[1]

[1]

Paru dans http://livr-arbitres.over-blog.com/ [2]

Vous êtes le président-fondateur des Etudes Rebatiennes, pouvez-vous les présentez brièvement à nos lecteurs ? Comment sont-elles nées ? Quels sont les objectifs, à court et plus long terme de votre association ?

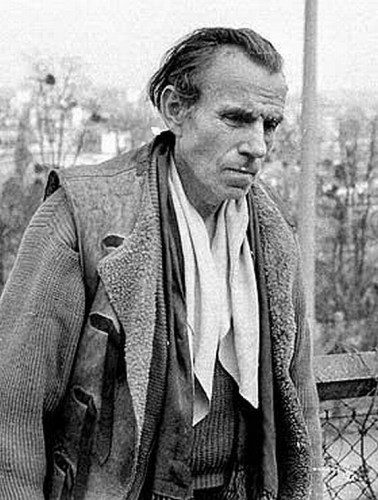

Les Etudes rebatiennes sont nées fin 2008, quelques mois seulement après la lecture des Deux Etendards ; elles ont été crées avec un autre professeur de lettres, Nicolas Degroote, captivés également par cette découverte. L’éblouissement qu’ont été pour moi Les Deux Etendards est tout de suite allé de paire avec l’étonnement devant cette lacune évidente de l’histoire littéraire. Cinq livres seulement ont été écrits sur Rebatet. Un silence assourdissant entoure donc ce chef d’œuvre. Prenant acte de mon émerveillement, je décide de fonder une association afin de contribuer au rayonnement de l’œuvre littéraire de Lucien Rebatet.

Le travail risque d’être long et difficile. Les mécompréhensions ont d’ores et déjà commencées puisque je reçois aussi bien des lettres d’insultes que, pire, des lettres d’admiration pour de mauvaises raisons… Heureusement certaines sont d’authentiques amoureux de littérature : ceux-là même à qui nous nous adressons. Mais la rigueur et le discernement finiront par l’emporter !

Nous aurons accompli notre tâche lorsque Les Deux Etendards seront publiés à la fois en poche et en Pléiade. A moins long terme, nous souhaitons faire paraître un Dossier H sur Rebatet. A très court terme – et c’est ce à quoi nous nous attachons surtout aujourd’hui – nous cherchons à élargir la liste des écrivains, historiens, critiques littéraires, etc. susceptibles d’écrire sur Rebatet ; ce qui ne va pas sans difficulté tant l’œuvre est méconnue.

Pourquoi ne pas vous être appelé « Les amis de Lucien Rebatet » ?

Je vous répondrais d’abord que je me fais une assez haute idée de l’amitié. Rebatet étant mort deux ans avant que je ne naisse, la question ne se pose pas. Mais admettons, pour les besoins de la conversation, qu’on fasse abstraction de la chronologie, qu’en aurait-il été ? Des paroles de Jean Dutourd répondent à cette question lorsqu’il avertit : « Si j’avais rencontré Lucien Rebatet en 1943, je lui aurais tiré dessus à coup de revolver » et, quelques lignes plus loin, ajoute : « Il avait écrit dans sa cellule de condamné un des plus beaux romans du XXème siècle : Les Deux Etendards que j’admirais avec fanatisme »[1]. Mutatis mutandis (car il est aisé de se prendre pour Jean Moulin avec 60 ans de retard), les Etudes rebatiennes s’alignent sur cette position. Autrement dit, chez Lucien Rebatet coexistent « une barbarie explicite et la création d’une œuvre d’art classique, imaginative et ordonnée [...] un des chefs d’œuvre secrets de la littérature moderne »[2]. Il est pour le moins difficile de lier amitié avec Lucien Rebatet dont la plume dénonça et provoqua l’arrestation de résistants.

Je précise aussi qu’en répondant à vos questions, je ne vous présente qu’une lecture de Rebatet, même si cette lecture se veut documentée et argumentée. Le conflit des interprétations, qui fait la vie de la critique, n’a pas encore véritablement commencé. Les Etudes voudraient en être le terrain privilégié.

Sur la dénomination, précisons encore que l’emploi du terme « études » indique le registre universitaire des participants. (Et, pour tout dire, « rebatiennes » plutôt que « rebatetiennes » car, par delà la laideur de l’expression, le « t » final du nom étant muet, l’élision était possible).

Les Etudes rebatiennes se structurent de la manière suivante : 1) Inédits 2) Entretiens et témoignages 3) Articles (critique littéraire) ; actualité rebatienne ; vie de l’association. Toutes les contributions sont les bienvenues à condition qu’elles soient œuvres de qualité. Le premier numéro devrait sortir dans un an. J’appelle les collaborateurs et souscripteurs (on peut être l’un et l’autre). En adhérant à l’association, vous souscrivez au n°1 des Etudes rebatiennes tout en contribuant à leur publication. Pour nous faire connaître un site a d’ores et déjà été créé (http://www.etudesrebatiennes.overblog.com [3]). Il livre de passionnants témoignages, une bibliographie, des critiques, etc.

Vous évoquez des inédits. De quoi s’agit-il ? Sont-ils importants ? Que pensez-vous publier ?

Cela ne peut se faire sans l’accord de l’ayant droit, Nicolas d’Estienne d’Orves, avec qui nous entretenons de très cordiales relations. Nous faisons partie de la même génération et la littérature nous importe davantage que la liste noire du CNE [Comité National des Ecrivains chargé de l'épuration dans le monde de la presse et de l'édition NDLR]. Que publier ? Au regard de la production contemporaine, je me dis souvent que toute l’œuvre littéraire mériterait de l’être ! Mais on ne peut le faire n’importe où et les éditeurs semblent encore ignorer sa grandeur.

Pour vous donner une idée de l’importance des inédits, faisons un détour par Gide qui écrivit, selon Genette, « le seul » journal de bord» entièrement et exclusivement consacré à la genèse d’une œuvre »[3] : le Journal des Faux-monnayeurs. Gide décrivait ainsi son projet : « au lieu de me contenter de résoudre, à mesure qu’elle se propose, chaque difficulté [...], chacune de ces difficultés, je l’expose, je l’étudie. Si vous voulez, ce carnet contient la critique continue de mon roman ; ou mieux : du roman en général. Songez à l’intérêt qu’aurait pour nous un semblable carnet tenu par Dickens, ou Balzac ; si nous avions le journal de L’Education Sentimentale, ou des Frères Karamazov ! L’histoire de l’œuvre, de sa gestation ! mais ce serait passionnant… plus intéressant que l’œuvre elle-même »[4]. Eh bien, il existe un autre journal de ce type et il est fascinant ! C’est l’Etude sur la composition. Au travers de trois cents pages, nous pénétrons dans l’atelier invisible de l’écrivain : non pas seulement ses brouillons mais mieux : l’atelier lui-même avec tous ses outils. Rebatet y expose ses conceptions littéraires au travers des difficultés rencontrées au cours des différents stades de la création. La simple existence de l’Etude sur la composition en fait, en soi, un aérolite de l’histoire de la littérature.

Par ailleurs, la masse de documents inédits est considérable. On y trouve un journal fleuve et rien moins que deux romans ! Margot l’enragée et La Lutte Finale. C’est un chantier immense. Existe également toute la masse non pas inédite mais dispersée des plusieurs milliers d’articles de critique littéraire, cinématographique, musicale… dont on attend une sélection prochainement. Déjà dans Les Deux Etendards on trouve grâce aux réflexions des personnages, « intoxiqués de littérature »[5], des pages de critiques acerbes et sagaces « qui valent bien un manuel entier et qui confirment les qualités de critique de Rebatet »[6].

Le postulat qui sous-tend votre démarche signifie-t-il qu’il est possible de faire une césure absolue entre le Rebatet écrivain et le Rebatet politique comme certains en font une entre le Céline du Voyage et celui des pamphlets ?

Il ne s’agit pas de faire une « césure » – et encore moins « absolue » – entre l’écrivain et le politique puisque chez Rebatet l’écrivain n’est jamais tout à fait apolitique et le politique souvent écrivain. Ce qu’il s’agit de dissocier méthodologiquement, c’est l’engagement politique d’un homme d’avec la qualité d’une œuvre littéraire. Comment faire ce partage ? En faisant de la critique littéraire !

Faisons brièvement un peu de philosophie de la littérature. Un écrivain écrit un texte 1) avec une intention 2) dans une situation 3) pour un public. Or, le texte lui-même exige que soit fait abstraction de ces trois déterminations : c’est l’autonomie du texte. Citons Ricœur : « Autonomie triple : à l’égard de l’intention de l’auteur ; à l’égard de la situation culturelle et de tous les conditionnements sociologiques de la production du texte ; à l’égard enfin du destinataire primitif. Ce que signifie le texte ne coïncide plus avec ce que l’auteur voulait dire ; signification verbale et signification mentale ont des destins différents. Cette première modalité d’autonomie implique déjà la possibilité que la » chose du texte» échappe à l’horizon intentionnel borné de son auteur, et que le monde du texte fasse éclater le monde de son auteur. Mais ce qui est vrai des conditions psychologiques l’est aussi des conditions sociologiques ; et tel qui est prêt à liquider l’auteur est moins prêt à faire la même opération dans l’ordre sociologique ; le propre de l’œuvre d’art, de l’œuvre littéraire, de l’œuvre tout court, est pourtant de transcender ses propres conditions psychosociologiques de production et de s’ouvrir ainsi à une série illimitée de lectures, elles-mêmes situées dans des contextes socioculturels toujours différents ; bref, il appartient à l’œuvre de se décontextualiser, tant au point de vue sociologique que psychologique, et de pouvoir se recontextualiser autrement ; ce que fait l’acte de lecture. [...] avec l’écriture, le destinataire originel est transcendé. Par delà celui-ci, l’œuvre se crée elle-même une audience, virtuellement étendue à quiconque sait lire »[7]. En fait, les Etudes rebatiennes font simplement leur, la célèbre formule de Proust : « un livre est le produit d’un autre moi que celui que nous manifestons dans nos habitudes, dans la société, dans nos vices »[8].

Pour bien aborder Les Deux Etendards, il faudrait donc oublier le collaborateur ? Cela signifie-t-il que Les Deux Etendards soit une œuvre apolitique ?

Entendons-nous bien. Avec la proclamation de l’autonomie des Deux Etendards en tant qu’œuvre d’art, je n’entends pas réhabiliter en sous-main la haine rebatienne. Il s’agit donc, non pas de cacher l’homme par l’œuvre – ni a fortioriL’Emile malgré l’abandon de ses enfants par Jean-Jacques. de cacher l’œuvre par l’homme – mais d’étudier l’œuvre qui se soutient d’elle-même. L’étude littéraire doit pouvoir s’élaborer en mettant méthodologiquement la biographie de l’auteur entre parenthèses comme il faut étudier la philosophie rousseauiste de l’éducation de

On a pu écrire qu’« il n’est pas question de politique dans Les Deux Etendards »[9]. A l’inverse, certains ont affirmé : « Si Les décombres a été la chronique de la mort annoncée des Juifs, Les Deux Etendards instruit le procès du dieu chrétien et de l’homme qui se voient également condamné à mort, au nom de la lutte contre les valeurs judéo-chrétiennes et la démocratie. Dans cet ouvrage, Rebatet prône l’avènement d’une morale substitutive, le paganisme vitaliste, un sacré abâtardi dont les fascismes se sont également inspirés, pour tenter de liquider des références judéo-chrétiennes de la civilisation occidentale. Le mode d’expression a changé, mais le message demeure »[10]. C’est aller de Charybde en Scylla.

Les Deux Etendards ne sont pas une « parabole fasciste » : ils ne constituent pas la contrepartie romanesque d’une quelconque « fidélité au national-socialisme ». Car ils ne sont pas une œuvre politique mais, primordialement, une œuvre d’art. Cela signifie-t-il que la politique en soit absente ? Non ; elle y tient bien une place puisqu’on peut y déceler une présence d’antidémocratisme, d’antisémitisme, de racisme, de mépris du peuple, d’anticommuniste, d’antibourgeoisisme… mais cela ne fait pas partie des thèmes centraux du roman.

De surcroît, il convient de rappeler qu’« il n’est de toute façon pas question de condamner l’ouvrage pour les idées de ses acteurs, quand bien même celles-ci occuperaient une place beaucoup plus importante, puisque la valeur d’une œuvre n’est certainement pas proportionnelle à la qualité morale de ses protagonistes. De même qu’un roman qui a pour personnage central un meurtrier ne préconise pas nécessairement le meurtre, celui de Rebatet, dont certains acteurs et même le narrateur penchent clairement vers l’extrême-droite, ne fait pas nécessairement l’apologie de leurs idées »[11]. Bref, n’ensevelissons pas Les Deux Etendards sous Les Décombres !

S’il y a une continuité à établir entre les deux ouvrages, c’est surtout dans la stylistique qu’on la trouvera. En laissant de coté les catégories impropres de forme et de fond, se présentent bien un style pour deux thèmes (et non deux styles pour un thème). « Si la passion change d’objet des Décombres aux Deux Etendards, elle ne change pas de ton : c’est la même véhémence, la même jubilation jusque dans la grossièreté, la même volonté de se servir de tous les moyens, la même rage de convaincre, la même violence exaspérée »[12]. D’un livre à l’autre, Rebatet suivait son plan : d’abord « témoigner, militer par un livre, puis en entreprendre aussitôt après un autre, qui serait enfin une œuvre d’imagination. [...]. J’avais maintenant un adversaire d’une tout autre taille avec qui polémiquer : Dieu »[13]. A son habitude, Rebatet bourre son ouvrage d’explosifs en tous genres, et « le fracas de cette explosion remplit le livre, comme le déchirement du patriotisme remplissait Les Décombres. D’ailleurs, le génie est le même : la même puissance lyrique, même déferlement de l’image et du verbe, même amertume. Mais ce qui distingue Rebatet parmi d’autres polémistes, parmi Bloy, Péguy, Daudet, Bernanos, c’est la volonté de convaincre. Pour lui, tous les arguments sont bons. » Quand on se bat, dit son héros, on ne songe pas à se demander si les armes ont déjà servi» . Tantôt il trace une satire extraordinaire des jésuites, tantôt il se lance dans d’interminables analyses de textes, tantôt il descend aux critiques les plus vulgaires, mais aussi les plus frappantes. Nos seules épopées sont des œuvres individuelles et des œuvres de protestation : ce sont Les Châtiments, Les Tragiques. Voici l’épopée de l’athéisme »[14].

Mais de quoi parle au juste Les Deux Etendards ?

D’amour ! Il n’y a pas moins original mais pas plus essentiel. Le thème des Deux Etendards se trouve magnifiquement énoncé dans le roman lui-même lorsque Michel reçoit sa vocation de romancier : « L’amour, feu central, avait embrasé cette matière inerte du passé, du présent, de l’avenir, du réel, de l’imaginé, que Michel portait au fond de lui ; l’amour l’avait fondue, et grâce à lui seul elle prendrait forme. L’amour serait célébré dans tous ses délices et toutes ses infortunes. Mais le livre dirait aussi la quête de Dieu, les affres de l’artiste. La poésie, les secrets des vices, les monstres de la bêtise, la haine, la miséricorde, les bourgeois, les crépuscules, la rosée des matins de Pâques, les fleurs, les encens, les venins, toute l’horreur et tout l’amour de la vie seraient broyés ensemble dans la cuve »[15].

Comment Rebatet/Michel s’y prendra-t-il pour réussir une telle gageure ? Il va « refaire du Proust sur nature » comme Cézanne refit du Poussin sur nature. Qu’est-ce à dire ? Pour le dire brutalement, Rebatet a transposé « certaines méthodes de l’analyse proustienne à une histoire, à des sentiments plus consistants que les sentiments, les histoires du monde proustien (on peut tout de même prétendre qu’une grand expérience religieuse, par exemple, est humainement plus importante que les snobismes et contre-snobismes d’un grand salon) »[16]. Ainsi, « les modernes s’étaient forgés des instruments d’une perfection, d’une souplesse, d’une nouveauté admirables. Mais ils ne les employaient guère qu’à disséquer des rogatons, à décrire des snobismes, des démangeaisons du sexe, des nostalgies animales, des affaires d’argent, des anatomies de banquiers ou de perruches mondaines. Michel connaissait leur scalpels, leurs microscopes, leurs introspections, leurs analyses, mais il s’évaderait des laboratoires. Le premier, il appliquerait cette science aux plus grandioses objets, à l’eternel conflit du Mal et du Bien, trop vaste pour ne point déborder les petits encéphales des physiologistes »[17]. Par delà la caricature proustienne, retenons la mobilisation d’un art d’écrire contre la foi, une croisade antireligieuse.

D’un point de vue narratif, le roman « raconte la maturation, l’amitié profonde, puis la séparation de deux jeunes gens dans la France de l’entre-deux-guerres. Ils sont épris de la même jeune femme, qui, par sa plénitude de vie, son rayonnement physique et psychologique, est une créature comparable à la Natacha de Tolstoï. L’articulation de cette relation à trois et de la grande fugue de l’accomplissement érotique sur laquelle s’achève le roman sont de grands actes de l’imagination. [...] le roman de Rebatet a l’autorité impersonnelle, la beauté formelle pure de l’art classique »[18]. En effet, le roman se présente d’abord comme un Bildungsroman (éducation sentimentale) dans la lignée de la trilogie balzacienne ou du Rouge et Noir. Deux amis Régis, l’amant mystique, et Michel, l’amoureux éperdu, engagent une guerre fratricide dont Anne-Marie sera la victime principale. Il serait très éclairant que quelqu’un entreprenne un jour une lecture girardienne des Deux Etendards. La médiation interne qu’est Régis pour Michel, de modèle se mue en obstacle. La rivalité mimétique s’exacerbe au détriment de ce que furent tour à tour les objets du désir : Dieu et Anne-Marie. Le mensonge romantique est-il dénoncé et la vérité romanesque dévoilée dans le roman ? Quoi qu’il en soit, nous avons là une des plus grandes analyses de la passion amoureuse.

« Balzac avait besoin d’un trône et d’un goupillon ; Zola, du transformisme et de la médecine : il faut à Rebatet l’athéisme et l’anarchie. Fort de ces principes, il accorde à chacun son dû : aussi bavard que celui de Thomas Mann, son jésuite me parait plus riche, plus nuancé : plus attachant ; aussi pieuse que lesbienne, aussi lesbienne qu’intelligente, aussi intelligente qu’espiègle, aussi espiègle que baiseuse, ah ! la charmante enfant, Anne-Marie, la maîtresse rêvée ! Quant à Michel ! C’est Rebatet, disent les gens qui savent. Erreur. Michel, c’est vous, c’est moi. Michel, c’est notre jeunesse. – C’est aussi Lucien Rebatet ! – C’est surtout Lucien Leuwen »[19]. Mais l’épilogue est tragique. Anne-Marie, brûlée vive entre un amour désincarné et un amour despiritualisé, entre l’éther et l’orgie, écrira une inoubliable lettre de rupture « toute imprégnée du contrepoint de la solitude, si inflexiblement résignée à la définitive destruction, et qui évoque le destin frustré du véritable amour au point que les deux étendards confondent leurs coutures afin de mieux former un suaire »[20]. Rebatet concluait : « Trois mystiques vagabonds se sont heurtés au catholicisme. Le prêtre s’est soumis, » obéissant très vulgairement à sa fonction éternelle, et s’asseyant sereinement dans les duperies de son rôle» . Anne-Marie » est retournée naturellement aux orgies des rites primitifs» . Michel » a vu que s’il n’y a aucun chemin entre Dieu et les hommes, c’est peut-être et d’abord parce que les religions les bouchent tous »[21].

Rebatet parvient-il à ses fins avec son « épopée de l’athéisme » ? Triomphe-t-il de toute croyance ?

Rebatet s’emporte facilement sur le sujet sans plus faire aucune distinction : « Je hais les religions à mort. Je vois quelquefois, les égyptiennes, les babyloniennes, les tibétaines, les aztèques, l’Islam, le catholicisme médiéval, le puritanisme yankee, comme des spectres grotesques et dégoulinants de sang. Ce sont les plus atroces fléaux de l’humanité »[22]. Toutefois, on trouve de temps à autre sous sa plume une sensibilité plus amène : « il est assez difficile de se trouver l’avant vielle ou la vieille de Pâques sans se rappeler que le Christ est le grand patron de tous les condamnés à mort. Je l’avoue, je n’écouterais pas très volontiers ce soir les stoïques et autres philosophes qui ont moqué les angoisses du jardin des oliviers »[23].

La question de Dieu n’est pas si simple et pauvre pour qu’on puisse la laisser à l’opinion de chacun. Par exemple, il n’est pas du tout certain que l’athéisme soit l’ennemi de la foi. Si l’athéisme combat la piété vouée aux dieux mythiques des religions archaïques et sacrificielles, alors l’athéisme peut être enrôlé dans la lutte contre l’idolâtrie. En ce sens Levinas écrivait : « Le monothéisme marque une rupture avec une certaine conception du sacré. Il n’unifie ni ne hiérarchise ces dieux numineux et nombreux ; il les nie. A l’égard du divin qu’ils incarnent, il n’est qu’athéisme. [...]. Le monothéisme dépasse et englobe l’athéisme, mais il est impossible à qui n’a pas atteint l’âge du doute, de la solitude, de la révolte »[24].

Mais tournons-nous plutôt vers le roman. Je ne crois pas que Les Deux Etendards soient une apologétique athée, non plus qu’une épopée. Michel y fait bien une tentative de conversion qui tourne en « déconversion »[25]. Mais celle-ci n’est pas une inversion pure et simple, elle n’est pas du « Michel-Ange inversé »[26] puisque Michel se défend d’être athée[27]. D’ailleurs, n’était l’homophonie avec Le Diable et le Bon Dieu, le roman se fut appelé Ni Dieu ni Diable. L’agnostique Michel ne s’épuise pas plus à toujours nier, qu’il ne cherche en gémissant. L’aporie de la confrontation finale ferait-elle alors signe vers un néo-paganisme ? Plus précisément : vers la désolation que laisserait l’impossibilité d’un retour du sacré[28] ? Michel ne se ferait-il pas parfois une plus juste idée du Christianisme qu’il ne le laisse paraître, idée au nom de laquelle il déboulonne les idoles ? Ces questions restent ouvertes.

Toutefois, avec ces problèmes théologiques, il ne faudrait pas laisser penser qu’on aurait affaire à un roman, à thèse et encore moins un manuel d’athéologie. Blondin notait bien : « On a qu’un voyage pour sa nuit. Celle de Lucien Rebatet est somptueusement agitée. Elle ravit aux professeurs travestis, et avec quel éclat, le monopole de l’inquiétude métaphysique et [...] rend le Diable et le Bon Dieu à une vie quotidienne passionnante, passionnée. [...]. Il va chercher Dieu sur son terrain qui est celui de la crainte, de l’espérance, du tremblement, de la passion titubante. Sous cette forme romanesque, le problème de la religion recouvre ses plus chauds prestiges »[29]. Un grand roman, « non de la démonstration d’une thèse : des êtres s’affrontent, non des allégories. Il reste que Les Deux Etendards constituent un arsenal d’armes de tous calibres contre le christianisme. Il y a des armes les plus savantes : critiques des textes sacrés, interpolations, interprétations douteuses, dogmes tirés de textes peu sûrs ou trop sollicités, etc. Il arrive que Régis perde pied devant des coups inattendus. Nous avons des exégètes qui répondent très bien, dit-il, quand il se reprend. Réponse trop facile, peut-être, mais moins faible qu’on ne pourrait le croire. On ne peut passer sa vie dans la controverse, et pour Régis, la foi ne dépend pas de tel ou tel point de dogme. Elle est au-delà des constructions intellectuelles auxquelles elle impose d’adhérer. La discussion entre les deux garçons ne peut jamais avancer. Michel ne néglige pas, à coté de cela, des armes plus vulgaires, instinctives, grosses plaisanteries. Ce roman compte une étonnante galerie de prêtres tous obtus, libidineux, hypocrites. Avec tout cela, cette partie polémique date : le moralisme étroit, inhumain, qui encolère Michel n’est plus aujourd’hui le défaut d’une Eglise qui s’est beaucoup débridée [Rebatet en viendra même dans son Journal à se considérer ironiquement comme le dernier catholique !] Si l’on se passionne pour cette controverse, c’est parce que l’on se passionne pour les trois héros »[30]. Sur cette lancée, ira-t-on jusqu’à affirmer que Les Deux Etendards « pourrait ainsi passer à force de vie et de vérité, gonflant des héros en tous points admirables, pour une apologie du spiritualisme »[31] ? Le dernier mot du roman est laissé au jésuite. Il est même probable qu’il ait raison quand il affirme que lui, au moins, laissera un souvenir lumineux à Anne-Marie, jeune fille fichue, laissée à une tristesse infinie. Bien évidemment, c’est une victoire à la Pyrrhus : il vaut mieux avoir tort avec Michel que raison avec Régis. Car depuis bien longtemps nous avons quitté le débat théologique pour rejoindre le tragique de l’existence.

A moins que le débat théologique ne se pose justement sur le terrain de l’existence. Et c’est peut-être là l’intérêt fondamental de l’œuvre de Rebatet. En effet, il n’est pas du tout évident, malgré une longue tradition, que la question de Dieu doive se poser par le biais de savoir s’il est ou pas. Il se pourrait même que ce soit une fort mauvaise question. Levinas exprime bien la descente de la question du ciel sur la terre quand il proposa d’« interdire à la relation métaphysique avec Dieu de s’accomplir dans l’ignorance des hommes et des choses. La dimension du divin s’ouvre à partir du visage humain. [...] la métaphysique se joue là où se joue la relation sociale. Il ne peut y avoir, séparée de la relation avec les hommes, aucune » connaissance» de Dieu. Autrui est le lieu même de la vérité métaphysique et indispensable à mon rapport à Dieu »[32]. Disons le autrement et radicalement avec Maître Eckhart : « Si quelqu’un était dans un ravissement comme saint Paul [!] et savait qu’un malade attend et qu’il lui porte un peu de soupe, je tiendrais pour bien préférable que, par amour, tu sortes de ton ravissement et serves le nécessaire dans le plus grand amour »[33].

Le lecteur se fait une idée du dieu de Régis à partir de son comportement. Or, la narration met au grand jour les ressorts cachés des faits et gestes de Régis : une sensualité mal camouflée, une jalousie drapée dans le désintéressement, une « attitude inhumaine, follement orgueilleuse, de condamner tout l’amour et de ne l’autoriser qu’à [lui] seul »[34]… Surtout, il décèle la sombre haine jusque dans l’amour lumineux : ce que Nietzsche, lecture de chevet de Rebatet, appelait « la fine fleur du ressentiment » : « cet amour est sorti de la haine, il en est la couronne, couronne du triomphe qui grandit dans la pure clarté d’une plénitude solaire et qui, dans le royaume de la lumière et des hauteurs, poursuit les mêmes buts que cette haine : la victoire, le butin, la séduction, du même élan que portait cette haine avide et opiniâtre à pousser ses racines de plus en plus loin dans tout ce qu’il y avait de ténébreux et de méchant »[35]. Rebatet disposait de cet « œil exercé » dont parle Scheler quand il affirme à propos de l’amour qu’« il n’est pas de notion que le ressentiment puisse mieux utiliser à ses propres fins, en lui substituant une autre émotion, grâce à un effet d’illusion si parfait que l’œil le plus exercé ne parvient plus à discerner du véritable amour un ressentiment où l’amour ne serait plus qu’un moyen d’expression »[36].

L’antichristianisme virulent ne s’exprime pas tant dans les arguments, bons ou mauvais, opposés à Régis que dans la simple description de la vie du futur jésuite. Les Deux Etendards ont l’immense mérite de mettre en scène, non pas seulement la foi et l’incroyance mais, plus fondamentalement, comme le dit avec raison Rebatet lui-même : le « conflit entre l’amour et Dieu. Un grand thème je crois. Il me semble qu’il n’y en a pas de plus grand : l’homme devant l’amour, l’homme devant Dieu »[37]. Puisque l’amour seul est digne de foi, Les Deux Etendards s’en prennent au cœur du christianisme. « Qu’as-tu fais de ton amour ? ». Telle pourrait être la question centrale du roman. La force de Rebatet c’est de retourner l’amour contre ceux qui s’en réclament. Mais si l’arme est l’amour, quelle portée peut-elle bien avoir devant un Dieu qui se définit par l’amour (I Jean 4,  ?

?

Pourriez-vous nous dire un mot du style des Deux Etendards ?

Disons-le d’emblée, Rebatet ne fut pas un créateur de style comme Proust ou Céline. Les Deux Etendardsème. Rebatet se plaçait résolument dans la catégorie des écrivains qui clarifient une matière compliquée sans recherche de l’innovation technique pour elle-même. Il écrivait : « J’aurais aimé que l’ont pût me faire l’honneur de quelques procédés nouveaux de narration. Je m’y sentais peu porté par nature, à moins que ce ne fût le métier qui me manquait. Mon roman n’était pas une forme singulière, imprévue, conçue a priori, et que je voulais remplir avec un thème et des personnages plus ou moins adéquats. C’était une histoire touffue, que je voulais raconter aussi complètement et clairement que possible. Je m’affirmais – un peu pour calmer mes regrets de ne pas suivre l’exemple de Joyce – que cette histoire était suffisamment complexe pour que je ne m’ingéniasse pas à la rendre indéchiffrable par des complications de forme. Mon esthétique, au cinéma, en littérature, comme en peinture et en musique, a d’ailleurs toujours été hostile aux procédés qui ne sont pas commandés par une nécessité intérieure »[38]. appartiennent plutôt à la lignée des grands romans classiques du XIX

Il y a pourtant bien une originalité stylistique du roman : elle réside dans la concomitance du sublime et de la fange. « Dans son projet d’ensemble, le roman est un pur produit du classicisme NRF et il n’est littérairement pas surprenant que Gallimard en ait été l’éditeur. Quand elle le veut bien, la langue n’y déroge jamais et nombreux y sont les passages où s’entend en quelque sorte la voix de Gide, dans l’économie des moyens et la pureté néoclassique du style. [...] Mais à l’intérieur même de cette épure stylistique, de ce dessin d’ensemble qui est comme le continuo du livre, l’écrivain loge tout autre chose : un véritable baroque célinien, l’usage de tous les registres de la langue à commencer par l’argot et, par-dessus tout peut-être, une crudité récurrente à la mesure de la présence d’Éros dans le récit. Car dans Les deux étendards, l’amour s’exprime sur tous les registres et si l’analyse du sentiment amoureux (selon une formule classique du roman français) n’est nullement étrangère à Rebatet, le lecteur retient surtout les nombreux passages érotiques qui sont ressentis comme autres sans que la perfection littéraire en soit moindre »[39].

Insistons-y : « L’originalité la plus vive de Rebatet, – la difficulté majeure, et vaincue de son entreprise, – c’a été de prêter un accent gothique aux débats de la plus haute psychologie et un accent de tendresse pudique à l’érotisme le plus orageux. Cela qui fit scandale, – comme toutes les nouveautés auxquelles on n’était pas préparé, – sera reconnu demain comme une des expériences magistrales (avec celle de Proust et de Céline) du vingtième siècle. [...] Aussi intelligent que La Montagne magique, aussi romanesque que Lucien Leuwen, aussi passionné que Les Possédés, Les Deux étendards, avec ses fougues et ses nonchalances, la déraison de ses mythes et la sagesse de sa bohème, sa fureur et sa grâce, ses sentiments stables et ses sentiments ambigus, ses caprices, ses détours et ses haines dans un Lyon aussi envoûtant que le Londres de Dickens, – Les Deux étendards ne cesseront pas de plaider la cause de Rebatet »[40].

Rebatet lui-même reprendra à son compte cette expression d’écrivain « gothique » : « Je dois dire que j’en ai été entièrement satisfait parce que j’aime beaucoup l’art gothique, un art fourre-tout où il y a des sommets lyriques, des bas-fonds, des rosaces éblouissantes, des images grotesques sculptées sur les portails, où il y a la théophanie et le péché originel. Et puis il y a aussi les peintres gothiques : Breughel et Jérôme Bosch »[41]. Grandeur et misère de l’homme ! Ainsi, Michel passe par « tous les stades, du platonisme mystique à l’obsession sexuelle »[42] car « littérairement, les termes les plus crus peuvent très bien alterner avec les plus délicats raffinements, comme dans les cathédrales, comme dans Shakespeare »[43]. C’est le génie de Rebatet, un des plus grands romanciers de la sensualité, que d’avoir su se tenir sur cette ligne de crête de laquelle on dérape si facilement soit dans la pornographie, soit dans le roman feuilleton.

Vous ne tarissez pas d’éloges sur le roman, mais comment pouvez-vous être certain qu’il soit un chef d’œuvre au regard du silence qui l’entoure ? Cela n’indiquerait-il pas plutôt que la non reconnaissance depuis 50 ans est méritée ? N’êtes vous pas fasciné par le mythe romantique de l’écrivain maudit ?

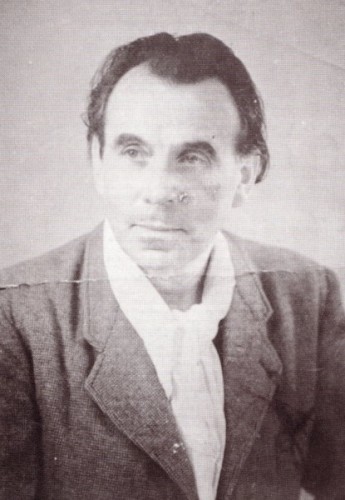

Voici comment Rebatet décrivait Pound : « Ezra Pound rejoint Villon, Rabelais pourchassé, demi-clandestin, Balzac dans sa turne, Stendhal ignoré dans son trou, Nerval le vagabond pendu, Dostoïevski le forçat, Baudelaire trainé en correctionnelle, Rimbaud le voyou, Verlaine le clochard, Nietzsche publié à compte d’auteur, Joyce sans feu ni lieu, Proust cloitré dans un garni, moribond, mais la plume à la main, Brasillach écrivant ses Bijoux les chaines aux pieds, Céline foudroyé à sa table dans son clapier du Bas-Meudon. Après tant d’exemples, comment douter que Pound est dans le bon camp, le vrai camp, le seul qui compte, celui qui enrichit les hommes, survit dans leur mémoire ? »[44]. Cette présentation de Pound en est une, à peine voilée, de Rebatet lui-même. Elle est romantique. Rebatet se prête facilement à cette mythologie quand on sait que Les Deux Etendards furent écrit par un condamné à mort dont les chaînes retentissaient dans une cellule où l’eau gelait nuit et jour.

Sans nous laisser obnubiler sur le soi-disant « seul camps qui compte », il faut bien reconnaître que Rebatet n’a pas la place qu’il mérite. Les Deux Etendards sont un chef d’œuvre car c’est un classique. Un classique de premier ordre même, puisque Les Deux Etendards sont à mes yeux la poursuite de l’œuvre nietzschéenne par d’autres moyens. Le niveau d’un tel affrontement entre l’homme et Dieu trouve son équivalent dans Les Frères Karamazov. Mais la question rejaillit : comment sait-on que c’est un classique me direz-vous ? Pour répondre plus amplement à votre question, il est nécessaire de refaire un peu de philosophie de la littérature.

Une œuvre littéraire – une œuvre d’art en général – transcende par définition ses propres conditions psychosociologiques de production. Elle s’ouvre ainsi à une suite illimitée de lectures. Celles-ci sont elles-mêmes situées dans des contextes socioculturels différents. Ainsi l’œuvre se décontextualise et se recontextualise. Si elle ne le faisait pas, si une œuvre n’était que le reflet de son époque, alors elle ne se laisserait pas recontextualiser et ne mériterait donc pas le statut d’œuvre d’art. La capacité d’échapper à son temps fait la contemporanéité de l’œuvre. Ecoutons Gadamer : « Entre l’œuvre et chacun de ses contemplateurs existe vraiment une contemporanéité absolue qui se maintient intacte malgré la montée de la conscience historique. On ne peut pas réduire la réalité de l’œuvre d’art et sa force d’expression à l’horizon historique primitif dans lequel le contemplateur de l’œuvre était réellement contemporain de son créateur. Ce qui semble au contraire caractériser l’expérience de l’art, c’est le fait que l’œuvre possède toujours son propre présent [...] l’œuvre d’art se communique elle-même »[45]. Ainsi, à la question « qu’est-ce qu’un livre classique ? », on peut répondre, avec Sainte-Beuve : une œuvre « contemporain[e] de tous les âges »[46]. Echappant au contexte qui l’a vu naître, sans prétendre illusoirement à l’intemporalité, le classique traverse les modes et les aléas de l’histoire. Or, aux questions soulevées par Rebatet est inhérent un surcroît de sens permanent.

Quant au peu de critiques et à l’ignorance du public cultivé, on a pu avancer plusieurs raisons plus ou moins légitimes : le prix du roman, sa longueur, sa complexité, le rejet de certains libraires, l’importance donnée à la question religieuse, etc. Mais « l’indiscutable vérité est que Les Deux Etendards continue à être ignoré aujourd’hui à cause du black-out qui le frappe et que ce black-out a été imposé pour des raisons politiques. [...]. L’on veut surtout espérer que notre époque est suffisamment mûre et suffisamment affranchie des passions déclenchées par les événements de la seconde guerre mondiale pour enfin considérer objectivement et du seule point de vue littéraire un roman aussi important que celui de Rebatet, et ce d’autant plus qu’elle est particulièrement pauvre en chefs-d’œuvre »[47].

Les deux étendards sont donc un roman à la fois classique et méconnu du fait de la conspiration du silence engendrée par les opinions politiques de l’auteur. Rappelons simplement qu’Etiemble s’est fait exclure des Temps Modernes par Sartre au prétexte de la reconnaissance du génie littéraire de Rebatet. En sommes-nous encore à ce point ? La situation est peut-être pire car la conspiration du silence a fonctionné et s’est depuis muée, le relativisme aidant, en indifférence. En plus d’amoureux de la littérature, il nous faut trouver des esprits libres !

Gilles de Beaupte, merci et longue vie à votre association !

Mais nous n’avons pas encore évoqué Les Epis Mûrs ou Une Histoire de la musique !

Site des Etudes rebatiennes : http://www.etudesrebatiennes.overblog.com [3]. Adhérez à l’association : 20 €/an chèques à l’ordre des Etudes rebatiennes à l’adresse suivante : Etudes rebatiennes, 12 rue de la Cossonnerie 75001 Paris. Pour tout renseignement etrudesrebatiennes@gmail.com [4]

[1] Jean Dutourd, « L’art et la morale », Matulu, Paris, n° 17, sept. 1972, p. 9.

[2] Georges Steiner, « Appel au meurtre », Extraterritorialité. Essais sur la littérature et la révolution du langage, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 2002, p. 70.

[3] Gérard Genette, Seuils, Paris, Paris, Seuil, p. 362.

[4] André Gide, Les Faux-monnayeurs, Paris, Gallimard, Pléiade, 1958, p. 1083.

[5] Lucien Rebatet, Les Deux Etendards, Paris, Gallimard, 1951, p. 361.

[6] Pascal A. Ifri, Les Deux Etendards de Rebatet, op. cit., p. 152.

[7] Paul Ricœur, « Herméneutique et critique des idéologies », Du texte à l’action. Essais d’herméneutique II, Paris, Seuil, 1986, p. 404-405.

[8] Marcel Proust, Contre Sainte-Beuve, Paris, Gallimard, 1954, p. 157.

[9] Laffont-Bompiani, Dictionnaire des œuvres, Paris, Laffont, 1986, p. 295.

[10] Robert Belot, « Lucien Rebatet », L’antisémitisme de plume 1940-1944, P.-A. Taguieff (dir.), Paris, Berg International, 1999, p. 225.

[11] Pascal A. Ifri, Les Deux Etendards de Lucien Rebatet. Dossier d’un chef d’œuvre maudit, Lausanne, L’âge d’homme, 2001, p. 81.

[12] Pol Vandromme, Rebatet, Paris, Editions Universiataires, 1968, p. 65.

[13] Lucien Rebatet, Mémoires d’un fasciste II, Paris, Pauvert, 1976, p. 113-114.

[14] Bernard de Fallois, « Le Chef d’œuvre de Rebatet », Opéra, 6 février 1952.

[15] Lucien Rebatet, Les Deux Etendards , op. cit., p. 181.

[16] Lucien Rebatet, Lettres de prison, Paris, Le Dilettante, 1992, p. 34.

[17] Lucien Rebatet, Les Deux Etendards, op. cit., p. 182.

[18] Georges Steiner, « Appel au meurtre », Extraterritorialité, op. cit., p. 70.

[19] René Etiemble, « A propos de Lucien Rebatet », (1953), Hygiène des Lettres II. La littérature dégagée 1942-1953, Paris, Gallimard, 1955, p. 210.

[20] Jacques Vier, « Il faut parler de Lucien Rebatet », Littérature à l’emporte-pièce VII, op. cit., p. 130.

[21] Lucien Rebatet, Etude sur la composition (inédit).

[22] Lucien Rebatet, Dialogue de « vaincus », Paris, Berg International Editeurs, 1999, p. 158.

[23] Lucien Rebatet, Lettres de prison, op. cit., p. 180.

[24] Emmanuel Levinas, « Une religion d’adulte », Difficile liberté, Paris, Livre de Poche, 1984, p. 29-31.

[25] Lucien Rebatet, Etude sur la composition, p. 63 (inédit).

[26] Jacques Vier, « Il faut parler de Lucien Rebatet », Littérature à l’emporte-pièce VII, Paris, Les éditions du Cèdre, 1974, p. 129.

[27] Lucien Rebatet, Les Deux Etendards, op. cit., p. 1086.

[28] Christophe Chesnot, « Les Deux Etendards de L. Rebatet, ou l’impossible exigence du sacré », Nouvelle Ecole, n° 46, Automne 1990, p. 11-31.

[29] Antoine Blondin, « Les Deux Etendards déchirent notre ciel », Ma vie entre les lignes, Paris, La Table Ronde, 1982, p. 103.

[30] Georges Laffly, « Lucien Rebatet », Ecrits de Paris, Paris, 1972, p. 99.

[31] Robert Poulet, Le caléidoscope, Lausanne, L’âge d’homme, 1982, p. 93.

[32] Emmanuel Levinas, Totalité et Infini, M. Nijoff, La Haye, 1968, p. 50-51.

[33] Maître Eckhart, Les traités, Paris, Seuil, 1971, p. 55.

[34] Lucien Rebatet, Les Deux Etendards, op. cit., p. 345.

[35] Friedrich Nietzsche, Généalogie de la morale, Œuvres Philosophiques Complètes VII, Paris, Gallimard, 1992, p. 232.

[36] Max Scheler, L’homme du ressentiment, Paris, Gallimard, 1970, p. 74.

[37] Lucien Rebatet, « » Derniers mots» . Entretien avec Michel Marmin », Matulu, Paris, n°17, sept 1972, p. 10.

[38] Lucien Rebatet, Les mémoires d’un fasciste II, op. cit., p. 110-111.

[39] Yves Reboul, « Lucien Rebatet : le roman inachevé ? », Études littéraires, vol. 36, n° 1, 2004, p. 25-26.

[40] Pol Vandromme, Rebatet, op. cit.

[41] Lucien Rebatet, « » Derniers mots» . Entretien avec Michel Marmin », Matulu, art. cit., p. 10.

[42] Lucien Rebatet, Lettres de prison, op. cit., p. 78.

[43] Lucien Rebatet, Dialogue de « vaincus », op. cit., p. 110.

[44] Lucien Rebatet, cité dans Pascal. Ifri, Rebatet, Paris, Pardès, 2004, p. 65.

[45] Hans-Georg Gadamer, « Esthétique et herméneutique », L’art de comprendre. Ecrits II. Herméneutique et champ de l’expérience humaine, Paris, Aubier, 1991, p. 139-140.

[46] Sainte-Beuve, Causeries du lundi, Paris, Garnier Frères, 1894, p. 598.

[47] Pascal A. Ifri, Les Deux Etendards de Lucien Rebatet, op. cit., p. 12-13.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Tiana BERGER:

Tiana BERGER: