jeudi, 14 janvier 2010

Qui était Barry Fell?

Qui était Barry Fell ?

Qui était Barry Fell ?

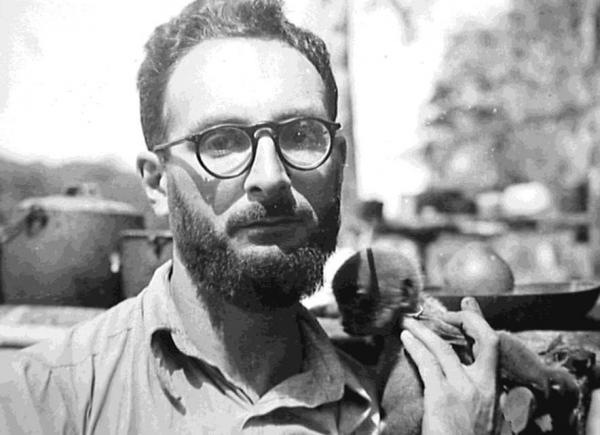

Né en 1917 et décédé en 1994, Barry Fell était professeur d’océanographie à l’Université de Harvard aux Etats-Unis. Il déchiffra le Linéaire B crétois. Son domaine de recherche privilégié était la préhistoire de l’Amérique du Nord. Au cours de ses travaux, il s’intéressa tout particulièrement aux signes de l’Ibérie préhistorique, à l’écriture ogham irlandaise et à l’écriture tifinagh berbère, que les pionniers marins venus d’Europe en Amérique du Nord à la préhistoire ont laissé comme traces, surtout sous la forme d’inscriptions rupestres à l’âge du bronze. Fell est le savant qui a découvert les liaisons transatlantiques entre l’Europe et l’Amérique du Nord, telles qu’elles étaient organisées il y a des millénaires. Les résultats de ses recherches ont été publiés pour l’essentiel dans les Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers.

Ouvrages principaux :

America B.C. – Bronze Age America, 1982.

Saga America, 1988.

Son principal disciple est l’Allemand Dietrich Knauer (né en 1920).

00:10 Publié dans anthropologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : anthropologie, épigraphie, préhistoire, amérique, protohistoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 22 décembre 2009

Le monothéisme comme système de pouvoir en Amérique latine

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1999

Le monothéisme comme système de pouvoir en Amérique latine

Jacques-Olivier MARTIN

Considéré comme le bastion traditionnel du catholicisme, l'Amérique latine est actuellement l'enjeu de luttes d'influence entre différents groupes religieux chrétiens dont le prosélytisme atteint son paroxysme. Vivement encouragés par les dirigeants politiques du continent, le développement des sectes protestantes permet d'assurer le contrôle politique de populations misérables qui constituent le terreau des guérillas anti-américaines et dont quelques prêtres catholiques, adeptes de la Théologie de la Libération ont pris la défense. Particulièrement visés par cette stratégie, les Indiens constituent en effet une menace pour le système car ils associent revendications sociales et défense de leur identité culturelle et religieuse. D'où l'intéret d'une religion associant individualisme, universalisme et soumission à I'ordre établi, valeurs par excellence d'une société soumise à I'hégémonie américaine.

Un continent soumis depuis cinq siècles à l'hégémonie européenne, puis américaine

Avec l'accession à l'indépendance des anciennes colonies de la couronne d'Espagne, l'Amérique latine connaît tout le contraire d'un processus d'émancipation durant le XIXième siècle. Ses élites politiques, essentiellement espagnoles, ne parviennent pas à contrer les plans de l'Angleterre qui impose le morcellement de l'empire en une kyrielle de petits États. C'est ainsi qu'ils font échouer, en 1839, le projet de Grande-Colombie initié par Simon Bolivar, et font exploser les Provinces-Unies d'Amérique centrale en plusieurs petits États de taille ridicule. Conformément à sa logique de thalassocratie, l'Angleterre empêche ainsi la constitution de toute puissance continentale qui pourrait contester les règles commerciales et financières qu'elle impose facilement à de petits États clients.

Les États-Unis, malgré la politique de solidarité panaméricaine annoncée par la doctrine de Monroe datant de 1823, se méfient aussi de l'émergence d'une puissance ibéro-américaine. La création du micro-Etat panaméen en 1903 est la mise en application la plus éloquente de ce principe, les Américains fomentant une révolte contre la Colombie pour obtenir la sécession du Panama, afin de se faire concéder la souveraineté sur le canal par un régime panaméen faible et soumis à l'Oncle Sam.

L'éclatement de l'Amérique latine en une vingtaine d'États ouvre pour le continent une ère de chaos et d'anarchie entretenue par les grandes puissances. Des conflits meurtriers opposent ainsi de jeunes nations; tels que la guerre du Pacifique des années 1880, entre le Pérou et la Bolivie d'une part, et le Chili d'autre part. Les dépôts de nitrate du désert d'Atacama suscitaient en effet la convoitise des trois États mais les capitalistes européens ont soutenu financièrement le Chili, vainqueur du conflit, car le gouvernement péruvien avait appliqué une politique spoliatrice à leur égard. La stratégie américaine du Big Stick (gros bâton) et de la diplomatie du dollar vient concurrencer les Européens, surtout vers la fin du XIXième siècle, lorsque les Etats-Unis chassent les Espagnols de Porto-Rico et de Cuba, îles dans lesquelles ils avaient investi dans les plantations de canne à sucre. En 1901, l'amendement Platt voté par le Sénat transforme Cuba en un protectorat de fait, Haïti et Saint-Domingue subissant le même sort en 1916 et en 1923. Quant à la diplomatie du dollar, elle s'applique aux États plus solides ou plus éloignés de la sphère d'influence américaine.

Le sous-développement endémique dont a toujours souffert l'Amérique latine s'explique donc en partie par sa dépendance politique. La composition ethnique des États de la région, héritage de la colonisation espagnole, ne fait qu'aggraver le phénomène car, face à une masse indigène, noire ou métisse, une élite créole affiche un sentiment de supériorité sociale et ne montre guère d'intérêt pour le développement économique. Lorsqu'une mine est exploitée à l'aide de capitaux et d'ingénieurs européens, il est fréquent que la ligne de chemin de fer qui achemine le minerai destiné à l'exportation vers le port ne soit même pas connectée à la ville la plus proche.

La Révolution mexicaine de 1912 est sans doute la première réaction notable à cette situation de pillage du pays par les capitalistes étrangers et leurs collaborateurs locaux. Le Mexique était en effet dépossédé de ses champs pétrolifères dont la concession était accordée aux compagnies anglo-saxonnes; tandis que lrs terres se concentraient entre les mains de quelques familles au détriment des communautés indiennes. Cette Révolution est l'aboutissement d'un mouvement pour l'émancipation des Indiens et contre le capital étranger, s'accompagnant de la lutte contre le clergé catholique qui est considéré comme le meilleur allié du régime. Le rôle de ce dernier a été déterminant dans les conflits qui ont ponctué l'histoire de l'Amérique latine, surtout au XXième siècle, période de remous et de mutations pour l'Église catholique.

La Révolution mexicaine de 1912 est sans doute la première réaction notable à cette situation de pillage du pays par les capitalistes étrangers et leurs collaborateurs locaux. Le Mexique était en effet dépossédé de ses champs pétrolifères dont la concession était accordée aux compagnies anglo-saxonnes; tandis que lrs terres se concentraient entre les mains de quelques familles au détriment des communautés indiennes. Cette Révolution est l'aboutissement d'un mouvement pour l'émancipation des Indiens et contre le capital étranger, s'accompagnant de la lutte contre le clergé catholique qui est considéré comme le meilleur allié du régime. Le rôle de ce dernier a été déterminant dans les conflits qui ont ponctué l'histoire de l'Amérique latine, surtout au XXième siècle, période de remous et de mutations pour l'Église catholique.

L'Église catholique dans la tourmente révolutionnaire.

Les sociétés latino-américaines ont longtemps été dominées par la trilogie Evêque-Général-Propriétaire terrien. Cette alliance du sabre et du goupillon est conforme à la définition de la religion, certes restrictive —mais particulièrement pertinente lorsque l'on analyse le rôle de l'Église catholique sur ce continent— du sociologue français Pierre Bourdieu. Selon lui, le religieux se caractérise par sa fonction de conservation et de légitimation de l'ordre social. Si les diverses religions polythéistes traditionnelles encore pratiquées à travers le monde ont rarement pour objectif de conquérir et d'influencer le pouvoir, les monothéismes chrétien et musulman ne font quant à eux pas preuve de la même faiblesse, s'appuyant largement sur les régimes politiques en place, quelle que soit leur nature.

Le Vatican joue d'ailleurs un rôle direct dans la politique latino-américaine, tel le nonce apostolique négociant la reddition de Noriega à Panama ou le cardinal de Managua qui œuvre à la recomposition politique d'une opposition au gouvernement sandiniste. Si l'Église a constitué la première force d'opposition au régime du général Pinochet, la majorité de la hiérarchie catholique conservatrice du Brésil contribue à la chute du président J. Goulard en 1964 et à l'instauration du gouvernement militaire. En organisant «une marche avec Dieu pour la famille et la liberté»,en mars 1964, avec le financement de la CIA et du patronat, elle assène un coup décisif au régime civil. Son but est en effet de mettre un terme aux réformes sociales entamées par le régime, assimilées à une évolution vers le communisme et soutenues par la minorité réformiste du clergé s'inspirant de Dom Helder Camara.

L'Église est aussi au centre des conflits qui ensanglantent l'Amérique centrale depuis des années, où elle torpille le projet réformiste du président Arbenz au Guatemala. Au nom de l'anti-communisme, le Congrès eucharistique réunit 200.000 personnes en 1951dans une croisade pour la «défense de la propriété». Par la suite, le cardinal Casariego restera muet sur les atrocités commises par les juntes au pouvoir à partir de 1954. Quant à la famille Somoza, elle a bénéficié aussi du soutien de l'Église nicaraguéenne, l'archevêque de Managua sacrant, en 1942, la fille du dictateur reine de l'armée avec la couronne de la Vierge de Candelaria.

La Théologie de la libération rompt avec l'attitude traditionnelle de l'Église catholique.

Le changement d'attitude de l'Église date de la fin des années cinquante, à la suite du choc causé par la révolution cubaine de 1958. Bien avant la convocation du Concile Vatican II, le pape Jean XVIII manifeste en effet la volonté que l'épiscopat latino-américain sorte de son inertie et s'adapte aux réalités du continent, soulignant l'urgence d'une réforme des structures sociales. Selon lui, l'Église doit retrouver l'appui des masses en adoptant un discours différent de celui de l'acceptation des rapports sociaux, idée développée lors du congrès de Medellin de 1968.

Le Concile Vatican II développe ainsi plusieurs thèmes devant réconcilier le peuple et son Église, qui doit désormais se considérer comme le «peuple de Dieu». Le rôle du laïc est revalorisé afin de rendre plus active la participation de tous les fidèles aux célébrations liturgiques et à l'enseignement du catéchisme. Les paroisses sont décentralisées pour que des «communautés de base» s'auto-organisent dans le monde rural et dans les bidonvilles. L'intérêt que présentent ces communautés est double: d'une part elles intègrent dans les chants et les rituels certains éléments de la religiosité populaire, d'autre part elles sont le lieu où les populations pauvres discutent des problèmes quotidiens avec des animateurs.

En Amérique centrale, ces théologiens de la libération sont même à l'origine du développement de plusieurs mouvements révolutionnaires, effectuant un travail de conscientisation des masses et brisant le tabou de l'incompatibilité entre chrétiens et marxistes. Che Guevara est le symbole de cette pensée christo-marxiste qui reconnaît le droit à l'insurrection. En outre, le “Che” fait figure de martyr dans les églises populaires. En disant que la révolution latino-américaine serait invincible quand les chrétiens deviendraient d'authentiques révolutionnaires, il prouvait que ce basculement idéologique de l'Église risquait de déstabiliser des régimes politiques privés de réels soutiens populaires.

Au Nicaragua, où les communautés de base diffusent la propagande du front sandiniste, le Père Ernesto Cardenal est converti par les Cubains aux thèses révolutionnaires et prône l'idée que le royaume de Dieu est de ce monde. Les chrétiens seront d'ailleurs représentés dans le gouvernement sandiniste dans lequel ils auront quatre ministres. Au Guatemala, la jeunesse d'action catholique rurale se rapproche des communautés paysannes indiennes en révolte dans les années soixante, l'accentuation de la répression militaire contribuant à ce phénomène.

C'est au Salvador que la solidarité entre les guérilleros et les chrétiens progressistes est la plus frappante, ces derniers étant plus nombreux que les marxistes dans le mouvement de guérilla. Le réseau des centres de formation chrétienne mobilise les paysans salvadoriens, combinant évangélisation, alphabétisation, enseignement agricole et éveil socio-politique. Le parcours de Mgr Romero, l'archevêque de San Salvador constitue presque l'archétype de cette prise de conscience politique de certains hommes d'Église. L'élection au siège archiépiscopal de cet évêque conservateur proche de l'Opus Dei avait enchanté les dirigeants du pays, le Vatican l'ayant choisi pour faire contrepoids à son prédécesseur, Mgr Chavez, qualifié d'«archevêque rouge». Mais, suite à l'un des nombreux assassinats de prêtres par les militaires survenu en 1977, il rejoint les rangs des révolutionnaires avant de se faire à son tour assassiné. Étant devenu le martyr de la révolution salvadorienne, il est l'un des symboles d'un phénomène qui inquiète de plus en plus le Vatican.

La mise à pieds des chrétiens progressistes par Jean-Paul II

La Théologie de la libération, impulsée par des intellectuels occidentaux et par des prêtres latino-américains venus étudier dans les universités européennes, a donc trouvé dans les réalités socio-politiques du continent le terreau favorable à son expansion. Dès le début des années 80, Jean-Paul II, pape farouchement anticommuniste, tente cependant de juguler ce mouvement. En 1984, une “instruction sur quelques aspects de la Théologie de la libération” fait le point sur ce phénomène en évitant de le condamner en bloc mais en critiquant certaines de ses dérives. Dans ce document, le cardinal Ratzinger, préfet de la congrégation de la foi met en garde contre le risque de perversion de l'inspiration évangélique par la philosophie marxiste.

La Théologie de la libération, impulsée par des intellectuels occidentaux et par des prêtres latino-américains venus étudier dans les universités européennes, a donc trouvé dans les réalités socio-politiques du continent le terreau favorable à son expansion. Dès le début des années 80, Jean-Paul II, pape farouchement anticommuniste, tente cependant de juguler ce mouvement. En 1984, une “instruction sur quelques aspects de la Théologie de la libération” fait le point sur ce phénomène en évitant de le condamner en bloc mais en critiquant certaines de ses dérives. Dans ce document, le cardinal Ratzinger, préfet de la congrégation de la foi met en garde contre le risque de perversion de l'inspiration évangélique par la philosophie marxiste.

Par peur de se couper définitivement d'un mouvement dont il espère toujours récupérer les bénéfices, il ne condamne pas ouvertement les prêtres progressistes mais il adresse des critiques régulièrement à ceux qui confondent christianisme et marxisme. C'est ainsi qu'il avait demandé, sans succès, de se retirer aux quatre prêtres membres du gouvernement sandiniste. De même, il entretenait des relations difficiles avec Mgr Romero à qui il reprochait son zèle excessif dans l'action sociale, demandant quand même au président Carter de cesser son aide à une armée salvadorienne “qui ne sait faire qu'une chose: réprimer le peuple et servir les intérêts de l'oligarchie salvadorienne”. Au Nicaragua, alors qu'il célèbre une messe à Managua en 1983, il fait une prière pour les prisonniers du régime mais passe sous silence les crimes des contras.

Dans son “instruction sur la liberté chrétienne et la libération” en 1986, le cardinal Ratzinger ne renie pas la préférence de l'Eglise pour les pauvres, le discours du Vatican tentant en fait de s'approprier la théologie de la libération mais en aseptisant le discours de ses aspects les plus révolutionnaires. La seconde stratégie adoptée par Jean-Paul II consiste à nommer systématiquement des évêques conservateurs de l'Opus Dei à la tête des diocèses progressistes. En Equateur, il a ainsi contenu l'influence grandissante d'une partie du clergé catholique qui militait en faveur de la cause indigène, incarné depuis les années 50 par Mgr Leonidas Proano, surnommé l'“évêque des Indiens”.

Le catholicisme latino-américain subit la concurrence croissante des sectes protestante.

L'engagement d'une partie du clergé en faveur des guérillas d'Amérique centrale ou de ceux qui luttent contre les latifundistes en faveur des paysans sans terres au Brésil a généré de nouvelles formes de religiosité convenant mieux aux intérêts des régimes pro-américains de la région. Il s'agit essentiellement d'églises relevant du pentecôtisme (assemblée de Dieu, Eglise de Dieu, de l'Evangile complet, Prince de la paix) ou de diverses variétés du néo-pentecôtisme (Eglise Elim, du Verbe, Club 700 de Pat Robertson ou club PTL). Ces mouvements reçoivent donc une aide importante de leur nation d'origine, les Etats-Unis, où ils sont dirigés par les anticommunistes les plus fanatiques formant l'aile droite du parti républicain.

On comprend dès lors pourquoi les oligarchies et les militaires ont favorisé ces sectes protestantes dont l'influence grandit sans cesse auprès des couches populaires les plus misérables. Leur message va dans le sens d'un désengagement vis-à-vis de la sphère publique en prônant une interprétation individualiste du christianisme, centré sur le perfectionnement de l'individu. Comme les protestants européens, ils assèchent la religion qui se réduit à un simple moralisme, fondé sur l'honnêteté, le refus de l'alcoolisme. Ce désintérêt pour le salut collectif se double d'une action efficace menée en direction des populations déshéritées à qui les protestants prodiguent des aides grâce à l'argent venu des Etats-Unis. Le soutien apporté aux victimes du tremblement de terre qui a frappé le Guatemala en 1976 s'est accompagné d'une vaste campagne de conversion, Jerry Faldwell et Pat Robertson venant évangéliser les foules dans les stades de football. La même année, l'Alliance évangélique se range du côté d'un régime qui a massacré entre 100.000 et 200.000 Indiens en prônant le respect des autorités. En 1982, c'est un chrétien conservateur de l'Eglise du Verbe, le général Rios Montt, qui accède au pouvoir à la suite d'un coup d'Etat. Avec lui, répression et massacres d'Indiens s'accentuent tandis que des hameaux stratégiques poussent comme des champignons. Bâtis sur le modèle des villages stratégiques de la guerre du Viet Nam, ces hameaux ont pour but de déstructurer les communautés indiennes afin de détruire les bases de la guérilla. Les Etats-Unis jouent un rôle actif en fournissant capitaux et experts à l'armée guatémaltèque.

Au Salvador, les militaires se servent également des évangélistes pour donner un contenu idéologique à leur action contre-révolutionnaire. Ces sectes protestantes font aussi une percée dans des pays où règne la paix. Au Brésil, ils ont supplanté les adeptes de la Théologie de la libération. Leur succès auprès des pauvres est immense car on estime qu'ils représentent près de 14% des électeurs contre seulement 2% pour les prêtres progressistes. En 1994, ils contribuent à la défaite électorale du candidat de gauche, Lula, qui est assimilé au diable. En constituant un groupe parlementaire évangélique, ils sont ainsi en mesure de négocier des aides pour leur église.

Un christianisme de plus en plus négateur de l'identité indienne

Les églises protestantes mènent aussi une politique d'éradication du «paganisme» indien avec lequel les catholiques avaient dû composer. Ce syncrétisme indien-chrétien est visible dans toutes les manifestations de la vie religieuse et dans les lieux de culte, telle l'église du village de Mixtèque s'appelant «maison du soleil» et les saints étant appelés les dieux, alors que seul le mot espagnol désigne Dieu. Les rites et les offrandes pratiqués sont d'ailleurs souvent à mi-chemin entre le sacrifice et la prière chrétienne.

Chez les Afro-Brésiliens, le catholicisme s'est transformé en une religion magique faite de croyance en des êtres surnaturels, de communication avec les âmes des défunts. Un rôle important est donné à l'interférence des saints dans la vie terrestre, le Dieu ne revêtant pas l'image du Père dominateur et puissant habituel.

Les catholiques, qui s'érigent en défenseurs des Indiens, poursuivent aussi leur vieille stratégie d'acculturation, obligeant ainsi les Amazoniens récemment convertis à adopter un mode de vie sédentaire, prélude à leur prolétarisation. Le mythe de Bartolomé de las Casas, fondateur de la pensée indigéniste, illustre l'ambiguité de ce rôle de protecteur, car, selon lui, il n'existait ni Espagnols ni Indiens, mais un seul populus christianus. La défense des Indiens se limitait donc au domaine social mais se gardait bien d'aborder le problème de l'identité.

Le monothéisme latino-américain a donc été le complément indispensable à la domination socio-politique des Indiens dont la renaissance ne pourra se réaliser que par un retour aux sources de leur religion, ce que les révolutionnaires marxistes n'ont jamais compris.

Jacques-Olivier MARTIN.

00:05 Publié dans Ethnologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : amérique latine, amérique du sud, ethnologie, anthropologie, religion, monothéisme, impérialisme, catholicisme, protestantisme, syncrétisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 11 décembre 2009

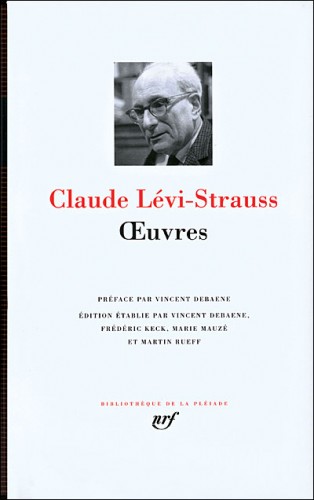

Citation de Claude Lévy-Strauss

Claude Levi-Strauss, prophète identitaire et visionnaire

|

« Les Mbaya étaient divisés en trois castes ; chacune était dominée par des préoccupations d’étiquette. Pour les nobles et jusqu’à un certain degré pour les guerriers, le problème essentiel était celui du prestige. Les descriptions anciennes nous les montrent paralysés par le souci de garder la face, de ne pas déroger et surtout de ne pas se mésallier. Une telle société se trouvait donc menacée par la ségrégation. Soit par volonté, soit par nécessité, chaque caste tendait à se replier sur elle-même aux dépens de la cohésion du corps social tout entier. En particulier, l’endogamie des castes et la multiplication des nuances de la hiérarchie devaient compromettre les possibilités d’unions conformes aux nécessités concrètes de la vie collective. Ainsi, seulement s’explique le paradoxe d’une société rétive à la procréation, qui, pour se protéger des risques de la mésalliance interne, en vient à pratiquer ce racisme à l’envers que constitue l’adoption systématique d’ennemis ou d’étrangers ».

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes tropiques, Paris : Plon, p.224. |

00:25 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : sociologie, ethnologie, anthropologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 28 novembre 2009

Lévy-Strauss fut-il un progressiste?

Lévi-Strauss fut-il un progressiste ?

Lévi-Strauss fut-il un progressiste ?

À entendre les éloges funèbres, Claude Lévi-Strauss, aujourd’hui unanimement encensé, aurait été le plus politiquement correct des philosophes : antiraciste avant l’heure, anticolonialiste, promoteur des civilisations « premières », quelle meilleure référence ?

Il est certes incontestable qu’il défendit l’idée, fondamentale dans son œuvre, que les cultures dites primitives sont aussi complexes que les cultures modernes.

À cette figure d’hagiographie, les fines bouches objectent cependant tel ou tel propos de jeunesse sur l’inégalité des races ou paraissant hostile à l’islam. Mais avant 1945 — cela est complètement oublié aujourd’hui —, dans presque toutes les familles politiques et pas seulement les pro-nazis, il était naturel de parler de race et de s’interroger sur leur éventuelle inégalité. C’est à partir de la catastrophe hitlérienne que les mentalités changèrent et encore très progressivement. Lévi-Strauss était d’ailleurs resté plutôt discret sur ces questions.

Ce n’est en tous les cas pas pour cela mais pour une toute autre raison qu’il fut considéré dans les années soixante comme un fieffé réactionnaire.

La mode du « structuralisme »

Connu seulement des spécialistes, Claude Lévi-Strauss a passé la rampe de la célébrité, au moins dans le grand public cultivé, quand fut lancée, vers 1966, la mode du « structuralisme ». Il s’agissait au départ d’une expression journalistique, comme plus tard les « nouveaux philosophes » regroupant de manière approximative des penseurs qui ne se connaissaient pratiquement pas et dont les préoccupations étaient en réalité fort différentes.

Lévi-Strauss avait tiré de la linguistique de Ferdinand de Saussure (Cours de linguistique générale, 1916) l’idée que les phénomènes humains sont organisés comme des systèmes (structures), de telle manière que si on bouge tel élément — d’une langue pour Saussure, d’un système de parenté ou de représentations mythologiques pour Lévi-Strauss (les Structures élémentaires de la parenté, 1949) —, c’est tout le système qui est affecté et pas seulement la pièce que l’on a bougée. Cela parce que les différents aspects de telle ou telle réalité humaine sont reliés par des logiques invisibles qui expliquent ce genre d’effets, dits « effets de structure » : un peu comme quand on modifie l’un des quatre angles d’un parallélépipède, les trois autres en sont automatiquement affectés.

À Saussure et Lévi-Strauss, furent rattachés le psychanalyste Jacques Lacan, qui lui aussi travaillait depuis longtemps mais n’était pas encore très connu, lequel allait répétant que « l’inconscient est structuré comme un langage », et Michel Foucault qui montra dans les Mots et les Choses (1966) comment des éléments apparemment étrangers d’une même période de la culture (son analyse du XVIIe siècle français fut exemplaire) étaient reliés par des analogies secrètes qu’on pouvait aussi qualifier de structures. Théorisant le structuralisme, Foucault dit également que l’étude de l’homme passe désormais par différents sciences humaines dont chacune construit son objet à sa manière, produisant un éclatement de la notion d’ « homme », désormais dépourvue de sens.

Il n’y eut pas d’économiste structuraliste, mais l’économie de marché fonctionne de manière si évidente selon une logique structurale que personne ne ressentit alors le besoin de le relever.

La critique marxiste

Tout cela était-il de nature à provoquer la controverse, voire la haine ? Oui, parce que les marxistes — dont on a oublié l’hégémonie idéologique au cours des années soixante, mai 68 compris, supérieure peut-être à ce qu’elle avait été au sortir de la guerre — virent dans le lancement du structuralisme un nouvel artifice inventé par la bourgeoisie pour contrer le marxisme. Pourquoi ?

Parce que le marxisme-léninisme standard reposait sur l’idée d’une infinie plasticité de la nature humaine : sinon comment prétendre sculpter l’homme nouveau du communisme ? Ce dogme avait conduit Staline à soutenir, contre toute raison, les biologistes anti-mendéliens et anti-darwiniens Mitchourine et Lyssenko. Lié à cette plasticité, le primat de l’histoire sur la structure : c’est dans un processus historique concret que l’homme se produit lui-même sans être entravé par des structures prédéterminées. Or, personne n’avait osé le dire explicitement, tant cela eut paru une grossièreté (seul, un peu plus tard, Edgar Morin s’y risqua dans le Paradigme perdu, 1973) : le structuralisme ressuscitait l’idée de quelque chose comme une nature humaine.

Pour Lévi-Strauss, il n’y avait certes pas un seul système de parenté, de type monogamique occidental (c’est en cela qu’il était « tiers mondiste ») mais tous les systèmes de parenté n’étaient pas pour autant possibles. L’humanité a dressé de manière inconsciente une sorte de tableau de Mendeleieff des systèmes de parenté et il est condamné à aller de l’un à l’autre, sans échappatoire. Même chose pour Lacan : la castration du désir œdipien primitif est une constante de l’homme, un destin originel auquel nul n’échappe. Le pessimisme de Lacan — prolongement de celui de Freud — était exprimé en termes suffisamment cryptés pour qu’un public soixante-huitard avide de nouveautés mais ne comprenant pas bien ce qu’il disait lui fasse une ovation.

Pour Lévi-Strauss, il n’y avait certes pas un seul système de parenté, de type monogamique occidental (c’est en cela qu’il était « tiers mondiste ») mais tous les systèmes de parenté n’étaient pas pour autant possibles. L’humanité a dressé de manière inconsciente une sorte de tableau de Mendeleieff des systèmes de parenté et il est condamné à aller de l’un à l’autre, sans échappatoire. Même chose pour Lacan : la castration du désir œdipien primitif est une constante de l’homme, un destin originel auquel nul n’échappe. Le pessimisme de Lacan — prolongement de celui de Freud — était exprimé en termes suffisamment cryptés pour qu’un public soixante-huitard avide de nouveautés mais ne comprenant pas bien ce qu’il disait lui fasse une ovation.

Seul Gilles Deleuze (l’Anti-Œdipe, 1972) saisit combien cette pensée pouvait être « réactionnaire » car désespérante pour toute idée de progrès. Les linguistes découvrent eux aussi des règles permanentes qui régissent l’évolution des langues. La pensée de Foucault est en revanche moins nette sur ce sujet : on n’a jamais su le statut épistémologique des concordances qu’il mettait au jour à telle ou telle époque.

Tentatives de synthèse

Tandis que les intellectuels communistes officiels se déchaînaient conte la vague structuraliste, il y eut des tentatives de synthèse entre le marxisme et le structuralisme. Un anthropologue aujourd’hui oublié, disciple de Lévi-Strauss et soigné par Lacan, Lucien Sebag, s’y essaya dans un brillant essai justement appelé Marxisme et Structuralisme (1964). Peut-être conscient d’une impasse, il se suicida l’année suivante.

Mais l’homme qui se trouva, bien malgré lui, au carrefour des deux courants de pensée fut Louis Althusser. Il était à la vérité plus marxiste que structuraliste et surtout influencé par Bachelard, mais en considérant qu’une configuration économique et sociale donnée était une réalité globale dont toutes les parties étaient solidaires, il a paru faire une lecture structuraliste du marxisme. Cela lui valut une solide méfiance du Parti communiste. Il fut en revanche le maître à penser des premiers maoïstes mais pour une tout autre raison : Althusser considérait que le mode de pensée idéologique (par opposition au mode de pensée scientifique) ne s’arrêtait pas avec la révolution mais que dans une première phase, le pouvoir « prolétarien » avait besoin d’une idéologie pour se consolider , une théorie qui justifiait à bon compte tous les délires, tant staliniens que maoïstes, à un moment où le parti communiste dénonçait au contraire le « culte de la personnalité ».

Claude Lévi-Strauss, dont le nom fut utilisé bien malgré lui dans ces querelles germanopratines, se tint largement sur la réserve. D’abord parce qu’il était souvent sur le terrain, ensuite parce que son tempérament distant et le souci de la rigueur scientifique le tenaient naturellement éloigné des tumultes de l’agora.

Source : Liberté Politique [1]

Article printed from :: Novopress Québec: http://qc.novopress.info

URL to article: http://qc.novopress.info/7116/levi-strauss-fut-il-un-progressiste/

URLs in this post:

[1] Liberté Politique: http://www.libertepolitique.com/culture-et-societe/5662-levi-strauss-fut-il-un-progressiste

00:15 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, anthropologie, ethnologie, psychologie, psychanalyse, structuralisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 24 novembre 2009

Samurai: storia, etica e mito

La società giapponese del XVI secolo aveva una struttura definibile come feudalesimo piramidale.

Al vertice di questa ideale piramide vi erano i signori dell’alta nobiltà, i daimyo, che esercitavano il loro potere tramite legami personali e familiari. Alle dirette dipendenze dei daimyo vi erano i fudai, ovvero quelle famiglie che da generazioni servivano il proprio signore. In questo contesto i samurai rappresentavano una casta familiare al servizio dei daimyo, ne erano un esercito personale.

Accadeva che durante le guerre feudali, il clan sconfitto, per non perdere le proprietà precedentemente conquistate, entrava a far parte dello stato maggiore del clan vincitore con funzioni di vassallaggio.

Accadeva che durante le guerre feudali, il clan sconfitto, per non perdere le proprietà precedentemente conquistate, entrava a far parte dello stato maggiore del clan vincitore con funzioni di vassallaggio.In questa organizzazione politica, quella militare dei samurai aveva caratteristiche e funzioni proprie al suo interno. Divisi in 17 categorie, i samurai avevano il compito di rispondere alla chiamata alle armi del daimyo cui facevano riferimento combattendo con armi proprie. Al di sotto dei samurai propriamente detti, ma facenti parte della stessa famiglia, vi erano i sotsu (“truppe di fanteria”) a loro volta divisi in 32 categorie.

Alla base della piramide troviamo gli ashigaru, cioè la maggior parte dei combattenti (soldati semplici diremmo oggi) che erano per lo più arcieri e lancieri o semplici messaggeri. Nei periodi di pace gli ashigaru svolgevano mansioni come braccianti del samurai incaricato al loro mantenimento.

L’epopea dei samurai comincia nel periodo Heian (794-1185).

L’epopea dei samurai comincia nel periodo Heian (794-1185).Alla fine del XII secolo il governo aristocratico di Taira subì una sconfitta nella guerra di Genpei cedendo il potere al clan dei Minamoto. Minamoto Yoritomo, spodestando l’imperatore, assunse di fatto il potere col titolo di shogun (capo militare) e fu lui a stabilire la supremazia della casta dei samurai, che fino a tal periodo svolgeva il ruolo di classe servitrice in armi estromessa da questioni di natura politica. Nei 400 anni a venire la or più accreditata casta guerriera avrebbe svolto un ruolo decisivo nella difesa del Giappone da tentate invasioni esterne, – come quella mongola del XIII secolo –, e nelle faide interne tra i vari feudatari (daimyo), tra le quali vanno ricordate quella del periodo Muromachi (1338-1573) in cui gli shogun Ashikaga affrontarono i daimyo, e quella del periodo Momoyama (1573-1600) in cui i grandi samurai Nobunaga (in foto) prima e il suo successore Hideyoshi dopo si batterono per sottomettere il potere dei daimyo e riunificare il paese.

La politica interna troverà stabilità al termine della battaglia di Sekigahara (1600), nella quale il feudatario Tokugawa Ieyasu, col titolo di shogun, sconfiggendo i clan rivali, assumerà pieni poteri sul paese insediando il suo “regno” nella città di Edo (odierna Tokyo) e inaugurando il periodo che da tale città prese nome (1603-1867), mentre l’imperatore rimaneva di fatto confinato nell’antica capitale Kyoto.

In questo periodo la pace fu garantita dal fatto che i daimyo giurarono fedeltà, di fatto sottomettendovisi, allo shogunato e a loro volta mantennero all’interno dei loro castelli contingenti di soldati e servi. Le conseguenze per la casta dei samurai furono immediate. Divenuta una casta chiusa e non essendoci più motivi di gerre feudali, il suo ruolo guerriero assunse sempre più toni di facciata: i duelli, in un contesto dove regnava la pace tra clan, divennero per lo più di tipo privato. Lo sfoggio di abilità guerriere e l’uso della spada (per il samurai un vero e proprio culto religioso) avveniva, in maniera sempre più frequente, soltanto per scopi cerimoniali; mentre le funzioni a cui venivano sempre più spesso preposti erano di tipo burocratico ed educativo, integrandosi sempre di più nella società civile. Un segnale della trasformazione del ruolo dei samurai è testimoniato dai rapporti che questi intrapresero con il disprezzato ceto chonin (borghesia in ascesa). Tale avvicinamento ha avuto tuttavia una grande importanza per aver “esportato” i valori della “casta del ciliegio” nella società civile fino ad oggi.

Una classe di samurai che fece la sua comparsa in questa epoca di pace fu quella dei ronin (“uomini onda” o “uomini alla deriva”). Si tratta di quei soldati rimasti senza signore perché soppresso il feudo di appartenenza; in sostanza samurai declassati.

Una classe di samurai che fece la sua comparsa in questa epoca di pace fu quella dei ronin (“uomini onda” o “uomini alla deriva”). Si tratta di quei soldati rimasti senza signore perché soppresso il feudo di appartenenza; in sostanza samurai declassati.Con la caduta dell’ultimo shogunato, vale a dire quello di Yoshinobu Tokugawa, ebbe inizio l’era Meiji (1868-1912). Fu questo un periodo di radicali riforme, note con il nome di “rinnovamento Meiji”, le quali investirono a pieno anche la struttura sociale del Sol levante: l’imperatore tornava ad essere la massima figura politica a scapito dello shogunato, lo Stato fu trasformato in senso occidentale e i feudi soppressi. La casta samurai abolita in funzione di un esercito nazionale.

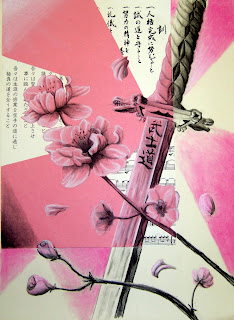

L’arte e l’onore. La morte e il ciliegio

La costante ricerca di una condotta di vita onorevole si fondeva, nell’etica della guerra del samurai, con una disciplina ferrea nell’addestramento marziale. Anche durante la pace del lungo periodo Edo, i samurai coltivarono le arti guerriere (bu-jutsu, oggi budo). Le principali discipline praticate e di giorno in giorno perfezionate erano il tiro con l’arco (kyu-jutsu, oggi kyudo), la scherma (ken-jutsu, oggi kendo) e il combattimento corpo a corpo (ju-jutsu, oggi più comunemente conosciuto come ju-jitsu).

La katana (“spada lunga”) era il principale segno di identificazione del samurai e l’acciaio della lama incarnava tutte le virtù del guerriero; ma più che questa funzione meramente riconoscitiva, la spada rappresentava un vero e proprio oggetto di culto. L’attenzione rivolta nel costruirla (sarebbe più preciso dire crearla), nel curarla e nel maneggiarla dà l’impressione che la spada venisse venerata più che utilizzata.

La katana (“spada lunga”) era il principale segno di identificazione del samurai e l’acciaio della lama incarnava tutte le virtù del guerriero; ma più che questa funzione meramente riconoscitiva, la spada rappresentava un vero e proprio oggetto di culto. L’attenzione rivolta nel costruirla (sarebbe più preciso dire crearla), nel curarla e nel maneggiarla dà l’impressione che la spada venisse venerata più che utilizzata.Trattando la figura del samurai non è possibile scindere l’allenamento fisico da quello spirituale, così come non è possibile scindere l’uomo dal soldato; tuttavia, per fini esemplificativi, potremmo dire che se il braccio era rafforzato dalla spada, lo spirito era rafforzato dalla filosofia confuciana. Fin da bambino, il futuro guerriero, veniva educato all’autodisciplina e al senso del dovere. Egli era sempre in debito con l’imperatore, con il signore e con la famiglia e il principio di restituzione di tale debito era un obbligo morale, detto giri, che accompagnava il samurai dalla culla alla tomba.

Il codice d’onore del samurai non si esauriva, tuttavia, nel principio giri, ma spaziava dal disprezzo per i beni materiali e per la paura, al rifiuto del dolore e soprattutto della morte. È proprio per la preparazione costante all’accettazione della morte che il samurai scelse come emblema di appartenenza alla propria casta il ciliegio: esso stava infatti a rappresentare la bellezza e la provvisorietà della vita: nello spettacolo della fioritura il samurai vedeva il riflesso della propria grandezza e così come il fiore di ciliegio cade dal ramo al primo soffio di vento, il guerriero doveva essere disposto a morire in qualunque momento.

Il codice d’onore del samurai non si esauriva, tuttavia, nel principio giri, ma spaziava dal disprezzo per i beni materiali e per la paura, al rifiuto del dolore e soprattutto della morte. È proprio per la preparazione costante all’accettazione della morte che il samurai scelse come emblema di appartenenza alla propria casta il ciliegio: esso stava infatti a rappresentare la bellezza e la provvisorietà della vita: nello spettacolo della fioritura il samurai vedeva il riflesso della propria grandezza e così come il fiore di ciliegio cade dal ramo al primo soffio di vento, il guerriero doveva essere disposto a morire in qualunque momento.Se morte e dolore erano i principali “crimini”, lealtà e adempimento del proprio dovere erano le principali virtù; atti di slealtà e inadempienze erano (auto)puniti con il seppuku (“suicidio rituale”, l’harakiri è molto simile, ma è un’altra cosa...).

Il codice d’onore del samurai è espresso, dal XVII secolo, nel bushido (“via del guerriero”), codice di condotta e stile di vita riassumibile nei sette princìpi seguenti:

- 義, Gi: Onestà e Giustizia

Sii scrupolosamente onesto nei rapporti con gli altri, credi nella giustizia che proviene non dalle altre persone ma da te stesso. Il vero Samurai non ha incertezze sulla questione dell’onestà e della giustizia. Vi è solo ciò che è giusto e ciò che è sbagliato.

- 勇, Yu: Eroico Coraggio

Elevati al di sopra delle masse che hanno paura di agire, nascondersi come una tartaruga nel guscio non è vivere. Un Samurai deve possedere un eroico coraggio, ciò è assolutamente rischioso e pericoloso, ciò significa vivere in modo completo, pieno, meraviglioso. L’eroico coraggio non è cieco ma intelligente e forte.

- 仁, Jin: Compassione

L’intenso addestramento rende il samurai svelto e forte. È diverso dagli altri, egli acquisisce un potere che deve essere utilizzato per il bene comune. Possiede compassione, coglie ogni opportunità di essere d’aiuto ai propri simili e se l’opportunità non si presenta egli fa di tutto per trovarne una.

- 礼, Rei: Gentile Cortesia

I Samurai non hanno motivi per comportarsi in maniera crudele, non hanno bisogno di mostrare la propria forza. Un Samurai è gentile anche con i nemici. Senza tale dimostrazione di rispetto esteriore un uomo è poco più di un animale. Il Samurai è rispettato non solo per la sua forza in battaglia ma anche per come interagisce con gli altri uomini.

- 誠, Makoto o 信, Shin: Completa Sincerità

Quando un Samurai esprime l’intenzione di compiere un’azione, questa è praticamente già compiuta, nulla gli impedirà di portare a termine l’intenzione espressa. Egli non ha bisogno né di “dare la parola” né di promettere. Parlare e agire sono la medesima cosa.

- 名誉, Meiyo: Onore

Vi è un solo giudice dell’onore del Samurai: lui stesso. Le decisioni che prendi e le azioni che ne conseguono sono un riflesso di ciò che sei in realtà. Non puoi nasconderti da te stesso.

- 忠義, Chugi: Dovere e Lealtà

Per il Samurai compiere un’azione o esprimere qualcosa equivale a diventarne proprietario. Egli ne assume la piena responsabilità, anche per ciò che ne consegue. Il Samurai è immensamente leale verso coloro di cui si prende cura. Egli resta fieramente fedele a coloro di cui è responsabile.

Per il Samurai compiere un’azione o esprimere qualcosa equivale a diventarne proprietario. Egli ne assume la piena responsabilità, anche per ciò che ne consegue. Il Samurai è immensamente leale verso coloro di cui si prende cura. Egli resta fieramente fedele a coloro di cui è responsabile.Che i Samurai, nei tanti secoli della loro storia, si siano sempre e comunque attenuti a questi princìpi, è un elemento di certo secondario, né tantomeno spetta a noi il compito di ergerci a giudici. Ciò che rimane indelebile e si manifesta in tutta la sua grandezza è invece lo spirito autentico e “romantico” di un’etica guerriera (ma non solo guerriera) fondata sul rispetto, l’onore, la lealtà, la fedeltà, il coraggio e l’abnegazione: valori che furono incarnati da molti samurai i cui nomi sono stati – a buon diritto – consegnati alla storia. E in una società che sembra aver smarrito la bussola, sempre timorosa (finanche di se stessa), l’etica samurai potrebbe rappresentare un ausilio, una salda coordinata per un recupero dell’autocoscienza e della padronanza di sé; sicuramente un ottimo strumento per il rifiuto di un’esistenza meschina ed esclusivamente materiale e per una riscoperta del proprio spirito. Lo stesso spirito che animò i “guerrieri-poeti” i quali, grazie alla lama della loro spada e al tenue turbinare dei fiori di ciliegio, seppero coniugare sapientemente Poesia e Azione.

00:10 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : japon, japonologie, éthique, philosophie, ethnologie, anthropologie, tradition, traditionalisme, extreme orient, asie, affaires asiatiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 10 novembre 2009

La mort de Claude Lévy-Strauss

La mort de Claude Lévi-Strauss

La mort de Claude Lévi-Strauss

Trouvé sur: http://rodionraskolnikov.hautetfort.com/

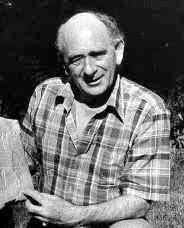

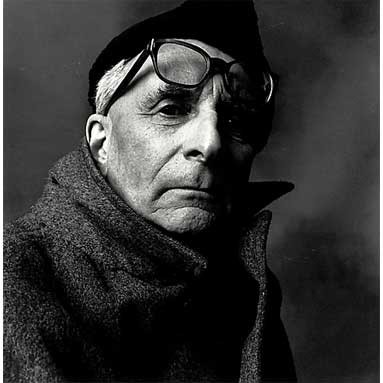

L'ethnologue Claude Lévi-Strauss est décédé en fin de semaine dernière à l'âge de 100 ans, a t-on appris mardi. Ses obsèques ont eu lieu lundi en toute intimité, à Lignerolles en Côte-d'Or. Né le 28 novembre 1908, Claude Lévi-Strauss a exercé une influence considérable sur les sciences humaines du XXè siècle. Il est notamment l'auteur de Tristes Tropiques (1955). Philosophe de formation, ce pionnier du structuralisme qui arpentait le monde pour en étudier les mythes, ce précurseur dans le domaine de l'écologie a notamment oeuvré à la réhabilitation de la pensée primitive. Voici le portrait que Pierre-Henri Tavoillot dressait du grand homme dans Le Point du 24 avril 2008 :

Jusqu'au mois d'octobre 2007, Claude Lévi-Strauss continuait à se rendre deux fois par semaine à son bureau du laboratoire d'anthropologie sociale au Collège de France. L'accès n'est pas facile ; il faut prendre un petit escalier en colimaçon. La pièce domine la bibliothèque de recherche et une large fenêtre s'ouvre sur les jeunes chercheurs qui y travaillent. Le maître les contemple et ils contemplent le maître. C'est ce "regard éloigné" et surplombant qui semble le mieux définir le grand ethnologue. L'âge n'est pas en cause, même s'il reconnaît appartenir à un autre temps : "Mon oeuvre termine une époque ; elle est encore ancrée dans le XIXe siècle". C'est surtout l'absence de toute complaisance envers son époque comme envers lui-même qui frappe chez lui : "J'ai le sentiment de n'avoir pas fait ce que j'aurais dû", avoue-t-il. Son rêve pour une vie réussie : "L'art, et surtout la musique", parce qu'"elle se suffit à elle-même" et n'a pas besoin de discours d'accompagnement. On dit que sa tétralogie sur les mythes sauvages (les quatre volumes des "Mythologiques") est composée comme un opéra ; mais "ce n'est qu'un ersatz", regrette-t-il.

Est-ce cette distance critique qui lui a permis de traverser aussi bien les époques et les modes ? Celui qui reste aujourd'hui comme le dernier monstre sacré de la grande époque structuraliste voit les hommages et les études biographiques se multiplier. La pensée de Lévi-Strauss est-elle passée dans le domaine public, s'est-elle diluée dans l'air du temps ou conserve-t-elle intacte sa puissance de séduction ?

La cause des "primitifs"

Le premier apport incontestable de Lévi-Strauss aura été de contribuer à tordre le cou à la vision ethnocentrique des civilisations telle qu'elle était encore véhiculée par la philosophie marxiste de l'histoire : les "primitifs" seraient une étape "culturellement sous-développée" de l'humanité. Aujourd'hui que la valorisation des identités et des différences culturelles est devenue un dogme, on a du mal à mesurer l'importance de cette critique. Et pourtant, sans que nous y prenions garde, le fond de cette conception n'a pas disparu, ne serait-ce que dans l'idée, spontanée, que les sociétés sauvages seraient "plus proches de la nature" que les sociétés civilisées. Que l'on perçoive l'absence de civilisation comme un défaut (idéologie du progrès) ou comme une vertu (critique de la modernité), la même idée sous-jacente est présente : les primitifs relèvent plus de la nature que de la culture. C'est contre cela que Lévi-Strauss concentre sa critique : ces sociétés ne représentent pas un stade infantile et inférieur de l'humanité-Lévy-Bruhl parlait en 1910 d'une "mentalité prélogique" -, mais des organisations complexes qui n'ont rien à envier aux nôtres en termes d'élaboration intellectuelle et culturelle. Ce sont les formes de cette culture sauvage que Lévi-Strauss va mettre au jour dans deux directions principales : l'analyse anthropologique des structures de parenté et l'analyse idéologique du récit mythologique, c'est-à-dire les faits sociaux fondamentaux et les discours collectifs qui les accompagnent.

Sociologie et idéologie des sociétés sauvages

La première entrée dans la culture sauvage s'opère par l'étude des systèmes de parenté comme base première de la reproduction sociale. Au départ de toute société et de toute culture, il y a une nomenclature des êtres sociaux classés en deux groupes : les conjoints possibles et les conjoints prohibés. L'emblème fondamental de cet ordre est la prohibition de l'inceste, comportement immuable par-delà la diversité des sociétés humaines. Lévi-Strauss y perçoit le plus petit élément culturel dans le fond naturel : "La prohibition de l'inceste, écrit-il, exprime le passage du fait naturel de la consanguinité au fait culturel de l'alliance... [...] elle est, à la fois, au seuil de la culture, dans la culture et en un sens la culture elle-même." C'est à partir de cette analyse que Lévi-Strauss construit le schéma de son maître livre : "Les structures élémentaires de la parenté" (1949).

A cette première approche de la culture sauvage viendra s'ajouter l'étude des discours mythologiques qui lui donnent sens : tel est l'objet de "La pensée sauvage" (1962), puis, à partir de 1964, des quatre volumes des "Mythologiques", pour lesquels il recueille un matériau ethnographique considérable de récits amérindiens. Là encore, Lévi-Strauss va s'attacher à mettre au jour des structures fondamentales, les "mythèmes", éléments d'une grammaire des mythes qui lui permettront d'envisager une interprétation d'ensemble. Leur fonction principale, montre-t-il, est de raconter et de mettre en scène la différence entre la nature et la culture. Ainsi va-t-il repérer comment les récits mythiques apportent l'explication de l'origine de la cuisson des aliments, opération culturelle par excellence puisqu'il s'agit de faire passer les aliments du cru au cuit (culture) en évitant la dégradation du cru au pourri (nature). Le message mythologique n'est plus du tout anecdotique ou seulement pittoresque ; il est essentiel, voire vital : la vie humaine et sociale doit se préserver de deux dangers également menaçants, celui d'une nature sans culture (où tout serait voué au pourrissement) et celui d'une culture sans nature (où les ressources se tariraient ou brûleraient du feu de la technique). Les deux excès conduiraient inexorablement à la famine et à la disparition. Le mythe raconte à la fois cette fragilité et la nécessité de maintenir cet équilibre instable : bref, une forme de vision du monde et... de sagesse.

Critiques et controverses

On comprend que cette oeuvre vaste, située au carrefour des sciences de la nature et des sciences humaines, repoussant la version sclérosée de la philosophie pour mieux en assumer les interrogations fondamentales, ait autant fasciné. On comprend aussi qu'elle ait suscité tant de contestations, qui aujourd'hui s'effacent dans l'unanimité de l'hommage. Rappelons-en pourtant les quatre principales.

Il y aurait d'abord chez lui une certaine forme de scientisme. Et, en effet, la volonté de mettre de l'exactitude dans les sciences, dites "molles", de l'homme et de la société rattache Lévi-Strauss à la tradition sociologique française qui, d'Auguste Comte à Emile Durkheim, a caressé le projet de traiter "les faits sociaux comme des choses" . Le danger pourtant est clair : à vouloir fonder l'objectivité des sciences de l'homme sur le modèle des sciences de la nature, ne court-on le risque de perdre ce qui fait la spécificité du monde humain, fait d'intentions, de choix, bref, de liberté ? Pourtant, avec le recul, Lévi-Strauss se défend de cette prétention : sans illusion sur la possibilité de parvenir à une "physique sociale", il souhaitait à l'époque "contribuer plus modestement à mettre un peu d'ordre" dans les sciences humaines et surtout à les rendre autonomes d'une philosophie idéaliste et abstraite, qu'il a toujours détestée : "La philosophie , écrivait-il dans "L'homme nu" [1971], a trop longtemps réussi à tenir les sciences humaines emprisonnées dans un cercle, en ne leur permettant d'apercevoir pour la conscience d'autre objet d'étude que la conscience elle-même [...] Ce qu'après Rousseau, Marx, Durkheim, Saussure et Freud cherche à accomplir le structuralisme, c'est dévoiler à la conscience un objet autre : donc la mettre, vis-à-vis des phénomènes humains, dans une position comparable à celle dont les sciences physiques et naturelles ont fait preuve qu'elle seule pouvait permettre à la connaissance de s'exercer."

Deuxième reproche fait à son oeuvre : l'oubli de l'Histoire. En insistant sur les structures éternelles, le structuralisme aurait contribué à dénier toute espèce d'importance à la succession des événements : "La mythologie comme la musique sont des machines à supprimer le temps" , écrivait-il dans "Le cru et le cuit" (1964). Lévi-Strauss refuse pourtant cette objection : "Rien ne me passionne davantage que l'histoire ; c'est même l'objet principal de mon activité de lecteur." En fait, ce qu'il visait alors, c'était moins l'histoire comme récit de la contingence des faits passés que la philosophie idéaliste de l'Histoire qui régnait alors, c'est-à-dire cette espèce de prophétisation de l'advenu, fondée sur ce raisonnement spécieux : il était nécessaire que cela arrivât, la preuve, c'est arrivé !

L'accusation de relativisme lui a été faite à la suite de sa conférence sur " Race et Histoire " prononcée en 1951 à la tribune de l'Unesco. On lui reprochait alors de confondre dans une même dénonciation impérialisme et universalisme et d'interdire ainsi la constitution d'un cadre juridique commun à l'humanité. Voici comment il évaluait quelques années plus tard cette prise de position : "J'ai commencé à réfléchir à un moment où notre culture agressait d'autres cultures dont je me suis alors fait le défenseur et le témoin. Maintenant, j'ai l'impression que le mouvement s'est inversé et que notre culture est sur la défensive vis-à-vis des menaces extérieures, parmi lesquelles figure probablement l'explosion islamique. Du coup je me sens fermement et ethnologiquement défenseur de ma culture" (propos recueillis par Dominique-Antoine Grisoni, "Un dictionnaire intime", in Magazine littéraire , hors-série, 2003).

Il admet en revanche la dernière critique, celle qui relève son puissant pessimisme. A ses yeux, rien n'invite à se réjouir : le spectacle de la disparition corps et biens du continent mythologique, des sociétés sauvages et de pans entiers de la culture humaine n'est guère propice à une vision euphorique du devenir humain. Pas plus que la frénésie civilisationnelle de l'homme contemporain à augmenter sa propre puissance et sa propre maîtrise. Après le crépuscule des dieux, celui des hommes serait-il venu ?

On le perçoit, à travers ces polémiques, l'oeuvre de Lévi-Strauss est riche, ample et protéiforme. Si elle a tracé son sillon sans tenir compte de l'air du temps et parfois à contre-courant, elle l'a aussi profondément influencé. Sans doute est-il encore trop tôt pour mesurer sa postérité, mais l'on peut être, à cet égard tout au moins, raisonnablement plus optimiste que son auteur.

lepoint.fr

http://www.lepoint.fr/culture/2009-11-03/la-mort-de-claud...

16:12 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : philosophie, anthropologie, lévy-strauss, ethnologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 12 septembre 2009

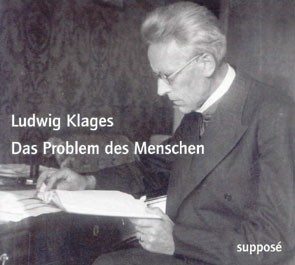

CD - Ludwig Klages: Das Problem des Menschen

CD - Ludwig Klages: Das Problem des Menschen

|

|

| Bestellungen: http://www.bublies-verlag.de/ Ludwig Klages 1. Das Problem des Menschen (1952) 15:35 2. Grundlagen der Charakterkunde (1949) 28:37

Der Lebensphilosoph Ludwig Klages (1872-1956) gehört zu den leidenschaftlichsten und zugleich umstrittensten deutschen Denkern des 20. Jahrhunderts. Als philosophische Prophetenfigur, als konservativer Revolutionär, als radikaler Vordenker der ökologischen Bewegung, aber auch als innovativer Psychologe, welcher der Charakterologie und Ausdruckskunde, insbesondere der anrüchigen Graphologie, wissenschaftliche Geltung verschaffte, hat Klages jenseits des akademischen Mainstream ein Werk von beeindruckender Vielfalt und Spannweite hinterlassen. Dieses kulminiert in dem epochalen Opus magnum "Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele". Stimmen der Kritik: "Welch schneidende, harte, barsche, kalte und trotzdem nicht dialektfreie Stimme... Gratulation zu dieser Produktion!" (Ulrich Holbein) "Die Stimme ist die Überraschung. Gestehen wir es nur, daß sie zunächst fatal an die Lehrer aus der "Feuerzangenbowle" erinnert, mit einem wahrhaft unerhörten, elementarisch gerollten "r", mit einer liebenswürdigen Unkenntnis der englischen Aussprache - Klages, 1872 geboren, kam aus einer Welt, in der das Englische noch nicht selbstverständliche Weltsprache war -, und so vernehmen wir denn die Lehre vom Gegensatz zwischen "bösiness" und Seele. Man kann diese Stimme aber auch ganz anders hören: Dann wirkt sie als Zeichen einer großen inneren Sammlung des Denkers. Sie ist eigentümlich artikuliert, melodisch und dabei ganz offensichtlich das Ergebnis eines bewußten Stilwillens. Es handelt sich hier um zwei Radiovorträge: Zusammen geben sie einen guten Einblick in die Grundideen von Klages und die Ergebnisse seiner Forschungen. Diese gingen vom "Ausdruck" aus, um einer Psychologie Paroli bieten zu können, die sich, um 1900, als Klages seine Theorie zu entwerfen begann, immer stärker an den naturwissenschaftlichen Methoden orientieren wollte. Aber auch zur älteren Physiognomik Lavaters wollte Klages nicht einfach zurückkehren. Die Erforschung des Ausdrucks sollte sich weniger auf feststehende Merkmale richten und dafür ein dynamisches Moment gewinnen, indem sie dem Rhythmus der Ausdrucksbewegungen folgte. Hier war vor allem Charles Darwin sein Vorläufer, der den Ausdruck der Gemütsbewegungen beim Tier und beim Menschen als Forschungsthema entdeckt hatte. Für solche vorbewußten, aus dem vitalen Kern stammenden Ausdrucksgestalten muß Klages ein großartiges Sensorium gehabt haben; man hat den Beweis dafür in der vielfältigen Rezeption, die er gefunden hat, und bei der das überraschende Zeugnis jenes von Sergej Eisenstein darstellt, der sich in seiner Regiearbeit immer wieder, nicht unkritisch, mit Klages' Ausdruckskunde beschäftigte. Und natürlich wäre die gesamte neuere Graphologie undenkbar ohne die Begriffe, die Klages zur Deutung der Handschrift beisteuerte. Diese waren aber keine Zufallsfunde. Hinter ihnen stand begründend eine zivilisationskritische Metaphysik, ja eine heidnische Anschauung vom Wesen des Menschen, deren Formulierung sein Lebenswerk darstellte. Klages unterschied zwischen dem Bewußtsein, dem Geist und dem Willen einerseits und der Spontaneität des Lebens auf der anderen Seite. Wenn Nietzsche in der "priesterlichen Moral" das Grundproblem entdeckt hatte, so verschärfte Klages diesen Gedanken zu einer Schuldgeschichte des Christentums, der alle zerstörerischen Wirkungen der technischen Welt aufgebürdet wurden. In der konzentriertesten, abgeklärtesten Version kann man diese Gedanken nun von ihm selbst hören." (Lorenz Jäger, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) |

00:10 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : philosophie, ludwig klages, anthropologie, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, années 20, années 30, années 40 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 09 septembre 2009

La lecture évolienne des thèses de H. F. K. Günther

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1991

Robert Steuckers:

La lecture évolienne des thèses de H.F.K. Günther:

Hans Friedrich Karl Günther (1891-1968), célèbre pour avoir publié, à partir de juillet 1922 et jusqu'en 1942, une Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes (= Raciologie du peuple allemand), qui atteindra, toutes éditions confondues, 124.000 exemplaires. Une édition abrégée, intitulée Kleine Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes (= Petite raciologie du peuple allemand), atteindra 295.000 exemplaires. Ces deux ouvrages vulgarisaient les théories raciales de l'époque, notamment les classifications des phénotypes raciaux que l'on trouvait —et que l'on trouve toujours— en Europe centrale. Plus tard, Günther s'intéressera à la religiosité des Indo-Européens, qu'il qualifiera de «pantragique» et de «réservée», qu'il définira comme dépourvue d'enthousiasme extatique (cf. H.F.K. Günther, Religiosité indo-européenne, Pardès, 1987; trad. franç. et préface de R. Steuckers; présentation de Julius Evola). Günther, comme nous l'avons mentionné ci-dessous, publiera un livre sur le déclin des sociétés hellénique et romaine, de même qu'une étude sur les impacts indo-européens/nordiques (les deux termes sont souvent synonymes chez Günther) en Asie centrale, en Iran, en Afghanistan et en Inde, incluant notamment des références aux dimensions pantragiques du bouddhisme des origines. Intérêt qui le rapproche d'Evola, auteur d'un ouvrage de référence capital sur le bouddhisme, La Doctrine de l'Eveil (cf. H.F.K. Günther, Die Nordische Rasse bei den Indogermanen Asiens, Hohe Warte, Pähl Obb., 1982; préface de Jürgen Spanuth). Pour Günther, les Celtes d'Irlande véhiculent des idéaux matriarcaux, contraires à l'«esprit nordique»; en évoquant ces idéaux, il fait preuve d'une sévérité semblable à celle d'Evola. Mais, pour Günther, cette dominante matriarcale chez les Celtes, notamment en Irlande et en Gaule, vient de la disparition progressive de la caste dominante de souche nordique, porteuse de l'esprit patriarcal. Dans sa Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes (pp. 310-313), Günther formule sa critique du matriarcat celtique: «Les mutations d'ordre racial à l'intérieur des peuples celtiques s'aperçoivent très distinctement dans l'Irlande du début du Moyen Age. Dans la saga irlandaise, dans le style ornemental de l'écriture et des images, nous observons un équilibre entre les veines nordiques et occidentales (westisch); dans certains domaines, cet équilibre rappelle l'équilibre westique/nordique de l'ère mycénienne. Il faut donc tenir pour acquis qu'en Irlande et dans le Sud-Ouest de l'Angleterre, la caste dominante nordique/celtique n'a pas été numériquement forte et a rapidement disparu. Le type d'esprit que reflète le peuple irlandais —et qui s'aperçoit dans les sagas irlandaises— est très nettement déterminé par le subsrat racial westique. Heusler a suggéré une comparaison entre la saga germanique d'Islande (produite par des éléments de race nordique) et la saga d'Irlande, influencée par le substrat racial westique. Face à la saga islandaise, que Heusler décrit comme étant "fidèle à la vie et à l'histoire du temps, très réaliste et austère", caractérisée par un style narratif viril et sûr de soi, la saga irlandaise apparaît, dans son "âme" (Seele), comme "démesurée et hyperbolique"; la saga irlandaise "conduit le discours dans le pathétique ou l'hymnique"; plus loin, Heusler remarque que "l'apparence extérieure de la personne est habituellement décrite par une abondance de mots qui suggère une certaine volupté". Heusler poursuit: "La saga irlandaise aime évoquer des faits relatifs au corps (notamment en cas de blessure), en basculant souvent dans la crudité, le médical, de façon telle que cela apparaît peu ragoûtant quand on s'en tient aux critères du goût germanique" (...). La saga chez les Irlandais nous dévoile, par opposition à l'objectivité factuelle et à la retenue de la saga islandaise, une puissance imaginative débridée, un goût pour les idées folles et des descriptions exagérées, qui, souvent, sonnent "oriental"; on croit reconnaître, dans les textes de ces sagas, un type de spiritualité dont la coloration, si l'on peut dire, vire au jaune et au rouge et non plus au vert et au bleu nordiques; ce type de spiritualité présente un degré de chaleur bien supérieur à celui dont fait montre la race nordique. Nous devons donc admettre que la race westique, auparavant dominée et soumise, est revenue au pouvoir, après la disparition des éléments raciaux nordiques momentanément dominants (...). A la dénordicisation (Entnordung), dont la conséquence a été une re-westicisation (Verwestung) de l'ancienne celticité (nordique), correspond le retour de mœurs radicalement non nordiques dans le texte des sagas irlandaises. Ce retour montre, notamment, que la race westique, à l'origine, devait être régie par le matriarcat, système qui lui est spécifique. Les mœurs matriarcales impliquent que les enfants appartiennent seulement à leur mère et que le père, en coutume et en droit, n'a aucune place comparable à celle qu'il occupe dans les sociétés régies par l'esprit nordique. La femme peut se lier à l'homme qu'elle choisit puis se séparer de lui; dans le matriarcat, il n'existait pas et n'existe pas de mariage du type que connaissent les Européens d'aujourd'hui. Seul existe un sentiment d'appartenance entre les enfants nés d'une même mère. La race nordique est patriarcale, la race westique est matriarcale. La saga irlandaise nous montre que les Celtes d'Irlande, aux débuts de l'ère médiévale, n'étaient plus que des locuteurs de langues celtiques (Zimmer), puisque dans les régions celtophones des Iles Britanniques, le matriarcat avait repoussé le patriarcat, propre des véritables Celtes de race nordique, disparus au fil des temps. Nous devons en conséquence admettre que, dans son ensemble, la race westique avait pour spécificité le matriarcat (...). Le matriarcat ne connaît pas la notion de père. La famille, si toutefois l'on peut appeler telle cette forme de socialité, est constituée par la mère et ses enfants, quel que soit le père dont ils sont issus. Ces enfants n'héritent pas d'un père, mais de leur mère ou du frère de leur mère ou d'un oncle maternel. La femme s'unit à un homme, dont elle a un ou plusieurs enfants; cette union dure plus ou moins longtemps, mais ne prend jamais des formes que connaît le mariage européen actuel, qui, lui, est un ordre, où l'homme, de droit, possède la puissance matrimoniale et paternelle. "Ces états de choses sont radicalement différents de ce que nous trouvons chez les Indo-Européens, qui, tout au début de leur histoire, ont connu la famille patrilinéaire, comme le prouve leur vocabulaire ayant trait à la parenté...". Le patriarcat postule une position de puissance claire pour l'homme en tant qu'époux et que père; ce patriarcat est présent chez tous les peuples de race nordique. Le matriarcat correspond très souvent à un grand débridement des mœurs sexuelles, du moins selon le sentiment nordique. La saga irlandaise décrit le débridement et l'impudeur surtout du sexe féminin. (...) Zimmer avance toute une série d'exemples, tendant à prouver qu'au sein des populations celtophones de souche westique dans les Iles Britanniques, on rencontrait une conception des mœurs sexuelles qui devait horrifier les ressortissants de la race nordique. La race westique a déjà d'emblée une sexualité plus accentuée, moins réservée; les structures matriarcales ont vraisemblablement contribué à dévoiler cette sexualité et à lui ôter tous freins. La confrontation entre mœurs nordiques et westiques a eu lieu récemment en Irlande, au moment de la pénétration des tribus anglo-saxonnes de race nordique; les mœurs irlandaises ont dû apparaître à ces ressortissants de la race nordique comme une abominable lubricité, comme une horreur qui méritait l'éradication. Chaque race a ses mœurs spécifiques; le patriarcat caractérise la race nordique. Il faut donc réfuter le point de vue qui veut que toutes les variantes des mœurs européennes ont connu un développement partant d'un stade originel matriarcal pour aboutir à un stade patriarcal ultérieur».

Comme Evola, mais contrairement à Klages, Schuler ou Wirth, Günther a un préjugé dévaforable à l'endroit du matriarcat. Pour Evola et Günther, le patriarcat est facteur d'ordre, de stabilité. Les deux auteurs réfutent également l'idée d'une évolution du matriarcat originel au patriarcat. Patriarcat et matriarcat représentent deux psychologies immuables, présentes depuis l'aube des temps, et en conflit permanent l'une avec l'autre.

Dans Il mito del sangue, Evola résume la classification des races européennes selon Günther et évoque tant leurs caractéristiques physiques que psychiques. En conclusion de son panorama, Evola écrit (pp. 130-131): «Du point de vue de la théorie de la race en général, Günther assume totalement l'idée de la persistence et de l'autonomie des caractères raciaux, idée plus ou moins dérivée du mendelisme. Les "races mélangées" n'existent pas pour lui. Il exclut en conséquence que du croisement de deux ou de plusieurs races naisse une race effectivement nouvelle. Le produit du croisement sera simplement un composite, dans lequel se sera conservée l'hérédité des races qui l'auront composé, à l'état plus ou moins dominant ou dominé, mais jamais porté au-delà des limites de variabilité inhérentes aux types d'origine. "Quand les races se sont entrecroisées de nombreuses fois, au point de ne plus laisser subsister aucun type pur ni de l'une race ni de l'autre, nous n'obtenons pas, même après un long laps de temps, une race mêlée. Dans un tel cas, nous avons un peuple qui présente une compénétration confuse de toutes les caractéristiques: dans un même homme, nous retrouvons la stature propre à une race particulière, unie à une forme crânienne propre à une autre race, avec la couleur de la peau d'une troisième race et la couleur des yeux d'une quatrième", et ainsi de suite, la même règle s'étendant aussi aux caractéristiques psychiques. Le croisement peut donc créer de nouvelles combinaisons, sans que l'ancienne hérédité ne disparaisse. Tout au plus, il peut se produire une sélection et une élimination: des circonstances spéciales pourraient —au sein même de la race composite— faciliter la présence et la prédominance d'un certain groupe de caractéristiques et en étouffer d'autres, tant et si bien que, finalement, de telles circonstances perdurent; il se maintient alors une combinaison spéciale relativement stable, laquelle peut faire naître l'impression d'un type nouveau. Sinon, si ces circonstances s'estompent, les autres caractéristiques, celles qui ont été étouffées, réémergent; le type apparemment nouveau se décompose et, alors, se manifestent les caractères de toutes les races qui ont donné lieu au mélange. En tous cas, toute race possède en propre un idéal bien déterminé de beauté, qui finit par être altéré par le mélange, comme sont altérés les principes éthiques qui correspondent à chaque sang. C'est sur de telles bases que Günther considère comme absurde l'idée que, par le truchement d'un mélange généralisé, on pourrait réussir, en Europe, à créer une seule et unique race européenne. A rebours de cette idée, Günther estime qu'il est impossible d'arriver à unifier racialement le peuple allemand. "La majeure partie des Allemands", dit-il, "sont non seulement issus de géniteurs de races diverses mais pures, mais sont aussi les résultats du mélange d'éléments déjà mélangés". D'un tel mélange, rien de créatif ne peut surgir».

C'est ce qui permet à Evola de dire que Günther développe, d'une certaine façon, une conception non raciste de la race. La dimension psychique, puis éthique, finit par être déterminante. Est de «bonne race», l'homme qui incarne de manière toute naturelle les principes de domination de soi. Après avoir été sévère à l'égard du bouddhisme dans Die Nordische Rasse bei den Indogermanen Asiens (op. cit., pp. 52-59), parce qu'il voyait en lui une négation de la vie, survenu à un moment où l'âme nordique des conquérants aryas établis dans le nord du sub-continent indien accusait une certaine fatigue, Günther fait l'éloge du self-control bouddhique, dans Religiosité indo-europénne (op. cit.). Evola en parle dans Il mito del sangue (p. 176-177): «Intéressante et typique est l'interprétation que donne Günther du bouddhisme. Le terme yoga, qui, en sanskrit, désigne la discipline spirituelle, est "lié au latin jugum et a, chez les Anglo-Saxons la valeur de self-control; il est apparu chez les Hellènes comme enkrateia et sophrosyne et, dans le stoïcisme, comme apatheia; chez les Romains, comme la vertu purement romaine de temperentia et de disciplina, qui se reconnaît encore dans la maxime tardive du stoïcisme romain: nihil admirari. La même valeur réapparaît ultérieurement dans la chevalerie médiévale comme mesura et en langue allemande comme diu mâsze; des héros légendaires de l'Espagne, décrits comme types nordiques, du blond Cid Campeador, on dit qu'il apparaissait comme "mesuré" (tan mesurado). Le trait nordique de l'auto-discipline, de la retenue et de la froide modération se transforme, se falsifie, à des époques plus récentes, chez les peuples indo-germaniques déjà dénordicisés, ce qui donne lieu à la pratique de la mortification des sens et de l'ascèse". L'Indo-Germain antique affirme la vie. Au concept de yoga, propre de l'Inde ancienne, dérivé de ce style tout de retenue et d'auto-discipline, propre de la race nordique, s'associe le concept d'ascèse, sous l'influence de formes pré-aryennes. Cette ascèse repose sur l'idée que par le biais d'exercices et de pratiques variées, notamment corporelles, on peut se libérer du monde et potentialiser sa volonté de manière surnaturelle. La transformation la plus notable, dans ce sens, s'est précisément opérée dans le bouddhisme, où l'impétuosité vitale nordique originelle est placée dans un milieu inadéquat, lequel, par conséquent, est ressenti comme un milieu de "douleur"; cette impétuosité, pour ainsi dire, s'introvertit, se fait instrument d'évasion et de libération de la vie, de la douleur. "A partir de la diffusion du bouddhisme, l'Etat des descendants des Arî n'a plus cessé de perdre son pouvoir. A partir de la dynastie Nanda et Mauria, c'est-à-dire au IVième siècle avant JC, apparaissent des dominateurs issus des castes inférieures; la vie éthique est alors altérée; l'élément sensualiste se développe. Pour l'Inde aryenne ou nordique, on peut donc calculer un millénaire de vie, allant plus ou moins de 1400 à 400 av. JC». Evola reproche à Günther de ne pas comprendre la valeur de l'ascèse bouddhique. Son interprétation du bouddhisme, comme affadissement d'un tonus nordique originel, a, dit Evola, des connotations naturalistes.

00:05 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, traditionalisme, evola, philosophie, raciologie, races, allemagne, italie, anthropologie, ethnologie, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 29 juin 2009

J. J. Bachofen, Il popolo licio

J. J. Bachofen, Il popolo licio |

| Prefazione a |

00:10 Publié dans archéologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : anthropologie, indo-européens, asie mineure, proche-orient, archéologie, antiquité |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 25 avril 2009

Qu'est-ce que le relativisme?

| Qu'est-ce que le relativisme? Ex: http://unitepopulaire.org/

|

| « De toutes les pathologies dont souffre notre société, le relativisme "philosophique" est certainement l’une des plus dangereuses, car son caractère diffus, sa fausse logique empreinte de scientificité et son adéquation trop parfaite avec la notion de tolérance (suprême valeur du monde post-moderne) lui procurent d’inestimables avantages sur les courants philosophiques concurrents. Si, depuis Montaigne, le relativisme a attiré de nombreux penseurs refusant l’idée selon laquelle une civilisation ou une religion ne peuvent se déclarer supérieures à toutes les autres, il est indéniable que depuis une soixantaine d’années, le paradigme relativiste a étendu son empire sur toutes les nations occidentales, abrutissant dramatiquement leurs populations désormais incapables de sauvegarder les bases mêmes et les principes primordiaux de la pensée et de la culture européenne. […]

Loin d’avoir permis la sauvegarde de la diversité culturelle, le relativisme a engendré la haine de soi (ou, par voie de conséquence, la xénophilie) et l’essor de l’individualisme radical, qui ont laminé à une vitesse extraordinaire des nations millénaires.

Aujourd’hui, le relativisme apparaît cependant davantage comme la conséquence d’une déréliction généralisée, comme un discours servant à légitimer les faiblesses d’un peuple, hier glorieux et rayonnant, et aspirant désormais à une totale retraite. »

François-Xavier Rochette, "Vaincre le relativisme ?", Rivarol, 6 mars 2009 |

00:15 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : relativisme, pensée moderne, modernité, postmodernité, sociologie, anthropologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 11 avril 2009

Pour une mise en pratique des enseignements de Castaneda

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1995

POUR UNE MISE EN PRATIQUE DES ENSEIGNEMENTS DE CASTAñEDA

Nombreux sont les lecteurs d'auteurs “traditionnels” comme Evola, Guénon et d'autres qui se demandent comment mettre en pratique cette vision du monde. Le passage du cérébral à l'acte, quel qu'il soit, s'avère difficile et délicat. Pourtant, il est indispensable pour celui qui, soucieux d'authenticité, veut réellement faire sien et incarner ce qui a été lu. Cela doit être la conséquence de toute lecture portant sur l'essentiel. Sinon celle-ci devient lettre morte, donc vaine.