samedi, 27 février 2021

Premier raid de l'ère Biden : frapper les milices en Syrie

Premier raid de l'ère Biden : frapper les milices en Syrie

Lorenzo Vita

Ex : https://it.insideover.com

L'ère de Joe Biden à la Maison Blanche commence au niveau international avec un premier raid en Syrie. Comme l'a confirmé le Pentagone, le président américain a ordonné un raid de bombardement contre des sites qui, selon les renseignements américains, sont utilisés par des miliciens pro-iraniens dans la partie orientale du pays. "Ces raids ont été autorisés en réponse aux récentes attaques contre le personnel américain et de la coalition en Irak et aux menaces continues contre ce personnel", a déclaré le porte-parole de la Défense John Kirby, qui a précisé que l'attaque avait été spécifiquement menée "sur ordre du président", visant des sites "utilisés par divers groupes militants soutenus par l'Iran, dont le Kaitaib Hezbollah et le Kaitaib Sayyid al-Shuhada". Pour Kirby, le raid "envoie un message sans équivoque qui annonce que le président Biden agira dorénavant pour protéger le personnel de la coalition liée aux Etats-Unis. Dans le même temps, nous avons agi de manière délibérée en visant à calmer la situation tant en Syrie orientale qu'en Irak".

La décision de Biden intervient à un moment très délicat dans l'équilibre des forces au Moyen-Orient. Une escalade contre les forces américaines en Irak a commencé le 15 février et a conduit à plusieurs attaques contre les troupes américaines. L’avertissement est destiné aux forces pro-iraniennes présentes en Irak, qui a toujours constitué un véritable talon d'Achille pour la stratégie américaine au Moyen-Orient. Le pays qui a été envahi par les Américains en 2003 est devenu ces dernières années l'un des principaux partenaires de l'adversaire stratégique de Washington dans la région, Téhéran. Et il ne faut pas oublier que c'est précisément en Irak que le prédécesseur de Biden s'est manifesté. Donald Trump, en effet, avait ordonné le raid qui a tué le général iranien Qasem Soleimani. Une démarche que Bagdad avait évidemment condamnée, étant donné que le territoire sous autorité irakienne est devenu un champ de bataille entre deux puissances extérieures.

Cette fois, c'est la Syrie qui a été touchée. Et cela indique déjà une stratégie précise de la Maison Blanche. Pour le Pentagone, frapper la Syrie en ce moment signifie frapper un territoire avec une autorité qu'ils ne reconnaissent pas et qu'ils ont tenté de renverser. Une situation très différente de celle de l'Irak, où les États-Unis veulent éviter que le pays ne se retourne contre les forces étrangères présentes sur place et où il existe un gouvernement que l'Amérique reconnaît comme interlocuteur. Le fait que le raid ait eu lieu en Syrie mais en réponse aux attaques en Irak, indique qu'ils ne veulent pas créer de problèmes pour le gouvernement irakien.

L'attaque confirme également un autre problème pour l'administration américaine. La présence de milices pro-iraniennes en Syrie et en Irak est un nœud gordien qui est loin d’avoir été tranché. Les généraux américains ont longtemps demandé à la Maison Blanche, sous Trump, d'éviter un retrait des troupes de Syrie, précisément pour exclure la possibilité que les forces liées à Téhéran reprennent pied dans la région. Trump, même s’il était récalcitrant, a néanmoins accepté, en fin de compte, les exigences du Pentagone (et d'Israël) et a évité un retrait rapide des forces américaines. Pour la Défense américaine, il y avait également le risque d'un renforcement de la présence russe (Moscou a condamné l'attaque en parlant d'"une action illégitime qui doit être catégoriquement condamnée"). Ce retrait ne s'est jamais concrétisé, se transformant en un fantôme qui erre depuis de nombreux mois dans les couloirs du Pentagone et de la Maison Blanche et niant la racine de l'une des promesses de l’ex-président républicain : la fin des "guerres sans fin".

Le très récent raid américain n'indique en aucun cas un retour en force de l'Amérique en Syrie. Le bombardement a été très limité et dans une zone qui a longtemps été dans le collimateur des forces américaines au Moyen-Orient. Mais le facteur "négociation" ne doit pas non plus être oublié. Les Etats-Unis négocient avec l'Iran pour revenir à l'accord sur le programme nucléaire : mais pour cela, ils doivent montrer leurs muscles. Comme le rapporte le Corriere della Sera, Barack Obama avait l'habitude de dire : "vous négociez avec votre fusil derrière la porte". Trump l'a fait en se retirant de l'accord, en tuant Soleimani et en envoyant des bombardiers et des navires stratégiques dans le Golfe Persique. Biden a changé la donne : il a choisi de limiter les accords avec les monarchies arabes pour montrer clairement qu'il ne s'alignait pas sur la politique de Trump, en gelant les F-35 aux Émirats et les armes aux Saoudiens qui se sont attaqué au Yémen. Mais en même temps, il voulait envoyer un signal directement à l'Iran en frappant des milices à la frontière entre l'Irak et la Syrie. Tactiques différentes, stratégie différente, mais avec une cible commune : l'Iran.

12:49 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, géopolitique, politique internationale, états-unis, joe biden, syrie, levant, irak, iran, proche-orient, moyen-orient |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

La grande stratégie de l'Allemagne en matière d'hydrogène

La grande stratégie de l'Allemagne en matière d'hydrogène

Andrea Muratore

Ex : https://it.insideover.com

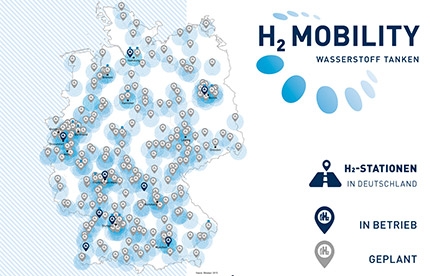

Des investissements publics et privés pour accélérer la conquête de la frontière technologique et de ses applications industrielles et productives concrètes : l'Allemagne, dans le cadre des plans de lutte contre la crise pandémique, pose les bases d'une restructuration de son appareil de production. Et si, d'une part, cela implique d'adhérer à de grands plans stratégiques d'envergure européenne sur la souveraineté numérique, le cloud et l'innovation, d'autre part, le gouvernement d'Angela Merkel, qui s'apprête à passer, après les élections de l'automne prochain, à un exécutif dans lequel la CDU pourrait s'allier aux Verts, a bien en tête les défis de la transition énergétique et la recherche de nouvelles sources propres pour alimenter le transport, l'industrie et la production d'électricité. Dans ce contexte, Berlin mise beaucoup sur les technologies centrées sur l'hydrogène.

Dans le cadre de la stratégie nationale présentée l'été dernier, le gouvernement a jugé bon de fixer des objectifs précis, visant à ce que l'Allemagne construise une capacité d'électrolyse de 5000 mégawatts (MW) d'ici 2030 et de 10.000 MW d'ici 2040 pour produire le nouveau combustible. L'objectif est de faire de l'Allemagne le premier fournisseur mondial de cette source d'énergie propre en mettant sur la table des investissements de 9 milliards d'euros et, selon le quotidien italien Repubblica, "deux des neuf milliards alloués seront destinés à des partenariats internationaux pour l'approvisionnement. L'idée est de créer un système délocalisé dans les pays du Golfe et en Afrique du Nord en utilisant l'énergie solaire pour alimenter les centrales de production".

Quels sont les objectifs de l'Allemagne? Tout d'abord, construire une chaîne complète d'approvisionnement en hydrogène, en partant des machines d'électrolyse et en arrivant à la construction d'usines fonctionnelles capables d'alimenter des technologies de grande consommation tant en termes d'applications industrielles que dans le domaine des transports. Sur le plan de l'ingénierie des centrales, la conversion des centrales à charbon en centrales de production de cette source moins polluante et plus efficace est envisagée : Par exemple, la collectivité locale de Hambourg, ‘’Warme Hamburg’’, pense, en synergie avec la société suédoise qui la possède, ‘’Vattenfall’’, et deux partenaires industriels (Shell et Mitsubishi Heavy Industries), à proposer aux autorités de la ville et au gouvernement la reconversion de la méga centrale au charbon de Moorburg, près de Hambourg, qui ne fonctionne que depuis six ans, compte tenu du retrait total de l'Allemagne du charbon en 2038.

Dans le domaine des applications industrielles, il faut souligner la possibilité de construire une part croissante de trains, d'autobus et, à l'avenir, de véhicules privés fonctionnant à l'hydrogène, mais surtout l'utilisation du matériau le plus léger du tableau périodique en tant que matière première pour l'une des industries clés du pays, l'industrie sidérurgique, qui, à l'échelle mondiale, s'oriente vers une durabilité croissante. Thyssen Krupp étudie des projets de grande envergure en synergie avec Steag, la société énergétique allemande, pour fournir de l'hydrogène à son usine sidérurgique stratégique de Duisburg.

Mais il peut également y avoir des effets en cascade sur l'équilibre de l'énergie européenne : il est encore difficile d'imaginer, par exemple, quelles pourraient être les futures relations politiques et économiques entre l'Allemagne et la Russie si le gaz naturel (fourni à profusion par Moscou à Berlin) était ajouté au bouquet énergétique allemand, une source générée par les chaînes d'approvisionnement internes. Il est clair que des gazoducs tels que le Nord Stream 2 ne disparaîtraient pas de la scène et pourraient même redevenir utiles grâce à une application à double usage pour transporter et acheminer l'hydrogène également.

L'Allemagne a compris que dans le contexte des changements de paradigmes technologiques, la bataille porte sur les chaînes de valeur et leur contrôle, et que par conséquent, la mise en place de normes technologiques et d'applications opérationnelles de référence au niveau européen et mondial crée un avantage concurrentiel de grande envergure. En ce sens, il ne faut pas sous-estimer le rôle stratégique de l'Institut Fraunhofer, un organisme de projection de l'intervention publique en faveur de la recherche et du développement technologique pour les petites et moyennes entreprises, qui représente légalement un organisme public à but non lucratif financé par l'État fédéral allemand, les Länder et, en partie, par des contrats de recherche.

"En plus du travail à façon", note M. Domani, l’Institut Fraunhofer "vise également à acquérir un ensemble de brevets dans des domaines d'application industrielle future qui seront mis à la disposition des petites et moyennes entreprises allemandes", représentant en ce sens un accélérateur technologique qui, dans des secteurs tels que celui de l'hydrogène, où l'innovation se produit à un rythme rapide, est fondamental. D'autant plus si l'on considère que l’Institut Fraunhofer reste souvent propriétaire des licences acquises : récemment, sur le front de l'hydrogène, une pâte spéciale a été brevetée qui permet une conservation plus facile et un stockage plus pragmatique du carburant piégé.

Un exemple de percée technologique née d'une synergie public/privé, une vision à laquelle même des pays comme le Japon s'adaptent et où l’Italie peine à décoller. En Italie, pour rester dans le domaine de l'hydrogène, la course est menée par quelques grands acteurs consolidés (de Snam à Saipem, d'Eni à Edison) et une chaîne de petites et moyennes entreprises doit être soigneusement construite pour permettre au pays de ne pas être à la traîne dans une course à laquelle Berlin participe activement. La fondation Enea Tech, créée en novembre dernier grâce au Fonds de transfert de technologie mis en place au ministère du développement économique avec une dotation de 500 millions d'euros, peut être la clé de voûte de la planification stratégique dans les domaines frontières: et la logique du système, dans le domaine de l'hydrogène, doit être surveillée de près, étant donné que son développement combine la dynamique énergétique, les questions environnementales, la consommation privée et l'industrie. Un "laboratoire" des futures révolutions technologiques et des changements de paradigmes qui animeront un monde de plus en plus complexe.

12:29 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, actualité, europe, affaires européennes, énergie, hydrogène, technologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Dix déviations contre-révolutionnaires qui sabotent la véritable dissidence

Raphael Machado

Dix déviations contre-révolutionnaires qui sabotent la véritable dissidence

Ex: http://www.novaresistencia.org

Dans l'ensemble, le milieu politique dissident, c'est-à-dire anti-libéral et anti-moderne, s'est beaucoup développé au cours des dix dernières années dans notre pays (le Brésil). Néanmoins, il est encore assailli par certaines maladies et déviations infantiles qui sabotent sa croissance.

Le milieu dissident est plein de dérives assimilables à du sabotage et d'idées contre-révolutionnaires. Dans de nombreux cas, ces dérives et idées sabotent élan et croissance de la dissidence et les idées contre-révolutionnaires se propagent avec une naïveté déconcertante. Dans certains cas, le sabotage idéologique est intentionnel et vise à paralyser ou à fragmenter la dissidence.

Même si ces idées sont agrémentées de phrases d'Evola et de Nietzsche, de photos de familles américaines des années 50 ou de statues d'Arno Breker, ce sont toutes des idées contre-révolutionnaires qu'il faut faire disparaître de notre milieu, par tous les moyens à notre disposition.

Une critique dissidente de la dissidence est devenue indispensable.

10 - Bucolisme infantile

D'une manière générale, le milieu dissident a depuis longtemps surmonté un certain optimisme historique lié au futurisme et s'est retranché dans une critique radicale de l'urbanisation, de la mécanisation des relations humaines, de la foi dans la technologie et d'une certaine artificialisation induite par l'éloignement de la nature et des cycles naturels.

Face à cela, il est devenu courant d'idéaliser la "vie à la campagne", avec ses "blondes dans les champs de blé" et ses "cabanes dans les bois" (avec wifi, bien sûr). Il n'y a aucun problème à décider de vivre dans une petite ville ou de cultiver la terre. Le problème survient lorsque cela est considéré comme un substitut à l'action et à l'activisme politiques.

En effet, il y a quelque chose à célébrer dans la paysannerie, dans la culture de la terre, dans les relations humaines les plus étroites, mais tout cela doit être mobilisé comme un symbole pour motiver une lutte politique concrète, à mener aussi dans les villes. En dehors de la lutte politique objective, cette fugere urbem n'est rien d'autre qu'une lâcheté conservatrice déguisée en traditionalisme.

9 - Domesticité bourgeoise

Un autre moyen largement utilisé dans la dissidence pour légitimer sa propre inertie et sa lâcheté est la cantilène selon laquelle "aujourd'hui, la véritable révolution est de se marier et d'avoir des enfants", qui n'est pas rarement associée au point précédent. Parmi les incels, l'idée de fonder une famille peut sembler être une grande réussite, mais en dehors de cet environnement, il est étonnant qu'elle soit présentée comme une bannière.

Bien sûr, notre époque postmoderne de capitalisme tardif et de liquéfaction des identités implique une certaine répétition des évidences que sont "le ciel est bleu" et "2 + 2 = 4", donc à une époque où les gens ont "l'hélicoptère de combat" comme genre, il peut effectivement sembler quelque chose d'un autre monde d'épouser une personne du sexe opposé et d'avoir des enfants à l'ancienne, mais il n'y a rien de particulièrement révolutionnaire à se marier et à avoir des enfants, et cela ne remplace pas non plus l'action politique.

La perpétuation de la lignée familiale a toujours été considérée comme importante dans toutes les sociétés traditionnelles, mais c'est une chose naturelle à faire et, sauf pour ceux qui ont une vocation monastique ou similaire, c'est le strict minimum.

Contrairement à tout traditionalisme authentique, ce discours n'est qu'un appel à la domesticité bourgeoise, où le foyer est le centre de la vie de l'homme et où ses préoccupations tournent autour du "paiement des factures" et de la "croissance dans la vie".

Lorsque vous vous retirez de l'action politique pour jouer au "papa et à la maman", vous ne faites que confier à vos enfants les tâches politiques urgentes de notre époque.

8 - La peur de la politique partisane

Dans la rhétorique dissidente, on trouve souvent un certain moralisme antipolitique qui jette l’anathème sur toute implication dans la politique des partis bourgeois en la qualifiant de "corruption", de "trahison", etc. Ce discours est typique de l'infantilisme conformiste déguisé en radicalisme politique dissident.

Psychologiquement, ce refus de s'impliquer dans la politique des partis bourgeois exprime une certaine crainte générale par rapport au monde adulte. C'est une sorte de "syndrome de Peter Pan", mais appliqué à la politique. Pour adhérer à un parti politique, il faut être un homme de 30 à 40 ans qui n'a pas encore réussi à mûrir sur la "scène" depuis son adolescence.

Le monde de la politique des partis bourgeois est célèbre pour ses compromis, ses accords, ses négociations, ses alliances pragmatiques, etc. Tout ce qui provoque le dégoût et inspire le mépris à tout dissident, ce qui est parfaitement justifié. Néanmoins, dans les conditions concrètes de pratiquement tous les pays de l'hémisphère occidental, la participation à la politique des partis est l'un des moyens les plus importants pour atteindre le seul véritable objectif qu'un dissident devrait avoir : le pouvoir.

Même si l'on veut détruire le système des partis, il faut renverser les rôles et mettre fin au jeu le plus vite possible, même si chaque dissident qui n'a pas d'implication ou d'initiative dans ce domaine, ne serait-ce que secondairement, doit être considéré comme un amateur ou assimilé à des anarchistes bobos.

7 - Spontanéité paresseuse

Si l'on demandait à Lénine, ou à son héritier italien Mussolini (ce n'est pas moi qui le dit, mais Lénine lui-même...), quel est le chemin à suivre pour la révolution, ils souligneraient le travail invisible des petites fourmis : les heures passées à taper, le temps perdu à décider et à organiser des questions logistiques insignifiantes, à écrire des articles pour de petits journaux locaux ou à faire des discours devant une douzaine de personnes.

L'action politique révolutionnaire n'est pas du tout romantique. Le romantisme vient plus tard, avec les poètes de la révolution.

Face à cette réalité souvent fastidieuse, de nombreux dissidents plaident pour le "réveil du peuple". C'est l'idée que finalement (un "éventuellement" messianique et millénaire qui pourrait être demain ou dans mille ans...) le peuple se fatiguera de "tout ce qui est là", et alors il se rebellera spontanément et renversera le gouvernement.

Naturellement, à ce moment-là, les gros granudos sortiront de leur 4x4 pour guider, en tant que patrons naturels et shiatters innés, les masses en révolte. Une illusion qui serait balayée par la lecture de La rébellion des masses d'Ortega y Gasset ou de La psychologie des foules de Le Bon. À cette foi paresseuse dans le réveil spontané des masses est généralement lié le point précédent, la crainte de la politique des partis.

En général, ceux qui lancent des anathèmes à ceux qui adhèrent à des partis, contestent les élections, etc., affirment que si nous diffusons suffisamment de critiques sur l'Holocauste, ainsi que des images de statues nues dans une esthétique vaporeuse, finalement "tout ce qui est là" changera.

6 - Défaitisme idéaliste

Honnêtement, je n'ai jamais pris au sérieux cette vieille idée selon laquelle, dans le sport, il s'agit de faire de la compétition ou de "faire de son mieux" et non de gagner. Il est évident que le plus important est de triompher ! Pour gagner des médailles ! Atteignez la notoriété ! Pour être reconnu comme l'un des meilleurs !

Dans le même sens, en politique, j'ai toujours instinctivement détourné les yeux chaque fois que j'entendais, dans les milieux dissidents, quelqu'un commencer cette litanie du "le plus important n'est pas de gagner mais oui"... Maintenant, si vous n'êtes pas intéressé par la victoire, que faites-vous en politique ? Nourrir votre propre ego ?

Parmi de nombreux dissidents, il y a cette notion selon laquelle l'idéologie "de droite" accorde d'avance une "victoire morale" qui rend toute victoire concrète, objective et historique superflue. Vous êtes peut-être une personne isolée dans un kitnet avec une page Facebook suivie par 200 personnes, mais parce que vous avez lu quelques livres de Julius Evola, vous êtes en fait une kshatriya et vous êtes destinée au Valhalla. Ou bien vous pourriez avoir un "mouvement" d'une demi-douzaine de personnes qui ne font absolument rien d'autre que de traîner, de temps en temps, dans les bistrots pour boire et faire de la prose.

Si l'on demande à l'un de ces dissidents ce qu'il a l'intention de faire pour prendre le pouvoir, ou pourquoi exactement les choses ne semblent aller nulle part, il vous répondra inévitablement que "c'est la faute de [insérer ici, indistinctement, des juifs, des maçons, des musulmans, des communistes, ou de tous à la fois]". Bien sûr, ils ne sont pas responsables du fait qu'ils n'ont littéralement aucune stratégie, ni même un simple plan qui ait un sens.

Voyez : ils pourraient au moins essayer. Mais même pas cela. La "victoire morale" les a déjà satisfaits. Il n'est pas rare que ces types correspondent également à tous les vices idéologiques décrits ci-dessus.

5 - Accéléralisme naïf

Une infection aggravée par le contact avec les médias de droite avec son mythe du "boogaloo", dans la dissidence ne manquent pas ceux qui croient fermement que "Le Système" est au bord de l'effondrement, et que même demain le monde peut se transformer en un scénario de Mad Max.

Que ce soit à cause de ce pic pétrolier (qui, avouons-le, est tombé en désuétude), d'une révolution mécanique, d'une guerre civile mondiale, de la non-durabilité innée du capitalisme, ou pour toute autre raison, les dissidents ayant certaines tendances survivalistes (généralement seulement virtuellement) se préparent à "la fin".

Ils croient donc qu'ils descendront dans la rue armés pour restaurer la "société traditionnelle". Outre le fait qu'ils vont se retrouver dans la rue avec le Commandement rouge, le Premier Commandement de la capitale et la Ligue de justice, ce qui risque d'être tragique, le principal problème est que ce scénario est un fantasme qui sert à écarter la nécessité d'un militantisme méthodique, d'une construction approfondie du processus révolutionnaire et du pragmatisme politique. Nous n'avons pas besoin de faire quoi que ce soit, il suffit d'acheter des boîtes de thon et d'avoir un P38 pour "protéger la famille".

La grande crainte que cette catégorie de dissidents évite de rencontrer est que nous sommes déjà "à la fin". Une fin qui, si elle est laissée à l'inertie, n'aura pas de fin. Remplacez "La fin est proche" par "Cela ne finira jamais".

4 - Trotskysme dissident

Un problème commun dans le milieu dissident, et pas seulement au Brésil, est une certaine tendance au sectarisme basée sur un puritanisme idéologique qui transforme tout désaccord minimal sur des questions secondaires en contradictions majeures.

En ce sens, au lieu d'avoir une seule grande organisation dissidente (naturellement, avec ses filières), nous voyons proliférer une myriade d'organisations nationalistes aux objectifs extrêmement spécifiques, avec un nombre de membres variant entre 1 et 20, et qui disparaissent aussi vite qu'elles sont apparues.

Parfois, il ne s'agit même pas de puritanisme idéologique, mais simplement d’un problème d'ego chez les dissidents qui sont totalement incapables de s'intégrer dans une hiérarchie et de se conformer à une discipline révolutionnaire, et qui craquent sur tout désaccord personnel.

3 - Nécromancie politique

Photographies en noir et blanc, références constantes à des idoles politiques décédées, liste bibliographique presque entièrement occupée par des rafistolages poussiéreux du XIXe et du début du XXe siècle sur des sujets aussi actuels que la voiture à manivelle.

Nous l'avons tous vu et nous continuons à le voir dans les véhicules et les canaux de propagande de nombreux groupes dissidents, ou même si ce n'est que dans leurs profils personnels.

De nombreux dissidents sont prisonniers du passé. Besoin émotionnel ? Il est impossible de le dire, mais ces dissidents semblent toujours se sentir en insécurité ou même menacés lorsqu'il s'agit d'aborder des questions contemporaines avec des auteurs contemporains originaux (et non de simples commentateurs ou répétiteurs de morts).

La tradition, pour ces dissidents, n'est pas une lumière qui offre la possibilité d'une libération spirituelle, mais une tonne d'entraves qui se lient à des slogans répétés ad nauseam. Tout comme il existe une "seule pensée politiquement correcte" dans le monde post-libéral, il existe une "seule pensée politiquement correcte" dans le monde dissident, basée sur le fait de traiter littéralement comme la Bible toute œuvre écrite par une quelconque personnalité de la Troisième Théorie Politique, liée à des régimes défunts.

En essayant d'être optimiste, au moins ce n'est pas comme la gauche libérale, qui a transformé les livres de Harry Potter en Bible...

2 – Anti-étatisme pseudo-traditionnel

Que ce soit par infiltration libérale ou par simple opportunisme en voulant faire converger les ancêtres mythifiés et les libertaires d’aujourd’hui, il y a une minorité dans la dissidence qui ne fait délibérément pas assez la distinction entre la critique de l'État moderne et la critique libérale de l'État.

Bien sûr, ces "théonomes" déclineront leur philo-libéralisme dans toutes les teintes traditionnelles possibles, des citations de Nietzsche aux appels à une "critique d'en haut" en passant par un élitisme puéril. Mais la conclusion est la même: l'État doit être détruit pour pouvoir ensuite être "reconstruit", mais cette fois-ci de manière traditionnelle, authentique, organique.

Le soutien à ces critiques ne fait pas rougir, ce qui suscite une suspicion sincère.

En fait, d'un point de vue traditionnel, tout État, même moderne, vaut mieux que le plongeon chaotique et a-nomal dans l'indifférenciation postmoderne. L'État, même en tant que forme pure, n'est pas quelque chose de vide de sens et n'équivaut pas à l'Anarchie. C'est la base de la pensée politique d'Evola.

C'est un curieux "traditionalisme" qui a des points communs avec le libéralisme foucaldien et avec le post-marxisme autonomiste de Toni Negri et Michael Hardt, ainsi qu'avec les idées de Murray Rothbard et Hans-Hermann Hoppe. Dans des cas comme celui de Marcos Ghio, ces notions en viennent même à être associées au soutien à l'ISIS et à Al-Qaida, au point que "défendre Assad, c'est défendre l'État moderne et anti-traditionnel". Ces arguments sont également apparus chez les néo-nazis qui entendaient justifier leur soutien au terrorisme ukrainien contre les populations du Donbass ainsi que leur anti-poutinisme. "Poutine est un bourgeois !"

Tous sont les apôtres d'un affaiblissement généralisé de l'État comme moyen de parvenir à un "ordre plus juste".

Il est évident que nous savons ce qui se cache derrière tout cela et où ces idées circulent.

1 - Fétichisme marginal

Demandez à n'importe quel penseur dissident de ces cinquante dernières années ce qu'il faut faire et ils vous diront tous unanimement qu'il faut boire à la fontaine de Gramsci pour favoriser la pénétration institutionnelle de nos idées.

Il est nécessaire de produire un contenu académique, il est nécessaire d'adhérer et de participer activement à des syndicats, il est nécessaire de faire du militantisme de base et d'organiser des communautés, il est nécessaire de produire de l'art dissident, il est nécessaire de construire des contacts et des réseaux d'influence avec les partis politiques, il est nécessaire d'utiliser les réseaux sociaux pour essayer de populariser les idées dissidentes. Popularisez, ils insisteront. Ne pas augmenter le nombre de "marginaux".

Néanmoins, il y a encore de nombreux dissidents qui insisteront sur les comportements les plus innocemment marginaux, tout en se faisant passer pour des radicaux. Faux personnages de dessins animés, théories de conspiration complètement folles, MGTOW, et tout un tas d'autres manies et fétiches qui suscitent le dégoût des gens ordinaires, même ceux qui ont tendance à être en désaccord.

La réalité est qu'il y a beaucoup de gens qui se sentent plus à l'aise dans un petit créneau politique, généralement ignoré par les médias et les organismes publics, et qui feront le possible et l'impossible pour maintenir la dissidence dans une bulle.

11:40 Publié dans Actualité, Définitions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, définition, dissidence |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 26 février 2021

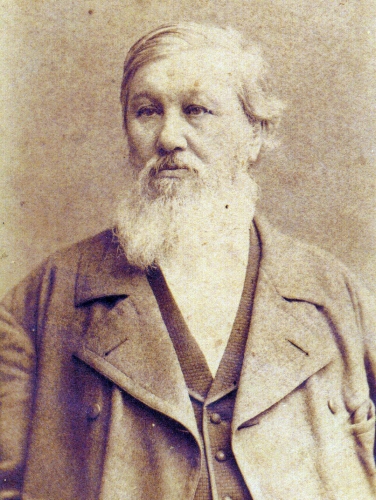

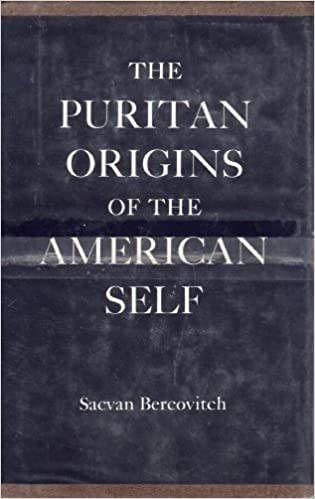

Les Pages nordiques de Robert Steuckers

Les Pages nordiques de Robert Steuckers

par Georges Feltin-Tracol

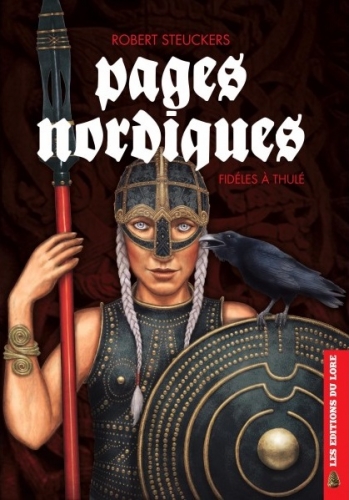

Recension: ROBERT STEUCKERS, Pages nordiques. Fidèles à Thulé, Éditions du Lore, 2020, 100 p., 15 €.

Les excellentes Éditions du Lore poursuivent à un rythme toujours soutenu la publication des nombreux articles, recensions et conférences de l’Européen Robert Steuckers. Après Pages celtiques en 2017 (cf. SN 48), voici maintenant un nouveau recueil qui explore un monde nordique souvent lié à l’univers celtique.

Dix textes forment cet ouvrage qu’il importe de mettre dans toutes les mains, à l’exception de ceux qui croient encore à la fable de la « Lumière » venue d’Orient, de Mésopotamie et d’Afrique. Aidé par les découvertes archéologiques, Robert Steuckers examine d’un œil neuf la thèse de Jürgen Spanuth pour qui l’Atlantide se situe en Mer du Nord et dont l’île d’Héligoland serait l’une des dernières traces physiques.

L’ancien directeur des revues Vouloir et Orientations insiste sur l’action des Vikings, en particulier en Amérique du Nord dès l’An Mil. Leurs multiples expéditions et les leçons qu’ils en tirent alimenteront bien plus tard la curiosité du Génois d’origine corse Christophe Colomb. L’auteur établit par ailleurs une chronologie didactique dédiée au « Retour de la conscience païenne en Europe » de 1176 à 1971. On y apprend que le poète pan-celtique Charles De Gaulle (l’oncle de…) « appelait [...] les peuples celtiques à émigrer uniquement en Patagonie » nommée par le Gallois Michael D. Jones « Y Wladfa ». Ce dernier décida d’y implanter une colonie éphémère. Quel impact a eu cet article de 1864 sur le futur roi des Patagons Orélie-Antoine de Tounens ? La patrie patagone chère à Jean Raspail aurait-elle donc une origine celtico-nordique projetée dans l’hémisphère austral ?

L’auteur de Pages nordiques évoque enfin le culte de la Déesse-Mère. Il remarque que « la Terre-Mère, dans ces cultes, est fécondée par l’astre solaire, dont la puissance se manifeste pleinement au jour du solstice d’été : la religion originelle d’Europe n’a donc jamais cessé de célébrer l’hiérogamie du ciel et de la terre, de l’ouranique et du tellurique ». On a perdu Alice Coffin et Pauline Harmange !

Avec son immense érudition, son sens de l’éclectisme et sa polyglossie, Robert Steuckers interprète depuis un angle différent les références spirituelles de la civilisation européenne. Celle-ci ne se cantonne pas au triangle Athènes – Rome – Jérusalem. Elle intègre l’héritage du Nord et de l’Ouest. On attend par conséquent avec les prochains volumes : Pages slaves, Pages germaniques, Pages latines, Pages balkaniques, Pages helléniques, etc.

Pour commander l'ouvrage: http://www.ladiffusiondulore.fr/home/849-pages-nordiques-fideles-a-thule.html

19:01 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Synergies européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, robert steuckers, synergies européennes, nordicisme, scandinavie, histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

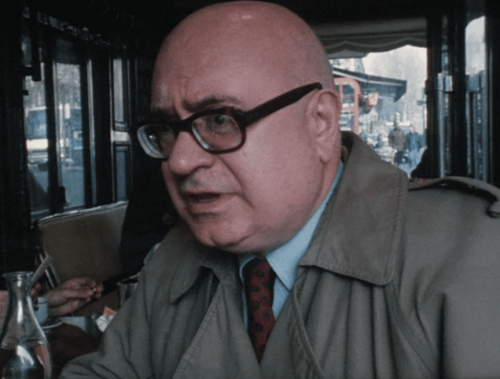

Présence de Jean Parvulesco : Rupture du temps indo-européenne

Présence de Jean Parvulesco:

Rupture du temps indo-européenne

Avant-propos de de Laurent James :

Le samedi 12 novembre 2016, quelques pratiquants de la prose enchantée de Jean Parvulesco se réunirent en l’église princière du Monastère de Negru Voda au cœur de la Valachie roumaine, afin de célébrer une Panikhide – Vigile pour le repos du défunt et consolation pour ses proches – lors du sixième anniversaire de la naissance à Dieu du grand écrivain.

Décision fut prise en l’occasion, à l'initiative de son fils Constantin et de ses petits-fils, le Prince Stanislas d'Araucanie et Cyrille Duc de Zota, de fonder le Comité Jean Parvulesco. Celui-ci vise non seulement à entretenir la mémoire de l’écrivain, mais surtout à prolonger sa pensée géopolitique d’avant-garde dans l’histoire contemporaine…

Plusieurs conférenciers intervinrent en suite du service liturgique mémoriel, pour évoquer la personnalité de celui qui écrivait que La géopolitique transcendantale est une mystique révolutionnaire en action, tout en mettant en avant les racines spirituelles du continent eurasiatique. Cette journée confidentielle fut le prodrome des futurs colloques de Chișinău (République de Moldavie) dont l’importance géostratégique est aujourd’hui notoirement reconnue au niveau international.

Une plaquette – conçue et illustrée par Pellecuer – fut éditée à cette occasion sous le titre Présence de Jean Parvulesco, recueillant les interventions de Robert Steuckers, Laurent James, Emmanuel Leroy, Vanessa Duhamel, Iurie Rosca, Alexandre Douguine, et celle de Marc Gandonnière dont le texte est reproduit ci-après.

Ce n’est pas lui faire injure que de révéler que Christophe Bourseiller fut l’un des premiers à commander notre recueil. C’est peut-être la présence ainsi réactualisée de Jean Parvulesco qui lui donna l’idée de partir aussitôt à sa recherche !

La première édition ayant été rapidement épuisée, et considérant les demandes qui nous ont été faites, nous avons décidé de procéder à une nouvelle édition, revue et augmentée.

Le recueil est disponible exclusivement à la commande, au prix de 12 € (frais de port inclus), à l’adresse suivante : j_parvulesco@orange.fr

Actualités à suivre sur la page Facebook : Présence de Jean Parvulesco

Laurent James (https://www.parousia.fr/)

(c) Laurent Pellecuer

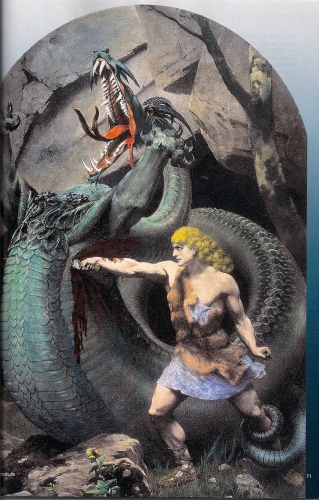

LE SARCOPHAGE DU SOLEIL :

Quand l’épouvante immense des ordalies du non vouloir s’élève au dessus des chairs sollicitées, quand se réveillent en nous les morts d’une race démantelée aux frontières du grand sommeil : aux frontières de l’Inde Aryenne, l’oubli en nous de l’être des principes du souffle pourvoyeur des hauts plateaux analogiques de l’allégeance heideggerienne à l’auvent du sang de Souche ancienne à la noire terre buissonnante de Runes d’Argent, de Vallombreuses ensauvagées quand les fenêtres aveugles du blockhaus supratemporel des nôtres irradient l’insoutenable éclat sur sarcophage que Damian rebâtit en rêve. Ainsi la seconde mort nous vint elle avec l’extinction du soutien de la vallée sous les glaciers d’Europe et désormais nul redressement ne nous sera possible…

L’Histoire elle-même est achevée. La plus grande Histoire… Mais l’Inde restera toujours le coeur du vertige, l’oeuvre de Damian toujours y puisera l’eau brûlante, l’eau vive de ses étincelantes piscines astrales, de ses canalisations sephirotiques dont le discours à peine murmuré dans la nuit de forme originelle reproduit sans fin l’immaculée donation, l’éclat de la Levée Première. Car l’Inde au tréfonds de Damian redevient la terre du seul départ, la terre de la seule arrivée ? Jeune Mère abandonnée au bord de la route au bord du fossé des larmes noires. De quel précipice d’épouvante, de quels effacements s’y reconstitue, ainsi, la chaîne mentale de l’Unique Déesse Clémente… Dans l’eau salvatrice de la baignoire notre double nudité qui lentement devenait nuptiale, cette nudité absolument nouvelle et qui s’imposait d’elle à moi et de moi à elle me paraissait déjà répandre comme une aura de sainteté et de gloire vivante une lumière en quelque sorte Thaborique. Tous bas je répétais en moimême les derniers vers de Benvenita : « Déjà je ne suis plus où je suis, la dérogation de ma pensée rejoint clandestinement le réduit en troncs de sapins sur un rocher d’amnésie, qui mentalement surplombe la gorge de l’ Indus, tous près de l’autre frontière ; les jours sont aveuglants de clarté, et glaciales les nuits en dessous d’un feu de ronces ; or bientôt je ne retournerai plus dans ces draps d’où chaque nuit je prends mon départ là bas ; bientôt j’y resterai à demeure et quand viendront les grandes neiges, on m’enverra aussi l’épouse des hauteurs, la Benvenita, toute nue sous sa tunique de scintillantes haleines blanches, la pourvoyeuse d’être. »

CANTOS PISANOS :

Ainsi marqué par la « Lumière noire d’Apollon » qu’avait entrevue, un jour, Aimé Patri, par cette mystérieuse et troublante « lumière des loups » dont parlent les traditions hyperboréennes de la Grèce antérieure, l’existence d’Ezra Pound n’aura été qu’un long et terible vertige d’écartèlement au-dessus des gouffres intérieurs de l’état d’exil , de l’état de loup garou dans l’appartenance occulte du Dieu Noir, de l’Apollon luimême, crucifié sur les ténèbres intérieures du soleil, au-dessus du Puits du Soleil ?… Nul ne saurait aller au Père si ce n’est par moi. Nul ne saurait être admis à la vision totale solaire impériale, à la fois ardente et limpide d’Apollon Phoïbos, le « resplendissant » s’il n’est descendu lui-même… jusqu’aux tréfonds interdits et obscurs où veille l’Apollon noir, l’instructeur et maître de la lumière hyperboréenne du « Soleil des Loups »… C’est réduire l’Argrund nocturne des origines ontologiques par l’Abgrund pré-ontologique l’intransif… seule la poésie, le sentier Aryen oublié livrera l’ouverture occulte vers les chemins qui portent la délivrance absolue… ce sentier Aryen oublié qui est peut être aussi le sentier Védique de la poésie la plus grande est essentiellement un sentier d’exil de rupture totale, de départ sans retour et de déportation…

Chaque fois que quelqu’un se souvient de ce qui se situe indéfiniment au de-là de l’oubli, le monde de l’oubli disparaît, comme par enchantement, et c’est bien là dans une soudaine rupture des interdits, que réside et se lève le souffle vivant de la part à jamais hors d’atteinte du double mystère hyperboréen – mystère de la glace et mystère du feu – agissant à travers la spirale ascendante de « l’éternel retour » du Sang Majeur… Longtemps, très longtemps, à Tübingen, sur les rives du Nukar, Hölderlin sut montrer qu’il n’était plus lui-même, qu’il était devenu – définitivement – cette Allemagne éternelle dont la figure préontologique était censée illuminer, depuis les hauteurs, la totalité du cycle de destin continental qu’il avait ainsi ramené, lui-même, à ses principes, à son être eidétique, où la Garonne s’identifiant visionnairement – hypnagogiquement – avec le Rhin, avec l’Oxus, avec l’Indus, avec la rivière éternelle de l’être se rejoignant lui-même à travers le lointain des Terres, des sables, des gouffres occultes du non être et de ses dominations de l’ombre.

IOSIS :

L’Inde m’est loin, toujours, et la verte Irlande où se meurt elle, déshonorée ontologique et dans la honte ?… Le cher, le très cher roucoulement de l’invisible oiseau, bleu, sombre et rouge profond de l’invisible oiseau polaire de Kalki, teint de sang frais et teint d’un bleu terreux, de l’invisible oiseau Kalki teint d’indigo brûlant et bouillonnant, qui me redit en courtoisie ces mots à bout de souffle, qui me chuchotte les mots mêmes du dormeur royal… in dem innern Indiä et Montselvache localisé avec le Roi Arthur, dans l’Inde Intérieure, l’endroit où, en quittant l’Europe, se seraient retirés les

(c) Laurent Pellecuer

Les mots que je prépare cette nuit de Samhain pour les amis de Jean Parvulesco ne sont pas destinés à convaincre, à informer, pour ajouter à tout ce qu’ils savent et comprennent très bien déjà. Ils sont arque boutés sur divers textes du prêtre Jean Roumain en renfort à celui qui voyait dans l’écriture un combat métaphysique total, afin d’impulser un peu plus la quête de chacun vers ce Graal du grand rêve Eurasiatique Impérial de la fin ou du grand recommencement plus exactement.

Je viens de relire trois textes du Cahier Jean Parvulesco des Nouvelles Editions Européennes paru en 1989 : Deux grands poèmes sidéraux : « Le Sarcophage du Soleil », « Iosis », puis un texte composé à partir des débris d’une épave échouée, un livre perdu comme les mots substitués d’une parole perdue dont il faudra s’accommoder, un texte sur Ezra Poun : « Cantos Pizanos, fragments et notes de ses carnets du Bunker Palace hôtel ». Le départ d’Ezra Pound, son exil, c’est le fait de l’exil de l’Amérique elle-même hors d’elle et c’est notre perte d’un non-lieu, celui du rêve américain comme une répétition de la chute originelle. Le départ de tout poète rend sa terre natale orpheline, terre d’exil. La Roumanie, la France et l’Europe le sont de l’absence de Jean Parvulesco. Mais ce que dit Jean Parvulesco au sujet de Pound, concernant sa générosité, sa charité ardente, son enthousiasme d’homme au milieu des ruines à soutenir toutes les jeunes pousses de relevailles ontologiques, voilà qui s’applique à sa personne. Sa personne, je la regarde, je la devine dans les cendres du poème de Joachin Du Bellay, je regarde dans les cendres, moi qui n’ai su être des vôtres lors des funérailles de notre ami commun « Dites esprits (ainsi les ténébreuses Rives du Styx) non passables en retour vous enlaçant d’un trois fois triple tour n’enferment point vos images ombreuses. » (Les Antiquités de Rome).

L’exil de l’Europe, nous ne finissons plus d’en distiller les remugles, d’en poser les pierres tombales. Faut-il remonter à Dante, le Gibelin désenchanté devant la piètre épopée de l’Alto Arrigo, comme il le nomme dans la Divine Comédie ? Henri VII de Luxembourg, Empereur du Saint Empire Germanique était nouvellement élu succédant au Stupor Mundi, Frédéric II de Hohenstaufen. Ce dernier mena la seule victorieuse et la moins meurtrière des croisades en terre sainte. Que reste-il de son rêve Impérial lorsque l’Alto Arrigo meurt en 1313 (empoisonné) sans avoir pu reprendre la chère Florence de Dante ? Et Dante le dernier des hommes civilisé d’Europe comme on parle des derniers pères de l’Eglise, a été déçu. Que devraient dire les rêveurs d’Europe en 2016 : les guerres de religions ont précédé les révolutions, guerres européennes mondialisées, les parodies sanglantes d’Empire, Napoléon, Hitler. Je ne dresse pas le tableau de l’Europe libérale soumise à un autre Empire, rongée par la corruption des lobbies financiers et industriels. Julius Evola avec son idée Impériale et Gibeline dans Le mystère du Graal, cite un vieux conte Italien : « Le prêtre Jean très vieux Seigneur Indien fit apporter à Frédéric II un vêtement incombustible en peau de Salamandre, l’eau de l’éternelle jeunesse et un anneau avec trois pierres chargé de pouvoirs surnaturels, mandat supérieur pour rétablir un lien avec le Roi du Monde. » Pouvons-nous oublier encore la dernière trace laissée dans son journal intime par Joseph De Maîstre : Je pars avec l’Europe, c’est aller en bonne compagnie. (25/02/1882) ? Et qui aurait pu espérer qu’il soit tenu compte des avertissements offerts par le philosophe d’éternité dans ses Entretiens de Saint Pétersbourg X et XI montrant la voie par laquelle il n’y aura d’Europe Catholique ni chrétienne, ni d’Europe tout court.

A propos d’avertissements :

J’ai par devers moi ici un courrier de Jean Parvulesco daté du 26 mai 2000 me remerciant de la signature de mon nomen sacrum Marc Valois apposée à son Manifeste Catholique d’Empire qui disait-il restera. Dans ce courrier Jean Parvulesco abruptement presque me dévoilait ses certitudes sur le contenu du 3ème secret de Fatima en plus de l’attentat contre Jean Paul II : épreuves finales de l’Eglise auxquelles celle-ci n’échappera que si nous autres sommes capables de faire ce que nous devons faire. A l’époque je pensais il faut l’avouer, que les craintes de notre ami étaient infondées, le temps des épreuves et des persécutions, depuis la fin du communisme, étant révolu… Or il y a plus parmi les chrétiens d’orient aujourd’hui de martyres que pendant les premiers siècles de l’Eglise !!! Son courrier précédent, daté du 22 mai de la même année, délimitait l’espace géopolitique concerné par son Manifeste : Europe de l’Ouest, de l’Est, Russie et Grande Sibérie, Inde et Japon. Et de préciser : l’Inde qui est l’épicentre suprême. Cette idée de l’Inde est une grande indidée qui à l’évidence nous liait, car oui, cher Jean Parvulesco, vue sur la carte du Prêtre Jean, l’Europe est un petit cap de l’Asie : Kiptchak/Jagataï/Ilcnan/Jüan !

Dans une autre lettre sur papier à en tête du Groupement Géopolitique pour la plus Grande Inde daté du 31/XII-2008 « Pourriez-vous me faire parvenir une carte-photo de Babaji, il me semble qu’une relation médiumnique vient de s’établir entre lui et moi. »

Le natif Michaëlien de Lisieux en l’année 1929, je n’avais aucune peine à imaginer qu’il parvînt à nouer un lien de cette nature avec un Avatar Immortel Himalayen dont je lui avais juste envoyé une image, attendu déjà la nature psychique et onirique constituant la presque totalité du lien entre nous, fors presque toute relation personnelle et mondaine, sociale.

La nuit du 20 au 21 Octobre dernier, car il m’arrive de ne pas écrire la nuit, mais alors je rêve et je dois écrire ces rêves, j’ai rêvé que j’étais dans un restaurant, dans un salon, face à une femme aux yeux et au teint clairs portant de grands cheveux blonds. Elle me parle de choses secrètes, intimement. Je sais dans ce rêve que cette femme est un personnage de Jean Parvulesco.

Je lui aurais écrit ce rêve, au « prêtre Jean », s’il était encore de ce monde. Il se dégage d’elle une émanation directe du coeur, comme un Amour totalement étranger à ce monde, mais augurant d’un possible.

Je me suis demandé si cette femme était l’Europe. Alors je demande au matin à mon épouse si elle a fait un rêve complémentaire au mien que je tais. Elle me raconte… (nous sommes habitués à cette méthode d’instruction). Tout s’éclaire. Elle a rêvé d’une femme du temps de Louis XI, etc. La morale de son rêve se résume par « L’avenir du monde se joue dans une alcôve. » Je lui ai lu avant le coucher un tiers du poème Le Sarcophage du Soleil, auquel elle n’a rien compris, elle n’a jamais de sa vie lu la traître ligne des livres de Jean Parvulesco, elle ne sait pratiquement pas de quoi il est question. Certes, la femme de mon rêve ne m’avait pas invité à la rejoindre dans une baignoire, mais je la crois la même que la Benvenita du poème de Jean Parvulesco. J’ai une bonne raison pour cela. Deux jours avant, j’entre dans un vestiaire de salle de sport où j’enseigne le yoga et je découvre éberlué une phrase écrite au feutre vert sur un tableau blanc jamais utilisé ou presque, depuis 15 ans, surtout de cette façon : « Bienvenue Vermine ! »

La réalité dérape, et quand viendront les grandes neiges, on m’enverra aussi l’épouse des hauteurs, la Benvenita, nue sous sa tunique de scintillante haleine blanche, la pourvoyeuse d’être.

Parlant du retour au principe chez Hölderlin, Jean Parvulesco voit la preuve d’une identification avec l’Allemagne éternelle son image pré ontologique, pour le poète libéré de son moi, là où la Garonne s’identifiait avec le Rhin, avec l’Oxus, avec l’Indus avec la rivière éternelle de l’être. Toute vison totale est une pré-vision d’éternité. Elle résulte de l’expérience du sacré car comment des fleuves pourraient-ils sortir de leurs lits pour se fondre en une même eau, alors que la rivière du devenir n’est jamais la même, quand les philosophes se baignent au même fleuve qu’Héraclite l’obscur ? Mon maître indien Sri Premananda du Sri Lanka, nous a enseigné que lorsque nous sacralisons l’eau dans un rituel traditionnel, cette eau est, est effectivement, l’eau du Gange, de la Yamuna de la Kauvery. Les trois fleuves sacrés de l’Inde. Celui qui sait toucher l’eau touche toute l’eau. Notre Graal Eurasien peut nous être offert dans une telle immaculée donation.

Parlant du retour au principe chez Hölderlin, Jean Parvulesco voit la preuve d’une identification avec l’Allemagne éternelle son image pré ontologique, pour le poète libéré de son moi, là où la Garonne s’identifiait avec le Rhin, avec l’Oxus, avec l’Indus avec la rivière éternelle de l’être. Toute vison totale est une pré-vision d’éternité. Elle résulte de l’expérience du sacré car comment des fleuves pourraient-ils sortir de leurs lits pour se fondre en une même eau, alors que la rivière du devenir n’est jamais la même, quand les philosophes se baignent au même fleuve qu’Héraclite l’obscur ? Mon maître indien Sri Premananda du Sri Lanka, nous a enseigné que lorsque nous sacralisons l’eau dans un rituel traditionnel, cette eau est, est effectivement, l’eau du Gange, de la Yamuna de la Kauvery. Les trois fleuves sacrés de l’Inde. Celui qui sait toucher l’eau touche toute l’eau. Notre Graal Eurasien peut nous être offert dans une telle immaculée donation.

Elle est pré-vue, pré-dite, non pré-historique puisque préontologique, elle n’est qu’à la fin de l’Histoire, elle est le chuchotement d’un mot de passe entre deux Maha Yugas que nous donne l’oiseau Kalki en son roucoulement, parole retrouvée de l’Inde antérieure et que seule possède l’Inde Intérieure, Inern India, l’Abgrund intransitif d’avant l’origine même du temps.

Alors de quelle réparation de l’Histoire pourrions nous rêver si ce pouvoir nous était donné ? Qui est la chienne verte de Proserpine assassinée à l’Escurial, et quel sort aurait été changé par sa survie ? Charles Quint le disputant à Apollon, puisque le soleil sur son Empire ne se couchait jamais, n’ayant plus à poursuivre Daphnée, pouvait-il s’abstenir de gaspiller la clémence dont dispose un Prince, ou de pécher par étourderie politique à l’endroit de Luther ? L’anniversaire m’oblige à y penser. Le pouvait-il avant que 100 000 morts ne surgissent sous les écrits furieux du théologien employés à déchirer, au lieu de réformer l’Eglise, et dont les partisans vont mettre en pièces l’Europe ? Charles V ne pouvait-il mieux distribuer sa clémence d’Empereur Chrétien en protégeant les 40 millions d’indiens massacrés au Mexique sous les yeux crevés de honte de Bartolomé de Las Casas ? Pour le Graal Eurasien, Apollon est un dieu noir, il n’est autre que Shiva : « Ainsi je l’ai vu, le Sarcophage du Soleil de Horia Damian comme une nébuleuse de feu liturgiquement embrasée au cœur d’une immense tempête de neige cosmique, pour célébrer la dormition philosophique de notre Christ Apollon à l’intérieur même de sa charogne virginale.» Cela m’avait été enseigné avec l’introduction du cahier Jean Parvulesco dont j’ai parlé au début : « Qu'enfin tombe sur nous la fulgurance d'Apollon la haute clarté du hors du temps, cette aurore perpétuelle qui, sitôt franchi le Portique Boréal, s'ouvre sur les perspectives ouvertes à perte de vue de la Tradition Primordiale.» (Portique Boréal. André Murcie, pour un Cahier Jean Parvulesco).

Partons de l’extrait d’un article de Luc Olivier d’Algange au sujet d’Apollon pour qui : « Apollon n'est pas seulement le dieu de la mesure et de l'harmonie, le dieu des proportions rassurantes et de l'ordre classique, le dieu de Versailles et du Roi-Soleil, c'est aussi le dieu dont l'éclair rend fou. La sculpturale exactitude apollinienne naît d'une intensité lumineuse qui n'est pas moins dangereuse que l'ivresse dionysiaque. Apollon et Dionysos ont des fidèles de rangs divers. Certains rendent à ces dieux des hommages qui ne sont pasdépourvus de banalité, d'autres haussent leur révérence au rang le plus haut. L'Apollon qui se réverbère dans les poèmes d’Hölderlin témoigne d'un ordre de grandeur inconnu jusqu'alors et depuis.»

Voilà ce que j’écrivis dernièrement au poète en réponse : « Mais déjà la majesté et le mystère des Apollon, dans la statuaire du Vatican, nous en disent bien plus long que la vison classique et universitaire. L'Apollon du Belvédère sauvé par le futur pape Jules II, est tout entier vivifié par sa victoire sur le Python.» Qui dirait d'une victoire sur le lézard qu'elle est moins shivaïte ? C’est une victoire que le héros devra pourtant expier ensuite, mais c'est un Dieu shiva tout autant que Dyonisos ! Et le musagète dans la salle des muses, en sa beauté juvénile pourrait nous faire chavirer dans quelque transe. D'ailleurs, joueur de cithare dorien, il n'hésite pas à tuer ceux qui le défient avec le chant ou un autre instrument. Phrygien (Linos, Sylène, Marsias) avant la réconciliation ultime avec les musiques joyeuses. Les fêtes de Thargénie se souviennent des criminels qui lui étaient sacrifiés. Médecin avant Asclépios, sous le nom d'Apollon Oulios, il n'a pouvoir sur la vie que parce qu'il a pouvoir sur la mort.

Sa statue sur l'Acropole a été édifiée selon Pausanias après la peste consécutive à la guerre du Péloponnèse. Il est le dieu qui donne la mort, la mort noble subite et violente, donc ses flèches égalent celles d'Artémis, son intervention dans les combats de l'Illiade, tête casquée, arc et lance à la main, font de lui un Dieu exterminateur, comme Krishna sur le champs de bataille de Kurukshetra. Cette mort donnée par le dieu est initiatique, le signe nous en est donné par le témoignage d'Hécube, reconnaissant devant le cadavre d'Hector le miracle d'Apollon dans ce visage resté visage. Tout comme un dieu Hindou, Apollon a un véhicule, le griffon et plus tard le cygne, sur lequel il réapparaît à Delphes et Delios au printemps, après son séjour hivernal hyperboréen, le cygne qui pour les ariens est la lumière, dans les Védas il est le soleil. Quant aux griffons ils disputent aux Arismaspes, selon Hérodote, l'or des contrées boréales de l'Europe septentrionale. Mais la mort du Python elle, est suivie d'une imprécation : « Pourris là maintenant où tu es… tu pourriras ici sous l'action de la terre noire et du brillant Hypérion !» Lycien, Dieu de la Lumière s'il n'est Hyperboréen, est transporté dieu à Patara et est aussi le dieu loup. Les réfugiés du déluge de Deucalion avaient, après avoir dévalé les pentes du Parnasse guidés par les loups, fondé la ville de Lycoréia. Au revers des médailles d'Argos la tête de loup alterne avec celle d'Apollon, sur l'autre face, et en ce pays, Apollon a envoyé un loup combattre un taureau. Mais Apollon Nomios est bien le tueur de loups… Alors qui est Apollon ? Est-ce qu'il est vraiment l'opposé de Dionysos ? Un ami indien, notre invité à qui nous avons offert du vin vendredi soir, nous disait : « Dionysos c'est certain, il est Shiva et il a apporté le vin à l'Europe via la Grèce ! » Et si dans l'une de ses mains le colosse de Délos, Apollon selon Pausanias et Plutarque, tient les trois Charites, ces divinités ont été rapprochées des Haritas du Veda, les juments attelées au char du soleil, rayons de l'astre naissant à l'Orient.

Je vais conclure avec ces vers du célèbre poème de Gérard de Nerval, Delfica :

Ils reviendront ces Dieux que tu pleures toujours !

Le temps va ramener l’ordre des anciens jours.

Ce n’est pas le temps mais la rupture Indo Européenne du temps qui ramène cet ordre, le sévère portique est bien dérangé « Cependant la sibylle au visage latin est endormie encore sous l’arc de Constantin et rien n’a dérangé le sévère portique. » puisque le souffle prophétique de Jean Parvulesco, Sibylle réveillée annonce (Les Mystères de la Villa Atlantis, p 381) : « Car un jour Apollon reviendra et ce sera pour toujours ! disait la dernière prophétie de la dernière Pythie de Delphe ».

OM NAMA SHIVAYA !

18:13 Publié dans Jean Parvulesco | Lien permanent | Commentaires (4) | Tags : jean parvulesco |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L'implication de la Turquie dans le conflit ukrainien va-t-elle conduire à l'intégration du Donbass par la Russie?

L'implication de la Turquie dans le conflit ukrainien va-t-elle conduire à l'intégration du Donbass par la Russie?

En décembre 2020, la Turquie et l'Ukraine ont passé un accord militaire concernant la production commune de drones de combat avec transfert de technologie. Et en attendant la mise en route de cette production, l'Ukraine se disait prête à acheter des drones Bayraktar TB2, ces mêmes drones qui ont fait la différence dans le conflit du Haut-Karabakh. Il semblerait, selon certains experts, que la Turquie ait été aidée par les Etats-Unis à prendre la "bonne décision", celle d'une implication active dans le conflit ukrainien, suite à des sanctions imposées à ses entreprises de production d'armes. Cette délicate incitation expliquerait certainement le prix de vente incroyablement bas. En février 2021, l'information tombe d'une vente de 6 drones de combat à l'armée ukrainienne à un prix 16 fois inférieur à celui du marché.

L'intensification de l'activité des forces armées ukrainiennes, en violation directe des Accords de Minsk, oblige effectivement à poser la question d'une reprise "finale" du conflit. De son côté, la Russie appelle les Occidentaux à dissuader l'Ukraine de se lancer dans une folie guerrière, tout en soulignant que l'armée ukrainienne est soutenue, armée et entraînée par ces mêmes Occidentaux. Aucun conflit armé ne peut être contrôlé, il sort toujours des limites initialement prévues et entraîne des conséquences imprévisibles. Les Occidentaux ont-ils réellement envie de se battre pour l'Ukraine ? L'on peut sérieusement en douter. Mais s'ils laissent faire, comme ils le font actuellement, ils pourront être embarqués dans un conflit qui mettra à genoux une Europe, déjà triste fantôme d'elle-même.

La situation est ici extrêmement complexe (voir notre texte ici). Le Donbass n'est pas le Haut-Karabakh, en cas d'affrontement militaire, la Russie ne peut pas se permettre de rester en retrait. Certes moralement, comme le déclare Kourguiniane, la question du choix entre les néo-nazis de Kiev et les Russes et Ukrainiens du Donbass ne se pose pas : "Personne en Russie ne se permettrait de faire un autre choix, même s'il le voulait". Et le clan dit libéral, présent dans les organes de pouvoir, le voudrait fortement, espérant ainsi enfin entrer dans la danse occidentale, répétant à satiété le choix de 1991 et les erreurs qui l'ont accompagné.

Mais surtout, la situation est complexe sur le plan de la sécurité internationale, car la reprise dans le sang du Donbass par l'OTAN, sous drapeau turco-ukrainien, remettrait totalement en cause, au minimum, la stabilité sur le continent européen. Ce qui, in fine, servirait le fantasme globaliste.

D'un autre côté, la menace d'une intervention de la Russie, doublée d'une intégration du Donbass dans la Fédération de Russie, pourraient être le seul élément qui fasse réfléchir à deux fois avant de lancer les troupes. Car il y a une différence entre faire la guerre à LDNR et faire la guerre à la Russie.

Cette option de l'intégration avait longtemps été écartée par la Russie pour plusieurs raisons. Tout d'abord, le scénario de Crimée était unique et n'illustrait pas une vision expansionniste. Ensuite, la Russie n'avait pas la volonté de remettre en cause la stabilité internationale, ce que démontre ses appels incessants à exécuter les Accords de Minsk, qui inscrivent le Donbass dans le cadre de l'état ukrainien, soulignant que dans le cas contraire, l'Ukraine pourrait définitivement perdre le Donbass comme elle a perdu la Crimée. Enfin, car elle espérait, à terme, voir réintégrer l'Ukraine post-Maïdan au Donbass, c'est-à-dire pacifier l'Ukraine, la rendre à elle-même.

Or, la situation géopolitique a changé. L'intensification de la confrontation entre le clan atlantiste et la Russie modifie la donne sur de nombreux points. Si de toute manière des sanctions sont adoptées en chaîne contre la Russie, si de toute manière la rhétorique anti-russe continue à prendre de l'ampleur, si de toute manière les Atlantistes veulent faire de la Russie un état-terroriste, un paria, pourquoi alors ne pas réagir ? Les réactions asymétriques sont les plus efficaces et l'intégration du Donbass peut être l'une d'elles. Puisque de toute manière, avec ou sans lui, le combat entre dans une phase finale, une raison sera toujours trouvée (voir notre analyse ici) pour combattre la Russie, tant que l'obéissance ne sera pas totale, tant que la Russie ne se reniera pas sur la place publique.

Soit les globalistes n'ont plus le choix, ils doivent gagner ou périr, soit ils n'apprennent pas de leurs erreurs : le Maîdan, cette erreur de trop, qui a conduit à l'intégration de la Crimée, au retour de la Russie, décomplexée, sur la scène internationale, avec la Syrie ou le Venezuela. Dans tous les cas, la Russie a les cartes en main, elle aussi doit faire un choix stratégique, avec toutes les conséquences existentielles que cela implique.

00:16 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, géopolitique, turquie, ukraine, russie, crimée, donbass, mer noire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Salvini, Draghi et la Lega : l’Italie dans le “Great reset”

Salvini, Draghi et la Lega : l’Italie dans le “Great reset”

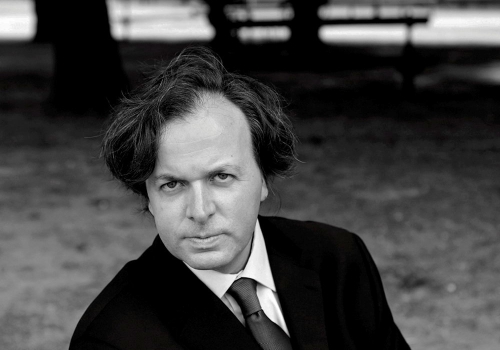

par Gabriele Adinolfi

Ex: https://strategika.fr

Gabriele Adinolfi est un théoricien politique italien. Il a dirigé la rédaction du journal Orion et lancé divers projets médiatiques et métapolitiques comme le site d’information NoReporter ou le think tank Centro Studi Polaris. Il a aussi parrainé en Italie les occupations illégales d’immeubles abandonnés à destination des familles italiennes démunies, occupations dont la plus connue est la Casapound (dont le nom fait référence à l’écrivain Ezra Pound) et qui est aujourd’hui un mouvement politique national. A partir de 2013 il anime un think tank basé à Bruxelles, EurHope. Les activités de Eurhope et de Polaris aboutissent au projet de l’Académie Europe (2020) qui relie des intellectuels, des activistes et des entrepreneurs de plusieurs pays. Le but de cette initiative est de créer une élite politique et entrepreneuriale apte à influer sur la politique européenne à l’échelle continentale. Dans le cadre de cette Académie Europe, il donne un cours de méthodologie politique en français tous les jeudis à 18h. Cours accessible en ligne ici.

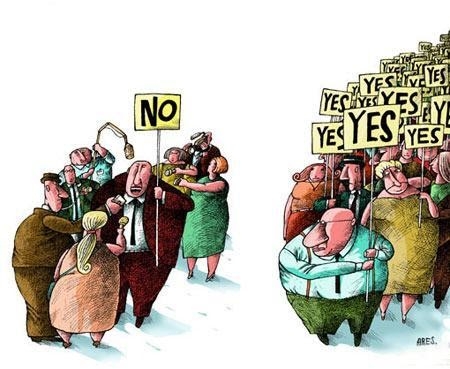

Pour déterminer si la Ligue a ou non trahi ses électeurs, le premier élément à considérer est leur sentiment. L’augmentation de consensus pour la Ligue, après le vote Draghi, a doublé par rapport à celle pour Fratelli d’Italia (Frères d’Italie) qui a choisi de rester en dehors du nouveau gouvernement.

Pourquoi le choix de la Ligue devrait-il être perçu comme une trahison ? Telle est la perception de ce qu’on appelle en sociologie les sous-cultures. Dans la communication moderne, des ghettos sociaux sont créés et à l’intérieur de ces ghettos sociaux certains utilisateurs s’influencent mutuellement, transformant la réalité des partis et des politiciens (Salvini, Trump, Poutine, Orban) à leur guise. Ils rejettent tout ce qui contredit leur vision et soulignent ce qui leur tient à cœur. Ils pensent ainsi que le succès de ces partis ou de ces politiciens est dû aux raisons que les utilisateurs des ghettos sociaux considèrent comme fondamentales et, quand la réalité fait tomber leur illusion, ils croient que les électeurs ont été trahis et qu’ils se retourneront contre les traîtres. Mais cela ne réside que dans la fausse perception de la réalité par les ghettos sociaux.

La Ligue, l’euro et l’Europe

La bataille de Salvini pour la sortie de l’euro a duré un an, de 2016 à 2017. Compte tenu de la façon dont cette ligne avait pénalisé Marine Le Pen à l’élection présidentielle, Salvini l’a brutalement abandonnée.

Il faut dire aussi que cette campagne démagogique a été lancée par une Ligue qui était à son plus bas résultat historique (4%), alors qu’elle était marginale et pouvait se permettre de dire ce qu’elle voulait.

Cependant, la Ligue est revenue pour gouverner les régions productives italiennes, pour représenter les industries, le tourisme, le commerce et là, si quelqu’un propose de quitter l’Euro, ils appellent directement une clinique psychiatrique.

Les ghettos sociaux n’ont pas compris cela car il y a encore trois ou quatre représentants de la Ligue qui jouent le no euro et les anti-allemands et, comme d’habitude, les utilisateurs sociaux confondent ceux qui viennent pêcher dans leur environnement avec l’ensemble du mouvement qui lui n’est pas du tout sur ces positions.

Il faut dire aussi que le souverainisme est suivie de près par les loges anglaises; loges qui veulent la faiblesse italienne et européenne, et donc soutiennent les lignes anti-euro.

Le personnage principal du parti de la City et de la Bourse proche de la Lega est Paolo Savona, qui fut l’un des architectes de la séparation entre la Banque d’Italie et le Trésor et l’un des porte-étendards des privatisations. Sa tâche n’est pas de nous sortir de l’euro, mais de saboter la puissance économique européenne. La pieuvre britannique du souverainisme en soutien au dollar et à la livre n’est pas dans la Ligue, elle opère à l’extérieur (Paragone, Giubilei, Fusaro). Au sein de la Ligue, le plus grand critique de l’euro et de l’Europe est Alberto Bagnai, l’homme qui célèbre publiquement le bombardement de Dresde. À un niveau beaucoup plus bas de la hiérarchie, il y a Borghi et Rinaldi, dont l’impact dans la Ligue et sur l’électorat de la Ligue est insignifiant mais qui sont imaginés par les ghettos sociaux comme dirigeants de la Ligue.

Draghi et les Italiens

Draghi a obtenu 86% des voix au Sénat et 89% des voix au Parlement.

Le consensus des Italiens pour Draghi est inférieur à celui exprimé par les partis, mais il est juste légèrement inférieur, car il approche des 80%.

Draghi est considéré comme l’homme qui a réussi à vaincre la ligne d’austérité de la Banque centrale et à aider l’économie italienne. Les Italiens qui continuent à être appelés eurosceptiques à l’étranger ne sont pas du tout eurosceptiques. Il est nécessaire de comprendre la mentalité italienne et l’expression comique de la politique.

En Italie, par tradition, l’État est quelque chose d’étranger à la vie quotidienne: on le maudit en payant des impôts mais on l’invoque pour l’aide économique et l’emploi.

C’est comme si vous aviez affaire à un grand-père qui se considère riche et de qui vous espérez obtenir quelque chose mais que vous êtes très réticent à rester auprès de lui.

Les chrétiens-démocrates avaient une majorité ininterrompue pendant cinquante ans, mais rencontrer alors quelqu’un qui prétendait voter pour DC était plus rare que de trouver un trèfle à quatre feuilles. Avec une mentalité syndicale, les Italiens ont tendance à critiquer ce qu’ils votent réellement, mais parce qu’ils croient qu’en faisant cela, leur soutien semblera décisif et qu’ils pourront exiger et obtenir plus de leur seigneur.

La relation avec l’UE de la part des Italiens est exactement la même. C’est un européanisme passif.

Depuis que Merkel a forcé les Européens à aider à restaurer l’économie italienne, les Italiens se font des illusions sur le fait qu’ils peuvent se remettre sur les épaules des autres et pensent que Draghi a l’autorité nécessaire pour que cela se produise à un coût limité.

Considérant aussi à quel point les deux gouvernements présidés par Conte se sont révélés amateurs, le consensus pour Draghi n’est inférieur, dans l’histoire italienne, qu’à celui de Mussolini.

L’Italie et la comédie

Chaque peuple a ses comédies et la démocratie est la comédie par excellence.

Aucune comédie n’est sérieuse. Mais les comédies sont différentes d’un pays à l’autre. En France, la tendance est à la vantardise, en Italie à être cabotin.

Le fanfaron doit respecter autant que possible le rôle qu’il joue, l’histrion change de rôle sans avoir de problèmes et joue un autre rôle à la seconde.

L’improbable unité italienne derrière Draghi est incompréhensible ailleurs. Salvini qui rencontre les dirigeants du Parti démocrate et qui s’apprête à gouverner avec eux. Salvini parlant avec le ministre de l’Intérieur qui a pris sa place contre lui et trace une ligne commune, Borghi inventant que Draghi est un “souverainiste”, sont des singeries qui ne seraient possibles nulle part ailleurs dans le monde mais qui en Italie sont très normales, comme les films de Sordi et Gassman l’enseignent.

La Ligue et Draghi

On ne sait pas exactement ce que Draghi essaiera de faire ni s’il réussira. J’espère pour ma part que cela échouera pour une raison simple : je crois qu’il faut maintenant la catastrophe la plus noire et la plus violente en Italie pour qu’il se produise un effet de choc qui puisse, peut-être, faire exister les vertus italiques chez quelqu’un parce qu’aujourd’hui l’Italie est, collectivement, une immense bouffonnade.

En tout cas, pour imaginer ce que Draghi tentera de faire, il faut abandonner tous les clichés en cours dans les ghettos sociaux. Draghi ne veut pas «liquider» l’Italie pour un méchant patron allemand ou français et ne veut pas la mettre en faillite. Au contraire, il veut rationaliser les dépenses, contrôler les revenus et relancer la production. Ce qui n’est pas du tout contraire à la soi-disant grande réinitialisation de Davos car, si vous lisez leurs documents préliminaires, ils sont préoccupés par la santé des entreprises productives; pour la simple raison que quiconque se nourrit du sang des autres, quand il meurt, doit lui donner des transfusions robustes.

Draghi n’est pas encore au travail mais certaines données s’éclaircissent. Le poids politique de la droite, et en particulier de Berlusconi, est très fort. Draghi veut se lancer dans un bras de fer avec l’État profond parasite italien et le choix de Brunetta comme ministre de l’administration publique le confirme. Trois ministères sont allés à la Ligue, dont deux revêtent une importance stratégique et pour l’économie et pour l’électorat de ce parti. Il s’agit du ministère du Tourisme, qui va à Massimo Garvaglia et du ministère du Développement économique qui va à Giancarlo Giorgetti, qui a grandi au MSI (note Strategika : Mouvement Social Italien, droite nationale post-fasciste).

Qu’elle gagne ou qu’elle perde, la Ligue a donc toutes les références pour bien jouer son jeu. Si ce match réussissait, la Ligue triompherait. Et si le jeu échoue ? Il ne se passerait pas grand-chose : elle jouerait ensuite un autre match. Le transformisme politique italien et la mentalité avec laquelle la comédie est vécue chez nous permettront tout autre nouveau saut périlleux. N’oublions pas que la Ligue a été à tour de rôle sécessionniste, autonomiste, souverainiste et européiste et que, changeant de masque, elle est toujours restée en selle. Tout simplement parce que elle est l’expression de territoires productifs et de classes sociales pénalisées par l’État profond et la bureaucratie. Par conséquent, elle risque peu ou rien dans son nouvel investissement.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, italie, europe, affaires européennes, politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 25 février 2021

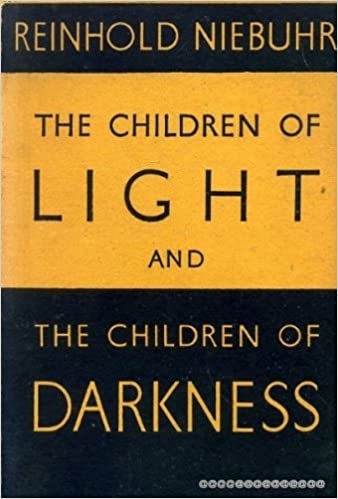

De la surdité culturelle qui caractérise l’Occident

De la surdité culturelle qui caractérise l’Occident

Les élites en viennent à croire leur propre récit – oubliant que celui-ci n’a été conçu que pour être une illusion faite pour capter l’imagination de leur population.

Par Alastair Crooke

Source Strategic Culture

Pat Buchanan a absolument raison : lorsqu’il s’agit d’insurrections, l’histoire dépend de celui qui écrit le récit. En général, c’est la classe oligarchique qui s’en charge (si elle finit par l’emporter). Pourtant, je me souviens d’un certain nombre de personne étiquetées « terroristes » qui sont finalement devenus des « hommes d’État » très connus. Ainsi tourne la roue de l’histoire, comme elle le fait encore.

Bien entendu, le fait de fixer un récit – une réalité incontestable, qui est perçue comme trop sûre, trop investie pour échouer – ne signifie pas qu’il n’est pas contesté. Il existe une vieille expression britannique qui décrit bien cette remise en question (silencieuse) du « récit » alors dominant (en Irlande et en Inde, entre autres). Elle était connue sous le nom d' »insolence muette ». Lorsque les actes individuels de rébellion étaient inutiles et trop coûteux sur le plan personnel, un silencieux et amère dédain, qui en disait long, exprimait cette « insolence muette » pour leurs « seigneurs et maîtres ». Elle rendait la classe dirigeante britannique furieuse car elle lui rappelait quotidiennement son déficit de légitimité. Gandhi a mené cette expression à son plus haut niveau. Et c’est finalement son récit qui est resté le plus mémorable dans l’histoire.

Cependant, avec le contrôle du récit par le Big Tech globalisé, nous sommes parvenus à un tout autre niveau que ces simples efforts britanniques pour nier la dissidence – comme le note succinctement le professeur Shoshana Zuboff de la Harvard Business School :

Au cours des deux dernières décennies, j’ai observé les conséquences de notre surprenante métamorphose en empires de surveillance alimentés par des architectures mondiales de surveillance, d’analyse, de ciblage et de prévision des comportements – que j’ai appelé le capitalisme de surveillance. En s’appuyant sur leurs capacités de surveillance et au nom du profit que leur apporte cette surveillance, les nouveaux empires ont organisé un coup d’État épistémique fondamentalement antidémocratique, marqué par des concentrations sans précédent de connaissances sur nous et le pouvoir sans limites qui en découle.

Mais le contrôle de la narrative a maintenant atteint un paroxysme :

C’est l’essence même du coup d’État épistémique. Ils revendiquent le pouvoir de décider qui sait … [et] qui va l’emporter, en tant que démocratie, sur les droits et principes fondamentaux qui définiront notre ordre social au cours de ce siècle. La reconnaissance croissante de cet autre coup d’État … nous obligera-t-elle enfin à tenir compte de la vérité dérangeante qui s’est profilée au cours des deux dernières décennies ? Nous avons peut-être une démocratie, ou nous avons peut-être une société de surveillance, mais nous ne pouvons pas avoir les deux.

Cela représente clairement une toute autre ampleur de « contrôle » – et lorsqu’il est allié aux techniques anti-insurrectionnelles occidentales de détournement du récit « terroriste », mises au point pendant la « Grande Guerre contre le terrorisme » – il constitue un outil formidable pour freiner la dissidence, tant au niveau national qu’international.

Mais il présente cependant une faiblesse fondamentale.

Tout simplement, quand à cause du fait d’être si investi, si immergé, dans une « réalité » particulière, les « vérités » des autres ne sont plus – ne peuvent plus – être entendues. Elles ne peuvent plus fièrement se distinguer au-dessus de la morne plaine du discours consensuel. Elles ne peuvent plus pénétrer dans la coquille durcie de la bulle narrative dominante, ni prétendre à l’attention d’élites si investies dans la gestion de leur propre version de la réalité.

La « faiblesse fondamentale » ? Les élites en viennent à croire leurs propres récits – oubliant que ce récit a été conçu comme une illusion, parmi d’autres, créée pour capter l’imagination au sein de leur société (et non celle des autres).

Elles perdent la capacité de se voir elles-mêmes, comme les autres les voient. Elles sont tellement enchantées par la vertu de leur version du monde qu’elles perdent toute capacité d’empathie ou d’acceptation de la vérité des autres. Elles ne peuvent plus capter les signaux. Le fait est que dans ce dialogue de sourds avec les autres États, les motifs et les intentions de ces derniers seront mal interprétés – parfois de manière tragique.

Les exemples sont légion, mais la perception de l’administration Biden selon laquelle le temps a été gelé – à partir du moment où Obama a quitté ses fonctions – et en quelque sorte dégelé le 20 janvier, juste à temps pour que Biden reprenne tout à cette époque antérieure (comme si ce temps intermédiaire n’existait pas), constitue un exemple de croyance en son propre mème. La stupéfaction – et la colère – de l’UE, qui a été décrite comme « un partenaire peu fiable » par Lavrov à Moscou, est un exemple de plus de l’éloignement des élites du monde réel et de leur captivité dans leur propre perception.

L’expression « l’Amérique est de retour » pour diriger et « fixer les règles du jeu » pour le reste du monde peut être destinée à faire rayonner la force des États-Unis, mais elle suggère plutôt une faible compréhension des réalités auxquelles les États-Unis sont confrontés : Les relations de l’Amérique avec l’Europe et l’Asie étaient de plus en plus distantes bien avant l’entrée de Biden à la Maison Blanche – mais aussi avant le mandat (volontairement perturbateur) de Trump.

Pourquoi alors les États-Unis sont-ils si systématiquement dans le déni à ce sujet ?

D’une part, après sept décennies de primauté mondiale, il existe inévitablement une certaine inertie qui empêcherait toute puissance dominante d’enregistrer et d’assimiler les changements importants du passé récent. D’autre part, pour les États-Unis, un autre facteur contribue à expliquer leur « oreille de sourd » : L’obsession de l’establishment au sens large d’empêcher l’élection présidentielle de 2020 de valider les résultats de la précédente. Cela a vraiment pris le pas sur tout le reste. Rien d’autre n’a d’importance. Leur obsession est si intense qu’elle les empêche de voir l’évolution du monde, pourtant juste là, devant leur nez.