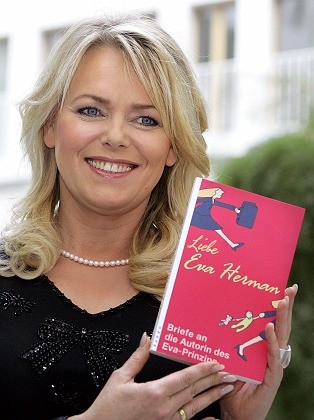

Kay S. Hymowitz

Manning Up: How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men into Boys

New York: Basic Books, 2011

I expected this book to be a diatribe against the often-discussed “loser” men—those who, not having any marketable skill, are still living off their parents into mid-life. Manning Up actually is about a new demographic, the SYM (single young male), its female counterpart, and what factors led to the decline in marriage and number of children in the Western world. Simply having a job is not enough to be a man in the author’s view; true adulthood means being married and having children. Most young men and women are what she calls “preadults.”

Kay S. Hymowitz, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, has written extensively on issues of marriage, the sexes, class, and race, and she appears to be genuinely concerned about the declining rates in marriage childbirth. Her stance is slanted in favor of women, but she is sympathetic to the plight of men today. She mentions that boys are often discriminated against and ignored in favor of women. While funds pour in to increase girls’ math and science scores, boys are not given special treatment to improve their reading scores. She cites a BusinessWeek story that explains today’s young men as a “payback generation” intended to “compensate for the advantages given to males in the past.”

The Shift to the Feminine, Knowledge Economy

Scholars attribute women’s entry into the workforce largely to innovations in science and technology in the twentieth century. With no need to can food, make bread, weave, or sew, women were not “needed” at home the way they were in every generation past. They were having fewer children, too, due to birth control: In the early 1800s, white women had an average of seven children. By 1900, it was 3.56. When the birth control pill was introduced in the 1960s, state laws “kept the drug away from unmarried women.” Economist Martha Baily showed that when a state changed its law, there was a decline in the percentage of young women who gave birth by age 22, and an increase in the number of young women in the labor force and the hours they worked.

The number of working women (ages 33 to 45) went from 25 percent in 1950, to 46 percent in 1970, to about 60 percent since 1995. But in the 1950s to ’70s, women tended to work to help pay the bills, often as secretaries, waitresses, nurses, teachers, and librarians. Today’s young women set out in the world to find their “passion” not in a husband, but in a career.

The shift from secretary to major player in corporate America, Hymowitz explains, was largely due to a shift from an industrial economy to a knowledge economy. By the 1980s, the economy was booming as manufacturing jobs decreased and millions of positions opened in fields like public relations, health, and law. Women, too weak physically to participate much in the industrial economy, could do almost any job in the knowledge economy.

One example given is design. As technology advanced, designers transitioned from working with their hands (and making lasting work as is found in Bauhaus and Art Nouveau) to being hands-off fashion designers, who no longer needed to learn drafting, typesetting, drawing, or how to use heavy equipment. Using cheap labor overseas meant many more products, and thus a greater need for marketing and advertising. Women now make up 60 percent of design students, once a male-dominated field.

New industries sprouted up, too, as increased wealth and leisure time demanded workers at yoga centers, spas, travel companies, and more marketing and ad agencies for these specialty industries—all areas in which women participate as easily as men. Working women had new needs and money to spend, so more industries sprouted up to create feminine business suits, trendy lunch spots, meal “helpers,” stylish computer bags, $400 work pumps, $5 lattes, spa treatments and scented candles to help women unwind, houses with bathrooms the size of our grandparents’ bedrooms, a variety of products in the color pink, and right-hand rings for women who want to buy themselves a diamond. Other women entered the design arena through boutique companies: making jewelry, crafts, or custom stationary.

Nation-building and culture-building thus fell out of the workforce, replaced by sales, marketing, and fashion.

Today, men outnumber women in fields like construction (88 percent), while women make up 51 percent of management and professionals, particularly in fields like Human Resources, Public Relations, and finance. Women make up 77 percent of workers in education and health services. Women are more likely to work at the numerous new nonprofits, and make up 78 percent of psychology majors, 61 percent of humanities majors, and 60 percent of social and behavioral science doctorates. Publishing has long had high numbers of women workers, but now women have moved from what Hymowitz calls the “ladies’ magazines ghettos” to political commentary.

While women moved into the knowledge economy, men remained in behind-the-scenes fields that required more technical skill: jobs like writing code and IT. Some men flocked to jobs at ESPN, Cartoon Network, microbreweries, and video game design firms. Other men knew that even in the midst of feminism, their wives would still want the option to stay home and raise children (so long as men didn’t tell them they had to), and concentrated on high-paying jobs rather than following their bliss.

In the early nineteenth century, most men worked for themselves, as farmers, small merchants, or tradesmen. But by the end of the nineteenth century, two-thirds were working for “the man.” Some experts believe that it’s women who will soon be “running the place,” since the knowledge economy workplace “requires a more feminine style of leadership.” Employers will increasingly placate women, who are not solely concerned with the bottom line as a measure of their career success, but also want a job where they “help others,” enjoy relationships with colleagues, get recognition, have flexibility, and are in an environment of “collaboration and teamwork.” More women in the workplace means that it is more genteel and less of a man’s club: Swearing and spitting are forbidden, and men are now in a domesticated atmosphere both at home and at work. The popularity of psychoanalysis means that men and women alike are trained to listen sympathetically, be sensitive to emotions, and control their anger.

To explain the dynamics of the knowledge economy, Hymowitz references a 2002 paper by Harvard economist Brian Jacob called “Where the Boys Aren’t.” He found that girls are better at noncognitive tasks, such as keeping track of homework, working well with others, and organization, and suggests that such skills may explain the gender gap in high school grades and college admissions (women have higher GPAs and are 58 percent of college graduates, but they lag behind men in math SAT scores). These cognitive skills also are important for success in today’s feminized workplace.

Though not mentioned in Manning Up, these skills are also ones for which men have traditionally relied on women: organizing the home, keeping track of appointments, and being the family PR rep and social coordinator. Today’s women benefit in the career-world, as more jobs require good communication skills and “EQ” (emotional intelligence), while men are left with lower paying jobs and the added disadvantage of no wife at home.

SYMs: The New Demographic

In 1970, 80 percent of men aged 25–29 were married, compared to 40 percent in 2007. In 1970, 85 percent of men aged 30–34 were married, compared to 60 percent in 2007.

This new single-young-male demographic used to be called “elusive,” since it was a difficult advertising target. Then Maxim arrived in America in 1997, and seemed to have the answers to what SYMs wanted. Its readership reached 2.5 million in 2009, more than the combined circulation of GQ, Men’s Journal, and Esquire. Hymowitz says other magazines, like Playboy and Esquire, tried to project the “image of an intelligent, cultured, and au courant sort of man.” Even though Playboy promoted the image of the eternal bachelor, he was at least an intelligent and sophisticated bachelor. (Hugh Hefner wrote that his readers enjoyed “inviting a female acquaintance in for a quiet discussion of Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.”) Maxim, however, catered to the man who didn’t want to grow up.

Hymowitz doesn’t buy into the idea that the masses of men are moved by the media (or an inner party seeking to destroy them, let alone any subversive forces dominant in the Kali Yuga). She instead posits that products like Maxim were developed for an existing market.

Regardless of the reason, a number of TV shows were created with the SYM in mind, starting with The Simpsons. Comedy Central brought out South Park and The Man Show, while the Cartoon Network promoted cartoons for grown men. More films featured SYM stars like Will Ferrell, Ben Stiller, Jim Carrey, and Jack Black, and movies like 2003’s Old School (30-somethings who start a fraternity) were popular. American men ages 18–34 are now the biggest users of video games, with 48.2 percent owning a console and playing an average of 2 hours and 43 minutes per day. That doesn’t include online games like World of Warcraft.

Hymowitz recounts the numerous silly Adam Sandler movies, in which he plays a stereotypical young adult, male loser. Meanwhile, the media’s counter-image for women is the well-heeled, single young female:

If she is ambitious, he is a slacker. If she is hyper-organized and self-directed, he tends toward passivity and vagueness. If she is preternaturally mature, he is happily not. Their opposition is stylistic as well: she drinks sophisticated cocktails in mirrored bars, he burps up beer on ratty sofas. She spends her hard-earned money on mani-pedi outings, his goes toward World of Warcraft and gadgets.

It’s in this chapter that Hymowitz’s double-standard for men and women is most apparent, and annoying. She seems to think that when single women spend money for clothes and pedicures, it’s women’s empowerment, but single men who spend money on guy-flicks and video games are childish. Both cases seem to me examples of adults who, instead of having children, make themselves into the child: men by continuing all the games and comic books of their youth, and women by playing Barbie doll with themselves.

So if simply cutting the financial apron strings doesn’t make one a man, what does? Hymowitz answers by looking to masculine virtues throughout all cultures: “strength, courage, resolve, and sexual potency,” but that one line is about the extent of the analysis. She is careful to distinguish between having sex (which single men do a lot these days) and “manning up” by being married and becoming the head of a family.

But even when men do settle down, the roles they play as fathers have changed. Rather than being a strong father figure, today’s father often relates to his children by “accentuating his own immaturity,” according to Gary Cross, author of Men to Boys: The Making of Modern Immaturity. Whether they want to or not, middle-class men are often “expected to bring home a spirit of playfulness that would have scandalized their own patriarchal fathers.” The middle-class home has became more child-centric, even with fewer children in it, and both sexes are expected to project “warmth, nurturing, and gentleness.”

With high divorce rates, many young men today were raised in matriarchal family environments, which may be one contributing factor to the “unmanliness” of some of today’s men. Instead of having their own families, some men instead play the role of the “fun uncle,” like men in matriarchal, non-white societies.

A Different Dating World

After college, all of these single young people embark on a journey more confusing than if they started a family: modern dating, now with websites that describe the etiquette for one-night stands (it’s “leave quickly”).

Men and women are both confused by the new rituals, and the lack thereof. A man who inadvertently insults a girl by not opening her car door may have been chastised by his last girlfriend for doing just that. Women sometimes “pick up” guys (whether at bars, or actually driving to pick them up for dates), and there is ambiguity about who pays for dates when SYFs outearn SYMs in the majority of large cities. Men experience the nice-guy conundrum when they see girls dating jerks. Meanwhile, women practice a Zen-like nonattachment when dating, since bringing up marriage before a year of sex seems to turn men off.

Hymowitz recounts a number of events from the childhood of young women that play into their behavior as adults: Today’s SYFs were often told by their mothers that they shouldn’t need a man to be happy. They were likely raised in the 1990s, in the midst of a tween-based advertising frenzy that marketed make-up, thong underwear, and high-heeled clogs to preteens, while at the same time trying to “save the self-esteem” of young girls. Popular TV shows for girls were based on the female warrior type: The Powerpuff Girls, Xena: Warrior Princess, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. These women try to convince themselves for years that they shouldn’t “need” a child or husband, then end up debating whether to become a “choice mother” (the new term for a woman who uses sperm bank).

* * *

Manning Up might be a good “beach book” for women readers of Counter-Currents, but I have trouble imagining men enjoying it, though they would find some insights into the mind of the typical woman. I found it interesting for its wealth of statistics about marriage rates and ages, men and women in the workplace and universities, and summaries of various causes that contributed to the (mostly white) single and childless young men and women today.

There have been numerous debates on Counter-Currents and other websites about what exactly has caused the decline in marriage and childbirth. Manning Up does a good job of touching on some of the contributing forces, but never addresses any of the larger forces.

The good news from Manning Up is that the majority of young men and women still want to get married and have children. In addition, while women in their early 20s are “hot commodities,” by the time they reach 30, they are beginning to get desperate and may “settle for Mr. Good Enough” as the subtitle of the book Marry Him advises. More good news lies in the fact that young people today are scrambling for any advice whatsoever about how to successfully date and marry, revealing a large market for New Righters and Traditionalists to step into to help young people successfully navigate through the increasingly unsatisfying modern world.

Elle nous fait bouger de plus en plus vite, ou surtout, elle nous fait croire que ce qui est bien c’est de bouger de plus et plus, et de plus en plus vite. En cherchant à aller de plus en plus vite, et à faire les choses de plus en rapidement, l’homme prend le risque de se perdre de vue lui-même. Goethe écrivait : « L’homme tel que nous le connaissons et dans la mesure où il utilise normalement le pouvoir de ses sens est l’instrument physique le plus précis qu’il y ait au monde. Le plus grand péril de la physique moderne est précisément d’avoir séparé l’homme de ses expériences en poursuivant la nature dans un domaine où celle-ci n’est plus perceptible que par nos instruments artificiels. »

Elle nous fait bouger de plus en plus vite, ou surtout, elle nous fait croire que ce qui est bien c’est de bouger de plus et plus, et de plus en plus vite. En cherchant à aller de plus en plus vite, et à faire les choses de plus en rapidement, l’homme prend le risque de se perdre de vue lui-même. Goethe écrivait : « L’homme tel que nous le connaissons et dans la mesure où il utilise normalement le pouvoir de ses sens est l’instrument physique le plus précis qu’il y ait au monde. Le plus grand péril de la physique moderne est précisément d’avoir séparé l’homme de ses expériences en poursuivant la nature dans un domaine où celle-ci n’est plus perceptible que par nos instruments artificiels. » Hartmut Rosa montre que la désynchronisation des évolutions socio-économiques et la dissolution de l’action politique font peser une grave menace sur la possibilité même du progrès social. Déjà Marx et Engels affirmaient ainsi que le capitalisme contient intrinsèquement une tendance à « dissiper tout ce qui est stable et stagne ». Dans Accélération, Hartmut Rosa prend toute la mesure de cette analyse pour construire une véritable « critique sociale du temps susceptible de penser ensemble les transformations du temps, les changements sociaux et le devenir de l’individu et de son rapport au monde ».

Hartmut Rosa montre que la désynchronisation des évolutions socio-économiques et la dissolution de l’action politique font peser une grave menace sur la possibilité même du progrès social. Déjà Marx et Engels affirmaient ainsi que le capitalisme contient intrinsèquement une tendance à « dissiper tout ce qui est stable et stagne ». Dans Accélération, Hartmut Rosa prend toute la mesure de cette analyse pour construire une véritable « critique sociale du temps susceptible de penser ensemble les transformations du temps, les changements sociaux et le devenir de l’individu et de son rapport au monde ».

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

À propos de Philippe Muray, Essais (Éditions

À propos de Philippe Muray, Essais (Éditions

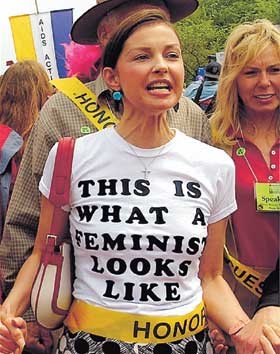

Insofern kann sich die Elite freuen: Mit Foucault, einem der größten und fähigsten Kritiker dessen, was heute abläuft, hat man den intellektuellen Hausmeister gefunden, der im neoliberalen Gedankengebäude für Ruhe, Ordnung und Sauberkeit sorgt. Somit ist geklärt, woher das Gedankenkonstrukt des Neoliberalismus kommt. Die Elite, auch wenn sie aus Menschen besteht, die unterschiedlicher Auffassungen sind, vereint sich in Verfolgung ihrer jeweiligen Ziele unter dem intellektuellen Schirm der Postmoderne und des Poststrukturalismus. Feministen, Globalisten, Unternehmen, Nationen, Gewerkschaften, ja sogar die Kirche und alle anderen erdenklichen Gruppierungen und Interessensvertreter: Sie mögen zwar alle unterschiedliche Ziele haben, aber sie bedienen sich alle derselben Techniken, die ihnen von Foucault in die Hände gegeben wurden. Damit ist auch zu verstehen, warum es sich hier um Einebnung und Gleichschaltung handelt: Unterschiedliche Ziele werden mit denselben Methoden verfolgt. Es führen viele Wege nach Rom. Auf die unterschiedlichen Wege machen sich viele, und alle kommen früher oder später in Rom an: im Neoliberalismus.

Insofern kann sich die Elite freuen: Mit Foucault, einem der größten und fähigsten Kritiker dessen, was heute abläuft, hat man den intellektuellen Hausmeister gefunden, der im neoliberalen Gedankengebäude für Ruhe, Ordnung und Sauberkeit sorgt. Somit ist geklärt, woher das Gedankenkonstrukt des Neoliberalismus kommt. Die Elite, auch wenn sie aus Menschen besteht, die unterschiedlicher Auffassungen sind, vereint sich in Verfolgung ihrer jeweiligen Ziele unter dem intellektuellen Schirm der Postmoderne und des Poststrukturalismus. Feministen, Globalisten, Unternehmen, Nationen, Gewerkschaften, ja sogar die Kirche und alle anderen erdenklichen Gruppierungen und Interessensvertreter: Sie mögen zwar alle unterschiedliche Ziele haben, aber sie bedienen sich alle derselben Techniken, die ihnen von Foucault in die Hände gegeben wurden. Damit ist auch zu verstehen, warum es sich hier um Einebnung und Gleichschaltung handelt: Unterschiedliche Ziele werden mit denselben Methoden verfolgt. Es führen viele Wege nach Rom. Auf die unterschiedlichen Wege machen sich viele, und alle kommen früher oder später in Rom an: im Neoliberalismus. Jean-Pierre Le Goff et l'ultraviolence

Jean-Pierre Le Goff et l'ultraviolence

Die heraufziehende Wirtschaftskrise, die auch eine Systemkrise werden wird, bringt Bewegung in die politische Szenerie. Leute im eigenen Bekanntenkreis, denen bis vor kurzem keine noch so gewichtig vorgetragene Warnung das Wässerchen ihrer Gewißheit vom ewigen Wohlstand und sicheren Fortbestand unserer Gesellschaftsform, vom „unumkehrbaren“ Prozeß der EU-Einigung trüben konnte, fangen auf einmal an, nachdenklich zu werden.

Die heraufziehende Wirtschaftskrise, die auch eine Systemkrise werden wird, bringt Bewegung in die politische Szenerie. Leute im eigenen Bekanntenkreis, denen bis vor kurzem keine noch so gewichtig vorgetragene Warnung das Wässerchen ihrer Gewißheit vom ewigen Wohlstand und sicheren Fortbestand unserer Gesellschaftsform, vom „unumkehrbaren“ Prozeß der EU-Einigung trüben konnte, fangen auf einmal an, nachdenklich zu werden. Die Vorstellung eines ewigen Lebens ist in den „klassischen Religionen“ bekanntlich mit der einer ewigen Glückseligkeit verknüpft. Wer möchte schon ewig leben, wenn er dann ewig zu leiden hätte? In der endlosen höllischen Peinigung – und nicht im ewigen Tod – sah man früher die eigentlich teuflische Strafe.

Die Vorstellung eines ewigen Lebens ist in den „klassischen Religionen“ bekanntlich mit der einer ewigen Glückseligkeit verknüpft. Wer möchte schon ewig leben, wenn er dann ewig zu leiden hätte? In der endlosen höllischen Peinigung – und nicht im ewigen Tod – sah man früher die eigentlich teuflische Strafe.

A una valutazione soggettiva, questo modo di vita assume largamente connotazioni negative. E’ la rappresentazione di quel cancro dell’anima che prende comunemente il nome di vittimismo, che si manifesta quando una sconfitta genera nella persona che l’ha subita un indole da cronico perdente. Tanti tra coloro che hanno impresso negli occhi l’orrore della modernità e che quotidianamente ne denunciano la corruzione e la decadenza l’hanno provato; hanno sentito sulle proprie spalle quel senso di prevaricazione che li ha spinti a tuffarsi nel vortice perché il vortice è tutto quello che riuscivano a scorgere, tanto il loro capo era piegato. Essi sposano quindi e fanno proprio tutto ciò che rappresenta il male, tutto ciò attraverso cui riescono a salvare quantomeno le apparenze della loro contrarietà, spesso in maniera sconclusionata, spesso auto-mortificandosi. Quante volte li abbiamo sentiti: “abbiamo perso la guerra”; oppure: “verremo repressi”; o ancora: “siamo pochi”. A costoro dedicò il suo pensiero Jean Thiriart: «Le persone prive di decisione si giustificano frequentemente della loro inerzia ragionando su un ‘risveglio’ sicuro dell’Esercito o su una vigilanza sicura della Chiesa. Essi dicono allora: ‘mai l’esercito permetterà questo’ o ancora ‘la Chiesa millenaria, nella sua saggezza e nella sua potenza, porrà un freno in tempo’. Si tratta ancora di pseudo giustificazioni di vigliaccheria e di pigrizia».

A una valutazione soggettiva, questo modo di vita assume largamente connotazioni negative. E’ la rappresentazione di quel cancro dell’anima che prende comunemente il nome di vittimismo, che si manifesta quando una sconfitta genera nella persona che l’ha subita un indole da cronico perdente. Tanti tra coloro che hanno impresso negli occhi l’orrore della modernità e che quotidianamente ne denunciano la corruzione e la decadenza l’hanno provato; hanno sentito sulle proprie spalle quel senso di prevaricazione che li ha spinti a tuffarsi nel vortice perché il vortice è tutto quello che riuscivano a scorgere, tanto il loro capo era piegato. Essi sposano quindi e fanno proprio tutto ciò che rappresenta il male, tutto ciò attraverso cui riescono a salvare quantomeno le apparenze della loro contrarietà, spesso in maniera sconclusionata, spesso auto-mortificandosi. Quante volte li abbiamo sentiti: “abbiamo perso la guerra”; oppure: “verremo repressi”; o ancora: “siamo pochi”. A costoro dedicò il suo pensiero Jean Thiriart: «Le persone prive di decisione si giustificano frequentemente della loro inerzia ragionando su un ‘risveglio’ sicuro dell’Esercito o su una vigilanza sicura della Chiesa. Essi dicono allora: ‘mai l’esercito permetterà questo’ o ancora ‘la Chiesa millenaria, nella sua saggezza e nella sua potenza, porrà un freno in tempo’. Si tratta ancora di pseudo giustificazioni di vigliaccheria e di pigrizia».

« Chaos mondial : la face noire de la mondialisation », par Alain Bauer et Xavier Raufer

« Chaos mondial : la face noire de la mondialisation », par Alain Bauer et Xavier Raufer Gender Mainstreaming – größtes Umerziehungsprogramm der Menschheit

Gender Mainstreaming – größtes Umerziehungsprogramm der Menschheit Der Horror war damit nicht zu Ende. In qualvollen Operationen ließ David die Brüste entfernen und bestand auf einem Kunstpenis, um wieder »ein ganzer Mann zu sein«. Doch das Experiment hatte ihn tief traumatisiert. Zusammen mit dem Autor John Colapinto dokumentierte er seinen tragischen Fall in dem aufsehenerregenden Buch Der Junge, der als Mädchen aufwuchs.

Der Horror war damit nicht zu Ende. In qualvollen Operationen ließ David die Brüste entfernen und bestand auf einem Kunstpenis, um wieder »ein ganzer Mann zu sein«. Doch das Experiment hatte ihn tief traumatisiert. Zusammen mit dem Autor John Colapinto dokumentierte er seinen tragischen Fall in dem aufsehenerregenden Buch Der Junge, der als Mädchen aufwuchs. Xenophobie als Gesundheitsprophylaxe

Xenophobie als Gesundheitsprophylaxe « Ce que nous vivons aujourd’hui me semble être plus qu’une fatigue de la consommation. C’est un véritable épuisement. En 2004, j’ai lu dans Le Monde les résultats d’une enquête sur la grande distribution française réalisée par un cabinet de marketing américain. Les hypermarchés étaient alors confrontés à un problème : on observait une baisse de la vente des produits de grande consommation alors qu’aucun facteur économique, comme un recul du pouvoir d’achat, n’était en mesure d’expliquer ce phénomène. La réponse proposée par cette enquête avançait l’idée qu’une nouvelle race de consommateurs était née : les “alter-consommateurs”, c’est-à-dire des consommateurs qui voudraient ne plus consommer. La même année, Télérama a publié les résultats d’une autre enquête sur les téléspectateurs français : 56% d’entre eux disaient ne pas aimer les programmes de la chaîne qu’ils regardaient le plus. Dans les deux cas, s’est exprimé un même désamour pour la consommation.

« Ce que nous vivons aujourd’hui me semble être plus qu’une fatigue de la consommation. C’est un véritable épuisement. En 2004, j’ai lu dans Le Monde les résultats d’une enquête sur la grande distribution française réalisée par un cabinet de marketing américain. Les hypermarchés étaient alors confrontés à un problème : on observait une baisse de la vente des produits de grande consommation alors qu’aucun facteur économique, comme un recul du pouvoir d’achat, n’était en mesure d’expliquer ce phénomène. La réponse proposée par cette enquête avançait l’idée qu’une nouvelle race de consommateurs était née : les “alter-consommateurs”, c’est-à-dire des consommateurs qui voudraient ne plus consommer. La même année, Télérama a publié les résultats d’une autre enquête sur les téléspectateurs français : 56% d’entre eux disaient ne pas aimer les programmes de la chaîne qu’ils regardaient le plus. Dans les deux cas, s’est exprimé un même désamour pour la consommation. Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1999

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1999 Ellen KOSITZA

Ellen KOSITZA

»Walkaways« – Nomadentum als neue Gesellschaftsstruktur in den USA

»Walkaways« – Nomadentum als neue Gesellschaftsstruktur in den USA

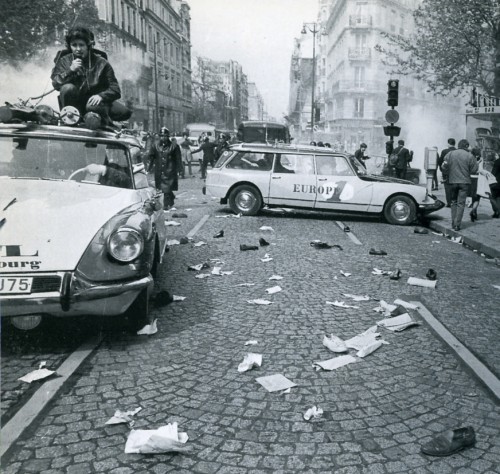

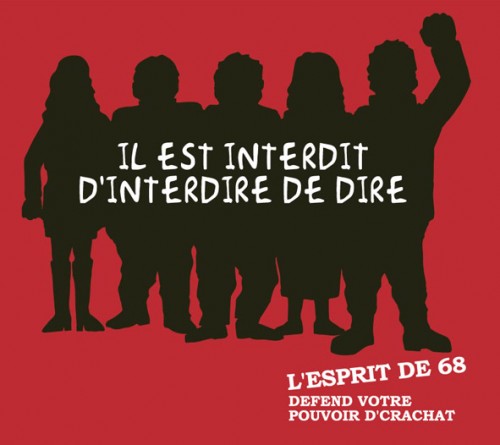

Cultuur, althans de officiële, geaccrediteerde versie, verwerd tot het hilarische trompetgeschal rond de tribune van de poco-dictatuur. De opdracht was en is om te verwarren, mist te spuiten. De ontzettende logorrhee en beeldenstroom die elke dag op ons afkomt, oversatureert ons bevattingsvermogen compleet, maakt ons murw en mentaal weerloos. Ook dat is een erfenis van het ’68-theater en de machtsgreep van deze ludieke generatie. Alles is scherts, ironie, spel, franje. Het politiek bedrijf, de cultuurindustrie en de media convergeren rond deze mateloze cultus van de schijn, het beeld en de perceptie, in een spektakelmaatschappij waarin je alleen bestaat als je op TV komt. En ook dat heeft hoger vernoemde Jacques Lacan achteraf scherp ontmaskerd,- ik citeer:

Cultuur, althans de officiële, geaccrediteerde versie, verwerd tot het hilarische trompetgeschal rond de tribune van de poco-dictatuur. De opdracht was en is om te verwarren, mist te spuiten. De ontzettende logorrhee en beeldenstroom die elke dag op ons afkomt, oversatureert ons bevattingsvermogen compleet, maakt ons murw en mentaal weerloos. Ook dat is een erfenis van het ’68-theater en de machtsgreep van deze ludieke generatie. Alles is scherts, ironie, spel, franje. Het politiek bedrijf, de cultuurindustrie en de media convergeren rond deze mateloze cultus van de schijn, het beeld en de perceptie, in een spektakelmaatschappij waarin je alleen bestaat als je op TV komt. En ook dat heeft hoger vernoemde Jacques Lacan achteraf scherp ontmaskerd,- ik citeer: