Giorgio Locchi et le mythe surhumaniste

par Edouard Rix

«Es klang so alt, und war doch so neu »

(Cela sonnait si ancien, et était pourtant si nouveau)

Richard Wagner, Les Maîtres-chanteurs de Nuremberg

« J’ai deux inspirateurs principaux : Nietzsche et Giorgio Locchi » confesse Guillaume Faye, pour qui « sans Giorgio Locchi et son oeuvre, qui se mesure à son intensité et non point à sa quantité, et qui reposa aussi sur un patient travail de formation orale, la véritable chaîne de défense de l’identité européenne serait probablement rompue »(1). De même, si dans ses mémoires Alain de Benoist n’accorde qu’une ligne à l’apport de Guillaume Faye et de Robert Steuckers à la Nouvelle droite(2), il admet toutefois : « C’est en grande partie sous l’influence de Locchi que la ND des années 70 a désigné l’égalitarisme comme ennemi principal. La dizaine d’articles de lui que j’ai publiés dans Nouvelle Ecole comptent certainement parmi les meilleurs jamais parus dans cette revue »(3).

C’est au milieu des années 60 que de Benoist rencontre Giorgio Locchi, journaliste italien installé à Paris où il est le correspondant du quotidien romain Il Tempo. Ce docteur en droit de 43 ans impressionne le jeune homme, qui l’invite à écrire dans les Cahiers universitaires. Fin 1966, il publie dans le numéro 29 un article dans lequel il s’interroge sur le possibilité d’une « science historique » à la lumière des récents enseignements de la microphysique. Persuadé que le devenir historique exige une rupture pour réaffirmer « la soumission des masses aux élites, la nécessité d’une société pyramidale », Locchi précise qu’« il n’y aura d’histoire que par la volonté de faire l’histoire »(4).

Parallèlement, sous le pseudonyme de Hans-Jürgen Nigra, il collaborera irrégulièrement à Défense de l’Occident. Les spécialistes autoproclamés de l’extrême-droite Jean-Yves Camus et René Monzat l’identifieront (sic) comme l’un des militants « allemands » qui s’expriment dans la revue de Maurice Bardèche - ce qui aurait fait sourire ce germaniste accompli -.

Il était une fois le GRECE

Entré au comité de rédaction de Nouvelle Ecole en 1969, Giorgio Locchi sera l’un des principaux initiateurs du GRECE. Ce n’est pas un hasard si le numéro 6 de la revue, daté de l’hiver 1968-1969, reproduit l’intégralité de la communication qu’il a envoyée au 1er colloque de l’Institut d’études occidentales. Avec ce texte, d’imprégnation nietzschéenne, qui s’inspire des critiques généalogiques de l’égalitarisme et de l’universalisme - renvoyés à leurs origines judéo-chrétiennes - présentes dans Par delà le bien et le mal et le Crépuscule des idoles, Locchi fournit le cadre philosophico-historique dans lequel s’inscrira le GRECE des années 70. « Le marxisme, écrit-il, a bel et bien poussé jusque dans ses extrêmes conséquences une idée qui, depuis deux mille ans dominait la réflexion européenne (...). Cette idée est l’idée égalitaire, introduite dans le monde romain grâce au christianisme ». Il poursuit : « Ce sera le fait de la Révolution française que de vouloir appliquer le concept égalitaire à un des aspects de la réalité humaine, c’est-à-dire dans la loi ».

Dans une conférence prononcée lors du 5ème séminaire régional du GRECE, qui se tient à Paris le 16 avril 1972 sur le thème « Nietzsche et notre temps », il définit ainsi le projet politique nietzschéen - que l’on peut lui attribuer en propre - : « Combattre l’égalitarisme : tel est le but essentiel que s’est fixé Nietzsche (...) Nietzsche appelle une aristocratie qui puisse tirer son droit de diriger la masse de ses qualités naturelles, de sa valeur. Une aristocratie qui représente un type d’homme supérieur »(5). Fin connaisseur de la Nouvelle droite, Pierre-André Taguieff souligne que Locchi a permis à Alain de Benoist « de lire Nietzsche dans la double perspective d’une généalogie de l’égalitarisme moderne et de la définition d’une “grande politique“ centrée sur l’idée européenne »(6). L’une des premières brochures doctrinales publiées par le GRECE(7) doit d’ailleurs beaucoup au penseur italien...

Taguieff en dresse le portrait suivant : « Doté d’une grande culture germanique (il s’intéressait notamment à Nietzsche, Wagner, aux penseurs de la “révolution conservatrice“ allemande, en particulier à Spengler, et au national-socialisme)», il « ne publie guère, dans Nouvelle Ecole, que des études d’aspect “théorique“ où la dimension historique n’est jamais séparée du souci doctrinal »(8). Chacun de ses articles se révèle être un véritable petit essai : « Linguistique et sciences humaines », « “Le vocabulaire des institutions européennes“ d’Emile Benvéniste », « “L’homme et la technique“ d’Oswald Spengler », « Histoire et sociétés : critique de Lévi-Strauss », « Nietzsche et ses “récupérateurs“ », « Le mythe cosmogonique indo-européen : reconstruction et réalité », « Le règne, l’empire, l’imperium », « Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918-1932, essai d’Armin Mohler », « Il était une fois l’Amérique », « L’histoire », « Richard Wagner et la régénération de l’histoire » « Ethologie et sciences humaines ». C’est à lui que l’on doit l’épais dossier polémique - auquel Alain de Benoist a apporté des notes complémentaires » que le numéro 27-28 de Nouvelle Ecole a consacré aux Etats-Unis. Rompant radicalement avec l’occidentalisme et l’atlantisme viscéral de l’extrême-droite française, les auteurs affirment que « si l’idéologie américaine est l’un des déchets de la civilisation occidentale, l’Amérique est elle-même le déchet matériel de l’Europe »(9). L’article se termine par une conclusion cinglante : « La menace qui, par le fait des Etats-Unis, pèse sur le monde est celle d’une forme particulièrement pernicieuse d’universalisme et d’égalitarisme »(10). Il sera traduit et publié en Italie(11) et en Allemagne(12).

Le fascisme a un cœur nouveau

L’un des rares textes que Giorgio Locchi a écrit directement en italien est consacré au fascisme. Une première version abrégée est d’abord paru dans Elementi, revue de la Nuova destra italienne, sous le titre « Le fascisme a un cœur antique ». « Voilà qui prouve qu’ils n’ont rien compris à ce que soutient mon texte, qui dit exactement le contraire, à savoir que le fascisme a un cœur nouveau » raillera l’auteur. Effectivement, il insiste, dans ce court essai, sur ce qu’il appelle le « repli-sur-les-origines-projet-d’avenir » du fascisme : « Pour le “fasciste“, la “nation“ finit par être retrouvée, plus que dans le présent, dans un lointain passé “mythique“ et poursuivie ensuite dans l’avenir, terre des enfants, Land der Kinder (Nietzsche) plus que terre des pères ». Une seconde version sera publiée en 1981(13).

Pour Locchi, le fascisme est la première manifestation politique d’un vaste phénomène spirituel et culturel, qu’il nomme le « Surhumanisme », dont l’origine remonte à la deuxième moitié du XIXe siècle, et qui « se configure comme une sorte de champ magnétique en expansion dont les pôles sont Richard Wagner (rarement reconnu) et Friedrich Nietzsche ». Entre Surhumanisme et fascisme, le rapport génétique spirituel est évident. Ce « principe surhumaniste se caractérise par le rejet absolu d’un “principe égalitaire“ opposé qui conforme le monde qui l’entoure ». Or, « si les mouvements fascistes situèrent l’ennemi - spirituel avant même que politique - dans les idéologies démocratiques - libéralisme, parlementarisme, socialisme, communisme, anarcho-communisme - c’est justement parce que dans la perspective historique instituée par le principe surhumaniste, ces idéologies se présentent comme autant de manifestations, apparues successivement dans l’histoire, mais toutes encore présentes, du principe égalitaire opposé, comme tendant toutes en définitive, avec un divers degré de conscience, vers un même but, et comme étant toutes ensemble la cause de la décadence spirituelle et matérielle de l’Europe, de l’“avilissement progressif“ de l’homme européen, de la décadence des sociétés occidentales ».

A l’instar d’Armin Mohler, il estime que « l’image la plus adaptée » pour représenter le temps de l’histoire de la vision surhumaniste est « celle de la Sphère », déjà présente dans Ainsi parlait Zarathoustra de Nietzsche. Il précise que « si dans le temps linéaire, le “moment“ présent et ponctuel en divisant ainsi la ligne du devenir en passé et futur, et si, d’autre part, l’on ne vit donc que dans le présent ponctiforme, dans le temps sphérique de la vision surhumaniste, le présent est tout autre chose : il est la sphère dont les dimensions sont passé, actualité, futur - et l’homme est l’homme, et non pas animal, justement parce que, au moyen de sa conscience, il vit dans ce présent tridimensionnel et qui est passé-actualité-futur-en-même-temps, et qui donc ainsi est aussi toujours fatalité du devenir historique ».

A l’instar d’Armin Mohler, il estime que « l’image la plus adaptée » pour représenter le temps de l’histoire de la vision surhumaniste est « celle de la Sphère », déjà présente dans Ainsi parlait Zarathoustra de Nietzsche. Il précise que « si dans le temps linéaire, le “moment“ présent et ponctuel en divisant ainsi la ligne du devenir en passé et futur, et si, d’autre part, l’on ne vit donc que dans le présent ponctiforme, dans le temps sphérique de la vision surhumaniste, le présent est tout autre chose : il est la sphère dont les dimensions sont passé, actualité, futur - et l’homme est l’homme, et non pas animal, justement parce que, au moyen de sa conscience, il vit dans ce présent tridimensionnel et qui est passé-actualité-futur-en-même-temps, et qui donc ainsi est aussi toujours fatalité du devenir historique ».

L’on retrouve cette conception surhumaniste dans le fascisme, et c’est pourquoi « les “projets historiques“ des mouvements fascistes se configurent toujours comme un rappel - et un “repli“ - sur une “origine“ et sur un “passé“ plus ou moins éloigné, qui toute fois sont projetés en même temps dans l’avenir comme but à atteindre » : romanité dans le fascisme italien, germanité préchrétienne dans le national-socialisme. Or, « le “passé“ duquel on se réclame et qui peut être vanté dans un but démagogique de propagande comme toujours vivant et actuel (dans le “peuple“ et dans la “race“, entendus presque comme résiduelle), est en réalité considéré de façon pessimiste comme un bien perdu, “sorti de l’histoire“, donc comme devant être ré-inventé et créé ex-novo ».

Dans Wagner, Nietzsche e il Mito Sovrumanista(14), - ouvrage dont trois des six chapitres sont une remise en forme de ses articles wagnériens parus dans les numéros 30 et 31-32 de Nouvelle Ecole -, il insistera encore sur ce qui caractérise en propre la vision du monde surhumaniste formulée par Wagner, Nietzsche et Heidegger, à savoir la substitution au temps linéaire judéo-chrétien de la tridimensionnalité du devenir historique, symbolisé par l’image de la sphère. « Il est difficile, remarque Taguieff de ne pas percevoir un écho de ces conceptions dans la philosophie “nominaliste“ de l’histoire exposée systématiquement par Alain de Benoist dans le numéro 33 de Nouvelle Ecole, daté de juin 1979, “Fondements nominalistes d’une attitude devant la vie“ (p. 22-30), où, en référence à Nietzsche, il est proposé de substituer à la conception cyclique de l’histoire “une conception résolument sphérique“ (p. 24). N’y aurait-il pas dans cette reprise mimétique la véritable raison - ou le facteur décisif - de la rupture entre Giorgio Locchi et Alain de Benoist ? »(15). A ce facteur personnel, il faut ajouter le refus de Locchi de voir le GRECE quitter la métapolitique pour la politique(16).

Comme le disait maître Eckhart, la parole surhumaniste de Giorgio Locchi « n’est destinée à personne qui ne la fasse déjà sienne comme principe de sa propre vie ou ne la possède au moins comme un désir de son cœur ».

Edouard Rix, Réfléchir & Agir, été 2013, n°44, pp. 45-47.

Notes

(1) G. Faye, postface à la deuxième édition de L’essenza del fascismo.

(2) A. de Benoist, Mémoire vive. Entretiens avec François Bousquet, éditions de Fallois, Paris, 2012, p. 142.

(3) Ibid, p.160.

(4) G. Locchi, « Profil de l’histoire », Cahiers universitaires, novembre-décembre 1966, n°29, p. 52.

(5) G. Locchi, « Nietzsche et le mythe européen », Engadine, automne 1972, n°13, p. 2.

(6) P.-A. Taguieff, Sur la Nouvelle droite, Descartes et cie, Paris, 1994, p. 152.

(7) A. de Benoist, Nietzsche : morale et “grande politique“, GRECE, Paris, 1974, 44 p.

(8) P.-A. Taguieff, op. cit., p. 153.

(9) R. de Herte et H.-J. Nigra, « Il était une fois l’Amérique », Nouvelle Ecole, automne-hiver 1975, n°27-28, p. 10.

(10) Ibid, p. 95.

(11) G. Locchi et A. de Benoist, Il male americano, LEDE, Rome, 1978, 190 p.

(12) R. de Herte et H.-J. Nigra, Die USA,Europas missratenes Kind, Herbig, coll. « Herbig Aktuell », München-Berlin, 1979, 197 p.

(13) G. Locchi,L'essenza del fascismo, Edizioni del Tridente, Castelnuovo Magra, 1981.

(14) G. Locchi, Wagner, Nietzsche e il Mito Sovrumanista, Akropolis, Naples,1982.

(15) P.-A. Taguieff, op. cit., p. 156.

(16) Entretien avec Pierluigi Locchi, 18 mars 2012.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

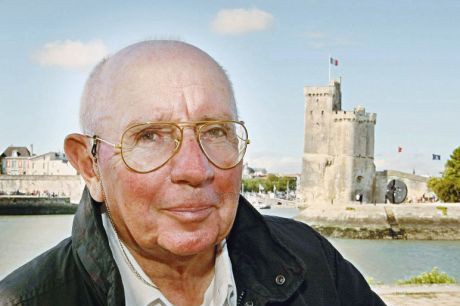

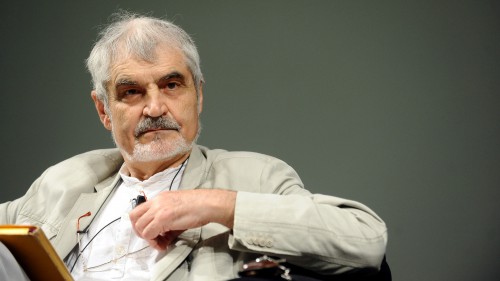

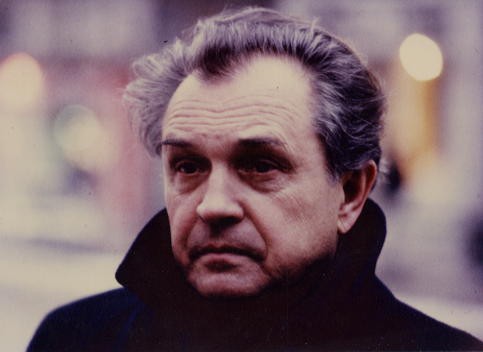

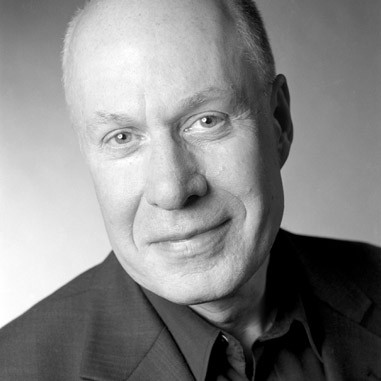

Jean-François Mattéi, c'était d'abord un Grec. Homme d'une immense culture, profondément engagé dans la défense des plus hautes valeurs de l'humanisme européen, il s'inquiétait du déclin de l’Europe. Il laisse une œuvre de première importance consacrée autant aux philosophes grecs, dont il était un éminent spécialiste, qu’à Heidegger, Nietzsche, ou Camus.

Jean-François Mattéi, c'était d'abord un Grec. Homme d'une immense culture, profondément engagé dans la défense des plus hautes valeurs de l'humanisme européen, il s'inquiétait du déclin de l’Europe. Il laisse une œuvre de première importance consacrée autant aux philosophes grecs, dont il était un éminent spécialiste, qu’à Heidegger, Nietzsche, ou Camus.

Jean-François Mattei, le pied-noir d’Oran qui a quitté son pays en 1962 défendait, au nom de la fidélité à ses origines, la colonisation. Pour lui, « loin d'être l'abomination que l'on dénonce aujourd'hui, et en dépit de ses abus et de ses violences, la colonisation a été le processus historique de développement de l'humanité dans sa recherche de principes et de savoirs universels. »

Jean-François Mattei, le pied-noir d’Oran qui a quitté son pays en 1962 défendait, au nom de la fidélité à ses origines, la colonisation. Pour lui, « loin d'être l'abomination que l'on dénonce aujourd'hui, et en dépit de ses abus et de ses violences, la colonisation a été le processus historique de développement de l'humanité dans sa recherche de principes et de savoirs universels. »

Attention, géographe non conforme.

Attention, géographe non conforme. Pour cette géographie mythique, il emprunte beaucoup à Mircéa Eliade et notamment son ouvrage Traité d’histoire des religions. Concrètement, donc, la terre, la mer, l’air, le feu, pour reprendre des thèmes chers à Gaston Bachelard, sont au cœur du processus d’échange et de coexistence entre la terre en sens large et les hommes. D’ailleurs notons que les « hommes » pris en exemple sont souvent des peuplades aux rapports très privilégiés avec leur environnement, qui est souvent peu maniable (nordicité, aridité, forêt sempervirente).

Pour cette géographie mythique, il emprunte beaucoup à Mircéa Eliade et notamment son ouvrage Traité d’histoire des religions. Concrètement, donc, la terre, la mer, l’air, le feu, pour reprendre des thèmes chers à Gaston Bachelard, sont au cœur du processus d’échange et de coexistence entre la terre en sens large et les hommes. D’ailleurs notons que les « hommes » pris en exemple sont souvent des peuplades aux rapports très privilégiés avec leur environnement, qui est souvent peu maniable (nordicité, aridité, forêt sempervirente).

[1]Rezension aus Sezession 58 / Februar 2014

[1]Rezension aus Sezession 58 / Februar 2014