Kerry Bolton

Perón and Perónism

London: Black House Publishing, 2014

Perón and Perónism is an excellent resource on the political thought of Argentina’s three-time president Juan Domingo Perón. It places him firmly among the elite ranks of Third Position thinkers. His doctrine of Justicalism and his geopolitical agenda of resistance to both American and Soviet domination of Latin America have demonstrated enduring relevance. Influenced by Aristotle’s conception of man as a social being and the social teachings of the Catholic Church, Perón proved to be an insightful political philosopher, developing a unique interpretation of National Syndicalism that guided his Justicalist Party. While his career was marked by turmoil, he pursued an agenda of the social justice, seeking the empowerment of the nation’s working classes as a necessary step towards the spiritual transformation of the country. Perón’s example stands as a beacon to those who seek the liberation of man from the bondage of materialism, and the liberation of the nation from foreign domination.

Perón and Perónism is an excellent resource on the political thought of Argentina’s three-time president Juan Domingo Perón. It places him firmly among the elite ranks of Third Position thinkers. His doctrine of Justicalism and his geopolitical agenda of resistance to both American and Soviet domination of Latin America have demonstrated enduring relevance. Influenced by Aristotle’s conception of man as a social being and the social teachings of the Catholic Church, Perón proved to be an insightful political philosopher, developing a unique interpretation of National Syndicalism that guided his Justicalist Party. While his career was marked by turmoil, he pursued an agenda of the social justice, seeking the empowerment of the nation’s working classes as a necessary step towards the spiritual transformation of the country. Perón’s example stands as a beacon to those who seek the liberation of man from the bondage of materialism, and the liberation of the nation from foreign domination.

Juan Domingo Perón was born on the 8th of October 1895 and graduated from the Colegio Militar, entering the military as a sublieutenant. He later attended the Escuela Superior de Guerra, and became a professor of military history at the War College. His mission to Europe in 1939 proved to be a formative experience on his political consciousness. He was inspired by Mussolini’s rejection of both American capitalism and Soviet communism, stating that, “When faced with a world divided by two imperialisms, the Italians responded: we are on neither side. We represent a third position between Soviet socialism and Yankee imperialism.” Perón became a member of the Group of United Officers (GOU) that overthrew in the Argentine government in 1943.

The GOU was menaced by American pressure due to Argentina’s neutrality in the Second World War and its pro-Axis government. An attempt to buy arms from Germany resulted in American ships being sent to patrol near the mouth of the River Plate and the refusal of American banks to transfer Argentine funds. In response Argentina severed relations with the Axis, but that did not prevent an American embargo.

Within the GOU government, Perón eventually became Vice President, Minister of War, Secretary of Labor and Social Reform, and head of the Post-War Council. He became known as a champion of labor, supporting unionization, social security, and paid vacations, meeting populist radio actress Eva Duarte, his second wife, in the process. However, Perón’s success attracted suspicion from others in the government and General Eduardo Avales forced him to resign his posts and had him imprisoned on October 10th 1945.

However, the forced resignation and imprisonment of Perón triggered a fateful sequence of events that were eventually commemorated in Justicalist ideology on “Loyalty Day.” In response to Perón’s imprisonment, Eva Duarte rallied his supporters in labor, and the CGT labor union declared a general strike. Workers mobbed the labor department in support of the profit-sharing law Perón sponsored. They ran the police gauntlet to flood the plaza in front of the presidential palace. Perón was released and declared his candidacy for the presidency before throngs of supporters from the blacony of the presidential palace on October 17th, now celebrated as “Loyalty Day” by Perónists.

The 1946 election was essentially a struggle between Perón and the US-backed oligarchy of Argentina. Perónist posters asked “Braden or Perón?,” referencing the American ambassador Spruille Braden. The United States attempted to demonize Perón, accusing him of collaboration with the Axis in the Second World War and claiming that Perón planned to institute a totalitarian state, with tactics reminiscent of latter days attempts to paint any leader who doesn’t toe the American line as a rogue who hates freedom. The document summarizing America’s vendetta against Perón was adopted by the anti-Perón Unión Democrática, which comprised both oligarchs and some communist elements. The willingness of the opposition to act as lapdogs for Yankee imperialism only strengthened Perón’s support and he won the election of February 24th 1946.

Perón’s base of support came from the working classes, nicknamed descamisados, the shirtless. The doctrine that drew their support, Justicialism, is a type of National Syndicalism, devoted to the achievement of social justice within the context of the nation as an organic social unit. Perónist constitutional thinker Arturo Sampay defined social justice as “that which orders the interrelationships of social groups, professional groups, and classes with individual obligations, moving everyone to give to other in participation in the general welfare.”

The achievement of social justice would necessitate the elimination of artificial distinctions in society, such as economic classes and political parties. Instead every sector of society would be organized into its own syndicate, essentially the equivalent of the medieval guilds that were destroyed in the French Revolution. Perón saw in the guilds of the past an alternative to the capitalist system of wage labor, providing a social dimension to labor. The worker was a craftsman, integrated into the wider world, instead of a mere cog for the capitalists. Perón saw capitalism as the exploitation of producers by the owners of the means of production:

Capitalism refines and generalizes the system of wages throughout the production area, or the exploitation of the poor by the wealthy. This gives birth to new economic and social classes. For one the holders of the means of production – machinery, art, tools, workshops, that is – the capitalist bourgeoisie; on the other hand, employees or the proletariat to deliver the first fruits of their creative efforts.

Man thus becomes a number, without the union corporation, without professional privileges, without the protection and representation of his Estate. The political party establishes the non-functional structure that serves the bourgeoisie in power.

Justicialism sought to undo this distortion of the natural order caused by capitalism. To achieve this, Perón gave a special position to labor unions as leading actors, seeing them as the basis for the syndicates he envisioned to represent each function in society. He sought to transform enterprises into cooperatives where profits where shared between all the producers. Their governing bodies would be the syndicates, who served the national interest, rather than capitalists who served profit alone. Private property would still exist under Justicalism, but it would be distributed so as to encourage production, the ownership of property yoked to the greater good of the nation. He stated that every Argentine should have his own property, yet he believed that factories and businesses should belong to those who work in them. Industries crucial to the maintenance of national sovereignty and economic independence like banking and mining would belong to the state, in order to prevent foreign capitalists from seizing the vitals of the Argentine nation. Perón’s government nationalized the banks, the railways, the airlines, the port of Buenos Aires, and he established the state run oil and gas industry. Much like the Catholic social doctrine of Distributism, Justicialism did not seek to eliminate private property but to give each man what was necessary to produce for the greater good of society.

For Perón work would become an ideal higher than mere bread-winning. It is a spiritual calling that links the achievements of an individual to the achievements of the past and his people. It is a tool of individual and social growth. Work should be mandatory, with everyone striving to contribute, however at the same time the dignity of the worker must be enshrined by law. As such the government enacted a “Workers’ Bill of Rights.” It affirmed the right to a fair wage, unionization, education, safe working conditions, healthcare, adequate healthcare and housing, and social security. However, unlike modern social democrats who see the welfare state as simply providing for man’s materialistic needs, Perón saw it as step towards the spiritual development of the people.

Citing Aristotle’s belief that man was a social being who actualized himself through participation in society, he saw eliminating material hardships as the first step in developing the virtue of the people. Through communal organization the ideal of a better humanity could be reached. In a further tribute the classical ideals of communal self-improvement, Perón emphasized the importance of physical exercise, stating that:

the educated man must have developed to being harmonious and balanced in both his intelligence and his soul and his body. . . . We want intelligence to be in the service of a good soul and a strong man. In this we are not inventing anything, we are going back to the Greeks who were able to establish that perfect balance in their men in the most glorious period of its history.

Through sports the youth would develop civic virtue, training men for a life of service. One of the administrations involved in implementing this task was the Fundación Eva Perón.

The Fundación Eva Perón was a social aid agency named for Juan Domingo’s wife, Eva, who played a leading role in it. Established in 1948, its goals included giving scholarships and training to the poor, constructing housing, schools, hospitals, and other public buildings, and engaging in work for the common good. Eva Perón termed this Social Aid, a form of collective self help, explicitly rejecting the idea of charity, saying:

The donations, which I receive every day, sent into the Fund by workmen, prove that the poor are those who are ready to do the most to help the poor. That is why I have always been opposed to charity. Charity satisfies the person who dispenses it. Social Aid satisfies the people themselves, inasmuch as they make it effective. Charity is degrading while Social Aid ennobles. Give us Social Aid, because it implies something fair and just. Out with charity!

Among the successful Social Aid projects of the Fundación Eva Perón were the training of nurses, the establishment of large hospitals termed policlincs, the establishment of mobile health care trains, and the construction of homes for the elderly, students, and children.

Given the active and outspoken role Eva Perón played in the Justicalist movement, one would think she would be embraced as a feminist icon. However, Evita herself disdained such characterizations and affirmed the necessity of differing roles for the sexes. She said:

Every day thousands of women forsake the feminine camp and begin to live like men. They work like them. They prefer, like them, the street to the home. They substitute for men everywhere. Is this “feminism”? I think, rather, that is must be the “masculinization” of our sex.

And I wonder if all this change has solved our problem? But no, all the old ills continue rampant, and new ones too, appear. The number of women who look down upon the occupation of homemaking increases every day. And yet that is what we are born for. We feel we are born for the home, and home is too great a burden for our shoulders. Then we give up the home . . . go out to find a solution . . . feel that the answer lies in obtaining economic independence and working somewhere. But does that makes us equal to men? No! We are not like them! We feel the need of giving rather than receiving. Can’t we work for anything else than earning wages like men?

The Justicialist creed of social justice supported the family as the basis of society. Juan Perón stated, “Man is created in the image and likeness of God. But this transcendent unity is by nature a social being: born of a family, man and woman, as the first basic social group and the parents provide essential care, without which man cannot survive. This develops within a broader community that was forming along centuries and, therefore, provides the imprint of a civilization and a historical culture. It develops into productive, cultural, professional and other intermediate communities.” In providing social welfare Perón was not replacing the family with the state, but ensuring that a man could afford to feed his family, to maintain their well-being so as to encourage their social development within the nation. By tending this seed of the nation, Justicialism would ensure the growth of virtue among the citizens.

A further part of Perón’s social agenda was the destruction of usury. Perón held that the creation of money should serve a social purpose, not profit the bankers. His government nationalized the banks. Perónist Arturo Sampay said, “Whoever gives the orders on credit and the expansion or contraction of the money supply, controls the development of the country.” As a basic principle of national sovereignty the nation cannot be indebted to private bankers or foreign investors. If a bank is foreign owned or invested in foreign trade, it serves the interests of the foreigners, not the country. Perón termed the banks sepoys, referring to Indian troops who served British imperialism. Perón’s government used the National Mortgage Bank to provide money for public housing at low interest rates, which allow many people to own homes, leading to a more the equitable distribution of property. Perón believed that the money supply should not be manipulated by bankers for profit, but increased or decreased at a rate tied to the work done by the members of the nation. Money was not tied to vague financial mechanisms, but real labor and production. Perón wrote:

But in the domestic, social economy our doctrine states that the currency is a public service that increases or decreases, is valued or devalued in direct proportion to the wealth produced by the work of the Nation.

Money is for us one effective support of real wealth that is created by labor. That is, the value of gold is based on our work as Argentines. It is not valued at weight, as in other currencies based on gold, but by the amount of welfare that can be funded by working men. Neither the dollar or gold are absolute values, and happily we broke in time with all the dogmas of capitalism and we have no reason to repent. It happens, however, as to those who accept willingly or unwillingly the orders or suggestions of capitalism, that the fate of their currencies is tied to what is minted or printed in the Metropolis, encrypting all the wealth of a country circulating with strong currencies, but without producing anything other than currency trade or speculation. We despise, perhaps a bit, the value of hard currencies and choose to create instead the currency of work. Maybe this is a little harder than what you earn speculating, but there are fewer variables in the global money game.

Gentleman, in terms of “social economy,” it is necessary to establish definitely: The only currency that applies to us is the real work and production that are born on the job.

Perón’s rejection of international monetary conventions attracted the enmity of the foreign powers intent on using Argentina’s wealth for their own gain. Argentina explicitly rejected the International Monetary Fund. In foreign trade, instead of pursuing exchanges through currency Argentina sought to swap foreign commodities for their commodities, directly bartering goods instead of money. Perón’s refusal to abide by the demands the United States’ global plutocracy drew America’s ire. In 1948 the US excluded Argentine exports from the Marshall Plan zone. Attempts to resolve their differences where stymied by Congress’ refusal to accept the role of the Argentina Institute for the Promotion of Trade (IAPI), which sold Argentine commodities on the international market and subsidized their national production. This autarchic economic planning mechanism flew in the face of America’s pursuit of globalization. If Argentina refused to give dollars, instead seeking to barter goods, the US demanded that they give concessions to American companies, allowing foreign industry to compete with national ones Perón was devoted to developing. America’s assault on Argentina’s economy was a grievous blow to the Perón government, and he began his second term in 1952 with a $500 million trade deficit. That year saw meat shortages and power failures, and while the economy recovered somewhat from 1953 to 1955, the stage was set for the downfall of the regime. In 1955, after a failed coup attempt on September 3rd, a successful coup attempt was launched by the Navy on the 16th. Perón left for Paraguay on the 20th and eventually settled in Spain. The fall of Perón’s government led to the sale of national assets to US corporations, by 1962 production had dropped, the trade deficit had massively increased, and the price of of food increased by 750%.

While his attempts to resist Yankee domination failed and led to the end of his second term, Perón attempted to develop a geopolitical doctrine that would prevent Latin America from falling prey to the predations of the US. He proposed a formation of a geopolitical bloc to resist the Superpowers intent on controlling Latin America, effectively making him an advocate of the multi-polar world envisioned by Russian geopolitical theorist Alexander Dugin fifty years later. In 1951 he articulated his goal:

The sign of the Southern Cross can be the symbol of triumph of the numina of the America of the Southern Hemisphere. Neither Argentina, nor Brazil, nor Chile can, by themselves, dream of the economic unity indispensable to face a destiny of greatness. United, however, they form a most formidable unit, astride the two oceans of modern civilization. Thus Latin-American unity could be attempted from here, with a multifaceted operative base and unstoppable initial drive.

On this basis, the South American Confederation can be built northward, joining in that union all the peoples of Latin roots. How? It can come easily, if we are really set to do it.

We know that these ideas will not please the imperialists who divide and conquer. United we will be unconquerable; separate defenseless. If we are not equal to our mission, men and nations will suffer the fate of the mediocre. Fortune will offer us her hand. May God wish we know to take hold of it. Every man and every nation has its hour of destiny. This is the hour of the Latin people.

Perón made overtures to the governments of Brazil and Chile to pursue regional cooperation. In 1953, Chile’s president Carlos Ibáñez del Campo, a friend of Perón, signed an agreement with Argentina to reduce tariffs, facilitate bilateral trade, and establish a joint council on relations between the two nations. Similarly, he pursued integration with Brazil, led by the corporatist Getulio Vargas. While Vargas had been supported in the presidential election by Argentina, he was constrained by pro-American forces in Brazil’s government and a general reliance on American trade. Any chance of integration faded with the suicide of Vargas in the face of an impending revolt.

Perón’s geopolitical relations also extended to Europeans who sought to break free from the American domination that had descended upon the continent in the wake of the Second World War. Like Latin America, Europe had been subjected to Yankee imperialism. Perón met several times with Oswald Mosley, the former leader of the British Union of Fascists, who advocated the formation of an integrated European bloc to reject American and Soviet domination after the World War II, analogous to the Latin American continental unity that Perón supported. Mosley visited Argentina in 1950 and his views may have shaped the development Perón’s geopolitical vision. From exile Perón wrote to Mosley, “I see now we have friends in common whom I greatly value, something which makes me reciprocate even more your expressions of solidarity . . . I offer my best wishes and a warm embrace.”

Among the mutual friends of Mosley and Perón was Jean Thiriart, whom he met through German commando Otto Skorzeny. Like Mosley, Thiriart advocated the formation of a unified Europe to combat American imperialism, though on a more militant level. He saw Latin America, which had been engaged in struggles against American domination for far longer than Europe as an ally to his cause. Perón responded positively to Thiriart’s ideas writing, “A united Europe would count a population of nearly 500 million, The South American continent already has more than 250 million. Such blocs would be respected and effectively oppose the enslavement to imperialism which is the lot of a weak and divided country.” Thus a fundamental alliance between Third World Third Positionism and European Third Positionism existed.

From exile in 1972, Perón addressed the situation of the Third World, decrying the social and ecological destruction wrought by international capitalism. He made several recommendations in that speech regarding the necessary steps they must take to ensure social justice in their nations:

- We protect our natural resources tooth and nail from the voracity of the international monopolies that seek to feed a nonsensical type of industrialization and development in high tech sectors with market-driven economies. You cannot cause a massive increase in food production in the Third World without parallel development of industries. So each gram of raw material taken away today equates in the Third World countries with kilos of food that will not be produced tomorrow.

- Halting the exodus of our natural resources will be to no avail if we cling to methods of development advocated by those same monopolies, that mean the denial of the rational use of our resources.

- In defense of their interests, countries should aim at regional integration and joint action.

- Do not forget that the basic problem of most Third World countries is the absence of genuine social justice and popular participation in the conduct of public affairs. Without social justice the Third World will not be able to face the agonizingly difficult decades ahead.

Among the Third World countries that Perón took an interest in was Qaddafi’s Libya. When Perón returned to power a delegation was sent to Libya and various agreements on cooperation were signed. These included deals on scientific and economic cooperation between the two countries, cultural exchange, and the establishment of a Libyan-Argentine Bank for investment. Geopoliticallly Qaddafi’s belief in Arab unity aligned with Perón’s views on the creation of blocs to resist imperialism. Like Perón’s Justicialism, Qaddafi pursued an autarkic economic policy he termed “Arab socialism” aimed at the spiritual development of the nation. Qaddafi’s government outlasted Perón and he pursued aligned with Latin American resistors to American imperialism. His government was particularly close to Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela.

Hugo Chávez, the late leader of Venezuela explicitly declared, “I am really a Perónist. I identify with this man and his thought, who asked that our countries are no longer factories of imperialism.” Chávez revived Perón’s dream of a geopolitical bloc to challenge American domination with his Bolivarian Revolution, creating the Bolivarian Alliance for the People of our America (ALBA). As of this writing ALBA contains eleven member countries, Antigua and Barbuda, Bolivia, Cuba, Dominica, Ecuador, Grenada, Nicaragua, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Venezuela. This bloc represents a collection of nations who reject American neo-liberalism and support social welfare and mutual economic aid. Given Chávez’s depiction as a thorn in the side of the American establishment, we can say that Perónist ideals represent a very real challenge to the American New World Order today.

While exile provided Perón with an opportunity to expand his geopolitical contacts and develop his philosophical vision, the election of Héctor Cámpora, a Perónist, who provided the opportunity for Perón to return and run for president, led to a third term as President of Argentina. However, in Perón’s absence, major rifts had developed in the Justicialist movement. The tension between left and right wing factions would eventually develop into open violence. The leftist factions eventually formed a radical guerrilla group, the Montoneros. Perónist guerrilla warfare had an early supporter in John William Cooke, a Perónist who eventually fled to Cuba. His influence eventually opened a way for Marxists to infiltrate the movement. Perón himself was strongly anti-communist, stating that “the victim of both communism and capitalism is the people.” Perón believed that communism and capitalism were part of an “international synarchy” against the people stating “The problem is to free the country and remain free. That is, we must confront the international synarchy of communism, capitalism, Freemasonry, and the Catholic Church, operated from the United Nations. All of these forces act on the world through thousands of agencies.” More right wing factions represented by the CGT claimed that “international synarchy” was attacking their leaders.

On the day of Perón’s return the conflict between left and right turned into open bloodshed at Ezeiza airport. Armed supporters from both tendencies had gathered and a shot rang out. The leftists returned fire, targeting those on the overpass podium. 500 Montoneros stormed the podium but were eventually routed by security forces. Overall 13 people were killed. Perón’s plane was diverted to ensure his safety.

Perón appointed staunch anti-communist José Rega as an intermediary to the left-wing Perónist Youth, signaling his opposition to their cause. Representatives of the Perónist Youth were removed from the Supreme Council of the Justicialist Party, and he instructed CGT leader José Rucci to purge the labor movement of Marxists. Two days after Perón’s election on September 23rd 1973, Rucci, his closest ally and likely political heir, was assassinated by Montoneros. The loss of his likely successor negatively impacted Perón’s already feeble health.

On the 19th of January 1974 the Marxist People’s Revolutionary Army (ERP) attacked the Azul army base. Perón believed they had been aided by Governor Oscar Bidegain, who had bused armed Leftists into Ezeiza. At a May Day rally Perón declared that the young left radicals were dishonoring the founders of the party, upon which the leftists walked out of the rally. Perón attempted to rally the people one last time, making a speech on a freezing day in June. His failing health declined steeply and he died on July 1st.

Following his death, his widow and vice-president Isabel took office. However, the Montoneros declared a full insurrection on the 6th of September. Moreover, economic conditions rapidly spun out of control, leading to a CGT general strike, combined with an escalating rebellion by the left. The Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, led by Rega, waged a bloody counter-revolutionary struggle. National production slowed to a crawl and inflation soared. In 1976, Isabel was overthrown by the army.

The ouster of Isabel Perón did not spell the end of Perónism, however. Currently Justicialist Party member Cristina Kirchner is the president of Argentina, succeeding her late husband, Nestor Kirchner. While she has received some criticism from more traditional Perónists, she has attempted to repudiate the polices of neo-liberalism. In 2012 a bill was introduced to ensure that the Central Bank acted in the interest of social equity. Moreover, Perónist movements outside the Kirchner regime enjoy a great deal of support. Outside of Argentina, the late Hugo Chávez lead the Perón-influenced Bolivarian Revolution, as previously mentioned. It appears, that after years of struggle and heartbreak, Perónism is once again leading Latin America’s resistance to US neo-liberal imperialism.

Kerry Bolton’s book should become essential reading for all of those who wish to see how a mass movement can be built from the ground up to challenge superpowers. It places Perón in his rightful place as one of the great Third Position thinkers, rallying the workers against communism and capitalism for the spiritual growth of the nation. It will not be lengthy digressions on IQ and philosophy that challenge the American liberal empire, but showing the common man the way to a higher life, against the forces of greed and materialism. Perónism represents a true creed of social justice, one of service to society. If there is to be any real progress for the New Right, they must embrace the shirtless ones who toil for their nation as Perón did.

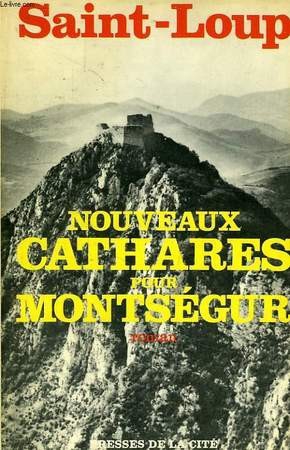

J’ai comme l’impression qu’on ne lit plus beaucoup Saint-Loup (nom de plume de Marc Augier) aujourd’hui, ce que je ne peux que déplorer. Aussi, si ces quelques considérations sur l’un de ses ouvrages phares pouvaient donner à d’aucuns l’envie de se plonger dans l’œuvre de ce grand écrivain, j’en serais ravi.

J’ai comme l’impression qu’on ne lit plus beaucoup Saint-Loup (nom de plume de Marc Augier) aujourd’hui, ce que je ne peux que déplorer. Aussi, si ces quelques considérations sur l’un de ses ouvrages phares pouvaient donner à d’aucuns l’envie de se plonger dans l’œuvre de ce grand écrivain, j’en serais ravi. Au-delà de la question identitaire, Nouveaux cathares pour Monségur est un voyage en Occitanie, dans ses châteaux, ses montagnes, ses légendes. C’est l’occasion aussi pour Saint-Loup de traiter de religion et en particulier du catharisme. Cette foi est ainsi celle de ce mystique personnage qu’est Auda Isarn (dont le nom a été repris par une célèbre maison d’édition). Membre de la bande d’amis de Roger Barbaïra, sa beauté froide la rend désirable à bien des hommes qui s’opposeront pour l’avoir mais une telle femme, dotée d’une telle foi, peut-elle réellement appartenir à un homme et lui dévouer sa vie? Auda Isarn fait partie de ces femmes un peu mystérieuses voire insaisissables que l’on retrouve dans l’œuvre de l’auteur, telle la fameuse Morigane de Plus de pardons pour les Bretons, et est résolument le personnage le plus énigmatique de l’histoire.

Au-delà de la question identitaire, Nouveaux cathares pour Monségur est un voyage en Occitanie, dans ses châteaux, ses montagnes, ses légendes. C’est l’occasion aussi pour Saint-Loup de traiter de religion et en particulier du catharisme. Cette foi est ainsi celle de ce mystique personnage qu’est Auda Isarn (dont le nom a été repris par une célèbre maison d’édition). Membre de la bande d’amis de Roger Barbaïra, sa beauté froide la rend désirable à bien des hommes qui s’opposeront pour l’avoir mais une telle femme, dotée d’une telle foi, peut-elle réellement appartenir à un homme et lui dévouer sa vie? Auda Isarn fait partie de ces femmes un peu mystérieuses voire insaisissables que l’on retrouve dans l’œuvre de l’auteur, telle la fameuse Morigane de Plus de pardons pour les Bretons, et est résolument le personnage le plus énigmatique de l’histoire.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

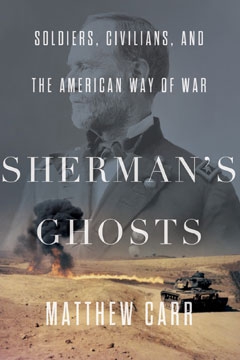

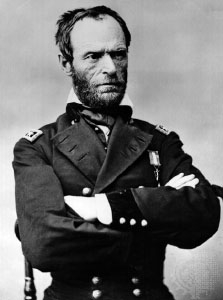

Matthew Carr’s new book,

Matthew Carr’s new book,  Sherman believed that his nastiness would turn the South against war. “Thousands of people may perish,” he said, “but they now realize that war means something else than vain glory and boasting. If Peace ever falls to their lot they will never again invite War.” Some imagine this to be the impact the U.S. military is having on foreign nations today. But have Iraqis grown more peaceful? Does the U.S. South lead the way in peace activism? When Sherman raided homes and his troops employed “enhanced interrogations” — sometimes to the point of death, sometimes stopping short — the victims were people long gone from the earth, but people we may be able to “recognize” as people. Can that perhaps help us achieve the same mental feat with the current residents of Western Asia? The U.S. South remains full of monuments to Confederate soldiers. Is an Iraq that celebrates today’s resisters 150 years from now what anyone wants?

Sherman believed that his nastiness would turn the South against war. “Thousands of people may perish,” he said, “but they now realize that war means something else than vain glory and boasting. If Peace ever falls to their lot they will never again invite War.” Some imagine this to be the impact the U.S. military is having on foreign nations today. But have Iraqis grown more peaceful? Does the U.S. South lead the way in peace activism? When Sherman raided homes and his troops employed “enhanced interrogations” — sometimes to the point of death, sometimes stopping short — the victims were people long gone from the earth, but people we may be able to “recognize” as people. Can that perhaps help us achieve the same mental feat with the current residents of Western Asia? The U.S. South remains full of monuments to Confederate soldiers. Is an Iraq that celebrates today’s resisters 150 years from now what anyone wants?

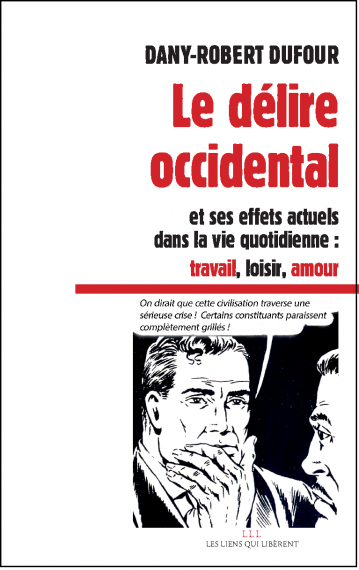

L’adepte de la double-pensée hait le déterminisme tout en prétendant que « tout est social » ; rejette la peine de mort tout en militant pour l’avortement et l’euthanasie; abhorre la famille tout en imposant le mariage homosexuel, la GPA et la PMA pour les couples gays et lesbiens ; prétend que les immigrés sont des chances-pour-la-France (ils vont payer les retraites des Français de souche, faire les travaux dont ceux-ci ne veulent plus, remédier à la fécondité dérisoire des femmes autochtones), tout en dénonçant le fait que les immigrés sont les plus touchés par le chômage, souffrent de l’apartheid, et, en parallèle, constate que les retraites diminuent et le gouffre de la sécu ne cesse de s’agrandir ; refuse le lien entre le multiculturalisme (un enrichissement !) et les tensions communautaires qui agitent la rue ; parle d’un sentiment d’insécurité (sauf quand ce sont des locaux de Libé et de Charlie-Hebdo qui sont attaqués), tout en affirmant que la violence est due à la pauvreté des habitants des quartiers « sensibles »…

L’adepte de la double-pensée hait le déterminisme tout en prétendant que « tout est social » ; rejette la peine de mort tout en militant pour l’avortement et l’euthanasie; abhorre la famille tout en imposant le mariage homosexuel, la GPA et la PMA pour les couples gays et lesbiens ; prétend que les immigrés sont des chances-pour-la-France (ils vont payer les retraites des Français de souche, faire les travaux dont ceux-ci ne veulent plus, remédier à la fécondité dérisoire des femmes autochtones), tout en dénonçant le fait que les immigrés sont les plus touchés par le chômage, souffrent de l’apartheid, et, en parallèle, constate que les retraites diminuent et le gouffre de la sécu ne cesse de s’agrandir ; refuse le lien entre le multiculturalisme (un enrichissement !) et les tensions communautaires qui agitent la rue ; parle d’un sentiment d’insécurité (sauf quand ce sont des locaux de Libé et de Charlie-Hebdo qui sont attaqués), tout en affirmant que la violence est due à la pauvreté des habitants des quartiers « sensibles »…

Het moet zowat de grootste lof zijn die een historicus kan toegezwaaid krijgen, en die lof komt dan zelfs van de veeleisende Nederlandse NRC: 'Het gebeurt niet vaak dat een historicus geschiedenis echt kan herschrijven. Maar Els Witte is het gelukt.'

Het moet zowat de grootste lof zijn die een historicus kan toegezwaaid krijgen, en die lof komt dan zelfs van de veeleisende Nederlandse NRC: 'Het gebeurt niet vaak dat een historicus geschiedenis echt kan herschrijven. Maar Els Witte is het gelukt.'

Pourquoi les Qataris ont-ils été exonérés de toutes taxes immobilières, y compris sur la plus value, alors que les contribuables français, y compris les plus démunis, la payent plein pot ? Pourquoi le club de foot le plus prestigieux, le PSG a-t-il été offert à cet Emirat ? Pourquoi des hôtels particuliers et des châteaux, classés patrimoine mondial, ont-ils été vendus aux oligarques de Doha ? Pourquoi le couple Hamad-Sarkozy ont-ils décidé de détruire la Libye ? Pourquoi la droite au pouvoir a-t-elle autorisé le premier émirat financier du terrorisme islamiste d’investir les banlieues pour prendre en charge les français de la diversité ?A ces questions et à bien d’autres encore, Vanessa Ratignier et Pierre Péan répondent avec l’audace des journalistes libres et l’obstination des écrivains qui ne craignent pas les puissants. Dans la quatrième de couverture, on lit que « Nombre d’États du Golfe lorgnent sur le patrimoine français et tentent, des pétrodollars plein les poches, d’acheter tout ce qui peut l’être avant épuisement de l’or noir. Jusqu’ici nos dirigeants leur avaient résisté – du moins en apparence -, offusqués par tant d’audace. Mais, avec le Qatar, c’est une tout autre histoire. La France est devenue le terrain de jeu sur lequel la famille Al-Thani place et déplace ses pions politiques, diplomatiques, économiques, immobiliers ou industriels ».

Pourquoi les Qataris ont-ils été exonérés de toutes taxes immobilières, y compris sur la plus value, alors que les contribuables français, y compris les plus démunis, la payent plein pot ? Pourquoi le club de foot le plus prestigieux, le PSG a-t-il été offert à cet Emirat ? Pourquoi des hôtels particuliers et des châteaux, classés patrimoine mondial, ont-ils été vendus aux oligarques de Doha ? Pourquoi le couple Hamad-Sarkozy ont-ils décidé de détruire la Libye ? Pourquoi la droite au pouvoir a-t-elle autorisé le premier émirat financier du terrorisme islamiste d’investir les banlieues pour prendre en charge les français de la diversité ?A ces questions et à bien d’autres encore, Vanessa Ratignier et Pierre Péan répondent avec l’audace des journalistes libres et l’obstination des écrivains qui ne craignent pas les puissants. Dans la quatrième de couverture, on lit que « Nombre d’États du Golfe lorgnent sur le patrimoine français et tentent, des pétrodollars plein les poches, d’acheter tout ce qui peut l’être avant épuisement de l’or noir. Jusqu’ici nos dirigeants leur avaient résisté – du moins en apparence -, offusqués par tant d’audace. Mais, avec le Qatar, c’est une tout autre histoire. La France est devenue le terrain de jeu sur lequel la famille Al-Thani place et déplace ses pions politiques, diplomatiques, économiques, immobiliers ou industriels ».

Peter Bickenbach

Peter Bickenbach

THE Glass Bees is an introspective novel about a quiet but dignified cavalry officer called Richard. Unable to adjust to life after war and needing money, he applies for a security job at the headquarters of the mysterious oligarch Zapparoni. Confronted with mechanical and psychological trials, the dream becomes a nightmare, and Richard is forced to contemplate his place in the

THE Glass Bees is an introspective novel about a quiet but dignified cavalry officer called Richard. Unable to adjust to life after war and needing money, he applies for a security job at the headquarters of the mysterious oligarch Zapparoni. Confronted with mechanical and psychological trials, the dream becomes a nightmare, and Richard is forced to contemplate his place in the

9. Islam and Sex

9. Islam and Sex

Perón and Perónism is an excellent resource on the political thought of Argentina’s three-time president Juan Domingo Perón. It places him firmly among the elite ranks of Third Position thinkers. His doctrine of Justicalism and his geopolitical agenda of resistance to both American and Soviet domination of Latin America have demonstrated enduring relevance. Influenced by Aristotle’s conception of man as a social being and the social teachings of the Catholic Church, Perón proved to be an insightful political philosopher, developing a unique interpretation of National Syndicalism that guided his Justicalist Party. While his career was marked by turmoil, he pursued an agenda of the social justice, seeking the empowerment of the nation’s working classes as a necessary step towards the spiritual transformation of the country. Perón’s example stands as a beacon to those who seek the liberation of man from the bondage of materialism, and the liberation of the nation from foreign domination.

Perón and Perónism is an excellent resource on the political thought of Argentina’s three-time president Juan Domingo Perón. It places him firmly among the elite ranks of Third Position thinkers. His doctrine of Justicalism and his geopolitical agenda of resistance to both American and Soviet domination of Latin America have demonstrated enduring relevance. Influenced by Aristotle’s conception of man as a social being and the social teachings of the Catholic Church, Perón proved to be an insightful political philosopher, developing a unique interpretation of National Syndicalism that guided his Justicalist Party. While his career was marked by turmoil, he pursued an agenda of the social justice, seeking the empowerment of the nation’s working classes as a necessary step towards the spiritual transformation of the country. Perón’s example stands as a beacon to those who seek the liberation of man from the bondage of materialism, and the liberation of the nation from foreign domination.

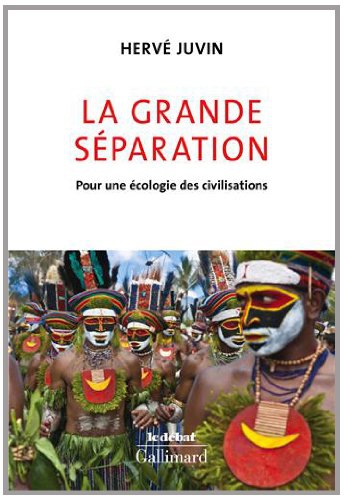

J’ai écrit La Grande Séparation parce que je suis affolé de la perte de notre mémoire historique qui accompagne la perte de notre identité nationale. Le monde dans lequel nous vivons encore est dessiné par des frontières, par des nations, qui nous donnent notre citoyenneté et notre identité. Le principe de la souveraineté nationale garantit aux citoyens la liberté de décider de leurs lois, de leurs mœurs, de leur destin, sur leur territoire et à l’intérieur de leurs frontières. Les conditions d’acquisition de la citoyenneté assurent l’unité de la nation, et la transmission entre les générations. La séparation est géographique, respectueuse des cultures, des civilisations, de la diversité collective des peuples.

J’ai écrit La Grande Séparation parce que je suis affolé de la perte de notre mémoire historique qui accompagne la perte de notre identité nationale. Le monde dans lequel nous vivons encore est dessiné par des frontières, par des nations, qui nous donnent notre citoyenneté et notre identité. Le principe de la souveraineté nationale garantit aux citoyens la liberté de décider de leurs lois, de leurs mœurs, de leur destin, sur leur territoire et à l’intérieur de leurs frontières. Les conditions d’acquisition de la citoyenneté assurent l’unité de la nation, et la transmission entre les générations. La séparation est géographique, respectueuse des cultures, des civilisations, de la diversité collective des peuples.

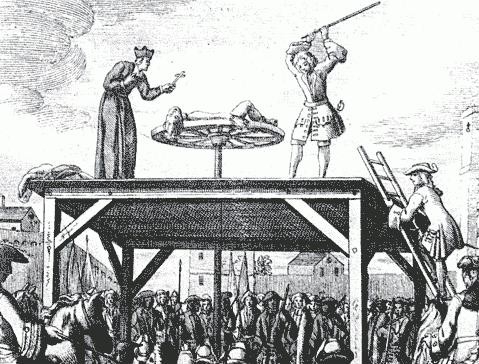

Il faut bien avouer que les tâches allouées aux bourreaux ne sont pas d’ordre à lui attirer toutes les sympathies. En plus d’exécuter les condamnés par des peines jugées parfois comme infamantes, il est d’usage qu’il chasse des rues mendiants, lépreux et animaux errants. Il touche une taxe sur la prostitution. C’est lui qui nettoie la place du marché une fois celui-ci terminé. Il dispose de plus du droit de havage sur toutes les marchandises entrant dans la ville, c'est-à-dire qu’il prélève une certaine quantité de denrées à chaque marchand venant vendre au marché, ce qui est très mal accepté par ceux-ci en vertu de l’impureté supposée de l’exécuteur. Le bourreau se bat continuellement contre les préjugés et les violences éventuelles dont il peut être l’objet de la part de la population et il a, comme les nobles, le droit de porter l’épée (plus pour se protéger que par honneur…). Certaines personnes passent outre cette marginalité pour aller se faire soigner chez les bourreaux qui, en complément de leur activité, pratiquent la médecine ou la chirurgie, forts de leur connaissance du corps humain. Les cadavres des condamnés leur servent parfois de complément de revenus : ils les revendent aux chirurgiens (pratique longtemps interdite par l’Eglise), en prélèvent la graisse pour la revendre à ceux qui veulent soigner leurs varices…

Il faut bien avouer que les tâches allouées aux bourreaux ne sont pas d’ordre à lui attirer toutes les sympathies. En plus d’exécuter les condamnés par des peines jugées parfois comme infamantes, il est d’usage qu’il chasse des rues mendiants, lépreux et animaux errants. Il touche une taxe sur la prostitution. C’est lui qui nettoie la place du marché une fois celui-ci terminé. Il dispose de plus du droit de havage sur toutes les marchandises entrant dans la ville, c'est-à-dire qu’il prélève une certaine quantité de denrées à chaque marchand venant vendre au marché, ce qui est très mal accepté par ceux-ci en vertu de l’impureté supposée de l’exécuteur. Le bourreau se bat continuellement contre les préjugés et les violences éventuelles dont il peut être l’objet de la part de la population et il a, comme les nobles, le droit de porter l’épée (plus pour se protéger que par honneur…). Certaines personnes passent outre cette marginalité pour aller se faire soigner chez les bourreaux qui, en complément de leur activité, pratiquent la médecine ou la chirurgie, forts de leur connaissance du corps humain. Les cadavres des condamnés leur servent parfois de complément de revenus : ils les revendent aux chirurgiens (pratique longtemps interdite par l’Eglise), en prélèvent la graisse pour la revendre à ceux qui veulent soigner leurs varices… Les grands changements continuent avec la Révolution. La loi du 13 juin 1793 adoptée par la Convention impose un bourreau par département. Celui-ci recevra un salaire fixe et ne pourra plus prétendre à ses anciens droits féodaux, abolis. Le fait le plus notable est que le bourreau est désormais considéré comme un citoyen comme les autres, ce qui a tendance à faire reculer son statut de paria aux yeux de la population. En 1790, l’Assemblée Nationale décrète l’abolition de la torture, de l’exposition des corps ainsi que l’égalité des supplices, ce qui a comme conséquence de modifier en profondeur les activités des exécuteurs. Ceux-ci utilisent dès 1792 un mode d’exécution unique : la guillotine. Alors que la France est attaquée à ses frontières et que la Révolution se radicalise, le bourreau et sa machine deviennent peu à peu très populaires, ils sont les grands symboles de la libération du peuple et de l’épuration de la société. Le bourreau, qui désormais se salit bien moins les mains avec le nouveau mode d’exécution, devient le « vengeur du peuple » et sa machine à décapiter le « glaive de la liberté ». Il faut dire que la guillotine fonctionne entre 1792 et 1794 à plein régime. A la différence des procédés anciens, elle permet des exécutions continues voire industrielles. Le célèbre bourreau de Paris, Charles-Henri Sanson, décapite ainsi plus de 3000 personnes en 2 ans (dont le roi Louis XVI et nombre de révolutionnaires)… Finalement dégoûtée par les excès sanglants de la période révolutionnaire, la population va vite reprendre à l’égard des bourreaux son antique mépris.

Les grands changements continuent avec la Révolution. La loi du 13 juin 1793 adoptée par la Convention impose un bourreau par département. Celui-ci recevra un salaire fixe et ne pourra plus prétendre à ses anciens droits féodaux, abolis. Le fait le plus notable est que le bourreau est désormais considéré comme un citoyen comme les autres, ce qui a tendance à faire reculer son statut de paria aux yeux de la population. En 1790, l’Assemblée Nationale décrète l’abolition de la torture, de l’exposition des corps ainsi que l’égalité des supplices, ce qui a comme conséquence de modifier en profondeur les activités des exécuteurs. Ceux-ci utilisent dès 1792 un mode d’exécution unique : la guillotine. Alors que la France est attaquée à ses frontières et que la Révolution se radicalise, le bourreau et sa machine deviennent peu à peu très populaires, ils sont les grands symboles de la libération du peuple et de l’épuration de la société. Le bourreau, qui désormais se salit bien moins les mains avec le nouveau mode d’exécution, devient le « vengeur du peuple » et sa machine à décapiter le « glaive de la liberté ». Il faut dire que la guillotine fonctionne entre 1792 et 1794 à plein régime. A la différence des procédés anciens, elle permet des exécutions continues voire industrielles. Le célèbre bourreau de Paris, Charles-Henri Sanson, décapite ainsi plus de 3000 personnes en 2 ans (dont le roi Louis XVI et nombre de révolutionnaires)… Finalement dégoûtée par les excès sanglants de la période révolutionnaire, la population va vite reprendre à l’égard des bourreaux son antique mépris.

Les éditions Payot viennent de rééditer La Renaissance Orientale de Raymond Schwab, le livre de référence sur les débuts et l’impact des études indiennes et orientales sur les sociétés européennes aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Raymond Schawb (1884-1956) était un authentique humaniste aux multiples facettes : il était traducteur (il pratiquait l'hébreu, le hongrois et l'anglais), romancier et poète. L’Orientalisme a été précédé par un mouvement précurseur, dit pré-indianiste, mouvement animé par des missionnaires ou des fonctionnaires portugais, italiens ou français (en particulier, Anquetil-Duperron, 1731-1805) puis par le pouvoir colonial britannique établi dans la péninsule indienne. Pour ce dernier, l’intérêt linguistique était considéré comme une arme politique pour asseoir sa domination sur le pays.

Les éditions Payot viennent de rééditer La Renaissance Orientale de Raymond Schwab, le livre de référence sur les débuts et l’impact des études indiennes et orientales sur les sociétés européennes aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Raymond Schawb (1884-1956) était un authentique humaniste aux multiples facettes : il était traducteur (il pratiquait l'hébreu, le hongrois et l'anglais), romancier et poète. L’Orientalisme a été précédé par un mouvement précurseur, dit pré-indianiste, mouvement animé par des missionnaires ou des fonctionnaires portugais, italiens ou français (en particulier, Anquetil-Duperron, 1731-1805) puis par le pouvoir colonial britannique établi dans la péninsule indienne. Pour ce dernier, l’intérêt linguistique était considéré comme une arme politique pour asseoir sa domination sur le pays.