vendredi, 09 novembre 2012

La légende d’Ulenspiegel

Les classiques de la culture européenne

La légende d’Ulenspiegel

par Jean-Joël BREGEON

Ce qui est mémorable est « digne d’être conservé dans les mémoires des hommes » dit Le Robert. Celle des Français, en ce début de siècle, semble de plus en plus courte. Dans le seul domaine littéraire, des auteurs tenus pour majeurs par des générations de lecteurs sont tout simplement tombés aux oubliettes. Pas seulement des écrivains anciens, de l’Antiquité, du Moyen Age, de la Renaissance ou des Temps modernes mais aussi des auteurs proches de nous, disparus au cours du XXème siècle.

Cette suite de recensions se propose de remettre en lumière des textes dont tout « honnête homme » ne peut se dispenser. Ces choix sont subjectifs et je les justifie par le seul fait d’avoir lu et souvent relu ces livres et d’en être sorti enthousiaste. Ils seront proposés dans le désordre, aussi bien chronologique que spatial, de manière délibérée. A vous de réagir, d’aller voir et d’être conquis ou critique. En tout cas, bonne lecture !

Charles de Coster. La légende d’Ulenspiegel au pays de Flandre et ailleurs.

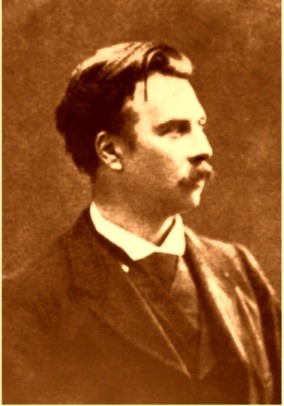

L’auteur d’abord : Charles de Coster. Il naît en 1827, d’un père yprois (Ypres) et d’une mère liégeoise. Des parents catholiques et tout fraîchement belges (le royaume vient d’être fondé, en 1830). De Coster va mener une vie contrariée, dans ses amours comme dans sa vie professionnelle. Formé par les jésuites, étudiant en droit et en lettres, contraint de travailler dans la banque puis d’enseigner à l’Ecole militaire de Bruxelles, il passe trop de temps à l’écart de ses passions, l’histoire, les lettres anciennes. Bel homme, altier, il n’est pas pris au sérieux sauf auprès d’une bande de bruxellois non-conformistes et bons vivants,la Société des Joyeux, fondée en 1847. Beaucoup de tintamarre chez ces étudiants prolongés qui ont en commun la détestation du parisianisme et du conformisme sulpicien, ultramontain, de la classe dirigeante belge.

L’auteur d’abord : Charles de Coster. Il naît en 1827, d’un père yprois (Ypres) et d’une mère liégeoise. Des parents catholiques et tout fraîchement belges (le royaume vient d’être fondé, en 1830). De Coster va mener une vie contrariée, dans ses amours comme dans sa vie professionnelle. Formé par les jésuites, étudiant en droit et en lettres, contraint de travailler dans la banque puis d’enseigner à l’Ecole militaire de Bruxelles, il passe trop de temps à l’écart de ses passions, l’histoire, les lettres anciennes. Bel homme, altier, il n’est pas pris au sérieux sauf auprès d’une bande de bruxellois non-conformistes et bons vivants,la Société des Joyeux, fondée en 1847. Beaucoup de tintamarre chez ces étudiants prolongés qui ont en commun la détestation du parisianisme et du conformisme sulpicien, ultramontain, de la classe dirigeante belge.

De Coster a des peines de cœur – une muse qu’il ne peut séduire – et il s’épanche dans des poèmes plutôt mièvres. Puis il se met à adapter des légendes flamandes et des contes brabançons, dans une écriture un peu trop chantournée, très « troubadour ». La bonne inspiration lui vient tard lorsqu’il se trouve attelé à un travail d’archiviste qui le met en contact direct avec l’histoire dela Flandre. Il s’empare alors d’une légende un peu oubliée qui circule en plusieurs versions imprimées et traduite en français sous le titre : Histoire joyeuse et récréative de Till Ulespiegel (1559). La légende a déambulé dans toute l’Europe du Nord. Elle part d’un personnage réel, un paysan du Schleswig-Holstein qui vivait au début du XIVème siècle. Il se serait fait connaître par ses plaisanteries, ses farces touchant les bourgeois et les modes de vie citadins. Compilées, adaptées, déformées, rendues plus littéraires, les soties de Thyl Ulenspiegel (en néerlandais) parviennent jusqu’à De Coster qui les transfigure littéralement.

Il les recompose dans un français qui puise dans le terreau de la langue, du côté de Rabelais et de Montaigne. Au-delà de cette recréation langagière, truculente mais aussi savante et raffinée (la même démarche que celle de Louis-Ferdinand Céline), qui porte son récit, De Coster créé une épopée nationale, alliance de l’Iliade et de l’Odyssée, à la gloire d’une Flandre, frondeuse et joyeuse même dans les pires tourments. Son Thyl Ulenspiegel est comme un lutin, un peu donquichottesque mais aussi homme libre, de fidélité, vrai paladin des libertés flamandes. Son compagnon, Lamme Goedzak est plutôt un Sancho Panca, mais sans la charge du personnage de Cervantès, moins niais, moins couard, porteur de la sagesse populaire.

Le nom du héros est « la conjonction de « Uyl », hibou, et de « Spiegel », miroir, qui désigne autant l’œil rond, toujours en éveil, de l’oiseau de nuit qui voit tout, que le miroir interne où se reflètent la turbulence et le fracas du monde extérieur » (P. Roegiers). Il est bien Thyl l’Espiègle et le mot français vient tout droit de lui, bouffon, badin, un peu fripon, toujours malin.

La légende d’Ulenspiegel est articulée en cinq livres. Tout part de Damme, l’avant port de Bruges :« A Damme, en Flandre, quand Mai ouvrait leurs fleurs aux aubépines, naquit Ulenspiegel, fils de Claers. » L’atmosphère de kermesse, directement inspirée des peintures bruegéliennes tourne court avec l’irruption des Espagnols décidés à maintenirla Flandre dans le giron de l’Eglise catholique et romaine et donc à extirper l’hérésie. Thyl perd son père, brûlé vif sous l’accusation de propos hérétiques. C’est en sa mémoire qu’il parcourtla Flandre et le Brabant, traqué par les « happe-chair » du terrible duc d’Albe. Il soulève les villes, accomplit des missions secrètes, entre dans des « bandes » pour faire la guerre aux Espagnols :

« Partant de Quesnoy-le-Comte pour aller vers le Cambrésis, il rencontra dix compagnies d’Allemands, huit enseignes d’Espagnols et trois cornettes de chevau-légers, commandées par don Ruffele Henricis, fils du duc, qui était au milieu de la bataille et criait en espagnol :

- Tue ! tue ! Pas de quartier ! Vive le Pape !… Ulenspiegel dit au sergent de bande :

- Je vais couper la langue à ce bourreau.

- Coupe, dit le sergent.

- Et Ulenspiegel, d’une balle bien tirée, mit en morceaux la langue et la mâchoire de don Ruffele Henricis, fils du duc. »

Philippe II, roi d’Espagne, est montré enfermé dans son palais-monastère de l’Escorial, ranci de bigoteries, jouissant de ses bas instincts. Le portrait est charge tout comme celui du clergé qui se nourrit de la superstition des humbles et les maintient dans la terreur de l’Enfer. Thyl veut vivre libre et jouir des plaisirs de la vie. Mais il a aussi la fidélité dans le sang. Son astuce lui donne mille idées pour venger veuves et orphelins et démasquer les traitres. Il est Achille mais aussi Ulysse car, à Damme, l’attend la tendre Nele, une autre Pénélope.

Mais la chair est faible et Ulenspiegel succombe lorsqu’il croise des filles bien délurées. A cette « fille rougissante » qui veut bien mais se méfie un peu : « Pourquoi m’aimes-tu si vite ? Quel métier fais-tu ? Es-tu gueux, es-tu riche ? »

Il lui répond sans détour : « Je suis Gueux, je veux voir morts et mangés des vers les oppresseurs des Pays-Bas. Tu me regardes ahurie. Ce feu d’amour qui brûle pour toi, mignonne, est feu de jeunesse. Dieu l’alluma, il flambe comme luit le soleil, jusqu’à ce qu’il s’éteigne. Mais le feu de vengeance qui couve en mon cœur, Dieu l’alluma pareillement. Il sera le glaive, le feu, la corde, l’incendie, la dévastation, la guerre et la ruine des bourreaux. »

Au cabaret, il mène le chœur, c’est la chanson des Gueux :

« Que le duc soit enfermé vivant avec les cadavres des victimes ! Que dans la puanteur, Il meure de la peste des morts !

Battez le tambour de guerre. Vive le Gueux !Et tous de boire et de crier : – Vive le Gueux !

Et Ulenspiegel, buvant dans le hanap doré d’un moine regardait avec fierté les faces vaillantes des Gueux Sauvages. »

Pour Charles de Coster, la réception de son épopée par le milieu littéraire fut un désastre. A Paris et à Bruxelles on parla de récit sans queue ni tête, d’un « ingénieux rapiéçage d’anecdotes » et on réclama une traduction en « vrai français ». De Coster ne s’en remit pas. Il mourut à 52 ans, couvert de dettes, dans une mansarde, au 114 rue de l’Arbre Bénit à Bruxelles où allait naître 19 ans plus tard un autre iconoclaste des lettres belges : Michel de Ghelderode.

La gloire fut posthume, au début du XXème siècle et universelle. Grâce notamment à Verhaeren, on découvrit que De Coster avait écrit la « Bible flamande », un chef-d’œuvre traduit dans une dizaine de langues. En 1956, Gérard Philippe produisit le film Till l’espiègle qu’il tourna dans les studios de Berlin-Est, dans le plus pur réalisme socialiste. Ce fut un échec. L’œuvre de Charles De Coster avait été mieux servie par Richard Strauss qui en avait tiré un poème symphonique (Opus 28, 1894).

Devenue l’épopée nationale flamande,La Légended’Ulenspiegel prend aujourd’hui une singulière saveur. N’est-elle pas écrite par un Belge francophone, à la gloire de la partie néerlandophone de cette Belgique inventée par les cours d’Europe, il y a 182 ans ? Tout cela laisse augurer d’une partition à l’amiable, en bon voisinage, des deux entités belges. Au grand dam des eurocrates et pour la plus grande joie de Charles De Coster, l’Espiègle.

Jean-Joël Bregeon pour NOVOpress Breizh

* Charles de Coster – La Légende et les aventures héroïques, joyeuses et glorieuses d’Ulenspiegel et de Lamme Goedzak au pays de Flandres et ailleurs, Minos/La Différence, Paris, 2003.

00:07 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : légende, tyl uilenspiegel, charles de coster, belgique, belgicana, littérature, lettres, lettres belges, littérature belge, flandre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 07 novembre 2012

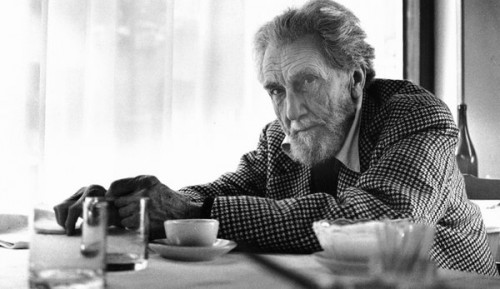

Ezra Pound: Protector of the West

Ezra Pound: Protector of the West

By Ursus Major

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Ezra Pound was arguably the finest American-born poet and a first rate Classical scholar. He happened to be born in Idaho, a state not noted for either its poets or Classicists. It was, however, a center of the American Populist Movement, which pitted the (usually family) farmer against the banks and railroads. The Populists called themselves “National-Socialists,” long before that term was heard in Europe.

Pound was born in 1885, making him less than two-years younger than his later hero, Benito Mussolini. This was at the apex of the Populist movement. The Populist Party’s platform for the 1886 election was almost entirely written by Edward Bellamy. Bellamy was a novelist-journalist, whose utopian work, Looking Backward had sold over 1 million copies in the U.S. alone.

Looking Backward is set in the year 2000, and recounts the victory of National-Socialism: the nationalization of the banks and railroads, along with a host of reforms to alleviate the lot of the working-man without invoking Marxism. The syndicalism of Georges Sorel was a major influence upon the Populists, as it was upon the one-time Socialist, Benito Mussolini.

(Mussolini had been named “Benito,” which is not an Italian name, by his anarchist father, in honor of Benito Juárez, the Mexican revolutionary responsible for the execution of Maximilian. Actually, Juárez didn’t last that long: he was disposed of by his lieutenant Díaz, who proceeded to set up a dictatorship, which was 100-times more repressive than anything envisioned by the liberal Austrian Arch-Duke, who had been tricked by Napoleon III into accepting a “crown,” which was created by the French, the Catholic Church, and the Mexican latifundiastas: huge landowners. One should remember that the Spanish Habsburgs had ruled Mexico for centuries. The Habsburg arms — the Roman Double Eagle — are to be found on the Governor’s House in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which was founded during the Habsburg era. So Maximilian, being offered the crown as Emperor of Mexico wasn’t off-the-wall.)

What happened with the Populists? Basically, William Jennings Bryan stole their rhetoric; and Theodore Roosevelt along with Taft gave support to the trade-union movement. Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech, in support of the free-silver movement, caused the Populists to support Bryan, and they shared in Bryan’s defeat. Imperialism was the impetus of the hour, as the U.S. attacked and defeated Spain, taking what remained of the Spanish Empire (and sending the Marines to the Philippines, to show them that it was merely a “change of title,” by shooting half-a-million of the “liberated”).

Oscar Wilde once commented, “When a good American dies, he goes to Paris.” Pound didn’t wait until he was dead before leaving the Land of the Free and Hopelessly Vulgar. By 1908, he was living in London. In 1920, he moved to Paris (which was less expensive); and in 1924, he moved to Italy, where he was to remain until the U.S. Army brought him back to the Land of the Victorious and Hopelessly Vulgar — in a cage! Pound was an ardent Fascist and remained one until the day of his death, well over 30 years after the Duce and his mistress, Clara Petacchi, were hung like sides of beef from the rafters of a bombed-out gas station in Milan.

Pound found in Fascist Italy both the “National-Socialism” of the Populists plus a reawakening of the “civilizing” mission of Ancient Rome, of which Pound (the Classicist) was so fond. Pound referred to his poems as “Cantos” — lyrics! — which drew upon the greatest Euro-poets, from Homer on, as their inspiration; and, in his Pisan Cantos (written while confined to a cage in Pisa after WWII, and for which he was awarded the 1949 Bollingen Prize in Poetry) incorporating inspiration from that other great High Culture: the Culture of Confusian China. What was Pound doing in a U.S. Army cage? Awaiting some decision by the U.S. government as to what to do with its most famous poet — who had regularly broadcast pro-Axis speeches from 1941 on!

In the Plutocratic-Marxist alliance of WWII, he found all he had despised since his youth: the joint determination of Bankers and Barbarians to destroy Western Civilization (which, in Pound’s view was personified in Fascist Italy, with Germany a distant second). His slim prose work Jefferson and/or Mussolini drew attention to Jefferson loathing of banks and compared the tyranny of International Finance with British Mercantilism, finding the former worse than the latter. His anti-Semitic speeches were directed solely against Jewish financial control. (Unlike most anti-Semites, he was rabid in his loathing of Jewish financial interests, but totally indifferent toward the Jews qua Jews and was quite disturbed when Mussolini sanctioned the deportation of Italian Jews, who were obviously not financiers.) He described Italian Fascism as “paternally authoritarian” and subscribed to the view that freedom was for those who’d earned it. He described the American concept of free speech as merely “license”: “Free speech, without radio free speech is zero!” was a comment he made in one of his own broadcasts.

Although manifestly guilty of treason under U.S. law, the government felt embarrassed at the prospect of trying him, so they had some medical hacks from the military certify he was insane, and committed him to St. Elizabeths, the federal asylum in Washington from 1946 until 1958, when he was allowed to leave, providing he immediately left the country. That he did, returning to Italy; his last act in the U.S. being to accord the Statue of Liberty the Roman/Fascist salute!

The first of the “Cantos” had appeared in 1917. The last (96-109: Thronos) in 1959. The Whole he considered one vast epic poem, on a Homeric scale; however, it is more an epic reflecting the maturity of an artist and Classicist, in an age which marked the decline of both. One can see in influence of Yeats (who was also markedly pro-Fascist, but died before that could produce a crisis [1939]), Ford Maddox Ford and James Joyce were “cross pollinators” with Pound. T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway [. . .] died before him; therefore, Ezra Pound became the last of the expatriate artists, a tradition that began with Henry James. Certainly some brief excerpt of his work is called for. The following is taken from one of the Pisan Cantos, written in the cage:

this breath wholly covers the mountains

it shines and divides

it nourishes by its rectitude

does no injury

overstanding the earth it fills the nine fields

to heaven

Boon companion to equity

it joins with the process

lacking it, there is inanition

When the equities are gathered together

as birds alighting

it springeth up vital

If deeds be not ensheaved and garnered in the heart

there is inanition.

I selected this example, because it draws upon the High Culture of China for inspiration, and incorporates within this a Classical maxim, which even those who know no Latin should be aware of. The final phrase (“if deeds be not ensheaved and garnered in the heart / there is inanition”) is a restatement of ACTA NON VERBA! (For those denied access to a dictionary of sufficient scope, “inanition” means “emptiness, a need – like a need for food or drink.”)

So Pound combines the essence of Mandarian art with the essence of the West, affirming the Spenglerian premise that all High Cultures are “transportable.” How many full-time Western symphony orchestras does Tokyo support? EIGHT! (Pound,by the way, was a excellent bassoonist.)

Leaving aside all other considerations, Ezra Pound — Poet and Traitor — PROVES the essential unity of all Euros. From Hailey, Idaho to London, Paris, Rapallo, Rome, an asylum in Washington, D.C. back to die in his beloved Rapallo (where the aging Gore Vidal now spends most of his time), Pound showed that no part of Magna Europa is alien to any Euro. Art, like an orchid, requires a special soil, a special climate to blossom in. A poet was born in the prairies of Idaho, but his genius could not thrive in the same soil as potatoes. Even as thousands of years before, the genius of Ovid atrophied in Tomis, where Augustus had banished him (Ovid had a great influence on Pound), so the genius of Ezra (what a horrid name!) Pound, Classicist, Poet-Supreme, would have atrophied in that backwater of Magna Europa. And so the Euro had to return to the primal soil, that his genius might bloom — yes, and be driven into treason, lest greed and barbarism destroy Magna Europa. “If this be treason, let us make the most of it!” Patrick Henry admonished his colleagues. Pound made as much of it as he could.

That what he saw as a deadly threat to his Race-Culture, he put ahead of the color of his passport may be heinous or not. That is not the issue. The issue is that Hailey, Idaho could give Magna Europa one of Her greatest poets, whose greatness ensued in the main from his ability to absorb all that had gone before and say it anew — even deploying adoptive forms!

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2012/10/ezra-pound-protector-of-the-west/

00:01 Publié dans Histoire, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, états-unis, ezra pound, poésie, littérature, littérature américaine, lettres, lettres américaines |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 01 novembre 2012

Citaat v. Hendrik Marsman

“Individualisme? Goed. Maar: dat werd niet met ‘80 geboren, dat werd in de Renaissance geboren. En zoolang u en ik en de heele wereld met ons over het cultuurprobleem spreken, bestaat de cultuur niet; en al is in velen de wil geboren naar een gemeenschap, maar de Gemeenschap, zij is er niet. En willens of onwillens is alle werk, nà de Moederkerkelijke cultuur der Middeleeuwen, individualistisch: heidensch of protestant. Zoolang de herleving van het Katholicisme, die wij nu beleven, niet zich cultureel (d.i. geestelijk en maatschappelijk) verwerkelijkt tot een katholieke samenleving, zoolang blijft de Katholieke kunst, malgré soi (min of meer) individualistisch. Pas als de naam verdwijnt, het teeken van het individu, zullen de gemeenschappelijk-voelenden, de Nameloozen, de nieuwe Kathedralen mogen bouwen.”

— Hendrik Marsman

(Bron: dbnl.org)

http://kali-jugend.tumblr.com/post/33709734248/levetscone-individualisme-goed-maar-dat

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie, Réflexions personnelles | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : hendrik marsman, lettres, lettres néerlandaises, littérature, littérature néerlandaise |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 27 octobre 2012

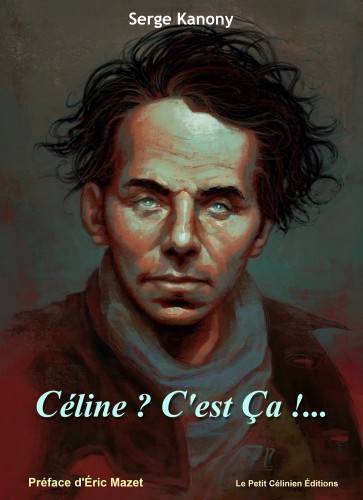

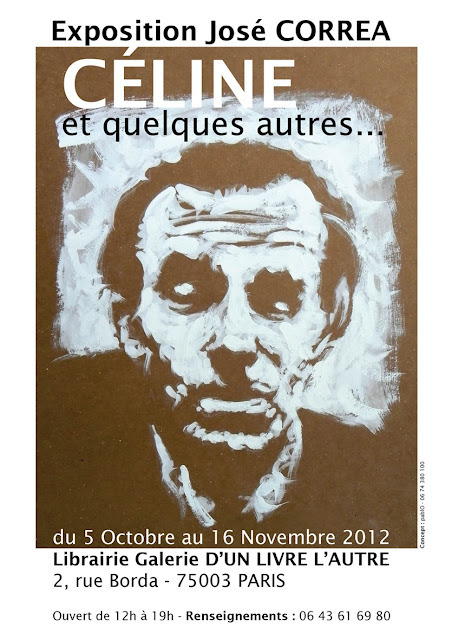

Céline ? C'est Ça !... de Serge KANONY

Céline ? C'est Ça !... de Serge KANONY

Et si on lisait Céline autrement ? Et si Céline renouait avec les grands mythes fondateurs de notre culture ? Et si la clé de cette œuvre, géniale et scandaleuse, se laissait entrevoir dans le monosyllabe par lequel s'ouvre son premier roman Voyage au bout de la nuit : « Ça a débuté comme ça. » ?

Le « Ça » célinien, c'est d'abord le Chaos originel, la Nuit primordiale des antiques cosmogonies, d'où surgissent tant l'œuvre que l'auteur ; c'est aussi deux guerres mondiales pleines de bruit et de fureur, où se déchaîne la folie meurtrière des hommes ; c'est encore une langue de rupture, chaotique, charriant le meilleur, mais aussi le pire : celui des éructations antisémites ; c'est enfin le « Ça » intérieur, la part maudite dont chacun est porteur.

Serge Kanony ouvre une porte que d'autres n'avaient fait qu'entrouvrir, derrière laquelle on entendait de drôles de cris. Serge Kanony ouvre la boîte de Pandore d'où s'échappent des ombres redoutables.

216 pages, format 14x21. Tirage limité sur papier bouffant. ISBN 978-2-7466-5216-3.

Illustration de couverture : Loïc Zimmermann.

- par chèque en nous retournant le BON DE COMMANDE

- par internet via les sites EBAY ou PRICEMINISTER

Les Entretiens du Petit Célinien (IX) : Serge KANONY

Quoi de plus moderne que Les Fleurs du mal ? Baudelaire y invente la poésie urbaine, celle des cheminées qui crachent leurs fumées, des fêtards sortant de boîte au petit matin, et la chanson de Jacques Dutronc Paris s’éveille n’est rien d’autre que la mise en musique du poème Le crépuscule du matin.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, livre, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, céline |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 26 octobre 2012

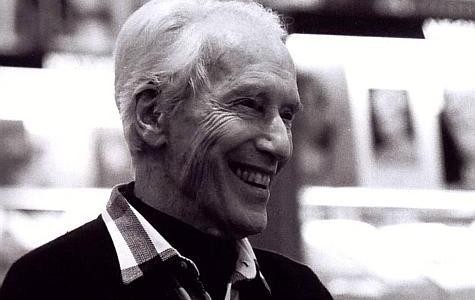

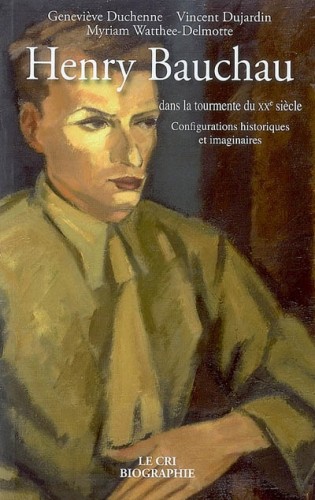

Hommage à Henry Bauchau

Robert Steuckers:

Hommage à Henry Bauchau

Version abrégée de: http://robertsteuckers.blogspot.be/2012/10/henry-bauchau-un-temoin-sen-est-alle.html/ ).

Dès le début des années 30, en août 1931 pour être exact, l’épiscopat et la direction cléricale de l’Université de Louvain, décident d’organiser un colloque où Léopold Levaux (disciple et exégète de Léon Bloy), le Recteur Magnifique Monseigneur Ladeuze, l’Abbé Jacques Leclercq (dont l’itinéraire intellectuel était parti des rénovateurs-modernisateurs du catholicisme, tels Jacques Maritain et Emmanuel Mounier, pour aboutir à une sorte de catho-communisme après 1945, avec l’apparition sur le théâtre de la politique belge d’un mouvement comme l’UDB qui restera éphémère) et... Léon Degrelle. On le voit: dès août 1931, le catholicisme belge va osciller entre diverses interprétations de son message éthique et social, entre “gauche” et “droite”, selon le principe de la “coïncidentia oppositorum” (chère à un Carl Schmitt en Allemagne). Dans le cadre de ces activités multiples, Bauchau se liera d’amitié à Raymond De Becker, celui que l’on nomme aujourd’hui, en le tirant de l’oubli, l’ “électron libre”, l’homme-orchestre qui, bouillonnant, va tenter de concilier toutes les innovations idéologiques, réclamant la justice sociale, qui émergeront dans les années 30. Quand De Man lance son idée planiste et critique le matérialisme outrancier des sociales-démocraties belge et allemande, De Becker, lié à Maritain et au mouvement “Esprit” de Mounier, cherchera à faire vivre une synthèse entre néo-socialisme (demaniste) et tradition catholique rénovée, où l’accent sera mis sur la mystique et l’ascèce plutôt que sur les bondieuseries superficielles et l’obéissance perinde ac cadaver du cléricalisme disciplinaire. Cet humaniste personnaliste, que fut De Becker, a cru que le bonheur arrivait enfin dans le royaume quand les catholiques ont formé une coalition avec les socialistes (où De Man était la figure de proue intellectuelle). Pour De Becker, et pour Bauchau dans son sillage, les éléments jeunes, qui cherchaient cette synthèse et voulaient jeter aux orties les scories du régime vieilli, aspiraient à un “ordre nouveau” (titre d’une brochure de De Becker dont la couverture a été illustrée par Hergé), un ordre qui ne serait pas une nouveauté radicale, respect des traditions morales oblige, mais une synthèse innovante qui unirait ce qu’il y a de meilleur dans les partis établis, débarrassés de leurs tares, héritage du “vieux monde” libéral, du “stupide 19ème siècle” selon Léon Daudet. Mais l’émergence du mouvement Rex de Degrelle déforce les catholiques dans le nouveau binôme politique formé avec les socialistes de Spaak et de De Man. L’Etat organique des forces jeunes, catholiques et néo-socialistes, n’advient donc pas. La guerre, plus que l’aventure rexiste, va briser la cohésion que ces milieux bouillonnants où De Becker jouait un rôle prépondérant. Disons-le une bonne fois pour toutes: c’est cette “déchirure” au sein des mouvements catholiques personnalistes et droitistes qui a envenimé définitivement la “question belge”, jusqu’à la crise de 2007-2011. Dans l’espace culturel flamand, la crise éthico-identitaire s’est déployée selon un autre rythme (plutôt plus lent) mais, inexorablement, avec les boulevedrsements dans les mentalités qu’a apporté mai 68, une mutation quasi anthropologique qui a notamment suscité les admonestations du nationaliste ex-expressionniste Wies Moens, alors professeur à Geelen dans le Limbourg néerlandais, le déclin éthique n’a pas pu être enrayé par un mouvement conservateur, “katéchonique”. Ni en Flandre ni a fortiori en Wallonie.

Avec la défaite de 1940, ce mouvement à facettes multiples va se disperser et, surtout, va être tiraillé entre l’“option belge” (la “politique de présence”), la collaboration, la résistance (royaliste) et l’engouement, dès les déboires de l’Axe en Afrique et en Russie, de certains anciens personnalistes (De Becker excepté) qui vireront au catho-communisme dès la fin de l’occupation allemande. Bauchau oscillera de l’option belge à la résistance royaliste (Armée Secrète). De Becker voudra une collaboration dans le cadre strict de la “politique de présence”. Degrelle jouera la carte collaborationniste à fond. Les adeptes de l’Abbé Leclercq opteront pour l’orientation personnaliste de Maritain et Mounier et chercheront un modus vivendi avec les forces de gauches, communistes compris.

Bauchau, dès le début de l’occupation, tentera de mettre sur pied un “Service du Travail Volontaire pour la Wallonie”, qui avait aussi un équivalent flamand. Ce Service devait aider à effacer du pays les traces de toutes les destructions laissées par la campagne des Dix-Huit Jours. Les Volontaires wallons aideront les populations sinistrées, notamment lors de l’explosion d’une usine chimique à Tessenderloo ou suite au bombardement américain du quartier de l’Avenue de la Couronne à Etterbeek. Il avait aussi pour ambition tacite de soustraire des jeunes gens au travail obligatoire en Allemagne. Les tiraillements d’avant juin 1940, entre catholiques personnalistes d’orientations diverses, favorables soit à Rex soit à un “Ordre Nouveau” à construire avec les jeunes catholiques et socialistes (demanistes), vont se répercuter dans la collaboration, première phase. De Becker refusera toute hégémonie rexiste sur la partie romane du pays. Il oeuvrera à l’émergence d’un “parti unique des provinces romanes”, qui ne recevra pas l’approbation de l’occupant et essuiera les moqueries (et les menaces) de Degrelle. La situation tendue de cette année 1942 nous est fort bien expliquée par l’historien britannique Martin Conway (in: Collaboration in Belgium, Léon Degrelle and the Rexist Movement, Yale University Press, 1993). La fin de non recevoir essuyée par De Becker et ses alliés de la collaboration à option belge et le blanc-seing accordé par l’occupant aux rexistes va provoquer la rupture. Bauchau avait certes marqué son adhésion à la constitution du “parti unique des provinces romanes”, mais le remplacement rapide des cadres de son SVTW par des militants rexistes entraîne sa démission et son glissement progressif vers la résistance royaliste. De Becker lui-même finira par démissionner, y compris de son poste de rédacteur en chef du “Soir”, arguant que les chances de l’Axe étaient désormais nulles depuis l’éviction de Mussolini par le Grand Conseil Fasciste pendant l’été 1943.

Bauchau participe aux combats de la résistance dans la région de Brumagne (près de Namur), y est blessé. Mais, malgré cet engagement, il doit rendre des comptes à l’auditorat militaire, pour sa participation au SVTW et surtout, probablement, pour avoir signé le manifeste de fondation du “parti unique (avorté) des provinces romanes”. Il échappe à tout jugement mais est rétrogradé: de Lieutenant, il passe sergeant. Il en est terriblement meurtri. Sa patrie, qu’il a toujours voulu servir, le dégoûte. Il s’installe à Paris dès 1946. Mais cet exil, bien que captivant sur le plan intellectuel puisque Bauchau est éditeur dans la capitale française, est néanmoins marqué par le désarroi: c’est une déchirure, un sentiment inaccepté de culpabilité, un tiraillement constant entre les sentiments paradoxaux (l’oxymore dit-on aujourd’hui) d’avoir fait son devoir en toute loyauté et d’avoir, malgré cela, été considéré comme un “traître”, voire, au mieux, comme un “demi-traître”, dont on se passera dorénavant des services, que l’on réduira au silence et à ne plus être qu’une sorte de citoyen de seconde zone, dont on ne reconnaîtra pas la valeur intrinsèque. A ce malaise tenace, Bauchau échappera en suivant un traitement psychanalytique chez Blanche Reverchon-Jouve. Celle-ci, d’inspiration jungienne, lui fera prendre conscience de sa personnalité vraie: sa vocation n’était pas de faire de la politique, de devenir un chef au sens où on l’entendait dans les années 30, mais d’écrire. Seules l’écriture et la poésie lui feront surmonter cette “déchirure”, qu’il lui faudra accepter et en laquelle, disait la psychanalyste française, il devra en permanence se situer pour produire son oeuvre: ce sont les sentiments de “déchirure” qui font l’excellence de l’écrivain et non pas les “certitudes” impavides de l’homme politisé.

Bauchau participe aux combats de la résistance dans la région de Brumagne (près de Namur), y est blessé. Mais, malgré cet engagement, il doit rendre des comptes à l’auditorat militaire, pour sa participation au SVTW et surtout, probablement, pour avoir signé le manifeste de fondation du “parti unique (avorté) des provinces romanes”. Il échappe à tout jugement mais est rétrogradé: de Lieutenant, il passe sergeant. Il en est terriblement meurtri. Sa patrie, qu’il a toujours voulu servir, le dégoûte. Il s’installe à Paris dès 1946. Mais cet exil, bien que captivant sur le plan intellectuel puisque Bauchau est éditeur dans la capitale française, est néanmoins marqué par le désarroi: c’est une déchirure, un sentiment inaccepté de culpabilité, un tiraillement constant entre les sentiments paradoxaux (l’oxymore dit-on aujourd’hui) d’avoir fait son devoir en toute loyauté et d’avoir, malgré cela, été considéré comme un “traître”, voire, au mieux, comme un “demi-traître”, dont on se passera dorénavant des services, que l’on réduira au silence et à ne plus être qu’une sorte de citoyen de seconde zone, dont on ne reconnaîtra pas la valeur intrinsèque. A ce malaise tenace, Bauchau échappera en suivant un traitement psychanalytique chez Blanche Reverchon-Jouve. Celle-ci, d’inspiration jungienne, lui fera prendre conscience de sa personnalité vraie: sa vocation n’était pas de faire de la politique, de devenir un chef au sens où on l’entendait dans les années 30, mais d’écrire. Seules l’écriture et la poésie lui feront surmonter cette “déchirure”, qu’il lui faudra accepter et en laquelle, disait la psychanalyste française, il devra en permanence se situer pour produire son oeuvre: ce sont les sentiments de “déchirure” qui font l’excellence de l’écrivain et non pas les “certitudes” impavides de l’homme politisé.

En 1951, après avoir oeuvré sans relâche à la libération de son ami Raymond De Becker, qu’il n’abandonnera jamais, Bauchau s’installe en Suisse à Gstaad où il crée un Institut, l’Institut Montesano, un collège pour jeunes filles (surtout américaines). Il y enseignera la littérature et l’histoire de l’art, comme il l’avait fait, avant-guerre, dans une “université” parallèle qui dispensait ses cours dans les locaux de l’Institut Saint-Louis de Bruxelles ou dans un local de la rue des Deux-Eglises à Saint-Josse et à laquelle participait également le philosophe liégeois Marcel De Corte. Son oeuvre littéraire ne démarrera qu’en 1958, avec la publication d’un premier recueil de poésie, intitulé Géologie. En 1972, sort un roman qui obtiendra le “Prix Franz Hellens” à Bruxelles et le “Prix d’honneur” à Paris. Ce roman a pour toile de fond la Guerre de Sécession aux Etats-Unis, période de l’histoire qui avait toujours fasciné son père, décédé en 1951. Dans son roman, Bauchau fait de son père un volontaire dans le camp nordiste qui prend la tête d’un régiment composé d’Afro-Américains cherchant l’émancipation.

En 1973, l’Institut Montesano ferme ses portes: la crise du dollar ne permettant plus aux familles américaines fortunées d’envoyer en Suisse des jeunes filles désirant s’immerger dans la culture européenne traditionnelle. A cette même époque, comme beaucoup d’anciennes figures de la droite à connotations personnalistes, Bauchau subit une tentation maoïste, une sorte de tropisme chinois (comme Hergé!) qui va bien au-delà des travestissements marxistes que prenait la Chine des années 50, 60 et 70. Notre auteur s’attèle alors à la rédaction d’une biographie du leader révolutionnaire chinois, Mao Tse-Toung, qu’il n’achèvera qu’en 1980, quand les engouements pour le “Grand Timonnier” n’étaient déjà plus qu’un souvenir (voire un objet de moquerie, comme dans les caricatures d’un humoriste flamboyant comme Lauzier).

En 1973, l’Institut Montesano ferme ses portes: la crise du dollar ne permettant plus aux familles américaines fortunées d’envoyer en Suisse des jeunes filles désirant s’immerger dans la culture européenne traditionnelle. A cette même époque, comme beaucoup d’anciennes figures de la droite à connotations personnalistes, Bauchau subit une tentation maoïste, une sorte de tropisme chinois (comme Hergé!) qui va bien au-delà des travestissements marxistes que prenait la Chine des années 50, 60 et 70. Notre auteur s’attèle alors à la rédaction d’une biographie du leader révolutionnaire chinois, Mao Tse-Toung, qu’il n’achèvera qu’en 1980, quand les engouements pour le “Grand Timonnier” n’étaient déjà plus qu’un souvenir (voire un objet de moquerie, comme dans les caricatures d’un humoriste flamboyant comme Lauzier).

Bauchau quitte la Suisse en 1975 et s’installe à Paris, comme psychothérapeute dans un hôpital pour adolescents en difficulté. Il enseigne à l’Université de Paris VII sur les rapports art/psychanalyse. En 1990, il publie Oedipe sur la route, roman situé dans l’antiquité grecque, axé sur la mythologie et donc aussi sur l’inconscient que les mythes recouvrent et que la psychanalyse jungienne cherche à percer. La publication de ce roman lui vaut une réhabilitation définitive en Belgique: il est élu à l’Académie Royale de Langue et de Littérature Française du royaume. Plus tard, son roman Antigone lui permet de s’immerger encore davantage dans notre héritage mythologique grec, source de notre psychè profonde, explication imagée de nos tourments ataviques.

Bauchau est également un mémorialiste de premier plan, que nous pourrions comparer à Ernst Jünger (qu’il cite assez souvent). Les journaux de Bauchau permettent effectivement de suivre à la trace le cheminement mental et intellectuel de l’auteur: en les lisant, on perçoit de plus en plus une immersion dans les mystiques médiévales —et il cite alors fort souvent Maître Eckart— et dans les sagesses de l’Orient, surtout chinois. On perçoit également en filigrane une lecture attentive de l’oeuvre de Martin Heidegger. Ce passage, à l’âge mûr, de la frénésie politique (politicienne?) à l’approfondissement mystique est un parallèle de plus à signaler entre le Wallon belge Bauchau et l’Allemand Jünger.

Bauchau est également un mémorialiste de premier plan, que nous pourrions comparer à Ernst Jünger (qu’il cite assez souvent). Les journaux de Bauchau permettent effectivement de suivre à la trace le cheminement mental et intellectuel de l’auteur: en les lisant, on perçoit de plus en plus une immersion dans les mystiques médiévales —et il cite alors fort souvent Maître Eckart— et dans les sagesses de l’Orient, surtout chinois. On perçoit également en filigrane une lecture attentive de l’oeuvre de Martin Heidegger. Ce passage, à l’âge mûr, de la frénésie politique (politicienne?) à l’approfondissement mystique est un parallèle de plus à signaler entre le Wallon belge Bauchau et l’Allemand Jünger.

L’an passé, Bauchau, à 98 ans, a sorti un recueil poignant de souvenirs, intitulé L’enfant rieur. Dans cet ouvrage, il nous replonge dans les années 30, avec l’histoire de son service militaire dans la cavalerie, avec les tribulations de son premier mariage (qui échouera) et surtout les souvenirs de “Raymond” qu’il n’abandonnera pas, sans oublier les mésaventures du mobilisé Bauchau lors de la campagne des Dix-Huit Jours. Bauchau promettait une suite à ces souvenirs de jeunesse, si la vie lui permettait encore de voir une seule fois tomber les feuilles... Il est mort le jour de l’équinoxe d’automne 2012. Il n’a pas vu les feuilles tomber, comme il le souhaitait, mais le manuscrit, même inachevé, sera sûrement confié à son éditeur, “Actes Sud”.

Bauchau n’est plus un “réprouvé”, comme il l’a longtemps pensé avec grande amertume. Un institut s’occupe de gérer son oeuvre à Louvain-la-Neuve. Les “Archives & Musée de la Littérature” de la Bibliothèque Royale recueille , sous la houlette de son exégète et traductrice allemande Anne Neuschäfer (université d’Aix-la-Chapelle), tous les documents qui le concerne (http://aml.cfwb.be/bauchau/html/ ). A Louvain-la-Neuve, Myriam Watthée-Delmotte se décarcasse sans arrêt pour faire connaître l’oeuvre dans son intégralité, sans occulter les années 30 ni l’effervescence intellecutelle et politique de ces années décisives.

Et en effet, il faudra immanquablement se replonger dans les vicissitudes de cette époque; le Prof. Jean Vanwelkenhuizen avait déjà sorti un livre admirable sur l’année 1936, montrant que les jugements à l’emporte-pièce sur la politique de neutralité, sur l’émergence du rexisme, sur la guerre d’Espagne et sur le Front Populaire français, n’étaient plus de mise. Cécile Vanderpelen-Diagre, dans Ecrire en Belgique sous le regard de Dieu, avait, à l’ULB, dressé un panorama général de l’univers intellectuel catholique de 1890 à 1945. Jean-François Fuëg (ULB), pour sa part, nous narre l’histoire du mouvement anarchisant autour de la revue et du cercle “Le Rouge et Noir” de Bruxelles, où l’on s’aperçoit que l’enthousiasme pour la politique de neutralité de Léopold III n’a pas été la marque d’une certaine droite conservatrice (autour de Robert Poulet) mais a eu des partisans à gauche. Enfin, Eva Schandevyl (VUB) nous dresse un portrait des gauches belges de 1918 à 1956, où elle ne fait nullement l’impasse sur le formidable espoir que les idées de De Man avait suscité dans les années 30. Mieux: les Facultés Universitaires Saint-Louis ont consacré en avril dernier un colloque à la mémoire de Raymond De Becker, initiative en rupture avec les poncifs dominants qui avait fait hurler de fureur un plumitif lié aux “rattachistes wallingants”.

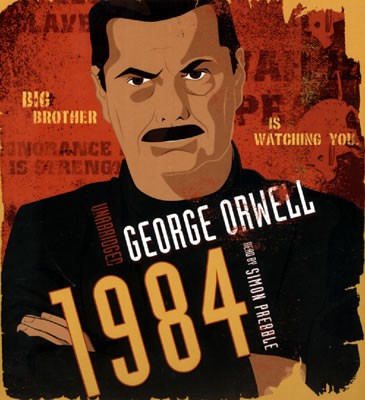

Le chantier est ouvert. Comprendre l’oeuvre de Bauchau, mais aussi la trajectoire post bellum de De Becker et d’Hergé, est impossible sans revenir aux sources, donc aux années 30. Mais un retour qui doit s’opérer sans les oeillères habituelles, sans les schématismes nés des hyper-simplifications staliniennes et libérales, pour lesquelles les actions etl es pensées du “zoon politikon” doivent se réduire à quelques slogans simplistes que Big Brother manipule et transforme au gré des circonstances.

Robert Steuckers.

(Forest-Flotzenberg, 26 octobre 2012).

22:48 Publié dans Belgicana, Hommages, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : belgique, belgicana, lettres, lettres belges, lettres françaises, littérature, littérature belge, littérature française, henry bauchau |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 21 octobre 2012

Vita e disavventure di Limonov

di Stenio Solinas

Fonte: il giornale [scheda fonte]

Capelli lunghi, papillon, una giacca a scacchi multicolori, le mani in tasca e lo sguardo fiero, il giovane modello fissa l'obiettivo. Ai suoi piedi, nuda e composta, la giovane modella fa lo stesso.

È il 1970 e Eduard Limonov e sua moglie Tanja, i due ragazzi della foto, sono quanto di meglio l'underground culturale dell'Urss brezneviana abbia da offrire, il vorrei ma non posso di un Oriente che scimmiotta l'Occidente, la sua caricatura involontaria e patetica e insieme la spia che qualcosa sta franando. I '70 sono gli anni dell'espulsione dei dissidenti, Siniavskij e Daniel, Solgenitsin e Brodskij, una prova di forza che sa di debolezza, così come l'intervento in Afghanistan che li chiude, un esercito che si ritiene invincibile e che conoscerà per la prima volta la sconfitta. L'Urss fa ancora paura, ma ha smesso di essere un esempio, non va più di moda: gerontocrazia al potere, regime asfittico, sistema che perde colpi. C'è chi se ne vuole andare e chi è costretto a partire. Limonov fa parte dei primi. Non è contro il regime, è a favore di sé stesso. Negli Usa e poi in Francia, contro tutto e tutti, vuole una vita esemplare che trionfi sull'anonimato. Ci riuscirà.Qualche anno prima, un'altra foto racconta un'altra storia, quella di un ventenne cekista: cappotto militare, mostrine, gradi. La miopia gli ha precluso il mestiere delle armi, ma già allora ha fiutato «che nel mondo gli intrecci fondamentali sono due, la guerra e la donna (la puttana e il soldato)». Molti anni dopo, una calibro 7,65 alla cintola, capelli a spazzola sotto la bustina, lo troveremo ritratto fra due miliziani serbi, una volto ancora infantile eppure ha cinquant'anni e ha appena fondato un partito, quello nazionalbolscevico: è il 1993. A 60, un'istantanea lo coglie dietro le sbarre, nella gabbia degli imputati: terrorismo, banda armata e istigazione all'attività sovversiva è l'accusa, falsa. Capelli lunghi ormai brizzolati, glaciali occhi azzurri dietro un paio d'occhiali dalla montatura spessa, baffi e pizzetto alla Trotskij, un altro suo modello. È già dentro da due anni, ne sconterà altri due. In carcere scrive otto libri, fra cui quello che per molti è il suo capolavoro, Il libro dell'acqua, del 2002.Eduard Limonov (pseudonimo di Eduard Sevenko: Limonov viene da limon, limone, per la sua acidità nella vita come nella scrittura, Livonka, granata, ovvero bomba a mano, sarà il titolo del giornale che poi lui fonderà) è un nome che in Italia non dice molto. È stato sì tradotto (da Alet Il libro dell'acqua, da Odradek Diario di un fallito, da Frassinelli Il poeta russo preferisce i grandi negri, da Salani Eddy-Baby ti amo), ma questa frantumazione editoriale non gli ha giovato e qualche cattiva traduzione ha fatto il resto. In Francia, dove è stato scoperto, è rimasto a lungo un autore di culto, prima che la sua scelta pro-serba al tempo della guerra dei Balcani ne facesse un «criminale di guerra», «lo scrittore con la pistola», addirittura il mitragliatore di passanti durante l'assedio di Sarajevo... Lui all'epoca rispose così: «Non sono un giornalista, sono un soldato. Un gruppo di intellettuali musulmani persegue con ferocia il sogno di instaurare qui uno Stato musulmano, e i serbi non ne vogliono sapere. Io sono un amico dei serbi e voi potete andare a fare in culo con la vostra neutralità che è sempre e soltanto vigliaccheria». Dimenticavo: in patria Limonov è uno scrittore famoso e un idolo per quei giovani che nella Russia di Putin non si riconoscono. Perché il nazionalbolscevico Limonov che disprezzava i dissidenti, ce l'aveva con Gorbaciov e Eltsin colpevoli di aver distrutto una nazione, è andato a schiantarsi anche contro Putin, l'uomo che a giudizio di molti ha ridato alla Russia l'orgoglio perduto, il campione di un nuovo nazionalismo. E anche questo è un ulteriore tassello di una vita contraddittoria quanto straordinaria.Adesso Emmanuel Carrère prova a rimetterne insieme i pezzi in questo Limonov (Adelphi, pagg. 356, euro 19) che è sì una biografia ma anche un interrogarsi sulla funzione e il ruolo degli intellettuali d'Occidente, sempre pronti ad applaudire la diversità, l'eccesso, l'anticonformismo, purché politicamente corretto, sempre attenti a non sporcarsi le mani, sempre convinti di poter dire la loro su tutto, specie su ciò che non conoscono, ma sempre legando questa convinzione alla moda politica e/o ideologica del giorno, subito dimenticata in favore di quella che il giorno dopo ne prenderà il posto. Manifesti, petizioni, dibattiti infiammati, poi si torna a casa al caldo, si cena, si fa, se si può, l'amore e si va a dormire. Domani è comunque un altro giorno.Figlio di Hélène Carrère d'Encausse, la slavista che nel suo Esplosione d'un impero aveva prefigurato per l'Urss, alla fine degli anni Settanta, quello che una dozzina d'anni dopo sarebbe successo, Emmanuel Carrère ha in teoria gli strumenti culturali giusti per entrare nel complesso mondo di Limonov, il suo cosiddetto «pensiero fascista», aggettivo che di per sé è già una condanna... Ha avuto una giovinezza intellettuale a destra, nel senso delle letture e delle predisposizioni familiari, ne conosce gli autori, in specie quelli francesi, i concetti di decadenza e di tradizione, gli elementi mitici e simbolici. Solo che Limonov non è Drieu La Rochelle o Evola, Céline o Maurras... È qualcosa di diversamente russo, panlavista e futurista, Nietzsche più Dostoevskij, Necaev più d'Annunzio, Alessandro il Grande e Che Guevara...La diversità è ancora più evidente se si esamina la sua creatura politica. I suoi «nazbol», i nazionalbolscevichi dalla testa rasata e dalla bandiera che ricorda quella nazista, con la falce e martello però al posto della croce uncinata, erano per Anna Politkovskaja, la celebre giornalista che pagò il suo coraggio investigativo con la morte, la faccia pulita della Russia anti-Putin, e lo stesso per Elena Bonner, la vedova di Sacha. Le loro armi eversive sono pomodori, uova marce e torte in faccia, le loro manifestazioni una via di mezzo fra goliardia e riproposizione delle avanguardie storiche. È gente che rischia la galera, quella russa, per appendere uno striscione vietato o per protestare contro la discriminazione della minoranza russa in Estonia... Sono militanti che si ritrovano in un credo limonoviano che suona così: «Sei giovane, non ti piace vivere in questo Paese di merda. Non vuoi diventare un anonimo compagno Popov, né un figlio di puttana che pensa soltanto al denaro, né un cekista. Sei uno spirito ribelle. I tuoi eroi sono Jim Morrison, Lenin, Mishima, Baader. Ecco: sei già un nazbol».Carrère coglie bene un punto del percorso politico-esistenziale di Limonov: «Bisogna dare atto di una cosa a questo fascista: gli piacciono e gli sono sempre piaciuti soltanto quelli che sono in posizione di inferiorità. I magri contro i grassi, i poveri contro i ricchi, le carogne dichiarate, che sono rare, contro le legioni di virtuosi, e il suo percorso, per quanto ondivago possa sembrare, ha una sua coerenza, perché Eduard si è schierato sempre, senza eccezione, dalla loro parte». È proprio questo a separarlo da Putin, che a Carrère sembra invece un Limonov che ce l'ha fatta, perché ha vinto, perché ha il potere. Limonov non vuole il potere per il potere, non sa che farsene. «Sì, ho deciso di schierarmi con il male, con i giornali da strapazzo, con i volantini ciclostilati, con i movimenti e i partiti che non hanno nessuna possibilità di farcela. Nessuna. Mi piacciono i comizi frequentati da quattro gatti, la musica cacofonica di musicisti senza talento...». La sua è un'estetica della politica, ha più a che fare con la comunità d'appartenenza, la fedeltà a uno stile, a delle amicizie, al senso dell'onore, che con una logica di conquista. Ricerca un eroismo e una purezza di comportamenti che lo allontanano mille miglia dalla Russia putiniana, troppo volgare, troppo borghesemente occidentale ai suoi occhi, troppo grassa nella sua ricerca del benessere. Resta un outsider Limonov, ma non un perdente, visto che vive la vita che ha sempre voluto vivere. Un orgoglioso re senza regno e uno scrittore che vale la pena leggere.

È il 1970 e Eduard Limonov e sua moglie Tanja, i due ragazzi della foto, sono quanto di meglio l'underground culturale dell'Urss brezneviana abbia da offrire, il vorrei ma non posso di un Oriente che scimmiotta l'Occidente, la sua caricatura involontaria e patetica e insieme la spia che qualcosa sta franando. I '70 sono gli anni dell'espulsione dei dissidenti, Siniavskij e Daniel, Solgenitsin e Brodskij, una prova di forza che sa di debolezza, così come l'intervento in Afghanistan che li chiude, un esercito che si ritiene invincibile e che conoscerà per la prima volta la sconfitta. L'Urss fa ancora paura, ma ha smesso di essere un esempio, non va più di moda: gerontocrazia al potere, regime asfittico, sistema che perde colpi. C'è chi se ne vuole andare e chi è costretto a partire. Limonov fa parte dei primi. Non è contro il regime, è a favore di sé stesso. Negli Usa e poi in Francia, contro tutto e tutti, vuole una vita esemplare che trionfi sull'anonimato. Ci riuscirà.Qualche anno prima, un'altra foto racconta un'altra storia, quella di un ventenne cekista: cappotto militare, mostrine, gradi. La miopia gli ha precluso il mestiere delle armi, ma già allora ha fiutato «che nel mondo gli intrecci fondamentali sono due, la guerra e la donna (la puttana e il soldato)». Molti anni dopo, una calibro 7,65 alla cintola, capelli a spazzola sotto la bustina, lo troveremo ritratto fra due miliziani serbi, una volto ancora infantile eppure ha cinquant'anni e ha appena fondato un partito, quello nazionalbolscevico: è il 1993. A 60, un'istantanea lo coglie dietro le sbarre, nella gabbia degli imputati: terrorismo, banda armata e istigazione all'attività sovversiva è l'accusa, falsa. Capelli lunghi ormai brizzolati, glaciali occhi azzurri dietro un paio d'occhiali dalla montatura spessa, baffi e pizzetto alla Trotskij, un altro suo modello. È già dentro da due anni, ne sconterà altri due. In carcere scrive otto libri, fra cui quello che per molti è il suo capolavoro, Il libro dell'acqua, del 2002.Eduard Limonov (pseudonimo di Eduard Sevenko: Limonov viene da limon, limone, per la sua acidità nella vita come nella scrittura, Livonka, granata, ovvero bomba a mano, sarà il titolo del giornale che poi lui fonderà) è un nome che in Italia non dice molto. È stato sì tradotto (da Alet Il libro dell'acqua, da Odradek Diario di un fallito, da Frassinelli Il poeta russo preferisce i grandi negri, da Salani Eddy-Baby ti amo), ma questa frantumazione editoriale non gli ha giovato e qualche cattiva traduzione ha fatto il resto. In Francia, dove è stato scoperto, è rimasto a lungo un autore di culto, prima che la sua scelta pro-serba al tempo della guerra dei Balcani ne facesse un «criminale di guerra», «lo scrittore con la pistola», addirittura il mitragliatore di passanti durante l'assedio di Sarajevo... Lui all'epoca rispose così: «Non sono un giornalista, sono un soldato. Un gruppo di intellettuali musulmani persegue con ferocia il sogno di instaurare qui uno Stato musulmano, e i serbi non ne vogliono sapere. Io sono un amico dei serbi e voi potete andare a fare in culo con la vostra neutralità che è sempre e soltanto vigliaccheria». Dimenticavo: in patria Limonov è uno scrittore famoso e un idolo per quei giovani che nella Russia di Putin non si riconoscono. Perché il nazionalbolscevico Limonov che disprezzava i dissidenti, ce l'aveva con Gorbaciov e Eltsin colpevoli di aver distrutto una nazione, è andato a schiantarsi anche contro Putin, l'uomo che a giudizio di molti ha ridato alla Russia l'orgoglio perduto, il campione di un nuovo nazionalismo. E anche questo è un ulteriore tassello di una vita contraddittoria quanto straordinaria.Adesso Emmanuel Carrère prova a rimetterne insieme i pezzi in questo Limonov (Adelphi, pagg. 356, euro 19) che è sì una biografia ma anche un interrogarsi sulla funzione e il ruolo degli intellettuali d'Occidente, sempre pronti ad applaudire la diversità, l'eccesso, l'anticonformismo, purché politicamente corretto, sempre attenti a non sporcarsi le mani, sempre convinti di poter dire la loro su tutto, specie su ciò che non conoscono, ma sempre legando questa convinzione alla moda politica e/o ideologica del giorno, subito dimenticata in favore di quella che il giorno dopo ne prenderà il posto. Manifesti, petizioni, dibattiti infiammati, poi si torna a casa al caldo, si cena, si fa, se si può, l'amore e si va a dormire. Domani è comunque un altro giorno.Figlio di Hélène Carrère d'Encausse, la slavista che nel suo Esplosione d'un impero aveva prefigurato per l'Urss, alla fine degli anni Settanta, quello che una dozzina d'anni dopo sarebbe successo, Emmanuel Carrère ha in teoria gli strumenti culturali giusti per entrare nel complesso mondo di Limonov, il suo cosiddetto «pensiero fascista», aggettivo che di per sé è già una condanna... Ha avuto una giovinezza intellettuale a destra, nel senso delle letture e delle predisposizioni familiari, ne conosce gli autori, in specie quelli francesi, i concetti di decadenza e di tradizione, gli elementi mitici e simbolici. Solo che Limonov non è Drieu La Rochelle o Evola, Céline o Maurras... È qualcosa di diversamente russo, panlavista e futurista, Nietzsche più Dostoevskij, Necaev più d'Annunzio, Alessandro il Grande e Che Guevara...La diversità è ancora più evidente se si esamina la sua creatura politica. I suoi «nazbol», i nazionalbolscevichi dalla testa rasata e dalla bandiera che ricorda quella nazista, con la falce e martello però al posto della croce uncinata, erano per Anna Politkovskaja, la celebre giornalista che pagò il suo coraggio investigativo con la morte, la faccia pulita della Russia anti-Putin, e lo stesso per Elena Bonner, la vedova di Sacha. Le loro armi eversive sono pomodori, uova marce e torte in faccia, le loro manifestazioni una via di mezzo fra goliardia e riproposizione delle avanguardie storiche. È gente che rischia la galera, quella russa, per appendere uno striscione vietato o per protestare contro la discriminazione della minoranza russa in Estonia... Sono militanti che si ritrovano in un credo limonoviano che suona così: «Sei giovane, non ti piace vivere in questo Paese di merda. Non vuoi diventare un anonimo compagno Popov, né un figlio di puttana che pensa soltanto al denaro, né un cekista. Sei uno spirito ribelle. I tuoi eroi sono Jim Morrison, Lenin, Mishima, Baader. Ecco: sei già un nazbol».Carrère coglie bene un punto del percorso politico-esistenziale di Limonov: «Bisogna dare atto di una cosa a questo fascista: gli piacciono e gli sono sempre piaciuti soltanto quelli che sono in posizione di inferiorità. I magri contro i grassi, i poveri contro i ricchi, le carogne dichiarate, che sono rare, contro le legioni di virtuosi, e il suo percorso, per quanto ondivago possa sembrare, ha una sua coerenza, perché Eduard si è schierato sempre, senza eccezione, dalla loro parte». È proprio questo a separarlo da Putin, che a Carrère sembra invece un Limonov che ce l'ha fatta, perché ha vinto, perché ha il potere. Limonov non vuole il potere per il potere, non sa che farsene. «Sì, ho deciso di schierarmi con il male, con i giornali da strapazzo, con i volantini ciclostilati, con i movimenti e i partiti che non hanno nessuna possibilità di farcela. Nessuna. Mi piacciono i comizi frequentati da quattro gatti, la musica cacofonica di musicisti senza talento...». La sua è un'estetica della politica, ha più a che fare con la comunità d'appartenenza, la fedeltà a uno stile, a delle amicizie, al senso dell'onore, che con una logica di conquista. Ricerca un eroismo e una purezza di comportamenti che lo allontanano mille miglia dalla Russia putiniana, troppo volgare, troppo borghesemente occidentale ai suoi occhi, troppo grassa nella sua ricerca del benessere. Resta un outsider Limonov, ma non un perdente, visto che vive la vita che ha sempre voluto vivere. Un orgoglioso re senza regno e uno scrittore che vale la pena leggere.

Tante altre notizie su www.ariannaeditrice.it

00:15 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lettres, littérature, lettres russes, littérature russe, russie, national-bolchevisme, édouard limonov |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 15 octobre 2012

Henry Bauchau: un témoin s’en est allé...

Robert STEUCKERS:

Henry Bauchau: un témoin s’en est allé...

La disparition récente d’Henry Bauchau, en ce mois de septembre 2012, atteste surtout, dans les circonstances présentes, de la disparition d’un des derniers témoins importants de la vie politique et intellectuelle de nos années 30 et du “non-conformisme” idéologique de Belgique francophone, un non-conformisme que l’on mettra en parallèle avec celui de ses homologues français, décrits par Jean-Louis Loubet-del Bayle ou par Paul Sérant.

Pour Henry Bauchau, et son ancien compagnon Raymond De Becker, comme pour bien d’autres acteurs contemporains issus du monde catholique belge, l’engagement des années 30 est un engagement qui revendique la survie d’abord, la consolidation et la victoire ensuite, d’une rigueur éthique (traditionnelle) qui ployait alors sous les coups des diverses idéologies modernes, libérales, socialistes ou totalitaires, qui toutes voulaient s’en débarrasser comme d’une “vieille lune”; cette rigueur éthique avait tendance à s’estomper sous les effets du doute induit par ce que d’aucuns nommaient “les pensées ou les idéologies du soupçon”, notamment Monseigneur Van Camp, ancien Recteur des Facultés Universitaires Saint Louis, un ecclésiastique philosophe et professeur jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Cette exigence d’éthique, formulée par Bauchau et De Becker sur fond de crise des années 30, sera bien entendu vilipendée comme “fasciste”, ou au moins comme “fascisante”, par quelques terribles simplificateurs du journalisme écrit et télévisé actuel. Formuler de telles accusations revient à énoncer des tirades à bon marché, bien évidemment hors de tout contexte. Quel fut ce contexte? D’abord, la crise sociale de 1932 et la crise financière de 1934 (où des banques font faillite, plument ceux qui leur ont fait confiance et réclament ensuite l’aide de l’Etat...) amènent au pouvoir des cabinets mixtes, catholiques et socialistes. L’historien et journaliste flamand Rolf Falter, dans “België, een geschiedenis zonder land” (2012) montre bien que c’était là, dans le cadre belge d’alors, une nouveauté politique inédite, auparavant impensable car personne n’imaginait qu’aurait été possible, un jour, une alliance entre le pôle clérical, bien ancré dans la vie associative des paroisses, et le parti socialiste, athée et censé débarrasser le peuple de l’opium religieux.

Un bloc catholiques/socialistes?

Les premiers gouvernements catholiques/socialistes ont fait lever l’espoir, dans toute la génération née entre 1905 et 1920, de voir se constituer un bloc uni du peuple derrière un projet de société généreux, alliant éthique rigoureuse, sens du travail (et de l’ascèse) et justice sociale. Face à un tel bloc, les libéraux, posés comme l’incarnation politique des égoïsmes délétères de la bourgeoisie, allaient être définitivement marginalisés. Catholiques et socialistes venaient cependant d’horizons bien différents, de mondes spécifiques et bien cloisonnés: la foi des uns et le matérialisme doctrinaire des autres étaient alors comme l’eau et le feu, antagonistes et inconciliables. La génération de Bauchau et de De Becker, surtout la fraction de celle-ci qui suit l’itinéraire de l’Abbé Jacques Leclerq, va vouloir résoudre cette sorte de quadrature du cercle, oeuvrer pour que la soudure s’opère et amène les nouvelles et les futures générations vers une Cité harmonieuse, reflet dans l’en-deça de la Cité céleste d’augustinienne mémoire, où la vie politique serait entièrement déterminée par le bloc uni, appellé à devenir rapidement majoritaire, par la force des choses, par la loi des urnes, pour le rester toujours, ou du moins fort longtemps. Henri De Man, leader des socialistes et intellectuel de grande prestance, avait fustigé le matérialisme étroit des socialistes allemands et belges, d’une sociale-démocratie germanique qui avait abandonné, dès la première décennie du siècle, ses aspects ludiques, nietzschéo-révolutionnaires, néo-religieux, pour les abandonner d’abord aux marges de la “droite” sociologique ou du mouvement de jeunesse ou des cénacles d’artistes “Art Nouveau”, “Jugendstil”. De Man avait introduit dans le corpus doctrinal socialiste l’idée de dignité (Würde) de l’ouvrier (et du travail), avait réclamé une justice sociale axée sur une bonne prise en compte de la psychologie ouvrière et populaire. Les paramètres rigides du matérialisme marxiste s’étaient estompés dans la pensée de De Man: bon nombre de catholiques, dont Bauchau et De Becker, chercheront à s’engouffrer dans cette brèche, qui, à leurs yeux, rendait le socialisme fréquentable, et à servir un régime belge entièrement rénové par le nouveau binôme socialistes/catholiques. Sur le très long terme, ce régime “jeune et nouveau” reposerait sur ces deux piliers idéologiques, cette fois ravalés de fond en comble, et partageant des postulats idéologiques ou religieux non individualistes, en attendant peut-être la fusion en un parti unique, apte à effacer les tares de la partitocratie parlementaire, à l’époque fustigées dans toute l’Europe. Pour De Becker, la réponse aux dysfonctionnements du passé résidait en la promotion d’une éthique “communautaire”, inspirée par le réseau “Esprit” d’Emmanuel Mounier et par certaines traditions ouvrières, notamment proudhoniennes; c’est cette éthique-là qui devait structurer le nouvel envol socialo-catholique de la Belgique.

Les jeunes esprits recherchaient donc une philosophie, et surtout une éthique, qui aurait fusionné, d’une part, l’attitude morale irréprochable qu’une certaine pensée catholique, bien inspirée par Léon Bloy, prétendait, à tort ou à raison, être la sienne et, d’autre part, un socialisme sans corsets étouffants, ouvert à la notion immatérielle de dignité. Les “daensistes” démocrates-chrétiens et les résidus de la “Jeune Droite” de Carton de Wiart, qui avaient réclamé des mesures pragmatiques de justice sociale, auraient peut-être servi de passerelles voire de ciment. Toute l’action politique de Bauchau et de De Becker dans des revues comme “La Cité chrétienne” (du Chanoine Jacques Leclercq) ou “L’Esprit nouveau” (de De Becker lui-même) viseront à créer un “régime nouveau” qu’on ne saurait confondre avec ce que d’aucuns, plus tard, et voulant aussi oeuvrer à une régénération de la Cité, ont appelé l’“ordre nouveau”. Cette attitude explique la proximité du tandem Bauchau/De Becker avec les socialistes De Man, jouant son rôle de théoricien, et Spaak, représentant le nouvel espoir juvénile et populaire du POB (“Parti Ouvrier Belge”). Et elle explique aussi que le courant n’est jamais passé entre ce milieu, qui souhaitait asseoir la régénération de la Cité sur un bloc catholiques/socialistes, inspiré par des auteurs aussi divers que Bloy, Maritain, Maurras, Péguy, De Man, Mounier, etc., et les rexistes de Léon Degrelle, non pas parce que l’attitude morale des rexistes était jugée négative, mais parce que la naissance de leur parti empêchait l’envol d’un binôme catholiques/socialistes, appelé à devenir le bloc uni, soudé et organique du peuple tout entier. Selon les termes mêmes employés par De Becker: “un nouveau sentiment national sur base organique”.

Guerre civile espagnole et rexisme

Pour Léo Moulin, venu du laïcisme le plus caricatural d’Arlon, il fallait jeter les bases “d’une révolution spirituelle”, basée sur le regroupement national de toutes les forces démocratiques mais “en dehors des partis existants” (Moulin veut donc la création d’un nouveau parti dont les membres seraient issus des piliers catholiques et socialistes mais ne seraient plus les vieux briscards du parlement), en dehors des gouvernements dits “d’union nationale” (c’est-à-dire des trois principaux partis belges, y compris les libéraux) et sans se référer au modèle des “fronts populaires” (c’est-à-dire avec les marxistes dogmatiques, les communistes ou les bellicistes anti-fascistes). L’option choisie fin 1936 par Emmanuel Mounier de soutenir le front populaire français, puis son homologue espagnol jeté dans la guerre civile suite à l’alzamiento militaire, consacrera la rupture entre les personnalistes belges autour de De Becker et Bauchau et les personnalistes français, remorques lamentables des intrigues communistes et staliniennes. Les pôles personnalistes belges ont fait davantage preuve de lucidité et de caractère que leurs tristes homologues parisiens; dans “L’enfant rieur”, dernier ouvrage autobiographique de Bauchau (2011), ce dernier narre le désarroi qui règnait parmi les jeunes plumes de la “Cité chrétienne” et du groupe “Communauté” lorsque l’épiscopat prend fait et cause pour Franco, suite aux persécutions religieuses du “frente popular”. Contrairement à Mounier (ou, de manière moins retorse, à Bernanos), il ne sera pas question, pour les disciples du Chanoine Leclercq, de soutenir, de quelque façon que ce soit, les républicains espagnols.

La naissance du parti rexiste dès l’automne 1935 et sa victoire électorale de mai 1936, qui sera toutefois sans lendemain vu les ressacs ultérieurs, freinent provisoirement l’avènement de cette fusion entre catholiques/socialistes d’”esprit nouveau”, ardemment espérée par la nouvelle génération. Le bloc socialistes/catholiques ne parvient pas à se débarrasser des vieux exposants de la social-démocratie: De Man déçoit parce qu’il doit composer. Avec le départ des rexistes hors de la vieille “maison commune” des catholiques, ceux-ci sont déforcés et risquent de ne pas garder la majorité au sein du binôme... De Becker avait aussi entraîné dans son sillage quelques communistes originaux et “non dogmatiques” comme War Van Overstraeten (artiste-peintre qui réalisara un superbe portrait de Bauchau), qui considérait que l’anti-fascisme des “comités”, nés dans l’émigration socialiste et communiste allemande (autour de Willy Münzenberg) et suite à la guerre civile espagnole, était lardé de “discours creux”, qui, ajoutait le communiste-artiste flamand, faisaient le jeu des “puissances impérialistes” (France + Angleterre) et empêchaient les dialogues sereins entre les autres peuples (dont le peuple allemand d’Allemagne et non de l’émigration); De Becker entraîne également des anarchistes sympathiques comme le libertaire Ernestan (alias Ernest Tanrez), qui s’activait dans le réseau de la revue et des meetings du “Rouge et Noir”, dont on commence seulement à étudier l’histoire, pourtant emblématique des débats d’idées qui animaient Bruxelles à l’époque.

On le voit, l’effervescence des années de jeunesse de Bauchau est époustouflante: elle dépasse même la simple volonté de créer une “troisième voie” comme on a pu l’écrire par ailleurs; elle exprime plutôt la volonté d’unir ce qui existe déjà, en ordre dispersé dans les formations existantes, pour aboutir à une unité nationale, organique, spirituelle et non totalitaire. L’espoir d’une nouvelle union nationale autour de De Man, Spaak et Van Zeeland aurait pu, s’il s’était réalisé, créer une alternative au “vieux monde”, soustraite aux tentations totalitaires de gauche ou de droite et à toute influence libérale. Si l’espoir de fusionner catholiques et socialistes sincères dans une nouvelle Cité —où “croyants” et “incroyants” dialogueraient, où les catholiques intransigeants sur le plan éthique quitteraient les “ghettos catholiques” confis dans leurs bondieuseries et leurs pharisaïsmes— interdisait d’opter pour le rexisme degrellien, il n’interdisait cependant pas l’espoir, clairement formulé par De Becker, de ramener des rexistes, dont Pierre Daye (issu de la “Jeune Droite” d’Henry Carton de Wiart), dans le giron de la Cité nouvelle si ardemment espérée, justement parce que ces rexistes alliaient en eux l’âpre vigueur anti-bourgeoise de Bloy et la profondeur de Péguy, défenseur des “petites et honnêtes gens”. C’est cet espoir de ramener les rexistes égarés hors du bercail catholique qui explique les contacts gardés avec José Streel, idéologue rexiste, jusqu’en 1943. Streel, rappelons-le, était l’auteur de deux thèses universitaires: l’une sur Bergson, l’autre sur Péguy, deux penseurs fondamentaux pour dépasser effectivement ce monde vermoulu que la nouvelle Cité spiritualisée devait mettre définitivement au rencart.

Les tâtonnements de cette génération “non-conformiste” des années 30 ont parfois débouché sur le rexisme, sur un socialisme pragmatique (celui d’Achille Van Acker après 1945), sur une sorte de catho-communisme à la belge (auquel adhérera le Chanoine Leclercq, appliquant avec une dizaine d’années de retard l’ouverture de Maritain et Mounier aux forces socialo-marxistes), sur une option belge, partagée par Bauchau, dans le cadre d’une Europe tombée, bon gré mal gré, sous la férule de l’Axe Rome/Berlin, etc. Après les espoirs d’unité, nous avons eu la dispersion... et le désespoir de ceux qui voulaient porter remède à la déchéance du royaume et de sa sphère politique. Logique: toute politicaillerie, même honnête, finit par déboucher dans le vaudeville, dans un “monde de lémuriens” (dixit Ernst Jünger). Mais c’est faire bien basse injure à ces merveilleux animaux malgaches que sont les lémuriens, en osant les comparer au personnel politique belge d’après-guerre (où émergeaient encore quelques nobles figures comme Pierre Harmel, lié d’amitié à Bauchau) pour ne pas parler du cortège de pitres, de médiocres et de veules qui se présenteront aux prochaines élections... Plutôt que le terme “lémurien”, prisé par Jünger, il aurait mieux valu user du vocable de “bandarlog”, forgé par Kipling dans son “Livre de la Jungle”.

Les tâtonnements de cette génération “non-conformiste” des années 30 ont parfois débouché sur le rexisme, sur un socialisme pragmatique (celui d’Achille Van Acker après 1945), sur une sorte de catho-communisme à la belge (auquel adhérera le Chanoine Leclercq, appliquant avec une dizaine d’années de retard l’ouverture de Maritain et Mounier aux forces socialo-marxistes), sur une option belge, partagée par Bauchau, dans le cadre d’une Europe tombée, bon gré mal gré, sous la férule de l’Axe Rome/Berlin, etc. Après les espoirs d’unité, nous avons eu la dispersion... et le désespoir de ceux qui voulaient porter remède à la déchéance du royaume et de sa sphère politique. Logique: toute politicaillerie, même honnête, finit par déboucher dans le vaudeville, dans un “monde de lémuriens” (dixit Ernst Jünger). Mais c’est faire bien basse injure à ces merveilleux animaux malgaches que sont les lémuriens, en osant les comparer au personnel politique belge d’après-guerre (où émergeaient encore quelques nobles figures comme Pierre Harmel, lié d’amitié à Bauchau) pour ne pas parler du cortège de pitres, de médiocres et de veules qui se présenteront aux prochaines élections... Plutôt que le terme “lémurien”, prisé par Jünger, il aurait mieux valu user du vocable de “bandarlog”, forgé par Kipling dans son “Livre de la Jungle”.

De la défaite aux “Volontaires du Travail”

Après l’effondrement belge et français de mai-juin 1940, Bauchau voudra créer le “Service des Volontaires du Travail de Wallonie” et le maintenir dans l’option belge, “fidelles au Roy jusques à porter la besace”. Cette fidélité à Léopold III, dans l’adversité, dans la défaite, est l’indice que les hommes d’”esprit nouveau”, dont Bauchau, conservaient l’espoir de faire revivre la monarchie et l’entité belges, toutefois débarrassée de ses corruptions partisanes, dans le cadre territorial inaltéré qui avait été le sien depuis 1831, sans partition aucune du royaume et en respectant leurs serments d’officier (Léopold III avait déclaré après la défaite: “Demain nous nous mettrons au travail avec la ferme volonté de relever la patrie de ses ruines”). Animés par la volonté de concrétiser cette injonction royale, les “Volontaires du travail” (VT) portaient un uniforme belge et un béret de chasseur ardennais et avaient adopté les traditions festives, les veillées chantées, du scoutisme catholique belge, dont beaucoup étaient issus. Les VT accompliront des actions nécessaires dans le pays, des actions humbles, des opérations de déblaiement dans la zone fortifiée entre Namur et Louvain dont les ouvrages défensifs étaient devenus inutiles, des actions de secours aux sinistrés suite à l’explosion d’une usine chimique à Tessenderloo, suite aussi au violent bombardement américain du quartier de l’Avenue de la Couronne à Etterbeek (dont on perçoit encore les traces dans le tissu urbain). Le “Front du Travail” allemand ne tolèrait pourtant aucune “déviance” par rapport à ses propres options nationales-socialistes dans les parties de l’Europe occupée, surtout celles qui sont géographiquement si proches du Reich. Les autorités allemandes comptaient donc bien intervenir dans l’espace belge en dictant leur propre politique, marquée par les impératifs ingrats de la guerre. Par l’intermédiaire de l’officier rexiste Léon Closset, qui reçoit “carte blanche” des Allemands, l’institution fondée par Bauchau et Teddy d’Oultremont est très rapidement “absorbée” par le tandem germano-rexiste. Bauchau démissionne, rejoint les mouvements de résistance royalistes, tandis que De Becker, un peu plus tard, abandonne volontairement son poste de rédacteur en chef du “Soir” de Bruxelles, puis est aussitôt relégué dans un village bavarois, où il attendra la fin de la guerre, avec l’arrivée des troupes africaines de Leclerc. L’option “belge” a échoué (Bauchau: “si cela [= les VT] fut une erreur, ce fut une erreur généreuse”). La belle Cité éthique, tant espérée, n’est pas advenue: des intellectuels inégalés comme Leclercq ou Marcel de Corte tenteront d’organiser l’UDB catho-communisante puis d’en sortir pour jeter les bases du futur PSC. En dépit de son engagement dans la résistance, où il avait tout simplement rejoint les cadres de l’armée, de l’AS (“Armée Secrète”) de la région de Brumagne, Bauchau est convoqué par l’auditorat militaire qui, imperméable à toutes nuances, ose lui demander des comptes pour sa présence active au sein du directorat des “Volontaires”. Il n’est pas jugé mais, en bout de course, à la fin d’un parcours kafkaïen, il est rétrogradé —de lieutenant, il redevient sergent— car, apparemment, on ne veut pas garder des officiers trop farouchement léopoldistes. Dégoûté, Bauchau s’exile. Une nouvelle vie commence. C’est la “déchirure”.

Comme De Becker, croupissant en prison, comme Hergé, comme d’autres parmi les “Volontaires”, dont un juriste à cheval entre l’option Bauchau et l’option rexiste, dont curieusement aucune source ne parle, notre écrivain en devenir, notre ancien animateur de la “Cité chrétienne”, notre ancien maritainiste qui avait fait le pèlerinage à Meudon chez le couple Raïssa et Jacques Maritain, va abandonner l’aire intellectuelle catholique, littéralement “explosée” après la seconde guerre mondiale et vautrée depuis dans des compromissions et des tripotages sordides. Cela vaut pour la frange politique, totalement “lémurisée” (“bandarloguisée”!), comme pour la direction “théologienne”, cherchant absolument l’adéquation aux turpitudes des temps modernes, sous le fallacieux prétexte qu’il faut sans cesse procéder à des “aggiornamenti” ou, pour faire amerloque, à des “updatings”. L’éparpillement et les ruines qui résultaient de cette explosion interdisait à tous les rigoureux de revenir dans l’un ou l’autre de ces “aréopages”: d’où la déchristianisation post bellum de ceux qui avaient été de fougueux mousquetaires d’une foi sans conformismes ni conventions étouffantes.

De la “déchirure” à la thérapie jungienne

L’itinéraire du Bauchau progressivement auto-déchristianisé est difficile à cerner, exige une exégèse constante de son oeuvre poétique et romanesque à laquelle s’emploient Myriam Watthée-Delmotte à Louvain-la-Neuve et Anne Neuschäfer auprès des chaires de philologie romane à Aix-la-Chapelle. Le décryptage de cet itinéraire exige aussi de plonger dans les méandres, parfois fort complexes, de la psychanalyse jungienne des années 50 et 60. Les deux philologues analysent l’oeuvre sans escamoter le passé politique de l’auteur, sans quoi son rejet de la politique, de toute politique (à l’exception d’une sorte de retour bref et éphémère par le biais d’un certain maoïsme plus littéraire que militant) ne pourrait se comprendre: c’est la “déchirure”, qu’il partage assurément, mutatis mutandis, avec De Becker et Hergé, “meurtrissure” profonde et déstabilisante qu’ils chercheront tous trois à guérir via une certaine interprétation et une praxis psychanalytiques jungiennes, une “déchirure” qui fait démarrer l’oeuvre romanesque de Bauchau, d’abord timidement, dès la fin des années 40, sur un terreau suisse d’abord, où une figure comme Gonzague de Reynold, non épurée et non démonisée vu la neutralité helvétique pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, n’est pas sans liens intellectuels avec le duo De Becker/Bauchau et, surtout, évolue dans un milieu non hostile, mais dont la réceptivité, sous les coups de bélier du Zeitgeist, s’amoindrira sans cesse.