Guerra y Estado

Por Sergio Prince C.

http://geviert.wordpress.com/

Schmitt comparte con Hegel algunos aspectos fundamentales de la teoría del Estado, los que resultan de suma importancia al momento de estudiar la relación de la guerra con lo político. En general, las convergencias se dan en torno a la ética del Estado y a la importancia que ambos asignan al ius publicum europaeum y se pueden apreciar entre los siguientes documentos:

a] la conferencia dictada por Schmitt en 1929, titulada en alemán Staatsethik und pluralistischer Staat [El Estado ético y el Estado pluralista] (Schmitt, 1999) que dice relación con la importancia que ambos autores asignan a la ética en el Estado y las obras de Hegel «La Filosofía del derecho» (Hegel, 2009) y «La Constitucion de Alemania» (Hegel, 1972),

b] la obra del mismo Schmitt «El nomos de la tierra» (Schmitt, 2002) , donde el autor lleva a cabo su proyecto de reconstrucción del orden juridico estatal e interestatal de la Europa Moderna y la ya citada« Filosofía del derecho» (Hegel, 2009).

En [a], la Conferencia de 1929, encontramos al menos dos coincidencias:

[1] Schmitt coincide con Hegel en el carácter ético del Estado. Dice nuestro autor:

El acto propio del Estado consiste en determinar la situación concreta, en el seno de la cual sólo puede estar en vigor, en un plano general, normas morales y jurídicas. En efecto, toda norma presupone una situación normal. No hay norma en vigoren el vacío, en una situación a – normal [con respecto a la norma]. Si el Estado «pone las condiciones exteriores de la vida ética», esto quiere decir que crea la situación normal (Kervégan, 2007, pág. 157).

En otras palabras, ambos autores estiman que el Estado es el requisito fundamental para que exista la vida ética a nivel jurídico – político y a nivel particular: la familia y la sociedad civil. Si bien es cierto que hay que buscar la raíces del Estado en estas instituciones, las dos son histórica y empíricamente posteriores a él, pues sólo la existencia del Estado permite que se diferencien dos entidades éticas sin causar la disolución de la unidad política.

[2] Otra coincidencia entre el filósofo y el jurista es que este último, haciendo uso del lenguaje hegeliano, se refiere al Estado como “el divino terrestre”, el “Reino de la razón objetiva y la eticidad”, “la unidad monista del universum” y “los problemas que conciernen al Espíritu Objetivo”. Por otra parte, Schmitt cita de modo casi idéntico ciertas fórmulas de «La Constitución de Alemania» (Hegel, 1972) donde el filósofo de Jena opone al desorden político del Imperio alemán un Estado fuerte. Para Schmitt, la situación alemana al finalizar la República de Weimar es idéntica a la vivida por Hegel con el derrumbe del Sacro Imperio Romano Germano (Kervégan, 2007).

En [b], «El Nomos de la Tierra», encontramos al menos una coincidencia:

[1] Schmitt reconoce a la FD como un monumento grandioso, como la expresión conceptual más elaborada de la forma – Estado y del derecho interestatal propio de este período de la historia. Este Estado ha actuado, al menos en el suelo europeo, como el portador del progreso en el sentido de una creciente racionalización y acotación de la guerra. Comenta Kervégan que, en el fondo, se trata de reconocer al Estado moderno “el mérito absoluto de haber asegurado la paz exterior e interior, gracias al monopolio que conquistó sobre el espacio político” (Schmitt, 2002, págs. 136-137) (Kervégan, 2007, págs. 159-160).

En resumen, hasta aquí, las coincidencias entre Schmitt y Hegel son 1] que ambos piensan en el Estado como una entidad fundamentalmente ética, 2] que ambos viven épocas similares, tiempos de desorden político que los hace pensar que la era del Estado y de la europäische Staatlichkeit [legislación europea] habían llegado a su fin y 3] ambos reconocen al Estado haber aportado a la paz. Para nuestro análisis, esto indica que, si la guerra es fundamento de lo político-jurídico, entonces es la guerra la creadora de la entidad ética fundamental, en el seno de la cual se configuran la familia y la sociedad civil como espacios éticos primordiales para la ordenación de la paz. Revisemos estas conclusiones provisorias.

Para Schmitt (Schmitt, 2006, pág. 64), la guerra es el horizonte de lo político, “es el presupuesto que está siempre dado como posibilidad real, que determina de una manera peculiar la acción y el pensamiento humanos, originando así una conducta específicamente política”. Por su parte, para Hegel la guerra es:

[1] La determinación del Estado que, por medio de la fuerza, acalla las divisiones e intereses particulares.

[2] Un medio que permite al Estado develarse y desempeñar de modo óptimo su función.

[2.1] La configuración que permite el predominio del Estado sobre la sociedad, la particularidad y la diversidad.

[2.2] La ordenación que une las esferas particulares en la unidad del Estado.

[2.3] La representación que afirma la naturaleza del Estado y del patriotismo exigiendo y obteniendo del individuo el sacrificio de lo que, en tiempos de paz, parecía constituir la esencia misma de su existencia: la familia, su propiedad, sus opiniones, su vida.

Escribe Hegel en FD §324: “Se hace un cálculo muy equivocado cuando, en la exigencia de este sacrificio, el Estado es considerado sólo como Sociedad Civil, y como su fin último es solamente tenida en cuenta la garantía de la vida y la propiedad de los individuos; puesto que esa garantía no se obtiene con el sacrificio de lo que debe ser garantido, sino al contrario.”. “De este modo, aunque la guerra trae consigo la inseguridad de la propiedad y de la existencia, es una inseguridad saludable, conectada con la vida y el movimiento. La inseguridad y la muerte son desde luego necesarias, pero en el Estado se vuelven morales al ser libremente escogidas” (Hegel, 2009, pág. 264) (Hassner, 2006):

“La guerra […], constituye el momento en el cual la idealidad de lo particular alcanza su derecho y se convierte en realidad; ella consigue su más elevado sentido en que, por su intermedio, como ya lo he explicado en otro lugar “la salud ética de los pueblos se mantiene en su equilibrio frente al fortalecimiento de las determinaciones finitas del mismo modo que el viento preserva al mar de la putrefacción, a la cual la reduciría una durable o más aún, perpetua quietud.”

Ahora bien, toda esta vitalidad ética, este dinamismo que manifiesta la guerra no se reduce a la positividad de la igualdad consigo misma sino que se realiza, se objetiva en la enemistad, ante la presencia del enemigo. Esto como resultado de la soberanía que aparece, en primer lugar, como una relación de exclusión frente al otro, al extraño. La soberanía, la independencia es un ser para sí excluyente. Veamos brevemente cuál es la tesis de Carl Schmitt sobre la enemistad. Primero, definamos antítesis amigo-enemigo y, luego, revisemos algunas características de esta.

[1] La antítesis amigo-enemigo es una categoría conceptual, concreta y existencial de lo político. Sin enemigos no hay guerra, no hay política, no hay Estado, no hay Derecho. En palabras de Kervégan, para Schmitt “el enemigo es una determinación especulativa, la figura exteriorizada de la negatividad constitutiva de la identidad consigo positiva de la vida ética.” Así, la soberanía del Estado aparece como una relación de exclusión frente a otros Estados (Kervégan, 2007, pág. 161).

A la antítesis amigo-enemigo se pueden asignar muchas características pero, siguiendo a Herrero López, destaco tres de las más relevantes para mi investigación:

[1] El Enemigo «es el otro público», es otro extranjero, algo distinto y extraño con quien se puede llegar a pelear una guerra. ¿Qué significa este otro? Resumiendo a Schmitt, responde Herrero López: Enemigo es más que el sujeto individual, se refiere a la totalidad de los hombres que luchan por su vida. El enemigo privado es aquel que sólo me afecta “a mí”. Por el contrario, el otro público es el que afecta a toda la comunidad, al pueblo en su conjunto y sólo al final me molesta personalmente.

[2] El enemigo es hostis no inimicus. Esta es la distinción que introduce Schmitt para señalar el matiz enunciado supra [1]. Para hacerla, se funda en Platón, en los evangelios de Mateo (5, 44) y Lucas (6,27) y en el diccionario de latín Forcellini Lexicon totius Latinitatis. Platón, llama guerra sólo a aquella que se lucha entre helenos y bárbaros, entre griegos y extranjeros. Por su parte, los evangelios dicen “diligite inimicos vestros” pero no dicen “diligite hostis vestros”, lo que indica a Schmitt que existe una clara distinción entre inimicus y hostis. Como ejemplo, cita la lucha entre el cristianismo y el Islam diciendo que no se puede entregar Europa por amor a los sarracenos y que sólo en el ámbito individual tiene sentido el amor al enemigo. No se puede amar a quien amenaza destruir al propio pueblo, por lo tanto, en opinión de Schmitt, la sentencia bíblica no afecta al enemigo político. Ahora bien, consultando el diccionario Forcellini, Schmitt se encuentra con la definición de hostis que versa como sigue: “Hostis is est cum quo publice Bellum habemus […] in quo ab inimico differt, qui est is, quoqum habemus privata odia.Dstingui etiam sic possunt in inimicus sit qui nos odit: hostis qui oppungat” (Herrero López, 1997).

[3] El hostis supone una enemistad pública y existencial que incluye la posibilidad extrema de su aniquilación física, de su muerte. Al concepto de enemigo y residiendo en el ámbito de lo real, corresponde la eventualidad de un combate. La guerra es el combate armado entre unidades políticas organizadas; la guerra civil es el combate armado en el interior de una unidad. Lo esencial en el concepto de “arma” es que se trata de un medio para provocar la muerte física de seres humanos. Al igual que la palabra “enemigo”, la palabra “combate” debe ser entendida aquí en su originalidad primitiva esencial. Los conceptos de amigo, enemigo y combate reciben su sentido concreto por el hecho de que se relacionan, especialmente, con la posibilidad real de la muerte física y mantienen esa relación. La guerra proviene de la enemistad puesto que ésta es la negación esencial de otro ser. La guerra es solamente la enemistad hecha real del modo más manifiesto. No tiene por qué ser algo cotidiano, algo normal; ni tampoco tiene por qué ser percibido como algo ideal o deseable. Pero debe estar presente como posibilidad real si el concepto de enemigo ha de tener significado (Schmitt, 2006).

Ya hemos dicho que Schmitt y Hegel piensan en el Estado como una entidad fundamentalmente ética creada por la guerra. Aún más, la guerra es el atributo que afirma la naturaleza del Estado exigiendo y obteniendo del individuo el sacrificio de lo que en tiempos de paz parecía constituir la esencia misma de su vida En otros términos el Estado, como espacio ético, requiere del valor militar para su consolidación y su defensa, lo que implica el enfrentar a un enemigo que tiene la intención y la posibilidad real de causarle la muerte.

Guerra, ética y Estado

Más allá de las circunstancias y los acontecimientos que provocan la guerra, esta sobrelleva una necesidad que le confiere una grandeza ética. Dice Kervégan que la guerra hace accidental y material lo que es en sí y para sí accidental y material: la vida, la libertad, la propiedad, aquello que en la paz tiene mayor valía a los ojos de los individuos-ciudadanos. La guerra es la penosa advertencia de la verdad cardinal de la ética hegeliana del Estado: la supervivencia de éste es la condición de existencia toda otra disposición ética. La guerra hace insubstancial la frivolidad y la trivialidad. La guerra, por todos los sacrificios que impone, ilustra la sumisión positiva, racional, práctica y reflexiva de lo finito a lo infinito, de lo contingente a lo necesario, de lo particular a lo universal (Kervégan, 2007).

Asimismo, “porque el sacrificio por la individualidad del Estado consiste en la relación sustancial de todos y es, por lo tanto, un deber general, al mismo tiempo como un aspecto de la idealidad, frente a la realidad de la existencia particular y le es consagrada una clase propia: el valor militar. Ahora bien, para que llege a existir esta clase, para que existan ejércitos permanentes, se deben argumentar – las razones, las consideraciones de las ventajas y las desventajas, los aspectos exteriores e interiores como los gastos con sus consecuencias, los mayores impuestos-, muy respetuosamente ante la conciencia de la Sociedad Civil. (Hegel, 2009, págs. 265-266) (§ 325-326).

Es clara la relación entre valor militar y sociedad civil. Son un devenir dialéctico de la configuración y la reconfiguración permanente del Estado ante el espectro de la guerra presente en su horizonte. Pero ¿qué es el valor militar, cuáles son sus contenidos? Escribe Hegel que el valor militar es por sí “una virtud formal, porque es la más elevada abstracción de la libertad de todos los fines, bienes, satisfacciones y vida particulares; pero esa negación existe en un modo extrínsecamente real y su manifestación como cumplimiento no es en sí misma de naturaleza espiritual: es interna disposición de ánimo, éste o aquel motivo; su resultado real no puede ser para sí, sino únicamente para los demás (Hegel, 2009, pág. 266) (§ 327). En otros términos, podemos decir que las principales características del valor militar son, al menos, cuatro. A saber, carácter axiológico, moralista, contingente y filantrópico:

[1] Carácter axiológico: Una virtud formal.

[2] Carácter moralista: Es la más elevada abstracción de la libertad

[3] Carácter contingente: No es de naturaleza espiritual

[4] Carácter filantrópico: Su resultado es para los demás

Siguiendo esta línea argumentativa, Hegel dirá que el contenido del valor militar, como disposición de ánimo, se encuentra en la Soberanía., es decir, por medio de la acción y la entrega voluntaria de la realidad personal la Soberanía es obra del fin último del valor militar. Este encierra el rigor de las cuatro grandes antítesis:

[1] entrega – libertad. La entrega misma pero como existencia de la libertad.

[2] independencia – servicio. La independencia máxima del ser por sí cuya existencia es realidad, a la vez en el mecanismo de su orden exterior y del servicio

[3] obediencia – decisión. La obediencia y el abandono total de la opinión y del razonamiento particular, por lo tanto, la ausencia de un espíritu propio; la presencia instantánea, bastante intensa y comprensiva del espíritu y de la decisión,

[4] hostilidad – bondad. El obrar más hostil y personal contra los individuos, en la disposición plenamente indiferente, más bien buena, hacia ellos en cuanto individuos.

Comenta Hegel que arriesgar la vida es algo más que sólo temer la muerte pero, por esto mismo, arriesgar la vida es mera negación y no tiene ni determinación ni valor por sí. Sólo lo positivo, el fin y el contenido de este acto proporciona a este al valor militar ya que ladrones y homicidas también arriesgan la vida con su propio fin delictuoso, lo que es un acto de coraje pero carece de sentido. Ahora bien, el valor militar ha llegado a serlo en su sentido más abstracto ya que el uso de armas de fuego, de la artillería no permite que se manifieste el valor individual, sino que permite la demostración del valor por parte de una totalidad (Hegel, 2009).

El Estado, como espacio ético, requiere del valor militar para su consolidación y su defensa, lo que implica enfrentar a un enemigo que tiene la intención y la posibilidad real de causarle la muerte. Pero arriesgar la vida es un acto valioso dependiendo del objetivo así como la definición y las características del valor militar nos muestran que este existe en una tensión dialéctica ante el horizonte siempre actualizable de la guerra que viven la familia, la Sociedad Civil y el Estado. En otros términos, el valor militar sólo cobra sentido en la objetivación del todo jurídico-político, en su relación dialéctica con la Sociedad Civil. No es una virtud fuera de esta.

Conclusión

La unidad de pensamientos entre algunos escritos de Hegel y el pensamiento de Schmitt nos da señales de una unidad intelectual entre los dos filósofos tudescos, la que nos permitió realizar nuestro estudio del Valor Militar utilizando a Schmitt como un apoyo interpretativo de lo dicho por Hegel en la Filosofía del Derecho. Ambos dan señales claras de entender una relación clara entre guerra, política y Estado. Aún más, para estos autores, la guerra es el atributo que afirma la naturaleza del Estado exigiendo y obteniendo del individuo el sacrificio de lo que en tiempos de paz parecía constituir la esencia misma de su vida. En otros términos, el Estado, como espacio ético, requiere del valor militar para su consolidación y su defensa, lo que implica enfrentar a un enemigo que tiene la intención y la posibilidad real de causarle la muerte.

El Estado, como espacio ético, requiere del valor militar para su consolidación y su defensa, lo que involucra necesariamente enfrentar a un enemigo que tiene la intención y la posibilidad real de causarle la muerte, pero arriesgar la vida es un acto valioso dependiendo del objetivo así como la definición y las características del valor militar nos muestran que este existe en una tensión dialéctica ante el horizonte siempre actualizable de la guerra que viven la familia, la Sociedad Civil y el Estado.

Como ya hemos dicho, el valor militar sólo cobra sentido en la objetivación del todo jurídico-político, en su relación dialéctica con la Sociedad Civil. No es una virtud fuera de esta. Se sigue que el valor militar es una virtud abstracta propia del estamento militar, de las Fuerzas Armadas que tienen a cargo la Defensa del Estado. Se trata de una determinación propia de un cuerpo de profesionales que se manifiesta sólo en circunstancias extraordinarias, cuando está en peligro la existencia misma del Estado. La valentía militar es necesaria pero no es de naturaleza espiritual. Sin embargo, se caracteriza por lo que podríamos llamar altas virtudes espirituales en los ámbitos axiológico, moral, contingente y filantrópico.

Finalmente, son dignas de destacar las antítesis que componen la naturaleza del valor militar. Estas podrían llamarse con toda libertad, virtudes del soldado: la entrega, el servicio, la obediencia y la bondad. Todo en una tensión dialéctica que requiere de la inteligencia para poder equilibrarlas dentro de sus opuestos y así cumplir con su objetivo: defender la Soberanía de Chile.

Trabajos Citados

Hassner, P. (2006). George W. F. Hegel [1770-1831]. En L. Strauss, & J. Cropsey, Historia de la filosofía política (págs. 689-715). México: Fondo de Cutura Económica.

Hegel, G. (2009). Filosofía del derecho (1 ed., Vol. 1). (Á. Mendoza de Montero, Trad.) Buenos Aires, Argentina: Claridad.

Hegel, G. (1972). La Constitución de Alemania (1ª ed., Vol. 1). (D. Negro Pavon, Trad.) Madrid, España: Aguilar S.A.

Herrero López, M. (1997). ElNnomos y lo político: La filosofía Política de Carl Schmitt. Navarra: EUNSA.

Kervégan, J. F. (2007). Hegel, carl Schmitt. Lo político entre especulación y posotividad. Madrid: Escolar y Mayo.

Schmitt, C. (2006). El concepto de lo político. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Schmitt, C. (2002). El nomos de la tierra en el Derecho de Gentes del Ius Publicum Europaeum (1 ed., Vol. 1). (J. L. Moreneo Pérez, Ed., & D. S. Thou, Trad.) Granada, España: Editorial Comares S.L.

Schmitt, C. (1999). Ethic of State and Pluratistic State. En C. Mouffe, & C. Mouffe (Ed.), The Challenge of Carl Schmitt (Inglesa ed., Vol. 1, págs. 195 – 208). Londres, Inglaterra: Verso.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

J’ai publié, voici quelques années, un livre que j’avais rédigé avec des amis juristes. J’avais décidé de l’appeler « Avancer vers l’État de droit ».

J’ai publié, voici quelques années, un livre que j’avais rédigé avec des amis juristes. J’avais décidé de l’appeler « Avancer vers l’État de droit ». Einer wollte den Führer führen. Nein: Einige wollten den Führer führen und wirkten so im Zeichen des Führers. Ob Heidegger, Rosenberg oder Spann, die Qualität ihrer Beiträge bleibt in diesem Kontext sekundär, wenn auch im Sinne der üblichen Vorwegnahme bei Spann die Betonung auf der philosophischen Stupidität liegen kann. Ihm gelang jedoch die Formierung eines Kreises, der mehr als sechzig Jahre nach seiner eigenen Entfernung von der Universität, der heutigen WU-Wien, das Gewäsch von Ganzheit wiederholt und daneben peinlich bemüht wirkt, keinen runden Geburtstag des Meisters oder seines ersten Schülers, manchmal auch des zweiten oder folgender, zu vergessen und zumeist mit einem Presseartikel, besser mit einem Jubiläumsband zu bedenken.

Einer wollte den Führer führen. Nein: Einige wollten den Führer führen und wirkten so im Zeichen des Führers. Ob Heidegger, Rosenberg oder Spann, die Qualität ihrer Beiträge bleibt in diesem Kontext sekundär, wenn auch im Sinne der üblichen Vorwegnahme bei Spann die Betonung auf der philosophischen Stupidität liegen kann. Ihm gelang jedoch die Formierung eines Kreises, der mehr als sechzig Jahre nach seiner eigenen Entfernung von der Universität, der heutigen WU-Wien, das Gewäsch von Ganzheit wiederholt und daneben peinlich bemüht wirkt, keinen runden Geburtstag des Meisters oder seines ersten Schülers, manchmal auch des zweiten oder folgender, zu vergessen und zumeist mit einem Presseartikel, besser mit einem Jubiläumsband zu bedenken.

Wem würde die geneigte Leserschaft die Beantwortung von Fragen zur Einschätzung historischer Abläufe gerne anvertrauen? Politikern? Solchen rechter Ausrichtung? Oder linker? Oder Geistlichen? Christlicher, muslimischer, jüdischer, hinduistischer oder anderer Herkunft? Oder Europäern? Oder lieber Asiaten oder Afrikanern? Deutschen oder Franzosen, Rumänen oder Portugiesen? Senegalesen oder Kongolesen, Marokkanern oder Südafrikanern? Palästinensern oder Israeli? Wahabbiten, Schiiten oder der Nato? China oder Russland? – Oder? Vielleicht doch eher der Sache und nur der Sache, also den Quellen verpflichteten Historikern, die offen sind für neue Befunde, polyperspektivisch und quellen- und ideologiekritisch vorgehen, also Interessen hinter Sachverhalten aufspüren und offenlegen – dem humanistischen und aufklärerischen Ethos verbundenen Wissenschaftern?

Wem würde die geneigte Leserschaft die Beantwortung von Fragen zur Einschätzung historischer Abläufe gerne anvertrauen? Politikern? Solchen rechter Ausrichtung? Oder linker? Oder Geistlichen? Christlicher, muslimischer, jüdischer, hinduistischer oder anderer Herkunft? Oder Europäern? Oder lieber Asiaten oder Afrikanern? Deutschen oder Franzosen, Rumänen oder Portugiesen? Senegalesen oder Kongolesen, Marokkanern oder Südafrikanern? Palästinensern oder Israeli? Wahabbiten, Schiiten oder der Nato? China oder Russland? – Oder? Vielleicht doch eher der Sache und nur der Sache, also den Quellen verpflichteten Historikern, die offen sind für neue Befunde, polyperspektivisch und quellen- und ideologiekritisch vorgehen, also Interessen hinter Sachverhalten aufspüren und offenlegen – dem humanistischen und aufklärerischen Ethos verbundenen Wissenschaftern? thk. Le 23 mars, Alfred de Zayas a été désigné, par le Conseil des droits de l’homme, comme expert indépendant auprès de l’ONU pour la promotion d’un ordre international démocratique et équitable. Il est le premier à avoir le droit d’assumer ce mandat créé en septembre 2011, pour pouvoir agir dans le domaine de la démocratisation de l’ONU et au sein des Etats nationaux unis en elle. Il est entré en fonction le 1er mai 2012. Déjà lors de la session d’automne 2012 du Conseil des droits de l’homme, Alfred de Zayas a présenté son premier rapport et a obtenu une large approbation. L’expert indépendant, qui présente une longue carrière à l’ONU, n’était pas venu tout à fait de manière inattendue à cette fonction, comme il le dit lui-même, car il s’est occupé depuis très longtemps de la question de l’organisation d’une vraie démocratie, c’est-à-dire de la démocratie directe, comme elle existe en Suisse. Avec son mandat, Alfred de Zayas souhaite s’engager pour la paix et l’égalité des peuples. «Horizons et débats» a interviewé Alfred de Zayas à l’ONU à Genève.

thk. Le 23 mars, Alfred de Zayas a été désigné, par le Conseil des droits de l’homme, comme expert indépendant auprès de l’ONU pour la promotion d’un ordre international démocratique et équitable. Il est le premier à avoir le droit d’assumer ce mandat créé en septembre 2011, pour pouvoir agir dans le domaine de la démocratisation de l’ONU et au sein des Etats nationaux unis en elle. Il est entré en fonction le 1er mai 2012. Déjà lors de la session d’automne 2012 du Conseil des droits de l’homme, Alfred de Zayas a présenté son premier rapport et a obtenu une large approbation. L’expert indépendant, qui présente une longue carrière à l’ONU, n’était pas venu tout à fait de manière inattendue à cette fonction, comme il le dit lui-même, car il s’est occupé depuis très longtemps de la question de l’organisation d’une vraie démocratie, c’est-à-dire de la démocratie directe, comme elle existe en Suisse. Avec son mandat, Alfred de Zayas souhaite s’engager pour la paix et l’égalité des peuples. «Horizons et débats» a interviewé Alfred de Zayas à l’ONU à Genève.  thk. Professor Dr. iur. et phil. Alfred de Zayas wurde am 23. März zum Unabhängigen Experten bei der Uno zur Förderung einer demokratischen und gleichberechtigten Weltordnung vom Menschenrechtsrat ernannt. Er ist der erste, der dieses neu geschaffene Mandat übernehmen durfte, um so im Bereich der Demokratisierung der Uno und der in ihr vereinten Nationalstaaten wirken zu können. Bereits in der Herbstsession des Uno-Menschenrechtsrates hat Alfred de Zayas seinen ersten Bericht vorgelegt und ist dabei auf grosse Zustimmung gestossen. Der Unabhängige Experte, der eine lange Karriere an der Uno aufweist, war, wie er selbst sagte, nicht ganz unerwartet zu diesem Amt gekommen, da er sich schon sehr lange mit der Frage der Ausgestaltung echter, das heisst direkter Demokratie, wie sie in der Schweiz existiert, beschäftigt hat. Mit seinem Mandat möchte sich Alfred de Zayas für den Frieden und die Gleichwertigkeit der Völker einsetzen. Zeit-Fragen hat Professor de Zayas an der Uno in Genf getroffen.

thk. Professor Dr. iur. et phil. Alfred de Zayas wurde am 23. März zum Unabhängigen Experten bei der Uno zur Förderung einer demokratischen und gleichberechtigten Weltordnung vom Menschenrechtsrat ernannt. Er ist der erste, der dieses neu geschaffene Mandat übernehmen durfte, um so im Bereich der Demokratisierung der Uno und der in ihr vereinten Nationalstaaten wirken zu können. Bereits in der Herbstsession des Uno-Menschenrechtsrates hat Alfred de Zayas seinen ersten Bericht vorgelegt und ist dabei auf grosse Zustimmung gestossen. Der Unabhängige Experte, der eine lange Karriere an der Uno aufweist, war, wie er selbst sagte, nicht ganz unerwartet zu diesem Amt gekommen, da er sich schon sehr lange mit der Frage der Ausgestaltung echter, das heisst direkter Demokratie, wie sie in der Schweiz existiert, beschäftigt hat. Mit seinem Mandat möchte sich Alfred de Zayas für den Frieden und die Gleichwertigkeit der Völker einsetzen. Zeit-Fragen hat Professor de Zayas an der Uno in Genf getroffen.

.jpg)

El artículo 2 inciso 1 de nuestra Constitución señala que “toda persona tiene derecho a la vida, a su Identidad, a su integridad moral, psíquica y física a su libre desarrollo y bienestar. El concebido es sujeto de derecho en todo cuanto le favorece” y el artículo 19 sostiene también que todos los peruanos tienen derecho “a su identidad étnica y cultural. El Estado reconoce la pluralidad étnica y cultural de la Nación”. Así pues, el derecho a la identidad tiene un lugar relevante dentro de nuestro ordenamiento jurídico, sin embargo, lo que no se dice en la constitución es que cosa debemos entender por identidad o que es lo que el derecho – o los jueces - deben entender por tal a fin de poder determinarse en que casos se podría ver afectado o no este derecho.

El artículo 2 inciso 1 de nuestra Constitución señala que “toda persona tiene derecho a la vida, a su Identidad, a su integridad moral, psíquica y física a su libre desarrollo y bienestar. El concebido es sujeto de derecho en todo cuanto le favorece” y el artículo 19 sostiene también que todos los peruanos tienen derecho “a su identidad étnica y cultural. El Estado reconoce la pluralidad étnica y cultural de la Nación”. Así pues, el derecho a la identidad tiene un lugar relevante dentro de nuestro ordenamiento jurídico, sin embargo, lo que no se dice en la constitución es que cosa debemos entender por identidad o que es lo que el derecho – o los jueces - deben entender por tal a fin de poder determinarse en que casos se podría ver afectado o no este derecho.

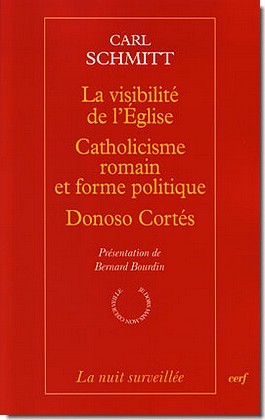

Aucun bricolage néo-kantien ne pourra longtemps masquer le nihilisme démocratique et la vacuité moderne – d’autant moins d’ailleurs que cet excellent lecteur de Kant que fut Jacobi diagnostiqua parmi les premiers la maladie nihiliste que les trois Critiques incubèrent fort peu de temps avant qu’elle ne se déclare. L’Europe, c’est-à-dire très exactement la chrétienté selon Novalis, ne pourra réagir qu’en opposant son antidote souverain : le catholicisme. On peut prendre la question dans tous les sens, ce n’est qu’en réactivant l’interrogation théologico-politique, comme l’ont compris Joseph de Maistre, Donoso Cortès, Carl Schmitt, mais aussi Leo Strauss et Jacob Taubes d’un point de vue juif, donc, en dernière analyse, chrétien, que l’on pourra faire rendre gorge au néant. L’adhésion très temporaire de Carl Schmitt au NSDAP (après d’ailleurs qu’il a mis tout Weimar en garde, dès 1932, sur le danger national-socialiste et l’urgence à interdire, par l’article 48 de la Constitution, les partis communiste et nazi) ne s’explique là encore que par la mystique au sens de Péguy – et non la politique: le catholique conséquent croyant en l’existence de l’univers invisible et donc des mauvais anges peut être abusé par les ruses et les séductions de l’Ennemi (au sens schmittien, d’une certaine façon, nous y reviendrons) jusqu’à prendre des vessies pour des lanternes et le point culminant du nihilisme actif (et non passif, celui-ci relevant de la juridiction démocratique) pour le paroxysme de la vérité. À la lettre oxymorique, il côtoie toujours les cimes des abîmes, comme un abbé Donissan ou un curé d’Ambricourt et à la différence de n’importe quel démocrate-chrétien. Les enfileurs de perles et les analystes du rien, hommes du ni oui ni non, font aujourd’hui écran au théologien politique, homme des affirmations absolues et des négations souveraines fidèle à l’Évangile («Que votre oui soit oui, que votre non soit non», Mt 5, 37) alors que ce dernier est évidemment requis par la tiédeur infernale. Le libéralisme, hostile à toute forme de vision, ne voit bien entendu se profiler aucune eschatologie à l’horizon de sa myopie : il rassemble l’alpha et l’oméga de l’Histoire – formule inadéquate quoique révélatrice de la parodie – dans l’alternance, le marché, l’hédonisme, le sentimentalisme et l’humanitarisme (ce que Schmitt appellera, non sans mépris, «la décision morale et politique dans l’ici-bas paradisiaque d’une vie immédiate, naturelle, et d’une «corporéité» sans problèmes» ou «les faits sociaux purs de toute politique»). Qui décidera de l’état d’exception en cas de guerre civile ? Le souverain, soit, personne (l’anti-personne démoniaque – en ceci, le désespoir demeure en politique une sottise absolue, puisque aussi bien le diable porte pierre).

Aucun bricolage néo-kantien ne pourra longtemps masquer le nihilisme démocratique et la vacuité moderne – d’autant moins d’ailleurs que cet excellent lecteur de Kant que fut Jacobi diagnostiqua parmi les premiers la maladie nihiliste que les trois Critiques incubèrent fort peu de temps avant qu’elle ne se déclare. L’Europe, c’est-à-dire très exactement la chrétienté selon Novalis, ne pourra réagir qu’en opposant son antidote souverain : le catholicisme. On peut prendre la question dans tous les sens, ce n’est qu’en réactivant l’interrogation théologico-politique, comme l’ont compris Joseph de Maistre, Donoso Cortès, Carl Schmitt, mais aussi Leo Strauss et Jacob Taubes d’un point de vue juif, donc, en dernière analyse, chrétien, que l’on pourra faire rendre gorge au néant. L’adhésion très temporaire de Carl Schmitt au NSDAP (après d’ailleurs qu’il a mis tout Weimar en garde, dès 1932, sur le danger national-socialiste et l’urgence à interdire, par l’article 48 de la Constitution, les partis communiste et nazi) ne s’explique là encore que par la mystique au sens de Péguy – et non la politique: le catholique conséquent croyant en l’existence de l’univers invisible et donc des mauvais anges peut être abusé par les ruses et les séductions de l’Ennemi (au sens schmittien, d’une certaine façon, nous y reviendrons) jusqu’à prendre des vessies pour des lanternes et le point culminant du nihilisme actif (et non passif, celui-ci relevant de la juridiction démocratique) pour le paroxysme de la vérité. À la lettre oxymorique, il côtoie toujours les cimes des abîmes, comme un abbé Donissan ou un curé d’Ambricourt et à la différence de n’importe quel démocrate-chrétien. Les enfileurs de perles et les analystes du rien, hommes du ni oui ni non, font aujourd’hui écran au théologien politique, homme des affirmations absolues et des négations souveraines fidèle à l’Évangile («Que votre oui soit oui, que votre non soit non», Mt 5, 37) alors que ce dernier est évidemment requis par la tiédeur infernale. Le libéralisme, hostile à toute forme de vision, ne voit bien entendu se profiler aucune eschatologie à l’horizon de sa myopie : il rassemble l’alpha et l’oméga de l’Histoire – formule inadéquate quoique révélatrice de la parodie – dans l’alternance, le marché, l’hédonisme, le sentimentalisme et l’humanitarisme (ce que Schmitt appellera, non sans mépris, «la décision morale et politique dans l’ici-bas paradisiaque d’une vie immédiate, naturelle, et d’une «corporéité» sans problèmes» ou «les faits sociaux purs de toute politique»). Qui décidera de l’état d’exception en cas de guerre civile ? Le souverain, soit, personne (l’anti-personne démoniaque – en ceci, le désespoir demeure en politique une sottise absolue, puisque aussi bien le diable porte pierre). Eine Einbürgerung kann in Deutschland künftig auch wieder rückgängig gemacht werden, wenn der eingebürgerte Ausländer die Behörden getäuscht hat. Etwa über seine kriminelle Vergangenheit. Wer den Behörden bei der Einbürgerung verschweigt, dass er ein Krimineller ist, der kann selbst dann wieder ausgebürgert werden, wenn er dadurch staatenlos wird. Geklagt hatte ein Geschäftsmann, der den Behörden bei seiner Einbürgerung in Deutschland verschwiegen hatte, dass in seinem Geburtsland Ermittlungen wegen Betruges gegen ihn liefen. Der 54-Jährige sitzt in Deutschland eine sechs Jahre währende Haftstrafe wegen Anlagebetruges ab. Vor zehn Jahren war er hier eingebürgert worden. Aber er war eben auch schon in seinem Herkunftsland kriminell in Erscheinung getreten, hatte das bei den deutschen Behörden aber nicht angegeben. Die Leipziger Richter des Bundesverwaltungsgerichts, die ihn nun mit ihrer Entscheidung zum Staatenlosen machten, entschieden sogar, ihr Vorgehen sei mit dem Europarecht vereinbar. Nach dieser Entscheidung könnten nun viele Migranten, die straffällig geworden sind und das bei ihrer Einbürgerung verschwiegen haben, wieder ausgebürgert werden.

Eine Einbürgerung kann in Deutschland künftig auch wieder rückgängig gemacht werden, wenn der eingebürgerte Ausländer die Behörden getäuscht hat. Etwa über seine kriminelle Vergangenheit. Wer den Behörden bei der Einbürgerung verschweigt, dass er ein Krimineller ist, der kann selbst dann wieder ausgebürgert werden, wenn er dadurch staatenlos wird. Geklagt hatte ein Geschäftsmann, der den Behörden bei seiner Einbürgerung in Deutschland verschwiegen hatte, dass in seinem Geburtsland Ermittlungen wegen Betruges gegen ihn liefen. Der 54-Jährige sitzt in Deutschland eine sechs Jahre währende Haftstrafe wegen Anlagebetruges ab. Vor zehn Jahren war er hier eingebürgert worden. Aber er war eben auch schon in seinem Herkunftsland kriminell in Erscheinung getreten, hatte das bei den deutschen Behörden aber nicht angegeben. Die Leipziger Richter des Bundesverwaltungsgerichts, die ihn nun mit ihrer Entscheidung zum Staatenlosen machten, entschieden sogar, ihr Vorgehen sei mit dem Europarecht vereinbar. Nach dieser Entscheidung könnten nun viele Migranten, die straffällig geworden sind und das bei ihrer Einbürgerung verschwiegen haben, wieder ausgebürgert werden.