Nous avons longtemps hésité avant de classer l'article d'Hervé Glot, issu d'une contribution au magazine des Amis de l'écrivain normando-breton, Jean Mabire . Il avait sa place dans notre rubrique "émotion/réflexion", car l'histoire du magazine Artus relève d'abord de la littérature, de la poésie, de l'image et de l'imaginaire. Mais par la vocation ambitieuse qu'elle s'assignait, au service de la large culture celte, toujours vivante et ardente, par l'enthousiasme qu'elle a suscité auprès d'artistes, d'intellectuels, du public, par l'impulsion enfin qui continue de nourrir rêves et convictions, elle relève finalement de la rubrique "communautés vivantes".

Guilhem Kieffer

"Difficile de prendre individuellement la parole au sujet d’une aventure qui fut avant tout collective, d’autant que les années ont en partie gommé le contexte qui vit la naissance et l’évolution de la revue Artus, puis, par la suite, des éditions du même nom. Mais soit, je tenterai d’être le chroniqueur concis et néanmoins fidèle d’une chevauchée qui s’est étalée dans le temps et bien sûr, comme tout corps vivant, a initié ou subi ses propres métamorphoses.

L’affaire est ancienne, puisque c’est en 1979 que fut fondée l’association éditrice de la revue, avec pour dessein d’explorer les voies de la culture celtique d’hier, et d’en faire entendre les voix d’aujourd’hui. Cette association naissait en Bretagne, à Nantes capitale du duché, et Jean-Louis Pressensé en était le directeur et le premier rédacteur. Artus : le nom avait, bien sûr, été choisi en référence au roi de la Table Ronde, dont le royaume légendaire s’étendait sur les deux rives de la Manche.

Il élargissait considérablement le réduit breton auquel nous étions certes attachés… mais à condition d’exercer toute liberté dans les instants où il nous siérait de larguer les amarres, comme en témoignait le sous-titre "pays celtiques et monde nordique". L’association était née d’une réaction contre une certaine vision en vogue dans les années 70, celle d’une Bretagne étroite, suffisante et, pour finir, morte d’un trop plein "de légitimes revendications et de droits imprescriptibles"…

Sources et survivances d’un imaginaire celtique

Nous souhaitions rechercher, au sein d’un univers plus large, les sources et les survivances d’un imaginaire celtique. Et nous nous interrogions: « Segalen est-il moins celte quand il compose Les Immémoriaux, Kenneth White quand il décrit Hong-Kong, Michel Mohrt quand il rédige "L’ours des Adirondacks ?" »

Dès lors se posait le problème du contenu que nous entendions donner au terme « celtique ». Pour ma part, très sensible à l’enseignement que prodiguait (parfois dans la douleur) Christian-J. Guyonvarc’h, l’Irlande, avec sa mythologie miraculeusement transmise, était un des conservatoires et l’un des foyers où aller chercher les brandons encore vivants du grand récit. Des brandons à raviver parce que, sans cette lueur venue de ses franges "barbares’", l’Europe, qui cherchait à s’inventer, faisait l’impasse sur une partie de son âme (elle a fait mieux depuis !). De notre point de vue, c’était pour les artistes, les créateurs, se priver d’une source d’inspiration dont des écrivains majeurs, comme Yeats ou Joyce (bon gré, mal gré), avaient fait le suc de leur œuvre, et dont le cinéma s’emparait désormais avec gourmandise. J’aime toujours rappeler que l’Irlande, un tout petit pays, peut se flatter d’avoir porté, bien au-delà de son nombril, la lumière de ses écrivains et que l’imaginaire est une pensée vivante, une flamme que l’on ravive au contact de la diversité du monde.

Pourtant, la volée de bois vert ne vint pas des Bretons pur beurre : il apparut rapidement que l’usage que nous faisions des termes celte ou celtique, et ce que nous affirmions comme un héritage mésestimé étaient, pour certains, des vocables strictement interdits, des territoires de la pensée absolument prohibés. Passons sur ces polémiques, elles n’en méritent pas davantage.

Un sentiment géographique et quasi climatique

Nous cherchions à faire partager un sentiment géographique et quasi climatique : cette Europe du nord-ouest, atlantique et baltique, est (de toute évidence) un mélange de terre et d’eau, un espace terraqué aux limites indécises, aux lumières parfois incertaines et aux origines parfois contradictoires. Nous souhaitions faire naître peu à peu, par les textes des chercheurs, ceux des écrivains et des poètes, les œuvres des photographes, des peintres ou des graveurs, etc, une esthétique, un esprit, qui donneraient à la revue une couleur que j’espérais singulière.

Jean-Louis Pressensé avait, au tout début de l’aventure, suggéré cet en-dehors des territoires trop arrimés, en évoquant l’Artusien en devenir : « Etre enfant du granit, de la houle, des forêts et du vent, être pétri de fidélité, de folie et de rêves…» Et, effectivement, les filiations furent de cœur, de consanguinité spirituelle, de générosité, jamais fondées sur l’intérêt ou le conformisme idéologique.

La revue fut, pour bien des rédacteurs, une école pratique et un centre de formation intellectuelle. Nous approfondissions nos compétences techniques, passant de la terrible composphère, fleuron de chez IBM, à l’ordinateur, et la table de la salle à manger, qui servait de table de montage, conserve les ineffaçables stigmates du cutter de mise en page : à ces moments-là, il fallait penser avec les mains, non sans avoir affirmé, quelques instants auparavant, après Rimbaud, que la main à plume valait bien la main à charrue.

Nous allions vers les artistes ou les chercheurs par inclination personnelle, aussi bien que par curiosité pour qui nous intriguait. Ainsi, la revue développait son contenu, tandis que les numéros sortaient avec la régularité qu’autorisaient nos occupations professionnelles. Artus a fédéré des énergies, confronté des individualités et surtout nous a conforté dans le sentiment que l’équilibre, le nôtre en tout cas, se trouve où cohabitent le travail des savants et le chant des poètes.

Un équilibre où cohabitent le travail des savants et le chant des poètes

Peu à peu, nous avons orienté notre publication vers des thèmes plus précis. Parurent ainsi "Le Graal", "A chacun ses Irlande", "Au nord du monde", "Harmonique pour la terre", "L’Amour en mémoire", "Ecosse blanches terres", "Mégalithes", "Archipels, vents et amers", autant de titres qui signaient des affinités électives, des rencontres insolites ou prévisibles. Avec le recul, cette formule éditoriale a eu le grand avantage d’ouvrir un espace accueillant et de permettre la constitution d’un noyau de collaborateurs, qui auront trouvé dans le rythme revuiste, à la fois souplesse, diversité et régularité.

Les universitaires Jacques Briard pour l’archéologie, Christian-J. Guyonvac’h pour le domaine celtique, Léon Fleuriot pour les origines de la Bretagne, Philippe Walter pour la littérature arthurienne, Régis Boyer pour le monde nordique, Gilbert Durand pour le vaste champ de l’imaginaire, furent parmi d’autres, nos guides et nos interlocuteurs. Patrick Grainville et Kenneth White nous donnèrent de sérieux coups de main. Philippe Le Guillou a été le compagnon de nos rêveries scoto-hiberniennes. Michel Le Bris a bercé nos songes romantiques au rythme des puissances de la fiction; quant à Pierre Dubois, il a été pour nous tous l’empêcheur de raisonner en rond, le Darby O’Gill des raths et des moors.

La revue a permis, en outre, de créer un lectorat qui est naturellement resté fidèle lors du glissement -amorcé en douceur au milieu des années 80- de la revue vers la maison d’édition, ayant ainsi, pour effet, de résoudre partiellement le problème de la diffusion.

Après s’être essayé à la publication de textes relativement courts : "Enez Eussa" de Gilles Fournel, "Marna" d’Yvon Le Menn, "la Main à plume" de Philippe Le Guillou, suivront une vingtaine de livres dont "Ys dans la rumeur des vagues" de Michel Le Bris, ou "Les Guerriers de Finn" de Michel Cazenave. Des albums sont consacrés à des peintres, des sculpteurs, des graveurs, des photographes (Yvon Boëlle, Jean Hervoche, Carmelo de la Pinta, Bernard Louedin, Sophie Busson, Jean Lemonnier, Geneviève Gourivaud).

Avec Pierre Joannon, nous éditerons un gros album, "L’Irlande ou les musiques de l’âme", une somme menant de la protohistoire à la genèse de l’Irlande contemporaine, que reprendront les éditions Ouest-France. Toujours à l’affut des méandres de la création, sous la direction de Jacqueline Genêt, de l’université de Caen, nous avons publié les variations des écrivains de la renaissance culturelle irlandaise, autour de la légende de Deirdre.

Pierre Joannon

Pierre Joannon

Depuis ces temps de fondation, d’autres livres bien sûr sont parus, parfois en coédition avec Hoëbeke ou Siloë. Citons "Arrée, l’archange et le dragon", "Des Bretagne très intérieures", "Une Rhapsodie irlandaise", plus récemment "Lanval" et ,dernier en date, "Les îles au nord du monde", un texte de Marc Nagels illustré par Didier Graffet, avec des photographies de Vincent Munier.

Un numéro spécial avait marqué un tournant dans l’histoire d’Artus. Ce n’était déjà plus le fascicule habituel, mais un véritable album titré "Brocéliande ou l’obscur des forêts". Il allait nous conduire vers une autre direction : une heureuse conjonction permit à Claudine de créer et d’asseoir" au château de Comper" le Centre de l’Imaginaire Arthurien. Mais cela est une autre histoire, et je ne voudrais pas m’approprier abusivement ce qui appartient à une fraternité sûrement plus vaste que la mienne, sinon en rappelant ce que pourrait être… une errance arthurienne.

Vagabondage dans l’espace arthurien

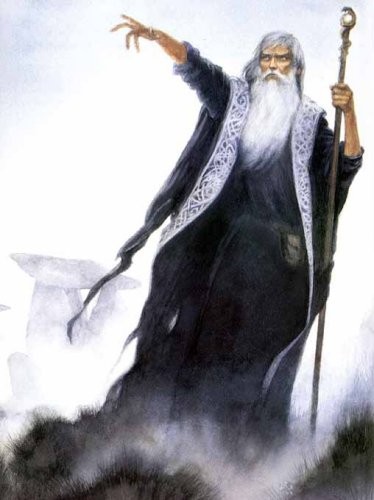

Histoire des hommes et de leur imaginaire, rêves, foi, mythes, voilà un terrain de pérégrinations assez inépuisable, au milieu duquel l’héritage celtique et la légende arthurienne brillent, aujourd’hui, d’un éclat particulier, avec leur cortège de prouesses et d’enchantements, dont le moindre n’est pas la promesse de la quête.

Le roman arthurien n’a pas inventé la quête, mais il lui a donné une couleur et une dimension renouvelées. La quête chevaleresque n’est ni la descente aux Enfers d’Orphée ou de Virgile, la fuite d’Énée ou la dérive involontaire d’Ulysse. À travers d’innombrables épreuves, dont on ne sait dans quelle réalité elles se déroulent, elle unit, à un voyage qui porte ordre et lumière là où règne le chaos, un cheminement intérieur, recherche de perfection ou d’absolu.

Au centre de la cour arthurienne, la Table Ronde rassemble les meilleurs chevaliers, venus du monde entier briguer l’honneur de servir. Alors, commencent les expéditions, entreprises sur un signe, une requête, un récit marqué d'étrangeté. Lorsqu’il prend la route, chaque chevalier devient, à lui seul, l’honneur de la Table Ronde et la gloire du roi. Il forme l'essence même de la chevalerie arthurienne, affirmant la nécessité de l'errance, le dédain des communes terreurs, la solitude, qui ne s’accompagne que d’un cheval et d’une épée. Il ne sait ni le chemin à suivre, ni les épreuves qui l'attendent. Un seule règle, absolue, lui dicte de « prendre les aventures comme elles arrivent, bonnes ou mauvaises ». Il ne se perd pas, tant qu’il suit la droite voie, celle de l'honneur, du code la chevalerie.

La nécessité de la Quête est partie intégrante du monde arthurien. Au hasard de sa route, le chevalier vient à bout des forces hostiles. Il fait naître l’harmonie, l’âge d’or de la paix arthurienne dans son permanent va et vient entre ce monde-ci et l’Autre Monde, car l’aventure, où il éprouve sa valeur, ne vaut que si elle croise le chemin des merveilles. Sinon elle n’est qu’exploit guerrier, bravoure utilitaire. Seul, le monde surnaturel, qui attend derrière le voile du réel, l’attire, et lui seul est qualifiant.

Les poètes recueillent la Matière de Bretagne vers le XIIe siècle, de la bouche même des bardes gallois et, sans doute, bretons. Malgré le prestige du monde antique et des romans qu’il inspire et qui ne manquent pas de prodiges, la société cultivée découvre, fascinée, les légendes des Bretons (aujourd’hui nous parlerions des Celtes), un univers culturel perçu comme tout autre, d’une étrangeté absolue. Le roman, cette forme nouvelle nourrie de mythes anciens, donne naissance à des mythes nouveaux, la Table Ronde, le Graal, l’amour de Tristan pour Iseult, Merlin… Parmi les référents culturels de l’Europe, en train de naître, elle s’impose en quelques dizaines d’années, du Portugal à l’Islande, de la Sicile à l’Écosse.

La légende celtique, mêlée d’influences romanes ou germaniques, constitue une composante fondamentale pour l’Europe en quête d’une identité qui transcende les nécessités économiques et politiques. Mais le thème de la quête représente, plus fondamentalement croyons-nous, un itinéraire proprement spirituel, initiatique ou mystique même, pour certains. Elle manifeste, aussi, un besoin d’enracinement, la recherche de valeurs anciennes, prouesse, courtoisie, fidélité, largesse, l’aspiration à l’image idéale de ce que nous pourrions être.

Une fois de plus, le roi Arthur revient : non pas la figure royale, mais l’univers de liberté et d’imaginaire qu’il convoie. A qui s’interroge sur cette postérité tenace, sur ces résurrections insistantes, on peut trouver des raisons, dans le désordre, culturelles, patrimoniales, psychanalytique, politiques, artistiques. Pour nous, nous dirons, simplement et très partialement, qu’il s’agit de la plus belle histoire du monde, et qu’il suffit de revenir au récit, à ces mots qui voyagent vers nous, depuis plus de huit siècles, pour comprendre que les enchantements de Bretagne ne sont pas près de prendre fin."

Ich will direkt an Kubitscheks

Ich will direkt an Kubitscheks

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

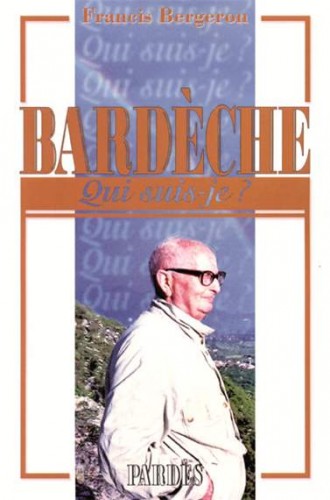

Après avoir écrit pour la même collection la biographie condensée d’Henri Béraud, de Léon Daudet, de Henry de Monfreid, de Hergé et de Saint-Loup, Francis Bergeron évoque cette fois-ci la vie d’une personne qu’il a bien connue : Maurice Bardèche.

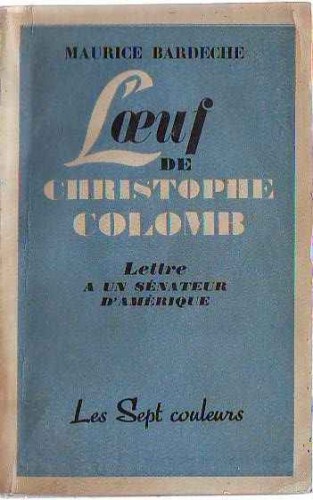

Après avoir écrit pour la même collection la biographie condensée d’Henri Béraud, de Léon Daudet, de Henry de Monfreid, de Hergé et de Saint-Loup, Francis Bergeron évoque cette fois-ci la vie d’une personne qu’il a bien connue : Maurice Bardèche. C’est sur la question européenne que Maurice Bardèche a conservé toute sa pertinence. Quand on lit L’œuf de Christophe Colomb (1952) ou Sparte et les Sudistes, on se régale de ses fines analyses. Bardèche réfléchissait en nationaliste français et européen. À la fin de l’opuscule, avant l’habituelle étude astrologique de Marin de Charette et après les annexes biographiques, bibliographiques, de commentaires sur Bardèche et de quelques-unes de ses citations les plus marquantes, Francis Bergeron reproduit l’entretien que lui accorda Bardèche dans Rivarol du 5 avril 1979 (avec les parties supprimées ou modifiées par Bardèche lui-même). Cet entretien est lumineux ! « Devons-nous accepter […] de ne pas nous défendre contre la concurrence sauvage, déclare Bardèche, accepter le chômage, le démantèlement d’une partie de notre industrie, la dépendance à laquelle nous risquons d’être contraints ? » On croirait entendre un candidat à l’Élysée de 2012… Le sagace penseur de la rue Rataud estime que « l’Europe qu’on nous prépare ne sera qu’un bastion avancé d’un empire économique occidental dont les États-Unis seront le centre »… Il prévient qu’« il ne faut pas que l’Europe ne soit que le cadre agrandi de notre impuissance et de notre décadence », ce qu’elle est désormais. Il importe néanmoins de ne pas rejeter l’indispensable idée européenne comme le font les souverainistes nationaux. L’Europe demeure plus que jamais notre grande patrie civilisationnelle, identitaire et géopolitique. « L’Europe indépendante constitue un idéal ou plutôt un objectif », juge Bardèche avant d’ajouter, prophétique, que « la crise économique peut nous aider à la faire plus vite qu’on ne le croit ».

C’est sur la question européenne que Maurice Bardèche a conservé toute sa pertinence. Quand on lit L’œuf de Christophe Colomb (1952) ou Sparte et les Sudistes, on se régale de ses fines analyses. Bardèche réfléchissait en nationaliste français et européen. À la fin de l’opuscule, avant l’habituelle étude astrologique de Marin de Charette et après les annexes biographiques, bibliographiques, de commentaires sur Bardèche et de quelques-unes de ses citations les plus marquantes, Francis Bergeron reproduit l’entretien que lui accorda Bardèche dans Rivarol du 5 avril 1979 (avec les parties supprimées ou modifiées par Bardèche lui-même). Cet entretien est lumineux ! « Devons-nous accepter […] de ne pas nous défendre contre la concurrence sauvage, déclare Bardèche, accepter le chômage, le démantèlement d’une partie de notre industrie, la dépendance à laquelle nous risquons d’être contraints ? » On croirait entendre un candidat à l’Élysée de 2012… Le sagace penseur de la rue Rataud estime que « l’Europe qu’on nous prépare ne sera qu’un bastion avancé d’un empire économique occidental dont les États-Unis seront le centre »… Il prévient qu’« il ne faut pas que l’Europe ne soit que le cadre agrandi de notre impuissance et de notre décadence », ce qu’elle est désormais. Il importe néanmoins de ne pas rejeter l’indispensable idée européenne comme le font les souverainistes nationaux. L’Europe demeure plus que jamais notre grande patrie civilisationnelle, identitaire et géopolitique. « L’Europe indépendante constitue un idéal ou plutôt un objectif », juge Bardèche avant d’ajouter, prophétique, que « la crise économique peut nous aider à la faire plus vite qu’on ne le croit ».

Le 5 février 1982, Wies Moens quittait ce monde, lui, le principal poète moderne d’inspiration thioise et grande-néerlandaise. Il est mort en exil, pas très loin de nos frontières, à Geleen dans le Limbourg néerlandais. Dans un hebdomadaire comme “’t Pallieterke”, qui cultive l’héritage national flamand et l’idéal grand-néerlandais, Wies Moens est une référence depuis toujours. Il suffit de penser à l’historien de cet hebdomadaire, Arthur de Bruyne, aujourd’hui disparu, qui s’inscrivait dans son sillage. Pour commémorer le trentième anniversaire de la disparition de Wies Moens, “Brederode”, qui l’a connu personnellement, lui rend ici un hommage mérité. L’exilé Wies Moens n’avait-il pas dit, en 1971: “La Flandre d’aujourd’hui, l’agitation politicienne qui y sévit, l’art, la littérature, tout cela ne me dit quasi plus rien. Je ne ressens aucune envie de revenir de mon exil”?

Le 5 février 1982, Wies Moens quittait ce monde, lui, le principal poète moderne d’inspiration thioise et grande-néerlandaise. Il est mort en exil, pas très loin de nos frontières, à Geleen dans le Limbourg néerlandais. Dans un hebdomadaire comme “’t Pallieterke”, qui cultive l’héritage national flamand et l’idéal grand-néerlandais, Wies Moens est une référence depuis toujours. Il suffit de penser à l’historien de cet hebdomadaire, Arthur de Bruyne, aujourd’hui disparu, qui s’inscrivait dans son sillage. Pour commémorer le trentième anniversaire de la disparition de Wies Moens, “Brederode”, qui l’a connu personnellement, lui rend ici un hommage mérité. L’exilé Wies Moens n’avait-il pas dit, en 1971: “La Flandre d’aujourd’hui, l’agitation politicienne qui y sévit, l’art, la littérature, tout cela ne me dit quasi plus rien. Je ne ressens aucune envie de revenir de mon exil”? Wies Moens ne cessera plus jamais de nous interpeller, surtout grâce à ses premiers poèmes, dont le sublime “Laat mij mijn ziel dragen in het gedrang...”, paru dans le recueil “De Boodschap”. Il l’a écrit à 21 ans, la veille de Noël 1918, quand il était interné à la prison de Termonde, pour avoir été étudiant et activiste. Dans le deuxième ver de ce poème, il esquisse déjà tout le travail qu’il s’assigne, celui d’éduquer le peuple:

Wies Moens ne cessera plus jamais de nous interpeller, surtout grâce à ses premiers poèmes, dont le sublime “Laat mij mijn ziel dragen in het gedrang...”, paru dans le recueil “De Boodschap”. Il l’a écrit à 21 ans, la veille de Noël 1918, quand il était interné à la prison de Termonde, pour avoir été étudiant et activiste. Dans le deuxième ver de ce poème, il esquisse déjà tout le travail qu’il s’assigne, celui d’éduquer le peuple:

Ernst Jünger says in his acceptance speech for the prestigious Goethe prize in 1982, "I've had the experience that one meets the best comrades in no-man's-land. I've always been pleased with my troops (Mannschaft) in war and my readership in peace. A hand that holds a weapon with honor, holds a pen with honor. It is stronger than any atom bomb, or any rotary press." With these words Jünger bestows an honour on us, his readership. He equates us with his comrades-in-arms in times of peace, but is it a wonder after all? If you are a reader of Ernst Jünger, you must be in either one of two camps, those who consider his opus with genuine admiration or the detractors, those sceptics, "whose contribution does not equal to one blade of grass, one mosquito wing".

Ernst Jünger says in his acceptance speech for the prestigious Goethe prize in 1982, "I've had the experience that one meets the best comrades in no-man's-land. I've always been pleased with my troops (Mannschaft) in war and my readership in peace. A hand that holds a weapon with honor, holds a pen with honor. It is stronger than any atom bomb, or any rotary press." With these words Jünger bestows an honour on us, his readership. He equates us with his comrades-in-arms in times of peace, but is it a wonder after all? If you are a reader of Ernst Jünger, you must be in either one of two camps, those who consider his opus with genuine admiration or the detractors, those sceptics, "whose contribution does not equal to one blade of grass, one mosquito wing".

Né le 19 septembre 1911, William Golding peut être considéré comme le grand marginal de la littérature anglaise contemporaine. Le vécu existentiel, pour lui, a été le plus intense pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, où il a servi dans la marine —Golding était présent quand le Bismarck a coulé et au moment du débarquement anglo-américain de Normandie. Il a pris conscience de ce que les hommes pouvaient mutuellement s’infliger. Les expériences de la guerre ont conduit Golding, qui, avant les hostilités, croyait encore au perfectionnement de l’homme en tant qu’être social, à penser “que l’homme produit de la méchanceté comme les abeilles produisent du miel”. Le produit littéraire de cette grande désillusion est un roman, paru en 1954, et intitulé “Lord of the Flies” (en français: “Sa Majesté des Mouches”). Ce roman a permis à Golding d’acquérir la célébrité car il est devenu un succès international.

Né le 19 septembre 1911, William Golding peut être considéré comme le grand marginal de la littérature anglaise contemporaine. Le vécu existentiel, pour lui, a été le plus intense pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, où il a servi dans la marine —Golding était présent quand le Bismarck a coulé et au moment du débarquement anglo-américain de Normandie. Il a pris conscience de ce que les hommes pouvaient mutuellement s’infliger. Les expériences de la guerre ont conduit Golding, qui, avant les hostilités, croyait encore au perfectionnement de l’homme en tant qu’être social, à penser “que l’homme produit de la méchanceté comme les abeilles produisent du miel”. Le produit littéraire de cette grande désillusion est un roman, paru en 1954, et intitulé “Lord of the Flies” (en français: “Sa Majesté des Mouches”). Ce roman a permis à Golding d’acquérir la célébrité car il est devenu un succès international.  Dans “Lord of the Flies” —le titre, rappellons-le, est une traduction littérale du concept hébraïque de “Belzébuth”, le “Seigneur des Mouches”— le tête de porc fichée sur un pieu, que les “chasseurs” offrent en sacrifice pour conjurer le danger d’un “monstre” qui les menacerait, symbolise le Mal. En voyant cette tête de porc, entourée d’une dégoûtante nuée de mouches, Simon, qui finira martyr, reconnaît que l’homme lui-même est ce “monstre”, une créature déchue.

Dans “Lord of the Flies” —le titre, rappellons-le, est une traduction littérale du concept hébraïque de “Belzébuth”, le “Seigneur des Mouches”— le tête de porc fichée sur un pieu, que les “chasseurs” offrent en sacrifice pour conjurer le danger d’un “monstre” qui les menacerait, symbolise le Mal. En voyant cette tête de porc, entourée d’une dégoûtante nuée de mouches, Simon, qui finira martyr, reconnaît que l’homme lui-même est ce “monstre”, une créature déchue.