Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) has had a tremendous influence on the modern world, not only in the history of ideas, but in the political realm as well. How big an influence? Without Hegel, there would have been no Marx; without Marx, no Lenin, no Mao, no Castro, no Pol Pot. Now, reflect just a moment on the difference the Communism has made in the modern world, even in non-Communist countries, whose policies were deeply motivated by the desire to defeat Communism.

Communism is without a doubt the most important and influential, not to mention deadly, political innovation in the 20th century; and, before Marx, some of its intellectual foundations were laid by Hegel. I should add, however, that Hegel would have rejected Marxism and thus cannot be held responsible for the lesser minds influenced by him; furthermore, not all aspects of his cultural and political legacy are so negative; and, rightly understood, Hegel has the potential to exercise an immensely positive influence on modern politics and culture.

Outwardly, Hegel did not live a particularly interesting life. He was born in 1770 in Stuttgart, to an educated, middle-class family of lawyers, civil servants, and Lutheran pastors. He was educated at the University of Tübingen, first as a seminarian. He shared rooms with Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and Friedrich Hölderlin, who also made huge contributions to German philosophy and letters. Having completed the equivalent of a Ph.D. in philosophy, he held a series of tutoring positions, collaborated on a couple of journals, inherited and spent his patrimony, and found himself broke and approaching his middle thirties.

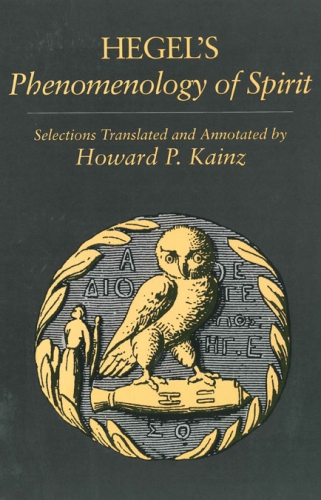

Salvation came in the form of a book contract with a healthy advance but a draconian penalty for lateness. Hegel started writing . . . and writing . . . and writing. His outlined work got out of hand; each chapter became bigger than the last, and Hegel found himself dangerously close to his deadline, writing feverishly to finish his work, when outside the city where he resided, Napoleon fought and defeated the Prussian army at the Battle of Jena. In the midst of chaos, as French troops were occupying the city, Hegel bundled up the only copy of his manuscript and put it in the mail. It reached the publisher, and the next year, in 1807, Hegel’s most celebrated work, Phenomenology of Spirit, was published.

Phenomenology of Spirit is one of the classic works of German idealism: more than 500 prolix, rambling, tortured, and mind-bogglingly obscure pages. My copy is covered with dents from the times I hurled it against the wall or floor in frustration. Hegel is, without a doubt, the worst stylist in the history of philosophy. Unlike Kant, who could write well when he wanted to but often chose not to, Hegel could not write a clear sentence to save his life. Heinrich Heine reports that on his deathbed, Hegel is said to have sighed, “Only one man has understood me.” But then, a few minutes later, he added fretfully, “And even he did not understand me.” Never has so much been misunderstood by so many.

Phenomenology of Spirit laid the foundations for Hegel’s philosophical system and for his academic career and reputation, but it was only after 10 years that he received an academic position. For the rest of his life he lectured, he wrote, and he published. And then, in 1831, he died. Now, at this point, with any other author’s story, I would conclude by saying, “and the rest is history.” But in Hegel’s case, it is not so simple.

Phenomenology of Spirit

Given its formidable difficulties, why would anyone trouble read a book like Phenomenology of Spirit? Because, if Hegel is right, then world history comes to an end with the writing of his book. Specifically, Hegel held that the battle of Jena brought world history to an end in the concrete realm because it was the turning point in the battle between the principles of the French revolution—liberty, equality, fraternity, secularism, and progress—and the principles of traditional absolutism, the so-called throne-altar alliance.

Given its formidable difficulties, why would anyone trouble read a book like Phenomenology of Spirit? Because, if Hegel is right, then world history comes to an end with the writing of his book. Specifically, Hegel held that the battle of Jena brought world history to an end in the concrete realm because it was the turning point in the battle between the principles of the French revolution—liberty, equality, fraternity, secularism, and progress—and the principles of traditional absolutism, the so-called throne-altar alliance.

Napoleon was, for Hegel, the World Spirit made incarnate, on a horse. Napoleon did not, however, understand his significance. But Hegel did. And when Hegel understood the world historical significance of the principles of the French Revolution and their military avatar, Napoleon, and wrote it down in Phenomenology of Spirit, he believed that the underlying purpose of history had been fulfilled. Just as Christ was the incarnation of the divine logos, so is the historical world—and the book—brought about by the French Revolution the incarnation of the logos of human history, and Hegel and Napoleon played the role of the Holy Spirit, mediating the two, making the ideal (the concept) concrete.

Now, at first glance—and maybe at second glance—all of this must seem quite mad. There is more madness to come. But I think that if your experience is like mine, you will find that these claims, which initially seem so mad, have a certain method to them, and even a logic. Hegel and his most able and charismatic expositor Alexandre Kojève exercise a strange fascination, which I hope you will come to share. If they were mad, then I hope to convince you that they had cases of divine madness.

What is “History”?

The main reason for reading Hegel is that he provides deep insights into the philosophy of history and culture. But what does Hegel mean by “history”? If history is something that can come to an end through a battle and a book, then Hegel must have a very specific—and very peculiar—conception of history in mind. This is true.

History, for Hegel, is the history of fundamental ideas, basic interpretations of human existence, interpretations of mankind and our place in the cosmos; basic “horizons” or “worldviews.” History for Hegel is equivalent to what Heidegger calls the “History of Being”—“Being” being understood here as fundamental and hegemonic worldviews. For uniformity’s sake, I shall say that Hegelian history is the history of “fundamental interpretations of human existence.” When these interpretations are explicitly articulated in abstract terms, they are what we call philosophies.

But it would be a mistake to think of these fundamental interpretations of human existence merely as abstract philosophical positions. They can also be found in less-abstract articulations, such as myth, religion, poetry, and literature. And they can be concretely embodied: in the form of art and architecture and all other cultural productions, as well as in social and political institutions and practices.

Indeed, Hegel holds that these fundamental interpretations of existence exist for the most part in concrete, rather than abstract form. They exist as “tacit” presuppositions embedded in language, myth, religion, custom, etc. Although these can be articulated at least in part, they need not be and seldom fully are. These fundamental interpretations of existence are what Nietzsche calls “horizons”: unspoken, unarticulated, unreflective attitudes and values that constitute the bounding parameters and vital force of a culture.

History for Hegel does include more concrete and mundane historical facts and events, but only insofar as these embody fundamental interpretations of human existence—and there are few things in the world that do not embody such interpretations. Even the stars, which would seem to fall into the realms of natural science and natural history, fall into human history and the human world, insofar as they are construed from the point of view of the earth, and through the lenses of different myths and cultures, as constellations, portents, or even gods. Indeed, since all of the sciences are themselves human activities, and the sciences interpret all of nature, all of nature falls within the human world.

The “Human World”: Idea, Spirit

I have been using the expression “the human world.” What does this expression mean? The human world means the world of nature as interpreted by human reason and as transformed by human work. The human world comes into being when men appropriate nature, when we make it our own by endowing it with meaning and/or transforming it through work, thereby integrating it into the web of human concerns, human purposes, and human projects.

This process can be quite simple. A rock in your driveway is simply a chunk of nature. But it can be brought into the human world by endowing it with a purpose. One can use it as a paperweight; or one can use it as an example in a lecture. By doing this, I have appropriated the rock, lifting it out of the natural world, where it has no purpose and no meaning, and bringing it into the human world, where it has purpose and meaning.

Hegel’s primary concern as a philosopher is with the human world. Now, Hegel is known as an “idealist.” Idealism is generally held to be a thesis that the world is made of “idea stuff.” And “idea stuff” is supposed to be something ghostly, numinous, immaterial, mental. Does this mean that Hegel held that the human world was somehow numinous and abstract?

No, Hegel is not that kind of idealist. Hegel has a very peculiar way of using the world “idea” (Idee). When Hegel talks about ghostly, immaterial abstract mental “ideas” he uses the German word “Begriff,” which is well-translated “concept.” And concepts are distinct from, though related to Ideas. Hegel’s understanding of the distinctness and the relatedness of concepts and Ideas can be expressed by the following equation:

Concept + Concrete = Idea

Ideas for Hegel are not abstract and numinous, because the Hegelian Idea consists of chunks of solid, concrete reality interpreted, worked over, and otherwise transformed in the light of concepts. Or, conversely formulated, the Hegelian Idea consists of concepts that have been concretely realized in reality, whether by deploying concepts merely to interpret reality or as blueprints for transforming it. The Hegelian Idea is identical to the human world, and the human world is the world of concrete natural objects interpreted and transformed by human beings.

Another term that Hegel uses as equivalent to Idea is “Spirit.” Again, this word has an abstract and numinous connotation, but not for Hegel. For Hegel, Spirit and Ideas can be as solid and concrete as a rock, so long as the rock has been transformed in light of human concepts. So the aforementioned rock/paperweight is a chunk of Spirit, a chunk of Idea. History proper is not, however, the history of mundane concepts, mundane Ideas, and humble chunks of Spirit like a paperweight. History is the history of fundamental concepts, fundamental Ideas: fundamental interpretations of human existence, both as abstractly articulated and as concretely embodied.

To sum up:

The Human World = Spirit = Idea = Concepts + Concretes

History as Dialectic

Hegel claims that all fundamental interpretations of human existence that fall within history are partial and inadequate interpretations, which are relative to time, place, and culture. This is the position known as “historicism”; it is the source of the commonplace assertion that a person or a cultural production is a creature or product of a particular time and culture.

Since there is a plurality of distinct and different times, places, and cultures, there is also a plurality of distinct and different fundamental interpretations of human existence. The existence of a plurality of different interpretations of human existence on the finite surface of a globe means that eventually these different interpretations and the cultures that concretize them will come into contact—and, inevitably, into conflict—with one another.

History is the record of these confrontations and conflicts between different worldviews. It follows, then, that the logical structure of history is identical with the logical structure of the conflict of different worldviews. The logical structure of the conflict of different worldviews is called “dialectic.” History, therefore, has a dialectical structure.

Dialectic is the logic of conversation. It is the process whereby partial and inadequate perspectives work for mutual communication and intelligibility, thereby creating a broader, more-encompassing and adequate perspective.

Dialectic is the process whereby different individual or cultural perspectives, with all of their idiosyncrasies, work their way toward a more encompassing common perspective.

Dialectic is the process wherein largely tacit cultural horizons—myth, religion, language, institutions, traditions, customs, prejudices—are progressively articulated and criticized, casting aside the irrational, idiosyncratic, parochial, and adventitious in favor of the universal, rational, and fully self-conscious.

What drives the process forward is the search for an interpretation of human existence that is adequate to our nature. It is the search for a true understanding of human existence. And this presupposes that human beings have a fundamental need for a correct understanding of themselves and their world, a need which drives the dialectic forward.

Now, since fundamental interpretations of human existence take the form not merely of abstract theories, but concrete institutions, practices, cultures, and ways of life, the dialectic between these worldviews is not carried on merely in seminars, symposia, and coffee houses. It is carried on in the concrete realm as well in the form of the struggles between different political parties, interest groups, institutions, social classes, generations, cultures, forms of government, and ways of life, insofar as these embody different conceptions of human existence. The struggle is carried on in the form of peaceful rivalries and social evolution—and in the form of bloody wars and revolutions—and in the form of the conquest and annihilation or assimilation of one culture by another.

Absolute Idea, Absolute Spirit, and the End of History

If all fundamental interpretations of human existence in history are partial, inadequate, and relative to particular times and cultures, this implies that if and when we arrive at an interpretation of human existence that is comprehensive and true, then we have somehow stepped outside of history. If history is the history of fundamental ideological struggle, then history ends when all fundamental issues have been decided.

In the abstract realm, the realm of concepts, the end of history comes about when a final, true, and all-encompassing interpretation of human existence is articulated. This interpretation, unlike all the others that came before it, is not partial or relative but Absolute Truth, the Absolute Concept. It is important to note that the Absolute Truth, unlike all previous partial and relative truths, does achieve a wholly articulated form; it is not a merely tacit and unarticulated cultural horizon; it is fully articulated, all-encompassing system of ideas.

However, just because the absolute truth is wholly articulated in abstract terms, that does not imply that it exists in the abstract realm only. The Absolute Concept is also realized in the concrete realm as well. In the concrete realm, Absolute Truth is realized at the end of history in the form of a universal, and in all important respects, homogeneous, world civilization.

This does not necessarily mean a world government. Distinct nations may remain, but only insofar as their existence is fundamentally unimportant. For in all important things—that is, in all issues relating to the correct interpretation of human nature and our place in the world—uniformity reigns. Hegel calls the post-historical world in which the Absolute Truth is concretely realized “Absolute Idea” and “Absolute Spirit.”

Hegel does not hold that Absolute Truth and Absolute Spirit are mere possibilities, the speculations of an agile and perhaps fevered mind. He holds that they are already actual. The Absolute Truth is to be found—where else?—in Hegel’s writings. Specifically, it is to be found in his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences. The Phenomenology of Spirit is only a ladder leading up to Absolute Truth, proving that it is and what it must be like, but giving no specifics. And, as we have seen, Hegel holds that ideological history comes to an end with the ideals of the French Revolution: the universal rights of man; liberty, equality, and fraternity; secularism and scientific and technological progress.

The fundamentally scientific and technological character of Absolute Spirit/Idea cannot be stressed enough. A particular chunk of Idea/Spirit equals a chunk of nature, of given reality, transformed by human discourse and/or human work. Absolute Idea/Spirit therefore equals the totality of nature transformed by human discourse and work, i.e., by science and technology.

Now, this is not to say that Absolute Spirit comes into being only after the entire universe has been scientifically understood and technologically appropriated and transformed, for this is an infinite task. Rather, Absolute Spirit comes into being by setting up the infinite task of understanding and transforming nature; Absolute Spirit consists of a way of framing nature as, in principle, infinitely knowable by science and, in principle, infinitely malleable by technology. All limitations encountered in the unfolding of this infinite task are encountered as merely temporary impediments what can always, in principle, be overcome by better science and better technology. Hegel, like all the other great philosophers of modernity, is a good Baconian.

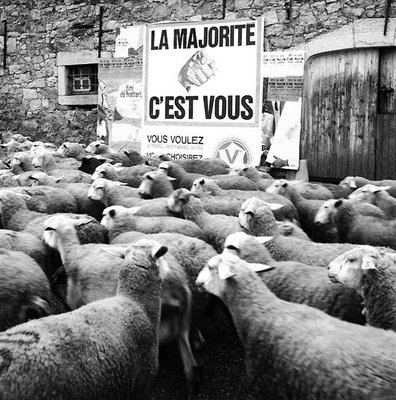

The end of history does not mean the end of history in the more mundane sense. The newspaper will still come in the morning, but it will look more like the Atlanta Journal than the New York Times: a global village tattler, chronicling untold billions of treed cats, weddings, funerals, garage sales, and church outings, bulging with untold billions of pizza coupons. Remember: the end of history means the end of ideological history. It means that no ideological and political innovations are possible, that there are no causes worth killing or dying for anymore, that we fully understand ourselves.

The end of history is a technocrat’s dream: now that the basic intellectual and political parameters of human existence have been fixed once and for all, we can get on with the business of living: the infinite task of the mastery and possession of nature; the infinite play made possible by an endless stream of new toys.

The Question of Historicism

It is often said that Hegel holds that human nature itself is relative to particular times, places, and cultures, and that as history changes, so does human nature. This strikes me as false. It is man’s nature to be historical, but this fact is not itself a historical fact. It is a natural fact that makes history possible. It is natural in the sense that it is a fixed and permanent necessity of our natures, which founds and bounds the realm of human action, history, and culture. Different interpretations of human nature are relative to different times, places, and cultures; different worldviews change and succeed one another in time.

Absolute Truth = a true self-interpretation of man = a final account of human nature. If such an account is not possible, because a fixed human nature does not exist, then Hegel could never hold that history comes to an end. There will be merely an endless progression of merely relative human self-interpretations, none of which can claim any greater adequacy than any other, because of course there is nothing for them to be adequate to. For Hegel, man gains knowledge of his nature through history. But he does not gain his nature itself through history.

Kojève

Hegel claims that the end of history would be wholly satisfying to man. But is it? This brings us to Alexandre Vladimirovich Kojevnikoff (1902–1968), known simply as “Kojève.” Kojève was the 20th century’s greatest, and most influential, interpreter and advocate of Hegel’s philosophy of history. Kojève’s Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit [4] has its errors; it has its obscurities, eccentricities, and ticks. But it is still the most profound, accessible, and exciting introduction to Hegel in existence.

has its errors; it has its obscurities, eccentricities, and ticks. But it is still the most profound, accessible, and exciting introduction to Hegel in existence.

Kojève in 1922

Ironically, though, by stating Hegel clearly and radically, Kojève has pushed Hegel to the breaking point, forcing us to confront the question: Is Hegel’s end of history really the end of history? And if it is, can it really claim to be fully satisfying to man?

Kojève was born in Moscow in 1902 to a wealthy bourgeois family, which, when the communists took over in 1917, was subjected to the indignities one would expect. Kojève was reduced to selling black market soap. He was arrested and narrowly escaped being shot. In a paradox that has called his sanity into question in the minds of many, he left prison a convinced communist. In 1919, he left Russia with the family jewels, which he cashed in for a small fortune in Berlin. (He might be called a limousine communist.)

He studied philosophy in Heidelberg with Karl Jaspers and wrote a doctoral dissertation on Vladimir Solovieff, a Russian philosopher and mystic. In the late 1920s, he moved to Paris. His fortune was wiped out by the Great Depression, and he was reduced to severely straightened circumstances. Fortunately, during the 1920s, Kojève had met and befriended Alexandre Koyré, a historian of philosophy and a fellow Russian émigré, who arranged for Kojève to take over his seminar on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit at the École pratique des hautes études.

Kojève taught this seminar from 1933 to 1939. Although the seminar was very small, it had a tremendous influence on French intellectual life, for its students included such eminent philosophers and scholars as Jacques Lacan, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georges Bataille, Raymond Queneau, Raymond Aron, Gaston Fessard, and Henri Corbin. Through his students, Kojève influenced Sartre, as well as subsequent generation of leading French thinkers, who are known as “postmodernists,” including Foucault, Deleuze, Lyotard, and Derrida—all of whom felt it necessary to define their positions in accordance with or in opposition to Hegel as portrayed by Kojève.

Kojève taught this seminar from 1933 to 1939. Although the seminar was very small, it had a tremendous influence on French intellectual life, for its students included such eminent philosophers and scholars as Jacques Lacan, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georges Bataille, Raymond Queneau, Raymond Aron, Gaston Fessard, and Henri Corbin. Through his students, Kojève influenced Sartre, as well as subsequent generation of leading French thinkers, who are known as “postmodernists,” including Foucault, Deleuze, Lyotard, and Derrida—all of whom felt it necessary to define their positions in accordance with or in opposition to Hegel as portrayed by Kojève.

I am convinced that it is impossible to understand the peculiar vehemence with which many French postmodernists abuse such concepts as modernity and metaphysics until one sees that these refer ultimately to Kojève’s reading of Hegel. And this brings us to another reason for reading Hegel and Kojève: It is an ideal tool for understanding French postmodernism, a tremendously influential school of thought. Indeed, it seem that on some academic presses now, every third book contains “postmodern” or one of its cognates in its title.

Kojève’s seminar came to an end in 1939, when World War II broke out. During the German occupation, Kojève joined the French resistance. Or so he said. After the war it was hard to find someone who didn’t claim to have joined the resistance.

After the war, Kojève did not return to academia. Instead, one of his students from the 1930s, Robert Marjolin, got him a job in the French Ministry of Economic affairs, where he worked until his death in 1968. Through his position at the ministry, Kojève exercised almost as great an influence as De Gaulle on the creation of the post-war European economic order. He was the architect of GATT and was instrumental in setting up the European Economic Community. He was also quite prescient in predicting a number of political, economic, and cultural trends. For instance, in the 1950s he was already confident that the West would win the Cold War. He also offers profound diagnoses of the logic of contemporary culture’s obsession with senseless violence and cruelty. Finally, in the late 1950s he glimpsed the logic of Japan’s rising power. Up until his death in 1968, Kojève was a trusted advisor to a number of French politicians, mostly on the right, all the while puzzling his friends by maintaining that he was still an ardent Stalinist. He even bought a house on the Boulevard Stalingrad.

Kojève was fully convinced that history had come to an end in 1806 with the battle of Jena. Accordingly, he held that nothing of any fundamental historical importance had happened since then: not the First World War, not the Second World War, not the Russian and Chinese revolutions. All of these were, in Kojève’s eyes, simply petty squabbles about the implementation of the principles of the French revolution. Even the Nazis were regarded by Kojève as simply history’s way of bringing democracy to Imperial Germany.

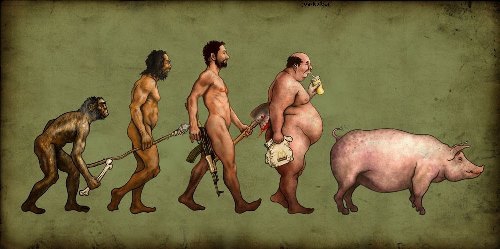

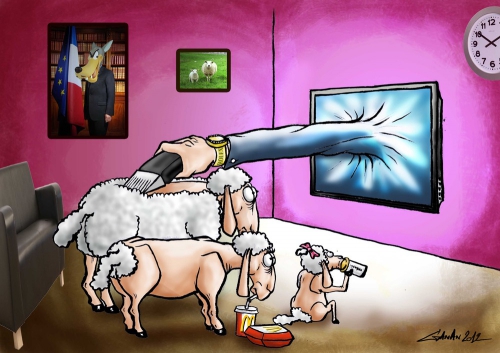

Kojève was not, however, convinced that the end of history would mean the complete satisfaction of man. Indeed, he thought that it would spell the abolition of mankind. This does not mean that Kojève thought that human beings would become extinct. He simply thought that what makes us humans, as opposed to contented animals, would be abolished at the end of history.

Kojève held that it was the capacity to engage in struggle over fundamental interpretations of human existence—the struggle for self-understanding—that set us apart from the beasts. Once these struggles are ended, that which sets us apart from the beasts disappears. The end of history would satisfy our animal natures, our desires, but it would offer nothing to satisfy our particularly human desires.

Kojève does not, however, argue that everyone is reduced to a beast at the end of history. Traditionally, human beings have regarded themselves as occupying the space between beasts and gods on the totem pole. When one loses one’s humanity, one can do so either by becoming a beast or by becoming a god.

Kojève held that most human beings at the end of history would be reduced to beasts. But some would become gods. How? By becoming wise. At the end of history, the correct and final interpretation of human existence, the Absolute Truth, has been articulated as a system of science by Hegel himself. This system is the wisdom that philosophy has pursued for more than 2,000 years.

Kojève held that most human beings at the end of history would be reduced to beasts. But some would become gods. How? By becoming wise. At the end of history, the correct and final interpretation of human existence, the Absolute Truth, has been articulated as a system of science by Hegel himself. This system is the wisdom that philosophy has pursued for more than 2,000 years.

Philosophy is the pursuit of wisdom, not the possession of wisdom. Hegel, by possessing wisdom, is no longer a philosopher; Hegel is a wise man. In putting the period on history, Hegel brings philosophy to an end as well.

A post-historical god takes up a critical distance from the end of history. He does not live post-historical life. He tries to understand it: how we got here, what is happening, and where we are going — all things we can learn from Hegel and Kojève. If dehumanization is our destiny, at least we can try to become gods, which is reason enough to read Hegel.

La testimonianza archeologica che più può essere d’aiuto per comprendere il complesso sistema iniziatico del culto di Mithra è sicuramente il mosaico pavimentale presente nel mitreo di Felicissimo ad Ostia, denominato Scala delle Sette Porte. Sia Celso sia Porfirio ci parlano di un’iniziazone con sette diversi e gerarchici gradi di conoscenza e, come rappresentato nelle sette porte di Ostia, ognuno rappresentato dall’animale simbolico e dall’Astro/Nume di riferimento. Il primo grado è rappresentato dal Corax (Corvo), egli è la base del culto mithriaco, il neofita che affronta le prime prove di umiltà, di controllo dell’ego, di mantenimento del segreto. Simboleggiato appunto da un corvo, è il messaggero degli Dei che risvegliano Mithra, avendo in Hermes-Mercurio la propria divinità tutelare. Il risveglio è l’inizio della rettificazione del myste, il risveglio della propria essenza solare: ogni rettificazione la si può riconnettere ai centri di luce, chakra nella tradizione indù o sephira in quella cabalistica, lungo il canale verticale che corre lungo la colonna vertebrale, espressione proprio di un Caduceo Ermetico che ritroviamo tra i simboli di Hermes e del Corax, ove si intrecciano le energie lunari e solari, mercuriali e sulfuree, lungo quello che viene denominato il “canale di Brahma”.

La testimonianza archeologica che più può essere d’aiuto per comprendere il complesso sistema iniziatico del culto di Mithra è sicuramente il mosaico pavimentale presente nel mitreo di Felicissimo ad Ostia, denominato Scala delle Sette Porte. Sia Celso sia Porfirio ci parlano di un’iniziazone con sette diversi e gerarchici gradi di conoscenza e, come rappresentato nelle sette porte di Ostia, ognuno rappresentato dall’animale simbolico e dall’Astro/Nume di riferimento. Il primo grado è rappresentato dal Corax (Corvo), egli è la base del culto mithriaco, il neofita che affronta le prime prove di umiltà, di controllo dell’ego, di mantenimento del segreto. Simboleggiato appunto da un corvo, è il messaggero degli Dei che risvegliano Mithra, avendo in Hermes-Mercurio la propria divinità tutelare. Il risveglio è l’inizio della rettificazione del myste, il risveglio della propria essenza solare: ogni rettificazione la si può riconnettere ai centri di luce, chakra nella tradizione indù o sephira in quella cabalistica, lungo il canale verticale che corre lungo la colonna vertebrale, espressione proprio di un Caduceo Ermetico che ritroviamo tra i simboli di Hermes e del Corax, ove si intrecciano le energie lunari e solari, mercuriali e sulfuree, lungo quello che viene denominato il “canale di Brahma”.  Il terzo grado è quello del Miles (Soldato), simboleggiato dallo scorpione, rappresenta, tramite la consacrazione a Mithra ed il rifiuto dell’incoronazione umana (“Mithra è la mia corona!”), l’ingresso dell’iniziato nella Milizia Celeste, coloro che combattono per il Fuoco e la Luce, avendo in Marte il proprio nume tutelare. E’ il chakra Manipura dove ha sede il fuoco, in corrispondenza con il plesso solare, o l’ottavo sephira Hod, la sapienza e la collettività, quindi Mithra che esce armato dalla grotta platonica per combattere, con la lancia di Marte, per affrontare un cammino oscuro che non conosce, è l’elemento ferreo che si attiva, l’irrazionale che cerca di purificarsi, la forza guerriera cieca, istintiva, che intraprende la via per la propria purificazione: alchemicamente si arriva alla terza operazione, quella della soluzione, ove si produce l’unione progressiva e non violenta del fisso col volatile…il Fuoco deve essere ancor tenuto basso!

Il terzo grado è quello del Miles (Soldato), simboleggiato dallo scorpione, rappresenta, tramite la consacrazione a Mithra ed il rifiuto dell’incoronazione umana (“Mithra è la mia corona!”), l’ingresso dell’iniziato nella Milizia Celeste, coloro che combattono per il Fuoco e la Luce, avendo in Marte il proprio nume tutelare. E’ il chakra Manipura dove ha sede il fuoco, in corrispondenza con il plesso solare, o l’ottavo sephira Hod, la sapienza e la collettività, quindi Mithra che esce armato dalla grotta platonica per combattere, con la lancia di Marte, per affrontare un cammino oscuro che non conosce, è l’elemento ferreo che si attiva, l’irrazionale che cerca di purificarsi, la forza guerriera cieca, istintiva, che intraprende la via per la propria purificazione: alchemicamente si arriva alla terza operazione, quella della soluzione, ove si produce l’unione progressiva e non violenta del fisso col volatile…il Fuoco deve essere ancor tenuto basso!  L’esame del settimo grado dell’iniziazione mithriaca, quello del Pater, comporta necessariamente un approfondimento del mito centrale e fondante del culto in questione, cioè il sacrificio cosmogonico ed esoterico del toro: tale mito, insieme alla tutela mithriaca dei patti e dei giuramenti, è sicuramente presente sin dall’origini indoiraniche della divinità e ne rappresenta simbolicamente la più alta valenza metafisica. Mithra nato dalla roccia il giorno del Solstizio d’Inverno e uscito dalla caverna nel grado di Miles, sa di dover immolare il toro, per ordine degli Dei su mandato del loro messaggero, il corvo Hermes-Mercurio.

L’esame del settimo grado dell’iniziazione mithriaca, quello del Pater, comporta necessariamente un approfondimento del mito centrale e fondante del culto in questione, cioè il sacrificio cosmogonico ed esoterico del toro: tale mito, insieme alla tutela mithriaca dei patti e dei giuramenti, è sicuramente presente sin dall’origini indoiraniche della divinità e ne rappresenta simbolicamente la più alta valenza metafisica. Mithra nato dalla roccia il giorno del Solstizio d’Inverno e uscito dalla caverna nel grado di Miles, sa di dover immolare il toro, per ordine degli Dei su mandato del loro messaggero, il corvo Hermes-Mercurio.  Molti sono stati gli scritti, gli articoli, i testi che profondamente hanno indagato la simbolica e l’essenza tradizionale e spirituale dell’iniziazione mithriaca, ma, purtroppo, pochi hanno ben evidenziato come il settimo grado di tale culto misterico, quello del Pater, non rappresentasse l’ultima tappa dell’ascensione al Divino. Se profanamente si provasse a schematizzare il processo iniziatico di cui si è scritto, sarebbe possibile confrontarlo, riducendo il settenario in forma quaternaria, alle varie fasi dell’Opera Alchemica ed alla suddivisione microcosmica operata dal Kremmerz e dalla sua Schola. Infatti, le prime quattro figure che partono dal Corax ed arrivano al Leone è possibile paragonarle alle quattro operazioni dell’Opera al Nero, la Nigredo (calcinazione, putrefazione, soluzione, distillazione ), mentre la figura del Pherses, sotto l’egida astrale della Luna, e quella di Heliodromos, portatore del Sole ma non il Sole, configurano la dimensione numinosa della nuda Diana, dell’immortalità virtuale, quindi della realizzazione dell’Opera al Bianco, Albedo.

Molti sono stati gli scritti, gli articoli, i testi che profondamente hanno indagato la simbolica e l’essenza tradizionale e spirituale dell’iniziazione mithriaca, ma, purtroppo, pochi hanno ben evidenziato come il settimo grado di tale culto misterico, quello del Pater, non rappresentasse l’ultima tappa dell’ascensione al Divino. Se profanamente si provasse a schematizzare il processo iniziatico di cui si è scritto, sarebbe possibile confrontarlo, riducendo il settenario in forma quaternaria, alle varie fasi dell’Opera Alchemica ed alla suddivisione microcosmica operata dal Kremmerz e dalla sua Schola. Infatti, le prime quattro figure che partono dal Corax ed arrivano al Leone è possibile paragonarle alle quattro operazioni dell’Opera al Nero, la Nigredo (calcinazione, putrefazione, soluzione, distillazione ), mentre la figura del Pherses, sotto l’egida astrale della Luna, e quella di Heliodromos, portatore del Sole ma non il Sole, configurano la dimensione numinosa della nuda Diana, dell’immortalità virtuale, quindi della realizzazione dell’Opera al Bianco, Albedo.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Droite du travail, gauche des valeurs. La politique du gouvernement Hollande semble se résumer à deux axes en apparence opposés mais en réalité convergents : mise aux normes mondialistes de l’économie française, pénalisation toujours plus forte du « racisme et de l’antisémitisme » sous couvert de lutte contre le djihadisme. Pendant que le gouvernement Hollande s’active à dépouiller les travailleurs français de leurs dernières protections face à la violence de l’économie de marché, il fait mine de protéger les personnes supposées vulnérables à la discrimination ethnique ou religieuse par une législation toujours plus stricte. Dans les deux cas, la méthode est similaire : passage en force et autoritarisme. Le but également : cette compassion victimaire (d’ailleurs à géométrie variable) sert le projet mondialiste en disqualifiant les oppositions à sa politique.

Droite du travail, gauche des valeurs. La politique du gouvernement Hollande semble se résumer à deux axes en apparence opposés mais en réalité convergents : mise aux normes mondialistes de l’économie française, pénalisation toujours plus forte du « racisme et de l’antisémitisme » sous couvert de lutte contre le djihadisme. Pendant que le gouvernement Hollande s’active à dépouiller les travailleurs français de leurs dernières protections face à la violence de l’économie de marché, il fait mine de protéger les personnes supposées vulnérables à la discrimination ethnique ou religieuse par une législation toujours plus stricte. Dans les deux cas, la méthode est similaire : passage en force et autoritarisme. Le but également : cette compassion victimaire (d’ailleurs à géométrie variable) sert le projet mondialiste en disqualifiant les oppositions à sa politique. Nicolas Bourgoin, né à Paris, est démographe, docteur de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales et enseignant-chercheur. Il est l’auteur de quatre ouvrages : La révolution sécuritaire (1976-2012) aux Éditions Champ Social (2013), La République contre les libertés. Le virage autoritaire de la gauche libérale (Paris, L'Harmattan, 2015), Le suicide en prison (Paris, L’Harmattan, 1994) et Les chiffres du crime. Statistiques criminelles et contrôle social (Paris, L’Harmattan, 2008).

Nicolas Bourgoin, né à Paris, est démographe, docteur de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales et enseignant-chercheur. Il est l’auteur de quatre ouvrages : La révolution sécuritaire (1976-2012) aux Éditions Champ Social (2013), La République contre les libertés. Le virage autoritaire de la gauche libérale (Paris, L'Harmattan, 2015), Le suicide en prison (Paris, L’Harmattan, 1994) et Les chiffres du crime. Statistiques criminelles et contrôle social (Paris, L’Harmattan, 2008).

But it does. Look at Carter administration National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski’s strategic master plan, laid out in his book

But it does. Look at Carter administration National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski’s strategic master plan, laid out in his book

C’est en quelque sorte, la fabrication des Marines américains transposée à la société civile. Pour fabriquer un Marine, il faut briser l’homme, l’être humain qui est en lui: qu’il ne soit plus que « Yes Sir ». Il faut « mater » ce qui résiste, ce résidu de liberté. Ou sans être trop grandiloquent, ce résidu de libre choix. Nous ne sommes même plus dans des techniques, des conditionnements, nous sommes dans l’intrusion, la prise de possession de l’individu. Car ce qui nous constitue essentiellement, c'est ce qui nous échappe, nous tyrannise, c'est notre inconscient.

C’est en quelque sorte, la fabrication des Marines américains transposée à la société civile. Pour fabriquer un Marine, il faut briser l’homme, l’être humain qui est en lui: qu’il ne soit plus que « Yes Sir ». Il faut « mater » ce qui résiste, ce résidu de liberté. Ou sans être trop grandiloquent, ce résidu de libre choix. Nous ne sommes même plus dans des techniques, des conditionnements, nous sommes dans l’intrusion, la prise de possession de l’individu. Car ce qui nous constitue essentiellement, c'est ce qui nous échappe, nous tyrannise, c'est notre inconscient.

Given its formidable difficulties, why would anyone trouble read a book like Phenomenology of Spirit? Because, if Hegel is right, then world history comes to an end with the writing of his book. Specifically, Hegel held that the battle of Jena brought world history to an end in the concrete realm because it was the turning point in the battle between the principles of the French revolution—liberty, equality, fraternity, secularism, and progress—and the principles of traditional absolutism, the so-called throne-altar alliance.

Given its formidable difficulties, why would anyone trouble read a book like Phenomenology of Spirit? Because, if Hegel is right, then world history comes to an end with the writing of his book. Specifically, Hegel held that the battle of Jena brought world history to an end in the concrete realm because it was the turning point in the battle between the principles of the French revolution—liberty, equality, fraternity, secularism, and progress—and the principles of traditional absolutism, the so-called throne-altar alliance.

Kojève taught this seminar from 1933 to 1939. Although the seminar was very small, it had a tremendous influence on French intellectual life, for its students included such eminent philosophers and scholars as Jacques Lacan, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georges Bataille, Raymond Queneau, Raymond Aron, Gaston Fessard, and Henri Corbin. Through his students, Kojève influenced Sartre, as well as subsequent generation of leading French thinkers, who are known as “postmodernists,” including Foucault, Deleuze, Lyotard, and Derrida—all of whom felt it necessary to define their positions in accordance with or in opposition to Hegel as portrayed by Kojève.

Kojève taught this seminar from 1933 to 1939. Although the seminar was very small, it had a tremendous influence on French intellectual life, for its students included such eminent philosophers and scholars as Jacques Lacan, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georges Bataille, Raymond Queneau, Raymond Aron, Gaston Fessard, and Henri Corbin. Through his students, Kojève influenced Sartre, as well as subsequent generation of leading French thinkers, who are known as “postmodernists,” including Foucault, Deleuze, Lyotard, and Derrida—all of whom felt it necessary to define their positions in accordance with or in opposition to Hegel as portrayed by Kojève. Kojève held that most human beings at the end of history would be reduced to beasts. But some would become gods. How? By becoming wise. At the end of history, the correct and final interpretation of human existence, the Absolute Truth, has been articulated as a system of science by Hegel himself. This system is the wisdom that philosophy has pursued for more than 2,000 years.

Kojève held that most human beings at the end of history would be reduced to beasts. But some would become gods. How? By becoming wise. At the end of history, the correct and final interpretation of human existence, the Absolute Truth, has been articulated as a system of science by Hegel himself. This system is the wisdom that philosophy has pursued for more than 2,000 years.

El Islam, en cambio, incluso en nuestras sociedades, a menudo trae elementos y valores realmente incompatibles con la modernidad y, por lo tanto, difícilmente “integrables”. Y es eso lo que las fuerzas identitarias le reprochan, viendo a sus miembros como sujetos extraños y alógenos respecto a nuestro mundo, a diferencia, como se ha dicho, de los seguidores de otras religiones que, al igual que los cristianos, más allá de las formas externas que aún permanezcan en las prácticas del culto, por lo demás están totalmente homologados a las costumbres y al estilo de vida materialista y consumista propio de nuestra civilización. Así, una mujer musulmana que viste su ropa tradicional, como por ejemplo el velo, genera protestas y casi un sentimiento de repulsión que está en conformidad con nuestra “tradición”, los atuendos con los cuales se engalanan nuestras chicas respetando la última moda lanzada por la etiqueta del momento. Del mismo modo, la apertura de un kebab o de una carnicería musulmana irían a desfigurar, para los lugareños “identitarios”, la decoración urbana de nuestras calles, mientras que un McDonalds o un local de moda y tendencias no. Los ejemplos podrían multiplicarse: hace años, en Suiza, los partidos identitarios organizaron un referéndum contra la construcción de minaretes porque éstos implicarían la ruptura de la arquitectura típica de las ciudades suizas: no consta que tales partidos, en Suiza como en otros lugares, se hayan levantado alguna vez, al menos con el mismo ardor, en contra de la excéntrica arquitectura moderna que desfigura habitualmente nuestros centros históricos, como en general nuestros barrios, por no hablar de los eco-monstruos de nuestros suburbios, donde ahora todo el sentido de la proporción, la armonía, y por lo tanto de lo “bello” está completamente perdido, y no ciertamente por culpa de los minaretes o de quién sabe qué otro exótico edificio.

El Islam, en cambio, incluso en nuestras sociedades, a menudo trae elementos y valores realmente incompatibles con la modernidad y, por lo tanto, difícilmente “integrables”. Y es eso lo que las fuerzas identitarias le reprochan, viendo a sus miembros como sujetos extraños y alógenos respecto a nuestro mundo, a diferencia, como se ha dicho, de los seguidores de otras religiones que, al igual que los cristianos, más allá de las formas externas que aún permanezcan en las prácticas del culto, por lo demás están totalmente homologados a las costumbres y al estilo de vida materialista y consumista propio de nuestra civilización. Así, una mujer musulmana que viste su ropa tradicional, como por ejemplo el velo, genera protestas y casi un sentimiento de repulsión que está en conformidad con nuestra “tradición”, los atuendos con los cuales se engalanan nuestras chicas respetando la última moda lanzada por la etiqueta del momento. Del mismo modo, la apertura de un kebab o de una carnicería musulmana irían a desfigurar, para los lugareños “identitarios”, la decoración urbana de nuestras calles, mientras que un McDonalds o un local de moda y tendencias no. Los ejemplos podrían multiplicarse: hace años, en Suiza, los partidos identitarios organizaron un referéndum contra la construcción de minaretes porque éstos implicarían la ruptura de la arquitectura típica de las ciudades suizas: no consta que tales partidos, en Suiza como en otros lugares, se hayan levantado alguna vez, al menos con el mismo ardor, en contra de la excéntrica arquitectura moderna que desfigura habitualmente nuestros centros históricos, como en general nuestros barrios, por no hablar de los eco-monstruos de nuestros suburbios, donde ahora todo el sentido de la proporción, la armonía, y por lo tanto de lo “bello” está completamente perdido, y no ciertamente por culpa de los minaretes o de quién sabe qué otro exótico edificio.

Un certain Volker Beck (ci-contre), député des « Verts » au parlement allemand, s’est récemment jeté sur le clavier de son ordinateur pour se fendre d’une lettre au ministère fédéral des affaires étrangères pour réclamer qu’Alexandre Douguine, le militant eurasiste russe, soit placé sur la « liste noire » des Russes sanctionnés par l’UE, afin, na! tralala!, qu’il ne puisse plus venir en Europe pour exposer ses thèses eurasistes et « multipolaires », pour le plus grand bien des chimères transatlantiques et unipolaires assénées par CNN et les cliques néo-libérales et otanesques (on se demande ce que doivent en penser ses électeurs, nombreux, issus des vieilles gauches allemandes...?). Le magazine allemand Zuerst avait en effet invité le politologue russe comme orateur pour participer à un colloque réservé à ses abonnés et lecteurs, événement qui doit se tenir début mars. L’agitation frénétique du député vert semble toutefois être sans objet : la « liste noire » de l’UE ne compte que des hommes d’affaires ou des représentants officiels de l’Etat russe : Douguine, lui, ne fait pas d’affaires et ne détient aucun mandat ou fonction au sein de la Fédération de Russie.

Un certain Volker Beck (ci-contre), député des « Verts » au parlement allemand, s’est récemment jeté sur le clavier de son ordinateur pour se fendre d’une lettre au ministère fédéral des affaires étrangères pour réclamer qu’Alexandre Douguine, le militant eurasiste russe, soit placé sur la « liste noire » des Russes sanctionnés par l’UE, afin, na! tralala!, qu’il ne puisse plus venir en Europe pour exposer ses thèses eurasistes et « multipolaires », pour le plus grand bien des chimères transatlantiques et unipolaires assénées par CNN et les cliques néo-libérales et otanesques (on se demande ce que doivent en penser ses électeurs, nombreux, issus des vieilles gauches allemandes...?). Le magazine allemand Zuerst avait en effet invité le politologue russe comme orateur pour participer à un colloque réservé à ses abonnés et lecteurs, événement qui doit se tenir début mars. L’agitation frénétique du député vert semble toutefois être sans objet : la « liste noire » de l’UE ne compte que des hommes d’affaires ou des représentants officiels de l’Etat russe : Douguine, lui, ne fait pas d’affaires et ne détient aucun mandat ou fonction au sein de la Fédération de Russie.

Massaslachting van christenen door moslims doodgezwegen

Massaslachting van christenen door moslims doodgezwegen

Qu’une nation, quelle qu’elle soit, privilégie ses nationaux plutôt que les étrangers résidant sur son sol, c’est la règle communément admise sur la planète. Ce fut même le cas en France, avec la loi de préférence nationale à l’embauche, votée au Parlement, en 1935, à l’instigation de la CGT, de Roger Salengro et d’un certain Léon Blum ; ces deux derniers n’étant pas, faut-il le préciser, des nazis furieux.

Qu’une nation, quelle qu’elle soit, privilégie ses nationaux plutôt que les étrangers résidant sur son sol, c’est la règle communément admise sur la planète. Ce fut même le cas en France, avec la loi de préférence nationale à l’embauche, votée au Parlement, en 1935, à l’instigation de la CGT, de Roger Salengro et d’un certain Léon Blum ; ces deux derniers n’étant pas, faut-il le préciser, des nazis furieux.