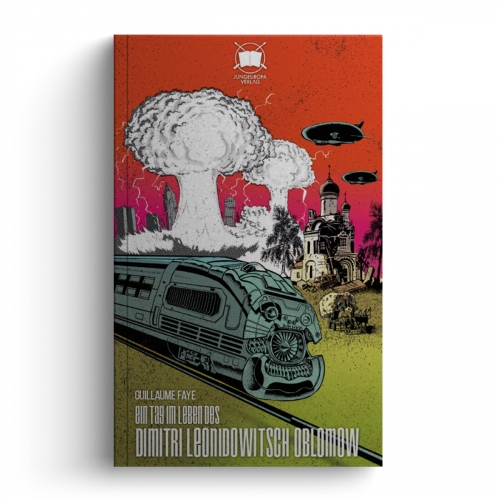

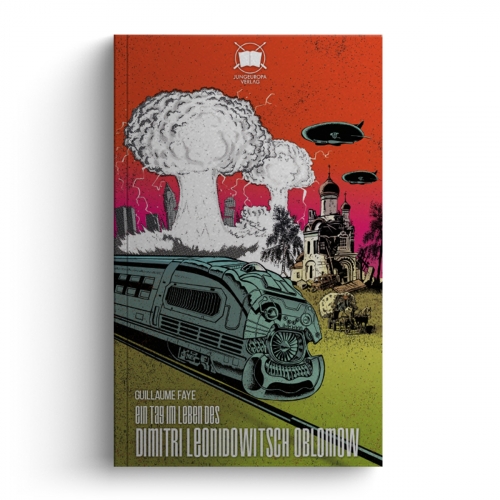

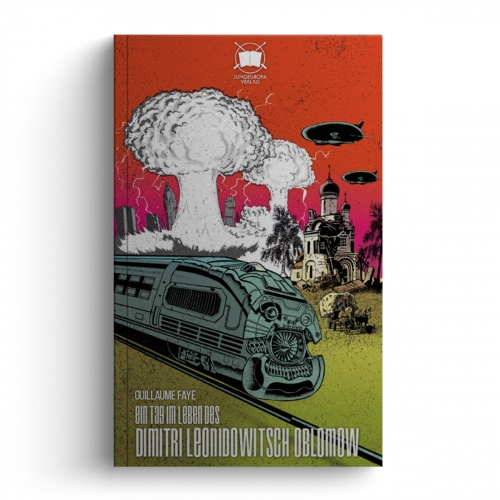

Mit Guillaume Fayes Novelle Ein Tag im Leben des Dimitri Leonidowitsch Oblomow haben wir die erste, dezidiert rechte Science-Fiction-Erzählung in deutscher Sprache publiziert. Martin Lichtmesz, der das Buch aus dem Französischen übersetzte, nennt sie eine von »schwarzem Humor durchzogene Erzählung von erheblichem Reiz«. Um mehr über diese einzigartige Novelle, ihre Entstehungsgeschichte sowie ihren streitbaren und durchaus sonderbaren Autor zu erfahren, haben wir mit dem belgischen Publizisten Robert Steuckers gesprochen, der Faye mehrere Jahrzehnte kannte und sein politisches Werk stets genau beobachtet hat.

Sehr geehrter Herr Steuckers, ein Belgier und ein Deutscher führen ein Interview in deutscher Sprache, ganz ohne Übersetzer. Wenn ich richtig liege, hätte ich Ihnen meine Fragen jedoch auch auf Spanisch, Französisch oder Englisch stellen können. Wie kommen Sie zu diesem beeindruckenden europäischen Sprachschatz?

Sehr geehrter Herr Steuckers, ein Belgier und ein Deutscher führen ein Interview in deutscher Sprache, ganz ohne Übersetzer. Wenn ich richtig liege, hätte ich Ihnen meine Fragen jedoch auch auf Spanisch, Französisch oder Englisch stellen können. Wie kommen Sie zu diesem beeindruckenden europäischen Sprachschatz?

Das ist eigentlich nicht erstaunlich, hierzulande bin ich nicht der Einzige. Professor David Engels schreibt ebenfalls sowohl auf Französisch als auch auf Deutsch. Gewiss, weil er aus Eupen (nahe dem Dreiländereck) stammt. Einer meiner Kollegen, der Journalist Lionel Baland aus Lüttich, der sich auf nonkonforme populistische Parteien und Verbände spezialisiert hat, arbeitet auch mit vier Sprachen (Französisch, Deutsch, Niederländisch und Englisch). Dr. Frank Judo, ein guter Bekannter, hat im Zuge eines Symposiums in der Bibliothek des Konservatismus das Wort auf Deutsch ergriffen. Es gibt zahlreiche weitere Beispiele. In meinem Freundeskreis in Löwen ist die deutsche Sprache sehr oft in Gebrauch und alle Mitglieder sind sogar dazu angehalten, sie gut zu beherrschen, um beitreten zu dürfen. Ich bin ja auch Diplom-Übersetzer. Man könnte also sagen, dass uns nur zwei Lautverschiebungen trennen. Außerdem habe ich noch Latein studiert. So sind die romanischen Sprachen einfach zu lernen und zu beherrschen. Dazu kommt, dass meine Frau in Madrid (am Fuß der Hügel, an denen sich der Königliche Palast befindet) geboren wurde. Das ist natürlich auch hilfreich.

Ihren vielfältigen publizistischen und politischen Tätigkeiten zum Trotz soll es heute nicht um Sie gehen. Wir wollen über Guillaume Faye sprechen – genauer gesagt über seine Novelle Ein Tag im Leben des Dimitri Leonidowitsch Oblomow, die kürzlich bei uns erschienen ist. Auf Twitter haben Sie die deutsche Erstveröffentlichung sehr wohlwollend, regelrecht euphorisch kommentiert. Verraten Sie uns, wieso?

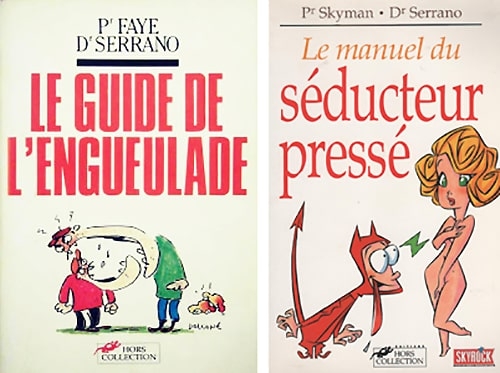

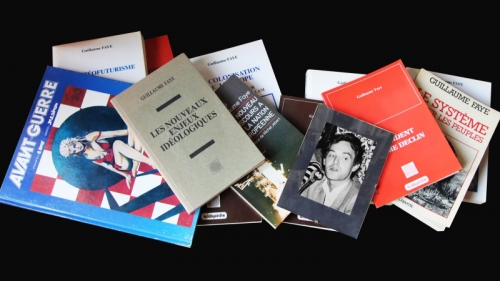

Fayes große Hoffnung war es, dass seine Texte einmal in die deutsche Sprache übersetzt werden. Sie sind also diejenigen, die post mortem diesen allertiefsten Wunsch erfüllt haben. Mit dieser Euphorie – wie Sie es nennen – habe ich im Grunde die Freude, die er bei Erscheinen dieses Buches auf Deutsch nach so langer Zeit empfunden hätte, stellvertretend zum Ausdruck gebracht. Der Verleger Wigbert Grabert hat in der Vergangenheit einige Texte von Faye übersetzen lassen, doch leider nicht seine so wichtigen Werke über Wirtschaft, Sexualität, Konsumgesellschaft, Moderne, die wirklich als Pionierarbeit innerhalb unserer Kreise bezeichnet werden müssen. Faye versuchte in den 1980er Jahren sehr aktiv in avantgardistischen Kreisen mitzuwirken.

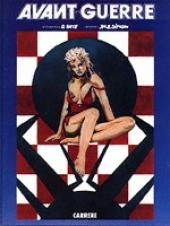

Kürzlich habe ich auf Facebook eine kurze Erwähnung seiner Pariser »Avant-Guerre«-Abende gefunden. Pierre Robin, ein Kumpan von damals, ist der Autor. Robin beschreibt sehr genau, was eigentlich in Fayes Kopf konzipiert wurde. So schreibt er treffend, dass Faye überhaupt nicht von der »New Wave«-Mode oder deren Musik fasziniert war, doch er wusste sehr wohl, dass ohne ein »Update« der eigenen Ausdrucksformen keine neue Politik zu machen war. Faye habe es, so schreibt es Robin in seinen Erinnerungen, für unmöglich gehalten, die klassische griechisch-aristotelische oder eben die dionysische Weltanschauung wieder lebendig zu machen; vor allem nicht mit einer bloßen »schulmeisterlichen« Lobpreisung des gymnasialen, bürgerlichen Humanismus. Deshalb hat Faye stets nach anderen Werkzeugen gesucht, um der modernen Misere zu entkommen.

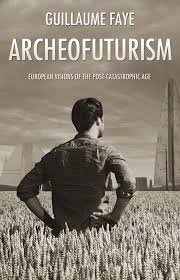

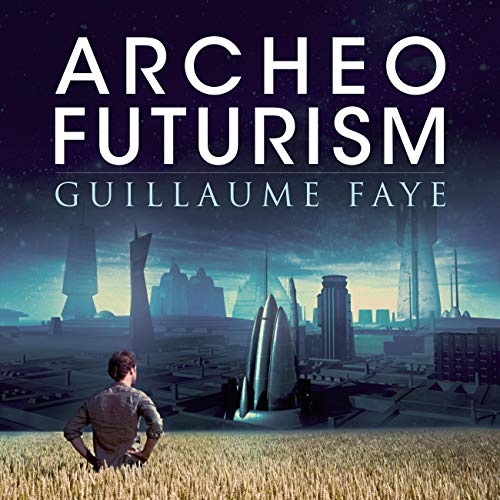

Es ist kein Geheimnis, dass die Novelle eigentlich »nur« ein literarischer Anhang zu Fayes umfassendem Buch L’Archéofuturisme ist, in dem er seine Ideen einer zukünftigen Welt nach der »Großen Katastrophe« beschreibt und ausführt. Können Sie umreißen, was Faye unter dem Begriff »Archäofuturismus« versteht und was seinen ideologischen Kern ausmacht?

Es ist kein Geheimnis, dass die Novelle eigentlich »nur« ein literarischer Anhang zu Fayes umfassendem Buch L’Archéofuturisme ist, in dem er seine Ideen einer zukünftigen Welt nach der »Großen Katastrophe« beschreibt und ausführt. Können Sie umreißen, was Faye unter dem Begriff »Archäofuturismus« versteht und was seinen ideologischen Kern ausmacht?

Die Novelle macht eigentlich schon sehr gut deutlich, was er damit meint. Die Staatselite bzw. die Elite des Imperiums, die vielseitig gebildeten Köpfe der Föderation und letztendlich auch die Armeen sind futuristisch geprägt, verwenden hypermoderne Technologien und benutzen sie als Werkzeuge einer scheinbar unzerstörbaren geopolitischen Macht. Der Rest der Bevölkerung ist derweil wieder erdgebunden, agrarisch geprägt und entwickelt eine ewig bleibende, gewissermaßen auch »völkische« Kultur. Archäofuturismus bedeutet sozusagen ein archaisch-agrarisch-ökologisches Leben für das breite Volk und ein hypertechnisches und futuristisches für die ausgewählte Elite.

Faye war seinerzeit stark an Eisenbahn-Projekten interessiert, insbesondere an der Transsibirischen Baikal-Amur-Eisenbahn, der damaligen deutschen Breitspurbahn, dem gaullistischen Aérotrain und ähnlichen japanischen Projekten usw. Deshalb verbringt Oblomow seinen Tag in einem überwiegend unterirdisch fahrenden Zug. Hauptaufgabe des staatlichen Wesens war es für Faye, superschnelle Kommunikationen zu ermöglichen, genauso wie das Römische Reich straßengebunden und straßenabhängig war. Mein Sohn und ich waren eines Tages erstaunt, als wir beide feststellten, dass Faye eifrig Magazine über allerlei neue Technologien, auch Biotechnologien, las, wie Science et Avenir, Science & Vie usw. Auch wenn Besserwisser eine solche Beschäftigung als skurril erachten mögen, verschafft es nichtsdestoweniger Geisteswissenschaftlern eine nötige mentale Hygiene, sich oberflächlich mit den Revolutionen in den Naturwissenschaften und Hochtechnologien (wie etwa Nanotechnologie) auseinanderzusetzen.

Wieso hat Faye sich entschieden, seinem Buch noch eine Novelle, also ein literarisches Werk, anzuhängen? Um den Stoff zu verdichten? Oder steckt mehr dahinter – etwa Fayes Begeisterung für die Literatur?

Faye war, genauso wie Jean Thiriart, nicht wirklich an reiner Literatur interessiert. Er las querbeet Soziologie (Maffesoli, Lipovetsky), Philosophie (Heidegger), Politikwissenschaft (Freund), Volkswirtschaft (List, Perroux, Grjebine), Geschichte und Geographie. Eine Ausnahme bei diesen beiden nonkonformen Autoren war sicherlich Louis-Ferdinand Céline, den sie beide sehr schätzten. Ziel dieser kleinen, aber gut abgerundeten Novelle war es, seine Leser für den Doppelaspekt zu begeistern, den der von ihm konzipierte Archäofuturismus in sich trägt, nämlich die Notwendigkeit, zu gleicher Zeit hypertechnisch und archaisch-organisch zu denken. Er bedauerte, dass neurechte Kreise solche Themen nie erwähnten oder sogar ablehnten. Diese negative Haltung den Hochtechnologien oder den Biotechnologien gegenüber war für ihn Indiz einer unpolitischen, kontemplativen, musealen Anschauung, was er auch sehr deutlich und umfangreich im Kern seines Buches L’Archéofuturisme erklärt.

Er hat sich gewünscht, eine Science-Fiction-Welt zu schaffen, um die Literaten (so wie sich Thiriart spöttisch ausdrückte!) der Neuen Rechten dazu zu bewegen, sich endlich für zukunftsfähige Themen zu interessieren. Das gilt natürlich auch für Biotechnologien, was übrigens sein langjähriger italienischer Freund und Jurist Stefano Sutti Vaj als Thema für eines seiner Bücher gewählt hat. Der Futurismus Fayes muss zusammen mit dem »Biotechnologismus« Suttis gedacht werden. Aber beide Annäherungen sind leider innerhalb der neurechten Kreise unbeachtet geblieben.

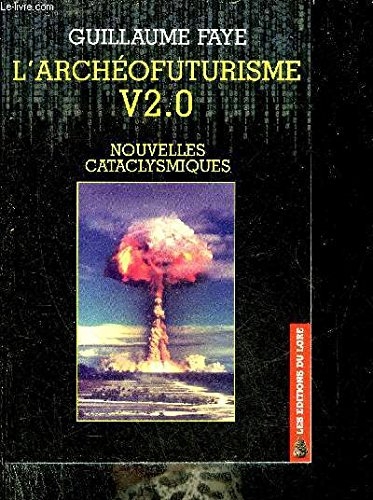

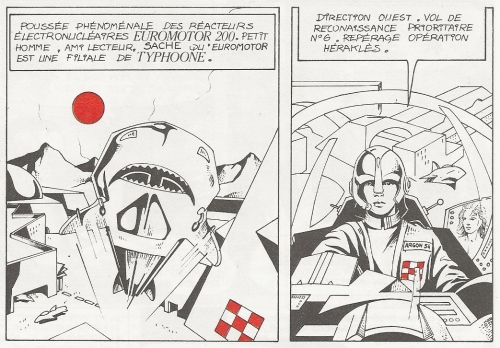

Für seine literarische Begeisterung spricht auch die Ausgestaltung des »Nachfolgebuches« L’Archéofuturisme V2.0: Nouvelles Cataclysmiques, ein ausschließlich aus Kurzgeschichten bestehender Band, der den Archäofuturismus erneut in den Fokus rückt. Doch schon 1985 beteiligte sich Faye als Autor an dem Comic-Band Avant-Guerre, in dem viele Motive seiner späteren Novellen, etwa die »Eurosibirische Föderation«, angelegt sind. Hat Faye gewissermaßen eine große Geschichte, eine eigene Welt, erfunden, die er über Jahre ausgestaltete und fortführte?

Für seine literarische Begeisterung spricht auch die Ausgestaltung des »Nachfolgebuches« L’Archéofuturisme V2.0: Nouvelles Cataclysmiques, ein ausschließlich aus Kurzgeschichten bestehender Band, der den Archäofuturismus erneut in den Fokus rückt. Doch schon 1985 beteiligte sich Faye als Autor an dem Comic-Band Avant-Guerre, in dem viele Motive seiner späteren Novellen, etwa die »Eurosibirische Föderation«, angelegt sind. Hat Faye gewissermaßen eine große Geschichte, eine eigene Welt, erfunden, die er über Jahre ausgestaltete und fortführte?

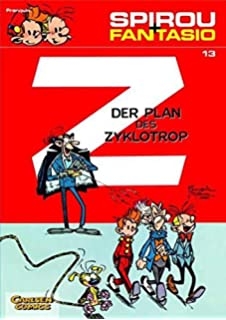

Ja, das stimmt. Schon immer hat er sich für Raumfahrt und für das europäische Ariane-Projekt interessiert. Diese Begeisterung war auch das Resultat einer kindlichen und jugendlichen Sympathie für belgische Comics oder, besser gesagt, für Graphic Novels, wie die Engländer heute sagen. Zwei Serien waren entscheidend für die lebenslange Neigung Fayes, wissenschaftlich-technologisch, also futuristisch, zu denken. Zu nennen wäre hier die Serie Spirou & Fantasio von Franquin, in der zwei Wissenschaftler konkurrieren: zum einen Zorglub, der erstaunliche fliegende Maschinen konzipiert, baut und dann hunderte Raketen zum Mond schickt, um Werbung für Coca-Cola zu machen; zum anderen Pacôme, Graf de Champignac, der Chemiker ist und verblüffende organische Waffen aus Pilzen entwickelt, wie etwa das »Metamol«, das alle Metalle weich und flüssig werden lässt.

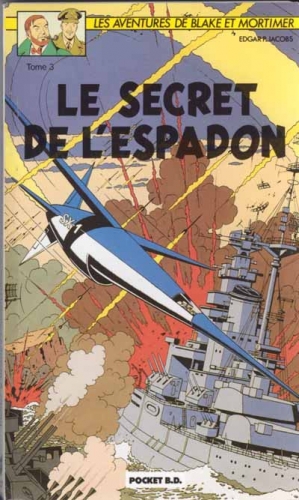

Das »Metamol« vernichtet eine südamerikanische Armee und chinesische Panzer, Zorglubs Stützpunkt im Dschungel Amazoniens wird mit Handgranaten zerstört, die ein allesfressendes Pilzextrakt enthalten, womit alle menschlichen Konstruktionen buchstäblich aufgelöst werden. Weiter in der Reihe Blake und Mortimer von Edgard P. Jacobs, findet man eine graphische Novelle, in der sich ein Atlantis-Reich unterseeisch in der Mitte des Atlantischen Ozeans direkt unter den Azoren befindet. Dieses unterseeische Reich wird von einem alten ehrwürdigen Basileus sanft geleitet, aber zur gleichen Zeit von aufgehetzten Barbaren bedroht. Die Barbaren siegen und zerstören die schützenden Deiche, wobei die musterhafte Polis platonischer Prägung überflutet wird. Aber die Atlanten und ihr Führer Basileus können rechtzeitig unsere Erde an Bord von hunderten Raumschiffen verlassen, um eine Zukunft auf einem anderen Planeten zu schaffen.

Das »Metamol« vernichtet eine südamerikanische Armee und chinesische Panzer, Zorglubs Stützpunkt im Dschungel Amazoniens wird mit Handgranaten zerstört, die ein allesfressendes Pilzextrakt enthalten, womit alle menschlichen Konstruktionen buchstäblich aufgelöst werden. Weiter in der Reihe Blake und Mortimer von Edgard P. Jacobs, findet man eine graphische Novelle, in der sich ein Atlantis-Reich unterseeisch in der Mitte des Atlantischen Ozeans direkt unter den Azoren befindet. Dieses unterseeische Reich wird von einem alten ehrwürdigen Basileus sanft geleitet, aber zur gleichen Zeit von aufgehetzten Barbaren bedroht. Die Barbaren siegen und zerstören die schützenden Deiche, wobei die musterhafte Polis platonischer Prägung überflutet wird. Aber die Atlanten und ihr Führer Basileus können rechtzeitig unsere Erde an Bord von hunderten Raumschiffen verlassen, um eine Zukunft auf einem anderen Planeten zu schaffen.

Zudem war Faye auch von Jacobs gezeichneten Flugzeugen fasziniert, die in der Black und Mortimer-Trilogie Le Secret de l’Espadon erschienen, etwa die »Rote Flügel« vom bösartigen Colonel Olrik und der »Espadon« von seinem englischen Gegner. Letzteres ist deutlich die Inspirationsquelle für Fayes »Squaline«-Jets. Überdies hat er auch mit großer Aufmerksamkeit die zwei graphischen Novellen aus der Reihe Tim und Struppi verfolgt, in denen Tim und Kapitän Haddock in einer V2-ähnlichen Rakete zum Mond fliegen. Auch die Ultraschall-Waffen von Professor Baldwin Bienlein (Tryphon Tournesol auf Französisch) im Album Der Fall Bienlein interessierten ihn. Und so weiter, und so fort.

Hand aufs Herz: Wie viel Science-Fiction steckt in Ein Tag im Leben des Dimitri Leonidowitsch Oblomow und Fayes anderen Novellen? Der Autor behauptet jedenfalls, es handele sich um eine durchaus realistische Zukunftsvision…

Faye träumte von einer »eurorussischen« Partnerschaft, wobei die riesigen Entfernungen zwischen der Bretagne, die er abgöttisch liebte, weil sein bester Freund, der bretonische Kulturnationalist Yann-Ber Tillenon, ihm die bretonnitude beigebracht hatte und immer sein treuester Unterstützer geblieben ist, und Ostsibirien, etwa Kamtschatka, durch hyperschnelle Kommunikationsmittel überbrückt würden. In der kurzen Novelle ist eine solche »Föderation« Wirklichkeit geworden. Und wie ich bereits gesagt habe, ist die Elite hochtechnisiert und futuristisch geprägt, weil das Volk agrarisch wirkt und seine alten keltischen, germanischen oder slawischen Wurzeln lebendig bewahrt. Eigentlich versöhnt er hier zwei vollkommen unterschiedliche Orientierungen im konservativ-revolutionären bzw. national-revolutionären Lager, d. h. er löst den Widerspruch zwischen Ernst Jüngers Arbeiter-Welt und Friedrich Georg Jüngers Anti-Technizismus.

Mit L’Archéofuturisme feierte Faye 1998 sein publizistisches Comeback, nachdem er viele Jahre als »unpolitischer« Radiomoderator arbeitete und der Politik gewissermaßen den Rücken gekehrt hatte. Zuvor hatte er sich von der Nouvelle Droite um Alain de Benoist gelöst bzw. wurde dort unsanft entfernt. Ihnen erging es ähnlich. Hatten Sie beide damals Kontakt? Wie ist das Comeback Fayes, vor allem vor dem Hintergrund einer solchen archäofuturistischen Utopie, einzuschätzen? Und wie würden Sie Faye zu dieser Zeit charakterisieren?

Acht Monate hat es ungefähr gedauert, zwischen Sommer 1986 und März 1987, bevor er sich definitiv von Alain de Benoist getrennt hatte. Die Sommer-Uni 1986 war diesbezüglich ein Fiasko. Seinen Unmut hatte er anlässlich des jährlichen Symposiums im November 1986 deutlich zum Ausdruck gebracht. Seinen öffentlichen Abschiedsbrief – in sehr versöhnlichen Tönen – veröffentlichte er im Mai 1987. Die deutsche Fassung davon habe ich selbst bearbeitet; sie ist in der Zeitschrift DESG-Inform aus Hamburg erschienen. Damals war ich dank der Unterstützung von Jean van der Taelen und Guibert de Villenfagne de Sorinnes Teil des Pariser Klübchens geworden. Jean-Marie Simar aus Lüttich hatte drei Broschüren von Faye mit sehr geringen Mitteln herausgegeben: Europe et Modernité (sicherlich der tiefschürfendste Essay, den er je verfasst hat), Petit Lexique du Partisan européen (erster Entwurf von Wofür wir kämpfen) und L’Occident comme déclin (ein ausgezeichneter Essay, der leider nie übersetzt worden ist, noch nicht mal auf Englisch).

Nach dem Bruch habe ich natürlich nicht sektiererisch meinen alten Freund Faye exkommunizieren wollen. Wir haben uns im August 1987 in der Schweiz getroffen, wo Pascal Junod, der noch kein Rechtsanwalt war, ein gesamteuropäisches Fest organisiert hatte. Faye verteilte dort seinen Abschiedsbrief und traf eine Menge Freunde, die aus allen Gegenden Frankreichs angereist waren. Ich nutzte die Gelegenheit, ihn im September nach Brüssel ins Métropole-Hotel einzuladen, um ein Buch (La soft-idéologie) und ein Thema vorzustellen, das er zusammen mit dem berühmten französischen Strategen und Medien-Analysten François-Bernard Huyghe geschrieben hatte. Faye pflegte damals Kontakte zu höchsten akademischen Kreisen. Sein Vortrag über die »Soft-Ideologie« war der letzte, den er vor neurechtem Publikum gehalten hatte. Danach ist er für mich spurlos im Labyrinth von alternativen Medien verschwunden.

Sein Comeback war diskret, aber, wie üblich, gekonnt umgesetzt. Er gab der Redaktion der damals jungen Zeitschrift Réfléchir & Agir (die man heute in allen Kiosken Frankreichs kaufen kann), ein Interview. Hauptthema des Gesprächs war eine Darstellung der neuen zeitgenössischen Musikströmungen, die einen durschlagenden Effekt auf Gesellschaft und Politik hätten, wenn sie zur gleichen Zeit auch in eine solche Richtung durch eine weltanschauliche Elite gelenkt würden. So könnte eine alternative Welt geschaffen werden.

Sein Comeback war diskret, aber, wie üblich, gekonnt umgesetzt. Er gab der Redaktion der damals jungen Zeitschrift Réfléchir & Agir (die man heute in allen Kiosken Frankreichs kaufen kann), ein Interview. Hauptthema des Gesprächs war eine Darstellung der neuen zeitgenössischen Musikströmungen, die einen durschlagenden Effekt auf Gesellschaft und Politik hätten, wenn sie zur gleichen Zeit auch in eine solche Richtung durch eine weltanschauliche Elite gelenkt würden. So könnte eine alternative Welt geschaffen werden.

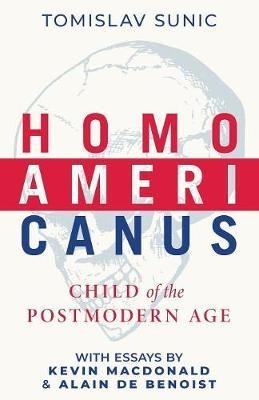

Ein gemeinsamer Freund, der Réfléchir & Agir vertrieb, organisierte ein Treffen in Brüssel, weil Faye es wünschte, mich einmal wiederzusehen, bevor er in der Szene wieder öffentlich auftauchen konnte. Und eines Tages, im Frühling 1998, klingelte Faye an der Tür. Natürlich war er etwas älter geworden, da das Leben in der Welt des »Showbiz« nicht besonders ruhig und nüchtern verlief. Das hinterließ natürlich Spuren. Aber wir haben das Gespräch so angefangen, als ob die letzte Versammlung seiner »Etudes & Recherches«-Gruppe erst eine Woche vorher stattgefunden hätte. Er hatte noch immer ein frohes Gemüt und einen hellwachen Geist. Er legte seinen Begriff des Archäofuturismus dar und kündigte unserer Versammlung das Erscheinen seines Buches an. Einige Mitglieder der Hamburger »Synergon«-Sektion sowie Dr. Tomislav Sunic waren mit dabei. Ein unvergesslicher Tag.

Stichwort »Eurosibirische Föderation«: Faye nimmt in seiner Novelle eine Position ein, die dem »Eurasien-Konzept« Alexander Dugins entgegensteht – Er plädiert nämlich für ein »Eurosibirien«, das nur die »europäischen« Teile Russlands miteinbezieht. Wie bewerten Sie diese Position – auch vor dem Hintergrund der einstigen Streitigkeiten in der französischen Neuen Rechten zu dieser Frage – heute?

Tja, man sollte, glaube ich, die Differenzen zwischen »Eurasien« und »Eurosibirien« nicht allzu ernst nehmen. Dugin ist konsequenter, da er wirklich in der russischen Geschichte eingebettet ist. Dugin übergeht auch nicht einfach die Geschichte der Sowjetunion. Faye indes entwickelt eigentlich eine erweiterte gaullistische bzw. thiriartische Perspektive und hofft so einen interkontinentalen Großraum zu schaffen, der autark genug sein könnte, um Widerstand gegen andere imperiale Großräume leisten zu können. Faye ist hier ganz Schüler von Friedrich List und von François Perroux, der Pläne skizziert hatte, um dem lateinamerikanischen Kontinent eine großräumliche Kohärenz zu geben, damit er sich gegen den Imperialismus Washingtons behaupten könnte.

Faye und Tulaev in Moskau.

Für Faye, Thiriart oder Perroux sind die einzelnen Staaten Europas zu klein und ist Gesamteuropa nicht autark genug, um langfristig zu überleben. Russland seinerseits ist zu dünn bevölkert, um demographisch genug Gewicht zu haben. In Moskau und in Dendermonde (eine flämische Stadt in der Nähe Brüssels) führte Faye interessante Gespräche mit dem »neurussischen« Ideologen, Hispanisten und Kunsthistoriker Pavel Tulaev. Tulaev erhob Kritik dem Begriff »Eurosibirien« gegenüber, aus dem Grund, dass Sibirien nie ein Subjekt der Geschichte gewesen war und dass im sibirischen Raum nur Russland Subjekt der Geschichte war und ist, da das Mongolische Reich Dschingis Khans und seiner Nachfolger unwiderruflich verblichen ist. Deshalb sprachen Tulaev und der flämische Aktivist Kris Roman eher von »Euro-Rus«.

Hier liegt natürlich ein Unterschied zwischen dieser rein russisch-europäischen Perspektive und der gewissermaßen auch turanischen Perspektive, die Dugin eigen ist. Faye war immer Anhänger einer europäisch-russischen Allianz, wie zahlreiche Texte beweisen, die ich für die Euro-Synergies-Webseite übernommen habe. Streitigkeiten innerhalb der französischen Neuen Rechten gibt es diesbezüglich eigentlich kaum. Jeder ist eher pro-russisch, obwohl einige die ukrainischen Rechten unterstützen.

Die USA kommen in seiner Novelle hingegen nicht gut weg. Später ergriff er dann jedoch Partei für Israel und postulierte ein Islambild, das an die stark neokonservativ gefärbte Counterjihad-Bewegung angelehnt war. Wie ist dieser Wandel zu erklären? Und ist er, mit Verlaub, politisch ernst zu nehmen?

Mit anderen Beobachtern der amerikanischen Gesellschaft, wie etwa James Howard Kunstler, teilte Faye die Überzeugung, dass die Hektik, die grundlegend für die irre Dynamik der amerikanischen Gesellschaft ist, langfristig nicht andauern kann. Dabei sind die USA durch eine lähmende liberale Ideologie, unrealistischen bzw. unwissenschaftlichen Biblismus und einen aggressiven Moralismus geprägt. Dies sind keine echten politischen Grundlagen, wie Carl Schmitt und Julien Freund sie definiert haben. Ohne solche Grundlagen kann ein Imperium nicht überdauern. Es ist dazu verurteilt unterzugehen.

Deshalb sind, in einem fiktiven künftigen Superreich wie der »Föderation« Fayes, die USA machtpolitisch marginalisiert, weil sie, im Gegenteil zu Antaios in der griechischen Mythologie, keine Kraft aus der tellurischen Berührung mit ihrem eigenen Boden schöpfen können. Die Zukunft gehöre erdgebundenen Reichen, die eine Zukunft (»Futurum«) aus den Kräften ihrer arkhè aufbauen. Die »Föderation« sowie China und Indien stellen jeweils ein solches erdgebundenes Reich dar. Das indische junge Mädchen, das mit Oblomow reist, gehört einem Reich an, das auf vedischen Grundlagen fußt. Sie reist in ein anderes traditionelles Reich, nämlich China.

Faye war in den 1980er Jahren der leidenschaftliche Anwalt einer euro-arabischen, anti-imperialistischen Zusammenarbeit. Ein euro-arabisches Colloquium in diesem Sinn fand an der Universität Mons (Bergen) in Hennegau statt, wo für die deutsche Seite Siegfried Bublies und Karl Höffkes teilnahmen (ich war Dolmetscher). Aber seitdem haben salafistische und saudi-wahhabitische Kreise die ganze arabische Szene verändert. Salafismus und Wahhabismus sind genauso Instrumente des US-Imperialismus wie der Zionismus. Der Salafismus hat Algerien schwer getroffen und, später, Ägypten destabilisiert und Syrien in seinen heutigen traurigen Zustand manövriert. Jeder weiß heute, dass Brzezinski die afghanischen Mudschahiddin mit Stinger-Waffen unterstützen ließ und Bin Laden als saudischer Söldner gegen die Sowjets in den Hindukusch schickte. Die Lage ist nicht mehr so überschaubar wie in den 80er Jahren.

Faye war zwischen 2000 und 2004 mit dem Geopolitiker Alexandre del Valle befreundet, der damals Kopf einer pro-zionistischen Orientierung war. Deshalb haben die meisten Beobachter der neurechten Szene den Eindruck, dass er eine radikale pro-zionistische Wende durchlaufen hatte. Tatsächlich hat er, besonders in seinem Buch La nouvelle question juive, gewissermaßen überhitzt reagiert. Die Thesen von del Valle sind mittlerweile umfangreich in der französischen und italienischen Debatte verbreitet, wobei er jetzt die Muslimbruderschaft als Urheberin des Chaos in der arabischen Welt betrachtet. Del Valle begann seine Karriere, indem er die heimliche Allianz zwischen islamischen Fundamentalisten und amerikanischen neokonservativen »Falken« andeutete. Seine Analyse der Lage in Syrien ist ebenso korrekt. Aber was er vielleicht nicht sagen will (oder darf), ist, dass der Zionismus ebenfalls eine Art Instrument des US-Imperialismus ist. Die Baathisten Syriens, Russen, Chinesen und Schiiten aus dem Iran oder aus dem Libanon bilden ja auch jetzt gewissermaßen ein »Counter-Dschihad«-Bündnis. Ohne Salafisten, Wahhabiten oder Zionisten.

Guillaume Faye ist 2019 gestorben. Sie kannten ihn seit Jahrzehnten. Was war er für ein Mensch? Welche Bücher hat er privat gelesen und welche Anekdoten können Sie mit uns teilen?

Ich habe Faye Anfang des Jahres 1976 in Lille kennengelernt. Als Mensch war er immer freundlich und wohlwollend, nie aggressiv. Wenn jemand ihm neue Perspektiven eröffnete, hörte er immer aufmerksam zu. Faye studierte in einem Jesuiten-Gymnasium in Angoulême, wo er eine stark griechisch-lateinisch geprägte Bildung erhielt. Seine Bildung in klassischer Kultur war verblüffend. Platon und Aristoteles hatte er gelesen und verinnerlicht. Später, als er in Paris studierte und sich in den Arbeitskreisen zu Vilfredo Pareto und Oswald Spengler engagierte, las er besonders Vilfredo Pareto, Bertrand de Jouvenel, Julien Freund, Carl Schmitt und Raymond Ruyer. Später entdeckte er die ersten Schriften Michel Maffesolis. Seine Forschungen waren durchaus politisch, rein politisch im edlen Sinn des Wortes.

Anekdoten gibt es in Hülle und Fülle. Nur eine will ich hier erwähnen. Unmittelbar nach seinem Comeback, während der Sommer-Uni 1998 im Trentino, kam er mit kurzer Verspätung zu einem Seminar über das Werk Bertrand de Jouvenels. Der junge Referent erklärte in allen Einzelheiten die Begriffe, die Jouvenel in seinen zahlreichen Büchern geprägt hatte. Es war ein bisschen peinlich. Faye sagte dann plötzlich: »Moment, ich habe mit Jouvenel in 1967 studiert. So erklärte er diese Begriffe …«. Und er fing an, die Lektionen Jouvenels musterhaft zu wiederholen, als ob er sie am Vorabend erst gehört hatte. Er hatte noch die Fähigkeit, die »Kunst des Gedächtnisses« zu praktizieren, d. h. eine Methode anzuwenden, die man bis ins 18. Jahrhundert in Europa anwandt, um Vorträge zu halten. Er kritzelte einige Stichwörter und Pfeile auf ein winziges Stück Papier, konzipierte so einen »Weg« und konnte dann einfach zwei Stunden pausenlos reden. So hat er zum Beispiel einen Vortrag über sein Buch La convergence des catastrophes in Brüssel vorbereitet. Ich war erstaunt und bewunderte ihn umso mehr.

Abschließend, sehr geehrter Herr Steuckers, welche Projekte und Ideen verfolgen Sie aktuell?

Erstens, beharren. Ich will das Tempo halten, mit dem ich die verschiedenen Webseiten und Accounts derzeit organisiere. Zweitens will ich mein Archiv in Büchern publizieren. Da gibt es viel Arbeit. Drittens wünsche ich durch Europa zu reisen, um diejenigen zu treffen, die ebenso fleißig arbeiten und die gleiche Weltanschauung teilen.

Das Gespräch führte Philip Stein.

Ein Buck voll Anekdoten. Lieferbar bei "éditions du Lore", sowie "La nouvelle question juive", "Sexe et dévoiement" und "Archéofuturisme V2.0":

http://www.ladiffusiondulore.fr

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Pierre Vial

Pierre Vial Jean Haudry

Jean Haudry L’essor vertigineux des sciences et des techniques allait imposer une suprématie des Européens qui paraissait alors pérenne. A Arthur de Gobineau, pessimiste, leur décadence paraît inévitable : les Sumériens, les Egyptiens, les Perses, les Grecs, les Romains se sont dilués dans les alluvions du métissage. Dans son Essai sur l’inégalité des races, les Blancs sont les plus entreprenants et la sémitisation est synonyme de déclassement. Si certains de ses arguments sont aujourd’hui infirmés (les Slaves ne sont pas un ramassis d’Eurasiens et sa dévaluation des Asiatiques est tendancieuse), sa réflexion conserve un intérêt central. Pour Chamberlain et Grant, leur engouement nordiciste les pousse à certaines contre-vérités, qui ne devraient pas dévaloriser leur analyse générale, notamment l’étiolement que provoque le métissage et l’importance de l’eugénisme.

L’essor vertigineux des sciences et des techniques allait imposer une suprématie des Européens qui paraissait alors pérenne. A Arthur de Gobineau, pessimiste, leur décadence paraît inévitable : les Sumériens, les Egyptiens, les Perses, les Grecs, les Romains se sont dilués dans les alluvions du métissage. Dans son Essai sur l’inégalité des races, les Blancs sont les plus entreprenants et la sémitisation est synonyme de déclassement. Si certains de ses arguments sont aujourd’hui infirmés (les Slaves ne sont pas un ramassis d’Eurasiens et sa dévaluation des Asiatiques est tendancieuse), sa réflexion conserve un intérêt central. Pour Chamberlain et Grant, leur engouement nordiciste les pousse à certaines contre-vérités, qui ne devraient pas dévaloriser leur analyse générale, notamment l’étiolement que provoque le métissage et l’importance de l’eugénisme.

Tamerlan ravagera tout de Delhi au Caire. Il écrase les Ottomans turcophones et encage leur sultan Bajazet, mais il meurt soudain, laissant le fils de Bajazet, Mehmet Ier, fonder l’empire ottoman. Le fils de celui-ci, Mehmet II, s’empare de Constantinople en 1453. A l’est, les Safavides, des Kurdes soufis, font renaître la Perse. Ils se convertissent à un chiisme intransigeant et, en 1501, Ismaïl, qui s’est proclamé Shah de Perse, lance un djihad contre les sunnites. Le Kurdistan est déchiré entre, à l’est, l’empire perse indo-européen et chiite et, à l’ouest, l’empire ottoman turco-mongol et sunnite. Au lieu de s’en faire des alliés, Ismaïl traite les Kurdes avec rigueur et Sélim, le sultan ottoman, massacre 40.000 Kurdes chiites et met en pièces l’armée perse en 1514. A l’exception du sud-est, tout le Kurdistan est aux mains des Ottomans. Comme ils ne disposent pas des moyens de le défendre, ils en confient la charge aux Kurdes contre une parcelle d’autonomie. Comme ceux-ci se révoltent sans cesse, les Turcs rasent des centaines de villages yézidis. L’empire perse déclinant, les Afghans sunnites détruisent en 1719 sa magnifique capitale Ispahan et c’est alors le Kurde Kerim Xané Zend qui devient shah et relève la Perse. En 1830, Mir Kor chasse les Turcs et proclame l’indépendance du Kurdistan, mais les Anglais, jouant la carte ottomane contre la Russie et la Perse, le livrent aux Ottomans. Lors de la guerre de Crimée, Ils répéteront leur traitrise en leur livrant le Kurde Yeshander, qui avait réussi à lever une armée de cent mille volontaires. Le sultan forme alors le corps des auxiliaires kurdes sous commandement turc, à qui seront confiées des basses besognes, notamment le génocide des Arméniens. Un mouvement intellectuel de liberté pro-kurde émerge à la fin du XIXe siècle, malheureusement au moment où s’impose le fanatisme des Jeunes Turcs kémalistes, panislamique et panturc. En 1914, les Kurdes, qui avaient joué la carte slave, sont dans le mauvais camp. Ces mises malheureuses vont se répéter ensuite à l’envi et aujourd’hui, Trump, qui a récupéré le pétrole irakien, n’a plus besoin des Kurdes et les a livrés à la vindicte d’Erdogan.

Tamerlan ravagera tout de Delhi au Caire. Il écrase les Ottomans turcophones et encage leur sultan Bajazet, mais il meurt soudain, laissant le fils de Bajazet, Mehmet Ier, fonder l’empire ottoman. Le fils de celui-ci, Mehmet II, s’empare de Constantinople en 1453. A l’est, les Safavides, des Kurdes soufis, font renaître la Perse. Ils se convertissent à un chiisme intransigeant et, en 1501, Ismaïl, qui s’est proclamé Shah de Perse, lance un djihad contre les sunnites. Le Kurdistan est déchiré entre, à l’est, l’empire perse indo-européen et chiite et, à l’ouest, l’empire ottoman turco-mongol et sunnite. Au lieu de s’en faire des alliés, Ismaïl traite les Kurdes avec rigueur et Sélim, le sultan ottoman, massacre 40.000 Kurdes chiites et met en pièces l’armée perse en 1514. A l’exception du sud-est, tout le Kurdistan est aux mains des Ottomans. Comme ils ne disposent pas des moyens de le défendre, ils en confient la charge aux Kurdes contre une parcelle d’autonomie. Comme ceux-ci se révoltent sans cesse, les Turcs rasent des centaines de villages yézidis. L’empire perse déclinant, les Afghans sunnites détruisent en 1719 sa magnifique capitale Ispahan et c’est alors le Kurde Kerim Xané Zend qui devient shah et relève la Perse. En 1830, Mir Kor chasse les Turcs et proclame l’indépendance du Kurdistan, mais les Anglais, jouant la carte ottomane contre la Russie et la Perse, le livrent aux Ottomans. Lors de la guerre de Crimée, Ils répéteront leur traitrise en leur livrant le Kurde Yeshander, qui avait réussi à lever une armée de cent mille volontaires. Le sultan forme alors le corps des auxiliaires kurdes sous commandement turc, à qui seront confiées des basses besognes, notamment le génocide des Arméniens. Un mouvement intellectuel de liberté pro-kurde émerge à la fin du XIXe siècle, malheureusement au moment où s’impose le fanatisme des Jeunes Turcs kémalistes, panislamique et panturc. En 1914, les Kurdes, qui avaient joué la carte slave, sont dans le mauvais camp. Ces mises malheureuses vont se répéter ensuite à l’envi et aujourd’hui, Trump, qui a récupéré le pétrole irakien, n’a plus besoin des Kurdes et les a livrés à la vindicte d’Erdogan. Pour situer son imprégnation personnelle par la spiritualité païenne,

Pour situer son imprégnation personnelle par la spiritualité païenne,  Lorsque, en 1943, Maurice Martin endosse l’uniforme maudit de la Brigade Frankreich, il précisera : « Je me suis rallié à un type humain plutôt qu’à une idéologie. Le monde guérira par la personnalité allemande. » Condamné à un an de prison, il exerce ensuite de multiples métiers, dont l’enseignement de l’allemand. Aux jeunes, il apprend à être des missionnaires du combat révolutionnaire européen et de la défense de leur identité raciale, des protecteurs des identités régionales enracinées dans l’ensemble civilisationnel de la Grande Europe Blanche, laquelle inclut la Russie. Ecologiste avant la lettre, il épouse la vision jungienne du conditionnement géographiques des psychismes dans le cadre d’une psychologie des profondeurs. Il soutient le projet d’une agriculture naturelle et non-productiviste. Vis-à-vis de ses proches, il se refuse à être un gourou et recommande : « N’ayez jamais de maîtres à penser, pensez par vous-même. »

Lorsque, en 1943, Maurice Martin endosse l’uniforme maudit de la Brigade Frankreich, il précisera : « Je me suis rallié à un type humain plutôt qu’à une idéologie. Le monde guérira par la personnalité allemande. » Condamné à un an de prison, il exerce ensuite de multiples métiers, dont l’enseignement de l’allemand. Aux jeunes, il apprend à être des missionnaires du combat révolutionnaire européen et de la défense de leur identité raciale, des protecteurs des identités régionales enracinées dans l’ensemble civilisationnel de la Grande Europe Blanche, laquelle inclut la Russie. Ecologiste avant la lettre, il épouse la vision jungienne du conditionnement géographiques des psychismes dans le cadre d’une psychologie des profondeurs. Il soutient le projet d’une agriculture naturelle et non-productiviste. Vis-à-vis de ses proches, il se refuse à être un gourou et recommande : « N’ayez jamais de maîtres à penser, pensez par vous-même. » R.D.

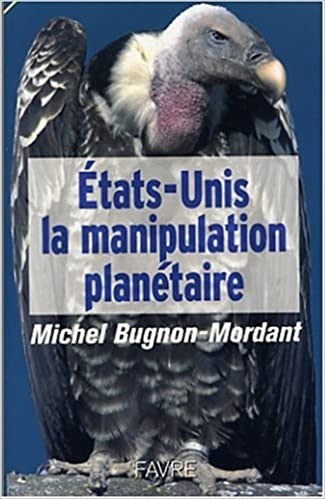

R.D. Dans ‘l’Empire prédateur d’occident’, l’essayiste helvétique

Dans ‘l’Empire prédateur d’occident’, l’essayiste helvétique

Après la chute de Tel Hai, en 1920, la Fédération sioniste autorisa Zé’ev Jabotinsky (photo) à former une Force de défense juive, la Haganah, que celui-ci voyait comme un bataillon intégré à l’armée anglaise. Mais Ben Gourion voulait une milice armée autonome et la Haganah se procure alors clandestinement des armes et organise l’entraînement de ses forces dans des associations sportives. En 1929, des attaques simultanées de colonies juives sont déclenchées dans toute la Palestine et des massacres ont lieu, les Anglais s’attachant alors à limiter la liberté d’action des sionistes. La Haganah, désormais subordonnée au seul Yishouv, l’organisation sioniste, voit naître une dissension en son sein actionnée par la Histadrout, qui défend les droits syndicaux des salariés juifs. Il en résultera la sécession de l’organisation militaire nationale Etzel (Irgoun Tsvaï Léoumi). Quand éclate la grande révolte arabe de 1936-1939 contre tant les Anglais que les Juifs, ils joignent leurs forces et des volontaires de la Haganah sont intégrés à la police. Leurs escouades de nuit organisent des coups de main. La Haganah, qui entre-temps s’est dotée du Shai, service secret très efficace, et du Ta’as, comptait en 1937 25.000 miliciens et miliciennes.

Après la chute de Tel Hai, en 1920, la Fédération sioniste autorisa Zé’ev Jabotinsky (photo) à former une Force de défense juive, la Haganah, que celui-ci voyait comme un bataillon intégré à l’armée anglaise. Mais Ben Gourion voulait une milice armée autonome et la Haganah se procure alors clandestinement des armes et organise l’entraînement de ses forces dans des associations sportives. En 1929, des attaques simultanées de colonies juives sont déclenchées dans toute la Palestine et des massacres ont lieu, les Anglais s’attachant alors à limiter la liberté d’action des sionistes. La Haganah, désormais subordonnée au seul Yishouv, l’organisation sioniste, voit naître une dissension en son sein actionnée par la Histadrout, qui défend les droits syndicaux des salariés juifs. Il en résultera la sécession de l’organisation militaire nationale Etzel (Irgoun Tsvaï Léoumi). Quand éclate la grande révolte arabe de 1936-1939 contre tant les Anglais que les Juifs, ils joignent leurs forces et des volontaires de la Haganah sont intégrés à la police. Leurs escouades de nuit organisent des coups de main. La Haganah, qui entre-temps s’est dotée du Shai, service secret très efficace, et du Ta’as, comptait en 1937 25.000 miliciens et miliciennes. Pierre Vial

Pierre Vial

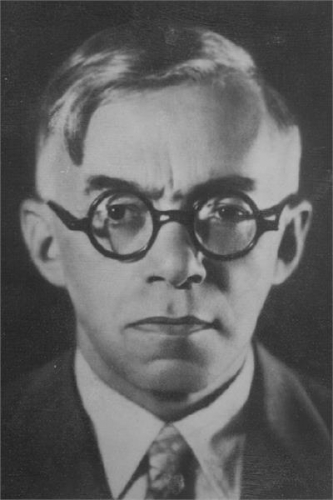

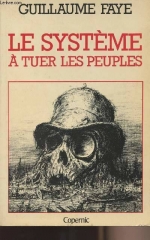

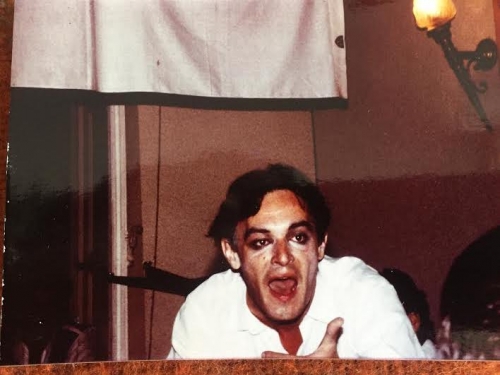

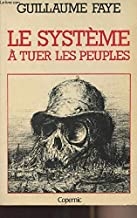

Sinon, au printemps 83, Faye est une manière de star dans le petit milieu ex. dr. : c'est, au sommet de la "Nouvelle Droite", le bras droit, jeune et branché d'Alain de Benoist, auteur d'un essai assez remarqué, Le Système à tuer les peuples, clairement anti-libéral et anti-occidental (l'Occident de Jean-Paul II et de Ronald Reagan, pour préciser sa pensée).

Sinon, au printemps 83, Faye est une manière de star dans le petit milieu ex. dr. : c'est, au sommet de la "Nouvelle Droite", le bras droit, jeune et branché d'Alain de Benoist, auteur d'un essai assez remarqué, Le Système à tuer les peuples, clairement anti-libéral et anti-occidental (l'Occident de Jean-Paul II et de Ronald Reagan, pour préciser sa pensée). Et on le devine rien qu'à le voir sur cette photo, les yeux maquillés comme une star rock, pour un regard et un profil d'oiseau de proie... Derrière lui, de dos, la nuque droitiste de Bernard Lehoux, autre disparu de la photo. Juste à gauche de lui et de dos elle aussi, Odile, soeur d'Olivier Carré, dont on appréciera l'élégant tailleur noir et la coupe asymétrique new wave et blonde. Enfin, juste derrière Faye, votre serviteur arbore le spencer Kruger et l'air sombre réglementaires... On dansera, boira et papotera pas mal, et on regardera l'enregistrement vidéo d'un défilé de mode soviétique très réussi, organisé par Jalons, où Carré et moi-même avons un rôle... Faye, un peu éméché, me proposera de collaborer à une revue confidentielle, mais aussi au magazine de droite branchée que prépare Alain Lefebvre (Magazine Hebdo) : rien de tout ceci ne se réalisera (pour moi) mais j'aurai passé une bonne soirée, ne quittant les lieux qu'à 3 heures du matin... C'était le bon temps, le temps de l'Avant-Guerre !

Et on le devine rien qu'à le voir sur cette photo, les yeux maquillés comme une star rock, pour un regard et un profil d'oiseau de proie... Derrière lui, de dos, la nuque droitiste de Bernard Lehoux, autre disparu de la photo. Juste à gauche de lui et de dos elle aussi, Odile, soeur d'Olivier Carré, dont on appréciera l'élégant tailleur noir et la coupe asymétrique new wave et blonde. Enfin, juste derrière Faye, votre serviteur arbore le spencer Kruger et l'air sombre réglementaires... On dansera, boira et papotera pas mal, et on regardera l'enregistrement vidéo d'un défilé de mode soviétique très réussi, organisé par Jalons, où Carré et moi-même avons un rôle... Faye, un peu éméché, me proposera de collaborer à une revue confidentielle, mais aussi au magazine de droite branchée que prépare Alain Lefebvre (Magazine Hebdo) : rien de tout ceci ne se réalisera (pour moi) mais j'aurai passé une bonne soirée, ne quittant les lieux qu'à 3 heures du matin... C'était le bon temps, le temps de l'Avant-Guerre !

« Je n’ai pas connu Guillaume Faye assez longtemps pour oser me compter au nombre de ses amis, mais suffisamment pour avoir partagé avec lui d’excellents moments, que j’évoque ici. Je ne lui rends pas un hommage convenu, mais salue la mémoire d’un homme resté jusqu’au bout un soldat politique, un partisan européen de la Cause blanche.

« Je n’ai pas connu Guillaume Faye assez longtemps pour oser me compter au nombre de ses amis, mais suffisamment pour avoir partagé avec lui d’excellents moments, que j’évoque ici. Je ne lui rends pas un hommage convenu, mais salue la mémoire d’un homme resté jusqu’au bout un soldat politique, un partisan européen de la Cause blanche.

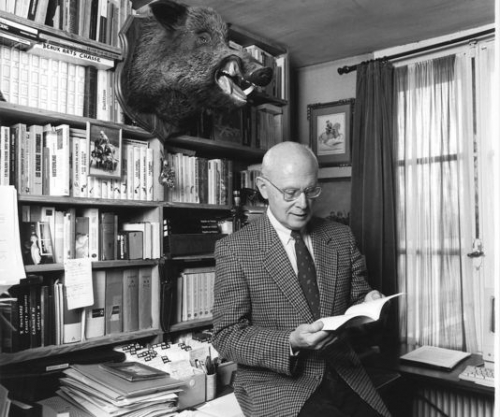

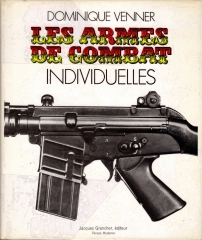

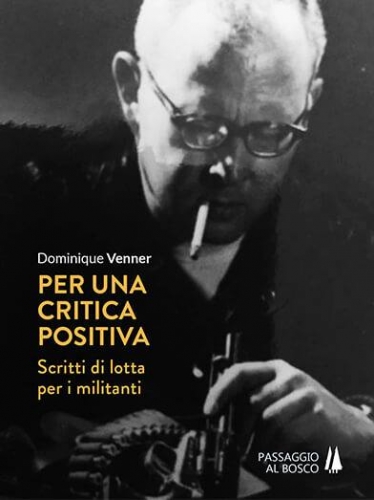

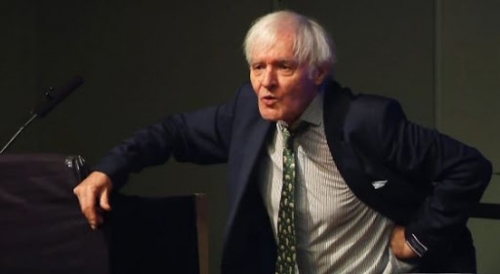

J’ai d’abord découvert Venner, l’expert en armement, avant de m’intéresser à son parcours politique et intellectuel. Pourtant « quel roman que (sa) vie ! » comme aurait dit Napoléon.

J’ai d’abord découvert Venner, l’expert en armement, avant de m’intéresser à son parcours politique et intellectuel. Pourtant « quel roman que (sa) vie ! » comme aurait dit Napoléon. Ayant étudié Marx et Lénine, il analyse le Communisme, qu’il combat depuis toujours, non seulement comme un programme politique, mais aussi comme une organisation que les militants nationalistes doivent imiter en se structurant intellectuellement.

Ayant étudié Marx et Lénine, il analyse le Communisme, qu’il combat depuis toujours, non seulement comme un programme politique, mais aussi comme une organisation que les militants nationalistes doivent imiter en se structurant intellectuellement. Après plusieurs colloques et sept numéros de « Cité-Liberté », l’institut se saborde en 1971.

Après plusieurs colloques et sept numéros de « Cité-Liberté », l’institut se saborde en 1971. Certains ont aussitôt parlé du « geste d’un déséquilibré ». Il n’en est rien : dans une lettre envoyée à ses amis de « Radio Courtoisie » et à Robert Ménard, qui la publiera dans « Boulevard Voltaire », il explique « croire nécessaire… devant des périls immenses pour sa patrie française et européenne…de se sacrifier pour rompre la léthargie qui nous accable ». Il déclare « offrir ce qui lui reste de vie dans une intention de protestation et de fondation ».

Certains ont aussitôt parlé du « geste d’un déséquilibré ». Il n’en est rien : dans une lettre envoyée à ses amis de « Radio Courtoisie » et à Robert Ménard, qui la publiera dans « Boulevard Voltaire », il explique « croire nécessaire… devant des périls immenses pour sa patrie française et européenne…de se sacrifier pour rompre la léthargie qui nous accable ». Il déclare « offrir ce qui lui reste de vie dans une intention de protestation et de fondation ».

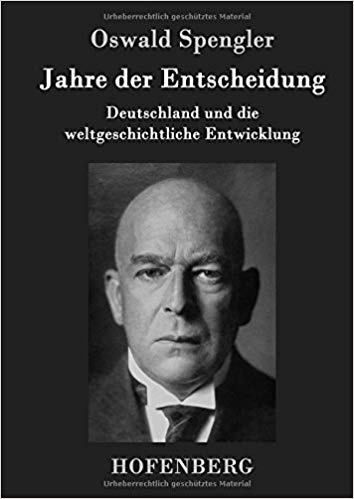

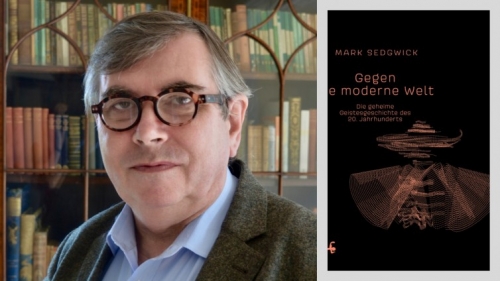

Influenced by the Konservative Revolution of pre-war Germany, particular the civilisational pessimism of Oswald Spengler, the merciless critique of liberal democracy assembled in the works of Carl Schmitt and the complex and hard to define body of work created by Ernst Junger, the Nouvelle Droite’s think tank GRECE (Groupement de Recherce et d’Études pour la Civilisation Européene, or Research and Study Group for European Civilisation) established itself, for a time, as an influential body on the French political scene.

Influenced by the Konservative Revolution of pre-war Germany, particular the civilisational pessimism of Oswald Spengler, the merciless critique of liberal democracy assembled in the works of Carl Schmitt and the complex and hard to define body of work created by Ernst Junger, the Nouvelle Droite’s think tank GRECE (Groupement de Recherce et d’Études pour la Civilisation Européene, or Research and Study Group for European Civilisation) established itself, for a time, as an influential body on the French political scene. Avowedly anti-capitalist, anti-American, anti-globalisation and pro-European unification, there is, unfortunately for the online censors, therefore very little evidence of Nouvelle Droite influences on Gove’s personal politics. Indeed, many of its lines of thought can be traced more clearly in European politicians as superficially distinct as Macron and Orban than in any British figure.

Avowedly anti-capitalist, anti-American, anti-globalisation and pro-European unification, there is, unfortunately for the online censors, therefore very little evidence of Nouvelle Droite influences on Gove’s personal politics. Indeed, many of its lines of thought can be traced more clearly in European politicians as superficially distinct as Macron and Orban than in any British figure. The European Union, similarly, links climate change to a

The European Union, similarly, links climate change to a  Indeed, Faye’s darkest warnings are echoed in British parliamentary politics only by the Green Party, one of whose most senior figures, the University of East Anglia’s professor of Philosophy and

Indeed, Faye’s darkest warnings are echoed in British parliamentary politics only by the Green Party, one of whose most senior figures, the University of East Anglia’s professor of Philosophy and  We should be pleased that our political representatives are reading offbeat ideas, not necessarily because they believe them, but because they represent the strange intellectual and political ferment of the early 21st century. The idea that There Is No Alternative to the neoliberal consensus is long gone. There are, if anything, too many alternatives, and they represent a future as dangerous as it is exciting.

We should be pleased that our political representatives are reading offbeat ideas, not necessarily because they believe them, but because they represent the strange intellectual and political ferment of the early 21st century. The idea that There Is No Alternative to the neoliberal consensus is long gone. There are, if anything, too many alternatives, and they represent a future as dangerous as it is exciting.

Russia has been hit by the pandemic in a relatively mild form. I can not say that the measures the government has undertaken were (or are) exceptionally good but the situation is nevertheless not as dramatic as elsewhere. From the end of March, Russia began to close its borders with the countries most affected by coronavirus. Putin then mildly suggested citizens stay home for one week in the end of March without explaining what the legal status of this voluntary measure actually was. A full lockdown followed in the region most affected by pandemic. At the first glance the measures of the government looked a bit confused: it seemed that Putin and others were not totally aware of the real danger of the coronavirus, perhaps suspecting that Western countries had some hidden agenda (political or economic). Nonetheless, reluctantly, the government has accepted the challenge and now most regions are in total lockdown.

Russia has been hit by the pandemic in a relatively mild form. I can not say that the measures the government has undertaken were (or are) exceptionally good but the situation is nevertheless not as dramatic as elsewhere. From the end of March, Russia began to close its borders with the countries most affected by coronavirus. Putin then mildly suggested citizens stay home for one week in the end of March without explaining what the legal status of this voluntary measure actually was. A full lockdown followed in the region most affected by pandemic. At the first glance the measures of the government looked a bit confused: it seemed that Putin and others were not totally aware of the real danger of the coronavirus, perhaps suspecting that Western countries had some hidden agenda (political or economic). Nonetheless, reluctantly, the government has accepted the challenge and now most regions are in total lockdown. On one hand, many experts claim that the disease has artificial origin and was leaked (accidently or on purpose) as an act of biological warfare. Precisely in Wuhan there is allegedly one of the top biological laboratories in China. In the US, many people, including President Trump, pursue this hypothesis or suggest this is all part of the plan of a select group of globalists (like Bill Gates, Zuckerberger, George Soros and so on) to expand the deadly virus in order to impose the vaccination and eventually introduce microchips into human beings around the world. The surveillance methods already introduced to control and monitor infected people and even those who are still healthy seem to confirm such fears. There is a conspiracy theory which suggests that China has been set up as a scapegoat. We might laugh at the inconsistency of such myths and their lack of proof, but belief in such theories – especially during moments of deep crises – are easily accepted and become the basis for real actions, and could even lead to war.

On one hand, many experts claim that the disease has artificial origin and was leaked (accidently or on purpose) as an act of biological warfare. Precisely in Wuhan there is allegedly one of the top biological laboratories in China. In the US, many people, including President Trump, pursue this hypothesis or suggest this is all part of the plan of a select group of globalists (like Bill Gates, Zuckerberger, George Soros and so on) to expand the deadly virus in order to impose the vaccination and eventually introduce microchips into human beings around the world. The surveillance methods already introduced to control and monitor infected people and even those who are still healthy seem to confirm such fears. There is a conspiracy theory which suggests that China has been set up as a scapegoat. We might laugh at the inconsistency of such myths and their lack of proof, but belief in such theories – especially during moments of deep crises – are easily accepted and become the basis for real actions, and could even lead to war.

Hinsichtlich der „Umvolkung“ oder des „Bevölkerungsaustausches“ sollte man darauf hinweisen, daß es dies immer schon gegeben hat und immer geben wird. Vor kurzem gab es mehrere kleine Bevölkerungs-Austauschaktionen im ehemaligen Jugoslawien, wobei viele Kroaten, muslimische Bosniaken und Serben in Bosnien ihre ehemaligen Wohnorte verlassen mußten. Vertreibung wäre hier ein besseres Wort für diese Aktion, da dieser Bevölkerungsaustausch in Ex-Jugoslawien mitten im Kriege stattgefunden hat.

Hinsichtlich der „Umvolkung“ oder des „Bevölkerungsaustausches“ sollte man darauf hinweisen, daß es dies immer schon gegeben hat und immer geben wird. Vor kurzem gab es mehrere kleine Bevölkerungs-Austauschaktionen im ehemaligen Jugoslawien, wobei viele Kroaten, muslimische Bosniaken und Serben in Bosnien ihre ehemaligen Wohnorte verlassen mußten. Vertreibung wäre hier ein besseres Wort für diese Aktion, da dieser Bevölkerungsaustausch in Ex-Jugoslawien mitten im Kriege stattgefunden hat. Deswegen ist jegliche Kritik an der Masseneinwanderung ohne eine vorhergehende Kritik am liberalen Handel bzw. am Kapitalismus sinnlos. Und umkehrt. Die kleinen kriminellen Migrantenschlepper, die meistens aus dem Balkan stammen, sind nur ein Abbild der großen Gutmenschen-Migrantenschlepper, die in unseren Regierungen sitzen. Auch unsere Politiker, ob sie in Brüssel oder in Berlin sitzen, befolgen nur die Regeln des freien Marktes.

Deswegen ist jegliche Kritik an der Masseneinwanderung ohne eine vorhergehende Kritik am liberalen Handel bzw. am Kapitalismus sinnlos. Und umkehrt. Die kleinen kriminellen Migrantenschlepper, die meistens aus dem Balkan stammen, sind nur ein Abbild der großen Gutmenschen-Migrantenschlepper, die in unseren Regierungen sitzen. Auch unsere Politiker, ob sie in Brüssel oder in Berlin sitzen, befolgen nur die Regeln des freien Marktes.  Natürlich könnte der heutige Bevölkerungsaustausch von jedem europäischen Staat jederzeit gestoppt oder auch rückgängig gemacht werden, solange Politiker Mut zur Macht haben, solange sie politische Entscheidungen treffen wollen, oder anders gesagt, solange sie die Entschlossenheit zeigen, den Zuzug der Migranten aufzuhalten.

Natürlich könnte der heutige Bevölkerungsaustausch von jedem europäischen Staat jederzeit gestoppt oder auch rückgängig gemacht werden, solange Politiker Mut zur Macht haben, solange sie politische Entscheidungen treffen wollen, oder anders gesagt, solange sie die Entschlossenheit zeigen, den Zuzug der Migranten aufzuhalten.

Demzufolge stellt sich die Frage, was bedeutet es heute, ein guter Europäer zu sein? Ist ein Bauer im ethnisch homogenen Rumänien oder Kroatien ein besserer Europäer, oder ist ein Nachkomme der dritten Generation eines Somaliers oder Maghrebiners, der in Berlin oder Paris wohnt, ein besserer Europäer?

Demzufolge stellt sich die Frage, was bedeutet es heute, ein guter Europäer zu sein? Ist ein Bauer im ethnisch homogenen Rumänien oder Kroatien ein besserer Europäer, oder ist ein Nachkomme der dritten Generation eines Somaliers oder Maghrebiners, der in Berlin oder Paris wohnt, ein besserer Europäer? Die einzige Waffe, sich gegen den heutigen Völkeraustausch zu wehren, liegt in der Wiedererweckung unseres biologisch-kulturellen Bewußtseins. Ansonsten werden wir weiterhin nur die hohlen Floskeln der christlichen, liberalen oder kommunistischen Multikulti-Ideologie wiederkäuen. So richtig es ist, die Antifa oder den Finanzkapitalismus anzuprangern, dürfen wir nicht vergessen, daß die christlichen Kirchen die eifrigsten Boten des großen Bevölkerungsaustauschs sind.

Die einzige Waffe, sich gegen den heutigen Völkeraustausch zu wehren, liegt in der Wiedererweckung unseres biologisch-kulturellen Bewußtseins. Ansonsten werden wir weiterhin nur die hohlen Floskeln der christlichen, liberalen oder kommunistischen Multikulti-Ideologie wiederkäuen. So richtig es ist, die Antifa oder den Finanzkapitalismus anzuprangern, dürfen wir nicht vergessen, daß die christlichen Kirchen die eifrigsten Boten des großen Bevölkerungsaustauschs sind.

E' un fenomeno irripetibile, inquadrabile in tutto e per tutto nel XX secolo e figlio della palingenesi collettiva della prima guerra mondiale, che forgiò una generazione in quella che Benito Mussolini definirà come “trincerocrazia”, mito fondativo di una nuova gioventù che tornava a casa dopo quattro anni di trincea. Il fascismo mussoliniano è figlio della Grande Guerra, l’evento che ha mutato per sempre la storia, l’Europa e il mondo, e senza la quale non avremmo avuto né il nazionalsocialismo in Germania né la Rivoluzione d'Ottobre in Russia. E' nel suo mezzo, e qui aveva ragione Ernst Nolte, che scoppia la “europäische Bürgerkrieg” (1917 - 1945) fra due diverse concezioni del mondo, fra quella materialista storica incarnata nel marxismo-leninismo a quella romantica, idealista e volontarista incarnata dai fascismi. E' quel carnaio a creare l'idea che sarebbe nata un’aristocrazia guerriera venuta fuori direttamente dalla gerarchia della trincea, la trincerocrazia, cioè

E' un fenomeno irripetibile, inquadrabile in tutto e per tutto nel XX secolo e figlio della palingenesi collettiva della prima guerra mondiale, che forgiò una generazione in quella che Benito Mussolini definirà come “trincerocrazia”, mito fondativo di una nuova gioventù che tornava a casa dopo quattro anni di trincea. Il fascismo mussoliniano è figlio della Grande Guerra, l’evento che ha mutato per sempre la storia, l’Europa e il mondo, e senza la quale non avremmo avuto né il nazionalsocialismo in Germania né la Rivoluzione d'Ottobre in Russia. E' nel suo mezzo, e qui aveva ragione Ernst Nolte, che scoppia la “europäische Bürgerkrieg” (1917 - 1945) fra due diverse concezioni del mondo, fra quella materialista storica incarnata nel marxismo-leninismo a quella romantica, idealista e volontarista incarnata dai fascismi. E' quel carnaio a creare l'idea che sarebbe nata un’aristocrazia guerriera venuta fuori direttamente dalla gerarchia della trincea, la trincerocrazia, cioè

Diverso il discorso della Nouvelle Droite o la Quarta Teoria Politica di Aleksandr Dugin, che è una riattualizzazione della konservative Revolution, che non punta alla creazione di uno stato totalitario (a differenza del fascismo, che è figlio della modernità) ma piuttosto organico, federale e continentale, pescando dal pre-moderno, dall'arcaismo, dal tradizionalismo, dai valori iperborei, dalle identità ancestrali che il cosiddetto "mondialismo", figlio della post-modernità, sta cancellando. L'alt-right invece è strettamente legata alla mentalità liberale e ai modelli di produzione capitalistici. Insomma, certi storici americani è meglio che studino altro!

Diverso il discorso della Nouvelle Droite o la Quarta Teoria Politica di Aleksandr Dugin, che è una riattualizzazione della konservative Revolution, che non punta alla creazione di uno stato totalitario (a differenza del fascismo, che è figlio della modernità) ma piuttosto organico, federale e continentale, pescando dal pre-moderno, dall'arcaismo, dal tradizionalismo, dai valori iperborei, dalle identità ancestrali che il cosiddetto "mondialismo", figlio della post-modernità, sta cancellando. L'alt-right invece è strettamente legata alla mentalità liberale e ai modelli di produzione capitalistici. Insomma, certi storici americani è meglio che studino altro!

Marco Fraquelli, autore del volume A destra di Porto Alegre. Perché la Destra è più no-global della Sinistra (Rubbettino, 2005) sottolinea – pur essendo egli stesso di sinistra e discepolo del politologo Giorgio Galli – che i movimenti noglobal, nati a Seattle nel 1999 e protagonisti di importanti battaglie storiche, come la nascita nel 2001 del Social Forum di Porto Alegre in contrapposizione al World Economic Forum di Davos, e la contestazione del G8 di Genova, tendono “a contestare la globalizzazione convinti comunque che si tratti di un fenomeno che, attraverso opportuni correttivi, possa virare verso orizzonti positivi”, “che possa esistere insomma una globalizzazione ‘dal volto umano’, che sia possibile in altri termini, definire e imporre una nuova governance (e questo spiega per esempio le istanze per l’applicazione della Tobin Tax, per la cancellazione del debito contratto dai Paesi poveri, ecc.)” (1): ciò mostra che questi movimenti accettano le implicazioni della globalizzazione, rifiutando solamente il lato economico (“la Sinistra ha come obiettivo la mondializzazione senza il mercato” scrive Jean-François Revel), essendo figli dell’universalismo.

Marco Fraquelli, autore del volume A destra di Porto Alegre. Perché la Destra è più no-global della Sinistra (Rubbettino, 2005) sottolinea – pur essendo egli stesso di sinistra e discepolo del politologo Giorgio Galli – che i movimenti noglobal, nati a Seattle nel 1999 e protagonisti di importanti battaglie storiche, come la nascita nel 2001 del Social Forum di Porto Alegre in contrapposizione al World Economic Forum di Davos, e la contestazione del G8 di Genova, tendono “a contestare la globalizzazione convinti comunque che si tratti di un fenomeno che, attraverso opportuni correttivi, possa virare verso orizzonti positivi”, “che possa esistere insomma una globalizzazione ‘dal volto umano’, che sia possibile in altri termini, definire e imporre una nuova governance (e questo spiega per esempio le istanze per l’applicazione della Tobin Tax, per la cancellazione del debito contratto dai Paesi poveri, ecc.)” (1): ciò mostra che questi movimenti accettano le implicazioni della globalizzazione, rifiutando solamente il lato economico (“la Sinistra ha come obiettivo la mondializzazione senza il mercato” scrive Jean-François Revel), essendo figli dell’universalismo. La nouvelle droite svilupperà le prime analisi sul mondialismo, che non declinerà mai nel cospirazionismo, descrivendolo come un tratto ontologico del capitalismo stesso, che per sua natura non può rimanere relegato entro i confini di un singolo Stato ma ha la tendenza a ‘mondializzarsi’. L’analisi del fenomeno viene fatta nel 1981 dall’esponente del Grece Guillaume Faye nel libro Le système à tuer les peuples (Il sistema per uccidere i popoli), dove l’autore, citando Weber, Schmitt, Habermas e la Scuola di Francoforte – ergo, non intellettuali di destra – spiega che dal 1945 si sarebbe sviluppato globalmente un Sistema, descritto in questi termini: “La caratteristica precipua del Sistema, che oggi esercita la sua azione alienante e repressiva in gradi diversi su tutti i popoli e tutte le culture, è in effetti quella di essere costituito da un insieme di strutture di potere – di carattere principalmente economico e culturale, ma anche direttamente politico, tramite le grandi potenze e le istituzioni internazionali – completamente inorganico, funzionante in modo meccanico, senza altro significato che la propria sopravvivenza ed espansione in vista di un’uscita definitiva dell’umanità dalla storia [...] le espressioni particolari del suo potere sociale sono [...] il monopolio dell’informazione e l’uso repressivo del potere culturale” (4). Una descrizione che ricorda la Megamacchina “tecno-socio-economica” analizzata negli anni Novanta da Serge Latouche, “un bolide che marcia a tutta velocità ma [che] ha perso il guidatore”, i cui effetti determinano “conseguenze distruttive non solo sulle culture nazionali, ma anche sul politico e, in definitiva, sul legame sociale, tanto al Nord quanto al Sud” (5). La principale arma usata dal Sistema per “uccidere l’anima” (l’identità) è una subdola forma di penetrazione culturale che omologa i costumi e, in conformità al vigente complesso economico, i consumi. Gli Stati Uniti, visto il loro carattere antitradizionale (è una nazione giovane nata dall’immigrazione e dal melting pot di popoli diversi fra loro) sono vittime stesse del Sistema da loro creato, che procede da solo per mezzo di una “classe tecnocratica cosmopolita” (manager, amministratori delegati, decisori finanziari) che dirige una politica ormai svuotata da ogni potere: “Contrariamente alle tesi marxiste, nessun ‘direttore d’orchestra’ più o meno occulto ci governa. Nessuna volontà coscientemente programmata anima l’insieme per mezzo di decisioni globali a lungo termine. Il potere tende a non aver più né ubicazione né volto; ma sono sorti poteri che ci circondano e ci fanno partecipare al nostro proprio asservimento. La ‘direzione’ delle società si effettua oggi al di fuori del concetto di Führung. Il Sistema funziona in gran parte per autoregolazione incitativa. I centri di decisione influiscono, tramite gli investimenti, le tattiche economiche e le tattiche tecnologiche, sulle forme di vita sociale senza che vi sia alcuna concertazione d’assieme. Strategie separate e sempre impostate sul breve termine si incontrano e convergono. Questa convergenza va nel senso del rafforzamento del Sistema stesso, della sua cultura mondialista, della sua sovranazionalità, così che il Sistema funziona per se stesso, senza altro fine che la propria crescita. Le sue istanze direttive molteplici decentrate, si confondono con la sua stessa struttura organizzativa. Imprese nazionali, amministrazioni statali, multinazionali, reti bancarie, organismi internazionali si ripartiscono tutti un potere frammentato. Eppure, a dispetto, o forse proprio a causa dei conflitti interni d’interessi, come la concorrenza commerciale, l’insieme risulta ordinato alla costruzione dello stesso mondo, dello stesso tipo di società, del predominio degli stessi valori. Tutto concorda nell’indebolire le culture dei popoli e le sovranità nazionali, e nello stabilire su tutta la Terra la stessa civilizzazione” (6). Il Sistema cancella i territori e le loro sovranità, modellandole così a immagine e somiglianza dell’unico sistema vincente, quello nordamericano: “Il mondialismo del Sistema non procede dunque per conquista o repressione degli insiemi territoriali e nazionali, ma per digestione lenta; diffonde le sue strutture materiali e mentali insediandole a lato e al di sopra dei valori nazionali e territoriali. Si ‘stabilisce’ come i quaccheri, senza tentare di irreggimentare direttamente, [...] parassitando i valori e le tradizioni di radicamento territoriale. La presa di coscienza del fenomeno si rivela di conseguenza difficile. Parallelamente alla loro formazione ‘nazionale’ i giovani dirigenti d’azienda del mondo intero hanno oggi bisogno, per vendersi e valorizzarsi, del diploma di una scuola americana. Niente di obbligatorio in questa procedura; ma poco a poco il valore di questo diploma americano e ‘occidentale’ soppianta gli insegnamenti nazionali, la cui credibilità deperisce. Un’istruzione economica mondiale unica vede allora la luce. Essa veicola naturalmente l’ideologia del Sistema” (7).

La nouvelle droite svilupperà le prime analisi sul mondialismo, che non declinerà mai nel cospirazionismo, descrivendolo come un tratto ontologico del capitalismo stesso, che per sua natura non può rimanere relegato entro i confini di un singolo Stato ma ha la tendenza a ‘mondializzarsi’. L’analisi del fenomeno viene fatta nel 1981 dall’esponente del Grece Guillaume Faye nel libro Le système à tuer les peuples (Il sistema per uccidere i popoli), dove l’autore, citando Weber, Schmitt, Habermas e la Scuola di Francoforte – ergo, non intellettuali di destra – spiega che dal 1945 si sarebbe sviluppato globalmente un Sistema, descritto in questi termini: “La caratteristica precipua del Sistema, che oggi esercita la sua azione alienante e repressiva in gradi diversi su tutti i popoli e tutte le culture, è in effetti quella di essere costituito da un insieme di strutture di potere – di carattere principalmente economico e culturale, ma anche direttamente politico, tramite le grandi potenze e le istituzioni internazionali – completamente inorganico, funzionante in modo meccanico, senza altro significato che la propria sopravvivenza ed espansione in vista di un’uscita definitiva dell’umanità dalla storia [...] le espressioni particolari del suo potere sociale sono [...] il monopolio dell’informazione e l’uso repressivo del potere culturale” (4). Una descrizione che ricorda la Megamacchina “tecno-socio-economica” analizzata negli anni Novanta da Serge Latouche, “un bolide che marcia a tutta velocità ma [che] ha perso il guidatore”, i cui effetti determinano “conseguenze distruttive non solo sulle culture nazionali, ma anche sul politico e, in definitiva, sul legame sociale, tanto al Nord quanto al Sud” (5). La principale arma usata dal Sistema per “uccidere l’anima” (l’identità) è una subdola forma di penetrazione culturale che omologa i costumi e, in conformità al vigente complesso economico, i consumi. Gli Stati Uniti, visto il loro carattere antitradizionale (è una nazione giovane nata dall’immigrazione e dal melting pot di popoli diversi fra loro) sono vittime stesse del Sistema da loro creato, che procede da solo per mezzo di una “classe tecnocratica cosmopolita” (manager, amministratori delegati, decisori finanziari) che dirige una politica ormai svuotata da ogni potere: “Contrariamente alle tesi marxiste, nessun ‘direttore d’orchestra’ più o meno occulto ci governa. Nessuna volontà coscientemente programmata anima l’insieme per mezzo di decisioni globali a lungo termine. Il potere tende a non aver più né ubicazione né volto; ma sono sorti poteri che ci circondano e ci fanno partecipare al nostro proprio asservimento. La ‘direzione’ delle società si effettua oggi al di fuori del concetto di Führung. Il Sistema funziona in gran parte per autoregolazione incitativa. I centri di decisione influiscono, tramite gli investimenti, le tattiche economiche e le tattiche tecnologiche, sulle forme di vita sociale senza che vi sia alcuna concertazione d’assieme. Strategie separate e sempre impostate sul breve termine si incontrano e convergono. Questa convergenza va nel senso del rafforzamento del Sistema stesso, della sua cultura mondialista, della sua sovranazionalità, così che il Sistema funziona per se stesso, senza altro fine che la propria crescita. Le sue istanze direttive molteplici decentrate, si confondono con la sua stessa struttura organizzativa. Imprese nazionali, amministrazioni statali, multinazionali, reti bancarie, organismi internazionali si ripartiscono tutti un potere frammentato. Eppure, a dispetto, o forse proprio a causa dei conflitti interni d’interessi, come la concorrenza commerciale, l’insieme risulta ordinato alla costruzione dello stesso mondo, dello stesso tipo di società, del predominio degli stessi valori. Tutto concorda nell’indebolire le culture dei popoli e le sovranità nazionali, e nello stabilire su tutta la Terra la stessa civilizzazione” (6). Il Sistema cancella i territori e le loro sovranità, modellandole così a immagine e somiglianza dell’unico sistema vincente, quello nordamericano: “Il mondialismo del Sistema non procede dunque per conquista o repressione degli insiemi territoriali e nazionali, ma per digestione lenta; diffonde le sue strutture materiali e mentali insediandole a lato e al di sopra dei valori nazionali e territoriali. Si ‘stabilisce’ come i quaccheri, senza tentare di irreggimentare direttamente, [...] parassitando i valori e le tradizioni di radicamento territoriale. La presa di coscienza del fenomeno si rivela di conseguenza difficile. Parallelamente alla loro formazione ‘nazionale’ i giovani dirigenti d’azienda del mondo intero hanno oggi bisogno, per vendersi e valorizzarsi, del diploma di una scuola americana. Niente di obbligatorio in questa procedura; ma poco a poco il valore di questo diploma americano e ‘occidentale’ soppianta gli insegnamenti nazionali, la cui credibilità deperisce. Un’istruzione economica mondiale unica vede allora la luce. Essa veicola naturalmente l’ideologia del Sistema” (7). Ergo, la nouvelle droite, grazie al volume di Guillaume Faye, de-ebraicizza e de-complottizza l’analisi sul mondialismo, anche se negli ambienti del radicalismo di destra il concetto continuava sovrapporsi alla retorica antigiudaica. Non è casuale che Orion, che nel decennio Novanta sarà Organo del Fronte antimondialista, nei primi anni di vita editoriale, e cioè fra il 1984 e il 1987 circa, userà ancora tematiche cospirazioni ste antigiudaiche pescate dai Protocolli dei Savi di Sion, denunciando alleanze occulte fra l’alta finanza, ovviamente ebraica, le organizzazioni massoniche con a capo il B’nai B’rith, e i numerosi circoli sionisti sparsi in tutto l’Occidente, descritti come “l’architrave del progetto mondialista” dato che sarebbero tutti “casa, borsa e Sinagoga” (8). Il sionismo e il mondialismo sarebbero quindi considerate le due facce della stessa medaglia: il sionismo è “una delle componenti più importanti [...] del discorso mondialista” si legge in Orion, “il sionismo [...] è genocida e razzista [...] oggi l’unico vero razzismo esistente al mondo è quello praticato dal sionismo nazionale e internazionale. Un razzismo che affonda le sue radici nella storia, nella cultura e nella religione ma, certamente, l’unico vero e identificabile potere razzista e genocida” (9).

Ergo, la nouvelle droite, grazie al volume di Guillaume Faye, de-ebraicizza e de-complottizza l’analisi sul mondialismo, anche se negli ambienti del radicalismo di destra il concetto continuava sovrapporsi alla retorica antigiudaica. Non è casuale che Orion, che nel decennio Novanta sarà Organo del Fronte antimondialista, nei primi anni di vita editoriale, e cioè fra il 1984 e il 1987 circa, userà ancora tematiche cospirazioni ste antigiudaiche pescate dai Protocolli dei Savi di Sion, denunciando alleanze occulte fra l’alta finanza, ovviamente ebraica, le organizzazioni massoniche con a capo il B’nai B’rith, e i numerosi circoli sionisti sparsi in tutto l’Occidente, descritti come “l’architrave del progetto mondialista” dato che sarebbero tutti “casa, borsa e Sinagoga” (8). Il sionismo e il mondialismo sarebbero quindi considerate le due facce della stessa medaglia: il sionismo è “una delle componenti più importanti [...] del discorso mondialista” si legge in Orion, “il sionismo [...] è genocida e razzista [...] oggi l’unico vero razzismo esistente al mondo è quello praticato dal sionismo nazionale e internazionale. Un razzismo che affonda le sue radici nella storia, nella cultura e nella religione ma, certamente, l’unico vero e identificabile potere razzista e genocida” (9).

Fondamentali poi i club internazionali politici, i quali ufficiosamente fungerebbero da cardine fra i vari “attori mondialisti”, quali la Trilateral Commission, il Bilderberg Group e il Club di Roma, a cui Orion dedica numerose analisi e, all’inizio, l’inserto Orion-finanza – diretto dal torinese Mario Borghezio, poi esponente della Lega Nord e tramite fra il Carroccio e il radicalismo di destra. Nell’ultimo fascicolo, il numero 4 del maggio 1986, Orion pubblica per la prima volta l’elenco dei membri della Trilateral Commission, organizzazione che prende il nome dalla teoria del suo ideologo, Zbigniw Brzezinsky, che teorizza la fine del bipolarismo indicando in “tre pilastri” – Usa, Giappone e Europa occidentale – gli attori di un progetto liberoscambista capace di avvicinare tali zone per poi unificare il sistema economico-finanziario. Grazie a pubblicazioni di questo tipo – nonostante persista una certa retorica antiebraica – Orion cerca di archiviare l’ormai vetusta e desueta teoria del ‘grande complotto’ a opera della “grande piovra ‘giudaico-massonica’ che manovrerebbe tutto. Descrivendo un vertice della Trilateral tenutosi a Madrid dopo la riunione del G7 a Tokyo a metà anni Ottanta, che vedeva riunite persone come David Rockfeller, Isamu Yamashita, Giovanni Agnelli, Zbigniew Brzezinski (ex consigliere di Jimmy Carter) e Robert McNamara, tutti interessati alla Spagna soprattutto dopo il suo ingresso nella Comunità europea per il suo ruolo strategico (“trampolino di lancio per la strategia mondialista americana”) per le sue relazioni coi Paesi arabi, il Nord Africa e l’America Latina, ruolo svolto precedentemente dal Giappone per l’Europa, Murelli scriverà: “Chi oggi si domanda come sia stata possibile l’espansione dell’industria giapponese in così breve tempo, trova in questa autorevole dichiarazione la risposta al quesito”. La Trilateral Commission “sta soppiantando le vecchie strutture mondialiste quali la Massoneria”. Infatti, continua Murelli, “è forse un caso che la politica finanziaria nazionale di questi ultimi tempi ha come chiodo fisso, per esempio, l’internazionalizzazione non solo dei capitali, ma anche e soprattutto delle imprese e della produzione? È forse un caso che se mentre colano a picco personaggi come Calvi e Sindona emergono i vari De Benedetti, Berlusconi, Agnelli ecc.? È forse un caso che proprio Agnelli si sia battuto affinché l’affare Sirwkoski fosse vantaggioso per un’impresa americana piuttosto che da un’impresa italiana? E ancora: è un caso che l’Avvocato sostenga l’acquisto di Alfa Romeo da parte della Ford, azienda automobilistica che attraverso la sua Fondazione – ma guarda caso! – assieme alla Lilly Endowment, alla Rockfeller Brothers Fund e alla Kattering Fondation ha, fin dall’inizio, costituito una delle principali fonti di finanziamento della Trilateral?” (16).