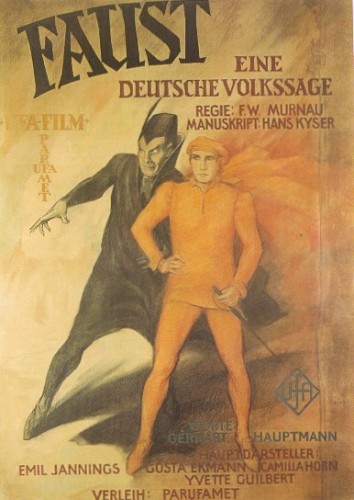

In Oswald Spengler’s terms, our European culture is the product of a “pseudomorphosis,” i.e., of the grafting of an alien mentality upon our indigenous, original, and innate mentality. Spengler calls the innate mentality “the Faustian.”

The Confrontation of the Innate and the Acquired

The alien mentality is the theocentric, “magical” outlook born in the Near East. For the magical mind, the ego bows respectfully before the divine substance like a slave before his master. Within the framework of this religiosity, the individual lets himself be guided by the divine force that he absorbs through baptism or initiation.

There is nothing comparable for the old-European Faustian spirit, says Spengler. Homo europeanus, in spite of the magic/Christian varnish covering our thinking, has a voluntarist and anthropocentric religiosity. For us, the good is not to allow oneself to be guided passively by God, but rather to affirm and carry out our own will. “To be able to choose,” this is the ultimate basis of the indigenous European religiosity. In medieval Christianity, this voluntarist religiosity shows through, piercing the crust of the imported “magism” of the Middle East.

Around the year 1000, this dynamic voluntarism appears gradually in art and literary epics, coupled with a sense of infinite space within which the Faustian self would, and can, expand. Thus to the concept of a closed space, in which the self finds itself locked, is opposed the concept of an infinite space, into which an adventurous self sallies forth.

From the “Closed” World to the Infinite Universe

According to the American philosopher Benjamin Nelson,[1] the old Hellenic sense of physis (nature), with all the dynamism this implies, triumphed at the end of the 13th century, thanks to Averroism, which transmitted the empirical wisdom of the Greeks (and of Aristotle in particular) to the West. Gradually, Europe passed from the “closed world” to the infinite universe. Empiricism and nominalism supplanted a Scholasticism that had been entirely discursive, self-referential, and self-enclosed. The Renaissance, following Copernicus and Bruno (the tragic martyr of Campo dei Fiori), renounced geocentrism, making it safe to proclaim that the universe is infinite, an essentially Faustian intuition according to Spengler’s criteria.

In the second volume of his History of Western Thought, Jean-François Revel, who formerly officiated at Point and unfortunately illustrated the Americanocentric occidentalist ideology, writes quite pertinently: “It is easy to understand that the eternity and infinity of the universe announced by Bruno could have had, on the cultivated men of the time, the traumatizing effect of passing from life in the womb into the vast and cruel draft of an icy and unbounded vortex.”[2]

The “magic” fear, the anguish caused by the collapse of the comforting certitude of geocentrism, caused the cruel death of Bruno, that would become, all told, a terrifying apotheosis . . . Nothing could ever refute heliocentrism, or the theory of the infinitude of sidereal spaces. Pascal would say, in resignation, with the accent of regret: “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”

From Theocratic Logos to Fixed Reason

To replace magical thought’s “theocratic logos,” the growing and triumphant bourgeois thought would elaborate a thought centered on reason, an abstract reason before which it is necessary to bow, like the Near Easterner bows before his god. The “bourgeois” student of this “petty little reason,” virtuous and calculating, anxious to suppress the impulses of his soul or his spirit, thus finds a comfortable finitude, a closed off and secured space. The rationalism of this virtuous human type is not the adventurous, audacious, ascetic, and creative rationalism described by Max Weber[3] which educates the inner man precisely to face the infinitude affirmed by Giordano Bruno.[4]

From the end of the Renaissance, Two Modernities are Juxtaposed

The petty rationalism denounced by Sombart[5] dominates the cities by rigidifying political thought, by restricting constructive activist impulses. The genuinely Faustian and conquering rationalism described by Max Weber would propel European humanity outside its initial territorial limits, giving the main impulse to all sciences of the concrete.

From the end of the Renaissance, we thus discover, on the one hand, a rigid and moralistic modernity, without vitality, and, on the other hand, an adventurous, conquering, creative modernity, just as we are today on the threshold of a soft post-modernity or of a vibrant post-modernity, self-assured and potentially innovative. By recognizing the ambiguity of the terms “rationalism,” “rationality,” “modernity,” and “post-modernity,” we enter one level of the domain of political ideologies, even militant Weltanschauungen.

The rationalization glutted with moral arrogance described by Sombart in his famous portrait of the “bourgeois” generates the soft and sentimental messianisms, the great tranquillizing narratives of contemporary ideologies. The conquering rationalization described by Max Weber causes the great scientific discoveries and the methodical spirit, the ingenious refinement of the conduct of life and increasing mastery of the external world.

This conquering rationalization also has its dark side: It disenchants the world, drains it, excessively schematizes it. While specializing in one or another domain of technology, science, or the spirit, while being totally invested there, the “Faustians” of Europe and North America often lead to a leveling of values, a relativism that tends to mediocrity because it makes us lose the feeling of the sublime, of the telluric mystique, and increasingly isolates individuals. In our century, the rationality lauded by Weber, if positive at the beginning, collapsed into quantitativist and mechanized Americanism that instinctively led by way of compensation, to the spiritual supplement of religious charlatanism combining the most delirious proselytism and sniveling religiosity.

Such is the fate of “Faustianism” when severed from its mythic foundations, of its memory of the most ancient, of its deepest and most fertile soil. This caesura is unquestionably the result of pseudomorphosis, the “magian” graft on the Faustian/European trunk, a graft that failed. “Magianism” could not immobilize the perpetual Faustian drive; it has—and this is more dangerous—cut it off from its myths and memory, condemned it to sterility and dessication, as noted by Valéry, Rilke, Duhamel, Céline, Drieu, Morand, Maurois, Heidegger, or Abellio.

Conquering Rationality, Moralizing Rationality, the Dialectic of Enlightenment, the “Grand Narratives” of Lyotard

Conquering rationality, if it is torn away from its founding myths, from its ethno-identitarian ground, its Indo-European matrix, falls—even after assaults that are impetuous, inert, emptied of substance—into the snares of calculating petty rationalism and into the callow ideology of the “Grand Narratives” of rationalism and the end of ideology. For Jean-François Lyotard, “modernity” in Europe is essentially the “Grand Narrative” of the Enlightenment, in which the heroes of knowledge work peacefully and morally toward an ethico-political happy ending: universal peace, where no antagonism will remain.[6] The “modernity” of Lyotard corresponds to the famous “Dialectic of the Enlightenment” of Horkheimer and Adorno, leaders of famous “Frankfurt School.”[7] In their optic, the work of the man of science or the action of the politician, must be submitted to a rational reason, an ethical corpus, a fixed and immutable moral authority, to a catechism that slows down their drive, that limits their Faustian ardor. For Lyotard, the end of modernity, thus the advent of “post-modernity,” is incredulity—progressive, cunning, fatalistic, ironic, mocking—with regard to this metanarrative.

Incredulity also means a possible return of the Dionysian, the irrational, the carnal, the turbid, and disconcerting areas of the human soul revealed by Bataille or Caillois, as envisaged and hoped by professor Maffesoli,[8] of the University of Strasbourg, and the German Bergfleth,[9] a young nonconformist philosopher; that is to say, it is equally possible that we will see a return of the Faustian spirit, a spirit comparable with that which bequeathed us the blazing Gothic, of a conquering rationality which has reconnected with its old European dynamic mythology, as Guillaume Faye explains in Europe and Modernity.[10]

Notes

1. Benjamin Nelson, Der Ursprung der Moderne, Vergleichende Studien zum Zivilisationsprozess [The Origin of Modernity: Comparative Studies of the Civilization Process] (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1986).

2. Jean-François Revel, Histoire de la pensée occidentale [History of Western Thought], vol. 2, La philosophie pendant la science (XVe, XVIe et XVIIe siècles) [Philosophy and Science (Fifteenth-, Sixteenth-, and Seventeenth-Centuries)] (Paris: Stock, 1970). Cf. also the masterwork of Alexandre Koyré, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1957).

3. Cf. Julien Freund, Max Weber (Paris: P.U.F., 1969).

4. Paul-Henri Michel, La cosmologie de Giordano Bruno [The Cosmology of Giordano Bruno] (Paris: Hermann, 1962).

5. Cf. essentially: Werner Sombart, Le Bourgeois. Contribution à l’histoire morale et intellectuelle de l’homme économique moderne [The Bourgeois: Contribution to the Moral and Intellectual History of Modern Economic Man] (Paris: Payot, 1966).

6. Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

7. Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adomo, The Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002). Cf. also Pierre Zima, L’École de Francfort. Dialectique de la particularité [The Frankfurt School: Dialectic of Particularity] (Paris: Éditions Universitaires, 1974). Michel Crozon, “Interroger Horkheimer” [“Interrogating Horkheimer”] and Arno Victor Nielsen, “Adorno, le travail artistique de la raison” [“Adorno: The Artistic Work of Reason”], Esprit, May 1978.

8. Cf. chiefly Michel Maffesoli, L’ombre de Dionysos: Contribution à une sociologie de l’orgie [The Shadow of Dionysus: Contribution to a Sociology of the Orgy] (Méridiens, 1982). Pierre Brader, “Michel Maffesoli: saluons le grand retour de Dionysos” [Michel Maffesoli: Let us Greet the Great return of Dionysos], Magazine-Hebdo no. 54 (September 21, 1984).

9. Cf. Gerd Bergfleth et al., Zur Kritik der Palavernden Aufklärung [Toward a Critique of Palavering Reason] (Munich: Matthes & Seitz, 1984). In this remarkable little anthology, Bergfleth published four texts deadly to the “moderno-Frankfurtist” routine: (1) “Zehn Thesen zur Vernunftkritik” [“Ten Theses on the Critique of Reason”]; (2) “Der geschundene Marsyas” [“The Abuse of Marsyas”]; (3) “Über linke Ironie” [“On Leftist Irony”]; (4) “Die zynische Aufklärung” [“The Cynical Enlightnement”]. Cf. also R. Steuckers, “G. Bergfleth: enfant terrible de la scène philosophique allemande” [“G. Bergfleth: enfant terrible of the German philosophical scene”], Vouloir no. 27 (March 1986). In the same issue, see also M. Kamp, “Bergfleth: critique de la raison palabrante” [“Bergfleth: Critique of Palavering Reason”] and “Une apologie de la révolte contre les programmes insipides de la révolution conformiste” [“An Apology for the Revolt against the Insipid Programs of the Conformist Revolution”]. See also M. Froissard, “Révolte, irrationnel, cosmicité et . . . pseudo-antisémitisme,” [“Revolt, irrationality, cosmicity and . . . pseudo-anti-semitism”], Vouloir nos. 40–42 (July–August 1987).

10. Guillaume Faye, Europe et Modernité [Europe and Modernity] (Méry/Liège: Eurograf, 1985).

Postmodern Challenges:

Between Faust & Narcissus, Part 2

Once the Enlightenment metanarrative was established—“encysted”—in the Western mind, the great secular ideologies progressively appeared: liberalism, with its idolatry of the “invisible hand,”[1] and Marxism, with its strong determinism and metaphysics of history, contested at the dawn of the 20th century by Georges Sorel, the most sublime figure of European militant socialism.[2] Following Giorgio Locchi[3]—who occasionally calls the metanarrative “ideology” or “science”—we think that this complex “metanarrative/ideology/science” no longer rules by consensus but by constraint, inasmuch as there is muted resistance (especially in art and music[4]) or a general disuse of the metanarrative as one of the tools of legitimation.

The liberal-Enlightenment metanarrative persists by dint of force and propaganda. But in the sphere of thought, poetry, music, art, or letters, this metanarrative says and inspires nothing. It has not moved a great mind for 100 or 150 years. Already at the end of the 19th century, literary modernism expressed a diversity of languages, a heterogeneity of elements, a kind of disordered chaos that the “physiologist” Nietzsche analyzed[5] and that Hugo von Hoffmannstahl called die Welt der Bezuge (the world of relations).

These omnipresent interrelations and overdeterminations show us that the world is not explained by a simple, neat and tidy story, nor does it submit itself to the rule of a disincarnated moral authority. Better: they show us that our cities, our people, cannot express all their vital potentialities within the framework of an ideology given and instituted once and for all for everyone, nor can we indefinitely preserve the resulting institutions (the doctrinal body derived from the “metanarrative of the Enlightenment”).

The anachronistic presence of the metanarrative constitutes a brake on the development of our continent in all fields: science (data-processing and biotechnology[6]), economics (the support of liberal dogmas within the EEC), military (the fetishism of a bipolar world and servility toward the United States, paradoxically an economic enemy), cultural (media bludgeoning in favor of a cosmopolitanism that eliminates Faustian specificity and aims at the advent of a large convivial global village, run on the principles of the “cold society” in the manner of the Bororos dear to Lévi-Strauss[7]).

The Rejection of Neo-Ruralism, Neo-Pastoralism . . .

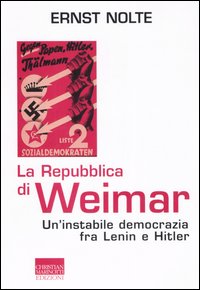

The confused disorder of literary modernism at the end of the 19th century had a positive aspect: its role was to be the magma that, gradually, becomes the creator of a new Faustian assault.[8] It is Weimar—specifically, the Weimar-arena of the creative and fertile confrontation of expressionism,[9] neo-Marxism, and the “conservative revolution”[10]—that bequeathed us, with Ernst Jünger, an idea of “post-metanarrative” modernity (or post-modernity, if one calls “modernity” the Dialectic of the Enlightenment, subsequently theorized by the Frankfurt School). Modernism, with the confusion it inaugurates, due to the progressive abandonment the pseudo-science of the Enlightenment, corresponds somewhat to the nihilism observed by Nietzsche. Nihilism must be surmounted, exceeded, but not by a sentimental return, however denied, to a completed past. Nihilism is not surpassed by theatrical Wagnerism, Nietzsche fulminated, just as today the foundering of the Marxist “Grand Narrative” is not surpassed by a pseudo-rustic neoprimitivism.[11]

In Jünger—the Jünger of In Storms of Steel, The Worker, and Eumeswil—one finds no reference to the mysticism of the soil: only a sober admiration for the perennialness of the peasant, indifferent to historical upheavals. Jünger tells us of the need for balance: if there is a total refusal of the rural, of the soil, of the stabilizing dimension of Heimat, constructivist Faustian futurism will no longer have a base, a point of departure, a fallback option. On the other hand, if the accent is placed too much on the initial base, the launching point, on the ecological niche that gives rise to the Faustian people, then they are wrapped in a cocoon and deprived of universal influence, rendered blind to the call of the world, prevented from springing towards reality in all its plenitude, the “exotic” included. The timid return to the homeland robs Faustianism of its force of diffusion and relegates its “human vessels” to the level of the “eternal ahistoric peasants” described by Spengler and Eliade.[12] Balance consists in drawing in (from the depths of the original soil) and diffusing out (towards the outside world).

In spite of all nostalgia for the “organic,” rural, or pastoral—in spite of the serene, idyllic, aesthetic beauty that recommend Horace or Virgil—Technology and Work are from now on the essences of our post-nihilist world. Nothing escapes any longer from technology, technicality, mechanics, or the machine: neither the peasant who plows with his tractor nor the priest who plugs in a microphone to give more impact to his homily.

The era of “Technology”

Technology mobilizes totally (Total Mobilmachung) and thrusts the individual into an unsettling infinitude where we are nothing more than interchangeable cogs. The machine gun, notes the warrior Jünger, mows down the brave and the cowardly with perfect equality, as in the total material war inaugurated in 1917 in the tank battles of the French front. The Faustian “Ego” loses its intraversion and drowns in a ceaseless vortex of activity. This Ego, having fashioned the stone lacework and spires of the flamboyant Gothic, has fallen into American quantitativism or, confused and hesitant, has embraced the 20th century’s flood of information, its avalanche of concrete facts. It was our nihilism, our frozen indecision due to an exacerbated subjectivism, that mired us in the messy mud of facts.

By crossing the “line,” as Heidegger and Jünger say,[13] the Faustian monad (about which Leibniz[14] spoke) cancels its subjectivism and finds pure power, pure dynamism, in the universe of Technology. With the Jüngerian approach, the circle is closed again: as the closed universe of “magism” was replaced by the inauthentic little world of the bourgeois—sedentary, timid, embalmed in his utilitarian sphere—so the dynamic “Faustian” universe is replaced with a Technological arena, stripped this time of all subjectivism.

Jüngerian Technology sweeps away the false modernity of the Enlightenment metanarrative, the hesitation of late 19th century literary modernism, and the trompe-l’oeil of Wagnerism and neo-pastoralism. But this Jüngerian modernity, perpetually misunderstood since the publication of Der Arbeiter [The Worker] in 1932, remains a dead letter.

Notes

1. On the theological foundation of the doctrine of the “invisible hand” see Hans Albert, “Modell-Platonismus. Der neoklassische Stil des ökonomischen Denkens in kritischer Beleuchtung” [“Model Platonism: The Neoclassical Style of Economic Thought in Critical Elucidation”], in Ernst Topitsch, ed., Logik der Sozialwissenschaften [Logic of Social Science] (Köln/Berlin: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1971).

2. There is abundant French literature on Georges Sorel. Nevertheless, it is deplorable that a biography and analysis as valuable as Michael Freund’s has not been translated: Michael Freund, Georges Sorel, Der revolutionäre Konservatismus [Georges Sorel: Revolutionary Conservatism] (Frankfurt a.M.: Vittorio Klostermann, 1972).

3. Cf. G. Locchi, “Histoire et société: critique de Lévi-Strauss” [“History and Society: Critique of Lévi-Strauss”], Nouvelle Ecole, no. 17 (March 1972) and “L’histoire” [“History”], Nouvelle Ecole, nos. 27–28 (January 1976).

4. Cf. G. Locchi, “L’idée de la musique’ et le temps de l’histoire” [“The ‘Idea of Music’ and the Times of History”], Nouvelle Ecole, no. 30 (November 1978) and Vincent Samson, “Musique, métaphysique et destin” [“Music, Metaphysics, and Destiny”], Orientations, no. 9 (September 1987).

5. Cf. Helmut Pfotenhauer, Die Kunst als Physiologie: Nietzsches äesthetische Theorie und literarische Produktion [Art as Physiology: Nietzsche’s Aesthetic Theory and Literary Production] (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 1985). Cf. on Pfotenhauer’s book: Robert Steuckers, “Regards nouveaux sur Nietzsche” [“New Views of Nietzsche”], Orientations, no. 9.

6. Biotechnology and the most recent biocybernetic innovations, when applied to the operation of human society, fundamentally call into question the mechanistic theoretical foundations of the “Grand Narrative” of the Enlightenment. Less rigid, more flexible laws, because adapted to the deep drives of human psychology and physiology, would restore a dynamism to our societies and put them in tune with technological innovations. The Grand Narrative—which is always around, in spite of its anachronism—blocks the evolution of our societies; Habermas’ thought, which categorically refuses to fall in step with the epistemological discoveries of Konrad Lorenz, for example, illustrates perfectly the genuinely reactionary rigidity of the neo-Enlightenment in its Frankfurtist and current neo-liberal derivations. To understand the shift that is taking place regardless of the liberal-Frankfurtist reaction, see the work of the German bio-cybernetician Frederic Vester: (1) Unsere Welt—ein vernetztes System, dtv, no. l0,118, 2nd ed. (München, 1983) and (2) Neuland des Denkens. Vom technokratischen zum kybernetischen Zeitalter (Stuttgart: DVA, 1980). The restoration of holist (ganzheitlich) social thought by modern biology is discussed, most notably, in Gilbert Probst, Selbst-Organisation, Ordnungsprozesse in sozialen Systemen aus ganzheitlicher Sicht (Berlin: Paul Parey, 1987).

7. G. Locchi, “L’idée de la musique’ et le temps de l’histoire.”

8. To tackle the question of the literary modernism in the 19th century, see: M. Bradbury, J. McFarlane, eds., Modernism 1890–1930 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976).

9. Cf. Paul Raabe, ed., Expressionismus. Der Kampf um eine literarische Bewegung (Zürich: Arche, 1987)—A useful anthology of the principal expressionist manifestos.

10. Armin Mohler, La Révolution Conservatrice en Allemagne, 1918–1932 (Puiseaux: Pardès, 1993). See mainly text A3 entitled “Leitbilder” (“Guiding Ideas”).

11. Cf. Gérard Raulet, “Mantism and the Post-Modern Conditions” and Claude Karnoouh, “The Lost Paradise of Regionalism: The Crisis of Post-Modernity in France,” Telos, no. 67 (March 1986).

12. Cf. Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, 2 vols., trans. Charles Francis Atkinson (New York: Knopf, 1926) for the definition of the “ahistorical peasant” see vol. 2. Cf. Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, trans. Willard R. Trask (San Diego: Harcourt, 1959). For the place of this vision of the “peasant” in the contemporary controversy regarding neo-paganism, see: Richard Faber, “Einleitung: ‘Pagan’ und Neo-Paganismus. Versuch einer Begriffsklärung,” in Richard Faber and Renate Schlesier, Die Restauration der Götter: Antike Religion und Neo-Paganismus [The Restoration of the Gods: Ancient Religion and Neo-Paganism] (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 1986), 10–25. This text was reviewed in French by Robert Steuckers, “Le paganisme vu de Berlin” [“Paganism as Seen in Berlin”], Vouloir no. 28–29, April 1986, pp. 5–7.

13. On the question of the “line” in Jünger and Heidegger, cf. W. Kaempfer, Ernst Jünger, Sammlung Metzler, Band 20l (Stuttgart, Metzler, 1981), pp. 119–29. Cf also J. Evola, “Devant le ‘mur du temps’” [“Before the ‘Wall of Time’”] in Explorations: Hommes et problems [Explorations: Men and Problems], trans. Philippe Baillet (Puiseaux: Pardès, 1989), pp. 183–94. Let us take this opportunity to recall that, contrary to the generally accepted idea, Heidegger does not reject technology in a reactionary manner, nor does he regard it as dangerous in itself. The danger is due to the failure to think of the mystery of its essence, preventing man from returning to a more originary unconcealment and from hearing the call of a more primordial truth. If the age of technology seems to be the final form of the Oblivion of Being, where the anxiety suitable to thought appears as an absence of anxiety in the securing and the objectification of being, it is also from this extreme danger that the possibility of another beginning is thinkable once the metaphysics of subjectivity is completed.

14. To assess the importance of Leibniz in the development of German organic thought, cf. F. M. Barnard, Herder’s Social and Political Thought: From Enlightenment to Nationalism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), 10–12.

Postmodern Challenges:

Between Faust & Narcissus, Part 3

In 1945, the tone of ideological debate was set by the victorious ideologies. We could choose American liberalism (the ideology of Mr. Babbitt) or Marxism, an allegedly de-bourgeoisfied version of the metanarrative. The Grand Narrative took charge, hunted down any “irrationalist” philosophy or movement,[1] set up a thought police, and finally, by brandishing the bogeyman of rampant barbarism, inaugurated an utterly vacuous era.

Sartre and his fashionable Parisian existentialism must be analyzed in the light of this restoration. Sartre, faithful to his “atheism,” his refusal to privilege one value, did not believe in the foundations of liberalism or Marxism. Ultimately, he did not set up the metanarrative (in its most recent version, the vulgar Marxism of the Communist parties[2]) as a truth but as an “inescapable”categorical imperative for which one must militate if one does not want to be a “bastard,” i.e., one of these contemptible beings who venerate “petrified orders.”[3] It is the whole paradox of Sartreanism: on the one hand, it exhorts us not to adore “petrified orders,” which is properly Faustian, and, on another side, it orders us to “magically” adore a “petrified order” of vulgar Marxism, already unhorsed by Sombart or De Man. Thus in the Fifties, the golden age of Sartreanism, the consensus is indeed a moral constraint, an obligation dictated by increasingly mediatized thought. But a consensus achieved by constraint, by an obligation to believe without discussion, is not an eternal consensus. Hence the contemporary oblivion of Sartreanism, with its excesses and its exaggerations.

The Revolutionary Anti-Humanism of May 1968

With May ’68, the phenomenon of a generation, “humanism,” the current label of the metanarrative, was battered and broken by French interpretations of Nietzsche, Marx, and Heidegger.[4] In the wake of the student revolt, academics and popularizers alike proclaimed humanism a “petite-bourgeois” illusion. Against the West, the geopolitical vessel of the Enlightenment metanarrative, the rebels of ’68 played at mounting the barricades, taking sides, sometimes with a naive romanticism, in all the fights of the 1970s: Spartan Vietnam against American imperialism, Latin-American guerillas (“Ché”), the Basque separatists, the patriotic Irish, or the Palestinians.

Their Faustian feistiness, unable to be expressed though autochthonous models, was transposed toward the exotic: Asia, Arabia, Africa, or India. May ’68, in itself, by its resolute anchorage in Grand Politics, by its guerilla ethos, by its fighting option, in spite of everything took on a far more important dimension than the strained blockage of Sartreanism or the great regression of contemporary neo-liberalism. On the right, Jean Cau, in writing his beautiful book on Che Guevara[5] understood this issue perfectly, whereas the right, which is as fixated on its dogmas and memories as the left, had not wanted to see.

With the generation of ’68—combative and politicized, conscious of the planet’s great economic geopolitical issues—the last historical fires burned in the French public spirit before the great rise of post-history and post-politics represented by the narcissism of contemporary neoliberalism.

The Translation of the Writings of the “Frankfurt School” announces the Advent of Neo-Liberal Narcissism

The first phase of the neo-liberal attack against the political anti-humanism of May ’68 was the rediscovery of the writings of the Frankfurt School: born in Germany before the advent of National Socialism, matured during the California exile of Adorno, Horkheimer, and Marcuse, and set up as an object of veneration in post-war West Germany. In Dialektik der Aufklärung, a small and concise book that is fundamental to understanding the dynamics of our time, Horkheimer and Adorno claim that there are two “reasons” in Western thought that, in the wake of Spengler and Sombart, we are tempted to name “Faustian reason” and “magical reason.” The former, for the two old exiles in California, is the negative pole of the “reason complex” in Western civilization: this reason is purely “instrumental”; it is used to increase the personal power of those who use it. It is scientific reason, the reason that tames the forces of the universe and puts them in the service of a leader or a people, a party or state. Thus, according to Herbert Marcuse, it is Promethean, not Narcissistic/Orphic.[6] For Horkheimer, Adorno, and Marcuse, this is the kind of rationality that Max Weber theorized.

On the other hand, “magical reason,” according to our Spenglerian genealogical terminology, is, broadly speaking, the reason of Lyotard’s metanarrative. It is a moral authority that dictates ethical conduct, allergic to any expression of power, and thus to any manifestation of the essence of politics.[7] In France, the rediscovery of the Horkheimer-Adorno theory of reason near the end of the 1970s inaugurated the era of depoliticization, which, by substituting generalized disconnection for concrete and tangible history, led to the “era of the vacuum” described so well by Grenoble Professor Gilles Lipovetsky.[8] Following the militant effervescence of May ’68 came a generation whose mental attitudes are characterized quite justly by Lipovetsky as apathy, indifference (also to the metanarrative in its crude form), desertion (of the political parties, especially of the Communist Party), desyndicalisation, narcissism, etc. For Lipovetsky, this generalized resignation and abdication constitutes a golden opportunity. It is the guarantee, he says, that violence will recede, and thus no “totalitarianism,” red, black, or brown, will be able to seize power. This psychological easy-goingness, together with a narcissistic indifference to others, constitutes the true “post-modern” age.

There are Various Possible Definitions of “Post-Modernity”

On the other hand, if we perceive—contrary to Lipovetsky’s usage—“modernity” or “modernism” as expressions of the metanarrative, thus as brakes on Faustian energy, post-modernity will necessarily be a return to the political, a rejection of para-magical creationism and anti-political suspicion that emerged after May 68, in the wake of speculations on “instrumental reason” and “objective reason” described by Horkheimer and Adorno.

The complexity of the “post-modern” situation makes it impossible to give one and only one definition of “post-modernity.” There is not one post-modernity that can lay claim to exclusivity. On the threshold of the 21st century, various post-modernities lie fallow, side by side, diverse potential post-modern social models, each based on fundamentally antagonistic values fundamentally antagonistic, primed to clash. These post-modernities differ—in their language or their “look”—from the ideologies that preceded them; they are nevertheless united with the eternal, immemorial, values that lie beneath them. As politics enters the historical sphere through binary confrontations, clashes of opposing clans and the exclusion of minorities, dare to evoke the possible dichotomy of the future: a neo-liberal, Western, American and American-like post-modernity versus a shining Faustian and Nietzschean post-modernity.

The “Moral Generation” & the “Era of the Vacuum”

This neo-liberal post-modernity was proclaimed triumphantly, with Messianic delirium, by Laurent Joffrin in his assessment of the student revolt of December 1986 (Un coup de jeune [A Coup of Youth], Arlea, 1987). For Joffrin, who predicted[9] the death of the hard left, of militant proletarianism, December ’86 is the harbinger of a “moral generation,” combining in one mentality soft leftism, lazy-minded collectivism, and neo-liberal, narcissistic, and post-political selfishness: the social model of this hedonistic society centered on commercial praxis, that Lipovetsky described as the era of the vacuum. A political vacuum, an intellectual vacuum, and a post-historical desert: these are the characteristics of the blocked space, the closed horizon characteristic of contemporary neo-liberalism. This post-modernity constitutes a troubling impediment to the greater Europe that must emerge so that we have a viable future and arrest the slow decay announced by massive unemployment and declining demographics spreading devastation under the wan light of consumerist illusions, the big lies of advertisers, and the neon signs praising the merits of a Japanese photocopier or an American airline.

On the other hand, the post-modernity that rejects the old anti-political metanarrative of the Enlightenment, with its metamorphoses and metastases; that affirms the insolence of a Nietzsche or the metallic ideal of a Jünger; that crosses the “line,” as Heidegger exhorts, leaving behind the sterile dandyism of nihilistic times; the post-modernity that rallies the adventurous to a daring political program concretely implying the rejection of the existing power blocs, the construction of an autarkic Eurocentric economy, while fighting savagely and without concessions against all old-fashioned religions and ideologies, by developing the main axis of a diplomacy independent of Washington; the post-modernity that will carry out this voluntary program and negate the negations of post-history—this post-modernity will have our full adherence.

In this brief essay, I wanted to prove that there is a continuity in the confrontation of the “Faustian” and “magian” mentalities, and that this antagonistic continuity is reflected in the current debate on post-modernities. The American-centered West is the realm of “magianisms,” with its cosmopolitanism and authoritarian sects.[10] Europe, the heiress of a Faustianism much abused by “magian” thought, will reassert herself with a post-modernity that will recapitulate the inexpressible themes, recurring but always new, of the Faustianness intrinsic to the European soul.

Notes

1. The classic among classics in the condemnation of “irrationalism” is the summa of György Lukács, The Destruction of Reason, 2 vols. (1954). This book aims to be a kind of Discourse on Method for the dialectic of Enlightenment-Counter-Enlightenment, rationalism-irrationalism. Through a technique of amalgamation that bears a passing resemblance to a Stalinist pamphlet, broad sectors of German and European culture, from Schelling to neo-Thomism, are blamed for having prepared and supported the Nazi phenomenon. It is a paranoiac vision of culture.

2. To understand the fundamental irrationality of Sartre’s Communism, one should read Thomas Molnar, Sartre, philosophie de la contestation (Paris: La Table Ronde, 1969). In English: Sartre: Ideologue of Our Time (New York : Funk & Wagnalls, 1968).

3. Cf. R.-M. Alberes, Jean-Paul Sartre (Paris: Éditions Universitaires, 1964), 54–71.

4. In France, the polemic aiming at a final rejection of the anti-humanism of ’68 and its Nietzschean, Marxist, and Heideggerian philosophical foundations is found in Luc Ferry and Alain Renaut, French Philosophy of the Sixties: An Essay on Anti-Humanism, trans. Mary H. S. Cattani (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1990) and its appendix ’68–’86. Itinéraires de l’individu [’68-’86: Routes of the Individual] (Paris: Gallimard, 1987). Contrary to the theses defended in first of these two works, Guy Hocquenghem in Lettre ouverte à ceux qui sont passés du col Mao au Rotary Club [Open Letter to those Went from Mao Jackets to the Rotary Club] (Paris: Albin Michel, 1986) deplored the assimilation of the hyper-politicism of the generation of 1968 into the contemporary neo-liberal wave. From a definitely polemical point of view and with the aim of restoring debate, such as it is, in the field of philosophical abstraction, one should read Eddy Borms, Humanisme—kritiek in het hedendaagse Franse denken [Humanism: Critique in Contemporary French Thought (Nijmegen: SUN, 1986).

5. Jean Cau, the former secretary of Jean-Paul Sartre, now classified as a polemist of the “right,” who delights in challenging the manias and obsessions of intellectual conformists, did not hesitate to pay homage to Che Guevara and to devote a book to him. The “radicals” of the bourgeois accused him of “body snatching”! Cau’s rigid right-wing admirers did not appreciate his message either. For them, the Nicaraguan Sandinistas, who nevertheless admired Abel Bonnard and the American “fascist” Lawrence Dennis, are emanations of the Evil One.

6. Cf. A. Vergez, Marcuse (Paris: P.U.F., 1970).

7. Julien Freund, Qu’est-ce que la politique? [What is Politics?] (Paris: Seuil, 1967). Cf Guillaume Faye, “La problématique moderne de la raison ou la querelle de la rationalité” [“The Modern Problem of Reason or the Quarrel of Rationality”] Nouvelle Ecole no. 41, November 1984.

8. G. Lipovetsky, L’ère du vide: Essais sur l’individualisme contemporain [The Era of the Vacuum: Essays on contemporary individualism] (Paris: Gallimard, 1983). Shortly after this essay was written, Gilles Lipovetsky published a second book that reinforced its viewpoint: L’Empire de l’éphémère: La mode et son destin dans les sociétés modernes [Empire of the Ephemeral: Fashion and its Destiny in Modern Societies] (Paris: Gallimard, 1987). Almost simultaneously François-Bernard Huyghe and Pierre Barbès protested against this “narcissistic” option in La soft-idéologie [The Soft Ideology] (Paris: Laffont, 1987). Needless to say, my views are close to those of the last two writers.

9. Cf. Laurent Joffrin, La gauche en voie de disparition: Comment changer sans trahir? [The Left in the Process of Disappearance: How to Change without Betrayal?] (Paris: Seuil, 1984).

10. Cf. Furio Colombo, Il dio d’America: Religione, ribellione e nuova destra [The God of America: Religion, Rebellion, and the New Right] (Milano: Arnoldo Mondadori, 1983).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Perché lo strumento tecnico possa essere ad-operato dall’uomo, è necessario che questi faccia propria precisamente la razionalità strumentale. Se infatti l’uomo adotta la tecnica come strumento, non ha bisogno di mettere in gioco tutte quelle qualità che lo distinguono dagli altri uomini. Secondo una tradizione di pensiero che si impone già prima di

Perché lo strumento tecnico possa essere ad-operato dall’uomo, è necessario che questi faccia propria precisamente la razionalità strumentale. Se infatti l’uomo adotta la tecnica come strumento, non ha bisogno di mettere in gioco tutte quelle qualità che lo distinguono dagli altri uomini. Secondo una tradizione di pensiero che si impone già prima di

Sans doute le grand romancier trouva-t-il aussi dans le livre du philosophe, comme le remarque José Luis Goyenna dans son intéressante (quoique pleine de fautes) préface, en plus d'images étonnantes bien propres à enthousiasmer l'écrivain, une authentique philosophie de la liberté comme accomplissement métaphysique du moi qui, à la différence de celle de Sartre qualifiée par l'auteur d'Ultramarine de «pensée de seconde main» (2), ne se dépêcherait pas bien vite de déposer aux pieds de l'idole le fardeau trop pesant, enchaînant ainsi la liberté à la seule discipline stupide des masses. Tout lecteur de La révolte des masses aime je crois, en tout premier lieu, l'écriture de ce livre érudit, pressé, menaçant, parfois prodigieusement lucide et même, osons ce mot tombé dans l'ornière journalistique, prophétique.

Sans doute le grand romancier trouva-t-il aussi dans le livre du philosophe, comme le remarque José Luis Goyenna dans son intéressante (quoique pleine de fautes) préface, en plus d'images étonnantes bien propres à enthousiasmer l'écrivain, une authentique philosophie de la liberté comme accomplissement métaphysique du moi qui, à la différence de celle de Sartre qualifiée par l'auteur d'Ultramarine de «pensée de seconde main» (2), ne se dépêcherait pas bien vite de déposer aux pieds de l'idole le fardeau trop pesant, enchaînant ainsi la liberté à la seule discipline stupide des masses. Tout lecteur de La révolte des masses aime je crois, en tout premier lieu, l'écriture de ce livre érudit, pressé, menaçant, parfois prodigieusement lucide et même, osons ce mot tombé dans l'ornière journalistique, prophétique.

La noticia del apresurado y dichoso financiero yanqui, nos trae al recuerdo la figura del gran economista alemán profesor Werner Sombart, que ejerció docencia, justamente sonada, como profesor de Economía Política, en la Universidad de Berlín, y cuya obra es una verdadera pena que aun no haya sido traducida —que sepamos— al castellano.

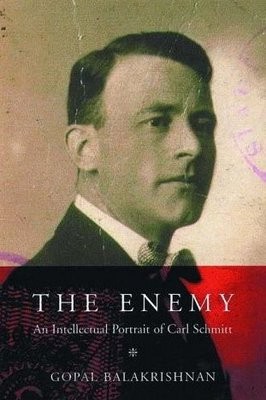

La noticia del apresurado y dichoso financiero yanqui, nos trae al recuerdo la figura del gran economista alemán profesor Werner Sombart, que ejerció docencia, justamente sonada, como profesor de Economía Política, en la Universidad de Berlín, y cuya obra es una verdadera pena que aun no haya sido traducida —que sepamos— al castellano. Aucun bricolage néo-kantien ne pourra longtemps masquer le nihilisme démocratique et la vacuité moderne – d’autant moins d’ailleurs que cet excellent lecteur de Kant que fut Jacobi diagnostiqua parmi les premiers la maladie nihiliste que les trois Critiques incubèrent fort peu de temps avant qu’elle ne se déclare. L’Europe, c’est-à-dire très exactement la chrétienté selon Novalis, ne pourra réagir qu’en opposant son antidote souverain : le catholicisme. On peut prendre la question dans tous les sens, ce n’est qu’en réactivant l’interrogation théologico-politique, comme l’ont compris Joseph de Maistre, Donoso Cortès, Carl Schmitt, mais aussi Leo Strauss et Jacob Taubes d’un point de vue juif, donc, en dernière analyse, chrétien, que l’on pourra faire rendre gorge au néant. L’adhésion très temporaire de Carl Schmitt au NSDAP (après d’ailleurs qu’il a mis tout Weimar en garde, dès 1932, sur le danger national-socialiste et l’urgence à interdire, par l’article 48 de la Constitution, les partis communiste et nazi) ne s’explique là encore que par la mystique au sens de Péguy – et non la politique: le catholique conséquent croyant en l’existence de l’univers invisible et donc des mauvais anges peut être abusé par les ruses et les séductions de l’Ennemi (au sens schmittien, d’une certaine façon, nous y reviendrons) jusqu’à prendre des vessies pour des lanternes et le point culminant du nihilisme actif (et non passif, celui-ci relevant de la juridiction démocratique) pour le paroxysme de la vérité. À la lettre oxymorique, il côtoie toujours les cimes des abîmes, comme un abbé Donissan ou un curé d’Ambricourt et à la différence de n’importe quel démocrate-chrétien. Les enfileurs de perles et les analystes du rien, hommes du ni oui ni non, font aujourd’hui écran au théologien politique, homme des affirmations absolues et des négations souveraines fidèle à l’Évangile («Que votre oui soit oui, que votre non soit non», Mt 5, 37) alors que ce dernier est évidemment requis par la tiédeur infernale. Le libéralisme, hostile à toute forme de vision, ne voit bien entendu se profiler aucune eschatologie à l’horizon de sa myopie : il rassemble l’alpha et l’oméga de l’Histoire – formule inadéquate quoique révélatrice de la parodie – dans l’alternance, le marché, l’hédonisme, le sentimentalisme et l’humanitarisme (ce que Schmitt appellera, non sans mépris, «la décision morale et politique dans l’ici-bas paradisiaque d’une vie immédiate, naturelle, et d’une «corporéité» sans problèmes» ou «les faits sociaux purs de toute politique»). Qui décidera de l’état d’exception en cas de guerre civile ? Le souverain, soit, personne (l’anti-personne démoniaque – en ceci, le désespoir demeure en politique une sottise absolue, puisque aussi bien le diable porte pierre).

Aucun bricolage néo-kantien ne pourra longtemps masquer le nihilisme démocratique et la vacuité moderne – d’autant moins d’ailleurs que cet excellent lecteur de Kant que fut Jacobi diagnostiqua parmi les premiers la maladie nihiliste que les trois Critiques incubèrent fort peu de temps avant qu’elle ne se déclare. L’Europe, c’est-à-dire très exactement la chrétienté selon Novalis, ne pourra réagir qu’en opposant son antidote souverain : le catholicisme. On peut prendre la question dans tous les sens, ce n’est qu’en réactivant l’interrogation théologico-politique, comme l’ont compris Joseph de Maistre, Donoso Cortès, Carl Schmitt, mais aussi Leo Strauss et Jacob Taubes d’un point de vue juif, donc, en dernière analyse, chrétien, que l’on pourra faire rendre gorge au néant. L’adhésion très temporaire de Carl Schmitt au NSDAP (après d’ailleurs qu’il a mis tout Weimar en garde, dès 1932, sur le danger national-socialiste et l’urgence à interdire, par l’article 48 de la Constitution, les partis communiste et nazi) ne s’explique là encore que par la mystique au sens de Péguy – et non la politique: le catholique conséquent croyant en l’existence de l’univers invisible et donc des mauvais anges peut être abusé par les ruses et les séductions de l’Ennemi (au sens schmittien, d’une certaine façon, nous y reviendrons) jusqu’à prendre des vessies pour des lanternes et le point culminant du nihilisme actif (et non passif, celui-ci relevant de la juridiction démocratique) pour le paroxysme de la vérité. À la lettre oxymorique, il côtoie toujours les cimes des abîmes, comme un abbé Donissan ou un curé d’Ambricourt et à la différence de n’importe quel démocrate-chrétien. Les enfileurs de perles et les analystes du rien, hommes du ni oui ni non, font aujourd’hui écran au théologien politique, homme des affirmations absolues et des négations souveraines fidèle à l’Évangile («Que votre oui soit oui, que votre non soit non», Mt 5, 37) alors que ce dernier est évidemment requis par la tiédeur infernale. Le libéralisme, hostile à toute forme de vision, ne voit bien entendu se profiler aucune eschatologie à l’horizon de sa myopie : il rassemble l’alpha et l’oméga de l’Histoire – formule inadéquate quoique révélatrice de la parodie – dans l’alternance, le marché, l’hédonisme, le sentimentalisme et l’humanitarisme (ce que Schmitt appellera, non sans mépris, «la décision morale et politique dans l’ici-bas paradisiaque d’une vie immédiate, naturelle, et d’une «corporéité» sans problèmes» ou «les faits sociaux purs de toute politique»). Qui décidera de l’état d’exception en cas de guerre civile ? Le souverain, soit, personne (l’anti-personne démoniaque – en ceci, le désespoir demeure en politique une sottise absolue, puisque aussi bien le diable porte pierre). Arthur Moeller van den Bruck fu uno dei più alti risultati ideologici conseguiti dallo sforzo europeo di uscire dalle contraddizioni e dai disastri della modernità: fu uno dei primi a politicizzare il disagio della nostra civiltà di fronte all’affermazione mondiale del liberalismo e all’ascesa della nuova anti-Europa, come fin da subito fu giudicata l’America dai nostri migliori osservatori. Di qui una netta separazione del concetto di Occidente da quello di Europa. Il rifiuto dell’Occidente capitalista e della sua violenta deriva antipopolare doveva condurre in linea retta ad una rivoluzione dei popoli europei, ad un loro ringiovanimento, al loro rilancio come vere democrazie organiche di popolo. Come tanti altri ingegni dei primi decenni del

Arthur Moeller van den Bruck fu uno dei più alti risultati ideologici conseguiti dallo sforzo europeo di uscire dalle contraddizioni e dai disastri della modernità: fu uno dei primi a politicizzare il disagio della nostra civiltà di fronte all’affermazione mondiale del liberalismo e all’ascesa della nuova anti-Europa, come fin da subito fu giudicata l’America dai nostri migliori osservatori. Di qui una netta separazione del concetto di Occidente da quello di Europa. Il rifiuto dell’Occidente capitalista e della sua violenta deriva antipopolare doveva condurre in linea retta ad una rivoluzione dei popoli europei, ad un loro ringiovanimento, al loro rilancio come vere democrazie organiche di popolo. Come tanti altri ingegni dei primi decenni del

Man mag nicht glauben, daß 56 Jahre seit der Erstveröffentlichung des vorliegenden Bandes vergangen sind! Die Fragen, denen Sieburg sich hier in neun Kapiteln (etwa »Die Kunst, Deutscher zu sein«, »Vom Menschen zum Endverbraucher«) widmet, lesen sich nicht als Rückblick auf Gefechte von gestern. Sie sind noch ebensogut unsere Themen: Identitätssuche, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, Konsumwahn, die Grenze zwischen Privatheit und Öffentlichkeit. Auch wo seine Angelegenheiten einmal der unmittelbaren Aktualität entbehren – etwa in seiner bemerkenswerten Replik auf Curzio Malaparte (d.i. K.E. Suckert) oder in seinen Einlassungen zum Verlust der Ostgebiete – nickt man staunend. Ohne Twitter oder Ryan Air gekannt zu haben, spottet Sieburg über »das Management des Vergnügens«, die »Mechanisierung der Freizeit«. Er meinte damit – wie bescheiden aus heutiger Warte! – »Betriebsausflüge an den Comer See« und Klassenfahrten in die Alpen. »Der Vorschlag, die Kinder sollten an der Nidda Blumen suchen, würde heute auf allen Seiten große Heiterkeit hervorrufen.« Für Sieburg waren die Deutschen »ein Volk ohne Mitte«: »Im Deutschen, so glaubte die Welt gestern noch, ist mehr Explosivstoff angehäuft als in jedem anderen Erdenbewohner. Hat sich diese Ansicht geändert, sind beim Anblick des fleißigen und lammfrommen Bundesdeutschen, der sogar den Karneval straff organisiert und wirtschaftsbewußt dem Konsum dienstbar macht, der das Wort Europa dauernd im Mund führt, (…) den kein Aufmarsch mit Fahnen mehr aus seinem Wochenendhaus, seinem Faltboot und Volkswagen herauslocken kann, der nur noch zu den Vertretern versunkener Fürstenhäuser und zu Filmstars aufschaut, der einen harmonischen Bund zwischen Preußentum und Nackenfett eingegangen ist, (…) der vom Golf von Neapel bis zum Nordkap die schnellsten Wagen fährt, sich in Capri bräunen läßt (…), der sich aus Ordnungssinn mit der abstrakten Kunst und dem Nihilismus beschäftigt – sind, so frage ich, beim Anblick dieses Musterknaben, der sich in der Schule der Demokratie zum Primus aufarbeitet, alle Ängste und mißtrauische Befürchtungen verschwunden? Ich antworte, nein.«

Man mag nicht glauben, daß 56 Jahre seit der Erstveröffentlichung des vorliegenden Bandes vergangen sind! Die Fragen, denen Sieburg sich hier in neun Kapiteln (etwa »Die Kunst, Deutscher zu sein«, »Vom Menschen zum Endverbraucher«) widmet, lesen sich nicht als Rückblick auf Gefechte von gestern. Sie sind noch ebensogut unsere Themen: Identitätssuche, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, Konsumwahn, die Grenze zwischen Privatheit und Öffentlichkeit. Auch wo seine Angelegenheiten einmal der unmittelbaren Aktualität entbehren – etwa in seiner bemerkenswerten Replik auf Curzio Malaparte (d.i. K.E. Suckert) oder in seinen Einlassungen zum Verlust der Ostgebiete – nickt man staunend. Ohne Twitter oder Ryan Air gekannt zu haben, spottet Sieburg über »das Management des Vergnügens«, die »Mechanisierung der Freizeit«. Er meinte damit – wie bescheiden aus heutiger Warte! – »Betriebsausflüge an den Comer See« und Klassenfahrten in die Alpen. »Der Vorschlag, die Kinder sollten an der Nidda Blumen suchen, würde heute auf allen Seiten große Heiterkeit hervorrufen.« Für Sieburg waren die Deutschen »ein Volk ohne Mitte«: »Im Deutschen, so glaubte die Welt gestern noch, ist mehr Explosivstoff angehäuft als in jedem anderen Erdenbewohner. Hat sich diese Ansicht geändert, sind beim Anblick des fleißigen und lammfrommen Bundesdeutschen, der sogar den Karneval straff organisiert und wirtschaftsbewußt dem Konsum dienstbar macht, der das Wort Europa dauernd im Mund führt, (…) den kein Aufmarsch mit Fahnen mehr aus seinem Wochenendhaus, seinem Faltboot und Volkswagen herauslocken kann, der nur noch zu den Vertretern versunkener Fürstenhäuser und zu Filmstars aufschaut, der einen harmonischen Bund zwischen Preußentum und Nackenfett eingegangen ist, (…) der vom Golf von Neapel bis zum Nordkap die schnellsten Wagen fährt, sich in Capri bräunen läßt (…), der sich aus Ordnungssinn mit der abstrakten Kunst und dem Nihilismus beschäftigt – sind, so frage ich, beim Anblick dieses Musterknaben, der sich in der Schule der Demokratie zum Primus aufarbeitet, alle Ängste und mißtrauische Befürchtungen verschwunden? Ich antworte, nein.« Müdigkeit und Geschichtslosigkeit zeige, »die mit einer nie dagewesenen Nüchternheit« gepaart sei. »Nur der Deutsche schwärzt seinen Landsmann bei Fremden an, nur der Deutsche verständigt sich lieber mit einem Exoten als mit einem politischen Gegner eigenen Stammes (…), nur der Deutsche verleugnet Flagge, Hymne und Staatsform des Mutterlandes vor Dritten.« Als »dümmstes Schlagwort« seiner Zeit erschien dem Publizisten der schon damals opportune Vorwurf, »restaurative Tendenzen« zu befördern. Alles Große, Geniale, das Heldenhafte ohnehin, dessen die Deutschen einst fähig waren, werde nun verhöhnt und gegeißelt unter dem Vorwand, »daß die alten Zeiten nicht wiederkommen dürfen«. Ja, und wie furchtbar war auch der »deutsche Spießer!« Allerdings, so Sieburg, sei zu befürchten, daß der Spießer in neuem Gewand, nämlich mit »heraushängendem Hemd« nach US-Vorbild wiedergekehrt sei, und daß die »Vorurteilslosigkeit in der Kleidung, im Umgang mit dem anderen Geschlecht und den Nerven der Mitmenschen nicht eine höhere sittliche Freiheit und einen souveränen Geist« mit sich führe.

Müdigkeit und Geschichtslosigkeit zeige, »die mit einer nie dagewesenen Nüchternheit« gepaart sei. »Nur der Deutsche schwärzt seinen Landsmann bei Fremden an, nur der Deutsche verständigt sich lieber mit einem Exoten als mit einem politischen Gegner eigenen Stammes (…), nur der Deutsche verleugnet Flagge, Hymne und Staatsform des Mutterlandes vor Dritten.« Als »dümmstes Schlagwort« seiner Zeit erschien dem Publizisten der schon damals opportune Vorwurf, »restaurative Tendenzen« zu befördern. Alles Große, Geniale, das Heldenhafte ohnehin, dessen die Deutschen einst fähig waren, werde nun verhöhnt und gegeißelt unter dem Vorwand, »daß die alten Zeiten nicht wiederkommen dürfen«. Ja, und wie furchtbar war auch der »deutsche Spießer!« Allerdings, so Sieburg, sei zu befürchten, daß der Spießer in neuem Gewand, nämlich mit »heraushängendem Hemd« nach US-Vorbild wiedergekehrt sei, und daß die »Vorurteilslosigkeit in der Kleidung, im Umgang mit dem anderen Geschlecht und den Nerven der Mitmenschen nicht eine höhere sittliche Freiheit und einen souveränen Geist« mit sich führe.

Les revenus générés par cette activité éditoriale demeurèrent assez sporadiques, ce qui obligea les habitants de la Maison Fidus, auxquels s’était jointe la femme écrivain du mouvement de jeunesse, Gertrud Prellwitz, à adopter un mode de vie très spartiate. L’avènement du national-socialisme ne changea pas grand chose à leur situation. Fidus avait certes placé quelque espoir en Adolf Hitler parce que celui-ci était végétarien et abstinent, voulait que les Allemands se penchent à nouveau sur leurs racines éparses, mais cet espoir se mua en amère déception. La politique culturelle nationale-socialiste refusa de reconnaître la pertinence des visions des ermites de Woltersdorf et stigmatisa « les héros solaires éthérés » de Fidus comme une expression de l’ « art dégénéré ». Dans le catalogue de l’exposition sur l’ « art dégénéré » de 1937, on pouvait lire ces lignes : « Tout ce qui apparaît, d’une façon ou d’une autre, comme pathologique, est à éliminer. Une figure de valeur, pleine de santé, même si, racialement, elle n’est pas purement germanique, sert bien mieux notre but que les purs Germains à moitié affamés, hystériques et occultistes de Maître Fidus ou d’autres originaux folcistes ». L’artiste ne recevait plus beaucoup de commandes. Beaucoup de revues du mouvement « Lebensreform » ou du mouvement de jeunesse, pour lesquelles il avait travaillé, cessèrent de paraître. Sa deuxième femme, Elsbeth, fille de l’écrivain Moritz von Egidy, qu’il avait épousée en 1922, entretenait la famille en louant des chambres d’hôte (« site calme à proximité de la forêt, jardin ensoleillé avec fauteuils et bain d’air, Blüthner-Flügel disponibles »). L’ « original folciste » a dû attendre sa 75ème année, en 1943, pour obtenir le titre de professeur honoris causa et pour recevoir une pension chiche, accordée parce qu’on avait finalement eu pitié de lui.

Les revenus générés par cette activité éditoriale demeurèrent assez sporadiques, ce qui obligea les habitants de la Maison Fidus, auxquels s’était jointe la femme écrivain du mouvement de jeunesse, Gertrud Prellwitz, à adopter un mode de vie très spartiate. L’avènement du national-socialisme ne changea pas grand chose à leur situation. Fidus avait certes placé quelque espoir en Adolf Hitler parce que celui-ci était végétarien et abstinent, voulait que les Allemands se penchent à nouveau sur leurs racines éparses, mais cet espoir se mua en amère déception. La politique culturelle nationale-socialiste refusa de reconnaître la pertinence des visions des ermites de Woltersdorf et stigmatisa « les héros solaires éthérés » de Fidus comme une expression de l’ « art dégénéré ». Dans le catalogue de l’exposition sur l’ « art dégénéré » de 1937, on pouvait lire ces lignes : « Tout ce qui apparaît, d’une façon ou d’une autre, comme pathologique, est à éliminer. Une figure de valeur, pleine de santé, même si, racialement, elle n’est pas purement germanique, sert bien mieux notre but que les purs Germains à moitié affamés, hystériques et occultistes de Maître Fidus ou d’autres originaux folcistes ». L’artiste ne recevait plus beaucoup de commandes. Beaucoup de revues du mouvement « Lebensreform » ou du mouvement de jeunesse, pour lesquelles il avait travaillé, cessèrent de paraître. Sa deuxième femme, Elsbeth, fille de l’écrivain Moritz von Egidy, qu’il avait épousée en 1922, entretenait la famille en louant des chambres d’hôte (« site calme à proximité de la forêt, jardin ensoleillé avec fauteuils et bain d’air, Blüthner-Flügel disponibles »). L’ « original folciste » a dû attendre sa 75ème année, en 1943, pour obtenir le titre de professeur honoris causa et pour recevoir une pension chiche, accordée parce qu’on avait finalement eu pitié de lui.

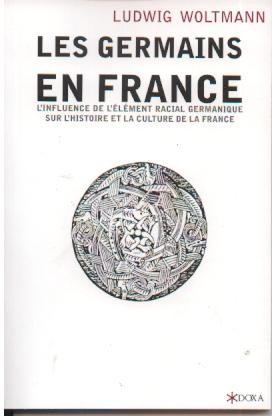

Comenzamos por señalar la corriente darwinista que reinterpretó la lucha de clases como una lucha de razas, en la que destaca la obra de Ludwig Gumplowicz (Der Rassenkampf), judío de origen polaco que, casualmente, sería considerado como maestro sociológico por el germanista radical Ludwig Woltmann. Precisamente, increpado Gumplowicz por su discípulo Woltmann al haber abandonado el concepto de raza, el sociólogo nostálgico respondió en los siguientes términos: «Me sorprendía … ya en mi patria de origen el hecho de que las diferentes clases sociales representasen razas totalmente heterogéneas; veía allí a la nobleza polaca, que se consideraba con razón como procedente de un tronco completamente distinto del de los campesinos; veía la clase media alemana y, junto a ella, a los judíos; tantas clases como razas … pero, en los países del occidente de Europa sobre todo, las distintas clases de la sociedad hace ya mucho tiempo que no representan otras tantas razas antropológicas y, sin embargo, se enfrentan las unas a las otras como razas distintas …».

Comenzamos por señalar la corriente darwinista que reinterpretó la lucha de clases como una lucha de razas, en la que destaca la obra de Ludwig Gumplowicz (Der Rassenkampf), judío de origen polaco que, casualmente, sería considerado como maestro sociológico por el germanista radical Ludwig Woltmann. Precisamente, increpado Gumplowicz por su discípulo Woltmann al haber abandonado el concepto de raza, el sociólogo nostálgico respondió en los siguientes términos: «Me sorprendía … ya en mi patria de origen el hecho de que las diferentes clases sociales representasen razas totalmente heterogéneas; veía allí a la nobleza polaca, que se consideraba con razón como procedente de un tronco completamente distinto del de los campesinos; veía la clase media alemana y, junto a ella, a los judíos; tantas clases como razas … pero, en los países del occidente de Europa sobre todo, las distintas clases de la sociedad hace ya mucho tiempo que no representan otras tantas razas antropológicas y, sin embargo, se enfrentan las unas a las otras como razas distintas …». Las tesis iniciales de Woltmann, no obstante lo anterior, irían cobrando un intenso matiz germanista, hasta el extremo de no tolerar la unión de los alemanes con otras ramas de la familia nord-europea. Es más, una posible asimilación de los otros pueblos germánicos –daneses, holandeses, etc- la condicionaba a su dominio por parte de una gran Alemania. La extravagancia de Woltmann, que partía de la idea según la cual el valor de una civilización depende de la cantidad de raza rubia germana que contenga, le hizo asegurar que los grandes hombres (nobles, políticos, artistas, filósofos, etc) más representativos de la cultura y la sociedad italiana, francesa y española eran, sin duda alguna, de ascendencia germánica, pensando que sus cualidades anímicas y espirituales revelarían siempre los caracteres antropológicos del germano, dolicocéfalo y rubio, aun cuando su apariencia física externa fuera la de un alpino braquicéfalo o la de un oscuro mediterráneo.

Las tesis iniciales de Woltmann, no obstante lo anterior, irían cobrando un intenso matiz germanista, hasta el extremo de no tolerar la unión de los alemanes con otras ramas de la familia nord-europea. Es más, una posible asimilación de los otros pueblos germánicos –daneses, holandeses, etc- la condicionaba a su dominio por parte de una gran Alemania. La extravagancia de Woltmann, que partía de la idea según la cual el valor de una civilización depende de la cantidad de raza rubia germana que contenga, le hizo asegurar que los grandes hombres (nobles, políticos, artistas, filósofos, etc) más representativos de la cultura y la sociedad italiana, francesa y española eran, sin duda alguna, de ascendencia germánica, pensando que sus cualidades anímicas y espirituales revelarían siempre los caracteres antropológicos del germano, dolicocéfalo y rubio, aun cuando su apariencia física externa fuera la de un alpino braquicéfalo o la de un oscuro mediterráneo.

Der 26. September 1996 war ein bedeutender Tag – auch wenn dies die Öffentlichkeit erst mehr als ein Jahr später erfahren sollte. An diesem Tag wurde Ernst Jünger in die katholische Kirche aufgenommen. Beim Gottesdienst zu diesem Anlaß wurde nach Jüngers Wunsch der Psalm 73 gebetet, in dem er die oft verschlungenen Pfade seines Lebens widergespiegelt sah:

Der 26. September 1996 war ein bedeutender Tag – auch wenn dies die Öffentlichkeit erst mehr als ein Jahr später erfahren sollte. An diesem Tag wurde Ernst Jünger in die katholische Kirche aufgenommen. Beim Gottesdienst zu diesem Anlaß wurde nach Jüngers Wunsch der Psalm 73 gebetet, in dem er die oft verschlungenen Pfade seines Lebens widergespiegelt sah:

Keith Preston

Keith Preston is the chief editor of AttacktheSystem.com and holds graduate degrees in history and sociology. He was awarded the 2008 Chris R. Tame Memorial Prize by the United Kingdom's Libertarian Alliance for his essay, "Free Enterprise: The Antidote to Corporate Plutocracy."