Monika Berchvok s’entretient avec Robert Steuckers

Suite à la parution de Pages celtiques aux éditions du Lore et de la trilogie Europa aux éditions Bios de Lille, Monika Berchvok a soumis l'auteur de ces ouvrages, Robert Steuckers, à un feu roulant de questions, démontrant par là même que les rebelles de la jeune génération des années 2010 entendent connaître les racines les plus anciennes de cette sourde révolte qui est en train de s'amplifier dans toute l'Europe. Monika Berchvok avait déjà interrogé Robert Steuckers lors de la parution de La Révolution conservatrice allemande aux éditions du Lore en 2014 (cf. http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/archive/2014/07/26/r... )

Votre parcours est d'une extrême richesse intellectuelle. Quelle est l'origine de votre engagement ?

Parler de richesse intellectuelle est certainement exagéré : je suis surtout un homme de ma génération, à qui l’on a encore enseigné le « socle », aujourd’hui, hélas, disparu des curricula scolaires. J’ai vécu mon enfance et mon adolescence dans un monde qui était encore marqué par la tradition tranquille, les mœurs et les manières qui n’étaient pas celles du monde industriel ou du secteur tertiaire, où plus l’on s’éloigne du réel tangible et concret, plus on acquiert une prétention et une arrogance démesurées face aux « ploucs », comme moi, qui restent avec leurs lourdes godasses, ancrés dans la gadoue du réel (si, si, c’est du Heidegger…). Mon père, qui n’avait pas vraiment été à l’école, sinon à l’école primaire de son village limbourgeois, ne voulait rien entendre des modes et des manies qui agitaient nos contemporains dans les années 1960 et 1970 ; « tous des fafouls », clamait-il, « fafoul » étant un terme dialectal bruxellois pour désigner les zozos et les farfelus. J’ai vécu dans un foyer sans télévision, éloigné du et hostile au petit univers médiocre de la chansonnette, des variétés et de la sous-culture yéyé ou hippy. Je remercie encore mon géniteur, 25 ans après sa mort, d’avoir pu résister à toute la mièvre abjection de ces années où le déclin a avancé à pas de géant. Sans télévision, cela va sans dire, j’ai eu beaucoup de temps pour lire. Merci Papa.

Le 95 de la rue Berkendael aujourd'hui, la maison de mon enfance et de mon adolescence, où j'ai vécu de 1956 à 1978. C'est là que tout a commencé !

Ensuite, élève doué en primaire mais foncièrement fainéant et désespérément curieux, la seule bouée de sauvetage, pour ne pas finir clodo ou prolo, était l’apprentissage des langues à un bon niveau puisque, Bruxellois, je vivais dans une rue où l’on parlait les trois langues nationales (et leurs variantes dialectales), avec, en plus, le russe des quelques anciens officiers blancs et de leur enfants échoués en notre bonne ville. Avec cette pluralité linguistique, la tâche était dès lors à moitié mâchée. Clément Gstadler, un voisin, vieil instituteur alsacien, qui avait échoué en Belgique, me disait, coiffé de son éternel chapeau traditionnel du pays de Thann et avec un accent tudesque à couper au couteau : « Mon garçon, on est autant de fois homme que l’on connait de langues ». Fort de cette tirade martelée par Gstadler, je me suis donc inscrit, à dix-huit ans, en philologie germanique puis à l’école des traducteurs-interprètes.

L’origine de mon engagement est la volonté de rester fidèle à tous ces braves gens que l’on considèrerait aujourd’hui comme anachroniques. Sur leurs certitudes, battues en brèche, il fallait ériger un dispositif défensif, que l’on espérait toujours devenir un jour offensif, reposant sur des postulats diamétralement opposés aux hystéries des branchés, construire en nos cœurs une forteresse alternative, inexpugnable, que l’on était bien décidé à ne jamais rendre.

Comment définir votre combat métapolitique ?

Dilthey, que les alternatifs de notre genre ne connaissent hélas pas assez, a partiellement construit son système philosophique sur une idée fort simple : « on ne définit que ce qui est mort, que les choses et les faits dont le temps est définitivement achevé ». Ce combat n’est pas achevé puisque je ne suis pas encore passé de vie à trépas, sans doute pour contrarier ceux que ma rétivité déplait. Il est évident, qu’enfant des années 1950 et 1960, mes premières années de vie se sont déroulées à une époque où l’on voulait tout balancer aux orties. C’est bien entendu une gesticulation que je trouvais stupide et inacceptable.

Marcel Decorte: il a forgé le terme de "dissociété", plus actuel que jamais !

Rétrospectivement, je puis dire que je sentais bien, dans ma caboche de gamin, que la religion foutait le camp dès qu’elle avait renoncé et au latin et à l’esprit de croisade, très présent en Belgique, même chez des auteurs tranquilles, paisibles, comme un certain Marcel Lobet, totalement oublié aujourd’hui, sans doute à cause de la trop grande modération de ses propos, pourtant tonifiants au final pour ceux qui savaient les capter en leur sens profond. Le philosophe Marcel Decorte, à l’époque, constate que la société se délite et qu’elle va basculer dans la « dissociété », terme que l’on retrouve aujourd’hui, même dans certains cénacles de gauche, pour désigner l’état actuel de nos pays, laminés par les vagues successives de « négationnisme civilisationnel », telles le soixante-huitardisme, la nouvelle philosophie, le pandémonium néo-libéral ou le gendérisme, tous phénomènes « dissociaux », ou vecteurs de « dissocialité », qui convergent aujourd’hui dans l’imposture macroniste, mixte de tous ces funestes délires, sept décennies après l’ouverture de la Boîte de Pandore. Le combat métapolitique doit donc être un combat qui montre sans cesse la nature perverse de tous ces négationnismes civilisationnels et surtout qui dénonce continuellement les officines, généralement basées au-delà de l’Atlantique, qui les fabriquent pour affaiblir les sociétés européennes et pour créer une humanité nouvelle, totalement formatée selon des critères « dissociaux », négateurs du réel tel qu’il est (et qui ne peut être autrement, comme le remarquait un philosophe pertinent, Clément Rosset, malheureusement décédé au cours de ces dernières semaines). Pour énoncer une métaphore à la mode antique, je dirais qu’un combat métapolitique, dans notre sens, consiste, comme le disait l’européiste Thomas Ferrier de Radio Courtoisie, à ramener tous ces négationnismes dans la Boite de Pandore, dont ils ont jailli, puis de bien la refermer.

Vous évoquez dans vos récents travaux « le bio-conservatisme ». Que recouvre ce terme ?

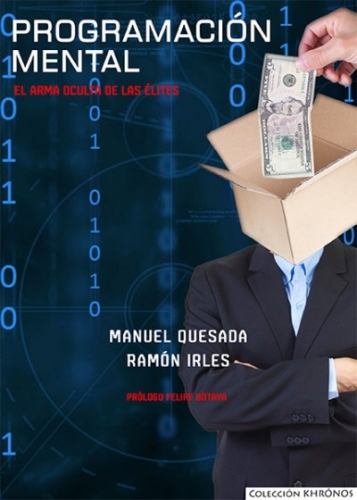

Je n’ai pas évoqué le « bio-conservatisme ». Mon éditeur, Laurent Hocq des Editions Bios, estime que c’est une piste qu’il va falloir explorer, justement pour combattre les « négationnismes civilisationnels », notamment tous les éléments qui nient la corporéité de l’homme, son inné phylogénétique et son ontologie. Pour moi, un bio-conservatisme bien conçu doit remonter à la sociologie implicite que Louis de Bonald esquissait au 19ème siècle, en critiquant les dérives individualistes des Lumières et de la révolution française. Le romantisme, dans ses dimensions qui ne sont ni éthérées ni larmoyantes, insiste sur l’organicité, vitaliste et biologique, des faits humains et sociaux. Il faut coupler ces deux filons philosophiques –le réalisme conservateur traditionnel et le romantisme organique- et les brancher ensuite sur les acquis plus récents et mieux étayés scientifiquement que sont la biocybernétique et la théorie des systèmes, tout en ne basculant pas dans une ingénierie sociale perverse comme le voulait l’Institut Tavistock, dont le « complotiste » David Estulin, aujourd’hui installé en Espagne, a investigué le rôle cardinal dans l’élaboration de toutes les formes de lavage de cerveau que nous subissons depuis plus d’une soixantaine d’années. Les « tavistockiens » avaient fait usage de la biocybernétique et de la théorie des systèmes pour imposer une culture « dépolitisante » à tout le monde occidental. Ces disciplines peuvent parfaitement être mobilisées, aujourd’hui, pour faire advenir une culture « re-politisée ». C’est ce travail de mobilisation métapolitique que Laurent Hocq veut amorcer avec moi. Il va falloir que je remobilise des personnes compétentes en ces domaines pour parfaire la tâche.

Je n’ai pas évoqué le « bio-conservatisme ». Mon éditeur, Laurent Hocq des Editions Bios, estime que c’est une piste qu’il va falloir explorer, justement pour combattre les « négationnismes civilisationnels », notamment tous les éléments qui nient la corporéité de l’homme, son inné phylogénétique et son ontologie. Pour moi, un bio-conservatisme bien conçu doit remonter à la sociologie implicite que Louis de Bonald esquissait au 19ème siècle, en critiquant les dérives individualistes des Lumières et de la révolution française. Le romantisme, dans ses dimensions qui ne sont ni éthérées ni larmoyantes, insiste sur l’organicité, vitaliste et biologique, des faits humains et sociaux. Il faut coupler ces deux filons philosophiques –le réalisme conservateur traditionnel et le romantisme organique- et les brancher ensuite sur les acquis plus récents et mieux étayés scientifiquement que sont la biocybernétique et la théorie des systèmes, tout en ne basculant pas dans une ingénierie sociale perverse comme le voulait l’Institut Tavistock, dont le « complotiste » David Estulin, aujourd’hui installé en Espagne, a investigué le rôle cardinal dans l’élaboration de toutes les formes de lavage de cerveau que nous subissons depuis plus d’une soixantaine d’années. Les « tavistockiens » avaient fait usage de la biocybernétique et de la théorie des systèmes pour imposer une culture « dépolitisante » à tout le monde occidental. Ces disciplines peuvent parfaitement être mobilisées, aujourd’hui, pour faire advenir une culture « re-politisée ». C’est ce travail de mobilisation métapolitique que Laurent Hocq veut amorcer avec moi. Il va falloir que je remobilise des personnes compétentes en ces domaines pour parfaire la tâche.

En bout de course, repenser un « bio-conservatisme », n’est ni plus ni moins une volonté de restaurer, le plus vite possible, une société « holiste » au meilleur sens du terme, c’est-à-dire une société qui se défend et s’immunise contre les hypertrophies fatidiques qui nous conduisent à la ruine, à la déchéance : hypertrophie économique, hypertrophie juridique (le pouvoir des juristes manipulateurs et sophistes), hypertrophie du secteur tertiaire, hypertrophie de la moraline désincarnée, etc.

Le localisme est aussi une thématique qui revient souvent dans vos derniers livres. Pour vous le retour au local a une dimension identitaire, mais aussi sociale et écologique ?

Le localisme ou les dimensions « vernaculaires » des sociétés humaines qui fonctionnent harmonieusement, selon des rythmes immémoriaux, sont plus que jamais nécessaires à l’heure où un géographe avisé comme Christophe Guilluy constate la déchéance de la « France d’en-bas », des merveilleuses petites villes provinciales qui se meurent devant nos yeux car elles n’offrent plus suffisamment d’emplois locaux et parce que leurs tissus industriels légers ont été délocalisés et dispersés aux quatre coins de la planète.

L’attention au localisme est une nécessité urgente, de nos jours, pour répondre à un mal terrifiant qu’a répandu le néo-libéralisme depuis l’accession de Thatcher au pouvoir en Grande-Bretagne et depuis toutes les politiques funestes que les imitateurs de cette « Dame de fer » ont cru bon d’importer en Europe et ailleurs dans le monde.

Le refus du « grand remplacement » migratoire passe par une compréhension des mouvements des immigrations à l'époque de la mondialisation totale. Comment renverser la tendance des flux migratoires ?

En ne les acceptant pas, tout simplement. Nous sommes une phalange de têtus et il faut impérativement que notre entêtement devienne contagieux, prenne les allures d’une pandémie planétaire.

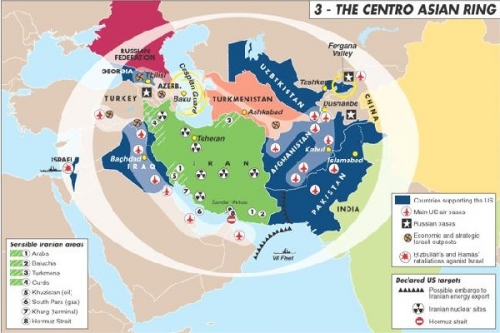

Cependant, quand vous évoquez le fait qu’il faille « une compréhension des mouvements des immigrations », vous soulignez indirectement la nécessité de connaître à fond les contextes dont ces migrants sont issus. Depuis un demi-siècle, et même plus car mai 68 a des antécédents dans les deux décennies qui l’ont précédé, nous sommes gavés d’une culture de pacotille, faite de variétés ineptes, qui occupent nos cerveaux à des spectacles chronophages et les empêchent de se concentrer sur des choses aussi réelles qu’essentielles. Un bon Etat est un Etat qui s’enquiert des forces à l’œuvre dans le monde. Que les flux migratoires soient acceptés ou non, tout Etat-hôte, animé par une vision saine des choses, devrait dresser une cartographie économique, ethnique et sociale des populations issues des pays d’émigration.

Pour l’Afrique, cela signifie connaître l’état de l’économie de chaque pays exportateur de migrants, l’éventuel système de kleptocratie qui y règne, les composantes ethniques (et les conflits et alliances qui en découlent), l’histoire de chacun de ces phénomènes politiques ou anthropologiques, etc. Ce savoir doit alors être livré par une presse honnête aux citoyens de nos pays, afin qu’ils puissent juger sur des pièces crédibles et non pas être entraînés à voter suite à une inlassable propagande assénée à satiété et reposant sur des slogans sans consistance.

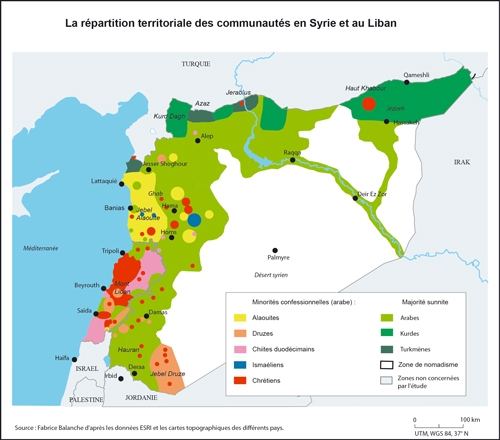

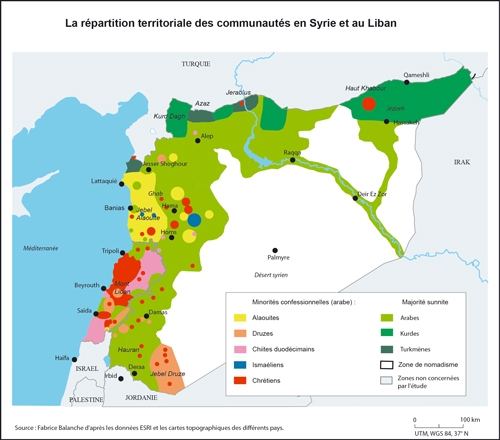

Pour la Syrie, il aurait fallu, avant que les flots de réfugiés ne se déversent en Europe, connaître de manière bien plus précise les structures religieuses et tribales du pays : en effet, les médias, généralement incultes et tributaires de la « culture de pacotille » imposée depuis des décennies, ont découvert des clivages syriens qu’ils avaient ignorés jusqu’alors. Une poignée seulement d’entre nous avait une notion claire de qui étaient les Alaouites ou les Yézidis, savait que les communautés chrétiennes syriennes étaient traversées par des clivages compliqués, connaissait l’alliance tacite qui unissait ces Alaouites aux Chiites duodécimains, comprenait que l’ennemi principal du système politique baathiste était les frères musulmans, déjà fauteurs des terribles désordres de 1981-1982 qui avaient ravagé la Syrie au temps d’Hafez el-Assad, père du Président actuel. Bref, le grand public ne savait rien de la complexité syrienne. Le seul os qu’il avait à ronger était le slogan qui décrétait qu’Assad était un horrible monstre, juste bon à être éliminé par des sicaires fondamentalistes ou des bombes américaines.

Pour l’Afrique, le seul moyen de réduire les flots de réfugiés, réels ou seulement économiques, aurait été de mettre un terme aux régimes manifestement trop kleptocratiques, de manière à pouvoir fixer les populations sur leur sol d’origine en infléchissant les sommes détournées vers des investissements infrastructurels. En certains cas bien précis, cela aurait aussi dû passer par un retour à une économie agricole vivrière et à un abandon partiel et bien régulé des monocultures qui ne parviennent pas à nourrir correctement les populations, surtout celles qui ont opté pour les exodes ruraux vers les villes et les bidonvilles tentaculaires, comme, par exemple, ceux du Nigéria.

Pour la Syrie, il aurait fallu établir un filtre pour trier les réfugiés mais cela aurait, ipso facto, privilégié les communautés musulmanes ou chrétiennes, alliés au régime, au détriment des strates qui lui sont hostiles et qui sont aussi nettement moins intégrables à nos sociétés européennes, puisque le salafisme qui les anime est viscéralement hostile à toutes les formes de syncrétismes et à toutes les cultures qui ne lui correspondent pas à 100%. En outre, en règle générale, la réception de flots migratoires en provenance de pays où sévissent de dangereuses mafias n’est nullement recommandable même si ces pays sont européens comme la Sicile, le Kosovo, l’Albanie ou certains pays du Caucase. Toute immigration devrait être passée au crible d’une grille d’analyse anthropologique bien établie et ne pas être laissée au pur hasard, à la merci d’une « main invisible » comme celle dont toutes les canules libérales attendent la perfection en ce bas monde. Le non discernement face aux flux migratoires a transformé cette constante de l’histoire humaine, dans ses manifestations actuelles, en une catastrophe aux répercussions imprévisibles car, à l’évidence, ces flux ne nous apporteront pas une société meilleure mais induiront un climat délétère de conflits inter-ethniques, de criminalité débridée et de guerre civile larvée.

Renverser la tendance des flux migratoires se fera quand on mettra enfin en œuvre un programme de triage des migrations, visant le renvoi des éléments criminels et mafieux, des déséquilibrés relevant de la psychiatrie (que l’on expédie délibérément chez nous, les infrastructures capables de les accueillir étant inexistantes dans leurs patries d’origine), des éléments politisés qui cherchent à importer des conflits politiques qui nous sont étrangers. Une telle politique sera d’autant plus difficile à traduire dans la réalité quotidienne que la masse importée de migrants sera trop importante. On ne pourra alors la gérer dans de bonnes conditions.

Vous avez connu Jean Thiriart. Sa vision politique d'une « Grande Europe » vous semble-t-elle encore actuelle ?

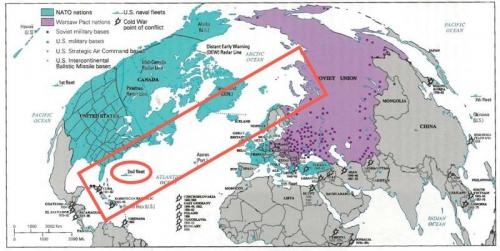

Jean Thiriart était d’abord, pour moi, un voisin, un homme qui vivait dans mon quartier. J’ai pu constater que derrière le sexagénaire costaud et bourru se cachait un cœur tendre mais meurtri de voir l’humanité basculer dans le ridicule, la trivialité et la veulerie. Je n’ai pas connu le Thiriart activiste puisque je n’avais que douze ans quand il a abandonné son combat politique à la fin des années 1960. Ce combat, qui s’est étendu sur une petite décennie à partir de l’abandon du Congo par la Belgique en 1960 et suite à l’épilogue tragique de la guerre d’Algérie pour les Français, deux ans plus tard. Thiriart était mu par une idée générale bien affirmée : abolir le duopole de Yalta, qui rendait l’Europe hémiplégique et impuissante, et renvoyer dos à dos Américains et Soviétiques pour que les Européens puissent se développer en toute indépendance. Il appartenait à une génération qui avait abordé la politique, très jeune, à la fin des années 1930 (émergence du rexisme, du Front Populaire, guerre d’Espagne, purges staliniennes, Anschluss, fin de la Tchécoslovaquie née à Versailles), a vécu la seconde guerre mondiale, la défaite de l’Axe, la naissance de l’Etat d’Israël, le coup de Prague et le blocus de Berlin en 1948, la Guerre de Corée et la fin du stalinisme.

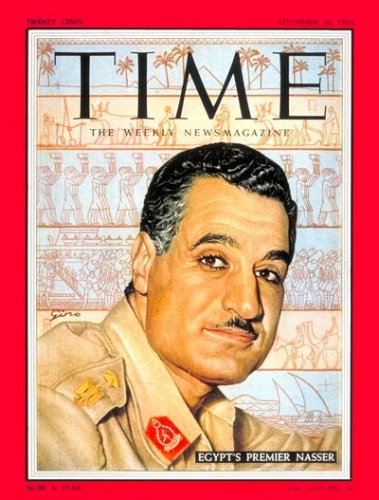

Deux événements ont certainement contribué à les ramener à un européisme indépendantiste, différent en ses sentiments de l’européisme professé par les idéologues de l’Axe : la révolte hongroise de 1956 et la campagne de Suez, la même année, celle de ma naissance (en janvier). L’Occident, soumis à Washington, n’a rien fait pour secourir les malheureux Hongrois. Pire, lors de l’affaire de Suez, les Américains et les Soviétiques imposent aux Français et aux Britanniques de se retirer inconditionnellement du théâtre opérationnel égyptien. Thiriart, et bon nombre de ses compagnons, temporaires ou non, constatent que le duopole n’a nulle envie de s’autodissoudre ni même de se combattre, de modifier dans un sens ou dans l’autre le tracé du Rideau de Fer qui mutile l’Europe en son beau milieu, de tolérer une affirmation géopolitique quelconque de la part de puissances européennes (fussent-elles membres du conseil de sécurité de l’ONU comme la France et le Royaume-Uni). La décolonisation du Congo a également montré que les Etats-Unis n’étaient nullement prêts à soutenir la présence belge en Afrique centrale, en dépit du fait que l’uranium congolais avait servi à asseoir la suprématie nucléaire de Washington depuis les bombes atomiques fabriquées pour mettre le Japon à genoux en 1945. L’abandon du Congo et surtout du Katanga ont créé une animosité anti-américaine en Belgique, vague sur laquelle va surfer Thiriart. Pour la petite histoire, le frère d’Hergé fut le seul militaire belge à ne pas se dégonfler et à manifester une hostilité arrogante aux militaires de l’ONU venus prendre le contrôle de sa base congolaise.

Une unité de chasseurs ardennais au Congo, 1960.

De fil en aiguille, Thiriart créera le fameux mouvement « Jeune Europe » qui injectera bien des innovations dans le discours d’un milieu activiste et contestataire de l’ordre établi que l’on pouvait classer au départ à l’extrême-droite dans ses formes conventionnelles, petites-nationalistes ou poujadistes. Les « habitus » de l’extrême-droite ne plaisaient pas du tout à Thiriart qui les jugeait improductifs et pathologiques. Lecteur des grands classiques de la politique réaliste, surtout Machiavel et Pareto, il a voulu créer une petite phalange hyper-politisée, raisonnant au départ de critères vraiment politiques et non plus d’affects filandreux, ne produisant que de l’indiscipline comportementale. Cet hyper-réalisme politique impliquait de penser en termes de géopolitique, d’avoir une connaissance de la géographie générale de la planète. Ce vœu s’est réalisé en Italie seulement, où la revue Eurasia de son disciple et admirateur Claudio Mutti est d’une tenue remarquable et a atteint un degré de scientificité très élevé.

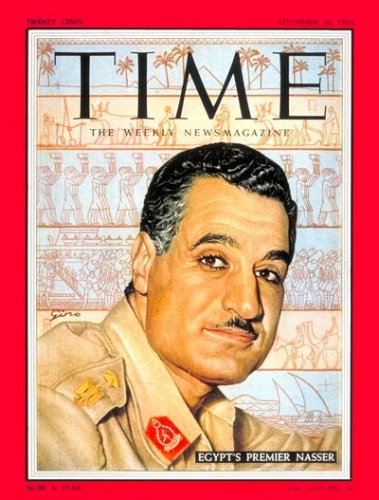

Pour contourner la césure de Yalta, Thiriart estimait qu’il fallait chercher des alliés de revers en Méditerranée et à l’Est de la vaste masse territoriale soviétique : d’où sa tentative de dialoguer avec des nationalistes nassériens arabes et avec les Chinois de Chou En Lai. La tentative arabe reposait sur une vision méditerranéenne précise, incomprise par les militants belges et très bien captée, au contraire, par ses disciples italiens : cette mer intérieure devait être dégagée de toute tutelle étrangère selon Thiriart. Il reprochait aux diverses formes de nationalismes en Belgique de ne pas comprendre les enjeux méditerranéens, ces formes étant davantage tournées vers l’Allemagne ou les Pays-Bas, l’Angleterre ou les pays scandinaves, tropisme « nordique » oblige. Son raisonnement sur la Méditerranée ressemblait à celui que Victor Barthélémy, adjoint de Doriot et lui aussi ancien communiste, mentionne comme le sien et celui de Mussolini dans ses mémoires. Thiriart dérivait très probablement sa vision de la géopolitique méditerranéenne d’un sentiment d’amertume suite à l’éviction de l’Angleterre et de la France hors de l’espace méditerranéen après l’affaire de Suez en 1956 et après la guerre d’Algérie.

Avec les Arabes, les Européens, selon Thiriart, partageaient un destin méditerranéen commun qui ne pouvait pas être oblitéré par les Américains et leurs pions sionistes. Même si les Français, les Anglais et les Italiens étaient chassés du littoral nord-africain arabophone, les nouveaux Etats arabes indépendants ne pouvaient renoncer à ce destin méditerranéen qu’ils partageaient avec les Européens non musulmans, massés sur la rive septentrionale. Pour Thiriart, les eaux de la Grande Bleue unifient et ne posent aucune césure. Il fallait, de ce fait, favoriser une politique de convergence entre les deux espaces civilisationnels, pour la défense de la Méditerranée contre l’élément étranger à cet espace, qui s’y immisçait et que constituait la flotte américaine commandée depuis Naples.

Avec les Arabes, les Européens, selon Thiriart, partageaient un destin méditerranéen commun qui ne pouvait pas être oblitéré par les Américains et leurs pions sionistes. Même si les Français, les Anglais et les Italiens étaient chassés du littoral nord-africain arabophone, les nouveaux Etats arabes indépendants ne pouvaient renoncer à ce destin méditerranéen qu’ils partageaient avec les Européens non musulmans, massés sur la rive septentrionale. Pour Thiriart, les eaux de la Grande Bleue unifient et ne posent aucune césure. Il fallait, de ce fait, favoriser une politique de convergence entre les deux espaces civilisationnels, pour la défense de la Méditerranée contre l’élément étranger à cet espace, qui s’y immisçait et que constituait la flotte américaine commandée depuis Naples.

L’idée de s’allier avec la Chine contre l’Union Soviétique visait à obliger celle-ci à lâcher du lest en Europe pour affronter les masses chinoises sur le front du fleuve Amour. Le double projet de parier sur les Arabes nassériens et sur les Chinois a marqué les dernières années de l’activité politique de Thiriart. Les années 1970 sont, pour lui, des années de silence ou plutôt des années où il s’immerge dans la défense de son créneau professionnel, à savoir l’optométrie. Quand il revient sur la brèche au début des années 1980, il est quasi oublié des plus jeunes et éclipsé par d’autres filons politiques et métapolitiques ; qui plus est, la donne a considérablement changé : les Américains ont fait alliance avec les Chinois en 1972 et, dès lors, ces derniers ne peuvent plus constituer un allié de revers. Comme d’autres, dans leur propre coin et sans concertation, tels Guido Giannettini et Jean Parvulesco, il élabore un projet euro-soviétique ou euro-russe que le régime d’Eltsine ne permettra pas de concrétiser. Il rencontre Alexandre Douguine en 1992, visite Moscou, rencontre des « rouges-bruns » mais meurt inopinément en novembre de la même année.

Ce qu’il faut retenir de Thiriart, c’est l’idée d’une école des cadres formées aux principes émis par la philosophie politique pure et à la géopolitique. Il faut aussi retenir l’idée d’une Europe comme espace géostratégique et militaire unique. C’est l’enseignement de la seconde guerre mondiale : la Westphalie se défend sur les plages de Normandie, la Bavière sur la Côte d’Azur et le cours du Rhône, Berlin à Koursk. Les moteurs ont permis le rétrécissement considérable de l’espace stratégique tout comme ils ont permis la Blitzkrieg de 1940 : avec un charroi hippomobile, aucune armée ne pouvait atteindre Paris depuis la Lorraine ou le Brabant. Les échecs de Philippe II après la bataille de Saint-Quentin le prouvent ; Götz von Berlichingen ne dépassera jamais Saint-Dizier ; les Prussiens et les Autrichiens ne dépassent pas Valmy et les armées du Kaiser sont arrêtées sur la Marne. Seule exception : l’entrée des alliés à Paris après la défaite de Napoléon à Leipzig. Les Etats-Unis sont désormais l’unique superpuissance, même si le développement d’armements nouveaux et l’hypertrophie impériale, qu’ils se sont imposée par démesure irréfléchie, battent lentement en brèche cette force militaire colossale, défiée récemment par les capacités nouvelles des missiles russes et peut-être chinois. L’indépendance européenne passe par une sorte de vaste front du refus, par une participation à d’autres synergies que celles voulues par Washington, comme le voulait aussi Armin Mohler. Ce refus érodera lentement mais sûrement la politique suprématiste des Américains et rendra finalement le monde « multipolaire ». La multipolarité est l’objectif à viser comme le voulait sans doute Thiriart mais aussi Armin Mohler et comme le veulent, à leur suite, Alexandre Douguine, Leonid Savin et votre serviteur.

Trois auteurs allemands semblent vous avoir particulièrement marqué : Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt et Günter Maschke. Que conservez-vous de leurs pensées ?

En fait, vous me demandez d’écrire un livre… J’admire les écrits politiques du jeune Jünger, rédigés au beau milieu des effervescences des années 1920 comme j’admire aussi ses récits de voyage, ses observations en apparence banales qui ont fait dire à quelques jüngeriens, exégètes de son œuvre, qu’il était un « Augenmensch », littéralement un « homme d’yeux », un homme qui arraisonne le monde de la nature et des formes (culturelles, architecturales, …) par le regard, par un regard pénétrant qui porte bien au-delà de la surface des choses vues et perçoit les règles et les rythmes de leur intériorité.

Je sortirai très bientôt un ouvrage copieux mais qui ne sera certainement pas exhaustif sur Carl Schmitt. Je tiens à rappeler ici que Carl Schmitt écrit ses premiers textes pertinents à l’âge de seize ans et couche sur le papier son dernier texte fondamental à 91 ans. Nous avons donc une œuvre colossale qui s’étend sur trois quarts de siècle. Carl Schmitt est le théoricien de beaucoup de choses mais on retient essentiellement de lui l’idée de décision et l’idée de « grand espace ». Mon ouvrage, à paraître aux éditions du Lore, montrera le rapport de Schmitt à l’Espagne, la nature très particulièrement de son catholicisme romain dans le contexte des débats qui ont animé le catholicisme allemand, son pari pour la Terre contre la Mer, etc.

Günter Maschke, sur le siège de son appartement d'où il émet ses réflexions puissantes sur la pensée de Carl Schmitt, d'où il récite par coeur les plus beaux poèmes de Gottfried Benn et d'où il brocarde tous les esprits impolitiques !

Parler de Günter Maschke m’intéresse davantage dans le cadre du présent entretien. J’ai connu Günter Maschke à la Foire du Livre de Francfort en 1984, puis lors d’un petit colloque organisé à Cologne en 1985 par des lycéens et des étudiants inféodés au Gesamtdeutscher Studentenverband, une association qui entendait chapeauter les organisations étudiantes qui, à l’époque, oeuvraient à la réunification du pays. Maschke est un ancien animateur tonitruant et pétulant des années activistes de 1967 et 1968 à Vienne, dont il sera expulsé pour violences de rue. Pour échapper à la prison en RFA, parce qu’il était déserteur, il réussira, via le collectif français « Socialisme ou Barbarie » à être discrètement exfiltré vers Paris d’abord, Cuba ensuite. Il s’installera dans la république insulaire et castriste des Caraïbes et y rencontrera Castro qui lui fit faire un tour de l’île pour lui montrer « ses » champs de canne à sucre et toutes « ses » propriétés agricoles. Maschke, qui ne peut tenir sa langue, lui a rétorqué : « Mais tu es le plus grand latifundiste d’Amérique latine ! ». Vexé, le lider maximo n’a pas reconduit son droit d’asile et Maschke s’est retrouvé à la case départ, c’est-à-dire dans une prison ouest-allemande pendant treize mois, le temps d’un service militaire refusé, comme le voulait la loi. En prison, il découvre Carl Schmitt et son disciple espagnol Donoso Cortès et, dans l’espace étroit de sa cellule, il trouve son chemin de Damas.

Beaucoup d’activistes de 67-68 en Allemagne tourneront d’ailleurs le dos aux idéologies qu’ils avaient professées ou instrumentalisées (sans trop y croire vraiment) dans leurs années de jeunesse : Rudi Dutschke était, au fond un nationaliste luthérien anti-américain ; ses frères ont donné des entretiens au journal néo-conservateur berlinois Junge Freiheit, et non à la presse gauchiste habituelle, celle qui répète les slogans d’hier sans se rendre compte qu’elle bascule dans l’anachronisme et le ridicule ; Frank Böckelmann, que Maschke m’a présenté lors d’une Foire du Livre, venait du situationnisme allemand et n’a plus cessé de fustiger ses anciens camarades dont l’antipatriotisme, dit-il, est l’indice d’une « fringale de limites », d’une volonté de s’autolimiter et de s’automutiler politiquement, de pratiquer l’ethno-masochisme. Klaus Rainer Röhl, aujourd’hui nonagénaire, fut l’époux d’Ulrike Meinhof, celle qui, avec Baader, sombrera dans le terrorisme. Röhl, lui aussi, se rapprochera des nationalistes alors que ce sont les articles d’Ulrike Meinhof dans sa revue konkret qui déclencheront les premières bagarres berlinoises lors de la venue du Shah d’Iran.

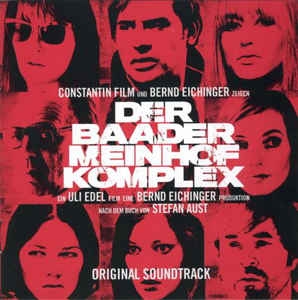

Le film d’Uli Edel consacré à la « Bande à Baader » (2008) montre aussi le glissement graduel du « complexe » terroriste en RFA, qui part d’un anti-impérialisme idéaliste et irraisonné, débridé et hystérique, mais parfois juste dans certaines de ses analyses, pour déboucher sur un terrorisme encore plus radical mais au service, finalement, de l’impérialisme américain : dans son film, Edel montre très clairement le jeu, notamment quand Baader, déjà arrêté et jugé, s’entretient avec le chef des services de police, et lui explique que la deuxième génération des terroristes n’obéit plus aux mêmes directives, surtout pas aux siennes. La deuxième génération des terroristes, alors que Meinhof, Baader et Ensslin (par ailleurs belle-sœur de Maschke !) étaient emprisonnés et non encore suicidés, assassine des hommes d’Etat ou des décisionnaires économiques qui voulaient justement mener des politiques en contradiction avec la volonté des Etats-Unis et émanciper la RFA de la tutelle pesante que Washington faisait peser sur elle. Ce glissement explique aussi l’attitude prise par Horst Mahler, avocat de Baader et partisan, en son temps, de la lutte armée. Lui aussi passera au nationalisme à sa sortie de prison, un nationalisme fortement teinté de luthérianisme, et retournera en prison pour « révisionnisme ». Aux dernières nouvelles, il y croupirait toujours.

Le film d’Uli Edel consacré à la « Bande à Baader » (2008) montre aussi le glissement graduel du « complexe » terroriste en RFA, qui part d’un anti-impérialisme idéaliste et irraisonné, débridé et hystérique, mais parfois juste dans certaines de ses analyses, pour déboucher sur un terrorisme encore plus radical mais au service, finalement, de l’impérialisme américain : dans son film, Edel montre très clairement le jeu, notamment quand Baader, déjà arrêté et jugé, s’entretient avec le chef des services de police, et lui explique que la deuxième génération des terroristes n’obéit plus aux mêmes directives, surtout pas aux siennes. La deuxième génération des terroristes, alors que Meinhof, Baader et Ensslin (par ailleurs belle-sœur de Maschke !) étaient emprisonnés et non encore suicidés, assassine des hommes d’Etat ou des décisionnaires économiques qui voulaient justement mener des politiques en contradiction avec la volonté des Etats-Unis et émanciper la RFA de la tutelle pesante que Washington faisait peser sur elle. Ce glissement explique aussi l’attitude prise par Horst Mahler, avocat de Baader et partisan, en son temps, de la lutte armée. Lui aussi passera au nationalisme à sa sortie de prison, un nationalisme fortement teinté de luthérianisme, et retournera en prison pour « révisionnisme ». Aux dernières nouvelles, il y croupirait toujours.

Au début des années 1980, Maschke est éditeur à Cologne et publie notamment des ouvrages de Carl Schmitt (La Terre et la Mer), de Mircea Eliade, de Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, d’Agnès Heller et de Régis Debray. Chaque année, en octobre quand se tenait la fameuse Foire du Livre de Francfort, Maschke, qui trouvait que j’avais une bonne bouille de jeune réac’ imperturbable, me faisait dresser par Sigi, son inoubliable épouse qui nous a quittés trop tôt, un lit de camp au beau milieu de son bureau prestigieux, où se trouvaient les plus beaux fleurons de sa bibliothèque. C’est ainsi que chaque année, de 1985 à 2003, j’ai fréquenté le « salon Maschke », où passaient des personnalités aussi prestigieuses que l’écrivain conservateur et catholique Martin Mosebach ou le philosophe grec du politique Panajotis Kondylis, l’ex-situ Franck Böckelmann ou le polémologue suisse Jean-Jacques Langendorf. Ces soirées étaient, je dois l’avouer, bien arrosées ; on y chantait et déclamait des poèmes (Maschke aime ceux de Gottfried Benn), la rigolade était de rigueur et les oreilles de bon nombre de sots et de prétentieux ont dû siffler tant ils ont été brocardés. J’ai hérité de Maschke un franc-parler, qui m’a souvent été reproché, et il a largement contribué à consolider en moi la verve moqueuse des Bruxellois, celle que je dois à mon oncle Joseph, le frère de ma mère, lanceur de bien verts sarcasmes.

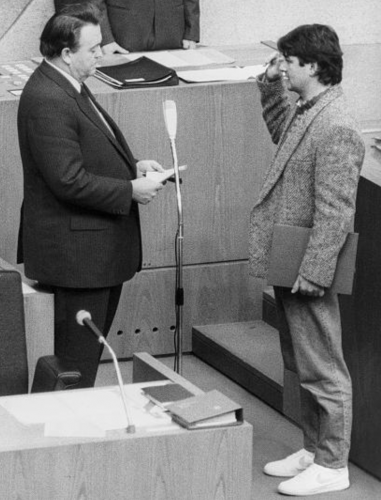

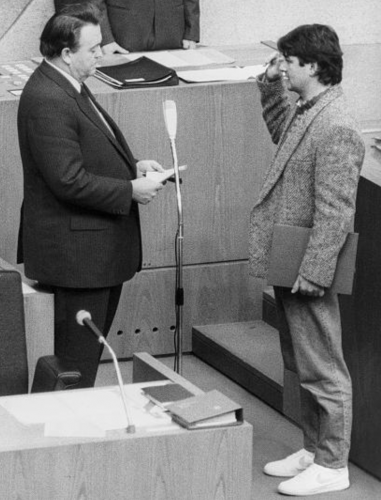

Sur la photo, Joshka Fischer, devenu ministre hessois, prête serment en baskets.

Je ne saurais clore ce paragraphe sans rappeler la rencontre fortuite entre Maschke et Joschka Fischer, l’année où ce dernier était devenu ministre du Land de Hesse, première étape qui le conduira à devenir le ministre allemand des affaires étrangères qui a fait participer son pays à la guerre contre la Serbie. Fischer déambulait dans les longs couloirs de la Foire du Livre. Maschke fond sur lui et s’en va lui tâter et pétrir le ventre, bien dodu, en lançant à la cantonade : « Eh bien, camarade Fischer, ça engraisse son homme de devenir ministre ». S’ensuivit une logorrhée de propos acerbes déversés sur le petit Fischer qui regardait ses baskets (son image de marque à l’époque, pour faire « cool ») et bafouillait des excuses qui n’en étaient pas. En le grondant comme s’il n’était qu’un sale mioche, Maschke lui prouvait que son néonationalisme à lui, schmittien, était dans la cohérence anti-impérialiste des années 67-68, tandis que l’alignement de Fischer en était la honteuse trahison. L’avenir lui donnera amplement raison : Fischer, ancien Krawallo violent du gauchisme hessois, deviendra un vil valet de l’impérialisme américain et capitaliste ; les propos dithyrambiques qu’il a prononcés ces dernières semaines pour faire l’éloge de la Chancelière Merkel ne font qu’accentuer cet amer sentiment de trahison. Ces remarques valent évidemment pour Daniel Cohn-Bendit, aujourd’hui belliciste à la solde de Washington. Jean-François Kahn, dans un entretien accordé très récemment à la Revue des deux mondes, parle de lui comme d’un soixante-huitard devenu néocon à la mode des anciens trotskistes de la Côte Est.

Je ne saurais clore ce paragraphe sans rappeler la rencontre fortuite entre Maschke et Joschka Fischer, l’année où ce dernier était devenu ministre du Land de Hesse, première étape qui le conduira à devenir le ministre allemand des affaires étrangères qui a fait participer son pays à la guerre contre la Serbie. Fischer déambulait dans les longs couloirs de la Foire du Livre. Maschke fond sur lui et s’en va lui tâter et pétrir le ventre, bien dodu, en lançant à la cantonade : « Eh bien, camarade Fischer, ça engraisse son homme de devenir ministre ». S’ensuivit une logorrhée de propos acerbes déversés sur le petit Fischer qui regardait ses baskets (son image de marque à l’époque, pour faire « cool ») et bafouillait des excuses qui n’en étaient pas. En le grondant comme s’il n’était qu’un sale mioche, Maschke lui prouvait que son néonationalisme à lui, schmittien, était dans la cohérence anti-impérialiste des années 67-68, tandis que l’alignement de Fischer en était la honteuse trahison. L’avenir lui donnera amplement raison : Fischer, ancien Krawallo violent du gauchisme hessois, deviendra un vil valet de l’impérialisme américain et capitaliste ; les propos dithyrambiques qu’il a prononcés ces dernières semaines pour faire l’éloge de la Chancelière Merkel ne font qu’accentuer cet amer sentiment de trahison. Ces remarques valent évidemment pour Daniel Cohn-Bendit, aujourd’hui belliciste à la solde de Washington. Jean-François Kahn, dans un entretien accordé très récemment à la Revue des deux mondes, parle de lui comme d’un soixante-huitard devenu néocon à la mode des anciens trotskistes de la Côte Est.

Photo: Gudrun Ensslin rejette son passé rigoriste protestant, tout comme le faisait le mouvement provo hollandais.

Dans sa quête après son retour de Cuba et son séjour dans un lugubre ergastule bavarois, Maschke, à la différence de Mahler par exemple ou de la famille de Dutschke, évoluera, avec Schmitt et Donoso, vers un catholicisme baroque et joyeux, fortement teinté d’hispanisme et rejettera la violence crispée, protestante et néo-anabaptiste qui avait si nettement marqué les révolutionnaires extra-parlementaires allemands des années 1960. Pour lui comme pour le cinéaste Edel, les sœurs Ensslin, par exemple, étaient excessivement marquées par l’éducation rigoriste et hypermoraliste, propre à leur milieu familial protestant, ce qui lui paraissait insupportable après son séjour à Cuba et ses voyages en Espagne. Aussi parce que Gudrun Ensslin basculait dans un goût morbide pour une sexualité débridée et promiscuitaire, résultat d’un rejet du puritanisme protestant que met bien en exergue le film d’Edel. La critique maschkienne de l’antichristianisme de la nouvelle droite (française) se résume, à son habitude, par quelques bons mots : ainsi, répétait-il, « ce sont des gars qui ont lu simultanément Nietzsche et Astérix puis, de ce mixte, ont fabriqué un système ». Pour lui, l’antichristianisme de Nietzsche était une hostilité aux rigueurs du protestantisme de la famille de pasteurs prussiens dont était issu le philosophe de Sils-Maria, attitude mentale qu’il est impossible de transposer en France, dont la tradition est catholique, Maschke ne prenant pas en compte la tradition janséniste.

Dans sa quête après son retour de Cuba et son séjour dans un lugubre ergastule bavarois, Maschke, à la différence de Mahler par exemple ou de la famille de Dutschke, évoluera, avec Schmitt et Donoso, vers un catholicisme baroque et joyeux, fortement teinté d’hispanisme et rejettera la violence crispée, protestante et néo-anabaptiste qui avait si nettement marqué les révolutionnaires extra-parlementaires allemands des années 1960. Pour lui comme pour le cinéaste Edel, les sœurs Ensslin, par exemple, étaient excessivement marquées par l’éducation rigoriste et hypermoraliste, propre à leur milieu familial protestant, ce qui lui paraissait insupportable après son séjour à Cuba et ses voyages en Espagne. Aussi parce que Gudrun Ensslin basculait dans un goût morbide pour une sexualité débridée et promiscuitaire, résultat d’un rejet du puritanisme protestant que met bien en exergue le film d’Edel. La critique maschkienne de l’antichristianisme de la nouvelle droite (française) se résume, à son habitude, par quelques bons mots : ainsi, répétait-il, « ce sont des gars qui ont lu simultanément Nietzsche et Astérix puis, de ce mixte, ont fabriqué un système ». Pour lui, l’antichristianisme de Nietzsche était une hostilité aux rigueurs du protestantisme de la famille de pasteurs prussiens dont était issu le philosophe de Sils-Maria, attitude mentale qu’il est impossible de transposer en France, dont la tradition est catholique, Maschke ne prenant pas en compte la tradition janséniste.

Ces anecdotes pour montrer que toute attitude politique doit retomber dans une sorte de réalisme aristotélicien.

Vous revenez dans votre livre, « Pages celtiques », sur l’apport du monde celte à notre civilisation continentale. Que gardons-nous de « gaulois » dans notre identité européenne ? Vous revenez sur le mouvement nationaliste irlandais et écossais longuement. Quelles leçons devons-nous tirer de leurs longues luttes ?

Dans Pages celtiques, j’ai voulu, pour l’essentiel, souligner trois choses : premièrement, la disparition de toutes les références culturelles et linguistiques celtiques est le résultat de la romanisation des Gaules ; cette romanisation fut apparemment rapide au sein des élites mais plus lente dans les sphères de la culture populaire, où elles ont résisté pendant cinq ou six siècles. La culture vernaculaire est restée de langue celtique jusqu’à l’arrivée des Germains, des Francs, qui prenaient le relais des Romains. On peut affirmer que la religiosité populaire est restée celle des « paysans éternels » (Mircea Eliade) et qu’elle est demeurée plus ou moins celle dont les Celtes pratiquaient les rituels. Cette religiosité de la glèbe est demeurée intacte sous le vernis chrétien, religion des élites seules au départ. Les dei loci, les dieux des lieux, sont tout simplement devenus des saints ou des madones, nichées dans les troncs des chênes ou placées aux carrefours ou près des sources. La « dé-celtisation », l’éradication de la religion des « paysans éternels », s’est opérée sous les coups de la modernité, avec la généralisation de la télévision et… avec Vatican II. Ce que les Français ont encore de « gaulois », a été mis en sommeil : c’est une jachère qui attend un réveil. Notre fond, en Belgique, a été, lui, profondément germanisé et romanisé, dans le sens où les Eburons, les Aduatuques et les Trévires étaient déjà partiellement germanisés du temps de César et où les tribus germaniques ingwéoniennes installées ultérieurement dans la vallée de la Meuse ont été au service de Rome et rapidement latinisées.

Statue de Colomban à Luxeuil-les-Bains.

Deuxièmement, l’apport celtique est également chrétien dans le sens où, à la fin de l’ère mérovingienne et au début de l’ère pippinide/carolingienne, les missions chrétiennes ne sont pas seulement téléguidées par Rome ; elles sont aussi irlando-écossaises avec Saint Colomban qui s’installe à Luxeuil-les-Bains, ancien site thermal gaulois puis romain. La Lorraine, l’Alsace, la Franche-Comté, la Suisse, le Wurtemberg, la Bavière, le Tyrol et une partie de l’Italie du Nord reçoivent le message chrétien non pas d’apôtres venus du Levant ou de missionnaires mandatés par Rome mais par des moines et des ascètes irlando-écossais qui proclament un christianisme plus proche de la religiosité naturelle des autochtones, avec quelques dimensions panthéistes, tout en préconisant le recopiage à grande échelle des manuscrits antiques, grecs et latins. Le syncrétisme chrétien, celtique et gréco-latin, qu’ils nous ont proposé, reste le fondement de notre culture européenne et toute tentative d’ôter ou d’éradiquer l’un de ces éléments serait une mutilation inutile voire perverse, qui déséquilibrerait en profondeur les assises de nos sociétés. Le moralisme béat et niais, propre à l’histoire récente de l’Eglise et à sa volonté de se « tiers-mondiser », a d’ailleurs ruiné toute la séduction que la religion pouvait exercer sur les masses populaires. Ne pas tenir compte du vernaculaire (celtique ou autre) et ne plus défendre à tout prix l’héritage des humanités classiques (avec la philosophie politique d’Aristote) ont éloigné et les masses et les élites intellectuelles et politiques de l’Eglise. Les paroisses ont perdu leurs ouailles : en effet, qu’avaient-elles à gagner à entendre répéter ad nauseam le prêchi-prêcha sans épaisseur qu’on leur propose désormais ?

Photo: statue du révolutionnaire irlandais Wolfe Tone à Dublin.

Troisièmement, au 18ième siècle, les Lumières politiques irlandaises, écossaises et galloises sont certes hostiles à l’absolutisme, réclament des formes nouvelles de démocratie, revendiquent une participation populaire aux choses publiques et appellent à un respect par les élites des cultures vernaculaires. Le républicanisme éclairé des Irlandais, Gallois et Ecossais, est hostile à la monarchie anglaise qui a soumis les peuples celtiques et le peuple écossais (mixte de Celtes, de Norvégiens et d’Anglo-Saxons libres) à un véritable processus de colonisation, particulièrement cruel, mais cette hostilité s’accompagne d’un culte très pieux voué aux productions culturelles du petit peuple. En Irlande, ce républicanisme n’est pas hostile au catholicisme foncier et contestataire des Irlandais ni aux multiples résidus du paganisme panthéiste que recèle naturellement et syncrétiquement ce catholicisme irlandais. Les représentants de cette religiosité ne sont pas traités de « fanatiques », de « superstitieux » ou de « brigands » par les élites républicaines. Ils ne sont pas voués aux gémonies ni traînés à la guillotine ou à la potence.

Troisièmement, au 18ième siècle, les Lumières politiques irlandaises, écossaises et galloises sont certes hostiles à l’absolutisme, réclament des formes nouvelles de démocratie, revendiquent une participation populaire aux choses publiques et appellent à un respect par les élites des cultures vernaculaires. Le républicanisme éclairé des Irlandais, Gallois et Ecossais, est hostile à la monarchie anglaise qui a soumis les peuples celtiques et le peuple écossais (mixte de Celtes, de Norvégiens et d’Anglo-Saxons libres) à un véritable processus de colonisation, particulièrement cruel, mais cette hostilité s’accompagne d’un culte très pieux voué aux productions culturelles du petit peuple. En Irlande, ce républicanisme n’est pas hostile au catholicisme foncier et contestataire des Irlandais ni aux multiples résidus du paganisme panthéiste que recèle naturellement et syncrétiquement ce catholicisme irlandais. Les représentants de cette religiosité ne sont pas traités de « fanatiques », de « superstitieux » ou de « brigands » par les élites républicaines. Ils ne sont pas voués aux gémonies ni traînés à la guillotine ou à la potence.

Les Lumières celtiques des Iles Britanniques ne renient pas les enracinements. Au contraire, elles les exaltent. La Bretagne, non républicaine, est victime, comme tout l’Ouest, d’une répression féroce par les « colonnes infernales ». Elle adhère dès lors en gros à l’ancien régime, en cultive la nostalgie, aussi parce qu’elle avait, à l’époque, un « Parlement de Bretagne » qui fonctionnait de manière optimale. L’oncle de Charles De Gaulle, le « Charles De Gaulle n°1 », sera le maitre d’œuvre d’une renaissance celtique en Bretagne au 19ième siècle, dans le cadre d’une idéologie monarchiste. A la même époque, les indépendantistes irlandais luttaient pour obtenir le « Home Rule » (l’autonomie administrative). Parmi eux, à la fin du 19ième siècle, il y avait Padraig Pearse qui créera un nationalisme mystique, alliant catholicisme anti-anglais et mythologie celtique. Il paiera de sa vie son engagement indéfectible : il sera fusillé suite au soulèvement de Pâques 1916. De même le chef syndicaliste James Connolly, mêlera marxisme syndicaliste et éléments libertaires de la mythologie irlandaise. Il partagera le sort tragique de Pearse.

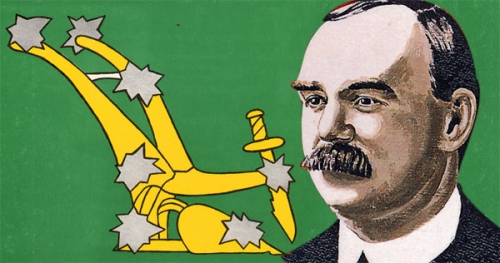

James Connolly.

Les leaders de l’Irlande indépendante offriront aux observateurs politiques de tous horizons un cocktail original de syndicalisme nationaliste, de celtisme mystique et de catholicisme social, où l’idéologie des droits de l’homme sera mobilisée contre les Britanniques non pas dans un sens individualiste, avec, pour référence, un homme détaché de tout lien social, de tout passé, donc avec un homme qui est posé comme une « apostasie sans nom du réel ». Au contraire, l’idéologie républicaine irlandaise raisonne au départ d’une vision de l’homme imbriqué dans un tout culturel, social et bio-ethnique. Ce tout doit alors aussi être l’objet d’une protection légale avec, pour corollaire, que toute atteinte, quelque part dans le monde, à l’un de ces ensembles ethno-socio-culturels est une atteinte à un droit fondamental de l’homme, celui d’appartenir à une culture. Les droits de l’homme sont donc, pour les Irlandais, indissociables des cultures qui animent et irriguent les sociétés humaines.

Après la seconde guerre mondiale, les Gallois prendront fait et cause pour les Bretons poursuivis par la République, qui sera condamnée par la Cour Internationale des Droits de l’Homme pour crime contre la culture bretonne : ce fait est bien évidemment oublié, parce qu’il a été sciemment occulté. Aujourd’hui, notamment à la suite des tirades péremptoires des « nouveaux philosophes », dont la trajectoire commence vers 1978 et se poursuit aujourd’hui, quarante ans plus tard ( !), avec les fulminations hystériques de Bernard-Henri Lévy, la République se veut la défenderesse par excellence des droits de l’homme : il est dès lors piquant et amusant de rappeler qu’elle a été condamnée sur plainte de Gallois et d’Irlandais pour crime contre une culture vernaculaire de l’Hexagone et que, par voie de conséquence, tout acte politique qui enfreindrait finalement les droits de la culture populaire ou contesterait à celle-ci le simple droit à l’existence et au déploiement, est également un crime passible d’une condamnation équivalente. Il existe donc d’autres interprétations et applications possibles des droits de l’homme que celle qui traite automatiquement d’arriéré et de fasciste potentiel toute personne se réclamant d’une identité charnelle. Les droits de l’homme sont ainsi parfaitement compatibles avec le droit de vivre une culture enracinée, spécifique et inaliénable, qui, finalement, a valeur sacrée, sur un sol qu’elle a littéralement pétri au fil des siècles. Hervé Juvin, par le biais d’une interprétation originale et politiquement pertinente des travaux ethnologiques et anthropologiques de Claude Lévi-Strauss et de Robert Jaulin, est celui qui nous indique le chemin à suivre aujourd’hui pour sortir de cette ambiance délétère, où nous sommes appelés à vouer une haine inextinguible envers ce que nous sommes au plus profond de nous-mêmes, à nous dépouiller de notre cœur profond pour nous vautrer dans le nihilisme de la consommation et du politiquement correct.

Je dois partiellement ce celtisme à la fois révolutionnaire et identitaire à l’activiste, sociologue et ethnologue allemand Henning Eichberg, théoricien et défenseur des identités partout dans le monde, qui avait exprimé un celtisme analogue dans un ouvrage militant et programmatique, paru au début des années 1980, au même moment où Olier Mordrel avait fait paraitre son Mythe de l’Hexagone. Mon ami Siegfried Bublies donnera d’ailleurs le titre de Wir Selbst à sa revue nationale-révolutionnaire non conformiste, traduction allemande du gaëlique Sinn Fein (= « Nous-Mêmes »). Bublies fut l’éditeur des textes polémiques et politiques d’Eichberg, décédé, hélas trop tôt, en avril 2017.

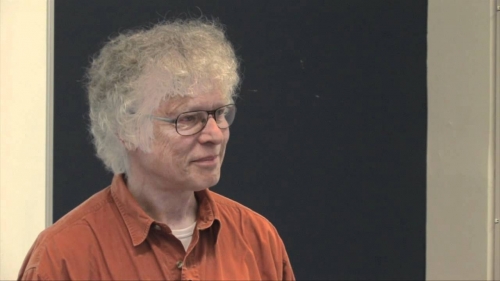

Henning Eichberg.

Dans Pages celtiques, j’ai également rendu hommage à Olier Mordrel, combattant breton, et défini la notion de patrie charnelle, tout en fustigeant les idéologies qui veulent l’éradiquer et la criminaliser.

Vous relancez des activités transeuropéennes. Comment jugez-vous l'évolution des forces « identitaires » en Europe ?

Non, je ne relance rien du tout. Je suis trop vieux. Il faut laisser la place aux jeunes, qui se débrouillent très bien selon des critères et des clivages propres à leur génération, selon des modes de communication que je ne maîtrise pas aussi bien qu’eux, tels les réseaux sociaux, les vidéos sur youtube, instagram, facebook ou autres. Ensuite, les instituts contestataires de la gabegie ambiante se multiplient à bon rythme car nous vivons une révolution conservatrice consolidée par rapport à ce qu’elle était, en jachère, il y a vingt ou trente ans. Il est vrai que les pouvoirs dominants n’ont pas tenu leurs promesses : des Trente Glorieuses, on est passé aux Trente Piteuses, selon l’écrivain suisse Alexandre Junod, que j’ai connu enfant et qui a si bien grandi... Et il est encore optimiste, ce garçon : s’il écrit encore un livre, il devra évoquer les « Trente Merdeuses ». Car on est tombé très très bas. C’est vraiment le Kali Yuga, comme disent les traditionalistes qui aiment méditer les textes hindous et védiques. Je me mets modestement au service des nouvelles initiatives. Les forces identitaires sont plurielles aujourd’hui mais les dénominateurs communs entre ces initiatives se multiplient, fort heureusement. Il faut travailler aux convergences et aux synergies (comme je l’ai toujours dit…). Mon éditeur Laurent Hocq s’est borné à annoncer trois colloques internationaux pour promouvoir nos livres à Lille, Paris et Rome. C’est tout. Pour ma part, je me bornerai à conseiller des initiatives comme les universités d’été de « Synergies européennes », même si elles étaient très théoriques, car elles permettent de se rencontrer et de moduler des stratégies fécondes pour les années à venir.

Pour commander la trilogie EUROPA aux éditions Bios: www.editionsbios.fr

Pour commander Pages celtiques et La révolution conservatrice allemande auprès des éditions du Lore : www.diffusiondulore.fr

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Je n’ai pas évoqué le « bio-conservatisme ». Mon éditeur, Laurent Hocq des Editions Bios, estime que c’est une piste qu’il va falloir explorer, justement pour combattre les « négationnismes civilisationnels », notamment tous les éléments qui nient la corporéité de l’homme, son inné phylogénétique et son ontologie. Pour moi, un bio-conservatisme bien conçu doit remonter à la sociologie implicite que Louis de Bonald esquissait au 19ème siècle, en critiquant les dérives individualistes des Lumières et de la révolution française. Le romantisme, dans ses dimensions qui ne sont ni éthérées ni larmoyantes, insiste sur l’organicité, vitaliste et biologique, des faits humains et sociaux. Il faut coupler ces deux filons philosophiques –le réalisme conservateur traditionnel et le romantisme organique- et les brancher ensuite sur les acquis plus récents et mieux étayés scientifiquement que sont la biocybernétique et la théorie des systèmes, tout en ne basculant pas dans une ingénierie sociale perverse comme le voulait l’Institut Tavistock, dont le « complotiste » David Estulin, aujourd’hui installé en Espagne, a investigué le rôle cardinal dans l’élaboration de toutes les formes de lavage de cerveau que nous subissons depuis plus d’une soixantaine d’années. Les « tavistockiens » avaient fait usage de la biocybernétique et de la théorie des systèmes pour imposer une culture « dépolitisante » à tout le monde occidental. Ces disciplines peuvent parfaitement être mobilisées, aujourd’hui, pour faire advenir une culture « re-politisée ». C’est ce travail de mobilisation métapolitique que Laurent Hocq veut amorcer avec moi. Il va falloir que je remobilise des personnes compétentes en ces domaines pour parfaire la tâche.

Je n’ai pas évoqué le « bio-conservatisme ». Mon éditeur, Laurent Hocq des Editions Bios, estime que c’est une piste qu’il va falloir explorer, justement pour combattre les « négationnismes civilisationnels », notamment tous les éléments qui nient la corporéité de l’homme, son inné phylogénétique et son ontologie. Pour moi, un bio-conservatisme bien conçu doit remonter à la sociologie implicite que Louis de Bonald esquissait au 19ème siècle, en critiquant les dérives individualistes des Lumières et de la révolution française. Le romantisme, dans ses dimensions qui ne sont ni éthérées ni larmoyantes, insiste sur l’organicité, vitaliste et biologique, des faits humains et sociaux. Il faut coupler ces deux filons philosophiques –le réalisme conservateur traditionnel et le romantisme organique- et les brancher ensuite sur les acquis plus récents et mieux étayés scientifiquement que sont la biocybernétique et la théorie des systèmes, tout en ne basculant pas dans une ingénierie sociale perverse comme le voulait l’Institut Tavistock, dont le « complotiste » David Estulin, aujourd’hui installé en Espagne, a investigué le rôle cardinal dans l’élaboration de toutes les formes de lavage de cerveau que nous subissons depuis plus d’une soixantaine d’années. Les « tavistockiens » avaient fait usage de la biocybernétique et de la théorie des systèmes pour imposer une culture « dépolitisante » à tout le monde occidental. Ces disciplines peuvent parfaitement être mobilisées, aujourd’hui, pour faire advenir une culture « re-politisée ». C’est ce travail de mobilisation métapolitique que Laurent Hocq veut amorcer avec moi. Il va falloir que je remobilise des personnes compétentes en ces domaines pour parfaire la tâche.

Avec les Arabes, les Européens, selon Thiriart, partageaient un destin méditerranéen commun qui ne pouvait pas être oblitéré par les Américains et leurs pions sionistes. Même si les Français, les Anglais et les Italiens étaient chassés du littoral nord-africain arabophone, les nouveaux Etats arabes indépendants ne pouvaient renoncer à ce destin méditerranéen qu’ils partageaient avec les Européens non musulmans, massés sur la rive septentrionale. Pour Thiriart, les eaux de la Grande Bleue unifient et ne posent aucune césure. Il fallait, de ce fait, favoriser une politique de convergence entre les deux espaces civilisationnels, pour la défense de la Méditerranée contre l’élément étranger à cet espace, qui s’y immisçait et que constituait la flotte américaine commandée depuis Naples.

Avec les Arabes, les Européens, selon Thiriart, partageaient un destin méditerranéen commun qui ne pouvait pas être oblitéré par les Américains et leurs pions sionistes. Même si les Français, les Anglais et les Italiens étaient chassés du littoral nord-africain arabophone, les nouveaux Etats arabes indépendants ne pouvaient renoncer à ce destin méditerranéen qu’ils partageaient avec les Européens non musulmans, massés sur la rive septentrionale. Pour Thiriart, les eaux de la Grande Bleue unifient et ne posent aucune césure. Il fallait, de ce fait, favoriser une politique de convergence entre les deux espaces civilisationnels, pour la défense de la Méditerranée contre l’élément étranger à cet espace, qui s’y immisçait et que constituait la flotte américaine commandée depuis Naples.

Le film d’Uli Edel consacré à la « Bande à Baader » (2008) montre aussi le glissement graduel du « complexe » terroriste en RFA, qui part d’un anti-impérialisme idéaliste et irraisonné, débridé et hystérique, mais parfois juste dans certaines de ses analyses, pour déboucher sur un terrorisme encore plus radical mais au service, finalement, de l’impérialisme américain : dans son film, Edel montre très clairement le jeu, notamment quand Baader, déjà arrêté et jugé, s’entretient avec le chef des services de police, et lui explique que la deuxième génération des terroristes n’obéit plus aux mêmes directives, surtout pas aux siennes. La deuxième génération des terroristes, alors que Meinhof, Baader et Ensslin (par ailleurs belle-sœur de Maschke !) étaient emprisonnés et non encore suicidés, assassine des hommes d’Etat ou des décisionnaires économiques qui voulaient justement mener des politiques en contradiction avec la volonté des Etats-Unis et émanciper la RFA de la tutelle pesante que Washington faisait peser sur elle. Ce glissement explique aussi l’attitude prise par Horst Mahler, avocat de Baader et partisan, en son temps, de la lutte armée. Lui aussi passera au nationalisme à sa sortie de prison, un nationalisme fortement teinté de luthérianisme, et retournera en prison pour « révisionnisme ». Aux dernières nouvelles, il y croupirait toujours.

Le film d’Uli Edel consacré à la « Bande à Baader » (2008) montre aussi le glissement graduel du « complexe » terroriste en RFA, qui part d’un anti-impérialisme idéaliste et irraisonné, débridé et hystérique, mais parfois juste dans certaines de ses analyses, pour déboucher sur un terrorisme encore plus radical mais au service, finalement, de l’impérialisme américain : dans son film, Edel montre très clairement le jeu, notamment quand Baader, déjà arrêté et jugé, s’entretient avec le chef des services de police, et lui explique que la deuxième génération des terroristes n’obéit plus aux mêmes directives, surtout pas aux siennes. La deuxième génération des terroristes, alors que Meinhof, Baader et Ensslin (par ailleurs belle-sœur de Maschke !) étaient emprisonnés et non encore suicidés, assassine des hommes d’Etat ou des décisionnaires économiques qui voulaient justement mener des politiques en contradiction avec la volonté des Etats-Unis et émanciper la RFA de la tutelle pesante que Washington faisait peser sur elle. Ce glissement explique aussi l’attitude prise par Horst Mahler, avocat de Baader et partisan, en son temps, de la lutte armée. Lui aussi passera au nationalisme à sa sortie de prison, un nationalisme fortement teinté de luthérianisme, et retournera en prison pour « révisionnisme ». Aux dernières nouvelles, il y croupirait toujours.  Je ne saurais clore ce paragraphe sans rappeler la rencontre fortuite entre Maschke et Joschka Fischer, l’année où ce dernier était devenu ministre du Land de Hesse, première étape qui le conduira à devenir le ministre allemand des affaires étrangères qui a fait participer son pays à la guerre contre la Serbie. Fischer déambulait dans les longs couloirs de la Foire du Livre. Maschke fond sur lui et s’en va lui tâter et pétrir le ventre, bien dodu, en lançant à la cantonade : « Eh bien, camarade Fischer, ça engraisse son homme de devenir ministre ». S’ensuivit une logorrhée de propos acerbes déversés sur le petit Fischer qui regardait ses baskets (son image de marque à l’époque, pour faire « cool ») et bafouillait des excuses qui n’en étaient pas. En le grondant comme s’il n’était qu’un sale mioche, Maschke lui prouvait que son néonationalisme à lui, schmittien, était dans la cohérence anti-impérialiste des années 67-68, tandis que l’alignement de Fischer en était la honteuse trahison. L’avenir lui donnera amplement raison : Fischer, ancien Krawallo violent du gauchisme hessois, deviendra un vil valet de l’impérialisme américain et capitaliste ; les propos dithyrambiques qu’il a prononcés ces dernières semaines pour faire l’éloge de la Chancelière Merkel ne font qu’accentuer cet amer sentiment de trahison. Ces remarques valent évidemment pour Daniel Cohn-Bendit, aujourd’hui belliciste à la solde de Washington. Jean-François Kahn, dans un entretien accordé très récemment à la Revue des deux mondes, parle de lui comme d’un soixante-huitard devenu néocon à la mode des anciens trotskistes de la Côte Est.

Je ne saurais clore ce paragraphe sans rappeler la rencontre fortuite entre Maschke et Joschka Fischer, l’année où ce dernier était devenu ministre du Land de Hesse, première étape qui le conduira à devenir le ministre allemand des affaires étrangères qui a fait participer son pays à la guerre contre la Serbie. Fischer déambulait dans les longs couloirs de la Foire du Livre. Maschke fond sur lui et s’en va lui tâter et pétrir le ventre, bien dodu, en lançant à la cantonade : « Eh bien, camarade Fischer, ça engraisse son homme de devenir ministre ». S’ensuivit une logorrhée de propos acerbes déversés sur le petit Fischer qui regardait ses baskets (son image de marque à l’époque, pour faire « cool ») et bafouillait des excuses qui n’en étaient pas. En le grondant comme s’il n’était qu’un sale mioche, Maschke lui prouvait que son néonationalisme à lui, schmittien, était dans la cohérence anti-impérialiste des années 67-68, tandis que l’alignement de Fischer en était la honteuse trahison. L’avenir lui donnera amplement raison : Fischer, ancien Krawallo violent du gauchisme hessois, deviendra un vil valet de l’impérialisme américain et capitaliste ; les propos dithyrambiques qu’il a prononcés ces dernières semaines pour faire l’éloge de la Chancelière Merkel ne font qu’accentuer cet amer sentiment de trahison. Ces remarques valent évidemment pour Daniel Cohn-Bendit, aujourd’hui belliciste à la solde de Washington. Jean-François Kahn, dans un entretien accordé très récemment à la Revue des deux mondes, parle de lui comme d’un soixante-huitard devenu néocon à la mode des anciens trotskistes de la Côte Est.  Dans sa quête après son retour de Cuba et son séjour dans un lugubre ergastule bavarois, Maschke, à la différence de Mahler par exemple ou de la famille de Dutschke, évoluera, avec Schmitt et Donoso, vers un catholicisme baroque et joyeux, fortement teinté d’hispanisme et rejettera la violence crispée, protestante et néo-anabaptiste qui avait si nettement marqué les révolutionnaires extra-parlementaires allemands des années 1960. Pour lui comme pour le cinéaste Edel, les sœurs Ensslin, par exemple, étaient excessivement marquées par l’éducation rigoriste et hypermoraliste, propre à leur milieu familial protestant, ce qui lui paraissait insupportable après son séjour à Cuba et ses voyages en Espagne. Aussi parce que Gudrun Ensslin basculait dans un goût morbide pour une sexualité débridée et promiscuitaire, résultat d’un rejet du puritanisme protestant que met bien en exergue le film d’Edel. La critique maschkienne de l’antichristianisme de la nouvelle droite (française) se résume, à son habitude, par quelques bons mots : ainsi, répétait-il, « ce sont des gars qui ont lu simultanément Nietzsche et Astérix puis, de ce mixte, ont fabriqué un système ». Pour lui, l’antichristianisme de Nietzsche était une hostilité aux rigueurs du protestantisme de la famille de pasteurs prussiens dont était issu le philosophe de Sils-Maria, attitude mentale qu’il est impossible de transposer en France, dont la tradition est catholique, Maschke ne prenant pas en compte la tradition janséniste.

Dans sa quête après son retour de Cuba et son séjour dans un lugubre ergastule bavarois, Maschke, à la différence de Mahler par exemple ou de la famille de Dutschke, évoluera, avec Schmitt et Donoso, vers un catholicisme baroque et joyeux, fortement teinté d’hispanisme et rejettera la violence crispée, protestante et néo-anabaptiste qui avait si nettement marqué les révolutionnaires extra-parlementaires allemands des années 1960. Pour lui comme pour le cinéaste Edel, les sœurs Ensslin, par exemple, étaient excessivement marquées par l’éducation rigoriste et hypermoraliste, propre à leur milieu familial protestant, ce qui lui paraissait insupportable après son séjour à Cuba et ses voyages en Espagne. Aussi parce que Gudrun Ensslin basculait dans un goût morbide pour une sexualité débridée et promiscuitaire, résultat d’un rejet du puritanisme protestant que met bien en exergue le film d’Edel. La critique maschkienne de l’antichristianisme de la nouvelle droite (française) se résume, à son habitude, par quelques bons mots : ainsi, répétait-il, « ce sont des gars qui ont lu simultanément Nietzsche et Astérix puis, de ce mixte, ont fabriqué un système ». Pour lui, l’antichristianisme de Nietzsche était une hostilité aux rigueurs du protestantisme de la famille de pasteurs prussiens dont était issu le philosophe de Sils-Maria, attitude mentale qu’il est impossible de transposer en France, dont la tradition est catholique, Maschke ne prenant pas en compte la tradition janséniste.

Troisièmement, au 18ième siècle, les Lumières politiques irlandaises, écossaises et galloises sont certes hostiles à l’absolutisme, réclament des formes nouvelles de démocratie, revendiquent une participation populaire aux choses publiques et appellent à un respect par les élites des cultures vernaculaires. Le républicanisme éclairé des Irlandais, Gallois et Ecossais, est hostile à la monarchie anglaise qui a soumis les peuples celtiques et le peuple écossais (mixte de Celtes, de Norvégiens et d’Anglo-Saxons libres) à un véritable processus de colonisation, particulièrement cruel, mais cette hostilité s’accompagne d’un culte très pieux voué aux productions culturelles du petit peuple. En Irlande, ce républicanisme n’est pas hostile au catholicisme foncier et contestataire des Irlandais ni aux multiples résidus du paganisme panthéiste que recèle naturellement et syncrétiquement ce catholicisme irlandais. Les représentants de cette religiosité ne sont pas traités de « fanatiques », de « superstitieux » ou de « brigands » par les élites républicaines. Ils ne sont pas voués aux gémonies ni traînés à la guillotine ou à la potence.

Troisièmement, au 18ième siècle, les Lumières politiques irlandaises, écossaises et galloises sont certes hostiles à l’absolutisme, réclament des formes nouvelles de démocratie, revendiquent une participation populaire aux choses publiques et appellent à un respect par les élites des cultures vernaculaires. Le républicanisme éclairé des Irlandais, Gallois et Ecossais, est hostile à la monarchie anglaise qui a soumis les peuples celtiques et le peuple écossais (mixte de Celtes, de Norvégiens et d’Anglo-Saxons libres) à un véritable processus de colonisation, particulièrement cruel, mais cette hostilité s’accompagne d’un culte très pieux voué aux productions culturelles du petit peuple. En Irlande, ce républicanisme n’est pas hostile au catholicisme foncier et contestataire des Irlandais ni aux multiples résidus du paganisme panthéiste que recèle naturellement et syncrétiquement ce catholicisme irlandais. Les représentants de cette religiosité ne sont pas traités de « fanatiques », de « superstitieux » ou de « brigands » par les élites républicaines. Ils ne sont pas voués aux gémonies ni traînés à la guillotine ou à la potence.

L’idéologie libérale-libertaire a pourtant délégitimé ce rôle du père en l’assignant au même rôle que celui de la mère, les deux étant désormais astreints à se nommer simplement parents, papa et maman et pourquoi pas parent 1 et parent 2. Jean-Pierre Lebrun va même plus loin en expliquant qu’il y a un « désaveu de la fonction paternelle pouvant mener jusqu’au triomphe de l’emprise maternante » [5]. Or la symétrie n’invite pas l’enfant à connaître l’altérité, la différence. Elle ne permet pas non plus à l’enfant de connaître l’absence et le manque de la mère car le père n’est plus l’étranger qui vient le retirer de sa relation fusionnelle avec elle. En assignant au père le même rôle qu’une mère, c’est-à-dire en lui retirant ce qui fait sa fonction initiale (l’intervention tierce, l’ouverture à l’altérité…) et en laissant s’installer une relation continue sans manque et pleine de jouissance entre l’enfant et la mère « on tend à provoquer l’annulation de tout manque, donc l’extinction de tout désir, du fait de l’empêchement de se déployer vers autre chose, vers un ailleurs que la présence maternelle » [6].

L’idéologie libérale-libertaire a pourtant délégitimé ce rôle du père en l’assignant au même rôle que celui de la mère, les deux étant désormais astreints à se nommer simplement parents, papa et maman et pourquoi pas parent 1 et parent 2. Jean-Pierre Lebrun va même plus loin en expliquant qu’il y a un « désaveu de la fonction paternelle pouvant mener jusqu’au triomphe de l’emprise maternante » [5]. Or la symétrie n’invite pas l’enfant à connaître l’altérité, la différence. Elle ne permet pas non plus à l’enfant de connaître l’absence et le manque de la mère car le père n’est plus l’étranger qui vient le retirer de sa relation fusionnelle avec elle. En assignant au père le même rôle qu’une mère, c’est-à-dire en lui retirant ce qui fait sa fonction initiale (l’intervention tierce, l’ouverture à l’altérité…) et en laissant s’installer une relation continue sans manque et pleine de jouissance entre l’enfant et la mère « on tend à provoquer l’annulation de tout manque, donc l’extinction de tout désir, du fait de l’empêchement de se déployer vers autre chose, vers un ailleurs que la présence maternelle » [6]. Aussi, ce qui caractérise la société libérale contemporaine est la permissivité des parents dans leur manière d’éduquer leur enfant. Christopher Lasch, dans son ouvrage La culture du narcissisme, faisait déjà état de ce constat relativement à la situation aux États-Unis lors des années 1970 en citant Arnold Rogow, un psychanalyste. Selon ce dernier, les parents « trouvent plus facile, pour se conformer à leur rôle, de soudoyer que de faire face au tumulte affectif que provoquerait la suppression des demandes des enfants ». Christopher Lash ajoute à son tour qu’ « en agissant ainsi, ils sapent les initiatives de l’enfant, et l’empêchent d’apprendre à se discipliner et à se contrôler ; mais étant donné que la société américaine n’accorde plus de valeur à ces traits de caractère, l’abdication par les parents de leur autorité favorise, chez les jeunes, l’éclosion des manières d’être que demande une culture hédoniste, permissive et corrompue. Le déclin de l’autorité parentale reflète « le déclin du surmoi » dans la société américaine dans son ensemble » [11].

Aussi, ce qui caractérise la société libérale contemporaine est la permissivité des parents dans leur manière d’éduquer leur enfant. Christopher Lasch, dans son ouvrage La culture du narcissisme, faisait déjà état de ce constat relativement à la situation aux États-Unis lors des années 1970 en citant Arnold Rogow, un psychanalyste. Selon ce dernier, les parents « trouvent plus facile, pour se conformer à leur rôle, de soudoyer que de faire face au tumulte affectif que provoquerait la suppression des demandes des enfants ». Christopher Lash ajoute à son tour qu’ « en agissant ainsi, ils sapent les initiatives de l’enfant, et l’empêchent d’apprendre à se discipliner et à se contrôler ; mais étant donné que la société américaine n’accorde plus de valeur à ces traits de caractère, l’abdication par les parents de leur autorité favorise, chez les jeunes, l’éclosion des manières d’être que demande une culture hédoniste, permissive et corrompue. Le déclin de l’autorité parentale reflète « le déclin du surmoi » dans la société américaine dans son ensemble » [11].  En France, actuellement, le souci de l’école d’accompagner les élèves dans leur développement personnel en favorisant leur créativité et non en les soumettant à l’autorité du professeur pour leur apprendre à maîtriser les savoirs essentiels est couplé avec le souci bourdieusien de ne pas reproduire les classes sociales. Néanmoins, c’est tout l’inverse qui se produit. Tout comme Christopher Lasch l’explique, « les réformateurs, malgré leurs bonnes intentions, astreignent les enfants pauvres à un enseignement médiocre, et contribuent ainsi à perpétuer les inégalités qu’ils cherchent à abolir » [13]. Effectivement, je me souviendrais toujours d’une professeur d’Histoire-Géographie dans le lycée où je travaillais en tant que surveillant à côté de mes études de droit qui, dans l’intention d’enseigner sa matière de manière ludique et attractive, basait principalement son cours sur la projection de films documentaires. Il se trouve que ce lycée, situé dans le quartier du Marais à Paris, était composé à la fois d’élèves provenant de l’immigration et d’une classe sociale défavorisée du 19ème arrondissement ainsi que d’élèves provenant d’une classe sociale aisée du 3ème arrondissement. Les élèves qui parvenaient le mieux à retenir avec précision le contenu des documentaires étaient sans surprise ceux du 3ème arrondissement tandis que les élèves qui avaient du mal à retenir le même contenu étaient ceux provenant du 19ème arrondissement. Pourtant, le fait de baser essentiellement son cours sur des films documentaires était une manière pour cette professeur d’échapper à un enseignement magistral qu’elle jugeait élitiste. Comme l’explique alors à nouveau Lasch, concernant l’école américaine avec laquelle on peut faire un parallèle avec l’école française actuelle, « au nom même de l’égalitarisme, ils [les réformateurs] préservent la forme la plus insidieuse de l’élitisme qui, sous un masque ou sous un autre, agit comme si les masses étaient incapables d’efforts intellectuels. En bref, tout le problème de l’éducation en Amérique pourrait se résumer ainsi : presque toute la société identifie l’excellence intellectuelle à l’élitisme. Cela revient à garantir à un petit nombre le monopole des avantages de l’éducation. Mais cette attitude avilit la qualité même de l’éducation de l’élite, et menace d’aboutir au règne de l’ignorance universelle » [14].