La puissante organisation dont personne ne parle: l'OSC

Auteur : The Wealth Watchman

Ex: http://zejournal.mobi

Le réel pouvoir fondateur derrière les BRICS.

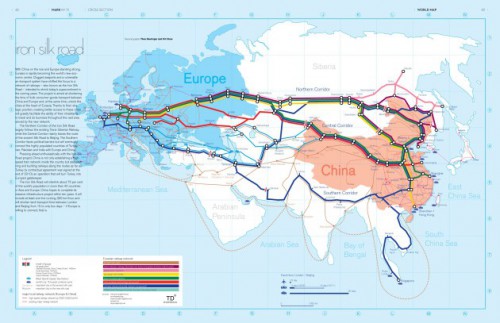

Les BRICS, comme nous l’avons déjà traité par ailleurs, ont été formés en réponse à la fraude financière et aux malversations occidentales. Son plus grand objectif est de donner à l’Orient une véritable impulsion dans des domaines comme le commerce, les mesures de sécurité et la coopération économique, le tout au sein d’un cercle qu’eux seuls, et non Washington, peuvent contrôler.

Ils ont parcouru un long chemin en un court laps de temps, c’est vrai, mais ils sont encore « les petits nouveaux du quartier ». En fait, ils ne se sont même pas conceptualisés en tant qu’idée sérieuse avant Septembre 2006 ! Leur première rencontre officielle, sans l’Afrique du Sud, n’a été tenue qu’en 2009.

Cependant, il y a une autre organisation qui est apparue avant les BRICS et qui est encore plus influente qu’eux en quelque sorte! Une organisation dont les fondateurs ont fait naître en premier l’idée ouvertement pro-marchés émergents, tout comme les BRICS.

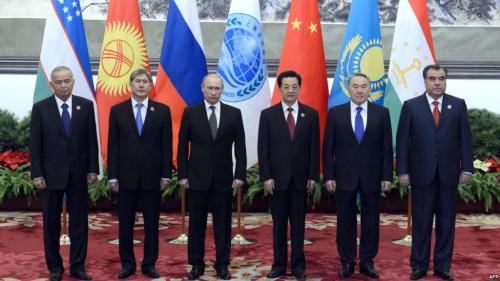

Cette organisation dont presque personne ne parle, est appelée l’ « Organisation de Coopération de Shanghai » (OCS).

Je vous avais dit que presque personne n’en parle! Laissez-moi vous présenter l’organisation la plus puissante aujourd’hui dont presque personne n’a entendu parler. Mais c’est pour bientôt!

L’histoire derrière sa fondation

Tout d’abord, l’OCS s’ést établi avant les BRICS, en fait, leurs fondations ont été posées une décennie plus tôt, en 1996. Le but de l’OCS est un peu différent de celui des BRICS, toutefois ils ont de nombreux objectifs parallèles. Tout d’abord, la création de l’OCS est l’idée d’une alliance partielle entre deux pays, la Russie et la Chine.

Pourquoi alors ont-ils été créés ?

C’est la vraie question. Afin de bien mettre nos têtes au clair sur ce sujet, faisons un rapide récapitulatif de l’histoire.

Au tout début des années 1990, lorsque l’Union Soviétique avait pratiquement perdu la guerre froide, de nombreuses garanties et traités ont été acceptés et signés, entre Gorbatchev et les États-Unis. L’un des principes directeurs était que la Russie accepte, afin de faire disparaitre pacifiquement l’Union Soviétique, que la nouvelle Allemagne Ouest et Est réunis, adhère à l’OTAN. Cependant, tout aussi important, en retour, la garantie avait été donnée au Ministre des Affaires Étrangères soviétique, Edouard Chevardnadze, que l’OTAN (une force militaire de dissuasion créée comme un contrepoids pour surveiller les forces soviétiques en Europe), n’utilise, en aucun cas, l’Allemagne pour faire un « saute mouton » et étendre sa composition plus à l’Est.

C’était un accord des plus raisonnable, et il constituait la base d’une grande paix … une paix qui aurait pu durer indéfiniment sans l’orgueil et l’arrogance de l’Ouest et des « banksters » mondialistes qui se sont hissés à sa tête. En fait, tout bêtement, le Dragon de la Banque a immédiatement commencé à revenir sur cette promesse fondamentale faite à la Russie, et a commencé à bâtir des plans pour étendre son alliance militaire de l’OTAN vers l’Est, vers le territoire russe.

La toute première admission publique faite par les mondialistes, montrant qu’ils visaient à rompre leurs promesses sur l’expansion de l’OTAN vers la Russie, fût faite par le président Clinton, en faisant un demi-tour complet en 1996. Par ailleurs, si vous vous souvenez, 1996 fût exactement l’année durant laquelle le groupe, qui deviendra l’OCS, a été formé (ce n’est pas une coïncidence).

« Wile E. Brzezinski », Kissinger, et tous les magouilleurs de l’OTAN, ont immédiatement commencé à mettre leurs promesses dans la corbeille à papier! Dans tous les sens, et aussi vers l’Est, ils ont distribué des cartes d’adhérents à l’OTAN, à tout le monde et même à leurs animaux de compagnie!

La Hongrie, la République tchèque, la Pologne et même d’anciens satellites soviétiques, comme les pays baltes, ont été admis. Plutôt que de tenir leur promesse de ne pas étendre l’OTAN, ils ont carrément doublé le nombre d’adhérents, passant de 12 à 24 États! A l’heure actuelle, ils sont 28 membres. Ils sont même allés jusqu’à mettre quelques bases navales en Asie centrale.

Le principe élémentaire des ces traités a été violé, et Washington DC s’est mit en mouvement pour encercler militairement la Russie, pour mettre des « systèmes de défense antimissile » en place autour de leurs frontières. Tout cela a été accompli au cours d’une planification de pivot vers l’Asie, et même d’un déplacement vers les républiques d’Asie centrale. Le pouvoir vacant que l’Empire Soviétique en ruine avait laissé, allait bientôt être comblé par Brzezinski et les mondialistes occidentaux.

Quelque chose devait être fait pour contenir les agressions des États-Unis et de l’OTAN, et rapidement.

L’Orient Répond

La Russie et la Chine savaient ce que signifiait l’annonce du président Clinton sur les nouvelles adhésions à l’OTAN, et se sont immédiatement mis au travail. Dans la même année, ils ont mit en place une organisation, dans la ville de Shanghai, connue sous le nom de « Shanghai Five », car il avait cinq États membres à ses débuts. Plus tard, en 2001, avec l’admission de l’Ouzbékistan, il a été rebaptisé l’Organisation de Coopération de Shanghai.

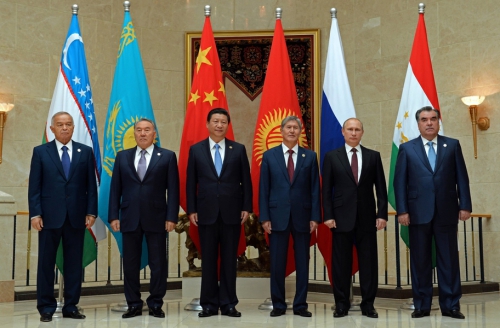

Jetons un coup d’œil à la brève description que Wikipédia lui donne dans leur introduction: L’OCS est une organisation politique, économique et militaire eurasienne qui a été fondée à Shanghai par les dirigeants de la Chine, du Kazakhstan, du Kirghizistan, de la Russie et du Tadjikistan.

Arrêtons nous là un moment. Rappelez-vous les pays que nous avons examinés et que « Wile E. Brzezinski » avait désigné dans « Le Grand Échiquier » comme clés pour contrôler l’Eurasie? Oui, il s’agissait de l’Ouzbékistan, du Tadjikistan et du Turkménistan, etc. Il semble que la Russie et la Chine avaient un accord avec M. Brzezinski, sur la question de leur importance stratégique, parce que, dès l’instant où ils ont su que les promesses de l’OTAN étaient nulles et non avenues, ils ont commencé à bouger pour fermer l’Ouest par ce couloir particulier de façon définitive.

Ses six États membres couvrent 60% de la masse continentale de l’Eurasie, sans oublier de mentionner qu’ils représentent l’énorme quart de la population mondiale!

Cependant, si vous incluez les États «observateurs», qui sont en lice pour une adhésion officielle, alors tous ceux qui sont affiliés à cette organisation comprendraient pas moins de 50% de la population mondiale!

Eh bien, bénissez-moi, si tout ceci n’avait pas été préparé de longue date! Les seules parties ignorées sont l’Asie du Sud, le Caucase, le monde arabe et l’Europe! Presque tout le monde en Asie centrale et méridionale est soit un membre, soit un «observateur» en l’état actuel des choses!

Parlons des «observateurs» …

L’adhésion à l’OCS

Une nation ne peut pas simplement décider de rejoindre l’OCS. Ce n’est pas comme cela que ça fonctionne. L’OCS soumet un candidat à un processus de «filtrage» avant de l’accepter comme nouveau membre.

La première étape pour devenir un membre, traditionnellement, est de demander le « statut d’observateur ». Ensuite les membres tiennent une série de réunions de dialogue avec le demandeur, afin de déterminer si l’application de la nation serait un ajout positif au groupe. Le test décisif pour l’adhésion semble consister à savoir si l’application de la nation répondrait à quelque chose appelé « L’esprit de Shanghai ».

Dans leurs propres mots, pour satisfaire à « L’esprit de Shanghai », une nation candidate doit remplir ces caractéristiques : la confiance mutuelle, les avantages réciproques, l’égalité, la consultation, le respect de la diversité culturelle et la poursuite du développement commun.

Si un candidat ne peut pas répondre à la plupart ou la totalité de ces choses, il ne fait pas l’affaire. Afin d’être approuvé au « statut d’observateur », chacun des six pays membres doit vous donner le feu vert. Si le Tadjikistan pense que vous seriez un préjudice pour le groupe, alors ce que pensent la Chine et la Russie n’a pas d’importance: vous ne faites pas l’affaire! Il doit y avoir un accord unanime pour qu’un nouveau membre rejoigne les rangs.

La stratégie la plus évidente pour les États-Unis et l’OTAN ne serait-elle pas tout simplement de détruire cette nouvelle organisation de l’intérieur? Pourquoi ne rejoignent-ils pas tout simplement l’OCS, afin de contrecarrer toutes ses voix?

Les États-Unis ont déjà demandé le « statut d’observateur » à l’OCS! En fait, ils ont demandé il y a près d’une décennie, en 2006, et on leur a répondu « merci, mais non merci ».

Cela devrait cimenter, dans l’esprit de chacun, à quel point ils sont retranchés contre Washington et les élites occidentales.

Une organisation militaire

Toutefois, au cas où vous seriez tentés de penser que l’OCS est juste un groupe de gars « sympathiques », qui chantent « Kumbaya », et applique de la cire sur des propos de solidarité, de coopération et de commerce, détrompez-vous! Ne l’oublions pas, l’OCS n’est pas un « tigre de papier ». D’ailleurs, l’OCS a toujours été prévu pour des questions militaires depuis le début. Après tout, il a été construit pour offrir la sécurité aux frontières de ses États membres, à la fois contre le terrorisme et contre toute tentative de placer des systèmes de missiles autour de leur périphérie. C’était une réponse directe à l’empiètement de l’OTAN vers les frontières de la Russie.

En fait, durant leur dernière réunion en Septembre, ils ont réaffirmé leur position catégorique à propos de tels comportements : « le renforcement unilatéral et illimité du système de défense antimissile par un quelconque État ou groupe d’états nuirait à la sécurité internationale et à la stabilité stratégique ».

Ils disent clairement à la fois à Washington et à l’OTAN, que de tenter de rajouter des systèmes de défense antimissile, serait considéré comme une menace directe à leur stabilité et à leur sécurité.

Mais, ils ne se sont pas contentés de simplement dire aux banquiers occidentaux de faire marche arrière, ils ont commencé à organiser certains exercices de guerre assez impressionnants. En fait, l’an dernier, ils ont tenu conjointement un exercice anti-terroriste qui a impliqué plus de 7000 soldats.

Comme vous pouvez le voir, ils ont clairement évolués du stade de « renforcement de la confiance » des premiers jours, vers une alliance militaire assurée et hautement synchronisée. Laquelle est capable de répondre rapidement aux menaces internes ou externes.

Le dernier recours des « banksters »

Cela a eu pour effet de terrifier les banksters. Après tout, leur truc habituel, depuis des siècles, a toujours été de «diviser pour régner». Ils ont été maîtres en la matière pour retourner les peuples et les nations les uns contre les autres, de sorte qu’ils puissent les manipuler et les contrôler, mais cette tactique « d’empêcher les barbares de se rassembler », à l’évidence ne fonctionne plus.

Puisque le pouvoir militaro/bancaire anglo-américain ne va sûrement pas s’en aller gentiment, ils se trouvent concrètement face à une seule option: essayer d’attirer l’un d’eux dans une guerre, avant que les concurrents arrivistes (OCS, BRICS, Eurasian Economic Alliance) ne puissent complètement se fondre ensemble. Si vous regardez tout autour, c’est exactement ce que vous verrez.

En essayant de lancer inutilement une guerre contre l’Iran (qui a le «statut d’observateur» à l’OCS), de renverser le gouvernement de l’Ukraine, et de tenter d’attirer la Russie dans une guerre dans la région du Dombass séparatiste, les États-Unis et Londres ont tenté d’entraver tout nouveau progrès de cette alliance résolument anti-dollar, anti-OTAN et anti-FMI.

Par ailleurs, en 2014, l’OCS a décidé de ne pas ajouter de nouveaux membres pour l’instant, bien qu’elle devait le faire. La raison est que l’OCS pensait que le fait que les banksters tentent d’attirer la Russie dans la guerre en Ukraine était si grave, que la majeure partie de la réunion de Septembre 2014 a porté sur l’élaboration d’un accord de paix sur cette situation.

En vérité, si vous voulez connaître les forces réelles derrière l’accord de Minsk, ne cherchez pas plus loin qu’un effort conjoint du Kremlin et l’OCS.

La tentative de mettre l’Ukraine toute entière hors des sentiers du commerce eurasien, n’a été que partiellement réussie. Après tout, l’Occident a perdu la Crimée, et à ce jour, a perdu le Dombass également. Cet échec à prendre la base navale russe de la mer noire, et à attirer la Russie dans un engagement, a fait grincer les dents de Wile E. Brzezinski et de ses marionnettistes mondialistes. Si vous ne me croyez pas, il suffit d’écouter cette interview avec le « coyote » lui-même (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrRPZ6CBvPw). Il est plus bouleversé que je ne l’ai jamais vu, et il a pourtant donné beaucoup d’interviews au cours des 6 derniers mois.

Conclusion

« Wile E. Brzezinski » et les puissants « banksters » occidentaux sont désespérés et paniqués , en regardant, impuissants, leur plus grande crainte se dérouler devant eux. Une alliance eurasienne viable est en train de devenir réalité.

Dans cette nouvelle réalité, leurs anciens mécanismes de contrôle (le prêt à intérêt et l’esclavage par la dette du FMI et de la Banque Mondiale, ainsi que les incursions de « sécurité » des États-Unis et de l’OTAN) seront à la fois importuns et sans pertinence.

Le monde ne veut plus de leurs « services » voyous. Après tout, ils peuvent subvenir à leur propre sécurité!

Le monde n’a jamais eu besoin de cette drogue dette/monnaie des banksters, et grâce à la Banque des BRICS et d’autres mécanismes, ils vont bientôt avoir tout le capital dont ils ont besoin pour s’attaquer à leurs défis, libéré du contrôle de la Banque Dragon.

Les BRICS ont un énorme pouvoir, mais ils ont toujours été l’extension économique d’une précédente alliance militaro/sécuritaire, l’OCS. Jusqu’à ce point, l’OCS a préféré que les BRICS soient le visage public de l’alternative à la domination occidentale, mais l’OCS cherche à commencer à monter sur le devant de la scène, aux côtés des BRICS.

Tout cela conduit à des conjectures concernant une information récente qui a fait l’effet d’une bombe.

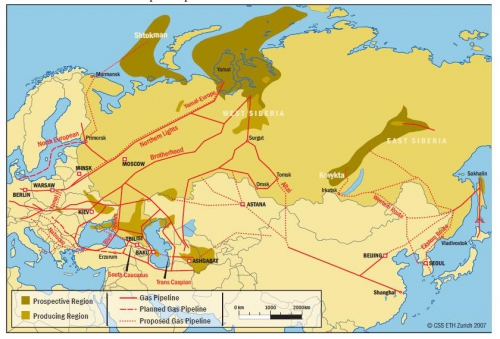

Est-ce que quelqu’un d’autre se souvient de l’annulation du South Stream, le gazoduc qui devait s’écouler à travers la Bulgarie et en Europe?

Qui est désormais le principal bénéficiaire de ce pipeline de gaz naturel à la place de l’Europe ?

La Turquie, un «observateur» de l’OCS, et (dans mon esprit) le joueur asiatique clé, pas encore totalement admis à bord. L’Eurasie ne peut pas bien fonctionner sans ce pays « passerelle » qu’est la Turquie.

L’abandon du South Stream à travers l’Europe est une énorme affaire, et cela m’amène à me demander: est-ce le prix à payer pour convaincre la Turquie (également membre-clé asiatique de l’OTAN) de changer de camp d’Ouest en Est? Seront-ils bientôt l’État surprise, qui passera de pays «observateur» de l’OCS, à membre à part entière au vote en 2015?

En outre, s’il devait rejoindre pleinement l’OCS, deviendrait-il le premier grand membre de l’OTAN … à quitter l’OTAN?

Cependant, qu’il soit inclus parmi les membres en 2015 ou non, une chose est certaine, ces nouvelles organisations de l’Eurasie sont en train de changer l’histoire si vite, que cela dépasse l’entendement. Le 21ème siècle ne ressemblera en rien à ses prédécesseurs. L’Asie (et progressivement l’Europe) semble être désireux de créer un monde nouveau, libéré des banksters « US/UK » et de leur contrôle militaire.

A quoi ressemblera la terre, une fois que tout le monde se sera rendu compte que la «nation indispensable» a toujours été complètement dispensable?

Enfin, qu’arrivera-t-il au dollar américain, et à ceux dont la richesse repose sur lui, une fois que cette nouvelle puissance mondiale sera prête à l’abandonner entièrement (comme ils le feront très certainement)?

Depuis plus d’un siècle, les banques occidentales ont volé la richesse et le destin des plus anciens, des dynasties de l’Est, et maintenant les peuples et les pouvoirs qui y sont situés, ont formé un partenariat aux dents solides pour une coopération sur leurs intérêts communs.

Désolé « Wile E. Brzezinski » et les amis mondialistes mais votre rêve de garder l’Eurasie divisée et sous votre pouce est bouleversé !

- Source : The Wealth Watchman

The closing down of the recently built factory belonging to Coca-Cola in India, located close to Varanasi in the state Uttar Pradesh, is the result of a prolonged and persistent struggle by the local residents, which has been going on for the past 11 years. The grounds for the protests were the concerns of the locals regarding the depletion and the pollution of the ground waters, due to the activities of the company, as well as the unlawful seizure of the territories belonging to local communities. As a result, the Regulatory Authorities of India refused to issue Coca-Cola a permit for the activities of the new enterprise (one of the 58 factories, located on the territory of the country) and refused to present their decision for consideration to the National Green Tribunal (NGT), which sanctioned the closure of the enterprise in the first place. India is one of the few developing countries, where the active role in supporting ecological safety belongs to the court system.

The closing down of the recently built factory belonging to Coca-Cola in India, located close to Varanasi in the state Uttar Pradesh, is the result of a prolonged and persistent struggle by the local residents, which has been going on for the past 11 years. The grounds for the protests were the concerns of the locals regarding the depletion and the pollution of the ground waters, due to the activities of the company, as well as the unlawful seizure of the territories belonging to local communities. As a result, the Regulatory Authorities of India refused to issue Coca-Cola a permit for the activities of the new enterprise (one of the 58 factories, located on the territory of the country) and refused to present their decision for consideration to the National Green Tribunal (NGT), which sanctioned the closure of the enterprise in the first place. India is one of the few developing countries, where the active role in supporting ecological safety belongs to the court system.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

One hears a great deal today about “multiculturalism,” and the multicultural society. We (i.e., we Americans) are told that ours is a multicultural society. But, curiously, multiculturalism is also spoken of as a goal. What this reveals is that multiculturalism is not simply the recognition and affirmation of the fact that the U.S.A. is made up of different people from different cultural backgrounds. Instead, multiculturalism is an ideology which is predicated on cultural relativism. Its proponents want to convince people that (a) all cultures are equally good, rich, interesting, and wholesome, and that (b) a multicultural society can exist in which no one culture is dominant. The first idea is absurd, the second is impossible.

One hears a great deal today about “multiculturalism,” and the multicultural society. We (i.e., we Americans) are told that ours is a multicultural society. But, curiously, multiculturalism is also spoken of as a goal. What this reveals is that multiculturalism is not simply the recognition and affirmation of the fact that the U.S.A. is made up of different people from different cultural backgrounds. Instead, multiculturalism is an ideology which is predicated on cultural relativism. Its proponents want to convince people that (a) all cultures are equally good, rich, interesting, and wholesome, and that (b) a multicultural society can exist in which no one culture is dominant. The first idea is absurd, the second is impossible.

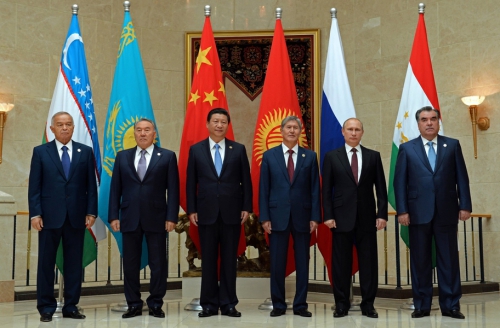

Der Gipfel der Shanghaier Organisation für Zusammenarbeit (SOZ) in der tadschikischen Hauptstadt Duschanbe hatte ein zentrales Thema: die Sanktionspolitik der USA und der EU gegen Russland wegen des Ukraine-Konflikts. Der russische Staatspräsident Wladimir Putin nutzte den Gipfel, um weitere Verbündete für eine

Der Gipfel der Shanghaier Organisation für Zusammenarbeit (SOZ) in der tadschikischen Hauptstadt Duschanbe hatte ein zentrales Thema: die Sanktionspolitik der USA und der EU gegen Russland wegen des Ukraine-Konflikts. Der russische Staatspräsident Wladimir Putin nutzte den Gipfel, um weitere Verbündete für eine

L'Inde est de retour

L'Inde est de retour

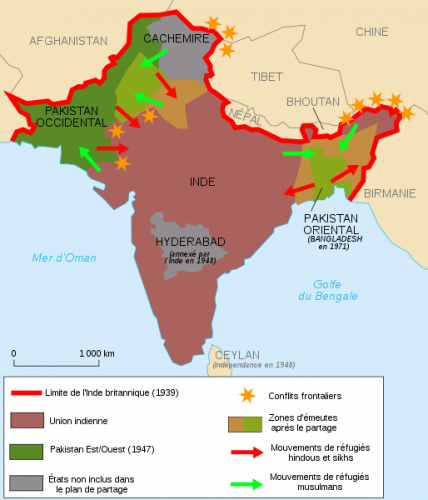

Le nouveau pouvoir indien est démocratique, mais sous surveillance des Usa car nationaliste. Mais les indiens n’en ont que faire. L’immense victoire du parti nationaliste hindou de Narendra Modi lors des législatives en Inde s'est jouée, comme prévu, sur des questions de politique intérieure et notamment celle de la relance d'une économie en berne. Mais ce succès pourrait aussi aboutir à replacer le pays sur la scène internationale. Le Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) et le futur chef du gouvernement vont d'abord concentrer leurs efforts sur une nécessaire relance de la croissance. Les relations commerciales et économiques avec les Occidentaux auront à coup sûr une incidence sur la politique que va devoir mener Narendra Modi. Avec la Chine dont l'économie est désormais quatre fois plus importante, le déficit commercial indien s'établit à 40 milliards de dollars, faute à la politique d'exportation menée par Pékin et un certain immobilisme indien.

Le nouveau pouvoir indien est démocratique, mais sous surveillance des Usa car nationaliste. Mais les indiens n’en ont que faire. L’immense victoire du parti nationaliste hindou de Narendra Modi lors des législatives en Inde s'est jouée, comme prévu, sur des questions de politique intérieure et notamment celle de la relance d'une économie en berne. Mais ce succès pourrait aussi aboutir à replacer le pays sur la scène internationale. Le Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) et le futur chef du gouvernement vont d'abord concentrer leurs efforts sur une nécessaire relance de la croissance. Les relations commerciales et économiques avec les Occidentaux auront à coup sûr une incidence sur la politique que va devoir mener Narendra Modi. Avec la Chine dont l'économie est désormais quatre fois plus importante, le déficit commercial indien s'établit à 40 milliards de dollars, faute à la politique d'exportation menée par Pékin et un certain immobilisme indien.

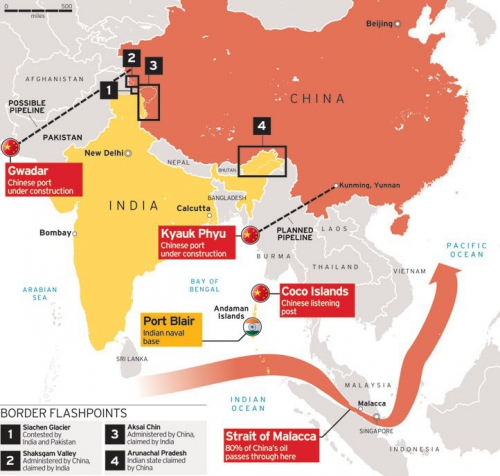

La sfida cinese lungo le frontiere deve essere analizzata chiaramente in ogni sua parte. In assenza di un confine ben definito, una delle sfide consiste nel garantire che la zona contestata della LAC non si ampli a causa dell’abilità logistica della Cina nel perseguire un atteggiamento attivista di perlustrazione in tempo di pace. Questo può essere affrontato solo, come già accennato, concentrando l’attenzione sulla logistica e sulle capacità di monitoraggio, insieme a un approccio dinamico alla gestione delle frontiere. Inoltre, dato che l’India possiede un territorio più basso, deve anche fare leva sulle misure di confidence-building (CBM) e intanto negoziare nuove norme per vincolare le capacità superiori della Cina in termini di flessibilità e pattugliamento. Se sfruttate prudentemente, le CBM possono aiutare nel mantenimento di uno status quo stabile.

La sfida cinese lungo le frontiere deve essere analizzata chiaramente in ogni sua parte. In assenza di un confine ben definito, una delle sfide consiste nel garantire che la zona contestata della LAC non si ampli a causa dell’abilità logistica della Cina nel perseguire un atteggiamento attivista di perlustrazione in tempo di pace. Questo può essere affrontato solo, come già accennato, concentrando l’attenzione sulla logistica e sulle capacità di monitoraggio, insieme a un approccio dinamico alla gestione delle frontiere. Inoltre, dato che l’India possiede un territorio più basso, deve anche fare leva sulle misure di confidence-building (CBM) e intanto negoziare nuove norme per vincolare le capacità superiori della Cina in termini di flessibilità e pattugliamento. Se sfruttate prudentemente, le CBM possono aiutare nel mantenimento di uno status quo stabile.