|

Robert STEUCKERS :

Relire Soljénitsyne

Conférence tenue à Genève, avril 2009, et au « Cercle de Bruxelles », septembre 2009

Pourquoi évoquer la figure d’Alexandre Soljénitsyne, aujourd’hui, dans le cadre de nos travaux ? Décédé en août 2008, Soljénitsyne a été une personnalité politique et littéraire tout à la fois honnie et adulée en Occident et sur la place de Paris en particulier. Elle a été adulée dans les années 70 car ses écrits ont servi de levier pour faire basculer le communisme soviétique et ont inspiré, soi-disant, la démarche des « nouveaux philosophes » qui entendaient émasculer la gauche française et créer, après ce processus d’émasculation, une gauche anti-communiste, peu encline à soutenir l’URSS en politique internationale. Après cette période d’adulation presque sans bornes, la personne d’Alexandre Soljénitsyne a été honnie, surtout après son discours à Harvard, essentiellement pour cinq motifs : 1) Soljénitsyne critique l’Occident et ses fondements philosophiques et politiques, ce qui n’était pas prévu au programme : on imaginait un Soljénitsyne devenu docile à perpétuité, en remercîment de l’asile reçu en Occident ; 2) Il critique simultanément la chape médiatique qui recouvre toutes les démarches intellectuelles officielles de l’Occident, brisant potentiellement tous les effets de la propagande « soft », émanant des agences de l’ « américanosphère » ; 3) Il critique sévèrement le « joujou pluralisme » que l’Occident a voulu imposer à la Russie, en créant et en finançant des cénacles « russophobes », prêchant la haine du passé russe, des traditions russes et de l’âme russe, lesquelles ne génèrent, selon les « pluralistes », qu’un esprit de servitude ; par les effets du « pluralisme », la Russie était censée s’endormir définitivement et ne plus poser problème à l’hegemon américain ; 4) Il a appelé à la renaissance du patriotisme russe, damant ainsi le pion à ceux qui voulaient disposer sans freins d’une Russie anémiée et émasculée et faire main basse sur ses richesses ; 5) Il s’est réconcilié avec le pouvoir de Poutine, juste au moment où celui-ci était décrié en Occident.

Jeunesse

Ayant vu le jour en 1918, Alexandre Soljénitsyne nait en même temps que la révolution bolchevique, ce qu’il se plaira à souligner à maintes reprises. Il nait orphelin de père : ce dernier, officier dans l’armée du Tsar, est tué lors d’un accident de chasse au cours d’une permission. Le jeune Alexandre est élevé par sa mère, qui consentira à de durs sacrifices pour donner à son garçon une excellente éducation. Fille de propriétaires terriens, elle appartient à une famille brisée par les effets de la révolution bolchevique. Alexandre étudiera les mathématiques, la physique et la philosophie à Rostov sur le Don. Incorporé dans l’Armée Rouge en 1941, l’année de l’invasion allemande, il sert dans un régiment d’artillerie et participe à la bataille de Koursk, qui scelle la défaite de l’Axe en Russie, et à l’Opération Bagration, qui lance la première grande offensive soviétique en direction du Reich. Cette campagne de grande envergure le mènera, devenu officier, en Prusse Orientale, au moment où l’Armée Rouge, désormais victorieuse, s’apprête à avancer vers la Vistule et vers l’Oder. Jusque là son attitude est irréprochable du point de vue soviétique. Soljénitsyne est certes un patriote russe, incorporé dans une armée soviétique dont il conteste secrètement l’idéologie, mais il n’est pas un « vlassoviste » passé à l’Axe, qui entend délivrer la Russie du stalinisme en s’alliant au Reich et à ses alliés (en dépit des réflexes patriotiques que ce même stalinisme a suscité pour inciter les masses russes à combattre les Allemands).

Arrestation et emprisonnement

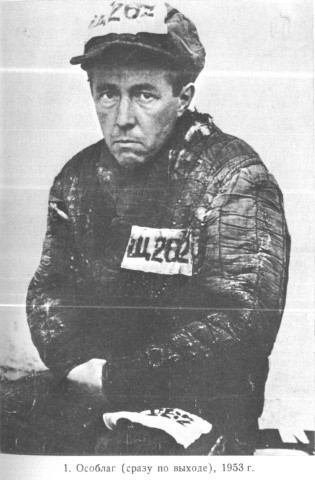

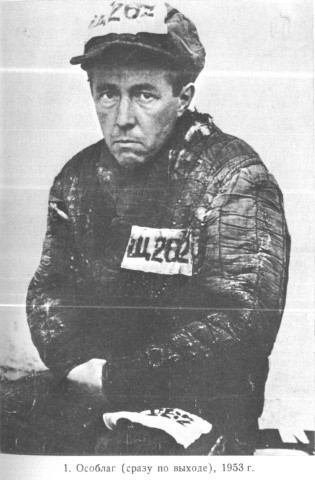

Mais ce que voit Soljénitsyne en Prusse Orientale, les viols, les massacres, les expulsions et les destructions perpétrées par l’Armée Rouge, dont il est officier, le dégoûte profondément, le révulse. L’armée de Staline déshonore la Russie. Le séjour de Soljénitsyne en Prusse Orientale trouve son écho littéraire dans deux ouvrages, « Nuits en Prusse Orientale » (un recueil de poèmes) et « Schwenkitten 45 », un récit où il retourne sur les lieux d’août 1914, où son père a combattu. Le NKVD, la police politique de Staline, l’arrête peu après, sous prétexte qu’il avait été « trop tendre » à l’égard de l’ennemi (ce motif justifiait également l’arrestation de son futur compagnon d’infortune Lev Kopelev) et parce qu’il a critiqué Staline dans une lettre à son beau-frère, interceptée par la police. Staline y était décrit comme « l’homme à la moustache », désignation jugée irrespectueuse et subversive par les commissaires politiques (1). Il est condamné à huit ans de détention, d’abord dans les camps de travail du goulag (ce qui donnera la matière d’ « Une journée d’Ivan Denissovitch » et de « L’Archipel Goulag », puis dans une prison réservée aux scientifiques, la fameuse « prison spéciale n°16 », la Sharashka, dans la banlieue de Moscou. Cette expérience, entre les murs de la prison spéciale n°16, constitue tout à la fois la genèse de l’œuvre et de la pensée ultérieure de notre auteur, y compris les linéaments de sa critique de l’Occident, et la matière d’un grand livre, « Le premier cercle », esquivé par les « nouveaux philosophes » qui n’y auraient pas trouvé leur miel mais, au contraire, une pensée radicalement différente de la leur, qui est, on le sait trop bien, caractérisée par une haine viscérale de toutes « racines » ou enracinements.

Le décor de la Sharashka

Dans la « Sharashka », il rencontre Lev Kopelev (alias le personnage de Roubine) et Dmitri Panine (alias Sologdine). Dans « Le premier cercle », Soljénitsyne lui-même sera représenté par le personnage de « Nergine ». « Le premier cercle » est constitué de dialogues d’une grande fécondité, que l’on peut comparer à ceux de Thomas Mann, tenus dans le sanatorium fictif de la « Montagne magique ». Le séjour à la Sharashka est donc très important pour la genèse de l’œuvre, tant sur le plan de la forme que sur le plan du fond. Pour la forme, pour la spécificité de l’écriture de Soljénitsyne, la découverte, dans la bibliothèque de cette prison, des dictionnaires étymologiques de Vladimir Dahl (un philologue russe d’origine danoise) a été capitale. Elle a permis à Soljénitsyne de récréer une langue russe débarrassée des adstrats maladroits du soviétisme, et des apports étrangers inutiles, lourds et pesants, que l’internationalisme communiste se plaisait à multiplier dans sa phraséologie.

Les pensées des personnages incarcérés à la Sharashka sont celles de larges strates de la population russe, en dissidence par rapport au régime. Ainsi, Dmitri Panine/Sologdine est dès le départ hostile à la révolution. De quelques années plus âgé que Soljénitsyne/Nergine, Panine/Sologdine a rejeté le bolchevisme à la suite d’horreurs dont il a été témoin enfant. Il a été arrêté une première fois en 1940 pour pensée contre-révolutionnaire et une seconde fois en 1943 pour « défaitisme ». Il incarne des valeurs morales absolues, propres aux sociétés fortement charpentées par la religion. Ces valeurs morales vont de paire avec un sens inné de la justice. Panine/Sologdine fascine littéralement Soljénitsyne/Nergine. Notons que des personnages similaires se retrouvent dans « L’Archipel Goulag », ouvrage qui a servi, soi-disant, de détonateur à la « nouvelle philosophie » parisienne des années 70. Mais, apparemment, les « nouveaux philosophes » n’ont pas pris acte de ces personnages-là, pourtant d’une grande importance pour le propos de Soljénitsyne, ce qui nous permet de dire que cette approche fort sélective jette le doute sur la validité même de la « nouvelle philosophie » et de ses avatars contemporains. Pur bricolage idéologique ? Fabrication délibérée ?

Kopelev / Roubine

Lev Kopelev/Roubine est juif et communiste. Il croit au marxisme. Pour lui, le stalinisme n’est qu’une « déviation de la norme ». Il est un homme chaleureux et généreux. Il donne la moitié de son pain à qui en a besoin pour survivre ou pour guérir. Ce geste quotidien de partage, Soljénitsyne l’apprécie grandement. Mais, ironise Soljénitsyne/Nergine, il a besoin d’une agora, contrairement à notre auteur qui, lui, a besoin de solitude (ce sera effectivement le cas à la « prison spéciale n°16 », à Zurich dans les premières semaines d’exil et dans le Vermont aux Etats-Unis). Mort en 1997, Kopelev restera l’ami de Soljénitsyne après leur emprisonnement, malgré leurs différences philosophiques et leurs itinéraires divergents. Il se décarcassera notamment pour trouver tous les volumes du dictionnaire de Dahl et les envoyer à Soljénitsyne. Pourquoi ce communiste militant a-t-il été arrêté, presqu’en même temps que Soljénitsyne ? Il est, dès son jeune âge, un germaniste hors pair et un philosophe de talent. Il sert dans une unité de propagande antinazie qui émet à l’attention des soldats de la Wehrmacht. Il joue également le rôle d’interprète pour quelques généraux allemands, pris prisonniers au cours des grandes offensives soviétiques qui ont suivi la bataille de Koursk. Mais lui aussi est dégoûté par le comportement de certaines troupes soviétiques en Prusse Orientale car il reste un germanophile culturel, bien qu’antinazi. Kopelev/Roubine est véritablement le personnage clef du « Premier cercle ». Pourquoi ? Parce qu’il est communiste, représente la Russie « communisée » mais aussi parce qu’il culturellement germanisé, au contraire de Panine/Sologdine, incarnation de la Russie orthodoxe d’avant la révolution, et de Soljénitsyne/Nergine, et, de ce fait, partiellement « occidentalisé ». Il est un ferment non russe dans la pensée russe, respecté par le russophile Soljénitsyne. Celui-ci va donc analyser, au fil des pages du « Premier cercle », la complexité de ses sentiments, c’est-à-dire des sentiments des Russes soviétisés. Au départ, Soljénitsyne/Nergine et Kopelev/Roubine sont proches politiquement. Nergine n’est pas totalement immunisé contre le soviétisme comme l’est Sologdine. Il en est affecté mais il va guérir. Dans les premières pages du « Premier cercle », Nergine et Roubine s’identifient à l’établissement soviétique. Ce n’est évidemment pas le cas de Sologdine.

Panine / Sologdine

Celui-ci jouera dès lors le rôle clef dans l’éclosion de l’œuvre de Soljénitsyne et dans la prise de distance que notre auteur prendra par rapport au système et à l’idéologie soviétiques. Panine/Sologdine est ce que l’on appelle dans le jargon des prisons soviétiques, un « Tchoudak », c’est-à-dire un « excentrique » et un « inspiré » (avec ou sans relents de mysticisme). Mais Panine/Sologdine, en dépit de cette étiquette que lui collent sur le dos les commissaires du peuple, est loin d’être un mystique fou, un exalté comme en a connus l’histoire russe. Son exigence première est de retourner à « un langage de la clarté maximale », expurgé des termes étrangers, qui frelatent la langue russe et que les Soviétiques utilisaient à tire-larigot. L’objectif de Panine/Sologdine est de re-slaviser la langue pour lui rendre sa pureté et sa richesse, la dégager de tous les effets de « novlangue » apportés par un régime inspiré de philosophies étrangères à l’âme russe.

Le prisonnier réel de la Sharashka et le personnage du « Premier cercle » qu’est Panine/Sologdine a étudié les mathématiques et les sciences, sans pour autant abjurer les pensées contre-révolutionnaires radicales que les scientismes sont censés éradiquer dans l’esprit des hommes, selon les dogmes « progressistes ». Panine/Sologdine entretient une parenté philosophique avec des auteurs comme l’Abbé Barruel, Joseph de Maistre ou Donoso Cortès, dans la mesure où il perçoit le marxisme-léninisme comme un « instrument de Satan », du « mal métaphysique » ; de plus, il est une importation étrangère, comme les néologismes de la langue (de bois) qu’il préconise et généralise. La revendication d’une langue à nouveau claire, non viciée par les alluvions de la propagande, est l’impératif premier que pose ce contre-révolutionnaire indéfectible. C’est lui qui demande que l’on potasse les dictionnaires étymologiques de Vladimir Dahl car le retour à l’étymologie est un retour à la vérité première de la langue russe, donc de la Russie et de la russéité. Les termes fabriqués par l’idéologie ou les importations étrangères constituent une chape de « médiateté » qui interdit aux Russes soviétisés de se réconcilier avec leur cœur profond. « Le Premier cercle » rapporte une querelle philosophique entre Panine/Sologdine et Soljénitsyne/Nergine : ce dernier est tenté par la sagesse chinoise de Lao Tseu, notamment par deux maximes, « Plus il y a de lois et de règlements, plus il y aura de voleurs et de hors-la-loi » et « L’homme noble conquiert sans le vouloir ». Soljénitsyne les fera toujours siennes mais, fidèle à un anti-asiatisme foncier propre à la pensée russe entre 1870 et la révolution bolchevique, Panine/Sologdine rejette toute importation de « chinoiseries », proclame sa fidélité indéfectible au fond qui constitue la tradition chrétienne orthodoxe russe, postulant une « foi en Dieu sans spéculation ».

L’éclosion d’une pensée politique véritablement russe

Dans le contexte même de la rencontre de ces trois personnages différents entre les murailles de la Sharashka, avec un Soljénitsyne/Nergine au départ vierge de toute position tranchée, la pensée du futur dissident soviétique, Prix Nobel de littérature et fustigateur de l’Occident décadent et hypocrite, va mûrir, se forger, prendre les contours qu’elle n’abandonnera jamais plus. Face à ses deux principaux interlocuteurs de la Sharashka, la première intention de Soljénitsyne/Nergine est d’écrire une histoire de la révolution d’Octobre et d’en dégager le sens véritable, lequel, pense-t-il au début de sa démarche, est léniniste et non pas stalinien. Pour justifier ce léninisme antistalinien, Soljénitsyne/Nergine interroge Kopelev/Roubine, fin connaisseur de tous les détails qui ont précédé puis marqué cette révolution et la geste personnelle de Lénine. Kopelev/Roubine est celui qui fournit la matière brute. Au fil des révélations, au fur et à mesure que Soljénitsyne/Roubine apprend faits et dessous de la révolution d’Octobre, son intention première, qui était de prouver la valeur intrinsèque du léninisme pur et de critiquer la déviation stalinienne, se modifie : désormais il veut formuler une critique fondamentale de la révolution. Pour le faire, il entend poser une batterie de questions cruciales : « Si Lénine était resté au pouvoir, y aurait-il eu ou non campagne contre les koulaks (l’Holodomor ukrainien), y aurait-il eu ou non collectivisation, famine ? ». En tentant de répondre à ces questions, Soljénitsyne demeure antistalinien mais se rend compte que Staline n’est pas le seul responsable des errements du communisme soviétique. Le mal a-t-il des racines léninistes voire des racines marxistes ? Soljénitsyne poursuit sa démarche critique et en vient à s’opposer à Kopelev, en toute amitié. Pour Kopelev, en dépit de sa qualité d’israélite russe et de prisonnier politique, pense que Staline incarne l’alliance entre l’espérance communiste et le nationalisme russe. En prison, à la Sharashka, Kopelev en arrive à justifier l’impérialisme rouge, dans la mesure où il est justement « impérial » et à défendre des positions « nationales et bolcheviques ». Kopelev admire les conquêtes de Staline, qui est parvenu à édifier un bloc impérial, dominé par la nation russe, s’étendant « de l’Elbe à la Mandchourie ». Soljénitsyne ne partage pas l’idéal panslaviste, perceptible en filigrane derrière le discours de Kopelev/Roubine. Il répétera son désaccord dans les manifestes politiques qu’il écrira à la fin de sa vie dans une Russie débarrassée du communisme. Les Polonais catholiques ne se fondront jamais dans un tel magma ni d’ailleurs les Tchèques trop occidentalisés ni les Serbes qui, dit Soljénitsyne, ont entrainé la Russie dans une « guerre désastreuse » en 1914, dont les effets ont provoqué la révolution. Dans les débats entre prisonniers à la Sharashka, Soljénitsyne/Nergine opte pour une russéité non impérialiste, repliée sur elle-même ou sur la fraternité entre Slaves de l’Est (Russes/Grands Russiens, Ukrainiens et Biélorusses).

Panine, le maître à penser

Pour illustrer son anti-impérialisme en gestation, Soljénitsyne évoque une réunion de soldats en 1917, à la veille de la révolution quand l’armée est minée par la subversion bolchevique. L’orateur, chargé de les haranguer, appelle à poursuivre la guerre ; il évoque la nécessité pour les Russes d’avoir un accès aux mers chaudes. Cet argument se heurte à l’incompréhension des soldats. L’un d’eux interpelle l’orateur : « Va te faire foutre avec tes mers ! Que veux-tu qu’on en fasse, qu’on les cultive ? ». Soljénitsyne veut démontrer, en évoquant cette verte réplique, que la mentalité russe est foncièrement paysanne, tellurique et continentale. Le vrai Russe, ne cessera plus d’expliquer Soljénitsyne, est lié à la glèbe, il est un « pochvennik ». Il est situé sur un sol précis. Il n’est ni un nomade ni un marin. Ses qualités se révèlent quand il peut vivre un tel enracinement. Ce « pochvennikisme », associé chez Soljénitsyne à un certain quiétisme inspiré de Lao Tseu, conduit aussi à une méfiance à l’endroit de l’Etat, de tout « Big Brother » (à l’instar de Proudhon, Bakounine voire Sorel). Ce glissement vers l’idéalisation du « pochvennik » rapproche Soljénitsyne/Nergine de Panine/Sologdine et l’éloigne de Kopelev/Roubine, dont il était pourtant plus proche au début de son séjour dans la Sharashka. Le fil conducteur du « Premier cercle » est celui qui nous mène d’une position vaguement léniniste, dépourvue de toute hostilité au soviétisme, à un rejet du communisme dans toutes ses facettes et à une adhésion à la vision traditionnelle et slavophile de la russéité, portée par la figure du paysan « pochvennik ». Panine fut donc le maître à penser de Soljénitsyne.

Ce ruralisme slavophile de Soljénitsyne, né à la suite des discussions entre détenus à la Sharashka, ne doit pas nous induire à poser un jugement trop hâtif sur la philosophie politique de Soljénitsyne. On sait que le rejet de la mer constitue un danger et signale une faiblesse récurrente des pensées politiques russes ou allemandes. Oswald Spengler opposait l’idéal tellurique du chevalier teutonique, œuvrant sur terre, à la figure négative du pirate anglo-saxon, inspiré par les Vikings. Arthur Moeller van den Bruck préconisait une alliance des puissances continentales contre les thalassocraties. Carl Schmitt penche sentimentalement du côté de la Terre dans l’opposition qu’il esquisse dans « Terre et Mer », ou dans son « Glossarium » édité dix ans après sa mort, et exalte parfois la figure du « géomètre romain », véritable créateur d’Etats et d’Empires. Friedrich Ratzel et l’Amiral Tirpitz ne cesseront, devant cette propension à « rester sur le plancher des vaches », de dire que la Mer donne la puissance et que les peuples qui refusent de devenir marins sont condamnés à la récession permanente et au déclin politique. L’Amiral Castex avancera des arguments similaires quand il exhortera les Français à consolider leur marine dans les années 50 et 60.

Les ouvrages des années 90

Pourquoi l’indubitable fascination pour la glèbe russe ne doit pas nous inciter à considérer la pensée politique de Soljénitsyne comme un pur tellurisme « thalassophobe » ? Dans ses ouvrages ultérieurs, comme « L’erreur de l’Occident » (1980), encore fort emprunt d’un antisoviétisme propre à la dissidence issue du goulag, comme « Nos pluralistes » (1983), « Comment réaménager notre Russie ? » (1990) et « La Russie sous l’avalanche » (1998), Soljénitsyne prendra conscience de beaucoup de problèmes géopolitiques : il évoquera les manœuvres communes des flottes américaine, turque et ukrainienne en Mer Noire et entreverra tout l’enjeu que comporte cette mer intérieure pour la Russie ; il parlera aussi des Kouriles, pierre d’achoppement dans les relations russo-japonaises, et avant-poste de la Russie dans les immensités du Pacifique ; enfin, il évoquera aussi, mais trop brièvement, la nécessité d’avoir de bons rapports avec la Chine et l’Inde, ouvertures obligées vers deux grands océans de la planète : l’Océan Indien et le Pacifique. « La Russie sous l’avalanche », de 1998, est à cet égard l’ouvrage de loin le mieux construit de tous les travaux politiques de Soljénitsyne au soir de sa vie. Le livre est surtout une dénonciation de la politique de Boris Eltsine et du type d’économie qu’ont voulu introduire des ministres comme Gaïdar et Tchoubaïs. Leur projet était d’imposer les critères du néo-libéralisme en Russie, notamment par la dévaluation du rouble et par la vente à l’encan des richesses du pays. Nous y reviendrons.

La genèse de l’œuvre et de la pensée politique de Soljénitsyne doit donc être recherchée dans les discussions entre prisonniers à la Sharashka, dans la « Prison spéciale n°16 », où étaient confinés des intellectuels, contraints de travailler pour l’armée ou pour l’Etat. Soljénitsyne purgera donc in extenso les huit années de détention auxquelles il avait été condamné en 1945, immédiatement après son arrestation sur le front, en Prusse Orientale. Il ne sera libéré qu’en 1953. De 1953 à 1957, il vivra en exil, banni, à Kok-Terek au Kazakhstan, où il exercera la modeste profession d’instituteur de village. Il rédige « Le Pavillon des cancéreux », suite à un séjour dans un sanatorium. Réhabilité en 1957, il se fixe à Riazan. Son besoin de solitude demeure son trait de caractère le plus spécifique, le plus étalé dans la durée. Il s’isole et se retire dans des cabanes en forêt. La genèse de l’œuvre et de la pensée politique de Soljénitsyne doit donc être recherchée dans les discussions entre prisonniers à la Sharashka, dans la « Prison spéciale n°16 », où étaient confinés des intellectuels, contraints de travailler pour l’armée ou pour l’Etat. Soljénitsyne purgera donc in extenso les huit années de détention auxquelles il avait été condamné en 1945, immédiatement après son arrestation sur le front, en Prusse Orientale. Il ne sera libéré qu’en 1953. De 1953 à 1957, il vivra en exil, banni, à Kok-Terek au Kazakhstan, où il exercera la modeste profession d’instituteur de village. Il rédige « Le Pavillon des cancéreux », suite à un séjour dans un sanatorium. Réhabilité en 1957, il se fixe à Riazan. Son besoin de solitude demeure son trait de caractère le plus spécifique, le plus étalé dans la durée. Il s’isole et se retire dans des cabanes en forêt.

La parution d’ « Une journée d’Ivan Denissovitch »

La consécration, l’entrée dans le panthéon de la littérature universelle, aura lieu en 1961-62, avec la publication d’ « Une journée d’Ivan Denissovitch », un manuscrit relatant la journée d’un « zek » (le terme soviétique pour désigner un détenu du goulag). Lev Kopelev avait lu le manuscrit et en avait décelé le génie. Surfant sur la vague de la déstalinisation, Kopelev s’adresse à un ami de Khrouchtchev au sein du Politburo de l’Union Soviétique, un certain Tvardovski. Khrouchtchev se laisse convaincre. Il autorise la publication du livre, qu’il perçoit comme un témoignage intéressant pour appuyer sa politique de déstalinisation. « Une journée d’Ivan Denissovitch » est publiée en feuilleton dans la revue « Novi Mir ». Personne n’avait jamais pu exprimer de manière aussi claire, limpide, ce qu’était réellement l’univers concentrationnaire. Ivan Denissovitch Choukhov, dont Soljénitsyne relate la journée, est un paysan, soit l’homme par excellence selon Soljénitsyne, désormais inscrit dans la tradition ruraliste des slavophiles russes. Trois vertus l’animent malgré son sort : il reste goguenard, ne croit pas aux grandes idées que l’on présente comme des modèles mirifiques aux citoyens soviétiques ; il est impavide et, surtout, ne garde aucune rancune : il pardonne. L’horreur de l’univers concentrationnaire est celle d’un interminable quotidien, tissé d’une banalité sans nom. Le bonheur suprême, c’est de mâchonner lentement une arête de poisson, récupérée en « rab » chez le cuisinier. Dans cet univers, il y a peut-être un salut, une rédemption, en bout de course pour des personnalités de la trempe d’un Ivan Denissovitch, mais il n’y en aura pas pour les salauds, dont la définition n’est forcément pas celle qu’en donnait Sartre : le salaud dans l’univers éperdument banal d’Ivan Denissovitch, c’est l’intellectuel ou l’esthète désincarnés.

Trois personnages animent la journée d’Ivan Denissovitch : Bouynovski, un communiste qui reste fidèle à son idéal malgré son emprisonnement ; Aliocha, le chrétien renonçant qui refuse une église inféodée à l’Etat ; et Choukhov, le païen stoïque issu de la région de Riazan, dont il a l’accent et dont il maîtrise le dialecte. Soljénitsyne donnera le dernier mot à ce païen stoïque, dont le pessimisme est absolu : il n’attend rien ; il cultive une morale de la survie ; il accomplit sa tâche (même si elle ne sert à rien) ; il ne renonce pas comme Aliocha mais il assume son sort. Ce qui le sauve, c’est qu’il partage ce qu’il a, qu’il fait preuve de charité ; le négateur païen du Dieu des chrétiens refait, quand il le peut, le geste de la Cène. En cela, il est le modèle de Soljénitsyne.

Retour de pendule

« Une journée d’Ivan Denissovitch » connaît un succès retentissant pendant une vingtaine de mois mais, en 1964, avec l’accession d’une nouvelle troïka au pouvoir suprême en Union Soviétique, dont Brejnev était l’homme fort, s’opère un retour de pendule. En 1965, le KGB confisque le manuscrit du « Premier cercle ». En 1969, Soljénitsyne est exclu de l’association des écrivains. En guise de riposte à cette exclusion, les Suédois lui accordent le Prix Nobel de littérature en 1970. Soljénitsyne ne pourra pas se rendre à Stockholm pour le recevoir. La répression post-khrouchtchévienne oblige Soljénitsyne, contre son gré, à publier « L’Archipel goulag » à l’étranger. Cette publication est jugée comme une trahison à l’endroit de l’URSS. Soljénitsyne est arrêté pour trahison et expulsé du territoire. La nuit du 12 au 13 février 1974, il débarque d’un avion à l’aéroport de Francfort sur le Main en Allemagne puis se rend à Zurich en Suisse, première étape de son long exil, qu’il terminera à Cavendish dans le Vermont aux Etats-Unis. Ce dernier refuge a été, pour Soljénitsyne, un isolement complet de dix-huit ans.

Euphorie en Occident

De 1974 à 1978, c’est l’euphorie en Occident. Soljénitsyne est celui qui, à son corps défendant, valorise le système occidental et réceptionne, en sa personne, tout le mal que peut faire subir le régime adverse, celui de l’autre camp de la guerre froide. C’est la période où émerge du néant la « nouvelle philosophie » à Paris, qui se veut antitotalitaire et se réclame de Soljénitsyne sans pourtant l’avoir lu entièrement, sans avoir capté véritablement le message du « Premier cercle », le glissement d’un léninisme de bon aloi, parce qu’antistalinien, vers des positions slavophiles, totalement incompatibles avec celles de la brochette d’intellos parisiens qui se vantaient d’introduire dans le monde entier une « nouvelle philosophie » à prétentions universalistes. La « nouvelle philosophie » révèle ainsi son statut de pure fabrication médiatique. Elle s’est servi de Soljénitsyne et de sa dénonciation du goulag pour faire de la propagande pro-américaine, en omettant tous les aspects de son œuvre qui indiquaient des options incompatibles avec l’esprit occidental. Dans ce contexte, il faut se rappeler que Kissinger avait empêché Gerald Ford, alors président des Etats-Unis, d’aller saluer Soljénitsyne, car, avait-il dit, sans nul doute en connaissant les véritables positions slavophiles de notre auteur, « ses vues embarrassent même les autres dissidents » (c’est-à-dire les « zapadnikis », les occidentalistes). Ce hiatus entre le Soljénitsyne des propagandes occidentales et de la « nouvelle philosophie », d’une part, et le Soljénitsyne véritable, slavophile et patriote russe anti-impérialiste, d’autre part, conduira à la thèse centrale d’un ouvrage polémique de notre auteur, « Nos pluralistes » (1983). Dans ce petit livre, Soljénitsyne dénonce tous les mécanismes d’amalgame dont usent les médias. Son argument principal est le suivant : les « pluralistes », porte-voix des pseudo-vérités médiatiques, énoncent des affirmations impavides et non vérifiées, ne retiennent jamais les leçons de l’histoire réelle (alors que Soljénitsyne s’efforce de la reconstituer dans la longue fresque à laquelle il travaille et qui nous emmène d’août 1914 au triomphe de la révolution) ; les « pluralistes », qui sévissent en Russie et y répandent la propagande occidentale, avancent des batteries d’arguments tout faits, préfabriqués, qu’on ne peut remettre en question, sous peine de subir les foudres des nouveaux « bien-pensants ». Le « pluralisme », parce qu’il refuse toute contestation de ses propres a priori, n’est pas un pluralisme et les « pluralistes » qui s’affichent tels sont tout sauf d’authentiques pluralistes ou de véritables démocrates.

Dès 1978, dès son premier discours à Harvard, Soljénitsyne dénonce le vide spirituel de l’Occident et des Etats-Unis, leur matérialisme vulgaire, leur musique hideuse et intolérable, leur presse arrogante et débile qui viole sans cesse la vie privée. Ce discours jette un froid : « Comment donc ! Ce Soljénitsyne ne se borne pas à n’être qu’un simple antistalinien antitotalitaire et occidentaliste ? Il est aussi hostile à toutes les mises au pas administrées aux peuples par l’hegemon américain ! ». Scandale ! Bris de manichéisme ! Insolence à l’endroit de la bien-pensance !

« La Roue Rouge »

De 1969 à 1980, Soljénitsyne va se consacrer à sa grande œuvre, celle qu’il s’était promise d’écrire lorsqu’il était enfermé entre les murs de la Sharashka. Il s’attelle à la grande fresque historique de l’histoire de la Russie et du communisme. La série intitulée « La Roue Rouge » commence par un volume consacré à « Août 1914 », qui paraît en français, à Paris, en 1973, peu avant son expulsion d’URSS. La parution de cette fresque en français s’étalera de 1973 à 1997 (« Mars 1917 » paraitra en trois volumes chez Fayard). « Août 1914 » est un ouvrage très dense, stigmatisant l’amateurisme des généraux russes et, ce qui est plus important sur le plan idéologique et politique, contient une réhabilitation de l’œuvre de Stolypine, avec son projet de réforme agraire. Pour retourner à elle-même, sans sombrer dans l’irréalisme romantique ou néo-slavophile, après les sept décennies de totalitarisme communiste, la Russie doit opérer un retour à Stolypine, qui fut l’unique homme politique russe à avoir développé un projet viable, cohérent, avant le désastre du bolchevisme. La perestroïka et la glasnost ne suffisent pas : elles ne sont pas des projets réalistes, ne constituent pas un programme. L’espoir avant le désastre s’appelait Stolypine. C’est avec son esprit qu’il faut à nouveau communier. Les autres volumes de la « Roue Rouge » seront parachevés en dix-huit ans (« Novembre 1916 », « Mars/Février 1917 », « Août 1917 »). « Février 1917 » analyse la tentative de Kerenski, stigmatise l’indécision de son régime libéral, examine la vacuité du blabla idéologique énoncé par les mencheviks et démontre que l’origine du mal, qui a frappé la Russie pendant sept décennies, réside bien dans ce libéralisme anti-traditionnel. Après la perestroïka, la Russie ne peut en aucun cas retourner à un « nouveau février », comme le faisait Boris Eltsine. La réponse de Soljénitsyne est claire : pas de nouveau menchevisme mais, une fois de plus, retour à Stolypine. « Février 1917 » rappelle aussi le rôle du banquier juif allemand Halphand, alias Parvus, dans le financement de la révolution bolchevique, avec l’appui des autorités militaires et impériales allemandes, soucieuses de se défaire d’un des deux fronts sur lequel combattaient leurs armées. Les volumes de la « Roue Rouge » ne seront malheureusement pas des succès de librairie en France et aux Etats-Unis (sauf « Août 1914 ») ; en Russie, ces volumes sont trop longs à lire pour la jeune génération.

Retour à Moscou par la Sibérie

Le 27 mai 1994, Soljénitsyne retourne en Russie et débarque à Magadan en Sibérie orientale, sur les côtes de la Mer d’Okhotsk. Son arrivée à Moscou sera précédée d’un « itinéraire sibérien » de deux mois, parcouru en dix-sept étapes. Pour notre auteur, ce retour en Russie par la Sibérie sera marqué par une grande désillusion, pour cinq motifs essentiellement : 1) l’accroissement de la criminalité, avec le déclin de toute morale naturelle ; 2) la corruption politique omniprésente ; 3) le délabrement général des cités et des sites industriels désaffectés, de même que celui des services publics ; 4) la démocratie viciée ; 5) le déclin spirituel.

La position de Soljénitsyne face à la nouvelle Russie débarrassée du communisme est donc celle du scepticisme (tout comme Alexandre Zinoviev) à l’égard de la perestroïka et de la glasnost. Gorbatchev, aux yeux de Soljénitsyne et de Zinoviev, n’inaugure donc pas une renaissance mais marque le début d’un déclin. Le grand danger de la débâcle générale, commencée dès la perestroïka gorbatchévienne, est de faire apparaître le système soviétique désormais défunt comme un âge d’or matériel. Soljénitsyne et Zinoviev constatent donc le statut hybride du post-soviétisme : les résidus du soviétisme marquent encore la société russe, l’embarrassent comme un ballast difficile à traîner, et sont désormais flanqués d’éléments disparates importés d’Occident, qui se greffent mal sur la mentalité russe ou ne constituent que des scories dépourvus de toute qualité intrinsèque.

Critique du gorbatchévisme et de la politique d’Eltsine

Déçu par le gorbatchévisme, Soljénitsyne va se montrer favorable à Eltsine dans un premier temps, principalement pour le motif qu’il a été élu démocratiquement. Qu’il est le premier russe élu par les urnes depuis près d’un siècle. Mais ce préjugé favorable fera long feu. Soljénitsyne se détache d’Eltsine et amorce une critique de son pouvoir pour deux raisons : 1) il n’a pas défendu les Russes ethniques dans les nouvelles républiques de la CEI ; 2) il vend le pays et ses ressources à des consortiums étrangers.

Au départ, Soljénitsyne était hostile à Poutine, considérant qu’il était une figure politique issue des cénacles d’Eltsine. Mais Poutine, discret au départ, va se métamorphoser et se poser comme celui qui combat les stratégies de démembrement préconisées par Zbigniew Brzezinski, notamment dans son livre « Le Grand Echiquier » (« The Grand Chessboard »). Il est l’homme qui va sortir assez rapidement la Russie du chaos suicidaire de la « Smuta » (2) post-soviétique. Soljénitsyne se réconciliera avec Poutine en 2007, arguant que celui-ci a hérité d’un pays totalement délabré, l’a ensuite induit sur la voie de la renaissance lente et graduelle, en pratiquant une politique du possible. Cette politique vise notamment à conserver les richesses minières, pétrolières et gazières de la Russie entre des mains russes.

Le voyage en Vendée

En 1993, sur invitation de Philippe de Villers, Soljénitsyne se rend en Vendée pour commémorer les effroyables massacres commis par les révolutionnaires français deux cent années auparavant. Les « colonnes infernales » des « Bleus » pratiquaient la politique de « dépopulation » dans les zones révoltées, politique qui consistait à exterminer les populations rurales entrées en rébellion contre la nouvelle « république ». Dans le discours qu’il tiendra là-bas le 25 septembre 1993, Soljénitsyne a rappelé que les racines criminelles du communisme résident in nuce dans l’idéologie républicaine de la révolution française ; les deux projets politiques, également criminels dans leurs intentions, sont caractérisés par une haine viscérale et insatiable dirigée contre les populations paysannes, accusées de ne pas être réceptives aux chimères et aux bricolages idéologiques d’une caste d’intellectuels détachés des réalités tangibles de l’histoire. La stratégie de la « dépopulation » et la pratique de l’exterminisme, inaugurés en Vendée à la fin du 18ème siècle, seront réanimées contre les koulaks russes et ukrainiens à partir des années 20 du 20ème siècle. Ce discours, très logique, présentant une généalogie sans faille des idéologies criminelles de la modernité occidentale, provoquera la fureur des cercles faisandés du « républicanisme » français, placés sans ménagement aucun par une haute sommité de la littérature mondiale devant leurs propres erreurs et devant leur passé nauséabond. Soljénitsyne deviendra dès lors une « persona non grata », essuyant désormais les insultes de la presse parisienne, comme tous les Européens qui osent professer des idées politiques puisées dans d’autres traditions que ce « républicanisme » issu du cloaque révolutionnaire parisien (cette hostilité haineuse vaut pour les fédéralistes alpins de Suisse ou de Savoie, de Lombardie ou du Piémont, les populistes néerlandais ou slaves, les solidaristes ou les communautaristes enracinés dans des continuités politiques bien profilées, etc. qui ne s’inscrivent dans aucun des filons de la révolution française, tout simplement parce que ces filons n’ont jamais été présents dans leurs pays). On a même pu lire ce titre qui en dit long dans une gazette jacobine : « Une crapule en Vendée ». Tous ceux qui n’applaudissent pas aux dragonnades des « colonnes infernales » de Turreau reçoivent in petto ou de vive voix l’étiquette de « crapule ».

Octobre 1994 : le discours à la Douma

En octobre 1994, Soljénitsyne est invité à la tribune de la Douma. Le discours qu’il y tiendra, pour être bien compris, s’inscrit dans le cadre général d’une opposition, ancienne mais revenue à l’avant-plan après la chute du communisme, entre, d’une part, occidentalistes (zapadniki) et, d’autre part, slavophiles (narodniki ou pochvenniki, populistes ou « glèbistes »). Cette opposition reflète le choc entre deux anthropologies, représentées chacune par des figures de proue : Sakharov pour les zapadniki et Soljénitsyne pour les narodniki. Sakharov et les zapadniki défendaient dans ce contexte une « idéologie de la convergence », c’est-à-dire d’une convergence entre les « deux capitalismes » (le capitalisme de marché et le capitalisme monopoliste d’Etat). Sakharov et son principal disciple Alexandre Yakovlev prétendaient que cette « idéologie de la convergence » annonçait et préparait une « nouvelle civilisation mondiale » qui adviendrait par le truchement de l’économie. Pour la faire triompher, il faut « liquider les atavismes », encore présents dans la religion et dans les sentiments nationaux des peuples et dans les réflexes de fierté nationale. La liquidation des atavismes s’effectuera par le biais d’un « programme de rééducation » qui fera advenir une « nouvelle raison ». Dans son discours à la Douma, Soljénitsyne fustige cette « idéologie de la convergence » et cette volonté d’éradiquer les atavismes. L’une et l’autre sont mises en œuvre par les « pluralistes » dont il dénonçait déjà les manigances et les obsessions en 1983. Ces « pluralistes » ne se contentent pas d’importer des idées occidentales préfabriquées, tonnait Soljénitsyne du haut de la chaire de la Douma, mais ils dénigrent systématique l’histoire russe et toutes les productions issues de l’âme russe : le discours des « pluralistes » répète à satiété que les Russes sont d’incorrigibles « barbares », sont « un peuple d’esclaves qui aiment la servitude », qu’ils sont mâtinés d’esprit mongol ou tatar et que le communisme n’a jamais été autre chose qu’une expression de cette barbarité et de cet esprit de servitude. Le programme du « républicanisme » et de l’ « universalisme » français (parisien) est très similaire à celui des « pluralistes zapadnikistes » russes : les Français sont alors campés comme des « vichystes » sournois et incorrigibles et toutes les idéologies françaises, même celles qui se sont opposées à Vichy, sont accusées de receler du « vichysme », comme le personnalisme de Mounier ou le gaullisme. C’est contre ce programme de liquidation des atavismes que Soljénitsyne s’insurge lors de son discours à la Douma d’Etat. Il appelle les Russes à le combattre. Ce programme, ajoutait-il, s’enracine dans l’idéologie des Lumières, laquelle est occidentale et n’a jamais procédé d’un humus russe. L’âme russe, par conséquent, ne peut être tenue responsable des horreurs qu’a générées l’idéologie des Lumières, importation étrangère. Rien de ce qui en découle ne peut apporter salut ou solutions pour la Russie postcommuniste. Soljénitsyne reprend là une thématique propre à toute la dissidence est-européenne de l’ère soviétique, qui s’est révoltée contre la volonté d’une minorité activiste, détachée du peuple, de faire advenir un « homme nouveau » par dressage totalitaire (Leszek Kolakowski). Cet homme nouveau ne peut être qu’un sinistre golem, qu’un monstre capable de toutes les aberrations et de toutes les déviances politico-criminelles.

« Comment réaménager notre Russie ? »

Mais en quoi consiste l’alternative narodniki, préconisée par Soljénitsyne ? Celui-ci ne s’est-il pas contenté de fustiger les pratiques métapolitiques des « pluralistes » et des « zapadnikistes », adeptes des thèses de Sakharov et Yakovlev ? Les réponses se trouvent dans un ouvrage paru en 1991, « Comment réaménager notre Russie ? ». Soljénitsyne y élabore un véritable programme politique, valable certes pour la Russie, mais aussi pour tous les pays souhaitant se soustraire du filon idéologique qui va des « Lumières » au « Goulag ».

Soljénitsyne préconise une « démocratie qualitative », basée sur un vote pour des personnalités, dégagée du système des partis et assise sur l’autonomie administrative des régions. Une telle « démocratie qualitative » serait soustraite à la logique du profit et détachée de l’hyperinflation du système bancaire. Elle veillerait à ne pas aliéner les ressources nationales (celles du sol, les richesses minières, les forêts), en n’imitant pas la politique désastreuse d’Eltsine. Dans une telle « démocratie qualitative », l’économie serait régulée par des normes éthiques. Son fonctionnement serait protégé par la verticalité d’un pouvoir présidentiel fort, de manière à ce qu’il y ait équilibre entre la verticalité de l’autorité présidentielle et l’horizontalité d’une démocratie ancrée dans la substance nationale russe et liée aux terres russes.

La notion de « démocratie qualitative »

Une telle « démocratie qualitative » passe par une réhabilitation des villages russes, explique Soljénitsyne en s’inscrivant très nettement dans le filon slavophile russe, dont les inspirations majeures sont ruralistes et « glèbistes » (pochvenniki). Cette réhabilitation a pour corollaire évident de promouvoir, sur les ruines du communisme, des communautés paysannes ou un paysannat libre, maîtres de leur propre sol. Cela implique ipso facto la liquidation du système kolkhozien. La « démocratie qualitative » veut également réhabiliter l’artisanat, un artisanat qui serait propriétaire de ses moyens de production. Les fonctionnaires ont été corrompus par la libéralisation post-soviétique. Ce fonctionnariat devenu voleur devrait être éradiqué pour ne laisser aucune chance au « libéralisme de type mafieux », précisément celui qui s’installait dans les marges du pouvoir eltsinien. La Russie sera sauvée, et à nos yeux pas seulement la Russie, si elle se débarrasse de toutes les formes de gouvernement dont la matrice idéologique et « philosophique » dérive des Lumières et du matérialisme qui en découle. Les formes de « libéralisme » et de fausse démocratie, de démocratie sans qualités, ouvrent la voie aux techniques de manipulation, donc à l’asservissement de l’homme par le biais de son déracinement, conclut Soljénitsyne. Dans le vide que créent ces formes politiques dérivées des Lumières, s’installe généralement la domination étrangère par l’intermédiaire d’une dictature d’idéologues, qui procèdent de manière systématique et sauvage à l’asservissement du peuple. Cette domination, étrangère à la substance populaire, enclenche un processus de décadence et de déracinement qui détruit l’homme, dit Soljénitsyne en se mettant au diapason du « renouveau ruraliste » de la littérature russe des années 60 à 80, dont la figure de proue fut Valentin Raspoutine.

De la démarche ethnocidaire

Soljénitsyne dénonce le processus d’ethnocide qui frappe le peuple russe (et bon nombre d’autres peuples). La démarche ethnocidaire, pratiquée par les élites dévoyées par l’idéologie des Lumières, commence par fabriquer, sur le dos du peuple et au nom du « pluralisme », des sociétés composites, c’est-à-dire des sociétés constituées d’un mixage d’éléments hétérogènes. Il s’agit de noyer le peuple-hôte principal et de l’annihiler dans un « melting pot ». Ainsi, le système soviétique, que n’a cessé de dénoncer Soljénitsyne, cherchait à éradiquer la « russéité » du peuple russe au nom de l’internationalisme prolétarien. En Occident, le pouvoir actuel cherche à éradiquer les identités au nom d’un universalisme panmixiste, dont le « républicanisme » français est l’exemple le plus emblématique.

Le 28 octobre 1994, lors de son discours à la Douma d’Etat, Soljénitsyne a répété la quintessence de ce qu’il avait écrit dans « Comment réaménager notre Russie ? ». Dans ce discours d’octobre 1994, Soljénitsyne dénonce en plus le régime d’Eltsine, qui n’a pas répondu aux espoirs qu’il avait éveillés quelques années plus tôt. Au régime soviétique ne s’est pas substitué un régime inspiré des meilleures pages de l’histoire russe mais une pâle copie des pires travers du libéralisme de type occidental qui a précipité la majorité du peuple dans la misère et favorisé une petite clique corrompue d’oligarques vite devenus milliardaires en dollars américains. Le régime eltsinien, parce qu’il affaiblit l’Etat et ruine le peuple, représente par conséquent une nouvelle « smuta ». Soljénitsyne, à la tribune de la Douma, a répété son hostilité au panslavisme, auquel il faut préférer une union des Slaves de l’Est (Biélorusses, Grands Russiens et Ukrainiens). Il a également fustigé la partitocratie qui « transforme le peuple non pas en sujet souverain de la politique mais en un matériau passif à traiter seulement lors des campagnes électorales ». De véritables élections, capables de susciter et de consolider une « démocratie qualitative », doivent se faire sur base locale et régionale, afin que soit brisée l’hégémonie nationale/fédérale des partis qui entendent tout régenter depuis la capitale. Les concepts politiques véritablement russes ne peuvent éclore qu’aux dimensions réduites des régions russes, fort différentes les unes des autres, et non pas au départ de centrales moscovites ou pétersbourgeoises, forcément ignorantes des problèmes qui affectent les régions. Le 28 octobre 1994, lors de son discours à la Douma d’Etat, Soljénitsyne a répété la quintessence de ce qu’il avait écrit dans « Comment réaménager notre Russie ? ». Dans ce discours d’octobre 1994, Soljénitsyne dénonce en plus le régime d’Eltsine, qui n’a pas répondu aux espoirs qu’il avait éveillés quelques années plus tôt. Au régime soviétique ne s’est pas substitué un régime inspiré des meilleures pages de l’histoire russe mais une pâle copie des pires travers du libéralisme de type occidental qui a précipité la majorité du peuple dans la misère et favorisé une petite clique corrompue d’oligarques vite devenus milliardaires en dollars américains. Le régime eltsinien, parce qu’il affaiblit l’Etat et ruine le peuple, représente par conséquent une nouvelle « smuta ». Soljénitsyne, à la tribune de la Douma, a répété son hostilité au panslavisme, auquel il faut préférer une union des Slaves de l’Est (Biélorusses, Grands Russiens et Ukrainiens). Il a également fustigé la partitocratie qui « transforme le peuple non pas en sujet souverain de la politique mais en un matériau passif à traiter seulement lors des campagnes électorales ». De véritables élections, capables de susciter et de consolider une « démocratie qualitative », doivent se faire sur base locale et régionale, afin que soit brisée l’hégémonie nationale/fédérale des partis qui entendent tout régenter depuis la capitale. Les concepts politiques véritablement russes ne peuvent éclore qu’aux dimensions réduites des régions russes, fort différentes les unes des autres, et non pas au départ de centrales moscovites ou pétersbourgeoises, forcément ignorantes des problèmes qui affectent les régions.

« Semstvo » et « opoltcheniyé »

Le peuple doit imiter les anciens, ceux du début du 17ème siècle, et se dresser contre la « smuta » qui ne profite qu’à la noblesse querelleuse (les « boyards »), à la Cour, aux faux prétendants au trône et aux envahisseurs (en l’occurrence les envahisseurs polonais et catholiques). Aujourd’hui, c’est un nouveau profitariat qui exploite le vide eltsinien, soit la nouvelle « smuta » : les « oligarques », la clique entourant Eltsine et le capitalisme occidental, surtout américain, qui cherche à s’emparer des richesses naturelles du sol russe. Au 17ème siècle, le peuple s’était uni au sein de la « semstvo », communauté politique de défense populaire qui avait pris la responsabilité de voler au secours d’une nation en déliquescence. La notion de « semstvo », de responsabilité politique populaire, est inséparable de celle d ‘ « opoltcheniyé », une milice d’auto-défense du peuple qui se constitue pour effacer tous les affres de la « smuta ». C’est seulement à la condition de réanimer l’esprit et les pratiques de la « semstvo » et de l’ « opoltcheniyé » que la Russie se libèrera définitivement des scories du bolchevisme et des misères nouvelles du libéralisme importé pendant la « smuta » eltsinienne. Conclusion de Soljénitsyne : « Pendant la Période des Troubles (= « smuta »), l’idéal civique de la « semstvo » a sauvé la Russie ». Dans l’avenir, ce sera la même chose.

Propos de même teneur dans un entretien accordé au « Spiegel » (Hambourg, n°44/1994), où Soljénitsyne est sommé de s’expliquer par un journaliste adepte des idées libérales de gauche : « On ne peut appeler ‘démocratie’ un système électoral où seulement 30% des citoyens participent au vote ». En effet, les Russes n’accouraient pas aux urnes et les Américains ne se bousculaient pas davantage aux portillons des bureaux de vote. L’absentéisme électoral est la marque la plus patente des régimes démocratiques occidentaux qui ne parviennent plus à intéresser la population à la chose publique. Toujours dans les colonnes du « Spiegel », Soljénitsyne exprime son opinion sur l’Amérique de Bush : « En septembre 1992, le Président américain George Bush a déclaré devant l’Assemblée de l’ONU : ‘Notre objectif est d’installer partout dans le monde l’économie de marché’. C’est une idée totalitaire ». Soljénitsyne s’est ainsi fait l’avocat de la pluralité des systèmes, tout en s’opposant aux prédicateurs religieux et économiques qui tentaient, avec de gros moyens, de vendre leurs boniments en Russie.

Conclusion

L’œuvre de Soljénitsyne, depuis les réflexions inaugurales du « Premier cercle » jusqu’au discours d’octobre 1994 à la Douma et à l’entretien accordé au « Spiegel », est un exemple de longue maturation politique, une initiation pour tous ceux qui veulent entamer les démarches qu’il faut impérativement poser pour s’insurger comme il se doit contre les avatars de l’idéologie des Lumières, responsables d’horreurs sans nom ou de banalités sans ressort, qui ethnocident les peuples par la violence ou l’asservissement. Voilà pourquoi ses livres doivent nous accompagner en permanence dans nos réflexions et nos méditations.

Robert STEUCKERS.

(conférence préparée initialement pour une conférence à Genève et à Bruxelles, à Forest-Flotzenberg, à Pula en Istrie, aux Rochers du Bourbet et sur le sommet du Faux Verger, de janvier à avril 2009).

La présente étude est loin d’être exhaustive : elle vise essentiellement à montrer les grands linéaments d’une pensée politique née de l’expérience de la douleur. Elle ne se concentre pas assez sur le mode d’écriture de Soljénitsyne, bien mis en exergue dans l’ouvrage de Georges Nivat (« Le phénomène Soljénitsyne ») et n’explore pas l’univers des personnages de l’ « Archipel Goulag », l’œuvre étant pour l’essentiel tissée de discussions entre dissidents emprisonnés, exclus du raisonnement politique de leur pays. Une approche du mode d’écriture et une exploration trop approfondie des personnages de l’ « Archipel Goulag » aurait noyé la clarté didactique de notre exposé, destiné à éclairer un public non averti des subtilités de l’oeuvre.

Notes :

(1) Dans son ouvrage sur la bataille de Berlin, l’historien anglais Antony Beevor rappelle que les unités du NKVD et du SMERSH se montrèrent très vigilantes dès l’entrée des troupes soviétiques sur le territoire du Reich, où celles-ci pouvaient juger les réalisations du régime national-socialiste et les comparer à celle du régime soviétique-stalinien. Le parti était également inquiet, rappelle Beevor, parce que, forte de ses victoires depuis Koursk, l’Armée gagnait en prestige au détriment du parti. L’homme fort était Joukov qui faisait de l’ombre à Staline. C’est dans le cadre de cette nervosité des responsables communistes qu’il faut replacer cette vague d’arrestations au sein des forces armées. Beevor rappelle également que les effectifs des ultimes défenseurs de Berlin se composaient comme suit : 45.000 soldats d’unités diverses, dont bon nombre d’étrangers (Norvégiens, Français,…), avec, au moins 10.000 Russes ou ex-citoyens soviétiques (Lettons, Estoniens, etc.) et 40.000 mobilisés du Volkssturm.

(2) Le terme « smuta », bien connu des slavistes et des historiens de la Russie, désigne la période de troubles subie par la Russie entre les dernières années du 16ème siècle et les premières décennies du 17ème. Par analogie, on l’a utilisée pour stigmatiser le ressac général de la Russie comme puissance après la chute du communisme.

Bibliographie :

Outre les ouvrages de Soljénitsyne cités dans cet article, nous avons consulté les livres et articles suivants :

- Jürg ALTWEGG, « Frankreich trauert – Der ‘Schock Solschenizyn’ » , ex : http://www.faz.net/ ou Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 4 août 2008 (l’article se concentre sur l’hommage des anciens « nouveaux philosophes » par un de leurs ex compagnons de route ; monument d’hypocrisie, truffé d’hyperboles verbales).

- Ralph DUTLI, « Zum Tod von Alexander Solschenizyn – Der Prophet im Rad der Geschichte », ex : http://www.faz.net/ ou Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 5 août 2008.

- Aldo FERRARI, La Russia tra Oriente & Occidente, Edizioni Ares, Milano, 1994 (uniquement les chapitre sur Soljénitsyne).

- Giuseppe GIACCIO, « Aleksandr Solzenicyn : Riconstruire l’Uomo », in Diorama Letterario, n°98, novembre 1986.

- Juri GINZBURG, « Der umstrittene Patriarch », ex : http://www.berlinonline.de/berliner-zeitung/archiv/ ou Berliner Zeitung / Magazin, 6 décembre 2003.

- Kerstin HOLM, « Alexander Solschenizyn : Na islomach – Wie lange wird Russland noch von Kriminellen regiert ? », ex : http://www.faz.net/s/Rub79…/ ou Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 20 juillet 1996, N°167, p. 33.

- Kerstin HOLM, « Alexander Solschenizyn : Schwenkitten ’45 – Wider die Architekten der Niedertracht », in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 2 octobre 2004 ou http://www.faz.net/ .

- Kerstin HOLM, « Die russische Krise – Solschenizyn als Geschichtskorektor », ex : http://www.faz.net/s/Rub… ou Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 3 mai 2006.

- Kerstin HOLM, « Solschenizyn : Zwischen zwei Mühlsteinen – Moralischer Röntgenblick », ex : http://www.faz.net/s/ ou Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 26 mai 2006, n°121, p. 34.

- Kerstin HOLM, « Das Gewissen des neuen Russlands », ex : http://www.faz.net/ ou Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 5 août 2008.

- Michael T. KAUFMAN, « Solzhenitsyn, Literary Giant Who defied Soviets, Dies at 89 », The New York Times ou http://www.nytimes.com/ .

- Hildegard KOCHANEK, Die russisch-nationale Rechte von 1968 bis zum Ende der Sowjetunion – Eine Diskursanalyse, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, 1999.

- Lew KOPELEW, Und dennoch hoffen / Texte der deutsche Jahre, Hoffmann und Campe, 1991 (recension par Willy PIETERS, in : Vouloir n°1 (nouvelle série), 1994, p.18.

- Walter LAQUEUR, Der Schoss ist fruchtbar noch – Der militante Nationalismus der russischen Rechten, Kindler, München, 1993 (approche très critique).

- Reinhard LAUER, « Alexander Solschenizyn : Heldenleben – Feldherr, werde hart », ex : http://ww.faz.net/s/Rub79… ou Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 2 avril 1996, n°79, p. L11.

- Jean-Gilles MALLIARAKIS, « Le retour de Soljénitsyne », in Vouloir, n°1 (nouvelle série), 1994, p.18.

- Jaurès MEDVEDEV, Dix ans dans la vie de Soljénitsyne, Grasset, Paris, 1974.

- Georges NIVAT, « Le retour de la parole », in Le Magazine Littéraire, n°263, mars 1989, pp. 18-31.

- Michael PAULWITZ, Gott, Zar, Muttererde : Solschenizyn und die Neo-Slavophilen im heutigen Russland, Burschenschaft Danubia, München, 1990.

- Raf PRAET, « Alexander Solzjenitsyn – Leven, woord en daad van een merkwaardige Rus » (nous n’avons pas pu déterminer l’origine de cet article ; qui peut nous aider ?).

- Gonzalo ROJAS SANCHEZ, « Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008), Arbil, n°118/2008, http://www.arbil.org/ .

- Michael SCAMMELL, Solzhenitsyn – A Biography, Paladin/Grafton Books, Collins, London/Glasgow, 1984-1986.

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Février 1917 dans ‘La Roue Rouge’ de Soljénitsyne », in http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/ (original allemand in Criticon, n°119/1990).

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « La fin du communisme et le prochain retour de Soljénitsyne », in Vouloir, N°83/86, nov.-déc. 1991 (original allemand in Europa Vorn, n°21, nov. 1991).

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Soljénitsyne, Stolypine : le nationalisme russe contre les idées de 1789 », in Vouloir, n°6 (nouvelle série), 1994 (original allemand dans Criticon, n°115, 1989).

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Der neue Streit der Westler und Slawophilen », in Staatsbriefe 2/1992, pp. 8-16.

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, Russland, was nun ?, Eckhartschriften/Heft 124 - Österreichische Landmannschaft, Wien, 1993

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Alexander Solschenizyns Rückkehr in die russische Vendée », in Staatsbriefe 10/1994, pp. 25-31.

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Der Dichter vor der Duma (1) », in Staatsbriefe 11/1994, pp. 18-22.

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Der Dichter vor der Duma (2) », in Staatsbriefe 12/1994, pp. 4-10.

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Solschenizyn, Lebed und die unvollendete Revolution », in Staatsbriefe 1/1997, pp. 5-11.

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Russland, du hast es besser », in Staatsbriefe 1/1997, pp. 12-14.

- Wolfgang STRAUSS, « Kein Ende mit der Smuta », in Staatsbriefe 3/1997, pp. 7-13.

- Reinhard VESER, « Russische Stimmen zu Solschenizyn – Ehrliches Heldentum », ex : http://www.faz.net/ ou Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 4 août 2008.

- Craig R. WHITNEY, «Lev Kopelev, Soviet Writer In Prison 10 Years, Dies at 85 », The New York Times, June 20, 1997 ou http://www.nytimes.com/1997/06/20/world/ .

- Alexandre ZINOVIEV, « Gorbatchévisme », in L’Autre Europe, n°14/1987.

- Alexandre ZINOVIEV, Perestroïka et contre-perestroïka, Olivier Orban, Paris, 1991.

- Alexandre ZINOVIEV, La suprasociété globale et la Russie, L’Age d’Homme, Lausanne, 2000.

Acquis et lu après la conférence :

- Georges NIVAT, Le phénomène Soljénitsyne, Fayard, Paris, 2009. Ouvrage fondamental !

|

...Que faisait Céline un certain soir d’octobre 1933 ? Il dégustait des châtaignes grillées en compagnie de confrères écrivains tels Pierre Mac Orlan, André Thérive, André Salmon, Léon Frapié ou Lucien Descaves. Une fois encore, c’est grâce aux patientes recherches (parallèles) d’Henri Thyssens et de Gaël Richard ¹ dans la presse française de l’époque que la biographie célinienne s’est enrichie de ce détail pittoresque.

...Que faisait Céline un certain soir d’octobre 1933 ? Il dégustait des châtaignes grillées en compagnie de confrères écrivains tels Pierre Mac Orlan, André Thérive, André Salmon, Léon Frapié ou Lucien Descaves. Une fois encore, c’est grâce aux patientes recherches (parallèles) d’Henri Thyssens et de Gaël Richard ¹ dans la presse française de l’époque que la biographie célinienne s’est enrichie de ce détail pittoresque.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Di Henry De Monfreid in Italia si sa poco o niente e sono scarse le traduzioni, disponibili tra l'altro solo da qualche anno. «L'ultimo vero filibustiere della letteratura europea» lo ha invece definito Stenio Solinas. «Ho avuto una ricca, irrequieta e magnifica» dichiarò lo scrittore alcuni giorni prima di morire all'età di 95 anni nel 1974. Prima che autore fu uomo di mare e d'avventure e iniziò a scrivere passati i cinquant'anni. Una seconda vita la sua, quella da scrittore. Anzi la terza. Perchè quando nasce, a La Franqui-Leucate (Aude), sulla costa mediterranea il 14 novembre 1879, c'è solo il mare a presagire che tipo di vita sceglierà.

Di Henry De Monfreid in Italia si sa poco o niente e sono scarse le traduzioni, disponibili tra l'altro solo da qualche anno. «L'ultimo vero filibustiere della letteratura europea» lo ha invece definito Stenio Solinas. «Ho avuto una ricca, irrequieta e magnifica» dichiarò lo scrittore alcuni giorni prima di morire all'età di 95 anni nel 1974. Prima che autore fu uomo di mare e d'avventure e iniziò a scrivere passati i cinquant'anni. Una seconda vita la sua, quella da scrittore. Anzi la terza. Perchè quando nasce, a La Franqui-Leucate (Aude), sulla costa mediterranea il 14 novembre 1879, c'è solo il mare a presagire che tipo di vita sceglierà.

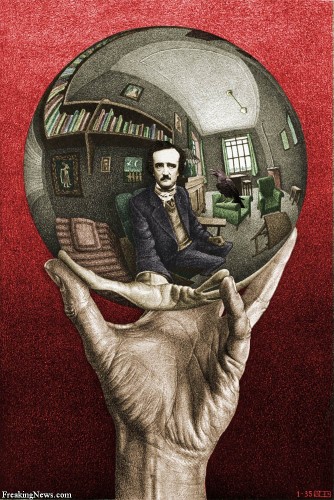

Per Edgar Allan Poe sono gli anni migliori. Ottiene buoni risultati nella sua carriera di giornalista e soprattutto comincia a pubblicare con un certo successo i romanzi e racconti che lo renderanno universalmente famoso. Fra il 1837 e 1838 scrive la “Storia di Arthur Gordon Pym”, un romanzo che secondo il critico Gianfranco De Turris prosegue e riprende un’antica tradizione narrativa (con riferimento ad autori come Coleridge, Swift, Cooper), nella quale sono presenti immagini che si ripetono varie volte: il viaggio per mare, la caduta nell’abisso, le tempeste ed i naufragi che colpiscono i protagonisti, la fame e la pratica del cannibalismo, l’esplorazione di terre sconosciute e il contatto con nuove genti indigene. Tutte queste immagini devono essere considerate anche come elementi di un duro itinerario iniziatico del protagonista che, attraversando l’esperienza del dolore, della morte e della resurrezione, assurge nel finale ad una più sublime e superiore dimensione dell’Essere.

Per Edgar Allan Poe sono gli anni migliori. Ottiene buoni risultati nella sua carriera di giornalista e soprattutto comincia a pubblicare con un certo successo i romanzi e racconti che lo renderanno universalmente famoso. Fra il 1837 e 1838 scrive la “Storia di Arthur Gordon Pym”, un romanzo che secondo il critico Gianfranco De Turris prosegue e riprende un’antica tradizione narrativa (con riferimento ad autori come Coleridge, Swift, Cooper), nella quale sono presenti immagini che si ripetono varie volte: il viaggio per mare, la caduta nell’abisso, le tempeste ed i naufragi che colpiscono i protagonisti, la fame e la pratica del cannibalismo, l’esplorazione di terre sconosciute e il contatto con nuove genti indigene. Tutte queste immagini devono essere considerate anche come elementi di un duro itinerario iniziatico del protagonista che, attraversando l’esperienza del dolore, della morte e della resurrezione, assurge nel finale ad una più sublime e superiore dimensione dell’Essere. N.S.

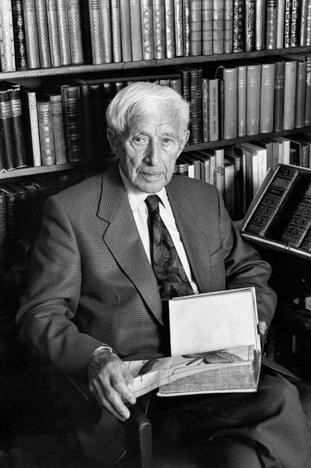

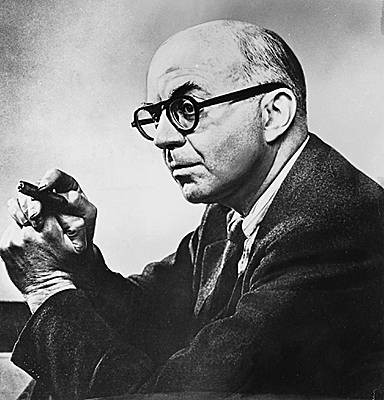

N.S. Così, nel sembrare un pessimista di natura, cerca nei suoi personaggi la chiave per descrivere l’uomo che cade in piedi. Che non è semplice, perché se cadi il segno di un livido ti rimane, cadendo e rimanendo in piedi il dolore lo senti solo dentro. Non è fisico, è solo mentale. Alfonso Nitti, bancario che lascia la mamma e si ritrova in una città che non sembra appartenergli, a cui non vuole appartenere, il personaggio di Una vita ricalca l’archetipo del debole, di colui che si arrende all’amore perché non è amato dalla donna che vorrebbe, che si arrende alla perfezione e alla cura estetica del collega che lo snerva nel suo essere borghese e arrivista, si arrende alla distanza inevitabile del suo capo, il Maller. Solo la morte per quanto crudele e distante, riuscirà ad avvicinarlo alla perfezione della vita, ma questo nemmeno servirà ad sentire più vicini quelli che lui considerava mal volentieri “colleghi”."La Banca Maller, in puro stile burocratico, annuncia un funerale che avviene con l’intervento dei colleghi e della direzione" (Una vita). Alfonso, che si dà colpe non sue, scriverà alla mamma: “Non credere, mamma, che qui si stia tanto male; sono io che ci sto male”. Non faceva nulla e quel nulla lo portava ad avere un’inerzia totale dinnanzi alle cose. Non era stanco, era solo annoiato. Tutti i giorni lì su quella sedia, tutti i giorni a subire e non capire, tutti i giorni un pezzo di vita che si vedeva portar via, ma la cosa assurda è che mentre gli altri “sembravano” contenti di vivere così, Alfonso era contento di non vivere. Avrà ragione Joyce a dire che nella penna di un uomo c’è un solo romanzo e che quando se ne scrivono diversi si tratta sempre del medesimo più o meno trasformato. Così da Una Vita si passa alla Coscienza di Zeno, che nel 1924 Svevo spedisce al suo ormai amico Joyce, trasferitosi a Trieste e suo professore di inglese che Livia Veneziani Svevo descriverà così: “Fra il maestro, oltremodo irregolare, ma d’altissimo ingegno e lo scolaro d’eccezione le lezioni si svolgevano con un andamento fuori dal comune”. Joyce, entusiasta del suo “allievo”, fa conoscere il manoscritto in Francia dove verrà pubblicato. In Italia sarà per merito di Eugenio Montale, sulle pagine della rivista L’Esame, che Svevo riuscirà ad avere la prima notorietà. Zeno Cosini che cerca di guarire da una malattia non ancora ben definita ed inizia il percorso psicoanalitico presso il Dottor S. Dottore che, per quanto poco si sforzi di capire il problema, non riuscirà a farlo e nel momento dell’abbandono della terapia da parte di Zeno si vendicherà pubblicando le memorie del suo paziente con la speranza che questo gli procuri dolore. Ma Zeno, che è più impegnato ad amare la sua sigaretta non farà altro che ridere e deridere il suo analista.

Così, nel sembrare un pessimista di natura, cerca nei suoi personaggi la chiave per descrivere l’uomo che cade in piedi. Che non è semplice, perché se cadi il segno di un livido ti rimane, cadendo e rimanendo in piedi il dolore lo senti solo dentro. Non è fisico, è solo mentale. Alfonso Nitti, bancario che lascia la mamma e si ritrova in una città che non sembra appartenergli, a cui non vuole appartenere, il personaggio di Una vita ricalca l’archetipo del debole, di colui che si arrende all’amore perché non è amato dalla donna che vorrebbe, che si arrende alla perfezione e alla cura estetica del collega che lo snerva nel suo essere borghese e arrivista, si arrende alla distanza inevitabile del suo capo, il Maller. Solo la morte per quanto crudele e distante, riuscirà ad avvicinarlo alla perfezione della vita, ma questo nemmeno servirà ad sentire più vicini quelli che lui considerava mal volentieri “colleghi”."La Banca Maller, in puro stile burocratico, annuncia un funerale che avviene con l’intervento dei colleghi e della direzione" (Una vita). Alfonso, che si dà colpe non sue, scriverà alla mamma: “Non credere, mamma, che qui si stia tanto male; sono io che ci sto male”. Non faceva nulla e quel nulla lo portava ad avere un’inerzia totale dinnanzi alle cose. Non era stanco, era solo annoiato. Tutti i giorni lì su quella sedia, tutti i giorni a subire e non capire, tutti i giorni un pezzo di vita che si vedeva portar via, ma la cosa assurda è che mentre gli altri “sembravano” contenti di vivere così, Alfonso era contento di non vivere. Avrà ragione Joyce a dire che nella penna di un uomo c’è un solo romanzo e che quando se ne scrivono diversi si tratta sempre del medesimo più o meno trasformato. Così da Una Vita si passa alla Coscienza di Zeno, che nel 1924 Svevo spedisce al suo ormai amico Joyce, trasferitosi a Trieste e suo professore di inglese che Livia Veneziani Svevo descriverà così: “Fra il maestro, oltremodo irregolare, ma d’altissimo ingegno e lo scolaro d’eccezione le lezioni si svolgevano con un andamento fuori dal comune”. Joyce, entusiasta del suo “allievo”, fa conoscere il manoscritto in Francia dove verrà pubblicato. In Italia sarà per merito di Eugenio Montale, sulle pagine della rivista L’Esame, che Svevo riuscirà ad avere la prima notorietà. Zeno Cosini che cerca di guarire da una malattia non ancora ben definita ed inizia il percorso psicoanalitico presso il Dottor S. Dottore che, per quanto poco si sforzi di capire il problema, non riuscirà a farlo e nel momento dell’abbandono della terapia da parte di Zeno si vendicherà pubblicando le memorie del suo paziente con la speranza che questo gli procuri dolore. Ma Zeno, che è più impegnato ad amare la sua sigaretta non farà altro che ridere e deridere il suo analista. Stupida come cosa, ma immediatamente riuscii a capire il veleno che ti attraversa le vene, riuscii a capire quanto sia debole un uomo dinnanzi ad un vizio, che non ti serve, che non è utile, che è dannoso, ma diventa vitale. E più di tutto mi impressionò in Zeno il tentativo di voler smettere e la volontà certa di non farlo mai. Il medico della casa di cura dove venne “rinchiuso” per smettere di fumare gli dice:"Non capisco perché lei, invece di cessare di fumare, non si sia piuttosto risolto di diminuire il numero delle sigarette che fuma". Il non averci mai pensato di Zeno risulta l’immagine migliore del romanzo, il dolore che vivi dallo stacco brutale da un qualcosa a cui sei morbosamente legato ti ripaga dell’amore per cui morbosamente sei legato a quella cosa. Così o si rinuncia in maniera totale o non si rinuncia. Così Zeno passerà ogni sera ad annotare una U.S, un’ultima sigaretta mai spenta.

Stupida come cosa, ma immediatamente riuscii a capire il veleno che ti attraversa le vene, riuscii a capire quanto sia debole un uomo dinnanzi ad un vizio, che non ti serve, che non è utile, che è dannoso, ma diventa vitale. E più di tutto mi impressionò in Zeno il tentativo di voler smettere e la volontà certa di non farlo mai. Il medico della casa di cura dove venne “rinchiuso” per smettere di fumare gli dice:"Non capisco perché lei, invece di cessare di fumare, non si sia piuttosto risolto di diminuire il numero delle sigarette che fuma". Il non averci mai pensato di Zeno risulta l’immagine migliore del romanzo, il dolore che vivi dallo stacco brutale da un qualcosa a cui sei morbosamente legato ti ripaga dell’amore per cui morbosamente sei legato a quella cosa. Così o si rinuncia in maniera totale o non si rinuncia. Così Zeno passerà ogni sera ad annotare una U.S, un’ultima sigaretta mai spenta. Der 26. September 1996 war ein bedeutender Tag – auch wenn dies die Öffentlichkeit erst mehr als ein Jahr später erfahren sollte. An diesem Tag wurde Ernst Jünger in die katholische Kirche aufgenommen. Beim Gottesdienst zu diesem Anlaß wurde nach Jüngers Wunsch der Psalm 73 gebetet, in dem er die oft verschlungenen Pfade seines Lebens widergespiegelt sah:

Der 26. September 1996 war ein bedeutender Tag – auch wenn dies die Öffentlichkeit erst mehr als ein Jahr später erfahren sollte. An diesem Tag wurde Ernst Jünger in die katholische Kirche aufgenommen. Beim Gottesdienst zu diesem Anlaß wurde nach Jüngers Wunsch der Psalm 73 gebetet, in dem er die oft verschlungenen Pfade seines Lebens widergespiegelt sah:

Das 20. Jahrhundert bot geistigen Abenteurern Entfaltungsmöglichkeiten, von denen wir Heutige angesichts einer »verwalteten Welt« nur träumen können. Eine dieser abenteuerlichen Biographien des letzten Jahrhunderts hatte der italienische Dichter, Krieger und Nationalist Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863–1938). Beeinflußt von der Lebensphilosophie Friedrich Nietzsches, eroberte er nach Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs handstreichartig die Adriastadt Fiume und errichtete eine nationalistische Herrschaft des totalen Lebens.

Das 20. Jahrhundert bot geistigen Abenteurern Entfaltungsmöglichkeiten, von denen wir Heutige angesichts einer »verwalteten Welt« nur träumen können. Eine dieser abenteuerlichen Biographien des letzten Jahrhunderts hatte der italienische Dichter, Krieger und Nationalist Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863–1938). Beeinflußt von der Lebensphilosophie Friedrich Nietzsches, eroberte er nach Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs handstreichartig die Adriastadt Fiume und errichtete eine nationalistische Herrschaft des totalen Lebens.

Écrit vers 1636 par un jésuite espagnol, Baltasar GRACIÁN, l’ouvrage « LE HÉROS » (1), petit opuscule de 104 pages, nous enseigne comment devenir un personnage hors du commun, non pas en trompant son entourage, contrairement à l’enseignement de MACHIAVEL, mais en combattant ses penchants.

Écrit vers 1636 par un jésuite espagnol, Baltasar GRACIÁN, l’ouvrage « LE HÉROS » (1), petit opuscule de 104 pages, nous enseigne comment devenir un personnage hors du commun, non pas en trompant son entourage, contrairement à l’enseignement de MACHIAVEL, mais en combattant ses penchants.  Dans sa préface, Catherine VASSEUR nous donne une clef pour comprendre la problématique de Baltasar GRACIÁN :

Dans sa préface, Catherine VASSEUR nous donne une clef pour comprendre la problématique de Baltasar GRACIÁN :

La genèse de l’œuvre et de la pensée politique de Soljénitsyne doit donc être recherchée dans les discussions entre prisonniers à la Sharashka, dans la « Prison spéciale n°16 », où étaient confinés des intellectuels, contraints de travailler pour l’armée ou pour l’Etat. Soljénitsyne purgera donc in extenso les huit années de détention auxquelles il avait été condamné en 1945, immédiatement après son arrestation sur le front, en Prusse Orientale. Il ne sera libéré qu’en 1953. De 1953 à 1957, il vivra en exil, banni, à Kok-Terek au Kazakhstan, où il exercera la modeste profession d’instituteur de village. Il rédige « Le Pavillon des cancéreux », suite à un séjour dans un sanatorium. Réhabilité en 1957, il se fixe à Riazan. Son besoin de solitude demeure son trait de caractère le plus spécifique, le plus étalé dans la durée. Il s’isole et se retire dans des cabanes en forêt.

La genèse de l’œuvre et de la pensée politique de Soljénitsyne doit donc être recherchée dans les discussions entre prisonniers à la Sharashka, dans la « Prison spéciale n°16 », où étaient confinés des intellectuels, contraints de travailler pour l’armée ou pour l’Etat. Soljénitsyne purgera donc in extenso les huit années de détention auxquelles il avait été condamné en 1945, immédiatement après son arrestation sur le front, en Prusse Orientale. Il ne sera libéré qu’en 1953. De 1953 à 1957, il vivra en exil, banni, à Kok-Terek au Kazakhstan, où il exercera la modeste profession d’instituteur de village. Il rédige « Le Pavillon des cancéreux », suite à un séjour dans un sanatorium. Réhabilité en 1957, il se fixe à Riazan. Son besoin de solitude demeure son trait de caractère le plus spécifique, le plus étalé dans la durée. Il s’isole et se retire dans des cabanes en forêt.  Le 28 octobre 1994, lors de son discours à la Douma d’Etat, Soljénitsyne a répété la quintessence de ce qu’il avait écrit dans « Comment réaménager notre Russie ? ». Dans ce discours d’octobre 1994, Soljénitsyne dénonce en plus le régime d’Eltsine, qui n’a pas répondu aux espoirs qu’il avait éveillés quelques années plus tôt. Au régime soviétique ne s’est pas substitué un régime inspiré des meilleures pages de l’histoire russe mais une pâle copie des pires travers du libéralisme de type occidental qui a précipité la majorité du peuple dans la misère et favorisé une petite clique corrompue d’oligarques vite devenus milliardaires en dollars américains. Le régime eltsinien, parce qu’il affaiblit l’Etat et ruine le peuple, représente par conséquent une nouvelle « smuta ». Soljénitsyne, à la tribune de la Douma, a répété son hostilité au panslavisme, auquel il faut préférer une union des Slaves de l’Est (Biélorusses, Grands Russiens et Ukrainiens). Il a également fustigé la partitocratie qui « transforme le peuple non pas en sujet souverain de la politique mais en un matériau passif à traiter seulement lors des campagnes électorales ». De véritables élections, capables de susciter et de consolider une « démocratie qualitative », doivent se faire sur base locale et régionale, afin que soit brisée l’hégémonie nationale/fédérale des partis qui entendent tout régenter depuis la capitale. Les concepts politiques véritablement russes ne peuvent éclore qu’aux dimensions réduites des régions russes, fort différentes les unes des autres, et non pas au départ de centrales moscovites ou pétersbourgeoises, forcément ignorantes des problèmes qui affectent les régions.

Le 28 octobre 1994, lors de son discours à la Douma d’Etat, Soljénitsyne a répété la quintessence de ce qu’il avait écrit dans « Comment réaménager notre Russie ? ». Dans ce discours d’octobre 1994, Soljénitsyne dénonce en plus le régime d’Eltsine, qui n’a pas répondu aux espoirs qu’il avait éveillés quelques années plus tôt. Au régime soviétique ne s’est pas substitué un régime inspiré des meilleures pages de l’histoire russe mais une pâle copie des pires travers du libéralisme de type occidental qui a précipité la majorité du peuple dans la misère et favorisé une petite clique corrompue d’oligarques vite devenus milliardaires en dollars américains. Le régime eltsinien, parce qu’il affaiblit l’Etat et ruine le peuple, représente par conséquent une nouvelle « smuta ». Soljénitsyne, à la tribune de la Douma, a répété son hostilité au panslavisme, auquel il faut préférer une union des Slaves de l’Est (Biélorusses, Grands Russiens et Ukrainiens). Il a également fustigé la partitocratie qui « transforme le peuple non pas en sujet souverain de la politique mais en un matériau passif à traiter seulement lors des campagnes électorales ». De véritables élections, capables de susciter et de consolider une « démocratie qualitative », doivent se faire sur base locale et régionale, afin que soit brisée l’hégémonie nationale/fédérale des partis qui entendent tout régenter depuis la capitale. Les concepts politiques véritablement russes ne peuvent éclore qu’aux dimensions réduites des régions russes, fort différentes les unes des autres, et non pas au départ de centrales moscovites ou pétersbourgeoises, forcément ignorantes des problèmes qui affectent les régions.

Dicevamo della lucidità, della “scientificità”della poetica del Nostro: ebbene, coloro che si son presi la briga di riportare sulla carta geografica la rotta della nave di Gordon Pym attraverso gli oceani, hanno avuto una sorpresa: congiungendone i punti, appariva nettamente la sagoma di un grande uccello con le ali spiegate – come i misteriosi uccelli bianchi che gridano il loro incessante Tekeli-li. Un caso, una semplice coincidenza? Ma Poe amava moltissimo i giochi di decrittazione, gli enigmi logici e linguistici: sempre nel