Fiume à l'avant-garde de l'histoire

Ex: http://idiocratie2012.blogspot.com

Les manifestants de « La nuit debout » sont d’une telle pauvreté inventive, entre slogans éculés de la gauche radicale et pratiques désuètes de la démocratie participative, que nous leur proposons, en guise de méditation – si ce mot a encore un sens dans leurs esprits conformistes –, une décharge d’adrénaline, une plus-que-vie jouissive qu’ils ont peu de chances de rencontrer dans leurs assemblées « conviviales » dont les gestes débilitants ont même été jusqu’à remplacer les paroles creuses.

Ayant atteint ma destination, j’offris des roses rouges au Frate Francesco au Vatican, je lançais plus de roses rouges, comme preuve d’amour, pour la Reine et le Peuple au dessus du Quirinal. Sur le Montecitorio [le parlement italien], je lançais un ustensile de fer rouillé attaché à un chiffon rouge, avec quelques navets attachés à la poignée et un message : Guido Keller – Entrepris sur les ailes de la Splendeur – offre au parlement et au gouvernement qui a régné grâce aux mensonges et à la peur depuis quelques temps, une allégorie tangible de leur valeur.

Rome, 14e jour du 3e mois de la Régence.[1]

Voilà comment Guido Keller – aventurier et aéro-poète futuriste – raconte le « bombardement » du parlement italien qu’il accomplit le 14 novembre 1920 à bord de son monoplan Ansaldo SVA 5.2, afin de protester contre la signature du traité de Rapallo le 12 novembre 1920 par l’Italie et la Yougoslavie. L’équipée « aéro-romantique » du principal lieutenant de Gabrielle D’Annunzio marquait symboliquement la fin de l’une des entreprises les plus surprenantes de l’après-guerre : la prise et l’occupation de la ville frontière de Fiume et la transformation, durant un an, de la cité en un vaste champ d’expérimentation esthético-politique, que l’on peut considérer comme une matrice aussi bien de l’avant-gardisme radical européen que des nouveaux phénomènes politiques qui émergeaient à la faveur du règlement de la première guerre mondiale, en particulier le fascisme italien.

La ville de Fiume, ou Rijeka en croate, avait bénéficié en 1719 d’un statut de port franc autonome accordé par décret par Charles VI d'Autriche puis par l'impératrice Marie-Thérèse. En 1848, Fiume avait été brièvement occupée par la Croatie avant de retrouver son indépendance en 1868. Ville par excellence internationale, Fiume était, en 1919, peuplée d’Italiens, de Croates, de Hongrois ou d’Allemands. L’italien restait la langue dominante et le dialecte local, le « fiumien », se rapprochait du vénitien, tandis que le dialecte des campagnes alentours correspondait plus à une variante du croate. Ce métissage conférait à la ville une identité très forte et Fiume pouvait presque être considérée comme un exemple en miniature du multiculturalisme qui avait marqué, et aussi miné, l’empire austro-hongrois.

La ville de Fiume, ou Rijeka en croate, avait bénéficié en 1719 d’un statut de port franc autonome accordé par décret par Charles VI d'Autriche puis par l'impératrice Marie-Thérèse. En 1848, Fiume avait été brièvement occupée par la Croatie avant de retrouver son indépendance en 1868. Ville par excellence internationale, Fiume était, en 1919, peuplée d’Italiens, de Croates, de Hongrois ou d’Allemands. L’italien restait la langue dominante et le dialecte local, le « fiumien », se rapprochait du vénitien, tandis que le dialecte des campagnes alentours correspondait plus à une variante du croate. Ce métissage conférait à la ville une identité très forte et Fiume pouvait presque être considérée comme un exemple en miniature du multiculturalisme qui avait marqué, et aussi miné, l’empire austro-hongrois.

En 1919, le premier ministre Vittorio Emanuele Orlando avait quitté Paris, où se tenait la conférence de la paix entre les vainqueurs de la Première Guerre mondiale, ulcéré par les décisions prises à l’égard de son pays. Démentant leurs promesses de 1915, les alliés avaient en effet ignoré les conditions auxquelles avait été négociée l’entrée en guerre de l’Italie à leurs côtés contre les puissances centrales[2] et notamment l’attribution à l’Italie des fameux territoires irredente, dans lesquels était comprise Fiume. Néanmoins, le président du conseil, Francesco Saverio Nitti, plus préoccupé par les troubles sociaux qui secouaient l’Italie du Biennio rosso[3], avait accepté les conditions offertes à l’Italie par les puissances alliées et signé officiellement l’armistice le 10 septembre 1919.

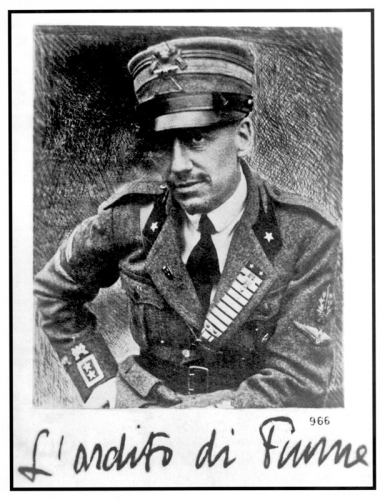

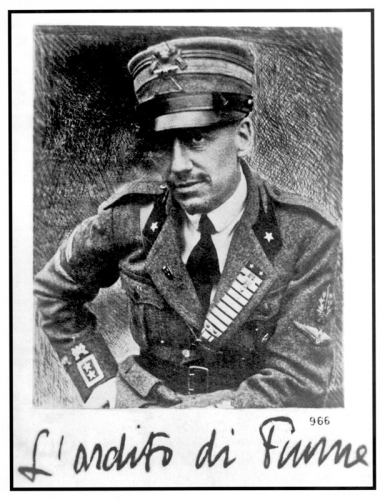

Parmi toutes les voix qui s’étaient élevées à ce moment pour dénoncer la politique de Nitti, celle du « poète-guerrier » Gabrielle D’Annunzio semblait couvrir toutes les autres. Non content de traiter publiquement Nitti de cagoia, D’Annunzio, entouré d’un petit groupe de fidèles et à la tête d’une véritable armée personnelle de soldats démobilisés et d’aventuriers, prit la décision de marcher sur la ville de Fiume, dont il expulsa sans difficultés les corps expéditionnaires américains, anglais et français qui l’occupaient, dans le but de restituer la ville à l’Etat italien. Le gouvernement italien déçut cependant ses attentes en refusant son offre. D’Annunzio pris alors la décision d’instaurer à Fiume un gouvernement basé sur une charte rédigée par l’anarcho-syndicaliste Alceste de Ambris, tenant lieu de constitution pour la cité de Fiume, et prévoyant la création d’une « anti-société des nations » alliée de tous les « peuples opprimés de la terre ». La « Régence du Carnaro », ainsi créée et dénommée par D’Annunzio, inaugurait une expérience politique unique en Europe qui allait s’étendre de septembre 1919 à décembre 1920. Autour de D’Annunzio se pressaient les nouveaux maîtres de la ville de Fiume : les arditi[4], mais également des futuristes, des dadaïstes, des anarchistes, des monarchistes, et toutes sortes d’aventuriers de tout acabit. La Russie bolchevique fut le seul Etat à reconnaître l’existence de cette Cité-Etat insurrectionnelle dans laquelle les notables locaux observaient, terrifiés mais impuissants, leur cité se transformer en une immense scène de théâtre où l’on organisait des mises en scènes baroques en l’honneur du Vate et des débats publics dans lesquels on discutait d’amour libre, de libération de la femme, ou d’abolition des prisons. « La mascarade, la raillerie et la dérision leur servent de langage, écrit Claudia Salaris. Futuristes, dadaïstes et anarchistes expérimentent le laboratoire fiumain, en discutant de thèmes aussi osés pour l’époque que la libération de la femme, la drogue, l’abolition de l’argent et des prisons. » [5]

On ne considère en général l’équipée de Fiume que comme une démonstration proto-fasciste de l’esprit de revanche qui anime une partie des élites d’une Italie mutilée par la victoire. Or, il convient d’appréhender l’épisode sous un angle beaucoup moins réducteur. Dès la fondation de la Régence du Carnaro, les principaux artisans de l’aventure fiumienne considèrent en effet leur entreprise comme le point de départ d’un mouvement révolutionnaire qui doit répondre aux aspirations à la fois politiques, mais aussi sociales et esthétiques les plus radicales des avant-gardes et des déclassés de l’après-guerre, conscients de faire partie d’un pays dévasté qui n’appartient plus, quant à lui, qu’à l’arrière-garde des vainqueurs. Mélange hétéroclite de revendications nationalistes, de passions anarchistes et de sensibilité libertaire, agrégat tumultueux de soldats en rupture de ban, d’aventuriers, d’artistes de la grenade, de futuristes enragés, de dadas de combat, de monarchistes désespérés, de criminels fantasques, de poètes en uniforme, de révolutionnaires sans cause et de quelques véritables candidats à l’asile psychiatrique, la « république du Carnaro », décrétée par D’Annunzio du 12 septembre 1919 au 30 décembre 1920 a constitué une expérience unique dans le chaos de l’Europe d’après-guerre. Proclamée lieu de l’amour et de la fête perpétuelle, elle attise la curiosité de Mussolini qui reste dubitatif, mais n’oublie pas de tirer pour lui-même les leçons essentielles du théâtre permanent organisée par D’Annunzio à travers sa révolution. Elle suscite au contraire le dédain de Marinetti qui ne voit dans les activistes de Fiume qu’une collection d’agitateurs jetant dans la même mêlée hystérique anarchistes, futuristes et monarchistes. La charte du Carnaro, rédigée par l’anarcho-syndicaliste italien Alceste De Ambris, montre la méfiance des nouveaux maîtres de Fiume à l’égard de l’Etat moderne et entend se fonder véritablement sur la souveraineté populaire mais elle inscrit aussi dans la nouvelle constitution un certain nombre d’avancées sociales difficilement imaginables pour l’époque. Outre le fait que la charte se soit rendue célèbre pour avoir déclaré la musique comme principe fondamental d'État, elle autorise le divorce, accorde le droit de vote aux femmes, légalise l'homosexualité, l'usage de stupéfiants et le naturisme. Le poète belge Léon Kochnitzky, proche ami de D’Annunzio, voit quant à lui le « fiumanisme » comme une entreprise révolutionnaire universelle, propre à renverser l’ordre établi du vieux monde :

Rassembler en une formation compacte les forces de tous les peuples opprimés de la terre, nations, races…etc…etc…Et utiliser ceci pour combattre et triompher des oppresseurs et des impérialistes qui veulent faire prévaloir leurs intérêts financiers sur les sentiments les plus sacrés des hommes : la foi, l’amour de la patrie, la liberté individuelle et la dignité sociale.[6]

Ludovico Toeplitz, cinéaste italien et polyglotte, était quant à lui chargé des relations extérieures de la régence du Carnaro et, à ce titre, il mit également tout en œuvre pour faire de la ligue de Fiume une véritable « antisociété des nations », selon le vœu même de Gabrielle D’Annunzio :

Ludovico Toeplitz, cinéaste italien et polyglotte, était quant à lui chargé des relations extérieures de la régence du Carnaro et, à ce titre, il mit également tout en œuvre pour faire de la ligue de Fiume une véritable « antisociété des nations », selon le vœu même de Gabrielle D’Annunzio :

J’ai pris contact avec tous les mécontents de divers pays autour du monde: avec Zagloul Pascia en Egypte, pas encore premier ministre mais leader du parti des Fellah ; avec Kemal Pacha, le puissant leader du parti des Jeunes Turcs, qui prendra sans doute très prochainement le pouvoir. A Fiume, nous avons fondé l’Anti-société des Nations, en opposition à l’inique traité de Versailles.[7]

Le ravitaillement de cette cité pirate moderne, assiégée dès le début de l’année 1920 par l’armée italienne, était assuré par d’audacieux coups de mains, supervisés par le principal lieutenant de D’Annunzio : Guido Keller, un personnage si fantasque qu’il ne semble encore aujourd’hui n’avoir pu exister que dans un roman. Ancien as de l’aviation italienne, aéropoète futuriste et mystique fantasque, Keller avait réinventé dans les airs une forme de duel courtois consistant à prendre le dessus sur son adversaire avant de le laisser avec noblesse prendre la fuite. Il était également le fondateur de la confrérie des cheveux coupés, que l’on intégrait après avoir démontré que l’on était capable de se couper les cheveux en vol, et avait fait installer un service à thé dans son avion qu’il pilotait d’ailleurs la plupart du temps en pyjama.

A Fiume, au beau milieu de la joyeuse anarchie constitutionnellement instaurée par la Régence du Carnaro, il n’était pas rare de voir Keller passer une partie de la journée dans le plus simple appareil ou éventuellement grimé en Poséidon. Il dormait dans les arbres, était végétarien et considérait comme une manifestation de joie tout à fait opportune le fait de faire exploser une grenade un peu à tout propos. « Quand il avait des moments de libertés, écrivait Atlantico Ferri dans la Testa di ferro, il montait dans l’arbre, complètement nu, et, dans son aérienne demeure remplissait toutes les fonctions – y compris les plus naturelles…- que la plupart des hommes remplissent au niveau du sol. » Epaisse chevelure noire, barbe méphistophélique, Keller semble presque plus tenir du faune que de l’être humain. Il semble d’ailleurs que l’un de ses passe-temps favoris était de faire peur aux jeunes couples qui allaient s’embrasser près du cimetière de Fiume en allant y pousser la nuit des hurlements de bêtes au point que le commandante D’Annunzio alla jusqu’à mandater une compagnie de soldats pour prouver qu’aucun mort-vivant ou loup-garou ne se cachait là. Spécialiste des coups de main et actes de piraterie par lesquels la cité survivait, Keller rédigea également une circulaire invitant tous les fous d’Italie et pensionnaires d’asile à demander leur libération pour rejoindre Fiume[8] et fut aussi le fondateur de la société secrète Yoga qui entretenait en Europe des relations avec les futuristes de tous bords et de toutes nationalités ainsi qu’avec des dadaïstes allemands[9] ou les bolcheviques russes et hongrois. Lénine avait déclaré avant la guerre qu’il considérait Gabrielle D’Annunzio comme le seul véritable leader révolutionnaire en Italie[10] ; il avait omis de mentionner l’indispensable compagnon du Vate, Guido Keller, capable aussi bien d’organiser un assaut romantique et théâtral – intitulé « Le château d’Amour » - du palais de la présidence de Fiume, que de s’emparer de cinquante chevaux au nez et à la barbe de l’armée italienne. Comme d’Annunzio, Keller était convaincu que Fiume était devenue à la fois la « cité de l’Holocauste » et la « cité de l’Amour », l’épicentre du séisme qui devait ébranler l’histoire, libérer les peuples et renverser les Etats assassins et les gouvernements d’imposteurs.

L’épisode fiumain, anachroniquement moderne, semble à la fois suspendu hors du temps et en même temps installé au cœur, au point charnière, de l’histoire européenne. Les révolutionnaires de Fiume réussissent à instaurer le complet envahissement de l’existence par l’art, et dans le même temps la complète politisation de l’art. Le geste de révolte devient manifestation artistique et la révolution, la guerre, le combat une manifestation esthétique : l’allégorie ultime du mouvement de la vie, de la mort et du chaos. Les futuristes, les dadas de combat et les poètes révolutionnaires monarchistes, anarchistes ou nationalistes que l’on pouvait rencontrer à Fiume ont eu des prédécesseurs en plein XIXe siècle dont ils reprennent les slogans, reproduisent les poses et rééditent en partie les engagements, à l’échelle d’une ville et d’une expérience un peu folle au cours de laquelle esthétique et action ne forment qu’un seul geste.

L’épisode fiumain, anachroniquement moderne, semble à la fois suspendu hors du temps et en même temps installé au cœur, au point charnière, de l’histoire européenne. Les révolutionnaires de Fiume réussissent à instaurer le complet envahissement de l’existence par l’art, et dans le même temps la complète politisation de l’art. Le geste de révolte devient manifestation artistique et la révolution, la guerre, le combat une manifestation esthétique : l’allégorie ultime du mouvement de la vie, de la mort et du chaos. Les futuristes, les dadas de combat et les poètes révolutionnaires monarchistes, anarchistes ou nationalistes que l’on pouvait rencontrer à Fiume ont eu des prédécesseurs en plein XIXe siècle dont ils reprennent les slogans, reproduisent les poses et rééditent en partie les engagements, à l’échelle d’une ville et d’une expérience un peu folle au cours de laquelle esthétique et action ne forment qu’un seul geste.

La mise en place du gouvernement de Fiume s’accompagna de la prise de pouvoir partielle au sein de la cité de la société Yoga qui avait pour charge d’affirmer la vocation avant-gardiste et internationaliste du mouvement fiumien. Dans la Testa di ferro, revue de la société Yoga animée par le futuriste Mario Carli, surnommé « Notre bolchevisme » ou « Le petit père du bolchevisme », on célébrait « la cité italienne de Fiume – cité de la vie nouvelle – libération de tous les opprimés (peuples, classes, individus – discipline de l’esprit contre toute discipline formelle – destruction de toutes les hégémonies, dogmes, conservatismes et parasitismes – creuset des énergies nouvelles – peu de mots, beaucoup de substance. » [11] L’Unione Yoga appelait de ses vœux un « ordre lyrique » capable à la fois de libérer les peuples et la créativité de l’individu en combattant toute forme d’aliénation. « Révolutionnaires non contre un parti ou pour un parti, mais révolutionnaires contre ce que nous sommes », proclamait le premier numéro de la revue, publié le 13 novembre 1920. Les armes que se donnaient les membres de Yoga relevaient de l’art de la rhétorique tout autant que de celui de la guerre. Il s’agissait de « vaincre l’adversaire par l’ironie, l’exposer au ridicule en lui ôtant toute autorité barbante, ainsi que sa maladresse le méritait »[12], en d’autre terme, d’opposer l’ironie au conservatisme et à la pose :

Contre les lunettes dorées à branches

Contre les ‘Adieu mon cher’

Contre les ‘r’ gorgés

Contre la pose

Contre la folie comme il faut, organisée à domicile sérieuse et spirituelle et à des fins exhibitionnistes.[13]

La Yoga a transformé le temps d’un coup d’Etat la cité de Fiume en théâtre permanent, multipliant les coups de main et les interventions publiques et spontanées que les avant-gardistes nommeront plus tard happening, en pleine rue, sous les yeux d’une population éberluée et au grand dam des notables de la ville. On organisait aussi des consultations publiques au cours desquelles l’on abordait tous les sujets, où l’on parlait de tout, vite, avec enthousiasme pour ceux qui s’imaginaient que la parole libérée accélérerait la chute du vieux monde ou simplement avec l’ardeur des désespérés qui savaient au fond que la « cinquième saison du monde » s’achèverait sans doute bientôt :

Au cœur de la vieille ville de san Vito se trouve la place où nous nous retrouvons. Un grand arbre protège de sa plénitude l’harmonie du parler.

(…)

Un soir, on parlait de l’abolition de l’argent, un autre de l’amour libre, un autre encore, de l’homme politique, du règlement de l’armée, de l’abolition des prisons, de l’embellissement de la ville.

(…)

C’est ainsi que la conversation coule, admirable, sur la vieille place, dans une harmonie parfaite entre la prostituée et le poète, entre le navigateur et l’antiquaire, entre le banquier et l’intellectuel, tandis que la présence des animaux, dans leur mutisme, est appréciée.[14]

Alors que Margherita Keller Besozzi, cousine de Guido Keller et figure féministe décrétait que : « La femme de Fiume n’est autre que la mère de la femme moderne », les révolutionnaires, par l’entremise de leur revue, lançaient des mots d’ordres toujours plus radicaux, à mesure que semblait se rapprochait l’issue tragique de l’aventure de Fiume :

Bloquez donc les trains et les navires, inondez les mines obscènes, fermez les ateliers (cages de fous inventées par des diables), mettez le feu aux bureaux, aux ministères, aux Bourses où l’on gagne ce qui ne vaut pas la peine d’être gagné…et sauvez la vie ! […] Avec quelle volupté je mettrais le feu à vos stupides « académies », à vos putrides « musées », pleins des restes d’une beauté fanées (créées par des ouvriers pour des princes), que vous n’êtes plus capables de comprendre, à vos « écoles d’art », où en grande pompe des cadavres ensevelis enseignent à ceux qui n’ont pas de génie comment on fait pour devenir plus médiocre que son maître.[15]

Le « Noël sanglant » du 24 décembre 1920 mit fin à l’aventure de Fiume et à la tentative de révolution ésotérique et an-historique de D’Annunzio, contraint d’évacuer la ville après une semaine de rudes combats contre l’armée italienne. Le Vate terminera sa vie presque assigné à résidence dans sa demeure du lac de Garde, devenu invalide après être mystérieusement « tombé » de sa fenêtre dans la nuit du 13 au 14 août 1922.

Le « Noël sanglant » du 24 décembre 1920 mit fin à l’aventure de Fiume et à la tentative de révolution ésotérique et an-historique de D’Annunzio, contraint d’évacuer la ville après une semaine de rudes combats contre l’armée italienne. Le Vate terminera sa vie presque assigné à résidence dans sa demeure du lac de Garde, devenu invalide après être mystérieusement « tombé » de sa fenêtre dans la nuit du 13 au 14 août 1922.

Pour Guido Keller, l’échec de Fiume fut le début d’une errance qui le mènera de l’Italie à l’Amérique du sud, où il tentera encore de donner vie à ses rêves libertaires. Il tenta d’abord de mettre en place une pièce de cirque aérien intitulée La conquête du soleil puis s’exila en Turquie pour y monter une école de pilotage, avant de devenir officier de l’escadrille militaire de Cyrénaïque à Benghazi. Abattu par les rebelles, il sympathisa avec eux avant d’embarquer pour l’Amérique du sud et le Pérou - « patrie de la coca – princesse généreuse » - où il se lança dans une tentative révolutionnaire, écrasée dans le sang. « Les morts sont semblables à ceux de Fiume, écrit-il à Sandro Pozzi. Je suis le chemin tracé par le destin : j’ai cherché ma lointaine terre tranquille et, comme Ulysse, j’ai échangé un cheval borgne contre une monture aveugle. » Le dernier acte de son existence le vit s’associer au peintre et sculpteur Hendrik Andersen afin de créer une « cité de vie » sur une île perdue de la mer Egée où aucune loi ou forme d'ordre ne devait avoir cours et où seuls les artistes et les aventuriers auraient été autorisés à vivre. Le projet n’aboutira jamais. En 1929, Guido Keller décède, victime d’un accident de moto sur une route d’Italie, comme Thomas Edward Lawrence, dit Lawrence d’Arabie, six ans plus tard. D’Annunzio meurt quant à lui en 1938 et Mussolini lui accorde des funérailles nationales, dont il se serait sans doute bien passé, lui qui était devenu un indésirable politique assigné à résidence par le régime fasciste. Le temps n’est plus aux rêveurs et aux poètes et dans une Europe livrée à nouveau à l’affrontement des empires, les idéologies carnivores dévoreront ensemble les utopies et les peuples.

Notes:

[1] Guido KELLER. Feuillets autographes. in Janez JANSA. Il porto dell’amore. Texts by Domenico Cuarenta. Quis contra nos 1919-2019. www.reakt.org/fiume

[2] Des négociations qui prévoyaient que l’Italie, en échange de sa participation au conflit, obtienne, après la guerre les régions : du Trentin, du Tyrol du Sud jusqu'au Brenner, de l'Istrie, de la Dalmatie, des villes de Trieste, Gorizia et Gradisca, d'un protectorat sur l'Albanie, de la souveraineté sur le port de Vlora, de la province de Antalya en Turquie, en plus du Dodécanèse et d'autres colonies en Afrique de l'Est et Libye. La quasi-totalité de ces accords seront ignorés à la conférence de Paris en 1919.

[3] Cette expression désigne les deux années, de 1918 à 1920, qui après la fin de la guerre sont marquées en Italie par une très forte agitation sociale et la crainte d’une prise de pouvoir par les communistes, d’où le nom de « Biennale rouge ».

[4] Les « ardents ». Compagnons de D’Annunzio, pour la plupart d’anciens soldats, dont l’uniforme, le cri de ralliement, me ne frego, et l’organisation devaient par la suite grandement inspirer Mussolini lors de la création des faisceaux de combat.

[5] Claudia SALARIS. A la fête de la révolution. Artistes et libertaires avec D'Annunzio à Fiume. Paris, Éditions du Rocher, 2006. p. 11

[6] De Felice, D’Annunzio politico 1918-1938, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 1978, p. 73. Cité par Janez Jansa. Il porto dell’amore. Aksioma - Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana

[7] Ludovico Toeplitz, Cial a chi tokka, Milano, Edizioni Milano Nuova, 1964, p. 49

[8] A la même époque, Marinetti proclame : « Il est temps que l’on fasse aussi de la folie (bouleversement des rapports logiques) un art conscient et évolué. » Ce genre de déclarations rappelle bien entendu les déclarations surréalistes et les tentatives réalisées en Allemagne par le SPK à la fin des années 70 pour libérer les hôpitaux psychiatriques. Tentatives qui s’étaient soldées au final par l’intervention musclée du GIGN allemand dans un établissement « autogéré par les malades. »

[9] L’expédition de Fiume fut d’ailleurs saluée avec chaleur par le club Dada de Berlin, dans un télégramme envoyé au Correrre Del Sierra : « Conquête est une grande action dadaïste, et nous emploierons tous les moyens pour assurer sa reconnaissance. L’atlas mondial Dada Dadaco reconnaît déjà Fiume comme une ville italienne. »

[10] Le gouvernement illégal de Fiume entreprit d’ailleurs très tôt de lier contact avec la Russie bolchevique qui fut le seul état à reconnaître son existence.

[11] Phrase emblématique apparaissant dans nombre de numéros de La Testa di ferro.

[12] Sandro Pozzi dans La Testa di ferro.

[13] Manifeste-affiche : « Fondation à Fiume de la Yoga »

[14] Giovanni Comisso. Il Il porto dell'amore. Longanesi [Biblioteca di narratori]. 2011.

[15] Yoga n°2. 20 novembre 1920.

So what exactly is fascism? This question, Gottfried insists, “has sometimes divided scholars and has been asked repeatedly ever since Mussolini’s followers marched on Rome in October 1922.” Gottfried presents several adjectives, mostly gleaned from the work of others, to describe fascism: reactionary, counterrevolutionary, collectivist, authoritarian, corporatist, nationalist, modernizing, and protectionist. These words combine to form a unified sense of what fascism is, although we may never settle on a fixed definition because fascism has been linked to movements with various distinct characteristics. For instance, some fascists were Christian (e.g., the Austrian clerics or the Spanish Falange) and some were anti-Christian (e.g., the Nazis). There may be some truth to the “current equation of fascism with what is reactionary, atavistic, and ethnically exclusive,” Gottfried acknowledges, but that is only part of the story.

So what exactly is fascism? This question, Gottfried insists, “has sometimes divided scholars and has been asked repeatedly ever since Mussolini’s followers marched on Rome in October 1922.” Gottfried presents several adjectives, mostly gleaned from the work of others, to describe fascism: reactionary, counterrevolutionary, collectivist, authoritarian, corporatist, nationalist, modernizing, and protectionist. These words combine to form a unified sense of what fascism is, although we may never settle on a fixed definition because fascism has been linked to movements with various distinct characteristics. For instance, some fascists were Christian (e.g., the Austrian clerics or the Spanish Falange) and some were anti-Christian (e.g., the Nazis). There may be some truth to the “current equation of fascism with what is reactionary, atavistic, and ethnically exclusive,” Gottfried acknowledges, but that is only part of the story.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Durante estos años, y bajo el influjo permanente de los escritos de

Durante estos años, y bajo el influjo permanente de los escritos de  Evola mantiene un discurso constante en el que asocia todas las formas de

Evola mantiene un discurso constante en el que asocia todas las formas de  El otro gran representante de la Tradición Romana es Guido De Giorgio, el principal discípulo del pensamiento de René Guénon en Italia, un hombre oscuro, tanto en su trayectoria vital como en aquella intelectual, de una moral espartana, y definido por el propio Evola como un «iniciado en estado salvaje». Su principal obra, La Tradición Romana, fue publicada póstumamente, en el año 1973, y todavía a día de hoy existen obras inéditas del autor, que no han visto la luz todavía. Las premisas del pensamiento de Giorgio, como ocurre con Guénon, parten de un punto de vista absoluto, metafísico, sacro y Tradicional. No obstante su visión de la Tradición como tal cuenta con la confluencia de muy variadas influencias, entre las cuales podemos encontrar a los neoplatónicos, cristianos, hinduistas y musulmanes. A las citadas fuentes que nutren su pensamiento podemos añadir una peculiar forma de escribir, muchas veces teñida de una cierta iluminación, de una intuición muy sutil, y lo enigmáticos que resultan muchos de los pasajes de su obra. Un ejemplo de esta confluencia de ideas y doctrinas la vemos en sus consideraciones, de matiz claramente cristiano, en las que habla de la fe como la base de la Tradición por excelencia, al tiempo que contempla la concepción no dualista del Principio Supremo en lo que es un concepto de impronta hinduista. Sin embargo, la perspectiva islámica es la que toma mayor protagonismo en el conjunto de sus ideas, y es precisamente en base a esta

El otro gran representante de la Tradición Romana es Guido De Giorgio, el principal discípulo del pensamiento de René Guénon en Italia, un hombre oscuro, tanto en su trayectoria vital como en aquella intelectual, de una moral espartana, y definido por el propio Evola como un «iniciado en estado salvaje». Su principal obra, La Tradición Romana, fue publicada póstumamente, en el año 1973, y todavía a día de hoy existen obras inéditas del autor, que no han visto la luz todavía. Las premisas del pensamiento de Giorgio, como ocurre con Guénon, parten de un punto de vista absoluto, metafísico, sacro y Tradicional. No obstante su visión de la Tradición como tal cuenta con la confluencia de muy variadas influencias, entre las cuales podemos encontrar a los neoplatónicos, cristianos, hinduistas y musulmanes. A las citadas fuentes que nutren su pensamiento podemos añadir una peculiar forma de escribir, muchas veces teñida de una cierta iluminación, de una intuición muy sutil, y lo enigmáticos que resultan muchos de los pasajes de su obra. Un ejemplo de esta confluencia de ideas y doctrinas la vemos en sus consideraciones, de matiz claramente cristiano, en las que habla de la fe como la base de la Tradición por excelencia, al tiempo que contempla la concepción no dualista del Principio Supremo en lo que es un concepto de impronta hinduista. Sin embargo, la perspectiva islámica es la que toma mayor protagonismo en el conjunto de sus ideas, y es precisamente en base a esta

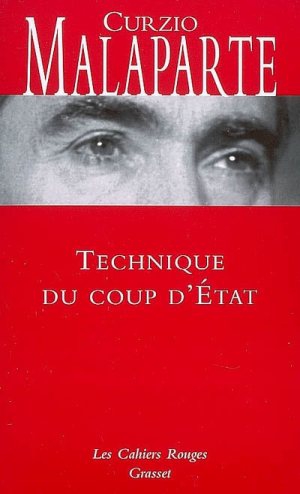

Quando – si era nel 1921 – Malaparte scrisse il dirompente libro “Viva Caporetto!”, poi intitolato “La rivolta dei santi maledetti”, che rileggeva dalle fondamenta la fenomenologia di quella drammatica sconfitta, fece un’operazione di vera rottura ideologica, spingendo la provocazione ben oltre gli steccati della polemica antiborghese, osando toccare il nervo sensibile del superficiale orgoglio nazionale allora egemone in Italia: della rovinosa rotta dell’ottobre 1917 (che il generale Cadorna e molti osservatori attribuirono a un insieme di renitenza e insubordinazione di masse di fanti che in realtà erano abbrutiti dall’inumana vita di trincea) egli fece il simbolo di una rivolta politica in piena regola. Una volta vista non dall’ottica degli alti comandi e dei “bravi cittadini”, ma da quella del fantaccino analfabeta, quella sconfitta, che era un tabù rimosso dall’ipocrita mentalità borghese, diventava un atto politico e la massa dei disfattisti assurgeva a sua volta al rango di soggetto politico. Dando vita, come ha scritto Mario Isnenghi, a qualcosa di inedito e di potenzialmente incendiario, cioè “una interpretazione rivoluzionaria della prima guerra mondiale, della storia delle masse e della psicologia collettiva dentro la guerra”.

Quando – si era nel 1921 – Malaparte scrisse il dirompente libro “Viva Caporetto!”, poi intitolato “La rivolta dei santi maledetti”, che rileggeva dalle fondamenta la fenomenologia di quella drammatica sconfitta, fece un’operazione di vera rottura ideologica, spingendo la provocazione ben oltre gli steccati della polemica antiborghese, osando toccare il nervo sensibile del superficiale orgoglio nazionale allora egemone in Italia: della rovinosa rotta dell’ottobre 1917 (che il generale Cadorna e molti osservatori attribuirono a un insieme di renitenza e insubordinazione di masse di fanti che in realtà erano abbrutiti dall’inumana vita di trincea) egli fece il simbolo di una rivolta politica in piena regola. Una volta vista non dall’ottica degli alti comandi e dei “bravi cittadini”, ma da quella del fantaccino analfabeta, quella sconfitta, che era un tabù rimosso dall’ipocrita mentalità borghese, diventava un atto politico e la massa dei disfattisti assurgeva a sua volta al rango di soggetto politico. Dando vita, come ha scritto Mario Isnenghi, a qualcosa di inedito e di potenzialmente incendiario, cioè “una interpretazione rivoluzionaria della prima guerra mondiale, della storia delle masse e della psicologia collettiva dentro la guerra”. La critica feroce di Malaparte si indirizzava soprattutto verso la morale filistea del borghesismo, quel mondo ipocrita fatto di patriottismo bolso e da operetta, comitati di gentiluomini, patronesse inanellate, tutti gonfi di retorica, con le loro “marcie di umanitarismo e di decadentismo patriottico”, con la loro schizzinosa paura per il popolo vero e i suoi bisogni: questa marmaglia, diceva Malaparte, in fondo odiava i fanti veri, quelli che “non volevano più farsi ammazzare pel loro umanitarismo sportivo”. In questo ritratto di una classe dirigente degenere, obnubilata di retorica e falsi ideali, ognuno riconosce facilmente la classe dirigente degenere di oggi, che è la stessa, radical-chic e impudente, umanitaria per divertimento e per interesse, ieri con i comitati patriottici, oggi con le onlus dedite al business della tratta di carne umana: la morale è la stessa, e lo stesso è l’inganno. Soppesiamo bene quanta verità è contenuta nell’espressione malapartiana di “umanitarismo sportivo” delle oligarchie borghesi, e paragoniamo la casta al potere allora con quella di oggi.

La critica feroce di Malaparte si indirizzava soprattutto verso la morale filistea del borghesismo, quel mondo ipocrita fatto di patriottismo bolso e da operetta, comitati di gentiluomini, patronesse inanellate, tutti gonfi di retorica, con le loro “marcie di umanitarismo e di decadentismo patriottico”, con la loro schizzinosa paura per il popolo vero e i suoi bisogni: questa marmaglia, diceva Malaparte, in fondo odiava i fanti veri, quelli che “non volevano più farsi ammazzare pel loro umanitarismo sportivo”. In questo ritratto di una classe dirigente degenere, obnubilata di retorica e falsi ideali, ognuno riconosce facilmente la classe dirigente degenere di oggi, che è la stessa, radical-chic e impudente, umanitaria per divertimento e per interesse, ieri con i comitati patriottici, oggi con le onlus dedite al business della tratta di carne umana: la morale è la stessa, e lo stesso è l’inganno. Soppesiamo bene quanta verità è contenuta nell’espressione malapartiana di “umanitarismo sportivo” delle oligarchie borghesi, e paragoniamo la casta al potere allora con quella di oggi. Si trattava di difendere un patrimonio che era prezioso per davvero: l’identità del popolo, che non è parola, non è retorica né slogan, ma vita e sostanza di un soggetto antropologico portatore di valori operanti lungo un arco di tempo pressoché incalcolabile. La minaccia avvertita da Malaparte era la violenza assimilatrice del mondo moderno, con la sua universale capacità di appiattire e annullare le diversificazioni culturali. Nel 1922, in uno studio sul sindacalismo italiano rimasto allora famoso, Malaparte lanciava un avvertimento del quale soltanto oggi, dinanzi all’enormità dell’aggressione che stanno subendo non solo gli italiani, ma tutti gli europei, possiamo valutare le tremende implicazioni: “In casa nostra ci è consentito di far soltanto degli innesti, non delle seminagioni. La semenza straniera non può essere buttata sul nostro terreno: la pianta che ne nasce non si confà al nostro clima. Bisogna a un certo punto bruciarla e tagliarne le radici”. L’essersi piegati senza resistenza ai diktat ideologici del liberalcapitalismo d’importazione anglosassone, il non aver ascoltato profezie come questa di Malaparte – che da un secolo in qua si levarono un po’ dappertutto in Europa – sta costando ai popoli europei la finale uscita di scena dalla storia, annegati nella degenerazione morale e nell’azzeramento della politica volute dalle agenzie progressiste cosmopolite.

Si trattava di difendere un patrimonio che era prezioso per davvero: l’identità del popolo, che non è parola, non è retorica né slogan, ma vita e sostanza di un soggetto antropologico portatore di valori operanti lungo un arco di tempo pressoché incalcolabile. La minaccia avvertita da Malaparte era la violenza assimilatrice del mondo moderno, con la sua universale capacità di appiattire e annullare le diversificazioni culturali. Nel 1922, in uno studio sul sindacalismo italiano rimasto allora famoso, Malaparte lanciava un avvertimento del quale soltanto oggi, dinanzi all’enormità dell’aggressione che stanno subendo non solo gli italiani, ma tutti gli europei, possiamo valutare le tremende implicazioni: “In casa nostra ci è consentito di far soltanto degli innesti, non delle seminagioni. La semenza straniera non può essere buttata sul nostro terreno: la pianta che ne nasce non si confà al nostro clima. Bisogna a un certo punto bruciarla e tagliarne le radici”. L’essersi piegati senza resistenza ai diktat ideologici del liberalcapitalismo d’importazione anglosassone, il non aver ascoltato profezie come questa di Malaparte – che da un secolo in qua si levarono un po’ dappertutto in Europa – sta costando ai popoli europei la finale uscita di scena dalla storia, annegati nella degenerazione morale e nell’azzeramento della politica volute dalle agenzie progressiste cosmopolite.

La ville de Fiume, ou Rijeka en croate, avait bénéficié en 1719 d’un statut de port franc autonome accordé par décret par Charles VI d'Autriche puis par l'impératrice Marie-Thérèse. En 1848, Fiume avait été brièvement occupée par la Croatie avant de retrouver son indépendance en 1868. Ville par excellence internationale, Fiume était, en 1919, peuplée d’Italiens, de Croates, de Hongrois ou d’Allemands. L’italien restait la langue dominante et le dialecte local, le « fiumien », se rapprochait du vénitien, tandis que le dialecte des campagnes alentours correspondait plus à une variante du croate. Ce métissage conférait à la ville une identité très forte et Fiume pouvait presque être considérée comme un exemple en miniature du multiculturalisme qui avait marqué, et aussi miné, l’empire austro-hongrois.

La ville de Fiume, ou Rijeka en croate, avait bénéficié en 1719 d’un statut de port franc autonome accordé par décret par Charles VI d'Autriche puis par l'impératrice Marie-Thérèse. En 1848, Fiume avait été brièvement occupée par la Croatie avant de retrouver son indépendance en 1868. Ville par excellence internationale, Fiume était, en 1919, peuplée d’Italiens, de Croates, de Hongrois ou d’Allemands. L’italien restait la langue dominante et le dialecte local, le « fiumien », se rapprochait du vénitien, tandis que le dialecte des campagnes alentours correspondait plus à une variante du croate. Ce métissage conférait à la ville une identité très forte et Fiume pouvait presque être considérée comme un exemple en miniature du multiculturalisme qui avait marqué, et aussi miné, l’empire austro-hongrois.  Ludovico Toeplitz, cinéaste italien et polyglotte, était quant à lui chargé des relations extérieures de la régence du Carnaro et, à ce titre, il mit également tout en œuvre pour faire de la ligue de Fiume une véritable « antisociété des nations », selon le vœu même de Gabrielle D’Annunzio :

Ludovico Toeplitz, cinéaste italien et polyglotte, était quant à lui chargé des relations extérieures de la régence du Carnaro et, à ce titre, il mit également tout en œuvre pour faire de la ligue de Fiume une véritable « antisociété des nations », selon le vœu même de Gabrielle D’Annunzio :  L’épisode fiumain, anachroniquement moderne, semble à la fois suspendu hors du temps et en même temps installé au cœur, au point charnière, de l’histoire européenne. Les révolutionnaires de Fiume réussissent à instaurer le complet envahissement de l’existence par l’art, et dans le même temps la complète politisation de l’art. Le geste de révolte devient manifestation artistique et la révolution, la guerre, le combat une manifestation esthétique : l’allégorie ultime du mouvement de la vie, de la mort et du chaos. Les futuristes, les dadas de combat et les poètes révolutionnaires monarchistes, anarchistes ou nationalistes que l’on pouvait rencontrer à Fiume ont eu des prédécesseurs en plein XIXe siècle dont ils reprennent les slogans, reproduisent les poses et rééditent en partie les engagements, à l’échelle d’une ville et d’une expérience un peu folle au cours de laquelle esthétique et action ne forment qu’un seul geste.

L’épisode fiumain, anachroniquement moderne, semble à la fois suspendu hors du temps et en même temps installé au cœur, au point charnière, de l’histoire européenne. Les révolutionnaires de Fiume réussissent à instaurer le complet envahissement de l’existence par l’art, et dans le même temps la complète politisation de l’art. Le geste de révolte devient manifestation artistique et la révolution, la guerre, le combat une manifestation esthétique : l’allégorie ultime du mouvement de la vie, de la mort et du chaos. Les futuristes, les dadas de combat et les poètes révolutionnaires monarchistes, anarchistes ou nationalistes que l’on pouvait rencontrer à Fiume ont eu des prédécesseurs en plein XIXe siècle dont ils reprennent les slogans, reproduisent les poses et rééditent en partie les engagements, à l’échelle d’une ville et d’une expérience un peu folle au cours de laquelle esthétique et action ne forment qu’un seul geste. Le « Noël sanglant » du 24 décembre 1920 mit fin à l’aventure de Fiume et à la tentative de révolution ésotérique et an-historique de D’Annunzio, contraint d’évacuer la ville après une semaine de rudes combats contre l’armée italienne. Le Vate terminera sa vie presque assigné à résidence dans sa demeure du lac de Garde, devenu invalide après être mystérieusement « tombé » de sa fenêtre dans la nuit du 13 au 14 août 1922.

Le « Noël sanglant » du 24 décembre 1920 mit fin à l’aventure de Fiume et à la tentative de révolution ésotérique et an-historique de D’Annunzio, contraint d’évacuer la ville après une semaine de rudes combats contre l’armée italienne. Le Vate terminera sa vie presque assigné à résidence dans sa demeure du lac de Garde, devenu invalide après être mystérieusement « tombé » de sa fenêtre dans la nuit du 13 au 14 août 1922.