Review:

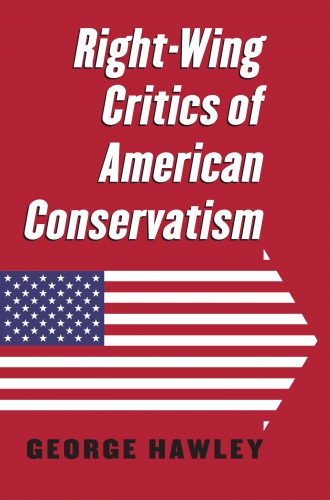

George Hawley

Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism [2]

Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 2016

Most academic studies of White Nationalism and the New Right do not rise above politically correct sneers and smears. They read like ADL or SPLC reports fed through a postmodern buzzword generator. Thus the growing number of serious and balanced academic studies and White Nationalism and the New Right are signs of our rising cultural profile. It is increasingly difficult to dismiss us.

For instance, The Struggle for the World: Liberation Movements for the 21st Century [3]

For instance, The Struggle for the World: Liberation Movements for the 21st Century [3], the 2010 Stanford University Press book on anti-globalization movements by Charles Lindholm and José Pedro Zúquete contains a quite balanced and well-informed chapter on the European New Right. (See Michael O’Meara’s review here [4].) Moreover, Zúquete’s 2007 Syracuse University Press volume Missionary Politics in Contemporary Europe [5]

contains extensive chapters on the French National Front and Italy’s Northern League.

Political scientist George Hawley’s new book Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism is another important contribution to this literature, devoting a chapter to the European New Right and another chapter to White Nationalism. I’m something of an expert in these fields, and in my judgment, Hawley’s research is deft, thorough, and accurate. His writing is admirably clear, and his analysis is quite penetrating.

Naturally, the first thing I did was flip to the index to look for my own name, and, sure enough, on page 265 I found the following:

In recent years, elements of the radical right in the United States have exhibited greater interest in right-wing ideas from continental Europe. In 2010, the North American New Right was founded by Greg Johnson, the former editor of the Occidental Quarterly. While clearly focused on promoting white nationalism in the United States, the North American New Right is heavily influenced by both Traditionalism and the European New Right, and its website (http://www.counter-currents.com/) regularly includes translations from many European New Right intellectuals. The site also embraces the New Right’s idea of metapolitics, noting that the time will not be right for white nationalists to engage in more conventional political activities until a critical number of intellectuals have been persuaded that their ideas are morally and intellectually correct.

The work of my friends at Arktos in bringing out translations of European New Right thinkers is also mentioned on page 241.

Hawley’s definitions of Right and Left come from Paul Gottfried, although they accord exactly with my own views and those of Jonathan Bowden: the Left treats equality as the highest political value. The Right does not regard equality as the highest political value, although there is a range of opinions about what belongs in that place (pp. 11-12). Libertarians, for instance, regard individual liberty as more important than equality. White Nationalists think that both liberty and equality have some value, but racial health and progress trump them both.

In chapter 1, Hawley argues that modern American conservatism was defined by William F. Buckley and National Review in the 1950s. The conservative movement was a coalition of free market capitalists, Christians, and foreign policy hawks. Hawley points out that based on ideology alone, there is no necessary reason why any of these groups would be Right wing or allied with each other. Indeed, the pre-World War II “Old Right” of people like Albert Jay Nock and H. L. Mencken tended to be anti-interventionist, irreligious, and economically populist and protectionist rather than free market. National Review was also philo-Semitic from the start and increasingly anti-racist, whereas the pre-War American Right had strong racialist and anti-Semitic elements. What unified the National Review coalition was not a common ideology but a common enemy: Communism.

In chapter 1, Hawley argues that modern American conservatism was defined by William F. Buckley and National Review in the 1950s. The conservative movement was a coalition of free market capitalists, Christians, and foreign policy hawks. Hawley points out that based on ideology alone, there is no necessary reason why any of these groups would be Right wing or allied with each other. Indeed, the pre-World War II “Old Right” of people like Albert Jay Nock and H. L. Mencken tended to be anti-interventionist, irreligious, and economically populist and protectionist rather than free market. National Review was also philo-Semitic from the start and increasingly anti-racist, whereas the pre-War American Right had strong racialist and anti-Semitic elements. What unified the National Review coalition was not a common ideology but a common enemy: Communism.

In chapter 2, Hawley also documents the role of social mechanisms like purges in defining post-war conservatism. Buckley set the pattern early on by purging Ayn Rand and the Objectivists (for being irreligious) and the John Birch Society (for being conspiratorial and cranky), going on in later years to purge anti-Semites, immigration restrictionists, anti-interventionists, race realists, etc. The same pattern was followed with the firing of race realists Sam Francis from The Washington Times and Jason Richwine from the Heritage Foundation. Indeed, many of the leading figures in the movements Hawley chronicles were purged from mainstream conservatism.

Mainstream conservatism embraces globalization through free trade, immigration, and military interventionism. Thus Hawley devotes chapter 3, “Small is Beautiful,” to conservative critics of globalization, with discussions of the Southern Agrarians, including Richard Weaver and Wendell Berry, communitarian sociologists Robert Nisbet and Christopher Lasch, and economic localists Wilhelm Röpke and E. F. Schumacher. I spent a good chunk of my 20s reading this kind of literature, as well as the libertarian and paleoconservative writers Hawley discusses in later chapters. Thus Hawley’s book can serve as an introduction and a syllabus to a lot of the Anglophone literature that I traversed before coming to my present views.

The Southern Agrarians are particularly interesting, because of they were the most radical school of American conservatism, offering a genuinely anti-liberal and anti-modernist critique of Americanism, with many parallels to what later emerged from the European New Right. The Agrarians also understood the importance of metapolitics. Unfortunately, they were primarily a literary movement and had no effect on political policy. Although I am not a Southerner, I spent a lot of time reading first generation Agrarians like Allen Tate, Donald Davidson, and John Crowe Ransom, plus Weaver, Berry, and Marion Montgomery, and their influence made me quite receptive to the European New Right.

Christians form an important although subaltern bloc in the conservative coalition, thus Hawley devotes chapter 4 to a brief discussion of “Godless Conservatism,” i.e., attempts to make non-religious cases for conservatism. Secular cases for conservatism will only become more important as Christianity continues to decline in America. (Hawley deals with neopagan and Traditionalist alternatives to Christianity in his chapter on the European New Right.)

Chapter 5, “Ready for Prime Time?” is devoted to mainstream libertarianism, including Milton Friedman, the Koch Brothers, the Cato Institute, Reason magazine, the Ron Paul movement, and libertarian youth organizations. Chapter 6, “Enemies of the State,” deals with more radical strands of libertarianism, including 19th-century American anarchists like Josiah Warren and Lysander Spooner, the Austrian School of economics, Murray Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Lew Rockwell, the Mises Institute, and the Libertarian Party. Again, Hawley has read widely with an unfailing eye for essentials.

Chapter 5, “Ready for Prime Time?” is devoted to mainstream libertarianism, including Milton Friedman, the Koch Brothers, the Cato Institute, Reason magazine, the Ron Paul movement, and libertarian youth organizations. Chapter 6, “Enemies of the State,” deals with more radical strands of libertarianism, including 19th-century American anarchists like Josiah Warren and Lysander Spooner, the Austrian School of economics, Murray Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Lew Rockwell, the Mises Institute, and the Libertarian Party. Again, Hawley has read widely with an unfailing eye for essentials.

I went through a libertarian phase in my teens and 20s, and I understand from the inside how someone can move from libertarian individualism to racial nationalism. In 2009, when I was editor of The Occidental Quarterly, I sensed that the Ron Paul and Tea Party movements would eventually send many disillusioned libertarians in the direction of White Nationalism. Thus, to encourage our best minds to think through this connection and develop arguments that might aid the conversion process, TOQ sponsored an essay contest on Libertarianism and Racial Nationalism [6]. Since 2012, this trend has markedly accelerated. Thus I highly recommend Hawley’s chapters to White Nationalists who lack a libertarian background and wish to understand this increasingly important “post-libertarian” strand of the Alternative Right.

Chapter 7, “Nostalgia as a Political Platform,” deals with the paleoconservative movement, covering its debts to the pre-War Old Right, M. E. Bradford, Patrick Buchanan, Thomas Fleming and Chronicles magazine, Sam Francis, Joe Sobran, the paleo-libertarian moment, and Paul Gottfried.

Paleoconservatism is defined in opposition to neoconservatism, the largely Jewish intellectual movement that largely took over mainstream conservatism by the 1980s, aided by William F. Buckley who dutifully purged their opponents. Since the neoconservatives are largely Jewish, and many of the founders were ex-Marxists or Cold War liberals, their ascendancy has meant the subordination of Christian conservatives and free marketeers to the hawkish interventionist wing of the movement. Now that the Cold War is over, the primary concern of neoconservative hawks is tricking Americans into fighting wars for Israel.

Paleoconservatism is defined in opposition to neoconservatism, the largely Jewish intellectual movement that largely took over mainstream conservatism by the 1980s, aided by William F. Buckley who dutifully purged their opponents. Since the neoconservatives are largely Jewish, and many of the founders were ex-Marxists or Cold War liberals, their ascendancy has meant the subordination of Christian conservatives and free marketeers to the hawkish interventionist wing of the movement. Now that the Cold War is over, the primary concern of neoconservative hawks is tricking Americans into fighting wars for Israel.

Paleoconservatives, by contrast, are actually conservatives. They are defenders of Western civilization and its moral traditions. Many of them are Christians, but not all of them. To a man, they reject multiculturalism and open borders. They are populist-nationalist opponents of economic globalization and political empire-building. Most of them are realists about racial differences.

The paleocons, therefore, are the movement that is intellectually closest to White Nationalism. Indeed, Sam Francis is now seen as a founding figure in contemporary White Nationalism, and both Gottfried and Sobran have spoken at White Nationalist events. Paleoconservatives were also the first Americans to pay sympathetic attention to the European New Right. Thus it makes sense that Hawley places his chapter on paleoconservatism before his chapters on the European New Right and White Nationalism.

Hawley is right that paleoconservatism is basically a spent force. Its leading figures are dead or elderly. Aside from Patrick Buchanan, the movement never had access to the mainstream media and publishers. Unlike mainstream conservative and neoconservative institutions, the paleocons never had large donors and foundations on their side. Beyond that, there is no next generation of paleocons. Instead, their torch is being carried forward by White Nationalists or the more nebulously defined “Alternative Right.”

Chapter 8, “Against Capitalism, Christianity, and America,” surveys the European New Right, beginning with the Conservative Revolutionaries Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck; the Traditionalism of René Guénon and Julius Evola; and finally the New Right proper of Alain de Benoist, Guillaume Faye, and Alexander Dugin.

Chapter 9, “Voices of the Radical Right,” covers White Nationalism in America, with discussions of progressive era racialists like Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard; contemporary race realism; the rise and decline of such organizations as the KKK, American Nazi Party, Aryans Nations, and the National Alliance; the world of online White Nationalism; and Kevin MacDonald’s work on the Jewish question — which brings us up to where we started, namely the task of forging a North American New Right.

Chapter 9, “Voices of the Radical Right,” covers White Nationalism in America, with discussions of progressive era racialists like Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard; contemporary race realism; the rise and decline of such organizations as the KKK, American Nazi Party, Aryans Nations, and the National Alliance; the world of online White Nationalism; and Kevin MacDonald’s work on the Jewish question — which brings us up to where we started, namely the task of forging a North American New Right.

Hawley’s concluding chapter 10 deals with “The Crisis of Conservatism.” Neoconservatism has, of course, been largely discredited by the debacle in Iraq. Since the Republicans are the de facto party of whites, especially white Christians with families, the deeper and more systemic challenges to the conservative coalition include the decline of Christianity in America, the decline of marriage and the family, and especially the growing non-white population, which overwhelmingly supports progressive policies. The conservative electorate is shrinking, and if it continues to decline, it will eventually be impossible for Republicans to be elected, which means the end of conservative political policies.

There is, however, a deeper cause of the crisis of conservatism. The decline of the family and the growth of the non-white electorate are the predictable results of government policies — policies that conservatives did not resist and that they will not try to roll back, ultimately because conservatives are more committed to classical liberal principles than the preservation of their own political power, which can only be secured by “collectivist,” indeed “racist” measures to preserve the white majority. Conservatives will conserve nothing [7] until they get over their ideological commitment to liberal individualism.

Hawley predicts that as the conservative movement breaks down, some Americans will turn toward more radical Right-wing ideologies, leading to greater political polarization and instability. Of the ideologies Hawley surveys, he thinks the localists, secularists, libertarian anarchists, paleocons, and European New Rightists have the least political potential. Hawley thinks that the moderate libertarians have the most political potential, largely because they are closest to the existing Republican Party. Unfortunately, libertarian radical individualism would only accelerate the decline of the family, Christianity, and the white electorate.

Of all the movements Hawley surveys, only White Nationalism would address the causes of the decline of the white family and the white electorate. But Hawley thinks that White Nationalism faces immense challenges, although the continued decline of the conservative movement might also present us with great opportunities:

Explicit white nationalism is surely the most aggressively marginalized ideology discussed here. As we have seen, advocating racism is perhaps the fastest way for a politician, pundit, or public intellectual to find himself or herself a social pariah. That being the case, there is little chance that transparent white racism will again become a major political force in the United States in the immediate future. However, the fact that antiracists on the right and left are extraordinarily vigilant in their effort to drive racists from public discourse can be viewed as evidence that they believe such views could once again have a large constituency, should racists ever again be allowed to reenter the mainstream public debate. Whether their fears in this regard are justified is impossible to determine at this time. What we should remember, however, is that the marginalization of the racist right in America was largely possible thanks to cooperation from the mainstream conservative movement, which has frequently jettisoned people from its ranks for openly expressing racist views. If the mainstream conservative movement loses its status as the gatekeeper on the right, white nationalism may be among the greatest beneficiaries, though even in this case it will face serious challenges. (p. 291)

Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism is an important academic study, but it has a significant oversight. The meteoric rise of Donald Trump illustrates the power of another Right-wing alternative to American conservatism, namely populism. Populism is a genuinely Right-wing movement, because although it is critical of economic and political inequality as threats to the integrity of the body politic, populism is nationalistic. It does not regard citizens and foreigners as of equal worth.

I also noticed a couple of smaller mistakes. F. A. Hayek is twice referred to as a Jew, which is false, and on page 40 Hawley refers to Young Americans for Liberty when he means Young Americans for Freedom. Hawley uses the repulsive euphemism “undocumented immigrant” and repeatedly uses the word “vicious” to describe ideas he dislikes, but as a whole his book is relatively free of the tendentious jargon of liberal academics.

I highly recommend Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism [2]. Hawley is clearly not a friend of conservatism or White Nationalism. He’s something far more useful: a frank and fair-minded critic. Conservatives, of course, lack the capacity for self-criticism and self-preservation. So they will ignore him, to their detriment. But White Nationalists will read him and profit from it.

Dans son roman «Never say anything – NSA», Michael Lüders nous montre magistralement que nous aussi, nous vivons dans ce monde et que chacun d’entre nous porte une responsabilité envers l’histoire et les générations futures.

Dans son roman «Never say anything – NSA», Michael Lüders nous montre magistralement que nous aussi, nous vivons dans ce monde et que chacun d’entre nous porte une responsabilité envers l’histoire et les générations futures. Michael Lüders, en tant que spécialiste du Proche-Orient présente ces informations spécifiques sous forme de roman. Ces faits n’auraient probablement jamais pu être publiés sous forme d’un travail journalistique. Il profite de ses connaissances en matière de style littéraire, ce qui permet au lecteur de s’identifier avec Sophie. Il ressent comme elle et souffre avec elle, surtout parce que Sophie reste fidèle à sa volonté et à son devoir journalistique de découvrir la vérité. Cela donne de l’espoir, quels que soient les abîmes bien réels relatés dans le roman: tant qu’il y aura des gens comme Sophie et d’autres qui lui viennent en aide dans les pires situations, le monde ne sera pas perdu. Cela nonobstant tous les raffinements des techniques de surveillance et d’espionnage utilisés à poursuivre Sophie pour la faire tomber et s’en débarrasser.

Michael Lüders, en tant que spécialiste du Proche-Orient présente ces informations spécifiques sous forme de roman. Ces faits n’auraient probablement jamais pu être publiés sous forme d’un travail journalistique. Il profite de ses connaissances en matière de style littéraire, ce qui permet au lecteur de s’identifier avec Sophie. Il ressent comme elle et souffre avec elle, surtout parce que Sophie reste fidèle à sa volonté et à son devoir journalistique de découvrir la vérité. Cela donne de l’espoir, quels que soient les abîmes bien réels relatés dans le roman: tant qu’il y aura des gens comme Sophie et d’autres qui lui viennent en aide dans les pires situations, le monde ne sera pas perdu. Cela nonobstant tous les raffinements des techniques de surveillance et d’espionnage utilisés à poursuivre Sophie pour la faire tomber et s’en débarrasser.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Le livre récent de Christian E. Roques

Le livre récent de Christian E. Roques

Au nombre des grands mythes transversaux européens est celui de la cavalcade surnaturelle menée par un chef divin. Dans le monde germanique c'est la

Au nombre des grands mythes transversaux européens est celui de la cavalcade surnaturelle menée par un chef divin. Dans le monde germanique c'est la

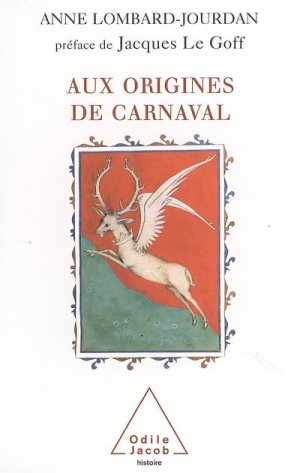

L'ouvrage revient alors sur la place dévolue au cerf dans la maison de France à travers les légendes mettant en scène ses membres et des cerfs surnaturels souvent liés à la figure christique, les illustrations et la présence physique des cerfs dans les demeures royales, et les métaphores littéraires qui rapprochent monarque et cervidé. C'est dans le cerf ailé (présenté en couverture) que les rois trouvent leur emblème totémique, lié non pas, comme la fleur de lys, au Royaume de France dans son entièreté, mais à la fonction monarchique en particulier. Enfin, le don de guérison des écrouelles, le rôle thaumaturgique du roi, est analysé comme un héritage chamanique lié au culte du dieu-cerf.

L'ouvrage revient alors sur la place dévolue au cerf dans la maison de France à travers les légendes mettant en scène ses membres et des cerfs surnaturels souvent liés à la figure christique, les illustrations et la présence physique des cerfs dans les demeures royales, et les métaphores littéraires qui rapprochent monarque et cervidé. C'est dans le cerf ailé (présenté en couverture) que les rois trouvent leur emblème totémique, lié non pas, comme la fleur de lys, au Royaume de France dans son entièreté, mais à la fonction monarchique en particulier. Enfin, le don de guérison des écrouelles, le rôle thaumaturgique du roi, est analysé comme un héritage chamanique lié au culte du dieu-cerf.

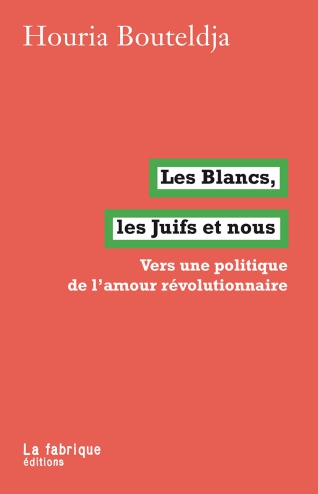

On retrouve ici une forme du mythe du « Bon sauvage », l’homme bon et non corrompu par la civilisation industrielle mondialiste qui n’est pas dépourvu d’intérêt. Même s’il ne faut pas être naïf en surestimant les capacités de résistance des individus qui se confronteront aux valeurs coloniales de l’oligarchie mondiale.

On retrouve ici une forme du mythe du « Bon sauvage », l’homme bon et non corrompu par la civilisation industrielle mondialiste qui n’est pas dépourvu d’intérêt. Même s’il ne faut pas être naïf en surestimant les capacités de résistance des individus qui se confronteront aux valeurs coloniales de l’oligarchie mondiale. La jouissance de l’idée de métisser obligatoirement les anciens dominants : blancs, patrons, curés, beaufs, juifs ( une forme de quintessence, sous sa forme sioniste, de blanc, intouchable moralement et en même temps colonisateur sans vergogne et au cœur du système occidental comme Avant-garde de la République !) est une idée dangereuse. Métisser de force l’autre, imposer ses gènes, ses normes culturelles, c’est aussi prendre le risque d’y perdre son identité même si l’on ressent une certaine jouissance morbide de nuisance ( posture d’un antiracisme « tordu » d’origine forcément blanche, culpabilisée, chargée de haine de soi). Il faut se libérer de cette vision suicidaire et mondialiste pour se réenraciner et accéder à l’autonomie économique et à l’imposition de limites, de digues régulatrices, seule issue éthiquement et chrétiennement valable. Pas de multiculturalisme paternaliste imposé d’en haut, mais des cultures multiples et enracinées vivantes et autonomes

La jouissance de l’idée de métisser obligatoirement les anciens dominants : blancs, patrons, curés, beaufs, juifs ( une forme de quintessence, sous sa forme sioniste, de blanc, intouchable moralement et en même temps colonisateur sans vergogne et au cœur du système occidental comme Avant-garde de la République !) est une idée dangereuse. Métisser de force l’autre, imposer ses gènes, ses normes culturelles, c’est aussi prendre le risque d’y perdre son identité même si l’on ressent une certaine jouissance morbide de nuisance ( posture d’un antiracisme « tordu » d’origine forcément blanche, culpabilisée, chargée de haine de soi). Il faut se libérer de cette vision suicidaire et mondialiste pour se réenraciner et accéder à l’autonomie économique et à l’imposition de limites, de digues régulatrices, seule issue éthiquement et chrétiennement valable. Pas de multiculturalisme paternaliste imposé d’en haut, mais des cultures multiples et enracinées vivantes et autonomes

o enfin dans la troisième partie,

o enfin dans la troisième partie,

Exactement. Je vois dans le populisme, du moins dans celui qui est exprimé par le peuple, une réaction face à sa propre décomposition sociale. Nous courons aujourd’hui vers l’abîme et le peuple, en bon animal politique, rue dans les brancards. C’est cet instinct de conservation désespéré que l’on nomme “populisme”. Ce qu’il faut bien comprendre, c’est qu’un peuple n’est pas uniquement un être politique ou un être social, c’est aussi une relation vivante entre les individus qui le composent. C’est une sociabilité qui naît de la similitude. Cette importance de la similitude comme condition de la sociabilité est aujourd’hui l’objet d’un refoulement collectif. On ne cherche plus à être semblable et à imiter, on veut être différent et inimitable.

Exactement. Je vois dans le populisme, du moins dans celui qui est exprimé par le peuple, une réaction face à sa propre décomposition sociale. Nous courons aujourd’hui vers l’abîme et le peuple, en bon animal politique, rue dans les brancards. C’est cet instinct de conservation désespéré que l’on nomme “populisme”. Ce qu’il faut bien comprendre, c’est qu’un peuple n’est pas uniquement un être politique ou un être social, c’est aussi une relation vivante entre les individus qui le composent. C’est une sociabilité qui naît de la similitude. Cette importance de la similitude comme condition de la sociabilité est aujourd’hui l’objet d’un refoulement collectif. On ne cherche plus à être semblable et à imiter, on veut être différent et inimitable.

'Important if true” was the phrase that the 19th-century writer and historian Alexander Kinglake wanted to see engraved above church doors. It rings loud in the ears as one reads the latest book by

'Important if true” was the phrase that the 19th-century writer and historian Alexander Kinglake wanted to see engraved above church doors. It rings loud in the ears as one reads the latest book by

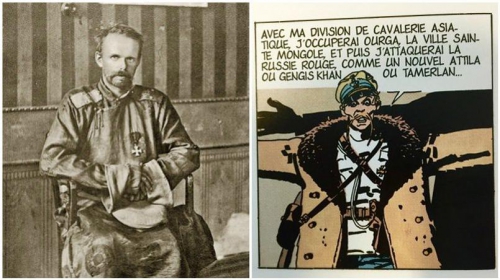

Francis Bergeron, journaliste et écrivain, est un passionné. Sa passion pour l’écrivain Henri Béraud l’a conduit à présider l’Association Rétaise des Amis d’Henri Béraud. Sa passion pour Hergé et Tintin l’a poussé à collectionner tout ce qui se rapporte au célèbre reporter belge et à son auteur mais aussi à écrire ce Hergé, le voyageur immobile. Au préalable, Francis Bergeron avait déjà rédigé un Hergé dans la collection Qui suis-je ? publiée par les éditions Pardès.

Francis Bergeron, journaliste et écrivain, est un passionné. Sa passion pour l’écrivain Henri Béraud l’a conduit à présider l’Association Rétaise des Amis d’Henri Béraud. Sa passion pour Hergé et Tintin l’a poussé à collectionner tout ce qui se rapporte au célèbre reporter belge et à son auteur mais aussi à écrire ce Hergé, le voyageur immobile. Au préalable, Francis Bergeron avait déjà rédigé un Hergé dans la collection Qui suis-je ? publiée par les éditions Pardès.

Un livre très intéressant vient de paraître, publié chez un petit éditeur, c’est Silence Coupable de Céline Pina [1]. L’auteur est une élue locale PS, qui fut conseillère régionale d‘Île de France. Son livre se veut un cri d‘alarme, mais aussi un cri de détresse, quant à l’abandon de la laïcité qu’elle perçoit et qu’elle analyse dans plusieurs domaines. Elle dénonce une politique d’abandon de la part des politiques, qui ne peut que mener le pays soit à la tyrannie soit à la guerre civile.

Un livre très intéressant vient de paraître, publié chez un petit éditeur, c’est Silence Coupable de Céline Pina [1]. L’auteur est une élue locale PS, qui fut conseillère régionale d‘Île de France. Son livre se veut un cri d‘alarme, mais aussi un cri de détresse, quant à l’abandon de la laïcité qu’elle perçoit et qu’elle analyse dans plusieurs domaines. Elle dénonce une politique d’abandon de la part des politiques, qui ne peut que mener le pays soit à la tyrannie soit à la guerre civile. Le premier chapitre s’ouvre sur une dénonciation au vitriol des méfaits du clientélisme qui fut pratiqué tant par les partis de « gauche » que par ceux de droite. On sent ici nettement que c’est l’expérience de l’élue de terrain qui parle. La description des petites comme des grandes compromissions, que ce soit lors du « salon de la femme musulmane » ou dans l’éducation nationale (et le rôle funeste à cet égard de la Ligue de l’enseignement ou de la Ligue des droit de l’Homme sont ici très justement pointés du doigt) montre que Céline Pina connaît parfaitement son sujet. Il est clair que certains élus cherchent à s’allier avec les islamistes tant pout avoir le calme ans un quartier que pour faire jouer une « clientèle » électorale. Le procédé est anti-démocratique. Il est surtout suicidaire dans le contexte actuel. Malek Boutih l’avait déjà énoncé et Céline Pina enfonce le clou et donne des exemples.

Le premier chapitre s’ouvre sur une dénonciation au vitriol des méfaits du clientélisme qui fut pratiqué tant par les partis de « gauche » que par ceux de droite. On sent ici nettement que c’est l’expérience de l’élue de terrain qui parle. La description des petites comme des grandes compromissions, que ce soit lors du « salon de la femme musulmane » ou dans l’éducation nationale (et le rôle funeste à cet égard de la Ligue de l’enseignement ou de la Ligue des droit de l’Homme sont ici très justement pointés du doigt) montre que Céline Pina connaît parfaitement son sujet. Il est clair que certains élus cherchent à s’allier avec les islamistes tant pout avoir le calme ans un quartier que pour faire jouer une « clientèle » électorale. Le procédé est anti-démocratique. Il est surtout suicidaire dans le contexte actuel. Malek Boutih l’avait déjà énoncé et Céline Pina enfonce le clou et donne des exemples.

Soeben ist der achte Band unserer Schriftenreihe BN-Anstoß erschienen: „Aufstand des Geistes. Konservative Revolutionäre im Profil“ vereint zehn Portraits über Denker, die wir wiederentdecken müssen.

Soeben ist der achte Band unserer Schriftenreihe BN-Anstoß erschienen: „Aufstand des Geistes. Konservative Revolutionäre im Profil“ vereint zehn Portraits über Denker, die wir wiederentdecken müssen.

Oui, Oskar Freysinger idéalise le pays qui a accueilli son père, immigré autrichien, dit Slobodan Despot dans son avant-propos d'éditeur du dernier livre d'Oskar Freysinger.Ce que je crois, c'est que les lois non écrites sont très présentes dans l'imaginaire collectif des Suisses, écrit Eric Werner dans la post-face.

Oui, Oskar Freysinger idéalise le pays qui a accueilli son père, immigré autrichien, dit Slobodan Despot dans son avant-propos d'éditeur du dernier livre d'Oskar Freysinger.Ce que je crois, c'est que les lois non écrites sont très présentes dans l'imaginaire collectif des Suisses, écrit Eric Werner dans la post-face.

H

H Auf der einen Seite stehen hier die Eurokraten und ihre Claqueure, die selbst dort, wo sie die Fehler ihre Baus erkennen, keine Korrektur im Blick haben, auf der anderen Seite die Europakritiker, die entweder zu achtundzwanzig einzelnen Nationalstaaten zurückwollen – immer noch die realistischste Nicht-Lösung; oder aber sich in die Charles de Gaulle zugeschriebene Formulierung eines „Europas der Vaterländer“ flüchten, von dem keiner weiß, wie es aussehen, noch weniger was es zusammenhalten soll.

Auf der einen Seite stehen hier die Eurokraten und ihre Claqueure, die selbst dort, wo sie die Fehler ihre Baus erkennen, keine Korrektur im Blick haben, auf der anderen Seite die Europakritiker, die entweder zu achtundzwanzig einzelnen Nationalstaaten zurückwollen – immer noch die realistischste Nicht-Lösung; oder aber sich in die Charles de Gaulle zugeschriebene Formulierung eines „Europas der Vaterländer“ flüchten, von dem keiner weiß, wie es aussehen, noch weniger was es zusammenhalten soll. Es bleibt die Frage der „Reichfähigkeit“ der Deutschen. Dass wir in der Lage sind über den eigenen Tellerrand hinauszublicken und ganz Europa im Blick zu haben, dies haben wir in unserer Geschichte mehrfach bewiesen, zuletzt ironischerweise unter Angela Merkel in der Eurokrise, während der es den Deutschen als einzigen nicht nur um kurzfristige Eigeninteressen ging. Zusammen mit unserer Mittellage und unserer relativen Macht betrachtet, ist Sander daher uneingeschränkt beizupflichten, dass eine europäische Ordnung nur von Deutschland ausgehen und um Deutschland herum gestaltet werden kann.

Es bleibt die Frage der „Reichfähigkeit“ der Deutschen. Dass wir in der Lage sind über den eigenen Tellerrand hinauszublicken und ganz Europa im Blick zu haben, dies haben wir in unserer Geschichte mehrfach bewiesen, zuletzt ironischerweise unter Angela Merkel in der Eurokrise, während der es den Deutschen als einzigen nicht nur um kurzfristige Eigeninteressen ging. Zusammen mit unserer Mittellage und unserer relativen Macht betrachtet, ist Sander daher uneingeschränkt beizupflichten, dass eine europäische Ordnung nur von Deutschland ausgehen und um Deutschland herum gestaltet werden kann.

Over zijn gewezen partij lezen we iets anders. ‘De alomtegenwoordigheid van de religie in de jeugdjaren en de opleiding van heel veel partijleden verklaart heel veel van de verkramping waarvan Groen tot op heden blijk geeft in elke discussie over multiculturalisme en islam.’ Het lijkt niet echt te kloppen met wat hij over zijn exit bij Groen zei in

Over zijn gewezen partij lezen we iets anders. ‘De alomtegenwoordigheid van de religie in de jeugdjaren en de opleiding van heel veel partijleden verklaart heel veel van de verkramping waarvan Groen tot op heden blijk geeft in elke discussie over multiculturalisme en islam.’ Het lijkt niet echt te kloppen met wat hij over zijn exit bij Groen zei in

El proceso de tercermundización a través de la Globalización es ya evidente en España. En otros países es menos evidente pero se da igualmente: las condiciones laborales en la exitosa Alemania –que ha bajado sus índices de paro sin aumentar el número de horas trabajadas– son ya tercermundistas para una buena parte de los trabajadores. En Europa, si el proceso de Globalización no se detiene, más de cien millones de trabajadores van a quedar sometidos de nuevo a condiciones parecidas a las del capitalismo salvaje de hace dos siglos. Y, cuando la cultura social y laboral europea haya sido destruida, el capitalismo salvaje dominará sin oposición en el mundo entero.

El proceso de tercermundización a través de la Globalización es ya evidente en España. En otros países es menos evidente pero se da igualmente: las condiciones laborales en la exitosa Alemania –que ha bajado sus índices de paro sin aumentar el número de horas trabajadas– son ya tercermundistas para una buena parte de los trabajadores. En Europa, si el proceso de Globalización no se detiene, más de cien millones de trabajadores van a quedar sometidos de nuevo a condiciones parecidas a las del capitalismo salvaje de hace dos siglos. Y, cuando la cultura social y laboral europea haya sido destruida, el capitalismo salvaje dominará sin oposición en el mundo entero.

Syndicalisten en sociologen hebben nooit bij bosjes rondgelopen in de Vlaamse Beweging. Victor Leemans bundelde de drie eigenschappen. Hij was een Vlaams-nationalist, studeerde sociologie, en ijverde voor het samensmelten van de katholieke en de meer autoritair-Vlaamse syndicaten tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog.

Syndicalisten en sociologen hebben nooit bij bosjes rondgelopen in de Vlaamse Beweging. Victor Leemans bundelde de drie eigenschappen. Hij was een Vlaams-nationalist, studeerde sociologie, en ijverde voor het samensmelten van de katholieke en de meer autoritair-Vlaamse syndicaten tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog.