In Jack Kerouac’s last piece of writing, “After Me, the Deluge,” the writer rued his influence on the hippie movement. In so doing, both in the Chicago Tribune magazine, where “Deluge” appeared in 1969, and during a pie-eyed appearance on Bill Buckley’s Firing Line the year before, Kerouac validated the pop-cultural notion that by going against the grain of Eisenhower’s suburban, conservative America, he unwittingly helped inspire the ’60s counterculture and its many excesses.

With its hobo squalor, its sexual candor, and most of all its aimless and irrepressible urge to roam, Kerouac’s famous On the Road, published in September of 1957, certainly appeared to signal a departure from the domestic conventions of the late 1950s. Relationships in the book are volatile and tenuous, while people and property are often exploited just for kicks. As a chronicle of freewheeling social disintegration, On the Road went down as a book very much at odds with its time, a foretaste of the cultural revolutions that rocked the late 1960s.

Often unnoticed or forgotten is that the road trips in Kerouac’s book were undertaken between 1947 and 1950, the postwar Truman years, in whose grain On the Road actually resides, even if Kerouac downplayed this fact. Betwixt the numerous travels that made up On the Road, Kerouac wrote his first book, The Town and the City (1950), a family history/coming-of-age novel in which World War II assumes its proper dimensions as an influence on the lives of his Martin family. Tellingly, however, Kerouac’s chief surrogate, young Peter Martin, was almost determinedly unmoved by it all: “Mighty world events meant virtually nothing to him, they were not real enough, and he was certain that his wonderful joyous visions of super-spiritual existence and great poetry were ‘realer than all.’”

Hence On the Road, a series of larks whose settings and patterns, preoccupations and mores, are marked by a recent conflict that goes almost entirely unmentioned. But the war’s influence was profound, starting with the wanderlust itself, which followed years of gasoline and tire rationing and Detroit’s suspension of automaking during the conflict. Further, space on Pullman cars and interstate buses was largely reserved for troops, furloughed GIs and their families, or those setting out to work in vital war industries. Everyone else had to stay put, scramble for the few remaining tickets, or venture into the black market.

With war’s end, people rushed to get behind the wheel and go, and automakers, tire manufacturers, oil companies, and others offered plenty of encouragement. Magazine ads of the time occasionally achieved near Kerouacian poetry in invoking the joyous splendors awaiting motorists. A Lincoln ad from 1945: “These grey years will end with brighter days … Then, free as a birdsong, you’ll share in the secrets of a thousand roads … Travel the taut highway that thins to a dot in the distance.” A Nash Motors ad from the same year was borderline orgasmic: “Waiting for you … wide highways that beg your car to spread her wings and fly … Her low, sweet motor-music as the miles race by … the way she quickens to a throttle-touch and leaps ahead to flatten out the hills and make the pavement sing beneath her wheels.”

Years later, Kerouac remarked that On the Road had been an investigation into “post-Whitman America,” an idea that tallied with a bit of doggerel (“Song of the Open Road … Again!”) produced in 1946 by Quaker State copywriters: “Oh, some roads stretch to Mexico, / And some roads stretch towards Nome, / And roads reach out from east and west, / And beckon us from home …”

Of course, as Kerouac sensitively attested in The Town and the City, the war had been beckoning Americans from home for years. He chronicled “the whole legend of wartime America … the great story of wandering, sadness, parting, farewell.” He marveled at “the young soldier-wives who were beginning to wander the nation … in search of some pitiable little home or situation that would bring them close to their young husbands, if only for a few months.” All this movement provoked “night-dreams woven out of three thousand miles of continental traveling … enacted upon some deranged little map of the mind that was supposed to represent the continent of America.” He added, “No one could see it, yet everyone was in it, and it was like the incomprehensible mystery of life … grown fantastic and homeless.” The members of his Martin family, being no exception, were also “uprooted by war,” part of the “great wartime wanderings” of that period.

Before On the Road’s protagonists, Sal and Dean, ever balled the jack across miles of open blacktop, moving from one brief habitation to the next, America was in the throes of temporary relocations, out-and-out migrations, and demographic shifts of an unprecedented scale. Some 15 million Americans were in uniform and away from home during the war, and Life reported that an estimated 75 percent of them did not intend to return to their hometowns. Nearly as many relocated owing to war-related industry, largely to be near shipyards and aircraft plants along the coasts and the Gulf Shore or near the veritable arsenal that emerged in and around Detroit. The sociologist Francis E. Merrill noted in 1948 that more than 27.5 million Americans “experienced at least one wartime change of residence that removed them from one set of social influences and often failed to substitute similar influences.” Roughly 20 percent of the population, in other words, was socially unmoored by the war.

And the migrations didn’t end with the war’s conclusion. Throughout the 1940s, an estimated 12 million Americans relocated to a new state. As a record of human movement within the country, this dwarfs the Great Migration (of Southern blacks to the North and Midwest), the second wave of which—beginning in 1940—is partly subsumed into this far larger, racially neutral tally.

Hidden within the numbers for that decade are various pathologies associated with social dislocation. This is what Merrill was hinting at when he noted that many Americans, in relocating, found themselves bereft of familiar social influences. Such influences serve as inhibitors, informally keeping most people from significant misbehavior. When you’re known to those around you, your actions naturally have greater social consequence than if you’re a stranger. Many of those 27.5 million during the war, and those 12 million over the course of the decade, were living—at least for a time—as virtual strangers in their new communities, which included occupied foreign capitals, stateside garrison towns, and American cities swelling with newly arrived defense workers. Furthermore, couples were often living apart (with, say, the man in uniform and the woman engaged in defense work), while children were subject to diminished supervision. Consequently, America in the ’40s experienced significant increases in promiscuity, infidelity, rape, out-of-wedlock births, divorce, venereal disease, auto theft, truancy, and juvenile delinquency.

Further, as Merrill noted, planning for the future is difficult in times of flux, and an uncertain future generates an equally uncertain present, which in turn produces indecision that can erode adherence to conventional mores. Thus, in The Town and the City we see one of the Martin daughters, Liz, elope at 18 with her piano-player boyfriend, leaving the town of Galloway (a fictionalized Lowell, Mass.) for Hartford, Conn. From there the two move to Detroit to find better-paying defense work. At 19, Liz delivers a stillborn baby in this strange and distant city, plunges into depression, and disappears from her family for a time. In the fall of 1945 she turns up in New York City (by way of San Francisco), separated from her husband and working as a nightclub singer when not occasionally flashing leg in “second-rate floorshows.”

“She had become one of the many girls in America,” Kerouac writes, capturing exactly the indecision Merrill noted, “who flit from city to city in search of something they hope to find and never even name, girls who ‘know all the ropes,’ know a thousand people in a hundred cities and places, girls who work at all kinds of jobs, impulsive, desperately gay, lonely, hardened girls.” All of which makes the roving escapades of Sal and Dean appear tamer in context. What seemed outré in the reading in 1957 was less so in the doing in 1947; less so, for that matter, in the reading in 1967, after the deluge Kerouac regretted had somewhat normalized many of the behaviors of 20 years prior, which—however prevalent they were at the time—were still considered misbehaviors. The excesses of the 1960s were in some ways a pale recurrence of those of the 1940s, the difference resting more in the attitude toward those excesses than in the excesses themselves.

♦♦♦

But it wasn’t just behaviors in the ’40s that had been changed by the war—behaviors, again, that put the Beats nearer the American mainstream than they seemed ten years later, when On the Road was finally published. Whole environments through which Kerouac moved in his travels had been changed—if not created—by the war. For instance, the Bay Area ghetto in which Kerouac (“Sal”) lives with a buddy for a time, while employed as a rent-a-cop, didn’t exist before the war. Kerouac called this black enclave “Mill City,” but it was actually Marin City (across the Golden Gate from San Francisco and just north of Sausalito), then a collection of hastily constructed dwellings put up at the beginning of the war to house thousands of newly arrived workers at a nearby shipyard. Among them were many African-Americans, whose population in the San Francisco-Oakland area grew sixfold during the war. Los Angeles saw a similar influx of African-American defense workers—as reflected in Chester Himes’s 1945 novel If He Hollers Let Him Go, in which a black machinist, as a wartime expediency, is put in an unaccustomed position of authority in the racially, politically, and (with a certain white Rosie the Riveter) sexually fraught atmosphere of a San Pedro shipyard.

When the war boom ended and the (mostly white) GIs came home to preferential hiring, these blacks were relegated once more to a poorer, often marginalized existence. But the scale and impact of such migrations went largely overlooked by Kerouac. Like Peter Martin in The Town and the City, he gave little thought to the shifting fortunes of whole human populations, preoccupied as he was with his joyous visions of super-spiritual existence. He described Mill City thus: “It was, so they say, the only community in America where whites and Negroes lived together voluntarily … and so wild and joyous a place I’ve never seen since.” This is classic slumming, oblivious of the fact that blacks at the time didn’t live anywhere “voluntarily” in the sense Kerouac implies. They lived where they were allowed to live, such as in cheap wartime shacks mostly ceded by whites following the peace and the drop-off in local industry, whereas Kerouac and others could pop in voluntarily for a time and admire the beat Negroes with their irrepressible laughter and happiness. As Kerouac writes at one point, “next door … lived a Negro called Mr. Snow whose laugh, I swear on the Bible, was positively and finally the one greatest laugh in all this world.”

To be fair, in “October in the Railroad Earth,” written in San Francisco several years after the travels that made up On the Road, Kerouac did reveal a fleeting, Joycean awareness of the grubbiness and disappointment that attended the large-scale migration of blacks to the West Coast during and after the war. He described a “poor grime-bemarked” street near the city’s Southern Pacific station as a scene of “lost bums,” including black migrants who—having long ago left the East only to find themselves now chronically unemployed—were in the grip of such hopelessness, irresponsibility, and lack of initiative that all they did was “stand there spitting in the broken glass, sometimes fifty in one afternoon against one wall at Third and Howard.”

The entire West Coast, of course, was changed by the war. Washington, Oregon, and California saw population increases ranging from 37 percent to more than 53 percent during the 1940s, and California experienced the greatest population increase of any state that decade, moving it for the first time into the top three in total population. More specifically, the war precipitated a westward migration that eventually (from 1940 to 1970) saw the black population of Los Angles grow tenfold and that of San Francisco-Oakland more than fifteenfold. It’s not too squiggly a line that connects the fleeting defense boom of the ’40s with such defining moments of the ’60s as the Watts Riots and the rise of the Black Panthers in Oakland; not too dim an influence that the boom had on such distinctive postwar artifacts as Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (the original blaxploitation film, from 1971, set in and around poverty-stricken black Los Angeles) and “Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers” (Tom Wolfe’s tragicomic 1970 essay on Bay Area race relations). Kerouac, of course, is not responsible for lack of awareness of future trends and events, even trends that were already somewhat discernible. Perhaps, to borrow from his description of wartime upheavals in The Town and the City, it was all so big that everyone was in it but no one could see it. However, it is a failure of imagination on his part to think that ghetto life was truly as joyous for those who lacked the options available to the free-ranging author. There had, after all, been a significant race riot in Harlem in 1943, touched off by the NYPD’s rumored mistreatment of a black vet. Kerouac, as an on-again, off-again student at Columbia and resident of New York City in the early ’40s, could be expected to have known about that riot.

♦♦♦

An influx of out-of-state Americans (white or black), however, wasn’t the only war-induced demographic change experienced by California and the West in the 1940s. Upon leaving Mill City, Kerouac/Sal headed for L.A. and, en route, hooked up with a Latina named Teresa, with whom he eventually lived for a spell in a San Joaquin Valley encampment near Fresno. There he picked cotton to raise money for a journey east, and for kicks frequented nearby “Mextowns” with Teresa and her brother, Rickey, “a wild-buck Mexican hotcat with a hunger for booze.” There were remnants of the old Dust Bowl migrants thereabouts, the Okies and Arkies famously portrayed in The Grapes of Wrath and After Many a Summer Dies the Swan. But the scene Kerouac describes is populated largely by Mexicans, with a touch of formerly Southern blacks—the predominance of the one and the presence of the other being artifacts of the recent war.

Mexicans, of course, were not exactly new in Central Valley agriculture, the history of which is a litany of one racial/ethnic/class group after another being recruited en masse and just as summarily dismissed based on harvests, populist resentments, and economic variables. First it was Native Americans and tramps; then Chinese laborers found in surplus after the railroad completion and the Gold Rush exhaustion; then Japanese immigrants; then, in the 1920s, large numbers of Mexicans, roughly 75,000 of them. The arrival of each itinerant, socially disenfranchised group helped depress the local wage base and, when combined with the unseemly poverty that thereby attended the farm-labor community, brought repeated calls from the local working classes for racial and ethnic restrictions, which—if passed—resulted only in the Central Valley growers’ finding another marginalized group to exploit. By the end of the 1920s, the process again repeated itself with importation of Mexicans in such numbers that an agitation emerged to place quotas on Mexican immigration. That prompted the growers to import Filipino workers, some 30,000 by 1930, according to Carey McWilliams in his book California: The Great Exception.

It was the Depression and the Dust Bowl that brought the likes of Tom Joad to the Central Valley, when white laborers suddenly found themselves in surplus. Roughly 350,000 Okies and Arkies, McWilliams noted, entered the agricultural labor pool in California between 1935 and 1938, in the process displacing Latinos and becoming the main focus of local resentment for their grotty, wage-depressing influence.

But this period in California culture, however immortalized in populist lore, was short-lived. The tide soon began to change once more, owing to a series of events related to America’s looming and then actual involvement in World War II. By 1940, Franklin Roosevelt had commenced an arms buildup in anticipation of U.S. war involvement, and the economy began to boom. That same year, Congress passed the first peacetime draft. Both events stirred those Okies and Arkies to rush into the military or to better-paying defense work. In the months following Japan’s December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the war, large-scale growers throughout the West faced an abrupt labor shortage. Filipino agricultural workers had also availed themselves of higher-paying industrial opportunities. And the entire West Coast population of Japanese-Americans (many of them, too, agricultural workers) had been forcibly relocated to the interior.

Produce was rotting on the vine, and ripened crops were being plowed under for lack of harvesting help. The result was the 1942 Mexican Farm Labor Agreement, the first of a series of treaties with Mexico more commonly known as the Bracero Program, by which the federal government sought the return, as provisional guest workers, of those “wetbacks” who had left or been repatriated at the onset of the Depression.

Under the Bracero Program—which, though conceived to address the exigency of food production in wartime, lasted until 1964—an average of 200,000 farm laborers a year were brought into the United States, almost certainly some of them known to Teresa, Rickey, and Sal from the Mextowns in and around Fresno in the late 1940s. Countless more arrived and operated outside the program, sometimes with the help of American agencies willing to make a burlesque of border enforcement for the sake of American business. Untold numbers of these melted away into various other corners of the American economy, thus making room for yet more cheap, politically impotent migrants from south of the border. The rush was contributing to ethnic tensions during Kerouac’s time in the San Joaquin Valley. He describes how Okies at a roadhouse near his and Teresa’s encampment “went mad” one night, tying a man to a tree and lashing him brutally with sticks. “From then on,” Kerouac writes, “I carried a big stick with me in the tent in case they got the idea we Mexicans were fouling up their trailer camp.”

So great was the demand for north-of-the-border toil at south-of-the-border wage rates that of course Bracero Program quotas couldn’t keep up. Consequently, human trafficking in brown-skinned labor was under way even before the 1940s ended. Such trafficking is the kernel of the crime in Ross Macdonald’s first novel, 1949’s The Moving Target, in which a dubious sun-cult temple atop a southern-California hillside serves as a receiving station for undocumented workers headed into the Bakersfield area.

♦♦♦

The bargain-based attraction of Mexico ran both ways, however, and in the spring of 1950 Kerouac and pals crossed the border themselves, driving south. Beat father figure William S. Burroughs had taken up residence in Mexico City and sent Kerouac a letter touting how far a man could make his dollar go yonder, “including all the liquor he can drink.” The road trip is the centerpiece of Part Four of On the Road, arguably the most Beat section in the book, with the dusty Mexican whores, the boyish excitement over Third World slumming, and the enormous joint the guys all share one afternoon (“the biggest bomber anybody ever saw”). But even here, off in the wilds, Kerouac was within the American zeitgeist. In January of 1948, Life revealed how a certain Mexican university, “accredited under the GI Bill of Rights,” had become a “paradise” to which veterans went to “study art, live cheaply and have a good time.” One of Kerouac’s travel companions, as it happens, had begged his way into the Mexican venture by promising that he could raise a hundred dollars and, once there, “sign up for GI Bill in Mexico City College.”

In fact, Kerouac’s life during On the Road was funded, at least in part, by checks he was receiving in his status as a World War II veteran, though his military service was nearly a farce. He served briefly in the Navy, spending a portion of his enlistment under psychiatric observation, before being discharged (honorably) as ill-fit for military life. (He did, however, undertake two sailings with the merchant marine, and this is hardly to be discounted. The merchant marine’s wartime casualty rate was comparable to that of the Marine Corps, and one of the ships on which Kerouac had sailed was torpedoed on its next outing, with significant loss of life.)

The checks Kerouac received after the war were earmarked for education: “It was over a year before I saw Dean again,” he writes of 1948, at the beginning of Part Two of On the Road. “I stayed home all that time, finished my book and began going to school on the GI Bill of Rights.” But those education checks mostly went to other purposes: “We got ready to cross the groaning continent again,” Kerouac writes elsewhere in Part Two. “I drew my GI check and gave Dean eighteen dollars to mail to his wife; she was waiting for him to come home and she was broke.” Later, when he and the guys were at Burroughs’s place in Louisiana, Kerouac was “waiting for my next GI check to come through.” Then, on the West Coast: “Dean and I goofed around San Francisco in this manner until I got my next GI check and got ready to go back home.” Later, in early 1949, “I had a few dollars saved from my GI education checks and I went to Denver, thinking of settling down there.”

Were it not for government largesse extended to the country’s veterans, On the Road might never have been written, a point Kerouac made—semi-lucidly—in 1969, in “After Me, the Deluge,” when railing against the relativism and anti-

establishmentarianism of kids those days:

So who cares anyhow that if it hadn’t been for western-style capitalism so-called (nothing to do with the black market capitalism in Jeeps and rice in Asia), or laissez-faire, free economic byplay, movement north, south, east, and west, haggling, pricing, and the political balance of power carved into the United States Constitution and active thus far in the history of our government, and my perfectly recorded and legitimatized United States coast guard papers, just as one instance of arch (nonanarchic) credibility in our provable system, I wouldn’t have been able or allowed to hitchhike half broke thru 47 states of this Union and see the scene with my own eyes, unmolested?

Of course, 25 years before, Kerouac was present at what was arguably the birth of that very anti-establishment, and his feelings then were a little more mixed. The later stretches of The Town and the City find Peter Martin in New York City in 1944, where he reunites socially with a charismatic acquaintance from his college days, the poet Leon Levinsky (Allen Ginsberg). Levinsky is full of loquacious enthusiasm for the coming day when everybody “is going to fall apart, disintegrate” and “all character-structures based on tradition and uprightness and so-called morality will slowly rot away.” He calls this eagerly anticipated event “the great molecular comedown.”

More to Levinsky’s taste is the milieu occupied by their mutual acquaintance Will Dennison (Burroughs), a heroin addict whose apartment is “overrun with people who dash about getting morphine prescriptions from dishonest doctors.” Dennison shares the apartment with his sister, who takes benzedrine to stay alert and help run the “madhouse,” including caring for Dennison’s child. “You’ve got to see it,” Levinsky remarks, “especially Dennison with his baby son in one hand and a hypo needle in the other, a marvelous sight.” Although Peter disagrees that it sounds marvelous, he otherwise skips right past that disturbing image to inquire after Dennison’s wife.

Peter also makes the mistake of likening Levinsky to a childhood friend from Galloway named Alexander Panos (Kerouac’s real-life Lowell friend Sebastian Sampas, a budding poet who enlisted in the Army and was eventually killed in the Italian campaign). To this well-intended comparison Levinsky responds with a hauteur that the world would eventually come to recognize in Ginsberg but that Peter, in Kerouac’s words, met only with “smiling indulgence.” Dismissing Panos’s “social conscience bleatings about the brotherhood of man,” Levinsky, with no protest from Peter, goes on to denounce Panos as a “smalltown Rupert Brooke,” a “joy-and-beauty poet of the hinterlands.”

It’s all the more interesting to note, then, that Kerouac’s voluminous correspondence—compiled, edited, and (in 1995) published by biographer and scholar Ann Charters—reveals the young Kerouac to have been much less forbearing toward Ginsberg than Peter Martin was toward Leon Levinsky. When Ginsberg dared reproach Kerouac for his own “peckerhead romanticism,” Kerouac, in a letter to Ginsberg dated August 23, 1945, replied by calling Ginsberg “unutterably vain and stupid,” after also having run down Burroughs and several other personalities from that scene, following a social event that Kerouac had found particularly distasteful.

Roughly two weeks later, in a follow-up letter to Ginsberg, Kerouac clarified his reaction to the Burroughs event, which he called “la soirée d’idiocie.” Referring obliquely to his own Catholic, conservative youth, he remarked, “You understand, I’m sure. Remember that the earlier part of my life has always been spent in an atmosphere vigorously and directly opposed to this sort of atmosphere … It automatically repels me, thereby causing a great deal of remorse, and disgust.” Having admitted his own ingrained prejudice, he then issued a far more elegant indictment of the anti-establishment than he was ever able to muster in his wretched, reactionary final years under the influence:

There is a kind of dreary monotony about these characters, an American sameness about them that never varies and is always dull … Like a professional group, almost. The way they foregather at bars and try to achieve some sort of vague synthesis between respectability and illicitness … That is annoying, but not half so much as their silly gossiping and snickering.

Warming to his irritation, and addressing the hauteur to which Ginsberg was prone to subject him, Kerouac offered this valediction:

There’s nothing that I hate more than the condescension you begin to show whenever I allow my affectionate instincts full play with regard to you; that’s why I always react angrily against you. It gives me the feeling that I’m wasting a perfectly good store of friendship on a little self-aggrandizing weasel. I honestly wish that you had more essential character, of the kind I respect. But then, perhaps you have that and are afraid to show it. At least, try to make me feel that my zeal is not being mismanaged … as to your zeal, to hell with that … you’ve got more of it to spare than I. And now, if you will excuse me for the outburst, allow me to bid you goodnight.

Yet this is the company he kept for what were his most productive and successful years—years when, under the guise of his various alter egos (Peter Martin, Sal Paradise, etc.), Kerouac feigned impressionability, his fictionalized selves shambling with childlike curiosity after one countercultural dynamo or another, thereupon to record their antics as something vitally American. To quote Sal Paradise, “the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’” Yet here again is Kerouac in that follow-up letter to Ginsberg in 1945 in which he recounted how repellent but also commonplace he found Burroughs’s social scene: “Strangely, the thing that annoys me the most is the illusion everyone has that I’m torn in two by all this … when actually, all I want is clear air in which to breathe, and there is none because everybody’s full of hot air.”

So much for mad talk and roman candles.

Thus, although he was right about the deluge, Kerouac was wrong (and evasive) about the sequence. The anti-establishment he bemoaned didn’t come after him, in the late 1960s or even the late 1950s. He helped conjure it into being as early as the mid-1940s, with the friends he kept and the stories he told, which began appearing in print in 1950. He denounced the hippies as so many bastard children of his misapprehended innocence. But his innocence was always a literary stratagem. The problem wasn’t that everyone misapprehended it but that we all fell for it in the first place.

Jon Zobenica’s writing has appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, The American Scholar, and The New York Times Book Review.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les lignes idéologiques du Mouvement social italien ont pris un tournant important en 1956, tournant analysé par Matteo Luca Andriola dans sa monographie La crisi di Suez e la destra nazionale italiana (La crise de Suez et la droite nationale italienne), publiée en 2020 par la maison d'édition florentine goWare.

Les lignes idéologiques du Mouvement social italien ont pris un tournant important en 1956, tournant analysé par Matteo Luca Andriola dans sa monographie La crisi di Suez e la destra nazionale italiana (La crise de Suez et la droite nationale italienne), publiée en 2020 par la maison d'édition florentine goWare.

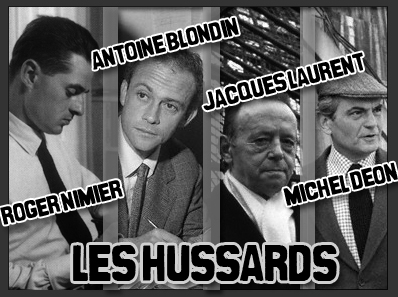

Il y a aussi qu'il me parait beaucoup plus difficile, inconfortable ou dangereux d'être un Nabe, un Millet, un Soral ou n'importe quel intervenant de "droite", d'extrême-droite ou "dissident" en 2020 que hussard en 1950 ou 1960. Sous la IVème république et au début de la Vème, le PCF faisait peut-être un quart des voix, mais il y avait encore un establishment culturel et littéraire " à droite" - dont notamment l'Académie française -, une presse de droite assez lue de Carrefour à La Nation française en passant par Rivarol ou La Parisienne. Et pratiquement pas de lois liberticides ni de communautarismes agressifs.

Il y a aussi qu'il me parait beaucoup plus difficile, inconfortable ou dangereux d'être un Nabe, un Millet, un Soral ou n'importe quel intervenant de "droite", d'extrême-droite ou "dissident" en 2020 que hussard en 1950 ou 1960. Sous la IVème république et au début de la Vème, le PCF faisait peut-être un quart des voix, mais il y avait encore un establishment culturel et littéraire " à droite" - dont notamment l'Académie française -, une presse de droite assez lue de Carrefour à La Nation française en passant par Rivarol ou La Parisienne. Et pratiquement pas de lois liberticides ni de communautarismes agressifs.

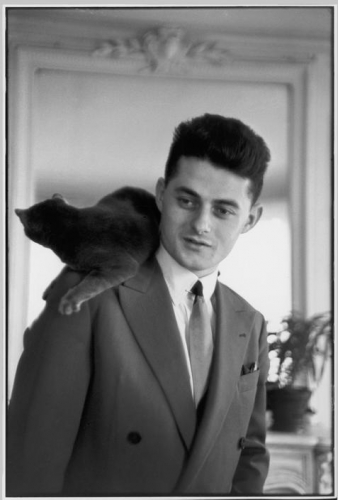

Les épigones de Nimier garderont donc le désabusement et s'efforceront de faire figure, pâle et spectrale figure, dans une société qui n'existe plus que pour faire disparaître la civilisation. La civilisation, elle, est une eau fraîche merveilleuse tout au fond d'un puits; ou comme des souvenirs de dieux dans des cités ruinées. L'allure dégagée de Roger Nimier est plus qu'une « esthétique », une question de vie ou de mort: vite ne pas se laisser reprendre par les faux-semblants, garder aux oreilles le bruit de l'air, être la flèche du mot juste, qui vole longtemps, sinon toujours, avant son but.

Les épigones de Nimier garderont donc le désabusement et s'efforceront de faire figure, pâle et spectrale figure, dans une société qui n'existe plus que pour faire disparaître la civilisation. La civilisation, elle, est une eau fraîche merveilleuse tout au fond d'un puits; ou comme des souvenirs de dieux dans des cités ruinées. L'allure dégagée de Roger Nimier est plus qu'une « esthétique », une question de vie ou de mort: vite ne pas se laisser reprendre par les faux-semblants, garder aux oreilles le bruit de l'air, être la flèche du mot juste, qui vole longtemps, sinon toujours, avant son but. Qu'en est-il de ce qui s'enfuit et de ce qui demeure ? Chaque page de Roger Nimier semble en « répons » à cette question qui, on peut le craindre, ne sera jamais bien posée par l'âge mûr, par la moyenne, - dans laquelle les hommes entrent de plus en plus vite et sortent de plus en plus tard, - mais par la juvénilité platonicienne qui emprunta pendant quelques années la forme du jeune homme éternel que fut et demeure Roger Nimier, aimé des dieux, animé de cette jeunesse « sans enfance antérieure et sans vieillesse possible » qu'évoquait André Fraigneau à propos de l'Empereur Julien.

Qu'en est-il de ce qui s'enfuit et de ce qui demeure ? Chaque page de Roger Nimier semble en « répons » à cette question qui, on peut le craindre, ne sera jamais bien posée par l'âge mûr, par la moyenne, - dans laquelle les hommes entrent de plus en plus vite et sortent de plus en plus tard, - mais par la juvénilité platonicienne qui emprunta pendant quelques années la forme du jeune homme éternel que fut et demeure Roger Nimier, aimé des dieux, animé de cette jeunesse « sans enfance antérieure et sans vieillesse possible » qu'évoquait André Fraigneau à propos de l'Empereur Julien.

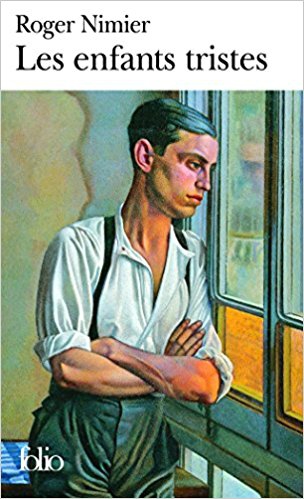

Le titre de l’essai d’Albert Camus est magnifique, même si le contenu ne m’a pas laissé un souvenir impérissable. Face à la vie politique présente, il n’est pas honteux, me semble-t-il, de ressentir une impression de révolte radicale, absolue, sans concession. Car le spectacle auquel nous assistons marque une détérioration permanente et l’absence de toute issue visible. Le fond du problème: il existe une caste médiatisée, de l’extrême droite à l’extrême gauche, qui se moque profondément du monde, ne vit que de propagande médiatique et prend les gens pour des crétins, indéfiniment manipulables. Les symptômes de ce phénomène:

Le titre de l’essai d’Albert Camus est magnifique, même si le contenu ne m’a pas laissé un souvenir impérissable. Face à la vie politique présente, il n’est pas honteux, me semble-t-il, de ressentir une impression de révolte radicale, absolue, sans concession. Car le spectacle auquel nous assistons marque une détérioration permanente et l’absence de toute issue visible. Le fond du problème: il existe une caste médiatisée, de l’extrême droite à l’extrême gauche, qui se moque profondément du monde, ne vit que de propagande médiatique et prend les gens pour des crétins, indéfiniment manipulables. Les symptômes de ce phénomène:

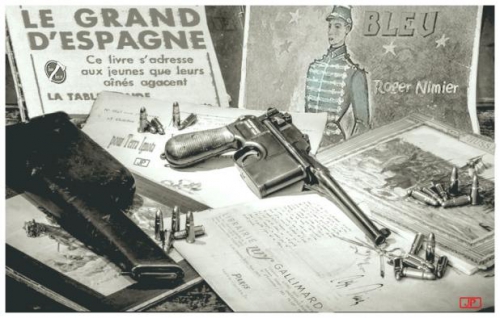

Au lancement de la Table Ronde, « agréable refuge où régnait un climat d’improvisation ingénue » dixit Michel Déon, la revue alors dirigée par François Mauriac collectionne quelques plumes illustres, et pour le moins hétérogènes : Albert Camus, Thierry Maulnier, Raymond Aron...

Au lancement de la Table Ronde, « agréable refuge où régnait un climat d’improvisation ingénue » dixit Michel Déon, la revue alors dirigée par François Mauriac collectionne quelques plumes illustres, et pour le moins hétérogènes : Albert Camus, Thierry Maulnier, Raymond Aron...

Je poursuis ici nos investigations dans les documents de mise en oeuvre de la Constitution de la Cinquième République telle qu’elle a été portée sur les fonts baptismaux par Charles de Gaulle en 1958.

Je poursuis ici nos investigations dans les documents de mise en oeuvre de la Constitution de la Cinquième République telle qu’elle a été portée sur les fonts baptismaux par Charles de Gaulle en 1958.

Il collabore, entre autres revues, à L’Insurgé, qui se réclamait à la fois de Jules Vallès et de Drumont, dont les orientations fascisantes et corporatives étaient connues. Curieusement, l’équipe de Je suis partout (auquel collabore aussi Maulnier), en particulier Lucien Rebatet et Robert Brasillach, montre une franche hostilité à une ligne éditoriale qu’ils jugent trop extrémiste… Pas étonnant que Maulnier se rapproche durant quelques temps de Jacques Doriot et du Parti populaire français. Il collaborera même à l’organe principal du PPF, L’Emancipation nationale. Il déteste toujours autant le conservatisme, écrivant : « Ce qui nous sépare aujourd’hui des conservateurs, c’est autre chose et beaucoup plus que leur lâcheté (Mon Dieu, qu’il a raison !) », ajoutant « Ce ne sont pas seulement les méthodes d’action conservatrices, ce sont les manières de penser conservatrices, ce sont les valeurs conservatrices qui nous sont odieuses. » Et il ajoute : « A bas l’Union sacrée ! Sous aucun prétexte, nous ne nous solidariserons avec la France d’aujourd’hui ! », concluant par ces mots : « C’est dans l’opposition, c’est dans le refus, c’est, le jour venu, dans la révolution, que réside notre seule dignité possible ». Il évoque cette « République démocratique (qui) ne peut être pour nous que la grande ennemie du peuple, le symbole de son oppression séculaire et des massacres qui l’ont assurée », ajoutant « Démocratie et capitalisme ne sont qu’un seul et même mal : on les abattra en même temps ». Et puis, ces mots (écrits, faut-il le préciser, avant la victoire allemande) : « La France est un pays envahi, un pays colonisé, un pays soumis à la domination étrangère ».

Il collabore, entre autres revues, à L’Insurgé, qui se réclamait à la fois de Jules Vallès et de Drumont, dont les orientations fascisantes et corporatives étaient connues. Curieusement, l’équipe de Je suis partout (auquel collabore aussi Maulnier), en particulier Lucien Rebatet et Robert Brasillach, montre une franche hostilité à une ligne éditoriale qu’ils jugent trop extrémiste… Pas étonnant que Maulnier se rapproche durant quelques temps de Jacques Doriot et du Parti populaire français. Il collaborera même à l’organe principal du PPF, L’Emancipation nationale. Il déteste toujours autant le conservatisme, écrivant : « Ce qui nous sépare aujourd’hui des conservateurs, c’est autre chose et beaucoup plus que leur lâcheté (Mon Dieu, qu’il a raison !) », ajoutant « Ce ne sont pas seulement les méthodes d’action conservatrices, ce sont les manières de penser conservatrices, ce sont les valeurs conservatrices qui nous sont odieuses. » Et il ajoute : « A bas l’Union sacrée ! Sous aucun prétexte, nous ne nous solidariserons avec la France d’aujourd’hui ! », concluant par ces mots : « C’est dans l’opposition, c’est dans le refus, c’est, le jour venu, dans la révolution, que réside notre seule dignité possible ». Il évoque cette « République démocratique (qui) ne peut être pour nous que la grande ennemie du peuple, le symbole de son oppression séculaire et des massacres qui l’ont assurée », ajoutant « Démocratie et capitalisme ne sont qu’un seul et même mal : on les abattra en même temps ». Et puis, ces mots (écrits, faut-il le préciser, avant la victoire allemande) : « La France est un pays envahi, un pays colonisé, un pays soumis à la domination étrangère ». Tout le monde connaît ces avions de papier que les lycéens jettent dans la rangée centrale de la classe quand ils s’ennuient. Le fuselage de l’avion était constitué par l’Esplanade des Invalides. Les ailes faisaient un triangle, dont les pointes étaient le pont de la Concorde, le pont des Invalides et l’extrême avancée, sur la rive droite, de l’avenue Nicolas II.

Tout le monde connaît ces avions de papier que les lycéens jettent dans la rangée centrale de la classe quand ils s’ennuient. Le fuselage de l’avion était constitué par l’Esplanade des Invalides. Les ailes faisaient un triangle, dont les pointes étaient le pont de la Concorde, le pont des Invalides et l’extrême avancée, sur la rive droite, de l’avenue Nicolas II.

Sieburg hörte nicht auf, den Mangel an Sittlichkeit und Höflichkeit in der Gesellschaft als Wucherungen anzusehen, zu denen nur westliche Demokratien als Mekka der Vulgarität und der Bequemlichkeit des Einzelnen in der Lage seien. Er beschrieb zudem das Dilemma, ohne Traditionsbewusstsein dem Zeitgeist zu verfallen und so die Vergangenheit nicht verarbeiten zu können, der man sich nach 1945 nur schwerlich stellen konnte. Stattdessen gehe der Mensch in einer anonymen Menge unter, der eine einigende Idee fehle und in der soziale Bindungen kaum noch durch Familie und Fleiß und vielmehr über staatliche Transferleitungen erlogen werden.

Sieburg hörte nicht auf, den Mangel an Sittlichkeit und Höflichkeit in der Gesellschaft als Wucherungen anzusehen, zu denen nur westliche Demokratien als Mekka der Vulgarität und der Bequemlichkeit des Einzelnen in der Lage seien. Er beschrieb zudem das Dilemma, ohne Traditionsbewusstsein dem Zeitgeist zu verfallen und so die Vergangenheit nicht verarbeiten zu können, der man sich nach 1945 nur schwerlich stellen konnte. Stattdessen gehe der Mensch in einer anonymen Menge unter, der eine einigende Idee fehle und in der soziale Bindungen kaum noch durch Familie und Fleiß und vielmehr über staatliche Transferleitungen erlogen werden. Futur auteur de Le zéro et l’infini, Arthur Koestler avait joué un rôle important dans la guerre d’Espagne comme agent du Komintern. Par ses écrits, il avait donné le ton d’une propagande antifranquiste qui a perduré. Plus tard, ses déceptions firent de lui un critique acéré du stalinisme. À l’été 1942, il publia un texte qui marquait sa rupture : Le yogi et le commissaire. Deux théories, écrivait-il, prétendent libérer le monde des maux qui l’accablent. La première, celle du commissaire (communiste) prône la transformation par l’extérieur. Elle professe que tous les maux de l’humanité, y compris la constipation, peuvent et doivent être guéris par la révolution, c’est-à-dire par la réorganisation du système de production. À l’opposé, la théorie du yogi pense qu’il n’y a de salut qu’intérieur et que seul l’effort spirituel de l’individu, les yeux sur les étoiles, peut sauver le monde. Mais l’histoire, concluait Koestler, avait consacré la faillite des deux théories. La première avait débouché sur les pires massacres de masse et la seconde conduisait à tout supporter passivement. C’était assez bien vu et totalement désespérant.

Futur auteur de Le zéro et l’infini, Arthur Koestler avait joué un rôle important dans la guerre d’Espagne comme agent du Komintern. Par ses écrits, il avait donné le ton d’une propagande antifranquiste qui a perduré. Plus tard, ses déceptions firent de lui un critique acéré du stalinisme. À l’été 1942, il publia un texte qui marquait sa rupture : Le yogi et le commissaire. Deux théories, écrivait-il, prétendent libérer le monde des maux qui l’accablent. La première, celle du commissaire (communiste) prône la transformation par l’extérieur. Elle professe que tous les maux de l’humanité, y compris la constipation, peuvent et doivent être guéris par la révolution, c’est-à-dire par la réorganisation du système de production. À l’opposé, la théorie du yogi pense qu’il n’y a de salut qu’intérieur et que seul l’effort spirituel de l’individu, les yeux sur les étoiles, peut sauver le monde. Mais l’histoire, concluait Koestler, avait consacré la faillite des deux théories. La première avait débouché sur les pires massacres de masse et la seconde conduisait à tout supporter passivement. C’était assez bien vu et totalement désespérant. Un investigador estadounidense afirma que la CIA está detrás del misterioso caso del “pan maldito”, aparente intoxicación alimentaria con síntomas de desorientación mental que afectó en agosto de 1951 a los vecinos de la localidad francesa Pont-Saint-Esprit, con un balance de cinco muertos y 300 afectados, 30 de los cuales fueron recluidos por largos años en centros psiquiátricos.

Un investigador estadounidense afirma que la CIA está detrás del misterioso caso del “pan maldito”, aparente intoxicación alimentaria con síntomas de desorientación mental que afectó en agosto de 1951 a los vecinos de la localidad francesa Pont-Saint-Esprit, con un balance de cinco muertos y 300 afectados, 30 de los cuales fueron recluidos por largos años en centros psiquiátricos. Pour Hans Freyer (1887-1969),

Pour Hans Freyer (1887-1969), Wie zuverlässige amerikanische Quellen berichten, ist beim Bureau of Intelligence and Research des US-Außenministeriums eine vertrauliche Anfrage des Büros von Erard Corbin de Mangoux, dem Chef des französischen Auslandsnachrichtendienstes DGSE (Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure) eingegangen. Den Berichten zufolge bezieht sich die Anfrage auf die kürzlich veröffentlichte Darstellung über die Mitschuld der US-Regierung an dem mysteriösen Ausbruch von Massenwahnsinn in dem südfranzösischen Dorf Pont-Saint-Esprit im Jahr 1951.

Wie zuverlässige amerikanische Quellen berichten, ist beim Bureau of Intelligence and Research des US-Außenministeriums eine vertrauliche Anfrage des Büros von Erard Corbin de Mangoux, dem Chef des französischen Auslandsnachrichtendienstes DGSE (Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure) eingegangen. Den Berichten zufolge bezieht sich die Anfrage auf die kürzlich veröffentlichte Darstellung über die Mitschuld der US-Regierung an dem mysteriösen Ausbruch von Massenwahnsinn in dem südfranzösischen Dorf Pont-Saint-Esprit im Jahr 1951. Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1985

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1985 Peu après 1989, on pensait que le monde libre et la démocratie avaient triomphé grâce à la victoire des Etats-Unis sur l’Union soviétique. La réalité de 2009 est différente. Le modèle démocratique américain ne s’est de loin pas imposé partout à travers le globe. […] Dans la politique américaine, il y a des relents de Guerre froide. L’attitude de Washington par rapport à Cuba n’a pas fondamentalement changé.

Peu après 1989, on pensait que le monde libre et la démocratie avaient triomphé grâce à la victoire des Etats-Unis sur l’Union soviétique. La réalité de 2009 est différente. Le modèle démocratique américain ne s’est de loin pas imposé partout à travers le globe. […] Dans la politique américaine, il y a des relents de Guerre froide. L’attitude de Washington par rapport à Cuba n’a pas fondamentalement changé.