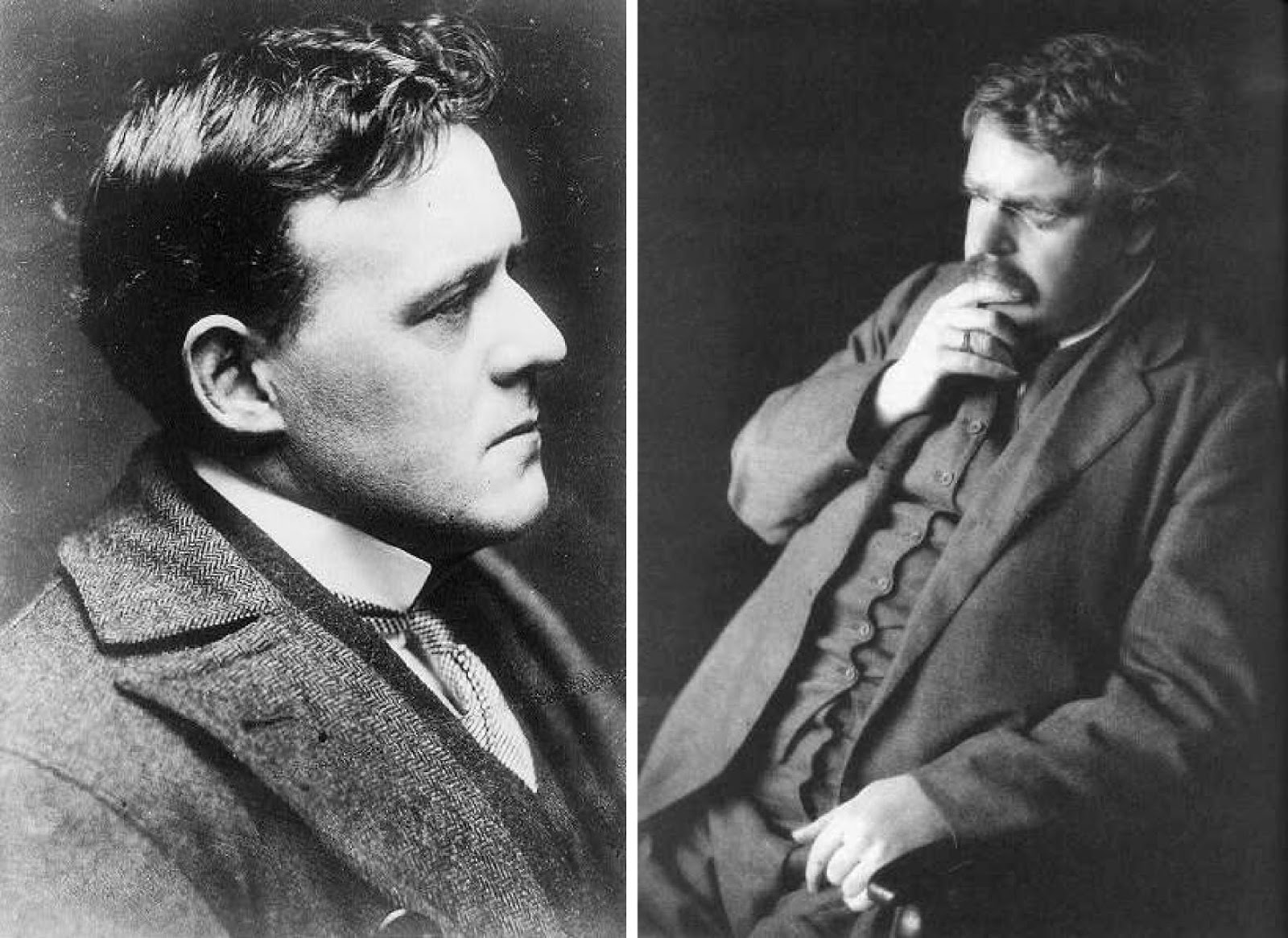

Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) gilt als einflussreichster und dennoch umstrittenster Verfassungsrechtler seiner Zeit.

Bei staatsrechtlichen Themen taucht immer wieder die Formel vom "fürchterlichen NS-Kronjuristen" Carl Schmitt auf, des führenden Staatsrechtlers der späten Weimarer Republik. Die damit eröffneten Nebenkriegsschauplätze verstellen die großartige, wissenschaftliche Leistung Schmitts. Sein Werk "Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus", welches 1923 veröffentlicht wurde, ist bis heute die beste Analyse des parlamentarischen Systems.

Darin geht Schmitt der Frage auf den Grund, warum es im 19. Jahrhundert zu der nicht zwangsläufigen Verquickung von Demokratie und Parlamentarismus als vermeintliche "ultimum sapientiae" (lat. absolute Weisheit) gekommen ist.

Unter den Liberalen des 19. Jahrhunderts herrschte die Vorstellung, dass die unterschiedlich im Volk verteilten Vernunftpartikel im Parlament zusammentreffen würden und sich dabei so in freier Konkurrenz zusammensetzen würden, dass am Ende das beste Ergebnis herauskäme. Das ist für Schmitt ein Ausdruck von liberal-ökonomischen Prinzipien (Glaube an die Kraft des freien Marktes), welcher durch die Realität ad absurdum geführt werde.

Das Parlament sei nicht das Forum, in dem die absolute Wahrheit oder Vernunft gesucht wird, sondern vielmehr würden in ihm bereits festgelegte Positionen und kaum veränderbare Partikularinteressen aufeinanderprallen. Es käme nicht darauf an, in gemeinsamen Beratungen die beste Lösung für das Allgemeinwohl zu finden, sondern nur darauf, die eigenen Interessen und die seiner Klientel durchzusetzen, indem man die nötigen Mehrheiten organisiert und über die Minderheit herrscht.[1]

Carl Schmitt (zeitweise auch Carl Schmitt-Dorotic)[2] (1888-1985) war ein deutscher Staatsrechtler[wp], der auch als politischer Philosoph rezipiert wird. Er ist einer der bekanntesten, wenn auch umstrittensten deutschen Staats- und Völkerrechtler des 20. Jahrhunderts. Als "Kronjurist des Dritten Reiches" (Waldemar Gurian[wp]) galt Schmitt nach 1945 als kompromittiert.

Sein im Katholizismus[wp] verwurzeltes Denken kreiste um Fragen der Macht[wp], der Gewalt und der Rechtsverwirklichung. Neben dem Staats- und Verfassungsrecht streifen seine Veröffentlichungen zahlreiche weitere Disziplinen wie Politikwissenschaft[wp], Soziologie, Theologie[wp], Germanistik[wp] und Philosophie[wp]. Sein breitgespanntes Œuvre umfasst außer juristischen und politischen Arbeiten verschiedene weitere Textgattungen, etwa Satiren, Reisenotizen, ideengeschichtliche Untersuchungen oder germanistische Textexegesen. Als Jurist prägte er eine Reihe von Begriffen und Konzepten, die in den wissenschaftlichen, politischen und sogar allgemeinen Sprachgebrauch eingegangen sind, etwa "Verfassungswirklichkeit"[wp], "Politische Theologie"[wp], "Freund-/Feind-Unterscheidung" oder "dilatorischer[wp] Formelkompromiss".

Sein im Katholizismus[wp] verwurzeltes Denken kreiste um Fragen der Macht[wp], der Gewalt und der Rechtsverwirklichung. Neben dem Staats- und Verfassungsrecht streifen seine Veröffentlichungen zahlreiche weitere Disziplinen wie Politikwissenschaft[wp], Soziologie, Theologie[wp], Germanistik[wp] und Philosophie[wp]. Sein breitgespanntes Œuvre umfasst außer juristischen und politischen Arbeiten verschiedene weitere Textgattungen, etwa Satiren, Reisenotizen, ideengeschichtliche Untersuchungen oder germanistische Textexegesen. Als Jurist prägte er eine Reihe von Begriffen und Konzepten, die in den wissenschaftlichen, politischen und sogar allgemeinen Sprachgebrauch eingegangen sind, etwa "Verfassungswirklichkeit"[wp], "Politische Theologie"[wp], "Freund-/Feind-Unterscheidung" oder "dilatorischer[wp] Formelkompromiss".

Schmitt wird heute zwar - vor allem wegen seines staatsrechtlichen Einsatzes für den Nationalsozialismus[wp] - als "furchtbarer Jurist"[wp], umstrittener Theoretiker und Gegner der liberalenDemokratie gescholten, zugleich aber auch als "Klassiker des politischen Denkens" (Herfried Münkler[wp][3]) gewürdigt - nicht zuletzt aufgrund seiner Wirkung auf das Staatsrecht und die Rechtswissenschaft[wp]der frühen Bundesrepublik[wp].[4]

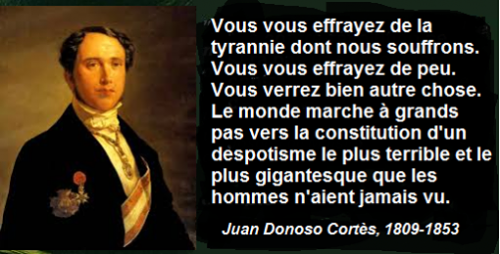

Die prägenden Einflüsse für sein Denken bezog Schmitt von politischen Philosophen und Staatsdenkern wie Thomas Hobbes[wp][5], Niccoló Machiavelli[wp], Aristoteles[wp][6], Jean-Jacques Rousseau[wp], Juan Donoso Cortés[wp] oder Zeitgenossen wie Georges Sorel[wp][7] und Vilfredo Pareto[wp].[8]

Veröffentlichungen und Überzeugungen

Schmitt wurde durch seine sprachmächtigen und schillernden Formulierungen auch unter Nichtjuristen schnell bekannt. Sein Stil war neu und galt in weit über das wissenschaftliche Milieu hinausgehenden Kreisen als spektakulär. Er schrieb nicht wie ein Jurist, sondern inszenierte seine Texte poetisch-dramatisch und versah sie mit mythischen Bildern und Anspielungen.[9]

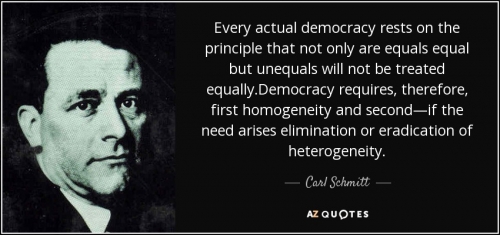

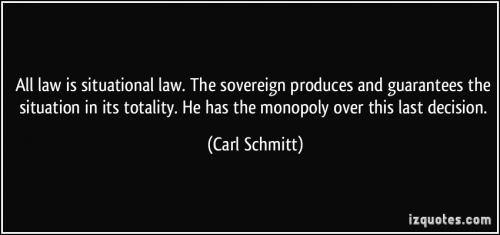

Seine Schriften waren überwiegend kleine Broschüren, die aber in ihrer thesenhaften Zuspitzung zur Auseinandersetzung zwangen. Schmitt war überzeugt, dass "oft schon der erste Satz über das Schicksal einer Veröffentlichung entscheidet".[10] Viele Eröffnungssätze seiner Veröffentlichungen - etwa: "Es gibt einen antirömischen Affekt", "Der Begriff des Staates setzt den Begriff des Politischen voraus" oder "Souverän[wp] ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand[wp] entscheidet" - wurden schnell berühmt.[11]

1924 erschien Schmitts erste explizit politische Schrift mit dem Titel Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus. Im Jahre 1928 legte er sein bedeutendstes wissenschaftliches Werk vor, die Verfassungslehre, in der er die Weimarer Verfassung einer systematischen juristischen Analyse unterzog und eine neue wissenschaftliche Literaturgattung begründete: neben der klassischen Staatslehre etablierte sich seitdem die Verfassungslehre[wp] als eigenständige Disziplin des Öffentlichen Rechts.

Ordnungspolitisch trat der ökonomisch informierte Jurist für einen starken Staat[wp] ein, der auf einer "freien Wirtschaft" basieren sollte. Hier traf sich Schmitts Vorstellung in vielen Punkten mit dem Ordoliberalismus[wp] oder späteren Neoliberalismus, zu deren Ideengebern er in dieser Zeit enge Kontakte unterhielt, insbesondere mit Alexander Rüstow[wp]. In einem Vortrag vor Industriellen im November 1932 mit dem Titel Starker Staat und gesunde Wirtschaft forderte er eine aktive "Entpolitisierung" des Staates und einen Rückzug aus "nichtstaatlichen Sphären":

- "Immer wieder zeigt sich dasselbe: nur ein starker Staat kann entpolitisieren, nur ein starker Staat kann offen und wirksam anordnen, daß gewisse Angelegenheiten, wie Verkehr oder Rundfunk, sein Regal sind und von ihm als solche verwaltet werden, daß andere Angelegenheiten der [...] wirtschaftlichen Selbstverwaltung zugehören, und alles übrige der freien Wirtschaft überlassen wird."[12]

Bei diesen Ausführungen spielte Schmitt auf einen Vortrag Rüstows an, den dieser zwei Monate zuvor unter dem Titel Freie Wirtschaft, starker Staat gehalten hatte.[13] Rüstow hatte sich darin seinerseits auf Carl Schmitt bezogen: "Die Erscheinung, die Carl Schmitt im Anschluß an Ernst Jünger den totalen Staat genannt hat [...], ist in Wahrheit das genaue Gegenteil davon: nicht Staatsallmacht, sondern Staatsohnmacht. Es ist ein Zeichen jämmerlichster Schwäche des Staates, einer Schwäche, die sich des vereinten Ansturms der Interessentenhaufen nicht mehr erwehren kann. Der Staat wird von den gierigen Interessenten auseinandergerissen. [...] Was sich hier abspielt, staatspolitisch noch unerträglicher als wirtschaftspolitisch, steht unter dem Motto: 'Der Staat als Beute'."[14]

Den so aufgefassten Egoismus gesellschaftlicher Interessensgruppen bezeichnete Schmitt (in negativer Auslegung des gleichnamigen Konzeptes von Harold Laski[wp]) als Pluralismus[wp]. Dem Pluralismus partikularer Interessen setzte er die Einheit des Staates entgegen, die für ihn durch den vom Volk gewählten Reichspräsidenten repräsentiert[wp] wurde.

In Berlin erschienen Der Begriff des Politischen (1928), Der Hüter der Verfassung (1931) und Legalität und Legitimität (1932). Mit Hans Kelsen[wp] lieferte sich Schmitt eine vielbeachtete Kontroverse über die Frage, ob der "Hüter der Verfassung" der Verfassungsgerichtshof oder der Reichspräsident sei.[15]Zugleich näherte er sich reaktionären[wp] Strömungen an, indem er Stellung gegen den Parlamentarismus[wp] bezog.

Als Hochschullehrer war Schmitt wegen seiner Kritik an der Weimarer Verfassung zunehmend umstritten. So wurde er etwa von den der Sozialdemokratie[wp] nahestehenden Staatsrechtlern Hans Kelsen[wp] und Hermann Heller[wp] scharf kritisiert. Die Weimarer Verfassung, so meinte Schmitt, schwäche den Staat durch einen "neutralisierenden" Liberalismus und sei somit nicht fähig, die Probleme der aufkeimenden "Massendemokratie"[wp] zu lösen.

Als Hochschullehrer war Schmitt wegen seiner Kritik an der Weimarer Verfassung zunehmend umstritten. So wurde er etwa von den der Sozialdemokratie[wp] nahestehenden Staatsrechtlern Hans Kelsen[wp] und Hermann Heller[wp] scharf kritisiert. Die Weimarer Verfassung, so meinte Schmitt, schwäche den Staat durch einen "neutralisierenden" Liberalismus und sei somit nicht fähig, die Probleme der aufkeimenden "Massendemokratie"[wp] zu lösen.

Liberalismus war für Schmitt im Anschluss an Cortés[wp] nichts anderes als organisierte Unentschiedenheit: "Sein Wesen ist Verhandeln, abwartende Halbheit, mit der Hoffnung, die definitive Auseinandersetzung, die blutige Entscheidungsschlacht könnte in eine parlamentarische Debatte verwandelt werden und ließe sich durch ewige Diskussion ewig suspendieren".[16] Das Parlament ist in dieser Perspektive der Hort der romantischen Idee eines "ewigen Gesprächs". Daraus folge: "Jener Liberalismus mit seinen Inkonsequenzen und Kompromissen lebt [...] nur in dem kurzen Interim, in dem es möglich ist, auf die Frage: Christus oder Barrabas, mit einem Vertagungsantrag oder der Einsetzung einer Untersuchungskommission zu antworten".[17]

Die Parlamentarische Demokratie[wp] hielt Schmitt für eine veraltete "bürgerliche" Regierungsmethode, die gegenüber den aufkommenden "vitalen Bewegungen" ihre Evidenz verloren habe. Der "relativen" Rationalität des Parlamentarismus trete der Irrationalismus[wp] mit einer neuartigen Mobilisierung der Massen gegenüber. Der Irrationalismus versuche gegenüber der ideologischen Abstraktheit und den "Scheinformen der liberal-bürgerlichen Regierungsmethoden" zum "konkret Existenziellen" zu gelangen. Dabei stütze er sich auf einen "Mythus vom vitalen Leben". Daher proklamierte Schmitt: "Diktatur ist der Gegensatz zu Diskussion".[18]

Als Vertreter des Irrationalismus identifizierte Schmitt zwei miteinander verfeindete Bewegungen: den revolutionären Syndikalismus[wp] der Arbeiterbewegung[wp] und den Nationalismus des italienischen Faschismus. Den italienischen Faschismus verwendete Schmitt als eine Folie, vor deren Hintergrund er die Herrschaftsformen des "alten Liberalismus" kritisierte. Dabei hatte er sich nie mit den realen Erscheinungsformen des Faschismus auseinandergesetzt. Sein Biograph Noack urteilt: "[Der] Faschismus wird von [Schmitt] als Beispiel eines autoritären Staates (im Gegensatz zu einem totalitären) interpretiert. Dabei macht er sich kaum die Mühe, die Realität dieses Staates hinter dessen Rhetorik aufzuspüren."[19]

Laut Schmitt bringt der Faschismus einen totalen Staat aus Stärke hervor, keinen totalen Staat aus Schwäche. Er ist kein "neutraler" Mittler zwischen den Interessensgruppen, kein "kapitalistischer Diener des Privateigentums", sondern ein "höherer Dritter zwischen den wirtschaftlichen Gegensätzen und Interessen". Dabei verzichte der Faschismus auf die "überlieferten Verfassungsklischees des 19. Jahrhunderts" und versuche eine Antwort auf die Anforderungen der modernen Massendemokratie zu geben.

- "Daß der Faschismus auf Wahlen verzichtet und den ganzen 'elezionismo haßt und verachtet, ist nicht etwa undemokratisch, sondern antiliberal und entspringt der richtigen Erkenntnis, daß die heutigen Methoden geheimer Einzelwahl alles Staatliche und Politische durch eine völlige Privatisierung gefährden, das Volk als Einheit ganz aus der Öffentlichkeit verdrängen (der Souverän verschwindet in der Wahlzelle) und die staatliche Willensbildung zu einer Summierung geheimer und privater Einzelwillen, das heißt in Wahrheit unkontrollierbarer Massenwünsche und -ressentiments herabwürdigen."

Gegen ihre desintegrierende Wirkung kann man sich Schmitt zufolge nur schützen, wenn man im Sinne von Rudolf Smends[wp] Integrationslehre eine Rechtspflicht des einzelnen Staatsbürgers konstruiert, bei der geheimen Stimmabgabe nicht sein privates Interesse, sondern das Wohl des Ganzen im Auge zu haben - angesichts der Wirklichkeit des sozialen und politischen Lebens sei dies aber ein schwacher und sehr problematischer Schutz. Schmitts Folgerung lautet:

- "Jene Gleichsetzung von Demokratie und geheimer Einzelwahl ist Liberalismus des 19. Jahrhunderts und nicht Demokratie." [20]

Nur zwei Staaten, das bolschewistische Russland und das faschistische Italien, hätten den Versuch gemacht, mit den überkommenen Verfassungsprinzipien des 19. Jahrhunderts zu brechen, um die großen Veränderungen in der wirtschaftlichen und sozialen Struktur auch in der staatlichen Organisation und in einer geschriebenen Verfassung zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Gerade nicht intensiv industrialisierte Länder wie Russland und Italien könnten sich eine moderne Wirtschaftsverfassung geben.

In hochentwickelten Industriestaaten ist die innenpolitische Lage nach Schmitts Auffassung von dem "Phänomen der 'sozialen Gleichgewichtsstruktur' zwischen Kapital und Arbeit" beherrscht: Arbeitgeber und Arbeitnehmer stehen sich mit gleicher sozialer Macht gegenüber und keine Seite kann der anderen eine radikale Entscheidung aufdrängen, ohne eine furchtbaren Bürgerkrieg auszulösen. Dieses Phänomen sei vor allem von Otto Kirchheimer[wp] staats- und verfassungstheoretisch behandelt worden. Aufgrund der Machtgleichheit seien in den industrialisierten Staaten "auf legalem Wege soziale Entscheidungen und fundamentale Verfassungsänderungen nicht mehr möglich, und alles, was es an Staat und Regierung gibt, ist dann mehr oder weniger eben nur der neutrale (und nicht der höhere, aus eigener Kraft und Autorität entscheidende) Dritte" (Positionen und Begriffe, S. 127). Der italienische Faschismus versuche demnach, mit Hilfe einer geschlossenen Organisation diese Suprematie[wp] des Staates gegenüber der Wirtschaft herzustellen. Daher komme das faschistische Regime auf Dauer den Arbeitnehmern zugute, weil diese heute das Volk seien und der Staat nun einmal die politische Einheit des Volkes.

Die Kritik bürgerlicher Institutionen war es, die Schmitt in dieser Phase für junge sozialistische Juristen wie Ernst Fraenkel[wp], Otto Kirchheimer und Franz Neumann[wp] interessant machte.[21] Umgekehrt profitierte Schmitt von den unorthodoxen Denkansätzen dieser linken Systemkritiker. So hatte Schmitt den Titel einer seiner bekanntesten Abhandlungen (Legalität und Legitimität) von Otto Kirchheimer entliehen.[22] Ernst Fraenkel besuchte Schmitts staatsrechtliche Arbeitsgemeinschaften[23] und bezog sich positiv auf dessen Kritik des destruktiven Misstrauensvotums (Fraenkel, Verfassungsreform und Sozialdemokratie, Die Gesellschaft, 1932). Franz Neumann wiederum verfasste am 7. September 1932 einen euphorisch zustimmenden Brief anlässlich der Veröffentlichung des Buches Legalität und Legitimität (abgedruckt in: Rainer Erd, Reform und Resignation, 1985, S. 79f.). Kirchheimer urteilte über die Schrift im Jahre 1932: "Wenn eine spätere Zeit den geistigen Bestand dieser Epoche sichtet, so wird sich ihr das Buch von Carl Schmitt über Legalität und Legitimität als eine Schrift darbieten, die sich aus diesem Kreis sowohl durch ihr Zurückgehen auf die Grundlagen der Staatstheorie als auch durch ihre Zurückhaltung in den Schlussfolgerungen auszeichnet." (Verfassungsreaktion 1932, Die Gesellschaft, IX, 1932, S. 415ff.) In einem Aufsatz von Anfang 1933 mit dem Titel Verfassungsreform und Sozialdemokratie (Die Gesellschaft, X, 1933, S. 230ff.), in dem Kirchheimer verschiedene Vorschläge zur Reform der Weimarer Verfassung im Sinne einer Stärkung des Reichspräsidenten zu Lasten des Reichstags diskutierte, wies der SPD-Jurist auch auf Anfeindungen hin, der die Zeitschrift Die Gesellschaft[wp] aufgrund der positiven Anknüpfung an Carl Schmitt von kommunistischer Seite ausgesetzt war: "In Nr. 24 des Roten Aufbaus[wp] wird von 'theoretischen Querverbindungen' zwischen dem 'faschistischen Staatstheoretiker' Carl Schmitt und dem offiziellen theoretischen Organ der SPD, der Gesellschaft gesprochen, die besonders anschaulich im Fraenkelschen Aufsatz zutage treten sollen." Aus den fraenkelschen Ausführungen, in denen dieser sich mehrfach auf Schmitt bezogen hatte, ergebe sich in der logischen Konsequenz die Aufforderung zum Staatsstreich, die Fraenkel nur nicht offen auszusprechen wage. In der Tat hatte Fraenkel in der vorherigen Ausgabe der "Gesellschaft" unter ausdrücklicher Anknüpfung an Carl Schmitt geschrieben: "Es hieße, der Sache der Verfassung den schlechtesten Dienst zu erweisen, wenn man die Erweiterung der Macht des Reichspräsidenten bis hin zum Zustande der faktischen Diktatur auf den Machtwillen des Präsidenten und der hinter ihm stehenden Kräfte zurückführen will. Wenn der Reichstag zur Bewältigung der ihm gesetzten Aufgaben unfähig wird, so muß vielmehr ein anderes Staatsorgan die Funktion übernehmen, die erforderlich ist, um in gefährdeten Zeiten den Staatsapparat weiterzuführen. Solange eine Mehrheit grundsätzlich staatsfeindlicher, in sich uneiniger Parteien im Parlament, kann ein Präsident, wie immer er auch heißen mag, gar nichts anderes tun, als den destruktiven Beschlüssen dieses Parlaments auszuweichen. Carl Schmitt hat unzweifelhaft recht, wenn er bereits vor zwei Jahren ausgeführt hat, daß die geltende Reichsverfassung einem mehrheits- und handlungsfähigen Reichstag alle Rechte und Möglichkeiten gibt, um sich als den maßgebenden Faktor staatlicher Willensbildung durchzusetzen. Ist das Parlament dazu nicht im Stande, so hat es auch nicht das Recht, zu verlangen, daß alle anderen verantwortlichen Stellen handlungsunfähig werden." [24]

Trotz seiner Kritik an Pluralismus[wp] und Parlamentarischer Demokratie stand Schmitt vor der Machtergreifung[wp] 1933 den Umsturzbestrebungen von KPD[wp] und NSDAP[wp] gleichermaßen ablehnend gegenüber.[25] Er unterstützte die Politik Schleichers, die darauf abzielte, das "Abenteuer Nationalsozialismus" zu verhindern.[26]

Trotz seiner Kritik an Pluralismus[wp] und Parlamentarischer Demokratie stand Schmitt vor der Machtergreifung[wp] 1933 den Umsturzbestrebungen von KPD[wp] und NSDAP[wp] gleichermaßen ablehnend gegenüber.[25] Er unterstützte die Politik Schleichers, die darauf abzielte, das "Abenteuer Nationalsozialismus" zu verhindern.[26]

In seiner im Juli 1932 abgeschlossenen Abhandlung Legalität und Legitimität forderte der Staatsrechtler eine Entscheidung für die Substanz der Verfassung und gegen ihre Feinde.[27] Er fasste dies in eine Kritik am neukantianischen[wp] Rechtspositivismus, wie ihn der führende Verfassungskommentator Gerhard Anschütz[wp] vertrat. Gegen diesen Positivismus, der nicht nach den Zielen politischer Gruppierungen fragte, sondern nur nach formaler Legalität[wp], brachte Schmitt - hierin mit seinem Antipoden Heller einig - eine Legitimität[wp] in Stellung, die gegenüber dem Relativismus[wp] auf die Unverfügbarkeit politischer Grundentscheidungen verwies.

Die politischen Feinde der bestehenden Ordnung sollten klar als solche benannt werden, andernfalls führe die Indifferenz gegenüber verfassungsfeindlichen Bestrebungen in den politischen Selbstmord.[28] Zwar hatte Schmitt sich hier klar für eine Bekämpfung verfassungsfeindlicher Parteien ausgesprochen, was er jedoch mit einer "folgerichtigen Weiterentwicklung der Verfassung" meinte, die an gleicher Stelle gefordert wurde, blieb unklar. Hier wurde vielfach vermutet, es handele sich um einen konservativ-revolutionären[wp]"Neuen Staat" Papen'scher[wp] Prägung, wie ihn etwa Heinz Otto Ziegler beschrieben hatte (Autoritärer oder totaler Staat, 1932).[29] Verschiedene neuere Untersuchungen argumentieren dagegen, Schmitt habe im Sinne Schleichers eine Stabilisierung der politischen Situation erstrebt und Verfassungsänderungen als etwas Sekundäres betrachtet.[30] In dieser Perspektive war die geforderte Weiterentwicklung eine faktische Veränderung der Mächteverhältnisse, keine Etablierung neuer Verfassungsprinzipien.

1932 war Schmitt auf einem vorläufigen Höhepunkt seiner politischen Ambitionen angelangt: Er vertrat die Reichsregierung unter Franz von Papen[wp] zusammen mit Carl Bilfinger[wp] und Erwin Jacobi[wp] im Prozess um den so genannten Preußenschlag[wp] gegen die staatsstreichartig abgesetzte preußische Regierung Otto Braun[wp] vor dem Staatsgerichtshof[wp].[31] Als enger Berater im Hintergrund wurde Schmitt in geheime Planungen eingeweiht, die auf die Ausrufung eines Staatsnotstands hinausliefen. Schmitt und Personen aus Schleichers Umfeld wollten durch einen intrakonstitutionellen "Verfassungswandel" die Gewichte in Richtung einer konstitutionellen Demokratie mit präsidialer Ausprägung verschieben. Dabei sollten verfassungspolitisch diejenigen Spielräume genutzt werden, die in der Verfassung angelegt waren oder zumindest von ihr nicht ausgeschlossen wurden. Konkret schlug Schmitt vor, der Präsident solle gestützt auf Artikel 48[wp] regieren, destruktive Misstrauensvoten[wp] oder Aufhebungsbeschlüsse des Parlaments sollten mit Verweis auf ihre fehlende konstruktive Basis ignoriert werden. In einem Positionspapier für Schleicher mit dem Titel: "Wie bewahrt man eine arbeitsfähige Präsidialregierung vor der Obstruktion eines arbeitsunwilligen Reichstages mit dem Ziel, 'die Verfassung zu wahren'" wurde der "mildere Weg, der ein Minimum an Verfassungsverletzung darstellt", empfohlen, nämlich: "die authentische Auslegung des Art. 54 [der das Misstrauensvotum regelt] in der Richtung der naturgegebenen Entwicklung (Mißtrauensvotum gilt nur seitens einer Mehrheit, die in der Lage ist, eine positive Vertrauensgrundlage herzustellen)". Das Papier betonte: "Will man von der Verfassung abweichen, so kann es nur in der Richtung geschehen, auf die sich die Verfassung unter dem Zwang der Umstände und in Übereinstimmung mit der öffentlichen Meinung hin entwickelt. Man muß das Ziel der Verfassungswandlung im Auge behalten und darf nicht davon abweichen. Dieses Ziel ist aber nicht die Auslieferung der Volksvertretung an die Exekutive (der Reichspräsident beruft und vertagt den Reichstag), sondern es ist Stärkung der Exekutive durch Abschaffung oder Entkräftung von Art. 54 bezw. durch Begrenzung des Reichstages auf Gesetzgebung und Kontrolle. Dieses Ziel ist aber durch die authentische Interpretation der Zuständigkeit eines Mißtrauensvotums geradezu erreicht. Man würde durch einen erfolgreichen Präzedenzfall die Verfassung gewandelt haben." [32]

Wie stark Schmitt bis Ende Januar 1933 seine politischen Aktivitäten mit Kurt v. Schleicher verbunden hatte, illustriert sein Tagebucheintrag vom 27. Januar 1933: "Es ist etwas unglaubliches Geschehen. Der Hindenburg-Mythos ist zu Ende. Der Alte war schließlich auch nur ein Mac Mahon[wp]. Scheußlicher Zustand. Schleicher tritt zurück; Papen oder Hitler kommen. Der alte Herr ist verrückt geworden." [33]Auch war Schmitt, wie Schleicher, zunächst ein Gegner der Kanzlerschafts Hitlers. Am 30. Januar verzeichnet sein Tagebuch den Eintrag: "Dann zum Cafe Kutscher, wo ich hörte, daß Hitler Reichskanzler und Papen Vizekanzler geworden ist. Zu Hause gleich zu Bett. Schrecklicher Zustand." Einen Tag später hieß es: "War noch erkältet. Telefonierte Handelshochschule und sagte meine Vorlesung ab. Wurde allmählich munterer, konnte nichts arbeiten, lächerlicher Zustand, las Zeitungen, aufgeregt. Wut über den dummen, lächerlichen Hitler." [34]

Deutungsproblem 1933: Zäsur oder Kontinuität?

Nach dem Ermächtigungsgesetz[wp] vom 24. März 1933 präsentierte sich Schmitt als überzeugter Anhänger der neuen Machthaber. Ob er dies aus Opportunismus oder aus innerer Überzeugung tat, ist umstritten.

Ein wesentlicher Erfolg im neuen Regime war Schmitts Ernennung zum Preußischen Staatsrat[wp] - ein Titel, auf den er zeitlebens besonders stolz war. Indem Schmitt die Rechtmäßigkeit der "nationalsozialistischen Revolution" betonte, verschaffte er der Führung der NSDAP eine juristische Legitimation. Aufgrund seines juristischen und verbalen Einsatzes für den Staat der NSDAP wurde er von Zeitgenossen, insbesondere von politischen Emigranten (darunter Schüler und Bekannte), als "Kronjurist des Dritten Reiches" bezeichnet. Den Begriff prägte der frühere Schmitt-Epigone Waldemar Gurian[wp].[35]Ob dies nicht eine Überschätzung seiner Rolle ist, wird in der Literatur allerdings kontrovers diskutiert.

Schmitts Einsatz für das neue Regime war bedingungslos. Als Beispiel kann seine Instrumentalisierung der Verfassungsgeschichte zur Legitimation des NS-Regimes dienen.[36] Viele seiner Stellungnahmen gingen weit über das hinaus, was von einem linientreuen Juristen erwartet wurde. Schmitt wollte sich offensichtlich durch besonders schneidige Formulierungen profilieren. In Reaktion auf die Morde des NS-Regimes vom 30. Juni 1934 während der Röhm-Affäre[wp] - unter den Getöteten war auch der ihm politisch nahestehende ehemalige Reichskanzler Kurt von Schleicher[wp] - rechtfertigte er die Selbstermächtigung Hitlers mit den Worten:

Schmitts Einsatz für das neue Regime war bedingungslos. Als Beispiel kann seine Instrumentalisierung der Verfassungsgeschichte zur Legitimation des NS-Regimes dienen.[36] Viele seiner Stellungnahmen gingen weit über das hinaus, was von einem linientreuen Juristen erwartet wurde. Schmitt wollte sich offensichtlich durch besonders schneidige Formulierungen profilieren. In Reaktion auf die Morde des NS-Regimes vom 30. Juni 1934 während der Röhm-Affäre[wp] - unter den Getöteten war auch der ihm politisch nahestehende ehemalige Reichskanzler Kurt von Schleicher[wp] - rechtfertigte er die Selbstermächtigung Hitlers mit den Worten:

- "Der Führer schützt das Recht vor dem schlimmsten Missbrauch, wenn er im Augenblick der Gefahr kraft seines Führertums als oberster Gerichtsherr unmittelbar Recht schafft."

Der wahre Führer sei immer auch Richter, aus dem Führertum fließe das Richtertum.[37] Diese behauptete Übereinstimmung von "Führertum" und "Richtertum" gilt als Zeugnis einer besonderen Perversion des Rechtsdenkens. Schmitt schloss den Artikel mit dem politischen Aufruf:

- "Wer den gewaltigen Hintergrund unserer politischen Gesamtlage sieht, wird die Mahnungen und Warnungen des Führers verstehen und sich zu dem großen geistigen Kampfe rüsten, in dem wir unser gutes Recht zu wahren haben."

Öffentlich trat Schmitt wiederum als Rassist und Antisemit[38] hervor, als er die Nürnberger Rassengesetze[wp] von 1935 in selbst für nationalsozialistische Verhältnisse grotesker Stilisierung als Verfassung der Freiheit bezeichnete (so der Titel eines Aufsatzes in der Deutschen Juristenzeitung).[39]Mit dem so genannten Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre[wp], das Beziehungen zwischen Juden (in der Definition der Nationalsozialisten) und "Deutschblütigen" unter Strafe stellte, trat für Schmitt "ein neues weltanschauliches Prinzip in der Gesetzgebung" auf. Diese "von dem Gedanken der Rasse getragene Gesetzgebung" stößt, so Schmitt, auf die Gesetze anderer Länder, die ebenso grundsätzlich rassische Unterscheidungen nicht kennen oder sogar ablehnen.[40] Dieses Aufeinandertreffen unterschiedlicher weltanschaulicher Prinzipien war für Schmitt Regelungsgegenstand des Völkerrechts[wp]. Höhepunkt der Schmittschen Parteipropaganda[wp] war die im Oktober 1936 unter seiner Leitung durchgeführte Tagung Das Judentum in der Rechtswissenschaft. Hier bekannte er sich ausdrücklich zum nationalsozialistischen Antisemitismus und forderte, jüdische Autoren in der juristischen Literatur nicht mehr zu zitieren oder jedenfalls als Juden zu kennzeichnen.

- "Was der Führer über die jüdische Dialektik gesagt hat, müssen wir uns selbst und unseren Studenten immer wieder einprägen, um der großen Gefahr immer neuer Tarnungen und Zerredungen zu entgehen. Mit einem nur gefühlsmäßigen Antisemitismus ist es nicht getan; es bedarf einer erkenntnismäßig begründeten Sicherheit. [...] Wir müssen den deutschen Geist von allen Fälschungen befreien, Fälschungen des Begriffes Geist, die es ermöglicht haben, dass jüdische Emigranten den großartigen Kampf des Gauleiters Julius Streicher[wp] als etwas 'Ungeistiges' bezeichnen konnten." [41]

Etwa zur selben Zeit gab es eine nationalsozialistische Kampagne gegen Schmitt, die zu seiner weitgehenden Entmachtung führte. Reinhard Mehring schreibt dazu: "Da diese Tagung aber Ende 1936 zeitlich eng mit einer nationalsozialistischen Kampagne gegen Schmitt und seiner weitgehenden Entmachtung als Funktionsträger zusammenfiel, wurde sie - schon in nationalsozialistischen Kreisen - oft als opportunistisches Lippenbekenntnis abgetan und nicht hinreichend beachtet, bis Schmitt 1991 durch die Veröffentlichung des "Glossariums", tagebuchartiger Aufzeichnungen aus den Jahren 1947 bis 1951, auch nach 1945 noch als glühender Antisemit dastand, der kein Wort des Bedauerns über Entrechtung, Verfolgung und Vernichtung fand. Seitdem ist sein Antisemitismus ein zentrales Thema. War er katholisch-christlich oder rassistisch-biologistisch begründet? ... Die Diskussion ist noch lange nicht abgeschlossen." [42]

In dem der SS[wp] nahestehenden Parteiblatt Schwarzes Korps[wp] wurde Schmitt "Opportunismus" und eine fehlende "nationalsozialistische Gesinnung" vorgeworfen. Hinzu kamen Vorhaltungen wegen seiner früheren Unterstützung der Regierung Schleichers sowie Bekanntschaften zu Juden: "An der Seite des Juden Jacobi[wp] focht Carl Schmitt im Prozess Preußen-Reich[wp] für die reaktionäre Zwischenregierung Schleicher [sic! recte: Papen]." In den Mitteilungen zur weltanschaulichen Lage[wp] des Amtes Rosenberg[wp] hieß es, Schmitt habe "mit dem Halbjuden[wp] Jacobi gegen die herrschende Lehre die Behauptung aufgestellt, es sei nicht möglich, dass etwa eine nationalsozialistische Mehrheit im Reichstag auf Grund eines Beschlusses mit Zweidrittelmehrheit nach dem Art. 76 durch verfassungsänderndes Gesetz grundlegende politische Entscheidungen der Verfassung, etwa das Prinzip der parlamentarischen Demokratie, ändern könne, denn eine solche Verfassungsänderung sei dann Verfassungswechsel, nicht Verfassungsrevision." Ab 1936 bemühten sich demnach nationalsozialistische Organe Schmitt seiner Machtposition zu berauben, ihm eine nationalsozialistische Gesinnung abzusprechen und ihm Opportunismus nachzuweisen.[43]

Durch die Publikationen im Schwarzen Korps entstand ein Skandal, in dessen Folge Schmitt alle Ämter in den Parteiorganisationen verlor. Er blieb jedoch bis zum Ende des Krieges Professor an der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin und behielt den Titel Preußischer Staatsrat.

Bis zum Ende des Nationalsozialismus arbeitete Schmitt hauptsächlich auf dem Gebiet des Völkerrechts, versuchte aber auch hier zum Stichwortgeber des Regimes zu avancieren. Das zeigt etwa sein 1939 zu Beginn des Zweiten Weltkriegs[wp] entwickelter Begriff der "völkerrechtlichen Großraumordnung", den er als deutsche Monroe-Doktrin[wp] verstand. Dies wurde später zumeist als Versuch gewertet, die Expansionspolitik Hitlers völkerrechtlich zu fundieren. So war Schmitt etwa an der sog. Aktion Ritterbusch[wp] beteiligt, mit der zahlreiche Wissenschaftler die nationalsozialistische Raum[wp]- und Bevölkerungspolitik beratend begleiteten.[44]

Nach 1945

Das Kriegsende erlebte Schmitt in Berlin. Am 30. April 1945 wurde er von sowjetischen Truppen[wp]verhaftet, nach kurzem Verhör aber wieder auf freien Fuß gesetzt. Am 26. September 1945 verhafteten ihn die Amerikaner und internierten ihn bis zum 10. Oktober 1946 in verschiedenen Berliner Lagern[wp]. Ein halbes Jahr später wurde er erneut verhaftet, nach Nürnberg[wp] verbracht und dort anlässlich der Nürnberger Prozesse[wp] vom 29. März bis zum 13. Mai 1947 in Einzelhaft[wp] arretiert. Während dieser Zeit wurde er von Chef-Ankläger Robert M. W. Kempner[wp] als possible defendant (potentieller Angeklagter) bezüglich seiner "Mitwirkung direkt und indirekt an der Planung von Angriffskriegen, von Kriegsverbrechen[wp] und Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit[wp]" verhört. Zu einer Anklage kam es jedoch nicht, weil eine Straftat im juristischen Sinne nicht festgestellt werden konnte: "Wegen was hätte ich den Mann anklagen können?", begründete Kempner diesen Schritt später. "Er hat keine Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit begangen, keine Kriegsgefangenen getötet und keine Angriffskriege vorbereitet." [45] Schmitt selbst hatte sich in einer schriftlichen Stellungnahme als reinen Wissenschaftler beschrieben, der allerdings ein "intellektueller Abenteurer" gewesen sei und für seine Erkenntnisse einige Risiken auf sich genommen habe. Kempner entgegnete: "Wenn aber das, was Sie Erkenntnissuchen nennen, in der Ermordung von Millionen von Menschen endet?" Darauf antwortete Schmitt: "Das Christentum hat auch in der Ermordung von Millionen von Menschen geendet. Das weiß man nicht, wenn man es nicht selbst erfahren hat".[46]

Während seiner circa siebenwöchigen Einzelhaft[wp] im Nürnberger Kriegsverbrechergefängnis schrieb Schmitt verschiedene kürzere Texte, u. a. das Kapitel Weisheit der Zelle seines 1950 erschienenen Bandes Ex Captivitate Salus. Darin erinnerte er sich der geistigen Zuflucht, die ihm während seines Berliner Semesters Max Stirner[wp] geboten hatte. So auch jetzt wieder: "Max ist der Einzige, der mich in meiner Zelle besucht." Ihm verdanke er, "dass ich auf manches vorbereitet war, was mir bis heute begegnete, und was mich sonst vielleicht überrascht hätte."[47] Nachdem der Staatsrechtler nicht mehr selbst Angeklagter war, erstellte er auf Wunsch von Kempner als Experte verschiedene Gutachten, etwa über die Stellung der Reichsminister und des Chefs der Reichskanzlei[wp] oder über die Frage, warum das Beamtentum Adolf Hitler gefolgt ist.

Während seiner circa siebenwöchigen Einzelhaft[wp] im Nürnberger Kriegsverbrechergefängnis schrieb Schmitt verschiedene kürzere Texte, u. a. das Kapitel Weisheit der Zelle seines 1950 erschienenen Bandes Ex Captivitate Salus. Darin erinnerte er sich der geistigen Zuflucht, die ihm während seines Berliner Semesters Max Stirner[wp] geboten hatte. So auch jetzt wieder: "Max ist der Einzige, der mich in meiner Zelle besucht." Ihm verdanke er, "dass ich auf manches vorbereitet war, was mir bis heute begegnete, und was mich sonst vielleicht überrascht hätte."[47] Nachdem der Staatsrechtler nicht mehr selbst Angeklagter war, erstellte er auf Wunsch von Kempner als Experte verschiedene Gutachten, etwa über die Stellung der Reichsminister und des Chefs der Reichskanzlei[wp] oder über die Frage, warum das Beamtentum Adolf Hitler gefolgt ist.

Ende 1945 war Schmitt ohne jegliche Versorgungsbezüge aus dem Staatsdienst entlassen worden. Um eine Professur bewarb er sich nicht mehr, dies wäre wohl auch aussichtslos gewesen. Stattdessen zog er sich in seine Heimatstadt Plettenberg zurück, wo er weitere Veröffentlichungen - zunächst unter einem Pseudonym - vorbereitete, etwa eine Rezension des Bonner Grundgesetzes als "Walter Haustein", die in der Eisenbahnerzeitung erschien.[48] Nach dem Kriege veröffentlichte Schmitt eine Reihe von Werken, u. a. Der Nomos der Erde,[49] Theorie des Partisanen[wp][50] und Politische Theologie II, die aber nicht an seine Erfolge in der Weimarer Zeit anknüpfen konnten. 1952 konnte er sich eine Rente erstreiten, aus dem akademischen Leben blieb er aber ausgeschlossen. Eine Mitgliedschaft in der Vereinigung der Deutschen Staatsrechtslehrer[wp] wurde ihm verwehrt.

Da Schmitt sich nie von seinem Wirken im Dritten Reich[wp] distanzierte, blieb ihm eine moralische Rehabilitation, wie sie vielen anderen NS-Rechtstheoretikern zuteilwurde (zum Beispiel Theodor Maunz[wp] oder Otto Koellreutter[wp]), versagt. Zwar litt er unter der Isolation, bemühte sich allerdings auch nie um eine Entnazifizierung[wp]. In seinem Tagebuch notierte er am 1. Oktober 1949: "Warum lassen Sie sich nicht entnazifizieren? Erstens: weil ich mich nicht gern vereinnahmen lasse und zweitens, weil Widerstand durch Mitarbeit eine Nazi-Methode aber nicht nach meinem Geschmack ist." [51]

Das einzige überlieferte öffentliche Bekenntnis seiner Scham stammt aus den Verhörprotokollen von Kempner, die später veröffentlicht wurden. Kempner: "Schämen Sie sich, daß Sie damals [1933/34] derartige Dinge [wie "Der Führer schützt das Recht"] geschrieben haben?" Schmitt: "Heute selbstverständlich. Ich finde es nicht richtig, in dieser Blamage, die wir da erlitten haben, noch herumzuwühlen." Kempner: "Ich will nicht herumwühlen." Schmitt: "Es ist schauerlich, sicherlich. Es gibt kein Wort darüber zu reden." [52]

Zentraler Gegenstand der öffentlichen Vorwürfe gegen Schmitt in der Nachkriegszeit war seine Verteidigung der Röhm-Morde[wp] ("Der Führer schützt das Recht...") zusammen mit den antisemitischen Texten der von ihm geleiteten "Judentagung" 1936 in Berlin. Beispielsweise griff der Tübinger Jurist Adolf Schüle[wp] Schmitt 1959 deswegen heftig an.[53]

Zum Holocaust hat Schmitt auch nach dem Ende des nationalsozialistischen Regimes nie ein bedauerndes Wort gefunden, wie die posthum publizierten Tagebuchaufzeichnungen (Glossarium) zeigen. Stattdessen relativierte er das Verbrechen. So notierte er: "Genozide, Völkermorde, rührender Begriff."[54]Der einzige Eintrag, der sich explizit mit der Shoa befasst, lautet:

- "Wer ist der wahre Verbrecher, der wahre Urheber des Hitlerismus? Wer hat diese Figur erfunden? Wer hat die Greuelepisode in die Welt gesetzt? Wem verdanken wir die 12 Mio. [sic!] toten Juden? Ich kann es euch sehr genau sagen: Hitler hat sich nicht selbst erfunden. Wir verdanken ihn dem echt demokratischen Gehirn, das die mythische Figur des unbekannten Soldaten des Ersten Weltkriegs[wp]ausgeheckt hat." [55]

Auch von seinem Antisemitismus war Schmitt nach 1945 nicht abgewichen. Als Beweis[56] hierfür gilt ein Eintrag in sein Glossarium vom 25. September 1947, in dem er den "assimilierten Juden" als den "wahren Feind" bezeichnete. Die Beweiskraft dieser Passage wurde allerdings auch mit dem Hinweis angezweifelt, es handele sich dabei lediglich um ein nicht kenntlich gemachtes Exzerpt.[57] Der Eintrag lautet:

- "Denn Juden bleiben immer Juden. Während der Kommunist[wp] sich bessern und ändern kann. Das hat nichts mit nordischer Rasse usw. zu tun. Gerade der assimilierte[wp] Jude ist der wahre Feind. Es hat keinen Zweck, die Parole der Weisen von Zion[wp] als falsch zu beweisen." [58]

Schmitt flüchtete sich in Selbstrechtfertigungen und stilisierte sich abwechselnd als "christlicher Epimetheus[wp]" oder als "Aufhalter des Antichristen[wp]" (Katechon[wp][59]). Die Selbststilisierung wurde zu seinem Lebenselixier. Er erfand verschiedene, immer anspielungs- und kenntnisreiche Vergleiche, die seine Unschuld illustrieren sollten. So behauptete er etwa, er habe in Bezug auf den Nationalsozialismus wie der Chemiker und Hygieniker Max von Pettenkofer[wp] gehandelt, der vor Studenten eine Kultur von Cholera-Bakterien zu sich nahm, um seine Resistenz zu beweisen. So habe auch er, Schmitt, den Virus des Nationalsozialismus freiwillig geschluckt und sei nicht infiziert worden. An anderer Stelle verglich Schmitt sich mit Benito Cereno, einer Figur Herman Melvilles[wp] aus der gleichnamigen Erzählung von 1856, in der ein Kapitän auf dem eigenen Schiff von Meuterern gefangengehalten wird. Bei Begegnung mit anderen Schiffen wird der Kapitän von den aufständischen Sklaven gezwungen, nach außen hin Normalität vorzuspielen - eine absurde Tragikomödie, die den Kapitän als gefährlich, halb verrückt und völlig undurchsichtig erscheinen lässt. Auf dem Schiff steht der Spruch: "Folgt eurem Führer" ("Seguid vuestro jefe"). Sein Haus in Plettenberg titulierte Schmitt als San Casciano, in Anlehnung an den berühmten Rückzugsort Machiavellis[wp]. Machiavelli war der Verschwörung gegen die Regierung bezichtigt und daraufhin gefoltert worden. Er hatte die Folter mit einer selbst die Staatsbediensteten erstaunenden Festigkeit ertragen. Später war die Unschuld des Theoretikers festgestellt und dieser auf freien Fuß gesetzt worden. Er blieb dem Staat aber weiterhin suspekt, war geächtet und durfte nur auf seinem ärmlichen Landgut namens La Strada bei San Casciano zu Sant' Andrea in Percussina leben.

Schmitt starb im April 1985 fast 97jährig. Seine Krankheit, Zerebralsklerose[wp], brachte in Schüben immer länger andauernde Wahnvorstellungen mit sich. Schmitt, der auch schon früher durchaus paranoide[wp] Anwandlungen gezeigt hatte, fühlte sich nun von Schallwellen und Stimmen regelrecht verfolgt. Wellen wurden seine letzte Obsession. Einem Bekannten soll er gesagt haben: "Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg habe ich gesagt: Souverän ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand entscheidet. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, angesichts meines Todes, sage ich jetzt: Souverän ist, wer über die Wellen des Raumes verfügt." [60] Seine geistige Umnachtung ließ ihn überall elektronische Wanzen und unsichtbare Verfolger erblicken. Am Ostersonntag 1985 starb Schmitt alleine im Evangelischen Krankenhaus in Plettenberg. Sein Grab befindet sich auf dem dortigen katholischen Friedhof.[61]

Schmitt starb im April 1985 fast 97jährig. Seine Krankheit, Zerebralsklerose[wp], brachte in Schüben immer länger andauernde Wahnvorstellungen mit sich. Schmitt, der auch schon früher durchaus paranoide[wp] Anwandlungen gezeigt hatte, fühlte sich nun von Schallwellen und Stimmen regelrecht verfolgt. Wellen wurden seine letzte Obsession. Einem Bekannten soll er gesagt haben: "Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg habe ich gesagt: Souverän ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand entscheidet. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, angesichts meines Todes, sage ich jetzt: Souverän ist, wer über die Wellen des Raumes verfügt." [60] Seine geistige Umnachtung ließ ihn überall elektronische Wanzen und unsichtbare Verfolger erblicken. Am Ostersonntag 1985 starb Schmitt alleine im Evangelischen Krankenhaus in Plettenberg. Sein Grab befindet sich auf dem dortigen katholischen Friedhof.[61]

Denken

Die Etikettierungen Schmitts sind vielfältig. So gilt er als Nationalist, Gegner des Pluralismus[wp] und Liberalismus, Verächter des Parlamentarismus[wp], Kontrahent des Rechtsstaats, des Naturrechts[wp] und Neo-Absolutist[wp] im Gefolge eines Machiavelli[wp] und Thomas Hobbes[wp]. Zweifellos hatte sein Denken reaktionäre Züge: Er bewunderte den italienischen Faschismus, war in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus[wp] als Antisemit[wp] hervorgetreten und hatte Rechtfertigungen für nationalsozialistische Verbrechen geliefert. Schmitts Publikationen enthielten zu jeder Zeit aktuell-politische Exkurse und Bezüge, zwischen 1933 und 1945 waren diese aber eindeutig nationalsozialistisch geprägt. Für die Übernahme von Rassismus und nationalsozialistischer Blut-und-Boden-Mythologie[wp]musste er ab 1933 seine in der Weimarer-Republik entwickelte Politische Theorie[wp] nur graduell modifizieren.

Trotz dieser reaktionären Aspekte und eines offenbar zeitlebens vorhandenen, wenn auch unterschiedlich ausgeprägten Antisemitismus wird Schmitt auch heutzutage ein originelles staatsphilosophisches[wp]Denken attestiert. Im Folgenden sollen seine grundlegenden Konzepte zumindest überblicksartig skizziert werden, wobei die zeitbezogenen Aspekte in den Hintergrund treten.

Schmitt als Katholik und Kulturkritiker

Als Katholik war Schmitt von einem tiefen Pessimismus gegenüber Fortschrittsvorstellungen, Fortschrittsoptimismus und Technisierung[wp] geprägt. Vor dem Hintergrund der Ablehnung wertneutraler Denkweisen und relativistischer Konzepte[wp] entwickelte er eine spezifische Kulturkritik[wp], die sich in verschiedenen Passagen durch seine Arbeiten zieht. Insbesondere das Frühwerk enthält zum Teil kulturpessimistische Ausbrüche. Das zeigt sich vor allem in einer seiner ersten Publikationen, in der er sich mit dem Dichter Theodor Däubler[wp] und seinem Epos[wp] Nordlicht (1916) auseinandersetzte. Hier trat der Jurist vollständig hinter den kunstinteressierten Kulturkommentator zurück. Auch sind gnostische[wp] Anspielungen erkennbar, die Schmitt - er war ein großer Bewunderer Marcions[wp][62] - wiederholt einfließen ließ. Ebenso deutlich wurden Hang und Talent zur Typisierung.

Theodor Däubler war Inspirator für Schmitts Kulturkritik der Moderne

Der junge Schmitt zeigte sich als Polemiker gegen bürgerliche "Sekurität" und saturierte Passivität mit antikapitalistischen Anklängen. Diese Haltung wird vor allem in seinem Buch über Theodor Däublers[wp]Nordlicht deutlich:

- "Dies Zeitalter hat sich selbst als das kapitalistische, mechanistische[wp], relativistische bezeichnet, als das Zeitalter des Verkehrs, der Technik, der Organisation. In der Tat scheint der Betrieb ihm die Signatur zu geben. Der Betrieb als das großartig funktionierende Mittel zu irgendeinem kläglichen oder sinnlosen Zweck[wp], die universelle Vordringlichkeit des Mittels vor dem Zweck, der Betrieb, der den Einzelnen so vernichtet, daß er seine Aufhebung nicht einmal fühlt und der sich dabei nicht auf eine Idee, sondern höchstens ein paar Banalitäten beruft und immer nur geltend macht, daß alles sich glatt und ohne unnütze Reibung abwickeln müsse."

Für den Däubler referierenden Schmitt sind die Menschen durch ihren "ungeheuren materiellen Reichtum" nichts als "arme Teufel" geworden, ein "Schatten der zur Arbeit hinkt":

- " Sie wissen alles und glauben nichts. Sie interessieren sich für alles und begeistern sich für nichts. Sie verstehen alles, ihre Gelehrten registrieren in der Geschichte, in der Natur, in der eigenen Seele. Sie sind Menschenkenner, Psychologen[wp] und Soziologen[wp] und schreiben schließlich eine Soziologie der Soziologie."

Die Betrieb und Organisation gewordene Gesellschaft, dem bedingungslosen Diktat der Zweckmäßigkeit gehorchend, lässt demzufolge "keine Geheimnisse und keinen Überschwang der Seele gelten". Die Menschen sind matt und verweltlicht und können sich zu keiner transzendenten[wp] Position mehr aufraffen:

- "Sie wollen den Himmel auf der Erde, den Himmel als Ergebnis von Handel und Industrie, der tatsächlich hier auf der Erde liegen soll, in Berlin, Paris oder New York, einen Himmel mit Badeeinrichtungen, Automobilen und Klubsesseln, dessen heiliges Buch der Fahrplan wäre." [63]

Bei Däubler erschien der Fortschritt als Werk des Antichristen, des großen Zauberers. In seine Rezeption nahm Schmitt antikapitalistische Elemente auf: Der Antichrist[wp], der "unheimliche Zauberer", macht die Welt Gottes nach. Er verändert das Antlitz der Erde und macht die Natur sich untertan[wp]: "Sie dient ihm; wofür ist gleichgültig, für irgendeine Befriedigung künstlicher Bedürfnisse, für Behagen und Komfort." Die getäuschten Menschen sehen nach dieser Auffassung nur den fabelhaften Effekt. Die Natur scheint ihnen überwunden, das "Zeitalter der Sekurität" angebrochen. Für alles sei gesorgt, eine "kluge Voraussicht und Planmäßigkeit" ersetze die Vorsehung. Die Vorsehung macht der "große Zauberer" wie "irgendeine Institution":

Bei Däubler erschien der Fortschritt als Werk des Antichristen, des großen Zauberers. In seine Rezeption nahm Schmitt antikapitalistische Elemente auf: Der Antichrist[wp], der "unheimliche Zauberer", macht die Welt Gottes nach. Er verändert das Antlitz der Erde und macht die Natur sich untertan[wp]: "Sie dient ihm; wofür ist gleichgültig, für irgendeine Befriedigung künstlicher Bedürfnisse, für Behagen und Komfort." Die getäuschten Menschen sehen nach dieser Auffassung nur den fabelhaften Effekt. Die Natur scheint ihnen überwunden, das "Zeitalter der Sekurität" angebrochen. Für alles sei gesorgt, eine "kluge Voraussicht und Planmäßigkeit" ersetze die Vorsehung. Die Vorsehung macht der "große Zauberer" wie "irgendeine Institution":

- "Er weiß im unheimlichen Kreisen der Geldwirtschaft unerklärliche Werte zu schaffen, er trägt aber auch höheren kulturellen Bedürfnissen Rechnung, ohne sein Ziel dadurch zu vergessen. [...] Gold wird zum Geld, das Geld zum Kapital[wp] - und nun beginnt der verheerende Lauf des Verstandes, der alles in seinen Relativismus hereinreißt, den Aufruhr der armen Bauern mit Witzen und Kanonen höhnisch niederschlägt und endlich über die Erde reitet als einer der apokalyptischen Reiter[wp], die der Auferstehung des Fleisches vorauseilen." [64]

Sehr viel später, nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, notierte Schmitt, diese apokalyptische[wp] Sehnsucht nach Verschärfung aufgreifend, in sein Tagebuch:

- "Das ist das geheime Schlüsselwort meiner gesamten geistigen und publizistischen Existenz: das Ringen um die eigentlich katholische Verschärfung (gegen die Neutralisierer, die ästhetischen Schlaraffen, gegen Fruchtabtreiber, Leichenverbrenner und Pazifisten)." [65]

Ebenso wie Däublers Kampf gegen Technik, Fortschritt und Machbarkeit faszinierte Schmitt das negative Menschenbild der Gegenrevolution[wp]. Das Menschenbild Donoso Cortés[wp]' charakterisierte er etwa 1922 mit anklingender Bewunderung in seiner Politischen Theologie als universale Verachtung des Menschengeschlechts:

- "Seine [Cortés'] Verachtung des Menschen kennt keine Grenzen mehr; ihr blinder Verstand, ihr schwächlicher Wille, der lächerliche Elan ihrer fleischlichen Begierden scheinen ihm so erbärmlich, daß alle Worte aller menschlichen Sprachen nicht ausreichen, um die ganze Niedrigkeit dieser Kreatur auszudrücken. Wäre Gott nicht Mensch geworden - das Reptil, das mein Fuß zertritt, wäre weniger verächtlich als ein Mensch. Die Stupidität der Massen ist ihm ebenso erstaunlich wie die dumme Eitelkeit ihrer Führer. Sein Sündenbewußtsein ist universal, furchtbarer als das eines Puritaners[wp]. [...] Die Menschheit taumelt blind durch ein Labyrinth, dessen Eingang, Ausgang und Struktur keiner kennt, und das nennen wir Geschichte; die Menschheit ist ein Schiff, das ziellos auf dem Meer umhergeworfen wird, bepackt mit einer aufrührerischen, ordinären, zwangsweise rekrutierten Mannschaft, die gröhlt und tanzt, bis Gottes Zorn das rebellische Gesindel ins Meer stößt, damit wieder Schweigen herrsche."[66]

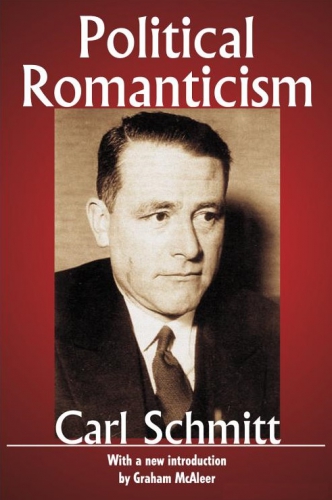

In der Politischen Romantik weitete Schmitt 1919 die Polemik gegen den zeitgenössischen Literaturbetrieb aus den bereits 1913 erschienenen Schattenrissen zu einer grundsätzlichen Kritik des bürgerlichen[wp] Menschentyps aus. Die Romantik[wp] ist für ihn "psychologisch und historisch ein Produkt bürgerlicher Sekurität". Der Romantiker, so Schmitts Kritik, will sich für nichts mehr entscheiden, sondern nur erleben und sein Erleben stimmungsvoll umschreiben:

- "Weder logische Distinktionen, noch moralische Werturteile, noch politische Entscheidungen sind ihm möglich. Die wichtigste Quelle politischer Vitalität, der Glaube an das Recht und die Empörung über das Unrecht, existiert nicht für ihn".

Hier zieht sich eine Linie durch das schmittsche Frühwerk. Das "Zeitalter der Sekurität" führt für ihn zu Neutralisierung und Entpolitisierung und damit zu einer Vernichtung der staatlichen Lebensgrundlage. Denn dem Romantiker ist "jede Beziehung zu einem rechtlichen oder moralischen Urteil disparat". Jede Norm[wp] erscheint ihm als "antiromantische Tyrannei". Eine rechtliche oder moralische Entscheidung ist dem Romantiker also sinnlos:

- "Der Romantiker ist deshalb nicht in der Lage, aus bewußtem Entschluß Partei zu ergreifen und sich zu entscheiden. Nicht einmal die Staatstheorie, die von dem 'von Natur bösen' Menschen ausgeht, kann er mit romantischen Mitteln entschieden ablehnen, denn wenn sie auch noch so vielen Romantikern unsympathisch ist, so besteht doch die Möglichkeit, auch diesen bösen Menschen, die 'Bestie', zu romantisieren, sofern sie nur weit genug entfernt ist. Romantisch handelt es sich eben um Höheres als um eine Entscheidung. Die selbstbewußte Frühromantik[wp], die sich vom Schwung der andern irrationalen[wp] Bewegungen ihrer Zeit tragen ließ und zudem das absolute, weltschöpferische Ich spielte, empfand das als Überlegenheit."

Daher gibt es nach Schmitt keine politische Produktivität im Romantischen. Es wird vielmehr völlige Passivität gepredigt und auf "mystische, theologische und traditionalistische Vorstellungen, wie Gelassenheit, Demut und Dauer" verwiesen.

- "Das ist also der Kern aller politischer Romantik: der Staat ist ein Kunstwerk, der Staat der historisch-politischen Wirklichkeit ist occasio zu der das Kunstwerk produzierenden schöpferischen Leistung des romantischen Subjekts, Anlaß zur Poesie und zum Roman, oder auch zu einer bloßen romantischen Stimmung." [67]

In seiner Schrift Römischer Katholizismus und politische Form (1923) analysierte Schmitt die Kirche[wp]als eine Complexio Oppositorum, also eine alles umspannende Einheit der Widersprüche. Schmitt diagnostiziert einen "anti-römischen Affekt". Dieser Affekt, der sich Schmitt zufolge durch die Jahrhunderte zieht, resultiert aus der Angst vor der unfassbaren politischen Macht des römischen Katholizismus, der "päpstlichen Maschine", also eines ungeheuren hierarchischen Verwaltungsapparats, der das religiöse Leben kontrollieren und die Menschen dirigieren will. Bei Dostojewski[wp] und seinem "Großinquisitor"[wp] erhebt sich demnach das anti-römische Entsetzen noch einmal zu voller säkularer[wp]Größe.

Zu jedem Weltreich, also auch dem römischen, gehöre ein gewisser Relativismus gegenüber der "bunten Menge möglicher Anschauungen, rücksichtslose Überlegenheit über lokale Eigenarten und zugleich opportunistische Toleranz in Dingen, die keine zentrale Bedeutung haben". In diesem Sinne sei die Kirche Complexio Oppositorum: "Es scheint keinen Gegensatz zu geben, den sie nicht umfasst". Dabei wird das Christentum nicht als Privatsache und reine Innerlichkeit[wp] aufgefasst, sondern zu einer "sichtbaren Institution" gestaltet. Ihr Formprinzip sei das der Repräsentation.[68] Dieses Prinzip der Institution sei der Wille zur Gestalt, zur politischen Form.

Zu jedem Weltreich, also auch dem römischen, gehöre ein gewisser Relativismus gegenüber der "bunten Menge möglicher Anschauungen, rücksichtslose Überlegenheit über lokale Eigenarten und zugleich opportunistische Toleranz in Dingen, die keine zentrale Bedeutung haben". In diesem Sinne sei die Kirche Complexio Oppositorum: "Es scheint keinen Gegensatz zu geben, den sie nicht umfasst". Dabei wird das Christentum nicht als Privatsache und reine Innerlichkeit[wp] aufgefasst, sondern zu einer "sichtbaren Institution" gestaltet. Ihr Formprinzip sei das der Repräsentation.[68] Dieses Prinzip der Institution sei der Wille zur Gestalt, zur politischen Form.

Die hier anklingenden strukturellen Analogien zwischen theologischen[wp] und staatsrechtlichen[wp]Begriffen verallgemeinerte Schmitt 1922 in der Politischen Theologie zu der These:

- "Alle prägnanten Begriffe der modernen Staatslehre[wp] sind säkularisierte theologische Begriffe. Nicht nur ihrer historischen Entwicklung nach, weil sie aus der Theologie auf die Staatslehre übertragen wurden, sondern auch in ihrer systematischen Struktur, deren Erkenntnis notwendig ist für eine soziologische Betrachtung dieser Begriffe." [69]

Schon im Frühwerk wird erkennbar, dass Schmitt bürgerliche und liberale Vorstellungen von Staat und Politik zurückwies. Für ihn war der Staat nicht statisch und normativ, sondern vital, dynamisch und faktisch. Daher betonte er das Element der Dezision[wp] gegenüber der Deliberation[wp] und die Ausnahme gegenüber der Norm. Schmitts Staatsvorstellung war organisch, nicht technizistisch. Der politische Denker Schmitt konzentrierte sich vor allem auf soziale Prozesse, die Staat und Verfassung seiner Meinung nach vorausgingen und beide jederzeit gefährden oder aufheben konnten. Als Rechtsphilosoph behandelte er von verschiedenen Perspektiven aus das Problem der Rechtsbegründung und die Frage nach der Geltung von Normen[wp].

Schmitt als politischer Denker

Schmitts Auffassung des Staates setzt den Begriff des Politischen voraus. Anstelle eines Primats des Rechts, postuliert er einen Primat der Politik[wp]. In diesem Sinne war er, wie hier nur angemerkt sei, ein Nestor der jungen akademischen Disziplin der "Politikwissenschaft"[wp]. Der Rechtsordnung, d. h. der durch das Recht gestalteten und definierten Ordnung, geht für Schmitt immer eine andere, nämlich eine staatliche Ordnung voraus. Es ist diese vor-rechtliche Ordnung, die es dem Recht erst ermöglicht, konkrete Wirklichkeit zu werden. Mit anderen Worten: Das Politische folgt einer konstitutiven[wp] Logik, das Rechtswesen einer regulativen. Die Ordnung wird bei Schmitt durch den Souverän[wp] hergestellt, der unter Umständen zu ihrer Sicherung einen Gegner zum existentiellen Feind erklären kann, den es zu bekämpfen, womöglich zu vernichten gelte. Um dies zu tun, dürfe der Souverän die Schranken beseitigen, die mit der Idee des Rechts gegeben sind.

Der Mensch ist für den Katholiken Schmitt nicht von Natur aus gut, allerdings auch nicht von Natur aus böse, sondern unbestimmt - also fähig zum Guten wie zum Bösen. Damit wird er aber (zumindest potentiell) gefährlich und riskant. Weil der Mensch nicht vollkommen gut ist, bilden sich Feindschaften. Derjenige Bereich, in dem zwischen Freund und Feind unterschieden wird, ist für Schmitt die Politik. Der Feind ist in dieser auf die griechische Antike zurückgehenden Sicht immer der öffentliche Feind (hostis bzw. "πολέμιος"), nie der private Feind (inimicus bzw. ""εχθρός"). Die Aufforderung "Liebet eure Feinde" aus der Bergpredigt[wp] (nach der Vulgata[wp]: diligite inimicos vestros, Matthäus 5,44 und Lukas 6,27) beziehe sich dagegen auf den privaten Feind. In einem geordneten Staatswesen gibt es somit für Schmitt eigentlich keine Politik, jedenfalls nicht im existentiellen Sinne einer radikalen Infragestellung, sondern nur sekundäre Formen des Politischen (z. B. Polizei).

Unter Politik versteht Schmitt einen Intensitätsgrad der Assoziation und Dissoziation von Menschen ("Die Unterscheidung von Freund und Feind hat den Sinn, den äußersten Intensitätsgrad einer Verbindung oder Trennung, einer Assoziation oder Dissoziation zu bezeichnen"). Diese dynamische, nicht auf ein Sachgebiet begrenzte Definition eröffnete eine neue theoretische Fundierung politischer Phänomene. Für Schmitt war diese Auffassung der Politik eine Art Grundlage seiner Rechtsphilosophie. Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde[wp] führt in seiner Abhandlung Der Begriff des Politischen als Schlüssel zum staatsrechtlichen Werk Carl Schmitts (Abdruck in: Recht, Staat, Freiheit, 1991) dazu aus: Nur wenn die Intensität unterhalb der Schwelle der offenen Freund-Feind-Unterscheidung gehalten werde, besteht Schmitt zufolge eine Ordnung. Im anderen Falle drohen Krieg oder Bürgerkrieg. Im Kriegsfall hat man es in diesem Sinne mit zwei souveränen Akteuren zu tun; der Bürgerkrieg[wp] stellt dagegen die innere Ordnung als solche in Frage. Eine Ordnung existiert nach Schmitt immer nur vor dem Horizont ihrer radikalen Infragestellung. Die Feind-Erklärung ist dabei ausdrücklich immer an den extremen Ausnahmefall gebunden (extremis neccessitatis causa).

Schmitt selbst gibt keine Kriterien dafür an die Hand, unter welchen Umständen ein Gegenüber als Feind zu beurteilen ist. Im Sinne seines Denkens ist das folgerichtig, da sich das Existenzielle einer vorgängigen Normierung entzieht. Als (öffentlichen) Feind fasst er denjenigen auf, der per autoritativer Setzung durch den Souverän zum Feind erklärt wird. Diese Aussage ist zwar anthropologisch realistisch, gleichwohl ist sie theoretisch problematisch. In eine ähnliche Richtung argumentiert Günther Jakobs[wp] mit seinem Konzept des Feindstrafrechts[wp] zum Umgang mit Staatsfeinden. In diesem Zusammenhang wird häufig auf Carl Schmitt verwiesen, auch wenn Jakobs Schmitt bewusst nicht zitiert hat. So heißt es bei dem Publizisten Thomas Uwer 2006: "An keiner Stelle zitiert Jakobs Carl Schmitt, aber an jeder Stelle scheint er hervor".[70] Auch die vom damaligen Innenminister Wolfgang Schäuble[wp] ausgehende öffentliche Debatte um den Kölner Rechtsprofessor Otto Depenheuer[wp] und dessen These zur Selbstbehauptung des Staates bei terroristischer Bedrohung gehören in diesen Zusammenhang, da Depenheuer sich ausdrücklich auf Schmitt beruft.[71]

Schmitt selbst gibt keine Kriterien dafür an die Hand, unter welchen Umständen ein Gegenüber als Feind zu beurteilen ist. Im Sinne seines Denkens ist das folgerichtig, da sich das Existenzielle einer vorgängigen Normierung entzieht. Als (öffentlichen) Feind fasst er denjenigen auf, der per autoritativer Setzung durch den Souverän zum Feind erklärt wird. Diese Aussage ist zwar anthropologisch realistisch, gleichwohl ist sie theoretisch problematisch. In eine ähnliche Richtung argumentiert Günther Jakobs[wp] mit seinem Konzept des Feindstrafrechts[wp] zum Umgang mit Staatsfeinden. In diesem Zusammenhang wird häufig auf Carl Schmitt verwiesen, auch wenn Jakobs Schmitt bewusst nicht zitiert hat. So heißt es bei dem Publizisten Thomas Uwer 2006: "An keiner Stelle zitiert Jakobs Carl Schmitt, aber an jeder Stelle scheint er hervor".[70] Auch die vom damaligen Innenminister Wolfgang Schäuble[wp] ausgehende öffentliche Debatte um den Kölner Rechtsprofessor Otto Depenheuer[wp] und dessen These zur Selbstbehauptung des Staates bei terroristischer Bedrohung gehören in diesen Zusammenhang, da Depenheuer sich ausdrücklich auf Schmitt beruft.[71]

Dabei bewegt sich eine politische Daseinsform bei Schmitt ganz im Bereich des Existenziellen[wp]. Normative Urteile kann man über sie nicht fällen ("Was als politische Größe existiert, ist, juristisch betrachtet, wert, dass es existiert"). Ein solcher Relativismus[wp] und Dezisionismus[wp][72] bindet eine politische Ordnung nicht an Werte wie Freiheit oder Gerechtigkeit, im Unterschied z. B. zu Montesquieu[wp], sondern sieht den höchsten Wert axiomatisch[wp] im bloßen Vorhandensein dieser Ordnung selbst. Diese und weitere irrationalistische[wp] Ontologismen[wp], etwa sein Glaube an einen "Überlebenskampf zwischen den Völkern", machten Schmitt aufnahmefähig für die Begriffe und die Rhetorik der Nationalsozialisten. Das illustriert die Grenze und zentrale Schwäche von Schmitts Begriffsbildung.

Schmitts Rechtsphilosophie

Schmitt betonte, er habe als Jurist eigentlich nur "zu Juristen und für Juristen" geschrieben. Neben einer großen Zahl konkreter verfassungs- und völkerrechtlicher Gutachten legte er auch eine Reihe systematischer Schriften vor, die stark auf konkrete Situationen hin angelegt waren. Trotz der starken fachjuristischen Ausrichtung ist es möglich, aus der Vielzahl der Bücher und Aufsätze eine mehr oder weniger geschlossene Rechtsphilosophie[wp] zu rekonstruieren. Eine solche geschlossene Lesart veröffentlichte zuletzt 2004 der Luxemburger Rechtsphilosoph und Machiavelli-Kenner Norbert Campagna.[73]

Schmitts rechtsphilosophisches Grundanliegen ist das Denken des Rechts vor dem Hintergrund der Bedingungen seiner Möglichkeit. Das abstrakte Sollen[wp] setzt demnach immer ein bestimmtes geordnetes Sein[wp] voraus, das ihm erst die Möglichkeit gibt, sich zu verwirklichen. Schmitt denkt also in genuin rechtssoziologischen[wp] Kategorien. Ihn interessiert vor allem die immer gegebene Möglichkeit, dass Rechtsnormen[wp] und Rechtsverwirklichung auseinander fallen. Zunächst müssen nach diesem Konzept die Voraussetzungen geschaffen werden, die es den Rechtsgenossen ermöglichen, sich an die Rechtsnormen zu halten. Da die "normale" Situation aber für Schmitt immer fragil und gefährdet ist, kann seiner Ansicht nach die paradoxe Notwendigkeit eintreten, dass gegen Rechtsnormen verstoßen werden muss, um die Möglichkeit einer Geltung des Rechts[wp] herzustellen. Damit erhebt sich für Schmitt die Frage, wie das Sollen sich im Sein ausdrücken kann, wie also aus dem gesollten Sein ein existierendes Sein werden kann.

Verfassung, Souveränität und Ausnahmezustand

Der herrschenden Meinung der Rechtsphilosophie, vor allem aber dem Liberalismus, warf Schmitt vor, das selbständige Problem der Rechtsverwirklichung zu ignorieren.[74] Dieses Grundproblem ist für ihn unlösbar mit der Frage nach Souveränität, Ausnahmezustand[wp] und einem Hüter der Verfassung verknüpft. Anders als liberale Denker, denen er vorwarf, diese Fragen auszublenden, definierte Schmitt den Souverän als diejenige staatliche Gewalt, die in letzter Instanz, also ohne die Möglichkeit Rechtsmittel einzulegen, entscheidet.[75] Den Souverän betrachtet er als handelndes Subjekt und nicht als Rechtsfigur. Laut Schmitt ist er nicht juristisch geformt, aber durch ihn entsteht die juristische Form, indem der Souverän die Rahmenbedingungen des Rechts herstellt. "Die Ordnung muss hergestellt sein, damit die Rechtsordnung einen Sinn hat"[76] Wie Campagna betont hängt damit allerdings auch das Schicksal der Rechtsordnung von der sie begründenden Ordnung ab.[77]

Als erster entwickelte Schmitt keine Staatslehre[wp], sondern eine Verfassungslehre[wp]. Die Verfassung bezeichnete er in ihrer positiven Substanz als "eine konkrete politische Entscheidung über Art und Form der politischen Existenz". Diesen Ansatz grenzt er mit der Formel "Entscheidung aus dem normativen Nichts" positivistisch[wp] gegen naturrechtliche[wp] Vorstellungen ab. Erst wenn der souveräne Verfassungsgeber bestimmte Inhalte als Kern der Verfassung hervorhebt, besitzt die Verfassung demnach einen substanziellen Kern.

Zum politischen Teil der modernen Verfassung gehören für Schmitt etwa die Entscheidung für die Republik[wp], die Demokratie und den Parlamentarismus[wp], wohingegen das Votum für die Grundrechte und die Gewaltenteilung den rechtsstaatlichen Teil der Verfassung ausmacht. Während der politische Teil das Funktionieren des Staates konstituiert, zieht der rechtsstaatliche Teil, so Schmitt, diesem Funktionieren Grenzen. Eine Verfassung nach Schmitts Definition hat immer einen politischen Teil, nicht unbedingt aber einen rechtsstaatlichen. Damit Grundrechte überhaupt wirksam sein können, muss es für Schmitt zunächst einen Staat geben, dessen Macht sie begrenzen. Mit diesem Konzept verwirft er implizit den naturrechtlichen Gedanken universeller Menschenrechte, die für jede Staatsform[wp] unabhängig von durch den Staat gesetztem Recht[wp] gelten, und setzt sich auch hier in Widerspruch zum Liberalismus.

Jede Verfassung steht in ihrem Kern, argumentiert Schmitt, nicht zur Disposition wechselnder politischer Mehrheiten, das Verfassungssystem ist vielmehr unveränderlich. Es sei nicht der Sinn der Verfassungsbestimmungen über die Verfassungsrevision, ein Verfahren zur Beseitigung des Ordnungssystems zu eröffnen, das durch die Verfassung konstituiert werden soll. Wenn in einer Verfassung die Möglichkeit einer Verfassungsrevision vorgesehen ist, so solle das keine legale[wp] Methode zu ihrer eigenen Abschaffung etablieren.[78]

Durch die politische Verfassung, also die Entscheidung über Art und Form der Existenz, entsteht demzufolge eine Ordnung, in der Normen wirksam werden können ("Es gibt keine Norm, die auf ein Chaos anwendbar wäre"). Im eigentlichen Sinne politisch ist eine Existenzform nur dann, wenn sie kollektiv ist, wenn also ein vom individuellen Gut eines jeden Mitglieds verschiedenes kollektives Gut im Vordergrund steht. In der Verfassung, so Schmitt, drücken sich immer bestimmte Werte aus, vor deren Hintergrund unbestimmte Rechtsbegriffe wie die "öffentliche Sicherheit"[wp] erst ihren konkreten Inhalt erhalten. Die Normalität[wp] könne nur vor dem Hintergrund dieser Werte überhaupt definiert werden. Das wesentliche Element der Ordnung ist dabei für Schmitt die Homogenität[wp] als Übereinstimmung aller bezüglich der fundamentalen Entscheidung hinsichtlich des politischen Seins der Gemeinschaft.[79] Dabei ist Schmitt bewusst, dass es illusorisch wäre, eine weitreichende gesellschaftliche Homogenität erreichen zu wollen. Er bezeichnet die absolute Homogenität daher als "idyllischen Fall".

Durch die politische Verfassung, also die Entscheidung über Art und Form der Existenz, entsteht demzufolge eine Ordnung, in der Normen wirksam werden können ("Es gibt keine Norm, die auf ein Chaos anwendbar wäre"). Im eigentlichen Sinne politisch ist eine Existenzform nur dann, wenn sie kollektiv ist, wenn also ein vom individuellen Gut eines jeden Mitglieds verschiedenes kollektives Gut im Vordergrund steht. In der Verfassung, so Schmitt, drücken sich immer bestimmte Werte aus, vor deren Hintergrund unbestimmte Rechtsbegriffe wie die "öffentliche Sicherheit"[wp] erst ihren konkreten Inhalt erhalten. Die Normalität[wp] könne nur vor dem Hintergrund dieser Werte überhaupt definiert werden. Das wesentliche Element der Ordnung ist dabei für Schmitt die Homogenität[wp] als Übereinstimmung aller bezüglich der fundamentalen Entscheidung hinsichtlich des politischen Seins der Gemeinschaft.[79] Dabei ist Schmitt bewusst, dass es illusorisch wäre, eine weitreichende gesellschaftliche Homogenität erreichen zu wollen. Er bezeichnet die absolute Homogenität daher als "idyllischen Fall".

Seit dem 19. Jahrhundert besteht laut Schmitt die Substanz der Gleichheit vor allem in der Zugehörigkeit zu einer bestimmten Nation[wp]. Homogenität in der modernen Demokratie ist aber nie völlig zu verwirklichen, sondern es liegt stets ein "Pluralismus"[wp] partikularer[wp] Interessen vor, daher ist nach Schmitts Auffassung die "Ordnung" immer gefährdet. Die Kluft von Sein und Sollen könne jederzeit aufbrechen. Der für Schmitt zentrale Begriff der Homogenität ist zunächst nicht ethnisch[wp] oder gar rassistisch gedacht, sondern vielmehr positivistisch: Die Nation verwirklicht sich in der Absicht, gemeinsam eine Ordnung zu bilden. Nach 1933 stellte Schmitt sein Konzept allerdings ausdrücklich auf den Begriff der "Rasse" ab.

Der Souverän schafft und garantiert in Schmitts Denken die Ordnung. Hierfür hat er das Monopol der letzten Entscheidung. Souveränität ist für Schmitt also juristisch von diesem Entscheidungsmonopol her zu definieren ("Souverän ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand entscheidet"), nicht von einem Gewalt- oder Herrschaftsmonopol[wp] aus. Die im Ausnahmezustand getroffenen Entscheidungen (Verurteilungen, Notverordnungen[wp] etc.) lassen sich aus Schmitts Sicht hinsichtlich ihrer Richtigkeit nicht anfechten ("Dass es die zuständige Stelle war, die eine Entscheidung fällt, macht die Entscheidung [...] unabhängig von der Richtigkeit ihres Inhaltes"). Souverän ist für Schmitt dabei immer derjenige, der den Bürgerkrieg[wp] vermeiden oder wirkungsvoll beenden kann.

Die Ausnahmesituation hat daher den Charakter eines heuristischen[wp] Prinzips:

- "Die Ausnahme ist interessanter als der Normalfall. Das Normale beweist nichts, die Ausnahme beweist alles; sie bestätigt nicht nur die Regel, die Regel lebt überhaupt nur von der Ausnahme. In der Ausnahme durchbricht die Kraft des wirklichen Lebens die Kruste einer in der Wiederholung erstarrten Mechanik." [80]

Repräsentation, Demokratie und Homogenität

Der moderne Staat ist für Schmitt demokratisch legitimiert. Demokratie in diesem Sinne bedeutet die "Identität von Herrscher und Beherrschten, Regierenden und Regierten, Befehlenden und Gehorchenden". Zum Wesen der Demokratie gehört die "Gleichheit", die sich allerdings nur nach innen richtet und daher nicht die Bürger anderer Staaten umfasst. Innerhalb eines demokratischen Staatswesens sind alle Staatsangehörigen gleich. Demokratie als Staatsform setzt laut Schmitt immer ein "politisch geeintes Volk" voraus. Die demokratische Gleichheit verweist damit auf eine Gleichartigkeit bzw. Homogenität. In der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus[wp] bezeichnete Schmitt dieses Postulat nicht mehr als "Gleichartigkeit", sondern als "Artgleichheit".

Die Betonung der Notwendigkeit einer relativen Homogenität teilt Schmitt mit seinem Antipoden Hermann Heller[wp], der die Homogenität jedoch sozial und nicht politisch verstand.[81] Heller hatte sich im Jahre 1928 brieflich an Schmitt gewandt, da er eine Reihe von Gemeinsamkeiten im verfassungspolitischen Urteil bemerkt hatte. Neben der Frage der politischen Homogenität betraf das vor allem die Nutzung des Notverordnungsparagraphen Art. 48 in der Weimarer Verfassung[wp], zu der Schmitt 1924 ein Referat auf der Versammlung der Staatsrechtslehrer gehalten hatte, mit dem Heller übereinstimmte. Der Austausch brach jedoch abrupt wieder ab, nachdem Heller Schmitts Begriff des Politischen Bellizismus[wp]vorgeworfen hatte. Schmitt hatte diesem Urteil vehement widersprochen.

Die Betonung der Notwendigkeit einer relativen Homogenität teilt Schmitt mit seinem Antipoden Hermann Heller[wp], der die Homogenität jedoch sozial und nicht politisch verstand.[81] Heller hatte sich im Jahre 1928 brieflich an Schmitt gewandt, da er eine Reihe von Gemeinsamkeiten im verfassungspolitischen Urteil bemerkt hatte. Neben der Frage der politischen Homogenität betraf das vor allem die Nutzung des Notverordnungsparagraphen Art. 48 in der Weimarer Verfassung[wp], zu der Schmitt 1924 ein Referat auf der Versammlung der Staatsrechtslehrer gehalten hatte, mit dem Heller übereinstimmte. Der Austausch brach jedoch abrupt wieder ab, nachdem Heller Schmitts Begriff des Politischen Bellizismus[wp]vorgeworfen hatte. Schmitt hatte diesem Urteil vehement widersprochen.

In der Frage der politischen Homogenität hat sich auch das Bundesverfassungsgericht in dem berühmten Maastricht-Urteil[wp] 1993 auf eine relative politische Homogenität berufen: "Die Staaten bedürfen hinreichend bedeutsamer eigener Aufgabenfelder, auf denen sich das jeweilige Staatsvolk in einem von ihm legitimierten und gesteuerten Prozeß politischer Willensbildung entfalten und artikulieren kann, um so dem, was es - relativ homogen - geistig, sozial und politisch verbindet, rechtlichen Ausdruck zu geben." Dabei bezog es sich ausdrücklich auf Hermann Heller, obwohl der Sachverhalt inhaltlich eher Schmitt hätte zugeordnet werden müssen. Dazu schreibt der Experte für Öffentliches Recht[wp] Alexander Proelß[wp] 2003: "Die Benennung Hellers zur Stützung der Homogenitätsvoraussetzung des {Staatsvolkes geht jedenfalls fehl [...]. Das Gericht dürfte primär das Ziel verfolgt haben, der offenbar als wenig wünschenswert erschienenen Zitierung des historisch belasteten Schmitt auszuweichen."[82]

Hinter den bloß partikularen Interessen muss es, davon geht Schmitt im Sinne Rousseaus[wp] aus, eine volonté générale[wp] geben, also ein gemeinsames, von allen geteiltes Interesse. Diese "Substanz der Einheit" ist eher dem Gefühl als der Rationalität zugeordnet. Wenn eine starke und bewusste Gleichartigkeit und damit die politische Aktionsfähigkeit fehlt, bedarf es nach Schmitt der Repräsentation[wp]. Wo das Element der Repräsentation in einem Staat überwiege, nähere sich der Staat der Monarchie[wp], wo indes das Element der Identität stärker sei, nähere sich der Staat der Demokratie. In dem Moment, in dem in der Weimarer Republik[wp] der Bürgerkrieg als reale Gefahr am Horizont erschien, optierte Schmitt daher für einen souveränen Reichspräsidenten[wp] als Element der "echten Repräsentation". Den Parlamentarismus[wp] bezeichnete er dagegen als "unechte Fassade", die sich geistesgeschichtlich[wp] überholt habe. Das Parlament lehnte er als "Hort der Parteien[wp]" und "Partikularinteressen" ab. In Abgrenzung dazu unterstrich er, dass der demokratisch legitimierte Präsident die Einheit repräsentiere. Als Repräsentant der Einheit ist aus dieser Sicht der Souverän der "Hüter der Verfassung", der politischen Substanz der Einheit.

Diktatur, Legalität und Legitimität

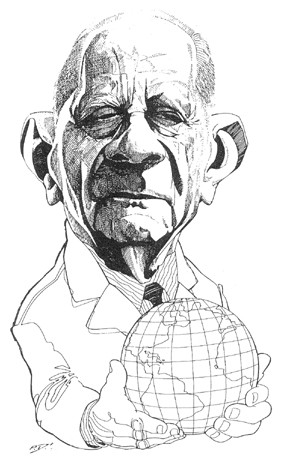

Der "Leviathan" - Hobbes'sches Sinnbild des modernen Staates - wird in den Augen Schmitts vom Pluralismus der indirekten Gewalten vernichtet.

Das Instrument, mit dem der Souverän die gestörte Ordnung wiederherstellt, ist Schmitt zufolge die "Diktatur"[wp], die nach seiner Auffassung das Rechtsinstitut der Gefahrenabwehr[wp] darstellt (vgl. Artikel Ausnahmezustand[wp]). Eine solche Diktatur, verstanden in der altrömischen Grundbedeutung[wp] als Notstandsherrschaft[wp] zur "Wiederherstellung der bedrohten Ordnung", ist nach Schmitts Beurteilung zwar durch keine Rechtsnorm gebunden, trotzdem bildet das Recht immer ihren Horizont. Zwischen dieser Diktatur und der "Rechtsidee" besteht dementsprechend nur ein relativer, kein absoluter Gegensatz.

Die Diktatur, so Schmitt, sei ein bloßes Mittel, um einer gefährdeten "Normalität" wieder diejenige Stabilität zu verleihen, die für die Anwendung und die Wirksamkeit des Rechts erforderlich ist. Indem der Gegner sich nicht mehr an die Rechtsnorm hält, wird die Diktatur als davon abhängige Antwort erforderlich. Die Diktatur stellt somit die Verbindung zwischen Sein und Sollen (wieder) her, indem sie die Rechtsnorm vorübergehend suspendiert, um die "Rechtsverwirklichung" zu ermöglichen. Schmitt:

- "Dass jede Diktatur die Ausnahme von einer Norm enthält, besagt nicht zufällige Negation einer beliebigen Norm. Die innere Dialektik[wp] des Begriffs liegt darin, dass gerade die Norm negiert wird, deren Herrschaft durch die Diktatur in der geschichtlich-politischen Wirklichkeit gesichert werden soll."[83]

Das "Wesen der Diktatur" sieht er im Auseinanderfallen von Recht und Rechtsverwirklichung:

- "Zwischen der Herrschaft der zu verwirklichenden Norm und der Methode ihrer Verwirklichung kann also ein Gegensatz bestehen. Rechtsphilosophisch[wp] liegt hier das Wesen der Diktatur, nämlich der allgemeinen Möglichkeit einer Trennung von Normen des Rechts und Normen der Rechtsverwirklichung." [83][84]

Schmitt moniert, dass die "liberale Rechtsphilosophie" diesem selbständigen bedeutenden "Problem der Rechtsverwirklichung"[85] mit Ignoranz begegne, da ihre Vertreter auf den "Normalfall" fixiert seien und den Ausnahmefall ausblendeten. Campagna fasst diese Schmittsche Position wie folgt zusammen:

- "Im Normalfall braucht man die Rechtsnormen nicht zu verletzen, um die Verwirklichung dieser Normen zu sichern, aber weil dieser Normalfall, bei einer realistischen Betrachtung der menschlichen Angelegenheiten, nicht auf alle Ewigkeiten abgesichert ist, muß man immer mit der Möglichkeit rechnen, daß die Rechts- und die Rechtsverwirklichungsnormen sich trennen werden, daß man also gegen die Rechtsnormen verstoßen muß, um die Möglichkeit eines rechtlichen Zusammenlebens zu garantieren." [74]