Texte reparti en deux sous-titres:

I. LA CHINE ET SA STRATÉGIE DE SÉCURITÉ. UN NOUVEL ÉQUILIBRE ENTRE DÉFENSE MODERNISÉE. GUERRE ASYMÉTRIQUE ET STRATÉGIE MILITAIRE

(première partie; cf. : http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/archive/2021/02/28/du-monde-harmonieux-au-reve-chinois-la-chine-et-sa-strategie-de-securite.html

II. LA QUÊTE DE POUVOIR DE LA CHINE ET LE DÉBAT SUR LA PUISSANCE NATIONALE. VERS LA PRÉÉMINENCE MONDIALE?

(deuxième partie)

***

TABLE DES MATIÈRES

I. LA CHINE ET SA STRATÉGIE DE SÉCURITÉ. UN NOUVEL ÉQUILIBRE ENTRE DÉFENSE MODERNISÉE, GUERRE ASYMÉTRIQUE ET STRATÉGIE MILITAIRE (première partie)

Chine et États-Unis. Préservation du "statu quo" ou inversion de prééminence

De la "défense passive en profondeur"(Mao) à la "défense active" dans les "guerres locales et limitées" (Deng Tsiao Ping et Xi Jinping)

La puissance nationale comme stratégie

"Vaincre le supérieur par l'inférieur"

Sur la "guerre d'information asymétrique d'acupuncture" et la guerre préventive

Conditions pour l'emporter dans un conflit limité

L'asymétrie, son concept et sa définition

L'asymétrie, le nouveau visage de la guerre et la "double spirale des défis"

II. LA QUÊTE DE POUVOIR DE LA CHINE ET LE DÉBAT SUR LA PUISSANCE NATIONALE. VERS LA PRÉÉMINENCE MONDIALE ? (deuxième partie)

Normalisation et "diplomatie asymétrique"

De la stratégie triangulaire (Chine, Union Soviétique, États-Unis) au condominium planétaire (duopole de puissance)

Paix et Guerre dans une conjoncture de mutations

Une entente pacifique renforcée avec les États-Unis de la part de la Chine? Ou un "rééquilibrage stratégique à distance" de la part des États-Unis?

De Deng Xiaoping à Xi Jinping, vers l'inversion de prééminence?

Le "Rapport Crowe" et l'analogie historique

Deux questionnements et deux interprétations des tensions actuelles et de leurs issues

L'activisme chinois et les "intérêts vitaux" de la Chine

Le "Rapport 2010" et la mission historique des forces armées chinoises

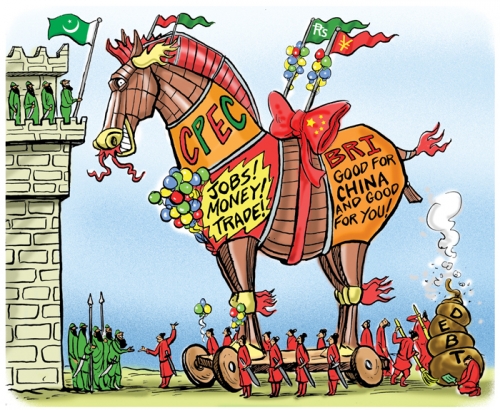

L'ordre apparent et la ruse. Sur les répercussions stratégiques et militaires de la nouvelle "Route de la Soie"

***

II. LA QUÊTE DE POUVOIR DE LA CHINE ET LE DÉBAT SUR LA PUISSANCE NATIONALE. VERS LA PRÉÉMINENCE MONDIALE? (deuxième partie)

Normalisation et "diplomatie asymétrique"

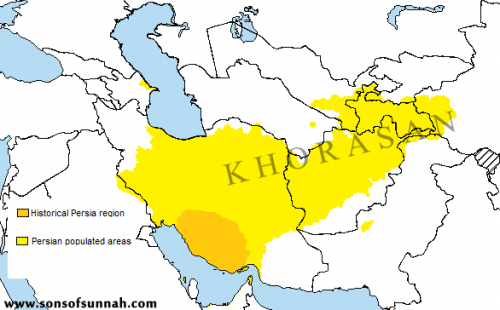

Depuis la normalisation des relations avec les États-Unis, lors de la visite de Nixon et de Kissinger à Mao Zedong en 1972, nous assistons à une surprenante montée en puissance, civile et militaire, de la Chine, destinée à jouer un rôle de plus en plus grand en Extrême Orient, dans le Pacifique, dans l’Asie du Sud-Est et en Asie centrale, mais aussi à affirmer sa marche vers la prééminence planétaire, par une diplomatie active dont la place centrale est représentée par ses rapports avec les USA.

Les rapports avec les USA ont été qualifiés par des officiels de Pékin, sous la Présidence Hu Jintao (2003-2013), comme "un partenariat stratégique et constructif tourné vers le XXIème siècle".

Ces déclarations ont constitué le fondement d’une "diplomatie asymétrique", dont la doctrine stratégique reposa sur la politique des "quatre non" : "Non à l’hégémonisme, non à la politique de force, non à une politique de blocs, non à la course aux armements".

En termes opératoires, cela signifia la préférence accordée aux relations bilatérales dans le règlement des contentieux frontaliers, l’utilisation active des relations multilatérales au sein des organisations régionales et, enfin, l’emploi des bénéfices de la croissance pour faire face aux différends politiques croissants avec un esprit de négociation et de compromis

De la stratégie triangulaire (Chine, Union Soviétique, États-Unis) au condominium planétaire (duopole de puissance)

La stratégie triangulaire de la Chine résulta d'une articulation d'objectifs corrélés:

- isoler les USA, en attisant les contradictions entre leur rôle mondial et celui de garant politico-militaire de la sécurité du Japon

- fomenter les craintes encore très vives des pays asiatiques, contre une éventuelle remilitarisation et nucléarisation de l'Empire du Soleil Levant, en mettant en crise le système de sécurité nippo-américain, qui visait à contenir la Chine,

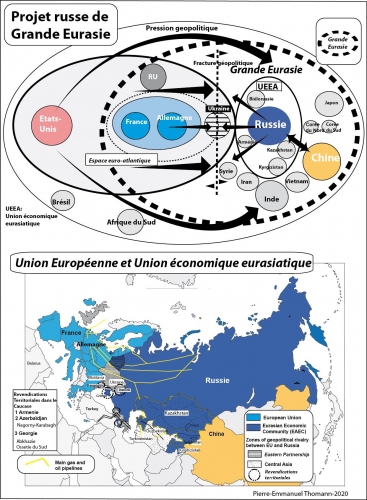

- enfin, faire prendre conscience aux États-Unis que, pour assurer leur influence en Eurasie et pour maintenir leur stratégie de présence en Asie centrale et en Asie-Pacifique, ils devaient réorienter radicalement leurs alliances et opter pour un véritable partenariat géopolitique, de portée mondiale, avec la Chine, puissance de la terre, qui est à considérer, théoriquement, comme l’allié naturel des États-Unis, puissance de la mer.

Ainsi, les relations sino-américaines passeraient de la posture d’un affrontement éventuel, à la posture d’un condominium planétaire, autrement dit à celui d’un duopole de puissance inédit et dés-occidentalisé, asiatisé et sinisé.

Deux problèmes interdépendants se posaient alors aux États-Unis et en Asie Extrême Orientale:

- la définition des "limites" à assigner à la Chine dans son aspiration à devenir une puissance régionale dominante et le seuil de dangerosité acceptable pour accéder au rang de puissance globale.

Quelle aire d’influence lui serait-elle reconnue? Quel espace de manœuvre avec Taïwan, la Malaisie, la Birmanie, pour le contrôle du détroit de Malacca et du goulet de Singapour, et quel déploiement des capacités militaires permettraient à la Chine d’exercer une maîtrise maritime des voies d’accès du Japon au pétrole du Golfe et du Moyen Orient et aux marchés de l’Europe Occidentale et Orientale ?

En conclusion, beaucoup d’inconnues et d’incertitudes planaient à l'époque sur la stabilité régionale en Extrême Orient ainsi que sur les poussées nationalistes qui tiennent encore en éveil l’Asie, aux immenses disparités, économiques, politiques et culturelles, marquées également par un retour prononcé aux jeux d’influences et à la "Balance of Power".

Paix et Guerre dans une conjoncture de mutations

La politique étrangère chinoise construit l’avenir sur une mutation de taille, dictée par sa transformation de puissance mondiale classique en puissance globale, un type de puissance qui est en même temps pluri-dimensionnelle et « hors limite » ; une puissance terrestre, maritime, spatiale et en réseau.

Li Zao Xing.

La Chine, d’après le Ministre des Affaires Étrangères, Li Zao Xing se prépare-t-elle à atteindre des "ambitions démesurées grâce à une politique extérieure mesurée"?

Le but de la politique chinoise de construire sur le long terme et au courant du XXIème siècle, "une société d’aisance moyenne", ne peut être atteint que dans un contexte international favorable et celui-ci serait caractérisé par une "paix mondiale prolongée" et "une ère nouvelle, combinant alliances et affrontements: une ère de non guerre (n.d.r.-mondiale ou systémique)".

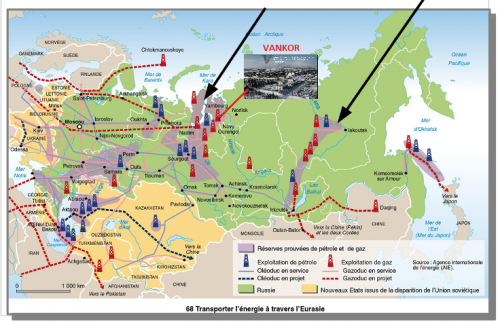

C’est dans ce contexte de quête de la suprématie globale, que doivent être lus les efforts inhabituels de la "diplomatie de l’apaisement", pour mettre un terme aux multiples tensions territoriales avec les pays frontaliers, le long des lignes de frontières terrestres parmi les plus longues du monde (protocole d’accord entre la Chine et l’Inde du 11 avril 2005, accord de Vladivostok du 2 juin 2005 entre Russie et Chine).

Il s’agit-là d’ententes pacifiques à haute importance stratégique entre les deux puissances majeures de l’Eurasie, la Russie et la Chine, dont la signification a été de

jouer à la pression démographique au Nord, dans les zones inhabitées de la Sibérie Centrale et Orientale et de créer des liaisons d’assurance et de confiance au Sud, dans le but de créer des liens de vassalité et de déférence avec les pays de l’ASEAN.

Une entente pacifique renforcée avec les États-Unis de la part de la Chine? Ou un "rééquilibrage stratégique à distance" de la part des États-Unis?

Ici, l'entente pacifique renforcée, par une stratégie de sécurisation des voies maritimes dans les mers de Chine du Sud, acquiert une dimension plus offensive vers l'Océan Pacifique, par le développement de capacité d'interdictions navales et spatiales, mais cette dimension est encore de théâtre.

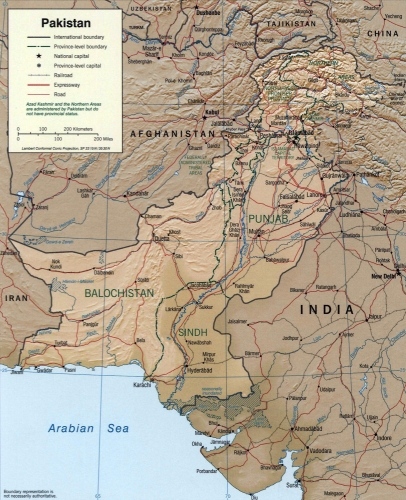

En effet la Mer de Chine Méridionale devient un des théâtres géopolitiques parmi les plus critiques de la planète, car se superposent ici les projections d'influence de la Chine, à caractère expansif et le rôle régional des États-Unis, à caractère défensif. Les premières remettent en cause la stabilité régionale, le deuxième préfigure un "soft containment" global d'un type nouveau. Les perspectives changent encore en se plaçant au niveau planétaire ou systémique. A partir de discours d'Obama à Tokyo en novembre 2009, la politique de l'Administration américaine visera à définir les États-Unis comme "une Nation du Pacifique" , ce qui explique le nouveau "grand jeu" qui se dessina à partir de là, entre les États-Unis et la Chine, en mer de Chine méridionale. En effet, le désengagement des USA de l'Irak et du Pakistan permit un réengagement américain en Asie-Pacifique, dans le but d'en faire une priorité géopolitique pour le XXIe siècle.

Cet réengagement des États-Unis se définira comme projet de partenariat, liant valeurs et intérêts américains, par la création d'une grande aire de libre-échange dans la zone Pacifique et comme renforcement du dispositif et des alliances militaires (ANZUS) défiant les ambitions régionales de la Chine, à propos des îles Paracels. Le cadre de ces disputes territoriales se situait entre Beijing et quatre pays de l'ASEAN (Vietnam, Philippines, Malaisie, Brunei, et Taïwan). Or, dans la perspective d'un monde multipolaire et de plusieurs types de menaces, les États-Unis resteraient en retrait et laisseraient leurs alliés se prendre en charge par eux-mêmes, n'intervenant, par hypothèse, qu'en dernier recours. Il s'agirait dans ce cas d'un "rééquilibrage stratégique à distance". Pourquoi cette ruse et à partir de quelle conception? Christopher Laye a développé en 1997 l’idée selon laquelle, en cas d'hégémonie incomplète, le contrôle régional sur la montée en puissance d'un acteur à vocation hégémonique, visant à maximiser la puissance ou la sécurité, peut être délégué à un État-tiers allié ou à plusieurs États régionaux de première ligne. Dans le cas de la Chine au Japon, à la Corée et à l'Australie. Dans l'hypothèse d'un échec, la puissance hégémonique aurait l'obligation d'intervenir, pour rétablir le "statu-quo" ou la stabilité, directement ou avec son système d'alliances, car la stabilité du système dépendrait de la puissance dominante.

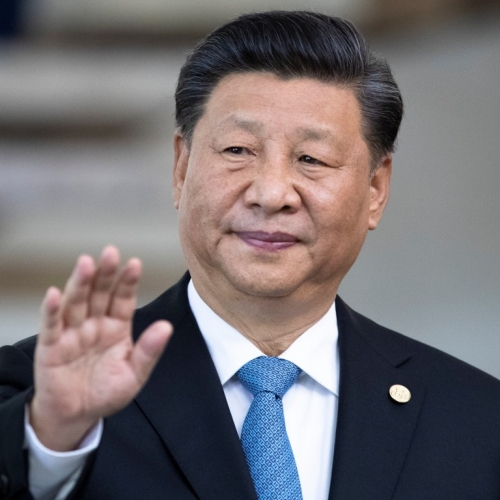

De Deng Xiaoping à Xi Jinping, vers l'inversion de prééminence?

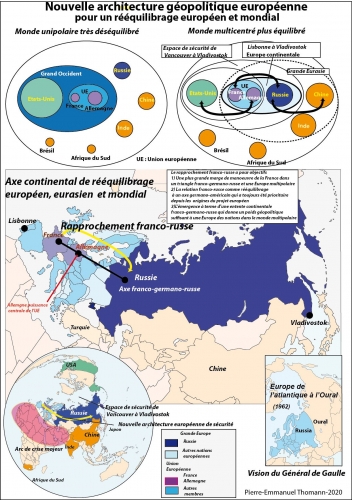

Avec le passage de l'ère Deng Xiaoping à celle de Xi JInping,la Chine est elle passée d'une politique de "modernisation et d'ouverture", axée sur intégration dans l'ordre mondial à une trajectoire de grande puissance, orientée vers une stratégie, une ambition et un grand défi à l'ordre hégémonique, à la quête de sa prééminence? En situation de pente vers un terrain d'affrontement, la Chine est elle prête à en payer le prix, que la sophistication des nouveaux systèmes d'armes rend plausible, celui d'une "guerre nucléaire limitée" ? L'hégémonie américaine est-elle totalement dépassée et la guerre inter-étatique est elle encore une menace pour la paix mondiale? Et surtout a-t-elle encore une fin et laquelle? Au moment où les États-Unis semblent entamer un déclin relatif et la démocratie américaine présente des fissurations illibérales, la reconfiguration du système international, en Europe et en Asie, est susceptible de devenir une source de dangers. Le processus de diffusion de puissance permet l'ascension de nouveaux États forts qui modifient la "Balance of Power" mondiale, créant de nouvelles sources d'instabilités. Le vieux système de la bipolarité, devenu unipolaire, puis tendenciellement multipolaire et, sur fond de démondialisation, tri-penta-polaire, acquerra en perspective et à nouveau un visage bipolaire, à une échelle planétaire amplifiée. La propension à l'instabilité et à la guerre inter-étatique d'une telle configuration est au moins équivalente à sa tendance à la stabilité. l'inconnue objective étant dans la fragmentation politique, interne et internationale et dans les facteurs de violence transnationaux en tout ordre, ethniques, religieux et civilisationnels. Ceux-ci compliqueront les calculs des puissances majeures du système, accroissant le désordre.

Ainsi, face aux résurgences des diplomaties réalistes à raisonner en termes de rapports de forces, de course aux armements et de budgets comme dans les deux grands siècles (XVIIème et XIXème) de l'équilibre de puissances et de la politique de cabinet (ou chambre des boutons nucléaires), la transition géopolitique et stratégique de nos jours, sera difficile à gérer; en particulier entre les États-Unis et la Chine, et entre la Chine et la Russie, et la Chine, le Japon et les deux Corées, sans parler du Pakistan et de l'inde et, au Grand Moyen Orient, entre la Turquie, la Syrie, Israël, l'Iran et les pays du Golfe. La multipolarité d'aujourd'hui, différente en nombre et en dangerosité par rapport à sa forme antérieure, engendrera des instabilités browniennes, qui affecteront à nouveau l'Europe, si les États-Unis s'en retireront et les vieilles méfiances et les vieux antagonismes renaîtront entre les pays du vieux continent. Ça sera à ce point qu'un grand moment d'opportunité venant d'Asie, dominera le péril stratégique à Taïwan et la Chine millénaire pourra alors inverser la prééminence hégémonique, s'affirmant par la force et la glorification de la force.

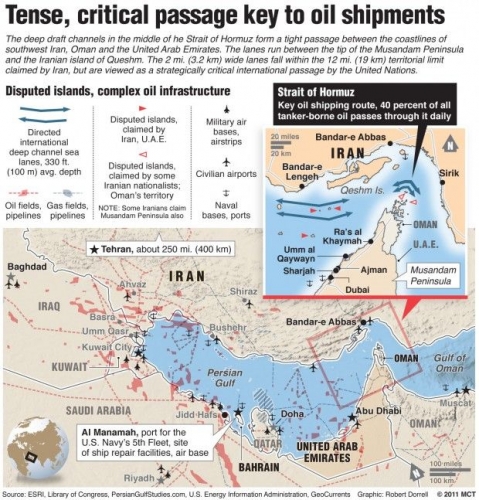

Les manœuvres navales conjointes de l'Iran, de la Russie et de la Chine dans l'Océan indien et le Golfe Persique, du 16 février 2021, alors que l'Otan organisait un sommet sur la "rivalité stratégique" à l'encontre de la Russie et de la Chine, ravivent la rivalité avec l' Amérique et provoquent des tensions qui rappellent la mise en place d'une sorte de "guerre froide" à caractère bipolaire, sur fond de lutte d'influences multipolaires. Cette stratégie n'est pas sans rappeler la pertinence des intérêts vitaux de chaque puissance, bref le rappel d'une menace régionale, fondée sur des structures capacitaires asymétriques et en ascension, remettant en cause la présence américaine et sa légitimité.

Il s'ajoute que Xi Jinping lui même a soufflé sur le feu par une rhétorique guerrière à Shautou, port militaire de la Chine méridionale, invitant les soldat de l'ALP à se tenir "prêts à mener une guerre" contre la "province renégate de Taïwan", le 13 octobre 2020.

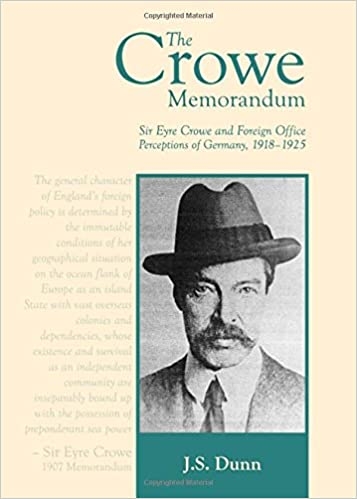

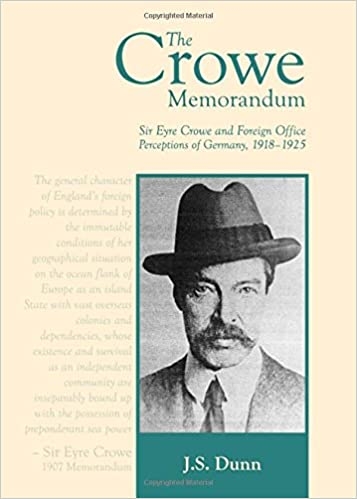

Le "Rapport Crowe" et l'analogie historique

Dans ce contexte, les théories de la "montée pacifique" et d'un "monde harmonieux" dépendent du niveau d'assurance qui peut être obtenu par la diplomatie et du degré de confiance, induit par la stabilité régionale et locale. Elles peuvent être compromises par le développement de la technologie et des systèmes d'armes, conçus en vue d'acquérir une avancée stratégique significative, qui amène en retour à une course aux armements et à des risques de conflits. C'est au sujet d'une analyse comparée des équilibres internationaux du concert européen du XIXème et des perturbations dans le calcul des rapports de force, successifs à l'unification de l'Empire allemand en 1871, que le débat sur le destin national de la Chine (2007-2010), a suscité une quête sur les sources de la confiance d'un pays millénaire, la tradition, l'idéologie et l'esprit national. L'analyse historique semble avoir démontré que les causes du conflit de la première guerre mondiale en Europe furent moins les structure des rapports de forces issus de l'unification allemande, que les enjeux et les ambitions des élites de l'Empire et, parmi d'autres importants facteurs, le plus influents de tous, le nationalisme et les irrédentismes diffus. La rivalité anglo-allemande, qui se greffait sur cette tension permanente, domina la politique européenne de la fin du XIXème, lorsque le monde se résumait à l'Europe et fut caractérisée par les difficultés d"une diplomatie rigide et sans flexibilité, limitant le champ d'action d'action des principaux pays du concert européen. En effet, compte tenu de l'unification de l'Allemagne montante, qui se sentait entourée d'hostilité et de limites à son influence, poussa le Foreign Office britannique à s'interroger sur la menace objective de l'Empire allemand, pour sa survie et pour la compatibilité de la montée en puissance, surtout navale, d'un pays continental, avec l'existence même de l'Empire britannique.

Aujourd'hui comme hier la compétition est devenue stratégique et la limitation des espaces de manœuvre consentis, a provoqué la lente création de deux blocs d'alliances rivales, auxquelles le nationalisme ou le souverainisme renaissants fournissent l'aliment idéologique pour les futurs belligérants. En ce qui concerne l'analogie historique, toujours imprécise, entre la situation européenne du XIXème et celle eurasienne du XXIème, la question de fond,qui préoccupait la Grande Bretagne de l'époque et les États-Unis d'aujourd'hui, était de savoir si la crise d'hégémonie et le problème de l'alternance qui iraient se manifester, étaient dus à la structure générale de la configuration du système ou à une politique spécifique de l'un ou de l'autre des deux "compétitors" et si, in fine, l'existence même de l'empire américain serait menacée et avec elle, celle de l'Occident et de la civilisation occidentale, jusqu'à sa variante russo-orthodoxe. Le Mémorandum Crowe, dans le cas de l'Allemagne montante et dans le cadre d'une analyse de la structure de la puissance, concluait pour l'incompatibilité entre les deux pouvoirs, britannique et allemand, et excluait la confiance et la coopération de la part de la Grande Bretagne. Ainsi l'importance des enjeux, interdisait à celle-ci d'assumer des risques et l'obligeait à prévoir le pire.

Aujourd'hui comme hier la compétition est devenue stratégique et la limitation des espaces de manœuvre consentis, a provoqué la lente création de deux blocs d'alliances rivales, auxquelles le nationalisme ou le souverainisme renaissants fournissent l'aliment idéologique pour les futurs belligérants. En ce qui concerne l'analogie historique, toujours imprécise, entre la situation européenne du XIXème et celle eurasienne du XXIème, la question de fond,qui préoccupait la Grande Bretagne de l'époque et les États-Unis d'aujourd'hui, était de savoir si la crise d'hégémonie et le problème de l'alternance qui iraient se manifester, étaient dus à la structure générale de la configuration du système ou à une politique spécifique de l'un ou de l'autre des deux "compétitors" et si, in fine, l'existence même de l'empire américain serait menacée et avec elle, celle de l'Occident et de la civilisation occidentale, jusqu'à sa variante russo-orthodoxe. Le Mémorandum Crowe, dans le cas de l'Allemagne montante et dans le cadre d'une analyse de la structure de la puissance, concluait pour l'incompatibilité entre les deux pouvoirs, britannique et allemand, et excluait la confiance et la coopération de la part de la Grande Bretagne. Ainsi l'importance des enjeux, interdisait à celle-ci d'assumer des risques et l'obligeait à prévoir le pire.

Deux questionnements et deux interprétations des tensions actuelles et de leurs issues

Dans la situation actuelle, deux questionnements et deux interprétations sont possibles, du coté chinois et du côté américain Du pont de vue historique la Chine et les États-Unis représentent deux États-civilisations qui prétendent à deux types d'universalité et à deux identités hétérogènes. Celles-ci se réalisent dans le Pacifique et dans le monde de manière incompatible et antithétique, excluant la confiance entre deux cultures opposées, une ouverte et directe et l'autre allusive, symbolique et cryptée. Les institutions politiques sont nées, pour l'Amérique du refus du Léviathan et de la logique des contre-pouvoirs et, pour la Chine millénaire, de la divinisation de l’empereur et du principe absolu de hiérarchie, mentale et sociale, justifiant et pratiquant l'obscurité et le secret des propos. Une coopération authentique ne peut naître que la confiance, qu'interdisent l'idéologie politique et les défis intérieurs, de nature démographique, générationnelle et sociale en Chine, et de nature, raciale, sociale et politique en Amérique. Ici la différence capitale est dans la conception de l'ordre social, à obtenir par la concurrence, la mobilité et le progrès économique et scientifique, en Chine dans l'idéologie millénaire de la tradition et dans celle, marxisante, du parti-État, qui exclut contestations et oppositions. Toujours en termes de défis intérieurs, le consensus de masse repose en Amérique dans les classes moyennes en décomposition et en Chine d'une exclusion des droits individuels, subordonnés à la constitution de l’État. La contrainte physique et la privation de la liberté ne peuvent revêtir la même importance en Chine ou en Amérique, car l'origine des droits est en Chine dans l’État et, en Occident, dans l"individus ou dans la fiction du peuple-souverain. La question des droits de l'homme et celle de la stratégie d'endiguement de la Chine, par la réunion d'une ceinture d’États de démocratie formelle, fait partie d'un projet américain d'une reconfiguration de l'Asie et, plus largement de l'Eurasie. En réalité, la présence américaine en Asie est jugée cruciale pour le maintien de la stabilité régionale, car aucun pays en Asie ne veut vivre dans une région dominée par la Chine. La modernisation militaire de l'APL, dont le but stratégique est l'objet d'interrogations multiples, fait de la région Asie-Pacifique, plus encore de l'Asie Centrale, une zone où les risques de confrontation ne sont pas à exclure. Dans ce contexte, les Etats-Unis ont réaffirmé l'engagement de leurs pays aux côtés de certains pays de l'ASEAN et surtout de l'ANZUS (USA, Australie, Nouvelle Zélande conclu en 1951), inquiets de l'influence grandissante de la Chine dans la région Asie-Pacifique, en apportant une réponse au "dilemme chinois" de l'Australie, dont le défi consiste à concilier un ancrage économique de plus en plus oriental avec une diplomatie et une posture militaire clairement occidentale.

L'activisme chinois et les "intérêts vitaux" de la Chine

Cette zone est désormais inclue, d'après le "New York Times", dans le périmètre des "intérêts vitaux" de la Chine au même titre du Tibet et du Taïwan, bien qu'aucune déclaration officielle n'ait étalé cette position.

Or le Linkage entre la mer de Chine Méridionale et la façade maritime du Pacifique est inscrite dans l'extension des intérêts de sécurité chinois.

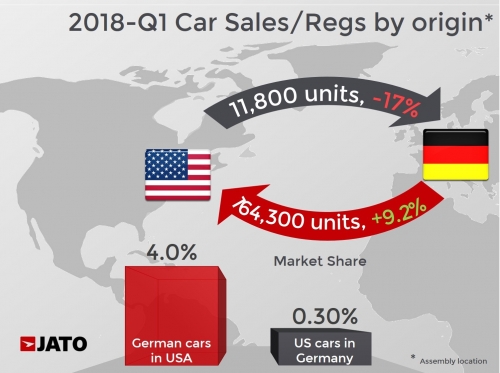

A travers les mers du sud et les détroits transite 50% des flux mondiaux d'échange, ce qui fait de cette aire maritime un théâtre de convoitises et de conflits potentiels, en raison des enjeux géopolitiques d'acteurs comme la Corée du Sud et le Japon qui constituent des géants manufacturiers et des pays dépendants des exportations.

Une des clés de lecture de cette interdépendance entre zones géopolitiques à fort impact stratégique, est le développement des capacités navales, sous-maritimes et de surface, de la flotte chinoise.

Le "Rapport 2010" et la mission historique des forces armées chinoises

L'évaluation des besoins de sécurité et de défense de la Chine est contenue dans le "Rapport 2010" concernant les forces armées du pays.

L'évaluation des besoins de sécurité et de défense de la Chine est contenue dans le "Rapport 2010" concernant les forces armées du pays.

Dans ce document, intitulé la "Mission historique des forces armées chinoises", énoncé par le Président Hu-Jintao dans sa relation au XVII Congrès du Parti Communiste en octobre 2017, le pouvoir suprême assigne à l'Armée populaire de Libération "le but de construire une nation prospère dotée d'une armée forte" et trace une perspective unifiée pour les capacité de combat et de projection de forces de l'APC. Il définit ainsi, au plan maritime, une stratégie d'interdiction à large spectre, qui n'est plus focalisée uniquement sur Taïwan et inclut désormais la Mer Jaune, dans laquelle patrouillent les flottes du Japon et de la Corée du Sud.

Bien que l'actuelle capacité d'interdiction de la flotte chinoise tienne à distance de la frontière maritime de la Chine les flottes étrangères, la mise en mer de la plus importante flotte sous-marine et amphibie d'Asie est en train de combler et de surmonter les vieilles carences d'un support satellitaire d'appui, pour l'identification des cibles mobiles.

Il s'agit là d'un point-clé opérationnel qui influence la stratégie militaire générale et les capacités de combat dans un contexte informatisé.

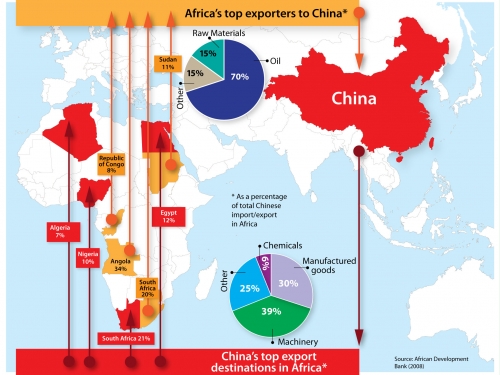

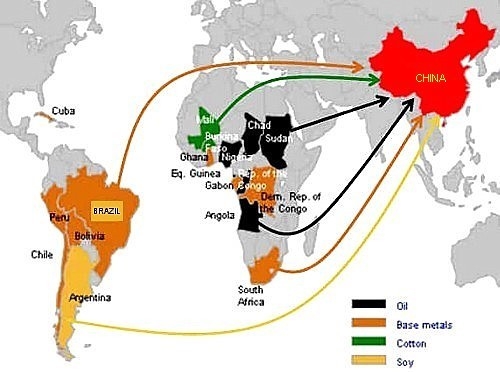

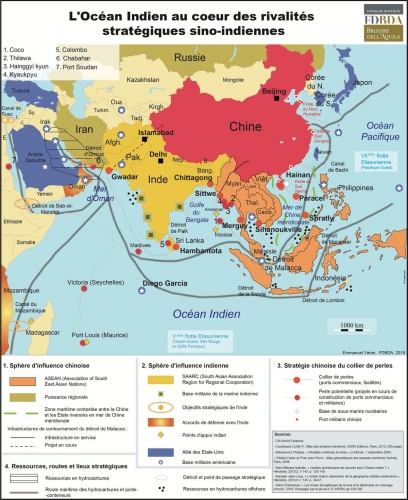

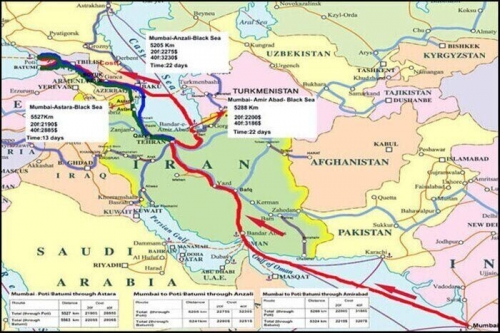

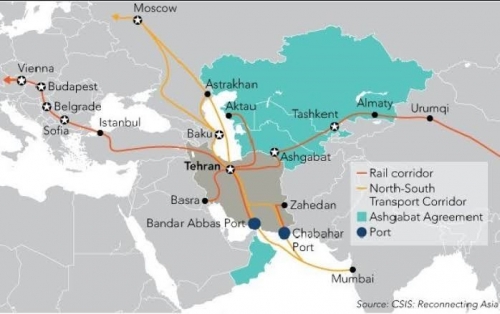

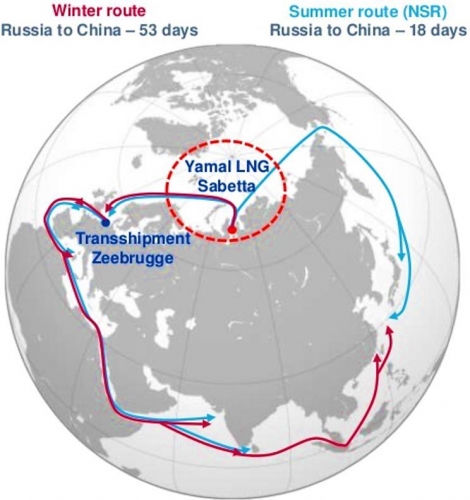

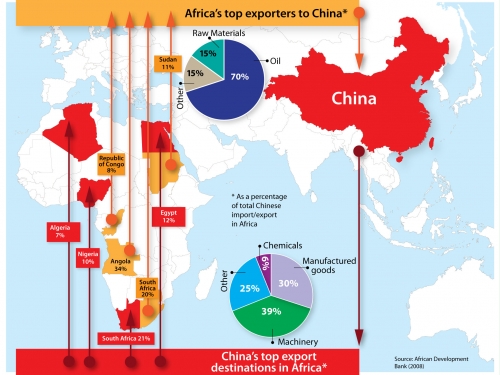

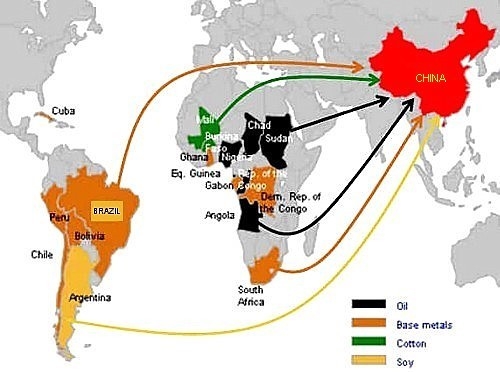

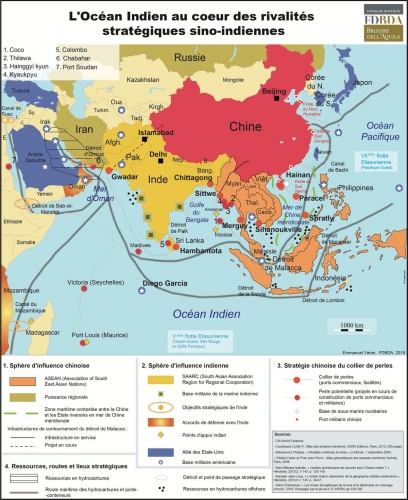

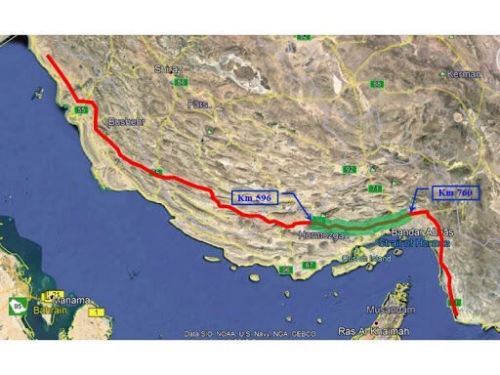

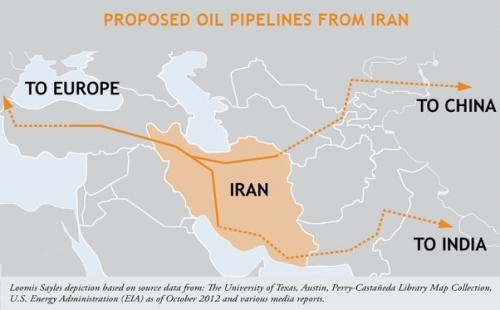

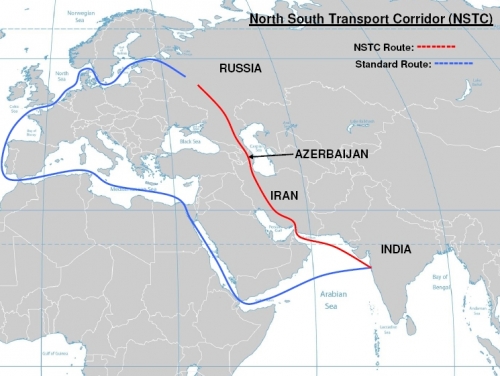

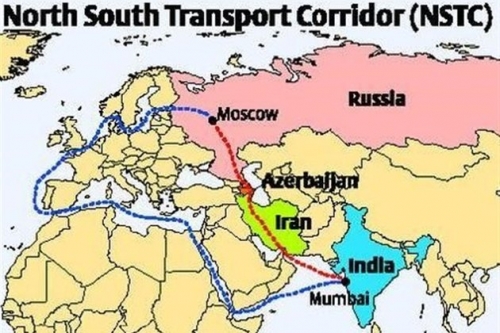

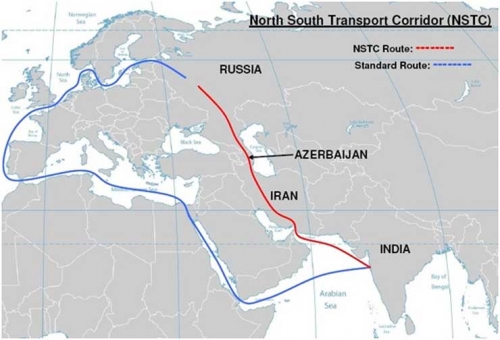

Au plan général, la prise de conscience de l’indépendance des rôles entre le premier atelier du monde et le premier consommateur d’énergie et de matières premières de la planète, part de l'acquisition d'un point de force, "la zone économique chinoise", premier pôle mondial de croissance après les USA et avant le Japon et l’Allemagne. Ces objectifs imposent à la Chine une exigence de sécurisation des voies maritimes qui lui dictent une stratégie, dite du "collier des perles", visant à jalonner le couloir maritime des importations pétrolières entre le Golfe et le détroit de Malacca, en modernisant le port de Gwadar et celui de Chittagong en Bangladesh. Cette stratégie a conduit également la Chine à adopter une politique d’approvisionnement et de sécurité énergétique duale, maritime et terrestre.

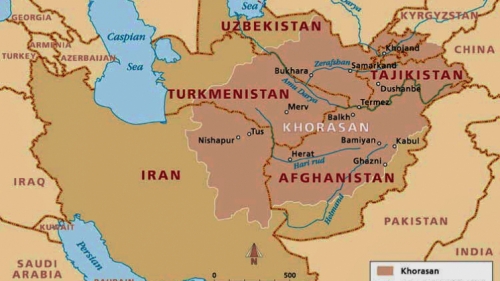

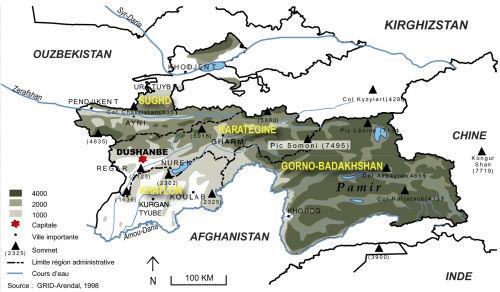

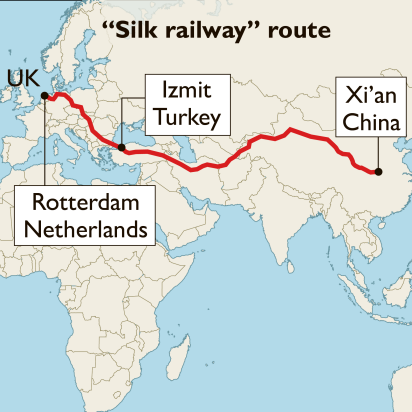

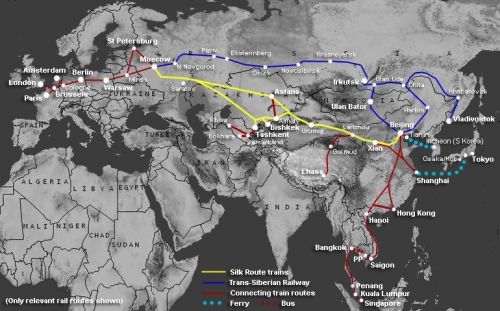

C'est à partir de cette exigence de sécurisation et d'autonomie stratégique qu'est né à Astana le projet OBOR (One Belt, one Road) de 2013, reprenant le parcours des vieilles Routes de la Soie.

Puissance de la terre, la Chine, rivalisant avec la puissance de la mer, entend manœuvrer, en cas de conflit, par les lignes intérieures du continent, sans dépendre d'une société extérieure à l'Asie.

En Eurasie, marquée par la diversités des États et des institutions, la dominance continentale est passée de la Russie à la Chine et le resserrement des alliances prendra la forme d'une activation du réseau des routes de la soie, modifiant le rapport des forces global.

En effet la guerre, selon Sun Tzu, ne se gagne pas principalement à la guerre ou sur le terrain des combats, mais dans sa préparation ou plus modernement dans sa planification. Autre naturellement est la victoire à la guerre selon son concept.

Les risques de conflit instaurent en tout cas une politique ambivalente, de rivalité-partenariat et d'antagonisme.

Il s’agit d’une politique qui a pour enjeu le contrôle de l’Eurasie et de l’espace océanique indo-pacifique, articulant les deux stratégies complémentaires du Heartland et du Rimland.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Aujourd'hui comme hier la compétition est devenue stratégique et la limitation des espaces de manœuvre consentis, a provoqué la lente création de deux blocs d'alliances rivales, auxquelles le nationalisme ou le souverainisme renaissants fournissent l'aliment idéologique pour les futurs belligérants. En ce qui concerne l'analogie historique, toujours imprécise, entre la situation européenne du XIXème et celle eurasienne du XXIème, la question de fond,qui préoccupait la Grande Bretagne de l'époque et les États-Unis d'aujourd'hui, était de savoir si la crise d'hégémonie et le problème de l'alternance qui iraient se manifester, étaient dus à la structure générale de la configuration du système ou à une politique spécifique de l'un ou de l'autre des deux "compétitors" et si, in fine, l'existence même de l'empire américain serait menacée et avec elle, celle de l'Occident et de la civilisation occidentale, jusqu'à sa variante russo-orthodoxe. Le Mémorandum Crowe, dans le cas de l'Allemagne montante et dans le cadre d'une analyse de la structure de la puissance, concluait pour l'incompatibilité entre les deux pouvoirs, britannique et allemand, et excluait la confiance et la coopération de la part de la Grande Bretagne. Ainsi l'importance des enjeux, interdisait à celle-ci d'assumer des risques et l'obligeait à prévoir le pire.

Aujourd'hui comme hier la compétition est devenue stratégique et la limitation des espaces de manœuvre consentis, a provoqué la lente création de deux blocs d'alliances rivales, auxquelles le nationalisme ou le souverainisme renaissants fournissent l'aliment idéologique pour les futurs belligérants. En ce qui concerne l'analogie historique, toujours imprécise, entre la situation européenne du XIXème et celle eurasienne du XXIème, la question de fond,qui préoccupait la Grande Bretagne de l'époque et les États-Unis d'aujourd'hui, était de savoir si la crise d'hégémonie et le problème de l'alternance qui iraient se manifester, étaient dus à la structure générale de la configuration du système ou à une politique spécifique de l'un ou de l'autre des deux "compétitors" et si, in fine, l'existence même de l'empire américain serait menacée et avec elle, celle de l'Occident et de la civilisation occidentale, jusqu'à sa variante russo-orthodoxe. Le Mémorandum Crowe, dans le cas de l'Allemagne montante et dans le cadre d'une analyse de la structure de la puissance, concluait pour l'incompatibilité entre les deux pouvoirs, britannique et allemand, et excluait la confiance et la coopération de la part de la Grande Bretagne. Ainsi l'importance des enjeux, interdisait à celle-ci d'assumer des risques et l'obligeait à prévoir le pire. L'évaluation des besoins de sécurité et de défense de la Chine est contenue dans le "Rapport 2010" concernant les forces armées du pays.

L'évaluation des besoins de sécurité et de défense de la Chine est contenue dans le "Rapport 2010" concernant les forces armées du pays.

Russia has been hit by the pandemic in a relatively mild form. I can not say that the measures the government has undertaken were (or are) exceptionally good but the situation is nevertheless not as dramatic as elsewhere. From the end of March, Russia began to close its borders with the countries most affected by coronavirus. Putin then mildly suggested citizens stay home for one week in the end of March without explaining what the legal status of this voluntary measure actually was. A full lockdown followed in the region most affected by pandemic. At the first glance the measures of the government looked a bit confused: it seemed that Putin and others were not totally aware of the real danger of the coronavirus, perhaps suspecting that Western countries had some hidden agenda (political or economic). Nonetheless, reluctantly, the government has accepted the challenge and now most regions are in total lockdown.

Russia has been hit by the pandemic in a relatively mild form. I can not say that the measures the government has undertaken were (or are) exceptionally good but the situation is nevertheless not as dramatic as elsewhere. From the end of March, Russia began to close its borders with the countries most affected by coronavirus. Putin then mildly suggested citizens stay home for one week in the end of March without explaining what the legal status of this voluntary measure actually was. A full lockdown followed in the region most affected by pandemic. At the first glance the measures of the government looked a bit confused: it seemed that Putin and others were not totally aware of the real danger of the coronavirus, perhaps suspecting that Western countries had some hidden agenda (political or economic). Nonetheless, reluctantly, the government has accepted the challenge and now most regions are in total lockdown. On one hand, many experts claim that the disease has artificial origin and was leaked (accidently or on purpose) as an act of biological warfare. Precisely in Wuhan there is allegedly one of the top biological laboratories in China. In the US, many people, including President Trump, pursue this hypothesis or suggest this is all part of the plan of a select group of globalists (like Bill Gates, Zuckerberger, George Soros and so on) to expand the deadly virus in order to impose the vaccination and eventually introduce microchips into human beings around the world. The surveillance methods already introduced to control and monitor infected people and even those who are still healthy seem to confirm such fears. There is a conspiracy theory which suggests that China has been set up as a scapegoat. We might laugh at the inconsistency of such myths and their lack of proof, but belief in such theories – especially during moments of deep crises – are easily accepted and become the basis for real actions, and could even lead to war.

On one hand, many experts claim that the disease has artificial origin and was leaked (accidently or on purpose) as an act of biological warfare. Precisely in Wuhan there is allegedly one of the top biological laboratories in China. In the US, many people, including President Trump, pursue this hypothesis or suggest this is all part of the plan of a select group of globalists (like Bill Gates, Zuckerberger, George Soros and so on) to expand the deadly virus in order to impose the vaccination and eventually introduce microchips into human beings around the world. The surveillance methods already introduced to control and monitor infected people and even those who are still healthy seem to confirm such fears. There is a conspiracy theory which suggests that China has been set up as a scapegoat. We might laugh at the inconsistency of such myths and their lack of proof, but belief in such theories – especially during moments of deep crises – are easily accepted and become the basis for real actions, and could even lead to war.

Whitlam was threatening to close Pine Gap spy station; the United States lease was due to expire in December 1975. The Governor General sacked him in November 1975, the day before he was to make an announcement in the Australian Parliament about Pine Gap.

Whitlam was threatening to close Pine Gap spy station; the United States lease was due to expire in December 1975. The Governor General sacked him in November 1975, the day before he was to make an announcement in the Australian Parliament about Pine Gap.

This is an extremely serious attempt to theorize Belt & Road’s immense complexity – especially considering China’s flexible, syncretic approach to policymaking, quite bewildering for Westerners. To reach his goal, Garlick gets into Tang Shiping’s social evolution paradigm, delves into neo-Gramscian hegemony, and dissects the concept of “offensive mercantilism” – all that as part of an effort in “complex eclecticism.”

This is an extremely serious attempt to theorize Belt & Road’s immense complexity – especially considering China’s flexible, syncretic approach to policymaking, quite bewildering for Westerners. To reach his goal, Garlick gets into Tang Shiping’s social evolution paradigm, delves into neo-Gramscian hegemony, and dissects the concept of “offensive mercantilism” – all that as part of an effort in “complex eclecticism.”