lundi, 08 avril 2013

Pulp Fascism

Pulp Fascism

By Jonathan Bowden

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Editor’s Note:

The following text is a transcription by V. S. of a lecture entitled “Léon Degrelle and the Real Tintin,” delivered at the 21st meeting of the New Right, London, June 13, 2009. The lecture can be viewed on YouTube here [2]. (Please post any corrections as comments below.)

I have given it a new title because it serves as the perfect introduction to a collection of Bowden’s essays, lectures, and interviews entitled Pulp Fascism: Right-Wing Themes in Comics, Graphic Novels, and Popular Literature, which is forthcoming from Counter-Currents.

I proposed this collection and title to Bowden in 2011, and although he wrote a number of pieces especially for it, the project was unfinished at his death. We are bringing out this book in honor of the first anniversary of Bowden’s death on March 29, 2012.

I would like to talk about something that has always interested me. The title of the talk is “Léon Degrelle and the Real Tintin,” but what I really want to talk about is the heroic in mass and in popular culture. It’s interesting to note that heroic ideas and ideals have been disprivileged by pacifism, by liberalism tending to the Left and by feminism particularly since the social and cultural revolutions of the 1960s. Yet the heroic, as an imprimatur in Western society, has gone down into the depths, into mass popular culture. Often into trashy forms of culture where the critical insight of various intellectuals doesn’t particularly gaze upon it.

I would like to talk about something that has always interested me. The title of the talk is “Léon Degrelle and the Real Tintin,” but what I really want to talk about is the heroic in mass and in popular culture. It’s interesting to note that heroic ideas and ideals have been disprivileged by pacifism, by liberalism tending to the Left and by feminism particularly since the social and cultural revolutions of the 1960s. Yet the heroic, as an imprimatur in Western society, has gone down into the depths, into mass popular culture. Often into trashy forms of culture where the critical insight of various intellectuals doesn’t particularly gaze upon it.

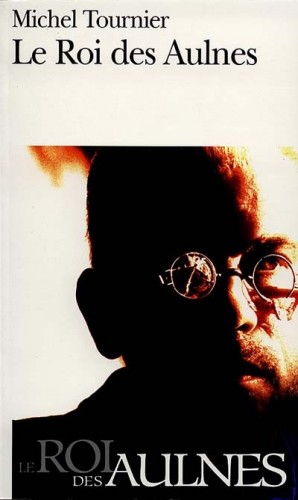

One of the forms that interests me about the continuation of the heroic in Western life as an idea is the graphic novel, a despised form, particularly in Western Europe outside France and Italy and outside Japan further east. It’s regarded as a form primarily for children and for adolescents. Yet forms such as this: these are two volumes of Tintin which almost everyone has come across some time or other. These books/graphic novels/cartoons/comic books have been translated into 50 languages other than the original French. They sold 200 million copies, which is almost scarcely believable. It basically means that a significant proportion of the globe’s population has got one of these volumes somewhere.

Now, before he died, Léon Degrelle said that the character of Tintin created by Hergé was based upon his example. Other people rushed to say that this wasn’t true and that this was self-publicity by a notorious man and so on and so forth. Probably like all artistic and semi-artistic things there’s an element of truth to it. Because a character like this that’s eponymous and archetypal will be a synthesis of all sorts of things. Hergé got out of these dilemmas by saying that it was based upon a member of his family and so on. That’s probably as true as not.

The idea of the masculine and the heroic and the Homeric in modern guise sounds absurd when it’s put in tights and appears in a superhero comic and that sort of thing. But the interesting thing is because these forms of culture are so “low” they’re off the radar of that which is acceptable and therefore certain values can come back. It’s interesting to note that the pulp novels in America in the 1920s and ’30s, which preceded the so-called golden age of comics in the United States in the ’30s and ’40s and the silver age in the 1960s, dealt with quite illicit themes.

One of the reasons that even today Tintin is mildly controversial and regarded as politically incorrect in certain circles is they span much of the 20th century. Everyone who is alive now realizes that there was a social and cultural revolution in the Western world in the 1960s, where almost all the values of the relatively traditional European society, whatever side you fought on in the Second World War, were overturned and reversed in a mass reversion or re-evaluation of values from a New Leftist perspective.

Before 1960, many things which are now legal and so legal that to criticize them has become illegal were themselves illicit and outside of the pedigree and patent of Western law, custom, practice, and social tradition. We’ve seen a complete reversal of nearly all of the ideals that prevailed then. This is why many items of quite popular culture are illicit.

If one just thinks of a silent film like D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation in 1915. There was a prize awarded by the American Motion Picture Academy up until about 1994 in Griffith’s name. For those who don’t know, the second part of Birth of a Nation is neo-Confederate in orientation and depicts the Ku Klux Klan as heroic. Heroic! The Ku Klux Klan regarded as the hero, saving the White South from perdition, from the carpet-baggers, some of whom bear an extraordinary resemblance to the present President of the United States of America. Of course, they were called carpet-baggers because they were mulatto politicians who arrived in the South primarily from the North with certain Abolitionist sponsorship and they arrived with everything they owned in a carpet bag to take over. And that’s why they were called that.

That film, which you can get in any DVD store and buy off Amazon for ten pounds or so, is extraordinarily notorious, but in actual fact, in terms of its iconography, it’s a heroic, dualist film where there’s a force of darkness and a force of light. There’s a masculine individual. There’s people who believe that they’ll sort out problems with a gun. The Bible, in an ultra-Protestant way, is their text. It’s what they base metaphysical objectivism and absolute value upon, and that film is perceived retrospectively as an extreme White Right-wing film although Griffith himself is later to do a film called Intolerance and actually, like a lot of film makers, had quite a diverse range of views irrespective of his own Southern and Texan background.

The thing one has to remember is that the methodology of the heroic can survive even if people fight against various forces in Western life. One of the great tricks of the heroic in the last 40 to 50 years is the heroic films involving icons like Clint Eastwood, for example, as a successor to this sort of archetype of John Wayne and the sort of Western stylized masculinity that he represented. Eastwood often plays individualistic, survivalist, and authoritarian figures; Right-wing existentialist figures. But they’re always at war with bureaucracies and values that are perceived as conservative. One of the ways it tricks, which has occurred since the 1960s, is to reorient the nature of the heroic so that the eternal radical Right within a society such as the United States or elsewhere is the enemy, per se.

There’s a comic strip in the United States called Captain America which began in the 1940s. Captain America is a weedy young man who almost walks with a stick and has arms like branches, and of course a friendly American scientist introduces him to a new secret program where he’s injected with some steroids and this sort of thing and immediately becomes this enormous blond hulking superman with blue eyes. Of course, he must dress himself in the American flag so that he can call himself Captain America. So you get the idea! He has a big shield which has the star of the United States on it and has a sidekick who dies in one of the 1940s comics, but of course these figures never die. They’re endlessly brought back. But there’s a problem here because the position that Captain America and a lesser Marvel Comics equivalent called Captain Britain and all these other people represent is a little bit suspect in an increasingly liberal society, even then. So, his enemy, his nemesis, his sort of dualist alternative has to be a “Nazi,” and of course Captain America has a Nazi enemy who’s called the Red Skull.

The Red Skull is a man with a hideous face who, to hide this hideousness, wears a hideous mask over his hideous face as a double take. The mirror cracks so why not wear a mask, but it’s not a mask of beauty. It’s a skull that’s painted red, and he’s called the Red Skull. He always wears green. So, it’s red and green. He always appears and there’s always a swastika somewhere in the background and that sort of thing. He’s always building robots or cyborgs or new biological sorts of creatures to take over the world. Captain America always succeeds in vanquishing him in the last panel. Just in the last panel. The Red Skull’s always about to triumph until the fist of Captain America for the American way and the American dream comes in at the end.

This mantle of the heroic whereby Right-wing existentialists like Captain America fight against the extreme Right in accordance with democratic values is one of the interesting tricks that’s played with the nature of the heroic. Because the heroic is a dangerous idea. Whether or not Tintin was based on Léon Degrelle there is of course a fascistic element to the nature of the heroic which many writers of fantasy and science fiction, which began as a despised genre but is now, because it’s so commercially viable, one of the major European book genres.

They’ve always known this. Michael Moorcock, amongst others, speaks of the danger of subliminal Rightism in much fantasy writing where you can slip into an unknowing, uncritical ultra-Right and uncritical attitude towards the masculine, towards the heroic, towards the vanquishing of forces you don’t like, towards self-transcendence, for example.

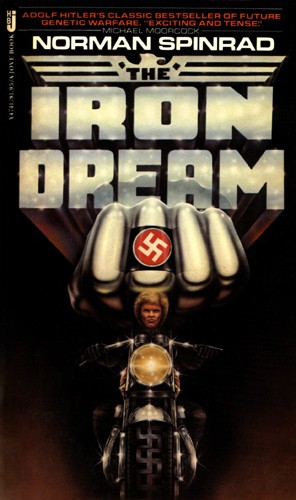

There’s a well-known novel called The Iron Dream and this novel is in a sense depicting Hitler’s rise to power and everything that occurred in the war that resulted thereafter as a science fiction discourse, as a sort of semiotic by a mad creator. This book was actually banned in Germany because although it’s an extreme satire, which is technically very anti-fascistic, it can be read in a literal-minded way with the satire semi-detached. This novel by Norman Spinrad was banned for about 20 to 30 years in West Germany as it then was. Because fantasy enables certain people to have an irony bypass.

There’s a well-known novel called The Iron Dream and this novel is in a sense depicting Hitler’s rise to power and everything that occurred in the war that resulted thereafter as a science fiction discourse, as a sort of semiotic by a mad creator. This book was actually banned in Germany because although it’s an extreme satire, which is technically very anti-fascistic, it can be read in a literal-minded way with the satire semi-detached. This novel by Norman Spinrad was banned for about 20 to 30 years in West Germany as it then was. Because fantasy enables certain people to have an irony bypass.

Although comics are quite humorous, particularly to adults, children and adolescents read them, scan them because they sort of just look at the images and take in the balloons as they go across because these are films on paper. They essentially just scan them in an uncritical way. If you ever look at a child, particularly a child that’s got very little interest in formal literature of a sort that’s taught in many European and American schools, they sit absorbed before comics, they’re absolutely enthralled by the nature of them, by the absolute villainy of the transgressor, by the total heroicism and absence of irony and sarcasm of the heroic figure with a scantily clad maiden on the front that the hero always addresses himself to but usually in a dismissive way because he’s got heroic things to accomplish. She’s always on his arm or on his leg or being dragged down.

Indeed, the pulp depiction of women which, of course, is deeply politically incorrect and vampish is a sort of great amusement in these genres. If you ever look at comics like Conan the Barbarian or Iron Man or The Incredible Hulk and these sorts of things the hero will always be there in the middle! Never to the side. Always in the middle foursquare facing the future. The villain will always be off to one side, often on the left; the side of villainy, the side of the sinister, that which wants to drag down and destroy.

As the Hulk is about to hit The Leader, which is his nemesis, or Captain America is about to hit the Red Skull, which is his nemesis, or Batman is about to hit the psychiatric clown called The Joker, who is his nemesis, there’s always a scantily clad woman who’s around his leg on the front cover looking up in a pleading sort of way as the fist is back here. It’s quite clear that these are archetypal male attitudes of amusement and play which, of course, have their danger to many of the assumptions that took over in the 1960s and ’70s.

It’s interesting to notice that in the 1930s quite a lot of popular culture expressed openly vigilante notions about crime. There was a pulp magazine called The Shadow that Orson Welles played on the radio. Orson Welles didn’t believe in learning the part, in New York radio Welles, usually the worse for wear for drink and that sort of thing, would steam up to the microphone, he would take the script, and just launch into The Shadow straight away. The Shadow used to torment criminals. Depending on how nasty they were the more he’d torment them. When he used to kill them, or garrote them, or throttle them, or hang them (these pulps were quite violent and unashamedly so) he used to laugh uproariously like a psychopath. And indeed, if you didn’t get the message, there would be lines in the book saying “HA HA HA HA HA!” for several lines as he actually did people in.

The Shadow is in some ways the prototype for Batman who comes along later. Certain Marxian cultural critics in a discourse called cultural studies have pointed out that Batman is a man who dresses himself up in leathers to torment criminals at night and looks for them when the police, namely the state, the authority in a fictional New York called Gotham City, put a big light in the sky saying come and torment the criminal class. They put this big bat symbol up in the sky, and he drives out in the Batmobile looking for villains to torment. As most people are aware, comics morphed into more adult forms in the 1980s and ’90s and the graphic novel emerged called Dark Knight which explored in quite a sadistic and ferocious way Batman’s desire to punish criminality in a very extreme way.

There was also a pulp in the 1930s called Doc Savage. Most people are vaguely aware of these things because Hollywood films have been made on and off about all these characters. Doc Savage was an enormous blond who was 7 feet. He was bronzed with the sun and covered in rippling muscles. Indeed, to accentuate his musculature he wore steel bands around his wrists and ankles, as you do. He was a scientific genius, a poetic genius, and a musical genius. In fact, there was nothing that he wasn’t a genius at. He was totally uninterested in women. He also had a research institute that operated on the brains of criminals in order to reform them. This is quite extraordinary and deeply politically incorrect! He would not only defeat the villain but at the end of the story he would drag them off to this hospital/institute for them to be operated on so that they could be redeemed for the nature of society. In other words, he was a eugenicist!

Of course, those sorts of ideas in the 1930s were quite culturally acceptable because we are bridging different cultural perceptions even at the level of mass entertainment within the Western world. That which is regarded, even by the time A Clockwork Orange was made by Kubrick from Burgess’ novel in the 1970s, as appalling, 40 years before was regarded as quite acceptable. So, the shifting sands of what is permissible, who can enact it, and how they are seen is part and parcel of how Western people define themselves.

Don’t forget, 40% of the people in Western societies don’t own a book. Therefore, these popular, mass forms which in one way are intellectually trivial is in some respects how they perceive reality.

Comics, like films, have been heavily censored. In the United States in the 1950s, there was an enormous campaign against various sorts of quasi-adult comics that were very gory and were called horror comics and were produced by a very obscure forum called Entertainment Comics (EC). And there was a surrogate for the Un-American Activities Committee in the US Senate looking at un-American comics that are getting at our kids, and they had a large purge of these comics. Indeed, mountains of them were burnt. Indeed, enormous sort of semi-book burnings occurred. Pyramids of comics as big as this room would be burnt by US and federal marshals on judges’ orders because they contained material that the young shouldn’t be looking at.

The material they shouldn’t be looking at was grotesque, gory, beyond Roald Dahl sort of explicit material which, of course, children love. They adore all that sort of thing because it’s exciting, because it’s imaginative, because it’s brutal, because it takes you out of the space of normalcy, and that’s why the young with their instincts and their passion and glory love this sort of completely unmediated amoral fare. That’s why there’s always been this tension between what their parents would like them to like and what many, particularly late childish boys and adolescents, really want to devour. I remember Evelyn Waugh was once asked, “What was your favorite book when you were growing up?” And just like a flash he said, “Captain Blood!” Captain Blood! Imagine any silent pirate film from the 1920s and early ’30s.

Now, the heroic in Western society takes many forms. When I grew up, there were these tiny little comics in A5 format. Everyone must have seen them. Certainly any boys from the 1960s and ’70s. They were called Battle. Battle and Commando and War comics, and these sorts of thing. They were done by D. C. Thomson, which is the biggest comics manufacturer in Britain, up in Dundee. These comics were very unusual because they allowed extremely racialist and nationalist attitudes, but the enemies were always Germans and they were always Japanese.

Indeed, long after the passing of the Race Act in the late 1960s and its follow-up which was more codified and definitive and legally binding in the 1970s, statements about Germans and Japanese could be made in these sorts of comics, which were not just illicit but illegal. You know what I mean, the Green Berets, the commandos, would give it to “Jerry” in a sort of arcane British way and were allowed to. This was permitted, even this liberal transgression, because the enemy was of such a sort.

But, of course, what’s being celebrated is British fury and ferocity and the nature of British warriors and the Irish Guards not taking prisoners and this sort of thing. This is what’s being celebrated in these sorts of comics. It’s noticeable that D. C. Thomson, who has no connection to the DC group in the United States by the way, toned down this element in the comics as they went along. Only Commando survives, but they still produce four of them a month.

In the 1970s, Thomson, who also did The Beano and utterly childish material for children for about five and six as well as part of the great spectrum of their group, decided on some riskier, more transgressive, more punkish, more adult material. So, they created a comic called Attack. Attack! It’s this large shark that used to come and devour people. It was quite good. The editor would disapprove of something and they would be eaten by the shark. There was the marvelous balloons they have in comics, something like, “This shark is amoral. It eats.” And there would be a human leg sticking out of the mouth of the shark. Some individual the editor disapproved of was going down the gullet.

Now, Attack was attacked in Parliament. A Labour MP got up and said he didn’t like Attack. It was rather dubious. It was tending in all sorts of unwholesome directions, and Attack had a story that did outrage a lot of people in the middle 1970s, because there was a story where a German officer from the Second World War was treated sympathetically, in Attack. Because it was transgressive, you see. What’s going to get angry Methodists writing to their local paper? A comic that treats some Wehrmacht officer in a sympathetic light. So, there was a real ruckus under Wilson’s government in about ’75 about this, and so they removed that.

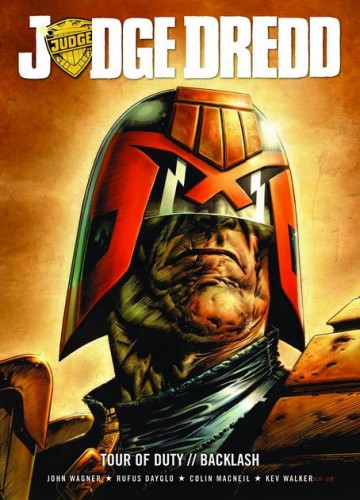

Various writers like Pat Mills and John Wagner were told to come up with something else. So, they came up with the comic that became Judge Dredd. Judge Dredd is a very interesting comic in various ways because all sorts of Left-wing people don’t like Judge Dredd at all, even as a satire. If there are people who don’t know this, Dredd drives around in a sort of motorcycle helmet with a slab-sided face which is just human meat really, and he’s an ultra-American. It’s set in a dystopian future where New York is extended to such a degree that it covers about a quarter of the landmass of the United States. You just live in a city, in a burg, and you go and you go and you go. There’s total collapse. There’s no law and order, and there’s complete unemployment, and everyone’s bored out of their mind.

Various writers like Pat Mills and John Wagner were told to come up with something else. So, they came up with the comic that became Judge Dredd. Judge Dredd is a very interesting comic in various ways because all sorts of Left-wing people don’t like Judge Dredd at all, even as a satire. If there are people who don’t know this, Dredd drives around in a sort of motorcycle helmet with a slab-sided face which is just human meat really, and he’s an ultra-American. It’s set in a dystopian future where New York is extended to such a degree that it covers about a quarter of the landmass of the United States. You just live in a city, in a burg, and you go and you go and you go. There’s total collapse. There’s no law and order, and there’s complete unemployment, and everyone’s bored out of their mind.

The comic is based on the interesting notion that crime is partly triggered by boredom and a sort of wantonness in the masses. Therefore, in order to keep any sort of order, the police and the judiciary have combined into one figure called a Judge. So, the jury, the trial, the police investigation, and the investigative and forensic elements are all combined in the figure of the Judge. So, if Judge Dredd is driving along the street and he sees some youths of indeterminate ethnicity breaking into a store he says, “Hold, citizens! This is the law! I am the law! Obey me! Obey the law!” And if they don’t, he shoots them dead, because the trial’s syncopated into about 20 seconds. He’s given them the warning. That’s why he’s called Judge Dredd, you see. D-R-E-D-D. He just kills automatically those who transgress.

There’s great early comic strips where he roars around on this bike that has this sort of skull-like front, and he appears and there’s a chap parking his car and he says, “Citizen! Traffic violation! Nine years!” and roars off somewhere else. Somebody’s thieving or this sort of thing and he gets them and bangs their head into the street. There’s no question of a commission afterwards. “Twelve years in the Cube!” which is an isolation cell. It’s got its own slang because comics, of course, create their own world which children and adolescents love so you can totally escape into a world that’s got a semi-alternative reality of its own that’s closed to outsiders. If some adult picks it up and looks at it he says, “What is this about?” Because it’s designed to exclude you in a way.

Dredd has numerous adventures in other dimensions and so on, but Dredd never changes, never becomes more complicated, remains the same. He has no friends. “I have no need of human attachments,” he once says in a slightly marvelous line. He has a robot for company who provides most of his meals and needs and that sort of thing. For the rest, he’s engaged in purposeful and pitiless implementation of law and order. One of his famous phrases was when somebody asked him what is happiness, and he says in one of those bubbles, “Happiness is law and order.” Pleasure is obeying the law. And there are various people groveling in chains in front of him or something.

Now, there’ve been worried Left-wing cat-calls, although it’s a satire, and it’s quite clearly meant to be one. For example, very old people, because people in this fantasy world live so long that they want to die at the end, and they go to be euthanized. So, they all queue up for euthanasia. There’s one story where somebody blows up the people waiting for euthanasia to quicken the thing, but also to protest against it. And Judge says, “Killing euthanized is terrorism!” War on terror, where have we heard that before? Don’t forget, these are people that want to die. But Dredd says, “They’re being finished off too early. You’ve got to wait, citizen!” Wait to be killed later by the syringe that’s coming. And then people are reprocessed as medicines, because everything can be used. It’s a utilitarian society. Therefore, everything is used from birth to death, because the state arranges everything for you, even though socialism is condemned completely.

There’s another bloc, it’s based on the Cold War idea, there’s a Soviet bloc off on the other side of the world that is identical to the West, but ideologically they’re at war with each other, even though they’re absolutely interchangeable with each other. But the Western metaphysic is completely free market, completely capitalist, but in actual fact no one works, and everyone’s a slave to an authoritarian state.

There’s also an interesting parallel with more advanced forms of literature here. A Clockwork Orange: many people think that’s about Western youth rebellion and gangs of the Rockers and Mods that emerged in the 1960s at the time. Burgess wrote his linguistically sort of over-extended work in many ways. In actual fact, Anthony Burgess wrote A Clockwork Orange after a visit to the Soviet Union where he was amazed to find that, unlike the totalitarian control of the masses which he expected at every moment, there was quite a degree of chaos, particularly amongst the Lumpenproletariat in the Soviet Union.

George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four has an interesting idea, and that is that the proles are so beneath ideology, right at the bottom of society, the bottom 3% not even the bottom 10%, that they can be left to their own devices. They can be left to take drugs. They can be left to drink to excess. They can be left to destroy themselves. Orwell says “the future is the proles” at one point. Remember when Winston Smith looks out across the tenements and sees the enormous washerwoman putting some shirts, putting some sheets on a line? And she sings about her lost love, “Oh, he was a helpless fancy . . .” and all this. And Winston looks out on her across the back yards and lots and says, “If there’s a future, it lies with the proles!” And then he sings to himself, “But looking at them, he had to wonder.”

The party degrades the proletariat to such a degree that it ceases to be concerned about their amusements because they’re beneath the level of ideology and therefore you don’t need to control them. The people you control are the Outer Party, those who can think, those who wear the blue boiler suits, not the black ones from the Inner Party.

This interconnection between mass popular culture, often of a very trivial sort, and elitist culture, whereby philosophically the same ideas are expressed, is actually interesting. You sometimes get these lightning flashes that occur between absolutely sort of “trash culture,” if you like, and quite advanced forms of culture like A Clockwork Orange, like Darkness at Noon, like Nineteen Eighty-Four, like The Iron Heel, like The Iron Dream. And these sorts of extraordinary dystopian and catatopian novels, which are in some respects the high political literature (as literature, literature qua literature) of the 20th century.

This interconnection between mass popular culture, often of a very trivial sort, and elitist culture, whereby philosophically the same ideas are expressed, is actually interesting. You sometimes get these lightning flashes that occur between absolutely sort of “trash culture,” if you like, and quite advanced forms of culture like A Clockwork Orange, like Darkness at Noon, like Nineteen Eighty-Four, like The Iron Heel, like The Iron Dream. And these sorts of extraordinary dystopian and catatopian novels, which are in some respects the high political literature (as literature, literature qua literature) of the 20th century.

Now, one of the reasons for the intellectual independence of elements in some comics is because no one’s concerned about it except when the baleful eye of censorship falls upon them. A particular American academic wrote a book in the early 1950s called Seduction of the Innocent which is about how children were being depraved by these comics which were giving them violent and racialist and elitist and masculinist stereotypes, which shouldn’t be allowed.

Of course, a vogue for Left wing comics grew up in the 1970s because culture in the United States, particularly men’s culture, is racially segregated in a way which is never admitted. African-Americans have always had their own versions of these things. There are Black American comics. Marvel did two called The Black Panther, and the Black Panther only ever preys on villains who are Black.

There’s another one called Power Man who’s in prison loaded down with chains and a White scientist, who might be Jewish, experiments on him. He’s called Luke Cage and he’s experimented on so he becomes a behemoth. A titan of max strength he’s called, and he bats down the wall and takes all sorts of people on. And yet, of course, all of the villains he takes on, very like the Shaft films which are both about James Bond films which are very similar, all of this material is segregated. It occurs within its own zone.

But you notice the same heroic archetypes return. Yet again there’s a villain in the corner, usually on the left side, Luke Cage has an enormous fist, there’s a sort of half-caste beauty on his leg looking up, staring at him. This sort of thing. It’s the same main methodology. It’s the same thing coming around again.

Although there have been attempts at the Left-wing comic, it’s actually quite difficult to draw upon with any effect. Because, in a way you can criticize comics that are metapolitically Right-wing, but to create a Left-wing one is actually slightly difficult. The way you get around it is to have a comic that’s subliminally Rightist and have the villain who’s the extreme Right. There are two American comics called Sgt. Fury and Sgt. Rock and another one’s called Our Army at War. Sgt. Rock, you know, and this sort of thing. And you know who the villain is because they’re all sort in the Second World War.

The attitude towards Communism in comics is very complicated. Nuclear destruction was thought too controversial. When formal censorship of comics began in America in the 1950s something called the Approved Comics Code Authority, very like the British Board of Film Classification, emerged. They would have a seal on the front of a comic. Like American films in the 1930s, men and women could kiss but only in certain panels and only for a certain duration on the page as the child or adolescent looked at it, and it had to be, it was understood so explicitly it didn’t even need to be mentioned that of course it didn’t even need to be mentioned that it was totally heterosexual. Similarly, violence had to be kept to a minimum, but a certain allowed element of cruelty was permitted if the villain was on the receiving end of it.

Also, the comics had to be radically dualist. There has to be a force for light and a force for darkness. There has to be Spiderman and his nemesis who’s Dr. Octopus who has eight arms. But certain complications can be allowed, and as comics grow, if you like, non-dualist characters emerge.

There’s a character in The Fantastic Four called Doctor Doom who’s a tragic figure with a ruined face who is shunned by man who wants to revenge himself on society because he’s shut out, who ends as the ruler of a tiny little made-up European country which he rules with an iron hand, and he does have hands of iron. So he rules his little Latvia substitute with an iron hand. But he’s an outsider, you see, because in the comic he’s a gypsy, a sort of White Roma. But he gets his own back through dreams of power.

There’s these marvelous lines in comics which when you ventilate them become absurd. But on the page, if you’re sucked into the world, particularly as an adolescent boy, they live and thrive for you. Doom says to Reed Richards, who’s his nemesis on the other side, “I am Doom! I will take the world!” Because the way the hero gets back at the villain is to escape, because they’re usually tied up somewhere with a heroine looking on expectantly. The hero is tied up, but because the villain talks so much about what they’re going to do and the cruelty and appalling suffering they’re going to inflict all the time the hero is getting free. Because you have to create a lacuna, a space for the hero to escape so that he can drag the villain off to the asylum or to the gibbet or to the prison at the end. Do you remember that line from Lear on the heath? “I shall do such things, but what they are I know not! But they will be the terror of the earth!” All these villains repeat that sort of line in the course of their discourse, because in a sense they have to provide the opening or the space for the hero to emerge.

One of the icons of American cinema in the 20th century was John Wayne. John Wayne was once interviewed about his political views by, of all things, Playboy magazine. This is the sort of level of culture we’re dealing with. They said, “What are your political views?” and Wayne said, “Well, I’m a white supremacist.” And there was utter silence when he said this! He was a member of the John Birch Society at the time. Whether or not he gave money to the Klan no one really knows.

There’s always been a dissident strand in Hollywood, going back to Errol Flynn and before, of people who, if you like, started, even at the level of fantasy, living out some of these heroic parts in their own lives. Wayne quite clearly blurred the distinction between fantasy on the film set and in real life on many occasions. There are many famous incidents of Wayne, when robberies were going on, rushing out of hotels with guns in hand saying, “Stick’em up!” He was always playing that part, because every part’s John Wayne isn’t it, slightly differently? Except for a few comedy pieces. And he played that part again and again and again.

Don’t forget, The Alamo is now a politically incorrect film. Very politically incorrect. There’s an enormous women’s organization in Texas called the Daughters of the Alamo, and they had to change their name because the White Supremacist celebration of the Alamo was offensive to Latinos who are, or who will be very shortly, a Texan majority don’t forget. So, the sands are shifting in relation to what is permitted even within popular forms of culture.

Don’t forget, The Alamo is now a politically incorrect film. Very politically incorrect. There’s an enormous women’s organization in Texas called the Daughters of the Alamo, and they had to change their name because the White Supremacist celebration of the Alamo was offensive to Latinos who are, or who will be very shortly, a Texan majority don’t forget. So, the sands are shifting in relation to what is permitted even within popular forms of culture.

When Wayne said he was a supremacist in that way he said, “I have nothing against other people, but we shouldn’t hand the country over to them.” That’s what he said. “We shouldn’t hand the country over to them.”

And don’t forget, I was born in ’62. Obama in many of the deep Southern states wouldn’t have had the vote then. Now he’s President. This is how the West is changing on all fronts and on every front. American Whites will certainly be in the minority throughout the federation in 40 or 50 years. Certainly. Indeed, Clinton (the male Clinton, the male of the species) once justified political correctness by saying, “Well, in 50 years we’ll be the minority. We’ll need political correctness to fight that game.”

The creator of Tintin, Hergé, always said that his dreams and his nightmares were in white. But we know that the politically correct games of the future will be Whites putting their hands up in the air complaining because somebody’s made a remark, complaining because they haven’t got a quota, complaining because this form is biased against them, and this sort of thing. They’ll be playing the game that minorities in the West play at the moment, because that’s all that’s left to them. You give them a slice of the ghetto, you predefine the culture (mass, middling, and elite), in the past but not into the future, elements of the culture which are too much reverent of your past don’t serve for the future and are therefore dammed off and not permitted. This is what, in a sense, White people face in America and elsewhere.

One of the great mysteries of the United States that has produced an enormous amount of this mass culture, some of which I have been at times rather glibly describing, is why has there never been a mass serious Right-wing movement of the real Right in the United States. The whole history of the 20th century and before would be different if that had occurred. Just think of it. Not some sort of trivial group, but a genuine group.

Don’t forget, the real position of the American ultras is isolationism. They don’t want to go out into the rest of the world and impose American neo-colonialism on everyone else. They’re the descendants of people who left the European dominion in order to create a new world. Hence, the paradox that the further Right you go in the United States, the more, not pacifist, but non-interventionist you become.

Before the Confederacy, there was a movement called the Know Nothings, and this is often why very Right-wing people in the United States are described as Know Nothings. Because when you’re asked about slavery, which of course is a very loaded and partial question, you said, “Well, I don’t know anything about it.” And that was a deliberate tactic to avoid being sucked in to an abolitionist agenda or a way of speaking that was biased in the political correctness of its own era.

But it is remarkable that although the Confederacy didn’t have the strength to win, if they had won the history of the whole world would be different. The 20th century would have never taken the course that it did.

One of the interesting things about the American psyche, of course, is that many unfortunate incidents, the war that we fought with the United States in 1812, for example, have been completely elided from history. It’s gone! It’s gone! We almost went to war with them in 1896 over Venezuela. That still has slightly interesting intonations even now a century or more on when Joseph Chamberlain was Colonial Secretary. This is again [elided] rather like the Suez incident 1956. There are certain incidents that are played up. And there are anniversaries that are every day on the television, and that you can’t escape from. But there are other anniversaries and other events which have been completely air-brushed from the spectrum and from the historical continuum as if they never occurred.

One episode is the extraordinarily bad treatment of prisoners of war by Americans going way, way back. The Confederates and the Unionists treated each other that way in the Civil War, but the Mexicans certainly got the boot in the 1840s as did the Spanish-Cubans at the turn of the 20th century. Americans beat up every German on principle, including members of Adenauer’s future cabinet when they occupied part of Germany. They just regard that as de rigeur. This frontier element that is there, crude and virile and ferocious, not always wrong, but ultimately fighting in ways which are not in the West’s interests, certainly for much of the 20th century, just gone, is part and parcel of the heroic American sense of themselves.

Where do all of these archetypes ultimately come from? That American popular culture which has gone universal because the deal is that what America thinks today, the world thinks tomorrow. When we allegedly ruled the world, or part of it, in the 19th century, Gladstone once stood in Manchester in the Free Trade Hall and said, “What Manchester thinks today, the world thinks tomorrow.” But now it’s what’s on MTV or CNN today, that the world would like to think is the ruling discourse of tomorrow.

American self-conceptuality is, to my mind, deeply, deeply Protestant in every sense. Even at the lowest level of their popular culture the idea of the heroic man, often a dissident police officer or a rancher or a hero of certain supernatural powers and so forth, but a man alone, a man outside the system, a man whose anti-Establishment, but he fights for order, a man who believes that everything’s settled with a weapon (which is why they always carry large numbers of weapons, these sort of survivalist type heroes). All of these heroes, the ones created by Robert E. Howard, the ones such as Doc Savage and Justice Inc., the Shadow, and all of the super-heroes like Batman.

Superman is interesting. Superman is Nietzschean ideas reduced to a thousand levels of sub-intellectuality, isn’t it? That’s what’s going on. He has a girlfriend who never ages called Lois Lane, who looks 22 now even though she’s about 88 in the trajectory of the script. There’s a villain who’s bald called Lex Luthor who’s always there, always the nemesis, always plotting. Luthor’s reinvented later in the strip as a politician who takes over the city. Superman’s clean and wholesome, you see, whereas the villain becomes a politician. You can see the sort of rhetoric.

Luthor and Superman in the stories are outsiders. They’re both extraterrestrials. Luthor, however, has anti-humanist values, which means he’s “evil,” whereas Superman, who’s partly human, has “humanist” values. Luthor comes up with amazing things, particularly in the 1930s comics, which are quite interesting, particularly given the ethnicity of the people who created Superman. Now, about half of American comics are very similar to the film industry, and a similar ethnicity is in the film industry as in the comics industry. Part of the notions of what is right and what is wrong, what is American and what is not, is defined by that particular grid.

Luthor and Superman in the stories are outsiders. They’re both extraterrestrials. Luthor, however, has anti-humanist values, which means he’s “evil,” whereas Superman, who’s partly human, has “humanist” values. Luthor comes up with amazing things, particularly in the 1930s comics, which are quite interesting, particularly given the ethnicity of the people who created Superman. Now, about half of American comics are very similar to the film industry, and a similar ethnicity is in the film industry as in the comics industry. Part of the notions of what is right and what is wrong, what is American and what is not, is defined by that particular grid.

Luthor’s an anti-humanite. Luthor always has these thuggish villains who have several teeth missing and are sort of Lombrosian, and they’re ugly, have broken noses and slanted hats. This is the 1930s. And Luthor says, “I’m sick of the human. We’ve got to transcend the human.” They don’t have words like “transcend” in comics. They say, “go beyond” or something, you know. “We’ve got to go beyond the human. Humans have got to go! I’ve got to replace them with a new species.” And one of his thugs will say, “Way to go, Luthor! This is what we want!” If you notice, you have a comic called Superman, but Superman has liberal values and fights for democracy and the American way, and Luthor, although no one ever says he’s “fascistic,” is harsh, is elitist, is inegalitarian.

You know that the villains have a tendency to punish their own men? You remember Blofeld in the Bond films? One of his own minions will fail him, and he’ll sit in a chair and you know what’s going to happen. A hand strokes the cat with the diamonds around its neck. The villain likes cats, and the cat’s eyes stare on. The finger quivers over the button. And Blofeld, or Luthor, or Dr. Doom, or the Red Skull, or the Joker, or whoever it is, because it’s the same force really, says, “You failed me. There is only one punishment in this organization . . .” Click! The button goes, and there’s an explosion, the bloke screams, goes down in the chair.

There’s a great scene in Thunderball at the beginning where the chair comes up again. It’s empty and steaming, and all the other cronies are readjusting their ties. Blofeld’s sat there, and the camera always pans to his hands, the hands of power. You know, the hands of death, the hands of Zeus, the hands of Henry VIII. The closet would meet, and they’d all be disarmed by guards, but he would have a double-headed axe down by the chair.

It’s said, by American propaganda, that Saddam Hussein once shot his Minister of Health during a revolutionary command council meeting, and the same script had to be continued in the meeting by the Deputy Minister of Health. Just think of how the Deputy Minister felt! Let’s hope he wasn’t wearing gray flannels, because they might have been brown by the end of the cabinet session.

This idea of dualism, moral dualism (ultimately a deeply Christian idea in many ways as well as a Zoroastrian idea) is cardinal for the morality of these comics and the popular films and TV serials and all the internet spin-offs and all of these computer games. Because even when the hero is a woman like Lara Croft and so on, it’s the same methodology coming round and round again. Because adolescent boys want to look at somebody who looks like Lara Croft as she runs around with guns in both hands with virtually nothing on. That’s the sort of dissident archetype in these American pulps going back a long way. It’s just the feminization of heroic masculinity actually, which is what these sort of Valkyries are in popular terms.

Now, the dualist idea is that there’s a force for evil and a force for good, and we know who they are (they are the ones out there!). In The Hulk, the Hulk is green because he’s been affected by gamma rays. The Hulk alternates with a brilliant scientist, but when he’s in his monstrous incarnation—because of course it’s a simplification of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in Robert Louis Stevenson’s myth—the Hulk, particularly early on in the comics, is incredibly stupid. If he saw this table in front of him he’d say, “Table. Don’t like table.” And he’d smash it, because Hulk smashes. That’s what he does! He smashes!

The villain in The Hulk is called the Leader. The Leader is the villain. The Leader is all brain. Indeed, the Leader has such a long head that he’s almost in danger of falling over because of the size of his brain. So, like children have to wear a steel brace on their teeth, the Leader wears a steel brace on his head because he’s “too bright.” So, the Leader—notice the Leader is a slightly proto-fascistic, Right-wing, elitist figure, isn’t he? The man who wants to dominate through his mind—is counter-posed by just brute force: the Hulk!

This idea that there’s a force for good and a force for evil and the one always supplants the other, but the one can never defeat the other, because the Leader in The Hulk, the Owl in Daredevil, the Joker in Batman, Dr. Doom in The Fantastic Four, Dr. Octopus and the Green Goblin (another green one) in Spiderman . . . They’re never destroyed. If one of them is destroyed, their son finds their mask in a trunk and puts it on and knows that he wants to dominate the world! And comes back again. They can never be destroyed because they’re archetypes.

The comics hint at a sort of pagan non-dualism partly because they insist upon this good and evil trajectory so much. That’s in some ways when they become quite morally complicated and quite dangerous.

In Greek tragedy, a moral system exists, and it’s preordained that you have a fate partly in your own hands even though it’s decided by the gods. In The Oresteia by Aeschylus, you have a tragedy in a family (cannibalism, destruction, self-devouring) which is revenged and passed through into future generations. So that the Greek fleet can get to Troy, a girl is sacrificed. Clytemnestra avenges herself as a Medusa, as a gorgon against her husband who has killed her own daughter. Then, of course, there’s a cycle of revenge and pity and the absence of pity when the son, Orestes, who identifies with the father, comes back.

In this type of culture, and obviously a much higher level conceptually, it’s noticeable that the good character and the evil character align, are differentiated, merging, replace one another, and separate over the three plays in that particular trilogy.

If you look at real life and you consider any conflict between men, Northern Ireland in the 1970s (we’re British here and many people here are British nationalists). But if you notice the IRA guerrilla/terrorist/paramilitary, the Loyalist guerilla/terrorist/paramilitary . . . One of my grandfathers was in the Ulster Volunteer Force at the beginning of the 20th century, but I went to a Catholic school.

Nietzsche has a concept called perspectivism whereby certain sides choose you in life, certain things are prior ordained. When the U.S. Marine fights the Islamist radical in Fallujah, the iconography of an American comic begins to collapse, because which is the good one and which is the evil one? The average Middle American as he sat reading Captain America zapping the channels thinks that the Marine is the good one, with a sort of 30-second attention span.

But at the same time, the Marine isn’t an incarnation of evil. He’s a man fighting for what he’s been told to fight for. He’s a warrior. There’re flies in his eyes. He’s covered in sweat. He’s gonna kill someone who opposes him. But the radical on the other side is the same, and he sees that he’s fighting for his people and the destiny of his faith. And when warriors fight each other, often there’s little hatred left afterwards, because it’s expended in the extraordinary ferocity of the moment.

This is when this type of mass culture, amusing and interesting and entertaining though it is, begins to fall away. Because whenever we’ve gone to war, and we’ve gone to war quite a lot over the last 10 to 12 years. Blair’s wars: Kosovo. There’s the bombing of the Serbs. Milošević is depicted as evil! Remember those slogans in the sun? Bomb Milošević’s bed! Bomb his bed! Bomb his house! And this sort of thing. Saddam! We’re gonna string him up! The man’s a war criminal! The fact he’d been a client to the West for years didn’t seem to come into it. Hanged. Showed extreme bravery in a way, even though if you weren’t a Sunni in Iraq, definitely, he wasn’t exactly your man.

There’s a degree to which the extraordinary demonization of the Other works. That’s why it’s used. The British National Party won two seats in that election but there was a campaign against it for 12 to 15 days before in almost every item of media irrespective of ideological profile saying, “Don’t vote for these people!” to get rid of the softer protest votes and you’re only left with the hard core. That’s why that type of ideology is used. Maybe humans are hardwired to see absolute malevolence as on the other side, when in actual fact it’s just a person who may or may not be fighting against them.

But what this type of mass or popular culture does is it retains the instinct of the heroic: to transcend, to fight, to struggle, to not know fear, to if one has fear to overcome it in the moment, to be part of the group but retain individual consciousness within it, to be male, to be biologically defined, to not be frightened of death, whatever religious or spiritual views and values that one incarnates in order to face that. These are, in a crude way, what these forms are suggesting. Morality is often instinctual, as is largely true with humans.

I knew somebody who fought in Korea. When they were captured, the Koreans debated amongst themselves whether they should kill all the prisoners. There were savage disputes between men. This always happens in war.

I remember, as I near the close of this speech, that one of Sir Oswald Mosley’s sons wrote a very interesting book both about his father and about his experiences in the Second World War. This is Nicholas Mosley, the novelist and biographer. He was in a parachute regiment, and there’s two stories that impinge upon the nature of the heroic that often appears in popular forms and which I’ll close with.

One is when he was with his other members. He was with his other parachutists, and they were in a room. There was The Daily Mirror, still going, the organ of Left-wing hate which is The Daily Mirror, and on the front it said, “Oswald Mosley: The Most Hated Man in Britain.” The most hated man in Britain. And a chap looked up from his desk and looked at Mosley who was leading a fighting brigade and said, “Mosley, you’re not related to this bastard, are you?” And he said, “I’m one of his sons.” And there was total silence in the room. Total silence in the room, and they stared each other out, and the bloke’s hands gripped The Mirror, and all the other paratroopers were looking at this incident. And after about four minutes it broke and the other one tore up The Mirror and put it in a bin at the back of the desk and said, “Sorry, mate. Didn’t mean anything. Really.” Mosley said, “Well, that’s alright then, old chap.” And left.

The other story is very, very interesting. This was they were advancing through France, and the Germans are falling back. And I believe I’ve told this story before at one of these meetings, but never waste a good story. A senior officer comes down the track and says, “Mosley! Mosley, you’re taking too many prisoners. You’re taking too many prisoners. It’s slowing the advance. Do you understand what I’m saying, Mosley?” And he said, “Sir, yes, I totally understand what you’re saying.” He says, “Do you really understand what I’m saying? You’re slowing the advance. Everyone’s noticing it. Do something about it. Do you understand?” “Sir!”

And he’s off, I guess to another spot of business further down. Mosley turns to his Welsh sergeant-major and says, “What do you think about that? We’re taking too many prisoners.” Because what the officer has told him in a very English and a very British way is to shoot German soldiers and to shoot German prisoners and to shoot them in ditches. What else does it mean? “You’re slowing the advance! You’re taking too many prisoners! You’re not soft on these people, are you, Mosley? Speed the advance of your column!” That’s what he’s saying, but it’s not written down. It’s not given as a formal and codified order. But everyone shoots prisoners in war! It’s a fact! When your friend’s had his head blown off next to you, you’d want revenge!

I know people who fought in the Falklands. And some of the Argentinian Special Forces and some of the conscripts together used dum-dum bullets. Hits a man, his spine explodes. So, when certain conscripts were found by British troops they finished them pretty quickly at Goose Green and elsewhere. This will occur! In all wars! Amongst all men! Of all races and of all kinds! Because it’s part of the fury that battle involves.

One of my views is that is that we can’t as a species, or even as groups, really face the fact that in situations of extremity this is what we’re like. And this is why, in some ways, we create for our entertainment these striated forms of heroic culture where there’s absolutely good and absolutely malevolent and the two never cross over. When the Joker is dragged off, justice is done and Inspector Gordon rings Batman up (because it is he) and says, “Well done! You’ve cleansed the city of a menace.” All of the villains go to an asylum called Arkham Asylum. They’re all taken to an asylum where they jibber insanely and wait for revenge against the nature of society.

I personally think that a great shadow has been cast for 60 years on people who want to manifest the most radical forms of political identity that relate to their own group, their own inheritance, their own nationality, their own civilizational construct in relation to that nationality, the spiritual systems from the past and in the present and into the future that are germane to them and not necessarily to the others, to their own racial and biological configuration. No other tendency of opinion is more demonized in the entire West. No other tendency of opinion is under pressure.

Two things can’t be integrated into the situationist spectacle based upon the right to shop. They’re religious fundamentalism and the radical Right, and they’re tied together in various ways. It’s why the two out-groups in Western society are radical Right-wing militants and Islamists. They’re the two groups that are Other, that are totally outside. The way in which they’re viewed by The Mirror and others is almost the level of a Marvel Comics villain.

I seem to remember a picture from the Sunday Telegraph years ago of our second speaker [David Irving], and I’m quite sure that it’d been re-tinted, at least this is my visual memory of it, to appear darker, to appear more sinister. I remember once GQ did a photo of me years ago when I was in a group called Revolutionary Conservative. That photo was taken in Parliament Square. You know, the square that has Churchill and Mandela in it, that square near our parliament, with Oliver Cromwell over there hiding, [unintelligible] over there hiding further on. That photo was taken at 12:30, and it was a brighter day than this. But in GQ magazine it was darkened to make it look as though it was shot at nine o’clock, and everything was dark, and because it involved so much re-tinting it slightly distorted and reconfigured everything. That’s because these people are dark, you see! They’re the force from outside! They’re that which shouldn’t be permitted!

Whereas I believe that the force which is for light and the force which is for darkness (because I’m a pagan) can come together and used creatively and based upon identity and can lead on to new vistas. But that’s a rather dangerous notion, and you won’t find it in The Fantastic Four when Reed Richards and Dr. Doom do battle, and you won’t find it in Spiderman when Peter Parker and Dr. Octopus (Dr. Otto Octavius) do battle with one another. You won’t see it when the Aryan Captain America is taking on his National Socialist nemesis, the Red Skull. You won’t see it with the Hulk taking on the Leader. You won’t see it in any of these forms. But these forms have a real use, and that is that they build courage.

Nietzsche says at the end of Zarathrustra that there are two things you need in this life. You need courage and knowledge. That’s why Zarathrustra has two friends. He has an eagle, which stands for courage, and he has a snake, which stands for knowledge. And if you can combine those things, and synthesize them, you have a new type of man and a new type of future. And Nietzsche chose the great Persian sage as the explicator of his particular truth, because in the past he represented extreme dualism, but in the future Nietzsche wished to portray that he brought those dualities together and combined them as one heroic force.

Thank you very much!

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/03/pulp-fascism/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/bowden.jpg

[2] here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dO0ak8G9KtE

00:05 Publié dans Bandes dessinées, Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : jonathan bowden, bandes dessinées, 9ème art, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite britannique, philosophie, littérature, lettres, graphic novels, angleterre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

La Tradition dans la pensée de Martin Heidegger et de Julius Evola

Le primordial et l’éternel :

La Tradition dans la pensée de Martin Heidegger et de Julius Evola

par Michael O'Meara

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

L’opposé de la tradition, dit l’historien Dominique Venner, n’est pas la modernité, une notion illusoire, mais le nihilisme [1]. D’après Nietzsche, qui développa le concept, le nihilisme vient avec la mort des dieux et « la répudiation radicale de [toute] valeur, sens et désirabilité » [2]. Un monde nihiliste – comme le nôtre, dans lequel les valeurs les plus élevées ont été dévaluées – est un monde incapable de canaliser les courants entropiques de la vie dans un flux sensé, et c’est pourquoi les traditionalistes associés à l’éternalisme guénonien, au traditionalisme radical, au néo-paganisme, au conservatisme révolutionnaire, à l’anti-modernisme et à l’ethno-nationalisme se rassemblent contre lui.

L’opposé de la tradition, dit l’historien Dominique Venner, n’est pas la modernité, une notion illusoire, mais le nihilisme [1]. D’après Nietzsche, qui développa le concept, le nihilisme vient avec la mort des dieux et « la répudiation radicale de [toute] valeur, sens et désirabilité » [2]. Un monde nihiliste – comme le nôtre, dans lequel les valeurs les plus élevées ont été dévaluées – est un monde incapable de canaliser les courants entropiques de la vie dans un flux sensé, et c’est pourquoi les traditionalistes associés à l’éternalisme guénonien, au traditionalisme radical, au néo-paganisme, au conservatisme révolutionnaire, à l’anti-modernisme et à l’ethno-nationalisme se rassemblent contre lui.

La tradition dont les vérités signifiantes et créatives sont affirmées par ces traditionalistes contre l’assaut nihiliste de la modernité n’est pas le concept anthropologique et sociologique dominant, défini comme « un ensemble de pratiques sociales inculquant certaines normes comportementales impliquant une continuité avec un passé réel ou imaginaire ». Ce n’est pas non plus la « démocratie des morts » de G. K. Chesterton, ni la « banque générale et le capital des nations et des âges » d’Edmund Burke. Pour eux la tradition n’avait pas grand-chose à voir avec le passé comme tel, des pratiques culturelles formalisées, ou même le traditionalisme. Venner, par exemple, la compare à un motif musical, un thème guidant, qui fournit une cohérence et une direction aux divers mouvements de la vie.

Si la plupart des traditionalistes s’accordent à voir la tradition comme orientant et transcendant à la fois l’existence collective d’un peuple, représentant quelque chose d’immuable qui renaît perpétuellement dans son expérience du temps, sur d’autres questions ils tendent à être en désaccord. Comme cas d’école, les traditionalistes radicaux associés à TYR s’opposent aux « principes abstraits mais absolus » que l’école guénonienne associe à la « Tradition » et préfèrent privilégier l’héritage européen [3]. Ici l’implication (en-dehors de ce qu’elle implique pour la biopolitique) est qu’il n’existe pas de Tradition Eternelle ou de Vérité Universelle, dont les vérités éternelles s’appliqueraient partout et à tous les peuples – seulement des traditions différentes, liées à des peuples différents dans des époques et des régions culturelles différentes. Les traditions spécifiques de ces histoires et cultures incarnent, comme telles, les significations collectives qui définissent, situent et orientent un peuple, lui permettant de triompher des défis incessant qui lui sont spécifiques. Comme l’écrit M. Raphael Johnson, la tradition est « quelque chose de similaire au concept d’ethnicité, c’est-à-dire un ensemble de normes et de significations tacites qui se sont développées à partir de la lutte pour la survie d’un peuple ». En-dehors du contexte spécifique de cette lutte, il n’y a pas de tradition [4].

Mais si puissante qu’elle soit, cette position « culturaliste » prive cependant les traditionalistes radicaux des élégants postulats philosophiques et principes monistes étayant l’école guénonienne. Non seulement leur projet de culture intégrale enracinée dans l’héritage européen perd ainsi la cohésion intellectuelle des guénoniens, mais il risque aussi de devenir un pot-pourri d’éléments disparates, manquant de ces « vues » philosophiques éclairées qui pourraient ordonner et éclairer la tradition dont ils se réclament. Cela ne veut pas dire que la révolte de la tradition contre le monde moderne doive être menée d’une manière philosophique, ou que la renaissance de la tradition dépende d’une formulation philosophique spécifique. Rien d’aussi utilitaire ou utopique n’est impliqué, car la philosophie ne crée jamais – du moins jamais directement – « les mécanismes et les opportunités qui amènent un état de choses historique » [5]. De telles « vues » fournissent plutôt une ouverture au monde – dans ce cas, le monde perdu de la tradition – montrant la voie vers ces perspectives que les traditionalistes radicaux espèrent retrouver.

Je crois que la pensée de Martin Heidegger offre une telle vision. Dans les pages qui suivent, nous défendrons une appropriation traditionaliste de la pensée heideggérienne. Les guénoniens sont ici pris comme un repoussoir vis-à-vis de Heidegger non seulement parce que leur approche métaphysique s’oppose à l’approche historique européenne associée à TYR, mais aussi parce que leur discours possède en partie la rigueur et la profondeur de Heidegger. René Guénon représente cependant un problème, car il fut un apostat musulman de la tradition européenne, désirant « orientaliser » l’Occident. Cela fait de lui un interlocuteur inapproprié pour les traditionalistes radicaux, particulièrement en comparaison avec son compagnon traditionaliste Julius Evola, qui fut l’un des grands champions contemporains de l’héritage « aryen ». Parmi les éternalistes, c’est alors Evola plutôt que Guénon qui offre le repoussoir le plus approprié à Heidegger [6].

Le Naturel et le Surnaturel

Etant donné les fondations métaphysiques des guénoniens, le Traditionalisme d’Evola se concentrait non sur « l’alternance éphémère des choses données aux sens », mais sur « l’ordre éternel des choses » situé « au-dessus » d’elles. Pour lui Tradition signifie la « sagesse éternelle, la philosophia perennis, la Vérité Primordiale » inscrite dans ce domaine supra-humain, dont les principes éternels, immuables et universels étaient connus, dit-on, des premiers hommes et dont le patrimoine (bien que négligé) est aujourd’hui celui de toute l’humanité [7].

La « méthode traditionaliste » d’Evola vise ainsi à recouvrer l’unité perdue dans la multiplicité des choses du monde. De ce fait il se préoccupe moins de la réalité empirique, historique ou existentielle (comprise comme un reflet déformé de quelque chose de supérieur) que de l’esprit – tel qu’on le trouve, par exemple, dans le symbole, le mythe et le rituel. Le monde humain, par contre, ne possède qu’un ordre d’importance secondaire pour lui. Comme Platon, il voit son domaine visible comme un reflet imparfait d’un domaine invisible supérieur. « Rien n’existe ici-bas », écrit-il, « …qui ne s’enracine pas dans une réalité plus profonde, numineuse. Toute cause visible n’est qu’apparente » [8]. Il refuse ainsi toutes les explications historiques ou naturalistes concernant le monde contingent de l’homme.

Voyant la Tradition comme une « présence » transmettant les vérités transcendantes obscurcies par le tourbillon éphémère des apparences terrestres, Evola identifie l’Etre à ses vérités immuables. Dans cette conception, l’Etre est à la fois en-dehors et au-delà du cours de l’histoire (c’est-à-dire qu’il est supra-historique), alors que le monde humain du Devenir est associé à un flux toujours changeant et finalement insensé de vie terrestre de sensations. La « valeur suprême et les principes fondateurs de toute institution saine et normale sont par conséquent invariables, étant basés sur l’Etre » [9]. C’est de ce principe que vient la doctrine évolienne des « deux natures » (la naturelle et la surnaturelle), qui désigne un ordre physique associé au monde du Devenir connu de l’homme et un autre ordre qui décrit le royaume métaphysique inconditionné de l’Etre connu des dieux.

Les civilisations traditionnelles, affirme Evola, reflétaient les principes transcendants transmis dans la Tradition, alors que le royaume « anormal et régressif » de l’homme moderne n’est qu’un vestige décadent de son ordre céleste. Le monde temporel et historique du Devenir, pour cette raison, est relégué à un ordre d’importance inférieur, alors que l’unité éternelle de l’Etre est privilégiée. Comme son « autre maître » Joseph de Maistre, Evola voit la Tradition comme antérieure à l’histoire, non conditionnée par le temps ou les circonstances, et donc sans lien avec les origines humaines » [10]. La primauté qu’il attribue au domaine métaphysique est en effet ce qui le conduit à affirmer que sans la loi éternelle de l’Etre transmise dans la Tradition, « toute autorité est frauduleuse, toute loi est injuste et barbare, toute institution est vaine et éphémère » [11].

La Tradition comme Überlieferung

Heidegger suit la voie opposée. Eduqué pour une vocation dans l’Eglise catholique et fidèle aux coutumes enracinées et provinciales de sa Souabe natale, lui aussi s’orienta vers « l’ancienne transcendance et non la mondanité moderne ». Mais son anti-modernisme s’opposait à la tradition de la pensée métaphysique occidentale et, par implication, à la philosophie guénonienne de la Tradition (qu’il ne connaissait apparemment pas).

La métaphysique est cette branche de la philosophie qui traite des questions ontologiques majeures, la plus fondamentale étant la question : Qu’est-ce que l’Etre ? Commençant avec Aristote, la métaphysique tendit néanmoins à s’orienter vers la facette non-physique et non-terrestre de l’Etre, tentant de saisir la transcendance de différents êtres comme l’esprit, la force, ou l’essence [12]. En recourant à des catégories aussi généralisées, cette tendance postule un royaume transcendant de formes permanentes et de vérités inconditionnées qui comprennent l’Etre d’une manière qui, d’après Heidegger, limite la compréhension humaine de sa vérité, empêchant la manifestation d’une présence à la fois cachée, ouverte et fuyante. Dans une formulation opaque mais cependant révélatrice, Heidegger écrit : « Quand la vérité [devient une incontestable] certitude, alors tout ce qui est vraiment réel doit se présenter comme réel pour l’être réel qu’il est [supposément] » – c’est-à-dire que quand la métaphysique postule ses vérités, pour elle la vérité doit se présenter non seulement d’une manière autoréférentielle, mais aussi d’une manière qui se conforme à une idée préconçue d’elle-même » [13]. Ici la différence entre la vérité métaphysique, comme proposition, et l’idée heideggérienne d’une manifestation en cours est quelque peu analogue à celle différenciant les prétentions de vérité du Dieu chrétien de celles des dieux grecs, les premières présupposant l’objectivité totale d’une vérité universelle éternelle et inconditionnée préconçue dans l’esprit de Dieu, et les secondes acceptant que la « dissimulation » est aussi inhérente à la nature polymorphe de la vérité que l’est la manifestation [14].

Etant donné son affirmation a-historique de vérités immuables installées dans la raison pure, Heidegger affirme que l’élan préfigurant et décontextualisant de la métaphysique aliène les êtres de l’Etre, les figeant dans leurs représentations momentanées et les empêchant donc de se déployer en accord avec les possibilités offertes par leur monde spécifique. L’oubli de l’être culmine dans la civilisation technologique moderne, où l’être est défini simplement comme une chose disponible pour l’investigation scientifique, la manipulation technologique et la consommation humaine. La tradition métaphysique a obscurci l’Etre en le définissant en termes essentiellement anthropocentriques et même subjectivistes.

Mais en plus de rejeter les postulats inconditionnés de la métaphysique [15], Heidegger associe le mot « tradition » – ou du moins sa forme latinisée (die Tradition) – à l’héritage philosophique occidental et son oubli croissant de l’être. De même, il utilise l’adjectif « traditionell » péjorativement, l’associant à l’élan généralisant de la métaphysique et aux conventions quotidiennes insouciantes contribuant à l’oubli de l’Etre.

Mais après avoir noté cette particularité sémantique et son intention antimétaphysique, nous devons souligner que Heidegger n’était pas un ennemi de la tradition, car sa philosophie privilégie ces « manifestations de l’être » originelles dans lesquelles naissent les grandes vérités traditionnelles. Comme telle, la tradition pour lui n’est pas un ensemble de postulats désincarnés, pas quelque chose d’hérité passivement, mais une facette de l’Etre qui ouvre l’homme à un futur lui appartenant en propre. Dans cet esprit, il associe l’Überlieferung (signifiant aussi tradition) à la transmission de ces principes transcendants inspirant tout « grand commencement ».

La Tradition dans ce sens primordial permet à l’homme, pense-t-il, « de revenir à lui-même », de découvrir ses possibilités historiquement situées et uniques, et de se réaliser dans la plénitude de son essence et de sa vérité. En tant qu’héritage de destination, l’Überlieferung de Heidegger est le contraire de l’idéal décontextualisé des Traditionalistes. Dans Etre et Temps, il dit que die Tradition « prend ce qui est descendu vers nous et en fait une évidence en soi ; elle bloque notre accès à ces ‘sources’ primordiales dont les catégories et les concepts transmis à nous ont été en partie authentiquement tirés. En fait, elle nous fait oublier qu’elles ont eu une telle origine, et nous fait supposer que la nécessité de revenir à ces sources est quelque chose que nous n’avons même pas besoin de comprendre » [17]. Dans ce sens, Die Tradition oublie les possibilités formatives léguées par son origine de destination, alors que l’Überlieferung, en tant que transmission, les revendique. La pensée de Heidegger se préoccupe de retrouver l’héritage de ces sources anciennes.

Sa critique de la modernité (et, contrairement à ce qu’écrit Evola, il est l’un de ses grands critiques) repose sur l’idée que la perte ou la corruption de la tradition de l’Europe explique « la fuite des dieux, la destruction de la terre, la réduction des êtres humains à une masse, la prépondérance du médiocre » [18]. A présent vidé de ses vérités primordiales, le cadre de vie européen, dit-il, risque de mourir : c’est seulement en « saisissant ses traditions d’une manière créative », et en se réappropriant leur élan originel, que l’Occident évitera le « chemin de l’annihilation » que la civilisation rationaliste, bourgeoise et nihiliste de la modernité semble avoir pris » [19].

La tradition (Überlieferung) que défend l’antimétaphysique Heidegger n’est alors pas le royaume universel et supra-sensuel auquel se réfèrent les guénoniens lorsqu’ils parlent de la Tradition. Il s’agit plutôt de ces vérités primordiales que l’Etre rend présentes « au commencement » –, des vérités dont les sources historiques profondes et les certitudes constantes tendent à être oubliées dans les soucis quotidiens ou dénigrées dans le discours moderniste, mais dont les possibilités restent néanmoins les seules à nous être vraiment accessibles. Contre ces métaphysiciens, Heidegger affirme qu’aucune prima philosophia n’existe pour fournir un fondement à la vie ou à l’Etre, seulement des vérités enracinées dans des origines historiques spécifiques et dans les conventions herméneutiques situant un peuple dans ses grands récits.

Il refuse ainsi de réduire la tradition à une analyse réfléchie indépendante du temps et du lieu. Son approche phénoménologique du monde humain la voit plutôt comme venant d’un passé où l’Etre et la vérité se reflètent l’un l’autre et, bien qu’imparfaitement, affectent le présent et la manière dont le futur est approché. En tant que tels, Etre, vérité et tradition ne peuvent pas être saisis en-dehors de la temporalité (c’est-à-dire la manière dont les humains connaissent le temps). Cela donne à l’Etre, à la vérité et à la tradition une nature avant tout historique (bien que pas dans le sens progressiste, évolutionnaire et développemental favorisé par les modernistes). C’est seulement en posant la question de l’Etre, la Seinsfrage, que l’Etre de l’humain s’ouvre à « la condition de la possibilité de [sa] vérité ».

C’est alors à travers la temporalité que l’homme découvre la présence durable qui est l’Etre [20]. En effet, si l’Etre de l’homme n’était pas situé temporellement, sa transcendance, la préoccupation principale de la métaphysique guénonienne, serait inconcevable. De même, il n’y a pas de vérité (sur le monde ou les cieux au-dessus de lui) qui ne soit pas ancrée dans notre Etre-dans-le-monde – pas de vérité absolue ou de Tradition Universelle, seulement des vérités et des traditions nées de ce que nous avons été… et pouvons encore être. Cela ne veut pas dire que l’Etre de l’humain manque de transcendance, seulement que sa possibilité vient de son immanence – que l’Etre et les êtres, le monde et ses objets, sont un phénomène unitaire et ne peuvent pas être saisis l’un sans l’autre.

Parce que la conception heideggérienne de la tradition est liée à la question de l’Etre et parce que l’Etre est inséparable du Devenir, l’Etre et la tradition fidèle à sa vérité ne peuvent être dissociés de leur émergence et de leur réalisation dans le temps. Sein und Zeit, Etre immuable et changement historique, sont inséparables dans sa pensée. L’Etre, écrit-il, « est Devenir et le Devenir est Etre » [21]. C’est seulement par le processus du devenir dans le temps, dit-il, que les êtres peuvent se déployer dans l’essence de leur Etre. La présence constante que la métaphysique prend comme l’essence de l’Etre est elle-même un aspect du temps et ne peut être saisie que dans le temps – car le temps et l’Etre partagent une coappartenance primordiale.