Nigel Rodgers

The Complete Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece [2]

Lorenz Books, 2014

“Western civilization” is certainly not fashionable in mainstream academia these days. Nonetheless, the ancient Greek and Roman heritage remains quietly revered in the more thoughtful and earnest circles. Quite simply, virtually all of our social and political organization, to the extent these are thought out, ultimately go back to Greek forms, reflected in the invariably Greek words for them (“philosophy,” “economy,” “democracy” . . .). Those who still have that instinctive pride of being European or Western always go back to the Greeks, to find the means of being worthy of that pride.

Thus I came to the Illustrated Encyclopedia produced by Nigel Rodgers. Life is short, and lots of glossy pictures certainly do help one get the gist of something. Rodgers does not limit himself to pictures of ancient Greek art, though that of course forms the bulk. There are also photos of the sites today, to better imagine the scene, and many paintings from later epochs imagining Greek scenes, the better show Greece’s powerful influence throughout Western history. The Encyclopedia is divided into two parts: First a detailed chronological history of the Greek world, second a thematic history showing different facets of Greek life.

The ancient Greeks are more than strange beings so far as post-60s “liberal democracy” is concerned. Certainly, the Greeks had that egalitarian and individualist sensitivity that Westerners are so known for.

The ancient Greeks are more than strange beings so far as post-60s “liberal democracy” is concerned. Certainly, the Greeks had that egalitarian and individualist sensitivity that Westerners are so known for.

Many Greek cities imagined that their legendary founders had equally distributed land among all citizens. As inequality and wealth concentration gradually rose over time, advocates of redistribution would cite these founding myths. (Rising inequality and revolutionary equality seems to be a recurring cycle in human history.)

Famously, Athens and various other Greek cities were full-fledged direct democracies, a kind of regime which is otherwise astonishingly rare. This was of course limited to only full male citizens, about 10 percent of the population of this “slave state.” (Alain Soral, that eternal mauvaise langue, once noted that the closest modern state to democratic Athens was . . . the Confederate States of America.)

The Greeks were individualists too, but not in the sense that Americans are, let alone post-60s liberals. Their “kings” seem more like “chiefs,” with a highly variable personal authority, rather than absolute monarchs or oriental despots.

In all other respects, the Greeks were extremely “fash”: misogynistic, authoritarian, warring, enslaving, etc. One could say that, by the standards of the United Nations, the entire Greek adventure was one ceaseless crime against humanity.

The most proto-fascistic were of course the Spartans, that famous militaristic and communal state, often idealized, as most recently in the popular film 300. Sparta would be a model for many, cited notably by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Adolf Hitler (who called the city-state “the first Volksstaat). Seven eighths of Sparta’s population was made of helots, subjects dominated by the Spartiate full-time warriors.

The Greeks generally were enthusiastic practitioners of racial citizenship. Leftists have occasionally (rightly) pointed to the fact that the establishment of democracy in Athens was linked to the abolition of debt. But one should also know that Pericles, the ultimate democratic politician, paired his generous social reforms with a tightening of citizenship criteria to having two Athenian parents by blood. (The joining of more “progressive” redistribution with more “exclusionary” citizenship makes sense: The more discriminating one is, the more generous one can be, having limited the risk of free-riding.)

In line with this, the Greeks practiced primitive eugenics so as to improve the race. The most systematic in this respect was Sparta, where newborns with physical defects were left in the wilderness to die. By this cruel “post-natal abortion” (one can certainly imagine more human methods), the Spartans thus made individual life absolutely secondary to the well-being of the community. This is certainly in stark contrast to the maudlin cult of victimhood and personal caprice currently fashionable across the West.

Athenian democracy was also known for the systematic exclusion of women, who seemed to have had lives almost as cloistered and private as that of pious Muslims. The stark limitations on sex (arranged marriages, the death penalty for adultery) may have also contributed to the similar Greek penchant for pederasty and bisexuality. Homosexuals were not a discrete social category (how sad for anyone to make their sexual practices the center of their identity!). Homosexual relationships, in parallel to wives, were often glorified as relations of the deepest friendship and entire regiments of male lovers were organized (e.g. the Sacred Band of Thebes [3]), with the idea that by such bonds they would fight to the death.

To this day, it is not clear if we have ever matched the intellectual and moral level of the Greeks (and I do not confuse morality with sentimentality, the recognition of apparently unpleasant truths is one of the greatest markers of genuine moral courage). Considering the education, culture (plays), and politics that a large swathe of the Greek public engaged in, their IQs must have been very high indeed.

Some argue we have yet to surpass Homer in literature or Plato in philosophy. (In my opinion, our average intellectual level is clearly much lower and our educated public probably peaked in consciousness and morality between the 1840s and 1920s. Our much superior science and technology is of no import in this respect, we’ve simply acquired more means of being foolish, something which could well end in the extinction of our dear human race.)

Homer’s influence over the Greeks was like “that of the Bible and Shakespeare combined or to Hollywood plus television today” (29). (Surely another marker of our catastrophic moral and intellectual decline. Of course, in a healthy culture, audiovisual media like cinema and television would be propagating the highest values, including the epic tales of our Greek heritage, among the masses.)

Homer glorified love of honor (philotimo) and excellence (areté), a kind of individualism wholly unlike what we have come to know. This was a kind of competitive individualism in the service of the community. They did not glorify individual irresponsibility or fleeing one’s community (which, to some extent, is the American form of individualism). If the hoplite citizen-soldiers did not fight with perfect cohesion and discipline, then the city was lost.

Dominique Venner has argued [4] that Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey should again be studied and revered as the foundational “sacred texts” of European civilization. (I don’t think the Angela Merkels and the Hillary Clintons would last very long in a society educated in “love of honor” and “excellence.”)

Plato, often in the running for the greatest philosopher of all time, was an anti-democrat, arguing for the rule of an enlightened elite in the Republic and becoming only more authoritarian in his final work, the Laws. Athenian democracy’s chaos, defeat in war with Sparta, and execution of his mentor Socrates for thoughtcrime no doubt contributed to this. Karl Popper argued Plato, the founder of Western philosophy, paved the way for modern totalitarianism, including German National Socialism.

The Greek city-states were tiny by our standards: Sparta with 50,000, Athens 250,000. One can see how, in a town like Sparta, one could through daily ritual and various practices (e.g. all men eating and training together) achieve an incredible degree of social unity. (Of course, modern technology could allow us to achieve similar results today, as indeed the fascists attempted and to some extent succeeded.) Direct democracy was similarly only possible in a medium-sized city at most.

The notion of citizenship is something that we must retain from the Greeks, a notion of mutual obligation between state and citizen, of collective responsibility rather than the selfish tyranny of ethnic and plutocratic mafias. Rodgers argues that polis may be better translated as “citizen-state” rather than “city-state.” The polis sometimes had a rather deterritorialized notion of citizenship, emigrants still being citizens and in a sense accountable to the home city. This could be particularly useful in our current, globalizing age, when technology has so eliminated cultural and economic borders, and our people are so scattered and intermingled with foreigners across the globe.

The ancient Greeks are also a good benchmark for success and failure: Of repeated rises and falls before ultimate extinction, of successful unity in throwing off the yoke of the Persian Empire (with famous battles at Thermopylae and Marathon . . .), and of fratricidal warfare in the Peloponnesian War.

The sheer brutality of the ancient world, as with the past more generally, is difficult for us cosseted moderns to really grasp. Conquered cities often (though not always) faced the extermination of their men and the enslavement of their women and children (often making way for the victors’ settlers). Alexander the Great, world-conqueror and founder of a still-born Greco-Persian empire, was ruthless, with frequent preemptive murders, hostage-taking, the razing of entire cities, the crucifixion of thousands, etc. He seems the closest the Greeks have to a universalist. (Did Diogenes’ “cosmopolitanism” extend to non-Greeks?) The Greeks thought foreigners (“barbarians”) inferior, and Aristotle argued for their enslavement.

The Greeks’ downfall is of course relevant. The epic Spartans gradually declined into nothing due to infertility and, apparently, wealth inequality and female emancipation. Alexander left only a cultural mark in Asia upon natives who wholly failed to sustain the Hellenic heritage. One Indian work of astronomy noted: “Although the Yavanas [Greeks] are barbarians, the science of astronomy originated with them, for which they should be revered like gods.”

One rare trace of the Greeks in Asia is the wondrous Greco-Buddhist statues [5] created in their wake, of serene and haunting otherworldly beauty.

The Jews make a late appearance upon the scene, when the Seleucid Hellenic king Antiochus IV made a fateful faux pas in his subject state of Judea:

Not realizing that Jews were somehow different form his other Semitic subjects, Antiochus despoiled the Temple, installed a Syrian garrison and erected a temple to Olympian Zeus on the site. This was probably just part of his general Hellenizing programme. But the furious revolt that broke out, led by Judas Maccabeus the High Priest, finally drove the Seleucids from Judea for good. (241)

No comment.

There is wisdom: “Nothing in excess,” “Know thyself.”

So all that Alt Right propaganda using uplifting imagery from Greco-Roman statues and history, and films like Gladiator and 300, and so on, is both effective and completely justified.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

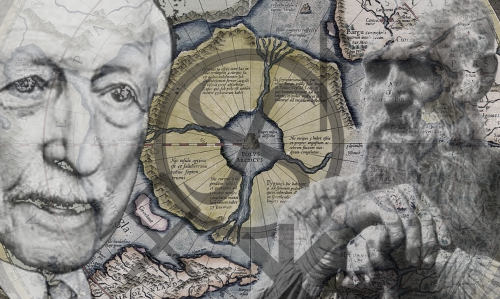

Wirth adopta cette hypothèse et construisit sa propre théorie sur elle, la « théorie hyperboréenne » [2] ou théorie du « cercle culturel de Thulé » [3], qui est le nom grec de la cité mythique se trouvant dans le pays des Hyperboréens. D’après cette théorie, avant la dernière vague de refroidissement mondial, la zone circumpolaire dans l’Océan nord-atlantique abritait des terres habitables dont les habitants furent les créateurs d’un code culturel primordial. Cette culture se forma dans des conditions où l’environnement naturel de l’Arctique n’était pas encore si inhospitalier, et où son climat était similaire au climat tempéré de l’Europe Centrale moderne. Cependant, étaient présents tous les phénomènes annuels et atmosphériques qui peuvent être observés dans l’Arctique aujourd’hui : le jour et la nuit arctiques. Les cycles solaire et lunaire annuels sont structurés différemment de leurs équivalents sous les latitudes moyennes. Ainsi, les fixations symboliques du calendrier, la trajectoire du soleil, de la lune et les constellations du zodiaque avaient forcément une forme différente et des motifs différents.

Wirth adopta cette hypothèse et construisit sa propre théorie sur elle, la « théorie hyperboréenne » [2] ou théorie du « cercle culturel de Thulé » [3], qui est le nom grec de la cité mythique se trouvant dans le pays des Hyperboréens. D’après cette théorie, avant la dernière vague de refroidissement mondial, la zone circumpolaire dans l’Océan nord-atlantique abritait des terres habitables dont les habitants furent les créateurs d’un code culturel primordial. Cette culture se forma dans des conditions où l’environnement naturel de l’Arctique n’était pas encore si inhospitalier, et où son climat était similaire au climat tempéré de l’Europe Centrale moderne. Cependant, étaient présents tous les phénomènes annuels et atmosphériques qui peuvent être observés dans l’Arctique aujourd’hui : le jour et la nuit arctiques. Les cycles solaire et lunaire annuels sont structurés différemment de leurs équivalents sous les latitudes moyennes. Ainsi, les fixations symboliques du calendrier, la trajectoire du soleil, de la lune et les constellations du zodiaque avaient forcément une forme différente et des motifs différents. Wirth présenta ainsi une vision très particulière de la relation entre le matriarcat et le patriarcat dans la culture archaïque de la région méditerranéenne. De son point de vue, les plus anciennes formes de culture en Méditerranée furent celles établies par les porteurs du matriarcat hyperboréen, qui en plusieurs étapes descendirent des régions circumpolaires, de l’Atlantique Nord, par voie de mer (et leurs navires avec des trèfles sur la poupe étaient caractéristiques). C’était le peuple mentionné dans les artefacts du Proche-Orient comme les « peuples de la mer », ou am-uru, d’où le nom ethnique des Amorrites. Le nom de Mo-uru, d’après Wirth, était jadis celui du centre principal des Hyperboréens, mais fut donné à de nouveaux centres sacrés par les natifs du Nord dans leurs vagues migratoires. C’est à ces vagues que nous devons les cultures sumérienne, akkadienne, égyptienne (dont l’écriture prédynastique était linéaire), hittite-hourrite, minoenne, mycénienne, et pélagienne. Toutes ces strates hyperboréennes étaient structurées autour de la figure de la Prêtresse Blanche.

Wirth présenta ainsi une vision très particulière de la relation entre le matriarcat et le patriarcat dans la culture archaïque de la région méditerranéenne. De son point de vue, les plus anciennes formes de culture en Méditerranée furent celles établies par les porteurs du matriarcat hyperboréen, qui en plusieurs étapes descendirent des régions circumpolaires, de l’Atlantique Nord, par voie de mer (et leurs navires avec des trèfles sur la poupe étaient caractéristiques). C’était le peuple mentionné dans les artefacts du Proche-Orient comme les « peuples de la mer », ou am-uru, d’où le nom ethnique des Amorrites. Le nom de Mo-uru, d’après Wirth, était jadis celui du centre principal des Hyperboréens, mais fut donné à de nouveaux centres sacrés par les natifs du Nord dans leurs vagues migratoires. C’est à ces vagues que nous devons les cultures sumérienne, akkadienne, égyptienne (dont l’écriture prédynastique était linéaire), hittite-hourrite, minoenne, mycénienne, et pélagienne. Toutes ces strates hyperboréennes étaient structurées autour de la figure de la Prêtresse Blanche. Entretemps se forma en Asie continentale un pôle culturel qui représentait l’embryon du proto-patriarcat. Wirth associait cette culture au naturalisme primitif, aux cultes phalliques, et à un type de culture martial, agressif et utilitaire, que Wirth considérait comme inférieur et asiatique. Nous avons consacré un volume entier à un exposé plus détaillé des idées de Wirth [7].

Entretemps se forma en Asie continentale un pôle culturel qui représentait l’embryon du proto-patriarcat. Wirth associait cette culture au naturalisme primitif, aux cultes phalliques, et à un type de culture martial, agressif et utilitaire, que Wirth considérait comme inférieur et asiatique. Nous avons consacré un volume entier à un exposé plus détaillé des idées de Wirth [7].

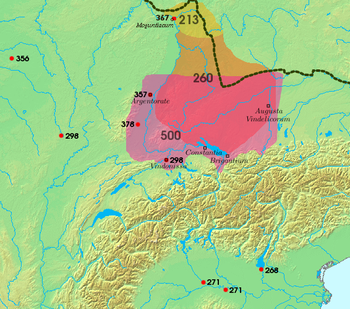

The "major military defeat" Heather refers to is not only the Battle of Strasbourg but the later Battle of Solicinium in 367 CE, in which Valentinian I defeated the Alemanni in the southwestern region of Germany. Even though he was victorious, the Alemanni were by no means broken and were still a formidable force some 80 years later when they joined the forces of

The "major military defeat" Heather refers to is not only the Battle of Strasbourg but the later Battle of Solicinium in 367 CE, in which Valentinian I defeated the Alemanni in the southwestern region of Germany. Even though he was victorious, the Alemanni were by no means broken and were still a formidable force some 80 years later when they joined the forces of

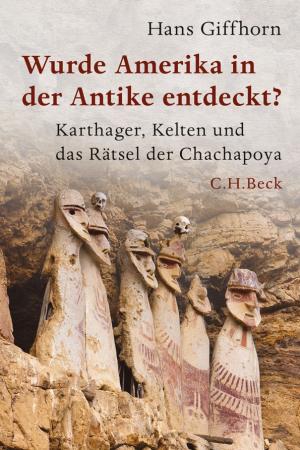

'Important if true” was the phrase that the 19th-century writer and historian Alexander Kinglake wanted to see engraved above church doors. It rings loud in the ears as one reads the latest book by

'Important if true” was the phrase that the 19th-century writer and historian Alexander Kinglake wanted to see engraved above church doors. It rings loud in the ears as one reads the latest book by

Professor Hans Giffhorn of Germany has made studying the Chachapoyan civilization his life’s work and has advanced an interesting theory regarding its origin. After many years of research starting in the 1990’s, Professor Giffhorn published a fascinating German language book in 2013 entitled

Professor Hans Giffhorn of Germany has made studying the Chachapoyan civilization his life’s work and has advanced an interesting theory regarding its origin. After many years of research starting in the 1990’s, Professor Giffhorn published a fascinating German language book in 2013 entitled

Coupled to his assertion that the Germans had no Druids, Caesar was possibly making a declaration of their apparent primitivism and lack of philosophical gods and ideals. Surely no Roman would stoop to this? Caesar had his eyes on conquest…

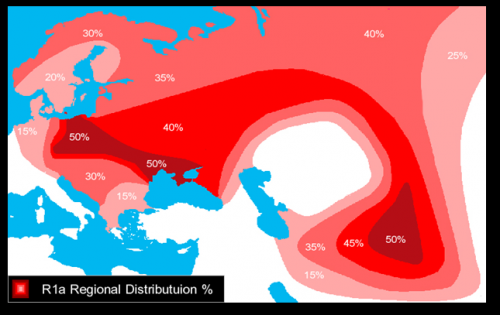

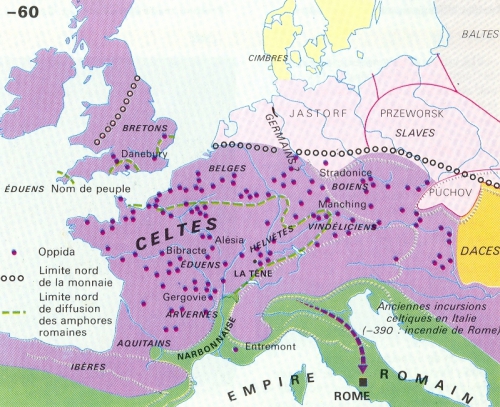

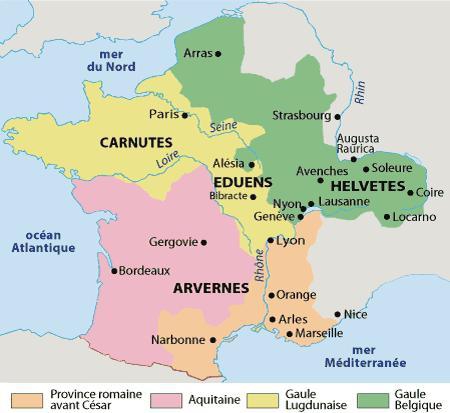

Coupled to his assertion that the Germans had no Druids, Caesar was possibly making a declaration of their apparent primitivism and lack of philosophical gods and ideals. Surely no Roman would stoop to this? Caesar had his eyes on conquest… A l’origine des Européens, il y avait un peuple préhistorique. Il n’a laissé aucune trace tangible, aucune écriture aisément reconnaissable, à part quelques symboles solaires abandonnés sur quelques pierres, depuis l’Irlande jusqu’à la Russie. Les linguistes du XIXème siècle, qui en ont découvert l’existence en comparant entre elles les langues de l’Europe moderne avec celles de plusieurs peuples d’Asie, ont appelé ce peuple les Indo-Européens car leurs héritiers ont peuplé un espace allant de l’Europe entière jusqu’à l’Iran et au nord de l’Inde.

A l’origine des Européens, il y avait un peuple préhistorique. Il n’a laissé aucune trace tangible, aucune écriture aisément reconnaissable, à part quelques symboles solaires abandonnés sur quelques pierres, depuis l’Irlande jusqu’à la Russie. Les linguistes du XIXème siècle, qui en ont découvert l’existence en comparant entre elles les langues de l’Europe moderne avec celles de plusieurs peuples d’Asie, ont appelé ce peuple les Indo-Européens car leurs héritiers ont peuplé un espace allant de l’Europe entière jusqu’à l’Iran et au nord de l’Inde. Leur religion était celle d’hommes libres. Les dieux étaient honorés autour de sanctuaires de bois, avec des « idoles » de bois pour les personnifier et servant d’objet intermédiaire pour les contacter. Tous savaient que les dieux vivaient au ciel (*akmon, un « ciel de pierre ») et pas dans des sculptures. Ils possédaient sans doute des temples de bois (*temenom) réservés aux prêtres. Les figures divines étaient aussi bien masculines que féminines, sans que les unes aient un ascendant sur les autres, à l’exception du ciel-père (*dyeus) et de la terre-mère (*dhghōm), son épouse. Le rapport entre l’homme et le dieu n’était pas celui entre un esclave et son maître, mais entre amis, même si l’un était mortel et l’autre immortel. Les dieux se mêlaient aux mortels et parfois s’unissaient à certains d’entre eux, faisant naître des héros et des protecteurs. Ils n’avaient pas besoin de créer un mot comme « laïcité » car ils l’étaient par nature.

Leur religion était celle d’hommes libres. Les dieux étaient honorés autour de sanctuaires de bois, avec des « idoles » de bois pour les personnifier et servant d’objet intermédiaire pour les contacter. Tous savaient que les dieux vivaient au ciel (*akmon, un « ciel de pierre ») et pas dans des sculptures. Ils possédaient sans doute des temples de bois (*temenom) réservés aux prêtres. Les figures divines étaient aussi bien masculines que féminines, sans que les unes aient un ascendant sur les autres, à l’exception du ciel-père (*dyeus) et de la terre-mère (*dhghōm), son épouse. Le rapport entre l’homme et le dieu n’était pas celui entre un esclave et son maître, mais entre amis, même si l’un était mortel et l’autre immortel. Les dieux se mêlaient aux mortels et parfois s’unissaient à certains d’entre eux, faisant naître des héros et des protecteurs. Ils n’avaient pas besoin de créer un mot comme « laïcité » car ils l’étaient par nature.

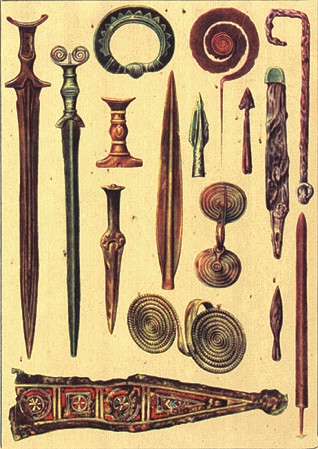

La pièce maîtresse du dépôt funéraire est un grand chaudron orné en bronze, dans lequel on mettait du vin coupé d'eau. Il pourrait avoir été réalisé par des artisans étrusques. Il contient un pichet à vin (oenochoe) en céramique attique à figures noires, fabriqué par des Grecs. Ce mobilier "atteste des échanges qui existaient entre la Méditerranée et les Celtes", souligne Dominique Garcia. La tombe date de la fin du Premier âge du Fer (période dite du Hallstatt).

La pièce maîtresse du dépôt funéraire est un grand chaudron orné en bronze, dans lequel on mettait du vin coupé d'eau. Il pourrait avoir été réalisé par des artisans étrusques. Il contient un pichet à vin (oenochoe) en céramique attique à figures noires, fabriqué par des Grecs. Ce mobilier "atteste des échanges qui existaient entre la Méditerranée et les Celtes", souligne Dominique Garcia. La tombe date de la fin du Premier âge du Fer (période dite du Hallstatt).

Les arbres seraient morts il y a plus de 4500 ans, au moment de la montée des eaux, mais auraient été préservés grâce à la constitution d'une couche de tourbe très alcaline où, privées d'oxygènes, les petites bêtes qui se chargent normalement de décomposer les arbres morts n'ont pas survécu, et donc pas pu faire disparaître ces souches. Le mythe, comme tant d'autres, est peut-être un souvenir collectif populaire laissé par la montée graduelle du niveau de la mer à la fin de la période glaciaire ; sa structure est comparable à la mythologie du Déluge comme tant d'autres que l'on retrouve dans pratiquement tous les cultures anciennes. Les restes d'une forêt ancienne engloutie à Borth, et à Sarn Badrig, près de la, peuvent avoir suggéré qu'une grande tragédie pouvait avoir emporté une ville qui se trouvait la autrefois. Il n'y a pas encore d'évidence physique solide qu'une ville substantielle existait sous la mer dans cette région.

Les arbres seraient morts il y a plus de 4500 ans, au moment de la montée des eaux, mais auraient été préservés grâce à la constitution d'une couche de tourbe très alcaline où, privées d'oxygènes, les petites bêtes qui se chargent normalement de décomposer les arbres morts n'ont pas survécu, et donc pas pu faire disparaître ces souches. Le mythe, comme tant d'autres, est peut-être un souvenir collectif populaire laissé par la montée graduelle du niveau de la mer à la fin de la période glaciaire ; sa structure est comparable à la mythologie du Déluge comme tant d'autres que l'on retrouve dans pratiquement tous les cultures anciennes. Les restes d'une forêt ancienne engloutie à Borth, et à Sarn Badrig, près de la, peuvent avoir suggéré qu'une grande tragédie pouvait avoir emporté une ville qui se trouvait la autrefois. Il n'y a pas encore d'évidence physique solide qu'une ville substantielle existait sous la mer dans cette région.

Le site archéologique de la Tournerie, à Roubion, repose désormais sous des milliers de mètres cubes de terre et les premières neiges de décembre. Mais cette chape de protection pour le moins dissuasive n'a pas suffi à contenir la rumeur qui, peu à peu, s'est emparée de la vallée de la Tinée.

Le site archéologique de la Tournerie, à Roubion, repose désormais sous des milliers de mètres cubes de terre et les premières neiges de décembre. Mais cette chape de protection pour le moins dissuasive n'a pas suffi à contenir la rumeur qui, peu à peu, s'est emparée de la vallée de la Tinée. De quoi faire sourire le président du conseil général qui a largement financé ce programme de fouilles : « Puisqu'il y avait déjà des relations avec Marseille à cette époque cela ne peut que nous inciter à les entretenir », souligne Eric Ciotti.

De quoi faire sourire le président du conseil général qui a largement financé ce programme de fouilles : « Puisqu'il y avait déjà des relations avec Marseille à cette époque cela ne peut que nous inciter à les entretenir », souligne Eric Ciotti.

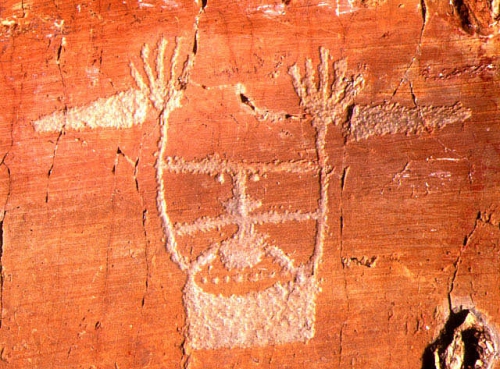

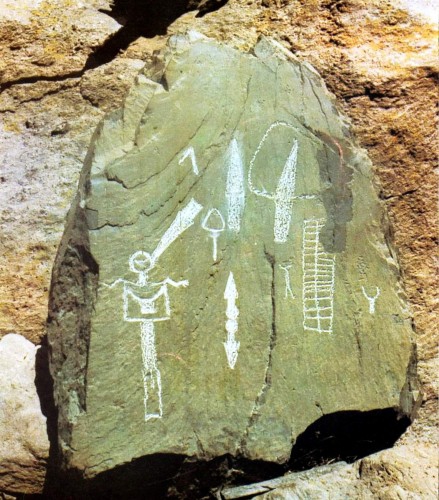

Nul hasard dans la position ou l’orientation des principales gravures et des mégalithes (qui souvent se font face ou sont placés dans des alignements significatifs) ou des objets lithiques (des outils souvent en forme d’animaux). Ces derniers découverts par Emilia Masson montrent, fait nouveau, que les gravures ne sont pas les seuls trésors légués par les anciens. Guidée par Hésiode et d’autres auteurs anciens ou inspirée par Jung, elle a su comprendre le site à l’aune des croyances d’une communauté alors bien vivante. Tous les indices recueillis montrent qu’une longue procession entrecoupée de rites avait lieu lors du solstice d’été, elle commençait à l’aube à l’est de La Cime des lacs puis se poursuivant par une longue courbe au sud, elle se finissait en fin de journée à l’ouest (flanc du Bego) sur le replat qui fait face à la Cime des lacs, suivant symboliquement la course du soleil.

Nul hasard dans la position ou l’orientation des principales gravures et des mégalithes (qui souvent se font face ou sont placés dans des alignements significatifs) ou des objets lithiques (des outils souvent en forme d’animaux). Ces derniers découverts par Emilia Masson montrent, fait nouveau, que les gravures ne sont pas les seuls trésors légués par les anciens. Guidée par Hésiode et d’autres auteurs anciens ou inspirée par Jung, elle a su comprendre le site à l’aune des croyances d’une communauté alors bien vivante. Tous les indices recueillis montrent qu’une longue procession entrecoupée de rites avait lieu lors du solstice d’été, elle commençait à l’aube à l’est de La Cime des lacs puis se poursuivant par une longue courbe au sud, elle se finissait en fin de journée à l’ouest (flanc du Bego) sur le replat qui fait face à la Cime des lacs, suivant symboliquement la course du soleil. Attirée dès sa première visite par un gigantesque visage sculpté par la nature et peut-être parachevé par l’homme, et faisant face aux trois stèles (ou plutôt le contraire), Emilia Masson fut très vite intriguée par la Cime des Lacs dont le visage occupe le flanc nord. Un constat révélateur : au solstice d’été, le soleil atteint son point zénithal au dessus du massif pyramidal au visage. Tout un ensemble d’indices conduisirent Emilia Masson à déduire l’existence d’un centre cultuel secret. Déduction bientôt confirmée en 1994 avec la découverte dans les entrailles de la Cime du lac d’une faille-grotte abritant en son fond, sur un panneau lissé par l’homme, un ensemble de gravures, certaines coloriées en ocre, notamment douze petits anneaux, ayant explicitement une signification solaire. Est découverte également une cheminée laissant penser à un chemin initiatique de retour vers la lumière. À noter que vue depuis le fond de la grotte, la portion ainsi découpé « est le point du solstice d’hiver dans le verseau » selon l’éminent paléoastronome Paul Verdier.

Attirée dès sa première visite par un gigantesque visage sculpté par la nature et peut-être parachevé par l’homme, et faisant face aux trois stèles (ou plutôt le contraire), Emilia Masson fut très vite intriguée par la Cime des Lacs dont le visage occupe le flanc nord. Un constat révélateur : au solstice d’été, le soleil atteint son point zénithal au dessus du massif pyramidal au visage. Tout un ensemble d’indices conduisirent Emilia Masson à déduire l’existence d’un centre cultuel secret. Déduction bientôt confirmée en 1994 avec la découverte dans les entrailles de la Cime du lac d’une faille-grotte abritant en son fond, sur un panneau lissé par l’homme, un ensemble de gravures, certaines coloriées en ocre, notamment douze petits anneaux, ayant explicitement une signification solaire. Est découverte également une cheminée laissant penser à un chemin initiatique de retour vers la lumière. À noter que vue depuis le fond de la grotte, la portion ainsi découpé « est le point du solstice d’hiver dans le verseau » selon l’éminent paléoastronome Paul Verdier.