mardi, 24 septembre 2013

Sur l’entourage et l’impact d’Arthur Moeller van den Bruck

Robert STEUCKERS:

Sur l’entourage et l’impact d’Arthur Moeller van den Bruck

Conférence prononcée à la tribune du “Cercle Proudhon”, à Genève, 12 février 2013

Pourquoi parler ou reparler de Moeller van den Bruck aujourd’hui, 90 ans après la parution de son livre au titre apparemment fatidique, “Le Troisième Reich” (= “Das Dritte Reich”)? D’abord parce que l’historiographie récente s’est penchée sur lui (cf. bibliographie) en Allemagne, d’une manière beaucoup plus systématique qu’auparavant. Il est l’apôtre raté d’un “Troisième Règne”, qui n’adviendra pas de son vivant mais dont le nom sera repris par le mouvement hitlérien, dans une acception bien différente et à son corps défendant. Il s’agit de savoir, aujourd’hui, ce que Moeller van den Bruck entendait vraiment par “Drittes Reich”. Il s’agit aussi de cerner ce qu’il entendait par sa notion de “peuples jeunes”. Comment il entrevoyait la coopération entre l’Allemagne et la Russie (devenue l’URSS) dans le cadre de la République de Weimar, dont il méprisait les principes et le personnel. Arthur Moeller van den Bruck a participé à la formulation d’un “nationalisme de rupture”, d’un “néo-nationalisme” qu’Armin Mohler, dans sa célèbre thèse, a classé dans le phénomène de la “révolution conservatrice”. Une chose est certaine: Arthur Moeller van den Bruck n’est ni un “libéral” (au sens où l’entendait la démocratie de la République de Weimar) ni un pro-occidental, dans la mesure où il entendait détacher l’Allemagne de l’Occident français, anglais et américain.

L’oeuvre politique d’Arthur Moeller van den Bruck est toutefois ténue. Il n’a pas été aussi prolixe qu’Oswald Spengler, dont le célèbre “Déclin de l’Occident” est fort dense, d’une épaisseur bien plus conséquente que “Das Dritte Reich”. De plus, la définition, finalement assez ambigüe, que donne Spengler de l’Occident ne correspond pas à celle que donnera plus tard Moeller van den Bruck. Sans doute la brièveté de l’oeuvre politique de Moeller van den Bruck tient-elle au simple fait qu’il est mort jeune et suicidé, à 49 ans. Son oeuvre littéraire et artistique en revanche est beaucoup plus vaste. Moeller van den Bruck, en effet, a écrit sur le théâtre de variétés, sur le théâtre français, sur l’esthétique italienne, sur la mystique allemande, sur les personnages-clefs de la culture germanique (ceux qui en font son essence), sur la littérature moderniste, allemande et européenne, de son temps. Son oeuvre politique, qui ne prend son envol qu’avec la Grande Guerre, se résume à un ouvrage sur le “style prussien” (avec un volet sur l’art néo-classique), à l’ouvrage intitulé “Troisième Reich”, au livre sur la “révolte des peuples jeunes”, à ses articles parus dans des revues comme “Gewissen”. Moeller van den Bruck a donc été un séismographe de son époque, celle d’un extraordinaire foisonnement d’idées, de styles, d’audaces.

Zeev Sternhell et la “droite révolutionnaire”, Armin Mohler et la “Konservative Revolution”

La question qu’il convient de poser est donc la suivante: d’où viennent ses idées? Quel a été son cheminement? Quelles rencontres, apparemment “apolitiques”, ont-elles contribué à forger, parfois à leur corps défendant, son “Jungkonservativismus”? Le fait d’être homme, dit-on, c’est mener une quête, sans jamais s’arrêter. Quelle a donc été la quête personnelle, unique et inaliénable de Moeller van den Bruck? Il convient aussi de resituer cette quête dans un cadre historique et social. Cette démarche interpelle l’historiographie contemporaine: Zeev Sternhell avait tracé la généalogie du fascisme français depuis 1870 environ, avant de se pencher sur les antécédents de l’Italie fasciste et du sionisme. Après la parution en France, au “Seuil” à Paris, du premier ouvrage “généalogique” de Sternhell, intitulé “La droite révolutionnaire”, Armin Mohler, auteur d’un célèbre ouvrage synoptique sur la “révolution conservatrice”, lui rendait hommage dans les colonnes de la revue “Criticon”, en disant que le cadre de sa propre enquête avait été fixé, par son promoteur Karl Jaspers, à la période 1918-1932, mais que l’effervescence intellectuelle de la République de Weimar avait des racines antérieures à 1914, plongeant finalement dans un bouillonnement culturel plus varié et plus intense, inégalé depuis en Europe, dont de multiples manifestations sont désormais oubliées, se sont estompées des mémoires collectives. Et qu’il fallait donc les ré-exhumer et les explorer. Exactement comme Sternhell avait exploré l’ascendance idéologique de l’Action Française et des autres mouvements nationaux des années 20 et 30.

Ascendance et jeunesse

Resituer un auteur dans son époque implique bien entendu de retracer sa biographie, de suivre pas à pas la maturation de son oeuvre. Arthur Moeller van den Bruck est né en 1876 à Solingen, dans une famille prussienne originaire de Thuringe. Dans cette famille, il y a eu des pasteurs, des officiers, des fonctionnaires, dont son père, inspecteur général pour la construction des bâtiments publics. Cette fonction paternelle induira, plus que probablement, l’intérêt récurrent de son fils Arthur pour l’architecture (l’architecture de la Ravenne ostrogothique, le style prussien et l’architecture de Peter Behrens et du “Deutscher Werkbund”, comme nous allons le voir). L’ascendance maternelle, la famille van den Bruck, est, comme le nom l’indique, hollandaise ou flamande, mais compte aussi des ancêtres espagnols. Le jeune Arthur est un adolescent difficile, en rupture avec le milieu scolaire. Il ne décroche pas son “Abitur”, équivalent allemand du “bac”, ce qui lui interdit l’accès à l’université. Il restera, en quelque sorte, un marginal. Il quitte sa famille et se marie, à 20 ans, avec Hedda Maase. Nous sommes en 1896, année où survienent deux événements importants pour l’idéologie allemande de l’époque, qui donnera ultérieurement un certain lustre à la future “révolution conservatrice”: la naissance du mouvement de jeunesse “Wandervogel” sous l’impulsion de Karl Fischer et la création des éditions Eugen Diederichs à Iéna. Le jeune couple s’installe à Berlin cette année-là et Moeller van den Bruck vit de l’héritage de son grand-père maternel.

Baudelaire, Barbey d’Aurevilly, Poe...

Les jeunes époux vont entamer leur quête spirituelle en traduisant de grands classiques des littératures française et anglaise. D’abord Baudelaire qui communiquera à coup sûr l’idée du primat de l’artiste et du poète sur le “philistin” et le “bourgeois”. Ensuite Hedda et Arthur traduisent les oeuvres de Barbey d’Aurevilly. Cet auteur aura un impact important dans le rejet par Moeller van den Bruck du libéralisme et du bourgeoisisme. Barbey d’Aurevilly communique une certaine foi à Arthur, qui ne la christianisera pas —mais ne l’édulcorera pas pour autant— vu l’engouement de l’époque toute entière pour Nietzsche. Cette foi anti-bourgeoise, anti-philistine, se cristallisera surtout plus tard, au contact de l’oeuvre de Dostoïevski et de la personnalité de Merejkovski. Barbey d’Aurevilly était issu d’une famille monarchiste. Jeune, par défi, il se proclame “républicain”. Il lit ensuite Jospeh de Maistre et redevient monarchiste. Il le restera. En 1846, il se mue en catholique intransigeant, partisan de l’ultramontanisme. Barbey d’Aurevilly est aussi une sorte de dandy, haïssant la modernité bourgeoise, cultivant un style qui se veut esthétisme et rupture: deux attitudes qui déteindront sur son traducteur allemand. Le couple Moeller/Maase traduit ensuite le “Germinal” de Zola et quelques oeuvres de Maupassant. C’est donc, très jeune, à Berlin, que Moeller van den Bruck connaît sa période française, où le filon de Maistre/Barbey d’Aurevilly est déterminant, beaucoup plus déterminant que l’idéologie républicaine, qui donne le ton sous la III° République.

Mais ses six années berlinoises sont aussi sa période anglaise. Avec son épouse, il traduit l’ensemble de l’oeuvre de Poe, puis Thomas de Quincey, Daniel Defoe et Dickens. La période “occidentale”, franco-anglaise, de Moeller van den Bruck, futur pourfendeur de l’esprit occidental, occupe donc une place importante dans son itinéraire, entre 20 et 26 ans.

Zum Schwarzen Ferkel

Moeller van den Bruck fréquente le local branché de la bohème littéraire berlinoise, “Zum Schwarzen Ferkel” (“Au Noir Porcelet”) puis le “Schmalzbacke”. Le “Schwarzer Ferkel” est le pointde rencontre d’intellectuels et de poètes allemands, scandinaves et polonais, faisceau de diversités européennes qui constitue un “unicum” dans l’histoire des idées. A côté des poètes, il y a aussi des médecins, des artistes, des juristes: les débats y sont pluridisciplinaires. Le nom du local est une invention du Suédois August Strindberg et du poète allemand Richard Dehmel.

Detlev von Liliencron

Parmi les personnages qu’y rencontre Moeller, on trouve un poète, aujourd’hui largement oublié, Detlev von Liliencron. Il est un poète-soldat du 19ème siècle: il a fait les guerres de l’unification allemande, en 1864, en 1866 et en 1870, contre les Danois, les Autrichiens et les Français. Son oeuvre majeure est “Adjutantenritte und andere Geschichten” (“Les chevauchées d’un aide de camp et autres histoires”) qui parait en 1883, où il narre ses mésaventures militaires. En 1888, dans la même veine, il publie “Unter flatternden Fahnen” (“Sous les drapeaux qui claquent au vent”). C’est un aristocrate pauvre du Slesvig-Holstein qui a opté pour la vie de caserne mais qui s’adonne au jeu avec beaucoup trop de frénésie, espérant redorer son blason. Le jeu devient chez lui un vice persistant qui brisera sa carrière militaire. Sur le plan littéraire, Detlev von Liliencron est une figure de transition: les aspects néo-romantiques, naturalistes et expressionnistes se succèdent dans ses oeuvres de prose et de poésie. Il refuse les étiquettes, refuse aussi de s’encroûter dans un style figé. Simultanément, ce reître rejette la vie moderne, proposée par la nouvelle société industrielle de l’Allemagne post-bismarckienne et wilhelminienne. Il entend demeurer un “cavalier picaresque”, refuse d’abandonner ce statut, plus exaltant qu’une carrière de rond-de-cuir inculte et étriqué. Il influencera Rilke et von Hoffmannsthal. Le destin de poète et de prosateur picaresque de Detlev von Liliencron a un impact sur Moeller van den Bruck (comme il en aura un aussi, sans doute, sur Ernst Jünger): Moeller, comme von Liliencron, voudra toujours aller “au-delà du donné conventionnel bourgeois”, d’où l’idée de “jouvance”, l’utilisation systématique et récurrente du terme “jeune”: est “jeune” qui veut conserver le fond sans les formes mortes, dans la mesure où les fonds ne meurent jamais et les formes meurent toujours. Il y a là sans nul doute un impact du nietzschéisme qui prend son envol: l’homme supérieur (dont le poète selon Baudelaire) se hisse très haut au-dessus des ronrons inlassablement répétés des philistins. Depuis les soirées du “Schwarzer Ferkel” et les rencontres avec von Liliencron, Moeller s’intéresse aux transitions, entendra favoriser les transitions, au détriment des fixités mentales ou idéologiques. Etre actif en ère de transition, aimer cet état de passage, vouloir être perpétuellement en état de mouvance et de quête, est la tâche sociale et nationale du littérateur et du séismographe, figure supérieure aux “encroûtés” de tous acabits, installés dans leurs créneaux étroits, où ils répétent inlassablement les mêmes gestes ou assument les mêmes fonctions formelles.

Richard Dehmel

Deuxième figure importante pour l’itinéraire de Moeller van den Bruck, rencontrée dans les boîtes de la nouvelle bohème berlinoise: Richard Dehmel (1863-1920). Cet homme a de solides racines rurales. Son père était garde forestier et fonctionnaire des eaux et forêts. Contrairement à Moeller, il a bénéficié d’une bonne scolarité, il détient son “Abitur” mais n’a pas été l’élève modèle que souhaitent tous les faux pédagogues abscons: il s’est bagarré physiquement avec le directeur de son collège. Après son adolescence “contestatrice” au “Gymnasium”, il étudie le droit des assurances, adhère à une “Burschenschaft” étudiante puis entame une carrière de juriste auprès d’une compagnie d’assurances. Simultanément, il commence à publier ses poèmes. Il participe au journal avant-gardiste “Pan”, organe du “Jugendstil” (“Art Nouveau”), avec le sculpteur et peintre Franz von Stuck et le concepteur, architecte et styliste belge Henri van de Velde. Cet organe entend promouvoir une esthétique nouvelle, fusion du naturalisme et du symbolisme. Moeller van den Bruck s’y intéresse longuement (entre 1895 et 1900), avant de lui préférer l’architecture ostrogothique de l’Italie de Théodoric (à partir de 1906) et, pour finir, le classicisme prussien (entre 1910 et 1915).

Deuxième figure importante pour l’itinéraire de Moeller van den Bruck, rencontrée dans les boîtes de la nouvelle bohème berlinoise: Richard Dehmel (1863-1920). Cet homme a de solides racines rurales. Son père était garde forestier et fonctionnaire des eaux et forêts. Contrairement à Moeller, il a bénéficié d’une bonne scolarité, il détient son “Abitur” mais n’a pas été l’élève modèle que souhaitent tous les faux pédagogues abscons: il s’est bagarré physiquement avec le directeur de son collège. Après son adolescence “contestatrice” au “Gymnasium”, il étudie le droit des assurances, adhère à une “Burschenschaft” étudiante puis entame une carrière de juriste auprès d’une compagnie d’assurances. Simultanément, il commence à publier ses poèmes. Il participe au journal avant-gardiste “Pan”, organe du “Jugendstil” (“Art Nouveau”), avec le sculpteur et peintre Franz von Stuck et le concepteur, architecte et styliste belge Henri van de Velde. Cet organe entend promouvoir une esthétique nouvelle, fusion du naturalisme et du symbolisme. Moeller van den Bruck s’y intéresse longuement (entre 1895 et 1900), avant de lui préférer l’architecture ostrogothique de l’Italie de Théodoric (à partir de 1906) et, pour finir, le classicisme prussien (entre 1910 et 1915).

Richard Dehmel est d’abord un féroce naturaliste, qui ose publier en 1896, deux poèmes, jugés pornographiques à l’époque, “Weib und Welt” (“Féminité et monde”) et “Venus Consolatrix”. La réaction ne tarde pas: on lui colle un procès pour “pornographie”. Dans les attendus de sa convocation, on peut lire la phrase suivante: “Atteinte aux bons sentiments religieux et moraux”. Il n’est pas condamné mais censuré: le texte peut paraître mais les termes litigieux doivent être noircis! Dehmel est aussi, avec Stefan Zweig, le traducteur d’Emile Verhaeren, avec qui il était lié d’amitié, avant que la première guerre mondiale ne détruisent, quasi définitivement, les rapports culturels entre la Belgique et l’Allemagne. Pour Zweig, qui connaissait et Dehmel et Verhaeren, les deux poètes étaient les “Dioscures d’une poésie vitaliste d’avenir”. Dehmel voyagera beaucoup, comme Moeller. Lors de ses voyages à travers l’Allemagne, Dehmel rencontre Detlev von Liliencron à Hambourg. Cette rencontre avec le vieux reître des guerres d’unification le poussera sans doute à s’engager comme volontaire de guerre en 1914, à l’âge de 51 ans. Il restera deux ans sous les drapeaux, dans l’infanterie de première ligne et non pas dans une planque à l’arrière du front. En 1918, il lance un appel aux forces allemandes pour qu’elles “tiennent”. Le “pornographe” a donc été un vibrant patriote. En 1920, il meurt suite à une infection attrapée pendant la guerre. L’influence de Dehmel sur ses contemporains est conséquente: Richard Strauss, Hans Pfitzner et Arnold Schönberg mettent ses poèmes en musique. Par ailleurs, il a contribué à l’élimination de la pudibonderie littéraire, omniprésente en Europe avant lui et avant Zola: la sexualité est, pour lui, une force qui va briser le ronron des conventions, sortir l’humanité européenne de la cangue des conventions étriquées, d’un moralisme étroit et étouffant, où la joie n’a plus droit de cité. C’est l’époque d’un pansexualisme/panthéisme littéraire, avec Camille Lemonnier, le “Maréchal des lettres belges”, son contemporain (traduit en allemand chez Diederichs), puis avec David Herbert Lawrence, son élève, quand celui-ci pourfend le puritanisme de l’ère victorienne en Angleterre. Il me paraît utile de préciser ici que Dehmel s’est plus que probablement engagé dans les armées du Kaiser parce que l’effervescence culturelle, libératrice, de l’Allemagne de la Belle Epoque devait être défendue contre les forces de l’Entente qui ne représentaient pas, à ses yeux, une telle beauté esthétique; celle-ci ne pourra jamais se déployer sous les platitudes de régimes libéraux, de factures française ou anglaise.

Richard Dehmel est d’abord un féroce naturaliste, qui ose publier en 1896, deux poèmes, jugés pornographiques à l’époque, “Weib und Welt” (“Féminité et monde”) et “Venus Consolatrix”. La réaction ne tarde pas: on lui colle un procès pour “pornographie”. Dans les attendus de sa convocation, on peut lire la phrase suivante: “Atteinte aux bons sentiments religieux et moraux”. Il n’est pas condamné mais censuré: le texte peut paraître mais les termes litigieux doivent être noircis! Dehmel est aussi, avec Stefan Zweig, le traducteur d’Emile Verhaeren, avec qui il était lié d’amitié, avant que la première guerre mondiale ne détruisent, quasi définitivement, les rapports culturels entre la Belgique et l’Allemagne. Pour Zweig, qui connaissait et Dehmel et Verhaeren, les deux poètes étaient les “Dioscures d’une poésie vitaliste d’avenir”. Dehmel voyagera beaucoup, comme Moeller. Lors de ses voyages à travers l’Allemagne, Dehmel rencontre Detlev von Liliencron à Hambourg. Cette rencontre avec le vieux reître des guerres d’unification le poussera sans doute à s’engager comme volontaire de guerre en 1914, à l’âge de 51 ans. Il restera deux ans sous les drapeaux, dans l’infanterie de première ligne et non pas dans une planque à l’arrière du front. En 1918, il lance un appel aux forces allemandes pour qu’elles “tiennent”. Le “pornographe” a donc été un vibrant patriote. En 1920, il meurt suite à une infection attrapée pendant la guerre. L’influence de Dehmel sur ses contemporains est conséquente: Richard Strauss, Hans Pfitzner et Arnold Schönberg mettent ses poèmes en musique. Par ailleurs, il a contribué à l’élimination de la pudibonderie littéraire, omniprésente en Europe avant lui et avant Zola: la sexualité est, pour lui, une force qui va briser le ronron des conventions, sortir l’humanité européenne de la cangue des conventions étriquées, d’un moralisme étroit et étouffant, où la joie n’a plus droit de cité. C’est l’époque d’un pansexualisme/panthéisme littéraire, avec Camille Lemonnier, le “Maréchal des lettres belges”, son contemporain (traduit en allemand chez Diederichs), puis avec David Herbert Lawrence, son élève, quand celui-ci pourfend le puritanisme de l’ère victorienne en Angleterre. Il me paraît utile de préciser ici que Dehmel s’est plus que probablement engagé dans les armées du Kaiser parce que l’effervescence culturelle, libératrice, de l’Allemagne de la Belle Epoque devait être défendue contre les forces de l’Entente qui ne représentaient pas, à ses yeux, une telle beauté esthétique; celle-ci ne pourra jamais se déployer sous les platitudes de régimes libéraux, de factures française ou anglaise.

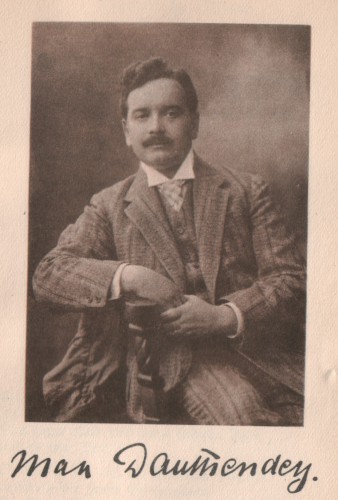

Max Dauthendey

Troisième figure rencontrée dans les cafés littéraires de Berlin, plutôt oubliée aujourd’hui, elle aussi: Max Dauthendey (1867-1918). Il est le fils d’un photographe et daguerrotypiste. Il a vécu à Saint-Pétersbourg où il représentait les affaires de son père. C’était le premier atelier du genre en Russie tsariste. Le jeune Max est le fils d’un second mariage et le seul héritier d’un père qu’il déteste, parce qu’il lui administrait un peu trop souvent la cravache. Ce conflit père/fils va générer dans l’âme du jeune Max une haine des machines et des laboratoires, lui rappelant trop l’univers paternel. Il fugue deux fois, à treize ans puis à dix-sept ans où il se porte volontaire dans un régiment étranger des armées néerlandaises en partance pour Java. Après cet intermède militaire en Insulinde, il se réconcilie avec son père et travaille à l’atelier. En 1891, il s’effondre sur le plan psychique, séjourne dans un centre spécialisé en neurologie et, avec la bénédiction paternelle, cette fois, s’adonne définitivement à la poésie, sous la double influence de Dehmel et du poète polonais Stanislas Przybyszewski (1868-1927). Il fréquente les cafés littéraires et voyage beaucoup, en Suède, à Paris, en Sicile (comme Jünger plus tard), au Mexique (comme D. H. Lawrence), en Grèce et en Italie. Cette existence vagabonde le plonge finalement dans la misère: il est obligé de vivre aux crochets de toutes sortes de gens. Il décide toutefois, à peine renfloué, de faire un tour du monde. Il embarque à Hambourg le 15 avril 1914 et arrive pour la deuxième fois de sa vie à Java, où il restera quatre ans. Impossible d’aller plus loin: la guerre le force à l’immobilité. Il meurt de la malaria en Indonésie en août 1918. Peu apprécié des autorités nationales-socialistes qui le camperont comme un “exotiste”, son oeuvre disparaîtra petit à petit des mémoires. Sa femme découvre dans son appartement de Dresde 300 aquarelles, qui disparaîtront en fumée lors du bombardement de la ville d’art en février 1945.

Troisième figure rencontrée dans les cafés littéraires de Berlin, plutôt oubliée aujourd’hui, elle aussi: Max Dauthendey (1867-1918). Il est le fils d’un photographe et daguerrotypiste. Il a vécu à Saint-Pétersbourg où il représentait les affaires de son père. C’était le premier atelier du genre en Russie tsariste. Le jeune Max est le fils d’un second mariage et le seul héritier d’un père qu’il déteste, parce qu’il lui administrait un peu trop souvent la cravache. Ce conflit père/fils va générer dans l’âme du jeune Max une haine des machines et des laboratoires, lui rappelant trop l’univers paternel. Il fugue deux fois, à treize ans puis à dix-sept ans où il se porte volontaire dans un régiment étranger des armées néerlandaises en partance pour Java. Après cet intermède militaire en Insulinde, il se réconcilie avec son père et travaille à l’atelier. En 1891, il s’effondre sur le plan psychique, séjourne dans un centre spécialisé en neurologie et, avec la bénédiction paternelle, cette fois, s’adonne définitivement à la poésie, sous la double influence de Dehmel et du poète polonais Stanislas Przybyszewski (1868-1927). Il fréquente les cafés littéraires et voyage beaucoup, en Suède, à Paris, en Sicile (comme Jünger plus tard), au Mexique (comme D. H. Lawrence), en Grèce et en Italie. Cette existence vagabonde le plonge finalement dans la misère: il est obligé de vivre aux crochets de toutes sortes de gens. Il décide toutefois, à peine renfloué, de faire un tour du monde. Il embarque à Hambourg le 15 avril 1914 et arrive pour la deuxième fois de sa vie à Java, où il restera quatre ans. Impossible d’aller plus loin: la guerre le force à l’immobilité. Il meurt de la malaria en Indonésie en août 1918. Peu apprécié des autorités nationales-socialistes qui le camperont comme un “exotiste”, son oeuvre disparaîtra petit à petit des mémoires. Sa femme découvre dans son appartement de Dresde 300 aquarelles, qui disparaîtront en fumée lors du bombardement de la ville d’art en février 1945.

Stanislas Przybyszewski

Quatrième figure: Stanislas Przybyszewski, un Polonais qui a étudié en allemand à Thorn en Posnanie. Lui aussi, comme Moeller et Dehmel, a eu une scolarité difficile: il a multiplié les querelles vigoureuses avec ses condisciples et son directeur. Cela ne l’empêche pas d’aller ensuite étudier à l’université la médecine et l’architecture. Il adhère d’abord au socialisme et fonde la revue “Gazeta Robotnicza” (= “La gazette ouvrière”). En deuxièmes noces, il épouse une figure haute en couleurs, Dagny Juel, une aventurière norvégienne, rencontrée lors d’un voyage au pays des fjords. Elle mourra quelques années plus tard en Géorgie où elle avait suivi l’un de ses nombreux amants. Lecteur de Nietzsche, comme beaucoup de ses contemporains, Przybyszewski est amené à réfléchir sur les notions de “Bien” et de “Mal” et, dans la foulée de ces réflexions, à s’intéresser au satanisme. Il fonde en 1898 la revue “Zycie” (= “La Vie”), couplant, Zeitgeist oblige, l’intérêt pour le mal (inséparable du bien et défini selon des critères étrangers à toute morale conventionnelle et répétitive), l’intérêt pour l’oeuvre de Nietzsche et de Strindberg et pour le vitalisme. Avant que ne se déclenche la première grande conflagration inter-européenne de 1914, il devient le chef de file du mouvement artistique, littéraire et culturel des “Jeunes Polonais” (“Mloda Polska”), fondé par Artur Gorski (1870-1959), quand la Pologne était encore incluse dans l’Empire du Tsar. La préoccupation majeure de ce mouvement culturel, partiellement influencé par Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949), est de s’interroger sur le rapport entre puissance créatrice et vie réelle. En ce sens, la tâche de l’art est de saisir l’“être originel” des choses et de le présenter sous forme de symboles, que seul une élite ténue est capable de comprendre (même optique chez l’architecte Henri van de Velde). Mloda Polska connaît un certain succès et s’affichera pro-allemand pendant la première guerre mondiale, tout comme le futur chef incontesté de la nouvelle Pologne, le Maréchal Pilsudski.

Quatrième figure: Stanislas Przybyszewski, un Polonais qui a étudié en allemand à Thorn en Posnanie. Lui aussi, comme Moeller et Dehmel, a eu une scolarité difficile: il a multiplié les querelles vigoureuses avec ses condisciples et son directeur. Cela ne l’empêche pas d’aller ensuite étudier à l’université la médecine et l’architecture. Il adhère d’abord au socialisme et fonde la revue “Gazeta Robotnicza” (= “La gazette ouvrière”). En deuxièmes noces, il épouse une figure haute en couleurs, Dagny Juel, une aventurière norvégienne, rencontrée lors d’un voyage au pays des fjords. Elle mourra quelques années plus tard en Géorgie où elle avait suivi l’un de ses nombreux amants. Lecteur de Nietzsche, comme beaucoup de ses contemporains, Przybyszewski est amené à réfléchir sur les notions de “Bien” et de “Mal” et, dans la foulée de ces réflexions, à s’intéresser au satanisme. Il fonde en 1898 la revue “Zycie” (= “La Vie”), couplant, Zeitgeist oblige, l’intérêt pour le mal (inséparable du bien et défini selon des critères étrangers à toute morale conventionnelle et répétitive), l’intérêt pour l’oeuvre de Nietzsche et de Strindberg et pour le vitalisme. Avant que ne se déclenche la première grande conflagration inter-européenne de 1914, il devient le chef de file du mouvement artistique, littéraire et culturel des “Jeunes Polonais” (“Mloda Polska”), fondé par Artur Gorski (1870-1959), quand la Pologne était encore incluse dans l’Empire du Tsar. La préoccupation majeure de ce mouvement culturel, partiellement influencé par Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949), est de s’interroger sur le rapport entre puissance créatrice et vie réelle. En ce sens, la tâche de l’art est de saisir l’“être originel” des choses et de le présenter sous forme de symboles, que seul une élite ténue est capable de comprendre (même optique chez l’architecte Henri van de Velde). Mloda Polska connaît un certain succès et s’affichera pro-allemand pendant la première guerre mondiale, tout comme le futur chef incontesté de la nouvelle Pologne, le Maréchal Pilsudski.

Après 1918, comme Moeller van den Bruck, Przybyszewski s’engage en politique et travaille à construire le nouvel Etat polonais indépendant, tout en poursuivant sa quête philosophique et son oeuvre littéraire. Pour Przybyszewski, comme par ailleurs pour le Moeller van den Bruck du voyage en Italie (1906), l’art dévoile le fond de l’être: la part ténue d’humanité émancipée des pesanteurs conventionnelles (bourgeoises) atteint peut-être le sublime en découvrant ce “fond” mais cette élévation et cette libération sont simultanément un plongeon dans les recoins les plus sombres de l’âme et dans le tragique (on songe, mutatis mutandi, au thème d’“Orange mécanique” d’Anthony Burgess et du film du même nom de Stanley Kubrik). Les noctambules, les dégénérés et les déraillés, ainsi que la lutte des sexes (Strindberg, Weininger), intéressent notre auteur polonais, qui voulait devenir psychiatre au terme de ses études inachevées de médecine, comme ils avaient intéressé Dostoïevski, observateur avisé du public des bistrots de Saint-Pétersbourg. En 1897, leur sort, leurs errements sont l’objet d’un livre qui connaîtra deux titres “Die Gnosis des Bösen” et “Die Synagoge Satans”.

Figure plus exubérante que Moeller, Przybyszewski fait la jonction entre l’univers artistique d’avant 1914 et la nécessité de reconstruire le politique après 1918. La trajectoire du Polonais a sûrement influencé les attitudes de l’Allemand. Des parallèles peuvent aisément être tracés entre leurs deux itinéraires, en dépit de la dissemblance entre leurs personnalités.

Les cabarets

Parmi tous les clubs et lieux de rencontre de cette incroyable bohème littéraire, il y a bien sûr les cabarets, où les animateurs critiquent à fond les travers de la société wilhelminienne, qui, par son fort tropisme technicien, oublie le “fonds” au profit de “formes” sans épaisseur temporelle ni charnelle. A Berlin, c’est le cabaret “Überbretteln” qui donne le ton. Il s’est délibérément calqué sur son homologue parisien “Le Chat noir” de Montmartre, créé par Rodolphe Salis. Sous la dynamique impulsion d’Ernst von Wolzogen, il s’ouvre le 18 janvier 1901. A Munich, le principal cabaret contestataire est “Die Elf Scharfrichter”, où sévit Frank Wedekind. Celui-ci est maintes fois condamné pour obscénité ou pour lèse-majesté: il a certes critiqué, de la façon la plus caustique qui soit, l’Empereur et le militarisme mais, Wedekind, puis Wolzogen, qui l’épaulera, ne sont pas des figures de l’anti-patriotisme: ils veulent simplement une “autre nation” et surtout une autre armée. Leur but est de multiplier les scandales pour forcer les Allemands à réfléchir, à abandonner toutes postures figées. Dans ce sens, et pour revenir à Moeller van den Bruck, qui vit au beau milieu de cette effervescence, inégalée en Europe jusqu’ici, ces cabarets sont des instances de la “transition”, vers un Reich (ou une Cité) plus “jeune”, neuf, ouvert en permanence et volontairement à toutes les innovations ravigorantes.

L’époque berlinoise de Moeller van den Bruck a duré six ans, de 1896 à 1902. Dans ces cercles, il circule en affichant le style du dandy, sans doute inspiré par Barbey d’Aurevilly. Moeller est quasi toujours vêtu d’un long manteau de cuir, coiffé d’un haut-de-forme gris, l’oeil cerclé par un monocle. Il parle un langage simple mais châtié, sans doute pour compenser son absence de formation post-secondaire. Il est un digne et quiet héritier de Brummell. En 1902, sa femme Hedda est enceinte. La fortune héritée du grand-père van den Bruck est épuisée. Il abandonne sa femme, qui se remariera avec un certain Herbert Eulenberg, appartenant à une famille qui sera radicalement anti-nazie. Elle continuera à traduire des oeuvres littéraires françaises et anglaises jusqu’en 1936, quand le pouvoir en place lui interdira toute publication.

Arrivée à Paris

Moeller van den Bruck quitte donc l’Allemagne pour Paris où il arrive fin 1902. On dit parfois qu’il a cherché à échapper au service militaire: les patriotes, en effet, ne sont pas tous militaristes dans l’Allemagne wilhelminienne et Moeller n’a pas encore vraiment pris conscience de sa germanité, comme nous allons le voir. Les patriotes non militaristes reprochent à l’Empereur Guillaume II de fabriquer un “militarisme de façade”, encadré par des officiers caricaturaux et souvent incompétents, parce qu’il a fallu recruter des cadres dans des strates de la population qui n’ont pas la vraie fibre militaire et compensent cette lacune par un autoritarisme ridicule. C’est ainsi que Wedekind dénonçait le militarisme wilhelminien sur les planches du cabaret “Die Elf Scharfrichter”. Son anti-militarisme n’est donc pas un anti-militarisme de fond mais une volonté de mettre sur pied une armée plus jeune, plus percutante.

Dès son arrivée dans la capitale française, une idée le travaille: il l’a puisée dans sa lecture des oeuvres de Jakob Burckhardt. On ne peut pas être simultanément une grande culture comme l’Allemagne et peser d’un grand poids politique sur l’échiquier planétaire comme la Grande-Bretagne ou la France. Pour Moeller, lecteur de Burckhardt, il y a contradiction entre élévation culturelle et puissance politique: nous avons là l’éclosion d’une thématique récurrente dans les débats germano-allemands sur la germanité et l’essence de l’Allemagne; elle sera analysée, dans une perspective particulièrement originale par Christoph Steding en 1934: celui-ci fustigera l’envahissement de la culture allemande par tout un fatras “impolitique” et esthétisant, importé de Scandinavie, de Hollande et de Suisse. En ce sens, Steding dépasse complètement Moeller van den Bruck, encore lié à cette culture qu’il juge “impolitique”; toutefois, c’est au sein de cette culture impolitique qu’ont baigné ceux qui, après 1918, ont voulu oeuvrer à la restauration “impériale”. Le primat du culturel sur le politique sera également moqué dans un dessin de Paul A. Weber montrant un intellectuel binoclard, malingre et macrocéphale, jetant avec rage des livres de philo contre un tank britannique (de type Mk. I) qui défonce un mur et fait irruption dans sa bibliothèque; le chétif intello “mitteleuropéen” hurle: “Je vous pulvérise tous par la puissance de mes pensées!”.

Récemment, en 2010, Peter Watson, journaliste, historien, attaché à l’Université d’Oxford, campe l’envol vertigineux de la pensée et des sciences allemandes au 19ème siècle comme une “troisième renaissance” et comme une “seconde révolution scientifique”, dans un ouvrage qui connaîtra un formidable succès en Angleterre et aux Etats-Unis, malgré ses 964 pages en petits caractères (cf. “The German Genius – Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution and the Twentieth Century”, Simon & Schuster, London/New York, 2010). Ce gros livre est destiné à bannir la germanophobie stérile qui a frappé, pendant de longues décennies, la pensée occidentale; il réhabilite la “Kultur” que l’on avait méchamment moquée depuis août 1914 mais cherche tout de même, subrepticement, à maintenir la germanité contemporaine dans un espace mental impolitique. La culture germanique depuis le début du 19ème, c’est fantastique, démontre Watson, mais il ne faut pas lui donner une épaisseur et une vigueur politiques: celles-ci ne peuvent être que de dangereux ou navrants dérapages. Watson évoque Moeller van den Bruck (pp. 616-618). L’interrogation de Moeller van den Bruck demeure dont d’actualité: on tente encore et toujours d’appréhender et de définir les contradictions existantes entre la grandeur culturelle de l’Allemagne et son nanisme politique sur l’échiquier européen ou mondial, entre l’absence de profondeur intellectuelle et de musicalité de la France républicaine et du monde anglo-saxon et leur puissance politique sur la planète.

Moeller van den Bruck découvre la pensée russe à Paris

Les quatre années parisiennes de Moeller van den Bruck ne vont pas renforcer la part française de sa pensée, acquise à Berlin lors de ses travaux de traduction réalisés avec le précieux concours d’Hedda Maase. A Paris —où il retrouve Dauthendey et le peintre norvégien Munch à la “Closerie des Lilas”— c’est la part russe de son futur univers mental qu’il va acquérir. Il y rencontre deux soeurs, Lucie et Less Kaerrick, des Allemandes de la Baltique, sujettes du Tsar. Lucie deviendra rapidement sa deuxième épouse. Le couple va s’atteler à la traduction de l’oeuvre entière de Dostoïevski (vingt tomes publiés à Munich chez Piper entre le séjour parisien et le déclenchement de la première guerre mondiale). Pour chaque volume, Moeller rédige une introduction, qui disparaîtra des éditions postérieures à 1950. Ces textes, longtemps peu accessibles, figurent toutefois tous sur la grande toile et sont désormais consultables par tout un chacun, permettant de connaître à fond l’apport russe au futur “Jungkonservativismus”, à la “révolution conservatrice” et à l’“Ostideologie” des cercles russophiles nationaux-bolcheviques et prussiens-conservateurs. Moeller est donc celui qui crée l’engouement pour Dostoïevski en Allemagne. L’immersion profonde dans l’oeuvre du grand écrivain russe, qu’il s’inflige, fait de lui un russophile profond qui transmettra sa fascination personnelle à tout le mouvement conservateur-révolutionnaire, “jungkonservativ”, après 1918.

L’anti-occidentalisme politique et géopolitique, qui transparaît en toute limpidité dans le “Journal d’un écrivain” de Dostoïevski, a eu un impact déterminant dans la formation et la maturation de la pensée de Moeller van den Bruck. En effet, ce “Journal” récapitule, entre bien d’autres choses, l’anthropologie de Dostoïevski et énumère les tares des politiques occidentales. L’anthropologie dostoïevskienne dénonce l’avènement d’un homme se voulant “nouveau”, un homme sans ancêtres qui se promet beaucoup d’enfants: un homme qui a coupé le cordon invisible qui le liait charnellement à sa lignée mais veut se multiplier, se cloner à l’infini dans le futur. Cet homme, auto-épuré de toutes les insuffisances qu’il aurait véhiculées depuis toujours par le biais de son corps créé par Dame Nature, s’enfermera bien vite dans un petit monde clos, dans des “clôtures” et finira par répéter une sorte de catéchisme positiviste, pseudo-scientifique, intellectuel, sec, mécanique, qui n’explique rien. Il ne vivra donc plus de “transitions”, de périodes où l’on innove sans trahir le fonds, puisqu’il n’y aura plus de fonds et qu’il n’y aura plus besoin d’innovations, tout ayant été inventé. Nous avons là l’équivalent russe du dernier homme de Nietzsche, qui affirme ses platitudes “en clignant de l’oeil”. L’avènement de cet “homunculus” est déjà, à l’époque de Dostoïevski, bien perceptible dans le vieil Occident, chez les peuples vieillissants. Et la politique de ces Etats vieillis empêche la vigoureuse vitalité slave (surtout serbe et bulgare) de vider “l’homme malade du Bosphore” (c’est-à-dire l’Empire ottoman) de son lit balkanique, et surtout de la Thrace des Détroits. L’Occident est resté “neutre” dans le conflit suscité par la révolte serbe et bulgare (1877-78), trahissant ainsi la “civilisation chrétienne”, face à son vieil ennemi ottoman, et ne s’est manifesté, intéressé et avide, que pour s’emparer des meilleures dépouilles turques, disponibles parce que les peuples jeunes des Balkans avaient versé leur sang généreux. Phrases qu’on peut considérer comme prémonitoires quand on les lit après les événements de l’ex-Yougoslavie, surtout ceux de 1999...

Rencontre avec Dmitri Merejkovski et Zinaïda Hippius

Moeller refuse donc l’avènement des “homunculi” et apprend, chez Dostoïevski, à respecter l’effervescence des révoltes de peuples encore jeunes, encore capables de sortir des “clôtures” où on cherche à les enfermer. Mais un autre écrivain russe, oublié dans une large mesure mais toujours accessible aujourd’hui, en langue française, grâce aux efforts de l’éditeur suisse “L’Age d’Homme”, aura une influence déterminante sur Moeller van den Bruck: Dmitri Merejkovski. Cet écrivain habitait Paris, lors du séjour de Moeller van den Bruck dans la capitale française, avec son épouse Zinaïda Hippius (ou “Gippius”). L’objectif de Merejkovski était de rénover la pensée orthodoxe tout en maintenant le rôle central de la religion en Russie: rénover la religion ne signifiait pas pour lui l’abolir. Merejkovski était lié au mouvement des “chercheurs de Dieu”, les “Bogoïskateli”. Il éditait une revue, “Novi Pout” (= “La Nouvelle Voie”), où notre auteur envisageait, conjointement au poète Rozanov, de réhabiliter totalement la chair, de réconcilier la chair et l’esprit: idée qui se retrouvait dans l’air du temps avec des auteurs comme Lemonnier ou Dehmel et, plus tard, D. H. Lawrence. Par sa volonté de rénovation religieuse, Merejkovski s’opposait au théologien sourcilleux du Saint-Synode, le “vieillard jaunâtre” Pobedonostsev, intégriste orthodoxe ne tolérant aucune déviance, aussi minime soit-elle, par rapport aux canons qu’il avait énoncés dans le but de voir régner une “paix religieuse” en Russie, une paix hélas figeante, mortifère, sclérosant totalement les élans de la foi. Comme le faisait en Allemagne, dans le sillage de tout un éventail d’auteurs en vue, l’éditeur Eugen Diederichs à Iéna depuis 1896, Merejkovski recherche, dans le monde russe cette fois, de nouvelles formes religieuses. Il rend visite à des sectes, ce qui alarme les services de Pobedonostsev, liés à la police politique tsariste. Son but? Réaliser les prophéties de l’abbé cistercien calabrais Joachim de Flore (1130-1202). Pour cet Italien du 12ème siècle, le “Troisième Testament” allait advenir, inaugurant le règne de l’Esprit Saint dans le monde, après le “Règne du Père” et le “Règne du Fils”. Cette volonté de participer à l’avènement du “Troisième Testament” conduit Merejkovski à énoncer une vision politique, jugée révolutionnaire dans la première décennie du 20ème siècle: Pierre le Grand, fondateur de la dynastie des Romanov, est une figure antéchristique car il a ouvert la Russie aux vices de l’Occident, l’empêchant du même coup d’incarner à terme dans le réel ce “Troisième Testament”, que sa spiritualité innée était à même de réaliser. En émettant cette critique hostile à la dynastie, Merejkovski se pose tout à la fois comme révolutionnaire dans le contexte de 1905 et comme “archi-conservateur” puisqu’il veut un retour à la Russie d’avant les Romanov, une contestation qui, aujourd’hui encore, brandit le drapeau noir-blanc-or des ultra-monarchistes qui considèrent la Russie, même celle de Poutine avec son drapeau bleu-rouge-blanc, comme une aberration occidentalisée. En 1905 donc, la Russie qui s’est alignée sur l’Occident depuis Pierre le Grand subit la punition de Dieu: elle perd la guerre qui l’oppose au Japon. L’armée, qui tire dans le tas contre les protestataires emmenés par le Pope Gapone, est donc l’instrument des forces antéchristiques. Le Tsar étant, dans un tel contexte, lui aussi, une figure avancée par l’Antéchrist. La monarchie des Romanov est posée par Merejkovski comme d’essence non chrétienne et non russe. Mais en cette même année 1905, Merejkovski sort un ouvrage très important, intitulé “L’advenance de Cham” ou, en français, “L’avènement du Roi-Mufle”.

Moeller refuse donc l’avènement des “homunculi” et apprend, chez Dostoïevski, à respecter l’effervescence des révoltes de peuples encore jeunes, encore capables de sortir des “clôtures” où on cherche à les enfermer. Mais un autre écrivain russe, oublié dans une large mesure mais toujours accessible aujourd’hui, en langue française, grâce aux efforts de l’éditeur suisse “L’Age d’Homme”, aura une influence déterminante sur Moeller van den Bruck: Dmitri Merejkovski. Cet écrivain habitait Paris, lors du séjour de Moeller van den Bruck dans la capitale française, avec son épouse Zinaïda Hippius (ou “Gippius”). L’objectif de Merejkovski était de rénover la pensée orthodoxe tout en maintenant le rôle central de la religion en Russie: rénover la religion ne signifiait pas pour lui l’abolir. Merejkovski était lié au mouvement des “chercheurs de Dieu”, les “Bogoïskateli”. Il éditait une revue, “Novi Pout” (= “La Nouvelle Voie”), où notre auteur envisageait, conjointement au poète Rozanov, de réhabiliter totalement la chair, de réconcilier la chair et l’esprit: idée qui se retrouvait dans l’air du temps avec des auteurs comme Lemonnier ou Dehmel et, plus tard, D. H. Lawrence. Par sa volonté de rénovation religieuse, Merejkovski s’opposait au théologien sourcilleux du Saint-Synode, le “vieillard jaunâtre” Pobedonostsev, intégriste orthodoxe ne tolérant aucune déviance, aussi minime soit-elle, par rapport aux canons qu’il avait énoncés dans le but de voir régner une “paix religieuse” en Russie, une paix hélas figeante, mortifère, sclérosant totalement les élans de la foi. Comme le faisait en Allemagne, dans le sillage de tout un éventail d’auteurs en vue, l’éditeur Eugen Diederichs à Iéna depuis 1896, Merejkovski recherche, dans le monde russe cette fois, de nouvelles formes religieuses. Il rend visite à des sectes, ce qui alarme les services de Pobedonostsev, liés à la police politique tsariste. Son but? Réaliser les prophéties de l’abbé cistercien calabrais Joachim de Flore (1130-1202). Pour cet Italien du 12ème siècle, le “Troisième Testament” allait advenir, inaugurant le règne de l’Esprit Saint dans le monde, après le “Règne du Père” et le “Règne du Fils”. Cette volonté de participer à l’avènement du “Troisième Testament” conduit Merejkovski à énoncer une vision politique, jugée révolutionnaire dans la première décennie du 20ème siècle: Pierre le Grand, fondateur de la dynastie des Romanov, est une figure antéchristique car il a ouvert la Russie aux vices de l’Occident, l’empêchant du même coup d’incarner à terme dans le réel ce “Troisième Testament”, que sa spiritualité innée était à même de réaliser. En émettant cette critique hostile à la dynastie, Merejkovski se pose tout à la fois comme révolutionnaire dans le contexte de 1905 et comme “archi-conservateur” puisqu’il veut un retour à la Russie d’avant les Romanov, une contestation qui, aujourd’hui encore, brandit le drapeau noir-blanc-or des ultra-monarchistes qui considèrent la Russie, même celle de Poutine avec son drapeau bleu-rouge-blanc, comme une aberration occidentalisée. En 1905 donc, la Russie qui s’est alignée sur l’Occident depuis Pierre le Grand subit la punition de Dieu: elle perd la guerre qui l’oppose au Japon. L’armée, qui tire dans le tas contre les protestataires emmenés par le Pope Gapone, est donc l’instrument des forces antéchristiques. Le Tsar étant, dans un tel contexte, lui aussi, une figure avancée par l’Antéchrist. La monarchie des Romanov est posée par Merejkovski comme d’essence non chrétienne et non russe. Mais en cette même année 1905, Merejkovski sort un ouvrage très important, intitulé “L’advenance de Cham” ou, en français, “L’avènement du Roi-Mufle”.

L’advenance de Cham

Cham est le fils de Noé (Noah) qui s’est moqué de son père (de son ancêtre direct); à ce titre, il est une figure négative de la Bible, le symbole d’une humanité déchue en canaille, qui rompt délibérément le pacte intergénérationnel, brise la continuité qu’instaure la filiation. C’est cette figure négative, comparable à l’“homme sans ancêtres” de l’anthropologie dostoïevskienne, qui adviendra dans le futur, qui triomphera. Le Cham de Merejkovski est un cousin, un frère, une figure parallèle à cet “homunculus” de Dostoïevski. Dans “L’advenance de Cham”, Merejkovski développe une vision apocalyptique de l’histoire, articulée en trois volets. Il y a eu un passé déterminé par une église orthodoxe figée, celle de Pobedonostsev qui a abruti les hommes, en les enfermant dans des corsets confessionnels trop étriqués, jugulant les élans créateurs et bousculants de la foi et, eux seuls, peuvent réaliser le “Troisième Testament”. Il y a un présent où se déploie une bureaucratie d’Etat, dévoyant la fonction monarchique, la rendant imparfaite et lui inoculant des miasmes délétères, tout en conservant comme des reliques dévitalisées et le Saint-Synode et la monarchie. Il y aura un futur, où ce bureaucratisme se figera et donnera lieu à la révolte de la lie de la société, qui imposera par la violence la “tyrannie de Cham”, véritable cacocratie, difficile à combattre tant elle aura installé des “clôtures” dans le cerveau même des hommes. Merejkovski se veut alors prophète: quand Cham aura triomphé, l’Eglise sera détruite, la monarchie aussi et l’Etat, système abstrait et contraignant, se sera consolidé, devenant un appareil inamovible, lourd, inébranlable. Et l’âme russe dans ce processus? Merejkovski laisse la question ouverte: constituera-t-elle un môle de résistance? Sera-t-elle noyée dans le processus? Interrogations que Soljénitsyne reprendra à son compte pendant son long exil américain.

Itinéraire de Merejkovski

En 1914, Merejkovski se déclare pacifiste, sans doute ne veut-il ni faire alliance avec les vieilles nations occidentales, ennemies de la Russie au 19ème siècle et qui se servent désormais de la chair à canon russe pour broyer leur concurrent allemand, ni avec une Allemagne wilhelminienne qui, elle aussi, ne correspond plus à aucun critère traditionnel d’excellence politique. En 1917, quand éclate la révolution à Saint-Pétersbourg, Merejkovski se proclame immédiatement anti-communiste: les soulèvements menchevik et bolchevique sont pour lui les signes de l’avènement de Cham. Ils créeront le “narod-zver”, le peuple-Bête, serviteur de la Bête de l’Apocalypse. Ces révolutions, ajoute-t-il, “feront disparaître les visages”, uniformiseront les expressions faciales; le peuple ne sera plus que de la “viande chinoise”, le terme “chinois” désignant dans la littérature russe de 1890 à 1920 l’état de dépersonnalisation totale, auquel on aboutit sous la férule d’une bureaucratie omni-contrôlante, d’un mandarinat à la chinoise et d’un despotisme fonctionnarisé, étranger aux tréfonds de l’âme européenne et du personnalisme inhérent au message chrétien (dans l’aire culturelle germanophone, le processus de “dé-facialisation” de l’humanité sera dénoncé et décrit par Rudolf Kassner, sur base d’éléments préalablement trouvés dans l’oeuvre du “sioniste nietzschéen” Max Nordau). En 1920, Merejkovski appelle les Russes anti-communistes à se joindre à l’armée polonaise pour lutter contre les armées de Trotski et de Boudiénny. Fin juin 1941, il prononce un discours à la radio allemande pour appeler les Russes blancs à libérer leur patrie en compagnie des armées du Reich. Il meurt à Paris avant l’arrivée des armées anglo-saxonnes, échappant ainsi à l’épuration. Son épouse, éplorée, entame, nuit et jour, la rédaction d’une biographie intellectuelle de son mari: elle meurt épuisée en 1946 avant de l’avoir achevée. Ce travail demeure néanmoins la principale source pour connaître l’itinéraire exceptionnel de Merejkovski.

Traduction de l’oeuvre entière de Dostoïevski, fréquentation de Dmitri Merejkovski: voilà l’essentiel des années parisiennes de Moeller van den Bruck. Les années berlinoises (1896-1902) avaient été essentiellement littéraires et artistiques. Moeller recherchait des formes nouvelles, un “art nouveau” (qui n’était pas nécessairement le “Jugendstil”), adapté à l’ère de la production industrielle, exprimant l’effervescence vitale des “villes tentaculaires” (Verhaeren). De même, il s’était profondément intéressé aux formes nouvelles qu’adoptait la littérature de la Belle Epoque. A Paris, il prend conscience de sa germanité, tout en devenant russophile et anti-occidentaliste. Il constate que les Français sont un peuple tendu vers la politique, tandis que les Allemands n’ont pas de projet commun et pensent les matières politiques dans la dispersion la plus complète. Les Français sont tous mobilisés par l’idée de revanche, de récupérer deux provinces constitutives du défunt “Saint-Empire”, qui, depuis Louis XIV, servent de glacis à leurs armées pour contrôler tout le cours du Rhin et tenir ainsi tout l’ensemble territorial germanique à leur merci. Barrès, pourtant frotté de culture germanique et wagnérienne, incarne dans son oeuvre, ses discours et ses injonctions, cette tension vers la ligne bleue des Vosges et vers le Rhin. Rien de pareil en Allemagne, où, sur le plan politique, ne règne que le désordre dans les têtes. Les premiers soubresauts de la crise marocaine (de 1905 à 1911) confirment, eux aussi, la politisation virulente des Français et l’insouciance géopolitique des Allemands.

“Die Deutschen”: huit volumes

Moeller tente de pallier cette lacune dangereuse qu’il repère dans l’esprit allemand de son époque. En plusieurs volumes, il campe des portraits d’Allemands (“Die Deutschen”) qui, à ses yeux, ont donné de la cohérence et de l’épaisseur à la germanité. De chacun de ces portraits se dégage une idée directrice, qu’il convient de ramener à la surface, à une époque de dispersion et de confusion politiques. L’ouvrage “Die Deutschen”, en huit volumes, parait de 1904 à 1910. Il constitue l’entrée progressive de Moeller van den Bruck dans l’univers de la “germanité germanisante” et du nationalisme, qu’il n’avait quasi pas connu auparavant —von Liliencron et Dehmel ayant eu, malgré leur nationalisme diffus, des préoccupations bien différentes de celles de la politique. Ce nationalisme nouveau, esquissé par Moeller en filigrane dans “Die Deutschen”, ne dérive nullement des formes diverses de ce pré-nationalisme officiel et dominant de l’ère wilhelminienne dont les ingrédients majeurs sont, sur fond du pouvoir personnalisé de l’Empereur Guillaume II, la politique navale, le mouvement agrarien radical (souvent particulariste et régional), l’antisémitisme naissant, etc. Le mouvement populaire agrarien oscillait —l’ “oscillation” chère à Jean-Pierre Faye, auteur du gros ouvrage “Les langages totalitaires”— entre le Zentrum catholique, la sociale-démocratie, la gauche plus radicale ou le parti national-libéral d’inspiration bismarckienne. Les expressions diverses du nationalisme (agrarien ou autre) de l’ère wilhelminienne n’avaient pas de lieu fixe et spécifique dans le spectre politique: ils “voyageaient” transversalement, pérégrinaient dans toutes les familles politiques, si bien que chacune d’elles avait son propre “nationalisme”, opposé à celui des autres, sa propre vision d’un futur optimal de la nation.

Les transformations rapides de la société allemande sous les effets de l’industrialisation généralisée entraînent la mobilisation politique de strates autrefois quiètes, dépolitisées, notamment les petits paysans indépendants ou inféodés à de gros propriétaires terriens (en Prusse): ils se rassemblent au sein du “Bund der Landwirte”, qui oscille surtout entre les nationaux-libéraux prussiens et le Zentrum (dans les régions catholiques). Cette mobilisation de l’élément paysan de base, populaire et révolutionnaire, fait éclater le vieux conservatisme et ses structures politiques, traditionnellement centrées autour des vieux pouvoirs réels ou diffus de l’aristocratie terrienne. Le vieux conservatisme, pour survivre politiquement, se mue en d’autres choses que la simple “conservation” d’acquis anciens, que la simple défense des intérêts des grands propriétaires aristocratiques, et fusionne lentement, dans un bouillonnement confus et contradictoire s’étalant sur deux bonnes décennies avant 1914, avec des éléments divers qui donneront, après 1918, les nouvelles et diverses formes de nationalisme plus militant, s’exprimant cette fois sans le moindre détour. Le but est, comme dans d’autres pays, d’obtenir, en bout de course, une harmonie sociale nouvelle et régénérante, au nom de théories organiques et “intégrationnistes”. Cette tendance générale —cette pratique moderne et populaire d’agitation— doit faire appel à la mobilisation des masses, critère démocratique par excellence puisqu’il présuppose la généralisation du suffrage universel. C’est donc ce dernier qui fait éclore le nationalisme de masse, qui, de ce fait, est bien —du moins au départ— de nature démocratique, démocratie ne signifiant a priori ni libéralisme ni permissivité libérale et festiviste.

Bouillonnement socio-politique

Moeller van den Bruck demeure éloigné de cette agitation politique —il critique tous les engagements politiques, dans quelque parti que ce soit et ne ménage pas ses sarcasmes sur les pompes ridicules de l’Empereur, “homme sans goût”— mais n’en est pas moins un homme de cette transition générale et désordonnée, encore peu étudiée dans les innombrables avatars qu’elle a produits pendant les deux décennies qui ont précédé 1914. Ce n’est pas dans les comités revendicateurs de la population rurale —ou de la population anciennement rurale entassée dans les nouveaux quartiers insalubres des villes surpeuplées— que Moeller opère sa transition personnelle mais dans le monde culturel, littéraire: il est bien un “Literatentyp”, un “littérateur”, apparemment éloigné de tout pragmatisme politique. Mais le bouillonnement socio-politique, où tentaient de fusionner éléments de gauche et de droite, cherchait un ensemble de thématiques “intégrantes”: il les trouvera dans les multiples définitions qui ont été données de l’“Allemand”, du “Germain”, entre 1880 et 1914. De l’idée mobilisatrice de communisme primitif, germanique ou celtique, évoquée par Engels à l’exaltation de la fraternité inter-allemande dans le combat contre les deux Napoléon (en 1813 et en 1870), il y a un dénominateur commun: un “germanisme” qui se diffuse dans tout le spectre politique; c’est le germanisme des théoriciens politiques (marxistes compris), des philologues et des poètes qui réclament un retour à des structures sociales jugées plus justes et plus équitables, plus conformes à l’essence d’une germanité, que l’on définit avec exaltation en disant sans cesse qu’elle a été oblitérée, occultée, refoulée. Moeller van den Bruck, avec “Die Deutschen”, va tenter une sorte de retour à ce refoulé, de retrouver des modèles, des pistes, des attitudes intérieures qu’il faudra raviver pour façonner un futur européen radieux et dominé par une culture allemande libertaire et non autoritaire, telle qu’elle se manifestait dans un local comme “Zum schwarzen Ferkel”. Toutefois, Moeller soulignera aussi les échecs à éviter dans l’avenir, ceux des “verirrten Deutschen”, des “Allemands égarés”, pour lesquels il garde tout de même un faible, parce qu’ils sont des littérateurs comme lui, tout en démontrant qu’ils ont failli malgré la beauté poignante de leurs oeuvres, qu’ils n’ont pu surmonter le désordre intrinsèque d’une certaine âme allemande et qu’ils ne pourront donc transmettre à l’homme nouveau des “villes tentaculaires” —détaché de tous liens fécondants— cette unité intérieure, cette force liante qui s’estompent sous les coups de l’économisme, de la bureaucratie et de la modernité industrielle, camouflés gauchement par les pompes impériales (le parallèle avec la sociologie de Georg Simmel et avec certains aspects de la pensée de Max Weber est évident ici).

Le voyage en Italie

Après ses quatre années parisiennes, Moeller quitte la France pour l’Italie, où il rencontre le poète Theodor Däubler et lui trouve un éditeur pour son poème de 30.000 vers, “Nordlicht” qui fascinera Carl Schmitt. Il se lie aussi au sculpteur expressionniste Ernst Barlach, qui s’était inspiré du paysannat russe pour parfaire ses oeuvres. Ce sculpteur sera boycotté plus tard par les nationaux-socialistes, en dépit de thématiques “folcistes” qui n’auraient pas dû les effaroucher. Ces deux rencontres lors du voyage en Italie méritent à elles seules une étude. Bornons-nous, ici, à commenter l’impact de ce voyage sur la pensée politique et métapolitique de Moeller van den Bruck. Dans un ouvrage, qui paraîtra à Munich, rehaussé d’illustrations superbes, et qui aura pour titre “Die italienische Schönheit”, Moeller brosse une histoire de l’art italien depuis les Etrusques jusqu’à la Renaissance. Ce n’est ni l’art de Rome ni les critères de Vitruve qui emballent Moeller lors de son séjour en Italie mais l’architecture spécifique de la Ravenne de Théodoric, le roi ostrogoth. Cette architecture, assez “dorienne” dans ses aspects extérieurs, est, pour Moeller, l’“expression vitale d’un peuple”, le “reflet d’un espace particulier”, soit les deux piliers —la populité et la spatialité— sur lesquels doit reposer un art réussi. Plus tard, en réhabilitant le classicisme prussien, Moeller renouera avec un certain art romain, vitruvien dans l’interprétation très classique des Gilly, Schinckel, etc. En 1908, il retourne en Allemagne et se présente au “conseil de révision” pour se faire incorporer dans l’armée. Il effectuera un bref service à Küstrin mais sera rapidement exempté, vu sa santé fragile. Il se fixe ensuite à Berlin mais multiplie les voyages jusqu’en 1914: Londres, Paris, l’Italie (dont plusieurs mois en Sicile), Vienne, les Pays Baltes, la Russie et la Finlande. En 1914, avant que n’éclate la guerre, il est au Danemark et en Suède.

Style prussien et “Deutscher Werkbund”

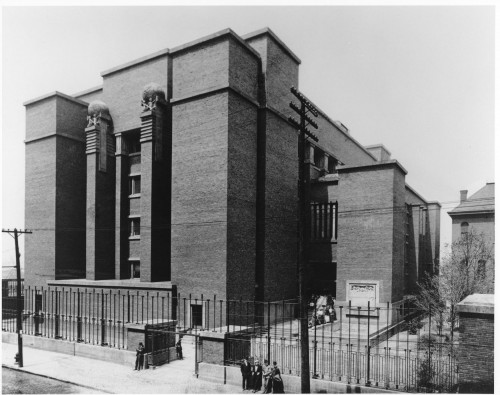

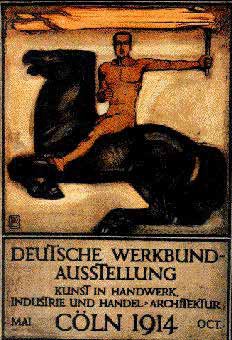

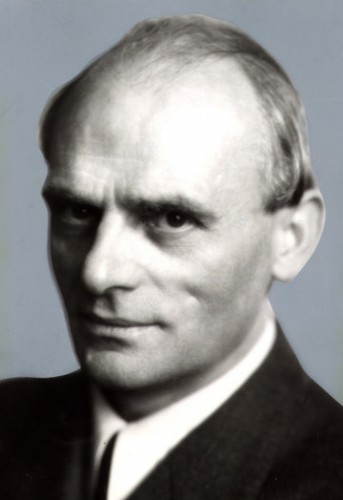

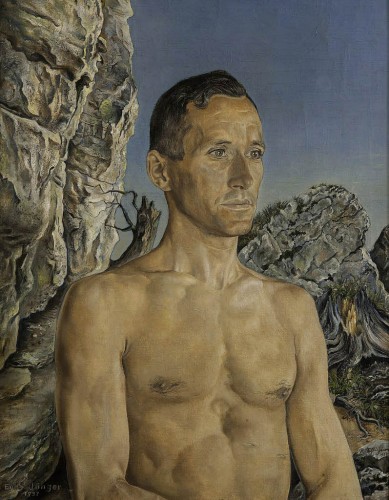

Quand la Grande Guerre se déclenche, Moeller est en train de rédiger “Der preussische Stil”, retour à l’architecture des Gilly, Schinckel et von Klenze mais aussi réflexions générales sur la germanité qui, pour trouver cette unité intérieure recherchée tout au long des huit volumes de “Die Deutschen”, doit opérer un retour à l’austérité dorienne du classicisme prussien et abandonner certaines fantaisies ou ornements prisés lors des décennies précédentes: même constat chez l’ensemble des architectes, qui abandonnent la luxuriance du Jugendstil pour une “Sachlichkeit” plus sobre. La réhabilitation du “style prussien” implique aussi l’abandon de ses anciennes postures de dandy, une exaltation des vertus familiales prussiennes, de la sobriété, de la “Kargheit”, etc. Le livre “Der preussische Stil” sera achevé pendant la guerre, sous l’uniforme. Il s’inscrit dans la volonté de promouvoir des formes nouvelles, tout en gardant un certain style et un certain classicisme, bref de lancer l’idée d’un modernisme anti-moderne (Volker Weiss). Moeller s’intéresse dès lors aux travaux d’architecture et d’urbanisme de Peter Behrens (1868-1940; photo), un homme de sa génération. Behrens est le précurseur de la “sachliche Architektur”, de l’architecture objective, réaliste. Il est aussi, pour une large part, le père du “design” moderne. Pas un objet contemporain n’échappe à son influence. Behrens donne un style épuré et sobre aux objets nouveaux, exigeant des formes nouvelles, qui meublent désormais les habitations dans les sociétés hautement industrialisées, y compris celles des foyers les plus modestes, auparavant sourds à toute esthétique (cf. H. van de Velde).

Quand la Grande Guerre se déclenche, Moeller est en train de rédiger “Der preussische Stil”, retour à l’architecture des Gilly, Schinckel et von Klenze mais aussi réflexions générales sur la germanité qui, pour trouver cette unité intérieure recherchée tout au long des huit volumes de “Die Deutschen”, doit opérer un retour à l’austérité dorienne du classicisme prussien et abandonner certaines fantaisies ou ornements prisés lors des décennies précédentes: même constat chez l’ensemble des architectes, qui abandonnent la luxuriance du Jugendstil pour une “Sachlichkeit” plus sobre. La réhabilitation du “style prussien” implique aussi l’abandon de ses anciennes postures de dandy, une exaltation des vertus familiales prussiennes, de la sobriété, de la “Kargheit”, etc. Le livre “Der preussische Stil” sera achevé pendant la guerre, sous l’uniforme. Il s’inscrit dans la volonté de promouvoir des formes nouvelles, tout en gardant un certain style et un certain classicisme, bref de lancer l’idée d’un modernisme anti-moderne (Volker Weiss). Moeller s’intéresse dès lors aux travaux d’architecture et d’urbanisme de Peter Behrens (1868-1940; photo), un homme de sa génération. Behrens est le précurseur de la “sachliche Architektur”, de l’architecture objective, réaliste. Il est aussi, pour une large part, le père du “design” moderne. Pas un objet contemporain n’échappe à son influence. Behrens donne un style épuré et sobre aux objets nouveaux, exigeant des formes nouvelles, qui meublent désormais les habitations dans les sociétés hautement industrialisées, y compris celles des foyers les plus modestes, auparavant sourds à toute esthétique (cf. H. van de Velde).

Le style préconisé par Behrens, pour les objets nouveaux, n’est pas chargé, floral ou végétal, comme le voulait l’Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) mais très dénué d’ornements, un peu à la manière futuriste, le groupe futuriste italien autour de Marinetti ayant appelé, avec virulence, à rejeter toutes les ornementations inutiles prisées par l’académisme dominant. On trouve encore dans nos magasins, aujourd’hui, bon nombre de théières, de couverts, de téléphones, d’horloges ou de pièces de vaisselle qui proviennent en droite ligne des ateliers de Behrens, avec très peu de changements. Le mouvement d’art et de design, lancé par Behrens, s’organise au sein du “Deutscher Werkbund”, où oeuvrent également des célébrités comme Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe ou Le Corbusier. Le “Werkbund” travaille pour l’AEG (“Allgemeine Elektrische Gesellschaft”), qui produit des lampes, des appareils électro-ménagers à diffuser dans un public de plus en plus vaste. Le “Werkbund” préconise par ailleurs une architecture monumentale, dont les fleurons seront des usines, des écoles, des ministères et l’ambassade allemande à Saint-Pétersbourg. Pour Moeller, Behrens trouve le style qui convient à l’époque: le lien est encore évident avec le classicisme prussien, il n’y a pas rupture traumatisante, mais le résultat final est “autre chose”, ce n’est pas une répétition pure et simple.

Le style préconisé par Behrens, pour les objets nouveaux, n’est pas chargé, floral ou végétal, comme le voulait l’Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) mais très dénué d’ornements, un peu à la manière futuriste, le groupe futuriste italien autour de Marinetti ayant appelé, avec virulence, à rejeter toutes les ornementations inutiles prisées par l’académisme dominant. On trouve encore dans nos magasins, aujourd’hui, bon nombre de théières, de couverts, de téléphones, d’horloges ou de pièces de vaisselle qui proviennent en droite ligne des ateliers de Behrens, avec très peu de changements. Le mouvement d’art et de design, lancé par Behrens, s’organise au sein du “Deutscher Werkbund”, où oeuvrent également des célébrités comme Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe ou Le Corbusier. Le “Werkbund” travaille pour l’AEG (“Allgemeine Elektrische Gesellschaft”), qui produit des lampes, des appareils électro-ménagers à diffuser dans un public de plus en plus vaste. Le “Werkbund” préconise par ailleurs une architecture monumentale, dont les fleurons seront des usines, des écoles, des ministères et l’ambassade allemande à Saint-Pétersbourg. Pour Moeller, Behrens trouve le style qui convient à l’époque: le lien est encore évident avec le classicisme prussien, il n’y a pas rupture traumatisante, mais le résultat final est “autre chose”, ce n’est pas une répétition pure et simple.

Henry van de Velde

Après 1918, la recherche d’un style bien particulier, d’une architecture majestueuse, monumentale et prestigieuse n’est, hélas, plus de mise: il faut bâtir moins cher et plus vite, l’art spécifique du “Deutscher Werkbund” glisse rapidement vers la “Neue Sachlichkeit”, où excelleront des architectes comme Gropius et Mies van der Rohe. L’évolution de l’architecture allemande est typique de cette époque qui part de l’Art Nouveau (Jugendstil), avec ses ornements et ses courbes, pour évoluer vers un abandon progressif de ces ornements et se rapprocher de l’austérité vitruvienne du classicisme prussien du début du 19ème, sans toutefois aller aussi loin que la “neue Sachlichkeit” des années 20 dans le rejet de toute ornementation. L’architecte Paul Schulze-Naumburg , qui adhèrera au national-socialisme, polémique contre la “Neue Sachlichkeit” en l’accusant de verser dans la “Formlosigkeit”, dans l’absence de toute forme. Dans cette effervescence, on retrouve l’oeuvre de Henry van de Velde (1863-1957), partie, elle aussi, du pré-raphaëlisme anglais, des idées de John Ruskin (dont Hedda Maase avait traduit les livres), de William Morris, etc. Fortement influencé par sa lecture de Nietzsche, van de Velde tente de traduire la volonté esthétisante et rénovatrice du penseur de Sils-Maria en participant aux travaux du Werkbund, notamment dans les ateliers de “design” et dans la “colonie des artistes” de Darmstadt, avant 1914. Revenu en Belgique peu avant la seconde guerre mondiale, il accepte de travailler au sein d’une commission pour la restauration du patrimoine architectural bruxellois pendant les années de la deuxième occupation allemande: il tombe en disgrâce suite aux cabales de collègues jaloux et médiocres qui saccageront la ville dans les années 50 et 60, tant et si bien qu’on parlera de “bruxellisation” dans le jargon des architectes pour désigner la destruction inconsidérée d’un patrimoine urbanistique. Le procès concocté contre lui n’aboutit à rien, mais van de Velde, meurtri et furieux, quitte le pays définitivement, se retire en Suisse où il meurt en 1957.

Les figures de Peter Behrens, Henry van de Velde et Paul Schulze-Naumburg méritent d’être évoquées, et situées dans le contexte de leur époque, pour montrer que les thèmes de l’architecture, de l’urbanisme et des formes du “design” participent, chez Moeller van den Bruck, à l’élaboration du “style” jungkonservativ qu’il contribuera à forger. Ce style n’est pas marginal, n’est pas l’invention de quelques individus isolés ou de petites phalanges virulentes et réduites mais constitue bel et bien une synthèse concise des innovations les plus insignes des trois premières décennies du 20ème siècle. La quête de Moeller van den Bruck est une quête de formes et de style, de forme pour un peuple enfin devenu conscient de sa force politique potentielle, équivalente en grandeur à ses capacités culturelles, pour un peuple devenu enfin capable de bâtir un “Troisième Règne” de l’esprit, au sens où l’entendait le filon philosophique, théologique et téléologique partant de Joachim de Flore pour aboutir à Dmitri Merejkovski.

La guerre au “Département de propagande”

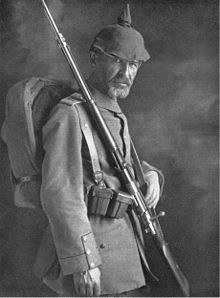

Pendant que Moeller rédigeait la première partie de “Der preussische Stil”, l’Allemagne et l’Europe s’enfoncent dans la guerre immobile des tranchées. Le réserviste Moeller est mobilisé dans le “Landsturm”, à 38 ans, vu sa santé fragile, la réserve n’accueillant les hommes pleinement valides qu’à partir de 39 ans. Il est affecté au Ministère de la guerre, dans le département de la propagande et de l’information, l’“Auslandsabteilung”, ou le “MAA” (“Militärische Stelle des Auswärtigen Amtes”), tous deux chargés de contrer la propagande alliée. En ce domaine, les Allemands se débrouillent d’ailleurs très mal: ils publient à l’intention des neutres, Néerlandais, Suisses et Scandinaves, de gros pavés bien charpentés sur le plan intellectuel mais illisibles pour le commun des mortels: à l’ère des masses, cela s’appelle tout bonnement rater le coche. Cette propagande n’a donc aucun impact. Dans ce département, Moeller rencontre Max Hildebert Boehm, Waldemar Bonsels, Herbert Eulenberg (le nouveau mari de sa première femme), Hans Grimm, Friedrich Gundolf et Börries von Münchhausen. Tous ces hommes constitueront la base active qui militera après guerre, dans une Allemagne vaincue, celle de la République de Weimar, pour restaurer l’autonomie du politique et la souveraineté du pays.

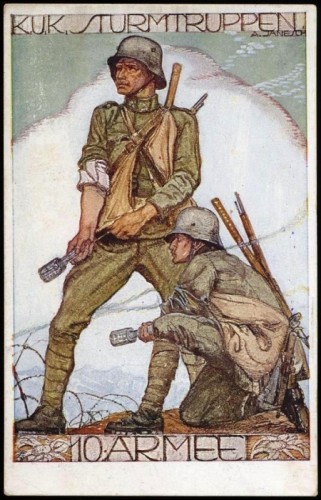

Dans le double cadre de l’“Auslandsabteilung” et du MAA, Moeller rédige “Belgier und Balten” (= “Des Belges et des Baltes”), un appel aux habitants de Belgique et des Pays Baltes à se joindre à une vaste communauté économique et culturelle, dont le centre géographique serait l’Allemagne. Il amorce aussi la rédaction de “Das Recht der jungen Völker” (= “Le droit des peuples jeunes”), qui ne paraîtra qu’après l’armistice de novembre 1918. Le terme “jeune” désigne ici la force vitale, dont bénéficient encore ces peuples, et la “proximité du chaos”, un chaos originel encore récent dans leur histoire, un chaos bouillonnant qui sous-tend leur identité et duquel ils puisent une énergie dont ne disposent plus les peuples vieillis et éloignés de ce chaos. Pour Moeller, ces peuples jeunes sont les Japonais, les Allemands (à condition qu’ils soient “prussianisés”), les Russes, les Italiens, les Bulgares, les Finlandais et les Américains. “Das Recht der jungen Völker” se voulait le pendant allemand des Quatorze Points du président américain Woodrow Wilson. Le programme de ce dernier est arrivé avant la réponse de Moeller qui, du coup, n’apparait que comme une réponse tardive, et même tard-venue, aux Quatorze Points. Moeller prend Wilson au mot: ce dernier prétend n’avoir rien contre l’Allemagne, rien contre aucun peuple en tant que peuple, n’énoncer qu’un programme de paix durable mais tolère —contradiction!— la mutilation du territoire allemand (et de la partie germanique de l’empire austro-hongrois). Les Allemands d’Alsace, de Lorraine thioise, des Sudètes et de l’Egerland, de la Haute-Silésie et des cantons d’Eupen-Malmédy n’ont plus le droit, pourtant préconisé par Wilson, de vivre dans un Etat ne comprenant que des citoyens de même nationalité qu’eux, et doivent accepter une existence aléatoire de minoritaires au sein d’Etats quantitativement tchèque, français, polonais ou belge. Ensuite, Wilson, champion des “droits de l’homme” ante litteram, ne souffle mot sur le blocus que la marine britannique impose à l’Allemagne, provoquant la mort de près d’un million d’enfants dans les deux ou trois années qui ont suivi la guerre.

La transition “jungkonservative”

L’engagement politique “jeune-conservateur” est donc la continuation du travail patriotique et nationaliste amorcé pendant la guerre, en service commandé. Pour Moeller, cette donne nouvelle constitue une rupture avec le monde purement littéraire qu’il avait fréquenté jusqu’alors. Cependant l’attitude “jungkonservative”, dans ce qu’elle a de spécifique, dans ce qu’elle a de “jeune”, donc de dynamique et de vectrice de “transition”, est incompréhensible si l’on ne prend pas acte des étapes antérieures de son itinéraire de “littérateur” et de l’ambiance prospective de ces bohèmes littéraires berlinoises, munichoises ou parisiennes d’avant 1914. Le “Jungkonservativismus” politisé est un avatar épuré de la grande volonté de transformation qui a animé la Belle Epoque. Et cette grande volonté de transformation n’était nullement “autoritaire” (au sens où l’Ecole de Francfort entend ce terme depuis 1945), passéiste ou anti-démocratique. Ces accusations récurrentes, véritables ritournelles de la pensée dominante, ne proviennent pas d’une analyse factuelle de la situation mais découlent en droite ligne des “vérités de propagande” façonnées dans les officines françaises, anglaises ou américaines pendant la première guerre mondiale. L’Allemagne wilhelminienne, au contraire, était plus socialiste et plus avant-gardiste que les puissances occidentales, qui prétendent encore et toujours incarner seules la “démocratie” (depuis le paléolithique supérieur!). Les mésaventures judiciaires du cabaretier Wedekind, et la mansuétude relative des tribunaux chargés de le juger, pour crime de lèse-majesté ou pour offense aux bonnes moeurs, indique un degré de tolérance bien plus élevé que celui qui règnait aileurs en Europe à l’époque et que celui que nous connaissons aujourd’hui, où la liberté d’opinion est de plus en plus bafouée. Mieux, le sort des homosexuels, qui préoccupe tant certains de nos contemporains, était enviable dans l’Allemagne wilhelminienne, qui, contrairement à la plupart des “démocraties” occidentales, ne pratiquait, à leur égard, aucune forme d’intolérance. Cet état de choses explique notamment le tropisme germanophile d’un écrivain flamand (et homosexuel) de langue française, Georges Eeckoud, par ailleurs pourfendeur de la mentalité marchande d’Anvers, baptisée la “nouvelle Carthage”, pour les besoins de la polémique.

“Montagstische”, “Der Ring”

Les anciens du MAA et des autres bureaux de (mauvaise) contre-propagande allemande se réunissent, après novembre 1918, lors des “Montagstische”, des “tables du lundi”, rencontres informelles qui se systématiseront au sein d’un groupe nommé “Der Ring” (= “L’Anneau”), où l’on remarquait surtout la présence de Hans Grimm, futur auteur d’un livre à grand succès “Volk ohne Raum” (“Peuple sans espace”). Les initiatives post bellum vont se multiplier. Elles ont connu un précédent politique, la “Vereinigung für nationale und soziale Solidarität” (= “Association pour la solidarité nationale et sociale”), émanation des syndicats solidaristes chrétiens (surtout catholiques) plus ou moins inféodés au Zentrum. Le chef de file de ces “Solidarier” (“solidaristes”) est le Baron Heinrich von Gleichen-Russwurm (1882-1959), personnalité assez modérée à cette époque-là, qui souhaitait d’abord un modus vivendi avec les puissances occidentales, désir qui n’a pu se concrétiser, vu le blocus des ports de la Mer du Nord qu’ont imposé les Britanniques, pendant de longs mois après la cessation des hostilités. Heinrich von Gleichen-Russwurm réunit, au sein du “Ring”, une vingtaine de membres, tous éminents et désireux de sauver l’Allemagne du naufrage consécutif de la défaite militaire. Parmi eux, l’Alsacien Eduard Stadtler et le géopolitologue Adolf Grabowski (qui restera actif longtemps, même après la seconde guerre mondiale).

Eduard Stadtler