mardi, 14 février 2012

Gottfried Benn, El médico

Gottfried Benn, El médico

Ex: http://griseldagarcia.blogspot.com/

La dulce corporalidad se me pega

como una costra contra el borde del paladar.

Lo que alguna vez tembló entre humores y carnes blandas

alrededor del hueso calcáreo,

se cuece a fuego lento, con leche y sudor en mi nariz.

Yo sé cómo las putas y las madonas olfatean

en busca de una cuadrilla en las mañanas al despertar

por la marea de su sangre –

y entran a mi despacho los señores,

para quienes la estirpe se hizo cicatriz –

la mujer piensa que la preñan

para levantarla a la colina de un dios;

pero el hombre cicatrizó,

su cerebro sale a cazar arriba la bruma de una estepa,

y silencioso ingresa su semen.

Yo vivo frente al cuerpo: y en el centro

se pega por todas partes la vergüenza. Allí también

husmea el cráneo. Yo presiento: algún día

la grieta y el temblor

se abrirán en la frente apuntando al cielo.

II

La corona de la creación, el cerdo, el hombre –:

¡rehuye junto a otros animales!

Con ladillas de diecisiete años

entre hocicos nauseabundos, aquí y allá,

enfermedades intestinales y pensión alimenticia,

infusorios y hembras,

con cuarenta comienza a correr la vejiga –:

¿piensan ustedes que por semejante tubérculo la tierra se estiró

del sol a la luna? ¿A qué ladran entonces?

Hablan desde el alma, ¿qué es su alma?

¿Se caga la vieja en su cama noche a noche? –

¿se embadurna el viejo los blandos muslos?

¿les basta el forraje para maldecir en los intestinos?

¿piensan ustedes que las estrellas engendraron antes felicidad…?

la tierra escupe como desde otros agujeros de fuego,

la sangre brota del hocico –:

tambalea

el arco bajando

condescendiente hacia las sombras.

III

eso se aparea en una cama y se apretuja

y siembra el semen en el surco de la carne

y se siente dios en casa de una diosa. Y el fruto – –:

en muchos casos es deforme de nacimiento:

con marsupios en la espalda, grietas en la faringe,

bizco, sin testículos, por amplias hernias

le escapan los intestinos –; pero no es mucho siquiera,

incluso aquello que al final se hincha sin lesionarse al contacto con la luz,

y a través de los agujeros la tierra gotea:

paseo –: fetos, chusma de la especie –:

se promulga a sí misma. Sentada. –

Dedos se olfatean.

Pasa de uva recogida del diente.

¡Los pececitos de oro – !!! – !

¡Elevación! ¡Ascenso! ¡Canción del Weser!

Lo ordinario es palpable. Dios,

campana de idioteces, levantado sobre la vergüenza –:

¡el buen pastor! – !! – – ¡sentimiento ordinario! –

Y por las noches el macho cabrío salta sobre la cierva.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes, gottfried benn, allemagne, poésie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 11 février 2012

Ernst Jünger in Paris

| Ernst Jünger in Paris: Tobias Wimbauer hält den Bunsenbrenner an des großen Eindeuters Kitschgemälde |

|

Geschrieben von: Till Röcke |

|

Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de/ |

|

Der ästhetische Beobachter Jünger-Nestor Tobias Wimbauer ist dem Pariser Treiben nachgegangen. Das Resultat liegt nun als Band in der akribisch-herzlichen „Bibliotope“-Reihe des Hagener Eisenhut Verlags vor. Dabei steht die bereits bekannte, vor einigen Jahren in der FAZ für Aufmerksamkeit sorgende Untersuchung über die amourösen Spielereien Jüngers im Zentrum. Der vernobelte Lackschuh-Landser hielt alles fest, schließlich war er bekennender Diarist. Die Schwierigkeit dabei: In Jüngers Aufzeichnungen dieser Jahre, den nach dem Krieg publizierten „Strahlungen“, mischen sich Fakten und Fiktion – wie es nun mal der erzählenden Dichtung zu eigen ist, mit den doch eher wahrheitsgetreuen Protokollen in Tagebüchern allerdings weniger zu tun hat. Wimbauers Aufsatz „Kelche sind Körper“ weist den „Strahlungen“ denn auch einen hohen Grad an zusammengeklaubten Liebesmotiven der Weltliteratur nach. Als Pointe erklärt Wimbauer die bekannte „Burgunderszene“ zur Nebelkerze. In dieser Miniatur, ein belletristischer Klassiker obszöner Überhöhung, schildert ein am Gläschen nippender Ich-Erzähler sein tiefenentspanntes Beiwohnen einer Bombardierung. Luftkrieg und Lust, Jünger als universalistischer Ästhet. Denn eigentlich, so Wimbauers Lesart, war es dem Autor daran gelegen, die Liaison mit einer gewissen Sophie Ravoux zu verschleiern. In Kirchhorst wartete schließlich die Frau. Der Phallus von Paris Neben der Erotik sah sich Jünger immer wieder gezwungen, den militärischen Dienstpflichten beizukommen. Die Erschießung eines Deserteurs, unter seinem Kommando durchgeführt, stellt sich auch nach Jahrzehnten der Forschung noch als heiße Sache heraus. Diese bildet den zweiten Schwerpunkt des Sammelbandes, der neben dem Herausgeber noch vier weitere Experten zu Wort kommen lässt. Insgesamt ist festzuhalten, dass Wimbauer souverän zusammenstellt, was das französische Abenteuer an wissenschaftlicher Spiegelung bereithält. Gedanke: Man ist eben nie ganz fertig mit Ernst Jünger. Wilflingen ist noch lange nicht genommen. „Désinvolture“, Schnöselei von hoher Qualität, ist das aus Kennermund oft vorgebrachte Prädikat des Jüngerschen Wesens. Dem ist wohl kaum zu widersprechen, zu sehr war das Vorraussetzung, um ein derart bildgewaltiges Werk zu schaffen. Was davon heute noch übrig ist, was sich aus einer weniger zurückgelehnten und auf Gleichnisgenuss bedachten Perspektive davon noch fruchtbar machen lässt, das weiß irgendwann vielleicht die Jünger-Exegese. Vielleicht auch nicht. Skepsis ist geboten. In diese Richtung zumindest bringt es Textbeiträger Alexander Rubel. Als Jüngers Lebensmotto und künstlerische Daseinsberechtigung mag vorerst Rubels lapidare Feststellung herhalten: „Wer die Welt in ihrer Gesamtheit erfasst, muss sich nicht von ephemeren Ereignissen wie Weltkriegen und Massenvernichtung beunruhigen lassen.“ Tobias Wimbauer (Hg.): Ernst Jünger in Paris. Ernst Jünger, Sophie Ravoux, die Burgunderszene und eine Hinrichtung. Eisenhut Verlag: Hagen Berchum 2011. 12,90 Euro |

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, allemagne, révolution conservatrice, ernst jünger, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes, paris, années 40 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 10 février 2012

Europe 1945

Europe 1945

By A. R. D. Fairburn

Ex: http://counter-currents.com/

And now spring comes to the starved and blackened land

where the tailless abominable angel has spent his passion;

dead roots are twined through the bones of a broken hand;

now death, not Schiaparelli, sets the fashion.

In the twentieth century of the Christian era

the news-hawk camera man, no Botticelli,

walks on this stricken earth with Primavera,

and Europe cries from the heart of her hungry belly.

Ten flattened centuries are heaped with rubble,

ten thousand vultures wheel above the plain;

honour is lost and hope is like a bubble;

life is defeated, thought itself is pain.

But the bones of Charlemagne will rise and dance,

and the spark unquenched will kindle into flame.

And the voices heard by the small maid of France

will speak yet again, and give this void a Name.

Source: http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-FaiColl-t1-body-d2-d4.html#n98 [2]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2012/02/europe-1945/

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : poème, dresde, allemagne, europe, histoire, littérature, lettres, lettres néo-zélandaises, littérature néo-zélandaise |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 09 février 2012

Ernst Jünger @ http://www.centrostudilaruna.it/

Ernst Jünger @ http://www.centrostudilaruna.it/

Sezione multilingue dedicata a Ernst Jünger (29.III.1895-17.II.1998), alla sua opera e al suo pensiero.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, révolution conservatrice, ernst jünger, allemagne, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature allemande, littérature |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 06 février 2012

Le Bulletin célinien n°338 - février 2012

Le Bulletin célinien n°338 - février 2012

Vient de paraître : Le Bulletin célinien n°338. Au sommaire :

Vient de paraître : Le Bulletin célinien n°338. Au sommaire :Marc Laudelout : Bloc-notes

François Marchetti : Mort à crédit en danois

Bilan du cinquantenaire (livres, revues, émissions télévisées, colloques, théâtre)

Öyvind Fahlström : Ma rencontre avec Céline

Jean-Paul Louis : Pascal Pia, critique de Céline

B. C. : Les images du Déluge dans Casse-pipe

Un numéro de 24 pages, 6 euros franco.

Abonnement annuel : 50 €

Le Bulletin célinien, B. P. 70, Gare centrale, BE 1000 Bruxelles.

Le Bulletin célinien n°338 - Bloc-notes

Après 1945, Céline ne souhaitait pas la réédition de ses textes polémiques, y compris Mea culpa (1936) jamais republié de son vivant. Par la suite, c’est à plusieurs reprises que l’ayant droit autorisa sa parution dans des éditions collectives : celle de Balland (1967), puis celle du Club de l’Honnête Homme (1982), et enfin celle des Cahiers Céline (1986). Ce libelle (20 pages dans l’édition princeps) est l’un des textes politiques les plus importants de Céline. C’est à tort qu’on l’a pris, à cause du titre essentiellement, pour une sorte de repentir. « La vraie révolution ça serait bien celle des Aveux », écrit-il pourtant dans ce texte. Au-delà du communisme ¹, la charge vise le matérialisme et l’essence même de l’homme. Tel qu’il est réellement et non pas tel que le rêvent les utopismes totalitaires. À la fin du siècle passé, il se trouvait encore des céliniens pour dénoncer « l’anticommunisme criminel » [sic] de Mea culpa. C’était, on l’aura compris, avant la chute du Mur de Berlin.

Jean-Paul Louis, lui, nous propose aujourd’hui une merveille : la version préparatoire et le texte définitif de Mea culpa, avec la reproduction intégrale du manuscrit ². Le format in-octavo a été judicieusement choisi pour présenter au mieux, folio après folio, le fac-similé du manuscrit, accompagné en regard de sa transposition en haut de page et du passage correspondant au texte final en pied de page. Cette édition scientifique du manuscrit, on la doit sans surprise à Henri Godard, familier des textes céliniens. Dans l’avant-propos, il dit l’intérêt de cette présentation : « On saisit ici visuellement à la fois, dans la graphie, la fièvre d’une écriture toujours improvisée dans l’instant et les états successifs, qui sont en l’occurrence au nombre d’au moins quatre. » Et de constater que « ses formules les plus fortes ou les plus drôles viennent souvent dans une reprise ultérieure. Ses ajouts sont des développements. Quand on a l’occasion de les isoler, ils mettent en évidence les idées auxquelles il tient le plus. » Cette édition, imprimée sur beau papier, met ainsi à l’honneur l’écrivain de combat que fut aussi Céline. Il suffit de relire ce brûlot pour se rendre compte que l’écrivain ne perd pas son talent lorsqu’il trempe sa plume dans le vitriol, bien au contraire. Et ce qui est vrai pour Mea culpa l’est aussi pour Bagatelles pour un massacre qui comporte des pages fulgurantes sur l’enfer soviétique ³, absentes du premier pamphlet. Henri Godard note que celui-ci est bien différent de ceux qui le suivront. C’est vrai en partie seulement car ce « sentiment fraternel » – « quatrième dimension » appelée de ses vœux dans Mea culpa – trouvera dans Les Beaux draps l’expression d’une manière de programme : « Il faut que les enfants des autres vous deviennent presque aussi chers, aussi précieux que les vôtres, que vous pensiez aussi à eux, comme des enfants d’une même famille, la vôtre, la France toute entière. C’est ça le bonheur d’un pays, le vrai bouleversement social, c’est des papas mamans partout. » On est assurément loin, n’en déplaise à ses contempteurs, d’un Céline misanthrope et nihiliste.

Marc LAUDELOUT

1. Même si, rappelons le, la bande-annonce du livre portait en 1936 ce seul mot : « Communisme » (peut-être proposée par Robert Denoël et avalisée par Céline). Le tirage était de 20.000 exemplaires.

2. Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Mea culpa (Version préparatoire et texte définitif. Édition d’Henri Godard avec la reproduction intégrale du manuscrit), Du Lérot, 2011, 104 pages. Tirage limité à 300 exemplaires numérotés sur bouffant ivoiré et quelques exemplaires hors commerce sur Hollande pur chiffon. Cet ouvrage ne sera pas réimprimé. Saluons, une fois encore, le remarquable travail de Jean-Paul Louis, éditeur-imprimeur.

3. Le retour d’URSS s’effectua, comme on sait, sur le paquebot le Meknès. Découverte récente : sur un livre de Panaït Istrati, Le Bureau de placement (1936), lecture de voyage d’une passagère, Céline apporta cette dédicace : « À madame Pierre Ducoudert. Souvenir d’un très agréable voyage après une terrible aventure. LF Céline. »

19:13 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : revue, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, céline |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 31 janvier 2012

Francis Puyalte, le journalisme et Céline

Francis Puyalte, le journalisme et Céline

par Marc Laudelout

Francis Puyalte et Saphia Azzedine ont un point commun : leur livre comporte une épigraphe extraite de Bagatelles pour un massacre. Thème identique de surcroît : « C’est toujours le toc, le factice, la camelote ignoble et creuse qui en impose aux foules, le mensonge toujours ! jamais l’authentique... » (Puyalte) et « Les peuples toujours idolâtrent la merde, que ce soit en musique, en peinture, en phrases, à la guerre ou sur les tréteaux. L’imposture est la déesse des foules. » (Azzedine). La comparaison s’arrête là. Car, pour le reste, l’univers décrit par la beurette (« Guerre des boutons version al-Qaida », dixit un critique) ¹ et celui de Puyalte sont bien différents. Journaliste à Paris-Jour, puis à L’Aurore et au Figaro, Francis Puyalte est aujourd’hui à la retraite. Cela lui confère la liberté de dénoncer sans fard ce qu’il nomme l’inquisition médiatique, et ce à travers des exemples concrets. De l’affaire de Bruay-en-Artois au procès d’Omar Raddad, Puyalte montre comment la presse d’aujourd’hui fabrique des innocents ou des coupables et surtout comment elle parvient à imposer ce qu’il convient de penser. Jamais auparavant un journaliste n’avait aussi franchement révélé ce qui se passe dans les coulisses du quatrième pouvoir. Dans ce livre, il ne traite donc pas d’une autre de ses passions – Céline – qui lui a notamment permis de rencontrer Lucette dont il a recueilli les propos dans deux articles mémorables ². Dans Bagatelles, le mot « imposture » est l’un de ceux qui revient le plus souvent. C’est précisément ce que dénonce Puyalte dans cet ouvrage salué par un (autre) esprit libre : « Une incroyable liberté de ton, de pensée, de critique et de démolition. Un pamphlet vif, argumenté, salubre et dévastateur sur le journalisme, ses dérives, ses conforts intellectuels, ses paresses et ses préjugés. (…) Ces dysfonctionnements et vices du journalisme ont parfois été dénoncés mais jamais avec cette verve... » ³. Savoureux aussi, le premier chapitre consacré à ses débuts dans le journalisme. Il rappelle – ce n’est pas un mince compliment – les pages analogues de François Brigneau dans Mon après-guerre. Voyez plutôt : « Le lecteur ? J’apprendrai vite que ce n’est pas le principal souci de la rédaction en chef, qui planche, dès la fin de la matinée, sur la manchette de la Une. Ce qui importe, c’est un titre accrocheur, vendeur, selon le terme si souvent entendu. Il est vrai qu’un journal est fait pour être vendu, même lorsque l’actualité est pauvre. Alors, faute d’un événement d’intérêt, on va en gonfler un autre qui n’en a aucun. Au départ, il faisait hausser les épaules. À l’arrivée, il fait la manchette. Drôle de situation pour le reporter. À lui la débrouille et non la bredouille. ». On aura compris que c’est un livre décapant, très célinien dans la démarche (« Tout dire ou bien se taire »). Raison pour laquelle, on s’en doute, Francis Puyalte ne sera pas invité dans les médias. Peu importe, son livre existe et fera date.

Francis Puyalte et Saphia Azzedine ont un point commun : leur livre comporte une épigraphe extraite de Bagatelles pour un massacre. Thème identique de surcroît : « C’est toujours le toc, le factice, la camelote ignoble et creuse qui en impose aux foules, le mensonge toujours ! jamais l’authentique... » (Puyalte) et « Les peuples toujours idolâtrent la merde, que ce soit en musique, en peinture, en phrases, à la guerre ou sur les tréteaux. L’imposture est la déesse des foules. » (Azzedine). La comparaison s’arrête là. Car, pour le reste, l’univers décrit par la beurette (« Guerre des boutons version al-Qaida », dixit un critique) ¹ et celui de Puyalte sont bien différents. Journaliste à Paris-Jour, puis à L’Aurore et au Figaro, Francis Puyalte est aujourd’hui à la retraite. Cela lui confère la liberté de dénoncer sans fard ce qu’il nomme l’inquisition médiatique, et ce à travers des exemples concrets. De l’affaire de Bruay-en-Artois au procès d’Omar Raddad, Puyalte montre comment la presse d’aujourd’hui fabrique des innocents ou des coupables et surtout comment elle parvient à imposer ce qu’il convient de penser. Jamais auparavant un journaliste n’avait aussi franchement révélé ce qui se passe dans les coulisses du quatrième pouvoir. Dans ce livre, il ne traite donc pas d’une autre de ses passions – Céline – qui lui a notamment permis de rencontrer Lucette dont il a recueilli les propos dans deux articles mémorables ². Dans Bagatelles, le mot « imposture » est l’un de ceux qui revient le plus souvent. C’est précisément ce que dénonce Puyalte dans cet ouvrage salué par un (autre) esprit libre : « Une incroyable liberté de ton, de pensée, de critique et de démolition. Un pamphlet vif, argumenté, salubre et dévastateur sur le journalisme, ses dérives, ses conforts intellectuels, ses paresses et ses préjugés. (…) Ces dysfonctionnements et vices du journalisme ont parfois été dénoncés mais jamais avec cette verve... » ³. Savoureux aussi, le premier chapitre consacré à ses débuts dans le journalisme. Il rappelle – ce n’est pas un mince compliment – les pages analogues de François Brigneau dans Mon après-guerre. Voyez plutôt : « Le lecteur ? J’apprendrai vite que ce n’est pas le principal souci de la rédaction en chef, qui planche, dès la fin de la matinée, sur la manchette de la Une. Ce qui importe, c’est un titre accrocheur, vendeur, selon le terme si souvent entendu. Il est vrai qu’un journal est fait pour être vendu, même lorsque l’actualité est pauvre. Alors, faute d’un événement d’intérêt, on va en gonfler un autre qui n’en a aucun. Au départ, il faisait hausser les épaules. À l’arrivée, il fait la manchette. Drôle de situation pour le reporter. À lui la débrouille et non la bredouille. ». On aura compris que c’est un livre décapant, très célinien dans la démarche (« Tout dire ou bien se taire »). Raison pour laquelle, on s’en doute, Francis Puyalte ne sera pas invité dans les médias. Peu importe, son livre existe et fera date.Marc LAUDELOUT

Le Bulletin célinien n°337, janvier 2012

• Francis Puyalte. L’Inquisition médiatique (préface de Christian Millau), Éd. Dualpha, coll. « Vérités pour l’Histoire », 2011, 338 p., 38 € frais de port inclus aux Éd. Dualpha, Bte 30, 16 bis rue d’Odessa, 75014 Paris.

1. Saphia Azzedine, Héros anonymes, Éditions Léo Scheer, 2011.

2. Francis Puyalte, « Les confidences de la femme de Céline », Le Figaro, 20 mai 1992 & « Les souvenirs de la femme de Céline », Le Figaro, 30 décembre 1992. Articles repris dans Le Bulletin célinien, n° 123 et n° 127.

3. Philippe Bilger, « Au journalisme inconnu », Justice au singulier. Le blog de Philippe Bilger [http://www.philippebilger.com], 10 décembre 2011. Repris sur le site http://www.marianne2.fr

00:06 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lettres, lettres françaises, littérature, littérature française, céline, journalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 30 janvier 2012

Céline au bout de la nuit - Entretien avec Dominique de Roux – 1966

Céline au bout de la nuit

Entretien avec Dominique de Roux – 1966

Ex: http://lepetitcelinien.blogspot.com/

A lire :

A lire :

Dominique de Roux, La mort de L.-F. Céline, La Table Ronde, 2007.

Jean-Luc Barré, Dominique de Roux : Le provocateur (1935-1977), Fayard, 2005.

Dominique de Roux, Il faut partir : Correspondances inédites (1953-1977), Fayard, 2007.

Philippe Barthelet, Dominique de Roux, Coll. Qui suis-je, Pardès, 2007.

A voir :

Dominique de Roux (1935-1977)

00:00 Publié dans Entretiens, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, dominique de roux, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature, littérature françaises, france, années 60 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 29 janvier 2012

Céline et le thème du Roi Krogold

Céline et le thème du Roi Krogold

par Erika Ostrovsky

Ex: http://lepetitcelinien.blogspot.com/

Céline lui aussi est d'abord, avant tout : rêveur. Au centre de cette nuit qui l'entoure et qui inonde ses oeuvres, au bout de tous les chemins de l'existence qu'il explore si implacablement, se trouve un immense réservoir de poésie et de rêve. Caché, protégé du regard vulgaire ou indifférent par un mur de silence, de défi ou de dureté, Céline préserve un sens profond, une faim inépuisable de ce domaine ancien et lointain qui appartient aux vrais poètes de tous les temps : celui du conte, de la légende, du mythe. Ce domaine est la retraite secrète à l'abri du monde d'ici-bas.

Céline lui aussi est d'abord, avant tout : rêveur. Au centre de cette nuit qui l'entoure et qui inonde ses oeuvres, au bout de tous les chemins de l'existence qu'il explore si implacablement, se trouve un immense réservoir de poésie et de rêve. Caché, protégé du regard vulgaire ou indifférent par un mur de silence, de défi ou de dureté, Céline préserve un sens profond, une faim inépuisable de ce domaine ancien et lointain qui appartient aux vrais poètes de tous les temps : celui du conte, de la légende, du mythe. Ce domaine est la retraite secrète à l'abri du monde d'ici-bas.Si nous voulons regarder de près le thème de Krogold, nous devons nous baser sur les fragments que nous trouvons dans Mort à crédit. Bien que Céline parle à plusieurs reprises de tout un manuscrit perdu, d'un « roman épique (2) », d'une « légende celte (3) », intitulée La Volonté du roi Krogold, nous n'en avons retrouvé aucune trace. Heureusement, la légende, telle qu'elle paraît dans Mort à crédit, est suffisante pour révéler des aspects très intéressants de la vision fondamentale de Céline et nous fournit donc une clef précieuse pour la compréhension de son oeuvre.

La légende elle-même fait irruption assez abruptement dans Mort à crédit, à chaque fois qu'elle apparaît. Le récit ne se fait nullement de manière suivie : il saute, s'arrête, reprend ; ce n'est pas dans l'intrigue que réside son importance. L'histoire elle-même n'a rien d'extraordinaire : elle ressemble superficiellement à maintes oeuvres médiévales qui décrivent une lutte entre deux adversaires, et pourrait presque passer pour un pastiche des romans épiques. Céline, en parlant de Krogold, le classe parmi ses oeuvres lyriques, ironiques (4), indiquant peut-être que son penchant pour l'humour se fait sentir dans la forme donnée à la légende. Cet humour révèle peut-être un souci de dissimuler l'importance fondamentale du thème de Krogold.

Le fragment le plus important est aussi le premier qui paraît dans Mort à crédit. Introduit dans un chapitre qui débute sur un plan terre à terre, il étonne par son ton élevé, son style lyrique, la profondeur de ses jugements. La lutte entre la réalité et la légende, décrite de manière frappante, font de ce chapitre l'un des plus importants du livre.

Celui qui est élu pour écouter la légende est Gustin Sabayot, homme désabusé, fatigué, un peu charlatan, connard, abruti par les circonstances, le métier, la soif, les soumissions les plus funestes. Ferdinand lui demande : Peux-tu encore, en ce moment, te rétablir en poésie ?... faire un petit bond de cœur et de bide au récit d'une épopée, tragique certes, mais noble, étincelante !... Te crois-tu capables ?... (5) Mais Gustin reste assoupi sur son escabeau, passif, indiquant dès le début qu'il sera incapable du bond qu'on réclame de lui : ce qui fait de la légende un récit prononcé dans le vide, mais qui doit être prononcé quand même.

Le récit commence après une courte introduction, en langage parlé, comme une dernière tentative pour atteindre Gustin, pour l'entraîner vers la légende. Puis, il s'élève soudainement, prenant l'allure d'un conte ; la langue devient littéraire, noble ; le rythme ralentit. Nous sommes en pleine légende. La scène est un champ de bataille : Dans l'ombre montent les râles de l'immense agonie d'une armée. Parmi eux, Gwendor le Magnifique expire, mis à mort par le roi Krogold pour l'avoir trahi. A l'aube, la mort paraît devant Gwendor. Suit le dialogue entre Gwendor et la Mort, qui est d'une importance capitale :

« As-tu compris, Gwendor ?

— J'ai compris, ô Mort ! J'ai compris dès le début de cette journée... J'ai senti dans mon coeur, dans mon bras aussi, dans les yeux de mes amis, dans le pas même de mon cheval, un charme triste qui tenait du sommeil... Mon étoile s'éteignait entre tes mains glacées... Tout se mit à fuir ! Ô Mort ! Grands remords ! Ma honte est immense !... Regarde ce pauvre corps !... Une éternité de silence ne peut l'adoucir !...

— Il n'est point de douceur en ce monde, Gwendor ! rien que de légende ! Tous les royaumes finissent dans un rêve !... »

Le chapitre se termine sur la réaction de Gustin : sa méfiance face à la beauté, son refus de « rajeunir », sa défense contre la légende, ses demandes d'explications. Mais il n'est pas facile de mettre le monde de la poésie sur la table de dissection, sous la lumière crue de tous les jours : C'est fragile comme papillon. Pour un rien ça s'éparpille, ça vous salit. Il vaut mieux ne pas

insister, s'éloigner de ceux qui ne peuvent pas comprendre.

Et cependant, quelque chose pousse l'auteur à continuer son récit. Il se tourne vers nous dans le chapitre suivant, sans grand espoir d'être compris et avec un sourire amer, semble-t-il, pour nous décrire le château du roi Krogold : ... Un formidable monstre au cœur de la forêt, masse tapie, écrasante, taillée dans la roche... pétrie de sentines, crédences bourrelées de frises et de redans... d'autres donjons... Du lointain, de la mer là-bas... les cimes de la forêt ondulent et viennent battre jusqu'aux premières murailles...

Et Gustin a, encore une fois, une réaction négative : Gustin il n'en pouvait plus. Il somnolait... Il roupillait même. Je retourne fermer sa boutique.

Dans ces deux pages de Mort à crédit, Céline réussit à nous donner une synthèse de sa vision fondamentale. Nous reconnaissons d'abord l'opposition foncière entre le domaine de la poésie, de la légende ou du mythe, et celui de la vie quotidienne. Le bond qui projette l'homme, au-dessus, en dehors de cette vie, le moment où il se « rétablit en poésie », est le seul qui puisse le sauver d'un avilissement quasi total. Ici, cette conviction fondamentale nous est présentée de façon pessimiste, car Gustin n'est nullement capable de se rétablir en poésie. Dans son métier de médecin (et, en ceci, il est en quelque sorte le double de Ferdinand, comme Robinson l'était pour Bardamu dans le Voyage), il a été inondé par toute la misère du quartier où il exerçait : Eczémateux, albumineux, sucrés, fétides, trembloteurs, vagineuses, inutiles, les « trop », les « pas assez », les constipés, les enfoirés du repentir, tout le bourbier, le monde en transferts d'assassins, était venu refluer sur sa bouille, cascader devant ses binocles depuis trente ans, soir et matin.

C'est Gwendor le Magnifique qui paraît le premier. Le décor est important. C'est sur un énorme lit de mort, sur un champ de bataille que nous le voyons, agonisant, entouré de blessés qui râlent dans l'ombre. Lentement, le silence se fait, étouffant tour à tour cris et râles, de plus en plus faibles, de plus en plus rares... A l'aube, la Mort paraît. Le dialogue de Gwendor avec elle résume sa propre vie, la vie humaine.

La Mort devient la voix de la lucidité, de l'amère réalité. Elle fait contraste avec la douce mélancolie de Gwendor, avec ses idées romanesques et presque naïves, ses efforts pour trouver des solutions à la misère de la vie et de la mort.

Le roi Krogold, qui paraîtra plus tard dans la légende, impose déjà sa présence dans les premières remarques et dans la description de son château. Nous savons qu'il est brutal, qu'il rend sa terrible justice sans pitié. Son château, comme lui, est un formidable monstre, une masse taillée dans la roche, pleine d'oubliettes, une vraie demeure de bourreau. N'avons-nous pas là déjà l'évocation de tous les domaines monstrueux que Céline va décrire dans ses romans ultérieurs, la fondation de ces châteaux cauchemardesques qui vont s'élever dans ses dernières œuvres ? Et les armes royales, le serpent tranché au cou saignant qui proclame Malheur aux traîtres ! ne flotteront-elles pas à la cime de toutes les forteresses bourrées de cachots qui hantent les dernières œuvres de Céline ? Ici, cependant, Krogold et son château symbolisent, sans plus, tout ce qui est opposé à Gwendor : la cruauté, la victoire, l'autorité établie, la vie impitoyable.

Le côté bourreau du roi Krogold ressort plus clairement dans les autres parties de la légende que nous trouvons à divers endroits de Mort à crédit.

Grâce à lui, les forces bestiales, barbares, l'emportent ; la défaite totale, la subjugaison des victimes, de tous ceux qui ont osé s'opposer à son règne, s'accomplit. Et même dans la légende, l'amère vérité s'impose : le monstre n'est pas vaincu par le héros; la justice ne triomphe pas. C'est là le fond de la pensée de Céline qui se révèle. Il revient toujours à la surface dans ses œuvres.

Et la légende elle-même, domaine de l'imagination et du rêve qui s'incarne en Gwendor, n'est-elle pas aussi menacée que lui ? Pour triompher, les forces de la brutalité doivent rejeter ou détruire celles de la poésie. En effet dans Mort à crédit, la légende devient un danger pour son auteur, car on l'accuse d'avoir débauché le petit André par ce moyen, d'être un révolté dangereux qui sème l'indiscipline à travers les rayons de Monsieur Lavelongue. Il doit donc être châtié comme traître à l'ordre établi. Pour ses proches, il devient le maudit qui, c'est évident, finira sur l'échafaud. Il faut l'éloigner comme un pestiféré.

Ferdinand lui-même, ahuri par les conséquences de ses incursions dans le monde défendu de la poésie, devient peureux et commence à se défendre contre les tentations du rêve, de la légende. Mais il y a toujours danger qu'elles reviennent. Nora, au « Meanwell College », le menace par sa féerie, son sortilège, par des ondes, des magies, et il se défend de toutes ses forces. Le monde poétique agit avec puissance. C'est lui qu'incarne Nora à côté de l'érotique : elle émanait toute l'harmonie, tous ses mouvements étaient exquis... C'était un charme, un mirage... Quand elle passait d'une pièce à l'autre, ça faisait comme un vide dans l'âme.

En fait, Nora ressemble à Wanda la Blonbe, évoquée dans la légende du roi Krogold. Le plus grand danger, cependant, se présente quand l'enchantement de Nora est renforcé par celui des légendes, par l'éblouissement d'un livre de contes anciens. Mais celui qui a été châtié pour avoir autrefois dévoilé son dévouement au monde de la poésie, n'en veut plus souffrir ; et Ferdinand rejette celui-ci de manière féroce, brutale : Je me suis cramponné au gazon... J'en voulais plus, moi, merde ! des histoires J'étais vacciné !...

Je m'en rappelais pas moi des légendes ?... Et de ma connerie? A propos ? Non ? Une fois embarqué dans les habitudes où ça vous promène ?... Alors, qu'on me casse plus les couilles ! Cependant, il est impossible de renoncer à ce monde si puissant (6) ; Ferdinand, adulte, n'est nullement guéri de son penchant d'enfant et raconte toujours sa légende à Gustin. Il nous dit à la deuxième page du roman (qui, chronologiquement, en est la dernière) : J'aime mieux raconter des histoires. J'en raconterai de telles qu'ils reviendront exprès, pour me tuer, des quatre coins du monde. Phrase étrangement prophétique : ce sera, en effet, le destin de Céline poète.

Si la légende du roi Krogold raconte la défaite de Gwendor (le Poétique), si le roman lui-même semble décrire les attaques du monde brutal qui menace, ou les marchés dégradants qu'il faut quelquefois conclure, les dénonciations mêmes qui sont parfois nécessaires (7), Mort à crédit dans sa totalité affirme le rêve, la poésie, la légende. Non que Céline partage, avec Marcel Proust, la conviction que le domaine de l'imagination est tout-puissant. Il est vrai que la légende de Krogold, comme celle de Golo, est une projection magique, mais elle ne peut pas transfigurer la réalité. Elle reste opposée à celle-ci, île de rêve ou de poésie — fragile, facilement salie ou détruite. L'image de Krogold ne peut pas, comme celle de Golo, effectuer la métamorphose du bouton de porte de la réalité. C'est plutôt l'image qui est déchirée, anéantie, si le bouton de la porte est brusquement secoué par une main brutale ou indifférente. En dépit de cela, cependant, le côté légendaire, féerique, poétique revient continuellement dans l'oeuvre de Céline, par des moyens obliques, dans des phrases isolées, des apartés presque...

Et la légende du roi Krogold, même si Céline déplore sa disparition, n'est pas vraiment perdue. Elle ne nous donne pas seulement une clef importante pour Mort à crédit, mais elle se réanime de maintes manières dans toute son oeuvre. Ses thèmes ont des racines tellement profondes dans l'esprit de l'auteur qu'elles ne peuvent que se frayer un chemin dans ses écrits. Nous n'avons qu'à regarder les derniers romans pour voir combien les lignes du roi Krogold, esquissées d'abord de manière assez sommaire, se sont élargies et approfondies : le château de Krogold, dont nous ne voyons que la silhouette dans Mort à crédit, se concrétise pour atteindre toutes ses proportions ahurissantes dans l'immense domaine habité de monstres qu'est Kräntzlin, ou le château cauchemardesque de Siegmaringen où les démons sont des familiers. C'est là aussi que nous retrouvons un Krogold d'autant plus terrible qu'il est devenu femme : Nicha qui règne avec ses dogues et règle l'ouverture des portes de l'enfer. Mais l'autre face de la légende se réaffirme aussi. La beauté, la douceur, l'harmonie, la pitié, la poésie essentielle que nous trouvions chez Gwendor, s'étendent sur des êtres divers: des jeunes filles gracieuses qui passent un instant dans une vie(8) ; de vieilles dames fragiles qui habitent le monde de la poésie, chez lesquelles on ressent une « musique de fond », comme Mme Bonnard (9) ; des animaux qui ont une justesse, une beauté, même dans leur agonie (10), les danseuses finalement, qui s'acheminent vers toute la poésie, l'harmonie possible à l'homme, et à leur tête celle qui en est l'incarnation : Lili, Arlette, Lucette.

Erika OSTROVSKY

Céline et le thème du Roi Krogold, Herne, 1972.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : lettres, lettres françaises, littérature, littérature française, france, céline |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 24 janvier 2012

L'insolence des anarchistes de droite

L'insolence des anarchistes de droite

Article de Dominique Venner dans Le Spectacle du Monde de décembre 2011

Ex: http://www.dominiquevenner.fr/

Les anarchistes de droite me semblent la contribution française la plus authentique et la plus talentueuse à une certaine rébellion insolente de l’esprit européen face à la « modernité », autrement dit l’hypocrisie bourgeoise de gauche et de droite. Leur saint patron pourrait être Barbey d’Aurévilly (Les Diaboliques), à moins que ce ne soit Molière (Tartuffe). Caractéristique dominante : en politique, ils n’appartiennent jamais à la droite modérée et honnissent les politiciens défenseurs du portefeuille et de la morale. C’est pourquoi l’on rencontre dans leur cohorte indocile des écrivains que l’on pourrait dire de gauche, comme Marcel Aymé, ou qu’il serait impossible d’étiqueter, comme Jean Anouilh. Ils ont en commun un talent railleur et un goût du panache dont témoignent Antoine Blondin (Monsieur Jadis), Roger Nimier (Le Hussard bleu), Jean Dutourd (Les Taxis de la Marne) ou Jean Cau (Croquis de mémoire). A la façon de Georges Bernanos, ils se sont souvent querellés avec leurs maîtres à penser. On les retrouve encore, hautins, farceurs et féroces, derrière la caméra de Georges Lautner (Les Tontons flingueurs ou Le Professionnel), avec les dialogues de Michel Audiard, qui est à lui seul un archétype.

Deux parmi ces anarchistes de la plume ont dominé en leur temps le roman noir. Sous un régime d’épais conformisme, ils firent de leurs romans sombres ou rigolards les ultimes refuges de la liberté de penser. Ces deux-là ont été dans les années 1980 les pères du nouveau polar français. On les a dit enfants de Mai 68. L’un par la main gauche, l’autre par la main droite. Passant au crible le monde hautement immoral dans lequel il leur fallait vivre, ils ont tiré à vue sur les pantins et parfois même sur leur copains.

À quelques années de distances, tous les deux sont nés un 19 décembre. L’un s’appelait Jean-Patrick Manchette. Il avait commencé comme traducteur de polars américains. Pour l’état civil, l’autre était Alain Fournier, un nom un peu difficile à porter quand on veut faire carrière en littérature. Il choisit donc un pseudonyme qui avait le mérite de la nouveauté : ADG. Ces initiales ne voulaient strictement rien dire, mais elles étaient faciles à mémoriser.

En 1971, sans se connaître, Manchette et son cadet ADG ont publié leur premier roman dans la Série Noire. Ce fut comme une petite révolution. D’emblée, ils venaient de donner un terrible coup de vieux à tout un pan du polar à la française. Fini les truands corses et les durs de Pigalle. Fini le code de l’honneur à la Gabin. Avec eux, le roman noir se projetait dans les tortueux méandres de la nouvelle République. L’un traitait son affaire sur le mode ténébreux, et l’autre dans un registre ironique. Impossible après eux d’écrire comme avant. On dit qu’ils avaient pris des leçons chez Chandler ou Hammett. Mais ils n’avaient surtout pas oublié de lire Céline, Michel Audiard et peut-être aussi Paul Morand. Ecriture sèche, efficace comme une rafale bien expédiée. Plus riche en trouvailles et en calembours chez ADG, plus aride chez Manchette.

Né en 1942, mort en 1996, Jean-Patrick Manchette publia en 1971 L’affaire N’Gustro directement inspirée de l’affaire Ben Barka (opposant marocain enlevé et liquidé en 1965 avec la complicité active du pouvoir et des basses polices). Sa connaissance des milieux gauchistes de sa folle jeunesse accoucha d’un tableau véridique et impitoyable. Féministes freudiennes et nymphos, intellos débiles et militants paumés. Une galerie complète des laissés pour compte de Mai 68, auxquels Manchette ajoutait quelques portraits hilarants de révolutionnaires tropicaux. Le personnage le moins antipathique était le tueur, ancien de l’OAS, qui se foutait complètement des fantasmes de ses complices occasionnels. C’était un cynique plutôt fréquentable, mais il n’était pas de taille face aux grands requins qui tiraient les ficelles. Il fut donc dévoré.

Ce premier roman, comme tous ceux qu’écrivit Manchette, était d’un pessimisme intégral. Il y démontait la mécanique du monde réel. Derrière le décor, régnaient les trois divinités de l’époque : le fric, le sexe et le pouvoir.

Au fil de ses propres polars, ADG montra qu’il était lui aussi un auteur au parfum, appréciant les allusions historiques musclées. Tour cela dans un style bien identifiable, charpenté de calembours, écrivant « ouisquie » comme Jacques Perret, l’auteur inoubliable et provisoirement oublié de Bande à part.

Si l’on ne devait lire d’ADG qu’un seul roman, ce serait Pour venger Pépère (Gallimard), un petit chef d’œuvre. Sous une forme ramassée, la palette adégienne y est la plus gouailleuse. Perfection en tout, scénario rond comme un œuf, ironie décapante, brin de poésie légère, irrespect pour les « valeurs » avariées d’une époque corrompue.

L’histoire est celle d’une magnifique vengeance qui a pour cadre la Touraine, patrie de l’auteur. On y voit Maître Pascal Delcroix, jeune avocat costaud et désargenté, se lancer dans une petite guerre téméraire contre les puissants barons de la politique locale. Hormis sa belle inconscience, il a pour soutien un copain nommé « Machin », journaliste droitier d’origine russe, passablement porté sur la bouteille, et « droit comme un tirebouchon ». On s’initie au passage à la dégustation de quelques crus de Touraine, le petit blanc clair et odorant de Montlouis, ou le Turquant coulant comme velours.

Point de départ, l’assassinat fortuit du grand-père de l’avocat. Un grand-père comme on voudrait tous en avoir, ouvrier retraité et communiste à la mode de 1870, aimant le son du clairon et plus encore la pêche au gardon. Fier et pas dégonflé avec çà, ce qui lui vaut d’être tué par des malfrats dûment protégés. A partir de là on entre dans le vif du sujet, c’est à dire dans le ventre puant d’un système faisandé, face nocturne d’un pays jadis noble et galant, dont une certaine Sophie, blonde et gracieuse jeunes fille, semble comme le dernier jardin ensoleillé. Rien de lugubre pourtant, contrairement aux romans de Manchettes. Au contraire, grâce à une insolence joyeuse et un mépris libérateur.

Au lendemain de sa mort (1er novembre 2004), ADG fit un retour inattendu avec J’ai déjà donné, roman salué par toute la critique. Héritier de quelques siècles de gouaille gauloise, insolente et frondeuse, ADG avait planté entre-temps dans la panse d’une république peu recommandable les banderilles les plus jubilatoires de l’anarchisme de droite.

Notes

Alain Fournier, dit ADG (1947-2004), un pseudonyme choisi à partir des initiales de son tout premier nom de plume, Alain Dreux-Gallou. Une oeuvre jubilatoire plein d ‘irrespect contre les “valeurs” avariées d’une époque corrompue.

00:10 Publié dans Littérature, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : dominique venner, nouvelle droite, anarchisme, anarchisme de droite, droite, philosophie, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature, littérature française |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 20 janvier 2012

Pourquoi relire Koestler?

Pourquoi relire Koestler?

Entretien avec Robert Steuckers à l’occasion de ses dernières conférences sur la vie et l’oeuvre d’Arthur Koestler

Propos recueillis par Denis Ilmas

DI: Monsieur Steuckers, vous voilà embarqué dans une tournée de conférences sur la vie et l’oeuvre d’Arthur Koestler, un auteur quasi oublié aujourd’hui, peu (re)lu et dont les livres ne sont plus tous réédités. Pourquoi insistez-vous sur cet auteur, quand commence la seconde décennie du 21ème siècle?

RS: D’abord parce que j’arrive à l’âge des rétrospectives. Non pas pour me faire plaisir, même si cela ne me déplait pas. Mais parce que de nombreuses personnes, plus jeunes que moi, me posent des questions sur mon itinéraire pour le replacer dans l’histoire générale des mouvements non conformistes de la seconde moitié du 20ème siècle et, à mon corps défendant, dans l’histoire, plus limitée dans le temps et l’espace, de la “nouvelle droite”. Commençons par l’aspect rétrospectif: j’ai toujours aimé me souvenir, un peu à la façon de Chateaubriand, de ce moment précis de ma tendre adolescence, quelques jours après que l’on m’ait exhorté à lire des livres “plus sérieux” que les ouvrages généralement destinés à la jeunesse, comme Ivanhoe de Walter Scott ou L’ile au trésor de Stevenson, Les trois mousquetaires de Dumas, Jules Vernes, ou à l’enfance, comme la Comtesse de Ségur (dont mon préféré était et reste Un bon petit diable) et la série du “Club des Cinq” d’Enid Blyton (que je dévorais à l’école primaire, fasciné que j’étais par les innombrables aventures passées derrière des portes dérobées ou des murs lambrisés à panneaux amovibles, dans de mystérieux souterrains ou autres passages secrets). Rien que cette liste de livres lus par un gamin, il y a quarante, quarante-cinq ans, évoque une époque révolue... Mais revenons à ce “moment” précis qui est un petit délice de mes reminiscences: j’avais accepté l’exhortation des adultes et, de toutes les façons, la littérature enfantine et celle de la pré-adolescence ne me satisfaisaient plus.

Koestler m’accompagne maintenant depuis plus de quarante ans

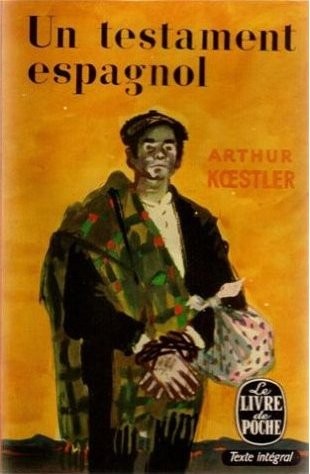

Mais que faire? Sur le chemin de l’école, tout à la fin de la Chaussée de Charleroi, à trente mètres du grand carrefour animé de “Ma Campagne”, il y avait un marchand de journaux qui avait eu la bonne idée de joindre une belle annexe à son modeste commerce et de créer une “centrale du Livre de Poche”. Il y avait, en face et à droite de son comptoir, un mur, qui me paraissait alors incroyablement haut, où s’alignaient tous les volumes de la collection. Je ne savais pas quoi choisir. J’ai demandé un catalogue et, muni de celui-ci, je suis allé trouver le Frère Marcel (Aelbrechts), vieux professeur de français toujours engoncé dans son cache-poussière brunâtre mais cravaté de noir (car un professeur devait toujours porter la cravate à l’époque...), pour qu’il me pointe une dizaine de livres dans le catalogue. Il s’est exécuté avec complaisance, avec ses habituels claquements humides de langue et de maxillaires, par lesquels il ponctuait ses conseils toujours un peu désabusés: l’homme n’avait apparemment plus grande confiance en l’humanité... Dans la liste, il y avait Un testament espagnol d’Arthur Koestler. Je l’ai lu, un peu plus tard, vers l’âge de quinze ans. Et cet ouvrage m’a laissé une très forte impression. Koestler m’accompagne donc depuis plus de quarante ans maintenant.

Le Testament espagnol de Koestler est un chef-d’oeuvre: la déréliction de l’homme, qui attend une exécution promise, les joies de lire dans cette geôle, espace exigu entre deux mondes (celui de la vie, qu’on va quitter, et celui, de l’“après”, inconnu et appréhendé), la fatalité de la mort dans un environnement ibérique, acceptée par les autres détenus, dont “le Poitrinaire”... A quinze ans, une littérature aussi forte laisse des traces. Pendant deux bonnes années, Koestler, pour moi, n’a été que ce prisonnier anglo-judéo-hongrois, pris dans la tourmente de la Guerre Civile espagnole, cet homme d’une gauche apparemment militante, dont on ne discernait plus tellement les contours quand s’évanouissait les vanités face à une mort qu’il pouvait croire imminente.

Le Testament espagnol de Koestler est un chef-d’oeuvre: la déréliction de l’homme, qui attend une exécution promise, les joies de lire dans cette geôle, espace exigu entre deux mondes (celui de la vie, qu’on va quitter, et celui, de l’“après”, inconnu et appréhendé), la fatalité de la mort dans un environnement ibérique, acceptée par les autres détenus, dont “le Poitrinaire”... A quinze ans, une littérature aussi forte laisse des traces. Pendant deux bonnes années, Koestler, pour moi, n’a été que ce prisonnier anglo-judéo-hongrois, pris dans la tourmente de la Guerre Civile espagnole, cet homme d’une gauche apparemment militante, dont on ne discernait plus tellement les contours quand s’évanouissait les vanités face à une mort qu’il pouvait croire imminente.

En 1973, nous nous retrouvâmes en voyage scolaire, sous le plomb du soleil d’août en Grèce. Marcel nous escortait; il avait troqué son éternel cache-poussière contre un costume léger de coton clair; il suivait la troupe de sa démarche molle et avec la mine toujours sceptique, cette fois avec un galurin, type bobo, rivé sur son crâne dégarni. Un jour, alors que nous marchions de l’auberge universitaire, située sur un large boulevard athénien, vers une station de métro pour nous amener à l’Acropole ou à Egine, les “non-conformistes” de la bande —Frédéric Beerens, le futur gynécologue Leyssens, Yves Debay, futur directeur des revues militaires Raids et L’Assaut et votre serviteur— tinrent un conciliabule en dévalant allègrement une rue en pente: outre les livres, où nous trouvions en abondance notre miel, quelle lecture régulière adopter pour consolider notre vision dissidente, qui, bien sûr, n’épousait pas les formes vulgaires et permissives de dissidence en cette ère qui suivait immédiatement Mai 68? Nous connaissions tous le mensuel Europe-Magazine, alors dirigé par Emile Lecerf. La littérature belge de langue française doit quelques belles oeuvres à Lecerf: inconstestablement, son essai sur Montherlant, rédigé dans sa plus tendre jeunesse, mérite le détour et montre quelle a été la réception de l’auteur des Olympiques, surtout chez les jeunes gens, jusqu’aux années de guerre. Plus tard, quand le malheur l’a frappé et que son fils lui a été enlevé par la Camarde, il nous a laissé un témoignage poignant avec Pour un fils mort à vingt ans. Lié d’amitié à Louis Pauwels, Lecerf était devenu le premier correspondant belge de la revue Nouvelle école. Beerens avait repéré une publicité pour cette revue d’Alain de Benoist qui n’avait alors que trente ans et cherchait à promouvoir sa création. En dépit de l’oeuvre littéraire passée d’Emile Lecerf, que nous ne connaissions pas à l’époque, le style journalistique du directeur d’Europe-Magazine nous déplaisait profondément: nous lui trouvions des accents populaciers et lui reprochions trop d’allusions graveleuses. Nous avions soif d’autre chose et peut-être que cette revue Nouvelle école, aux thèmes plus allèchants, allait-elle nous satisfaire?

Koestler et la “nouvelle droite”: le lien? La critique du réductionnisme!

Le conciliabule ambulant d’Athènes a donc décidé de mon sort: depuis cette journée torride d’août 1973 à Athènes, je suis mu par un tropisme qui me tourne immanquablement vers Nouvelle école, même vingt après avoir rompu avec son fondateur. Dès notre retour à Bruxelles, nous nous sommes mis en chasse pour récupérer autant de numéros possible, nous abonner... Beerens et moi, après notre quête qui nous avait menés aux bureaux du magazine, rue Deckens à Etterbeek, nous nous sommes retrouvés un soir à une séance du NEM-Club de Lecerf, structure destinée à servir de point de ralliement pour les lecteurs du mensuel: nouvelle déception... Mais, dans Nouvelle école puis dans les premiers numéros d’Eléments, reçus en novembre 1973, un thème se profilait: celui d’une critique serrée du “réductionnisme”. C’est là que Koestler m’est réapparu. Il n’avait pas été que cet homme de gauche romantique, parti en Espagne pendant la guerre civile pour soutenir le camp anti-franquiste, il avait aussi été un précurseur de la critique des idéologies dominantes. Il leur reprochait de “réduire” les mille et un possibles de l’homme à l’économie (et à la politique) avec le marxisme ou au sexe (hyper-problématisé) avec le freudisme, après avoir été un militant communiste exemplaire et un vulgarisateur des thèses de Sigmund Freud.

A mes débuts dans ce qui allait, cinq ans plus tard, devenir la mouvance “néo-droitiste”, le thème majeur était en quelque sorte la résistance aux diverses facettes du réductionnisme. Nouvelle école et Eléments évoquaient cette déviance de la pensée qui entraînait l’humanité occidentale vers l’assèchement et l’impuissance, comme d’ailleurs —mais nous ne le saurions que plus tard— les groupes Planète de Louis Pauwels l’avaient aussi évoquée, notamment avec l’appui d’un compatriote, toujours méconnu aujourd’hui ou seulement décrié sur le ton de l’hystérie comme “politiquement incorrect”, Raymond de Becker. En entrant directement en contact avec les représentants à Bruxelles de Nouvelle école et du “Groupement de Recherches et d’Etudes sur la Civilisation Européenne” (GRECE) —soit Claude Vanderperren à Auderghem en juin 1974, qui était le nouveau correspondant de Nouvelle école, Dulière à Forest en juillet 1974 qui distribuait les brochures du GRECE, puis Georges Hupin, qui en animait l’antenne à Uccle en septembre 1974— nous nous sommes aperçus effectivement que la critique du réductionnisme était à l’ordre du jour: thème majeur de l’Université d’été du GRECE, dont revenait Georges Hupin; thème tout aussi essentiel de deux “Congrès Internationaux pour la Défense de la Culture”, tenus, le premier, à Turin en janvier 1973, le deuxième à Nice (sous les auspices de Jacques Médecin), en septembre 1974. Ces Congrès avaient été conçus et initiés, puis abandonnés, par Arthur Koestler et Ignazio Silone, dès les débuts de la Guerre Froide, pour faire pièce aux associations dites de “défense des droits de l’homme”, que Koestler, Orwell et Silone percevaient comme noyautées par les communistes. Une seconde équipe les avaient réanimés pour faire face à l’offensive freudo-marxiste de l’ère 68. C’était essentiellement le professeur Pierre Debray-Ritzen qui, au cours de ces deux congrès de 1973 et 1974, dénoncera le réductionnisme freudien. Alain de Benoist, Louis Rougier, Jean Mabire et Dominique Venner y ont participé.

Le colloque bruxellois sur le réductionnisme

Dans la foulée de ce réveil d’une pensée plurielle, dégagée des modes du temps, Georges Hupin, après avoir convaincu les étudiants libéraux de l’ULB, monte en avril 1975 un colloque sur le réductionnisme dans les locaux mêmes de l’Université de Bruxelles. Le thème du réductionnisme séduisait tout particulièrement Jean Omer Piron, biologiste et rédacteur-en-chef, à l’époque, de la revue des loges belges, La Pensée et les Hommes. Dans les colonnes de cette vénérable revue, habituée au plus plat des conformismes laïcards (auquel elle est retourné), Piron avait réussi à placer des articles rénovateurs dans l’esprit du “Congrès pour la Défense de la Culture” et du premier GRECE inspiré par les thèses anti-chrétiennes de Louis Rougier, par ailleurs adepte de l’empirisme logique, veine philosophique en vogue dans le monde anglo-saxon. Le colloque, cornaqué par Hupin, s’est tenu à l’ULB, avec la participation de Jean-Claude Valla (représentant le GRECE), de Piet Tommissen (qui avait participé au Congrès de Nice, avec ses amis Armin Mohler et Ernst Topitsch), de Jean Omer Piron et du Sénateur libéral d’origine grecque Basile Risopoulos. Des étudiants et des militants communistes ou assimilés avaient saboté le système d’alarme, déclenchant un affreux hululement de sirène, couvrant la voix des conférenciers. Alors que j’étais tout malingre à dix-neuf ans, on m’envoie, avec le regretté Alain Derriks (que je ne connaissais pas encore personnellement) et un certain de W., ancien de mon école, pour monter la garde au premier étage et empêcher toute infiltration des furieux. L’ami de W. met immédiatement en place la lance à incendie, bloquant le passage, tandis que je reçois un gros extincteur pour arroser de poudre d’éventuels contrevenants et que Derriks a la présence d’esprit de boucher les systèmes d’alarme à l’aide de papier hygiénique, réduisant le hululement de la sirène à un bourdonnement sourd, pareil à celui d’une paisible ruche au travail. Les rouges tentent alors un assaut directement à l’entrée de l’auditorium: ils sont tenus en échec par deux officiers de l’armée belge, le Commandant M., tankiste du 1er Lancier, et le Commandant M., des chasseurs ardennais, flanqués d’un grand double-mètre de Polonais, qui venait de quitter la Légion Etrangère et qui accompagnait Jean-Claude Valla. Hupin, de la réserve des commandos de l’air, vient vite à la rescousse. Le Commandant des chasseurs ardennais, rigolard et impavide, repoussait tantôt d’un coup d’épaule, tantôt d’un coup de bide, deux politrouks particulièrement excités et sanglés dans de vieilles vestes de cuir. Pire: allumant soudain un gros cigare hollandais, notre bon Ardennais en avalait la fumée et la recrachait aussitôt dans le visage du politrouk en cuir noir qui scandait “Ecrasons dans l’oeuf la peste brune qui s’est réveillée”. Ce slogan vociféré de belle voix se transformait aussitôt en une toux rauque, sous le souffle âcre et nicotiné de notre cher Chasseur. Mais ce ne sont pas ces vaillants militaires qui emportèrent la victoire! Voilà que surgit, furieuse comme un taureau ibérique excité par la muletta, la concierge de l’université, dont le sabotage du système d’alarme avait réveillé le mari malade. Saisissant sa pantoufle rouge à pompon de nylon, la brave femme, pas impressionnée pour un sou, se jette sur le politrouk à moitié étouffé par les effets fumigènes du cigare du Commandant M., et le roue de coups de savate, en hurlant, “Fous le camp, saligaud, t’as réveillé mon mari, va faire le zot ailleurs, bon à rien, smeirlap, rotzak, etc.”. Les deux meneurs, penauds, ordonnent la retraite. L’entrée de l’auditorium est dégagée: les congressistes peuvent sortir sans devoir distribuer des horions ou risquer d’être maxaudés. Essoufflée, la concierge s’effondre sur une chaise, renfile son héroïque pantoufle et Hupin vient la féliciter en la gratifiant d’un magnifique baise-main dans le plus pur style viennois. Elle était rose de confusion.

Jean Omer Piron et “Le cheval dans la locomotive”

Voilà comment j’ai participé à une initiative, inspirée des “Congrès pour la Défense de la Culture”, dont la paternité initiale revient à Arthur Koestler (et à Ignazio Silone). Elle avait aussi pour thème un souci cardinal de la pensée post-politique de Koestler: le réductionnisme. La prolixité du vivant étant l’objet d’étude des biologistes, Jean Omer Piron se posait comme un “libre-penseur”, dans la tradition de l’ULB, c’est-à-dire comme un libre-penseur hostile à tous les dogmes qui freinent l’élan de la connaissance et empêchent justement d’aborder cette prolixité luxuriante du réel et de la vie. Et, de fait, les réductionnismes sont de tels freins: il convient de les combattre même s’ils ont fait illusion, s’ils ont aveuglé les esprits et se sont emparé de l’Université bruxelloise, où l’on est supposé les affronter et les chasser de l’horizon du savoir. Piron inscrivait son combat dans les traces de Koestler: le Koestler des “Congrès” et surtout le Koestler du Cheval dans la locomotive (The Ghost in the Machine), même si, aujourd’hui, les biologistes trouveront sans doute pas mal d’insuffisances scientifiques dans ce livre qui fit beaucoup de bruit à l’époque, en appelant les sciences biologiques à la rescousse contre les nouveaux obscurantismes, soit disant “progressistes”. Koestler fustigeait le réductionnisme et le “ratomorphisme” (l’art de percevoir l’homme comme un rat de laboratoire). Ce recours à la biologie, ou aux sciences médicales, était considéré comme un scandale à l’époque: le charnel risquait de souiller les belles images d’Epinal, véhiculées par les “nuisances idéologiques” (Raymond Ruyer). Les temps ont certes changé. La donne n’est plus la même aujourd’hui. Mais l’obscurantisme est toujours là, sous d’autres oripeaux. Pour la petite histoire, une ou deux semaines après le colloque chahuté mais dûment tenu sur le réductionnisme, les étudiants de l’ULB, dont Beerens et Derriks, ainsi que leurs homologues libéraux, ont vu débouler dans les salles de cours une brochette de “vigilants”, appelant à la vindicte publique contre Piron, campé comme “fasciste notoire”. Beerens, au fond de la salle, rigolait, surtout quand la plupart des étudiants lançaient de vibrants “vos gueules!” ou des “cassez-vous!” aux copains des politrouks dûment défaits par l’arme secrète (la pantoufle à pompon de nylon) de la concierge, mercenaire à son corps défendant d’une peste brune, dont elle ignorait tout mais qui avait été brusquement réveillée, parait-il, par le “fasciste notoire”, disciple de l’ex-communiste pur jus Koestler et rédacteur-en-chef de la bien laïcarde et bien para-maçonnique La Pensée et les Hommes. L’anti-fascisme professionnel sans profession bien définie montrait déjà qu’il ne relevait pas de la politique mais de la psychiatrie.

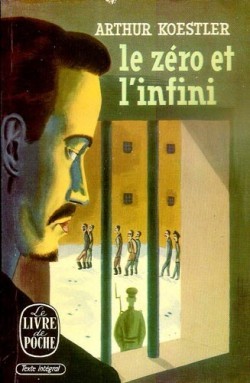

Ma lecture du “Zéro et l’Infini”

Ce n’est pas seulement par l’effet tonifiant du blanc-seing de Piron, dans le microcosme néo-droitiste bruxellois en gestation à l’époque, que Koestler revenait au premier plan de mes préoccupations. En première année de philologie germanique aux Facultés Universitaires Saint-Louis, il me fallait lire, dès le second trimestre, des romans anglais. Mon programme: Orwell, Huxley, Koestler et D. H. Lawrence. L’un des romans sélectionnés devait être présenté oralement: le sort a voulu que, pour moi, ce fut Darkness at Noon (Le zéro et l’infini), récit d’un procès politique dans le style des grandes purges staliniennes des années 30. Le roman, mettant en scène le “dissident” Roubachov face à ses inquisiteurs, est bien davantage qu’une simple dénonciation du stalinisme par un adepte de la dissidence boukharinienne, zinovievienne ou trotskiste. Toute personne qui entre en politique, entre obligatoirement au service d’un appareil, perclus de rigidités, même si ce n’est guère apparent au départ, pour le croyant, pour le militant, comme l’avoue d’ailleurs Koestler après avoir viré sa cuti. A parti d’un certain moment, le croyant se trouvera en porte-à-faux, tout à la fois face à la politique officielle du parti, face aux promesses faites aux militants de base mais non tenables, face à une réalité, sur laquelle le parti a projeté ses dogmes ou ses idées, mais qui n’en a cure. Le croyant connaîtra alors un profond malaise, il reculera et hésitera, devant les nouveaux ordres donnés, ou voudra mettre la charrue avant les boeufs en basculant dans le zèle révolutionnaire. Il sera soit exclu ou marginalisé, comme aujourd’hui dans les partis dits “démocratiques” ainsi que chez leurs challengeurs (car c’est kif-kif-bourricot!). Dans un parti révolutionnaire comme le parti bolchevique en Russie, la lenteur d’adaptation aux nouvelles directives de la centrale, la fidélité à de vieilles amitiés ou de vieilles traditions de l’époque héroïque de la révolution d’Octobre 1917 ou de la clandestinité pré-révolutionnaire, condamne le “lent” ou le nostalgique à être broyé par une machine en marche qui ne peut ni ralentir ni cesser d’aller de l’avant. La logique des procès communistes voulait que les accusés reconnaissent que leur lenteur et leur nostalgie entravaient le déploiement de la révolution dans le monde, mettait le socialisme construit dans un seul pays (l’URSS) en danger donc, ipso facto, que ces “vertus” de vieux révolutionnaires étaient forcément des “crimes” risquant de ruiner les acquis réellement existants des oeuvres du parti. En conséquence, ces “vertus” relevaient de la complicité avec les ennemis extérieurs de l’Union Soviétique (ou, lors des procès de Prague, de la nouvelle Tchécoslovaquie rouge). Lenteur et nostalgie étaient donc objectivement parlant des vices contre-révolutionnaires. Koestler a vécu de près, au sein des cellules du Komintern, ce type de situation. Pour lui, le pire a été l’entrée en dissidence, à son corps défendant, de Willi Münzenberg, communiste allemand chargé par le Komintern d’organiser depuis son exil parisien une résistance planétaire contre le fascisme et le nazisme. Pour y parvenir, Münzenberg avait reçu d’abord l’ordre de créer des “fronts populaires”, avec les socialistes et les sociaux-démocrates, comme en Espagne et en France. Mais la centrale moscovite change d’avis et pose trotskistes et socialistes comme des ennemis sournois de la révolution: Münzenberg entre en disgrâce, parce qu’il ne veut pas briser l’appareil qu’il a patiemment construit à Paris et tout recommencer à zéro; il refuse d’aller s’expliquer à Moscou, de crainte de subir le sort de son compatriote communiste allemand Neumann, épuré en Union Soviétique (sa veuve, Margarete Buber-Neumann, rejoindra Koestler dans son combat anti-communiste d’après guerre). Münzenberg a refusé d’obéir, de s’aligner sans pour autant passer au service de ses ennemis nationaux-socialistes. Dans le roman Darkness at Noon/Le zéro et l’infini, Roubachov n’est ni un désobéissant ni un traître: il proteste de sa fidélité à l’idéal révolutionnaire. Mais suite au travail de sape des inquisiteurs, il finit par admettre que ses positions, qu’il croit être de fidélité, sont une entorse à la bonne marche de la révolution mondiale en cours, qu’il est un complice objectif des ennemis de l’intérieur et de l’extérieur et que son élimination sauvera peut-être de l’échec final la révolution, à laquelle il a consacré toute sa vie et tous ses efforts. (Sur l’itinéraire de Willi Münzenberg, on se rapportera utilement aux pages que lui consacre François Furet dans Le passé d’une illusion – Essai sur l’idée communiste au XX° siècle, Laffont/Calmann-Lévy, 1995).

Ce n’est pas seulement par l’effet tonifiant du blanc-seing de Piron, dans le microcosme néo-droitiste bruxellois en gestation à l’époque, que Koestler revenait au premier plan de mes préoccupations. En première année de philologie germanique aux Facultés Universitaires Saint-Louis, il me fallait lire, dès le second trimestre, des romans anglais. Mon programme: Orwell, Huxley, Koestler et D. H. Lawrence. L’un des romans sélectionnés devait être présenté oralement: le sort a voulu que, pour moi, ce fut Darkness at Noon (Le zéro et l’infini), récit d’un procès politique dans le style des grandes purges staliniennes des années 30. Le roman, mettant en scène le “dissident” Roubachov face à ses inquisiteurs, est bien davantage qu’une simple dénonciation du stalinisme par un adepte de la dissidence boukharinienne, zinovievienne ou trotskiste. Toute personne qui entre en politique, entre obligatoirement au service d’un appareil, perclus de rigidités, même si ce n’est guère apparent au départ, pour le croyant, pour le militant, comme l’avoue d’ailleurs Koestler après avoir viré sa cuti. A parti d’un certain moment, le croyant se trouvera en porte-à-faux, tout à la fois face à la politique officielle du parti, face aux promesses faites aux militants de base mais non tenables, face à une réalité, sur laquelle le parti a projeté ses dogmes ou ses idées, mais qui n’en a cure. Le croyant connaîtra alors un profond malaise, il reculera et hésitera, devant les nouveaux ordres donnés, ou voudra mettre la charrue avant les boeufs en basculant dans le zèle révolutionnaire. Il sera soit exclu ou marginalisé, comme aujourd’hui dans les partis dits “démocratiques” ainsi que chez leurs challengeurs (car c’est kif-kif-bourricot!). Dans un parti révolutionnaire comme le parti bolchevique en Russie, la lenteur d’adaptation aux nouvelles directives de la centrale, la fidélité à de vieilles amitiés ou de vieilles traditions de l’époque héroïque de la révolution d’Octobre 1917 ou de la clandestinité pré-révolutionnaire, condamne le “lent” ou le nostalgique à être broyé par une machine en marche qui ne peut ni ralentir ni cesser d’aller de l’avant. La logique des procès communistes voulait que les accusés reconnaissent que leur lenteur et leur nostalgie entravaient le déploiement de la révolution dans le monde, mettait le socialisme construit dans un seul pays (l’URSS) en danger donc, ipso facto, que ces “vertus” de vieux révolutionnaires étaient forcément des “crimes” risquant de ruiner les acquis réellement existants des oeuvres du parti. En conséquence, ces “vertus” relevaient de la complicité avec les ennemis extérieurs de l’Union Soviétique (ou, lors des procès de Prague, de la nouvelle Tchécoslovaquie rouge). Lenteur et nostalgie étaient donc objectivement parlant des vices contre-révolutionnaires. Koestler a vécu de près, au sein des cellules du Komintern, ce type de situation. Pour lui, le pire a été l’entrée en dissidence, à son corps défendant, de Willi Münzenberg, communiste allemand chargé par le Komintern d’organiser depuis son exil parisien une résistance planétaire contre le fascisme et le nazisme. Pour y parvenir, Münzenberg avait reçu d’abord l’ordre de créer des “fronts populaires”, avec les socialistes et les sociaux-démocrates, comme en Espagne et en France. Mais la centrale moscovite change d’avis et pose trotskistes et socialistes comme des ennemis sournois de la révolution: Münzenberg entre en disgrâce, parce qu’il ne veut pas briser l’appareil qu’il a patiemment construit à Paris et tout recommencer à zéro; il refuse d’aller s’expliquer à Moscou, de crainte de subir le sort de son compatriote communiste allemand Neumann, épuré en Union Soviétique (sa veuve, Margarete Buber-Neumann, rejoindra Koestler dans son combat anti-communiste d’après guerre). Münzenberg a refusé d’obéir, de s’aligner sans pour autant passer au service de ses ennemis nationaux-socialistes. Dans le roman Darkness at Noon/Le zéro et l’infini, Roubachov n’est ni un désobéissant ni un traître: il proteste de sa fidélité à l’idéal révolutionnaire. Mais suite au travail de sape des inquisiteurs, il finit par admettre que ses positions, qu’il croit être de fidélité, sont une entorse à la bonne marche de la révolution mondiale en cours, qu’il est un complice objectif des ennemis de l’intérieur et de l’extérieur et que son élimination sauvera peut-être de l’échec final la révolution, à laquelle il a consacré toute sa vie et tous ses efforts. (Sur l’itinéraire de Willi Münzenberg, on se rapportera utilement aux pages que lui consacre François Furet dans Le passé d’une illusion – Essai sur l’idée communiste au XX° siècle, Laffont/Calmann-Lévy, 1995).

L’anthropologie communiste: une image incomplète de l’homme

Koestler s’insurge contre ce mécanisme qui livre la liberté de l’homme, celle de s’engager politiquement et celle de se rebeller contre des conditions d’existence inacceptables, à l’arbitraire des opportunités passagères (ou qu’il croit passagères). L’homme réel, complet et non réduit, n’est pas le pantin mutilé et muet que devient le révolutionnaire établi, qui exécute benoîtement les directives changeantes de la centrale ou qui confesse humblement ses fautes s’il est, d’une façon ou d’une autre, de manière parfaitement anodine ou bien consciente, en porte-à-faux face à de nouveaux ukases, qui, eux, sont en contradiction avec le plan premier ou le style initial de la révolution en place et en marche. Koestler finira par sortir de toutes les cangues idéologiques ou politiques. Il mettra les errements du communisme sur le compte de son anthropologie implicite, reposant sur une image incomplète de l’homme, réduit à un pion économique. Dans la première phase de son histoire, la “nouvelle droite” en gestation avait voulu, avec Louis Pauwels, porte-voix de l’anthropologie alternative des groupes Planète, restaurer une vision non réductionniste de l’homme.

Ma présentation avait déplu à ce professeur de littérature anglaise des Facultés Saint-Louis, un certain Engelborghs aujourd’hui décédé, tué au volant d’un cabriolet sans doute trop fougueux et mal protégé en ses superstructures. Je n’ai jamais su avec précision ce qui lui déplaisait chez Koestler (et chez Orwell), sauf peut-être qu’il n’aimait pas ce que l’on a nommé par la suite les “political novels” ou la veine dite “dystopique”: toutefois, il ne me semblait pas être l’un de ces hallucinés qui tiennent à leurs visions utopiques comme à toutes leurs autres illusions. Pourtant, je persiste et je signe, jusqu’à mon grand âge: Koestler doit être lu et relu, surtout son Testament espagnol et son Zéro et l’Infini. Après les remarques dénigrantes et infondées d’Engelborghs, je vais abandonner un peu Koestler, sauf peut-être pour son livre sur la peine de mort, écrit avec Albert Camus dans les années 50 en réaction à la pendaison, en Angleterre, de deux condamnés ne disposant apparemment pas de toutes leurs facultés mentales, et pour des crimes auxquels on aurait pu facilement trouver des circonstances atténuantes. Force est toutefois de constater que, dans ce livre-culte des opposants à la peine de mort, on lira que les régimes plus ou moins autocratiques, ceux de l’Obrigkeitsstaat centre-européen, ont bien moins eu recours à la potence ou à la guillotine que les “vertuistes démocraties” occidentales, la France et l’Angleterre. Le paternalisme conservateur induit moins de citoyens au crime, ou se montre plus clément en cas de faute, que le libéralisme, où chacun doit se débrouiller pour ne pas tomber dans la misère noire et se voit condamné sans pitié en cas de faux pas et d’arrestation. Le livre de Koestler et Camus sur la peine de mort réfute, en filigrane, la prétention à la vertu qu’affichent si haut et si fort les “démocraties” occidentales. Ce sont elles, comme dirait Foucault, qui surveillent et punissent le plus.

Dans les rangs du cercle de la première “nouvelle droite” bruxelloise, la critique du réductionnisme et la volonté de rétablir une anthropologie plus réaliste et dégagée des lubies idéologiques du 19ème siècle quittera l’orbite de Koestler et de son Cheval dans la locomotive, pour se plonger dans l’oeuvre du Prix Nobel Konrad Lorenz, notamment son ouvrage de vulgarisation, intitulé Les huit péchés capitaux de notre civilisation (Die acht Todsünde der zivilisierten Menschheit), où le biologiste annonce, pour l’humanité moderne, un risque réel de “mort tiède”, si les régimes politiques en place ne tiennent pas compte des véritables ressorts naturels de l’être humain. Nouvelle école ira d’ailleurs interviewer longuement Lorenz dans son magnifique repère autrichien. Plus tard, en dehors des cercles “néo-droitistes” en voie de constitution, Alexandre Soljénitsyne éclipsera Koestler, dès la seconde moitié des années 70. Avec le dissident russe, l’anti-communisme cesse d’être un tabou dans les débats politiques. Je retrouverai Koestler, en même temps qu’Orwell et Soljénitsyne, à la fin de la première décennie du 21ème siècle pour servir, à titre de conférencier, les bonnes oeuvres de mon ami genevois, Maitre Pascal Junod, féru de littérature et grand lecteur devant l’éternel.

DI: Justement, je reviens à ma question, quel regard doit-on jeter sur la trajectoire d’Arthur Koestler aujourd’hui?

RS: Arthur Koestler est effectivement une “trajectoire”, une flèche qui traverse les périodes les plus effervescentes du 20ème siècle: il le dit lui-même car le titre du premier volume de son autobiographie s’intitule, en anglais, Arrow in the Blue (en français: La corde raide). Enfant interessé aux sciences physiques, le très jeune Koestler s’imaginait suivre la trajectoire d’une flèche traversant l’azur pour le mener vers un monde idéal. Mais dans la trajectoire qu’il a effectivement suivie, si on l’examine avec toute l’attention voulue, rien n’est simple. Koestler nait à Budapest sous la double monarchie austro-hongroise, dans une ambiance impériale et bon enfant, dans un monde gai, tourbillonnant allègrement au son des valses de Strauss. Il suivra, à 9 ans, avec son père, le défilé des troupes magyars partant vers le front de Serbie en 1914, acclamant les soldats du contingent, sûrs de revenir vite après une guerre courte, fraîche et joyeuse. Mais ce monde va s’effondrer en 1918: le très jeune Koestler penche du côté de la dictature rouge de Bela Kun, parce que le gouvernement libéral lui a donné le pouvoir pour qu’il éveille le sentiment national des prolétaires bolchévisants et appelle ainsi les Hongrois du menu peuple à chasser les troupes roumaines envoyées par la France pour fragmenter définitivement la masse territoriale de l’Empire des Habsbourgs. Mais ses parents décident de déménager à Vienne, de quitter la Hongrie détachée de l’Empire. A Vienne, il adhère aux Burschenschaften (les Corporations étudiantes) sionistes car les autres n’acceptent pas les étudiants d’origine juive. Il s’y frotte à un sionisme de droite, inspiré par l’idéologue Max Nordau, théoricien d’une vision très nietzschéenne de la décadence. Koestler va vouloir jouer le jeu sioniste jusqu’au bout: il abandonne tout, brûle son livret d’étudiant et part en Palestine. Il y découvrira l’un des premiers kibboutzim, un véritable nid de misère au fin fond d’une vallée aride. Pour les colons juifs qui s’y accrochaient, c’était une sorte de nouveau phalanstérisme de gauche, regroupant des croyants d’une mouture nouvelle, attendant une parousie laïque et agrarienne sur une terre censée avoir appartenu à leurs ancêtres judéens.

Ensuite, nous avons le Koestler grand journaliste de la presse berlinoise qui appuie la République de Weimar et l’idéologie d’un Thomas Mann. Mais cette presse, aux mains de la famille Ullstein, famille israélite convertie au protestantisme prussien, basculera vers la droite et finira par soutenir les nationaux-socialistes. Entretemps, Koestler vire au communisme —parce qu’il n’y a rien d’autre à faire— et devient un militant exemplaire du Komintern, à Berlin d’abord puis à Paris en exil. Il fait le voyage en URSS et devient un bon petit soldat du Komintern, même si ce qu’il a vu entre l’Ukraine affamée par l’Holodomor et la misère pouilleuse du lointain Turkménistan soviétique induit une certaine dose de scepticisme dans son coeur.

Sionisme et communisme: de terribles simplifications