Racines historiques de la théorie des « deux nations » en Inde

Par Daniele Perra

Ex: https://www.eurasia-rivista.com/

"Nous ne sommes pas des Afghans ni des Tartares ou des Turcs,

nous sommes nés d'un seul jardin, d'une seule branche bourgeonnante.

Distinguer les couleurs et les odeurs est une faute grave pour nous,

car nous avons tous, un seul et unique, engendré le printemps".

(M. Iqbal, quatrain XX, Messages de l'Orient)

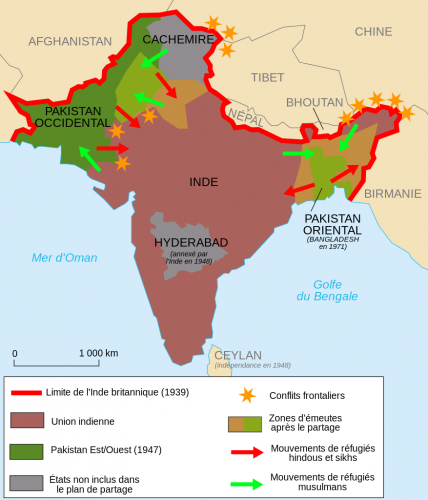

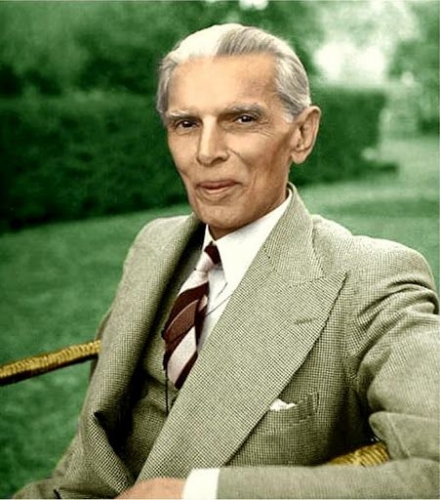

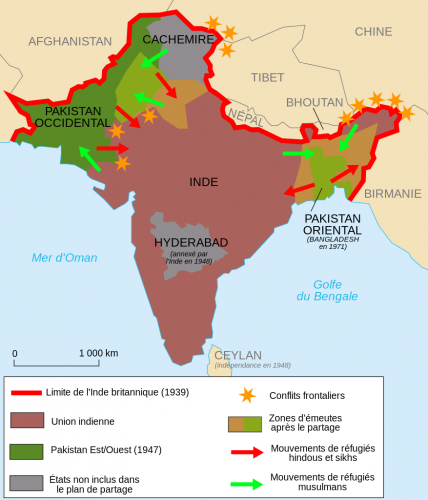

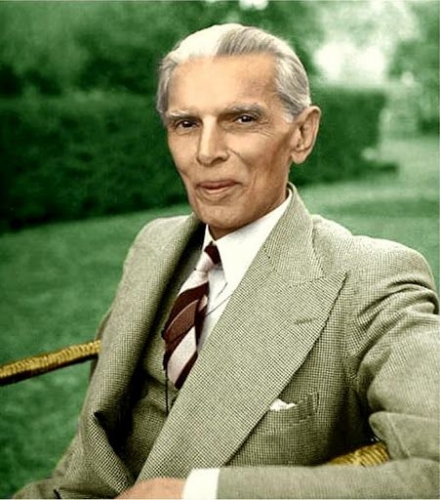

L'idée de deux nations distinctes dans le sous-continent indien n'a pas accompagné tout le parcours politique de Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Ce ne fut le cas qu'à partir du milieu des années 1930, face à la crainte que le nationalisme indien ne se transforme rapidement en nationalisme hindou (l'adoption du Vande Mataram comme hymne du Congrès inquiète Jinnah, qui y voit un chant "idolâtre" fondé sur la "haine des musulmans") [1]. C’est alors que cette idée prend une place prépondérante dans la pensée du père fondateur du Pakistan. Et Jinnah lui-même était fermement convaincu que cette idée n'était pas nouvelle du tout. En fait, elle n'est pas un produit de la modernité, mais est née au moment même où le premier hindou, également pour échapper au système rigide des castes, s'est converti à l'Islam.

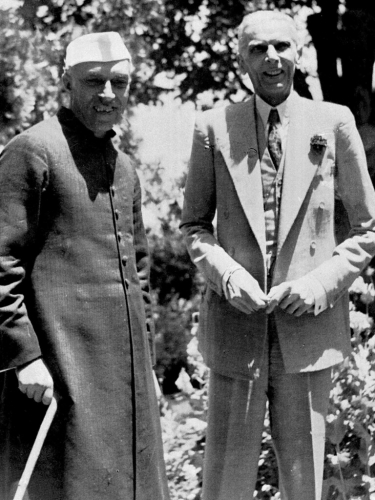

Ali Jinnah.

L'idée que la théorie des deux nations a une origine prémoderne, bien qu'elle ne soit pas articulée en référence au concept moderne d'État-nation, n'est pas sans fondement. À la veille de la deuxième bataille de Tarain, le sultan des Ghurides [2] Mu'izz al-Din suggère à son rival, le souverain hindou Prithiviraj du Chahamana, une sorte de partition ante litteram par une division de l'Hindoustan qui anticipe largement les idées proposées par Muhammad Iqbal dans son discours d'Allahabad en 1930. Selon l'historien persan Firishta (1560-1620), les musulmans avaient droit à la région de Sirhind, au Punjab et au Multan, tandis que les hindous avaient droit au reste de l'espace subcontinental.

L'idée que les hindous et les musulmans représentaient inévitablement deux communautés distinctes, difficiles à faire coexister l'une avec l'autre, était récurrente à l'époque moghole.

La dynastie d'origine turco-mongole, bien qu'adhérant formellement au courant sunnite de l’islam (de rite juridique hanafite), a eu un rapport assez complexe (et en phases alternées) avec la religion. La religion, en fait, a été conçue principalement comme un instrument du pouvoir politico-militaire. Babur (1483-1530), fondateur de la famille impériale, par exemple, n'a redécouvert la ferveur religieuse que lorsqu'il était sur le point de faire la guerre aux Rajputs belliqueux de Rana Sanga : des guerriers hindous connus pour la pratique consistant à tuer leurs propres femmes et enfants dans l'imminence d'une défaite pour éviter d'être réduits en esclavage par les vainqueurs. Ainsi, à l'approche de la bataille de Khanua (1527), Babur déclara solennellement à ses hommes :

"Nobles et soldats! Celui qui participe à la fête de la vie doit, avant la fin, boire à la coupe de la mort. Il vaut donc mieux mourir avec honneur que de vivre dans l'infamie. Le Très-Haut nous a fait grâce. Il nous a maintenant placés dans une situation où, si nous tombons au combat, nous mourrons en martyrs; si nous survivons, nous serons les vengeurs victorieux de Sa Sainte Cause. Nous jurons donc d'un commun accord sur la Sainte Parole de Dieu [le Coran] qu'aucun d'entre nous ne pensera même un seul instant à tourner le dos à cette guerre; ou à se retirer de la bataille et du massacre qui suivra jusqu'à ce que son âme soit séparée de son corps "[3].

Akbar le Grand.

Toujours à l'époque moghole, bien que sous le règne d'Akbar (petit-fils de Babur), l'idée d'incompatibilité entre hindous et musulmans a trouvé une nouvelle fortune avec la prédication d'Ahmad al-Faruqi al-Sirhindi (1564-1624). Membre de la confrérie Naqshabandi, Sirhindi a non seulement théorisé l'interdépendance entre les pratiques soufies et la Shari'a, mais, malgré les critiques des milieux orthodoxes, a soutenu la supériorité de la Réalité du Coran (haqiqat-i quran) et de la Réalité de la Ka'ba sur la Réalité du Prophète (haqiqat-i Muhammadi); cette doctrine aura une influence décisive sur le développement des théories de l'exégèse coranique et de la méthodologie du philosophe pakistanais Fazlur Rahman Malik (1919-1988). Ravivant la tension constante dans l'histoire de l'Islam entre préservation et innovation, Sirhindi est devenu le porte-parole d'une bataille acharnée pour la redécouverte de la pureté originelle de l'Islam face à la tentative impériale de construire une forme religieuse syncrétique, tentative visant à aplanir les divergences au sein de l'Empire. Cet épisode mérite une brève enquête.

L'histoire de l'empereur moghol Akbar est assez complexe. Bien qu'il ait réussi à satisfaire ses ambitions de conquête en plaçant l'Hindoustan sous son pouvoir, Akbar a toujours montré une tendance à la mélancolie (peut-être causée par de fréquentes crises d'épilepsie) qui transparaît dans l'inscription qu'il a dictée pour le majestueux portail de la Jama Masjid (la mosquée du vendredi, qu'il avait fait construire à Fatehpur Sikri, après la conquête du Gujarat) : " Le monde est un pont: passez-le, mais ne construisez pas de maison dessus [...] Le monde ne dure qu'une heure : passez-la dans la prière "[4].

Toujours à Fatehpur Sikri, en 1575, l'empereur a voulu établir un centre d'investigation philosophico-religieux, connu sous le nom d'Ibadhat Khana, dont l'objectif initial était de surmonter les différences entre les divers courants de l'Islam pour redonner à la religion sa force et sa pureté originelles. Cependant, surtout après l'ouverture des portes du centre par Akbar et la participation subséquente au débat de représentants d'autres religions (juifs, chrétiens, zoroastriens, hindous, etc.), son sentiment d'appartenance à l'Islam (bien qu'il n'ait jamais été complètement répudié) s'est lentement estompé. En particulier, 1578 est l'année du tournant (peut-être dû à une crise d'épilepsie plus lourde que d'habitude au cours d'une expédition de chasse): il passe du statut de souverain musulman orthodoxe à celui de réformateur radical.

Comme on retrouve dans la pensée d'Akbar l'idée que le rituel exécuté mécaniquement et sans conscience intérieure rend le culte de Dieu inutile, le roi était extrêmement intéressé et fasciné par le soufisme. Cet intérêt l'a cependant amené à convoquer non seulement des maîtres du courant ésotérique de l'Islam comme Shaikh Tajuddin (qui a identifié la doctrine soufie de l'unité de l'être avec le monisme de la métaphysique hindoue), mais aussi des samanas (ascètes bouddhistes et jaïns), des yogis, des brahmanes et des savants zoroastriens. En effet, à partir de 1580, sous l'influence du zoroastrien Dastur Mahyragi Rana, Akbar adopte également en public les rites de l'ancienne religion iranienne. Mais le conflit avec les autorités orthodoxes de l'islam a commencé dès 1579, lorsque, à l'occasion de l'anniversaire de la naissance du prophète Mahomet (qui tombait cette année-là le 26 juin), il a lu pour la première fois et conclu la khutba (le sermon du vendredi) dans le Jama Masjid en prononçant les mots "Allahu Akbar".

Cette expression est assez célèbre et courante en Islam. Elle suscita cependant l'ire des oulémas orthodoxes qui l'interprétèrent non pas avec le sens traditionnel "Dieu est plus grand", mais avec la volonté du souverain d'affirmer sa propre divinité, puisqu'elle pouvait aussi se prêter à un "Akbar est Dieu" plus que blasphématoire.

Quelques mois après l'événement, Akbar a obtenu de certains érudits religieux de la cour un document le déclarant Sultan-i adil (souverain vertueux). Ce document, fondé sur le dicton coranique "obéissez à Dieu, obéissez au Prophète et à ceux d'entre vous qui détiennent l'autorité", lui permettait, entre autres, d'agir en tant qu'arbitre dans les affaires religieuses et d'émettre un décret contraignant (pour autant qu'il soit conforme au Coran) pour le bien de l'empire en cas de conflit d'opinions entre les savants.

Akbar s'est servi de ce stratagème pour promulguer en 1582 sa propre religion syncrétique, le Din Ilahi, en opposition ouverte à l'orthodoxie islamique, qu'il considérait, comme le rapporte l'historien Firishta précité, comme un obstacle à ses idées. Cette nouvelle religion se présentait comme un credo syncrétique, dont le but était de trouver un point de convergence entre toutes les croyances, afin que tous puissent l'approuver tout en restant fidèles à leurs propres croyances. Il s'agissait d'une religion "régicentrique", qui, à certains égards, peut rappeler l'expérience monothéiste solaire du pharaon égyptien Akhénaton et dont les connotations étaient principalement socio-politiques. L'idée fondamentale défendue par Akbar était que la vénération du souverain faisait partie de la même vénération de Dieu ; et que la vénération de Dieu, pour le souverain, n'était rien d'autre que la pratique d'une administration conforme à la justice.

Outre le caractère assez confus de la doctrine, l'expérience d'Akbar échoua non seulement en raison du caractère élitiste (pseudo-initiatique) que le souverain voulait donner à sa "religion", mais aussi en raison de l'hostilité des érudits musulmans orthodoxes et de la réticence des communautés majoritaires respectives de l'Empire à s'amalgamer entre elles. En fait, malgré les efforts d'Akbar, les "deux nations" du sous-continent avaient déjà été largement consolidées.

Un autre précurseur de l'idée des "deux nations" est Sayyed Ahmad Barelvi (1786-1832), qui a tenté de convaincre les Pachtounes d'abandonner définitivement leur droit coutumier particulier et de construire un "État islamique" par le biais du djihad offensif contre le royaume sikh de Ranjit Singh. Avant lui, un autre représentant musulman qui mérite qu'on s'y attarde est sans doute Shah Waliullah (1703-1762), l'inspirateur du mouvement déobandi qui, au cours du XVIIIe siècle, a invité le fondateur de l'empire Durrani dans l'actuel Afghanistan, Ahmad Shah Abdali (1722-1772) [5], à intervenir dans le sous-continent pour défendre les musulmans contre les persécutions hindoues.

Ahmad Shah Abdali.

Cependant, celui à qui l'on attribue généralement la première formulation de l'idée de deux nations distinctes dans le sous-continent indien est Sayyed Ahmad Khan : le fondateur de l'Anglo-Oriental Muhammadan College d'Aligarh, par lequel il proposait d'éduquer une nouvelle classe dirigeante musulmane "occidentalisée" (il n'est pas surprenant que sa pensée ait été prise comme référence idéologique sous le régime désastreux de Pervez Musharraf). Son nom mérite toutefois une attention particulière car c'est à partir de ses réflexions que la théorie des "deux nations" a pris un caractère proprement moderne et structuré, également en réponse anticipée au développement ultérieur des idées sur le "nationalisme composite", dont l'origine est principalement due à la pensée de Bipin Chandra Pal (1858-1932) [6] dans la première décennie du XXe siècle. Ainsi, Ahmad Khan a déclaré dans un discours prononcé en 1883 à Patna, dans l'Inde actuelle, "Mes amis, il existe en Inde deux nations importantes qui se distinguent par les noms d'hindous et de musulmans. Tout comme le corps humain possède certains organes principaux, de la même manière, ces deux nations représentent les deux principaux membres de l'Inde" [7].

En prenant note de la paternité de l'idée, il convient de noter que l'historiographie pakistanaise a mené une enquête approfondie pour savoir qui a été la première personne à formuler de manière accomplie au 20e siècle le projet de construire deux nations distinctes en Inde britannique. L'historien Sheikh Muhammad Ikram, par exemple, rapporte que la déclaration suivante du juge Abdur Rahim au congrès de la Ligue musulmane à Aligarh en 1925 a suscité une certaine consternation : "Les hindous et les musulmans ne sont pas deux sectes différentes comme les catholiques et les protestants en Angleterre, mais forment deux communautés distinctes de personnes, et se considèrent ainsi. Leurs attitudes respectives à l'égard de la vie, leurs cultures distinctes, leurs habitudes sociales et leurs civilisations, leur histoire et leurs traditions, non moins que la religion, les divisent si complètement que le fait d'avoir vécu pendant environ mille ans dans le même pays n'a rien fait pour les fusionner en une seule nation [...] Chacun d'entre nous, Indiens musulmans, voyageant par exemple en Afghanistan, en Perse ou en Asie centrale, chez les musulmans de Chine, chez les Arabes ou les Turcs, se sentiront toujours chez eux, retrouvant des coutumes auxquelles ils sont déjà habitués. Au contraire, en Inde, nous nous trouvons complètement étrangers à toutes les questions sociales dès que nous traversons la rue et entrons dans la partie de la ville où vivent nos compatriotes hindous."[8]

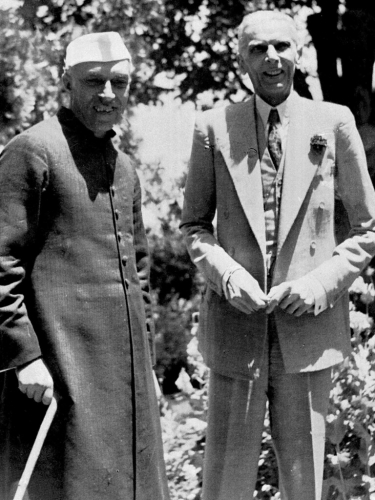

Nehru et Jinnah.

Cependant, l'exposé philosophique et politique de la théorie des "deux nations" est généralement attribué à Muhammad Iqbal et à Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Le premier, en effet, dans le discours déjà cité d'Allahabad, a promu l'idée d'une forme d'"autonomie au sein de l'Empire britannique" (ou sans lui) pour les musulmans du sous-continent. Selon le poète et penseur (qui a également reconnu comment les Britanniques exploitaient les divisions entre hindous et musulmans pour des raisons géopolitiques) [9], la création d'un "État islamique" était dans le meilleur intérêt de l'Inde et de l'islam lui-même. En fait, elle aurait représenté une force fondamentale pour la sécurité, la paix et l'équilibre des pouvoirs au sein d'un sous-continent dont l'unité devait être reconstruite non pas dans la négation des différences, mais dans l'harmonie et la coopération mutuelles [10]. Cette position est également résumée dans la déclaration faite par Iqbal en réponse aux accusations de Jawaharlal Nehru après l'échec de la série de tables rondes organisées à Londres au début des années 1930 sur les réformes à adopter en Inde. En voici un extrait : "En conclusion, je veux poser une question directe au Pandit Jawaharlal : comment le problème indien peut-il être résolu si la communauté majoritaire ne veut ni accorder la protection minimale nécessaire à la protection d'une minorité de 80 millions de personnes, ni accepter l'existence d'un tiers, mais continuer à parler d'un nationalisme qui ne fonctionne qu'à son propre avantage ? Cette position ne peut admettre que deux alternatives. Soit la majorité indienne doit accepter pour elle-même le rôle d'agent pérenne de l'impérialisme britannique en Orient, soit le pays doit être redistribué sur la base des affinités historiques, religieuses et culturelles. "[11]

Une vague accusation d'être un agent de l'impérialisme britannique, pour être juste, a également été portée contre Muhammad Ali Jinnah, précisément en raison de son soutien à la cause de la partition. En 1943, cette accusation a conduit un activiste supposé être associé au mouvement Khaksar (à fort caractère social-révolutionnaire)[12] à attenter à la vie du leader politique musulman. Jinnah, cependant, continua sans se décourager à soutenir l'idée que, au contraire, c'était la fausse représentation d'une Inde unie qui maintenait les Britanniques sur le sol du sous-continent.

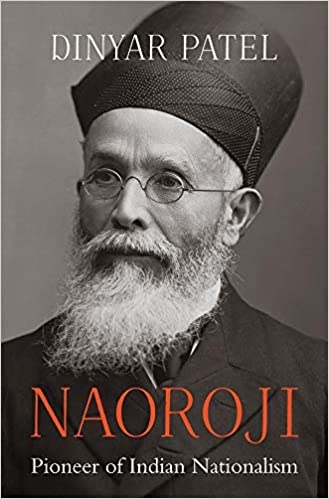

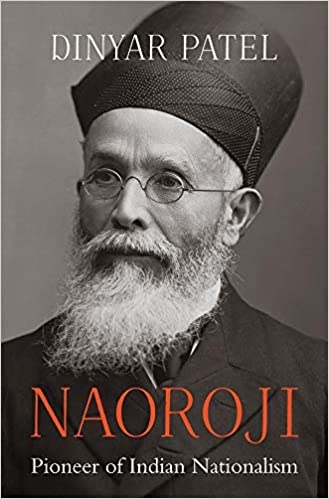

Comme nous l'avons déjà mentionné, le Qaid-e Azam a embrassé la cause des "deux nations" sur le tard. Brillant avocat passé à la politique, Jinnah termine ses études à Londres, où il devient membre de l'Honorable Society of Lincoln's Inn (l'une des plus prestigieuses guildes professionnelles de juges et d'avocats au monde) sur l'entrée principale de laquelle le prophète Mahomet figure parmi les grands hommes d'État et législateurs de l'humanité. À Londres, Jinnah devient l'assistant du politicien libéral (et franc-maçon) Dadabhai Naoroji [13], le premier Asiatique (de confession zoroastrienne) à devenir membre du Parlement britannique ; de lui, Jinnah hérite de la dévotion presque obstinée aux méthodes constitutionnelles et de l'idée d'émancipation (surtout des jeunes) par l'éducation. Cette insistance sur les méthodes constitutionnelles (même au moment où il s'est rendu compte qu'il n'y avait pas d'autre solution que la partition) était surtout liée au fait que, comme cela s'est effectivement produit, une fin abrupte de la domination britannique conduirait inévitablement à la violence sectaire.

Si, comme il a été dit plus haut, Jinnah a opté pour la théorie des "deux nations" dès 1937 et suite aux tensions croissantes entre le Congrès et la Ligue musulmane, il est tout aussi vrai que son idée n'a été ouvertement présentée que dans le discours qu'il a prononcé à Lahore le 22 mars 1940 :

"Il est extrêmement difficile d'apprécier le fait que nos amis hindous ne peuvent pas comprendre la nature même de l'islam et de l'hindouisme. Ce ne sont pas des religions au sens concret du terme, en fait, ce sont des ordres sociaux différents et distincts, et c'est un rêve de penser que les hindous et les musulmans peuvent développer un sens commun de la nationalité, et cette incompréhension de la nation indienne pose des problèmes et conduira l'Inde elle-même à la faillite si nous ne reconstruisons pas cette notion à temps. Les hindous et les musulmans appartiennent à deux philosophies religieuses différentes, à des littératures différentes et à des coutumes sociales différentes. Ils ne se marient pas entre eux et appartiennent à deux civilisations différentes qui reposent sur des concepts et des idées contradictoires. Leur idée de la vie et sur la vie est différente. Il est tout à fait clair que les hindous et les musulmans tirent leur inspiration de sources historiques différentes. Ils ont des épopées différentes, des héros différents et des événements différents. Souvent, le héros de l'un est l'ennemi de l'autre et leurs victoires et défaites se chevauchent. Réunir de force dans un même État ces deux nations, l'une majoritaire et l'autre minoritaire, alimentera le mécontentement et conduira à la destruction définitive de toute constitution gouvernementale conçue pour un tel État" [14]. Il s'agissait d'une déclaration similaire faite un an plus tôt.

Une déclaration similaire a également été faite quelques années plus tôt par Choudhry Rahmat Ali (photo) (exactement en 1933 et à la fin des tables rondes de Londres) dans un pamphlet qui a acquis une certaine notoriété sous le titre de « Déclaration du Pakistan ». Rahmat Ali écrit : "Nos religions et nos cultures, nos histoires et nos traditions, nos codes sociaux et nos systèmes économiques, nos lois sur l'héritage, la succession et le mariage sont fondamentalement différents de ceux des personnes vivant dans le reste de l'Inde. Les idées qui poussent notre peuple à faire les plus grands sacrifices sont essentiellement différentes de celles qui inspirent les hindous à faire de même. Ces différences ne se limitent pas aux principes de base. Ils s'étendent jusqu'aux moindres détails de nos vies. Nous ne dînons pas ensemble. On ne se marie pas entre nous. Nos coutumes nationales et nos calendriers sont aussi différents que notre nourriture et nos vêtements"[15]. Nous ne sommes pas les mêmes.

Une déclaration similaire a également été faite quelques années plus tôt par Choudhry Rahmat Ali (photo) (exactement en 1933 et à la fin des tables rondes de Londres) dans un pamphlet qui a acquis une certaine notoriété sous le titre de « Déclaration du Pakistan ». Rahmat Ali écrit : "Nos religions et nos cultures, nos histoires et nos traditions, nos codes sociaux et nos systèmes économiques, nos lois sur l'héritage, la succession et le mariage sont fondamentalement différents de ceux des personnes vivant dans le reste de l'Inde. Les idées qui poussent notre peuple à faire les plus grands sacrifices sont essentiellement différentes de celles qui inspirent les hindous à faire de même. Ces différences ne se limitent pas aux principes de base. Ils s'étendent jusqu'aux moindres détails de nos vies. Nous ne dînons pas ensemble. On ne se marie pas entre nous. Nos coutumes nationales et nos calendriers sont aussi différents que notre nourriture et nos vêtements"[15]. Nous ne sommes pas les mêmes.

Lors d'une rencontre en 1934 entre Jinnah et Rahmat Ali lui-même, le premier suggère au second de faire preuve d'une certaine prudence. Toutefois, le zèle missionnaire conduit le fondateur du Mouvement national pakistanais à se rapprocher des thèses du national-socialisme et à entrer en opposition avec Jinnah lui-même ; cela se produit lorsque ce dernier accepte une solution territoriale qui réduit l'espace géographique du futur Pakistan par rapport au projet idéal de Rahmat Ali, fondé sur l'idée de libérer les musulmans du sous-continent de la "barbarie de l'indianisme"[16].

La théorie des "deux nations" trouve également un soutien dans les milieux purement religieux. La vision de Jinnah, comme on le sait, était celle d'un État inspiré par les principes de l'Islam, bien que lui-même ait toujours refusé toute caractérisation religieuse de son rôle. À ceux qui voulaient lui donner le titre de "Maulana", par exemple, il s'est toujours fermement opposé, déclarant être un politicien et non un homme de religion [17]. En tout cas, c’est ce qu’il a déclaré lors d'une interview avec une radio nord-américaine :

"Le Pakistan est le premier État islamique [...] La Constitution du Pakistan n'a pas encore été discutée par l'Assemblée constituante. Je ne sais pas quelle sera la forme finale de cette Constitution, mais je suis sûr qu'il s'agira d'un modèle démocratique capable d'intégrer les principes essentiels de l'Islam. Celles-ci sont toujours aussi applicables aujourd'hui qu'elles l'étaient il y a 1300 ans. L'Islam et l'idéalisme nous ont appris la démocratie. L'Islam nous a enseigné l'égalité entre les hommes et la justice"[18]. L'appel à l'égalité et à la justice est important.

La référence à la justice et à l'égalité entre les hommes apparaît également dans certaines déclarations de nature plus purement économique. Par exemple :

"Le système économique de l'Occident a créé des problèmes insolubles pour l'humanité [...] Il n'a pas réussi à créer la justice entre les hommes et à éliminer les diatribes dans l'arène internationale [...] L'adoption d'une théorie économique occidentale ne nous aidera pas à atteindre l'objectif de créer un peuple autosuffisant et heureux [...] Nous devons construire notre propre destin à notre manière et présenter au monde un système économique basé sur le concept islamique d'égalité" [19].

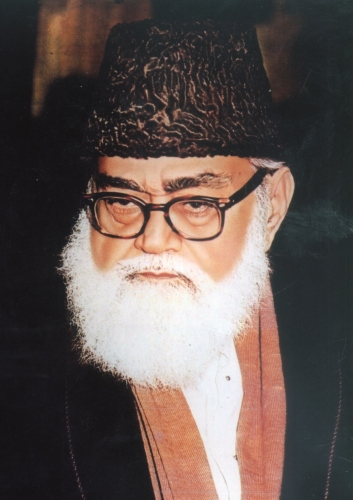

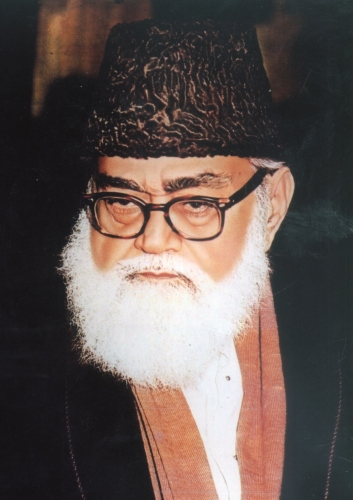

Maulana Abul A'la Maududi.

Sur la base de ces déclarations, de nombreux représentants du soufisme barelvi se sont prononcés en faveur de la partition. Au contraire, Maulana Abul A'la Maududi soutenait que l'idée de partition et de fermeture de l'islam au sein d'un État moderne était fondamentalement non islamique (contraire au concept traditionnel d'Umma). Cependant, sa Jama'at-e-Islami, malgré une relation difficile avec les institutions pakistanaises après la partition, a trouvé dans le militarisme islamiste de Zia ul-Haq, l'allié idéal pour développer un projet d'islamisation forcée par le haut, également contraire aux principes coraniques.

Parmi les groupes qui ont soutenu le plus activement le processus de séparation en deux États figure sans conteste la Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at. Il s'agissait d'un mouvement d'inspiration messianique, dont le premier leader (Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, 1835-1908) s'était déclaré le Mahdi attendu, invoquant le retour à la pureté originelle de l'Islam. Pendant la première guerre indo-pakistanaise de 1947-48, ce mouvement a créé l'organisation paramilitaire connue sous le nom de Furqan Forces, qui a combattu au Cachemire [20].

Bien sûr, même au sein de la sphère hindoue, certains penseurs et intellectuels ont adopté ou se sont opposés à la théorie des "deux nations". Il suffit de mentionner Indira Ghandi qui, lorsque le Pakistan oriental est devenu indépendant en tant que Bangladesh après la guerre de 1971 [21], a déclaré l'échec de la théorie des "deux nations". Toutefois, comme l'analyste pakistanais et ancien militaire Masud Ahmad Khan a eu l'occasion de le souligner, le Bangladesh n'est pas du tout un État laïque, c'est un État musulman. Et l'affirmation toute récente du nationalisme exclusiviste hindou du Bharatiya Janata Party, inspiré par la pensée de Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (1883-1966), est la démonstration la plus claire que la théorie de deux nations distinctes dans le sous-continent indien est plus vivante que jamais[22].

NOTES

[1] Le Vande Mataram raconte l’histoire d’une société secrète hindoue qui, au 18ème siècle, a cherché à renverser le gouvernement islamique au Bengale.

[2] Dynastie perse, auparavant de religion bouddhiste, qui s’est convertie à l’islam et qui a battu la dynastie turque persisée de Ghaznavides en 1186, tout en conquérant leur capitale Lahore, aujourd’hui sur territoire pakistanais.

[3] A. Eraly, Il trono dei Moghul. La saga dei grandi imperatori dell’India, Il Saggiatore (2000), p. 43.

[4] Il trono dei Moghul, ivi cit., p. 188.

[5] Descendant des tribus pachtounes Sadozai et Alokozai, Ahmad Shah Abdali est le héros national de l’Afghanistan et est considéré comme le « Père moderne de la Nation ».

[6] Un des architectes majeurs du mouvement Swadeshi (en même temps que Sri Aurobindo) qui s’est opposé à la partition du Bengale décidée par le gouvernement britannique d’Inde en 1903. Chandra Pal était également membre du triumvirat nationaliste Lal-Bal-Pal (les deux autres membres étaient Lala Laipat Raj et Bal Ganghadar Tilak), triumvirat qui dirigea la lutte anticoloniale indienne dans les premières années du 20ème siècle.

[7] R. Guha, Makers of modern India, Harvard University Press (2011), p. 65.

[8] S. M. Khan, Indian muslims and partition of India, Atlantic Publisher & Dist (1995), p. 308.

[9] L’historien David Hardiman partage également cette idée et cette théorie, selon lesquelles aucune hostilité particulière n’opposait les musulmans aux hindous au moment où les Britanniques sont arrivés dans le sous-continent indien. Ce sont donc, d’après cette théorie, les Britannques qui ont articulé la très célèbre pratique impérialiste du divide et impera afin de maintenir leur contrôle colonial sur cette région du monde. Voir D. Hardiman, Gandhi in his time and ours: the global legacy of his idea, Columbia University Press (2003), p. 22.

[10] Voir I. S. Sevea, The political philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal. Islam and nationalism in late colonial India, Cambridge University Press (2012), p. 14.

[11] Dans Iqbal and the Pakistan Movement, www.allamaiqbal.com.

[12] Ce mouvement, de caractère militariste rigide, a été fondé en 1931 par Allama Mashriqi (mathématicien et théoricien politique) qui se proposait de libérer l’Inde des Britanniques par le biais de la lutte armée et de la construction d’un Etat hindou/musulman.

[13] Naoroji est aussi considéré comme le mentor de l’activiste politique et intellectuel Bal Ganghadar Tilak(déjà cité comme membre du triumvirat Lal-Bal-Pal et auteur d’un ouvrage célèbre La dimora artica nei Veda) et d’un homme politique indien très important, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, fondeteur de la « Société des Serviteurs de l’Inde ».

[14] Jinnah. Creator of Pakistan, Oxford University Press (1953), p. 140.

[15] T. Kamran, Choudhry Rahmat Ali and his political imagination: Pak Plan and the continent of Dinia, contenuto in A. Usmani – M. Eaton Robb (a cura di), Muslims against the Muslim League, Cambridge University Press (2017), p. 92.

[16] K. K. Aziz, Rahmat Ali: a biography, Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden (1987), p. 123. Rahmat Ali forgea le terme d’ « indianisme » pour définir une force qui avait dominé tout le sous-continent et s’était opposé aux efforts de ses peuples pour améliorer leur propre condition. Cette force était donc perçue comme « destructrice », comme quelque chose qui avait conduit à la servitude d’au moins la moitié de la population du sous-continent. Pour ce motif, Rahmat Ali s’opposait avec virulence à la création d’une « Fédération Indienne » sous l’égide du Congrès.

[17] Hector Bolitho raconte, à ce propos, que Jinnah cultivait une admiration particulière pour l’expérience nationaliste, laïque et réformiste de Mustafa Kemal en Turquie, dont il critiquait toutefois les tendances libertines. Dans le même contexte, il est curieux de noter que Muhammad Iqbal n’appréciait pas du tout le Père de la République turque.

[18] Dans : M. A. Z. Qureshi, Decolonization and Nation-Building in Pakistan. Islam or Secularism?, IDSS Research Paper 2011.

[19] Jinnah. Creator of Pakistan, ivi cit., p. 177.

[20] S. Ross, Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama’at. History, belief, practice, Columbia University Press (2003), p. 204.

[21] L’un des préoccupations principales qui tourmentaient Jinnah au moment de la partition était l’absence d’une communication directe, soit d’un corridor terrestre, entre les deux parties du Pakistan.

[22] Voir M. S. Khan, Jinnah’s two Nation theory, www.nation.com.pk.

Daniele Perra

Depuis 2017, Daniele Perra collabore activement avec "Eurasia. Journal of Geopolitical Studies" et le site informatique correspondant. Ses analyses portent principalement sur les relations entre la géopolitique, la philosophie et l'histoire des religions. Diplômé en sciences politiques et en relations internationales, il a obtenu en 2015 un master en études moyen-orientales de l'ASERI - Alta Scuola di Economia e Relazioni Internazionali de l'Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore de Milan. En 2018, son essai Sulla necessità dell'impero come entità geopolitica unitaria per l'Eurasia a été inclus dans le vol. VI des "Quaderni della Sapienza" publiés par Irfan Edizioni. Il collabore assidûment avec plusieurs sites Internet italiens et étrangers et a accordé plusieurs interviews à la radio iranienne Radio Irib. Il est l'auteur du livre Être et Révolution. Ontologie heideggérienne et politique de la libération, préface de C. Mutti (NovaEuropa 2019).

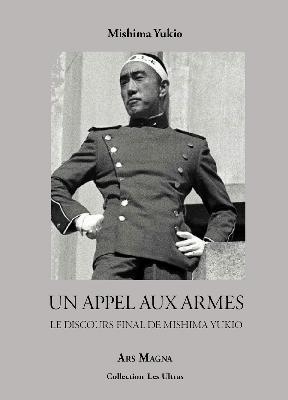

Par-delà le rôle moteur de l’armée, Mishima Yukio défend le rétablissement de la pleine souveraineté de Tokyo. Or, il sait que son pays sorti des ruines de l’après-guerre est une colonie de l’Occident anglo-saxon. « Le soi-disant contrôle par le pouvoir civil des militaires anglais et américains est uniquement un contrôle financier (p. 25). » Il dénonce que l’île méridionale d’Okinawa soit encore sous la tutelle de Washington. Il ignore que les États-Unis la rétrocéderont au Japon en 1972. Il s’offusque que le Japon signe le traité de non-prolifération nucléaire et renonce ainsi à la détention d’une force de frappe atomique. Clairvoyant, il prévient que la soumission du Jieitai aux vainqueurs de 1945 en fera, « comme les gauchistes l’ont remarqué, une force mercenaire de l’Amérique pour toujours (p. 27) ».

Par-delà le rôle moteur de l’armée, Mishima Yukio défend le rétablissement de la pleine souveraineté de Tokyo. Or, il sait que son pays sorti des ruines de l’après-guerre est une colonie de l’Occident anglo-saxon. « Le soi-disant contrôle par le pouvoir civil des militaires anglais et américains est uniquement un contrôle financier (p. 25). » Il dénonce que l’île méridionale d’Okinawa soit encore sous la tutelle de Washington. Il ignore que les États-Unis la rétrocéderont au Japon en 1972. Il s’offusque que le Japon signe le traité de non-prolifération nucléaire et renonce ainsi à la détention d’une force de frappe atomique. Clairvoyant, il prévient que la soumission du Jieitai aux vainqueurs de 1945 en fera, « comme les gauchistes l’ont remarqué, une force mercenaire de l’Amérique pour toujours (p. 27) ».

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Une déclaration similaire a également été faite quelques années plus tôt par Choudhry Rahmat Ali (photo) (exactement en 1933 et à la fin des tables rondes de Londres) dans un pamphlet qui a acquis une certaine notoriété sous le titre de « Déclaration du Pakistan ». Rahmat Ali écrit : "Nos religions et nos cultures, nos histoires et nos traditions, nos codes sociaux et nos systèmes économiques, nos lois sur l'héritage, la succession et le mariage sont fondamentalement différents de ceux des personnes vivant dans le reste de l'Inde. Les idées qui poussent notre peuple à faire les plus grands sacrifices sont essentiellement différentes de celles qui inspirent les hindous à faire de même. Ces différences ne se limitent pas aux principes de base. Ils s'étendent jusqu'aux moindres détails de nos vies. Nous ne dînons pas ensemble. On ne se marie pas entre nous. Nos coutumes nationales et nos calendriers sont aussi différents que notre nourriture et nos vêtements"[15]. Nous ne sommes pas les mêmes.

Une déclaration similaire a également été faite quelques années plus tôt par Choudhry Rahmat Ali (photo) (exactement en 1933 et à la fin des tables rondes de Londres) dans un pamphlet qui a acquis une certaine notoriété sous le titre de « Déclaration du Pakistan ». Rahmat Ali écrit : "Nos religions et nos cultures, nos histoires et nos traditions, nos codes sociaux et nos systèmes économiques, nos lois sur l'héritage, la succession et le mariage sont fondamentalement différents de ceux des personnes vivant dans le reste de l'Inde. Les idées qui poussent notre peuple à faire les plus grands sacrifices sont essentiellement différentes de celles qui inspirent les hindous à faire de même. Ces différences ne se limitent pas aux principes de base. Ils s'étendent jusqu'aux moindres détails de nos vies. Nous ne dînons pas ensemble. On ne se marie pas entre nous. Nos coutumes nationales et nos calendriers sont aussi différents que notre nourriture et nos vêtements"[15]. Nous ne sommes pas les mêmes.

Le couple inégal ralentit le pas. Il était seul devant la forêt aux portes fermées pour eux. Je dis "inégal" car l'un d'entre eux, le plus jeune, savait des choses que le plus vieux ignorait totalement. La preuve de cet aveuglement, de ce rejet obstiné de l'invisible, ce sont ces appareils de mesure qu'il portait en permanence sur lui et qui lui donnait une allure de scaphandrier. À la campagne, ces appareils miniaturisés, micro-ordinateur, caméra avec pluviomètre intégré, entre autres prothèses, étaient le pendant de ces panneaux de circulation et autres passages piétons du monde urbain sans lesquels il ne pouvait vivre.

Le couple inégal ralentit le pas. Il était seul devant la forêt aux portes fermées pour eux. Je dis "inégal" car l'un d'entre eux, le plus jeune, savait des choses que le plus vieux ignorait totalement. La preuve de cet aveuglement, de ce rejet obstiné de l'invisible, ce sont ces appareils de mesure qu'il portait en permanence sur lui et qui lui donnait une allure de scaphandrier. À la campagne, ces appareils miniaturisés, micro-ordinateur, caméra avec pluviomètre intégré, entre autres prothèses, étaient le pendant de ces panneaux de circulation et autres passages piétons du monde urbain sans lesquels il ne pouvait vivre.

Autant ce recueil de Max Jacob est « légitimement le plus connu », autant Jean Reverzy et son roman Le Passage sont imméritoirement écartés par la postérité littéraire. Il s’agit pourtant d’un auteur qui partage avec Céline son métier initial de médecin des pauvres et son évolution vers un pessimisme décrivant « le lent travail de la vie, cet effritement invisible et ininterrompu ». Un rapprochement est aussi esquissé entre Le Passage de Reverzy et L’Étranger de Camus : « la mer, les hommes simples, une réflexion sur la vie, cet étrange cadeau empoisonné par la mort » et un personnage final d’aumônier « dépeint comme un intrus ».

Autant ce recueil de Max Jacob est « légitimement le plus connu », autant Jean Reverzy et son roman Le Passage sont imméritoirement écartés par la postérité littéraire. Il s’agit pourtant d’un auteur qui partage avec Céline son métier initial de médecin des pauvres et son évolution vers un pessimisme décrivant « le lent travail de la vie, cet effritement invisible et ininterrompu ». Un rapprochement est aussi esquissé entre Le Passage de Reverzy et L’Étranger de Camus : « la mer, les hommes simples, une réflexion sur la vie, cet étrange cadeau empoisonné par la mort » et un personnage final d’aumônier « dépeint comme un intrus ».  C’est encore Henri Cambon qui ravive le souvenir de Jean Rogissart (1894 – 1961). Certes, l’auteur de la saga des Mamert a fait encore récemment l’objet d’une étude universitaire (à Dijon, en 2014). Mais cette fresque familiale reste relativement méconnue alors qu’elle s’inscrit dans un majestueux courant littéraire français dont Georges Duhamel et Roger Martin du Gard sont d’illustres représentants.

C’est encore Henri Cambon qui ravive le souvenir de Jean Rogissart (1894 – 1961). Certes, l’auteur de la saga des Mamert a fait encore récemment l’objet d’une étude universitaire (à Dijon, en 2014). Mais cette fresque familiale reste relativement méconnue alors qu’elle s’inscrit dans un majestueux courant littéraire français dont Georges Duhamel et Roger Martin du Gard sont d’illustres représentants. On attribue à Jean-Baptiste Clément la création du Temps des Cerises, célèbre chanson qui aurait été inspirée par la Commune de Paris. Ce titre est aussi celui du deuxième volume du cycle romanesque de Jean Rogissart. Jean-Baptiste Clément est de passage dans la contrée mosane et y répand sa conception d’un « socialisme pur » grâce auquel « l’homme rompt ses chaînes millénaires et peut enfin croire en Dieu ». remarquons ici l’intéressant renversement de l’idée marxiste de la religion comme « opium du peuple », dont il faut se débarrasser pour mener à son terme le processus d’émancipation économique et sociale. Pour Rogissart, au contraire, il faut d’abord vaincre l’esclavage ouvrier qui pèse sur l’humanité comme une sorte de fatalité originelle, un obscur destin dont la volonté militante doit s’affranchir pour pouvoir accéder à la lumière de la Providence divine. Destin – Volonté – Providence : c’est l’une des « grandes triades » analysées par René Guénon.

On attribue à Jean-Baptiste Clément la création du Temps des Cerises, célèbre chanson qui aurait été inspirée par la Commune de Paris. Ce titre est aussi celui du deuxième volume du cycle romanesque de Jean Rogissart. Jean-Baptiste Clément est de passage dans la contrée mosane et y répand sa conception d’un « socialisme pur » grâce auquel « l’homme rompt ses chaînes millénaires et peut enfin croire en Dieu ». remarquons ici l’intéressant renversement de l’idée marxiste de la religion comme « opium du peuple », dont il faut se débarrasser pour mener à son terme le processus d’émancipation économique et sociale. Pour Rogissart, au contraire, il faut d’abord vaincre l’esclavage ouvrier qui pèse sur l’humanité comme une sorte de fatalité originelle, un obscur destin dont la volonté militante doit s’affranchir pour pouvoir accéder à la lumière de la Providence divine. Destin – Volonté – Providence : c’est l’une des « grandes triades » analysées par René Guénon.

Avec Silvio Maresca nous réalisons tous deux, pour la télévision, un programme appelé "Disenso", qui porte sur la métapolitique et la philosophie, et cela depuis 2012 ; ce programme est accessible sur youtube. Et après avoir interviewé presque tous ceux qui essaient de faire de la philosophie en Argentine (s'il en reste, que nous aurions oubliés, nous les invitons à participer), nous avons commencé à traiter divers sujets philosophiques et ce commentaire en fait partie.

Avec Silvio Maresca nous réalisons tous deux, pour la télévision, un programme appelé "Disenso", qui porte sur la métapolitique et la philosophie, et cela depuis 2012 ; ce programme est accessible sur youtube. Et après avoir interviewé presque tous ceux qui essaient de faire de la philosophie en Argentine (s'il en reste, que nous aurions oubliés, nous les invitons à participer), nous avons commencé à traiter divers sujets philosophiques et ce commentaire en fait partie. Rien n'est plus éloigné de l'opinion de Heidegger, qui développe, à partir de là, la thèse centrale de la Lettre, selon laquelle la culture humaniste, en raison de sa rationalité moderne, celle de la raison calculatrice, ne pouvait nous apporter que la Seconde Guerre mondiale, avec sa civilisation de la technique à laquelle ont collaboré aussi bien le gigantisme nord-américain que le marxisme soviétique.

Rien n'est plus éloigné de l'opinion de Heidegger, qui développe, à partir de là, la thèse centrale de la Lettre, selon laquelle la culture humaniste, en raison de sa rationalité moderne, celle de la raison calculatrice, ne pouvait nous apporter que la Seconde Guerre mondiale, avec sa civilisation de la technique à laquelle ont collaboré aussi bien le gigantisme nord-américain que le marxisme soviétique. A quoi Heidegger répond brièvement en disant que l'éthique prédominante de la modernité a été l'éthique des normes, du devoir-être, qui se fonde sur l'éthique kantienne et la projection politique pratique de la morale bourgeoise, mais que tant l'éthique que l'ontologie sont des disciplines philosophiques établies depuis Platon, que les penseurs avant lui ne connaissaient pas en tant que telles.

A quoi Heidegger répond brièvement en disant que l'éthique prédominante de la modernité a été l'éthique des normes, du devoir-être, qui se fonde sur l'éthique kantienne et la projection politique pratique de la morale bourgeoise, mais que tant l'éthique que l'ontologie sont des disciplines philosophiques établies depuis Platon, que les penseurs avant lui ne connaissaient pas en tant que telles.

La praxis marxiste est un dépassement de la contemplation (theorein) de l'Être social. Il serait préférable de dire qu'il s'agit d'une super-contemplation. La praxis marxiste, et non une quelconque "science du matérialisme historique", consiste à affronter le passé. Le prendre en charge, le questionner, se dire ce qu'il y a de lui en moi, et ce que je peux faire, ce que nous pouvons faire pour éviter que ce passé ne devienne despotique. Comme le dit mon ami Diego Fusaro, bon élève de Gramsci et de Preve à la fois, il s'agit de "défataliser l'existant". Le passé non affronté, le passé assumé sans autre forme de procès, comme une roue inexorable à laquelle nous sommes liés et au type de laquelle nous sommes condamnés à participer, est un passé qui, en tant que tel, n'est pas modifiable. Saint Thomas a déjà dit dans la Summa Theologiae que ni Dieu ni le passé ne peuvent le changer (ce serait une autre chose de dire que Dieu aurait pu faire en sorte que le passé soit différent). Il n'existe aucun pouvoir, aussi divin soit-il, qui puisse transmuter le passé. Mais il existe un pouvoir, celui de la raison et de la compréhension humaines, qui est capable de "défataliser" le passé. Et comment le passé peut-il être défloré ? En rendant aux masses populaires leur capacité de résistance à l'Horreur. En rendant à la conscience collective de la société son sentiment d'être des sujets dotés d'un pouvoir pratique.

La praxis marxiste est un dépassement de la contemplation (theorein) de l'Être social. Il serait préférable de dire qu'il s'agit d'une super-contemplation. La praxis marxiste, et non une quelconque "science du matérialisme historique", consiste à affronter le passé. Le prendre en charge, le questionner, se dire ce qu'il y a de lui en moi, et ce que je peux faire, ce que nous pouvons faire pour éviter que ce passé ne devienne despotique. Comme le dit mon ami Diego Fusaro, bon élève de Gramsci et de Preve à la fois, il s'agit de "défataliser l'existant". Le passé non affronté, le passé assumé sans autre forme de procès, comme une roue inexorable à laquelle nous sommes liés et au type de laquelle nous sommes condamnés à participer, est un passé qui, en tant que tel, n'est pas modifiable. Saint Thomas a déjà dit dans la Summa Theologiae que ni Dieu ni le passé ne peuvent le changer (ce serait une autre chose de dire que Dieu aurait pu faire en sorte que le passé soit différent). Il n'existe aucun pouvoir, aussi divin soit-il, qui puisse transmuter le passé. Mais il existe un pouvoir, celui de la raison et de la compréhension humaines, qui est capable de "défataliser" le passé. Et comment le passé peut-il être défloré ? En rendant aux masses populaires leur capacité de résistance à l'Horreur. En rendant à la conscience collective de la société son sentiment d'être des sujets dotés d'un pouvoir pratique. L'action d'une masse libre (sans peur) implique nécessairement la "contemplation" du passé, et son assomption ontologique adéquate. Le passé en tant que tel n'est pas modifiable, mais évacuer l'ombre de ce passé qui pèse sur nous est de la responsabilité de ceux parmi nous qui se rangent du côté de l'action des masses, d'un vulgaire qui a perdu sa peur.

L'action d'une masse libre (sans peur) implique nécessairement la "contemplation" du passé, et son assomption ontologique adéquate. Le passé en tant que tel n'est pas modifiable, mais évacuer l'ombre de ce passé qui pèse sur nous est de la responsabilité de ceux parmi nous qui se rangent du côté de l'action des masses, d'un vulgaire qui a perdu sa peur.

Cependant, l'objectivation et l'aliénation ne sont pas la même chose. Nous revenons à A. Prior :

Cependant, l'objectivation et l'aliénation ne sont pas la même chose. Nous revenons à A. Prior : Marx s'inscrit dans la meilleure tradition idéaliste et, avant elle, dans la tradition réaliste aristotélicienne. Ce que Marx a brillamment et grandiosement construit, c'est une ontologie de l'être social, une ontologie de l'homme en tant qu'être essentiellement communautaire qui, depuis son arrivée au niveau de lacivilisation, a toujours lutté contre les forces désintégratrices, dissolvantes, atomistiques. L'ontologie de l'être social est, à la fois, theoria, contemplation de cette réalité qui inclut l'être individuel et collectif lui-même, les êtres contemplatifs, mais en même temps, elle est, nécessairement, une philosophie de la praxis : de l'action consciente dans la société, action qui cherche la transformation des structures politico-économiques qui, parce qu'elles sont injustes, sont irrationnelles et parce qu'elles sont irrationnelles, elles sont injustes.

Marx s'inscrit dans la meilleure tradition idéaliste et, avant elle, dans la tradition réaliste aristotélicienne. Ce que Marx a brillamment et grandiosement construit, c'est une ontologie de l'être social, une ontologie de l'homme en tant qu'être essentiellement communautaire qui, depuis son arrivée au niveau de lacivilisation, a toujours lutté contre les forces désintégratrices, dissolvantes, atomistiques. L'ontologie de l'être social est, à la fois, theoria, contemplation de cette réalité qui inclut l'être individuel et collectif lui-même, les êtres contemplatifs, mais en même temps, elle est, nécessairement, une philosophie de la praxis : de l'action consciente dans la société, action qui cherche la transformation des structures politico-économiques qui, parce qu'elles sont injustes, sont irrationnelles et parce qu'elles sont irrationnelles, elles sont injustes. "Ce que fait Althusser n'est pas tant de confondre la pensée avec le réel que de priver le réel de ses propres déterminants en affirmant l'inconnaissabilité du réel, réduisant ainsi le réel à la théorie."

"Ce que fait Althusser n'est pas tant de confondre la pensée avec le réel que de priver le réel de ses propres déterminants en affirmant l'inconnaissabilité du réel, réduisant ainsi le réel à la théorie."

Le lieutenant général Michael Groen, directeur du Joint Artificial Intelligence Center du ministère américain de la défense, évoque la nécessité d'accélérer la mise en œuvre de programmes d'intelligence artificielle à usage militaire. Selon lui, "nous pourrions bientôt nous retrouver dans un espace de combat défini par la prise de décision basée sur les données, l'action intégrée et le rythme. En déployant les efforts nécessaires pour mettre en œuvre l'IA aujourd'hui, nous nous retrouverons à l'avenir à opérer avec une efficacité et une efficience sans précédent".

Le lieutenant général Michael Groen, directeur du Joint Artificial Intelligence Center du ministère américain de la défense, évoque la nécessité d'accélérer la mise en œuvre de programmes d'intelligence artificielle à usage militaire. Selon lui, "nous pourrions bientôt nous retrouver dans un espace de combat défini par la prise de décision basée sur les données, l'action intégrée et le rythme. En déployant les efforts nécessaires pour mettre en œuvre l'IA aujourd'hui, nous nous retrouverons à l'avenir à opérer avec une efficacité et une efficience sans précédent".

Le pouvoir disciplinaire n'est pas entièrement dominé par la négativité. Il s'articule de manière inhibitrice plutôt que permissive. En raison de sa négativité, le pouvoir disciplinaire ne peut décrire le régime néolibéral, qui brille par sa positivité. La technique de pouvoir propre au néolibéralisme prend une forme subtile, souple, intelligente et échappe à toute visibilité. Le sujet soumis n'est même pas conscient de sa soumission. La toile de la domination lui est complètement cachée. C'est pourquoi il se prétend libre.

Le pouvoir disciplinaire n'est pas entièrement dominé par la négativité. Il s'articule de manière inhibitrice plutôt que permissive. En raison de sa négativité, le pouvoir disciplinaire ne peut décrire le régime néolibéral, qui brille par sa positivité. La technique de pouvoir propre au néolibéralisme prend une forme subtile, souple, intelligente et échappe à toute visibilité. Le sujet soumis n'est même pas conscient de sa soumission. La toile de la domination lui est complètement cachée. C'est pourquoi il se prétend libre.