Aspects pratiques des convergences eurasiennes actuelles

Conférence prononcée par Robert Steuckers pour les « Deuxièmes journées eurasistes » de Bordeaux, 5 septembre 2015

Bonjour à tous et désolé de ne pouvoir être physiquement présent parmi vous, de ne pouvoir vous parler qu’au travers de « Skype ».

Je vais essentiellement vous présenter un travail succinct, une ébauche, car je n’ai que trois quarts d’heure à ma disposition pour brosser une fresque gigantesque, un survol rapide des mutations en cours sur la grande masse continentale eurasiatique aujourd’hui. Je ne vous apporterai ce jour qu’un squelette mais vous promets simultanément un texte bien plus étoffé, comme ce fut d’ailleurs le cas après les « journées eurasistes » d’octobre 2014 à Bruxelles.

L’incontournable ouvrage du Professeur Beckwith

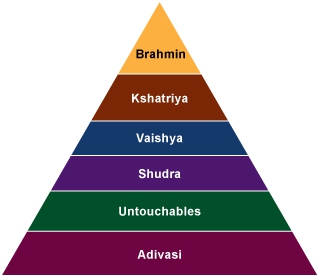

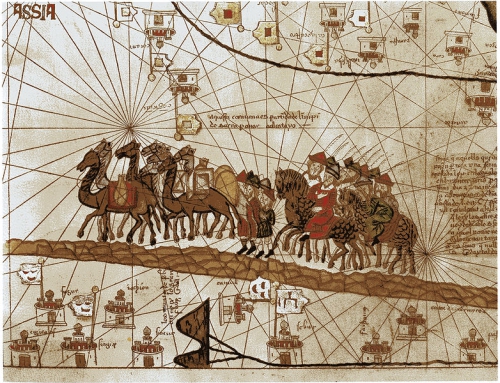

Lors de ces premières rencontres eurasistes de Bruxelles, tenues dans les locaux du vicariat à deux pas de la fameuse Place Flagey, je me suis concentré sur les grandes lignes à retenir de l’histoire des convergences eurasiatiques, en tablant principalement sur l’ouvrage incontournable, fouillé, du Professeur Christopher I. Beckwith de l’Université de Princeton. Pour le Prof. Beckwith, la marque originelle de toute pensée impériale eurasienne vient de la figure du Prince indo-européen, ou plutôt indo-iranien, qui émerge à la proto-histoire, un Prince qui a tout le charisme et l’exemplarité nécessaires, toutes les vertus voulues, pour entraîner derrière lui une « suite » de fidèles, un « comitatus », comme l’attestent d’ailleurs la figure mythologique du Rama védique et celle de Zarathoustra, fondant ainsi une période axiale, selon la terminologie philosophique forgée par Karl Jaspers et reprise par Karen Armstrong. Le Prince charismatique et son « comitatus » injectent les principes fondamentaux de toute organisation tribale (essentiellement, au départ, de peuples cavaliers) et, par suite, de tout organisation territoriale et impériale, ainsi que le montre le premier empire de facture indo-européenne sur le Grand Continent eurasiatique, l’Empire perse. Ce modèle est ensuite repris par les peuples turco-mongols. Cette translatio au profit des peuples turco-mongols ne doit pas nous faire oublier, ici en Europe, le « droit d’aînesse » des peuples proto-iraniens.

J’espère pouvoir aborder la dimension religieuse des convergences eurasiatiques lors de futures rencontres eurasistes, en tablant sur des œuvres fondamentales mais largement ignorées dans nos contextes de « grand oubli », de « grand effacement », car nous savons, depuis les travaux de feue Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann que le système dominant procède par omission de thématiques dérangeantes pour n’imposer que du prêt-à-penser, pour ancrer l’oubli dans les masses déboussolées. Parmi ces œuvres à ré-explorer, il y a celle de l’explorateur et anthropologue italien Giuseppe Tucci, dont Payot avait jadis publié l’immense travail sur les religiosités d’Asie centrale, sur les syncrétismes du cœur de l’Asie. Ceux-ci ont émergé sur un socle shamaniste, dont toutes les variantes du bouddhisme, surtout au Tibet, en Mongolie, dans les confins bouriates, ont gardé des éléments clefs. Le « Baron fou », Fiodor von Ungern-Sternberg, commandeur de la division de cavalerie asiatique du dernier Tsar Nicolas II, était justement fasciné par cette synthèse, étudiée à fond par Tucci. Ensuite, comme le préconise Claudio Mutti, le directeur de la revue de géopolitique italienne Eurasia, une relecture des travaux de Henry Corbin s’avère impérative : elle porte sur les traditions avestiques, sur le culte iranien de la Lumière, sur la transposition de ce culte dans le chiisme duodécimain, sur l’œuvre du mystique perse Sohrawardî, etc. Mutti voit en Corbin le théoricien d’une sagesse eurasiatique qui émergera après l’effacement des religions et confessions actuelles, en phase de ressac et de déliquescence. Le culte de la Lumière, et de la Lumière intérieure, du Xvarnah, de l’auréole charismatique, également évoquée par Beckwith, est appelé à prendre la place de religiosités qui ont lamentablement basculé dans une méchante hystérie ou dans une moraline rédhibitoire. L’avenir ne peut appartenir qu’à un retour triomphal d’une religiosité archangélique et michaëlienne, au service de la transparence lumineuse et du Bien commun en tous points de la planète.

Aujourd’hui, cependant, je me montrerai plus prosaïque, davantage géopolitologue, en n’abordant que les innombrables aspects pratiques que prennent aujourd’hui les convergences eurasiatiques. Les initiatives sont nombreuses, en effet. Il y a la diplomatie nouvelle induite par la Russie et son ministre des affaires étrangères Sergueï Lavrov ; il y a ensuite les initiatives chinoises, également diplomatiques avec la volonté d’injecter dans les relations internationales une manière d’agir qui ne soit pas interventionniste et respecte les institutions et les traditions des peuples autochtones, mais surtout la volonté de créer de multiples synergies en communications ferroviaires et maritimes pour relier l’Europe à la Chine. Ensuite, l’Inde, sans doute dans une moindre mesure, participe à ces synergies asiatiques. Le groupe des BRICS suggère un système bancaire international alternatif. L’ASEAN vise à annuler les inconvénients de la balkanisation de l’Asie du Sud-est, en cherchant des modes de relations acceptables et variés avec la Chine et, parfois, avec l’Inde ou la Russie.

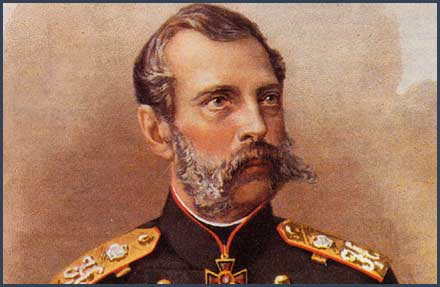

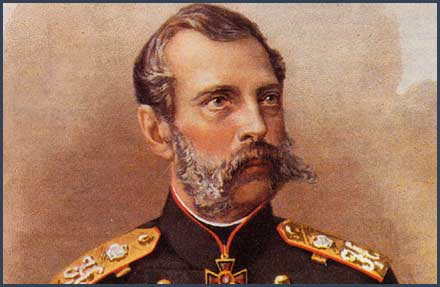

D’Alexandre II à Poutine

Pour le dire en quelques mots simples, la Russie actuelle cherche à retrouver la cohérence du règne d’Alexandre II, qui avait tiré les conclusions de la Guerre de Crimée lorsqu’il avait accédé au trône à 37 ans, en 1855, alors que cette guerre n’était pas encore terminée. La Russie de Poutine et de Lavrov rejette en fait les facteurs, toujours présents, toujours activables, des fragilités russes du temps de Nicolas II et de la présidence d’Eltsine, période de la fin du XXe siècle que les Russes assimilent à une nouvelle « Smuta », soit à une époque de déliquescence au début du XVIIe siècle. L’idée de « smuta », de déchéance politique totale, est une hantise des Russes et des Chinois (leur XIXe siècle, après les guerres de l’opium) : pour les Européens de l’Ouest, la « smuta » première, c’est l’époque des « rois fainéants », des mérovingiens tardifs et les historiens, dans un avenir proche, considèreront sans nul doute l’Europe des Hollande, Merkel, Juncker, etc., comme une Europe affligée d’une « smuta » dont les générations futures auront profondément honte.

Pour le dire en quelques mots simples, la Russie actuelle cherche à retrouver la cohérence du règne d’Alexandre II, qui avait tiré les conclusions de la Guerre de Crimée lorsqu’il avait accédé au trône à 37 ans, en 1855, alors que cette guerre n’était pas encore terminée. La Russie de Poutine et de Lavrov rejette en fait les facteurs, toujours présents, toujours activables, des fragilités russes du temps de Nicolas II et de la présidence d’Eltsine, période de la fin du XXe siècle que les Russes assimilent à une nouvelle « Smuta », soit à une époque de déliquescence au début du XVIIe siècle. L’idée de « smuta », de déchéance politique totale, est une hantise des Russes et des Chinois (leur XIXe siècle, après les guerres de l’opium) : pour les Européens de l’Ouest, la « smuta » première, c’est l’époque des « rois fainéants », des mérovingiens tardifs et les historiens, dans un avenir proche, considèreront sans nul doute l’Europe des Hollande, Merkel, Juncker, etc., comme une Europe affligée d’une « smuta » dont les générations futures auront profondément honte.

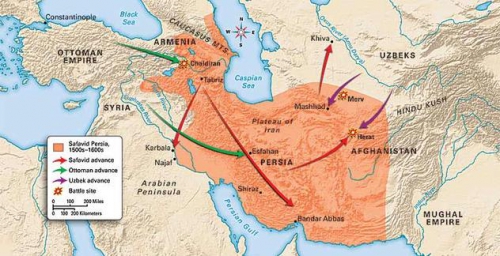

Aujourd’hui, les risques auxquels la Russie est confrontée restent les mêmes que du temps de la guerre de Crimée ou du règne de Nicolas II. Elle est en effet tenue en échec en Mer Noire malgré le retour de la Crimée à la mère-patrie : l’OTAN peut toujours faire jouer le verrou turc. Elle est menacée dans le Caucase, où elle avait soumis les peuples montagnards après des campagnes extrêmement dures, très coûteuses en hommes et en matériels. Sous Alexandre II, elle franchit la ligne Caspienne-Aral pour s’avancer en direction de l’Afghanistan : cette marche en avant vers l’Océan Indien s’avère pénible et Alexandre II prend parfaitement conscience des facteurs temps et espace qui freinent l’élan de ses troupes vers le Sud. Le temps des campagnes doit être réduit, les espaces doivent être franchis plus vite. La solution réside dans la construction de chemins de fer, d’infrastructures modernes.

Des ONG qui jouent sur tous les registres de la russophobie

La réalisation de ces projets de grande ampleur postule une modernisation pratique et non idéologique de la société russe, avec, à la clef, une émancipation des larges strates populaires. Le nombre réduit de la classe noble ne permettant pas le recrutement optimal de cadres pour de tels projets. Dès 1873, dès l’avancée réelle des forces du Tsar vers l’Afghanistan donc potentiellement vers le sous-continent indien, clef de voûte de l’Empire britannique dans l’Océan Indien, dit l’« Océan du Milieu », commence le « Grand Jeu », soit la confrontation entre la thalassocratie britannique et la puissance continentale russe. De 1877 à 1879, la Russie prend indirectement pied dans les Balkans, en tablant sur les petites puissances orthodoxes qui viennent de s’émanciper du joug ottoman. Entre 1879 et 1881, la Russie d’Alexandre II est secouée par une vague d’attentats perpétrés par les sociaux-révolutionnaires qui finiront par assassiner le monarque. La Russie faisait face à des révolutionnaires fanatiques, sans nul doute téléguidés par la thalassocratie adverse, tout comme, aujourd’hui, la Russie de Poutine, parce qu’elle renoue en quelque sorte avec la pratique des grands projets infrastructurels inaugurée par Alexandre II, doit faire face à des ONG mal intentionnées ou à des terroristes tchétchènes ou daghestanais manipulés de l’extérieur. Alexandre III et Nicolas II prennent le relais du Tsar assassiné. Nicolas II sera également fustigé par les propagandes extérieures, campé comme un Tsar sanguinaire, modèle d’une « barbarie asiatique ». Cette propagande exploite toutes les ressources de la russophobie que l’essayiste suisse Guy Mettan vient de très bien mettre en exergue dans Russie-Occident – Une guerre de mille ans. Curieusement, la Russie de Nicolas II est décrite comme une « puissance asiatique », comme l’expression féroce et inacceptable d’une gigantomanie territoriale mongole et gengiskhanide, alors que toute la littérature russe de l’époque dépréciait toutes les formes d’asiatisme, se moquait des engouements pour le bouddhisme et posait la Chine et son mandarinat figé comme un modèle à ne pas imiter. L’eurasisme, ultérieur, postérieur à la révolution bolchevique de 1917, est partiellement une réaction à cette propagande occidentale qui tenait absolument à « asiatiser » la Russie : puisque vous nous décrivez comme des « Asiates », se sont dit quelques penseurs politiques russes, nous reprenons ce reproche à notre compte, nous le faisons nôtre, et nous élaborons une synthèse entre impérialité romano-byzantine et khanat gengiskhanide, que nous actualiserons, fusionnerons avec le système léniniste et stalinien, etc.

Pour affaiblir l’empire de Nicolas II, en dépit de l’appui français qu’il reçoit depuis la visite d’Alexandre III à Paris dans les années 1890, l’Angleterre cherche un allié de revers et table sur une puissance émergente d’Extrême-Orient, le Japon, qui, lui, tentait alors de contrôler les côtes du continent asiatique qui lui font immédiatement face : déjà maître de Taiwan et de la Corée après avoir vaincu la Chine déclinante en 1895, le Japon devient le puissant voisin tout proche de la portion pacifique de la Sibérie désormais russe. Londres attisera le conflit qui se terminera par la défaite russe de 1904, face à un Japon qui, suite à l’ère Meiji, avait réussi son passage à la modernité industrielle. Les navires russes en partance pour le Pacifique n’avaient pas pu s’approvisionner en charbon dans les relais britanniques, au nom d’une neutralité affichée, en toute hypocrisie, mais qui ne l’était évidemment pas...

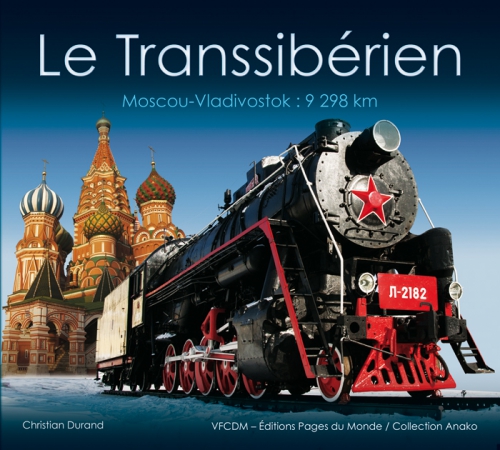

Le Transsibérien bouleverse la donne géostratégique

Les troupes russes au sol, elles, s’étaient déplacées beaucoup plus rapidement qu’auparavant grâce aux premiers tronçons du Transsibérien. L’état-major britannique est alarmé et se rappelle du coup de bélier des armées tsaristes contre la Chine, lorsqu’il s’était agi de dégager le quartier des légations à Pékin, lors du siège de 55 jours imposé aux étrangers, suite à la révolte des Boxers entre juin et août 1900. Le géographe Sir Halford John Mackinder énonce aussitôt les fameuses théories géopolitiques de la dialectique Terre/Mer et de la « Terre du Milieu », du « Heartland », inaccessible à la puissance de feu et à la capacité de contrôle des rimlands dont disposait à l’époque la puissance maritime anglaise. Le Transsibérien permettait à la Russie de Nicolas II de sortir des limites spatio-temporelles imposées par le gigantisme territorial, qui avait, au temps des guerres napoléoniennes, empêché Paul I de joindre ses forces à celles de Napoléon pour marcher vers les Indes. Henri Troyat explique avec grande clarté à ses lecteurs français tous ces projets dans la monographie qu’il consacre à Paul I. De même, la Russie avait perdu la Guerre de Crimée notamment parce que sa logistique lente, à cause des trop longues distances terrestres à franchir pour fantassins et cavaliers, ne lui avait pas permis d’acheminer rapidement des troupes vers le front, tandis que les navires de transport anglais et français pouvaient débarquer sans entraves des troupes venues de la métropole anglaise, de Marseille ou d’Algérie. L’élément thalassocratique avait été déterminant dans la victoire anglo-française en Crimée.

La Russie de Nicolas II, bien présente en Asie centrale, va dès lors, dans un premier temps, payer la note que les Britanniques avaient déjà voulu faire payer à Alexandre II, le conquérant de l’Asie centrale, assassiné en 1881 par une bande de révolutionnaires radicaux, appartenant à Narodnaïa Voljia. La Russie d’Alexandre II pacifie le Caucase, le soustrayant définitivement à toute influence ottomane ou perse, donc à toute tentative anglaise d’utiliser les empires ottoman et perse pour contribuer à l’endiguement de cette Russie tsariste, conquiert l’Asie centrale et affirme sa présence en Extrême-Orient, notamment dans l’île de Sakhaline. Au même moment, les marines passent entièrement des voiles et de la vapeur (et donc du charbon) au pétrole. La Russie détient celui de Bakou en Azerbaïdjan. La possession de cette aire sud-caucasienne, la proximité entre les troupes russes et les zones pétrolifères iraniennes fait de la Russie l’ennemi potentiel le plus redoutable de l’Angleterre qui, pour conserver l’atout militaire majeur qu’est sa flotte, doit garder la mainmise absolue sur ces ressources énergétiques, en contrôler une quantité maximale sur la planète.

L’assassinat de Stolypine

Comme le danger allemand devient aux yeux des Britannique plus préoccupant que le danger russe, -parce que la nouvelle puissance industrielle germanique risque de débouler dans l’Egée et en Egypte grâce à son alliance avec l’Empire ottoman moribond- l’Empire de Nicolas II est attiré dans l’alliance franco-anglaise, dans l’Entente, à partir de 1904. Stolypine, partisan et artisan d’une modernisation de la société russe pour faire face aux nouveaux défis planétaires, aurait sans doute déconstruit progressivement et habilement le corset qu’impliquait cette alliance, au nom d’un pacifisme de bon aloi, mais il est assassiné par un fanatique social-révolutionnaire en 1911 (les spéculations sont ouvertes : qui a armé le bras de ce tueur fou ?). Stolypine, qui aurait pu, comme Jaurès, être un frein aux multiples bellicismes qui animaient la scène européenne avant la Grande Guerre, disparaît du monde politique sans avoir pu parachever son œuvre de redressement et de modernisation. La voie est libre pour les bellicistes russes qui joindront leurs efforts à ceux de France et d’Angleterre. Ce qui fait dire à quelques observateurs actuels que Poutine est en somme un Stolypine qui a réussi.

Comme le danger allemand devient aux yeux des Britannique plus préoccupant que le danger russe, -parce que la nouvelle puissance industrielle germanique risque de débouler dans l’Egée et en Egypte grâce à son alliance avec l’Empire ottoman moribond- l’Empire de Nicolas II est attiré dans l’alliance franco-anglaise, dans l’Entente, à partir de 1904. Stolypine, partisan et artisan d’une modernisation de la société russe pour faire face aux nouveaux défis planétaires, aurait sans doute déconstruit progressivement et habilement le corset qu’impliquait cette alliance, au nom d’un pacifisme de bon aloi, mais il est assassiné par un fanatique social-révolutionnaire en 1911 (les spéculations sont ouvertes : qui a armé le bras de ce tueur fou ?). Stolypine, qui aurait pu, comme Jaurès, être un frein aux multiples bellicismes qui animaient la scène européenne avant la Grande Guerre, disparaît du monde politique sans avoir pu parachever son œuvre de redressement et de modernisation. La voie est libre pour les bellicistes russes qui joindront leurs efforts à ceux de France et d’Angleterre. Ce qui fait dire à quelques observateurs actuels que Poutine est en somme un Stolypine qui a réussi.

Dès que la Russie s’ancre plus solidement dans l’Entente, la propagande hostile à Nicolas II, orchestrée depuis Londres, fait volte-face : le Tsar cesse d’un coup d’être un abominable monarque sanguinaire et devient, comme par miracle, un empereur bon, paternel, qui aime ses sujets. Staline connaîtra un destin similaire : horrible boucher sanguinaire pour ses purges des années 1930, « bon petit père des peuples » pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, tyran antidémocratique dès que s’amorce la guerre froide. Avant Orwell, Lord Ponsonby décortiquera les mécanismes de cette propagande bien huilée, capable de changer de cap, de désigner comme ennemi l’ami d’hier et vice-versa, exactement comme dans l’Oceania de Big Brother. La Russie entre dans la Grande Guerre aux côtés des autres puissances de l’Entente : ce sera sa perte. Dmitri Merejkovski l’avait prévu. Les analyses de Soljénitsyne abondent également dans ce sens. L’affaire désastreuse des Dardanelles, voulue par Churchill en 1915, avait pour objectif inavoué d’arriver à Constantinople avant les Russes et de verrouiller les détroits turcs comme en 1877-78 : la duplicité londonienne ne s’était pas effacée au nom de la fraternité d’armes de 1914.

Au temps des deux « géants rouges »

La Russie actuelle, celle de Poutine, entend conserver la cohérence territoriale de l’Union Soviétique défunte mais sans la rigidité idéologique communiste. Le communisme était une « idéologie froide » (Papaioannou) et un « système réductionniste » (Koestler), dont les retombées pratiques s’avéraient désastreuses, notamment sur le plan de la nécessaire autarcie agricole que devrait détenir toute grande puissance de dimensions continentales. Toute puissance de cet ordre de grandeur a pour obligation pratique de maintenir une « cohérence territoriale », de colmater toutes les brèches qui pourraient survenir au fil du temps, que celles-ci soient le fait de dissidences intérieures ou d’une subversion organisée par l’ennemi. Sous d’autres oripeaux que ceux du communisme, Poutine cherche à rétablir les atouts dont disposait l’Union soviétique entre 1949 et 1972, quand elle formait, avec la Chine, un bloc communiste de très grande profondeur territoriale. La Chine maoïste et l’URSS, de Staline à Brejnev, étaient certes des puissances continentales dont l’idéologie officielle était posée comme « progressiste ». Elles ont toutefois été marquées par une régression industrielle et technologique permanente par rapport aux Etats-Unis, au Japon ou à l’Europe occidentale, corroborant la théorie américaine du technological gap. Les développements internes à l’ère communiste ont certes balayé quelques archaïsmes, il faut le reconnaître, mais à quel prix ? Aujourd’hui, la situation est différente. La Chine est à la pointe de nombreuses innovations techniques. Elle est capable de développer des réseaux de chemins de fer performants, de construire des infrastructures aéroportuaires ultra-modernes, de gérer les flux de trafic urbain par d’audacieuses innovations technologiques, de fabriquer des porte-avions à double piste, etc.

Même si on ne peut pas dire que la Russie et la Chine n’ont plus aucun contentieux, le binôme sino-russe tient parce qu’à Moscou comme à Beijing les diplomates savent que le déclin de l’URSS a commencé en 1972 quand Nixon et Kissinger déploient une intense activité diplomatique en direction de la Chine et transforment celle-ci en un allié de revers contre Moscou. 1972, il faut s’en souvenir, a été une année charnière : l’URSS était encerclée, coincée entre l’OTAN et la Chine, son déclin s’est automatiquement amorcé, tandis que la Chine, attelée à cette alliance de facto avec les Etats-Unis, était contrainte d’opter pour un développement continental, soit de tourner le dos au Pacifique, de ne plus y contrarier les intérêts stratégiques américains. Kissinger faisait ainsi d’une pierre deux coups : il affaiblissait la Russie et détournait la Chine maoïste des eaux du Pacifique (ce qui n’est plus le cas aujourd’hui, comme l’attestent les incidents récurrents en Mer de Chine du Sud).

De l’alliance sino-américaine au déclin de l’Union Soviétique

Washington consolidait ainsi son hégémonisme planétaire et unipolaire : De Gaulle était mort, l’Allemagne et l’Europe toujours divisées, les stratégistes américains planifiaient déjà la chute du Shah, coupable d’avoir soutenu les revendications des pays producteurs de pétrole et de développer une puissance régionale sérieuse, appuyée par des forces aériennes et navales efficaces, dans une zone hautement stratégique. Pour le monde musulman, 1979, année de la prise du pouvoir par Khomeiny, appuyé par les services américains, britanniques et israéliens dans un premier temps, sera l’année-charnière car, dès ce moment, il sera travaillé par des forces hostiles à l’ordre du monde de type « westphalien », ce qui nous conduira au chaos non maîtrisable que nous connaissons aujourd’hui. Avec ce désordre anti-westphalien sur son flanc sud, Poutine cherche tout simplement un pôle de stabilité alternative, permettant un développement normal de la Fédération de Russie dans un cadre impérial cohérent, combinant in fine les acquis d’Alexandre II -qui avait déclenché le « Grand Jeu »- et la sécurité stratégique obtenue par l’URSS après la seconde guerre mondiale et surtout à l’époque entre 1949 et 1972, quand la Chine ne dépendait en aucune façon des Etats-Unis et de leurs alliances sur les rimlands d’Eurasie. Cette sécurité, offrant la stabilité, doit aussi se refléter sur les plans religieux et idéologique : la pluralité des confessions ou des approches idéologiques ou, encore, des politiques économiques, ne doit pas nécessairement provoquer des dynamiques centrifuges. Au-delà de tous les clivages établis par l’histoire sur la masse continentale centre-asiatique, la politique générale doit être convergente et ne plus admettre les divergences qui conduisent inexorablement à une « smuta ». Cette volonté de convergence devrait valoir aussi pour l’Europe, au sens le plus strict du terme : cette idée était déjà présente chez le Tsar Alexandre I qui, après les troubles de l’ère révolutionnaire et napoléonienne, avait envisagé une convergence religieuse en Europe, une fusion de l’orthodoxie, du catholicisme et du protestantisme, pour consolider la première ébauche d’union eurasienne qu’était la Sainte-Alliance.

Washington consolidait ainsi son hégémonisme planétaire et unipolaire : De Gaulle était mort, l’Allemagne et l’Europe toujours divisées, les stratégistes américains planifiaient déjà la chute du Shah, coupable d’avoir soutenu les revendications des pays producteurs de pétrole et de développer une puissance régionale sérieuse, appuyée par des forces aériennes et navales efficaces, dans une zone hautement stratégique. Pour le monde musulman, 1979, année de la prise du pouvoir par Khomeiny, appuyé par les services américains, britanniques et israéliens dans un premier temps, sera l’année-charnière car, dès ce moment, il sera travaillé par des forces hostiles à l’ordre du monde de type « westphalien », ce qui nous conduira au chaos non maîtrisable que nous connaissons aujourd’hui. Avec ce désordre anti-westphalien sur son flanc sud, Poutine cherche tout simplement un pôle de stabilité alternative, permettant un développement normal de la Fédération de Russie dans un cadre impérial cohérent, combinant in fine les acquis d’Alexandre II -qui avait déclenché le « Grand Jeu »- et la sécurité stratégique obtenue par l’URSS après la seconde guerre mondiale et surtout à l’époque entre 1949 et 1972, quand la Chine ne dépendait en aucune façon des Etats-Unis et de leurs alliances sur les rimlands d’Eurasie. Cette sécurité, offrant la stabilité, doit aussi se refléter sur les plans religieux et idéologique : la pluralité des confessions ou des approches idéologiques ou, encore, des politiques économiques, ne doit pas nécessairement provoquer des dynamiques centrifuges. Au-delà de tous les clivages établis par l’histoire sur la masse continentale centre-asiatique, la politique générale doit être convergente et ne plus admettre les divergences qui conduisent inexorablement à une « smuta ». Cette volonté de convergence devrait valoir aussi pour l’Europe, au sens le plus strict du terme : cette idée était déjà présente chez le Tsar Alexandre I qui, après les troubles de l’ère révolutionnaire et napoléonienne, avait envisagé une convergence religieuse en Europe, une fusion de l’orthodoxie, du catholicisme et du protestantisme, pour consolider la première ébauche d’union eurasienne qu’était la Sainte-Alliance.

Ukraine et « Corridor 5 »

Suite à la petite « smuta » de l’ère eltsinienne, la Russie n’a même pas pu conserver le projet d’une union entre les trois républiques slaves de l’ex-URSS, rêvée par Alexandre Soljénitsyne dès son exil américain. Les forces hostiles à toute union (formelle ou informelle) de l’Eurasie, à toute résurrection de la Sainte-Alliance, aux convergences générées par des communications optimales ont visé l’Ukraine, appelée à se détacher de la symbiose voulue par Soljénitsyne. Deux raisonnements historico-stratégiques ont conduit à cette politique :

1) l’Ukraine redessinée par Khrouchtchev dans les années 1950 contenait la Crimée, presqu’île dans l’espace maritime pontique sans laquelle la Russie n’a plus aucune projection vers la Méditerranée et ne peut plus être une grande puissance qui compte ;

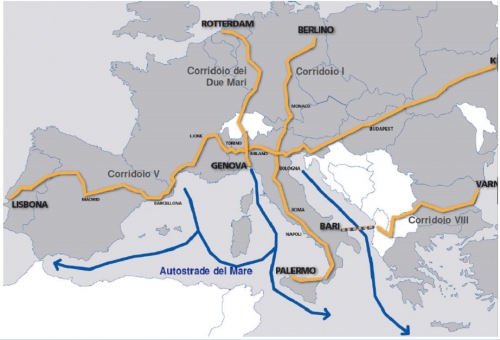

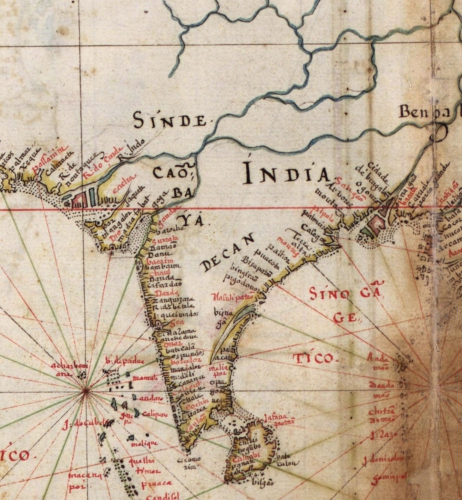

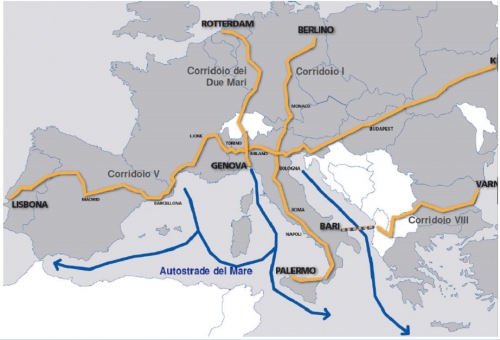

2) ensuite, l’Ukraine, dans la partie occidentale de la masse continentale eurasiatique, est un espace de transit, que les géopolitologues appellent, en anglais, a gateway region. Pour infliger une paralysie à l’adversaire, il convient en effet de bloquer tout transit en de telles régions, a fortiori si l’on veut bloquer les communications entre les puissances situées de part et d’autre de cet espace de transit. De Cadix à Kiev, l’Europe est traversée par ce qu’il est convenu d’appeler le « Corridor 5 ». A partir de Kiev, ce « corridor », poursuivi, mène en Inde, en Chine et sur les côtes du Pacifique : ce sont les tronçons de l’antique « route de la soie », empruntés par Marco Polo.

Pour toute puissance hégémonique hostile à la fois à la Russie et à l’Europe (centrée autour du pôle industriel allemand), le « Corridor 5 » doit être bloqué en tout lieu où l’on peut réanimer un conflit ancien moyennant les stratégies habituelles de subversion. La subversion de l’Ukraine -au nom de conflits anciens et au bénéfice apparent de forces idéologiques autochtones, ultranationalistes, dont on combat pourtant les homologues partout ailleurs dans le monde- est par conséquent, un modèle d’école. On a délibérément choisit l’Ukraine parce qu’elle est une zone de transit des gazoducs russes en direction de l’Europe. En transformant l’Ukraine en une zone de turbulences, on oblige Russes et Européens à investir inutilement dans des projets alternatifs, pour contourner un pays désormais hostile, non pas parce qu’il entend défendre ses propres intérêts légitimes, mais, au contraire, parce qu’il veut, en dépit du bon sens, faire triompher les intérêts d’une puissance hégémonique, étrangère aux espaces russe et européen. Le nouveau gouvernement ukrainien se détache de la sorte de l’espace civilisationnel européen dont il fait partie.

Par ailleurs, la subversion, inspirée par certains préceptes de Sun Tzu, vise aussi à anéantir les ressorts traditionnels d’une puissance ennemie : à l’heure des grands médias, cette forme de subversion déploie des spectacles ou des provocations déliquescentes, à l’instar des « pussy riots » ou des « femens ». Ce type d’actions subversives sape les fondements éthiques d’une société, en tablant sur les bas instincts et les carences en discernement du grand nombre, et, partant, détruit la cohésion de la politie, en ruine les structures sociales, les assises religieuses. La Russie de Poutine a veillé à annuler les capacités de nuisance de ces entreprises, fautrices de déliquescence irrémédiable, au grand dam des officines, généralement américaines, qui les avaient activées dans la ferme intention de saper les assises de la société russe et d’ébranler l’édifice étatique de la Fédération de Russie.

Le mythe occidental des « sociétés ouvertes »

La Russie de Poutine, comme toute autre Russie qui chercherait à se consolider sur le long terme, doit donc retrouver une stabilité territoriale et géopolitique englobant les atouts de la Russie d’Alexandre II et ceux de l’URSS entre 1949 et 1972, quand la longue frontière centre-asiatique avec la Chine était sécurisée : face à la Chine post-communiste, Poutine ne répétera pas l’hostilité sourde et sournoise de Staline et de ses successeurs à l’égard de la Chine maoïste, en dépit d’une unité idéologique de façade qui faisait parler des deux « géants rouges ». La cohérence qu’il vise, à la fois tsariste et communiste, doit se compléter par une ouverture à d’autres zones de grande importance géostratégique dans le monde, afin de pallier les désavantages énormes que les fermetures communistes avaient entrainés. Dans la dialectique Sociétés ouvertes / Sociétés fermées, imaginée par Karl Popper, les sociétés russe et chinoise d’aujourd’hui optent pour un équilibre entre ouverture et fermeture : elles refusent l’ouverture tous azimuts, préconisée par les tenants du globalisme néolibéral (Soros, etc.) ; elles refusent tout autant les fermetures rigides pratiquées par les communismes stalinien, brejnevien, albanais et maoïste. Ce double refus passe par un retour en Chine à la pensée pragmatique de Confucius (condamné par les nervis maoïstes de la « révolution culturelle » des années 1960) et en Russie à des étatistes pragmatiques et bâtisseurs tels qu’en a connus l’histoire russe de la fin du XIXe siècle à 1914. Cette synthèse nouvelle entre ouverture et fermeture, pour reprendre la terminologie inaugurée par Popper, postule un rejet de l’extrémisme néolibéral, un planisme souple de gaullienne mémoire, une volonté de provoquer la « dé-dollarisation » de l’économie planétaire et de créer une alternative solide au système anglo-saxon, manchestérien et néolibéral. Cette synthèse, que l’on vise mais qui n’a pas encore été réalisée, loin s’en faut, permet déjà de forger des économies hétérodoxes, chaque fois adaptées aux contextes historiques et sociaux dans lesquelles elles sont censées s’appliquer. Disparaît alors la volonté enragée et monomaniaque de vouloir imposer à toutes les économies du monde un seul et même modèle.

Le monde est un « pluriversum »

Russes et Chinois espèrent trouver dans le BRICS des cohérences nouvelles dans une diversité bien équilibrée, dans un « pluriversum » apte à respecter la diversité du monde contre toutes les tentatives de l’homogénéiser. Le groupe BRICS constitue une alternative plurielle au système dominant et américano-centré, le monde des Etats n’étant pas un « univers » mais bien un « plurivers » comme le disait le philosophe allemand du politique Bernhard Willms, décédé en 1991, et comme l’affirme aujourd’hui l’analyste géopolitique russe Leonid Savin. La recherche d’une économie hétérodoxe, souple et contextualisée (selon le vocabulaire du MAUSS, « Mouvement Anti-Utilitariste dans les Sciences Sociales »), correspond aussi à la volonté chinoise de déployer, à l’échelle planétaire, une diplomatie souple, hostile à toute pratique hystérique de l’immixtion, comme celles que préconisent les néo-conservateurs américains, les nouveaux philosophes regroupés peu ou prou derrière le pompon de Bernard-Henri Lévy ou les extrémistes salafistes stipendiés par l’Arabie Saoudite.

La Chine préconise ainsi une diplomatie de la non-intervention dans les affaires intérieures des Etats tiers. La généralisation de ce principe, plus doux et plus pacifique que les modes de fonctionnement occidentaux actuels, devrait conduire à terme à supprimer ces facteurs d’ingérence et de conflits inutiles que sont bon nombre d’ONG américaines : en Chine, elles ne fonctionnent guère, sauf quand elles font appel à des fondamentalistes salafistes du Turkestan chinois, soutenus par les Turcs et les Saoudiens, ou à des sectes pseudo-religieuses farfelues ou quand elles instrumentalisent le Dalaï Lama. La Russie a commencé ce travail de neutralisation des organismes fauteurs de troubles et de guerres en jugulant le travail subversif des ONG d’Outre-Atlantique, considérées à juste titre comme des facteurs de « smuta », et en amorçant le contrôle des médias, de Google, etc.

Le but premier d’un mouvement eurasien serait dès lors de participer à ces nouvelles forces à l’œuvre sur la planète, à favoriser les innovations qu’elles apportent pour nous sortir d’impasses mortifères.

Empêcher le basculement de l’Europe vers la Russie, l’Eurasie, la Chine et l’Iran

Mais cette vaste panoplie d’innovations, qui cherchent à s’imposer partout dans le monde, va, bien entendu, provoquer une riposte de l’hegemon. Les conflits d’Ukraine et de Syrie ont été activés par des stratégistes mal intentionnés pour entraver la marche en avant de cet ensemble alternatif, englobant l’Europe. En effet, l’objectif premier des stratégistes de l’hegemon est d’empêcher à tout prix le glissement de l’Europe vers les puissances eurasiennes du groupe BRICS et vers l’Iran. C’est donc en premier lieu vers les zones possibles de connexion entre notre sous-continent et le reste de l’Eurasie que l’hegemon doit agir pour bloquer cette synergie grande-continentale. L’Ukraine avec, notamment, les ports de Crimée, était en quelque sorte l’interface entre la civilisation grecque, puis byzantine, et les voies terrestres vers le centre de l’Asie, l’Inde et la Chine ; elle a gardé cette fonction aux temps médiévaux des entreprises génoises qui demeuraient branchées sur les « routes de la soie » du nord, en dépit des tentatives de blocage perpétrées au Sud et au niveau du Bosphore par les Seldjouks puis par les Ottomans. La façade maritime méditerranéenne du Levant, soit du Liban et de la Syrie actuels, donnait accès aux routes de la soie menant, par la Mésopotamie et l’espace perse, aux Indes et à la Chine. Aujourd’hui, la Chine a développé les capacités de créer des réseaux ferroviaires trans-eurasiens, où les territoires de la Fédération de Russie, du Kazakhstan et de quelques autres anciennes républiques majoritairement musulmanes de l’ex-URSS, servent de jonction entre les deux espaces, l’européen et le chinois, que Leibniz jugeait déjà les « plus élevés en civilisation ».

Les stratégistes mal intentionnés prévoient d’autres blocages dans la zone de connexion entre notre Europe et le reste de l’Eurasie. D’abord il y a la possibilité de créer une zone de turbulences durables, un abcès de fixation, en Transnistrie et en Moldavie, en bloquant tout transit entre l’Ukraine et l’Europe, tandis que le territoire du Donbass empêche déjà toute communication fluide entre l’Ukraine et la Russie du Don, de la Volga et de la Caspienne. Au sud, un général américain, Ben Hodges, commandant de l’OTAN jusqu’en 2014, envisage de soulever le Caucase du Nord en réactivant les conflits russo-tchétchène et russo-ingouche, de façon à troubler l’acheminement des hydrocarbures de la Caspienne et de créer une zone de turbulences sur le long terme entre les territoires russe et iranien. De même, ces stratégistes envisagent de réanimer le conflit russo-géorgien, placé au frigidaire depuis août 2008. Ou de déclencher un nouveau conflit entre l’Arménie et l’Azerbaïdjan pour la région du Nagorny-Karabach, ce qui aurait pour effet de bloquer toute liaison territoriale entre la Russie et l’Iran, surtout après le faux dégel entre l’Occident et Téhéran que l’on observe depuis les dernières semaines de l’année 2015. Plus à l’est, les mêmes stratégistes envisagent un projet de « chaotisation complète » de l’Asie centrale post-soviétique. Au départ de l’Afghanistan, ils envisagent de faire pénétrer au Turkménistan, au Tadjikistan, au Kirghizistan voire en Ouzbékistan des éléments fondamentalistes (talibans, partisans d’Al Qaeda, avatars de l’Etat islamique, etc., les golems ne manqueront pas…) qui feront subir à ces pays, s’ils se montrent récalcitrants, le sort de l’Irak ou de la Syrie. Le Turkménistan, riverain de la Caspienne et voisin de l’Afghanistan, pourrait être transformé en une zone de turbulences s’il ne cède pas aux pressions de l’OTAN qui lui fait miroiter une aide économique. Des terroristes afghans, que l’on posera comme « incontrôlables » en dépit de la présence américaine là-bas, passeront la frontière pour semer le chaos dans ce pays qui est un producteur d’hydrocarbures et un riverain de la Caspienne.

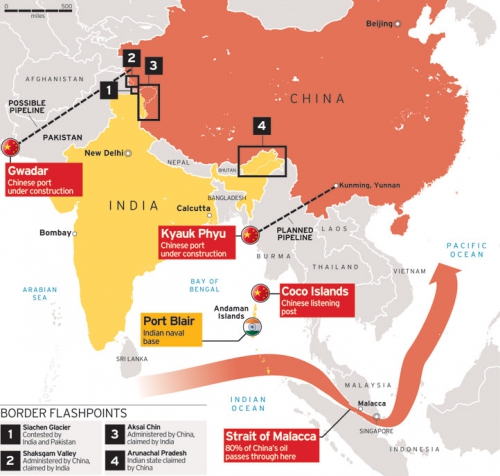

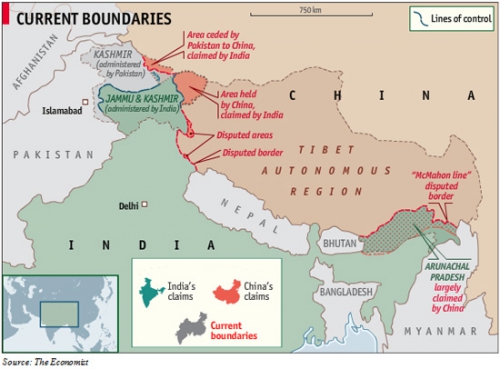

Un chaos créé artificiellement

Ce chaos créé artificiellement est une application agressive de la stratégie ancienne de l’«endiguement». Non seulement il freinera l’acheminement de matières premières et d’hydrocarbures vers l’Europe mais troublera durablement les voies de communication entre la Russie, l’Inde et la Chine, où un pari possible sur des fondamentalistes pakistanais permettrait aussi de bloquer à nouveau les régions du Cachemire-Jammu et de l’Aksai Chin, ruinant toutes les tentatives d’apaisement entre Beijing et New Delhi, lesquelles avaient toujours été laborieuses.

L’objectif impératif que doivent se fixer les cercles eurasistes, c’est d’œuvrer et de militer pour ne pas que nos contemporains s’embarquent dans de telles manœuvres bellicistes, pour qu’ils soient toujours rétifs aux sirènes des propagandes.

Cependant, saper la cohésion européenne, œuvrer à disloquer les sociétés européennes et à affaiblir ses économies nationales et régionales ne passe pas seulement par l’organisation de conflits à ses frontières (Libye, Donbass, Syrie, Caucase) mais aussi, comme certains faits des années 1990 et 2000 semblent l’attester, de provoquer de mystérieux accidents dans le tunnel du Mont Blanc pour bloquer le « Corridor 5 » (toujours lui !), d’organiser des grèves sauvages pour paralyser les communications dans l’Hexagone et autour de lui, comme en 1995 pour mettre Chirac sous pression afin qu’il abandonne son programme nucléaire –Jean Parvulesco se plaisait à le signaler et à rappeler les liens anciens entre certains syndicats socialistes français et l’OSS ou la CIA. Aujourd’hui, les clandestins bloquent parfois le tunnel sous la Manche à Calais, avec l’appui d’associations bizarres, se réclamant d’une xénophilie délirante ou d’une forme d’antifascisme fantasmagorique, dont l’objectif ne peut nullement être qualifié de « rationnel ». Est-ce pour rompre les liens entre la Grande-Bretagne et l’Europe ?

Cet ensemble de pressions constantes, s’exerçant sur les communications entre l’Europe et le reste de la masse continentale eurasiatique, a pour but essentiel d’empêcher la constitution d’un réseau efficace, la réalisation du vœu de Leibniz : faire de la « Moscovie » le pont entre l’Europe et la Chine. Les actuels projets ferroviaires chinois sont en effet très impressionnants. Le nouveau poids de la Chine, certes relatif, pourrait, estiment les stratégistes américains, provoquer un basculement de l’Europe vers l’Asie. Une telle éventualité a été un jour explicitée par Dominique de Villepin : celui-ci estimait que la concrétisation finale des projets ferroviaires et des routes maritimes envisagées par la Chine offrait potentiellement à la France et aux autres pays européens d’innombrables occasions de forger des accords lucratifs avec la Russie, les pays d’Asie centrale et la Chine dans les domaines des transports et des services urbains. Dans un article des Echos, de Villepin écrivait : « C’est là une tâche qui devrait non seulement mobiliser l’Union Européenne et ses Etats membres mais aussi les autorités locales, les chambres de commerce et les hommes d’affaires pour ne même pas mentionner les universités et les boîtes-à-penser ». Grande sagesse. Et clairement exprimée ! En termes très diplomatiques, de Villepin poursuit : le projet de route de la soie « est une vision politique qui induit les pays européens à renouveler le dialogue avec des partenaires du continent asiatique, permettant de forger, par exemple, des projets souples avec la Russie, notamment pour trouver les fonds nécessaires pour re-stabiliser l’Ukraine. Le lien entre l’Est et l’Ouest doit se maintenir ». Mieux : « Nous avons là une vision économique qui adapte la planification chinoise à la coopération économique internationale. Dans un monde financièrement volatile et instable, il s’avère nécessaire d’opter pour la bonne approche dans les projets à long terme, utilisant des outils nouveaux, de type multilatéral ».

Le grand projet OBOR des Chinois

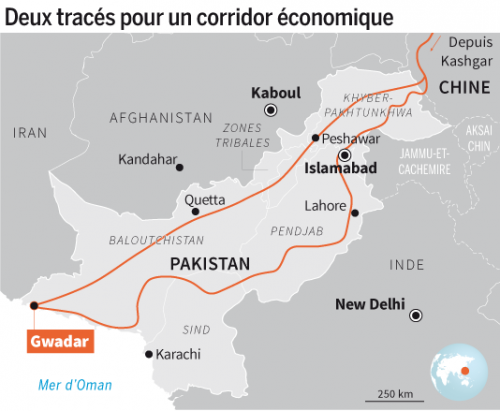

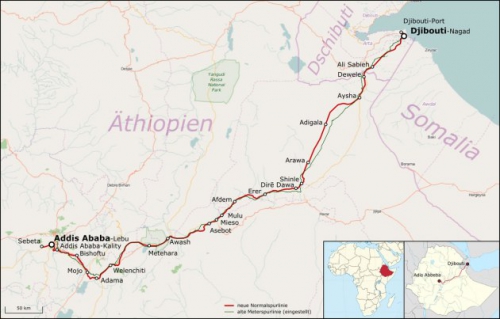

La Chine envisage l’émergence de six corridors économiques, à replacer dans un projet plus vaste, baptisé OBOR (« One Belt, One Road » - soit « Une ceinture (maritime), Une route »). Cet OBOR entend consolider une route maritime de la Chine à l’Iran voire à la Mer Rouge et créer de solides liaisons ferroviaires entre l’Europe et la Chine. Il vise surtout à relier la Chine à soixante pays. Les six corridors majeurs sont : le CMREC ou Corridor économique Chine / Mongolie / Russie ; le NELB ou « Nouveau Pont Terrestre eurasien » (« New Eurasian Land Bridge ») ; le CCWAEC ou Corridor économique Chine / Asie centrale et occidentale ; le CICPEC ou Corridor économique Chine / Péninsule indochinoise ; le CPEC ou Corridor économique Chine / Pakistan ; et, enfin, le BCIMEC ou Corridor économique Bengladesh / Chine / Inde / Myanmar. A ces projets chinois, tous nécessaires d’un point de vue asiatique, s’ajoute celui du « Canal Eurasia », élaboré par les Russes et les Kazakhs. Ce canal doit relier la Caspienne à la Mer d’Azov (face à la Crimée !), permettant notamment d’acheminer du brut vers la Mer Noire donc vers les confins orientaux de l’Europe. L’enjeu ukrainien/criméen prend ici toute son ampleur.

De Marx à List

Ces projets, dont on pourrait dresser une longue liste, démontrent que les puissances du BRICS, du moins la Chine et la Russie, ne sont plus guère affectées, comme jadis, par l’idéologie prêtée à Marx et à Engels mais tentent d’appliquer ou de ré-appliquer les principes pragmatiques de l’économiste Friedrich List (1789-1846). Ce dernier était considéré comme un « libéral » mais, à coup sûr, un libéral « hétérodoxe », soucieux de tenir compte des contextes historiques dans lesquels se déployait l’économie. List était un idéologue du développement. Pour qu’une économie puisse se développer à un rythme correct, l’Etat ne doit nullement jouer un rôle de « veilleur de nuit », à l’instar de ce que souhaitent les théoriciens libéraux anglo-saxons. Au contraire, List pose l’Etat comme une instance constructrice, investisseuse. L’Etat est là pour construire des lignes de chemin de fer et des canaux. C’est List qui planifiera le premier réseau ferroviaire allemand, au sein du Zollverein, de l’Union douanière, dont il fut aussi un père fondateur. En Belgique et aux Etats-Unis, il préconisera le creusement de canaux. En France, il inspirera les praticiens de la « colonisation intérieure ». L’idée du Transsibérien en Russie, les suggestions pratiques des économistes et ingénieurs du Kuo Min Tang chinois s’inspirent toutes d’idées dérivées de List, après sa mort. La politique des grands projets gaulliens est « listienne », de même que le sont les pratiques chinoises, après la parenthèse maoïste et le ressac dû à la tristement célèbre « révolution culturelle » des années 1960. A partir de Deng Xiaoping, la Chine redevient « listienne » et « confucéenne » : c’est à cette double mutation de référence qu’elle doit son succès actuel. Ce serait à un retour à Aristote et à List que l’Europe pourrait devoir son hypothétique renaissance, du moins si l’avenir permettra l’élimination impitoyable des pseudo-élites déchues et abjectes qui nous gouvernent actuellement, exactement comme la Chine maoïste a éliminé sa « bande des quatre », pour ne pas sombrer dans les délires manichéens et idéologiques, dans un remake de la calamiteuse « éthique de conviction » de la « révolution culturelle » et de ses avatars malsains.

Le clivage dans le monde ne passe plus par la dichotomie capitalisme / communisme ni par la piètre distinction entre sociétés ouvertes et sociétés fermées mais par une dichotomie entre « listiens » et néolibéraux qui recoupe aussi la distinction qu’opérait Max Weber entre « éthique de la conviction » et « éthique de la responsabilité ». Les néolibéraux, et le cortège à la Jérôme Bosch que constituent leurs alliés festivistes, gauchistes ou féministes, adhèrent à des éthiques farfelues de la conviction. Leurs adversaires les plus sérieux à une éthique « listienne » de la responsabilité.

L’Allemagne dans ce grand jeu eurasien

Les projets chinois séduisent les Allemands. Ce n’est ni nouveau ni étonnant. Le moteur économique de l’Europe participe aux synergies suggérées par Beijing, en tire de substantiels bénéfices que la délirante « juridification » de la sphère économique tente de réduire par l’artifice de procès farfelus comme celui intenté contre Volkswagen en 2015. Est-ce la raison pour laquelle on tente de faire basculer l’Allemagne de Merkel dans le chaos, en lui imposant des flots d’hères inassimilables, flanqués d’activistes formés au terrorisme et à d’autres formes de guerres de la « quatrième génération », qui n’y produisent que du désordre et de la violence ?

Jusqu’ici, l’Allemagne avait réussi à desserrer la cangue américaine en se branchant sur les gazoducs russes, dont la gestion a été placée sous le patronage et l’impulsion des anciens chanceliers Helmut Schmidt et Gerhard Schröder. Leur socialisme, pragmatique et non idéologique, « listien » et wébérien, conjuguait ses efforts pour parfaire une diplomatie de l’apaisement, une Ostpolitik fructueuse. Ces efforts avaient abouti aux accords permettant, à terme, de construire le tracé des gazoducs « North Stream 1 & 2 », accentuant certes la dépendance allemande par rapport au gaz russe mais déconstruisant simultanément son extrême dépendance politique face au système atlantiste, tandis que le « South Stream » alimente l’Italie, l’Autriche et la Hongrie (où Orban refuse les sanctions contre la Russie, sur fond d’un revival marginal de l’idéologie eurasiste en pays magyar).

Hans Kundnani, dans un article magistral de la revue américaine Foreign Affairs (janvier-février 2015), évoque une « Allemagne post-occidentale », c’est-à-dire une Allemagne qui se serait détachée de ses liens avec l’Occident anglo-saxon, de sa Westbindung, pour se mouvoir vers un espace essentiellement industriel, commercial et énergétique dont les pôles majeurs seraient la Russie et la Chine voire l’Inde. Pour la première fois dans l’histoire de la République Fédérale, une minorité de 45% seulement est encore en faveur du statu quo pro-occidental, impliquant l’adhésion à l’OTAN et/ou à l’UE comme seules possibilités diplomatiques. 49% des Allemands contemporains sont désormais en faveur d’une « position médiatrice », où l’Allemagne équilibrerait le jeu de ses relations entre l’Europe occidentale et la Russie. C’est le résultat tangible d’un anti-américanisme qui s’est sans cesse amplifié depuis la guerre du Golfe, déclenchée par Bush junior en 2003 et depuis les révélations d’Edward Snowden sur l’espionnage systématique pratiqué par la NSA. Les liens commerciaux avec la Russie et la Chine se sont considérablement accrus, accroissement qui permettait, jusqu’il y a peu de temps, le maintien de l’opulence allemande, assorti de l’espoir de voir celle-ci se consolider et se perpétuer. Ce lent glissement de l’Allemagne, cœur industriel et territorial du sous-continent européen, vers un Est eurasien très vaste, explique sans nul doute les attaques qu’elle subit depuis le printemps 2015. Par ailleurs, des stratégistes de l’ombre veillent à créer un espace pro-occidental, agité ou non de turbulences, entre l’Allemagne et la Russie que l’on baptisera pompeusement « Intermarium ». Cet « Intermarium », cet entre-deux-mers entre la Baltique et la Mer Noire, est la ré-activation d’un projet concocté à Londres pendant la seconde guerre mondiale par les gouvernements polonais et tchèque en exil, avec la bénédiction de Churchill, que l’alliance avec Staline avait rendu nul et non avenu : on a sacrifié, à Londres, les velléités d’indépendance polonaises et tchèques pour pouvoir exploiter à fond la chair à canon soviétique. Moscou ne voulait pas de ce bloc polono-tchèque, même à un moment où la guerre contre l’Allemagne hitlérienne atteignait un paroxysme inégalé.

Du « Cordon sanitaire » de Lord Curzon à l’Intermarium

Même si l’on peut considérer que ce projet d’un Intermarium n’est pas, a priori, une mauvaise idée en soi, qu’il est une application actuelle de projets géopolitiques très anciens, visant toujours à relier les mers du nord à celles du sud parce l’Europe, petite presqu’île à l’ouest de la très grande Eurasie, est géographiquement constituée de trois axes nord/sud : celui qui va de la Mer du Nord au bassin occidental de la Méditerranée (l’espace lotharingien du partage de Verdun en 843), celui envisagé mais non réalisé au moyen-âge par le roi de Bohème Ottokar II Premysl qui va de la Baltique à l’Adriatique (de Stettin à Venise ou Trieste, cités aujourd’hui reliées par une voie de chemin de fer directe et rapide) et, enfin, l’axe dit « gothique », reliant depuis les Goths, bousculés par les Huns, la Baltique à la Mer Noire et à l’Egée, au bassin oriental de la Méditerranée. Aujourd’hui, les stratégistes ennemis de toute vigueur européenne et de toute synergie euro-russe, veulent constituer un Intermarium, sur l’ancien axe gothique, qui serait une résurrection du « cordon sanitaire » de Lord Curzon, destiné à empêcher toute influence de l’Allemagne et de ses dynamismes sur la Russie, posée depuis le géopolitologue Halford John Mackinder comme le « cœur du monde » mais un « cœur de monde » qui ne peut être optimalement activé que par une forte injection d’énergie allemande. Toute alliance germano-russe étant, dans cette optique, considérée comme irrémédiablement invincible, invincibilité qu’il faut toujours combattre et réduire à néant, avant même qu’elle n’émerge sur la scène internationale.

La submersion démographique que subit l’Allemagne depuis les derniers mois de l’année 2015, qui provoquera des troubles civils et ruinera le système social exemplaire de la République Fédérale, qui compte déjà plus de 12 millions de pauvres, a été plus que probablement téléguidée depuis certaines officines de subversion : plusieurs observateurs ont ainsi constaté que les nouvelles alarmantes sur la présence de migrants délinquants en Allemagne viennent de serveurs basés aux Etats-Unis ou en Angleterre, de même que les tweets ou autres messages sur Facebook incitant les migrants à commettre des déprédations ou des viols ou, inversement, incitant les Allemands à manifester contre la submersion démographique ou contre la Chancelière Merkel. Le conflit civil semble être fabriqué de toutes pièces, avec, au milieu du flot des réfugiés, l’armée de réserve du système, composée de djihadistes qui combattent le régime baathiste syrien ou le pouvoir chiite irakien ou l’armée russe en Tchétchénie mais se recyclent en Europe pour déborder les polices des Etats de l’UE en menant la guerre planétaire selon d’autres méthodes.

Spykman, les « rimlands » et l’endiguement

Si la submersion de l’Allemagne a pour but essentiel de briser les potentialités immenses d’un tandem germano-russe, elle vise aussi, bien sûr, à ruiner les bonnes relations économiques entre l’Allemagne et la Chine, d’autant plus que les chemins de fer allemands, la Deutsche Bundesbahn, sont partie prenante dans la construction des voies de trains à grande vitesse entre Hambourg et Shanghai. L’Allemagne et, partant, les pays du Benelux, sont fortement dépendants du commerce avec la Chine. Le but de l’hegemon est donc de briser à tout prix ces synergies et ces convergences. Affirmer cela n’est pas l’expression d’un complotisme découlant d’une mentalité obsidionale mais bel et bien un constat, tiré d’une analyse de l’histoire contemporaine : la réalisation du Transsibérien russe sous l’impulsion du ministre Witte a entraîné la théorisation et la mise en pratique de la stratégie de l’endiguement par Halford John Mackinder d’abord, par son disciple hollando-américain Nicholas Spykman ensuite. Sans Mackinder et Spykman, les Etats-Unis n’auraient sans doute jamais élaboré leur géostratégie planétaire visant à rassembler des alliances hétéroclites, parfois composées d’ennemis héréditaires, sur les franges du grand continent eurasien, avec l’OTAN de l’Islande à la frontière perse, le CENTO du Bosphore à l’Indus et l’OTASE en Asie du Sud-Est.

Si la submersion de l’Allemagne a pour but essentiel de briser les potentialités immenses d’un tandem germano-russe, elle vise aussi, bien sûr, à ruiner les bonnes relations économiques entre l’Allemagne et la Chine, d’autant plus que les chemins de fer allemands, la Deutsche Bundesbahn, sont partie prenante dans la construction des voies de trains à grande vitesse entre Hambourg et Shanghai. L’Allemagne et, partant, les pays du Benelux, sont fortement dépendants du commerce avec la Chine. Le but de l’hegemon est donc de briser à tout prix ces synergies et ces convergences. Affirmer cela n’est pas l’expression d’un complotisme découlant d’une mentalité obsidionale mais bel et bien un constat, tiré d’une analyse de l’histoire contemporaine : la réalisation du Transsibérien russe sous l’impulsion du ministre Witte a entraîné la théorisation et la mise en pratique de la stratégie de l’endiguement par Halford John Mackinder d’abord, par son disciple hollando-américain Nicholas Spykman ensuite. Sans Mackinder et Spykman, les Etats-Unis n’auraient sans doute jamais élaboré leur géostratégie planétaire visant à rassembler des alliances hétéroclites, parfois composées d’ennemis héréditaires, sur les franges du grand continent eurasien, avec l’OTAN de l’Islande à la frontière perse, le CENTO du Bosphore à l’Indus et l’OTASE en Asie du Sud-Est.

Finalement, ces stratégies de l’endiguement sont une application de la fameuse « Doctrine de Monroe », dite de « l’Amérique aux Américains ». Derrière cette apparente revendication d’indépendance se camouflait une volonté de soumettre totalement l’Amérique ibérique au bon vouloir des Etats-Unis. Mais elle s’opposait aussi à la terrible menace qu’aurait pu faire peser sur le continent américain une Sainte-Alliance européenne inébranlable qui s’étendait de l’Atlantique Nord au Pacifique, puisque l’empire du Tsar Alexandre Ier en faisait partie. Cette Sainte-Alliance aurait parfaitement pu défendre les intérêts espagnols dans les Amériques ou les européaniser. A l’époque, la Russie avait une frontière commune avec l’Espagne en… Californie, à hauteur du poste russe de Fort Ross, abandonné seulement en 1842. Le Vieux Monde européen était uni –mais cette union n’allait durer qu’une petite quinzaine d’années- tandis que le Nouveau Monde américain était fragmenté. La Sainte-Alliance, pour le Nouveau Monde et pour les Etats-Unis, encore en gestation mais sûrs de pouvoir mener à terme une mission civilisatrice déduite de leur idéologie religieuse puritaine, constituait par voie de conséquence un double danger : celui de perpétuer le morcellement politique du Nouveau Monde au bénéfice de l’Euro-Russie et celui de se maintenir comme une unité indissoluble et de contrôler le monde pour le très long terme.

« Doctrine de Monroe » et pratique de la table rase

La « Doctrine de Monroe » est donc un rejet de l’Europe et des vieilles civilisations qu’elle représentait, de même qu’un rejet malsain et pervers de toute civilisation ancienne, quelle qu’elle soit, et, surtout, de toute grande profondeur temporelle : là, les délires puritains des sectes protestantes farfelues hostiles à la culture classique gréco-latine de l’Europe catholique ou même anglicane-élisabéthaine, rejoignait les folies de certains avatars incontrôlés de l’idéologie des Lumières. La conjonction de ces deux formes de folie et de nuisance idéologique, qui sévit toujours aujourd’hui, génère un fantasme criminel de destruction systématique d’acquis positifs et de legs historiques.

La « Doctrine de Monroe » est donc un rejet de l’Europe et des vieilles civilisations qu’elle représentait, de même qu’un rejet malsain et pervers de toute civilisation ancienne, quelle qu’elle soit, et, surtout, de toute grande profondeur temporelle : là, les délires puritains des sectes protestantes farfelues hostiles à la culture classique gréco-latine de l’Europe catholique ou même anglicane-élisabéthaine, rejoignait les folies de certains avatars incontrôlés de l’idéologie des Lumières. La conjonction de ces deux formes de folie et de nuisance idéologique, qui sévit toujours aujourd’hui, génère un fantasme criminel de destruction systématique d’acquis positifs et de legs historiques.

La « Doctrine de Monroe », bien davantage que les socialismes messianiques qui pointaient à l’horizon avec la maturation des idées de Karl Marx, est donc une pratique perverse et sournoise de la table rase que tente de parachever de nos jours le néolibéralisme, né aux Etats-Unis à partir de la fin des années 1960 : toute démarche eurasiste constitue donc une révolte contre ce projet d’arasement total, représente une défense des vieilles civilisations, des traditions primordiales, et une revendication du primat de toute profondeur temporelle par rapport à des innovations-élucubrations inventées par des iconoclastes avides de pouvoir absolu, un pouvoir total qui ne peut s’exercer que sur des masses amorphes et amnésiques.

Face aux avatars actualisés de la « Doctrine de Monroe », qui est passée d’une défense affichée de l’autonomie des Etats américains et des Etats créoles de l’Amérique ibérique à la volonté de contrôler les rives atlantiques et pacifiques qui font face à la bi-océanité étatsunienne, l’eurasisme bien compris vise, au contraire, à éradiquer les blocages et fermetures que génèrent les pratiques géopolitiques et la pactomanie américaines sur le continent eurasien, d’abord en Europe et en Asie. Ce rejet des verrouillages incapacitants induit tout naturellement la promotion volontaire d’une politique grande-continentale d’ouvertures rationnelles aux flux qui vivifient et ont jadis vivifié les territoires eurasiatiques.

Ce volontarisme eurasiste réduit à néant le discours stratégique né de la distinction opérée par Karl Popper entre sociétés ouvertes et sociétés fermées, où les Etats-Unis se posent comme les promoteurs et les garants des « sociétés ouvertes », tout en pratiquant des fermetures calamiteuses dues à la pactomanie qu’ils pratiquent sur les rimlands eurasiens de l’Europe à l’Indochine. A l’Eurasie des fermetures, produit de la Guerre Froide, doit succéder une Eurasie des communications sans entraves entre l’Europe et la Chine : le monde réellement fermé est donc celui qu’ont établi les tenants de la « société ouverte » (de Popper et de Soros), tandis que l’Eurasie des communications ouvertes est le fait en gestation de ceux qui sont accusés, dans les médias dominants, d’être les adeptes des « sociétés fermées », d’hégélienne ou de marxienne mémoires. Sur cette contradiction flagrante, mais ignorée délibérément dans les discours médiatiques occidentaux, reposent toutes les ambigüités de la propagande, tout le flou incapacitant dans lequel marinent nos décideurs et nos concitoyens.

Trois ouvertures historiques

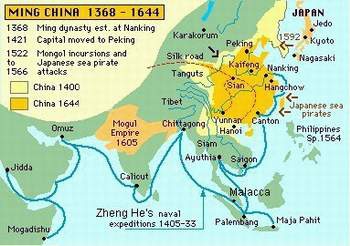

Trois ouvertures historiques en Eurasie doivent nous servir de modèles : l’Empire de Kubilaï Khan, visité par Marco Polo, qui ne s’opposait pas à la libre circulation des biens, des caravanes et des idées, contrairement aux verrouillages seldjouk et ottoman ; les rapports espérés entre la Chine et l’Europe quand le jésuite Ferdinand Verbist exerçait son haut mandarinat en Chine au XVIIe siècle ; l’alliance informelle sous Louis XVI entre la France, l’Autriche et la Russie, où la première veillait à contrôler l’Atlantique Nord, les seconde et troisième à faire sauter le verrou ottoman. A ces trois modèles, il convient d’ajouter la notion de syncrétisme religieux, porté par une volonté de ne rien éradiquer, d’opérer des fusions fécondes et de générer de l’harmonie : c’était la préoccupation principale d’Alexandre Ier après les tumultes révolutionnaires et napoléoniens ; c’est la notion de « djadidisme » qui prévaut aujourd’hui dans l’islam de la Fédération de Russie, notamment au Tatarstan où se situe le grand centre spirituel de Kazan ; le djadidisme s’interdit de chercher querelle avec les autres confessions, contrairement aux formes diverses et pernicieuses qu’un certain islam a prises ailleurs dans le monde, soit le salafisme, le wahhabisme ou le mouvement des Frères musulmans, formes virulentes aujourd’hui en Occident et génératrices à court terme de graves conflits civils ; ces formes inacceptables ont cherché à s’implanter en Russie, à partir de la période de « smuta » que fut le premier gouvernement d’Eltsine : elles ont échoué ; ce n’est qu’à Kazan et au Tatarstan qu’un véritable « euro-islam » s’est constitué ; il n’y en a pas d’autres possibles et les constructions boiteuses d’un Tarik Ramadan, dont les prédécesseurs et collatéraux ont été financés et soutenus par les services américains, ne sont que des déguisements maladroits pour gruger les Occidentaux écervelés. Outre la volonté de convergence religieuse du Tsar Alexandre Ier, outre le syncrétisme centre-asiatique promu en Asie centrale au temps de la domination mongole, outre le djadidisme actuel de la Fédération de Russie, nous ne voyons guère d’autres filons religieux traditionnels qui tiennent vraiment compte de la profondeur temporelle voire immémoriale, nécessaire à l’établissement de véritables ferveurs structurantes, indispensables pour contrer les déliquescences du monde moderne. L’ouverture des communications, le rejet des véritables sociétés fermées par les intransigeances occidentales ou wahhabites/salafistes implique l’émergence d’un syncrétisme harmonisateur qui ne raisonne pas par exclusion (« ou bien… ou bien… ») mais par inclusion (« et… et… »).

Quelques mots sur l’Inde

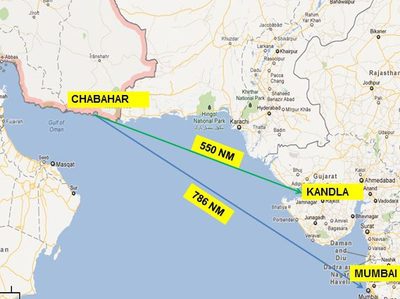

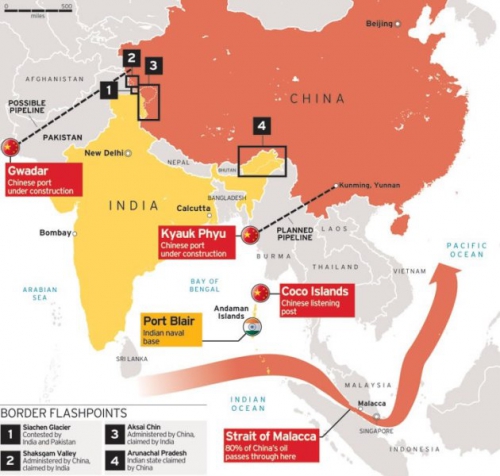

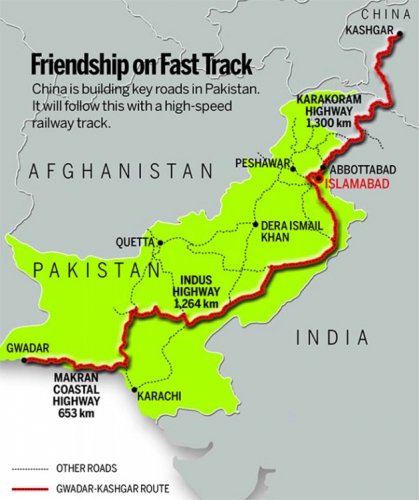

Ma démonstration, ici, que j’annonçais d’emblée « succincte » et incomplète, ne peut donc prétendre à l’exhaustivité. Mais elle ne saurait omettre d’évoquer l’Inde dans ce survol des convergences eurasiatiques. Depuis son indépendance en 1947, l’Inde est traditionnellement alliée à la Russie, hostile à la Chine, contre laquelle elle a mené une guerre sur les hauteurs de l’Himalaya. La volonté de convergence eurasiatique s’occupe de gommer ce conflit. Les régions himalayennes contestées permettraient, une fois pacifiées, un passage entre l’Inde et les territoires anciennement soviétiques et entre l’Inde et la Chine. L’affaire se corse parce que la Chine, du temps de son conflit avec l’Inde, avait soutenu le Pakistan pour obtenir un port sur l’Océan Indien et des voies de communications entre ces installations portuaires avec la région chinoise de Kachgar, via le tracé en montagne dit de « Karakoroum », partant d’Islamabad pour rejoindre le poste-frontière d’Aliabad au Cachemire. Le gros problème est que l’Inde revendique cette partie du Cachemire pour avoir un lien avec le Tadjikistan ex-soviétique. Par ailleurs, comme le soulignent deux historiens insignes des faits indiens, le Britannique Ian Morris et l’Indien Pankaj Mishra, l’Inde souhaite consolider la cohésion du commerce entre le Golfe et la Mer Rouge d’une part, le Golfe du Bengale et les eaux de l’Asie du Sud-Est, d’autre part. L’objectif géopolitique de l’Inde est d’affirmer sa présence dans l’Océan Indien, surtout dans l’archipel d’Andaman et dans les Iles Nicobar, face aux côtes thaïlandaises. Cette volonté entend créer un chapelet de relais entre la Mer Rouge et l’Insulinde, le même que celui voulu par la Chine, qui le prolongerait jusqu’à ses propres ports du Pacifique, ce qui explique le conflit actuel pour les îles et îlots, naturels ou artificiels, dans la Mer de Chine du Sud. La consolidation de ce chapelet de relais maritimes, sans possibilité de le couper ou de le fragmenter, rendrait à l’ensemble des Etats d’Eurasie une autonomie commerciale et navale sur son flanc sud, tandis que la Russie rétablirait les communications par l’Arctique, de Hambourg au Japon. Une Egypte militaire, débarrassée du danger que représentent les Frères musulmans et les autres adversaires des syncrétismes féconds, ouvrirait, par Suez, l’espace méditerranéen au commerce eurasien, réalisant du même coup le vœu des Génois et des Vénitiens de notre moyen-âge, tout en isolant la Turquie, du moins si cette dernière entend encore jouer le rôle d’un verrou et non pas d’un pont, comme le souhaitent les Chinois qui leur proposent la construction, entre l’Iran et l’Egée, d’un chemin de fer les liant tout à la fois à l’Asie et à l’Europe. Erdogan se trouve devant un choix : abandonner les « otâneries » et les sottises fondamentalistes ou renouer avec un laïcisme et un syncrétisme turcs qui n’apporteraient que des bienfaits.

Ma démonstration, ici, que j’annonçais d’emblée « succincte » et incomplète, ne peut donc prétendre à l’exhaustivité. Mais elle ne saurait omettre d’évoquer l’Inde dans ce survol des convergences eurasiatiques. Depuis son indépendance en 1947, l’Inde est traditionnellement alliée à la Russie, hostile à la Chine, contre laquelle elle a mené une guerre sur les hauteurs de l’Himalaya. La volonté de convergence eurasiatique s’occupe de gommer ce conflit. Les régions himalayennes contestées permettraient, une fois pacifiées, un passage entre l’Inde et les territoires anciennement soviétiques et entre l’Inde et la Chine. L’affaire se corse parce que la Chine, du temps de son conflit avec l’Inde, avait soutenu le Pakistan pour obtenir un port sur l’Océan Indien et des voies de communications entre ces installations portuaires avec la région chinoise de Kachgar, via le tracé en montagne dit de « Karakoroum », partant d’Islamabad pour rejoindre le poste-frontière d’Aliabad au Cachemire. Le gros problème est que l’Inde revendique cette partie du Cachemire pour avoir un lien avec le Tadjikistan ex-soviétique. Par ailleurs, comme le soulignent deux historiens insignes des faits indiens, le Britannique Ian Morris et l’Indien Pankaj Mishra, l’Inde souhaite consolider la cohésion du commerce entre le Golfe et la Mer Rouge d’une part, le Golfe du Bengale et les eaux de l’Asie du Sud-Est, d’autre part. L’objectif géopolitique de l’Inde est d’affirmer sa présence dans l’Océan Indien, surtout dans l’archipel d’Andaman et dans les Iles Nicobar, face aux côtes thaïlandaises. Cette volonté entend créer un chapelet de relais entre la Mer Rouge et l’Insulinde, le même que celui voulu par la Chine, qui le prolongerait jusqu’à ses propres ports du Pacifique, ce qui explique le conflit actuel pour les îles et îlots, naturels ou artificiels, dans la Mer de Chine du Sud. La consolidation de ce chapelet de relais maritimes, sans possibilité de le couper ou de le fragmenter, rendrait à l’ensemble des Etats d’Eurasie une autonomie commerciale et navale sur son flanc sud, tandis que la Russie rétablirait les communications par l’Arctique, de Hambourg au Japon. Une Egypte militaire, débarrassée du danger que représentent les Frères musulmans et les autres adversaires des syncrétismes féconds, ouvrirait, par Suez, l’espace méditerranéen au commerce eurasien, réalisant du même coup le vœu des Génois et des Vénitiens de notre moyen-âge, tout en isolant la Turquie, du moins si cette dernière entend encore jouer le rôle d’un verrou et non pas d’un pont, comme le souhaitent les Chinois qui leur proposent la construction, entre l’Iran et l’Egée, d’un chemin de fer les liant tout à la fois à l’Asie et à l’Europe. Erdogan se trouve devant un choix : abandonner les « otâneries » et les sottises fondamentalistes ou renouer avec un laïcisme et un syncrétisme turcs qui n’apporteraient que des bienfaits.

La Chine, le chapelet de relais et l’Océan Pacifique

La consolidation du chapelet de relais maritimes de Cadix à Shanghai permettrait à l’Europe, à son centre germanique et à la Russie de se projeter vers le Pacifique, impératif géopolitique qu’avaient compris des hommes aussi différents que Louis XVI, La Pérouse, Lord Kitchener et Karl Haushofer. Kitchener prévoyait, dans une conversation avec Haushofer, que les puissances européennes (Royaume-Uni compris !) qui n’auraient pas de bases solides dans le Pacifique, seraient irrémédiablement condamnées au déclin. Haushofer avait tiré la conclusion suivante : l’Allemagne, présente dans les Mariannes, suite au retrait espagnol, avait des chances ce consolider ses positions mais, dans la foulée, rencontrait automatiquement l’hostilité des Etats-Unis qui cherchaient -depuis 1848, date à laquelle ils acquièrent l’atout géostratégique majeur de la bi-océanité- à dominer le marché chinois, quantitativement le plus important à l’époque, comme de nos jours. Le destin a décidé qu’après la rétrocession des Mariannes à Tokyo par l’Allemagne au Traité de Versailles de 1919, la lutte pour le Pacifique se déroulerait entre un Japon, agrandi de cette immense Micronésie, et les Etats-Unis, maîtres des Philippines depuis leur victoire sur l’Espagne en 1898. La seconde guerre mondiale donnera aux Etats-Unis la maîtrise absolue du Pacifique, atout qui scelle leur hégémonisme planétaire. Aujourd’hui, le télescopage géopolitique ne s’effectue pas entre une puissance européenne présente au centre du Pacifique (comme le furent successivement l’Espagne puis l’Allemagne de Guillaume II) ou le Japon shintoïste et les Etats-Unis, mais entre les Etats-Unis et la Chine, où cette dernière est endiguée par une chaîne de petites puissances (Japon vaincu en 1945 compris) entièrement contrôlées par le système des alliances américaines. Cette chaîne vise à empêcher la Chine de s’élancer vers le large et à doter les Etats-Unis des bases insulaires nécessaires pour harceler, le cas échéant, les convois et l’acheminement d’hydrocarbures vers les ports du littoral pacifique chinois, pour rendre précaire cette ligne vitale de communications maritimes.

Chine : double stratégie maritime et continentale

L’application de cette stratégie de harcèlement en Mer de Chine du Sud pourra soit étouffer la Chine soit épuiser les Etats-Unis (où le taux de pauvreté augmente dangereusement). La Chine avait jadis deux stratégies possibles : une stratégie continentale, d’expansion vers le Tibet et le Turkestan/Sinkiang, qui ne dérangeait pas les Américains puisqu’elle inquiétait les Soviétiques. Ou une stratégie maritime, à laquelle le maoïsme avait renoncé, permettant, à partir de 1972, de nouer une alliance informelle avec les Etats-Unis. Aujourd’hui, la Chine cherche à échapper à son endiguement par une double stratégie : à la fois continentale, vers le Kazakhstan et au-delà, par le truchement de chemins de fer trans-asiatiques, et maritime, par la consolidation d’un chapelet de relais dans le Pacifique et l’Océan Indien, dans la mesure du possible en harmonie avec son concurrent potentiel, l’Inde. L’Europe, centrée sur l’Allemagne, et, partant, le tandem euro-russe ont donc intérêt à assurer des projections sans obstacles vers l’Inde et la Chine, tout en évitant qu’une puissance comme le Japon continue à faire partie de la barrière maritime américaine. Or le Japon se débat de nos jours, coincé qu’il est dans le dilemme suivant : éviter l’absorption par la Chine, ce qui serait humiliant, eu égard aux conflits sino-japonais depuis 1895 et éviter l’inféodation perpétuelle à une puissance étrangère à l’espace asiatique comme les Etats-Unis. Attiser les contentieux sino-japonais va dans le sens des intérêts de l’hegemon. Harmoniser les rapports futurs entre le Céleste Empire et l’Empire du Soleil Levant est une tâche des cénacles eurasistes partout dans le monde.

La pacification des rapports entre toutes les composantes de la masse continentale eurasiste (flanquée du Japon) permettra l’avènement de ce que Jean Parvulesco appelait l’ « Empire eurasiatique de la Fin », dans toute son acception eschatologique. Cela signifie-t-il une « fin de l’histoire », un peu comme celle qu’avait envisagée Francis Fukuyama au moment de l’effondrement du système soviétique et de la plongée de la Russie dans la « smuta » eltsinienne ? Non, Fukuyama a déjà été réfuté par les faits : l’histoire ne s’est pas arrêtée, bien au contraire, elle s’est accélérée. Cet « Empire eurasiatique de la Fin » signifierait essentiellement la fin des divisions rédhibitoires, des interventions belligènes potentielles, inutiles et néfastes que déploraient Carl Schmitt ou Otto Hoetzsch. Ce serait le retour définitif de l’alliance informelle du XVIIIe siècle ou, enfin, un retour de la Sainte-Alliance, de l’Atlantique au Pacifique.

Douze pistes pour une « pax eurasiatica »

J’emprunte ma conclusion au géopolitologue italien Alfonso Piscitelli qui suggère une douzaine de pistes pour aboutir à cette pax eurasiatica :

- Ne jamais renoncer à la coopération énergétique, ce qui signifie poursuivre envers et contre tout la politique des gazoducs North et South Stream, selon les modalités fixées par l’ancien Chancelier allemand Gerhard Schröder.

- Re-nationaliser les sources énergétiques pour les soustraire aux fluctuations erratiques d’un libéralisme mal conçu.

- Parier sur les BRICS et s’acheminer progressivement vers un « Euro-BRICS ».

- Viser des continuités politiques sur un plus long terme en généralisant les régimes présidentiels, façon gaullienne, avec élection directe du Président comme en France et en Russie, assorti d’un re-dimensionnement des pouvoirs non élus (des potestates indirectae, des pouvoirs indirects, dont la nuisance a été soulignée par Carl Schmitt). Le but final est un retour à une sorte de « monarchie populaire ».

- Proposer un islam modéré, calqué sur le djadidisme soviétique, russe et tatar, compatible, dans le monde arabe, avec des régimes militaires et civils détachés des extrémismes religieux, comme ce fut le cas dans l’Egypte nassérienne, dans l’Iran du Shah, dans la Libye de Khadafi et dans les régimes baathistes de Syrie et d’Irak. Toute pensée politique exprimée par les musulmans des diasporas doit s’inspirer de ces formes de panarabisme, de personnalisme baathiste, de kémalisme ou de valorisation de la chose militaire et non plus de délires salafistes ou wahhabites qui n’ont apporté que le chaos et la misère dans le monde arabo-musulman.

- Favoriser l’intégration militaire de l’Europe, puis de l’Europe et de la Russie et, enfin de l’Euro-Russie et des BRICS, le tout évidemment hors de cette structure vermoulue qu’est l’OTAN qui ne peut conduire qu’au ressac européen, comme on l’observe très nettement aujourd’hui.

- Plaider pour un monde multipolaire contre l’unipolarité voulue par Washington, selon les axes conceptuels mis au point par les équipes eurasistes russe autour d’Alexandre Douguine, Natella Speranskaya et Leonid Savin.

- Travailler à une réglementation positive des migrations, comme l’ont préconisé le Président Poutine dans son discours à la Douma, le 4 février 2013, et Philippe Migault, quand il a plaidé pour une entente euro-russe en Méditerranée, sur fond du triple enjeu grec, syrien et cypriote.

- Favoriser une politique familiale traditionnelle comme en Russie pour pallier le ressac démographique européen.

- Entamer un dialogue culturel inter-européen qui inclut les linéaments de la pensée organique russe, comme l’avaient souhaité des figures allemandes comme l’éditeur Eugen Diederichs dès la fin du XIXe siècle ou le Prof. Otto Hoetzsch, grand artisan d’un réel dialogue germano-russe ou euro-russe de l’ère wilhelminienne à Weimar et de Weimar à l’ère nationale-socialiste, malgré l’hostilité du régime en place.

- Entamer un dialogue entre civilisations et grandes traditions religieuses, comme le voulait le Tsar Alexandre Ier et selon certains axes préconisés par les leaders religieux iraniens, comme le Président Rohani.

- Revenir à l’idée universelle romaine. L’eurasisme est un projet impérial, pan-impérial, qui est une actualisation des pouvoirs impériaux romain (et donc byzantin, allemand et russe), perse et chinois.

J’ajouterai à cette douzaine de pistes une treizième, celle qui doit déboucher sur une dé-dollarisation définitive de l’économie mondiale. Quelques initiatives, surtout au départ des BRICS, ont déjà marqué des points dans ce sens.

Pour réaliser ce programme suggéré par Alfonso Piscitelli, il convient évidemment d’éviter deux écueils :

- Présenter ces pistes sous la forme d’un discours d’excité, truffé de rêveries ridicules, risquant de faire interpréter toute démarche eurasiste comme un irréalisme extrémiste, lequel serait automatiquement discrédité dans les médias.

- Eviter les polémiques gratuites contre les autres sujets de l’histoire européenne : pas de russophobie ou de germanophobie anachroniques, pas de sinophobie rappelant les discours sur le « péril jaune », etc. Et pas davantage de discours anti-grecs, sous prétexte que la Grèce aurait mal gérée ses finances, ou de discours hispanophobes, prenant le relais des « légendes noires » colportées contre l’Espagne impériale par les protestants dès la XVIe siècle.

Vous constaterez qu’il y a un immense chantier devant nous. Au travail !

Robert Steuckers,

Forest-Flotzenberg, septembre 2015, février 2016.

Bibliographie :

- Jean-Pierre ALLEGRET, « Les relations yuan-dollar : de la « guerredes monnaies » à la gouvernance monétaire et financière internationale », Diplomatie, n°71, novembre-décembre 2014.

- Fernando ARANCON, La Union economica euroasiàtica o la reconstruccion del spacio postsoviético, http://elordenmundial.com, 5 avril 2015.

- Stefan AUST & Adrian GEIGES, Mit Konfuzius zur Weltmacht – Das chinesische Jahrhundert, Quadriga Verlag, Berlin, 2012.