Editor’s Note:

The following text is the transcript by V. S. of Jonathan Bowden’s New Right lecture in London on January 21, 2012. I want to thank Michèle Renouf for making the recording available.

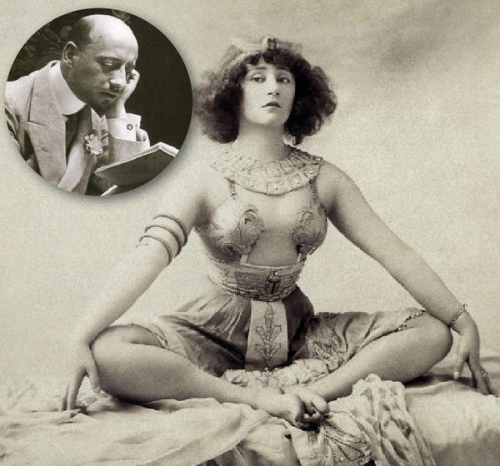

Gabriele D’Annunzio had basically two careers, one of which was as a writer and literati and the other was as a politician and a national figure. If you look him up on Wikipedia there’s a strange incident which occurred in 1922 when D’Annunzio was pushed out of a window several floors up in a particular dwelling and was badly injured and semi-crippled for a while. Of course, this was during a crucial period in Italian politics because Mussolini emerged as leader of the country and was made prime minister after the March on Rome under a still monarchical system and absorbed and swallowed up all other Italian parties to form the Fascist state in Italy that lasted right until the end of the Second World War.

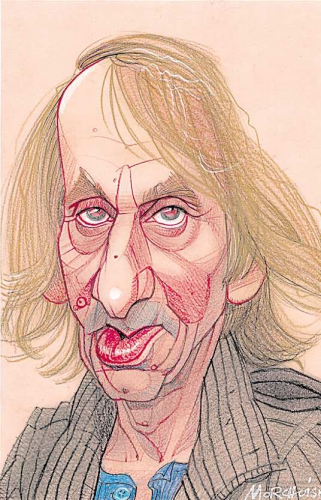

D’Annunzio as a figure was involved in the Romantic and Decadent movement in Italian literature. He wrote a large number of plays, quite a large number of operas, a large number of novels, and some short story collections. He was too controversial to ever be awarded something like the Nobel Prize, but at the beginning of Italy’s 20th century period he was one of the most popular people in Italy. Almost everyone had an opinion about him and almost everyone had heard of him.

His work combines various pagan, vitalist, and Nietzschean forces, and he was heavily influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche and his philosophy. Some of his works were banned on grounds of public morals both in translation abroad and in Italy per se. The Flame of Life was one of his more ecstatic and Byronic celebrations of life. The Triumph of Death was another of his works, and The Maidens of the Rocks was another one, and a poem called Halcyon which was part of an interconnected series of poems five in number. He was going to write a larger collection than this, but those were the ones that got done. Also, he celebrates the Renaissance period and the period of Italian greatness when Italian civilization became synonymous with Western civilization and indeed looked to put its stamp upon world civilization.

So, D’Annunzio brought together a wide number of strands which supervened in Italian politics and culture since the unification of Italy under Garibaldi in the 19th century. Like Germany, Italy was unified as a modern European nation-state quite late in the day, and a triumphant sense of national vanguardism, identity, and pressure and force was always part of D’Annunzio’s ideology.

Superficially, it seems strange that you have artists of extreme individuality like Maurice Barrès in France in the 1890s who wrote a book called The Cult of the Self (Le Culte du Moi) along Nietzschean and Stirnerite lines and professed a very extreme individuality who were also ardent nationalists. This is because this cult of the heroic individual and this cult of the masculinist and this cult of the superman and the cult of the pagan individual that D. H. Lawrence’s novels in English literature could be said to be part and parcel of at least at one degree went hand in glove with the belief in national renaissance and national glory. The great individual was seen as the prototype of the great man of the nation and was seen as a national leader in embryo whether or not the work took on any political coloration at all. So, what appears to be a collective doctrine and what appears to be an individualistic doctrine marry up and come together and cohere in various creative ways and this was part of the creative tension of the late 19th century.

D’Annunzio is a 19th-century figure who explodes into the 20th century by virtue of mechanized politics. Debts and the pursuit of various people to whom he owed money because of his extraordinarily lavish and aristocratic lifestyle led D’Annunzio to live in France at the time of the outbreak of the Great War, but he soon hurried back to Italy in order to demand his entry into the Great War on the Allied or Western or Tripartite side. Of course, in the Great War, Italy fought with the Western allies, with France, with Russia and Britain against Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman or Turkish Empire in the convulsive conflict which people who lived through it thought would be the war to end all wars.

D’Annunzio had an extraordinary war. He joined up when he was around 50 years of age and gravitated towards the more aristocratic arm of the three that were then available. It’s noticeable that the war in the air attracted a debonair, an individualistic, and an aristocratic penchant. Figures as diverse as Goering in the German air force and Moseley in the British air force and D’Annunzio in the Italian air force all fought a war that in its way had little to do with the extraordinarily mechanized armies that were fighting on the ground.

You had this strange differentiation between massive armies and fortifications of steel with tunnels turning the surface of the Earth like the surface of the moon down on the ground until tanks were developed that could cut through the sterile nature of the attrition of the front – a very static form of warfare from 1915 until the war’s end in 1918 – and yet above it you had this freedom of combat, this freedom in the air with biplanes which were stretched together from canvas and wood and wire and were extraordinarily flimsy by modern standards, without parachutes for the most part, and where the men used to often fire guns and pistols at each other before machine guns were actually fixed to the wings so they can actually fly on each other in flight.

There was a cult of chivalry on all sides in the air which really didn’t superintend on the massive forces that were arrayed against each other on the ground, and this enabled a spiritual dimension to the war in the air that was commented upon by many of the men who fought at that level. This in turn reflected the sort of joie de vivre and the belief in danger and force that aligned D’Annunzio with the futurist movement of Marinetti and with many anti-bourgeois currents in cultural and aesthetic life at the time.

As the 19th century drew to a close there came a large range of thinkers and writers such as Maurice Barrès in France, such as D’Annunzio and Marinetti in Italy who were appalled by the sterility of late 19th-century life and yearned for the conflicts which would engulf Europe and the world in the next century. You have a situation where each era – such as the one we’re in in the moment – precedes what is coming with all sorts of conflicted and heterogeneous ideologies which only become clear once you’ve actually lived through the subsequent period. Between about 1880 and 1910 an enormous ferment of opinion with men as voluble as Stalin and Hitler being in café society parts of Europe planning what was to come or what they might be alleged to be part of at certain distant times. Men often dismissed as cranks and dreamers and wayfaring utopians on the margins of things who were destined later on to leap to the center of European culture and expectancy.

There’s a great story that the French writer Jean Cocteau says about Lenin. He met the man at a party in a house in France in 1910, and the man was sitting in the house. In other words, he was looking after it while someone was away. And Cocteau said to his friends, “And who are you?” and the man said, rather portentously, “Men call me Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. I am known as Lenin. I am plotting the destruction of the Russian Czarist regime, and I am going to wipe out the entire ruling class in Russia and install a proletarian dictatorship.” Straight out without any intermission! And they all said, “Well, that’s very interesting! One applauds you, monsieur!” He said, “What are you doing at the moment?” And he said, “I edit a small journal called Iskra, The Spark, which is the beginning of the ferment of the revolutionary energies which are coming to Russia and eventually the world!” And they thought, “Well, this is interesting!” You know. How many subscribers had Iskra had at that moment? 400? 40? 4? And yet, of course, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov would emerge from the chaos of post-revolutionary Russia, as Russia struggled from its defeat by the Germans in the First World War, to become the leader of the world’s first and most toxic revolutionary state. Nothing is predictable in this life.

When the German high command sealed the Bolshevik leadership, including Vladimir Ilyich, in a train and sent it through their occupied territories into Greater Russia in the hope that it would just create more chaos and foment more distress, they had no idea that this tiny, little faction would seize maybe 11-12% of parliamentary votes and would then take over a weakened state with a small paramilitary force. Because the Bolshevik Revolution was in no sense a social revolution as its proselytizers claimed for upwards of half a century afterwards. It was an armed coup by the armed wing of a tiny political party.

There’s a famous story that Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin all slept in one room with newspaper on the floor the day after the revolution, and Lenin said, “Comrades! A very important thing has happened! We have been in power for one day!” And the amount of Russia that they controlled, of course, was extraordinarily small.

So, one has to realize that this ferment of ideas, Right, Left, and center, religious, aesthetic, and otherwise, occurred between 1880 and the beginning of the period that led up to the Great War and out of which most of the modern ideologies of the first half to first three quarters of the 20th century emerged.

D’Annunzio largely created Italian Fascism. Nearly everything that came out of the movement led by Mussolini at a later date originated with him and his ideas. The idea of the man alone, set above the people who is yet one of them, the idea of a squad of Arditi, people who are passionate and fanatical and frenzied with a stiff-arm Roman salute who are dressed in black and who are an audience for the leader, as well as security for the leader, as well as a prop to make sure particularly the masses and crowd when they are listening to the leader go along with what the leader is saying, as well as a sort of nationalist chorus . . . All of these ideas come from D’Annunzio and his period of forced occupation and Italianization of the port of Fiume.

So, there’s a degree to which this possible assassination attempt against D’Annunzio in 1922 which puts him out of commission for a certain period was in its way emblematic of the fact that he was a key player in Italian politics. He was the only rival for the leadership of what became known as the extreme Right with Mussolini. Certain Fascists at times looked to D’Annunzio when the fortunes of their own movement dipped.

It’s noticeable that during the occupation of Fiume, which we’ll come onto a bit later in this talk, D’Annunzio thought that there should be a march on Rome and rushed to align himself with the Fascists and other forces of renewal and nationalistic frenzy in Italian life after Italy’s victory as part of the winning side during the Great War. That march never happened, but of course was to happen later when Mussolini and other leaders had engaged in deals with the existing Italian establishment. The Mussolinian march on power was a coup with the favor of the state it was taking over rather than a coup against the nature of the state which was hostile to what was coming. So, in a way, the Italian march was leaning on a door that was already open and only forces like Italian Communism and so on, which are outside the circle of the state and its reference to political resources, opposed what the Mussolinians then did.

There is this view that Mussolini and the Fascist movement regularized and slightly de-romanticized the heroic conspectus of what D’Annunzio stood for. D’Annunzio was an artist and when Fiume, which is part of Croatia, was taken over by his militia between 1,000 and 3,000 strong in the early 1920s, because it had an Italian majority and he wished to secure it for Italy in relation to the post-Great War dispensation, he made music the foundation-stone of the City-State of Fiume. There’s a degree to which this is part of the extreme rhetoricism and aestheticism that D’Annunzio was into. This is not practical politics to make music your cardinal state virtue and to create idealized state assemblies with a minimum of chatter, because D’Annunzio believed not in parliamentary democracy but in a form of civics whereby each participant of the nation was represented. That’s why in Fiume he begins the prospect of a corporate state, and he begins an assembly or a vouchsafe body for farmers, for workers, for employers, for the clergy, for industrialists, and so on in a manner that Mussolini would later take over because most of what the Mussolinians did was actually pre-ordained for them by D’Annunzio’s moral and aesthetic coup d’état.

D’Annunzio believed that life should be brief and hectic and as heroic as possible and that the Italians should be based upon the principles of the ancient Roman Empire and of the Renaissance. In other words, he quested through the Italian period of phases of thousands of years of culture for the highest possible spots upon which to base Italy in the 20th century. At his funeral which occurred in 1938, Mussolini declared that Italy will indeed rise to the heights of which he wished and D’Annunzio always wanted Italy to be on the winning side and to be a major player in international and European events.

The truth of the matter, of course, is that Italy for most of its 20th-century existence has not been a minor player, but has not been amongst the major players, has been amongst the second-tier powers of Europe in all reality, and there’s a degree to which many Italian military adventures which were initiated by Mussolini fell back on German tutelage and support when they run into difficulties, although those imperial adventures in Ethiopia and elsewhere were supported by D’Annunzio, who became very close to the regime when he realized that they wished to set up a neo-Italian empire along Romanist lines.

D’Annunzio also supported Mussolini leaving the League of Nations, and he believed oppressed Italians who lived outside of Italy proper should be included, in an irredentist way, in Italy proper. Irredentism is the idea that if you have people of your own nationality who live outside the area of the nation-state you should incorporate them in one way or another, by conquering intermediate territory or by agglomerating them back into a larger federation. This is the idea of having a greater country: Britain and the Greater Britain, Italy and the Greater Italy, Russia and the Greater Russia, and so forth.

There’s a degree to which D’Annunzio aligned himself with the forces of conceptual modernism without being a modernist himself. In a literary and linguist way, he was very much a Romantic of the 19th-century vogue, but his sensibility was extraordinarily modern.

In contemporary Italian literature, there is no easy and defined position about D’Annunzio. One would have thought that a man who died in 1938 and his political career was over by 1922 to all effects would be historical now. D’Annunzio is still a live topic in Italy and is still controversial not least because of the sort of Byronic “sexism” of his novels, poetry, and plays, a screen play in one case and librettos for various operas. Also the fact that he’s such a precursor of Italian Fascism to the degree that he is regarded as the first Duce, the first leader, the first fascistic leader of any prominence that Italy had before Mussolini that his reputation is still extremely divisive in Italian letters. Most of the center and Left when D’Annunzio’s name is mentioned in Italy today still go, “Ahhhh nooo!” If you can imagine a sort of fascistic D. H. Lawrence who later had Moseley’s career up to a point, that’s the nearest you get to a British example of a man like D’Annunzio. Lawrence, of course, would have a completely different reputation had he endorsed the politics of Nazi Germany in the way that he sort of endorsed, slightly, the politics of fascistic Italy. In some ways, Lawrence, who was sort of made into a cult by the Cambridge literary criticism of F. R. Leavis in Britain and I. A. Richards in the United States post-Second World War, would never have preceded to those heights had he endorsed certain political causes of the ’30s and ’40s. So, in a sense, his early death was fortuitous in terms of his post-war reputation.

Robinson Jeffers, the American poet and fellow pagan with whom Lawrence communicated during his life quite manfully, fell into desuetude after the Second World War for, not advocating pro-Axis sympathy as a neutralist America, but by advocating isolationism. Isolationism is, of course, an ultra-nationalist position in American life. The belief that America should not involve itself in the teeming wars of the 20th century, what Harry Elmer Barnes calls perpetual war for perpetual peace, but that America should retreat to its own borders and not concern itself with events outside America, occasionally looking outside to the Caribbean and Latin America. But Lawrence would have gone the same way as Jeffers had he had a career like D’Annunzio and had he endorsed some of the positions that D’Annunzio did.

D’Annunzio’s position on Fascism outside of Italy was more contradictory because he was a nationalist first and last and ultimately it was Italy’s destiny that concerned him not that of other countries. He was in favor of leaving the United Nations, but rather like Charles Maurras in France he was a nationalist in some ways more than a Fascist and his nationalism was proto-fascistic even though he provided much of the aesthetic coloring for what later came in the Italian political dictatorship.

D’Annunzio was a man of great individual courage — it has to be said — and combined the ferocity of the warrior and the sensibility of the artist. One of his most famous individual coups was this 700-mile round trip in an airplane to drop pamphlets of a sort of pro-Western/pro-Italian type on Vienna, which is still remembered to this day. Another of his feats was attacking various German boats with small little motor-powered launchers, something that prefigures a lot of modern warfare where great, large hulking liners and aircraft carriers can be disabled by small boats that speed around them. The principle of guerrilla type or asymmetric warfare whereby much larger entities can be hamstrung by their smaller, Lilliputian equivalents or rivals. Again, this sort of special forces warfare in a way, whether in the air or on the sea, was part and parcel of D’Annunzio’s aesthetic and ethic of life.

D’Annunzio was a man of great individual courage — it has to be said — and combined the ferocity of the warrior and the sensibility of the artist. One of his most famous individual coups was this 700-mile round trip in an airplane to drop pamphlets of a sort of pro-Western/pro-Italian type on Vienna, which is still remembered to this day. Another of his feats was attacking various German boats with small little motor-powered launchers, something that prefigures a lot of modern warfare where great, large hulking liners and aircraft carriers can be disabled by small boats that speed around them. The principle of guerrilla type or asymmetric warfare whereby much larger entities can be hamstrung by their smaller, Lilliputian equivalents or rivals. Again, this sort of special forces warfare in a way, whether in the air or on the sea, was part and parcel of D’Annunzio’s aesthetic and ethic of life.

It’s noticeable that in modern warfare the notion of individualistic courage never goes away, but war is so much reduced to the big battalions, so much reduced to raw firepower, and so much reduced to the expenditure of force between massive units that are industrially arranged against each other that individual combat often becomes slightly meaningless. But it gravitates to certain areas: the sniper, the elite boatman or frogman, the elite warrior in the air becomes the equivalent of the lone warrior loyal to sort of ideologies of warriorship in previous civilizations and you can see this in the way that these men think about themselves and think about their own missions.

In a previous talk to a gathering such as this, I spoke about Yukio Mishima and the ideology of the samurai based upon the cult of bushidō in Japan. This is the idea of almost an aesthetic martial elitism who sees itself both in artistic and religious terms and yet is also a morality for killing. All of these things are provided for in one package. A man like D’Annunzio did incarnate many of these values in a purely Western and Southern European sense.

D’Annunzio’s war record was such that he won most of the medals, including the gold medal, the equivalent to the Victoria Cross, and he won silver crosses which are a slightly lesser medal and a bronze cross. He was also awarded other medals including a British military cross, because of course he was fighting on the British and Allied side in the First World War.

One of his points that was made by Mussolini and other Italian nationalists was that Italy did not get from the First World War the post-war dispensation which they expected. This is true of almost everybody essentially, but it’s certainly true that Italy was thrust back into the pack of secondary powers by the major victors in the First World War: Britain, the United States, and France. Their role in the post-war peace, which of course was a highly torturous and afflictive peace upon the defeated Germany, was to have major repercussions on the decades that followed. That peace had little to do with what Italy wanted. One of the reasons for the occupation of what later became part of Yugoslavia by paramilitary Italian arms led by D’Annunzio was his dissatisfaction with Italy’s role at the table after the Great War.

His belief in “One Italy” and “Italy Forever” and “where an Italian felt injustice, Italy must be there to protect them,” this belief that caused thousands of men to rise up and come to D’Annunzio’s banner . . . When he began this assault on Fiume he had about 300 men with him. By the time it was over he had about 3,000.

On the internet you can see in 1921 enormous crowds within the city, almost everyone in the city is there cheering on D’Annunzio, who engaged in this increasing rhetoric from the balcony. Indeed, the Mussolinian stage scene whereby the dictator figure, or dictator manqué in this case, addresses the masses who look up to a balcony is all constructed and lit up by stage lights and that sort of thing is all part and parcel of D’Annunzionian theater. D’Annunzio would always ask the crowd rhetorical questions: “Do you love Italy?” And there’s this response, “Yes!” And then there will be another response from D’Annunzio and then another response. If somebody gives a contrary sort of response in the crowd, because these are enormous mass meetings which are difficult to control, he has squads of men dressed in black positioned in the crowd who can sort various malefactors out. This combination of support with a degree of psychological bullying is all part of the festival of nationalistic spirit that somebody like D’Annunzio believes in building almost as a theatrical event where you let the crowd down over time by stoking them up into more and more responses and you allow moments where the crowd just bellows and howls in response until they are replete and exhausted and the man strides back to the edge of the balcony to begin a speech. All of these are things that Mussolini would later develop. So, D’Annunzio in a sense provides a theatrical package for what becomes Italian and Southern European radical nationalism at a later time.

He didn’t live to see the full extent of Italian Fascism, but he had to be kept sweet by the Mussolinian government. Mussolini was once asked by a fellow Fascist leader in Italy what he thought of D’Annunzio and why he behaved in relation to him in the way that he did and he said, “When you have a rotten tooth there are two solutions. You either pull it out violently or you pack it with gold, and I have decided on the secondary option with D’Annunzio.” So, D’Annunzio was given a large amount of money by the Italian state to swear off political involvement after 1922, something that makes the possible assassination of him, attempted assassination, in 1922 rather interesting and mysterious. No one knows whether that was an attempted assassination or not. It’s quite obscure in the historical literature, but it certainly put D’Annunzio back and it put him out of commission for the entire period that the Mussolinians marched to power quite literally.

Later on, he would awarded the leadership of the equivalent of the Society of Arts; he would be awarded a state bursary which paid for a collected edition of his works that was printed and published by the Italian state itself and was available in all libraries and schools and universities; he was awarded numerous medals and forms of honor; his house was turned into a museum which still exists and is one of the major tourist sites in contemporary Italy where planes that he flew in the Great War are restored and can be looked at, boats which he used in the Great War are restored and can be looked at, as well as a library, a military research institute, and all sorts of photographs from the period. There is a large mausoleum to him, which is a contemporary Italian monument of significance. He’s compared in some ways to Garibaldi, the figure in the 19th century with his Redshirt movement that helped unite Italy as a warring, patchwork quilt of a nationality into one overall nation-state along modern lines.

D’Annunzio is one of these synthetic and syncretic figures who combine in themselves several different lives: lover, soldier, aesthete, political warrior, writer, artist. He combined four or five lives in one particular lifespan and brought together all sorts of confluences in the Italian politics of his day.

When he was elected to the senate as an independently-minded conservative at the end of the 19th century, he had no real sectarian politics at all except a belief in conservatism and revolution as he described it. He later moved across the parliament floor to join the Left in a particular vote that broke a deadlock in Italian politics of the time and was regarded as the creation of a new synthesis where part of the Right joined the Left and then split off again to form a different part of the Right or could at least be said to be a precursor of those same developments.

Mussolini, of course, was sat with the socialists and was a socialist deputy and was part of the bloc that favored nationalists rather than international solutions as part of Italian socialism. This is why during the First World War or the run-up to it the Axis within Italy which favored Italy’s involvement in the war against strong pacifists and internationalist currents that wanted to keep Italy out of the European conflagration lost out and one of the key proponents were the Futurists, D’Annunzians, and proto-Fascists from the bosom of the Italian Socialist Party, who combined a degree of nationalism with quite straight-forward Italian social democracy of the period.

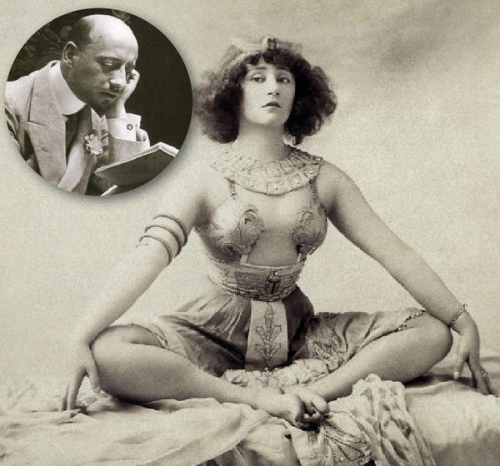

D’Annunzio married and had, I think, three children, but was well known for a very torrid love life consisting of a great string of mistresses. He had dalliances with two extraordinarily notorious Italian actresses, both of whom he wrote plays for and operettas. He was well regarded as a sort of bon viveur and a figure about whom myths constellate. Even to this day D’Annunzio is regarded as a cad and egotist and a scoundrel in many circles because that is how he presented himself and the male ego in his literary works.

How original D’Annunzio was is difficult to quantify. His philosophical debt is to Nietzsche, his literary debt is to the Italian literary tradition which essentially goes back to the Renaissance. His great use of style – he was one of the greatest stylists of the modern Italian language – has made sure that his books are in print to this day, but he still remains a controversial figure because of the politics with which he was associated.

How far and aesthetically motivated his desire for dictatorship could work in practice and would not implode because of impracticality is a moot point, but D’Annunzio certainly gave a brio to early Italian experimental and Right-wing politics. He gave a poetic license to authoritarianism which helped make Southern European Fascism extraordinarily culturally interesting long into the Mussolinian regime. It is interesting to notice how many intellectuals and artists aligned with the movement in Italy and made peace with its government.

Also, the use of oppression, which is very light-handed in Italy was part and parcel of this doctrine of brio and of ubiquitousness and the use of style. In some ways it was a very style-conscious regime, an exercise in theater. Many of the post-war historians of Fascist Italy talk about it as being a sort of theatrical society with Mussolini as almost a political actor in some respects. This is very much in the D’Annunzionian tradition which he laid down at Fiume.

Fiume. They conquered this city which is part of Croatia but had an Italian majority at that time. The Italian governor refused to fire on D’Annunzio and his paramilitaries when they entered the city. They took it over and created a sort of corporate state within the state, heralding its creation as a city-state. They said it left the League of Nations, which they refused to recognize because Italians were being exploited by the remit of the League of Nations, the forerunner of the United Nations. They created this sort of aesthetic, fascistic junta that was part theater, part hyper-reality, and part just a governing civic administration with a military arm. Gradually, the forces of reaction, as D’Annunzio would have called them, attempted to call Fiume to account. The Allies chafed against its continued existence as an independent military satellite and city-state. Italian nationalists and others may have flocked to it, including Leftists like anarchists and syndicalists who admired D’Annunzio’s brio and sort of cult of machismo and Italian irregular adventurism which has a medieval tradition, certainly an antique Italian tradition with many admirers from across the spectrum. Yet in the end the Italian state was forced to take action and fired on Fiume, and Italian naval vessels shelled the city. There was a declaration of war, somewhat absurdly, against Italy by D’Annunzio where 3,000 men took on a nation-state that could put tens of thousands of men in boats and planes into play.

Eventually, of course, when the shelling became too bad he said that he could not allow the aesthetic construction of the city to be damaged and so he handed it over to prior Italian power and an international settlement, which involved Yugoslav control eventually coming in.

But Fiume represented a direct incursion of fantasy into political life because there is a degree to which D’Annunzio combined elements of performance art in his political vocabulary. There’s no doubt that he thought of politics as a form of theater, particularly for the masses, and this is because he was an elitist, because as an elitist he partly despised the masses except as the voluntarist agents of national consciousness. He theatricalized politics in order to give them entertainment without allowing them any particular say in what should be done. This idea of politics as performance art with the masses onstage but as an audience, an audience that responded and yet was not in charge, because there’s nothing democratic about D’Annunzio from his individualistic egotism as an artist all the way through to his sort of quasi-dictatorship of Fiume. He represented a particularly pure synthesis and the violence that was used and so on was largely rhetorical, largely staged, largely a performance, partly a sort of theater piece.

In post-modernism, there’s this idea that artists crash cars, burn buildings, and exhibit what they’ve done in gallery spaces and that sort of thing as an attempt at an incursion of reality into the artistic space. D’Annunzio did it the other way around. There was an incursion not of reality into the artistic space, but of artistry into the political space and he went seamlessly from writing these novels of male chauvinism and excess and erotic predatoriness and Italianate brio to running a city-state almost without running any sort of marked gap between the two moments. In the chaotic situation of post-Great War Italy and its environs, he found a template upon which his dreams – his critics would say his bombastic dreams – could be lived out and there is a sort of dreamer of the day to D’Annunzio, but he was also quite hard-headed and practical and most of his political exercises in chauvinism came off unlike many dreams that remain in the scrap-heap of political alternative.

So, in a sense, D’Annunzio’s greatest novel was the creation of what became the Italian Fascist state, which until it was defeated externally and internally was one of the most stable societies modern Europe has seen.

This belief in a nation’s ability to renew itself by bringing various tendencies that are abroad within it together and synthesizing them through the will of one man who must be a visionary of one sort or another is part and parcel of D’Annunzio’s legacy. It’s why he can’t just settle down and be an artist. It’s why, indeed, his post-war Italian reputation is so mixed, because he can’t be divorced from the politician and the statesman that he indeed was.

It’s interesting to think how the world would have developed if European nationalities would have increasingly fallen under the sway of these cross-bred artistic, hybridized figures. Nearly all far Right, and some far Left, leaders have these sorts of characteristics: extreme individuality, colorful backgrounds in the past, a sort of anti-bourgeois sentiment, a refusal to live a conventional life completely, the belief in new forms, and the construction of new forms of modernity almost in a haphazard and experimental way. These people only get their chance during war, economic breakdown, chaos, and revolutionary change when everything comes up for grabs and there is a new dispensation abroad. But it is noticeable that these people do get their chance when these events occur.

It’s also noticeable that the post-war period, very much in Western Europe at any rate, is dominated by two factors. One is the Cold War, which congeals the continent into two rival blocs under partial American domination in the Western sector and direct Soviet domination, of course, of the Eastern bloc, but the second is a fear of contamination through change which is underpinned by the desire to keep market economies functioning at a tolerable level of sufficiency. It’s quite obvious that there is a terror abroad in the Western liberal landscape about what would occur if there is an economic collapse. Not just a slow-down, not just a depression or recession or series of recessions that ends in a Japanese-like depression which can go on for 20 years where you don’t grow at all, zero growth, but something much more devastating than that. An actual crack and crash in the system itself. Because with mass democracy there is no knowing what sorts of demagogues and what sorts of visionaries people might start voting for in small or larger numbers when such a crash occurs and when they literally can’t pay their bills and so D’Annunzio came out of an era of chronic instability and fashioned that instability to his own liking and making, because Fiume was the prototype for a state.

Indeed, in ancient Southern Europe, the city-state was the forerunner of the nation-state. He was attempting to do with an Athens or a Sparta of his own imagination and will and intellect what later became Mussolinian Italy on a nation-wide scale and if Italy had succeeded in carving out an empire for itself in North Africa and further afield in modernity it would have been the basis for an Italian empire because the nature of these things is to expand. That kind of power always chafes against the possibility of restriction and unless it comes up against a greater external force it will always chafe against it in an attempt to push it back and gain greater suzerainty thereby. That’s inevitable. Even under mercantilist pressure, the British Empire adopted that sort of course for many centuries until, if you like, the stabilization of the 20th century and the loss of empire in mid-century.

So, what we’ll see if there are enormous economic crashes in the near to distant future the sort of politics that D’Annunzio represented come back. No one knows what form it will take because things never repeat themselves. They only seem to, because the syntheses that are created are always new and always original. But this crossover between theater, literature, lived demagoguery, the martial and martinet spirit and the spirit of the lone adventurer, the spirit of the marauder, the spirit of the armed troubadour is very much a part and parcel of what D’Annunzio stood for. His present notoriety in contemporary Italy is because he is a man of so many parts and such a threatening overall presence – threatening in the sense that Italian Fascism, although much more integrated into the historical story than fascisms elsewhere, is still very much a devilish shadow cast over the post-Italian polity that all are aware of and yet few dare to speak of with any courage or glory.

D’Annunzio believed that courage and glory and heroic belief in national affirmation were the very principles of life. His example, so out of kilter with contemporary reality, is interesting and refreshing. D’Annunzio is like a sort of Julius Caesar crossed with Jack London. There’s a strange amalgam of tendencies living out of one man and it is remarkable that he could bring that union or fusion with such panache and charisma. Probably it was the military career that he had during the Great War that enabled him to step out of the literary study and into the statesman’s counting house, onto the statesman’s balcony. Without that experience in the Great War I doubt he would have had the following to achieve that. But D’Annunzio represents this strange amalgam in European man of the restless adventurer and the poet, of the dreamer and the activist, of the stoic and the fanatic.

The city-state that he created at Fiume provided for religious toleration and atheism, because of course as a Nietzschean D’Annunzio was an atheist and was not religiously motivated even though the paganism of his literature harks back to the neo-pagans of the Renaissance and to the Roman Empire of antiquity.

The real source of origin for D’Annunzio’s moral equipment has to be ancient Rome and as I look about me in this society there are an enormous number of novels, aren’t there, devoted to ancient Rome? Quite populist, mainstream fare. And it’s quite clear that there is a fascination with Europe’s past and with its authoritarian, bellicose, adventurist, and escapist past and possibly through the mirror image of intermediaries like D’Annunzio there may be a link to a new and more invigorating Europe of adventure and of skill and of destiny and of the will of the desperado and of the man who will never take no for an answer and of the man who would chant these slogans that Achilles uses in Homeric epics to the crowd and hear the Arditi chant them back again and that these are echoes which you can still hear and are still not entirely dormant in Europe at the present time as the Balkan Wars of the 1990s proved in their bloody way. There’s a degree to which these prior giants of Europe are sleeping but are not at rest and there is always the fear in contemporary liberal establishments that these figures and the forces that they represented will be catalyzed yet again in the future by new visionaries and by new leaders and by new literati and by new sources of inspiration who combine the individual and the collective, combine the national and the quietude of the man alone and combine the Renaissance and the ancient world in a new pedigree of what it means to be a man, what it means to be an European and what it means to have a destiny in the modern world.

D’Annunzio preconfigured much of European history until at least the late 1940s, which bearing in mind that he was born towards the middle of the 19th century was quite an achievement. It is not to say that figures who are alive now are not in themselves creating the synthesis for forces that will emerge in the next 50 years.

Thank you very much!

Related

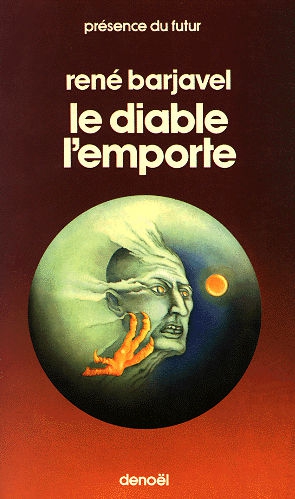

L’intérêt de Ravage et de Le Diable l’Emporte est de constater qu’en à peu près cinq années d’écart, le propos de Barjavel ne change pas, mais s’aggrave. Dans les deux cas, il décrit l’assimilation du « progrès » au « développement » comme cause de l’acculturation, et de l’impotence des individus. La société d’après-guerre, en pleine reconstruction et porteuse des futures Trente Glorieuses mais aussi de l’hégémonie du Marché, ne fait que confirmer la vision que nourrissait Barjavel dans son premier roman. En effet, dans son dernier roman, Barjavel explore plus volontiers l’utilitarisme de la société de consommation, ou les choses de la nature sont transformées pour répondre aux exigences du Marché, sous couvert d’intentions humanitaires bien sûr.

L’intérêt de Ravage et de Le Diable l’Emporte est de constater qu’en à peu près cinq années d’écart, le propos de Barjavel ne change pas, mais s’aggrave. Dans les deux cas, il décrit l’assimilation du « progrès » au « développement » comme cause de l’acculturation, et de l’impotence des individus. La société d’après-guerre, en pleine reconstruction et porteuse des futures Trente Glorieuses mais aussi de l’hégémonie du Marché, ne fait que confirmer la vision que nourrissait Barjavel dans son premier roman. En effet, dans son dernier roman, Barjavel explore plus volontiers l’utilitarisme de la société de consommation, ou les choses de la nature sont transformées pour répondre aux exigences du Marché, sous couvert d’intentions humanitaires bien sûr. L’apocalypse en elle-même, ou son caractère imminent et inévitable, permet de contempler l’échec de l’homme moderne, et de la modernité telle que la conçoivent les grands objecteurs de conscience nous expliquant qu’on était forcément plus bête avant. Le Diable l’Emporte va plus loin que Ravage en cela, puisqu’il fait étalage de la course à l’armement dans toute sa dimension autiste et autodestructrice, outre les manipulations du vivant, mais c’est son premier roman où la conclusion est la plus acerbe. Barjavel joue de l’opposition Progrès/Décroissance (pour simplifier les choses) tout au long de Ravage, et clôt son roman sur l’épanouissement d’une société nouvelle revenue aux us et coutumes des anciens, proche en cela d’un romantisme barrésien, quoiqu’exacerbé, puisque la mécanique elle-même est rejetée par le protagoniste vieillissant et chef d’une lignée à la fin de l’histoire. Pareil romantisme est perceptible dans l’Enchanteur, où le style de Barjavel traduit une certaine exaltation a faire vivre sous sa plume l’imaginaire arthurien, comme un véritable hommage et non par atavisme.

L’apocalypse en elle-même, ou son caractère imminent et inévitable, permet de contempler l’échec de l’homme moderne, et de la modernité telle que la conçoivent les grands objecteurs de conscience nous expliquant qu’on était forcément plus bête avant. Le Diable l’Emporte va plus loin que Ravage en cela, puisqu’il fait étalage de la course à l’armement dans toute sa dimension autiste et autodestructrice, outre les manipulations du vivant, mais c’est son premier roman où la conclusion est la plus acerbe. Barjavel joue de l’opposition Progrès/Décroissance (pour simplifier les choses) tout au long de Ravage, et clôt son roman sur l’épanouissement d’une société nouvelle revenue aux us et coutumes des anciens, proche en cela d’un romantisme barrésien, quoiqu’exacerbé, puisque la mécanique elle-même est rejetée par le protagoniste vieillissant et chef d’une lignée à la fin de l’histoire. Pareil romantisme est perceptible dans l’Enchanteur, où le style de Barjavel traduit une certaine exaltation a faire vivre sous sa plume l’imaginaire arthurien, comme un véritable hommage et non par atavisme.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

« Le difficile est de faire le gris » estimait Aragon à propos du travail du romancier : ne pas grossir les traits mais ramener les individus à des proportions qui sont celles de la vie du lecteur. Il semble bien que Michel Déon fasse sien dans Les gens de la nuit l’art poétique de l’auteur des Beaux quartiers, tant son narrateur, fantôme perdu dans les brumes mélancoliques du Paris de l’après-guerre, tient du personnage d’Aurelien, cet ancien combattant de la guerre de 14 écrasé par le « nouveau mal du siècle » que diagnostiqua Antoine Blondin dans son article « Cent ans de Mal du Siècle ».

« Le difficile est de faire le gris » estimait Aragon à propos du travail du romancier : ne pas grossir les traits mais ramener les individus à des proportions qui sont celles de la vie du lecteur. Il semble bien que Michel Déon fasse sien dans Les gens de la nuit l’art poétique de l’auteur des Beaux quartiers, tant son narrateur, fantôme perdu dans les brumes mélancoliques du Paris de l’après-guerre, tient du personnage d’Aurelien, cet ancien combattant de la guerre de 14 écrasé par le « nouveau mal du siècle » que diagnostiqua Antoine Blondin dans son article « Cent ans de Mal du Siècle ».

In Pallieter valt De Pillecyn ook het fascisme en het kolonialisme aan. Als pacifist verwerpt hij het wapengekletter van de fascistische leider Benito Mussolini en vanuit zijn democratische inborst fulmineert hij ook tegen het Belgische nationalisme met zijn fascistische sympathieën. Maar tegelijk had De Pillecyn een gebroken verhouding met de democratie als systeem. De totstandkoming van het Frans-Belgisch Militair Akkoord ontnam De Pillecyn het geloof in de eerlijke werking van de parlementaire democratie: 'De Regeringen, onze Theunis net zo goed als Poincaré, zorgen er eerst voor dat zij een meerderheid hebben die op voorhand ja heeft gezegd.' Rik Van Cauwelaert beschrijft in zijn bijdrage hoe De Pillecyns afkeer van het parlementarisme alleen maar toenam, en hoe de journalist en auteur daarin bevestigd werd door het gebrek aan ruggengraat bij vele Vlaamse volksvertegenwoordigers tegenover de opstoot in het Belgische nationalisme. Waar situeert De Pillecyn alias Pallieter zich nu ideologisch? Was hij een linkse jongen zoals Van Neygen in de titel van zijn bijdrage schrijft, en zoals zijn antimilitarisme, antifascisme en antikolonialisme doen vermoeden? Was hij een linkse die de 'afkeer voor het parlementarisme [...] naar de collaboratie leidde', zoals Rik Van Cauwelaert stelt? Of behoorde hij door dit amalgaam tot de mensen die de historicus Otto-Ernst Schüddekopf noemde: 'Linke Leute von rechts' (Linkse mensen van rechts)?

In Pallieter valt De Pillecyn ook het fascisme en het kolonialisme aan. Als pacifist verwerpt hij het wapengekletter van de fascistische leider Benito Mussolini en vanuit zijn democratische inborst fulmineert hij ook tegen het Belgische nationalisme met zijn fascistische sympathieën. Maar tegelijk had De Pillecyn een gebroken verhouding met de democratie als systeem. De totstandkoming van het Frans-Belgisch Militair Akkoord ontnam De Pillecyn het geloof in de eerlijke werking van de parlementaire democratie: 'De Regeringen, onze Theunis net zo goed als Poincaré, zorgen er eerst voor dat zij een meerderheid hebben die op voorhand ja heeft gezegd.' Rik Van Cauwelaert beschrijft in zijn bijdrage hoe De Pillecyns afkeer van het parlementarisme alleen maar toenam, en hoe de journalist en auteur daarin bevestigd werd door het gebrek aan ruggengraat bij vele Vlaamse volksvertegenwoordigers tegenover de opstoot in het Belgische nationalisme. Waar situeert De Pillecyn alias Pallieter zich nu ideologisch? Was hij een linkse jongen zoals Van Neygen in de titel van zijn bijdrage schrijft, en zoals zijn antimilitarisme, antifascisme en antikolonialisme doen vermoeden? Was hij een linkse die de 'afkeer voor het parlementarisme [...] naar de collaboratie leidde', zoals Rik Van Cauwelaert stelt? Of behoorde hij door dit amalgaam tot de mensen die de historicus Otto-Ernst Schüddekopf noemde: 'Linke Leute von rechts' (Linkse mensen van rechts)?

« La France résistera, dit-il. Les Français sauront résister, sans devoir étaler un héroïsme exceptionnel, sans même avoir besoin d’un sursaut collectif d’orgueil national.» «Keep calm and carry on, sois calme et va de l’avant, poursuit Houellebecq. Oui, nous ferons ainsi (même si – hélas – nous n’avons pas un Churchill pour guider le pays).» L’écrivain juge que si les Français sont plutôt «dociles» et se laissent gouverner facilement, «cela ne veut pas dire que ce sont des imbéciles». Leur défaut est un défaut de mémoire, d’où la nécessité de la leur rafraîchir.

« La France résistera, dit-il. Les Français sauront résister, sans devoir étaler un héroïsme exceptionnel, sans même avoir besoin d’un sursaut collectif d’orgueil national.» «Keep calm and carry on, sois calme et va de l’avant, poursuit Houellebecq. Oui, nous ferons ainsi (même si – hélas – nous n’avons pas un Churchill pour guider le pays).» L’écrivain juge que si les Français sont plutôt «dociles» et se laissent gouverner facilement, «cela ne veut pas dire que ce sont des imbéciles». Leur défaut est un défaut de mémoire, d’où la nécessité de la leur rafraîchir. L’actualité, c’est-à-dire le Spectacle, abonde en déclarations et évènements dont l’accumulation suscite une zone d’incertitude entre le mensonge, l’oubli et l’indifférence, sur laquelle se fonde la politique, autre nom du Spectacle. Ainsi a-t-on peu commenté le chiffre donné par Bruxelles, la semaine dernière, à propos du nombre de migrants appelés, d’ici 2017, à aborder aux rives heureuses de l’Europe : 3 millions – le double, probablement, comme tout chiffre donné par les « instances officielles », et sans préciser s’il tient compte de ceux qu’on commence à appeler les « réfugiés climatiques », auquel cas le chiffre devrait être multiplié par trois ou quatre, ce qui, une fois encore, me fait songer que les espaces déserts du Massif central ne resteraient plus dépeuplés.

L’actualité, c’est-à-dire le Spectacle, abonde en déclarations et évènements dont l’accumulation suscite une zone d’incertitude entre le mensonge, l’oubli et l’indifférence, sur laquelle se fonde la politique, autre nom du Spectacle. Ainsi a-t-on peu commenté le chiffre donné par Bruxelles, la semaine dernière, à propos du nombre de migrants appelés, d’ici 2017, à aborder aux rives heureuses de l’Europe : 3 millions – le double, probablement, comme tout chiffre donné par les « instances officielles », et sans préciser s’il tient compte de ceux qu’on commence à appeler les « réfugiés climatiques », auquel cas le chiffre devrait être multiplié par trois ou quatre, ce qui, une fois encore, me fait songer que les espaces déserts du Massif central ne resteraient plus dépeuplés. Les conséquences de ce peuplement forcé sont incalculables, l’immigration extra-européenne contribuant déjà, depuis quarante ans, à la destruction des nations qui ont donné le meilleur de la civilisation ; des nations qui ne sauraient être considérées du point de vue ethnique comme les Etats-Unis d’Amérique, quel que soit leur degré d’avilissement et de tiers-mondisation (comme on peut le constater avec le patron de Google venu faire l’aumône de 83 millions d’euros à des start-up françaises, générosité intéressée qu’on croyait réservée à l’Afrique). La question du nombre est ici démoniaque, car une force illégitime que le « sens de l’histoire » tente de faire passer pour irrésistible. J’élève là-contre une voix solitaire, refusant de voir la culture (et non « ma » culture) sacrifiée à ce nombre qui arrive avec ses lois, son code civil, son refus de s’assimiler. Je refuserais de voir, comme au Canada, pays insignifiant à tout point de vue, et non pas une nation mais un conglomérat multiculturel, un ministre de la défense sikh arborant barbe et turban. Pourquoi pas une ministre des affaires sociales en burqa ou un secrétaire d’Etat mélanésien avec un os dans le nez ! Rien de plus contraire à l’essence d’un pays comme la France et des nations européennes. Ce serait aussi illégitime que de voir James Bond (le personnage créé par Ian Fleming étant, comment le nier, un Blanc) incarné par un acteur noir, comme le bruit court à ce sujet. Non que j’attache de l’importance à James Bond ; mais il ne viendrait à l’idée de personne de faire incarner Porgy et Bess par des chanteurs blancs. James Bond est un des marqueurs du Spectacle comme il y en a du cancer. Le cancer du multiculturalisme est particulièrement à la hausse, tout comme celui de la confusion qui fait prendre Hollande pour exégète de Clausewitz, Jérôme Garcin pour un écrivain et André Glucksmann, qui vient de mourir et dont il ne restera rien, pour un penseur : le seule penseur considérable de notre temps, avec Emmanuel Levinas et Gilles Deleuze, c’est René Girard, mort la semaine dernière, et dont l’œuvre continue à agir…

Les conséquences de ce peuplement forcé sont incalculables, l’immigration extra-européenne contribuant déjà, depuis quarante ans, à la destruction des nations qui ont donné le meilleur de la civilisation ; des nations qui ne sauraient être considérées du point de vue ethnique comme les Etats-Unis d’Amérique, quel que soit leur degré d’avilissement et de tiers-mondisation (comme on peut le constater avec le patron de Google venu faire l’aumône de 83 millions d’euros à des start-up françaises, générosité intéressée qu’on croyait réservée à l’Afrique). La question du nombre est ici démoniaque, car une force illégitime que le « sens de l’histoire » tente de faire passer pour irrésistible. J’élève là-contre une voix solitaire, refusant de voir la culture (et non « ma » culture) sacrifiée à ce nombre qui arrive avec ses lois, son code civil, son refus de s’assimiler. Je refuserais de voir, comme au Canada, pays insignifiant à tout point de vue, et non pas une nation mais un conglomérat multiculturel, un ministre de la défense sikh arborant barbe et turban. Pourquoi pas une ministre des affaires sociales en burqa ou un secrétaire d’Etat mélanésien avec un os dans le nez ! Rien de plus contraire à l’essence d’un pays comme la France et des nations européennes. Ce serait aussi illégitime que de voir James Bond (le personnage créé par Ian Fleming étant, comment le nier, un Blanc) incarné par un acteur noir, comme le bruit court à ce sujet. Non que j’attache de l’importance à James Bond ; mais il ne viendrait à l’idée de personne de faire incarner Porgy et Bess par des chanteurs blancs. James Bond est un des marqueurs du Spectacle comme il y en a du cancer. Le cancer du multiculturalisme est particulièrement à la hausse, tout comme celui de la confusion qui fait prendre Hollande pour exégète de Clausewitz, Jérôme Garcin pour un écrivain et André Glucksmann, qui vient de mourir et dont il ne restera rien, pour un penseur : le seule penseur considérable de notre temps, avec Emmanuel Levinas et Gilles Deleuze, c’est René Girard, mort la semaine dernière, et dont l’œuvre continue à agir…

D’Annunzio was a man of great individual courage — it has to be said — and combined the ferocity of the warrior and the sensibility of the artist. One of his most famous individual coups was this 700-mile round trip in an airplane to drop pamphlets of a sort of pro-Western/pro-Italian type on Vienna, which is still remembered to this day. Another of his feats was attacking various German boats with small little motor-powered launchers, something that prefigures a lot of modern warfare where great, large hulking liners and aircraft carriers can be disabled by small boats that speed around them. The principle of guerrilla type or asymmetric warfare whereby much larger entities can be hamstrung by their smaller, Lilliputian equivalents or rivals. Again, this sort of special forces warfare in a way, whether in the air or on the sea, was part and parcel of D’Annunzio’s aesthetic and ethic of life.

D’Annunzio was a man of great individual courage — it has to be said — and combined the ferocity of the warrior and the sensibility of the artist. One of his most famous individual coups was this 700-mile round trip in an airplane to drop pamphlets of a sort of pro-Western/pro-Italian type on Vienna, which is still remembered to this day. Another of his feats was attacking various German boats with small little motor-powered launchers, something that prefigures a lot of modern warfare where great, large hulking liners and aircraft carriers can be disabled by small boats that speed around them. The principle of guerrilla type or asymmetric warfare whereby much larger entities can be hamstrung by their smaller, Lilliputian equivalents or rivals. Again, this sort of special forces warfare in a way, whether in the air or on the sea, was part and parcel of D’Annunzio’s aesthetic and ethic of life.

Les Editions Via Romana viennent de publier

Les Editions Via Romana viennent de publier  L'intérêt du livre de Jacques Perret est là, nous narrer l'avant-guerre, « la paix des familles, l'état d'innocence, l'harmonie universelle » ou « la cueillette des prunes », les devoirs de classe, les jeux en plein air, au Jardin du Luxembourg des distractions enfantines, les cabanes et les courses à vélo, agrémentées de pénibles leçons de piano. Dès lors, en lisant le livre, on ne peut pas commémorer la grande guerre sans faire des parallèles avec le repli familial des années 90 qui anticipe ce que sera le choc historique des années 2015-2025. Certes en 1912 pas de grand remplacement ni de théorie du genre obligatoire, de totalitarisme de l'édredon, rien de tout cela dans le portrait d'une famille plutôt traditionnelle d'avant-guerre avec le camembert et le pinard à la sortie de la Messe, ou les enfants montés de force à l'étage quand les grands finissaient d'arroser la soirée au calvados dans le salon : « De fumants éclats montaient jusqu'aux chambres des enfants et nous comprenions alors vaguement dans le demi-sommeil, quelle institution difficile et miraculeuse était la famille où sans être d'accord sur tout on peut s'embrasser à propos de rien ». En réalité, aujourd'hui, les enfants ne dorment plus très tôt, ne montent dans leurs chambres que pour les jeux vidéos tandis que leurs parents pianotent sur leurs portables sans même se parler ou se poser des questions. Mais n'est-ce pas aussi un climat d'avant-guerre, le climat insouciant d'une guerre mondiale qui sera hybride et civile mais dont on veut dénie la probable réalité barbaresque ou nucléaire ? En fait, ce paradis familial que narre Jacques Perret avant la grande catastrophe de 14 existe encore même s'il n'y a plus d'éden républicain capable de fomenter la fierté grandiloquente de l'humble devoir patriotique. Il n'y a plus de nation mais des rapatriements d'exilés ou d'immigrés dans des drapeaux brûlés, déchirés ou remplacés sur les places publiques par les bannières ennemies de républiques islamiques.

L'intérêt du livre de Jacques Perret est là, nous narrer l'avant-guerre, « la paix des familles, l'état d'innocence, l'harmonie universelle » ou « la cueillette des prunes », les devoirs de classe, les jeux en plein air, au Jardin du Luxembourg des distractions enfantines, les cabanes et les courses à vélo, agrémentées de pénibles leçons de piano. Dès lors, en lisant le livre, on ne peut pas commémorer la grande guerre sans faire des parallèles avec le repli familial des années 90 qui anticipe ce que sera le choc historique des années 2015-2025. Certes en 1912 pas de grand remplacement ni de théorie du genre obligatoire, de totalitarisme de l'édredon, rien de tout cela dans le portrait d'une famille plutôt traditionnelle d'avant-guerre avec le camembert et le pinard à la sortie de la Messe, ou les enfants montés de force à l'étage quand les grands finissaient d'arroser la soirée au calvados dans le salon : « De fumants éclats montaient jusqu'aux chambres des enfants et nous comprenions alors vaguement dans le demi-sommeil, quelle institution difficile et miraculeuse était la famille où sans être d'accord sur tout on peut s'embrasser à propos de rien ». En réalité, aujourd'hui, les enfants ne dorment plus très tôt, ne montent dans leurs chambres que pour les jeux vidéos tandis que leurs parents pianotent sur leurs portables sans même se parler ou se poser des questions. Mais n'est-ce pas aussi un climat d'avant-guerre, le climat insouciant d'une guerre mondiale qui sera hybride et civile mais dont on veut dénie la probable réalité barbaresque ou nucléaire ? En fait, ce paradis familial que narre Jacques Perret avant la grande catastrophe de 14 existe encore même s'il n'y a plus d'éden républicain capable de fomenter la fierté grandiloquente de l'humble devoir patriotique. Il n'y a plus de nation mais des rapatriements d'exilés ou d'immigrés dans des drapeaux brûlés, déchirés ou remplacés sur les places publiques par les bannières ennemies de républiques islamiques.

GF-T : Maurice Bardèche ne fait pas œuvre d’historien. Il puise dans l’histoire des exemples marquants. Quand il rédige L’œuf de Christophe Colomb, il a en tête deux visions d’Europe inachevées ou avortées : l’Europe de la Grande Nation de Napoléon Ier et celle des volontaires européens sur le front de l’Est de 1941 à 1945, la première étant plus prégnante dans son esprit que la seconde.

GF-T : Maurice Bardèche ne fait pas œuvre d’historien. Il puise dans l’histoire des exemples marquants. Quand il rédige L’œuf de Christophe Colomb, il a en tête deux visions d’Europe inachevées ou avortées : l’Europe de la Grande Nation de Napoléon Ier et celle des volontaires européens sur le front de l’Est de 1941 à 1945, la première étant plus prégnante dans son esprit que la seconde.

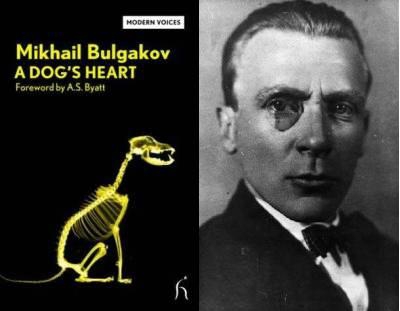

The atmosphere established is eerie. Bulgakov has already here located the absurd fact that Soviet society actually embodied what it denied. It may have consciously rejected the existence of the demonic, but the existence of such a society was itself proof of it.

The atmosphere established is eerie. Bulgakov has already here located the absurd fact that Soviet society actually embodied what it denied. It may have consciously rejected the existence of the demonic, but the existence of such a society was itself proof of it. As an experiment Sharik’s scrotum and hypophysis are removed and replaced by human equivalents. He survives the operation and a most unusual result unfolds—he slowly becomes human.

As an experiment Sharik’s scrotum and hypophysis are removed and replaced by human equivalents. He survives the operation and a most unusual result unfolds—he slowly becomes human. His death when the future writer was only 15 years old shook the boy’s faith in that God is Benevolent and All-knowing. But for Bulgakov conscious disbelief in the God of the Orthodox Church did not entail an a priori atheism, least of all of the simplistic and materialist kind sponsored by the Soviet State.

His death when the future writer was only 15 years old shook the boy’s faith in that God is Benevolent and All-knowing. But for Bulgakov conscious disbelief in the God of the Orthodox Church did not entail an a priori atheism, least of all of the simplistic and materialist kind sponsored by the Soviet State.

Berlioz didn’t believe in life after death. Berlioz believed man is essentially a very complex material object. His final retribution is to be made into one, though a very simple one, a goblet, out of which a toast is made to the immortality he denied so vehemently.

Berlioz didn’t believe in life after death. Berlioz believed man is essentially a very complex material object. His final retribution is to be made into one, though a very simple one, a goblet, out of which a toast is made to the immortality he denied so vehemently.

PHILITT :

PHILITT :  PHILITT :

PHILITT :

Chrétien, venu à la cour de l’empereur Barberousse vers 1180, y avait rencontré l’ambassadeur byzantin. Les chansons de geste byzantines étaient proches des nôtres, et Chrétien explique les liens entre cette littérature et nos prédécesseurs.

Chrétien, venu à la cour de l’empereur Barberousse vers 1180, y avait rencontré l’ambassadeur byzantin. Les chansons de geste byzantines étaient proches des nôtres, et Chrétien explique les liens entre cette littérature et nos prédécesseurs.

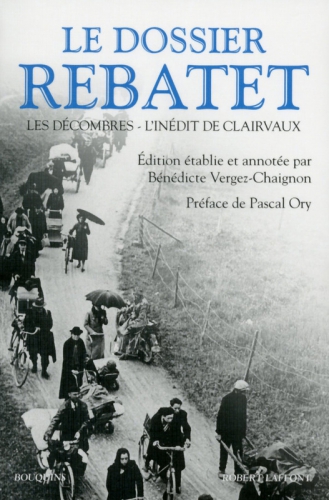

Sorti en 1942, Les Décombres de Lucien Rebatet (deuxième titre majeur après Les deux étendards) viennent d’être réédités chez Robert Laffont. Cinq mille exemplaires épuisés dès le premier jour, l’éditeur a lancé un deuxième tirage à trois mille.

Sorti en 1942, Les Décombres de Lucien Rebatet (deuxième titre majeur après Les deux étendards) viennent d’être réédités chez Robert Laffont. Cinq mille exemplaires épuisés dès le premier jour, l’éditeur a lancé un deuxième tirage à trois mille.

Les attentats de janvier 2015 ne sont pas survenus au gré de circonstances équivoques, par la simple volonté d’illuminés vengeurs qui ne supportaient pas des caricatures vieilles de 10 ans, d’un journal satirique en cours d’effondrement économique pour cause de manque de lecteurs. Cette histoire de liberté d’expression bafouée ne fut qu’un paravent pour éviter de parler de politiques françaises lourdes de conséquences.

Les attentats de janvier 2015 ne sont pas survenus au gré de circonstances équivoques, par la simple volonté d’illuminés vengeurs qui ne supportaient pas des caricatures vieilles de 10 ans, d’un journal satirique en cours d’effondrement économique pour cause de manque de lecteurs. Cette histoire de liberté d’expression bafouée ne fut qu’un paravent pour éviter de parler de politiques françaises lourdes de conséquences. Cette information revisitée, ré-évaluée en permanence — quasi amnésique — est logique puisque le but n’est pas d’informer sur le réchauffement climatique, mais de démontrer — à tout prix — la réalité d’un réchauffement anthropique. Ceux qui se penchent sur les ré-écritures de cette histoire, sur les prévisions ratées, sur les jeux de données choisis de façon univoque [avec l’écartement des études ou jeux de données ne collant pas bien avec la démonstration anthropique], ou simplement qui pointent des incohérences ou émettent des doutes sur la connaissance parfaite du climat par la science actuelle — sont donc taxés de climato-sceptiques.

Cette information revisitée, ré-évaluée en permanence — quasi amnésique — est logique puisque le but n’est pas d’informer sur le réchauffement climatique, mais de démontrer — à tout prix — la réalité d’un réchauffement anthropique. Ceux qui se penchent sur les ré-écritures de cette histoire, sur les prévisions ratées, sur les jeux de données choisis de façon univoque [avec l’écartement des études ou jeux de données ne collant pas bien avec la démonstration anthropique], ou simplement qui pointent des incohérences ou émettent des doutes sur la connaissance parfaite du climat par la science actuelle — sont donc taxés de climato-sceptiques.

Cuando estos días prepárabamos el excursus a la "Elucidación de la tradición", dedicado en dos entregas (

Cuando estos días prepárabamos el excursus a la "Elucidación de la tradición", dedicado en dos entregas (

Michel Houellebecq is one of the finest novelists living today. His most recent novel, Submission, is now out in English. It confirms my long-held suspicion that Houellebecq is a man of the Right, whether or not he admits it to us, or even to himself.

Michel Houellebecq is one of the finest novelists living today. His most recent novel, Submission, is now out in English. It confirms my long-held suspicion that Houellebecq is a man of the Right, whether or not he admits it to us, or even to himself. In the social realm, the patriarchal family is reestablished as the norm. Women are encouraged to choose families over careers. Sexual modesty in dress, behavior, advertising, and popular culture is rapidly adopted. Oh, and Muslim men are allowed up to four wives.

In the social realm, the patriarchal family is reestablished as the norm. Women are encouraged to choose families over careers. Sexual modesty in dress, behavior, advertising, and popular culture is rapidly adopted. Oh, and Muslim men are allowed up to four wives.

On a tant écrit sur Drieu. On a un peu l’impression qu’aujourd’hui, le mieux, pour l’évoquer, est encore de le relire. Il y a eu Drieu le petit-bourgeois déclassé, disséqué par François Nourissier — un expert —; il y a eu le souvenir de l’ami, par Berl dans Présence des morts (magnifique évocation d’un adolescent éternel — et c’est compliqué, signifie Berl, lorsqu’on a 50 ans… —) ; il y a eu l’ami encore, par Malraux dans ses entretiens avec Frédéric Grover, ou par Audiberti, dans Dimanche m’attend, un des rares présents aux obsèques de Drieu, en dépit du contexte et en vertu d’une fidélité amicale certaine ; il y a eu Michel Mohrt et l’évocation de Fitzgerald à propos de Drieu, son “cousin américain” (voir leurs rapports avec les femmes, l’argent et la mélancolie).

On a tant écrit sur Drieu. On a un peu l’impression qu’aujourd’hui, le mieux, pour l’évoquer, est encore de le relire. Il y a eu Drieu le petit-bourgeois déclassé, disséqué par François Nourissier — un expert —; il y a eu le souvenir de l’ami, par Berl dans Présence des morts (magnifique évocation d’un adolescent éternel — et c’est compliqué, signifie Berl, lorsqu’on a 50 ans… —) ; il y a eu l’ami encore, par Malraux dans ses entretiens avec Frédéric Grover, ou par Audiberti, dans Dimanche m’attend, un des rares présents aux obsèques de Drieu, en dépit du contexte et en vertu d’une fidélité amicale certaine ; il y a eu Michel Mohrt et l’évocation de Fitzgerald à propos de Drieu, son “cousin américain” (voir leurs rapports avec les femmes, l’argent et la mélancolie).

Le Jeudi:

Le Jeudi: