La crise ukrainienne n’a pas changé radicalement la donne internationale, mais elle a précipité des évolutions en cours. La propagande occidentale, qui n’a jamais été aussi forte, cache surtout la réalité du déclin occidental aux populations de l’Otan, mais n’a plus d’effet sur la réalité politique. Inexorablement, la Russie et la Chine, assistés des autres BRICS, occupent la place qui leur revient dans les relations internationales.

jeudi, 22 mai 2014

Acuerdo estratégico entre Rusia y China

Ex: http://www.elespiadigital.com

Rusia y China resistirán la injerencia extranjera en los asuntos internos de otros Estados y las sanciones unilaterales, dice un comunicado conjunto emitido este martes por los presidentes Vladímir Putin y Xi Jinping.

El mandatario ruso, Vladímir Putin, ha llegado en visita oficial a China, donde mantiene conversaciones con el presidente Xi Jinping y asistirá a la cumbre de la Conferencia sobre Interacción y Medidas de Construcción de Confianza en Asia. Asimismo, se reunirá con representantes de los círculos de negocios de China y Rusia.

"Las partes subrayan la necesidad de respetar el patrimonio histórico y cultural de los diferentes países, los sistemas políticos que han elegido, sus sistemas de valores y vías de desarrollo, resistir la injerencia extranjera en los asuntos internos de otros Estados, prescindir de las sanciones unilaterales y del apoyo dirigido a cambiar la estructura constitucional de otro Estado", puntualiza el documento acordado durante el encuentro de los mandatarios ruso y chino.

Al mismo tiempo, tanto Pekín como Moscú subrayan su preocupación por el perjuicio a la estabilidad y la seguridad internacional y el daño a las soberanías estatales que infligen las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación hoy en día. De esta manera, exhortan a la comunidad internacional a responder a estos desafíos y elaborar normas que regulen el comportamiento en el espacio informativo. Puntualizan, además, la necesidad de internacionalizar el sistema de gestión de Internet y seguir principios de transparencia y democracia.

El comunicado aborda además el tema del conflicto ucraniano e insta a todas las regiones y movimientos políticos del país a lanzar un diálogo y elaborar un concepto común de desarrollo constitucional.

Acuerdos militares

Moscú y Pekín se comprometen, además, a llevar a cabo la primera inspección conjunta de las fronteras comunes. Detallan que la medida estará destinada a combatir la delincuencia transfronteriza. Según ha destacado Putin, intensificar la colaboración militar "es un factor importante para la estabilidad y seguridad, tanto en la región como en todo el mundo". El presidente ruso ha acentuado que Moscú y Pekín tienen proyectos conjuntos de construcción de un avión de largo alcance y fuselaje ancho, y de un helicóptero civil pesado. El año que viene los dos países realizarán, además, maniobras militares conjuntas a gran escala con motivo del 70 aniversario de la victoria sobre el fascismo en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

Acuerdos económicos

En cuanto a la cooperación económica entre los dos países, el presidente ruso detalló que en 2013 los volúmenes del comercio bilateral llegaron a un total de unos 90.000 millones de dólares y pronosticó que para el año 2015 alcanzará los 100.000 millones de dólares. Las partes acordaron profundizar, sobre todo, los lazos en el sector energético y aumentar los suministros del gas, petróleo, electricidad y carbón rusos a China.

En el marco de las reuniones entre delegaciones comerciales de los dos países, la compañía rusa Novatek y la china CNPC han firmado ya un contrato para la entrega de 3 millones de toneladas anuales de gas natural licuado ruso. Rosneft, por su parte, comunica que ha estipulado con sus socios chinos los plazos exactos de construcción de una planta de refinado de petróleo en la ciudad de Tianjín. Está previsto que la planta empiece a operar para finales de 2019 y que la parte rusa se encargue de suministrarle hasta 9,1 millones de toneladas de crudo. Además, se está negociando un contrato histórico con Gazprom: según detalla el secretario de prensa del presidente ruso, Dimitri Peskov, las partes ya han avanzado con la negociación de los precios y actualmente siguen trabajando sobre los detalles del acuerdo.

"Tenemos una larga historia de buenas relaciones. Ambos países se desarrollan muy rápidamente. Creo que China está muy interesada en crear más oportunidades en el ámbito de los negocios utilizando los recursos únicos de los que dispone Rusia. Moscú también busca trabajar con China en muchos sectores económicos. Por eso creo que sus relaciones bilaterales tienen un gran futuro", comentó a RT el empresario chino Wei Song.

El Banco de China, uno de los cuatro mayores bancos estatales del país, y el VTB, el segundo grupo bancario más grande de Rusia, han firmado este martes un acuerdo que incluye realizar los pagos mutuos en sus divisas nacionales.

El presidente ruso, Vladímir Putin, se encuentra estos días de visita oficial a China, donde mantiene conversaciones con el presidente Xi Jinping y se reúne con representantes de los círculos de negocios de China y Rusia. El histórico acuerdo interbancario firmado en presencia del mandatario ruso y su homólogo chino estipula la cooperación en el sector de las inversiones, la esfera crediticia y las operaciones en los mercados de capital.

El Banco de China es el prestamista número dos en China en general y es uno de los 20 más grandes del mundo. El total de sus activos en 2011 llegó a unos 1,9 billones de dólares. Opera tanto en China como en otros 27 países del mundo. El 60,9% de las acciones del grupo VTB pertenecen al Estado ruso, el grupo funciona en 20 países y el total de sus activos llega a unos 253.300 millones de dólares.

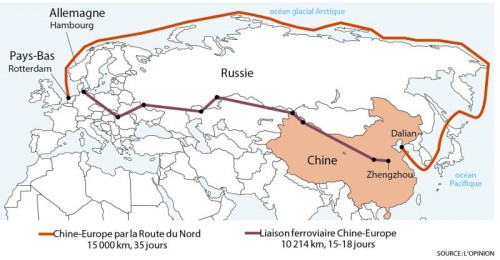

Según el comunicado estipulado en el marco del encuentro entre los dos presidentes, Moscú y Pekín aumentarán el volumen de pagos directos en divisas nacionales en todas las esferas y estimularán las inversiones mutuas, sobre todo en las infraestructuras de transporte, la exploración de recursos naturales y la construcción de viviendas de clase económica. El presidente Putin subrayó que especialistas de ambos países están considerando también la posibilidad de elaborar nuevos instrumentos financieros.

En 2013 los volúmenes del comercio bilateral entre Rusia y China llegaron a un total de 90.000 millones de dólares. Se pronostica que para el año 2015 alcanzará los 100.000 millones de dólares.

Rusia y China están a punto de cerrar un contrato de suministro de gas que supondrá 30.000 millones de dólares de inversiones y en un futuro podría cubrir el 40% de las necesidades del gigante asiático.

El propio presidente ruso, Vladímir Putin, en vísperas de su visita a China, que se celebrará los días 20 y 21 de mayo, dijo que el acuerdo sobre la exportación a China de gas natural ruso está en un "alto grado de preparación", recuerda la página web de la cadena estatal rusa Vesti.

El gigante estatal de gas ruso Gazprom lleva negociando esta transacción los últimos 10 años. El empuje más activo a estas negociaciones se dio en 2006, cuando Vladímir Putin anunció planes para organizar los suministros de gas a la segunda mayor economía del mundo.

¿Por qué las negociaciones han durado tanto?

A pesar de la gran cantidad de reuniones bilaterales, el cierre del 'acuerdo del siglo' había fracasado hasta ahora. El problema han sido los parámetros económicos, ya que China está peleando por muy fuertes rebajas de precio, mientras que Rusia quiere que el megaproyecto sea económicamente rentable.

El contrato que se negocia supone las exportaciones de gas a China durante 30 años, por lo que las partes deberían tener en cuenta todos los riesgos a largo plazo ya que reconsiderar los parámetros del contrato ya firmado sería muy difícil.

Por otra parte, los suministros de gas ruso no eran muy urgentes para China, país que hasta hace poco se conformaba con el gas que recibía desde Turkmenistán, vía Uzbekistán y Kazajistán. Sin embargo, el consumo de gas en China ha crecido tanto que el gigante industrial ya empieza a temer la insuficiencia de suministros.

Precio del gas ruso para China

El precio del gas para China ha sido un punto importante de la pelea durante varios años. Pekín ha insistido en que, dado el gran volumen y la duración del contrato, el precio mínimo no deberá ser superior al que Rusia tiene establecido para Europa.

Tradicionalmente, el precio del gas centroasiático ha sido más barato para China que el precio del gas ruso para Europa, mientras que para Rusia es importante que el precio del gas se coloque a un nivel de 360-400 dólares por 1.000 metros cúbicos ya que cualquier precio que sea inferior colocaría estos suministros por debajo del límite de rentabilidad.

Por ahora los especialistas hablan de precios en torno a los 350-380 dólares, es decir, se trata de un nivel de precios equivalente al europeo.

Los ingresos y volúmenes de suministros previstos

En marzo de 2013 las partes firmaron un memorando de entendimiento en el cual figuraba la enorme cantidad de 38.000 millones de metros cúbicos por año a partir de 2018, con un posterior aumento hasta 60.000 millones de metros cúbicos.

Considerando el precio estimado del gas y el plazo del contrato, Rusia podría ingresar 400.000 millones de dólares.

El costo de la construcción del gasoducto bautizado Sila Sibiri (Fuerza de Siberia) se estima en 30.000 millones de dólares.

La importancia del gas ruso para China

China necesita volúmenes adicionales de gas debido al aumento de la demanda interna. La demanda de gas en la segunda economía del mundo está creciendo rápidamente. En el primer trimestre de este año las importaciones de gas a China crecieron un 20% respecto al mismo periodo del ejercicio anterior.

Expertos chinos calculan que en 2020 el consumo de gas en el país será en torno a 300.000 millones de metros cúbicos, mientras que en 2030 esta cifra podría subir a 600.000 millones.

En otras palabras, el contrato con Rusia es imprescindible para una perspectiva a largo plazo.

La importancia del proyecto para Rusia

Las exportaciones de gas ruso a China son de suma importancia para Rusia en términos de diversificación de los suministros, sobre todo ahora de cara a posibles sanciones por parte de la Unión Europea, hoy en día el principal consumidor de gas ruso.

Dada la competencia de Turkmenistán, así como la de proveedores de gas natural licuado, Gazprom debe estar presente en el mercado chino.

Se calcula que mientras el contrato esté en vigor, Rusia reciba unos 400.000 millones de dólares de ingresos. Además, el fortalecimiento de las relaciones con China supondrá el aumento de las inversiones mutuas.

Moscú: Rusia y China realizarán ocho proyectos estratégicos

Moscú y Pekín crearán un cuerpo especial para la supervisión de la ejecución de ocho proyectos estratégicos, anunció el viceprimer ministro ruso Dmitri Rogozin.

"En Pekín, junto con el viceprimer ministro chino Wang Yang, firmamos un protocolo sobre el establecimiento del grupo de supervisión de los ocho proyectos estratégicos", publicó Rogozin en a través de su cuenta en Twitter.

Rogozin agregó que estos proyectos están relacionados con el espacio y con la creación de una infraestructura fronteriza mutua. "Entre ellos: la cooperación en el espacio y en el mercado de la navegación espacial, en la ingeniería de aviones y helicópteros, y la construcción de una infraestructura fronteriza y de transporte común", escribió el viceprimer ministro en Facebook.

"Ampliar nuestros lazos con China, nuestro amigo de confianza, es definitivamente una prioridad de la política exterior rusa. Actualmente la cooperación bilateral está entrando en una nueva etapa de amplia asociación y cooperación estratégica", declaró el presidente ruso, Vladímir Putin, en una entrevista a los principales medios del país, en vísperas de su visita a China.

Merkel confirma el interés de Europa por mantener buenas relaciones con Rusia

La canciller alemana, Angela Merkel, entrevistada por el periódico Leipziger Volkszeitung, dijo que Rusia es un socio cercano de Alemania y que las buenas relaciones con Moscú responden a los intereses de Europa.

“Para nosotros, los alemanes, Rusia es un socio cercano. Existen numerosos contactos fiables entre los alemanes y los rusos, así como entre la UE y Rusia. Estamos interesados en mantener buenas relaciones con Rusia”, indicó.

La canciller confesó que debate regularmente con el presidente ruso Vladímir Putin la crisis en Ucrania y no descarta una reunión personal.

Durante la última conversación telefónica, Mérkel y Putin analizaron este tema con vistas a las elecciones presidenciales que Ucrania planea celebrar el 25 de mayo.

“A los comicios ucranianos asistirán observadores de la OSCE. Si la OSCE reconoce que su celebración se efectuó según normas universales, espero que Rusia, como miembro de esta organización, también reconozca sus resultados”, dijo la canciller.

La Oficina para las Instituciones Democráticas y los Derechos Humanos de la OSCE abrió el 20 de marzo su misión en Kiev para monitorear las presidenciales en Ucrania.

La misión está integrada por 18 expertos que permanecerán en Kiev y 100 observadores con mandato a largo plazo que trabajarán en todo el territorio del país. En el día de las elecciones, otros 900 observadores con mandato a corto plazo seguirán su desarrollo.

Merkel señaló que durante los últimos años Alemania se planteó el objetivo de “cohesionar a Rusia y Europa”. Al recordar que el presidente ruso promovió la idea de crear una zona de libre comercio desde Lisboa hasta Vladivostok (Lejano Oriente ruso), dijo que existen buenos argumentos a favor de la realización de este plan.

En Rusia y crece la satisfacción con la vida

Los rusos cada vez están más satisfechos con la vida y no tienen ganas de protestar, según se desprende de las encuestas conjunta del Centro Levada y el Centro VTsIOM.

De acuerdo al sondeo del VTsIOM, en abril el 46% de los rusos estaban contentos con su vida, frente al 43% en marzo y el 40% en febrero.

La mayoría de los satisfechos con la vida tienen entre 18 y 24 años de edad. También están contentos con su nivel de vida los ciudadanos con altos ingresos.

Al mismo tiempo, el 80% de los rusos, según Levada, no participarían en actos de protesta si estos llegasen a celebrarse en su localidad. Además, el 95% de los encuestados manifestaron no haber participado en huelgas durante un año.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Eurasisme, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : gopolitique, politique internationale, chine, russie, europe, asie, affaires européennes, affaires asiatiques, eurasie, eurasisme, gaz, gazoducs, hydrocarbures, brics, énergie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 21 mai 2014

Rusland dumpt 20% staatsobligaties VS

Iedereen begrijpt dat het diep in de schulden gestoken België nooit zelf voor zo'n enorm bedrag aan Amerikaanse staatsobligaties kan hebben opgekocht. De ware identiteit van de koper is echter onbekend.

Vanmiddag werd definitief bevestigd dat Rusland al vóór maart 2014 voor het recordbedrag van $ 26 miljard aan Amerikaanse staatsobligaties heeft gedumpt, ongeveer 20% van het totaal. Rusland houdt nu voor net iets meer aan $ 100 miljard aan Amerikaanse schuldpapieren over, het laagste niveau sinds de Lehman-crisis in 2008. Schokkender is het feit dat het kleine België sinds december vorig jaar voor maar liefst $ 181 miljard Amerikaanse schatkistpapieren heeft gekocht, waarvan $ 40 miljard in maart.

Onze zuiderburen hebben nu bijna net zoveel Amerikaanse schulden gekocht als hun totale jaarlijkse BNP, en zijn daarmee na China en Japan wereldwijd de grootste houder van Amerikaanse staatsobligaties.

Omdat het onmogelijk is dat het diep in de schulden gestoken België dit op eigen houtje heeft kunnen doen, moet er dus een onbekende koper zijn die België gebruikt als ‘proxy’ aankoopkanaal. Vanzelfsprekend kan dat alleen met volledige medewerking van de Belgische regering gebeuren.

In augustus 2013 bezat België nog voor ‘slechts’ $ 167 miljard Amerikaanse staatsschuldpapieren. In november schoot dit bedrag ineens omhoog naar $ 257 miljard, en de teller stond in maart van dit jaar op $ 381 miljard. Ter vergelijk: het Belgische BBP schommelt zo rond de $ 400 miljard.

Japan, de nummer 2 op de lijst, heeft juist voor $ 10 miljard verkocht, terwijl China als grootste houder zijn aandeel min of meer stabiel houdt.

De massa aankopen via België tonen eens te meer aan dat het hele Westerse valuta- en staatsschuldensysteem met kunstmatige ingrepen overeind wordt gehouden, en de staatsobligatiemarkt zwaar gemanipuleerd wordt. Onafhankelijke analisten zien hierin een duidelijk signaal dat de gevreesde totale crash steeds dichterbij komt.

Xander

(1) Zero Hedge

(2) Zero Hedge

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Belgicana, Economie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : dollar, politique internationale, russie, belgique, états-unis, devises, finances internationales |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 19 mai 2014

Rusland en China nemen actieve stappen om dollar te laten vallen

Rusland en China nemen actieve stappen om dollar te laten vallen

Ex: http://xandernieuws.punt.nl

De val van de dollar zal dramatische gevolgen hebben voor de Amerikaanse economie en samenleving, en ook voor alle Europese landen en bedrijven die voor een groot deel afhankelijk zijn van de handel met de VS (zoals Nederland).

De lang voorspelde en gevreesde val van de Amerikaanse dollar lijkt weer een stap dichterbij te komen nu het Russische ministerie van Financiën het groene licht heeft gegeven aan een plan om het aantal in dollar afgehandelde transacties radicaal te verminderen. Ook China en Iran zouden er wel oren naar hebben om de dollar bij hun onderlinge handel te laten vallen. Aangezien de Russische president Putin op 20 mei naar Beijing reist om gas- en oliecontracten af te sluiten, is de kans groot dat deze leveringen niet langer in dollars, maar in roebels en yuans zullen worden afgerekend.

Volgens Voice of Russia kwam de regering op 24 april speciaal bijeen om te overleggen hoe Rusland van de dollar af kan komen. De grootste experts uit de energiesector, banken en overheidssector overlegden wat de beste reactie kan zijn op de Amerikaanse sancties, die werden ingesteld vanwege de crisis in Oekraïne.

Igor Shuvalow, vicepremier van de Russische Federatie, was de voorzitter tijdens deze ‘de-dollarisering vergadering’, wat aangeeft dat het Kremlin meer dan alleen maar bluft. Vice minister van Financiën Alexey Moiseev gaf leiding aan een tweede vergadering. Na afloop verklaarde hij dat geen van de experts en afgevaardigden problemen voorziet als Rusland het aantal internationale betalingen in roebels gaat opvoeren.

Tevens maakte Moiseev melding van een ‘valuta-switch uitvoerend bevel’, waarmee de regering Russische bedrijven kan dwingen om een bepaald percentage van hun handel in roebels af te rekenen. Gevraagd of dit percentage 100% zou kunnen worden, antwoordde hij: ‘Dat is een extreme optie, en het is lastig voor me om nu te zeggen of de regering deze macht zal gebruiken.’

Als alleen Rusland zo’n drastische stap zou nemen, zou er voor de VS nog niet veel aan de hand zijn. Het zal echter niemand verbazen dat China en Iran serieus overwegen om de Russen te volgen. De omvangrijke olie- en gascontracten die president Putin op 20 mei in Beijing zal afsluiten, zullen mogelijk al volledig in roebels en yuans worden afgerekend.

Zo begint steeds dichterbij te komen waar critici al maanden voor waarschuwen, namelijk dat het anti-Russische beleid van het Westen als een boemerang tegen onze eigen hoofden zal terugkeren. De gascontracten die Rusland met China gaat afsluiten zijn slechts het begin. Als steeds meer landen gaan volgen, dan is het een kwestie van tijd voordat de dollar valt, waardoor de complete Amerikaanse economie crasht. Ook voor de Europese economie zal dit verstrekkende gevolgen hebben.

Xander

(1) Zero Hedge (/ Voice of Russia)

00:07 Publié dans Actualité, Economie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, économie, politique internationale, dollar, finances, russie, chine, brics, états-unis |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

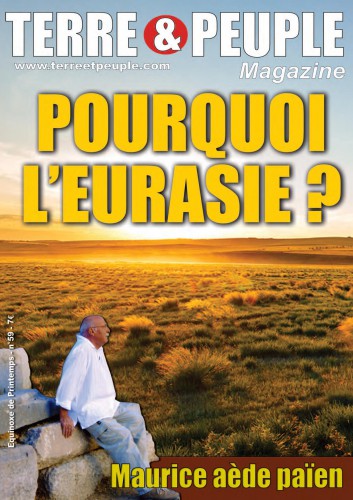

Terre & Peuple: pourquoi l'Eurasie?

Le numéro 59 de TERRE & PEUPLE Magazine est centré autour du thème mobilisateur Pourquoi l'Eurasie ?

Le numéro 59 de TERRE & PEUPLE Magazine est centré autour du thème mobilisateur Pourquoi l'Eurasie ?

Communication de "Terre & Peuple-Wallonie"

Dans éditorial sur 'le communautarisme identitaire', Pierre Vial évoquant les communautarismes qui déchirent l'Afrique, constate l'échec total de la 'nation arc-en-ciel, promise par Mandela à l'Afrique-du-Sud. Entre temps, le reste de l'Afrique s'explique à la kalachnikov.

Ouvrant le dossier sur l'Eurasie, Pierre Vial souligne les incohérences de la pensée d'Alexandre Douguine, porte-voix de l'eurasisme que relaye Alain de Benoist. Poutine en a fait la promotion pour étayer la dimension continentale de son ambition patriotique. Comme ce projet tend à légitimer le métissage, nous adoptons de préférence le mythe mobilisateur du réveil des peuples blancs de l'Eurosibérie. Une raison de plus pour une présentation objective du concept d'Eurasie.

Robert Dragan fait le relevé des peuplements européens en Asie et mesure l'entité géographique, dominée par des Européens, qui déborde sur l'Asie. Les archéologues révèlent la présence, dès -3500AC, dans l'Altaï mongol d'une culture identique à celle, plus récente, des Kourganes, pratiquée par des dolichocéphales de race blanche. Plus près de nous (-1500AC), les Tokhariens du Tarim (ouest de la Chine) étaient des Indo-Européens blonds, qui parlaient une langue de type scandinave et tissaient des tartans écossais. Strabon et Ptolémée les citent. Au début de notre ère, les Scythes qui occupaient l'ouest sibérien avaient détaché vers le Caucase la branche des Alains, qui y subsistent de nos jours sous le nom d'Ossètes. A l'ère chrétienne, le mouvement va s'inverser avec les migrations des Huns, Alains, Wisigoths, Petchénègues et Tatars. Jusqu'à ce que, au XIIe siècle, Gengis Kahn et ses descendants dominent la Russie. Jusqu'à ce que, au XVIe siècle, les tsars, à la suite d'Ivan le Terrible, se dotent d'une armée disciplinée. La reconquête reposera sur l'institution de la caste guerrière des cosaques, hommes libres, notamment d'impôt. Cavaliers voltigeant aux frontières, ils renouent avec une tradition ancestrale. Après qu'ils se soient emparés de Kazan, capitale des Tatars, des pionniers ont pu s'enfoncer au delà de la Volga dans les profondeurs sibériennes. Chercheurs d'or mou (les fourrures), ils y ont établi des forts et des comptoirs commerciaux. Réfractaires à la réforme liturgique et persécutés, les Vieux Croyants s'y sont enfuis pour fonder des colonies. Les Russes ne sont alors en Sibérie que des minorités infimes ( 200.000 au XVIIe siècle), sauf dans le Kazakhstan, mais dominantes. Le Transsibérien (1888-1904) va provoquer une expansion explosive : les comptoirs deviennent des métropoles. La Sibérie compte aujourd'hui quarante millions d'habitants, dont 94% de Russes, 1% d'Allemands et 0,02% de Juifs. A l'égard des îlots d'asiates, Poutine se comporte comme l'a fait la Grande Catherine II, dans le respect de leur identité culturelle et religieuse. La seule inquiétude vient de l'immigration incontrôlée des Chinois, qui s'insinuent dans le commerce de détail et l'artisanat. Le projet d'une Eurosibérie, enthousiasmant pour un Européen de l'Ouest, éveille la méfiance en Russie, qui n'a pas oublié les envahisseurs polonais, suédois, teutoniques, autrichiens, prussien et français. Comment se confondre avec un Occident qui l'a constamment trahi ?

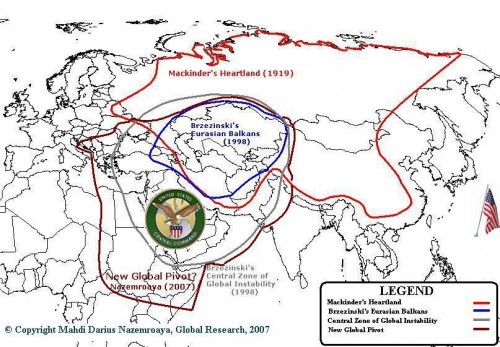

Alain Cagnat s'autorise de Vladimir Volkoff pour remarquer qu'il existe sur 180° de la circonférence terrestre une terre peuplée majoritairement de Blancs marqués par le christianisme. L'Europe n'est qu'une minuscule péninsule à l'ouest de l'Eurasie. Mise à part l'île britannique, hantée par son obsession séculaire de tenir les mers et d'entretenir la division du continent, depuis que Mackinder l'a convaincue que « Qui tient le Heartland tient le monde ». La puissance anglo-saxonne vise à contrôler la mer et le commerce et par là la richesse du monde. Elle a gagné les deux guerres mondiales, qui ont consacré la castration des puissances européennes et la partition du continent, en un Occident 'libre' et une 'tyrannie'. L'implosion inespérée de celle-ci, en 1990, a évacué la hantise d'un holocauste nucléaire. L'Occident s'identifie alors à un monde américanisé et globalisé, tueur des peuples, à remplacer désormais par un 'village-monde' d'heureux consommateurs crétinisés. La Russie et la Chine ne se laissent pas séduire, pas plus que l'Iran ni le monde arabo-sunnite. Les Etats-Unis organisent alors leur 'Containment'. Par les révolutions de couleur, orchestrées par les ONG de la démocratie et des Droits de l'Homme, et par l'extension de l'Union européenne et de l'Otan. Par des opérations de déstabilisation de Poutine et par un bouclier antimissile, censé protéger contre une agression de l'Iran ! La Chine fait l'objet d'un encerclement maritime. L'Union européenne, géant économique, mais nain politique et larve militaire, n'est plus qu'une banlieue des Etats-Unis. Elle n'en demeure pas moins le seul cadre possible pour notre idée d'empire. Poutine n'a-t-il pas dit : « La Grande Europe de l'Atlantique à l'Oural, et de fait jusqu'au Pacifique, est une chance pour tous les peuples du continent. » Moscou se voit comme la Troisième Rome et la gardienne de l'orthodoxie chrétienne. Mais les Russes sont d'opinions partagées. Il y a les occidentalistes, prêts à moderniser la Russie millénaire. Il y a les slavophiles, férus du mysticisme de l'âme slave, qui avec Soljenitsine méprisent volontiers le pourrissoir occidental. Il y a les eurasistes, qui avec Douguine jugent que l'Europe n'a pas à s'intégrer à l'Eurasie. L'empire eurasiste est multiethnique. Il place les autres peuples au même rang que les Russes et juge les autres religions égales à l'orthodoxie. En conclusion : l'Europe doit revoir sa stratégie et renverser ses alliances. Elle dépend des Russes pour un quart de son pétrole et un tiers de son gaz et 80% des investissements étrangers en Russie sont européens. En dressant un nouveau Rideau de Fer, l'Union européenne fracasse sur l'autel de l'utopie mondialiste américaine le rêve de l'unité européenne. Celle-ci devrait, de préférence, ne pas se réaliser dans l'orientation eurasiste grand-russe d'un mélange des races et des ethnies européennes et asiatiques, mais dans celle d'un axe Paris-Berlin-Moscou du continent uni sous l'hégémonie pan-européenne.

Jean-Patrick Arteault attend des élections européennes que l'Union européenne voie punies ses trahisons et son partenariat avec une finance apatride qui s'auto-désigne comme l'Occident. Le but des vrais Européens est d'acquérir la puissance d'assurer à leurs peuples leur développement culturel et social. Il est acquis qu'ils ont perdu la guerre et que leur 'Père-Fondateur' Jean Monet s'est révélé être l'homme des Américains, familier des mondialistes anglo-américains. L'UE s'affaire à la mise en place du Grand Marché transatlantique, base du futur Etat occidental qui confirmera une domination anglo-saxonne irréversible. C'est la réalisation de grand projet de Cecil Rhodes et de Milner. Ce GMT alignera les normes européennes sur les normes américaines, en toutes matières, tant de sécurité que sanitaire, environnementale, sociale, financière. 2014 doit être le tournant de la nouvelle Guerre Froide, nourrie de deux visions géopolitiques antagonistes : le projet mondialiste de l'Occident et le projet d'Union eurasiatique de Poutine, lequel souhaitait y inclure l'Ukraine. L'eurasisme russe est divisé entre Occidentalistes, partisans du modernisme, et Slavophiles, réfractaires aux Lumières occidentales et qui voient la vraie Russie dans la synthèse de la slavité médiévale et d'une Eglise orthodoxe qui a médiatisé l'apport des Grecs. Pour les slavophiles, c'est le lieu d'enracinement qui est finalement décisif, le Boden pesant alors plus que le Blut. Poutine a entre temps mis sur pied l'Organisation du traité de sécurité collective, pour la défense mutuelle de la Russie, de la Biélorussie, de l'Arménie, du Kazakhstan, du Kirghizistan, de l'Ouzbékistan et du Tadjikistan. En regard de l'idée eurasiste, le concept d'Eurosibérie a été forgé en 2006 par Guillaume Faye et Pierre Vial en réponse à ce que Carl Schmidt appelle un « cas d'urgence », l'affrontement des peuples blancs à tous les autres. C'est le mythe mobilisateur d'un empire confédéral, ethniquement homogène et autarcique, avec la Russie au centre.

Roberto Fiorini dénonce la trahison de l'Union européenne, qui s'attaque aux revenus du travail salarié, en violation de son objectif originel, qui est, aux termes du Traité de Rome, l'amélioration des conditions de vie des travailleurs, en évitant notamment des zones pauvres à chômage élevé et à salaires bas, qui incitent à délocaliser les activités, à mettre les salariés en compétition. Le ré-équilibrage des régions est un échec et l'Acte Unique de 1986 a ouvert la libre circulation des personnes et des capitaux, premier pas vers la mondialisation. La compétition des salaires introduit l'abandon de leur indexation. Dès 1994, l'OCDE prônait la flexibilité des salaires, la réduction de la sécurité de l'emploi et la réforme de l'indemnisation du chômage. L'appauvrissement et la précarisation des ménages amorce une spirale infernale. La BCE, gardienne du temple, veille par la modération salariale que l'inflation reste proche de zéro. Les syndicats, qui ont accompagné le grand projet de mondialisation, sont rendus quasiment inefficaces et réduits à un simulacre d'opposition. Au profit de multinationales, qui pillent sans contribuer.

Alexandre Delacour révèle que le nouvel OGM TC1507 est légalement commercialisé malgré une large opposition d'Etats membres (67%) et d'eurodéputés (61%), qui légalement devaient représenter 62% de la population de l'Union et n'en représentaient que 52,64% ! Paradoxalement, les petits pays sont moins dociles aux lobbies semenciers, qui mettent le monde agricole en servage, la santé publique en péril (la fertilité des spermatozoïdes des Européens en chute vertigineuse :-30%).

Claude Valsardieu poursuit son relevé des peuplements blancs hors d'Europe. Sur le flanc sud des forêts et toundras sibériennes, les Scytes et leur prédécesseurs les civilisations successives des Kourganes (IVe millénaire AC) de l'Ukraine à l'Altaï. La civilisation des oasis, dans le bassin du Tarim, et la civilisation de l'Indus (du IIe au IVe millénaire AC). Ensuite, la désertification facilita l'installation d'Aryens et la nomadisation de hordes conquérantes vers l'ouest : Huns blancs d'Attila, Turcs blancs seldjoukides, Mongols de la Horde d'Or. En Afrique septentrionale, à partir de 3000 AC, la seconde vague mégalithique pénètre en force en Méditerranée. Qu'étaient les hommes du Sahara humide néolithique ? A la période des chasseurs ont succédé la période des pasteurs bovidiens et celle du cheval avec l'arrivée des Peuples de la Mer, dont l'écrasement par Ramsès III est célébré sur les bas-reliefs de Medinet Abou.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Nouvelle Droite, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : nouvelle droite, terre et peuple, eurasie, eurasisme, pierre vial, revue, europe, affaires européennes, russie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Interview de Pascal Marchand, spécialiste de la géopolitique de l'Europe et de la Russie

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Entretiens, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, géopolitique, ukraine, russie, europe, affaires européennes, entretien |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 18 mai 2014

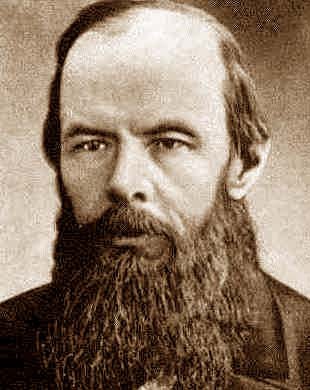

El sueño de Dostoyevsky

por Antonio García Trevijano y Roberto Centeno

Ex: http://paginatransversal.wordpress.com

Como es sabido, Tocqueville llegó a predecir que el porvenir del mundo estaría bajo el dominio político de dos grandes potencias, Estados Unidos y Rusia. Desde luego había que ser muy sagaz en asuntos internacionales y un profundo conocedor de las tendencias históricas para profetizar casi siglo y medio antes de que sucediera el condominio del mundo por las dos grandes potencias de la posguerra mundial. Más fácil resulta hoy predecir que el porvenir de Rusia está en Europa y el de Europa en Rusia. Esto quiere decir que, a corto plazo, hablando en términos históricos, el único camino de futuro que se presenta a la encrucijada rusa y a la ruina de la mayor parte de países europeos para mayor gloria de Alemania está en la integración en una magna empresa político-económica europea, que abarque desde Lisboa a Vladivostok.

Como es sabido, Tocqueville llegó a predecir que el porvenir del mundo estaría bajo el dominio político de dos grandes potencias, Estados Unidos y Rusia. Desde luego había que ser muy sagaz en asuntos internacionales y un profundo conocedor de las tendencias históricas para profetizar casi siglo y medio antes de que sucediera el condominio del mundo por las dos grandes potencias de la posguerra mundial. Más fácil resulta hoy predecir que el porvenir de Rusia está en Europa y el de Europa en Rusia. Esto quiere decir que, a corto plazo, hablando en términos históricos, el único camino de futuro que se presenta a la encrucijada rusa y a la ruina de la mayor parte de países europeos para mayor gloria de Alemania está en la integración en una magna empresa político-económica europea, que abarque desde Lisboa a Vladivostok.

No se trata ya de imaginar, como Kissinger, que la integración de Rusia en unos Estados Unidos de Europa alcanzaría desde el primer momento la supremacía mundial en todos los terrenos. Pero basta mirar hacia un pasado no demasiado lejano para darse cuenta de que la veleta de la historia, empujada por los templados vientos del progreso, apunta inequívocamente hacia la integración de Rusia en Europa. A propósito de esta idea tan tranquilizadora para el espíritu colectivo como tan necesaria para la paz mundial, es sumamente sugestivo recordar el sueño que tuvo el gran Fyodor Dostoyevsky cuando, medio adormilado ante un hermoso cuadro de Claude Lorraine en el museo de Dresde que refleja “una puesta de sol imposible de expresar en palabras”, concibió la grandiosa misión eslava de Rusia, salvando a Europa de su decadencia.

“El francés no era más que francés, el alemán, alemán; jamás el francés ha hecho tanto daño a Francia, ni el alemán a Alemania, sólo yo en tanto que ruso era entonces, en Europa, el único europeo. No hablo de mí, hablo de todo el pensamiento ruso. Se ha creado entre nosotros, en el curso de los siglos, un tipo superior de civilización desconocido en otras partes que no se encuentra en todo el universo: el sufrir por el mundo. Ese es el tipo ruso de la parte más cultivada del pueblo ruso, pero que contiene en sí mismo el porvenir de Rusia. Tal vez no seamos más de un millar de individuos, tal vez más o tal vez menos. Poco para tantos millones, pero según yo no es poco”. ¿Puede acaso alguien presumir hoy de ser tan europeo como Dostoyevsky o de esas élites rusas que describe?

Alejados en el espacio, cercanos en el espíritu

El sueño de Dostoyevsky no sólo significó un llamamiento a las élites rusas, que hasta ahora ha sido desoído, sino sobre todo una admonición a las minorías culturales europeas que se permitían aires de superioridad sobre el alma eslava. Sin embargo, aquella angustiosa apelación a las elites rusas ha tenido eco especial en España. Si eran pocos los individuos rusos conscientes de este maravilloso destino de su país, menos aún había en los países europeos. Siendo así que los dos pueblos europeos más alejados espacialmente de Rusia, como son España y Portugal, estaban mejor preparados que todo el resto de Europa para comprender el insólito mensaje de Dostoyevsky.

Los dos pueblos de la Península Ibérica tienen algo común con el pueblo ruso. Algo muy profundo que marcó su destino cristiano y su alejamiento de las civilizaciones asiáticas y africanas. Tanto España como Portugal o, hablando con más precisión, los pueblos cristianos de la Península, se negaron a someterse a la esclavitud del islam y lucharon sin descanso para reconquistar de los árabes y de las sucesivas oleadas de pueblos norteafricanos el territorio perdido y así no abandonar el cristianismo. Unamuno es el único pensador español que, advertido de esta singularidad, entró en la contradicción de considerar, por un lado, que África comenzaba en los Pirineos y, por otro, reconocer el paralelismo entre la singularidad española y la rusa: la religión cristiana orientó a España y a Rusia en una misma dirección histórica, adquiriendo su personalidad cultural en una larga lucha contra una cultura africana y otra asiática, respectivamente.

El enemigo declarado de España, amigo de reyes africanos caníbales a cambio de sus diamantes, protector de los asesinos de ETA y máximo exponente del desprecio al alma eslava, el ruin y miserable Valéry Giscard d´Estaing, excluiría expresamente de la Constitución Europea su verdadero origen: sus raíces cristianas, sin las cuales Europa sería ininteligible. Que este canalla, prepotente y corrupto haya redactado la Constitución Europea, imponiendo la multiplicidad del particularismo sobre la unicidad de Europa, a la vez que excluía deliberadamente el espíritu unificador europeo del cristianismo, no tiene perdón de Dios, y creó las bases políticas de la actual carrera centrífuga de la Unión Europea, donde cada uno va a lo suyo salvo España, que va a lo alemán.

Historias paralelas

España y Rusia tienen muchas cosas en común, cosas por las que Europa debería haberse sentido agradecida, pero nada más lejos. Han sido los grandes escudos de Europa, la primera frente al islam y la segunda frente a los mongoles. Durante 500 años –hasta las Navas de Tolosa–, España tuvo que combatir sin descanso a un enemigo fanático, implacable y cruel, cuyo objetivo era la conquista de Europa. En 1212, el objetivo declarado de Muhammad An-Nasir al mando de las fanáticas hordas almohades era llevar sus caballos a abrevar a las fuentes de Roma y crucificar al Papa, algo que sin duda habría hecho de no haber sido literalmente aniquilado en las Navas de Tolosa, una de las batallas más decisivas de la historia.

El 16 de julio de 1212 tres reyes de España, Alfonso VIII de Castilla, Pedro II de Aragón y Sancho VII de Navarra, cabalgaron hacia la victoria o hacia la muerte, cuya vanguardia estaba al mando de Diego López de Haro, señor de Vizcaya. Fue una de las batallas más sangrientas conocidas jamás. Los reyes cristianos no se detuvieron un segundo a repartirse el inmenso botín, sino que persiguieron al enemigo hasta su total exterminio. De los 300.000 guerreros de An-Nasir, apenas sobrevivieron algunos miles. Desde entonces las invasiones árabes y norteafricanas cesarían para siempre. El Reino de Granada, que quedaría aislado y como vasallo de Castilla más de dos siglos, no recibiría ayuda significativa alguna cuando fue finalmente reconquistado por los Reyes Católicos.

En el otro lado de Europa, los mongoles invadieron Rusia en 1223 y derrotaron a los príncipes rusos en la batalla del río Kalka, una batalla que permanece desde entonces en la memoria del pueblo ruso como para nosotros la fatídica del río Guadalete. En los años siguientes los mongoles aniquilaron a más del 90% de la población, llamando a los territorios conquistados la ‘Horda de Oro’. Kiev jamás se recuperaría de esta devastación, pero en los siglos siguientes Moscú tomaría el relevo, luchando sin descanso contra los mongoles, que son derrotados definitivamente en la gran batalla del río Ugra en 1480, las ‘Navas de Tolosa rusas’, y rechazados después hasta más allá de los Urales. Casi simultáneamente, entre 1480 y 1492, los invasores musulmanes y mongoles habían sido expulsados definitivamente. Gracias a Rusia y España, que construyeron a partir de entonces sendos imperios, Europa se había salvado,pero ni agradecido ni pagado.

Son lamentables los acontecimientos de Ucrania, donde la rapiña una vez más de los saqueadores alemanes y franceses, en connivencia con los corruptos gobernantes ucranianos, han llevado a un enfrentamiento grotesco entre la Unión Europea y la Federación Rusa, ya que es del interés de los pueblos de Europa y de la Federación Rusa una gran unión económica y política desde Lisboa a Vladivostok, excluyendo al Reino Unido. Del interés de los pueblos, aunque no lo sea de muchos líderes y menos aún de los expoliadores habituales, porque como vaticinaba Henry Kissinger –una de las mentes más preclaras del siglo XX–, una Unión Europea más Rusia desbancaría del primer plano económico y político a EEUU y Reino Unido.

Rusia más UE, primera potencia mundial

No hace falta tener grandes conocimientos de economía para darse cuenta de lo que es obvio: una unión económica, que no monetaria –porque el euro es un auténtico desastre para todos sus miembros excepto para Alemania–, entre la UE y Rusia daría lugar a la mayor potencia mundial, incluso sin el Reino Unido. No porque la suma de los PIB, algo irrelevante, diera lugar al mayor del planeta, sino porque la complementariedad y las gigantescas sinergias entre la Federación Rusa y la Unión Europea harían crecer como la espuma a sus países, al contrario que la situación actual, donde el expolio inmisericorde alemán de los países periféricos está empobreciéndolos hasta límites absolutamente inaceptables, algo que jamás ocurriría si existiera una federación con Rusia.

Este es un tema crucial para nuestro futuro como nación, para nuestra pobreza o para nuestra riqueza, y sobre el que el ignorante egoísmo que nos gobierna ni siquiera se ha percatado. Al igual que Aznar y su ministro basura Rato, que fue expulsado del FMI por inepto -algo que nunca había ocurrido antes-, al meternos en el euro, un auténtico desastre para nuestro país, cuando las funestas consecuencias estaban ya previstas y analizadas por Robert A. Mundell en su famosa teoría de las áreas monetarias óptimas: España no lo era ni de lejos. El tema, aparte de esencial para nuestro futuro, es de tanta envergadura, que hoy solo podemos apuntar los hechos clave, aunque dedicaremos dos o tres artículos a desarrollar en profundidad lo que hoy solo podemos esbozar.

El PIB 2012 a paridad de poder adquisitivo sería de 18,3 billones de dólares para la UE más la Federación Rusa, frente a 15,6 de EEUU. Pero lo importante es que la Federación Rusa posee los recursos energéticos, minerales y de todo tipo que Europa necesita, mientras que la UE tiene la tecnología y el mercado que Rusia requiere para explotar sus inmensas riquezas. Un ejemplo: las técnicas de fracking están permitiendo a EEUU obtener gas y electricidad a unos precios que son la mitad que los europeos y la tercera parte que en España; como consecuencia, numerosas industrias energético-intensivas europeas se están trasladando a los EEUU, en un proceso de desindustrialización masivo que no ha hecho más que empezar. Por otro lado, al tener industrias complementarias y no competitivas, el expolio de los pobres por los ricos en que hoy se ha convertido la UE en general y la Eurozona en particular terminaría de raíz.

¿A qué expolio me estoy refiriendo? Alemania y Francia han comprado a precio de saldo toda la industria y la agricultura ucranianas apoyados de forma entusiasta por sus corruptos gobernantes, como la Sra. Timoshenko, la gran ladrona del gas ante la que Sra. Cospedal se inclinó como si estuviera ante su Santidad el Papa, avergonzando a todos los españoles de bien. Las industrias siderometalúrgicas, una vez compradas por alemanes y franceses, están siendo cerradas y en vez de producir los miles de productos de primera necesidad que fabricaban las empresas ucranianas, los están importando de Alemania y Francia. Igual que hicieron con España en los 80, forzándonos a destruir nuestros astilleros, nuestras plantas siderúrgicas, nuestra cabaña lechera, nuestra flota pesquera –entonces la primera de Europa–; fue el precio que pagó para la homologación del PSOE y demás partidos estatales, que compraban a ese precio ruinoso su “certificado de democracia”.

Como dijo entonces González, ”hay que entrar como sea”, en lugar de esperar unos años, pues habríamos entrado de igual manera, pero sin destruir nuestra industria a favor de otros. Por ejemplo, la de la leche: después de haber sacrificado nuestra cabaña, empezamos a importarla de Francia. E igual con todo lo demás. Y luego el euro, que ha dado a Alemania la primacía absoluta y la imposibilidad de nuestras economías de competir al no poder devaluar y ni siquiera fluctuar entre dos bandas como en el antiguo Sistema Monetario Europeo, que es hoy lo único que podría salvarnos del desastre. De todo esto trataremos a fondo después de Semana Santa. El camino actual de siervos de Alemania nos lleva a la ruina. Por eso necesitamos a Rusia.

* Antonio García Trevijano es pensador.

Fuente: El Espía Digital

00:05 Publié dans Géopolitique, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : géopolitique, dostoïevsky, russie, europe, affaires européennes, lettres, lettres russes, littérature, littérature russe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

La «stratégie de la tension»

La «stratégie de la tension»

Le coup d’Etat de Kiev et la résistance dans l’Est de l’Ukraine

par Peter Bachmaier*

Ex: http://www.horizons-et-debats.ch

L’Ukraine d’aujourd’hui, dont le nom actuel «ukrainia» signifie «pays frontalier» (terme qui, à l’origine, n’était pas un terme ethnique), n’a été constituée comme Etat qu’au XXe siècle. La création de cette nation relève d’un processus contradictoire. Kiev était «la mère des villes russes», car au Xe siècle, le prince Vladimir y fonda un Etat indépendant, «le Rus de Kiev». En 988, il se convertit, avec tout son peuple, au christianisme orthodoxe (de tendance est-byzantine). Après des siècles d’empire lithuano-polonais, les Cosaques, c’est-à-dire des paysans libres et guerriers de la steppe du sud de l’Ukraine actuelle, fondèrent une entité politique quasi-étatique menant un combat contre la noblesse polonaise. En 1654, le hetman cosaque, Bogdan Chmelnizki, demanda au tsar russe d’intégrer l’Ukraine dans l’empire russe. Au cours du partage de la Pologne, à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, la plus grande partie de l’Ukraine fut attribuée à l’Empire russe, la Galicie et la Bucovine devinrent autrichiennes. L’Autriche gardait la langue et la culture ruthènes selon la terminologie de l’époque, tandis que la Russie décréta le russe comme langue nationale unique.

L’Ukraine, un produit de la politique soviétique relative aux nationalités

Dans le cadre de la politique soviétique relative aux nationalités, on fonda en 1918 la République soviétique de l’Ukraine dont l’existence prit fin en 1991. Bien qu’ayant vécu les horreurs de la guerre civile, de la collectivisation et de la famine qui en résulta mais aussi les purges politiques et les désastres de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, cette République finit par devenir un centre industriel et de recherche scientifique très développé.

L’Ukraine: un pays, deux langues

Le Dnjepr sépare le pays en deux: l’Est et le Sud avec Charkov, Dnepropetrovsk, Donetsk ainsi que la Crimée et Odessa parlent le russe et affichent des sympathies pro-russes, tandis que l’Ouest, avec Lviv parle l’ukrainien et manifeste une tendance antirusse et antisoviétique. Depuis 1991, l’unique langue administrative officielle est l’ukrainien.1

En 2012, après de longs débats, le Parlement a accepté de réintroduire le russe en tant que langue administrative régionale dans les régions orientale et méridionale de l’Ukraine, ce que le nouveau gouvernement a de nouveau annulé fin février 2014.

Du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, la presqu’île de la Crimée était occupée par les Ottomans. En 1762, elle fut intégrée à la Russie, qui installa son port de guerre à Sébastopol. La population de la Crimée est majoritairement russe. En 1954, Nikita Khrouchtchev échangea le territoire de Taganrog contre la Crimée qui fut intégrée dans l’Ukraine. Après 1991, la population de la Crimée se décida à créer une République autonome avec un président, un gouvernement et un Parlement à l’intérieur de l’Ukraine.

En décembre 1991, après un référendum organisé au lendemain de la chute de l’Union soviétique, le Soviet suprême de la République soviétique d’Ukraine déclara l’indépendance du pays. En 1994, l’Ukraine renonça à ses armes nucléaires. En contrepartie, la Russie, les Etats-Unis et la Grande-Bretagne déclarèrent, dans le mémorandum de Budapest, vouloir garantir la sécurité de l’Ukraine.

L’Ukraine, victime de la mondialisation

La nomenclature ukrainienne, c’est-à-dire l’élite de la bureaucratie soviétique ukrainienne, voulait obtenir l’indépendance face à Moscou et se tourna donc vers l’Occident. En 1992, le gouvernement ukrainien décida d’adhérer au Fond monétaire international (FMI) et, en 2004, il adhéra à l’Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC). Les conditions étaient claires: liberté des prix et du cours de change, ouverture des frontières aux capitaux étrangers, libéralisation, privatisation et dérégulation. Toute l’économie du pays fût mise aux enchères. La moitié des 500 000 entreprises durent abandonner leurs activités tandis que des grands groupes étrangers et les oligarques du pays achetèrent l’autre moitié. L’oligarchie qui se développa devint le facteur déterminant et le problème principal à l’intérieur de l’Ukraine parce qu’elle exerça et exerce encore une influence déterminante sur la politique et les médias. C’est le plus grand clivage entre l’élite et la grande masse de la population, existant en Europe.

Les résultats de l’intégration du pays dans le processus de la mondialisation sont catastrophiques: le Produit intérieur brut (PIB) est tombé à 70% entre 1991 et 2013, la production d’électricité est tombée à 65%, celle de l’acier à 43% et le nombre de scientifiques dans la recherche industrielle n’était plus que de 30%. Le salaire minimum s’élève, selon les indications officielles à 200 euros (en réalité c’est moins), la retraite minimum est de 160 euros (actuellement 80 euros) par mois, et 80% de la population vivent en-dessous du seuil de pauvreté. La population totale de l’Ukraine a diminué de 52 à 46 millions d’habitants et si l’on prend en compte les personnes vivant de manière permanente à l’étranger, ils ne restent plus que 38 millions.

La technologie peu développée, le retard comparé aux voisins à l’origine moins développés et l’émigration d’un quart de la population active du pays sont également des signes du déclin. Le modèle néolibéral agissant actuellement en Ukraine ramène l’économie à la périphérie mondiale et la maintient dans une situation semi-coloniale, en totale dépendance de l’Occident.

Au classement des pays du monde selon leur développement économique, l’Ukraine est tombée loin en arrière. De par son niveau de PIB (selon les informations de la CIA), l’Ukraine est au 140e rang avec 7500 dollars par habitant. Actuellement, c’est l’Irak qui est au 141e rang. L’Ukraine est devancée par Belize (Honduras britannique), la Bosnie-Herzégovine, l’Albanie ainsi que la Namibie, l’Algérie et le Salvador.

La révolution orange de 2004

Cette évolution, fondée à l’origine sur un mécontentement profond de la population, a aboutit en 2004 à la «Révolution orange». Les Etats-Unis financèrent à l’aide de leurs organisations d’aide, notamment la fondation «Widroschdennja» (renaissance) de George Soros, une insurrection de masse qui fut menée selon le manuel «De la dictature à la démocratie» du politologue américain Gene Sharp. La Révolution orange était une nouvelle méthode du coup d’Etat appliquant les moyens du «pouvoir doux» («Soft Power») à l’aide d’organisations non gouvernementales (ONG).2 L’agence serbe «Otpor» (résistance basée à Belgrade et dirigée par Srdja Popovi) joua un rôle important dans la planification et l’entrainement des activistes de l’insurrection.

Dans son émission «Weltjournal» du 1er mai 2011, la Radio autrichienne ORF donna des informations très détaillées sur les dessous de la Révolution orange. Lors d’une interview, Dmitro Potechin, membre du mouvement ukrainien «Pora», déclara que le changement, survenu en Egypte était également possible «dans notre région»: «Je pense à la Biélorussie ou à un nouveau mouvement en Ukraine. Et alors cela ira contre la Russie!»

Viktor Iouchtchenko devint président et nomma en janvier 2005 le gouvernement sous Julia Timochenko, devenue la femme la plus riche en Ukraine pendant la période de transformation. En mars 2007, Julia Timochenko se rendit à Washington, où elle offrit aux Américains de leur céder le gazoduc traversant l’Ukraine.

L’encerclement de la Russie

Du point de vue géopolitique, l’objectif du coup d’Etat de 2004 était l’endiguement de la Russie et le rapprochement de ce pays à l’OTAN. Dans son ouvrage fondamental «Le Grand Echiquier – L’Amerique et le reste du monde» (version originale: «The Grand Chessboard», 1997) Zbigniew Brzezinski déclare: «L’Ukraine est le pilier central. Sans l’Ukraine, la Russie ne sera plus une grande puissance eurasiatique.» En 1989 à Malte, Michail Gorbatchev, avait «renoncé» à l’Europe de l’Est, mais uniquement à condition que l’OTAN ne s’élargisse pas vers l’Est. En 1990, le secrétaire d’Etat américain James Baker, déclara que l’OTAN ne voulait pas une once du territoire d’Europe de l’Est.

Mais en 1997, on constitua l’alliance de sécurité GUAM (Géorgie, Ukraine, Azerbaïdjan, Arménie et Moldavie) financée par l’OTAN. En 2004, les Etats baltes ainsi que la Bulgarie et la Roumanie adhérèrent à l’OTAN. Les Etats-Unis implantèrent une série de nouvelles bases militaires en Géorgie, en Azerbaïdjan, en Kirghizstan et au Tadjikistan et décidèrent de construire des boucliers anti-missiles en Pologne et en Roumanie.

Depuis son indépendance, l’Ukraine avait développé des liens avec l’OTAN et adhéra en 1994 au Partenariat pour la paix de l’OTAN. En 1999, l’OTAN ouvrit une agence de liaison à Kiev. Depuis 1997, l’Ukraine participa régulièrement aux manœuvres effectuées par l’OTAN dans la mer Noire. Des unités ukrainiennes participèrent également aux interventions de l’OTAN au Kosovo et en Afghanistan, où elles opérèrent aux côtés des troupes polonaises et lithuaniennes. Depuis 2007, l’Ukraine participe à l’opération Active Endeaver de l’OTAN en charge d’assurer le contrôle de la Méditerranée.

Le 20 mai 2008, le président Viktor Iouchtchenko signa l’oukase mettant fin en 2017 au traité russo-ukrainien pour le stationnement de la flotte russe de la mer Noire à Sébastopol. Cet oukase représenta le début d’une campagne d’information et politique massive contre la flotte russe de la mer Noire et en même temps une campagne en faveur de l’adhésion de l’Ukraine à l’OTAN. En 2008, l’Ukraine décida, sous le président Iouchtchenko, d’adhérer à l’OTAN.

Pourtant la Révolution orange ne donna pas les résultats escomptés et fut une déception pour la population. Iouchtchenko et Timochenko se disputèrent pour des raisons personnelles. Début 2010, le président du «Parti des régions», Viktor Ianoukovitch, soutenu par l’oligarchie est-ukrainienne, fut élu président. Le parti remporta également la majorité au Parlement. Ianoukovitch ne put cependant pas changer la situation de manière substantielle.

Après de longues années de négociations avec l’UE, le gouvernement ukrainien déclara le 21 novembre 2013, qu’il n’allait pas signer l’accord d’association entre son pays et l’UE. Immédiatement après, des manifestations ressemblant à la Révolution orange de 2004 eurent lieu à Kiev et dans les grandes villes de l’ouest de l’Ukraine. Le refus de l’Ukraine de signer l’accord a été un revers important pour le Partenariat oriental de l’UE et pour l’OTAN. Le Partenariat oriental avait été fondé en 2009 à l’initiative de la Pologne et de la Suède et devait associer les anciens pays de l’Union soviétique (l’Ukraine, la Biélorussie, la Moldavie, la Géorgie, l’Arménie et l’Azerbaïdjan) avec l’UE. Le 29 novembre 2013, au sommet de Vilnius, l’accord d’association n’a été signé que par la Géorgie et la Moldavie.

Le gouvernement ukrainien a justifié sa décision par l’argument qu’il voulait préserver «ses intérêts de sécurité nationale». En effet, dans l’accord d’association, il était prévu d’installer«une coopération militaire étroite et l’intégration des forces armées ukrainiennes dans les troupes de combat stratégiques de l’UE». Sur le plan économique, l’UE exigeait la fin de la politique de prix étatique, une privatisation accélérée de tous les biens de l’Etat, des coupes dans les retraites et dans l’administration ainsi que l’ouverture du marché ukrainien pour les multinationales occidentales. Face à celles-ci, les entreprises ukrainiennes ne seraient jamais compétitives en Occident.

Economiquement, l’UE ne peut guère tirer profit de l’Ukraine. Elle serait un fardeau. Mais une association avec l’UE serait également fatale au niveau économique pour l’Ukraine et c’est la raison pour laquelle la décision du gouvernement ukrainien de ne pas signer cet accord, a été la meilleure solution pour les deux parties. Lors de la rencontre entre Poutine et Ianoukovitch du 17 décembre 2013 à Moscou, qui avait un «caractère stratégique», on s’est mis d’accord au sujet des rabais pour le prix du gaz et d’un crédit de plusieurs milliards de dollars. La Russie a offert d’investir, à l’aide du fond national du bien être dans des titres du gouvernement ukrainien un montant de 15 milliards de dollars et d’abaisser le prix du gaz d’un tiers.

L’influence des ONG occidentales

Les Etats-Unis n’ont jamais été d’accord avec Ianoukovitch en raison de ses relations entretenues avec Moscou, de son opposition à l’adhésion à l’OTAN et de sa prolongation de 20 ans du contrat avec la Russie concernant le stationnement de la flotte de la mer Noire à Sébastopol. Par conséquent, ils ont préparé un changement de régime.

En 2011, la fondation «Renaissance» organisa une rencontre des dirigeants des ONG en Ukraine, où elle décida de doubler leurs budgets. Actuellement, il y a 2200 ONG américaines et européennes en Ukraine. A la tête se trouve le National Endowment for Democracy, dont la vice-présidente Nadia Diuk dirigea en 2013 et en 2014 les activités de l’opposition. La coordination est exercée par l’agence USAID soumise aux ordres de l’Ambassade américaine. Les contacts avec les partis de l’opposition ont été activés en 2012.

Le Centre pour la démocratie de l’Europe orientale, financé par la fondation Charles Stewart Mott et dirigé par Zbigniew Brzezinski, joue un rôle important à Varsovie. Avec l’aide des ONG, les Etats-Unis créent des «cinquième colonne» et modifient la conscience de la société et de la culture, la manière de penser et les valeurs traditionnelles.

Les médias occidentaux comme Radio Liberty, Voix de l’Amérique, BBC, Deutsche Welle et les réseaux sociaux, s’exprimaient, depuis l’époque de la guerre froide, en langue ukrainienne et russe depuis l’Occident. Les groupes médiatiques tels Murdoch, Springer et Bertelsmann ont fondé leurs propres médias en Ukraine, afin d’influencer les populations au niveau culturel. Des universités occidentales ont créé des liens étroits avec des universités ukrainiennes, ont financés des projets de recherche et ont distribué des bourses à des étudiants ukrainiens voulant étudier en Occident.

En 2006, à l’initiative du président Iouchtchenko, on a fondé le «Mystetsklyi Arsenal» (Arsenal artistique), un énorme complexe culturel et artistique national à Kiev, dont le but est de faire apparaître l’Ukraine comme une partie de la culture européenne et de répandre l’art occidental contemporain. En 2012 a eu lieu dans ce bâtiment la Biennale internationale d’art moderne, dirigée par le conservateur David Elliott, à laquelle ont participé environ 100 artistes venant de 30 pays différents. Cet Arsenal artistique a également la tâche de répandre l’art ukrainien contemporain en Occident. En avril 2014, il a organisé grâce à l’intervention de l’Américain Konstantin Akinsha, commissaire en art d’origine ukrainienne, l’exposition «Je ne suis qu’une goutte d’eau dans l’océan» à la Maison des artistes de Vienne sur l’art de la révolution créé sur le Maïdan. De cette manière, les évènements du Maïdan sont présentés du point de vue des manifestants pro-occidentaux, à travers ces «œuvres d’art» produites grâce à la révolution (par exemple des affiches).

Le coup d’Etat de Kiev était planifié à l’avance

L’insatisfaction de la population, au vu de la situation économique misérable et de la corruption au sein du gouvernement, était tout à fait compréhensible. Le mouvement de protestation sur la Place Maïdan était composé de différentes forces, entre autre des groupes gauchistes et anarchistes. Les Etats-Unis étaient cependant la force motrice qui a dirigé les protestations contre le refus de signer l’accord d’association avec l’UE après le 21 novembre 2013.

A cette fin, l’Ambassade américaine de Kiev avait déjà entrepris plusieurs mois à l’avance des préparations en formant des activistes et en organisant une conférence sur les stratégies d’informations et prises d’influences sur les politiciens. De nombreux politiciens américains et pro-américains sont venus en Ukraine pour tenir des discours sur la Place Maïdan, notamment John McCain, Joseph Murphy, Victoria Nuland mais aussi Jaroslaw Kaczynski, Michail Saakashvili, Guido Westerwelle, Elmar Brok et beaucoup d’autres. Selon l’hebdomadaire polonais de gauche Nie du 18 avril 2014, la Pologne aurait elle aussi apporté une contribution essentielle au coup d’Etat. Aux frais du ministère polonais des Affaires étrangères, 86 membres du «Secteur droit» ont effectué en septembre 2013 un entraînement à l’insurrection de quatre semaines dans un centre de formation de la police près de Varsovie.

Le 16 janvier, le Parlement ukrainien a édicté des lois répressives, à l’aide desquelles les protestations devaient être limitées. Suite à cela, dans la nuit du 19 au 20 janvier, il y a eu des manifestations violentes de l’opposition qui a construit des barricades dans la rue Hrouchevsky au centre de la ville et occupé le ministère de la Justice, la mairie et d’autres établissements gouvernementaux. Le centre de Kiev a été dévasté. Une troupe extrémiste et violente, appelée «Secteur droit» s’est placée à la tête de la révolution. Klitchko et les meneurs de l’opposition parlementaire ont perdu tout contrôle des manifestants.

Puis, l’opposition pro-occidentale a pris le pouvoir dans 11 des 24 administrations territoriales, a destitué les gouverneurs, n’a plus reconnu le gouvernement de Kiev et a pris une série de décisions. Le drapeau noir et rouge du «Secteur droit» et le drapeau de l’UE ont été déclarés symboles officiels sur leur territoire et les activités du «Parti des régions» ont été interdites comme étant «hostiles au peuple». Le secrétaire d’Etat américain Kerry, a déclaré en février lors de la Conférence sur la sécurité de Munich: «Nulle part la lutte en faveur de la démocratie n’est actuellement plus importante qu’en Ukraine!»

Quand Ianoukovitch était prêt à accepter toutes les conditions de l’opposition parlementaire, l’escalade de la violence avait déjà débuté. Mais la réelle escalade a été provoquée par des tireurs d’élite professionnels qui ont tiré sur des policiers et sur des manifestants pour attiser la colère des gens et pour déclencher un chaos général. Le médecin Olga Bogomolez a déclaré qu’elle avait vu des manifestants et des policiers avec les mêmes blessures.

Le 21 février 2014, suite à une mission de médiation de l’UE sous la direction des ministres des Affaires étrangères allemand, français et polonais avec la participation d’un envoyé du gouvernement russe, on est arrivé à conclure un accord qui prévoyait de réinstaurer l’ancienne Constitution de 2004, de former un gouvernement d’unité nationale, de retirer la police et les manifestants armés et d’organiser de nouvelles élections avancées. De cette manière, les deux parties auraient plus ou moins pu sauver leur face et leurs intérêts.

Le gouvernement Yatseniouk n’est pas légitime

Un jour après la signature de cet accord de compromis, la situation avait complètement changé. Le 22 février, un jour après l’accord entre Ianoukovitch et l’opposition parlementaire, un coup d’Etat a été réalisé à Kiev. Le «Secteur droit» a occupé le Parlement et pris le contrôle à Kiev. Quelques députés ont été roués de coups, d’autres ont été empêchés d’entrer dans le Parlement. Lors d’un vote, le président Ianoukovitch a été destitué bien que selon la Constitution, une majorité de trois quarts des voix aurait été nécessaire. Le député Turschinov a été élu en tant que nouveau président d’Etat. Pour cela, il a fallu qu’une partie des députés présents votent deux fois et que ceux du «Parti des régions», payés par les oligarques, changent de côté et votent en faveur du nouveau pouvoir. Le Parlement a élu le chef en fonction du «Parti de la patrie», Arseni Jazenjuk en tant que Premier ministre. C’est lui qui était le candidat préféré du secrétariat d’Etat américain. Sur le site Internet de sa fondation «Open Ukraine» – plus accessible actuellement – les partenaires suivants étaient énumérés: l’Eglise de la Scientologie, The German Marschall Fund, Chatham House – Royal Institute of Foreign Affairs, la Fondation Rockefeller, la Fondation Konrad Adenauer, la Fondation «Renaissance», le National Endowment for Democracy. Le nouveau gouvernement est illégitime, parce qu’il n’a pas été élu par des élections générales, mais par une élection manipulée à la suite de laquelle la Verkhovna Rada est arrivée au pouvoir. L’ancien gouvernement et les fonctionnaires des ministères ont été renvoyés. Julia Timochenko a été libérée de la clinique de prison et est arrivée à Kiev, où elle a annoncé son retour au pouvoir sur la Place Maïdan.

Parmi les gouverneurs nommés par Kiev, il y a de vieilles connaissances de la politique ukrainienne, par exemple, Igor Kolomoiski, le troisième plus riche homme d’Ukraine, maintenant gouverneur de Dnipropetrovsk, copropriétaire de la «PrivatBank», la plus grande banque ukrainienne. Kolomoiski possède une double nationalité ukrainienne et israélienne et est un allié de Julia Timochenko. Le nouveau gouverneur de la région de Donezk, Sergej Taruta, dirige le plus grand groupe minier d’Ukraine et demeure un compagnon de route de Viktor Iouchtchenko.

L’Ukraine est actuellement près de la banqueroute de l’Etat qui aurait pu être évitée par l’accord avec la Russie prévu en décembre 2013. Maintenant, tout devient plus difficile. La Russie a réintroduit l’ancien règlement selon lequel l’Ukraine paie pour le gaz naturel le prix du marché mondial. Le FMI a offert un prêt de 15 milliards de dollars, lié aux conditions habituelles: réductions des dépenses de l’Etat, pas de subventionnement de la monnaie, ouverture des frontières et abolition des limites pour la vente de terres agricoles. L’UE pose les mêmes conditions que le FMI. Les crédits de l’UE seront financés par les contribuables. Au cas où l’accord d’association sera signé, l’UE devra ficeler, comme dans le cas de la Grèce, plusieurs «paquets de sauvetage».

Le 27 mars déjà, la Verkhovna Rada a approuvé le budget dicté par le Fond monétaire international, qui mènera à un abaissement massivement du standard de vie des Ukrainiens. Il faudra réduire fortement les dépenses et augmenter les impôts. Le prix du gaz pour les ménages a augmenté de 50% et la monnaie a été libérée. Le gouvernement a annoncé le plan d’économiser 1,2 milliards de dollars en gelant le salaire minimum et en réduisant les subventions et les prestations sociales. Des licenciements en masse, entre autre de 80 000 policiers, sont planifiés et cela malgré les tensions permanentes dans la rue.

Les protestations en Crimée et en Ukraine de l’Est

L’Ukraine et la Russie avaient signé le 28 mai 1997 un traité qui prévoyait une présence de la flotte russe en Crimée pendant 20 ans et la possibilité d’un prolongement automatique. Après que le nouveau gouvernement Yatseniouk ait envisagé de résilier cet accord et de faire adhérer le pays à l’OTAN, le Parlement de la République autonome de Crimée a décidé la réunification avec la Russie, ce qui a été confirmé par le référendum du 16 mars 2014. La Chartre des Nations Unies de 1948 stipule comme fondement du droit international, le droit des peuples à disposer d’eux-mêmes. C’est pourquoi, on peut considérer la sécession de la Crimée comme légitime, car il n’y a aucun doute que la grande majorité de la population était en faveur de la réunification de la Crimée avec la Russie [cf. Horizons et débats no 9 du 28/4/14, p. 1–2, ndlr.].

L’OTAN renforce son armement dans la région: des avions de combats ont été transférés en Pologne et patrouillent au-dessus de la Pologne, de la Roumanie et des pays Baltiques. L’OTAN conduit des manœuvres de la marine dans la mer Noire avec des navires de guerre américains, bulgares et roumains.

Le soulèvement en Ukraine orientale se base sur des forces d’autodéfense de la population russophone. Le gouvernement russe a déclaré qu’il ne voulait pas annexer les territoires de l’Ukraine orientale mais s’engager pour l’indépendance d’une Ukraine fédéralisée. Il a également approuvé, lors des entretiens de Genève le 16 avril, le désarmement de ces forces, toutefois à condition que les groupes armés tel le «secteur droit» à Kiev et en Ukraine occidentale déposent également leurs armes.

Le soulèvement en Ukraine orientale qui s’est développé depuis le coup d’Etat de février à Kiev, ne remonte pas uniquement aux différences culturelles entre l’Est et l’Ouest du pays et le non-respect des intérêts de la région orientale mais également à la détérioration de la situation économique générale et au manque d’espoir de la population, qui doit aussi vivre avec une dépréciation monétaire de 50%. La population s’oppose au gouvernement illégitime de Kiev et aux forces antirusses qui en font partie ainsi qu’aux Etats-Unis qui avancent constamment leurs pions. Un réel apaisement de la situation peut intervenir uniquement par un retrait des Etats-Unis qui soutiennent ce gouvernement. •

(Traduction Horizons et débats)

1 Jörg Baberowski. Zwischen den Imperien: Warum hat der Westen beim Konflikt mit Russland derartig versagt? Weil er nicht im Ansatz die Geschichte der Ukraine begreift. [Entre les empires: pourquoi l’Occident a-t-il tant échoué lors de son conflit avec la Russie? Parce qu’il ne comprend rien à l’histoire de l’Ukraine.] Die Zeit, n° 12, 13/3/2014

2 Natalja Narotschnizkaja (ed.). Oranschewye seti ot Belgrada do Bischkeka [Les réseaux oranges de Belgrade à Bischkek], Saint-Pétersbourg 2008

* Peter Bachmaier, spécialiste de l’Europe de l’Est, de 1972 à 2005 collaborateur du «Südosteuropa-Institut» et professeur à l’Université de Vienne, depuis auteur indépendant d’articles spécialisés.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, ukraine, russie, europe, affaires européennes, actualité, stratégie de la tension |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 16 mai 2014

Les Mistral pour la Russie : un enjeu stratégique majeur pour la France

Les Mistral pour la Russie: un enjeu stratégique majeur pour la France

par Aymeric Chauprade

En mars au journal de TF1, le ministre des affaires étrangères Laurent Fabius déclairait que « La France pourrait annuler les ventes des deux BPC si la Russie ne changeait pas de politique à l’égard de l’Ukraine et de la Crimée. »Les BPC, c’est-à-dire les Bâtiments de projection et de commandement, les deux navires militaires de type Mistral commandés en 2011 à la DCN (Direction des constructions navales).

Cette décision serait catastrophique à plusieurs égards. Pour le contrat lui-même bien sûr, qui pèse 1,2 milliards d’euros et qui conditionne un millier d’emplois à Saint-Nazaire. Il faudrait rendre l’argent déjà versé (la moitié), renvoyer la poupe des navires (construite en Russie) et s’acquitter d’importantes indemnités. En outre la France perdrait ses droits sur les plans du Mistral, déjà remis à la Russie, qui pourrait alors les construire elle-même. Une telle décision nous fermerait également la porte à tout futur contrat avec la Russie et notamment à son immense programme de réarmement naval (civil et militaire), estimé à plus de 50 milliards de dollars. Nos concurrents n’attendent que cela !

Mais au-delà, c’est la parole de la France qui est en jeu. Plusieurs contrats importants sont en cours de négociation, citons les 126 avions Rafale avec l’Inde pour un montant de 12 milliards d’euros, une série de contrats libanais financés par l’Arabie Saoudite pour 3 milliards de dollars, deux satellites espions avec les Emirats arabes unis… Mettons-nous à la place de ces pays, vont-ils s’engager plus loin sachant que ces méga-contrats peuvent être remis en cause du jour au lendemain pour des raisons diplomatiques ?

Car revenons à la source du problème : la Russie n’a pas militairement envahi la Crimée, auquel cas la question pourrait se poser, elle a simplement accepté le rattachement, après un référendum, de cette région très majoritairement peuplée de Russes et arbitrairement annexée à l’Ukraine en 1954. Si les différents diplomatiques, qui font partie de la vie des nations, même lorsqu’elles sont proches, doivent se traduire par des ruptures de contrats d’armement, autant faire une croix sur la capacité exportatrice de notre industrie de la défense ! Et au final sacrifier toute notre filière et perdre notre statut de puissance car, rappelons-le, ce secteur représente 165.000 emplois directs et autant d’emplois indirects, un chiffre d’affaire global de 17,5 milliards d’euros dont environ 30% est réalisé à l’exportation. La France est le quatrième exportateur d’armes mondial, derrière les États-Unis, la Grande-Bretagne et la Russie et ce résultat prouve l’excellence de nos industriels, que ce soit nos grands groupes ou notre réseau de PME. Se couper de cette compétition internationale à cause de revirements diplomatiques, perdre nos clients en rompant unilatéralement des contrats pourtant signés aurait des effets destructeurs sur l’ensemble de cet écosystème. Des milliers d’emplois seraient en jeu, mais aussi la place de la France dans le monde.

Le ministre de la défense Jean-Yves Le Drian a fait savoir que « la question de la suspension se posera au mois d’octobre » (date de livraison du premier BPC), « à condition que ce soit dans un ensemble de mesures » prises notamment au niveau européen. Il soumet ainsi la France à une décision prise à Bruxelles, ce qui est tout à fait inacceptable. La réintégration de la France dans le commandement intégré de l’OTAN en 2009 ne suffit pas, il faut qu’en plus elle fasse dépendre ses décisions de nature militaire de l’Union européenne ! Une UE qui ne possède pas de politique claire au niveau stratégique et demeure surtout inféodée aux intérêts américains (cf le Traité transatlantique), qui est tiraillée entre les intérêts contradictoires de ses membres, et qui s’incarne dans une personnalité controversée, aussi transparente que maladroite, à savoir Catherine Ashton. Et il faudrait que Paris abandonne encore sa souveraineté et se détermine par rapport à cet attelage qui ne sait pas où il va.

Dans ce domaine comme dans les autres, la France doit retrouver son indépendance, défendre ses intérêts stratégiques, penser en termes géopolitiques, dans la longue durée et non pas en fonction des émois soulevés par les journaux télévisés. L’industrie de la défense joue un rôle capital dans notre économie, par la place importante qu’elle occupe, par sa capacité exportatrice, on l’a dit, également par ses recherches en haute technologie qui profitent au secteur civil. Remettre en cause la livraison des deux navires commandés par la Russie reviendrait à se tirer une balle dans le pied, et dans cette optique tous les patriotes doivent clairement signifier au gouvernement qu’il fait fausse route.

Aymeric Chauprade

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Défense | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : marine, politique internationale, russie, france, europe, affaires européennes, défense, armées, mistral, ayméric chauprade |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 15 mai 2014

La Teoría del Corazón Continental de Mackinder y la contención de Rusia

por Niall Bradley*

Ex: http://paginatransversal.wordpress.com

“Lo que ha ocurrido en Crimea es una respuesta al modo en que colapsó la democracia en Ucrania. Y hay una única razón para esto: la política antirrusa de EE.UU. y algunos países europeos. Ellos buscan cercar a Rusia para debilitarlo y eventualmente destruirlo… Existe una cierta élite transnacional que durante 300 años ha anhelado este sueño.”

Lo que ha estado ocurriendo recientemente en Ucrania tiene muy poco sentido si no se ve en un amplio contexto histórico y geopolítico; así que en la búsqueda de un firme entendimiento de los eventos que se están desarrollando, he estado consultando libros de historia. En primer lugar es necesario decir que Ucrania ha sido históricamente parte de Rusia. Se constituyó como “una nación independiente” sólo en nombre a partir de 1991, pero ha sido completamente dependiente de la ayuda externa desde entonces. Y la mayoría de esta “ayuda” no ha sido, al menos, en su mejor interés.