From Romanticism to Traditionalism

Thomas F. Bertonneau

Ex: http://peopleofshambhala.com

The movement called Romanticism belongs chronologically to the last two decades of the Eighteenth and the first five decades of the Nineteenth Centuries although it has antecedents going back to the late-medieval period and sequels that bring it, or its influence, right down to the present day. Historically, and in simple, Romanticism is the view-of-things that succeeds and corrects its precursor among the serial views-of-things that have shaped the general outlook of the Western European mentality – what historians of ideas call Classicism, and which they identify as the worldview of the Enlightenment. A good definition of Classicism is: The devotion to prescriptive orderliness for its own sake in all departments of life; the submission of all things to measure, decorum, and, using the word metaphorically, the geometric ideal. Classicism implies the conviction that reason, narrowly delimited, is the highest faculty, and indeed almost the sole faculty worth developing. The Classicist believes that life can be perfected by rationalization. Certainly this is how the Romantics saw Classicism, but it is also in broad terms how the Classicists saw themselves. According to its own dichotomy, Romanticism would be a view of existence consisting of tenets diametrically opposed to those of Classicism.

Detail of “The Course of Empire: Desolation,” 1836, oil on canvas, by Thomas Cole (1801-1848), founder of the Hudson River School.

And so largely it was or is, as Romanticism is by no means a dead issue. As the Romantic sees it, imposed or conventional order tends to distort or obliterate the natural order; and by “natural order” the Romantics would have understood not only the order of nature, considered as Creation, but the order present in social adaptation to the natural order, as when agriculturalists follow the cycle of the seasons and attune their lives with the life of the soil or when builders of monuments and temples go to great effort to align them astronomically. In addition, the Romantic believes that a bit of disorder might stimulate and enliven life, preventing it from becoming stiff and ossified; that the quirky and unexpected can exert a benevolent influence. The Romantic also values emotion and intuition as much as he values reason, which he by no means disdains although he defines it more broadly than the Classicist. The Romantics explicitly rejected the utilitarian arguments of the Classicists. Romanticism prefigures and is the likely source of what in the second half of the Twentieth Century came to be known as Traditionalism.

I. Characteristics of Romanticism. Where the geometrically patterned gardens of the French kings, like those designed by Claude Millet in 1632 for Louis XIV at Versailles, might stand for the Classical Spirit, the “English Garden,” with its meandering paths, sprawling bushes, and indifference to the weeds might stand for the Romantic Spirit. Where Classicism took as its model Greece or Rome, Romanticism looked to the Middle-Ages. Where Classicism venerated the purest, most elevated Attic style of speech, Romanticism cultivated the Gothic, the Celtic, and the regional dialect; it was not averse to rude or rustic idiom. Classical playwrights like Pierre Corneille (1606 – 1684) and Jean Racine (1639 – 1699) imitated Euripides and Seneca; Romantic playwrights like Friedrich Schiller (1788 – 1805) and Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885) imitated Shakespeare, whom Voltaire had dismissed as a barbarian and his work as a formless affront to the unities. Classicism concerns itself with form, which prescribes content, Romanticism with content, which then suggests the form.

What have the scholars written about Romanticism? None exceeds the scholarly stature of Jacques Barzun (1907 – 2012), whose study From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life (2000) devotes three chapters to Romanticism. Remarking that Romanticism had, in the broadest sense, something of the quality of a religious or spiritual awakening, and that, unlike Classicism, it extended its horizon of curiosity very far indeed – as for example into myth and folklore considered as other than mere superstition – Barzun writes:

With their searching imagination in literature and art, it could be expected that the Romanticists’ intellectual tastes would be anything but exclusive. They found the Middle Ages a civilization worthy of respect; they relished folk art, music, and literature; they studied Oriental philosophy; they welcomed the diversity of national customs and character, even those outside the [Eighteenth Century] cosmopolitan circuit; they surveyed dialects and languages with enthusiasm. This was a genuine multiculturalism, the wholehearted acceptance of the remote, the exotic, the folkish, [and] the forgotten.

Barzun adds that, “in Romanticism, thought and feeling are fused; [Romanticism’s] bent is toward exploration and discovery at whatever risk of error or failure; the religious emotion is innate and demands expression… the divine may be reached through nature or art.” Under Barzun’s description, Romanticism would be humanly more whole than Classicism, with the latter excluding rather than incorporating the emotional impulse while granting to intuition a key role in the exploration of existence.

The Norwegian scholar, F. J. Billeskov Jansen (1907 – 2002), writing in the compendium Romantikken: 1800 – 1830 (Verdens Litteratur Historie, V. III, 1972), asserts that:

Opplysningstidens mennesker hade fryktet lidenskapene, som kunne true den sunne fornuft. Alt hos Klopstock ble likevel den religiøse lidenskap frigjort, og hos Rousseau elskovspasjonen og natursvermeriet. I romantikkens tidsalder blir diktere drømmere, Sjelen utvides I lengsel mot uendligheten, gjennom innføling forener poeten med nature, hans fantasi fører ham langt bort på eventyrets vinger eller langt tilbake i historien; hans håp får form av religiøse visjoner.

[The men of the Enlightenment had feared the passions, which could threaten right reason. Simultaneously in [the work of Friedrich Gottlieb] Klopstock religious enthusiasm gained liberation, (just) as in the work of (Jean-Jacques) Rousseau did amorous passion and ecstasy in nature. In the age of romanticism, poets became dreamers. The soul expands in longing for infinity, the poet attaining oneness with nature through his inward feeling, while his imagination leads him far afield on the wings of adventure or far back into history; his hope takes the form religious visions.]

Elsewhere in the same volume, another scholar characterizes Romanticism as a return of Platonic theology. Certainly Plato’s myths of the “Ladder of Philosophy,” “The Winged Horses and their Charioteer,” and “The Cave” find their later reflection in the imagery of the Romantic poets. For Plato, importantly, the phenomena of this world point to a purely spiritual world – the realm of God and the Ideas. We find a similar attitude in the poetry William Blake (1757 – 1827) and in that of William Wordsworth (1770 – 1850). The main point to be stressed, however, is Jansen’s description of Romanticism as the labor of the soul to break free from the trammels of degraded matter and to rejoin a vital spirit that suffuses the universe and renders it intelligible. The Romantics concluded that the assumptions of rationalism were parochial and constricting; that they did not give a true account of humanity or the universe.

In his study of Poetic Diction (1928), philologist and literary critic Owen Barfield (1898 – 1997) attempts to identify and prescind the fundamental Romantic ideas, one of which has to do with the role of “the rational principle”:

Now although, without the rational principle, neither truth nor knowledge could have been, but only life itself, yet that principle cannot add one iota to knowledge. It can clear up obscurities, it can measure and enumerate with greater and ever greater precision, [and] it can preserve us in the dignity and responsibility of our individual existences. But in no sense can it be said… to expand consciousness. Only the poetic can do this: only poesy, pouring into language its creative intuitions, can preserve its living meaning and prevent it from crystallizing into a kind of algebra. “If it were not for the Poetic or Prophetic character,” wrote William Blake, “the philosophic and experimental would soon be at the ratio of things, and stand still, unable to do other than repeat the same dull round.”

For Barfield, Romanticism qualifies not only as a revolt against the strictures of the Enlightenment; it is not only the accession of a new type of taste or sensibility that supersedes an earlier one: It is a change – and, for Barfield, a positive development – in human consciousness. Understood in the way that Barfield, Jansen, and Barzun see it, Romanticism resembles – or, rather it anticipates –Traditionalism. In The Crisis of the Modern World (1927), for example, René Guénon (1886 – 1951) describes the modern person as averse to referring “beyond the terrestrial horizon” and as crediting “no knowledge beyond what proceeds from the sense.” For Guénon, the modern world “is anti-Christian because it is essentially anti-religious; and it is anti-religious because, in a still wider sense, it is anti-traditional.” Writing in Harry Oldmeadow’s anthology The Betrayal of Tradition (2005) and invoking the spirit of T. S. Eliot, Brian Keeble asserts that fullness of humanity requires contact with “the transcendent dimension”; and, calling on Blake, he invokes the “sacred reality of the spirit.”

II. The Romantic Subject. Romanticism saw a great flowering of lyric poetry, and this was no coincidence. Lyric poetry is personal, even egocentric, poetry; or it is poetry personal in character even in the case where the putative “I” who speaks in the poem is purely fictional and is not to be identified with the author. The name lyric suggests the solo singer accompanying himself on the lyre, bursting out in song, as the spirit takes him. Lyric poetry is expressive: It represents in externalized imagery the internal state, intellectual or emotional, of the poet. Of course, inner states usually correlate themselves with external circumstances and conditions. Anyone who comments on the soul also necessarily comments on the world. The Romantics seized on the lyric as their primary mode of poetizing because the conventions of lyric so perfectly suited that part of the Romantic program that concerned the exploration of the subject’s inner life. Of course, the Romantic poet interests himself in much more than in pouring out the contents of his overflowing heart. That would be a sophomoric misapprehension. On the contrary, for the talented poet, well-schooled, mentally acute, moved by inveterate curiosity about the world, even a brief lyric poem can be the vehicle of a subtle critique or argument. If the Romantic poet were a prophet then he would also be a philosopher.

What does it mean to be a subject, an ego, an “I”? Subjectivity is self-consciousness, an abiding awareness that one is this person, with this biography (always thus far), and with these relations to and with and in the world – and not some other person with other relations. But every subject, every self-conscious person, is aware that the world is full of other self-conscious persons whose subjectivity, as he infers, is generically like his own right down to the detail that each has (or ought to have) a similar sense of his own particularity and difference from the others. Beyond persons, places, and things, the subject senses – although he can never empirically grasp – a totality of things, a cosmos, and an authorial or organizing principle, for which the common name is God. Wisdom consists in knowing that there was a world indefinitely before his own subjectivity began and there will be a world indefinitely after his own subjectivity ceases; he is a part of something larger than himself, which lies beyond the limits of his will.

Mood conditions subjectivity. The typical self-consciousness addressed in the previous paragraph should be qualified as the healthy self-consciousness. Because, however, no one can keep the world absolutely at bay, he must suffer the impingements of the world, whether happily or sadly. Forces beyond a subject’s control can alienate him from himself and through ignorance or perversity he can exacerbate his alienation. The Romantics believed that the worldview of Classicism, or the Enlightenment, described life and the world falsely, and that those who embraced its falsehoods must in some way become alienated. The Romantics regarded with acute skepticism the modern claims concerning material progress. “The world is too much with us, late and soon, / Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers,” wrote Wordsworth. In the labyrinth of the new metropolis, the soul might once again lose its way and suffer, as men once did in the Cities of the Plain, and experience pure indifference with respect to its own sickness. What kind of civic environment would arise from the presence together in large urban agglomerations of millions of such afflicted people? The psychic problem must inevitably become a social and a cultural problem.

It is worth quoting Wordsworth’s sonnet in full:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

The Romantics understood that consciousness rises to acuity in events and crises, like that experienced by Wordsworth’s monologist in the stale abjection of his despair. The growth of consciousness proceeds punctually rather than gradually, and it entails the tribulations of a solemn pilgrimage. Lyric poetry, being the poetry of the subject’s self-consciousness, therefore also tends to be the poetry of sudden events – discrete moments in which the subject suddenly discovers something about himself, the world, or himself in relation to the world, that hitherto he did not know and knowledge of which alters him. It might be, as in the case of “The world is too much with us,” the discovery of one’s own spiritual poverty; it might be an access of grace. Such moments sometimes bear the name of epiphany; they are in any case always revelatory – and they cannot be solicited. They impose themselves, as if by external guidance, as gifts, upon the percipient.

The epiphanic or revelatory quality of lyric poetry has to do with its effort to appear spontaneous. Every work of art requires arduous labor, even a fourteen-line sonnet, but Wordsworth, for example, insisted that he drew inspiration from abrupt visionary experiences and that articulating the vision although onerous entailed given textual form to a unitary idea. Discussing the origin of his major poems – The Prelude, The Excursion, and the unfinished Recluse – in letters to his friends, Wordsworth situated himself as the channel for impulses that had befallen him, as revelation befalls the prophet, whether he seeks his election or not.

The Romantic subject resembles – or, rather, it anticipates – the Traditionalist subject, as Guénon, Nicolas Berdyaev (1874 – 1948), and others have defined it. Guénon himself in The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times (1945) characterizes modern man as having “lost the use of the faculties which in normal times allowed him to pass beyond the bounds of the sensible world.” This loss leaves modern man alienated from “the cosmic manifestation of which he a part”; in Guénon’s analysis modern man assumes “the passive role of a mere spectator” and consumer, which is exactly how Wordsworth saw it. Of course, Guénon does not write of loss as an accident, but as the logical consequence of choices and schemes traceable to the Enlightenment. As Wordsworth put it, “We have given our hearts away – a sordid boon.”

According to Berdyaev, writing in The Destiny of Man (1931), “Man is not a fragmentary part of the world but contains the whole riddle of the universe and the solution of it.” Berdyaev asserts that, contrary to modernity, “man is neither the epistemological subject [of Kant], nor the ‘soul’ of psychology, nor a spirit, nor an ideal value of ethics, logics, or aesthetics”; but, abolishing and overstepping all those reductions, “all spheres of being intersect in man.” Berdyaev argues that, “Man is a being created by God, fallen away from God and receiving grace from God.” The prevailing modern view, that of naturalism, “regards man as a product of evolution in the animal world,” but “man’s dynamism springs from freedom and not from necessity”; it follows therefore that “evolution” cannot explain the mystery and centrality of man’s freedom. When Berdyaev brings “grace” into his discussion, he echoes the original Romantics, whose version of grace was the epiphanic vision, the event answering to a crisis that brings about the conversion of the fallen subject and sets him on the road to true personhood.

III. Romantic Nature. The Romantic redefinition of nature, which the Romantics invariably capitalize as Nature, runs in parallel with the Romantic redefinition of selfhood. Where the Enlightenment had reduced nature to material processes – geological, chemical, physiological, mechanical, and optical – with no reference to anything outside themselves, Romanticism in reaction posited Nature not only as vital throughout but also as meaningful, and natural phenomena as pointing beyond themselves to things supernatural. This redefinition of nature was perhaps less a total innovation than it was the re-appropriation of an old idea going back to late-medieval thinkers like Jakob Boehme (1575 – 1624), Paracelsus (1493 – 1541), and even Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630), who saw in nature a decipherable living message that implies a message-maker whose motivation must be that he wishes to establish contact with human beings. Behind those figures lies Christian Platonism. Under this late-medieval idea, the sensitive soul can not only come into communication through nature with what lies beyond nature; but he can also, through nature, come into communion with what is beyond nature. In Christian, rather than pagan, terms, the Romantic rediscovers Nature as “The Book of Nature,” a kind of supplement to the two Testaments, whose author is God, as normally or eccentrically conceived by the individual writer-thinker.

A longstanding and not altogether inaccurate thumbnail categorization of Romantic poetry is that it is nature poetry. The Romantic penchant for verbal picturesque redoubles the plausibility of the claim. Here, for example, is Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834) conjuring forth the abyss that lies beneath “The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan” in the fragmentary poem (1798) of that name.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean;

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

In Coleridge’s poem, which he subtitles “a vision in a dream,” Nature is all depth, but better to say that for Coleridge in “Kubla Khan” Nature is vital depth; Nature is a wellspring of robust and creative urgencies that is almost everywhere and almost at every moment alive. The exception would be the “lifeless ocean,” a symbol perhaps of what we now call entropy, but in a world of perpetual emergence even a “lifeless ocean” might be redeemed and revivified. Indeed, Coleridge in the quoted verses seems to be rescuing the etymon of the word nature, which is the same etymon that gave rise to the French verb naître, “to be born” or “to give birth.” The “chasm” gives birth to “a mighty fountain,” which in turn transforms itself into “a sacred river.” Coleridge’s endowment on the scenario of the term “sacred” reminds us that his Nature is not only vital, but hallowed or divine. The creative processes in nature point to a divine creative power beyond nature that reveals itself in phenomena and solicits from the sensitive soul the idea of something that requires a formal acknowledgment of its generative awesomeness.

Coleridge’s “caverns measureless to man” stand for the unplumbed depths not only of Nature but of the soul. To explore the hidden depths of Nature means also to explore the soul and vice versa. Coleridge draws on ancient conceptions that the Enlightenment claimed to have debunked, such as the conception of the psyche or soul, as articulated by the archaic philosopher-seer Heraclitus of Ephesus in one of his surviving aphorisms (No. 45): “You will not find out the limits of the soul when you go, travelling on every road, so deep a logos does it have.” Where the Enlightenment assumed that everything might be measured – that is to say, brought within the horizon of finite knowledge – Coleridge insists that the world possesses a “measureless” dimension that resists logical summary or reduction to purely quantitative or propositional terms. The only way to discuss such things is in symbol, imagery, and figure-of-speech.

Thomas Cole (1801-1848) The Catskills and Lake George, Catskill Creek, N.Y., 1845, oil on canvas.

A similar view of Nature as the source of vital energy necessary to the soul informs the final scene of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust Part II (1831), where the errant sinner, Doctor Johann Faust, at last finds redemption from his graceless and degraded state. Goethe (1749 – 1832) sets his scene in primeval nature:

Waldung, sie schwankt heran,

Felsen, sie lasten dran,

Wurzeln, sie klammern an,

Stamm dicht an Stamm hinan,

Woge nach Woge spritzt,

Höhle, die tiefste, schützt.

Löwen, sie schleichen stumm-–

freundlich/ um uns herum,

Ehren geweihten Ort,

Heiligen Liebeshort.

[Forests, they wave around,

Over them, cliffs bear down,

Roots cling to rocky ground,

Trunk upon trunk is bound,

Wave after wave sprays up,

Deep caves protecting us.

Lions prowl silently,

Round us, still friendly,

Honouring sacred space,

Love’s holy hiding place.]

A few verses later, the character called Pater Profundis, who will play a mediating role in Faust’s redemption, utters these lines:

Wie Felsenabgrund mir zu Füßen

Auf tiefem Abgrund lastend ruht,

Wie tausend Bäche strahlend fließen

Zum grausen Sturz des Schaums der Flut,

Wie strack mit eignem kräftigen Triebe

Der Stamm sich in die Lüfte trägt:

So ist es die allmächtige Liebe,

Die alles bildet, alles hegt.

Ist um mich her ein wildes Brausen,

Als wogte Wald und Felsengrund,

Und doch stürzt, liebevoll im Sausen,

Die Wasserfülle sich zum Schlund,

Berufen, gleich das Tal zu wässern;

Der Blitz, der flammend niederschlug,

Die Atmosphäre zu verbessern,

Die Gift und Dunst im Busen trug –

Sind Liebesboten, sie verkünden,

Was ewig schaffend uns umwallt.

Mein Innres mög‘ es auch entzünden,

Wo sich der Geist, verworren, kalt,

Verquält in stumpfer Sinne Schranken,

Scharfangeschloßnem Kettenschmerz.

O Gott! beschwichtige die Gedanken,

Erleuchte mein bedürftig Herz!

[As this rocky abyss at my feet,

Rests on a deeper abyss,

As a thousand glittering streams meet

In the foaming flood’s downward hiss,

As with its own strong impulse, above,

The tree lifts skywards in the air:

Even so all-powerful love,

Creates all things, in its care.

Around me there’s a savage roar,

As if the rocks and forests sway,

Yet full of love the waters pour,

Rushing bountifully away,

Sent to irrigate the valley here:

The lightning that flashed down,

Must purify the atmosphere,

With poisonous vapours bound –

They are love’s messengers, they tell

Of what creates eternally around us.

May it inflame me inwardly, as well,

Since my spirit, cold and confounded,

Torments itself, bound in the dull senses,

As sharp-toothed fetters’ agonising art.

Oh, God! Calm my thoughts, pacify us,

And bring light to my needy heart!]

For Goethe as for Coleridge, Nature is the bourn of life, to which the afflicted soul might return to be nursed back to health. We recall that in Wordsworth’s sonnet “The world is too much with us,” the lyric subject feels exiled from nature and, in his attempt to rejoin with nature, catastrophically rebuffed. The world seems to him lifeless and still, and he also with it; he wants revivification. Faust seeks the same. Goethe’s “forests” answer him not in stillness, but make constantly a motion as they “wave around.” Just so, the “cliffs” actively “bear down” and “roots cling.” The dimension of depth goes not missing, for in Goethe’s scene “deep caves protect us” in a landscape thickly tangled (“trunk upon trunk”) that is “sacred” and, like some lonely place where a ritual purification might occur, hidden (“Love’s holy hiding place”) from profane eyes. When Pater Profundis (“The Father of the Depth”) begins to speak, he credits the landscape with “its own strong impulse.” The tree, straining its branches skyward, responds to the attractive principle of “Love” that serves Goethe for the equivalent of the non-anthropomorphic energy suffusing the caverns beneath Coleridge’s “stately pleasure dome” in “Kubla Khan.”

A poignant recurrence of this Coleridgean-Goethean constellation of ideas about Nature may be found in the work of the late John Michell (1933 – 2009), who referred to himself as a “Radical Traditionalist.” Readers know Michell best for his persistent work on the megalithic monuments of the European Neolithic Period, especially in Britain, which he demonstrated to have constituted a continental, and perhaps even a global, network whose builders intended them to help in keeping the dominion of man in contact with the dominion of the stars and of the deities that the stars betokened. Like Coleridge and Goethe, Michell posited a vital energy inherent in the earth, which the old stone circles and the long straight lines connecting them channeled and tapped. Michell possessed that conviction of a deep past antecedent to himself that distinguishes both Romanticism and Traditionalism from the modern default-state of “historylessness” and dogmatic materialism.

In The View over Atlantis (1969; revised as The New View over Atlantis, 1985), Michell writes how “of the various human and superhuman races that have occupied the earth in the past we have only the dreamlike accounts of the earliest myths, which tell of the magical powers of the ancients.” In his bold assertion, Michell echoes the prophecies of Blake, who revived the Old Plato’s “true myth” from the Timaeus in his epic poem America (1793). As in the Genesis-story of the Deluge or in Plato’s “Atlantis” story, Michell pieces together a narrative about “an overwhelming disaster of human or natural origin which destroyed a system whose maintenance depended upon its control of natural forces across the entire earth.” In one sense, Michell has simply reiterated that the Enlightenment happened, cutting across the lines of Tradition and depriving humanity of its proper heritage. For Michell, as for Blake or Wordsworth or Goethe, history is not the “account… of a recent ascent from bestiality and barbarism to the triumphs of modern civilization, but of a gradual, barely interrupted decline from the universal high culture of [Neolithic] antiquity to the present state of fragmentation and impending dissolution.”

IV. Romantic Nature Continued. Often for the Romantic poet, nature gives cover to secret activities that betoken an older world that in modern civic domains has given way to the despiritualizing forces of measure and logic – in the sociological process that some historians refer to as de-mystification. Nature is mysterious; she is the “magic forest” of the fairy-tales and legends, to enter which is perforce to run the risk of impish enthrallment or initiatory imperilment. In the pathways of the forest, man, in his ancient role as hunter, pursues wild game and, taking the prey, becomes one with it. The opening stanzas of “le Cor” (1826) by the French poet Alfred de Vigny (1797 – 1863) instantiate this variant of the Romantic Nature:

J’aime le son du Cor, le soir, au fond des bois,

Soit qu’il chante les pleurs de la biche aux abois,

Ou l’adieu du chasseur que l’écho faible accueille,

Et que le vent du nord porte de feuille en feuille.

Que de fois, seul, dans l’ombre à minuit demeuré,

J’ai souri de l’entendre, et plus souvent pleuré!

Car je croyais ouïr de ces bruits prophétiques

Qui précédaient la mort des Paladins antiques.

[I love the sounding horn, of an eve, deep within the woods,

Whether it sings the plaints of the threatened doe

Or the hunter’s retreat but faintly echoed

That the north wind carries from leaf to leaf.

[How often alone, in midnight shadows concealed,

I have smiled to hear it, even shedding a tear!

I thought to hear sounding prophetic plaints,

Declaring the death-knell for knights of old.]

As in Coleridge and Goethe, Nature in Vigny’s poetry offers herself as depth; she furnishes the paradoxically unapprehended scene of a ritual performance, which, however, the lyric subject can reconstitute in his imagination, provoked to the activity by the very sound. The horn-call reaches the lyric subject of Vigny’s poem from far away in the concealment of the woods, a place of half-light and shadows. The horn-call incites the lyric subject, as he says, to love: “I love the sounding of the horn, of an eve, deep within the woods.” But what is this “love”? It is precisely the awakened desire for the transcendent and unseen, for depth and distance; and it is a response to the sacred, mirrored in the desire of man for woman, and of the soul for beauty.

Note how in the first stanza of Vigny’s poem the sound of the horn mingles with the rustling of the north wind, as though the two timbres had become one and therefore indistinguishable. In the second stanza, the horn-call comes to resemble “prophetic plaints, / declaring the death-knell for knights of old.” Not only the reunion of culture and nature, which have become alienated from one another, but also whole extinct worlds of medieval pageantry and hieratic drama, lie concealed in oaken and beechy precincts. Let it be noted finally, in passing, how Vigny’s “Cor” with its “prophetic plaints” makes a parallelism with Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” where “ancestral voices” are “prophesying war.”

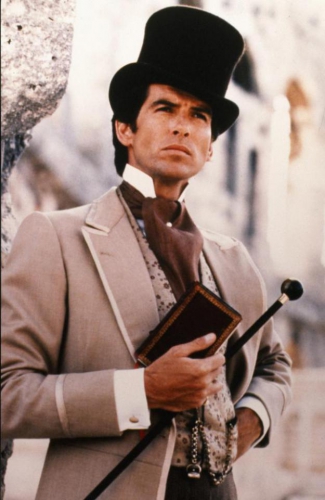

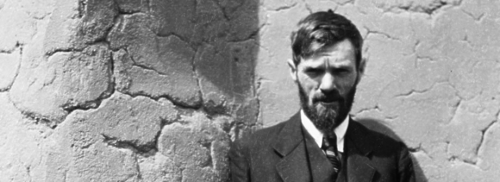

“Goethe in the Roman Campagna,” 1786, by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, oil on canvas.

What do the scholars say about the Romantic view of landscape and nature? François-René Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848), a second-generation French Romantic who was also one of the early scholars of Romanticism, writes in his great study of The Genius of Christianity (1802) concerning the distinction between ancient and modern poetry that “mythology… circumscribed the limits of nature and banished truth from her domain.” In modern poetry, by which Chateaubriand means Christian poetry: “The deserts have assumed a character more pensive, more vague, and more sublime; the forests have attained a loftier pitch; the rivers have broken their pretty urns, that in future they may only pour the waters of the abyss from the summit of the mountains; and the true God, in returning to his works, has imparted his immensity to nature.” Chateaubriand associates paganism with naturalism – that is to say, with the taxonomic or classifying study of natural phenomena, as exemplified in the work of Pliny the Younger. Chateaubriand thus opposes the Romantic or Christian view of Nature against the Classical or Pagan view of nature, which had been taken up again by the Enlightenment, favoring the former over the latter.

If, as Chateaubriand writes, “the prospect of the universe [excited not] in the bosoms of the Greeks and Romans those emotions which it produces in our souls,” then it follows that the Enlightenment mentality, surveying the same “prospect,” would come away from the encounter as affectively blank as did the Epicurean precursor whose view Eighteenth-Century Classicism has reinvented. The modern poet in confronting the universe, according to Chateaubriand, enjoys the differentiating privilege to “taste the fullness of joy in the presence of its Author.” It is true that there is no Pagan equivalent of the Fall-from-Grace. Because consciousness is equivalent to recollection, and because paganism never experienced Nature as lost, the Christian sense of Nature must exceed the Pagan sense in both quality and intensity. Christianity is a return to nature or a recovery of it, a homecoming, as it were, with all the poignancy thereof.

In Natural Supernaturalism (1973), one of the great studies of the Romantic Movement, and with specific reference to Wordsworth, M. H. Abrams (born 1912 – still living) writes that for the Grasmere poet “Scriptural Apocalypse is assimilated to an apocalypse of nature [whose] written characters are natural objects, which [the poet reads] as types and symbols of permanence in change.” Abrams shows in his study how Wordsworth in particular and the Romantics in general inherited from Edmund Burke and German idealism the aesthetic dichotomy of The Beautiful and the Sublime. The Beautiful is whatever is picturesque, pleasing, and amiable in Nature. The Sublime is whatever is awesome, threatening, and grandiose in Nature. In communing with Nature, the sensitive soul finds in Beauty the stepping-stone to the Sublime, and it is in the Sublime that he reads – or has read to him – the real lesson of Nature. Abrams writes that the “antithetic qualities of sublimity and beauty are seen [by the poet] as simultaneous expressions on the face of heaven and earth, declaring an unrealized truth which the chiaroscuro of the scene articulates for the [properly] prepared mind – a truth about the darkness and the light, the terror and the peace, the ineluctable contraries that make up our human existence.”

In American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States, 1820 – 1880 (2002), Andrew Wilton and Tim Barringer comment on the centrality of the Sublime in the Romantic conception of landscape. “The Sublime,” they write, “incorporated a further dimension [namely that] the imagination has an important part to play in our perception of what is immense, nebulous, beyond exact description.” When the percipient discovers “spiritual significance in nature,” he is not making a passive observation; on the contrary, he is participating in the constitution of such significance. Writing of Frederic Church’s panorama in oils of Niagara (1857), Wilton and Barringer remark that, “it is not a meditation on light, but on the power of nature manifested in the grandest geographical phenomena.” They go on to remark that “Church conceived [Niagara] as a show-piece, a masterpiece in the original sense: a specimen of his own powers at their most impressive – a match, perhaps, in a consciously humble way, to God’s own.” Church’s canvass also communicates with the “abyss” of Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” a metaphor of the soul and of the psychic component of the universe as “measureless to man.”

V. Traditionalism as the New Phase of Romanticism. Abrams’ attribution to Wordsworth of a sense of Nature as “apocalyptic” applies equally well to Church (1826 – 1900), for whom the great cataract, directly on the brink of which his painting positions the viewer, is also “apocalyptic” – God revealing His greatness through the sublimity of the falling waters, the magnificent roar, and the rearing luminous mists. Church painted a number of scenes that would have pleased Michell, such as his “Aegean Sea” (1877), with its ancient ruins, including the half-hidden entrance to a cave-shrine, against a brilliantly light island-harbor with mists and rainbows. Church’s “Cross in the Wilderness” (1857), with its rugged mountains and faraway, luminous horizon, implies a Chateaubriand-like grasp of the religious struggle, with its concluding vision, as the essentially human struggle. It probably implies Michell’s ley-lines and megalithic power-foci. The Hudson River School of painting, to which Church belonged, was a thoroughly Romantic phenomenon, motivated by an awareness of the disappearing wilderness, which it sought to record, and dedicated to the ideal that civilization must never violate the natural order; that humbleness before the sublimity of the natural world is the proper attitude for civilized people to assume.

The Lake Poets in England and the Hudson River painters in North America feared the tendencies of their era – the spread of callous industrialism, the aggrandizement of cities, the blighting of the countryside, and the coarsening of the soul. They warned against these trends even as it became evident that the trends would overwhelm any critique. The Lake Poets eventually came to grasp that their philosophical and aesthetic convictions implied a politics. Wordsworth and Coleridge became Tories, or as Americans would say, conservatives. Vigny and Chateaubriand were also on the right, the former describing himself as the sole male survivor of a parental generation that the Revolution had eaten alive. These men would better be described, however, as reactionaries – against the encroachments of the Reign of Quantity and the pseudo-ethos of “getting and spending” – and as Traditionalists: Defenders and conservators of the local against the metropolitan, of dialect against rhetoric, and of the spirit against a prescriptively and intolerantly materialist view of life and the world. Their opposite numbers were the propagandists for the insidious synergy of the laborites and socialists with the bankers and industrialists.

In The Communist Manifesto (1848), Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) and Frederick Engels (1820 – 1895) condemn the bourgeoisie, whom they propose to abolish, but they extol the “subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground” that “Capitalism,” the project of the bourgeoisie, had created. Marx, as much as the industrialists, looked forward to the “extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan” and to the “establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.” Scots poet Robert Burns (1759 – 1796) had already indicted the right riposte in his “Impromptu on the Carron iron Works” (1787):

We cam na here to view your warks,

In hopes to be mair wise,

But only, lest we gang to hell,

It may be nae surprise:

But when we tirl’d at your door

Your porter dought na hear us;

Sae may, shou’d we to Hell’s yetts come,

Your billy Satan sair us!

In the prevailing situation in the second decade of the Twenty-First Century, the literature professors prefer denouncing the Romantic poets to understanding them, and the art-history professors regard the Hudson River painters as “illustrators” who could not possibly have believed in the Transcendentalist or spiritualist doctrines that they expounded. Prophets of modern thought like Theodore Wiesengrund Adorno (1903 – 1969) and Jacques Derrida (1930 – 2004) have, of course, conclusively demonstrated that all Lake Poets and all Hudson River painters, even the ones who were Unitarians hence half-way to being modern liberals, were and remain servitors of false consciousness and an oppressive “logocentrism,” from which everyone should be compulsorily liberated. In the colleges and universities, the Cultural-Marxist hatred for anything not Cultural-Marxist grows red-hot, white-hot, and ultraviolet-hot by swift stages. That is a metonymy of exactly what the early twentieth-Century Traditionalists predicted.

In The End of Our Time (1933), Berdyaev argues that, “The Renaissance began with the affirmation of man’s creative individuality; it has ended with its denial.” Creativity, which Michelangelo and J. S, Bach ascribed to God, produces unequal results that inspire “envy,” which in turn solicits a demand for “equality.” For Berdyaev, the principle of modernity is “envy of the being of another and bitterness at the inability to affirm one’s own.” Thus, according to Berdyaev’s analysis, “Our age is like to that which saw the passing of the ancient world” although “that was the passing of a culture incomparably finer than the culture of today.” It is possible, writes Berdyaev, to “trace the ruin of the Renaissance in modernist art, in Futurism, in philosophy, in Critical Gnoseology… and finally in socialism and anarchism,” all of which begin with a rejection of Romantic, and therefore of religious, values.

In The Meaning of the Creative Act (1916), Berdyaev, contrasting “Canonic” or “pagan” art with “Christian art, or, better, the art of the Christian epoch,” arrives at the dichotomy that “pagan art is classic and immanent” where “Christian art is romantic… and transcendent.” The parallelism between Berdyaev and Chateaubriand will be abundantly self-evident. As Berdyaev sees it, “In [the] classically beautiful perfection of form [in] the pagan world there is no upsurge towards another world… no abyss… above or below”; that is, no “caverns measureless to man.” The Romantic, knowing that he can never achieve perfection in this world, shies from utopian projects that inevitably become coercive and universal. Thus “a romantic incompleteness… characterizes Christian art,” which takes as a premise, among others, the conviction “that final, perfect, eternal beauty is possible only in another world.” That the Romantic often succumbs to the frustration inherent in eternal longing, Berdyaev notes; but the Romantics themselves knew their vulnerability in this regard well and were wont candidly to diagnose it, as Wordsworth does in “The world is too much with us,” candidly. Berdyaev saw in Nineteenth-Century Romanticism the last pause in the steady descent of the Western world into materialism, utilitarianism, and nihilism, the equivalent of Guénon’s Kali Yuga or Dark Age.

Contemporary Traditionalism picks up where Berdyaev, Guénon, and the mid-Twentieth Century anti-modernists, and again where the Romantics, in their century, left off. Traditionalists recognize that the critical situation of their time is deeper, more degraded, more irremediably catastrophic than the of one hundred or one hundred-and-fifty years ago, but they also see that it is the same crisis and that if the Endarkenment of their day were more acute by a magnitude at least than it was in 1820 or 1920 it would also be closer to its irrevocable finale. The problem for Traditionalists is how severe that finale will be. Will it conform itself to the Foundering of Atlantis or the Fall of Rome? The former constituted a choke-point after which civilized life had to begin again from the degree zero. The latter sacrificed the Imperial infrastructure, both physical and bureaucratic, for the reorientation of Western European humanity from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. The Greeks and Romans feared to sail beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Significantly, the conquest of the Atlantic and the opening up of North America fell to those Northwestern Goths, the Vikings, at the very moment when Iceland was embracing Christianity. Leif Erikson was an early convert, as was Thorfinn Karlsefni.

Modernity is a Polyphemus, an angry unison-chorus, shouting like thunder that man is the measure and that there is nothing, not measurable by man. Traditionalism is the quiet voice, seeking parlay with other hushed voices, so that together they might enter conversation with the Forest Murmurs and even the distant Music of the Spheres and come to know better what they already suspect, that man must begin by measuring himself against the measureless.

[This essay is dedicated to Professors Cocks and Presley and to “The Two Scholars.”]

Thomas F. Bertonneau earned a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of Califonia at Los Angeles in 1990. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at SUNY Oswego since 2001. He is the author of three books and numerous articles on literature, art, music, religion, anthropology, film, and politics. He is a frequent contributor to Anthropoetics, the ISI quarterlies, and others.

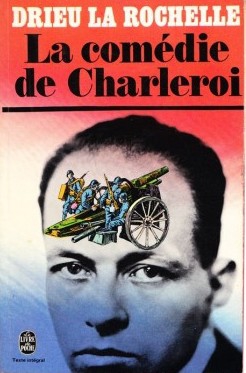

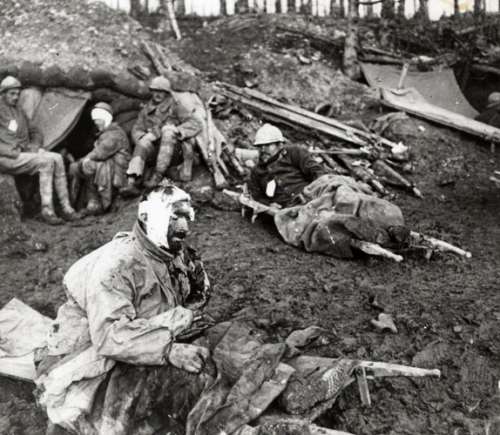

Pierre Drieu la Rochelle n’a éjaculé qu’une seule fois dans sa vie : c’était le 23 août 1914, lors d’une chaude journée de guerre dans la plaine de Charleroi. Ce jour-là, le caporal de 21 ans vit sa première épreuve du feu. Soudain, au milieu de l’affrontement, il se lève, comme s’il n’avait plus peur de la mort, charge son fusil et entraîne plusieurs camarades. L’enivrement que lui procure la sensation d’être devenu le chef qu’il a toujours rêvé d’incarner est comme un orgasme sexuel. « Alors, tout d’un coup, il s’est produit quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Je m’étais levé, levé entre les morts, entre les larves. […] Tout d’un coup, je me connaissais, je connaissais ma vie. C’était donc ma vie, cet ébat qui n’allait plus s’arrêter jamais »*, écrit-il dans La comédie de Charleroi (1934) qui rassemble, sous forme de nouvelles, ses expériences de la Grande Guerre.

Pierre Drieu la Rochelle n’a éjaculé qu’une seule fois dans sa vie : c’était le 23 août 1914, lors d’une chaude journée de guerre dans la plaine de Charleroi. Ce jour-là, le caporal de 21 ans vit sa première épreuve du feu. Soudain, au milieu de l’affrontement, il se lève, comme s’il n’avait plus peur de la mort, charge son fusil et entraîne plusieurs camarades. L’enivrement que lui procure la sensation d’être devenu le chef qu’il a toujours rêvé d’incarner est comme un orgasme sexuel. « Alors, tout d’un coup, il s’est produit quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Je m’étais levé, levé entre les morts, entre les larves. […] Tout d’un coup, je me connaissais, je connaissais ma vie. C’était donc ma vie, cet ébat qui n’allait plus s’arrêter jamais »*, écrit-il dans La comédie de Charleroi (1934) qui rassemble, sous forme de nouvelles, ses expériences de la Grande Guerre.

Lu Pan, de Knut Hamsun. Livre assez extraordinaire, qui reflète la personnalité hors-norme de son auteur. J’ai rarement vu une telle liberté d'esprit, liberté qui touche parfois à la folie, comme dans La Faim, son roman le plus connu. Il m’est toujours un peu difficile de parler de cet écrivain, et je constate à quel point, malheureusement, il est plus aisé de dénigrer que de louer. C’est que les romans d’Hamsun (ceux que j’ai lus du moins) ne ressemblent à rien de connu. Les mécanismes psychologiques s’y montrent à nu, dans leur instantanéité, sans le moindre commentaire, sans le moindre filtre d'un rôle social à jouer. Mais loin de tomber dans le monologue profus et un peu indigeste à la Joyce ou à la Céline, Hamsun, qui appartient à la génération précédente, conserve la forme épurée, presque elliptique, du récit classique. On a donc à la fois le plaisir d'un style classique et la surprise d’une psychologie tout à fait atypique. Et ce qui est admirable, c’est que, contrairement à Dostoïevski qui fouillait les côtés louches de l’âme humaine, Hamsun, doté d’une grande et noble personnalité, se maintient toujours à cette hauteur pour observer le monde. Il voit parfaitement les ridicules des hommes, mais il ne s’attarde pas, son regard reste distant et détaché. Il n’est pas étonnant que Bukowski, après Gide et Henry Miller, le cite parmi ses romanciers préférés. Après l’avoir lu, on se sent plus libre, et on lui a de la gratitude d’éprouver un tel sentiment.

Lu Pan, de Knut Hamsun. Livre assez extraordinaire, qui reflète la personnalité hors-norme de son auteur. J’ai rarement vu une telle liberté d'esprit, liberté qui touche parfois à la folie, comme dans La Faim, son roman le plus connu. Il m’est toujours un peu difficile de parler de cet écrivain, et je constate à quel point, malheureusement, il est plus aisé de dénigrer que de louer. C’est que les romans d’Hamsun (ceux que j’ai lus du moins) ne ressemblent à rien de connu. Les mécanismes psychologiques s’y montrent à nu, dans leur instantanéité, sans le moindre commentaire, sans le moindre filtre d'un rôle social à jouer. Mais loin de tomber dans le monologue profus et un peu indigeste à la Joyce ou à la Céline, Hamsun, qui appartient à la génération précédente, conserve la forme épurée, presque elliptique, du récit classique. On a donc à la fois le plaisir d'un style classique et la surprise d’une psychologie tout à fait atypique. Et ce qui est admirable, c’est que, contrairement à Dostoïevski qui fouillait les côtés louches de l’âme humaine, Hamsun, doté d’une grande et noble personnalité, se maintient toujours à cette hauteur pour observer le monde. Il voit parfaitement les ridicules des hommes, mais il ne s’attarde pas, son regard reste distant et détaché. Il n’est pas étonnant que Bukowski, après Gide et Henry Miller, le cite parmi ses romanciers préférés. Après l’avoir lu, on se sent plus libre, et on lui a de la gratitude d’éprouver un tel sentiment.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

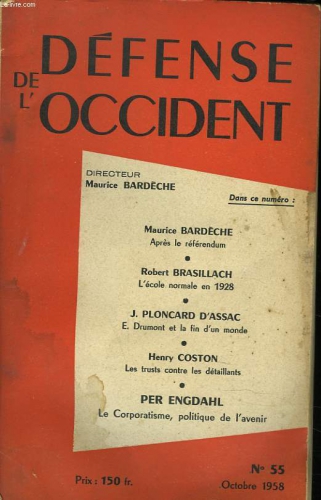

Polémiste, écrivain politique, critique littéraire, Maurice Bardèche (1907-1998) a été tout cela. Son image reste sulfureuse. Elle l’est même beaucoup plus que dans les années 1950, preuve que nous avons fait un grand pas vers le schématisme, l’intolérance et l’inculture. Philippe Junod, aidé de sa femme, a voulu mieux faire connaître celui qui fut le beau-frère et l’ami de Robert Brasillach mais qui avait, bien entendu, son tempérament, ses goûts et son histoire propres. Le pari de mieux connaître Bardèche est tenu dans le cadre des

Polémiste, écrivain politique, critique littéraire, Maurice Bardèche (1907-1998) a été tout cela. Son image reste sulfureuse. Elle l’est même beaucoup plus que dans les années 1950, preuve que nous avons fait un grand pas vers le schématisme, l’intolérance et l’inculture. Philippe Junod, aidé de sa femme, a voulu mieux faire connaître celui qui fut le beau-frère et l’ami de Robert Brasillach mais qui avait, bien entendu, son tempérament, ses goûts et son histoire propres. Le pari de mieux connaître Bardèche est tenu dans le cadre des  Bardèche était non pas un homme de concepts mais un homme de principes. Il été pionnier en maints domaines dans une large mouvance intellectuelle : la critique de la « conscience universelle », c’est-à-dire l’appareil idéologique du nouvel ordre mondial américain, le refus de l’uniformisation planétaire par le règne des marchands, le souci de la liberté des peuples et de la continuité de ceux-ci qui doivent rester fidèles à leurs instincts (thèse assez rousseauiste), l’appel à l’indépendance de l’Europe. Pour des raisons parfaitement évidentes, il était conscient de ne pouvoir être à la bonne distance pour juger de l’action du général de Gaulle. Aussi demandait-il des avis autour de lui. Il faisait partie de ceux qui, à tort ou à raison (je m’interroge moi-même), ne prenait pas au sérieux la troisième voie gaullienne.

Bardèche était non pas un homme de concepts mais un homme de principes. Il été pionnier en maints domaines dans une large mouvance intellectuelle : la critique de la « conscience universelle », c’est-à-dire l’appareil idéologique du nouvel ordre mondial américain, le refus de l’uniformisation planétaire par le règne des marchands, le souci de la liberté des peuples et de la continuité de ceux-ci qui doivent rester fidèles à leurs instincts (thèse assez rousseauiste), l’appel à l’indépendance de l’Europe. Pour des raisons parfaitement évidentes, il était conscient de ne pouvoir être à la bonne distance pour juger de l’action du général de Gaulle. Aussi demandait-il des avis autour de lui. Il faisait partie de ceux qui, à tort ou à raison (je m’interroge moi-même), ne prenait pas au sérieux la troisième voie gaullienne.

Dans les médias, dans les discours des hommes d'Etat occidentaux ou bien dans de nombreux ouvrages spécialisés, le terme de "démocratie" revêt toujours une connotation positive. Ce simple fait est, à lui seul, hautement significatif d'une utilisation idéologique de ce terme. En effet, peut-on imaginer un quelconque système politique ne comportant que des qualités ? La démocratie parlementaire réelle et non point mythique ne fait pas exception à la règle. Elle recèle certes des qualités (autrement dit, des phénomènes qu'une majorité de citoyens perçoivent comme positifs) mais aussi des éléments qui jettent le désarroi dans l'esprit de nos contemporains. Ces éléments constituent en quelque sorte le « revers de la médaille » de notre système politique.

Dans les médias, dans les discours des hommes d'Etat occidentaux ou bien dans de nombreux ouvrages spécialisés, le terme de "démocratie" revêt toujours une connotation positive. Ce simple fait est, à lui seul, hautement significatif d'une utilisation idéologique de ce terme. En effet, peut-on imaginer un quelconque système politique ne comportant que des qualités ? La démocratie parlementaire réelle et non point mythique ne fait pas exception à la règle. Elle recèle certes des qualités (autrement dit, des phénomènes qu'une majorité de citoyens perçoivent comme positifs) mais aussi des éléments qui jettent le désarroi dans l'esprit de nos contemporains. Ces éléments constituent en quelque sorte le « revers de la médaille » de notre système politique.

La politique avant tout, disait Maurras. Parlons plutôt, comme Baudelaire, d’antipolitisme. On sait que le poète, porté, en 1848, par un enthousiasme juvénile, avait participé physiquement aux événements révolutionnaires, appelant même, sans doute pour des raisons peu nobles, à fusiller son beau-père, le général Aupick. Cependant, face à la niaiserie des humanitaristes socialistes, à la suite de la sanglante répression, en juin, de l’insurrection ouvrière (il gardera toujours une tendresse de catholique pour le Pauvre, le Travailleur, et il fut un admirateur du poète et chansonnier populiste Pierre Dupont), et devant le cynisme bourgeois (Cavaignac, le bourreau des insurgés, fut toujours un républicain de gauche), il éprouva et manifesta un violent dégoût pour le monde politique, sa réalité, sa logique, ses mascarades, sa bêtise, qu’il identifiait, comme son contemporain Gustave Flaubert, au monde de la démocratie, du progrès, de la modernité. Ce dégoût est exprimé rudement dans ses brouillons très expressifs, aussi déroutants et puissants que les Pensées de Pascal, Mon cœur mis à nu, et les Fusées, qui appartiennent à ce genre d’écrits littéraires qui rendent presque sûrement intelligent, pour peu qu’on échappe à l’indignation bien pensante.

La politique avant tout, disait Maurras. Parlons plutôt, comme Baudelaire, d’antipolitisme. On sait que le poète, porté, en 1848, par un enthousiasme juvénile, avait participé physiquement aux événements révolutionnaires, appelant même, sans doute pour des raisons peu nobles, à fusiller son beau-père, le général Aupick. Cependant, face à la niaiserie des humanitaristes socialistes, à la suite de la sanglante répression, en juin, de l’insurrection ouvrière (il gardera toujours une tendresse de catholique pour le Pauvre, le Travailleur, et il fut un admirateur du poète et chansonnier populiste Pierre Dupont), et devant le cynisme bourgeois (Cavaignac, le bourreau des insurgés, fut toujours un républicain de gauche), il éprouva et manifesta un violent dégoût pour le monde politique, sa réalité, sa logique, ses mascarades, sa bêtise, qu’il identifiait, comme son contemporain Gustave Flaubert, au monde de la démocratie, du progrès, de la modernité. Ce dégoût est exprimé rudement dans ses brouillons très expressifs, aussi déroutants et puissants que les Pensées de Pascal, Mon cœur mis à nu, et les Fusées, qui appartiennent à ce genre d’écrits littéraires qui rendent presque sûrement intelligent, pour peu qu’on échappe à l’indignation bien pensante.

En 1975, avec Robert Aron, Thierry Maulnier, Roger Bésus, Dominique Jamet et Claude Joubert, elle cosigne une lettre au Monde, où elle s'insurge de l'article d'un universitaire faisant profession d'« aller cracher sur [la] tombe » de Robert Brasillach.

En 1975, avec Robert Aron, Thierry Maulnier, Roger Bésus, Dominique Jamet et Claude Joubert, elle cosigne une lettre au Monde, où elle s'insurge de l'article d'un universitaire faisant profession d'« aller cracher sur [la] tombe » de Robert Brasillach.

Collaborateur régulier aux sites dissidents Europe Maxima, Euro-Synergies et Synthèse nationale, Claude Bourrinet est un penseur impertinent. C’est aussi un remarquable biographe. Vient de paraître sous sa signature un excellent Stendhal dans la collection « Qui suis-je ? ».

Collaborateur régulier aux sites dissidents Europe Maxima, Euro-Synergies et Synthèse nationale, Claude Bourrinet est un penseur impertinent. C’est aussi un remarquable biographe. Vient de paraître sous sa signature un excellent Stendhal dans la collection « Qui suis-je ? ».

This kind of argument, even if it is part of a dialectic, can only be very troubling for Identitarians, who incidentally are portrayed in the book as wanting “Race war now!” while we are still the overwhelming majority in mother Europa. This is not an irrational attitude if a war must occur: there is no question that we grow demographically weaker with every generation in the face of the fatal triad of sub-replacement fertility, displacement-level immigration, and miscegenation.

This kind of argument, even if it is part of a dialectic, can only be very troubling for Identitarians, who incidentally are portrayed in the book as wanting “Race war now!” while we are still the overwhelming majority in mother Europa. This is not an irrational attitude if a war must occur: there is no question that we grow demographically weaker with every generation in the face of the fatal triad of sub-replacement fertility, displacement-level immigration, and miscegenation.

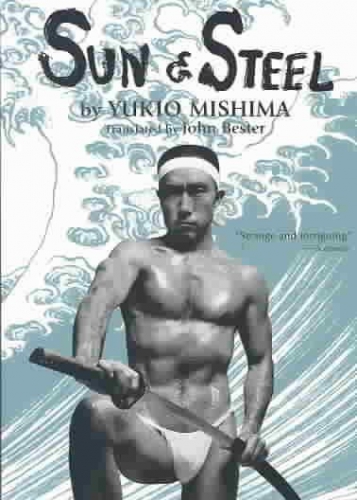

Mishima, nato nel 1925, era molto giovane durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale ma poté partecipare all’ultimo anno di guerra; era scusato. All’epoca deve esser stato ossessionato dall'”uomo d’acciaio”, perché il suo amico Hasuda, collega scrittore, afferma: “Credo che si debba morire giovani, alla sua età”. Hasuda fu fedele alla parola, perché si suicidò. Sembra che l’omosessualità possa anche aver tormentato Mishima, poiché in Confessioni di una maschera (1949) si occupa di emozioni interiori e passioni. Tuttavia, se Mishima conosceva bene la storia di molti samurai, allora avrebbe creduto che l’omosessualità fosse la forma più pura di sesso. Inoltre, molti leader del Giappone nel periodo pre-Edo ed Edo ebbero concubini maschi. Pertanto, Mishima si vergognò dell’etica cristiana arrivata in Giappone con la Restaurazione Meiji (1868)? Se no, allora molti “uomini d’acciaio” del vecchio Giappone ebbero relazioni omosessuali e questo andava inteso alla luce della realtà. Dopo tutto, la lealtà nel vecchio Giappone era per il sovrano daimyo e i compagni samurai. Pertanto, la compassione era ritenuta cosa per deboli, a causa della natura della vita. Non sorprende che forti legami maschili prendessero piede nella psiche dei samurai e tale realtà culturale sia all’opposto dell’immagine dell’omosessualità nel Giappone moderno, percepita per deboli. Il Wakashudo aveva diversi modi di avviare i ragazzi nel “vecchio Giappone” e nella mentalità dei samurai, le donne venivano viste femminilizzare gli uomini indebolendone lo spirito. Il sistema Wakashudo fu spesso abusato dal clero buddista per proprie gratificazioni sessuali, in passato. Tuttavia, il sistema dei samurai si basava sulla creazione di “un processo di apprendimento secondo un codice etico” impiantando lealtà e forti legami per cui, in tempi di difficoltà, i samurai rimasero attaccati all’istruzione ricevuta. Mishima, gonfiando i muscoli e dalle competenze marziali ben levigate, divenne l'”uomo d’acciaio”. Tuttavia, fu contaminato dalle pose femminili fusesi nel suo martirio. Posò volentieri di fronte alle telecamere e le immagini di San Sebastiano ucciso da molte frecce o del samurai che invoca il suicidio rituale, giocarono la sua psiche e il suo essere. Il mondo di Mishima era reale e surreale, perché potere e forza si fusero, ma avendo una natura femminile seppellita nell’anima. Mishima dichiarò: “Il tipo più appropriato di vita quotidiana, per me, fu la quotidiana distruzione mondiale; la pace è il più duro e anormale modo di vivere”. Pertanto, il 25 novembre 1970, si avverò ciò che Mishima era divenuto. Tale realtà si basava su visioni suicide, quindi il suo mondo illusorio sfociò in un fine violenta. Tuttavia, la verità di Mishima fu la fine violenta e caotica entro una realtà struttura. Dopo tutto, Mishima stilò dei piani successivi alla morte. Inoltre, Mishima si dedicò per tale giorno da anni, ma ora il tempo della recitazione era finito, in parte, perché ancora si agitava nel mondo dell'”ego”. Nel suo mondo illusorio il “sé” avrebbe agito collettivamente con forza, a sua volta generando “uno spirito” tratto dal sogno di Mishima di morte glorificata. Eppure, non era un soldato, dopo tutto aveva mentito, non avendo combattuto per il Giappone; quindi, la retorica nazionalista fu proprio tale e il 25 novembre fu più una”redenzione personale” che pose fine alla “dualità della sua anima”. L’uomo delle parole sarebbe morto nel “paradiso dell’estremo dolore”, perché l’ultima sciabolata che lo decapitò non fu netta, furono necessari diversi tentativi. Dopo tutto, non era un soldato, non era un samurai e lo non erano neanche i suoi fedeli seguaci. L’atto finale è la prova che i “sognatori” sono proprio ciò; quindi, il finale non fu una bella immagine di serenità, ma una scena “infernale stupida e di follia autoindotta”. Il mondo illusorio di Mishima non poteva cambiare nulla, perché non riusciva a riscrivere la storia. Sì, dopo di lui si poté riscrivere la storia e forse questa era cui Mishima anelava?

Mishima, nato nel 1925, era molto giovane durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale ma poté partecipare all’ultimo anno di guerra; era scusato. All’epoca deve esser stato ossessionato dall'”uomo d’acciaio”, perché il suo amico Hasuda, collega scrittore, afferma: “Credo che si debba morire giovani, alla sua età”. Hasuda fu fedele alla parola, perché si suicidò. Sembra che l’omosessualità possa anche aver tormentato Mishima, poiché in Confessioni di una maschera (1949) si occupa di emozioni interiori e passioni. Tuttavia, se Mishima conosceva bene la storia di molti samurai, allora avrebbe creduto che l’omosessualità fosse la forma più pura di sesso. Inoltre, molti leader del Giappone nel periodo pre-Edo ed Edo ebbero concubini maschi. Pertanto, Mishima si vergognò dell’etica cristiana arrivata in Giappone con la Restaurazione Meiji (1868)? Se no, allora molti “uomini d’acciaio” del vecchio Giappone ebbero relazioni omosessuali e questo andava inteso alla luce della realtà. Dopo tutto, la lealtà nel vecchio Giappone era per il sovrano daimyo e i compagni samurai. Pertanto, la compassione era ritenuta cosa per deboli, a causa della natura della vita. Non sorprende che forti legami maschili prendessero piede nella psiche dei samurai e tale realtà culturale sia all’opposto dell’immagine dell’omosessualità nel Giappone moderno, percepita per deboli. Il Wakashudo aveva diversi modi di avviare i ragazzi nel “vecchio Giappone” e nella mentalità dei samurai, le donne venivano viste femminilizzare gli uomini indebolendone lo spirito. Il sistema Wakashudo fu spesso abusato dal clero buddista per proprie gratificazioni sessuali, in passato. Tuttavia, il sistema dei samurai si basava sulla creazione di “un processo di apprendimento secondo un codice etico” impiantando lealtà e forti legami per cui, in tempi di difficoltà, i samurai rimasero attaccati all’istruzione ricevuta. Mishima, gonfiando i muscoli e dalle competenze marziali ben levigate, divenne l'”uomo d’acciaio”. Tuttavia, fu contaminato dalle pose femminili fusesi nel suo martirio. Posò volentieri di fronte alle telecamere e le immagini di San Sebastiano ucciso da molte frecce o del samurai che invoca il suicidio rituale, giocarono la sua psiche e il suo essere. Il mondo di Mishima era reale e surreale, perché potere e forza si fusero, ma avendo una natura femminile seppellita nell’anima. Mishima dichiarò: “Il tipo più appropriato di vita quotidiana, per me, fu la quotidiana distruzione mondiale; la pace è il più duro e anormale modo di vivere”. Pertanto, il 25 novembre 1970, si avverò ciò che Mishima era divenuto. Tale realtà si basava su visioni suicide, quindi il suo mondo illusorio sfociò in un fine violenta. Tuttavia, la verità di Mishima fu la fine violenta e caotica entro una realtà struttura. Dopo tutto, Mishima stilò dei piani successivi alla morte. Inoltre, Mishima si dedicò per tale giorno da anni, ma ora il tempo della recitazione era finito, in parte, perché ancora si agitava nel mondo dell'”ego”. Nel suo mondo illusorio il “sé” avrebbe agito collettivamente con forza, a sua volta generando “uno spirito” tratto dal sogno di Mishima di morte glorificata. Eppure, non era un soldato, dopo tutto aveva mentito, non avendo combattuto per il Giappone; quindi, la retorica nazionalista fu proprio tale e il 25 novembre fu più una”redenzione personale” che pose fine alla “dualità della sua anima”. L’uomo delle parole sarebbe morto nel “paradiso dell’estremo dolore”, perché l’ultima sciabolata che lo decapitò non fu netta, furono necessari diversi tentativi. Dopo tutto, non era un soldato, non era un samurai e lo non erano neanche i suoi fedeli seguaci. L’atto finale è la prova che i “sognatori” sono proprio ciò; quindi, il finale non fu una bella immagine di serenità, ma una scena “infernale stupida e di follia autoindotta”. Il mondo illusorio di Mishima non poteva cambiare nulla, perché non riusciva a riscrivere la storia. Sì, dopo di lui si poté riscrivere la storia e forse questa era cui Mishima anelava? Il serait parfaitement inconséquent de restreindre le dandysme – né en Angleterre au XVIIe siècle et dont l’âge d’or pourrait se situer entre les XVIIIe et XIXe siècles – à une simple mode vestimentaire maniériste reconnue pour sa préciosité. Bien plus, il faut y voir l’expression d’une identité paradoxale, d’un attribut psychologique. Entre vice et vertu, grandeur aristocratique et décrépitude, la singulière ambivalence du dandy promet un portrait riche en enseignements.

Il serait parfaitement inconséquent de restreindre le dandysme – né en Angleterre au XVIIe siècle et dont l’âge d’or pourrait se situer entre les XVIIIe et XIXe siècles – à une simple mode vestimentaire maniériste reconnue pour sa préciosité. Bien plus, il faut y voir l’expression d’une identité paradoxale, d’un attribut psychologique. Entre vice et vertu, grandeur aristocratique et décrépitude, la singulière ambivalence du dandy promet un portrait riche en enseignements. De ce qui précède, nous ne pouvons ignorer la place de choix qu’occupe, au sein du dandysme, la sensibilité romantique – Albert Camus ne s’y est pas trompé lorsqu’il fait du dandy un « héros romantique ». Dandysme et beylisme s’accorde majestueusement. D’après Léon Blum « nous trouvons (…) au fond du beylisme ce qui peut-être l’essence de la sensibilité romantique : la persistance vers un but qui, d’avance, est connu comme intangible, l’acharnement vers un idéal, c’est-à-dire vers l’impossible, la dépense consciente de soi-même en pure perte, sans espoir quelconque de récompense ou de retour. Car les âmes assez exigeantes pour aspirer à ce bonheur parfait, ou même surhumain, le sont trop pour accepter en échange les compensations atténuées qui font le lot commun des hommes. La mélancolie romantique est issue de ces thèmes élémentaires : les seuls bonheurs accessibles à l’homme font sa bassesse ; sa noblesse fait sa souffrance ; une fatalité maligne a posé devant lui ce dilemme : la vulgarité innocente qui le ravale à la brute, l’aspiration anxieuse et condamnée qui le hausse vers un ciel inaccessible… ». Cette jolie citation nous rappelle que l’esthétique de soi dévoile un thème propre à la fois au dandysme et au romantisme (Stendhal, Byron et surtout Baudelaire symbolisent la fusion parfaite de ces deux aspects). Qui a mieux exalté que Baudelaire la friction permanente entre le don de soi dans l’art poétique et la transpiration mélancolique ? L’auteur des Fleurs du mal pour qui « le malheur est à la fois une noble distinction et un critère esthétique » (Marie-Christine Natta) a écrit ces mots extraordinaires dans sa lettre à jules Janin : « Vous êtes un homme heureux. Je vous plains, monsieur, d’être si facilement heureux. Faut-il croire qu’un homme soit tombé bas pour se croire heureux ! (…) Je vous plains, et j’estime ma mauvaise humeur plus distinguée que votre béatitude » ; ou encore dans Fusée : « je ne prétends pas que la Joie ne puisse pas s’associer à la Beauté, mais je dis que la Joie (en) est un des ornements les plus vulgaires ; – tandis que la Mélancolie en est pour ainsi dire l’illustre compagne, à ce point que je ne conçois guère (mon cerveau serait-il un miroir ensorcelé ?) un type de Beauté où il n’y ait du Malheur ».

De ce qui précède, nous ne pouvons ignorer la place de choix qu’occupe, au sein du dandysme, la sensibilité romantique – Albert Camus ne s’y est pas trompé lorsqu’il fait du dandy un « héros romantique ». Dandysme et beylisme s’accorde majestueusement. D’après Léon Blum « nous trouvons (…) au fond du beylisme ce qui peut-être l’essence de la sensibilité romantique : la persistance vers un but qui, d’avance, est connu comme intangible, l’acharnement vers un idéal, c’est-à-dire vers l’impossible, la dépense consciente de soi-même en pure perte, sans espoir quelconque de récompense ou de retour. Car les âmes assez exigeantes pour aspirer à ce bonheur parfait, ou même surhumain, le sont trop pour accepter en échange les compensations atténuées qui font le lot commun des hommes. La mélancolie romantique est issue de ces thèmes élémentaires : les seuls bonheurs accessibles à l’homme font sa bassesse ; sa noblesse fait sa souffrance ; une fatalité maligne a posé devant lui ce dilemme : la vulgarité innocente qui le ravale à la brute, l’aspiration anxieuse et condamnée qui le hausse vers un ciel inaccessible… ». Cette jolie citation nous rappelle que l’esthétique de soi dévoile un thème propre à la fois au dandysme et au romantisme (Stendhal, Byron et surtout Baudelaire symbolisent la fusion parfaite de ces deux aspects). Qui a mieux exalté que Baudelaire la friction permanente entre le don de soi dans l’art poétique et la transpiration mélancolique ? L’auteur des Fleurs du mal pour qui « le malheur est à la fois une noble distinction et un critère esthétique » (Marie-Christine Natta) a écrit ces mots extraordinaires dans sa lettre à jules Janin : « Vous êtes un homme heureux. Je vous plains, monsieur, d’être si facilement heureux. Faut-il croire qu’un homme soit tombé bas pour se croire heureux ! (…) Je vous plains, et j’estime ma mauvaise humeur plus distinguée que votre béatitude » ; ou encore dans Fusée : « je ne prétends pas que la Joie ne puisse pas s’associer à la Beauté, mais je dis que la Joie (en) est un des ornements les plus vulgaires ; – tandis que la Mélancolie en est pour ainsi dire l’illustre compagne, à ce point que je ne conçois guère (mon cerveau serait-il un miroir ensorcelé ?) un type de Beauté où il n’y ait du Malheur ». Ce court détour pour rappeler que le dandysme, comme l’a aussi montré Camus, évolue sur le mode de la révolte et non de la révolution. Sartre, dans son Baudelaire, expose le sens de cette nuance : « le révolutionnaire veut changer le monde, il le dépasse vers l’avenir, vers un ordre de valeur qu’il invente ; le révolté à soin de maintenir intacts les abus dont il souffre pour pouvoir se révolter contre eux (…) Il ne veut ni détruire ni dépasser, mais seulement se dresser contre l’ordre. Plus il l’attaque, plus il le respecte obscurément ». Si le dandy a pu pénétrer les milieux aristocratiques les mieux conservés de son temps sans éveiller le moindre rejet (Brummell, par exemple, était membre du cercle du prince George), c’est parce qu’il a su, à la fois, embellir ses déviances et, surtout, ne jamais les revendiquer comme un modèle à suivre : il n’a jamais agité son droit à la reconnaissance et s’est toujours contenté d’une franche indépendance (liberté de de rien vouloir et, par conséquent, de ne rien demander). Le dandy possède cette faculté de transformer un « crime » en vice, une déviance difficilement tolérable (à tort ou à raison) en une fantaisie séduisante ; sa force fut, à la fois, de greffer son cortège de vices sur une nature exceptionnellement distinguée (par son degré d’exigence plastique, intellectuelle et artistique) mais aussi de se maintenir à distance du pouvoir et des revendications politiques, loin, très loin, des lumières criardes de l’ostension révolutionnaire. Peut-être faudrait-il veiller à ne pas oublier cette citation de Benjamin Disraeli : « ce qui est un crime pour le grand nombre n’est qu’un vice pour quelques-uns ». Compte tenu de la nature pécheresse de l’homme, l’harmonie sociale est à ce prix.

Ce court détour pour rappeler que le dandysme, comme l’a aussi montré Camus, évolue sur le mode de la révolte et non de la révolution. Sartre, dans son Baudelaire, expose le sens de cette nuance : « le révolutionnaire veut changer le monde, il le dépasse vers l’avenir, vers un ordre de valeur qu’il invente ; le révolté à soin de maintenir intacts les abus dont il souffre pour pouvoir se révolter contre eux (…) Il ne veut ni détruire ni dépasser, mais seulement se dresser contre l’ordre. Plus il l’attaque, plus il le respecte obscurément ». Si le dandy a pu pénétrer les milieux aristocratiques les mieux conservés de son temps sans éveiller le moindre rejet (Brummell, par exemple, était membre du cercle du prince George), c’est parce qu’il a su, à la fois, embellir ses déviances et, surtout, ne jamais les revendiquer comme un modèle à suivre : il n’a jamais agité son droit à la reconnaissance et s’est toujours contenté d’une franche indépendance (liberté de de rien vouloir et, par conséquent, de ne rien demander). Le dandy possède cette faculté de transformer un « crime » en vice, une déviance difficilement tolérable (à tort ou à raison) en une fantaisie séduisante ; sa force fut, à la fois, de greffer son cortège de vices sur une nature exceptionnellement distinguée (par son degré d’exigence plastique, intellectuelle et artistique) mais aussi de se maintenir à distance du pouvoir et des revendications politiques, loin, très loin, des lumières criardes de l’ostension révolutionnaire. Peut-être faudrait-il veiller à ne pas oublier cette citation de Benjamin Disraeli : « ce qui est un crime pour le grand nombre n’est qu’un vice pour quelques-uns ». Compte tenu de la nature pécheresse de l’homme, l’harmonie sociale est à ce prix.

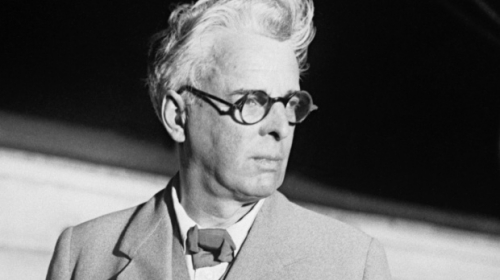

![william-butler-yeats-by-reemerv[162091].jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/01/02/2740805010.jpg) The falcon is modern man. The motive force of the falcon’s flight is human desire, pride, spiritedness, and Faustian striving. The spiral structure of the flight is the intelligible measure–the moderation and moralization of human desire and action–imposed by the moral center of our civilization, represented by the falconer, the falcon’s master, our master, which I interpret in Nietzschean terms as the highest values of our culture. The tether that holds us to the center and allows it to impose measure on our flight is the “voice of God,” i.e., the claim of the values of our civilization upon us; the ability of our civilization’s values to move us.

The falcon is modern man. The motive force of the falcon’s flight is human desire, pride, spiritedness, and Faustian striving. The spiral structure of the flight is the intelligible measure–the moderation and moralization of human desire and action–imposed by the moral center of our civilization, represented by the falconer, the falcon’s master, our master, which I interpret in Nietzschean terms as the highest values of our culture. The tether that holds us to the center and allows it to impose measure on our flight is the “voice of God,” i.e., the claim of the values of our civilization upon us; the ability of our civilization’s values to move us.