India's only communalist

A short biography of Sita Ram Goel

Ex; http://koenraadelst.voiceofdharma.com/

Koenraad Elst

1. Is there a communalist in the hall ?

A lot of people in India and abroad talk about communalism, often in grave tones, describing it as a threat to secularism, to regional and world peace. But can anyone show us a communalist? If we look more closely into the case of any so-called communalist, we find that he turns out to be something else.

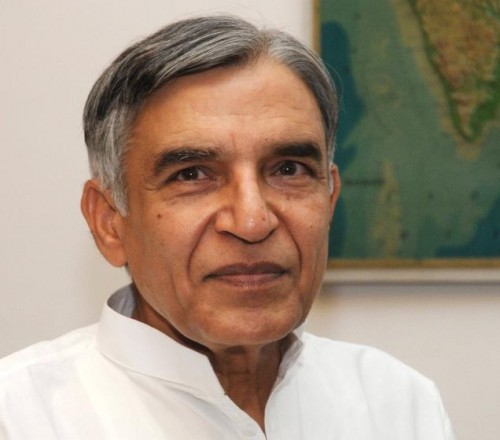

Could Syed Shahabuddin be a communalist? After all, he played a key role in the three main "Muslim communalist" issues of recent years: the Babri Masjid campaign, the Shah Bano case and the Salman Rushdie affair (it is he who got The Satanic Verses banned in September 1988). Surely, he must be India's communalist par excellence? Wrong: if you read any page of any issue of Shahabuddin's monthly Muslim India, you will find that he brandishes the notion of "secularism" as the alpha and omega of his politics, and that he directs all his attacks against Hindu "communalism". The same propensity is evident in the whole Muslim "communalist" press, e.g. the Jamaat-i Islami weekly Radiance. Moreover, on Muslim India's editorial board, you find articulate secularists like Inder Kumar Gujral, Khushwant Singh and the late P.N. Haksar.

Could Syed Shahabuddin be a communalist? After all, he played a key role in the three main "Muslim communalist" issues of recent years: the Babri Masjid campaign, the Shah Bano case and the Salman Rushdie affair (it is he who got The Satanic Verses banned in September 1988). Surely, he must be India's communalist par excellence? Wrong: if you read any page of any issue of Shahabuddin's monthly Muslim India, you will find that he brandishes the notion of "secularism" as the alpha and omega of his politics, and that he directs all his attacks against Hindu "communalism". The same propensity is evident in the whole Muslim "communalist" press, e.g. the Jamaat-i Islami weekly Radiance. Moreover, on Muslim India's editorial board, you find articulate secularists like Inder Kumar Gujral, Khushwant Singh and the late P.N. Haksar.

For the same reason, any attempt to label the All-India Muslim League as communalist would be wrong. True, it is the continuation of the party which achieved the Partition of India along communal lines. Yet, emphatically secularist parties like the Congress Party and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) have never hesitated to include the Muslim League in coalitions governing the state of Kerala. No true communalist would get such a chance.

On the Hindu side then, at least the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, "National Volunteer Corps") could qualify as "communalist"? Certainly, it is called just that by all its numerous enemies. But then, when you look through any issue of its weekly Organiser, you will find it brandishing the notion of "positive" or "genuine secularism", and denouncing "pseudo-secularism", i.e. minority communalism. Moreover, in order to prove its non-communal character, it even calls itself and its affiliated organizations (trade-union, student organization, political party etc.) "National" or "Indian" rather than "Hindu". The allied political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, "Indian People's Party"), shows off the large number of Muslims among its cadres to prove how secular and non-communal it is. Even the Shiv Sena shows off its token Muslims. No, for full-blooded communalists, we have to look elsewhere.

There is only one man in India whom I have ever known to say: "I am a (Hindu) communalist." To an extent, this is in jest, as a rhetorical device to avoid the tangle in which RSS people always get trapped: being called "communalist!" and then spending the rest of your time trying to prove to your hecklers what a good secularist you are. But to an extent, it is because he accepts at least one definition of "communalism" as applying to himself, esp. to his view of India's history since the 7th century. Many historians try to prove their "secularism" by minimizing religious adherence as a factor of conflict in Indian history, and explaining so-called religious conflicts as merely a camouflage for socio-economic conflicts. By contrast, the historian under consideration accepts, and claims to have thoroughly documented, the allegedly "communalist" view that the major developments in medieval and modern Indian history can only be understood as resulting from an intrinsic hostility between religions.

Unlike the Hindutva politicians, he does not seek the cover of "genuine secularism". While accepting the notion that Hindu India has always been "secular" in the adapted Indian sense of "religiously pluralistic", he does not care for slogans like the Vishva Hindu Parishad's advertisement "Hindu India, secular India". After all, in Nehruvian India the term "secular" has by now acquired a specific meaning far removed from the original European usage, and even from the above-mentioned Indian adaptation. If Voltaire, the secularist par excellence, were to live in India today and repeat his attacks on the Church, echoing the Hindutva activists in denouncing the Churches' grip on public life in christianized pockets like Mizoram and Nagaland, he would most certainly be denounced as "anti-minority" and hence "anti-secular".

In India, the term has shed its anti-Christian bias and acquired an anti-Hindu bias instead, a phenomenon described by the author under consideration as an example of the current "perversion of India's political parlance". Therefore, he attacks the whole Nehruvian notion of "secularism" head-on, e.g. in the self-explanatory title of his Hindi booklet Saikyularizm: râshtradroha kâ dûsra nâm ("Secularism: the Alternative Name for Treason"). The name of India's only self-avowed communalist is Sita Ram Goel.

2. Sita Ram Goel as an anti-Communist

Sita Ram Goel was born in 1921 in a poor family (though belonging to the merchant Agrawal caste) in Haryana. As a schoolboy, he got acquainted with the traditional Vaishnavism practised by his family, with the Mahabharata and the lore of the Bhakti saints (esp. Garibdas), and with the major trends in contemporary Hinduism, esp. the Arya Samaj and Gandhism. He took an M.A. in History in Delhi University, winning prizes and scholarships along the way. In his school and early university days he was a Gandhian activist, helping a Harijan Ashram in his village and organizing a study circle in Delhi.

In the 1930s and 40s, the Gandhians themselves came in the shadow of the new ideological vogue: socialism. When they started drifting to the Left and adopting socialist rhetoric, S.R. Goel decided to opt for the original rather than the imitation. In 1941 he accepted Marxism as his framework for political analysis. At first, he did not join the Communist Party of India, and had differences with it over such issues as the creation of the religion-based state of Pakistan, which was actively supported by the CPI but could hardly earn the enthusiasm of a progressive and atheist intellectual. He and his wife and first son narrowly escaped with their lives in the Great Calcutta Killing of 16 August 1946, organized by the Muslim League to give more force to the Pakistan demand.

In the 1930s and 40s, the Gandhians themselves came in the shadow of the new ideological vogue: socialism. When they started drifting to the Left and adopting socialist rhetoric, S.R. Goel decided to opt for the original rather than the imitation. In 1941 he accepted Marxism as his framework for political analysis. At first, he did not join the Communist Party of India, and had differences with it over such issues as the creation of the religion-based state of Pakistan, which was actively supported by the CPI but could hardly earn the enthusiasm of a progressive and atheist intellectual. He and his wife and first son narrowly escaped with their lives in the Great Calcutta Killing of 16 August 1946, organized by the Muslim League to give more force to the Pakistan demand.

In 1948, just when he had made up his mind to formally join the Communist Party of India, in fact on the very day when he had an appointment at the party office in Calcutta to be registered as a candidate-member, the Government of West Bengal banned the CPI because of its hand in an ongoing armed rebellion. A few months later, Ram Swarup came to stay with him in Calcutta and converted him as well as his employer, Hari Prasad Lohia, out of Communism. Goel's career as a combative and prolific writer on controversial matters of historical fact can only be understood in conjunction with Ram Swarup's sparser, more reflective writings on fundamental doctrinal issues.

Much later, in a speech before the Yogakshema society, Calcutta 1983, he explained his relation with Ram Swarup as follows: "In fact, it would have been in the fitness of things if the speaker today had been Ram Swarup, because whatever I have written and whatever I have to say today really comes from him. He gives me the seed-ideas which sprout into my articles (...) He gives me the framework of my thought. Only the language is mine. The language also would have been much better if it was his own. My language becomes sharp at times; it annoys people. He has a way of saying things in a firm but polite manner, which discipline I have never been able to acquire." (The Emerging National Vision, p.1.)

S.R. Goel's first important publications were written as part of the work of the Society for the Defence of Freedom in Asia:

· World Conquest in Instalments (1952);

· The China Debate: Whom Shall We Believe? (1953);

· Mind Murder in Mao-land (1953);

· China is Red with Peasants' Blood (1953);

· Red Brother or Yellow Slave? (1953);

· Communist Party of China: a Study in Treason (1953);

· Conquest of China by Mao Tse-tung (1954);

· Netaji and the CPI (1955);

· CPI Conspire for Civil War (1955).

Goel also published the book Blowing up India: Reminiscences of a Comintern Agent by Philip Spratt (1955), who, as an English Comintern agent, had founded the Communist Party of India in 1926. After spending some time in prison as a convict in the Meerut Conspiracy case (1929), Spratt had come under the influence of Mahatma Gandhi, and ended as one of the best-informed critics of Communism.

Then, and all through his career as a polemical writer, the most remarkable feature of Sita Ram Goel's position in the Indian intellectual arena was that nobody even tried to give a serious rebuttal to his theses: the only counter-strategy has always been, and still is, "strangling by silence", simply refusing to ever mention his name, publications and arguments.

An aspect of history yet to be studied is how such anti-Communist movements in the Third World were not at all helped (in fact, often opposed) by Western interest groups whose understanding of Communist ideology and strategy was just too superficial. Most US representatives starkly ignored the SDFA's work, and preferred to enjoy the company of more prestigious (implying: fashionably anti-anti-Communist) opinion makers. Goel himself noted in 1961 about his Western anti-Communist contacts like Freda Utley, Suzanne Labin and Raymond Aron, who were routinely dismissed as bores, querulants or CIA agents: Communism was "opposed only by individuals and groups who have done so mostly at the cost of their reputation (...) A history of these heroes and their endless endeavour has still to be written." (Genesis and Growth of Nehruism, p.212)

3. Sita Ram Goel and the RSS

In the 1950s, Goel was not active on the "communal" battlefield: not Islam or Christianity but Communism was his priority target. Yet, under Ram Swarup's influence, his struggle against communism became increasingly rooted in Hindu spirituality, the way Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's anti-Communism became rooted in Orthodox Christianity. He also co-operated with (but was never a member of) the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, and he occasionally contributed articles on Communism to the RSS weekly Organiser. In 1957 he contested the Lok Sabha election for the Khajuraho constituency as an independent candidate on a BJS ticket, but lost. He was one of the thirty independents fielded as candidates by Minoo Masani in preparation of the creation of his own (secular, rightist-liberal) Swatantra Party.

In the 1950s, Goel was not active on the "communal" battlefield: not Islam or Christianity but Communism was his priority target. Yet, under Ram Swarup's influence, his struggle against communism became increasingly rooted in Hindu spirituality, the way Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's anti-Communism became rooted in Orthodox Christianity. He also co-operated with (but was never a member of) the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, and he occasionally contributed articles on Communism to the RSS weekly Organiser. In 1957 he contested the Lok Sabha election for the Khajuraho constituency as an independent candidate on a BJS ticket, but lost. He was one of the thirty independents fielded as candidates by Minoo Masani in preparation of the creation of his own (secular, rightist-liberal) Swatantra Party.

In that period, apart from the said topical books in English, Goel wrote and published 18 titles in Hindi: 8 titles of fiction and 1 of poetry written by himself; 3 compilations from the Mahabharata and the Tripitaka; and Hindi translations of these 6 books, mostly of obvious ideological relevance:

· The God that Failed, a testimony on Communism by Arthur Koestler, André Gide and other prominent ex-Communists;

· Ram Swarup's Communism and Peasantry;

· Viktor Kravchenko's I Chose Freedom, another testimony by an ex-Communist;

· George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.

· Satyakam Sokratez ("Truth-lover Socrates"), the three Dialogues of Plato centred round Socrates' last days (Apology, Crito and Phaedo);

· Shaktiputra Shivaji, a history of the 17th-century Hindu freedom fighter, originally The Great Rebel by Denis Kincaid.

There is an RSS aspect to this publishing activity. RSS secretary-general Eknath Ranade had asked Goel to educate RSS workers about literature, and to produce some literature in Hindi to this end. The understanding was that the RSS would propagate this literature and organize discussions about it. Once Goel had set up a small publishing outfit and published a few books, he had another meeting with Ranade, who gave him an unpleasant surprise: "Was the RSS created to sell your books?" Fortunately for Goel, his friend Guru Datt Vaidya and son Yogendra Datt included Goel's books in the fund of their own publishing-house, Bharati Sahitya Sadan. This is Goel's own version, and Ranade is not there to defend himself; but Goel's long experience in dealing with the RSS leadership translates into a long list of anecdotes of RSS petty-mindedness, unreliability and lack of proper manners in dealing with fellow-men.

In May 1957, Goel moved to Delhi and got a job with a state-affiliated company, the Indian Cooperative Union, for which he did research and prospection concerning cottage industries. The company also loaned him for a while to the leading Gandhian activist Jayaprakash Narayan, who shared Goel's anti-Communism at least at the superficial level (what used to be called "anti-Stalinism": rejecting the means but not the ends of Communism).

During the Chinese invasion in 1962, some government officials including P.N. Haksar, Nurul Hasan and the later Prime Minister I.K. Gujral, demanded Goel's arrest. But at the same time, the Home Ministry invited him to take a leadership role in the plans for a guerrilla war against the then widely-expected Chinese occupation of eastern India. He made his co-operation conditional on Nehru's abdication as Prime Minister, and nothing ever came of it.

In 1963, Goel had a book published under his own name which he had published in 1961-62 as a series in Organiser under the pen name Ekaki ("solitary"): a critique of Nehru's consistent pro-Communist policies, titled In Defence of Comrade Krishna Menon. An update of this book was published in 1993: Genesis and Growth of Nehruism. The serial in Organiser had been discontinued after 16 installments because Eknath Ranade and A.B. Vajpayee feared that if any harm came to Nehru, the RSS would be accused of having "created the climate", as in the Gandhi murder case.

In it, Goel questioned the current fashion of attributing India's Communist-leaning foreign policy to Defence Minister Krishna Menon, and demonstrated that Nehru himself had been a consistent Communist sympathizer ever since his visit to the Soviet Union in 1927. Nehru had stuck to his Communist sympathies even when the Communists insulted him as Prime Minister with their unbridled scatologism. Nehru was too British and too middle-class to opt for a fully authoritarian socialism, but like many European Leftists he supported just such regimes when it came to foreign policy. Thus, Nehru's absolute refusal to support the Tibetans even at the diplomatic level when they were overrun by the Chinese army ("a Far-Eastern Munich", according to Minoo Masani: Against the Tide, Vikas Publ., Delhi 1981, p.45.), cannot just be attributed to circumstances or the influence of his collaborators: his hand-over of Tibet to Communist China was quite consistent with his own political convictions.

While refuting the common explanation that the pro-Communist bias in Nehru's foreign policy was merely the handiwork of Minister Krishna Menon, Goel also drew attention to the harmfulness of this policy to India's national interests. This critique of Nehru's pro-China policies was eloquently vindicated by the Chinese invasion in October 1962, but it cost Goel his job. He withdrew from the political debate, went into business himself and set up Impex India, a company of book import and export with a modest publishing capacity.

In 1964, RSS general secretary Eknath Ranade invited Goel to lead the prospective Vishva Hindu Parishad, which was founded later that year, but Goel set as his condition that he would be free to speak his own mind rather than act as a mouthpiece of the RSS leadership; the RSS could not accept this, and the matter ended there. Goel's only subsequent involvement in politics was in 1973 when he was asked by the BJS leadership to mediate with the dissenting party leader Balraj Madhok in a last attempt at conciliation (which failed); and when he worked as a member of the think-tank of the Janata alliance before it defeated Indira's Emergency regime in the 1977 elections. As a commercial publisher, he did not seek out the typical "communal" topics, but nonetheless kept an eye on Hindu interests. That is why he published books like Dharampal's The Beautiful Tree (on indigenous education as admiring British surveyors found it in the 19th century, before it was destroyed and replaced with the British or missionary system), Ram Swarup's apology of polytheism The Word as Revelation (1980), K.R. Malkani's The RSS Story (1980) and K.D. Sethna's Karpasa in Prehistoric India (1981; on the chronology of Vedic civilization, implying decisive objections against the Aryan Invasion Theory).

4. Sita Ram Goel as a Hindu Revivalist

In 1981 Sita Ram Goel retired from his business, which he handed over to his son and nephew. He started the non-profit publishing house Voice of India with donations from sympathetic businessmen, and accepted Organiser editor K.R. Malkani's offer to contribute some articles again, articles which were later collected into the first Voice of India booklets.

In 1981 Sita Ram Goel retired from his business, which he handed over to his son and nephew. He started the non-profit publishing house Voice of India with donations from sympathetic businessmen, and accepted Organiser editor K.R. Malkani's offer to contribute some articles again, articles which were later collected into the first Voice of India booklets.

Goel's declared aim is to defend Hinduism by placing before the public correct information about the situation of Hindu culture and society, and about the nature, motives and strategies of its enemies. For, as the title of his book Hindu Society under Siege indicates, Goel claims that Hindu society has been suffering a sustained attack from Islam since the 7th century, from Christianity since the 15th century, this century also from Marxism, and all three have carved out a place for themselves in Indian society from which they besiege Hinduism. The avowed objective of each of these three world-conquering movements, with their massive resources, is diagnosed as the replacement of Hinduism by their own ideology, or in effect: the destruction of Hinduism.

Apart from numerous articles, letters, contributions to other books (e.g. Devendra Swarup, ed.: Politics of Conversion, DRI, Delhi 1986) and translations (e.g. the Hindi version of Taslima Nasrin's Bengali book Lajja, published in instalments in Panchjanya, summer 1994), Goel has contributed the following books to the inter-religious debate:

· Hindu Society under Siege (1981, revised 1992);

· Story of Islamic Imperialism in India (1982);

· How I Became a Hindu (1982, enlarged 1993);

· Defence of Hindu Society (1983, revised 1987);

· The Emerging National Vision (1983);

· History of Heroic Hindu Resistance to Early Muslim Invaders (1984);

· Perversion of India's Political Parlance (1984);

· Saikyularizm, Râshtradroha kâ Dûsrâ Nâm (Hindi: "Secularism, another name for treason", 1985);

· Papacy, Its Doctrine and History (1986);

· Preface to The Calcutta Quran Petition by Chandmal Chopra (a collection of texts alleging a causal connection between communal violence and the contents of the Quran; 1986, enlarged 1987 and again 1999);

· Muslim Separatism, Causes and Consequences (1987);

· Foreword to Catholic Ashrams, Adapting and Adopting Hindu Dharma (a collection of polemical writings on Christian inculturation; 1988, enlarged 1994 with new subtitle: Sannyasins or Swindlers?);

· History of Hindu-Christian Encounters (1989, enlarged 1996);

· Hindu Temples, What Happened to Them (1990 vol.1; 1991 vol.2, enlarged 1993);

· Genesis and Growth of Nehruism (1993);

· Jesus Christ: An Artifice for Agrression (1994);

· Time for Stock-Taking (1997), a collection of articles critical of the RSS and BJP;

· Preface to the reprint of Mathilda Joslyn Gage: Woman, Church and State (1997, ca. 1880), an early feminist critique of Christianity;

· Preface to Vindicated by Time: The Niyogi Committee Report (1998), a reprint of the official report on the missionaries' methods of subversion and conversion (1955).

Goel's writings are practically boycotted in the media, both by reviewers and by journalists and scholars collecting background information on the communal problem. Though most Hindutva stalwarts have some Voice of India publications on their not-so-full bookshelves, the RSS Parivar refuses to offer its organizational omnipresence as a channel of publicity and distribution. Since most India-watchers have been brought up on the belief that Hindu activism can be identified with the RSS Parivar, they are bound to label Sita Ram Goel (the day they condescend to mentioning him at all, that is) as "an RSS man". It may, therefore, surprise them that the established Hindu organizations have so far shown little interest in his work.

It is not that they would spurn his services: in its Ayodhya campaign, the Vishva Hindu Parishad has routinely referred to a "list of 3000 temples converted into or replaced by mosques", meaning the list of nearly 2000 such cases in Goel, ed.: Hindu Temples, vol.1. Goel also published the VHP argumentation in the government-sponsored scholars' debate of 1990-91 (titled History vs. Casuistry), and he straightened and corrected the BJP's clumsily drafted White Paper on Ayodhya. But organizationally, the Parivar is not using its networks to spread Ram Swarup's and Sita Ram Goel's books and ideas. Twice (1962 and 1982) the RSS intervened with the editor of Organiser to have ongoing serials of articles (on Nehru c.q. on Islam) by Goel halted; the second time, the editor himself, the long-serving arch-moderate K.R. Malkani, was sacked along with Goel. And ideologically, it has always turned a deaf ear to their analysis of the problems facing Hindu society.

Most Hindu leaders expressly refuse to search Islamic doctrine for a reason for the observed fact of Muslim hostility. RSS leader Guru Golwalkar once said: "Islam is a great religion. Mohammed was a great prophet. But the Muslims are big fools." (Delhi ca. 1958) This is not logical, for the one thing that unites the (otherwise diverse) community of Muslims, is their common belief in Mohammed and the Quran: if any wrong is attributed to "the Muslims" as such, it must be situated in their common belief system. Therefore, Goel's position is just the opposite: not the Muslims are the problem, but Islam and Mohammed.

In the Ayodhya dispute, time and again the BJP leaders have appealed to the Muslims to relinquish all claims to the supposed birthplace of the Hindu god Rama, arguing that destroying temples is against the tenets of Islam, and that the Quran prohibits the use of a mosque built on disputed land. In fact, whatever Islam decrees against building mosques on disputed property, can only concern disputes within the Muslim community (or its temporary allies under a treaty). Goel has demonstrated in detail that it is perfectly in conformity with Islamic law, and established as legitimate by the Prophet through his own example, to destroy Pagan establishments and replace them with (or turn them into) mosques. For an excellent example, the Kaaba itself was turned into a mosque by Mohammed when he smashed the 360 Pagan idols that used to be worshipped in it.

Therefore, S.R. Goel is rather critical of the Ayodhya movement. In the foreword to Hindu Temples, vol.2, he writes: "The movement for the restoration of Hindu temples has got bogged down around the Rama Janmabhoomi at Ayodhya. The more important question, viz. why Hindu temples met the fate they did at the hands of Islamic invaders, has not been even whispered. Hindu leaders have endorsed the Muslim propagandists in proclaiming that Islam does not permit the construction of mosques at sites occupied earlier by other people's places of worship (...) The Islam of which Hindu leaders are talking exists neither in the Quran nor in the Sunnah of the Prophet. It is hoped that this volume will help in clearing the confusion. No movement which shuns or shies away from truth is likely to succeed. Strategies based on self-deception stand defeated at the very start."

Goel's alternative to the RSS variety of "Muslim appeasement" is to wage an ideological struggle against Islam and Christianity, on the lines of the rational criticism and secularist politics which have pushed back Christian self-righteousness in Europe. The Muslim community, of course, is not to be a scapegoat (as it is for those who refuse to criticize Islam and end up attacking Muslims instead), but has to be seen in the proper historical perspective: as a part of Hindu society estranged from its ancestral culture by Islamic indoctrination over generations. Their hearts and minds have to be won back by an effort of consciousness-raising, which includes education about the aims, methods and historical record of religions.

5. Conclusion

One of the grossest misconceptions about the Hindu movement, is that it is a creation of political parties like the BJP and the Shiv Sena. In reality, there is a substratum of Hindu activist tendencies in many corners of Hindu society, often in unorganized form and almost invariably lacking in intellectual articulation. To this widespread Hindu unrest about the uncertain future of Hindu culture, Voice of India provides an intellectual focus.

The importance of Ram Swarup's and Sita Ram Goel's work can hardly be over-estimated. I for one have no doubt that future textbooks on comparative religion as well as those on Indian political and intellectual history will devote crucial chapters to their analysis. They are the first to give a first-hand "Pagan" reply to the versions of history and "comparative religion" imposed by the monotheist world-conquerors, both at the level of historical fact and of fundamental doctrine, both in terms of the specific Hindu experience and of a more generalized theory of religion free from prophetic-monotheistic bias.

Their long-term intellectual importance is that they have contributed immensely to breaking the spell of all kinds of Christian, Muslim and Marxist prejudices and misrepresentations of Hinduism and the Hindu Revivalist movement.

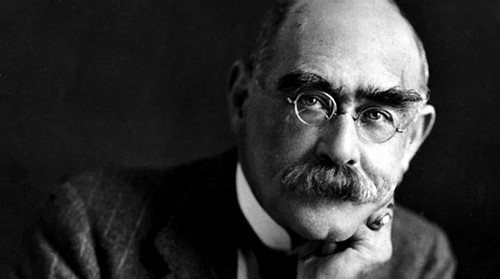

Joseph Rudyard Kipling est né le 30 décembre 1865, à Bombay, où ses parents sont arrivés huit mois plus tôt. Enfant, Kipling parle l’hindoustani aussi bien que l’anglais et, s’échappant du bungalow familial en compagnie de sa nounou (ayah), il découvre les foules indiennes aux turbans multicolores, les illusionnistes montreurs de serpents, les sons et les odeurs du bazar de Borah.

Joseph Rudyard Kipling est né le 30 décembre 1865, à Bombay, où ses parents sont arrivés huit mois plus tôt. Enfant, Kipling parle l’hindoustani aussi bien que l’anglais et, s’échappant du bungalow familial en compagnie de sa nounou (ayah), il découvre les foules indiennes aux turbans multicolores, les illusionnistes montreurs de serpents, les sons et les odeurs du bazar de Borah. Enfin il y a Kim, cette grande fresque publiée en 1901, roman picaresque, envoûtant, colonialiste et généreux, « l’oeuvre de la vie de Kipling ». Bien que le personnage principal en soit l’Inde, une Inde totale, éternelle, l’Inde de la grande route de liaison, l’un des personnages principaux est afghan. Celui-ci, Mahbub Ali, est marchand de chevaux ; il passe sa vie sur les pistes, entre Lahore et « la contrée mystérieuse au-delà des passes du Nord ». Agent des Britanniques, il surveille depuis Peshawar les principautés des montagnes. Selon Zorgbibe, Mahbub Ali incarne aux yeux de Kipling « à la fois l’Afghanistan hostile, incontrôlable et redouté, et l’espoir d’une alliance avec une fraction des Afghans » – ce qui est probablement le lien le plus pertinent qui puisse être établi avec les enjeux du conflit actuel.

Enfin il y a Kim, cette grande fresque publiée en 1901, roman picaresque, envoûtant, colonialiste et généreux, « l’oeuvre de la vie de Kipling ». Bien que le personnage principal en soit l’Inde, une Inde totale, éternelle, l’Inde de la grande route de liaison, l’un des personnages principaux est afghan. Celui-ci, Mahbub Ali, est marchand de chevaux ; il passe sa vie sur les pistes, entre Lahore et « la contrée mystérieuse au-delà des passes du Nord ». Agent des Britanniques, il surveille depuis Peshawar les principautés des montagnes. Selon Zorgbibe, Mahbub Ali incarne aux yeux de Kipling « à la fois l’Afghanistan hostile, incontrôlable et redouté, et l’espoir d’une alliance avec une fraction des Afghans » – ce qui est probablement le lien le plus pertinent qui puisse être établi avec les enjeux du conflit actuel.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

De vedische hymnen werden volgens de vedische overlevering zelf hoofdzakelijk gecomponeerd in de schoot van de Paurava-stam, de stam van Puru, één van de vijf zonen van Yayāti, een prins van de Maandynastie uit Prayāg (later bekend als Allāhābād) en veroveraar van het bovenstroomgebied van de Sarasvatī in het noordwesten van India. Deze was via een gemeenschappelijke voorvader, Manu Vaivasvata die de zondvloed overleefde, verwant met de Zonnedynastie uit Ayodhyā, waartoe Rāma (en later ondermeer ook de Boeddha) behoorde. Eén van de eerste Paurava-koningen heette Bharata. Het is naar hem dat India zichzelf nog steeds Bhāratavarsa of kortweg Bhārat noemt.

De vedische hymnen werden volgens de vedische overlevering zelf hoofdzakelijk gecomponeerd in de schoot van de Paurava-stam, de stam van Puru, één van de vijf zonen van Yayāti, een prins van de Maandynastie uit Prayāg (later bekend als Allāhābād) en veroveraar van het bovenstroomgebied van de Sarasvatī in het noordwesten van India. Deze was via een gemeenschappelijke voorvader, Manu Vaivasvata die de zondvloed overleefde, verwant met de Zonnedynastie uit Ayodhyā, waartoe Rāma (en later ondermeer ook de Boeddha) behoorde. Eén van de eerste Paurava-koningen heette Bharata. Het is naar hem dat India zichzelf nog steeds Bhāratavarsa of kortweg Bhārat noemt. Tenslotte zijn uit al deze intellectuele bedrijvigheid nog de volgende vier disciplines voortgekomen: Mīmānsā, “duiding, exegese”; Nyāya, “oordeel, logica”; Purāna, “oudheid, geschiedenis”, weliswaar overlopend in mythologie; en Dharma-Śāstra, “ethiek”, maatschappelijke plichtenleer, sociologie. De eerste twee zijn het begin van de “zes standpunten” of wijsgerige scholen, met als overige vier Sānkhya, “opsomming”, elementenleer, dualistische kosmologie; Vaiśesika, “onderscheiding van bijzonderheden”, pluralistische kosmologie; Yoga, “beheersing”, leer van de controle over het gedachtenleven; en Uttara-Mīmānsā, “latere duiding” alias Vedānta, “het sluitstuk van de Veda”, d.w.z. de monistische uitwerking van de oepanisjadische leer van het Zelf.

Tenslotte zijn uit al deze intellectuele bedrijvigheid nog de volgende vier disciplines voortgekomen: Mīmānsā, “duiding, exegese”; Nyāya, “oordeel, logica”; Purāna, “oudheid, geschiedenis”, weliswaar overlopend in mythologie; en Dharma-Śāstra, “ethiek”, maatschappelijke plichtenleer, sociologie. De eerste twee zijn het begin van de “zes standpunten” of wijsgerige scholen, met als overige vier Sānkhya, “opsomming”, elementenleer, dualistische kosmologie; Vaiśesika, “onderscheiding van bijzonderheden”, pluralistische kosmologie; Yoga, “beheersing”, leer van de controle over het gedachtenleven; en Uttara-Mīmānsā, “latere duiding” alias Vedānta, “het sluitstuk van de Veda”, d.w.z. de monistische uitwerking van de oepanisjadische leer van het Zelf.

U

U

Could Syed Shahabuddin be a communalist? After all, he played a key role in the three main "Muslim communalist" issues of recent years: the Babri Masjid campaign, the Shah Bano case and the Salman Rushdie affair (it is he who got The Satanic Verses banned in September 1988). Surely, he must be India's communalist par excellence? Wrong: if you read any page of any issue of Shahabuddin's monthly Muslim India, you will find that he brandishes the notion of "secularism" as the alpha and omega of his politics, and that he directs all his attacks against Hindu "communalism". The same propensity is evident in the whole Muslim "communalist" press, e.g. the Jamaat-i Islami weekly Radiance. Moreover, on Muslim India's editorial board, you find articulate secularists like Inder Kumar Gujral, Khushwant Singh and the late P.N. Haksar.

Could Syed Shahabuddin be a communalist? After all, he played a key role in the three main "Muslim communalist" issues of recent years: the Babri Masjid campaign, the Shah Bano case and the Salman Rushdie affair (it is he who got The Satanic Verses banned in September 1988). Surely, he must be India's communalist par excellence? Wrong: if you read any page of any issue of Shahabuddin's monthly Muslim India, you will find that he brandishes the notion of "secularism" as the alpha and omega of his politics, and that he directs all his attacks against Hindu "communalism". The same propensity is evident in the whole Muslim "communalist" press, e.g. the Jamaat-i Islami weekly Radiance. Moreover, on Muslim India's editorial board, you find articulate secularists like Inder Kumar Gujral, Khushwant Singh and the late P.N. Haksar. In the 1930s and 40s, the Gandhians themselves came in the shadow of the new ideological vogue: socialism. When they started drifting to the Left and adopting socialist rhetoric, S.R. Goel decided to opt for the original rather than the imitation. In 1941 he accepted Marxism as his framework for political analysis. At first, he did not join the Communist Party of India, and had differences with it over such issues as the creation of the religion-based state of Pakistan, which was actively supported by the CPI but could hardly earn the enthusiasm of a progressive and atheist intellectual. He and his wife and first son narrowly escaped with their lives in the Great Calcutta Killing of 16 August 1946, organized by the Muslim League to give more force to the Pakistan demand.

In the 1930s and 40s, the Gandhians themselves came in the shadow of the new ideological vogue: socialism. When they started drifting to the Left and adopting socialist rhetoric, S.R. Goel decided to opt for the original rather than the imitation. In 1941 he accepted Marxism as his framework for political analysis. At first, he did not join the Communist Party of India, and had differences with it over such issues as the creation of the religion-based state of Pakistan, which was actively supported by the CPI but could hardly earn the enthusiasm of a progressive and atheist intellectual. He and his wife and first son narrowly escaped with their lives in the Great Calcutta Killing of 16 August 1946, organized by the Muslim League to give more force to the Pakistan demand.  In the 1950s, Goel was not active on the "communal" battlefield: not Islam or Christianity but Communism was his priority target. Yet, under Ram Swarup's influence, his struggle against communism became increasingly rooted in Hindu spirituality, the way Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's anti-Communism became rooted in Orthodox Christianity. He also co-operated with (but was never a member of) the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, and he occasionally contributed articles on Communism to the RSS weekly Organiser. In 1957 he contested the Lok Sabha election for the Khajuraho constituency as an independent candidate on a BJS ticket, but lost. He was one of the thirty independents fielded as candidates by Minoo Masani in preparation of the creation of his own (secular, rightist-liberal) Swatantra Party.

In the 1950s, Goel was not active on the "communal" battlefield: not Islam or Christianity but Communism was his priority target. Yet, under Ram Swarup's influence, his struggle against communism became increasingly rooted in Hindu spirituality, the way Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's anti-Communism became rooted in Orthodox Christianity. He also co-operated with (but was never a member of) the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, and he occasionally contributed articles on Communism to the RSS weekly Organiser. In 1957 he contested the Lok Sabha election for the Khajuraho constituency as an independent candidate on a BJS ticket, but lost. He was one of the thirty independents fielded as candidates by Minoo Masani in preparation of the creation of his own (secular, rightist-liberal) Swatantra Party. In 1981 Sita Ram Goel retired from his business, which he handed over to his son and nephew. He started the non-profit publishing house Voice of India with donations from sympathetic businessmen, and accepted Organiser editor K.R. Malkani's offer to contribute some articles again, articles which were later collected into the first Voice of India booklets.

In 1981 Sita Ram Goel retired from his business, which he handed over to his son and nephew. He started the non-profit publishing house Voice of India with donations from sympathetic businessmen, and accepted Organiser editor K.R. Malkani's offer to contribute some articles again, articles which were later collected into the first Voice of India booklets.