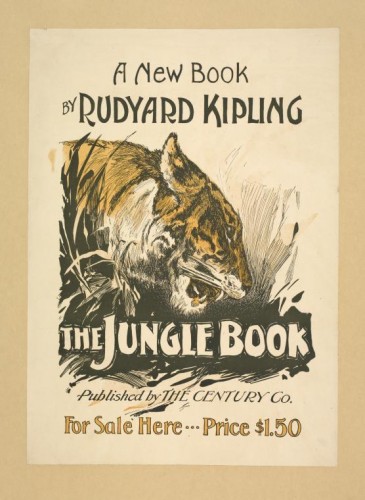

Rudyard Kipling:

The White Man’s Poet

By National Vanguard

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Editor’s Note:

Rudyard Kipling was born on December 30, 1865 and died on January 18, 1936. In commemoration of his birth, we are reprinting the following article from National Vanguard, March 1984. Share your favorite Kipling quotes and poems in the comments section. This version is from Irminsul’s Racial Nationalist Library [2] site. The poems quoted below are available in the Wordsworth Poetry Library edition of Rudyard Kipling, Collected Poems [3].

One hundred years ago, in Lahore—today the second city in independent Pakistan but then an administrative center in British India—a 17-year-old subeditor, fresh out of school in England, worked very hard to get out each day’s edition of the Civil and Military Gazette. His name was Rudyard Kipling.

Every now and then the young subeditor, with his editor’s assent, would fill up a little left-over space in the newspaper with a poem of his own composition, much to the annoyance of the Indian typesetters, who did not like to use the special typefaces which Kipling deemed appropriate to distinguish his poems from the prose around them. In 1886 he gathered up all of these poems from the previous three years and republished them in a book, under the title Departmental Ditties. The book was an immediate hit with other British colonials, and the first printing sold out very quickly.

Every now and then the young subeditor, with his editor’s assent, would fill up a little left-over space in the newspaper with a poem of his own composition, much to the annoyance of the Indian typesetters, who did not like to use the special typefaces which Kipling deemed appropriate to distinguish his poems from the prose around them. In 1886 he gathered up all of these poems from the previous three years and republished them in a book, under the title Departmental Ditties. The book was an immediate hit with other British colonials, and the first printing sold out very quickly.

Then it was one book after another, for from 1883 until his death in 1936 Kipling’s pen was seldom idle; hardly a week went by that he did not write one or more poems. Because his poetry expressed so well the common sentiment of the race—the deep soul-sense of men conscious of their breeding and of their responsibility to live up to a standard set by their forebears—it became very popular with his fellows. He was by far the most widely read—and the best-loved—poet writing in English at the beginning of this century; every cultured person in the English-speaking world was familiar with at least some of his poems. In 1907 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Kipling chose as his symbol—his personal rune—the swastika, the ancient Aryan sign of the sun and of health and of good fortune. Most editions of his works published in the first decades of this century are adorned with this symbol. Beginning in 1933, however, Jewish pressure was brought to bear against the publishers, and the swastikas were dropped from subsequent printings.

Kipling chose as his symbol—his personal rune—the swastika, the ancient Aryan sign of the sun and of health and of good fortune. Most editions of his works published in the first decades of this century are adorned with this symbol. Beginning in 1933, however, Jewish pressure was brought to bear against the publishers, and the swastikas were dropped from subsequent printings.

Unfortunately, the censorship did not end there. Kipling’s poetry was obnoxious to the new men who began tightening their grip on the cultural and informational media of the English-speaking world in the 1930s—obnoxious and dangerous. Actually, the whole spirit of Kipling’s writing was dangerous to them, totally at odds with the new spirit they were promoting so assiduously, but they could not simply ban all further publication of his works.

What they did instead was take measures to have dropped from new editions of his collected writings those of his poems and stories which expressed most explicitly the spirit and the ideas they feared: the spirit and the ideas of proud, free White men. Today every school child still reads a bit of Kipling’s poetry: such things as “Mandalay” and “FuzzyWuzzy” and “Gunga Din,” which superficially seem safely in tune with an age of multiracialism and “affirmative action” and White guilt.

But what American schoolchild has ever been given an opportunity to read Kipling’s “The Children’s Song”? The first two stanzas of that poem are:

Land of our Birth, we pledge to thee

Our love and toil in the years to be;

When we are grown and take our place,

As men and women with our race.

Father in Heaven who lovest all,

Oh help Thy children when they call;

That they may build from age to age,

An undefiled heritage.

There are many other Kipling poems, equally dangerous, which have been deleted from every edition of his works published since the Second World War. Here are three of them:

A Song of the White Men

Now, this is the cup the White Men drink

When they go to right a wrong,

And that is the cup of the old world’s hate–

Cruel and strained and strong.

We have drunk that cup—and a bitter, bitter cup

And tossed the dregs away.

But well for the world when the White Men drink

To the dawn of the White Man’s day!

Now, this is the road that the White Men tread

When they go to clean a land–

Iron underfoot and levin overhead

And the deep on either hand.

We have trod that road—and a wet and windy road

Our chosen star for guide.

Oh, well for the world when the White Men tread

Their highway side by side!

Now, this is the faith that the White Men hold

When they build their homes afar–

“Freedom for ourselves and freedom for our sons

And, failing freedom, War. ”

We have proved our faith—bear witness to our faith,

Dear souls of freemen slain!

Oh, well for the world when the White Men join

To prove their faith again!

The Stranger

The Stranger within my gate,

He may be true or kind,

But he does not talk my talk–

I cannot feel his mind.

I see the face and the eyes and the mouth,

But not the soul behind.

The men of my own stock

They may do ill or well,

But they tell the lies I am wonted to.

They are used to the lies I tell,

And we do not need interpreters

When we go to buy and sell.

The Stranger within my gates,

He may be evil or good,

But I cannot tell what powers control

What reasons sway his mood;

Nor when the Gods of his far-off land

Shall repossess his blood.

The men of my own stock,

Bitter bad they may be,

But, at least, they hear the things I hear,

And see the things I see;

And whatever I think of them and their likes

They think of the likes of me.

This was my father’s belief

And this is also mine:

Let the corn be all one sheaf–

And the grapes be all one vine,

Ere our children’s teeth are set on edge

By bitter bread and wine.

Song of the Fifth River

When first by Eden Tree,

The Four Great Rivers ran,

To each was appointed a Man

Her Prince and Ruler to be.

But after this was ordained,

(The ancient legends tell),

There came dark Israel,

For whom no River remained.

Then He Whom the Rivers obey

Said to him: “Fling on the ground

A handful of yellow clay,

And a Fifth Great River shall run,

Mightier than these Four,

In secret the Earth around;

And Her secret evermore,

Shall be shown to thee and thy Race.”

So it was said and done.

And, deep in the veins of Earth,

And, fed by a thousand springs

That comfort the market-place,

Or sap the power of Kings,

The Fifth Great River had birth,

Even as it was foretold

The Secret River of Gold!

And Israel laid down

His sceptre and his crown,

To brood on that River bank,

Where the waters flashed and sank,

And burrowed in earth and fell,

And bided a season below,

For reason that none might know,

Save only Israel.

He is Lord of the Last–

The Fifth, most wonderful, Flood.

He hears Her thunder past

And Her Song is in his blood.

He can foresay: “She will fall,”

For he knows which fountain dries

Behind which desert-belt

A thousand leagues to the South.

He can foresay: “She will rise.”

He knows what far snows melt

Along what mountain-wall

A thousand leagues to the North.

He snuffs the coming drouth

As he snuffs the coming rain.

He knows what each will bring forth,

And turns it to his gain.

A ruler without a Throne,

A Prince without a Sword,

Israel follows his quest.

In every land a guest,

Of many lands a lord,

In no land King is he.

But the Fifth Great River keeps

The secret of Her deeps

For Israel alone,

As it was ordered to be.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2011/12/rudyard-kipling-the-white-mans-poet-2/

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : rudyard kipling, littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Dystopia is Now!

By Jef Costello

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Whatever happened to the Age of Anxiety? In the post-war years, intellectuals left and right were constantly telling us — left and right — that we were living in an age of breakdown and decay. The pre-war gee-whiz futurists (who’d taken a few too many trips to the World’s Fair) had told us that in just a few years we’d be commuting to work in flying cars. The Cassandras didn’t really doubt that, but they foresaw that the people flying those cars would have no souls. We’d be men at the End of History, they told us; Last Men devoted only to the pursuit of pleasure — and quite possibly under the thumb of some totalitarian Nanny State that wanted to keep us that way. Where the futurists had seen utopia, the anti-futurists saw only dystopia. And they wrote novels, lots of them, and made films — and even one television show (The Prisoner).

But those days are over now. The market for dystopias has diminished considerably. The sense that something is very, very wrong, and getting worse – (something felt forty, fifty years ago even by ordinary people) has been replaced with a kind of bland, flat affect complacency. Why? Is it because the anxiety went away? Is it because things got better? Of course not. It’s because all those dire predictions came true. (Well, most of them anyway).

Dystopia is now, my friends! The future is where we are going to spend the rest of our lives. The Cassandras were right, after all. I am aware that you probably already think this. Why else would you be reading this website? But I’ll bet there’s a tiny part of you that resists what I’m saying — a tiny part that wants to say “Well, it’s not quite as bad as what they predicated. Not yet, anyway. We’ve got a few years to go before . . . uh . . . Maybe not in my lifetime . . .”

Here is the reason you think this: you believe that if it all really had come true and we really were living in dystopia, voices would be raised proclaiming this. The “intellectuals” who saw it coming decades ago would be shouting about it. If the worlds of Brave New World [2], Nineteen Eighty-Four [3]

, Fahrenheit 451 [4]

, and Atlas Shrugged [5]

really had converged and been made flesh, everyone would know it and the horror and indignation would bring it all tumbling down!

Well, I hate to disappoint you. Unfortunately, there’s this little thing called “human nature” that makes your expectations a tad unrealistic. When I was very young I discovered that there are two kinds of people. You see, I used to (and still do) spend a lot of time decrying “the way people are,” or “how people are today.” If I was talking to someone simpatico they would grin and nod in recognition of the truth I was uttering. Those are the people who (like me) didn’t think that “people” referred to them. But to my utterly naïve horror I discovered that plenty of people took umbrage at my disparaging remarks about “people.” They thought that “people” meant them. And, as it turns out, they were right. They were self-selecting sheep. In fact, this turned out to be my way of telling whether or not I was dealing with somebody “in the Matrix.”

Shockingly, people in the Matrix take a lot of pride in being in the Matrix. They don’t like negative remarks about “how things are today,” “today’s society,” or “America.” They are fully invested in “how things are”; fully identified with it. And they actually do (trust me on this) believe that how things are now is better than they’ve ever been. (Who do you think writes Mad Men?)

And that’s why nobody cares that they’re living in the Village. That’s why nobody cares that dystopia is now. Most of those old guys warning about the “age of anxiety” are dead. Their children and grandchildren were born and raised in dystopia, and it’s all that they know.

In the following remarks I will revisit some classic dystopian novels, and invite you to consider that we are now living in them.

1. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (1932)

This is, hands down, the best dystopian novel of all. It is set in a future age, after a great cataclysmic war between East and West, when Communism and assembly-line capitalism have fused into one holistic system. Characters are named “Marx” and “Lenina,” but they all revere “Our Ford.” Here we have Huxley anticipating Heidegger’s famous thesis of the “metaphysical identity” of capitalism and communism: both, in fact, are utterly materialistic; both have a “leveling effect.”

This is, hands down, the best dystopian novel of all. It is set in a future age, after a great cataclysmic war between East and West, when Communism and assembly-line capitalism have fused into one holistic system. Characters are named “Marx” and “Lenina,” but they all revere “Our Ford.” Here we have Huxley anticipating Heidegger’s famous thesis of the “metaphysical identity” of capitalism and communism: both, in fact, are utterly materialistic; both have a “leveling effect.”

When people discuss Brave New World, they tend to emphasize the “technological” aspects to the story: human beings hatched in test tubes, pre-sorted into “castes”; soma, Huxley’s answer to Zoloft and ecstasy all rolled into one; brainwashing people in their sleep through “hypnopedia”; visits to “the feelies” instead of the movies, where you “feel” everything happening on the screen, etc.

These things get emphasized for two reasons. First, some of them enable us to distance ourselves from the novel. I mean, after all, we can’t hatch people in test tubes (yet). We are not biologically designed to fit caste roles (yet). We don’t have “feelies” (virtual reality isn’t quite there – yet). So, we’re not living in Brave New World. Right? On the other hand, since we really have almost developed these things (and since we really do have soma), these facets of the novel can also allow us to admire Huxley’s prescience, and marvel a tad at how far we’ve come. The fantasies of yesteryear made reality! (Some sick souls feel rather proud of themselves when they read Brave New World.) But these responses are both defense mechanisms; strategies to evade the ways in which the novel really comes close to home. Without further ado, here they are:

The suppression of thumos: Thumos is “spiritedness.” According to Plato (in The Republic) it’s that aspect of us that responds to a challenge against our values. Thumos is what makes us want to beat up those TSA screeners who pat us down and put us through that machine that allows them to view our naughty bits. It’s an affront to our dignity, and makes us want to fight. Anyone who does not feel affronted in this situation is not really a human being. This is because it is really thumos that makes us human; that separates us from the beasts. (It’s not just that we’re smarter than them; our possession of thumos makes us different in kind from other animals.) Thumos is the thing in us that responds to ideals: it motivates us to fight for principles, and to strive to be more than we are. In Brave New World, all expressions of thumos have been ruthlessly suppressed. The world has been completely pacified. Healthy male expressions of spiritedness are considered pathological (boy, was Huxley a prophet!). (For more information on thumos read Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man – a much-misunderstood book, chiefly because most readers never get to its fifth and final part.)

Denigration of “transcendence.” “Transcendence” is my convenient term for what many would call the “religious impulse” in us. This part of the soul is a close cousin to thumos, as my readers will no doubt realize. In Brave New World, the desire for transcendence is considered pathological and addressed through the application of heavy doses of soma. Anyone feeling a bit religious simply pops a few pills and goes on a “trip.” (Sort of like the “trips” Huxley himself took – only without the Vedanta that allowed him to contextualize and interpret them.) In the novel, a white boy named John is rescued from one of the “Savage Reservations,” where the primitives are kept, and brought to “civilization.” His values and virtues are Traditional and he is horrified by the modern world. In one particularly memorable scene, he is placed in a classroom with other young people where they watch a film about penitents crawling on their knees to church and flagellating themselves. To John’s horror, the other kids all begin laughing hysterically. Religion is for losers, you see. How could anyone’s concerns rise above shopping? Which brings me to . . .

Consumerism. The citizens of Brave New World are inundated with consumer goods and encouraged to acquire as many as possible. Hypnopedia teaches them various slogans that are supposed to guide them through life, amongst which is “ending is better than mending.” In other words, if something breaks or tears, don’t fix it – just go out and buy a new one! (Sound familiar?) Happiness and contentment are linked to acquisition, and to . . .

Distractions: Drugs, Sex, Sports, Media. These people’s lives are so empty they have to be constantly distracted lest they actually reflect on this fact and become blue. Soma comes in very handy here. So does sex. Brave New World was a controversial book in its time, and was actually banned in some countries, because of its treatment of sex. In Huxley’s world of the future, promiscuity is encouraged. And it begins very early in life — very early (this was probably what shocked readers the most). Between orgasms, citizens are also encouraged to avail themselves of any number of popular sports, whether as participants or as spectators. (Huxley tantalizes us with references to such mysterious activities as “obstacle golf,” which he never really describes.) Evenings (prior to copulation) can be spent going to the aforementioned “feelies.”

The desacralization of sex and the denigration of the family. As implied by the above, in Brave New World sex is stripped of any sense of sacredness (and transcendence) and treated as meaningless recreation. Feelings of love and the desire for monogamy are considered perversions. Families have been abolished and words such as “mother” are considered obscene. Now, before you optimists point out that we haven’t “abolished” the family, consider what the vector is of all the left-wing attacks on it (it takes a village, comrades). And consider the fact that in the West the family has all but abolished itself. Marriage is now consciously seen by many as a temporary arrangement (even as a convenient merging of bank accounts), and so few couples are having children that, as Pat Buchanan will tell you, we are ceasing to exist. Why? Because children require too much sacrifice; too much time spent away from careering, boinking, tripping, and playing obstacle golf.

The cult of youth. Apparently, much of the inspiration for Brave New World came from a trip Huxley took to the United States, where aging is essentially regarded as a disease. In Brave New World, everyone is kept artificially young – pumped full of hormones and nipped and tucked periodically. When they reach about 60 their systems just can’t take it anymore and they collapse and die. Whereas John is treated as a celebrity, his mother is hidden from public view simply because she has grown old on the savage reservation, without the benefit of the artificial interventions the “moderns” undergo. Having never seen a naturally old person before, the citizens of Brave New World regard her with horror. But I’m guessing she probably didn’t look any worse than Brigitte Bardot does today. (Miss Bardot has never had plastic surgery).

The novel’s climax is a marvelous dialogue between John and the “World Controller.” The latter defends the world he has helped create, by arguing that it is free of war, competition, and disease. John argues that as bad as these things often are, they also bring out the best in people. Virtue and greatness are only produced through struggle.

As a piece of writing, Brave New World is not that impressive. But as a prophecy of things to come, it is utterly uncanny – and disturbingly on target. So much so that it had to be, in effect, suppressed by over-praising our next novel . . .

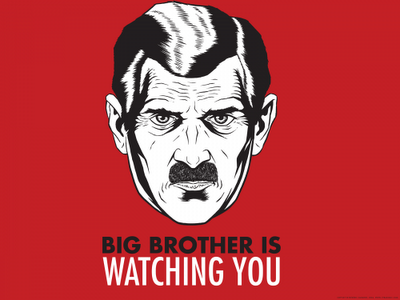

2. Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell (1948)

This is the most famous of all dystopian novels, and also the one that is least prescient. Like Brave New World, its literary qualities are not very impressive. It is chiefly remembered for its horrifying and bizarrely over-the-top portrayal of a future totalitarian society.

This is the most famous of all dystopian novels, and also the one that is least prescient. Like Brave New World, its literary qualities are not very impressive. It is chiefly remembered for its horrifying and bizarrely over-the-top portrayal of a future totalitarian society.

As just about everyone knows, in Nineteen Eighty-Four every aspect of society is controlled by “Big Brother” and his minions. All homes feature “telescreens” which cannot be shut off, and which contain cameras that observe one’s every move. The Ministry of Peace concerns itself with war, the Ministry of Love with terror, etc. Orwell includes slogans meant to parody Hegelian-Marxist dialectics: “war is peace,” “freedom is slavery,” ignorance is strength.” The language has been deliberately debased by “Newspeak,” dumbed-down and made politically correct. Those who commit “thoughtcrime” are taken to Room 101, where, in the end, they wind up loving Big Brother. And whatever you do, don’t do it to Julia, because the Women’s Anti-Sex League may get you. In short, things are double-plus bad. And downright Orwellian.

Let’s start with what Orwell got right. Yes, Newspeak reminds me of political correctness. (And Orwell’s analysis of how controlling language is a means to control thought is wonderfully insightful.) Then there is “doublethink,” which Orwell describes in the following way:

To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, to hold simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it, to believe that democracy was impossible and that the Party was the guardian of democracy, to forget, whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again, and above all, to apply the same process to the process itself — that was the ultimate subtlety; consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed.

This, of course, reminds me of the state of mind most people are in today when it comes to such matters as race, “diversity,” and sex differences.

The Women’s Anti-Sex League reminds me – you guessed it – of feminism. Then there is “thoughtcrime,” which is now a reality in Europe and Canada, and will soon be coming to America. (Speaking of Brigitte Bardot, did you know that she has been convicted five times of “inciting racial hatred,” simply for objecting to the Islamic invasion of France?) And yes, when I get searched at the airport, when I see all those security cameras on the streets, when I think of the Patriot Act and of “indefinite detention,” I do think of Orwell.

The Women’s Anti-Sex League reminds me – you guessed it – of feminism. Then there is “thoughtcrime,” which is now a reality in Europe and Canada, and will soon be coming to America. (Speaking of Brigitte Bardot, did you know that she has been convicted five times of “inciting racial hatred,” simply for objecting to the Islamic invasion of France?) And yes, when I get searched at the airport, when I see all those security cameras on the streets, when I think of the Patriot Act and of “indefinite detention,” I do think of Orwell.

But, for my money, Orwell was more wrong than right. Oceania was more or less a parody of Stalin’s U.S.S.R. (Come to think of it, North Korea is sort of a parody of Stalin’s U.S.S.R., isn’t it? It’s as if Kim Il-Sung read Nineteen Eight-Four and thought “You know, this could work . . .”) But Orwell would never have believed it if you’d told him that the U.S.S.R. would be history a mere four decades or so after his book was published. Soft totalitarianism, not hard, was the wave of the future. Rapacious, unbridled capitalism was the future, not central planning. Mindless self-indulgence and phony “individualism” were our destiny, not party discipline and self-sacrifice. The future, it turned out, was dressed in Prada, not Carhartt. And this is really why Brave New World is so superior to Nineteen Eighty-Four. We are controlled primarily through our vices, not through terror.

The best description I have encountered of the differences between the two novels comes from Neil Postman’s book Amusing Ourselves to Death:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egotism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny “failed to take into account man’s almost infinite appetite for distractions.” In 1984, Orwell added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we fear will ruin us. Huxley feared that our desire will ruin us.

And here is Christopher Hitchens (in his essay “Why Americans are not Taught History”) on the differences between the two novels:

We dwell in a present-tense culture that somehow, significantly, decided to employ the telling expression “You’re history” as a choice reprobation or insult, and thus elected to speak forgotten volumes about itself. By that standard, the forbidding dystopia of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four already belongs, both as a text and as a date, with Ur and Mycenae, while the hedonist nihilism of Huxley still beckons toward a painless, amusement-sodden, and stress-free consensus. Orwell’s was a house of horrors. He seemed to strain credulity because he posited a regime that would go to any lengths to own and possess history, to rewrite and construct it, and to inculcate it by means of coercion. Whereas Huxley . . . rightly foresaw that any such regime could break but could not bend. In 1988, four years after 1984, the Soviet Union scrapped its official history curriculum and announced that a newly authorized version was somewhere in the works. This was the precise moment when the regime conceded its own extinction. For true blissed-out and vacant servitude, though, you need an otherwise sophisticated society where no serious history is taught.

I believe this just about says it all.

3. Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1953)

This one is much simpler. A future society in which books have been banned. Now that all the houses are fireproof, firemen go around ferreting out contraband books from backward “book people” and burning them. So, what do the majority of the people do with themselves if they aren’t allowed to read? Why, exactly what they do today. They watch television. A lot of television.

This one is much simpler. A future society in which books have been banned. Now that all the houses are fireproof, firemen go around ferreting out contraband books from backward “book people” and burning them. So, what do the majority of the people do with themselves if they aren’t allowed to read? Why, exactly what they do today. They watch television. A lot of television.

I read Fahrenheit 451 after seeing the film version by Francois Truffaut. I have to admit that after seeing the film I was a bit disappointed by the book. (This would be regarded as heresy by Bradbury fans, who all see the film as far inferior.) I only dimly recall the book, as the film manages to be more immediately relevant to current pathologies than the book does (perhaps because the film was made fourteen years later, in 1967).

I vividly remember the scene in the film in which Linda, Montag the fireman’s wife, asks for a second “wallscreen” (obviously an Orwell influence). “They say that when you get your second wallscreen it’s like having your family grow out around you,” she gushes. Then there’s the scene where a neighbor explains to Montag why his new friend Clarisse (actually, one of the “book people”) is so different. “Look there,” the neighbor says, pointing to the television antenna on top of one of the houses. “And there . . . and there,” she says, pointing out other antennae. Then she indicates Clarisse’s house, where there is no antenna (she and her uncle don’t watch TV). “But look there . . . there’s . . . nothing,” says the neighbor, with a blank, bovine quality.

Equally memorable was a scene on board a monorail (accompanied by haunting music from Bernard Herrmann). Montag watches as the passengers touch themselves gently, as if exploring their own sensations for the very first time, while staring off into space with a kind of melancholy absence in their eyes. Truffaut goes Bradbury one better, by portraying this future as one in which people are numb; insensitive not just to emotions but even to physical sensations. In an even more striking scene, Montag reduces one of Linda’s friends to tears, simply by reading aloud an emotionally powerful passage from David Copperfield. The response from her concerned friends? “Novels are sick. All those idiotic words. Evil words that hurt people. Why disturb people with that sort of filth? Poor Doris.”

What Bradbury didn’t forsee was a future where there would be no need for the government to ban books, because people would just voluntarily stop reading them. Again, Huxley was more prescient. Lightly paraphrasing Neil Postman (from the earlier quotation), “What Bradbury feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one.” Still, you’ve got to hand it to Bradbury. Although books still exist and nobody (at least not in America) is banning them, otherwise the world of today is pretty much the world of Fahrenheit 451.

No one reads books anymore. Many of our college graduates can barely read, even if they wanted to. Everywhere bookstores are closing up. Explore the few that still exist and you’ll see that the garbage they sell hardly passes as literature. (Today’s bestsellers are so badly written it’s astonishing.) It’s always been the case in America that most people didn’t read a lot, and only read good books when forced to. But it used to be that people felt just a little bit ashamed of that. Things are very different today. A kind of militant proletarian philistinism reigns. The booboisie now openly flaunt their ignorance and vulgarity as if these were virtues. It used to be that average Americans paid lip service to the importance of high culture, but secretly thought it a waste of time. Now they openly proclaim this, and regard those with cultivated tastes as a rather curious species of useless loser.

Nobody needs to ban books. We’ve made ourselves too stupid to deserve them.

4. Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand (1957)

Atlas Shrugged changed my life.

Atlas Shrugged changed my life.

You’ve heard that before, right? But it’s true. I read this novel when I was twenty years old, and it was a revelation to me. I’ve since moved far away from Rand’s philosophy, but there’s a part of me that still loves and admires this book, and its author. And now I’ll commit an even worse heresy than saying I liked the film of Fahrenheit 451 more than the book: I think that, purely as a piece of prose fiction, Atlas Shrugged is the best of the four novels I’m considering here. I don’t mean that it’s more prescient or philosophically richer. I just mean that it’s a better piece of writing. True, it’s not as good a book as The Fountainhead, and it’s deformed by excesses of all kinds (including a speech by one character that lasts for . . . gulp . . . sixty pages). Nevertheless, Rand could be a truly great writer, when she wasn’t surrounded by sycophants who burbled affirmatively over every phrase she jotted (even when it was something like “hamburger sandwich” or “Brothers, you asked for it!”).

Atlas Shrugged depicts an America in the not-so-distant future. Collectivism has run rampant, and government regulation is driving the economy into the ground. The recent godawful film version of the first third of the novel (do yourself a big favor and don’t see it) emphasizes this issue of government regulation at the expense of Rand’s other, more important messages. (Rand was not simply a female Milton Friedman.) Rand’s analysis of the roots of socialism is fundamentally Nietzschean, though she would not admit this. It is “hatred of the good for being the good” that drives people in the world of Atlas Shrugged to redistribute wealth, nationalize industries, and subsidize lavish homes for subnormal children. And at the root of this slave morality (which Rand somewhat superficially dubs “altruism”) is a kind of primal, life-denying irrationalism. Rand’s solution? A morality of reason, where recognition that A is A, that facts are facts, is the primary commandment. This morality is preached by Rand’s prophet, John Galt, who is the leader of a secret band of producers and innovators who have “gone on strike,” refusing to let the world’s parasites feed off of them.

Despite all her errors (too many to mention here) there’s actually a great deal of truth in Rand’s analysis of what’s wrong with the world. Simply put, Rand was right because Nietzsche was right. And yes, we are living in the world of Atlas Shrugged. But the real key to seeing why this novel is relevant to today lies in a single concept that is never explored in Atlas Shrugged or in any of the other novels discussed here: race.

[12]Virtually everything Rand warned about in Atlas Shrugged has come to pass, but it’s even worse than she thought it was going to be. For our purveyors of slave morality are not just out to pillage the productive people, they’re out to destroy the entire white race and western culture as such. Rand was an opponent of “racism,” which she attacked in an essay as “barnyard collectivism.” Like the leftists, she apparently saw human beings as interchangeable units, each with infinite potential. Yes, she was a great elitist – but she believed that people became moochers and looters and parasites because they had “bad premises,” and had made bad choices. Whatever character flaws they might have were changeable, she thought. Rand was adamantly opposed to any form of biological determinism.

Miss Rand (born Alyssa Rosenbaum) failed to see that all the qualities she admired in the productive “men of the mind” – their Apollonian reason, their spirit of adventure, their benevolent sense of life, their chiseled Gary Cooperish features – were all qualities chiefly of white Europeans. There simply are no black or Chinese or Hispanic John Galts. The real way to “stop the motor of the world” is to dispossess all the white people, and this is exactly what the real-life Ellsworth Tooheys and Bertram Scudders are up to today.

Atlas Shrugged, Brave New World, Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Fahrenheit 451 all depict white, racially homogeneous societies. Non-whites simply do not figure at all. Okay, yes, there might be a reference somewhere in Atlas Shrugged to a “Negro porter,” and perhaps something similar in the other books. But none of the characters in these novels is non-white, and non-whites are so far in the background they may as well not exist for these authors. Huxley thought that if we wanted epsilon semi-morons to do our dirty work the government would have to hatch them in test tubes. Obviously, he had just never visited Detroit or Atlanta. Epsilon semi-morons are reproducing themselves every day, and at a rate that far outstrips that of the alphas.

These authors foresaw much of today’s dystopian world: its spiritual and moral emptiness, its culture of consumerism, its flat-souled Last Manishness, its debasement of language, its doublethink, its illiteracy, and its bovine tolerance of authoritarian indignities. But they did not foresee the most serious and catastrophic of today’s problems: the eminent destruction of whites, and western culture.

None of them thought to deal with race at all. Why is this? Probably for the simple reason that it never occurred to any of them that whites might take slave morality so far as to actually will their own destruction. As always, the truth is stranger than fiction.

The dystopian novel most relevant to our situation is also – surprise! – the one that practically no one has heard of: Jean Raspail’s The Camp of the Saints [13]. But that is a subject (perhaps) for another essay . . .

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2012/01/dystopia-is-now/

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : contre-utopie, dystopie, littérature, lettres, philosophie, lettres anglaises, lettres américaines, littérature anglaise, littérature américaine, orwell, huslay, ray bradbury, ayn rand |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Céline contre le Spectacle par Stéphane Zagdanski

« Savez-vous ce que l'on demande d'abord à un fou lorsqu'il arrive à l'hôpital ? L'heure qu'il est et où il se trouve. L'heure, je peux vous la dire: onze heures du matin, et c'est aujourd'hui dimanche. Où je me trouve ? Eh bien ! dans un monde de cinglés où il faut vraiment faire un effort pour garder son bon sens, un effort de modestie, surtout ! Nous sommes au siècle de la publicité et la publicité compte désormais plus que l'objet. »

« Savez-vous ce que l'on demande d'abord à un fou lorsqu'il arrive à l'hôpital ? L'heure qu'il est et où il se trouve. L'heure, je peux vous la dire: onze heures du matin, et c'est aujourd'hui dimanche. Où je me trouve ? Eh bien ! dans un monde de cinglés où il faut vraiment faire un effort pour garder son bon sens, un effort de modestie, surtout ! Nous sommes au siècle de la publicité et la publicité compte désormais plus que l'objet. »

00:11 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises, céline |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Le blog "Les 8 plumes" a décidé de rendre hommage à Céline sous la forme d'un abécédaire :

Le blog "Les 8 plumes" a décidé de rendre hommage à Céline sous la forme d'un abécédaire :

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, céline |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les éditions du Lérot publient une version préparatoire et le texte définitif de Mea Culpa de Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Une édition d’Henri Godard avec la reproduction intégrale du manuscrit. 104 pages, au format du manuscrit 21x27 cm. Tirage limité à 300 ex. numérotés, 50 euros. Nous reproduisons ci-dessous l'avant-propos d'Henri Godard.

Les éditions du Lérot publient une version préparatoire et le texte définitif de Mea Culpa de Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Une édition d’Henri Godard avec la reproduction intégrale du manuscrit. 104 pages, au format du manuscrit 21x27 cm. Tirage limité à 300 ex. numérotés, 50 euros. Nous reproduisons ci-dessous l'avant-propos d'Henri Godard.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises, céline |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://metapoinfos.hautetfort.com

Les éditions Orizons ont publié en début d'année un essai de Michel Arouimi intitulé Jünger et ses dieux. Michel Arouimi est maître de conférence en littérature comparée à l'Université du Littoral de la région Nord-Pas-de-Calais.

"Le sens du sacré, chez Ernst Jünger, s'est d'abord nourri de l'expérience de la guerre, ressentie comme une manifestation de la violence que le sacré, dans ses formes connues, semble conjurer. D'où le désir, toujours plus affirmé chez Jünger, d'une nouvelle transcendance. Mieux que dans ses pensées philosophiques, ces problèmes se poétisent dans ses grands romans, où revivent les mythes dits premiers. Or, ces romans sont encore le prétexte d'un questionnement des pouvoirs de l'art, pas seulement littéraire. Dans la maîtrise des formes qui lui est consubstantiel, l'art apparaît comme une réponse aux mêmes problèmes que s'efforce de résoudre le sacré. La réflexion de Jünger sur l'ambiguïté du sens de ces formes semble guidée par certains de ses modèles littéraires. Rimbaud a d'ailleurs laissé moins de traces dans son oeuvre que Joseph Conrad et surtout Herman Melville, dont le BillyBudd serait une source méconnue du Lance-pierres de Jünger. La fréquentation de ses " dieux littéraires ", parmi lesquels on peut compter Edgar Poe et Marcel Proust. a encore permis à Jünger d'affiner son intuition de l'ordre mystérieux qui s'illustre aussi bien dans la genèse de l'oeuvre écrite que dans un destin humain."

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ernst jünger, livre, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

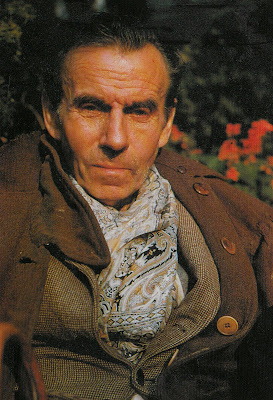

Jünger, una vita vissuta come esperienza primordiale

Ex: http://www.centrostudilaruna.it/

Quando nelle conversazioni con il vecchio Jünger si toccava l’immancabile motivo della Grande Guerra, sul suo volto imperturbabile si disegnava una leggera espressione di insofferenza. Con gli interlocutori più giovani, digiuni di esperienze militari, essa volgeva rapidamente in benevola comprensione.

Perché ecco la domanda che la mimica del volto bastava a esplicitare ridurre l’opera di una vita al suo primo episodio? Perché, nonostante egli avesse continuato a pensare e a scrivere per oltre mezzo secolo, la critica incollava così pervicacemente la sua immagine all’attivismo eroico degli inizi?

La fama precoce ottenuta con i diari di guerra lo ha effettivamente inseguito come un’ombra. E se in origine essa contribuì a dare la massima visibilità alla sua intera produzione, letteraria e saggistica, in seguito ne ha pesantemente condizionato la ricezione, ostacolando una più attenta considerazione delle profonde trasformazioni, di contenuto e di stile, avvenute nel corso degli anni. Perfino il raffinato Borges ricordava di lui soltanto Bajo la tormenta de acero, e nient’altro. Il tenente Sturm, un racconto in gran parte autobiografico, pubblicato a puntate nel 1923 e ora tradotto da Alessandra Iadicicco per Guanda, ci riporta a quel primo Jünger, offrendo uno splendido condensato dei motivi che resero così incisiva la sua elaborazione letteraria della guerra. Di nuovo ammiriamo il talento con cui il giovane scrittore avvince anche il lettore più distratto e, con la sola forza della descrizione, lo porta a toccare quell’esperienza limite. Di nuovo la sua prosa, così scandalosamente indifferente a carneficine e distruzioni, evoca le “battaglie di materiali” in cui il valore del combattente è ridotto a zero e ciò che conta è solo la potenza di fuoco “per metro quadro”. La prospettiva di Jünger scardina le tradizionali interpretazioni della guerra per esibirci il fenomeno allo stato puro. Dove altri vedevano allora la lotta per la patria, gli interessi del capitalismo o le rivendicazioni dello chauvinismo, egli coglie l’esperienza primordiale in cui la vita scopre le sue carte, in cui, nel suo pericoloso sporgersi verso l’insensato nulla, essa manifesta la sua essenza più profonda e contraddittoria. Fino all’assurdo caso, evocato nel racconto, del “camerata” che viene spinto dal terrore della morte a suicidarsi. Dal suo lungo stare in tali situazioni limite la letteratura di Jünger trae indubbiamente la sua forza: da inchiostro, si fa vita. Ma sarebbe riduttivo costringerla lì. Sulle scogliere di marmo, per esempio, per lo scenario fantastico, il timbro stilistico e la tensione narrativa va ben oltre la diaristica di guerra. E così pure altri testi, primo fra tutti lo stupendo Visita a Godenholm del 1952, che attende ancora di essere tradotto.

La fama precoce ottenuta con i diari di guerra lo ha effettivamente inseguito come un’ombra. E se in origine essa contribuì a dare la massima visibilità alla sua intera produzione, letteraria e saggistica, in seguito ne ha pesantemente condizionato la ricezione, ostacolando una più attenta considerazione delle profonde trasformazioni, di contenuto e di stile, avvenute nel corso degli anni. Perfino il raffinato Borges ricordava di lui soltanto Bajo la tormenta de acero, e nient’altro. Il tenente Sturm, un racconto in gran parte autobiografico, pubblicato a puntate nel 1923 e ora tradotto da Alessandra Iadicicco per Guanda, ci riporta a quel primo Jünger, offrendo uno splendido condensato dei motivi che resero così incisiva la sua elaborazione letteraria della guerra. Di nuovo ammiriamo il talento con cui il giovane scrittore avvince anche il lettore più distratto e, con la sola forza della descrizione, lo porta a toccare quell’esperienza limite. Di nuovo la sua prosa, così scandalosamente indifferente a carneficine e distruzioni, evoca le “battaglie di materiali” in cui il valore del combattente è ridotto a zero e ciò che conta è solo la potenza di fuoco “per metro quadro”. La prospettiva di Jünger scardina le tradizionali interpretazioni della guerra per esibirci il fenomeno allo stato puro. Dove altri vedevano allora la lotta per la patria, gli interessi del capitalismo o le rivendicazioni dello chauvinismo, egli coglie l’esperienza primordiale in cui la vita scopre le sue carte, in cui, nel suo pericoloso sporgersi verso l’insensato nulla, essa manifesta la sua essenza più profonda e contraddittoria. Fino all’assurdo caso, evocato nel racconto, del “camerata” che viene spinto dal terrore della morte a suicidarsi. Dal suo lungo stare in tali situazioni limite la letteratura di Jünger trae indubbiamente la sua forza: da inchiostro, si fa vita. Ma sarebbe riduttivo costringerla lì. Sulle scogliere di marmo, per esempio, per lo scenario fantastico, il timbro stilistico e la tensione narrativa va ben oltre la diaristica di guerra. E così pure altri testi, primo fra tutti lo stupendo Visita a Godenholm del 1952, che attende ancora di essere tradotto.

* * *

Tratto da Repubblica del 2 novembre 2000.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : révolution conservatrice, allemagne, weimar, ernst jünger, littérature, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature allemande |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Le mystère des Anneaux

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature anglaise, tolkien, angleterre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

| Souverän ist, wer Kalender liest. Biograph Holger Hof über den Notizbuchführer Gottfried Benn |

| Geschrieben von: Till Röcke |

| Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de/ |

|