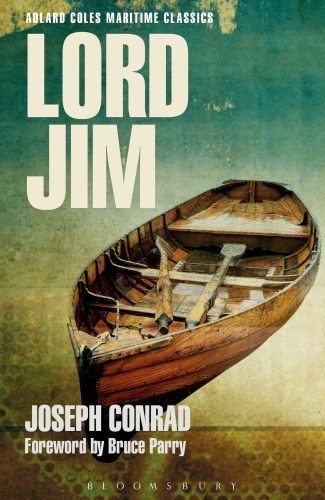

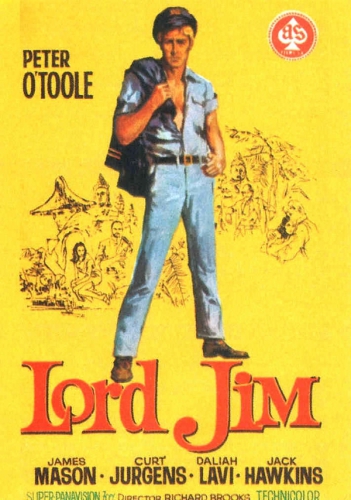

Lord Jim (1900), Joseph Conrad’s fourth novel, is the story of a ship which collides with “a floating derelict” and will doubtlessly “go down at any moment” during a “silent black squall.” The ship, old and rust-eaten, known as the Patna, is voyaging across the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea. Aboard are eight hundred Muslim pilgrims who are being transported to a “holy place, the promise of salvation, the reward of eternal life.” Terror possesses the captain and several of his officers, who jump from the pilgrim-ship and thus wantonly abandon the sleeping passengers who are unaware of their peril. For the crew members in the safety of their life-boat, dishonor is better than death.

Lord Jim (1900), Joseph Conrad’s fourth novel, is the story of a ship which collides with “a floating derelict” and will doubtlessly “go down at any moment” during a “silent black squall.” The ship, old and rust-eaten, known as the Patna, is voyaging across the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea. Aboard are eight hundred Muslim pilgrims who are being transported to a “holy place, the promise of salvation, the reward of eternal life.” Terror possesses the captain and several of his officers, who jump from the pilgrim-ship and thus wantonly abandon the sleeping passengers who are unaware of their peril. For the crew members in the safety of their life-boat, dishonor is better than death.

Beyond the immediate details and the effects of a shipwreck, this novel portrays, in the words of the story’s narrator, Captain Marlow, “those struggles of an individual trying to save from the fire his idea of what his moral identity should be…” That individual is a young seaman, Jim, who serves as the chief mate of the Patna and who also “jumps.” Recurringly Jim envisions himself as “always an example of devotion to duty and as unflinching as a hero in a book.” But his heroic dream of “saving people from sinking ships, cutting away masts in a hurricane, swimming through a surf with a line,” does not square with what he really represents: one who falls from grace, and whose “crime” is “a breach of faith with the community of mankind.” Jim’s aspirations and actions underline the disparity between idea and reality, or what is generally termed “indissoluble contradictions of being.” His is also the story of a man in search of some form of atonement once he recognizes that his “avidity for adventure, and in a sense of many-sided courage,” and his dream of “the success of his imaginary achievements,” constitute a romantic illusion.Jim’s leap from the Patna generates in him a severe moral crisis that forces him to “come round to the view that only a meticulous precision of statement would bring out the true horror behind the appalling face of things.” It is especially hard for Jim to confront this “horror” since his confidence in “his own superiority” seems so absolute. The “Patna affair” compels him in the end to peer into his deepest self and then to relinquish “the charm and innocence of illusions.” The Jim of the Patna undergoes “the ordeal of the fiery furnace,” as he is severely tested “by those events of the sea that show in the light of the day the inner worth of a man, the edge of his temper, and the fibre of his stuff; that reveal the quality of his resistance and the secret truth of his pretences, not only to others but also to himself.” Clearly the Patna is, for Jim, the experience both of a moment and of a lifetime.

This novel, from beginning to end, is the story of Jim; throughout the focus is on his life and character, on what he has done, or not done, on his crime and punishment, his failure of nerve as a seaman. It is, as well, the story of his predicament and his fate, the destiny of his soul—of high expectations and the great “chance missed,” of “wasted opportunity” and “what he had failed to obtain,” all the result of leaving his post, and abdicating his responsibility. Thus we see him in an unending moment of crisis, “over- burdened by the knowledge of an imminent death” as he imagines the grim scene before him: “He stood still looking at those recumbent bodies, a doomed man aware of his fate, surveying the silent company of the dead. They were dead! Nothing could save them!”

For Jim the overwhelming question, “What could I do—what?”, brings the answer of “Nothing!” The Patna, as it ploughs the Arabian Sea (“smooth and cool to the eye like a sheet of ice”) on its way to the Red Sea, is close to sinking, with its engines stopped, the steam blowing off, its deep rumble making “the whole night vibrate like a bass ring.” Jim’s imagination conjures up a dismal picture of a catastrophe that is inescapable and merciless. It is not that Jim thinks so much of saving himself as it is the tyranny of his belief that there are eight hundred people on ship— and only seven lifeboats. Conrad’s storyteller, Marlow, much sympathetic to Jim’s plight, discerns in him an affliction of helplessness that compounds his sense of hopelessness, making Jim incapable of confronting total shipwreck, as he envisions “a ship floating head down, checked in sinking by a sheet of old iron too rotten to stand being shored up.” But Jim is a victim not only of his imagination, but also of what Conrad calls a “moral situation of enslavement.” So torn and defeated is Jim that his soul itself also seems possessed by some “invisible personality, an antagonistic and inseparable partner of his existence.”

Jim’s acceptance of the inevitability of disaster and his belief that he could do absolutely nothing to forestall the loss of eight- hundred passengers render him helpless, robbing him of any ability to take any kind of life-saving action—“…I thought I might just as well stand where I was and wait.” In short, in Jim we discern a disarmed man who surrenders his will to action. The gravity of Jim’s situation is so overwhelming that it leaves him, his heroic aspirations notwithstanding, in a state of paralysis. His predicament, then, becomes his moral isolation and desolation, one in which Jim’s “desire of peace waxes stronger as hope de- clines…and conquers the very desire of life.” He gives in at precisely the point when strenuous effort and decisive actions are mandated, so as to resist “unreasonable forces.” His frame of mind recalls here Jean-Paul Sartre’s pertinent comment, in The Age of Reason (1945), “That’s what existence means: draining one’s own self dry without a sense of thrust.”

Everything in Jim’s background points to his success as a career seaman. We learn that, one of five sons, he originally came from a parsonage, from one of those “abodes of piety and peace,” in England; his vocation for the sea emerged early on and, for a period of two years, he served on a “‘training-ship for affairs of the mercantile marine.’” His station was in the foretop of a training ship chained to her moorings. We learn that, on one occasion, in the dusk of a winter’s day, a gale suddenly blew forth with a savage fury of wind and rain and tide, endangering the small craft on the shore and the ferry-boats anchored in the harbor, as well as the training-ship itself. The force of the gale “made him hold his breath in awe. He stood still. It seemed to him he was whirled around. He was jostled.” We learn, too, that a coaster, in search of shelter, crashed through a schooner at anchor. We see the cutter now tossing abreast the ship, hovering dangerously. Jim is on the point of leaping overboard to save a man overboard, but fails to do so. There is “pain of conscious defeat in his eyes,” as the captain shouts to Jim. “‘Too late, youngster….Better luck next time. This will teach you to be smart.’”

This incident, related in the first chapter of the novel, serves to prepare us for Jim’s actions later on the Patna, and also suggests a kind of flaw in Jim’s behavior in a moment of danger. Early on in his career, then, Jim had displayed a willingness to “flinch” from his obligations, thus revealing a defect in the heroism about which he romanticized and which led him to creating self-serving fantasies and illusions. “He felt angry with the brutal tumult of earth and sky for taking him unawares and checking unfairly a generous readiness for narrow escapes.” Jim, as a seaman, refuses to admit his fear of fear, and in this he shows an inclination to escape the truth of reality by “putting out of sight all the reminders of our folly, of our weakness, of our mortality.” Clearly the episode on the training-ship serves both as a symptom and as a portent, underscores an inherent element of failure and disgrace in Jim’s character that, in the course of the novel, he must confront if he is to transcend the dreams and illusions that beguile him, and that he must finally vanquish if he is to find his “moral identity.” His early experience on the training-ship makes him a marked man. It remains for his experience later on the Patna to make him a “condemned man.”

That nothing rests secure, that, in the midst of certitude, danger lurks, that peace and contentment are at the mercy of the whirl of the world, are inescapable conditions of human existence. These daunting dichotomies, as we find them depicted in Lord Jim, are forever teasing and testing humans in their life-journey. Conrad sees these dichotomies in the unfolding spectacle of man and nature. To evince the enormous power of this process Conrad chooses to render time in a continuum which fills all space. Time has no end, no telos; it absorbs beginnings and endings—the past, present, and future not only in their connections but also in their disconnections.

Conrad’s spatial technique is no less complex, and no less revealing, than his use of time. Hence, he employs spatial dimension so as to highlight Jim’s sense of guilt in jumping from the Patna. A “seaman in exile from the sea,” Jim is constantly in flight when his incognito is repeatedly broken by the knowledge of his Patna connection. For years this “fact followed him casually but inevitably,” whenever and wherever he retreated. Jim’s “keen perception of the Intolerable” finally drives him away for good from seaports and white men, “into the virgin forest, the Malays of the jungle village.” The “acute consciousness of lost honour,” as Conrad expresses it in his Author’s Note, is Jim’s burden of fate. And wherever he retreats he is open to attack from some “deadly snake in every bush.” Time as memory and place as torment be- come his twin oppressors.

The specificities of the Patna episode were to come out during a well-attended Official Court of Inquiry that takes place for several days in early August 1883. Most of the details, in the form of remarks and commentaries, are supplied by Marlow in his long oral narrative, especially as these emerge from Jim’s own confession to Marlow when they happen to meet after the proceedings, on the yellow portico of the Malabar House. Humiliated and bro- ken, his certificate revoked, his career destroyed, Jim can never re- turn to his home and face his father—“‘I could never explain. He wouldn’t understand.’” Again and again, in his confession, Jim shows feelings of desperation and even hysteria: “Everything had betrayed him!” For him it is imperative to be identified neither with the “odious and fleshly” German skipper, Gustav, “the incarnation of everything vile and base that lurks in the world we love,” nor with the chief and the second engineers, “skunks” who are extensions of the captain’s coarseness and cowardice.

But that, in fact, Jim does jump overboard—“a jump into the unknown”—and in effect joins them in deserting the Patna ultimately agonizes his moral sense and impels him to scrutinize that part of his being in which the element of betrayal has entered. By such an action he feels contaminated, unclean, disgraced. How to separate himself morally from the captain and his engineers is still another cruel question to which he must find an answer. In this respect, Jim reminds us of the tragic heroes in ancient Greek drama whose encounters with destiny entail both risks and moral instruction. “We begin to live,” Conrad reminds us, “when we have conceived life as a tragedy.”

How does one “face the darkness”? How does one behave to the unknowable? These are other basic questions that vex Jim. He wants, of course, to answer these questions affirmatively, or at least to wrestle with them in redeeming ways, even as he appears to see himself within a contradiction—as one who can have no place in the universe once he has failed to meet the standards of his moral code. Refusing to accept any “helping hand” extended to him to “clear out,” he decides to “fight this thing down,” to expiate his sin, in short, to suffer penitently the agony of his failure: “He had loved too well to imagine himself a glorious racehorse, and now he was condemned to toil without honour like a costermonger’s donkey.” Jim’s innermost sufferings revolve precisely around his perception of his loss of honor, of his surrender to cowardice. The crushing shame of this perception tortures Jim, without respite. “’I had jumped—hadn’t I?’ he asked [Marlow], dismayed. ‘That’s what I had to live down.’”

Jim’s moral sense is clearly outraged by his actions. This out- rage wracks his high conception of himself, compelling him in time to see himself outside of his reveries that Conrad also associates with “the determination to lounge safely through existence.” What clouds Jim’s fate is that such a net of safety and certitude has no sustained reality. Within the serenity that seemed to bolster his thoughts of “valorous deeds” there are hidden menaces that assault his self-contentment and self-deception and abruptly awaken Jim to his actual condition and circumstances. In one way, it can be said, Jim is a slave of the “idyllic imagination” (as Irving Babbitt calls it), with its expansive appetites, chimeras, reveries, pursuit of illusion. Jim’s is the story of a man who comes to discern not only the pitfalls of this imagination but also the need to free himself from its bondage. But to free himself from bondage requires of Jim painstaking effort, endurance. He must work diligently to transform chimeric, if incipient, fortitude into an active virtue as it interacts with a world that, like the Patna, can be “full of reptiles”—a world in which “not one of us is safe.”

Conrad uses Jim to indicate the moral process of recovery. Conrad delineates the paradigms of this process as these evolve in the midst of much anguish and laceration, leading to the severest scrutiny and judgment of the total human personality. Jim pays attention, in short, to the immobility of his soul; it will take much effort for him to determine where he is and what is happening to him if he is to emerge from the “heart of darkness” and the affliction within and around him to face what is called “the limiting moment.” It is, in an inherently spiritual context, a moment of repulsion when one examines the sin in oneself, and hates it. His sense of repulsion is tantamount to moral renunciation, as he embarks on the path to recovery from the romantic habit of day- dreaming.

In the end Jim comes to despise his condition, acceding as he does to the moral imperative. He accepts the need to see his “trouble” as his own, and he instinctively volunteers to answer questions regarding the Patna by appearing before the Official Court of Inquiry “held in the police court of an Eastern port.” (This actually marks his first encounter with Marlow, who is in attendance and who seems to be sympathetically aware of “his hope- less difficulty.”) He gives his testimony fully, objectively, honestly, as he faces the presiding magistrate. The physical details of Jim’s appearance underscore his urge “to go on talking for truth’s sake, perhaps for his own sake”—“fair of face, big of frame, with young, gloomy eyes, he held his shoulders upright above the box while his soul writhed within him.” Marlow’s reaction to Jim is instinctively positive: “I liked his appearance; he came from the right place; he was one of us.” In striking ways, Jim is a direct contrast to the other members of “the Patna gang”: “They were nobodies,” in Marlow’s words.

It should be recalled here that Jim adamantly refused to help the others put the lifeboat clear of the ship and get it into the water for their escape. Indeed, as Jim insists to Marlow, he wanted to keep his distance from the deserters, for there was “nothing in common between him and these men.” Their frenzied, self-serving actions to abandon the ship and its human cargo infuriated Jim—“‘I loathed them. I hated them.’” The scene depicting the abandonment of the Patna is one filled with “the turmoil of terror,” dramatizing the contrast between Jim and the other officers— between honor and dishonor, loyalty and disloyalty, in short, between aspiration and descent on the larger metaphysical map of human behavior. Jim personifies resistance to the negative as he tries to convey to Marlow “the brooding rancour of his mind into the bare recital of events.” Jim’s excruciating moral effort not to join the others and to ignore their desperate motions is also pictured at a critical moment when he felt the Patna dangerously dip- ping her bows, and then lifting them gently, slowly—“and ever so little.”

The reality of a dangerous situation now seems to be devouring Jim, as he was once again to capitulate to the inner voice of Moral imperative to see “trouble” as one’s own weakness and doubt telling him to “leap” from the Patna. Futility hovers ominously around Jim at this last moment when death arrives in the form of a third engineer “clutch[ing] at the air with raised arms, totter[ing] and collaps[ing].” A terrified, transfixed Jim finds himself stumbling over the legs of the dead man lying on the bridge. And from the lifeboat below three voices yelled out eerily—“one bleated, another screamed, one howled”—imploring the man to jump, not realizing of course that he was dead of a heart attack: “Jump, George! Jump! Oh, jump….We’ll catch you! Jump!…Geo-o-o-orge! Oh, jump!” This desperate, screeching verbal command clearly pierces Jim’s internal condition of fear and terror, just as the ship again seemed to begin a slow plunge, with rain sweeping over her “like a broken sea.” And once again Jim is unable to sustain his refusal to betray his idea of honor. Here his body and soul are caught in the throes of still another “chance missed.”

The assaults of nature on Jim’s outer situation are as vicious at this pivotal point of his life as are the assaults of conscience on his moral sense. These clashing outer and inner elements are clearly pushing Jim to the edge, as heroic aspiration and human frailty wrestle furiously for the possession of his soul. What happens will have permanent consequences for him, as Conrad reveals here, with astonishing power of perception. Here, then, we discern a process of cohesion and dissolution, when Jim’s fate seems to be vibrating unspeakably as he experiences the radical pressures and tensions of his struggle to be more than what he is, or what he aspires to be. Jim, as if replacing the dead officer lying on the deck of the Patna, jumps: “It had happened somehow…,“ Conrad writes. “He had landed partly on somebody and fallen across a thwart.” He was now in the boat with those he loathed; “[h]e had tumbled from a height he could never scale again.” “‘I wished I could die,’” he admits to Marlow. “‘There was no going back. It was as if I had jumped into a well—into an everlasting deep hole.’”

A cold, thick rain and “a pitchy blackness” weigh down the lurching boat; “it was like being swept by a flood through a cavern.” Crouched down in the bows, Jim fearfully discerns the Patna, “just one yellow gleam of the masthead light high up and blurred like a last star ready to dissolve.” And then all is black, as one of the deserters cries out shakily, “‘She’s gone!’” Those in the boat remain quiet, and a strange silence prevails all around them, blurring the sea and the sky, with “nothing to see and nothing to hear.” To Jim it seemed as if everything was gone, all was over. The other three shipmates in the boat mistake him for George, and when they do recognize him they are startled and curse him. The boat itself seems filled with hatred, suspicion, villainy, betrayal. “We were like men walled up quick in a roomy grave,” Jim confides to Marlow.

The boat itself epitomizes abject failure and alienation from mankind. Everything in it and around it mirrors Jim’s schism of soul, “imprisoned in the solitude of the sea.” Through the varying repetition of language and images Conrad accentuates Jim’s distraught inner condition, especially the shame that rages in him for being “in the same boat” with men who exemplify a fellowship of liars. By the time they are picked up just before sunset by the Avondale, the captain and his two officers had already “made up a story” that would sanction their desertion of the Patna, which in fact had not sunk and which, with its pilgrims, had been safely towed to Aden by a French gunboat, eventually to end her days in a breaking-up yard. Unlike the others, Jim would choose to face the full consequences of his actions, “to face it out—alone for my- self—wait for another chance—find out….“

“Jim’s affair” was destined to live on years later in the memories and minds of men, as instanced by Marlow’s chance meeting in a Sydney café with a now elderly French lieutenant who was a boarding-officer from the gunboat and remained on the Patna for thirty hours. For Marlow this meeting was “a moment of vision” that enables him to penetrate more deeply into the events surrounding the Patna as he discusses them with one who had been “there.” The French officer, at this time the third lieutenant on the flagship of the French Pacific squadron, and Marlow, now commanding a merchant vessel, thus share their recollections, from which certain key thoughts emerge, measuring and clarifying the entire affair. The two men here bring to mind a Greek chorus speaking words of wisdom that explain human suffering and tragedy. In essence it is Jim’s predicament that Conrad wants to diagnose here so as to enlist the reader’s understanding, even sympathy. “‘The fear, the fear—look you—it is always there,’” the French officer declares. And he goes on to say to Marlow—all of this with reference to Jim: “‘And what life may be worth…when the Fear vs. honor is gone….I can offer no opinion—because—monsieur—I know nothing of it.’”

For Conrad the task of the novelist is to illuminate “Jim’s case” for the reader’s judgment, and he does this, from diverse angles and levels, in order for the reader to consider all of the evidence, all the ambivalences, antinomies, paradoxes. If for Jim the struggle is to ferret out his true moral identity, for the reader the task is to meditate on what is presented to him and, in the end, to attain a transcendent apprehension of life in time and life in relation to values.[1] Jim is, to repeat, “one of us,” and in him we meet and see ourselves on moral grounds, so to speak.

For Conrad the task of the novelist is to illuminate “Jim’s case” for the reader’s judgment, and he does this, from diverse angles and levels, in order for the reader to consider all of the evidence, all the ambivalences, antinomies, paradoxes. If for Jim the struggle is to ferret out his true moral identity, for the reader the task is to meditate on what is presented to him and, in the end, to attain a transcendent apprehension of life in time and life in relation to values.[1] Jim is, to repeat, “one of us,” and in him we meet and see ourselves on moral grounds, so to speak.

In the final paragraph of his Author’s Note, Conrad is careful to point out that the creation of Jim “is not the product of coldly perverted thinking.” Nor is he “a figure of Northern mists.” In Jim, Conrad sees Everyman. In short, he is the creative outgrowth of what Irving Babbitt terms “the high seriousness of the ethical imagination,” and not of the “idyllic imagination,” with its distortions of human character. In other words, this is the “moral imagination” which “imitates the universal” and reveres the “Permanent Things.” In Jim we participate in and perceive a normative consciousness, as we become increasingly aware of Jim’s purposive function in reflective prose and poetic fiction, aspiring as it does to make transcendence perceptible.[2] Conrad testifies to the force and truth of the principles of a metaphysics of art when, in the concluding sentence of his Author’s Note, he writes about his own chance encounter with the Jim in ourselves: “One morning in the commonplace surroundings of an Eastern roadstead, I saw his form pass by—appealing—significant—under a cloud—perfectly silent. Which is as it should be. It was for me, with all the sympathy of which I was capable, to seek fit words for his meaning. He was ‘one of us.’”

A man of “indomitable resolution,” Jim strikes aside any “plan for evasion” proffered to him by a “helping hand” like Marlow’s. Nothing can tempt him to ignore the consequences of both his decisions and indecisions, which surround him like “deceitful ghosts, austere shades.” Any plan to save him from “degradation, ruin, and despair” he shuns, choosing instead to endure the conditions of homelessness and aloneness. He refuses to identify with any schemes or schemers of a morally insensitive nature. The “deep idea” in him is the moral sense to which he somehow hangs on and the innermost voice to which he listens.

Unfailingly Conrad reveals to us the nature of Jim’s character and will in a “narrative [which] moves through a devious course of identifications and distinctions,” as one critic observes.[3] Thus in the person of Captain Montague Brierly we have a paragon sailing ship skipper, and an august member of the board of inquiry, whose overarching self-satisfaction and self-worth presented to Marlow and to the world itself “a surface as hard as granite.” Unexplainably, however, Brierly commits suicide a week after the official inquiry ended by jumping overboard, less than three days after his vessel left port on his outward passage. It seems, as Marlow believes, that “something akin to fear of the immensity of his contempt for the young man [Jim] under examination, he was probably holding silent inquiry into his own case.” Jim will not go the way of Brierly, whose juxtaposition to Jim, early on in the novel, serves to emphasize the young seaman’s fund of inner strength needed to resist perversion of the moral sense. Unlike Brierly, Jim will not be unjust to himself by trivializing his soul.

Nor will Jim become part of any business scheme that would conveniently divert him from affirming the moral sense. A far- fetched and obviously disastrous business venture (“[a]s good as a gold-mine”), concocted by Marlow’s slight acquaintance, a West Australian by the name of Chester, and his partner, “Holy-Terror Robinson,” further illustrates in Jim the ascendancy of “his fine sensibilities, his fine feelings, his fine longings.” Jim will not be identified with the unsavory Chester any more than he would be identified with the Patna gang. Marlow himself, whatever mixed feelings he may have as to Jim’s weaknesses, intuits that Jim has nobler aspirations than being “thrown to the dogs” and in effect to “slip away into the darkness” with Chester. Jim’s destiny may be tragic, but it is not demeaning or tawdry, which in the end sums up Marlow’s beneficent trust in Jim.

Nor will Jim become part of any business scheme that would conveniently divert him from affirming the moral sense. A far- fetched and obviously disastrous business venture (“[a]s good as a gold-mine”), concocted by Marlow’s slight acquaintance, a West Australian by the name of Chester, and his partner, “Holy-Terror Robinson,” further illustrates in Jim the ascendancy of “his fine sensibilities, his fine feelings, his fine longings.” Jim will not be identified with the unsavory Chester any more than he would be identified with the Patna gang. Marlow himself, whatever mixed feelings he may have as to Jim’s weaknesses, intuits that Jim has nobler aspirations than being “thrown to the dogs” and in effect to “slip away into the darkness” with Chester. Jim’s destiny may be tragic, but it is not demeaning or tawdry, which in the end sums up Marlow’s beneficent trust in Jim.

In a state of disgrace, Jim was to work as a ship-chandler for various firms, but he was always on the run—to Bombay, to Calcutta, to Rangoon, to Penang, to Bangkok, to Batavia, moving from firm to firm, always “under the shadow” of his connection to the Patna “skunks.” Always, too, the paternal Marlow was striving to find “opportunities” for Jim. Persisting in these efforts, Marlow pays a visit to an acquaintance of his, Stein, an aging, successful merchant-adventurer who owns a large inter-island business in the Malay Archipelago with a lot of trading posts in out- of-the-way trading places for collecting produce. Bavarian-born Stein is, for Marlow, “one of the most trustworthy men” who can help to mitigate Jim’s plight. A famous entomologist and a “learned collector” of beetles and butterflies, he lives in Samarang. A sage, as well, he ponders on the problems of human existence: “Man is amazing, but he is not a masterpiece…man is come where he is not wanted, where there is no place for him…,“ he says to Marlow. He goes on to observe that man “wants to be a saint, and he wants to be a devil,” and even sees himself, “in a dream,” “as a very fine fellow—so fine as he can never be….“ Solemnly, he makes this observation, so often quoted from Conrad’s writings: “A man that is born falls into a dream like a man who falls into the sea….The way is to the destructive element submit yourself, and with the exertions of your hands and feet in the water make the deep, deep sea keep you up.”

Marlow’s meeting with Stein provides for a philosophical probing of some of the fundamental ideas and life-issues Conrad presents in Lord Jim. The human condition, no less than the kingdom of nature, is the province of his explorations. His musings on the mysteries of existence ultimately have the aim of enlarging our understanding of Jim’s character and soul. These musings also have the effect of heightening Jim’s struggles to find his true moral identity. Inevitably, abstraction and ambiguity are inherent elements in Stein’s metaphysics, so to speak, even as his persona and physical surroundings merge to project a kind of mystery; his spacious apartment, Marlow recalls, “melted into shapeless gloom like a cavern.” Indeed Marlow’s visit to Stein is like a visit to a medical diagnostician who possesses holistic powers of discernment—“our conference resembled so much a medical consultation—Stein of learned aspect sitting in an arm-chair before his desk….” Stein’s ruminations, hence, have at times an oracular dimension, as “…his voice…seemed to roll voluminous and grave—mellowed by distance.” It is in this solemn atmosphere, and with subdued tones, that Stein delivers his chief pronouncement on Jim: “‘He is romantic—romantic,’ he repeated. ‘And that is very bad—very bad….Very good, too,’ he added.”

Marlow’s meeting with Stein provides for a philosophical probing of some of the fundamental ideas and life-issues Conrad presents in Lord Jim. The human condition, no less than the kingdom of nature, is the province of his explorations. His musings on the mysteries of existence ultimately have the aim of enlarging our understanding of Jim’s character and soul. These musings also have the effect of heightening Jim’s struggles to find his true moral identity. Inevitably, abstraction and ambiguity are inherent elements in Stein’s metaphysics, so to speak, even as his persona and physical surroundings merge to project a kind of mystery; his spacious apartment, Marlow recalls, “melted into shapeless gloom like a cavern.” Indeed Marlow’s visit to Stein is like a visit to a medical diagnostician who possesses holistic powers of discernment—“our conference resembled so much a medical consultation—Stein of learned aspect sitting in an arm-chair before his desk….” Stein’s ruminations, hence, have at times an oracular dimension, as “…his voice…seemed to roll voluminous and grave—mellowed by distance.” It is in this solemn atmosphere, and with subdued tones, that Stein delivers his chief pronouncement on Jim: “‘He is romantic—romantic,’ he repeated. ‘And that is very bad—very bad….Very good, too,’ he added.”

The encounter with Stein assumes, almost at the mid-point of the novel, episodic significance in Jim’s moral destiny, and in the final journey of a soul in torment. Stein’s observations, insightful as they are, hardly penetrate the depths of Jim’s soul, its conditions and circumstances, which defy rational analysis and formulaic prescriptions. The soul has its own life, along with but also beyond the outer life Stein images. It must answer to new demands, undertake new functions, face new situations—and experience new trials. The dark night of the soul is at hand, inexorably, as Jim retreats to Patusan, one of the Malay islands, known to officials in Batavia for “its irregularities and aberrations.” It is as if Jim had now been sent “into a star of the fifth magnitude.” Behind him he leaves his “earthly failings.” “‘Let him creep twenty feet underground and stay there,’” to recall Brierly’s words. In Patusan, at a point of the river forty miles from the sea, Jim will relieve a Portuguese by the name of Cornelius, Stein & Co.’s manager there. It is as if Stein and Marlow had schemed to “tumble” him into another world, “to get him out of the way; out of his own way.” “Disposed” of, Jim thus enters spiritual exile, alone and friendless, a straggler, a hermit in the wilderness of Patusan, where “all sound and all movements in the world seemed to come to an end.”

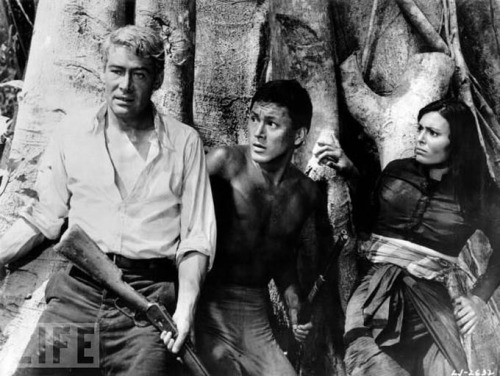

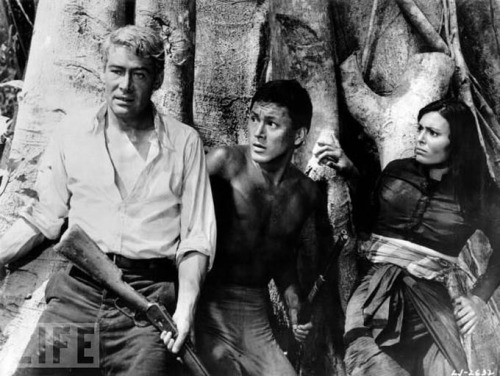

The year in which Jim, now close to thirty years of age, arrives in Patusan is 1886. The political situation there is unstable—“utter insecurity for life and property was the normal condition.” Dirt, stench, and mud-stained natives are the conditions with which Jim must deal. In the midst of all of this rot, Jim, in white apparel, “appeared like a creature not only of another kind but of another essence.” In Patusan, he soon becomes known as Lord Jim (Tuan Jim), and his work gives him “the certitude of rehabilitation.” Patusan, as such, heralds Jim’s unceasing attempt to start with a clean slate. But in Patusan, as on the Patna, Jim is in extreme peril, for he has to grapple with fiercely opposing native factions: the forces of Doramin, Stein’s old friend, chief of the second power in Patusan, and those of Rajah Allang, a brutish chief, constantly locked in quarrels over trade, leading to bloody outbreaks and casualties. Jim’s chief goal was “to conciliate imbecile jealousies, and argue away all sorts of senseless mistrusts.” Doramin and his “distinguished son,” Dain Waris, believe in Jim’s “audacious plan.” But will he succeed, or will he repeat past failures? Is Chester, to recall his earlier verdict on Jim, going to be right: “‘He is no earthly good for anything.’” And will Jim, once and for all, exorcise the “unclean spirits” in himself, with the decisiveness needed for atonement? These are convergent questions that badger Jim in the last three years of his life.

During the Patusan sequence, Jim attains much power and influence: “He dominated the forest, the secular gloom, the old man kind.” As a result of Jim’s leadership, old Doramin’s followers rout their sundry enemies, led not only by the Rajah but also by the vagabond Sherif Ali, an Arab half-breed whose wild men terrorized the land. Jim becomes a legend that gives him even super- natural powers. Lord Jim’s word was now “the one truth of every passing day.” Certainly, from the standpoint of heroic feats and sheer physical courage and example, Jim was to travel a long way from Patna to Patusan. Here his fame is “Immense!…the seal of success upon his words, the conquered ground for the soles of his feet, the blind trust of men, the belief in himself snatched from the fire, the solitude of his achievement.” If his part in the Patna affair led to the derision that pursued him in his flights to nowhere, fame and adoration now define his newly-won greatness. The tarnished first mate of the Patna in the Indian Ocean is now the illustrious Lord Jim of the forests of Patusan.

The difficult situations that Jim must now confront in Patusan demand responsible actions, which Conrad portrays with all their complexities and tensions. There is no pause in Jim’s constant wrestle with responsibilities, whether to the pilgrims on the Patna or the natives in Patusan. The moral pressures on him never ease, requiring of Jim concrete gestures that measure his moral worth. Incessantly he takes moral soundings of himself and of the outer life. The stillness and silences of the physical world have a way of accentuating Jim’s inner anguish. He is profoundly aware that some “floating derelict” is waiting stealthily to strike at the roots of order, whether of man or of society.

In the course of relating the events in Patusan, where he was visiting Jim, Marlow speaks of Jim’s love for a Eurasian girl, Jewel, who becomes his mistress. Cornelius, the “awful Malacca Portuguese,” is Jewel’s legal guardian, having married her late mother after her separation from the father of the girl. A “mean, cowardly scoundrel,” Cornelius is another repulsive beetle in Jim’s life. The enemies from without, like the enemy from within, seem to pursue Jim relentlessly. In Patusan, thus, Cornelius, resentful of being replaced as Stein’s representative in the trading post, hates Jim, never stops slandering him, wants him out of the way: “‘He knows nothing, honourable sir—nothing whatever. Who is he? What does he want here—the big thief?…He is a big fool….He’s no more than a little child here—like a little child—a little child.’” Cornelius asks Marlow to intercede with Jim in his favor, so that he might be awarded some “‘moderate provision—suitable present,’” since “he regarded himself as entitled to some money, in exchange for the girl.” But Marlow is not fazed by Cornelius’s imprecations: “He couldn’t possibly matter…since I had made up my mind that Jim, for whom alone I cared, had at last mastered his fate….“ Nor is Jim himself troubled by Cornelius’s unseemly presence and the possible danger he presents: “It did not matter who suspected him, who trusted him, who loved him, who hated him…. ‘I came here to set my back against the wall, and I am going to stay here,’” Jim insists to Marlow.

In the course of relating the events in Patusan, where he was visiting Jim, Marlow speaks of Jim’s love for a Eurasian girl, Jewel, who becomes his mistress. Cornelius, the “awful Malacca Portuguese,” is Jewel’s legal guardian, having married her late mother after her separation from the father of the girl. A “mean, cowardly scoundrel,” Cornelius is another repulsive beetle in Jim’s life. The enemies from without, like the enemy from within, seem to pursue Jim relentlessly. In Patusan, thus, Cornelius, resentful of being replaced as Stein’s representative in the trading post, hates Jim, never stops slandering him, wants him out of the way: “‘He knows nothing, honourable sir—nothing whatever. Who is he? What does he want here—the big thief?…He is a big fool….He’s no more than a little child here—like a little child—a little child.’” Cornelius asks Marlow to intercede with Jim in his favor, so that he might be awarded some “‘moderate provision—suitable present,’” since “he regarded himself as entitled to some money, in exchange for the girl.” But Marlow is not fazed by Cornelius’s imprecations: “He couldn’t possibly matter…since I had made up my mind that Jim, for whom alone I cared, had at last mastered his fate….“ Nor is Jim himself troubled by Cornelius’s unseemly presence and the possible danger he presents: “It did not matter who suspected him, who trusted him, who loved him, who hated him…. ‘I came here to set my back against the wall, and I am going to stay here,’” Jim insists to Marlow.

The concluding movement of the novel, a kind of andante, conveys a “sense of ending.” Marlow’s long narrative, in fact, is now coming to an end, confluent with his “last talk” with Jim and his own imminent departure from Patusan. The language belongs to the end time, and is pervaded by deepening sorrow and pity, and by an implicit recognition “of the implacable destiny of which we are the victims—and the tools.” A poetry of lamentation takes hold of these pages, and the language is brooding, ominous, recondite. Concurrently, the figure of Cornelius weaves in and out and gives “an inexpressible effect of stealthiness, of dark and secret slinking….His slow, laborious walk resembled the creeping of a repulsive beetle….” We realize that Marlow and Jim will never meet again, as we witness a twilight scene of departure. Having accompanied Marlow as far as the mouth of the river, Jim now watches the schooner taking Marlow to the other world “fall off and gather headway.” Marlow sees Jim’s figure slowly disappearing, “no bigger than a child—then only a speck, a tiny white speck…in a darkened world.”

At the end of the novel, Jim finds himself a prisoner and ultimately a victim of treachery as he fights against invading outcasts and desperadoes who, for any price, kill living life—cutthroats led by “the Scourge of God,” “Gentleman Brown,” a supreme incarnation of evil that Jim must confront. Conrad renders the power of evil in unalleviating ways, even as he sees man’s moral poverty as an inescapable reality. Indeed, what makes Jim’s fate so overpowering is that he never stops struggling against the ruthless forces of destruction that embody Conrad’s vision of evil. What Jim has accomplished in Patusan by creating a more stable social community will now be subject to attack by invaders of “undisguised ruthlessness” who would leave Patusan “strewn over with corpses and enveloped in flames.” If Jim’s inner world, in the first part of the novel, is in turmoil, it is the outer world, in the second part of the novel that is collapsing “into a ruin reeking with blood.” What we hear in the concluding five chapters of Lord Jim is the braying voice of universal discord, crying out with a merciless conviction that, between the men of the Bugis nation living in Patusan and the white marauders, “there would be no faith, no compassion, no speech, no peace.”

The last word of the story of Jim’s life is reserved for one of Marlow’s earlier listeners, “the privileged man,” who receives a thick packet of handwritten materials, of which an explanatory letter by Marlow is the most illuminating. A narrative in epistolary form provides us, two years following the completion of Marlow’s oral narrative, with the details of the last episode that had “come” to Jim. What Marlow has done is to fit together the fragmentary pieces of Jim’s “astounding adventure” so as to record “an intelligible picture” of the last year of his life. The epistolary narrative here is based on the exploit of “a man called Brown,” upon whom Marlow happened to come in a wretched Bangkok hovel a few hours before Brown died. The latter was thus to volunteer information that helped complete the story of Jim’s life, in which Brown himself played a final and fatal role.

The son of a baronet, Brown is famous for leading a “lawless life.” He is “a latter-day buccaneer,” known for his “vehement scorn for mankind at large and for victims in particular.” We learn that he hung around the Philippines in his rotten schooner, which, eventually, “he sails into Jim’s history, a blind accomplice of the Dark Powers.” Their meeting takes place as they face each other across a muddy creek—“standing on the opposite poles of that conception of life which includes all mankind.” This encounter is of enormous consequence, as Jim, “the white lord,” contends verbally with the “terrible,” “sneering” Brown, who slyly invokes their “common blood, an assumption of common experience, a sickening suggestion of common guilt….” The conversation, Marlow was to recall in his letter, appeared “as the deadliest kind of duel on which Fate looked on with her cold-eyed knowledge of the end.” Brown, with his “satanic gift of finding out the best and the weakest spot in his victims,” seems to be surveying and staking out Jim’s character and capability. Jim, on his part, intuitively feels that Brown and his men are “the emissaries with whom the world he had renounced was pursuing him in his retreat.”

Perceiving the potential menace of Brown and his “rapacious” white followers, Jim approaches the entire situation with caution; he knows that there will be either “a clear road or else a clear fight” ahead. His one thought, as he informs Doramin, is “for the people’s good.” Preparations for battle now take place around the fort, and the feeling among the natives is one of anxiety, and also of hope that Jim will somehow resolve everything by convincing Brown that the way back to the sea would be a peaceful one. Jim is convinced “that it would be best to let these whites and their followers go with their lives.” Unwavering as always in meeting his moral obligations, he is primarily concerned with the safety of Patusan. But he underestimates the calculating Brown, again disclosing the propensity that betrays him. Quite simply Jim does not mistrust Brown, believing as he does that both of them want to avoid bloodshed. In this respect, illusion both comforts and victimizes Jim, as the way is made clear for Brown, with the sniveling Cornelius at his side providing him with directions, to withdraw from Patusan, now guarded by Dain Waris’s forces.

Brown’s purpose is not only to escape but also to get even with Jim for not becoming his ally, and to punish the natives for their earlier resistance to his intrusion. When retreating towards the coast his men deceitfully open fire on an outpost of Patusan, killing the surprised and panic-stricken natives, as well as Dain Waris, “the only son of Nakhoda Doramin,” who had earlier acceded to Jim’s request that Brown and his party should be allowed to leave without harm. It could have been otherwise, to be sure, given the superior numbers of the native defenders. Once again, it is made painfully clear, Jim flinches in discernment and in leadership, naïvely trusting in his illusion, in his dream, unaware of the evil power of retribution that impels Brown and that slinks in human-kind. That, too, Brown’s schooner later sprung a bad leak and sank, he himself being the only survivor to be found in a white long-boat, and that the deceitful Cornelius was to be found and struck down by Jim’s ever loyal servant, Tamb’ Itam, can hardly compensate for the destruction and the deaths that took place as a result of Jim’s failure of judgment. Marlow’s earlier demurring remark has a special relevance at this point: “I would have trusted the deck to that youngster [Jim] on the strength of a single glance…but, by Jove! It wouldn’t have been safe.”

Jim’s decision to allow free passage to Brown stems from his concern with preserving an orderly community in Patusan: he did not want to see all his good work and influence destroyed by violent acts. But clearly he had misjudged Brown’s character. Neither Jim’s honesty nor his courage, however, are to be impugned; his moral sense, in this case, is what consciously guided his rational conception of civilization. But a failure of moral vision, induced perhaps by moral pride and romanticism, blinds him to real danger. When Tamb’ Itam returns from the outpost to inform Jim about what has happened, Jim is staggered. He fathoms fully the effects of Brown’s “cruel treachery,” even as he understands that his own safety in Patusan is now at risk, given Dain Waris’s death and Doramin’s dismay and grief over events for which he holds Jim responsible. For Jim the entire situation is untenable, as well as perplexing: “He had retreated from one world for a small matter of an impulsive jump, and now the other, the work of his own hands, had fallen in ruins upon his head.” His feeling of isolation is rending, as he realizes that “he has lost again all men’s confidence.” The “dark powers” have robbed him twice of his peace.

Jim’s decision to allow free passage to Brown stems from his concern with preserving an orderly community in Patusan: he did not want to see all his good work and influence destroyed by violent acts. But clearly he had misjudged Brown’s character. Neither Jim’s honesty nor his courage, however, are to be impugned; his moral sense, in this case, is what consciously guided his rational conception of civilization. But a failure of moral vision, induced perhaps by moral pride and romanticism, blinds him to real danger. When Tamb’ Itam returns from the outpost to inform Jim about what has happened, Jim is staggered. He fathoms fully the effects of Brown’s “cruel treachery,” even as he understands that his own safety in Patusan is now at risk, given Dain Waris’s death and Doramin’s dismay and grief over events for which he holds Jim responsible. For Jim the entire situation is untenable, as well as perplexing: “He had retreated from one world for a small matter of an impulsive jump, and now the other, the work of his own hands, had fallen in ruins upon his head.” His feeling of isolation is rending, as he realizes that “he has lost again all men’s confidence.” The “dark powers” have robbed him twice of his peace.

To Tamb’ Itam’s plea that he should fight for his life against Doramin’s inevitable revenge, Jim bluntly cries, “‘I have no life.’” Jewel, too, “wrestling with him for the possession of her happiness,” also begs him to put up a fight, or try to escape, but Jim does not heed her. “He was going to prove his power in another way and conquer the fatal destiny itself.” This is, truly, “‘a day of evil, an accursed day,’” for Jim and for Patusan. When Dain Waris’s body is brought into Doramin’s campong, the “old nakhoda” was “to let out one great fierce cry…as mighty as the bellow of a wounded bull.” The scene here is harrowing in terms of grief, the women of the household “began to wail together; they mourned with shrill cries; the sun was setting, and in the intervals of screamed lamentations the high sing-song voices of two old men intoning the Koran chanted alone.” The scene is desolate, unconsoling, rendered in the language of apocalypse; the sky over Patusan is blood-red, with “an enormous sun nestled crimson amongst the treetops, and the forest below had a black and forbidding face.” Jim now appears silently before Doramin, who is sitting in his armchair, a pair of flintlock pistols on his knees. “‘I am come in sorrow,’” he cries out to Doramin, who stared at Jim “with an expression of mad pain, of rage, with a ferocious glitter….and lifting deliberately his right [hand], shot his son’s friend through the chest.”

At the end of his explanatory letter Marlow remarks that Jim “passes away under a cloud, inscrutable at heart, forgotten, unforgiven, and excessively romantic.” Such a remark, of course, must be placed in the context of Marlow’s total narrative, with all of the tensions and the ambiguities that occur in relating the story of Jim’s life as it unfolds in the novel. Nor can Marlow’s words here be construed as a moral censure of Jim. What exemplifies Marlow’s narrative, in fact, is the integrity of its content, as the details, reflections, judgments, demurrals emerge with astonishing and attenuating openness, deliberation. There is no single aspect of Jim’s life and character that is not measured and presented in full view of the reader. If judgment is to be made regarding Jim’s situation, Conrad clearly shows, then affirmations and doubts, triumphs and failures will have to be disclosed and evaluated cumulatively.

No one is more mercilessly exposed to the world than Jim. And no one stands more naked before our judgment than he. The scrutiny of Jim’s beliefs and attitudes, and of his actions and inactions, is relentless in depth and latitude. He himself cannot hide or flee, no matter where he happens to be. Marlow well discerns Jim’s supreme aloneness in his struggles to find himself in himself, to master his fate, beyond the calumnies of his enemies and the loyalty and love of his friends—and beyond his own rigorous self-judgments. The anguish of struggle consumes everything and every- one in the novel, and nothing and no one can be the same again once in contact with him. In Jim, it can be said, we see ourselves, for he is “one of us,” he is our “common fate,” which prohibits us to “let him slip away into the darkness.”

From a moral perspective the Official Court of Inquiry literally takes place throughout Lord Jim. Jim never ceases to react to charges of cowardice and of irresponsibility; never ceases to strive earnestly to prove his moral worthiness. He seems never to be in a state of repose, is always under pressure, always examining his pensive state of mind and soul. Self-illumination rather than self- justification, or even self-rehabilitation, is his central aim, and he knows, too, that such a process molds his own efforts and pain. He neither expects nor accepts help or absolution from others, nor does he blame others for his own sins of commission or omission. His character is thus one of singular transparency, acutely self-conscious, and vulnerable.

Jim’s moral sense weighs heavily on him and drives him on sundry, sometimes contradictory, lines of moral awareness and behavior. In this respect he brings to mind the relevance of Edmund Burke’s words: “The lines of morality are not like the ideal lines of mathematics. They are broad and deep as well as long. They admit of exceptions; they demand modifications.”[4] Gnostic commentators who view the moral demands of this novel as confusing or uncertain fail to see that the lines of morality, even when they take different directions and assume different forms, inevitably crystallize in something that is solid in revelation and in value.[5]

Clearly Jim’s high-mindedness and character are problematic, and his scale of human values is excessively romantic. Thus he romanticizes what it means to be a sailor, what duty is, even what cowardice is. The fact is that he is too “noble” to accommodate real-life situations. In essence, then, Jim violates what the ancient Greeks revered as the “law of measure.” And ultimately his pride, his lofty conception of what is required of him in responsible leadership and duty, his high idealism, mar the supreme Hellenic virtue of sophrosyne. Jim’s conduct dramatizes to an “unsafe” degree the extremes of arrogance, and of self-delusion and self-assertion. Above all his idealism becomes a peculiar kind of escape from the paradoxes and antinomies that have to be faced in what Burke calls the “antagonist world.”

In the end, Jim’s habit of detachment and abstraction manifestly rarefies his moral sense and diminishes and even neutralizes the moral meaning of his decisions and actions. His self-proclaimed autonomy dramatizes monomania and egoism, and makes him incapable of harmonious human interrelations, let alone a redeeming humility. His moral sense is consequently incomplete as a paradigm, and his moral virtues are finite. And his fate, as it is defined and shaped by his tragic flaw, does not attain true grandeur. In Jim, it can be said, Conrad presents heroism with all its limitations.[6]

Despite the circumstances of his moral incompleteness, Jim both possesses and enacts the quality of endurance in facing the darkness in himself and in the world around him. Even when he yearns to conceal himself in some forgotten corner of the universe, there to separate himself from other imperfect or fallen humans, from thieves and renegades, and from the harsh exigencies of existence, he also knows that unconditional separation is not attainable. He persists, however erratically or skeptically, in his pursuit to reconcile the order of the community and the order of the soul; and he perseveres in his belief in the axiomatic principles of honor, of loyalty, prescribing the need to transcend inner and outer moral squalor. His death, even if it shows the power of violence, of the evil that stalks man and humanity, of the flaws and foibles that afflict one’s self, does not diminish the abiding example of Jim’s struggle to discover and to overcome moral lapses.

Jim can never silence the indwelling moral sense that inspires and illuminates his life-journey. Throughout this journey the virtue of endurance does not abandon him, does not betray him, even when he betrays himself and others. He endures in order to prevail. In Lord Jim, Joseph Conrad portrays a fitful but ascendant process of transfiguration in the life of a solitary hero whose courage of endurance contains the seeds of redemption. Such a life recalls the eternal promise of the Evangelist’s words: “He that endureth to the end shall be saved.”[7]

Books by George Panichas and Joseph Conrad may be found in The Imaginative Conservative Bookstore. Reprinted with the gracious permission of Modern Age (Spring 1986).

Notes:

- See the chapter “Toward a Metaphysics of Art,” in my book The Reverent Discipline: Essays in Literary Criticism and Culture (Knoxville, Tenn., 1974), 185- 204.

- See Russell Kirk, “The Perversity of Recent Fiction: Reflections on the Moral Imagination,” Redeeming the Time (Wilmington, Del., 1996), 68-86.

- See Dorothy Van Ghent, The English Novel: Form and Function (New York, 1953), 229-244.

- The Philosophy of Edmund Burke: A Selection from His Speeches and Writings, edited and with an introduction by Louis I. Bredvold and Ralph G. Ross (Ann Arbor, 1960), 41.

- See, for example, Douglas Hewitt, “Lord Jim,” Conrad: A Reassessment (Chester Springs, Pa., 1969), 31-39.

- My explication of the ideas found in this and the preceding paragraph owes much to Professor Claes G. Ryn’s discerning and detailed critique of my appraisal of Lord Jim, as found in his letter to me dated March 4, 2000.

- Matthew, 10:22.

Les causes de l’avilissement du langage selon Ezra Pound convergent avec les observations que fit Pasolini quelques années plus tard dans Empirisme Hérétique ; il pointe les dégâts que cause l’Usure, mais aussi le catholicisme qu’il percevait comme une religion castratrice, en prenant comme point d’appui la décadence de Rome qui transforma « de bons citoyens romains en esclaves ». De fait, si Dieu est aussi mort aux yeux de Pound, l’hégémonie culturelle des sociétés modernes est aux mains de la Technique. Si le degré hégémonique de cette dernière indique le niveau de décadence d’une civilisation, Ezra Pound estime que c’est d’abord la littérature, et donc le langage, qui en pâtit la première, car si « Rome s’éleva avec la langue de César, d’Ovide et de Tacite. Elle déclina dans un ramassis de rhétorique, ce langage des diplomates « faits pour cacher la pensée », et ainsi de suite », dit-il dans ABC de la Lecture. La critique d’Ezra Pound ne diffère guère de celle de Bernanos ou de Pasolini sur ce point, outre le fait qu’il aille plus loin dans la critique, n’hésitant pas à fustiger les universités, au moins étasuniennes, comme agents culturels de la Technique, mais aussi l’indifférence navrante de ses contemporains. Le triomphe des Musso, Levy et autre Meyer ne trouve aucune explication logique, tout du moins sous le prisme littéraire. Seules les volontés capitalistes des éditeurs – se cachant sous les jupes du « marché » qu’ils ont pourtant façonné – expliquent leur invasion dans les librairies. Comme il l’affirme dans Comment Lire, « Quand leur travail [des littérateurs, ndlr] se corrompt, et je ne veux pas dire quand ils expriment des pensées malséantes, mais quand leur matière même, l’essence même de leur travail, l’application du mot à la chose, se corrompt, à savoir devient fadasse et inexacte, ou excessive, ou boursouflée, toute la mécanique de la pensée et de l’ordre, socialement et individuellement, s’en va à vau-l’eau. C’est là une leçon de l’Histoire que l’on n’a même pas encore à demi apprise ».

Les causes de l’avilissement du langage selon Ezra Pound convergent avec les observations que fit Pasolini quelques années plus tard dans Empirisme Hérétique ; il pointe les dégâts que cause l’Usure, mais aussi le catholicisme qu’il percevait comme une religion castratrice, en prenant comme point d’appui la décadence de Rome qui transforma « de bons citoyens romains en esclaves ». De fait, si Dieu est aussi mort aux yeux de Pound, l’hégémonie culturelle des sociétés modernes est aux mains de la Technique. Si le degré hégémonique de cette dernière indique le niveau de décadence d’une civilisation, Ezra Pound estime que c’est d’abord la littérature, et donc le langage, qui en pâtit la première, car si « Rome s’éleva avec la langue de César, d’Ovide et de Tacite. Elle déclina dans un ramassis de rhétorique, ce langage des diplomates « faits pour cacher la pensée », et ainsi de suite », dit-il dans ABC de la Lecture. La critique d’Ezra Pound ne diffère guère de celle de Bernanos ou de Pasolini sur ce point, outre le fait qu’il aille plus loin dans la critique, n’hésitant pas à fustiger les universités, au moins étasuniennes, comme agents culturels de la Technique, mais aussi l’indifférence navrante de ses contemporains. Le triomphe des Musso, Levy et autre Meyer ne trouve aucune explication logique, tout du moins sous le prisme littéraire. Seules les volontés capitalistes des éditeurs – se cachant sous les jupes du « marché » qu’ils ont pourtant façonné – expliquent leur invasion dans les librairies. Comme il l’affirme dans Comment Lire, « Quand leur travail [des littérateurs, ndlr] se corrompt, et je ne veux pas dire quand ils expriment des pensées malséantes, mais quand leur matière même, l’essence même de leur travail, l’application du mot à la chose, se corrompt, à savoir devient fadasse et inexacte, ou excessive, ou boursouflée, toute la mécanique de la pensée et de l’ordre, socialement et individuellement, s’en va à vau-l’eau. C’est là une leçon de l’Histoire que l’on n’a même pas encore à demi apprise ». Cette glorification de la médiocrité, Ezra Pound la voyait d’autant plus dans la reproduction hédoniste à laquelle s’adonnent certains scribouillards dans le but de connaître un succès commercial. Aujourd’hui, plus que jamais, la réussite d’un genre littéraire entraîne une surproduction incestueuse de ce même genre, comme c’est notamment le cas en littérature de fantaisie, où l’on vampirise encore Tolkien avec autant de vergogne qu’un charognard. Si la « technicisation » de la littérature comme moyen créatif, ou plutôt en lieu et place de toute création, devient la norme, alors, comme le remarquait plus tard Pasolini, cela débouche sur une extrême uniformisation du langage, dans une forme déracinée, qui efface petit à petit les formes sophistiquées ou argotiques d’une langue au profit d’un galimatias bon pour les robots qui présentent le journal télé comme on lirait un manuel technique. Les vestiges d’une ancienne époque littéraire ne sont plus que le fait de compilations hors de prix et d’hommages ataviques afin de les présenter au public comme d’antiques œuvres dignes d’un musée : belles à regarder, mais réactionnaires si elles venaient à redevenir un modèle. Ezra Pound disait que « le classique est le nouveau qui reste nouveau », non pas la recherche stérile d’originalité qui agite la modernité comme une sorte de tautologie maladive.

Cette glorification de la médiocrité, Ezra Pound la voyait d’autant plus dans la reproduction hédoniste à laquelle s’adonnent certains scribouillards dans le but de connaître un succès commercial. Aujourd’hui, plus que jamais, la réussite d’un genre littéraire entraîne une surproduction incestueuse de ce même genre, comme c’est notamment le cas en littérature de fantaisie, où l’on vampirise encore Tolkien avec autant de vergogne qu’un charognard. Si la « technicisation » de la littérature comme moyen créatif, ou plutôt en lieu et place de toute création, devient la norme, alors, comme le remarquait plus tard Pasolini, cela débouche sur une extrême uniformisation du langage, dans une forme déracinée, qui efface petit à petit les formes sophistiquées ou argotiques d’une langue au profit d’un galimatias bon pour les robots qui présentent le journal télé comme on lirait un manuel technique. Les vestiges d’une ancienne époque littéraire ne sont plus que le fait de compilations hors de prix et d’hommages ataviques afin de les présenter au public comme d’antiques œuvres dignes d’un musée : belles à regarder, mais réactionnaires si elles venaient à redevenir un modèle. Ezra Pound disait que « le classique est le nouveau qui reste nouveau », non pas la recherche stérile d’originalité qui agite la modernité comme une sorte de tautologie maladive.

Il s’est absenté il y a six ans déjà. Je pense bien souvent à lui, donc j’en reparle dans ces lignes. J’ai été le dernier à le prendre en photo. Ma femme Tatiana aussi nous prit en photo, je semblai plus fatigué que lui à la veille de sa mort. Comme dit Shakespeare après Azincourt,

Il s’est absenté il y a six ans déjà. Je pense bien souvent à lui, donc j’en reparle dans ces lignes. J’ai été le dernier à le prendre en photo. Ma femme Tatiana aussi nous prit en photo, je semblai plus fatigué que lui à la veille de sa mort. Comme dit Shakespeare après Azincourt,  En 93, tout a changé : je suis allé en Inde d’où je lui écrivais. L’Inde était encore un peu l’Inde. Ce n'était pas Slumdog dollar. Son texte sur Goa dans la spirale est fantastique. Mais de retour en France les années ont recommencé à passer. On l’aura vu dans l’arbre, le maire et la médiathèque, filmé par son protecteur Rohmer face au bizarre photographe ou plouc crétin qui avait détourné l’attention de l’héritière l’Oréal. Jean lui évoque le Mitterrand d’extrême-droite sans guère le convaincre ; mais j’ai compris qu’en réalité il ne convainquait personne ou presque. Quel dommage ! Et les milliards de l’Oréal !

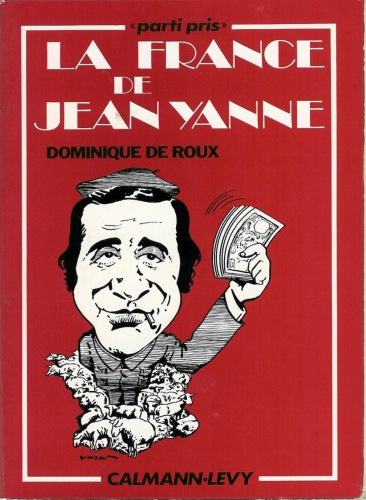

En 93, tout a changé : je suis allé en Inde d’où je lui écrivais. L’Inde était encore un peu l’Inde. Ce n'était pas Slumdog dollar. Son texte sur Goa dans la spirale est fantastique. Mais de retour en France les années ont recommencé à passer. On l’aura vu dans l’arbre, le maire et la médiathèque, filmé par son protecteur Rohmer face au bizarre photographe ou plouc crétin qui avait détourné l’attention de l’héritière l’Oréal. Jean lui évoque le Mitterrand d’extrême-droite sans guère le convaincre ; mais j’ai compris qu’en réalité il ne convainquait personne ou presque. Quel dommage ! Et les milliards de l’Oréal ! Pierre-André Boutang, le fils de l’helléniste maurrassien qui exaspérait Bernanos, lui donna un jour sa chance à la télé, et pour une heure. Il parla bien, échappa au public. Pour les idées et surtout pour la réussite médiatique (on était avant la tyrannie absolue et folle d’aujourd’hui), Jean fut mon maître à penser et surtout à dépenser… Il aimait aussi beaucoup ce film intitulé l’Ultime souper, où l’on voit des gauchistes empoisonner tous leurs ennemis politiques pour se retrouver bien seuls. Le nouvel ordre mondial est gastronomique. Il vous empoisonne. Ces artilleurs culinaires ne savent même faire que cela.

Pierre-André Boutang, le fils de l’helléniste maurrassien qui exaspérait Bernanos, lui donna un jour sa chance à la télé, et pour une heure. Il parla bien, échappa au public. Pour les idées et surtout pour la réussite médiatique (on était avant la tyrannie absolue et folle d’aujourd’hui), Jean fut mon maître à penser et surtout à dépenser… Il aimait aussi beaucoup ce film intitulé l’Ultime souper, où l’on voit des gauchistes empoisonner tous leurs ennemis politiques pour se retrouver bien seuls. Le nouvel ordre mondial est gastronomique. Il vous empoisonne. Ces artilleurs culinaires ne savent même faire que cela.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

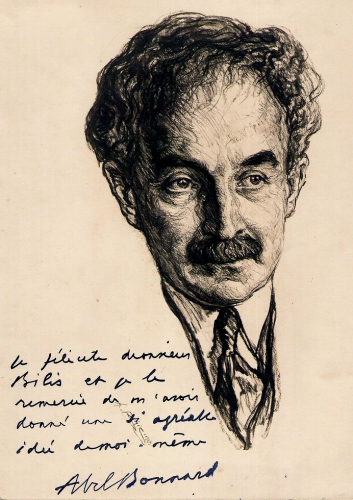

La France selon Abel Bonnard est une entité organique, y compris même (en fait : surtout) lorsqu'elle est démembrée : «La France ne se sera rendue vraiment apte à se donner une meilleure organisation que lorsqu'elle regardera le régime dont elle se plaint comme l'expression obscène des défauts qu'elle a accepté de garder sourdement en elle, et comme la place visible où s'avoue un mal profond» (1).

La France selon Abel Bonnard est une entité organique, y compris même (en fait : surtout) lorsqu'elle est démembrée : «La France ne se sera rendue vraiment apte à se donner une meilleure organisation que lorsqu'elle regardera le régime dont elle se plaint comme l'expression obscène des défauts qu'elle a accepté de garder sourdement en elle, et comme la place visible où s'avoue un mal profond» (1). C'est la continuité de «la civilisation humaine» (p. 40) que la Révolution a brisée, alors que la royauté se faisait un devoir de la respecter : «Tels étaient les sentiments auxquels un Roi de France eût été obligé par sa fonction, alors même qu'il n'y aurait pas été porté par son caractère, dans une organisation où le pouvoir politique, bien loin de prétendre fixer lui-même les valeurs morales, se piquait au contraire d'honorer plus que personne celles qu'il n'avait pas établies» (pp. 38-9). Et Abel Bonnard d'illustrer par un long passage la vertu de l'Ancien Régime, chaîne ininterrompue de mérites, de bassesses et de médiocrités sans doute, mais surtout d'une vision verticale, capable de transcender les petites misères si bassement politiques qui forment la glu pourrie de notre époque : «Quand Harel, bonapartiste déclaré et qui, comme tel, avait âprement combattu la Restauration, brigua en 1829 la direction de l'Odéon, théâtre royal, on ne trouva pas de meilleur moyen de le recommander à Charles X que de faire valoir le dévouement qu'il avait montré pour l'Empereur tombé et Harel, en effet, eut son privilège. Quand Hyde de Neuville, en 1829, ministre du même roi, désire le faire revenir d'un choix qu'il a déjà fait, pour nommer à une place vacante l'officier de marine Bisson, il raconte au souverain la résolution et le courage que Bisson a montrés à Rochefort, en 1815, en offrant à Napoléon de lui faire percer la croisière anglaise, et cela décide Charles X. Tels étaient les sentiments, conclut Abel Bonnard, auxquels un Roi de France eût été obligé par sa fonction, alors même qu'il n'y aurait pas été porté par son caractère, dans une organisation où le pouvoir politique, bien loin de prétendre fixer lui-même les valeurs morales, se piquait au contraire d'honorer plus que personne celles qu'il n'avait pas établies» (pp. 38-9).

C'est la continuité de «la civilisation humaine» (p. 40) que la Révolution a brisée, alors que la royauté se faisait un devoir de la respecter : «Tels étaient les sentiments auxquels un Roi de France eût été obligé par sa fonction, alors même qu'il n'y aurait pas été porté par son caractère, dans une organisation où le pouvoir politique, bien loin de prétendre fixer lui-même les valeurs morales, se piquait au contraire d'honorer plus que personne celles qu'il n'avait pas établies» (pp. 38-9). Et Abel Bonnard d'illustrer par un long passage la vertu de l'Ancien Régime, chaîne ininterrompue de mérites, de bassesses et de médiocrités sans doute, mais surtout d'une vision verticale, capable de transcender les petites misères si bassement politiques qui forment la glu pourrie de notre époque : «Quand Harel, bonapartiste déclaré et qui, comme tel, avait âprement combattu la Restauration, brigua en 1829 la direction de l'Odéon, théâtre royal, on ne trouva pas de meilleur moyen de le recommander à Charles X que de faire valoir le dévouement qu'il avait montré pour l'Empereur tombé et Harel, en effet, eut son privilège. Quand Hyde de Neuville, en 1829, ministre du même roi, désire le faire revenir d'un choix qu'il a déjà fait, pour nommer à une place vacante l'officier de marine Bisson, il raconte au souverain la résolution et le courage que Bisson a montrés à Rochefort, en 1815, en offrant à Napoléon de lui faire percer la croisière anglaise, et cela décide Charles X. Tels étaient les sentiments, conclut Abel Bonnard, auxquels un Roi de France eût été obligé par sa fonction, alors même qu'il n'y aurait pas été porté par son caractère, dans une organisation où le pouvoir politique, bien loin de prétendre fixer lui-même les valeurs morales, se piquait au contraire d'honorer plus que personne celles qu'il n'avait pas établies» (pp. 38-9).  Toutefois, le salut réside peut-être, nous dit Bonnard, dans la présence, au sein d'une société devenue tout entière modérée, c'est-à-dire composée d'individus (belle défini comme étant «l'homme réduit par l'exigence de la vanité à l'indigence du Moi, aussi séparé de la modestie que de la grandeur», p. 248), de quelques réactionnaires, puisque certaines «âmes sont comme ces grains de blé toujours féconds que les archéologues trouvent dans les tombes de l'Égypte antique : elles se conservent dans le passé pour être semées dans l'avenir» (p. 122).

Toutefois, le salut réside peut-être, nous dit Bonnard, dans la présence, au sein d'une société devenue tout entière modérée, c'est-à-dire composée d'individus (belle défini comme étant «l'homme réduit par l'exigence de la vanité à l'indigence du Moi, aussi séparé de la modestie que de la grandeur», p. 248), de quelques réactionnaires, puisque certaines «âmes sont comme ces grains de blé toujours féconds que les archéologues trouvent dans les tombes de l'Égypte antique : elles se conservent dans le passé pour être semées dans l'avenir» (p. 122).  Toutefois, la Révolution, selon l'auteur, «est par essence incapable de procurer à ses partisans ni les plus hautes, ni les plus profondes des joies qu'on trouve dans l'amour de l'ordre, mais on s'expliquerait mal sa puissance, si l'on n'avait pas compris que, dans le monde décomposé d'aujourd'hui, elle dispense à ceux qu'elle asservit le rudiment informe et honteux des jouissances que l'ordre assure à ceux qui le servent. Les révolutionnaires appartiennent encore au désordre par la volupté de détruire, mais ils rentrent malgré eux dans l'ordre par le bonheur d'obéir» (pp. 177-8). Ainsi, les «révolutions sont les temps de l'humiliation de l'homme et les moments les plus matériels de l'histoire. Elles marquent moins la revanche des malheureux que celle des inférieurs. Ce sont des drames énormes dont les acteurs sont très petits» (p. 181), ce constat étant suivi de quelques portraits sans la moindre complaisance des révolutionnaires français les plus connus.

Toutefois, la Révolution, selon l'auteur, «est par essence incapable de procurer à ses partisans ni les plus hautes, ni les plus profondes des joies qu'on trouve dans l'amour de l'ordre, mais on s'expliquerait mal sa puissance, si l'on n'avait pas compris que, dans le monde décomposé d'aujourd'hui, elle dispense à ceux qu'elle asservit le rudiment informe et honteux des jouissances que l'ordre assure à ceux qui le servent. Les révolutionnaires appartiennent encore au désordre par la volupté de détruire, mais ils rentrent malgré eux dans l'ordre par le bonheur d'obéir» (pp. 177-8). Ainsi, les «révolutions sont les temps de l'humiliation de l'homme et les moments les plus matériels de l'histoire. Elles marquent moins la revanche des malheureux que celle des inférieurs. Ce sont des drames énormes dont les acteurs sont très petits» (p. 181), ce constat étant suivi de quelques portraits sans la moindre complaisance des révolutionnaires français les plus connus. Nous en sommes là, et force est d'admettre que la situation présente, dans ses grandes lignes du moins, n'a pas beaucoup changé, a même, sans doute, empiré, depuis l'époque où Abel Bonnard a écrit son pamphlet aussi juste et beau qu'implacable, droite et gauche confondues dans une même critique dont la hauteur et la puissance impressionnent : «Les circonstances où nous sommes auront paru vainement, si elles ne donnent pas lieu à une rentrée de l'homme. Les crises ne font jamais que nous sommer d'être nous-mêmes; les choses aboient autour de nous pour provoquer quelqu'un qui les dompte, et cette même clameur qui donne aux âmes lâches l'envie de s'enfuir donne aux âmes fortes celle de se montrer» (p. 290, je souligne).

Nous en sommes là, et force est d'admettre que la situation présente, dans ses grandes lignes du moins, n'a pas beaucoup changé, a même, sans doute, empiré, depuis l'époque où Abel Bonnard a écrit son pamphlet aussi juste et beau qu'implacable, droite et gauche confondues dans une même critique dont la hauteur et la puissance impressionnent : «Les circonstances où nous sommes auront paru vainement, si elles ne donnent pas lieu à une rentrée de l'homme. Les crises ne font jamais que nous sommer d'être nous-mêmes; les choses aboient autour de nous pour provoquer quelqu'un qui les dompte, et cette même clameur qui donne aux âmes lâches l'envie de s'enfuir donne aux âmes fortes celle de se montrer» (p. 290, je souligne).

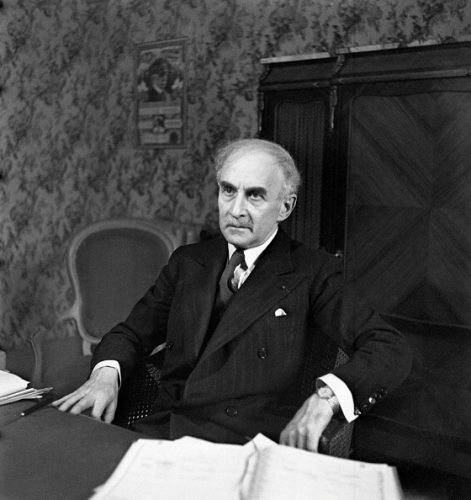

Ecrite par son fils, Jean-Pierre Cousteau, la présente biographie se base sur un corpus de documents souvent inédits, à savoir la correspondance de PAC (avec sa femme lorsqu'il était détenu mais pas seulement) et son journal de prison (Intra muros, qui devrait être publié prochainement pour la première fois). Si l'auteur s'efforce de rester objectif quant au parcours et aux choix de son père, son témoignage est évidemment emprunt d'amour filial mais aussi d'une certaine fierté exprimée très élégamment. Et il peut être fier : PAC n'était pas n'importe qui !