Robert Steuckers:

De la “novlangue” aujourd’hui

Conférence prononcée au “Club de la Grammaire”, Genève, 9 avril 2014

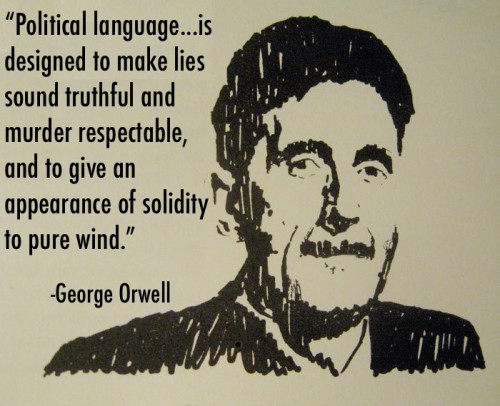

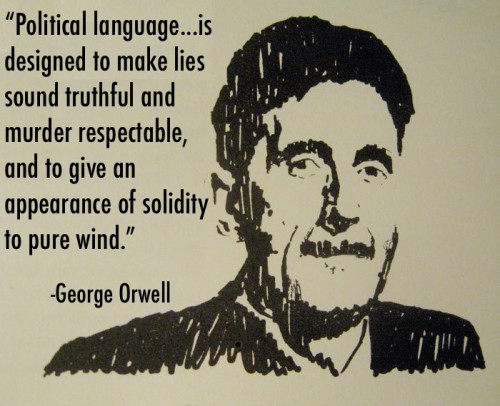

C’est à la demande de Maître Pascal Junod, Président du “Club de la Grammaire”, que j’ai composé tout récemment cette conférence sur la novlangue, suite à l’allocution que j’avais déjà prononcée, à cette même tribune en avril 2010, sur la biographie d’Orwell, sur les étapes successives de sa pensée. Cette conférence s’inscrivait dans le cadre d’un cycle consacré aux “romans politiques” (les political novels), où j’ai abordé aussi Soljénitsyne (en 2009) et Koestler (en 2011). A l’évidence, la notion orwellienne et romanesque de “novlangue” correspond aux pesanteurs actuelles de la “political correctness” ou “rectitude politique”, comme on le dit plus justement au Québec. Aborder ce thème de la manipulation systématique du langage, perpétrée dans le but de freiner toute effervescence ou innovation politiques, est, on en conviendra, un vaste sujet, vu le nombre d’auteurs qui se sont penchés sur ce phénomène inquiétant depuis la mort d’Orwell.

Le point de départ de cette conférence —car il faut bien en trouver un— reste le fonds orwellien, abordé en avril 2010. L’approche biographique et narrative que nous avions choisie, il y a quatre ans, permettait de pister littéralement les étapes de l’éveil orwellien, toutes étapes importantes pour comprendre la genèse de sa théorie du langage, laquelle est sans cesse réétudiée, remise sur le métier, notamment en France par un Jean-Claude Michéa, professeur de philosophie à Montpellier. Orwell, au cours de son existence d’aventurier et d’écrivain, est sorti progressivement de sa condition humaine, trop humaine, de ses angoisses d’adolescent, d’adulte issu d’une classe privilégiée un peu en marge du monde réel, en marge du monde de ceux qui peinent et qui souffrent, pour devenir, grâce à Animal Farm et à 1984, un classique de la littérature et, partant, de la philosophie, tant son incomparable fiction contre-utopique a été prémonitoire, a signalé des glissements de terrain en direction d’un monde totalement aseptisé et contrôlé.

Le fonds orwellien

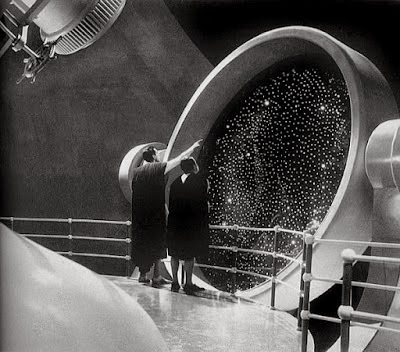

Le fonds orwellien est donc incontournable, est un classique du 20ème siècle auquel on ne peut échapper si l’on veut s’armer pour faire face à un monde de plus en plus déraciné, de plus en plus contrôlé par des agences médiatiques et étatiques qui oblitèrent la luxuriance du réel, veulent empêcher les hommes de voir et d’aimer cette luxuriance et d’y puiser des recettes pour changer ou faire bouger les choses selon les rythmes d’une harmonie toute naturelle. Certes, le contexte, notamment le contexte technologique, mis en place dans l’oeuvre romanesque d’Orwell n’est plus le même. Les périodes du début du 20ème siècle, marquées par le militantisme virulent et les totalitarismes utopiques et messianiques, ne sont plus reproduisibles telles quelles. Néanmoins, la genèse de la situation actuelle, où tout est contrôlé via la NSA, les satellites et l’internet, Orwell l’a bien perçue, l’a anticipée conceptuellement. Notre réalité, plus surveillée que jamais, est un avatar mutatis mutandis d’une volonté politique de contrôle total, déjà mise en place au temps d’Orwell.

Quel est-il, ce contexte, où émerge l’oeuvre orwellienne? Il est celui 1) du totalitarisme ambiant et 2) de la volonté d’aseptiser la langue pour contrôler les esprits.

◊ 1. Le totalitarisme ambiant.

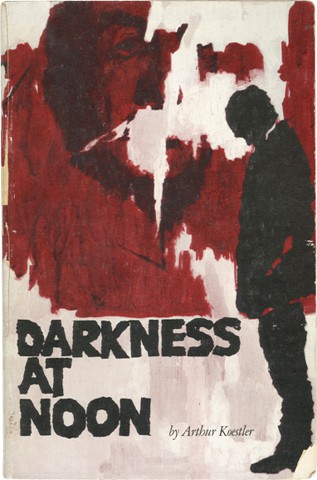

L’époque d’Orwell est celle où viennent d’émerger en Europe continentale deux formes de totalitarisme, le communisme et le national-socialisme, qui sont, pour reprendre le vocabulaire de Guy Debord, des “sociétés du spectacle spectaculaire”, du spectacle hystérique. Le 1984 le reproduira tout en le caricaturant à l’extrême, lui donnant finalement une “coloration” plus communiste que nationale-socialiste, aussi parce que le communisme soviétique survit à l’élimination du national-socialisme, suite à la défaite allemande de 1945. Orwell ne connaît pas encore le “spectacle diffus”, dénoncé par Debord dans les années 60, ni le “festivisme”, fustigé par Philippe Muray dans les années 90 et les premières années du 21ème siècle, où l’essentiel, le “politique politique” (Julien Freund), est submergé par des “festivités” destinées à amuser, abrutir, décérébrer et dépolitiser les masses. Le monde fictif, né de l’imagination d’Orwell, est durablement marqué par l’agitprop communiste, qui avait d’abord séduit les avant-gardes artistiques (dada, surréalisme, André Breton) dans les années 20 et 30. Pour l’Orwell de la fin des années 40, cette “agitprop” est la quintessence même de ce totalitarisme dur, constat qu’il formule après avoir eu derrière lui une existence de militant de gauche, fidèle et inébranlable, qui a participé à toutes les mésaventures des gauches radicales anglaises, s’est engagé dans les milices anarchistes de Barcelone pendant la Guerre civile espagnole. Cette aventure espagnole le rapprochera d’Arthur Koestler, lui aussi protagoniste de la guerre civile espagnole (cf. Le testament espagnol). Koestler rompt ensuite avec les services du Komintern, qu’il avait pieusement servi, notamment sous l’égide de Willy Münzenberg, un communiste allemand exilé à Paris, chargé par les instances moscovites d’organiser en Occident une propagande soviétique bien conforme aux directives du “Politburo” dirigé par Staline.

Willy Münzenberg et la guerre civile espagnole

A Paris, Willy Münzenberg orchestre toute la propagande soviétique antinazie et antifasciste. Lors de l’incendie du Reichstag, il est chargé de propager la version communiste des faits, au besoin en travestissant la réalité. De même, lors de la guerre d’Espagne, il fait fabriquer par ses services des brochures de propagande où les faits sont enrobés d’inventions et de mensonges délibérés de manière à susciter des vocations militantes et à couvrir l’adversaire d’opprobre. Koestler, dans son autobiographie, décrit parfaitement l’atmosphère qui régnait dans les officines parisiennes du Komintern sous la direction de Münzenberg. L’objectif était de faire éclore, dans le vaste public, la vision d’un monde manichéen où une bonne gauche, parée de toutes les vertus, et dont les communistes étaient l’avant-garde, s’opposerait dans un combat planétaire à une méchante droite, dont la perversité culminerait dans les régimes dits “fascistes” d’Allemagne, d’Italie ou d’Espagne. Pourtant, ce tableau en noir et blanc n’a jamais correspondu à aucune réalité du conflit civil espagnol: les gauches, unies selon la propagande, vont au contraire s’entre-déchirer à Barcelone et faire crouler le front catalan du “Frente Popular”, scellant définitivement le sort de la République espagnole. Orwell a été un témoin direct des événements: il a vu et entendu les communistes espagnols et étrangers enclencher une propagande virulente et dénigrante contre les autres formations de gauche.

A Paris, Willy Münzenberg orchestre toute la propagande soviétique antinazie et antifasciste. Lors de l’incendie du Reichstag, il est chargé de propager la version communiste des faits, au besoin en travestissant la réalité. De même, lors de la guerre d’Espagne, il fait fabriquer par ses services des brochures de propagande où les faits sont enrobés d’inventions et de mensonges délibérés de manière à susciter des vocations militantes et à couvrir l’adversaire d’opprobre. Koestler, dans son autobiographie, décrit parfaitement l’atmosphère qui régnait dans les officines parisiennes du Komintern sous la direction de Münzenberg. L’objectif était de faire éclore, dans le vaste public, la vision d’un monde manichéen où une bonne gauche, parée de toutes les vertus, et dont les communistes étaient l’avant-garde, s’opposerait dans un combat planétaire à une méchante droite, dont la perversité culminerait dans les régimes dits “fascistes” d’Allemagne, d’Italie ou d’Espagne. Pourtant, ce tableau en noir et blanc n’a jamais correspondu à aucune réalité du conflit civil espagnol: les gauches, unies selon la propagande, vont au contraire s’entre-déchirer à Barcelone et faire crouler le front catalan du “Frente Popular”, scellant définitivement le sort de la République espagnole. Orwell a été un témoin direct des événements: il a vu et entendu les communistes espagnols et étrangers enclencher une propagande virulente et dénigrante contre les autres formations de gauche.

C’est dans ce contexte qu’est née la fameuse expression, qui a tant fait sourire, de “vipères lubriques hitléro-trotskistes”. Orwell, blessé après un combat contre les troupes franquistes, doit fuir la métropole catalane, à peine sorti de l’hôpital, pour échapper aux équipes d’épurateurs communistes, chassant les anarchistes, les militants du POUM et les trotskistes, qui formaient le gros des troupes irrégulières de la République espagnole et des autonomistes catalans. En posant l’équation entre hitlériens et trotskistes, le manichéisme propagandiste des communistes visait à faire passer les forces de la gauche non communiste dans le même camp que les adversaires les plus radicaux du Komintern: dans le mental de la propagande, comme dans celui de la “political correctness” actuelle, il ne peut y avoir de demies teintes. Il y a toujours des “gentils”, des “purs”, et des “affreux”, des “âmes noires”. La propagande communiste, hostile aux autres gauches, et le vocabulaire hystérique et dénigrant qu’elle utilisait, vont donner à Orwell l’idée du “quart d’heure de la haine”, qu’il mettra en scène dans 1984. Les historiens actuels de la guerre civile espagnole, comme Pio Moa et Arnaud Imatz, démontrent que la République a implosé, à cause de cette guerre civile dans la guerre civile: un fait d’histoire que toutes les gauches vont tenter de camoufler après la victoire des armées de Franco, renouant avec les lignes directrices de la propagande orchestrée par Münzenberg, avant le pacte germano-soviétique d’août 1939. Travestir et camoufler la réalité deviennent des agissements politiques courants, appelés à s’amplifier considérablement au fur et à mesure que les moyens techniques se perfectionnent, aboutissant à une oblitération de plus en plus accentuée des réalités concrètes.

1936: année cruciale

Pour Orwell, 1936 est une année cruciale. Simon Leys, dans son livre Orwell ou l’horreur de la politique, rappelle un extrait de Looking Back on the Spanish War, où Orwell se souvient avoir eu une conversation sur la guerre civile espagnole avec Arthur Koestler où il aurait dit: “L’Histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936”. Pourquoi? Parce que, pour la première fois, Orwell a vu des articles de journaux, relatant les événements du front, “qui n’avaient absolument plus aucun rapport avec la réalité des faits”. Et il ajoutait: “Je vis des descriptions de grandes batailles situées là où nul combat n’avait pris place, tandis que des engagements qui avaient coûté la vie à des centaines d’hommes étaient entièrement passés sous silence. Je vis des troupes qui avaient courageusement combattu, accusées de trahison et de lâcheté, et d’autres qui n’avaient jamais vu le feu, acclamées pour leurs victoires imaginaires”. Pire: “je vis (...) des intellectuels zélés édifier toute une superstructure d’émotions sur des événements qui ne s’étaient jamais produits. Je vis en fait l’Histoire qui s’écrivait non pas suivant ce qui s’était passé, mais suivant ce qui aurait dû se passer, selon les diverses lignes officielles”.

Aujourd’hui, force est de constater que les techniques de propagande mises au point par Münzenberg pour le compte du Komintern dans les années 30 du 20ème siècle sont toujours les mêmes, sauf qu’elles ne sont plus diffusées par des communistes mais par les agences de presse américaines: on se souvient des “couveuses de Koweit City” en 1990, on se souvient des “quarts d’heure de haine” aboyés par Shea, le porte-paroles de l’OTAN à accent “cockney” lors de la guerre contre la Serbie en 1999; en Crimée, aujourd’hui, le ton est quelque peu édulcoré car aux Etats-Unis mêmes, l’opposition à toutes les guerres extérieures déclenchées par le Pentagone est plus largement répandue, surtout sur la grande toile, que dans les années 20 et 30 où certains républicains, avec le Sénateur Taft, et les populistes, autour du père et du fils LaFollette, s’étaient opposés au bellicisme hypocrite des Présidents Wilson et Roosevelt, camouflé derrière un verbiage pacifiste, moraliste et “démocratique”.

Si Shea n’a jamais été qu’un acteur bien payé pour éructer son “quart d’heure de haine” contre les Serbes en 1999 puis a été congédié mission accomplie pour aller amorcer ailleurs une autre comédie dûment stipendiée, Münzenberg, lui, croyait au message communiste. Il a été broyé par la propagande qu’il avait lui-même mise en place. Münzenberg était pour l’union des gauches contre le fascisme, pour l’alliance Paris-Prague-Moscou de 1935 (qui, en Belgique, a suscité tant de craintes que les accords militaires franco-belges ont été rompus par le Roi, que la neutralité a été à nouveau proclamée en octobre 1936 et que de larges strates de l’opinion publique disaient préférer “Berlin” à “Moscou”), pour l’union de toutes les gauches dures contre Franco. Son propre parti va finir par refuser cette politique unitaire qu’il avait pourtant préconisée avec insistance et à laquelle Münzenberg avait voué toutes ses forces. Au lendemain de la guerre civile espagnole, le Pacte Ribbentrop-Molotov déstabilise complètement les communistes qui avaient confondu leur combat avec l’antifascisme et l’antinazisme, quitte à s’allier à des éléments gauchistes, considérés, dans les écrits de Lénine, comme les vecteurs de la “maladie infantile du communisme”. La direction stalinienne, au lendemain de la guerre d’Espagne et de la victoire de Franco, en vient à considérer l’antifascisme et l’antinazisme comme des positions immatures, propres du “gauchisme” stigmatisé par Lénine. Willy Münzenberg, qui avait plaidé pour un large front des gauches, englobant les socialistes et les gauchistes, se rebiffe et écrit un pamphlet intitulé “Le coup de poignard russe”, fustigeant, bien entendu, le retournement stalinien et l’alliance tactique (purement tactique) avec l’Allemagne nationale-socialiste. Il tombe en disgrâce, disparaît, sans doute enlevé par des agents du Komintern. On retrouvera son corps pendu à un arbre dans une forêt de la région de Grenoble.

Roubachov et la ferme des animaux

Arthur Koestler relate dans ses mémoires cet épisode où les militants internationalistes du Komintern tombent dans le désarroi le plus complet après les événements de Barcelone —la guerre civile dans la guerre civile— et le Pacte Ribbentrop-Molotov. Ce retournement a lieu au moment le plus fort et le plus tragique des purges de Moscou, où de vieux militants bolcheviques sont éliminés parce qu’ils ne sont plus au diapason de la politique nouvelle amorcée par l’Union Soviétique. Les purges staliniennes en Union Soviétique forment la toile de fond du plus célèbre roman de Koestler, Darkness at Noon (en français: Le Zéro et l’infini). Le personnage central et fictif de ce roman s’appelle Roubachov: il est emprisonné, attend son jugement, sa condamnation à mort (pour le bien de la révolution) et son exécution; il avait été un révolutionnaire naïf et enthousiaste, criminel à ses heures comme tous ses semblables mais toujours animé de bonnes intentions à l’endroit du prolétariat. Aucune révolution n’est toutefois possible sans militants de ce type dont la naïveté correspond parfois à celle de la common decency d’Orwell, à l’honnêteté foncière du bon peuple qui trime et qui souffre, à la bravoure naïve du cheval dans La ferme des animaux, incarnation du prolétariat qui donne son sang sans calculer, au contraire des intellectuels et des théoriciens qui aspirent à toujours plus de pouvoirs, comme les cochons d’Animal Farm.

Arthur Koestler relate dans ses mémoires cet épisode où les militants internationalistes du Komintern tombent dans le désarroi le plus complet après les événements de Barcelone —la guerre civile dans la guerre civile— et le Pacte Ribbentrop-Molotov. Ce retournement a lieu au moment le plus fort et le plus tragique des purges de Moscou, où de vieux militants bolcheviques sont éliminés parce qu’ils ne sont plus au diapason de la politique nouvelle amorcée par l’Union Soviétique. Les purges staliniennes en Union Soviétique forment la toile de fond du plus célèbre roman de Koestler, Darkness at Noon (en français: Le Zéro et l’infini). Le personnage central et fictif de ce roman s’appelle Roubachov: il est emprisonné, attend son jugement, sa condamnation à mort (pour le bien de la révolution) et son exécution; il avait été un révolutionnaire naïf et enthousiaste, criminel à ses heures comme tous ses semblables mais toujours animé de bonnes intentions à l’endroit du prolétariat. Aucune révolution n’est toutefois possible sans militants de ce type dont la naïveté correspond parfois à celle de la common decency d’Orwell, à l’honnêteté foncière du bon peuple qui trime et qui souffre, à la bravoure naïve du cheval dans La ferme des animaux, incarnation du prolétariat qui donne son sang sans calculer, au contraire des intellectuels et des théoriciens qui aspirent à toujours plus de pouvoirs, comme les cochons d’Animal Farm.

Münzenberg dans la réalité, Roubachov dans la fiction, sont des personnalités broyées, des enfants de la révolution dévorés par elle qui, erratique, cherche sa voie dans les méandres d’un réel, qu’elle rejette et qu’elle critique toute en s’affirmant “matérialiste historique”, tout en énonçant des discours simplificateurs, réductionnistes et outranciers. Ces personnalités sont broyées parce que, quelque part, elles demeurent, ontologiquement, les réceptacles naturels et inévitables d’une diversité réelle, héritée de leur famille, de leurs proches, de leurs amis d’enfance et du patrimoine du peuple dont elles sont issues. Elles sont aussi le réceptacle de sentiments diffus ou réels de fidélité que ne comprennent pas, ne veulent pas ou plus comprendre, les langages propagandistes. Ceux-ci ne peuvent exprimer cette fidélité des anciens pour les autres anciens, qui se cristallise au-delà de la détention et de l’exercice d’un pouvoir arraché aux maîtres des vieux mondes, au paysan ivrogne de la Ferme des animaux. Qui dit fidélité dit souvenir d’un passé héroïque ou glorieux, tissé de souffrances et de combats, d’efforts et de deuils. Qui dit passé dit frein à la marche en avant vers un progrès certes hypothétique, pour tous ceux qui gardent lucidité, mais posé comme “telos” inévitable de la politique par les nouveaux maîtres du pays. Pour ne pas être broyées, les personnalités révolutionnaires ou politiques doivent OUBLIER. Oublier le passé de leur peuple, oublier leur propre passé personnel, oublier leurs amis et camarades, avec qui ils avaient combattu et souffert. Dans l’univers de la politique totalitaire du communisme de mouture soviétique ou même de la politique démocratique des partis triviaux et corrompus de l’univers libéral décadent, le militant, le permanent, le candidat doivent se mettre volontairement ou inconsciemment en état d’oubli permanent et cela, sans RETARD aucun par rapport aux décisions ou aux orientations formulées par un très petit état-major de chefs ou d’intrigants, inconnus de la base militante ou de l’électeur.

Malheur aux personnalités “retardatrices”!

Si une personnalité marque un retard, elle est aussitôt posée comme “retardatrice” de l’avènement du “télos” ultime ou comme un élément passéiste et redondant, “ringard”. Dans ce cas, elle est éliminée de la course aux pouvoirs ou aux prébendes, dans les démocraties partitocratiques comme les nôtres. Dans les systèmes totalitaires, elle est liquidée physiquement ou “évaporée” comme dans le 1984 d’Orwell. Dans la Russie stalinienne, on gommait sur les photos des temps héroïques de la révolution russe la personne de Trotski, comme on efface toute trace concrète de l’hypothétique Goldstein dans le roman d’Orwell pour n’en maintenir que l’image très négativisée, générée par la propagande. Dans les démocraties libérales, on houspille hors de portée des feux de rampe médiatiques les gêneurs, les esprits critiques, les candidats malheureux, les dissidents qui ne formulent pas d’utopies irréelles mais se réfèrent au seul réel tangible qui soit, celui que nous lègue l’histoire réelle et tumultueuse des peuples. Ils subissent la conspiration du silence.

◊ 2. Les manipulations de la langue:

Orwell s’est toujours méfié instinctivement des volontés d’aseptiser la langue, de l’enfermer dans la cangue des propagandes. Ce jeu pervers qui s’exerce sur la langue n’est pas nécessairement une stratégie mise en oeuvre par les totalitarismes politiques, ceux qui procèdent du totalitarisme spectaculaire et tapageur, mais aussi du démocratisme libéral, que l’on peut aujourd’hui, sans guère d’hésitation, camper comme un totalitarisme mou ou diffus, bien plus subtil que les régimes forts ou autoritaires.

La première forme de fabrication linguistique qui hérisse Orwell est l’esperanto du mouvement espérantiste qu’anime à Paris le mari de sa tante qui y réside et qui l’héberge parfois quand il enquête sur les bas-fonds de la capitale française, prélude à son oeuvre poignante Dans la dèche à Londres et à Paris. Orwell juge farfelue l’idée de “fabriquer une langue” car une telle fabrication n’aurait pas de passé, pas d’histoire, pas de mémoire et sa généralisation provoquerait un refoulement général de tous les legs de l’humanité, plus personne n’étant alors capable de les comprendre.

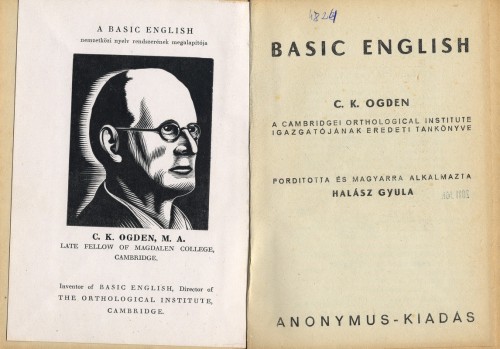

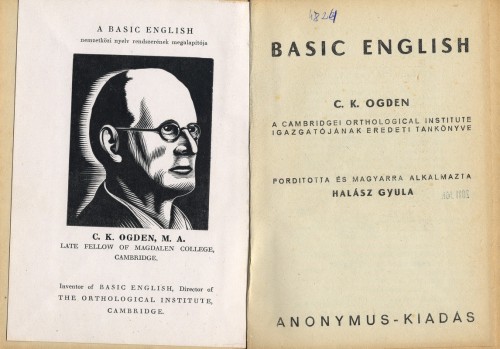

Esperanto et “basic English”

Mais si les efforts des espérantistes, observés avec ironie par Orwell, n’ont pas été couronnés de succès, la généralisation du “basic English”, sous l’impulsion du tandem anglo-américain à partir des années 40, réussira à créer une koinè d’abord pour les peuples de l’Empire britannique puis pour tous les peuples plus ou moins inféodés à la sphère d’influence anglo-saxonne. Le coup d’envoi pour promouvoir cet anglais simplifié est donné en 1940, quand Orwell a déjà derrière le dos deux expériences, importantes pour la maturation de son oeuvre et de sa pensée: les efforts dérisoires des espérantistes, dont son oncle par alliance, et les jeux langagiers pervers et violents de la propagande communiste anti-gauchiste de Barcelone pendant la guerre civile espagnole. Il retient que le langage ne peut procéder de simples fabrications et qu’il doit toujours dire le réel et non pas l’oblitérer par des affirmations propagandistes péremptoires.

Quand les autorités britanniques lancent le projet, leur but premier —et purement pragmatique— est d’instruire les soldats indiens et africains qui vont être enrôlés dans les armées britanniques pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, tout comme aujourd’hui ce “basic English” des armées sert à instruire les soldats d’Afrique francophone dans le cadre de l’Africom, instance militaro-civile visant à arracher les pays africains de toute influence non américaine, qu’elle soit française ou chinoise. Le Rwanda, ancienne colonie allemande, devenue protectorat belge après 1918 et donc francophone, est désormais inclus dans la sphère de l’Afrique anglophone. L’objectif du “basic English” est donc d’instruire des étrangers, d’abord des soldats puis des cadres civils ou des interlocuteurs commerciaux, non plus seulement dans l’Empire britannique mais dans les pays européens ou asiatiques libérés par les armées anglo-saxonnes et appelés à devenir des comptoirs commerciaux ou des débouchés pour les productions industrielles américaines surtout, britanniques dans une moindre mesure. Dès le départ, le projet de répandre un “basic English” reçoit l’appui de Winston Churchill, adepte et signataire de la “Charte atlantique” de 1941, laquelle visait à faire advenir à terme “an English speaking world”. Cette année-là, Orwell travaille à la BBC et, dans une première phase, semble adhérer à ce projet vu qu’il plaidait pour une langue littéraire et journalistique “limpide”, capable d’exprimer le réel sans détours, sans masques, sans fioritures inutiles, avec tout à la fois une simplicité et une densité populaires, dépourvues d’ornements pompeux ou de redondances gratuites, propres à une littérature plus bourgeoise. Au bout de quelques mois, Orwell est horrifié. Il exprimera son désaccord fondamental dans un texte intitulé Politics and the Englih language. Orwell constate que l’on cherche à réduire le vocabulaire à 850 mots, que l’on simplifie la syntaxe outrancièrement, projet qui est toujours d’actualité car les universités britanniques prestigieuses, comme Oxford et Cambridge, qui ont produit jusqu’ici les meilleurs manuels d’apprentissage de la langue anglaise, cherchent désormais, depuis début 2013, à lancer sur le marché des méthodes préconisant un enseignement de l’anglais “as it is really spoken”, englobant avec bienveillance les erreurs, parfois grossières, généralement commises par les étrangers, les Afro-Américains, les classes défavorisées du Royaume-Uni ou des Etats-Unis, les non anglophones du tiers-monde vaguement frottés à l’anglais. Le “basic English” des années quarante semble encore trop compliqué pour faire advenir l’English speaking world donc, pour favoriser plus rapidement son avènement, on est prêt à généraliser sur la planète entière un affreux baragouin imprécis et filandreux! Les écoles belges n’ont heureusement pas adopté ces nouvelles méthodes! Mais ce n’est sans doute que partie remise!

Détruire la transmission intergénérationnelle

Pour Churchill, ce “basic English” était l’“arme la plus terrifiante de l’ère moderne” puisqu’elle allait faire imploser de l’intérieur les polities non anglophones et détruire les môles de résistance, appuyés sur les legs du passé, dans les pays de langue anglaise eux-mêmes. Trois professeurs, Ogden, Richards et Graham, et les services de l’Université de Harvard vont alors tenter de structurer ce projet politique et linguistique de grande envergure que la politique soviétique avait anticipé quand elle avait progressivement remplacé le russe impérial par une langue soviétisée et appauvrie ou quand le jargon politisé du Troisième Reich oblitérait la langue allemande par ce que Viktor Klemperer a nommé la LTI, la lingua terterii imperii, la langue du “Troisième Reich”. Soljénitsyne, emprisonné à Moscou après la seconde guerre mondiale, avait mesuré, avec ses co-détenus, l’ampleur de cet affadissement et de cette mutilation linguistique subie par sa langue maternelle. Son oeuvre ultérieure a visé, entre bien d’autres choses, à restaurer les espaces sémantiques mutilés par la soviétisation. Mais la vision d’un “basic English” comme “arme terrifiante” à appliquer au monde anglo-saxon et à tous les espaces qu’il allait satelliser, ne nous permet plus, objectivement, en tenant compte des démarches d’Orwell, de limiter aux seuls régimes totalitaires la volonté de mutiler et de travestir les langues. La soviétisation, la LTI de Klemperer et la mise en oeuvre planétaire du “basic English”, avec l’appui enthousiaste de Winston Churchill, démontrent une commune volonté (au bolchevisme et à l’américanisme) de redéfinir en permanence la langue quotidienne du peuple, la langue de la transmission intergénérationnelle, de façon à ce qu’une politie, portée normalement par le mos majorum, soit atomisée, pulvérisée donc subrepticement exterminée.

Ce type de démarche s’observe également dans les rédactions successives des dictionnaires usuels: si l’on lit les définitions proposées par des dictionnaires d’avant 1914, de l’entre-deux-guerres, des années 50 et 60, on constate, très souvent, qu’elles ne concordent plus exactement avec celles suggérées aujourd’hui. Par ailleurs, bon nombre de vocables ont disparu ou leur plage sémantique s’est réduite, un grand nombre d’expressions populaires, de tournures de phrases propres au langage coloré (argotique, dialectal ou patoisant) de la population se sont effacées, sont tombées en désuétude. Ce sont là les indices d’une volonté politique d’appauvrissement général de la langue mais qui échoue, en ultime instance, parce que la littérature existante rappelle sans cesse des notions anciennes, des nuances oubliées mais revenues, crée des nouveaux mots, recourt aux argots, aux anciens patois, aux dialectes. L’anglais et les autres langues soumises, elles aussi, à manipulations retorses, restent riches, se complexifient en dépit des prophètes de l’hyper-simplification: le “best-seller” international de l’an dernier, le livre intitulé The Sleepwalkers de l’historien australien Christopher Clark, consacré aux prolégomènes de la première guerre mondiale, est l’exemple même d’un livre clair au vocabulaire riche et varié, réintroduisant des termes absents voire évacués du “basic English”.

Du totalitarisme dur au totalitarisme mou

Le “basic English” d’Ogden n’est donc pas une entreprise communiste mais une entreprise libérale et démocratique prouvant que les régimes de cette sorte ne sont nullement immunisés contre la tentation de lobotomiser leurs citoyens en réduisant la portée sémantique de leurs langues quotidiennes. C’est l’indice du passage du totalitarisme dur et spectaculaire au totalitarisme diffus et “incontestable”, dans la mesure où il ne peut plus être contesté puisqu’il est derechef campé comme “boniste” (disent aujourd’hui nos amis italiens) et comme intrinsèquement “démocratique” au sens de la Charte de l’Atlantique de 1941, laquelle représenterait l’optimum d’entre les optima et ne saurait dès lors subir la moindre critique.

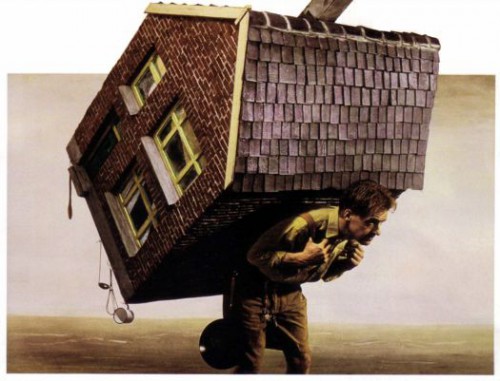

Orwell a encore cru, dans les années noires de l’immédiat après-guerre, que les politiques contrôlantes allaient déboucher, en Occident atlantique aussi, sur une langue comme celle de son roman 1984. Il craignait l’avènement d’un totalitarisme pareil à celui de son “Oceania” imaginaire. Non, les manipulateurs et les propagandistes ont introduit dans leur stratégie linguistique oblitérante, surplombant le réel jugé imparfait et donc mauvais, d’autres ingrédients que le jargon propagandiste soviétique, que la langue de bois communiste ou autres perversions sémantiques similaires. Ces ingrédients sont ceux qu’Aldous Huxley avait envisagés dans Brave New World et Brave New World Revisited où la lobotomisation des esprits s’effectue par les drogues et la promiscuité sexuelle, artifices destinés à faire oublier le rôle majeur et incontournable de l’homme en tant que zoon politikon. Le camé et le frénétique de la quéquette s’agitent de manière compulsive sans se soucier de la Cité, sans ressentir ce que Heidegger nommait la Sorge. Avec la mode hippy puis le festivisme (Muray), qui s’en suivirent à partir des années 60, l’emprise des instances contrôlantes s’est renforcée sans en avoir l’air, provoquant à terme l’implosion des polities non hégémoniques, ou réduisant à néant les contestations au sein de l’hegemon lui-même, et la ruine des “Etats profonds” en Europe. Nous avons aujourd’hui la juxtaposition d’un festivisme impolitique —où les faits de monde, dont tout zoon politikon attentif devrait se soucier, sont délibérément noyés sous un torrent de discours ou d’images ineptes mais amusants— et de propagandes hyper-simplificatrices, très souvent guerrières quand Oceania (ou, dans notre réel, la “Communauté atlantique des valeurs”) entre en guerre contre un ennemi quelconque, qu’il s’agit de décrire non pas tel qu’il est vraiment mais tel un croquemitaine chimérique véhiculant tous les aspects du “Mal” avec un grand M. Ces discours, images et propagandes doivent induire les masses à toujours ignorer les faits du monde réel, à ne pas percevoir les interstices qui permettraient la paix ou les négociations.

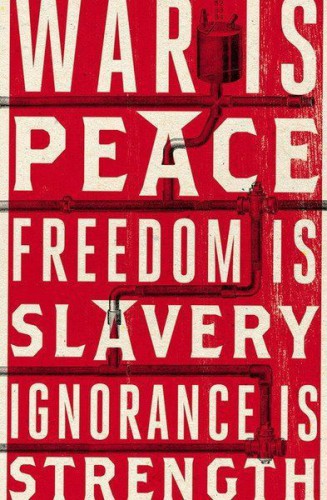

De l’amphibologie

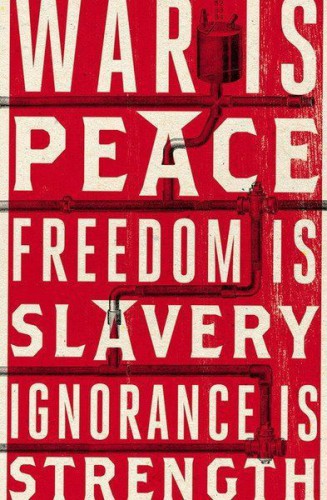

C’est en ce sens qu’il faut interpréter le slogan de la propagande d’Oceania dans le 1984 d’Orwell: l’IGNORANCE, c’est la FORCE. L’ignorance, donc la force puisqu’il y a équation entre les deux termes, est générée par l’éradication de tous les souvenirs du passé, par l’éradication de la mémoire parce que la mémoire peut toujours constituer un môle de résistance face aux propagandes. La mémoire est donc une force qu’il faut percevoir comme s’opposant en tout temps et en tout lieu aux propagandes éradicatrices et oblitérantes. L’ignorance est aussi générée par la création d’une langue épurée à l’extrême, qui cherche à réduire voire à effacer ce que le penseur espagnol Eugenio d’Ors (1) nommait l’amphibologie de tous les termes du vocabulaire d’une langue. L’amphibologie, c’est la richesse sémantique des mots, richesse largement extensible, dans la mesure où tout mot peut acquérir des significations nouvelles par l’art du poète ou du littérateur, par l’imagination truculente et gouailleuse des classes populaires et des titis déclassés. L’amphibologie est donc la marque majeure de la langue ancienne par rapport à la langue nouvelle fabriquée qu’Orwell nomme la “novlangue” (newspeak) et qu’il définit dans les chapitres 4 et 5 de 1984 et dans un appendice au livre qui lui est entièrement consacré. Orwell définit dans ces chapitres et cet appendice un langage contrôlé et fabriqué par un Etat totalitaire pour en faire un instrument qui limitera la liberté de pensée (qui passe par le maintien de l’amphibologie du vocabulaire) et qui jugulera la liberté politique, l’expression de soi, formatera les individualités et les personnalités et éradiquera la prédisposition des hommes quiets et normaux à vouloir la paix, c’est à dire à vouloir un pacifisme qui n’est autre que l’expression de leur bon sens.

C’est en ce sens qu’il faut interpréter le slogan de la propagande d’Oceania dans le 1984 d’Orwell: l’IGNORANCE, c’est la FORCE. L’ignorance, donc la force puisqu’il y a équation entre les deux termes, est générée par l’éradication de tous les souvenirs du passé, par l’éradication de la mémoire parce que la mémoire peut toujours constituer un môle de résistance face aux propagandes. La mémoire est donc une force qu’il faut percevoir comme s’opposant en tout temps et en tout lieu aux propagandes éradicatrices et oblitérantes. L’ignorance est aussi générée par la création d’une langue épurée à l’extrême, qui cherche à réduire voire à effacer ce que le penseur espagnol Eugenio d’Ors (1) nommait l’amphibologie de tous les termes du vocabulaire d’une langue. L’amphibologie, c’est la richesse sémantique des mots, richesse largement extensible, dans la mesure où tout mot peut acquérir des significations nouvelles par l’art du poète ou du littérateur, par l’imagination truculente et gouailleuse des classes populaires et des titis déclassés. L’amphibologie est donc la marque majeure de la langue ancienne par rapport à la langue nouvelle fabriquée qu’Orwell nomme la “novlangue” (newspeak) et qu’il définit dans les chapitres 4 et 5 de 1984 et dans un appendice au livre qui lui est entièrement consacré. Orwell définit dans ces chapitres et cet appendice un langage contrôlé et fabriqué par un Etat totalitaire pour en faire un instrument qui limitera la liberté de pensée (qui passe par le maintien de l’amphibologie du vocabulaire) et qui jugulera la liberté politique, l’expression de soi, formatera les individualités et les personnalités et éradiquera la prédisposition des hommes quiets et normaux à vouloir la paix, c’est à dire à vouloir un pacifisme qui n’est autre que l’expression de leur bon sens.

Georges Orwell et Simone Weil

A ce propos deux remarques et digressions: 1) la “political correctness”, en tant qu’avatar non romanesque de la novlangue orwellienne, interdit tout renouvellement des champs politiques dans les pays qui s’y soumettent et interdit toute forme de pacifisme et de neutralité quand l’Oceania réelle de notre échiquier politique international, soit la “Communauté atlantique des valeurs”, décide de partir en guerre contre un Etat dont elle fait sa victime, et qui est alors immanquablement posé comme “voyou”; 2) à la suite d’Orwell, le formatage systématique des esprits est généralement prêté aux seuls régimes totalitaires et spectaculaires; pour Simone Weil, volontaire pour servir comme infirmière dans une ambulance anarchiste sur le front de Barcelone pendant la guerre civile espagnole, tous les partis politiques, quelle que soit leur obédience, quel que soit le signe idéologique sous lequel ils se placent, formatent les esprits qui, d’une manière ou d’une autre, se soumettent à leur bon vouloir. Simone Weil était très dure à l’endroit des partis politiques, plus dure même que certains théoriciens étiquetés autoritaires (2): elle réclamait leur suppression pure et simple, comme mesure de salut public, justement parce qu’ils enrégimentaient les âmes et ôtaient au citoyen son libre arbitre. Pour elle, l’ensemble des partis dans un pays force les citoyens à élire des “collectivités irresponsables” qui n’ont aucune relation tangible avec la volonté générale; citations: “les partis sont des organismes publiquement, officiellement constitués de manière à tuer dans les âmes le sens de la vérité et de la justice”; “en entrant dans un parti, on renonce à chercher uniquement le bien public et la justice”; “chaque parti est une petite Eglise profane armée de la menace d’excommunication”. Le PC soviétique avait exclu et gommé Trotski, exécuté la vieille garde bolchevique (pour nostalgie gauchiste de la révolution), le parti fictif du roman de Koestler Darkness at Noon (Le Zéro et l’Infini) va tuer Roubachov: ce sont là, en dimension macroscopique et sanguinaire, les mêmes phénomènes que les petites épurations mesquines qui émaillent la vie quotidienne de nos partis politiques et trouvent leur point culminant dans les exclusions des listes électorales à la veille des élections, le PS et le CdH wallons viennent d’ailleurs d’en donner l’exemple juste avant le scrutin à venir de mai 2014. L’écrivain et journaliste anglais Orwell et la petite philosophe juive et française Weil ont tous deux servi sur le front républicain de Catalogne, l’un comme combattant anarchiste, l’autre comme infirmière volontaire. Tous deux sont sortis de cette aventure espagnole avec un dégoût profond de la politique politicienne et partisane, des outrances verbales de la propagande communiste. Tous deux nous lèguent aujourd’hui les recettes pour nous donner la force intérieure (Weil est très explicite à ce sujet) de résister aux sirènes des politicailleries sordides, quelles qu’elles soient. Avec leurs conseils et leurs constats, nous pourrons dans l’avenir construire le pôle de rétivité, nécessaire pour sortir des torpeurs du système, de ses enfermements et du pourrissoir auquel il nous condamne.

A ce propos deux remarques et digressions: 1) la “political correctness”, en tant qu’avatar non romanesque de la novlangue orwellienne, interdit tout renouvellement des champs politiques dans les pays qui s’y soumettent et interdit toute forme de pacifisme et de neutralité quand l’Oceania réelle de notre échiquier politique international, soit la “Communauté atlantique des valeurs”, décide de partir en guerre contre un Etat dont elle fait sa victime, et qui est alors immanquablement posé comme “voyou”; 2) à la suite d’Orwell, le formatage systématique des esprits est généralement prêté aux seuls régimes totalitaires et spectaculaires; pour Simone Weil, volontaire pour servir comme infirmière dans une ambulance anarchiste sur le front de Barcelone pendant la guerre civile espagnole, tous les partis politiques, quelle que soit leur obédience, quel que soit le signe idéologique sous lequel ils se placent, formatent les esprits qui, d’une manière ou d’une autre, se soumettent à leur bon vouloir. Simone Weil était très dure à l’endroit des partis politiques, plus dure même que certains théoriciens étiquetés autoritaires (2): elle réclamait leur suppression pure et simple, comme mesure de salut public, justement parce qu’ils enrégimentaient les âmes et ôtaient au citoyen son libre arbitre. Pour elle, l’ensemble des partis dans un pays force les citoyens à élire des “collectivités irresponsables” qui n’ont aucune relation tangible avec la volonté générale; citations: “les partis sont des organismes publiquement, officiellement constitués de manière à tuer dans les âmes le sens de la vérité et de la justice”; “en entrant dans un parti, on renonce à chercher uniquement le bien public et la justice”; “chaque parti est une petite Eglise profane armée de la menace d’excommunication”. Le PC soviétique avait exclu et gommé Trotski, exécuté la vieille garde bolchevique (pour nostalgie gauchiste de la révolution), le parti fictif du roman de Koestler Darkness at Noon (Le Zéro et l’Infini) va tuer Roubachov: ce sont là, en dimension macroscopique et sanguinaire, les mêmes phénomènes que les petites épurations mesquines qui émaillent la vie quotidienne de nos partis politiques et trouvent leur point culminant dans les exclusions des listes électorales à la veille des élections, le PS et le CdH wallons viennent d’ailleurs d’en donner l’exemple juste avant le scrutin à venir de mai 2014. L’écrivain et journaliste anglais Orwell et la petite philosophe juive et française Weil ont tous deux servi sur le front républicain de Catalogne, l’un comme combattant anarchiste, l’autre comme infirmière volontaire. Tous deux sont sortis de cette aventure espagnole avec un dégoût profond de la politique politicienne et partisane, des outrances verbales de la propagande communiste. Tous deux nous lèguent aujourd’hui les recettes pour nous donner la force intérieure (Weil est très explicite à ce sujet) de résister aux sirènes des politicailleries sordides, quelles qu’elles soient. Avec leurs conseils et leurs constats, nous pourrons dans l’avenir construire le pôle de rétivité, nécessaire pour sortir des torpeurs du système, de ses enfermements et du pourrissoir auquel il nous condamne.

Organiser une “rétivité générale”

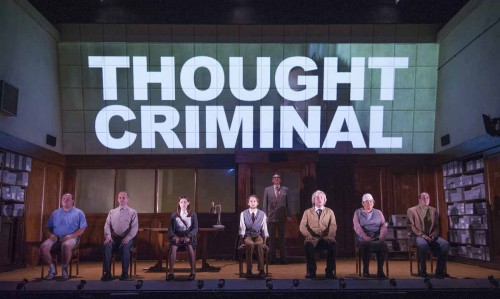

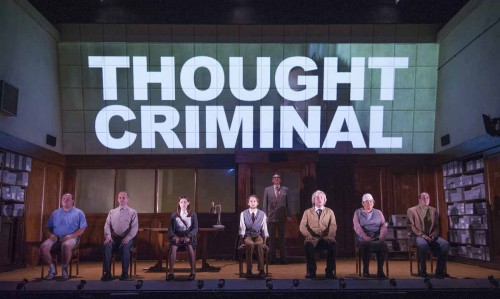

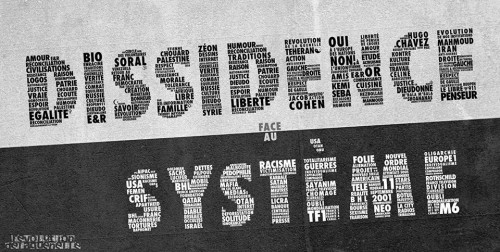

Mais organiser cette rétivité générale, voulue notamment par Michel Foucault (dans un contexte à la mode, soixante-huitard, festiviste, transgresseur et homosexuel), implique de commettre sans cesse le thoughtcrime, le crime de la pensée, d’énoncer et de pratiquer une “pensée-crime”. Cette pensée rétive, criminalisée par les chiens de garde du système, ne s’adresse plus à aucun parti totalitaire en place, car il n’y en a plus en place dans la sphère culturelle européenne ou russe, mais, comme le préconisait Simone Weil dans son exil londonien, à tous les partis, à la forme-parti. La political correctness —qui énonce ce qui est “bon”, et qu’il faut vénérer, et ce qui est thoughtcrime, et qu’il faut abhorrer— est une pensée dépourvue de rétivité, dépourvue de richesse sémantique permettant l’exercice de la rétivité, par les jeux de la langue, par la richesse du vocabulaire. Elle énonce et impose ce qu’il convient de penser et qui ne peut jamais être brocardé ou rejetté par une quelconque rétivité, fût-elle ludique à la façon des cabarets d’antan, sous peine d’excommunication ou de “correctionalisation”, de “mise en examen”. Tout thoughtcrime, toute pensée-crime, qui enfreint les règles et conventions langagières de la bienséance, de toute forme locale ou nationale de “rectitude politique”, est désormais hissé au plus haut sommet de l’inconvenance et est passible des tribunaux. En Allemagne, c’est trop souvent le délire quand on évoque des faits gênants relevant du régime national-socialiste ou des événements de la seconde guerre mondiale, alors que ces faits sont librement discutés dans d’autres pays, Russie comprise aujourd’hui. Il me paraît utile d’ajouter que dans les pays émergents, comme la Chine ou l’Inde, ces faits d’histoire européenne, vieux de sept ou huit décennies, n’émeuvent personne. Armin Mohler et Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing ont fustigé les notions de Gehirnwäsche (le “lavage des cerveaux”) et de Vergangenheitsbewältigung (littéralement: de “maîtrise forcée du passé”) qui empoisonnaient tous les débats et toutes les réflexions politiques en RFA. Pour eux, ces stratégies d’effacement des traditions et du passé émanaient en droite ligne de la politique poursuivie par les autorités d’occupation américaines.

En France, on a également assisté à des procès du plus haut ridicule, voire à des procès d’intention complètement aberrants comme l’hystérie suscitée par les derniers écrits et la candidature à l’Académie Française d’Alain Finkielkraut, alors que celui-ci avait, de conserve avec d’autres têtes d’oeuf parisiennes, prescrit des règles de “rectitude politique”, imposé des conventions médiatiques par le truchement de quarts d’heure de haine lors des affrontements inter-yougoslaves des années 90, campant de braves philologues serbes du 19ème siècle (Vuk Karadzic et Ilya Garasanin), inspirés par le philosophe germano-balte Herder, comme des figures génératrices d’horreurs sans nom, alors que Wolfgang Libal, un journaliste israélite de Vienne, spécialiste des Balkans, considérait, au même moment, ces mêmes figures comme d’admirables humanistes en lutte contre la gestion cruelle des pays serbes et bosniaques par les autorités ottomanes (cf. Wolfgang Libal, Die Serben – Blüte, Wahn und Katastrophe, Europa Verlag, München/Wien, 1996). Deux sons de cloche... L’un de pure propagande, l’autre de pure scientificité: en effet, Garasanin, d’obédience grande-serbe, voulait une protection “européenne” et non pas exclusivement russe pour les peuples balkaniques soumis à la férule ottomane. En ce sens, Garasanin était un “libéral”, hostile aux traditionalistes russes et à toute forme d’autocratie, dont Leontiev, ultra-conservateur, sera au contraire le porte-parole le plus emblématique, dans la mesure où il préférait voir les Slaves des Balkans sous un joug traditionnel musulman que sous une protection occidentale/libérale. Pour le Finkielkraut d’il y a vingt ans, ce libéral balkanique Garasanin, adepte des “autres Lumières”, celles de Herder, était, bien entendu, un précurseur du “nazisme”. C’était à une époque, bien sûr, où Finkielkraut ne glosait pas encore sur le thème de l’identité, qui l’a propulsé tout récemment à l’Académie avec l’aura d’un martyr qui avait évoqué un sujet tabou et avait été vilipendé par la bien-pensance.

En France, on a également assisté à des procès du plus haut ridicule, voire à des procès d’intention complètement aberrants comme l’hystérie suscitée par les derniers écrits et la candidature à l’Académie Française d’Alain Finkielkraut, alors que celui-ci avait, de conserve avec d’autres têtes d’oeuf parisiennes, prescrit des règles de “rectitude politique”, imposé des conventions médiatiques par le truchement de quarts d’heure de haine lors des affrontements inter-yougoslaves des années 90, campant de braves philologues serbes du 19ème siècle (Vuk Karadzic et Ilya Garasanin), inspirés par le philosophe germano-balte Herder, comme des figures génératrices d’horreurs sans nom, alors que Wolfgang Libal, un journaliste israélite de Vienne, spécialiste des Balkans, considérait, au même moment, ces mêmes figures comme d’admirables humanistes en lutte contre la gestion cruelle des pays serbes et bosniaques par les autorités ottomanes (cf. Wolfgang Libal, Die Serben – Blüte, Wahn und Katastrophe, Europa Verlag, München/Wien, 1996). Deux sons de cloche... L’un de pure propagande, l’autre de pure scientificité: en effet, Garasanin, d’obédience grande-serbe, voulait une protection “européenne” et non pas exclusivement russe pour les peuples balkaniques soumis à la férule ottomane. En ce sens, Garasanin était un “libéral”, hostile aux traditionalistes russes et à toute forme d’autocratie, dont Leontiev, ultra-conservateur, sera au contraire le porte-parole le plus emblématique, dans la mesure où il préférait voir les Slaves des Balkans sous un joug traditionnel musulman que sous une protection occidentale/libérale. Pour le Finkielkraut d’il y a vingt ans, ce libéral balkanique Garasanin, adepte des “autres Lumières”, celles de Herder, était, bien entendu, un précurseur du “nazisme”. C’était à une époque, bien sûr, où Finkielkraut ne glosait pas encore sur le thème de l’identité, qui l’a propulsé tout récemment à l’Académie avec l’aura d’un martyr qui avait évoqué un sujet tabou et avait été vilipendé par la bien-pensance.

Du vocabulaire mouvant

Grosso modo, la novlangue de 1984, possède les mêmes structures que l’anglais, que le “basic English”, tout comme le russe soviétisé de l’ère stalinienne possédait les mêmes structures que le russe impérial. Ce qui fait sa spécificité profonde, en revanche, est le shifting vocabulary, le caractère mouvant du vocabulaire, où le mot ne désigne plus une chose tangible dont l’existence doit être considérée comme intangible, non mouvante. Dans la novlangue, un concept peut être d’abord investi d’une connotation positive, comme la paix que doivent apporter des instances comme la SdN ou l’ONU. Puis subitement ce concept positif peut, dans la bouche des mêmes dirigeants et médiacrates de l’hegemon, devenir un concept négatif, chéri seulement par des trouillards, des poules mouillées d’Européens, comme quand il s’est agi de bombarder la Serbie ou d’envahir l’Irak en 2003. Tout d’un coup, les règles édictées par Roosevelt dans l’immédiat après-guerre devenaient des vieilleries retardatrices, alliées de l’Axe du Mal, qu’il fallait détruire sans attendre. De même, la défense de l’identité des peuples slaves des Balkans, théorisée par Karadzic et Garasanin au 19ème siècle était campée dans les années 90 comme un sinistre prélude théorique du nazisme, tandis que dans la première moitié de la deuxième décennie du 21ème siècle, subitement, la notion d’identité redevenait, dans la bouche du même philosophe, la valeur à défendre par-dessus tout.

La novlangue et son vocabulaire mouvant expriment donc des variations récurrentes qu’il faut tout de suite saisir au vol. Il faut se mettre à leur diapason immédiatement, sous peine de subir le sort de Roubachov ou d’être fustigé par des hyènes médiatiques ou de subir une sorte de mort civile. Les exemples abondent: les droits de l’homme avaient été moqués par toutes les gauches innovatrices dans les années 60, qui voyaient en eux l’expression d’un subjectivisme individualiste et bourgeois désuet, qui devait être remplacé par des réflexes sociaux plus “groupaux” voire plus collectivistes. Dès que Carter, Président de l’hegemon, décide d’utiliser le discours sur les droits de l’homme pour faire avancer les pions de l’Oceania du réel, soit de l’hyperpuissance américaine dans le monde, une nouvelle gauche, qui se pose avec une emphase suspecte comme plus intelligente, plus humaniste et plus subtile que toutes les autres, embraye sur ce discours et en fait la nouvelle panacée qu’on ne peut plus critiquer. Ce fut le rôle de la “nouvelle philosophie” en France, de Habermas et de ses disciples en Allemagne. Pour Simon Leys, interprète de l’oeuvre d’Orwell, c’est la manipulation d’un vocabulaire mouvant chez les activistes politiques, totalitaires comme “démocrates”, c’est la succession arbitraire et erratique des variations sémantiques du vocabulaire usuel qui ont rendu Orwell profondément allergique à la politique politicienne, à la politique partisane des mouvements et partis les plus virulents et aux langages propagandistes. Ces inconstances manipulatrices, que devinent les simples citoyens soucieux de conserver la common decency, et qu’ils rejettent par instinct, nous ont conduit à honnir, nous aussi, toutes les cliques politiciennes, de quelle qu’obédience que ce soit.

Oldspeak, newspeak et common decency

Comment doit fonctionner la novlangue dans l’esprit de ses fabricateurs? Elle commence, dit Orwell, par un appauvrissement sémantique qui procède par suppression des synonymes et antonymes (surtout quand ces antonymes ont une autre forme, une autre étymologie). La novlangue dans son travail d’hypersimplification ne veut plus utiliser qu’un seul mot, alors que le vocabulaire hérité en utilisait parfois jusqu’à vingt ou trente. Les fabricateurs de la novlangue effacent donc la luxuriance et la variété du vocabulaire, l’amphibologie des mots, mise en exergue dans l’oeuvre d’Eugenio d’Ors. L’aire d’intersection entre plages sémantiques est réduite à néant, alors que, dans une langue normale, héritée, le thesaurus, avec les synonymies et les analogies qu’il nous présente, nous montre combien la richesse lexicale est luxuriante, combien le langage peut être riche en nuances subtiles, celles que toute novlangue ou tout discours “politiquement correct” veut faire disparaître. Orwell imaginait qu’en 2050, les élites au pouvoir, les cliques politiciennes héritières du langage propagandiste des communistes et de la BBC en temps de guerre, héritières aussi des fabricateurs du “basic English”, ne parleraient plus que le newspeak, tandis que les “proles”, exclus du pouvoir réel et des médias aux ordres, conserveraient la langue ancienne, l’oldspeak, capable de toujours exprimer l’idéal orwellien de la common decency. Dans la version originale anglaise, l’élite lobotomisante comprendrait 15% de la population de la future Oceania de 2050, tandis que les “proles” déclassés formeraient le reste (85%). Masse qui permet de conserver l’espoir. Dans la traduction française, rappellent Leys et Michéa, interprètes de l’oeuvre d’Orwell, ces chiffres sont inversés: la masse est du côté des locuteurs de la newspeak, de la novlangue, tandis que seule une minorité en récession constante conserverait l’oldspeak. Une vision plus pessimiste en découle. Jamais l’erreur de traduction n’a été corrigée dans les éditions françaises.

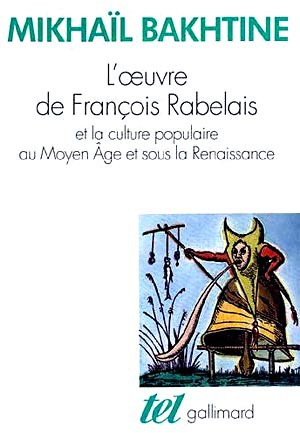

L’idée d’une différence notable entre la langue des détenteurs du pouvoir et celle des strates soumises de la population se retrouve chez le philologue et romaniste russe, Mikhaïl Bakhtine, spécialiste de Rabelais, qui évoquait la “langue du peuple sur la place du marché”, une langue gouailleuse et truculente rappelant justement celle de Rabelais, un français d’avant l’ordonnance de Villers Cotterêt d’août 1539, qui a imposé une langue administrative et centralisatrice dépouillée, forcément, de toute verve populaire. Ainsi s’oppose en France, au 16ème siècle, une langue du peuple, plastique, à une langue des élites, figée, distinction qui, selon Robert Muchembled, implique aussi une différence “idéologique” entre strates élevées et strates basses de la société, flanquée, en ce 16ème si turbulent, d’une répression de la culture populaire sous le prétexte de lutter contre la sorcellerie. Pour Muchembled, une première mise au pas de la société, lors de la première phase de la modernité, s’effectue par l’imposition d’une langue épurée et administrative et par l’éradication des croyances populaires, présentées comme relevant de la sorcellerie. Le 1984 d’Orwell, en dénonçant les tentatives soviétiques et britanniques d’anémier la langue pour les besoins d’une propagande belliciste, stigmatise une entreprise nouvelle de mise au pas de la “populité” fondamentale.

L’idée d’une différence notable entre la langue des détenteurs du pouvoir et celle des strates soumises de la population se retrouve chez le philologue et romaniste russe, Mikhaïl Bakhtine, spécialiste de Rabelais, qui évoquait la “langue du peuple sur la place du marché”, une langue gouailleuse et truculente rappelant justement celle de Rabelais, un français d’avant l’ordonnance de Villers Cotterêt d’août 1539, qui a imposé une langue administrative et centralisatrice dépouillée, forcément, de toute verve populaire. Ainsi s’oppose en France, au 16ème siècle, une langue du peuple, plastique, à une langue des élites, figée, distinction qui, selon Robert Muchembled, implique aussi une différence “idéologique” entre strates élevées et strates basses de la société, flanquée, en ce 16ème si turbulent, d’une répression de la culture populaire sous le prétexte de lutter contre la sorcellerie. Pour Muchembled, une première mise au pas de la société, lors de la première phase de la modernité, s’effectue par l’imposition d’une langue épurée et administrative et par l’éradication des croyances populaires, présentées comme relevant de la sorcellerie. Le 1984 d’Orwell, en dénonçant les tentatives soviétiques et britanniques d’anémier la langue pour les besoins d’une propagande belliciste, stigmatise une entreprise nouvelle de mise au pas de la “populité” fondamentale.

Et dans la France contemporaine?

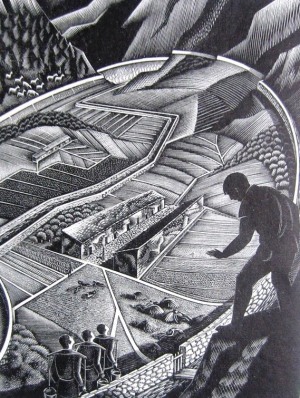

Force est de constater que les castes dirigeantes de la France actuelle articulent des discours non plus totalitaires/spectaculaires mais festivistes qui sont plus proches des méthodes hédonistes d’endormissement et d’assoupissement des instincts vitaux, imaginées par Huxley; elles participent ainsi à une entreprise hostile à la culture populaire, plus exactement hostile aux réflexes naturels d’une culture populaire fondée sur l’évidence des faits et toujours sur la common decency, qui, elle, refuse tout naturellement d’accepter comme signes d’excellence culturelle les spectacles vulgaires et sordides des femens ou des gay prides, lesquels ne sont, finalement, que des instruments destinés, une nouvelle fois, à bousculer et à marginaliser les réflexes sains du bon peuple, conformes au mos majorum, sans lequel aucune politie ne peut fonctionner, comme on le sait depuis les édits de l’Empereur Auguste. La France d’aujourd’hui est marquée par une césure mentale entre, d’une part, son peuple de base, sa populité intacte sans fioritures festivistes, et, d’autres part, ses intellocrates, médiacrates et journalistes qualifiés par Serge Halimi de “chiens de garde du système”, qui manipulent désormais la canaille crapuleuse et les dévoyés pathologiques pour se maintenir au service du pouvoir en dépit des échecs patents de celui-ci, en dépit de la faillite retentissante de ses projets idéologico-politiques. La rétivité nécessaire au maintien de toute politie —qui connait forcément l’usure du pouvoir et les affres d’un déclin inexorable, toujours à l’oeuvre, dû au facteur “temps”— vient en fait de quitter l’espace réduit des marginalités criminelles, sociales ou sexuelles où Genet et Foucault voulaient la confiner tout en voulant renforcer l’impact de ces marginalités et leur donner des micro-pouvoirs de remplacement, pour faire, pensaient-ils dès les années 60, de tous les marginaux possibles et imaginables une sorte de caste de nouveaux élus, tout en dénonçant les mises au pas antérieures, dont celles amorcées à l’âge des Lumières, à la fin du 18ème. La rétivité est désormais dans le camp de la common decency, du peuple rabelaisien qui jase et persifle sur les places publiques, une common decency qui avait été battue en brèche pendant de longues décennies. Le travail de sape et de subversion commis par des élites manipulatrices, pour briser les ressorts de la société porteuse d’Etat, s’est heurté in fine à des instincts inamovibles, qui, face aux agissements des “rétifs de cours”, des faux rétifs, des pseudo-rétifs tolérés et imposés, en appellent à la “rétivité pour tous”.

Rétivité pour tous!

Une “rétivité pour tous” —apte à subvertir un ordre (plutôt un “désordre”) établi qui, lui, parie sur des marginalités pathologiques ou incongrues ou inassimilables qu’il a délibérément hissées au rang d’avatars “sublimes” de porteurs désintéressés du “révolutionisme institutionnel”—, doit forcément recourir aux formes de “populité” prémodernes, prérévolutionnaires, antérieures au grand encadrement moderne, recourir aux langues plus colorées, plus plastiques, plus réellement amphibologiques que parlait le peuple quand il n’avait encore été ni dressé par la modernité ni oblitéré par les marginalités, mises bruyamment en exergue pour étouffer ses instincts naturels et spontanés. Jules Ferry, poursuivant le travail des “Lumières modernes”, du projet du “Panopticon” des “philanthropes anglais”, proposait un enseignement uniformisateur, au nom du principe révolutionnaire de l’égalité, qui prévoyait, au nom de ce miroir aux alouettes, l’éradication des dialectes de l’Hexagone, donc d’une immense richesse sémantique, où la langue savante ou juridique, littéraire ou médiatique, pouvait sans cesse puiser pour se rénover, pour décrire le réel tangible et échapper aux réductionnismes idéologiques.

Le retour et le recours aux populités refoulées de l’Hexagone est donc un acte de “rétivité fondamentale”, de rejet des “révolutionnismes institutionalisés”, soit de toute la mascarade “républicaine” qu’avancent les gauches devenues anachroniques et répressives et que défendent encore de piètres analystes dits “de droite” qui, finalement, camouflent leur variante néfaste du “révolutionnisme libéral” et leur néo-libéralisme subversif derrière un discours bancal qui n’évoque la “République” que pour stigmatiser des incongruités et des importations religieuses incompatibles avec les anciens droits coutumiers des populations hexagonales de souche et, ainsi, pour imposer des formes sociales et économiques qui ruineront les assises des populités charnelles avec autant d’efficacité que les délires des gauches. Ou pour réitérer une vieille hostilité voltairienne-jacobine, déracinante et “ritournellique”, à toutes les formes de la religiosité autochtone. La réhabilitation des parlers populaires, le recours aux anciens dialectes, à un vocabulaire riche mais refoulé, constitue dès lors une révolution plus profonde que si elle n’avait été que “politique”.

Un travail de retour aux sources vives de la langue

En effet, la prise en compte de la critique orwellienne dans son ensemble, conjointement avec la prise en compte des écrits de Simone Weil sur l’enracinement (nécessaire) du peuple dans son passé et ses traditions, et sur le caractère néfaste des partis politiques, comme vecteurs d’ahurissements collectifs et comme instances négatrices de la liberté personnelle de jugement, doivent très logiquement nous induire à amorcer un travail de retour aux sources vives de la langue, comme l’a fait aussi un Soljénitsyne, pour le russe, dès les premières années de son emprisonnement. Ce recours aux langages vivants, aux étymologies, doit s’accompagner d’un dressage des citoyens à la méfiance et à la vigilance à l’endroit de toutes les élites politiciennes, lesquelles —il faut sans cesse le rappeler— ne s’engagent que par ressentiment à l’encontre des réalités concrètes qui ne leur offrent rien: elles espèrent simplement que leurs artifices langagiers, leur phraséologie, leur sophistique et leurs manigances politiciennes vont leur apporter un pouvoir que la nature leur dénie, vu leur incompétence en tous domaines concrets. La sophistique des élites politiciennes ne procède pas, comme le souligne très justement Michéa, d’une “révolte du coeur” comme celle de Charles Dickens et ne mérite dès lors aucune considération, aucun respect, rien que le mépris le plus abyssal. Enfin, le philosophe, le moraliste, dans la perspective orwellienne/weilienne, qui est aussi celle de Michéa, doit faire confiance au bon sens populaire, au common sense des Britanniques (qui aujourd’hui l’ont bel et bien perdu), à la common decency d’Orwell.

Dans le nouvel engouement pour Orwell qui se dessine dans le paysage intellectuel français contemporain, c’est Bruce Bégout qui définit de la manière la plus juste et la plus précise la notion cardinale de la critique orwellienne de la politique et des médias, celle de “décence ordinaire”.

Des effets de la novlangue

Les effets de la novlangue, sont pour Orwell, 1) de gommer et donc de perdre les expressions idiomatiques les plus savoureuses, ce qui revient à réduire le vocabulaire donc à rendre les locuteurs de cette novlangue aveugles à la richesse et à la diversité du monde réel; 2) d’introduire dans les discours politiques une rhétorique pompeuse, soutenue par une diction prétentieuse, que d’aucuns, comme Nicolas Bourgeois, avaient nommé l’“hexagonal” où la célèbre tirade dans le Cid de Corneille, “ô rage, ô désespoir, ô vieillesse ennemie”, devenait “ô stress, ô breakdown, ô sénescence aliénante”; 3) d’épurer et/ou de modifier les dictionnaires pour faire correspondre les définitions qu’ils donnent aux lubies du “politiquement correct” ou aux variations induites par le shifting vocabulary; 4) de multiplier les termes creux ou rendus creux par usage abusif; ici, il faut mentionner les usages inflationnistes des termes péjoratifs que sont “fascisme”, “nazisme”, “totalitarisme”, etc; ou des termes posés comme positifs tels “liberté”, “démocratie”, “droits de l’homme” (sans que l’on ne procède jamais plus à un travail généalogique pour en comprendre l’origine et l’émergence dans l’histoire réelle des peuples européens). Ces termes sont tous désormais utilisés comme s’il n’y avait d’eux qu’une seule et unique définition fixe et immuable, fixité et immuabilité qui n’autorisent aucun travail de généalogie (d’historia, disait Foucault), aucun travail de redéfinition, de “nuanciation”, de complètement. On est dans la croyance, dans le monde aseptisé des “croyeux”, plus dans le réel.

Orwell reste toutefois optimiste. Pour lui, la langue est là pour refléter la réalité et celle-ci ne se laisse pas effacer, en dépit des efforts parfois démesurés dont on use pour l’oblitérer, l’estomper dans les mémoires et les perceptions. Le réel revient toujours, au grand galop. La réalité ne se laisse pas figer. On revient toujours à la case départ, au common sense, “à la langue du peuple sur la place du marché” (Bakhtine).

Ministère de la vérité

Revenons aux différents aspects de la novlangue telle qu’elle a été imaginée par Orwell dans son 1984. Elle fourmille d’abréviations comme la langue soviétique ou, dans une moindre mesure, comme la langue de la NSDAP (cf. Klemperer). Les deux termes, “abréviés”, les plus connus sont l’Ingsoc (“English Socialism”) et le Minitrue (“The Ministry of Truth”, le “Ministère de la Vérité”). L’Ingsoc est l’idéologie officielle que l’on ne peut plus critiquer et le Minitrue est le ministère de la propagande qui fait triompher la vérité (mouvante selon les circonstances) de l’Ingsoc, même en cas de changement d’ennemi, de modification de la donne géopolitique (par exemple quand l’ennemi n’est plus l’Eurasia mais devient en un tournemain l’Eastasia). Il y a, dans la novlangue, produit de l’imagination romanesque d’Orwell, bien d’autres termes ou concepts révélateurs que l’on retient malheureusement un peu moins souvent malgré leur grande pertinence et leur réelle actualité. Ainsi le terme “bellyfeel”, à la fois verbe et substantif, qui désigne le sentiment d’adhésion viscéral que l’on peut ressentir à l’endroit de l’Ingsoc ou aujourd’hui à l’endroit de toutes les calembredaines hystériques de la “rectitude politique” ou des discours distillés par une gazette nauséabonde comme Le Soir à Bruxelles, spécialisé dans les discours haineux à l’endroit de la Flandre (sous tous ses aspects), de la Russie (sauf les oligarques), de l’Autriche, d’Israël, des militaires arabes, du Vatican, de l’archevêque de Malines, de la Syrie baathiste, de l’Arménie, du nazisme (imaginaire), des églises orthodoxes de Grèce, de Serbie, du monde slave ou de l’Orient, de la Chine ou de tout autre puissance ou fait social ou géopolitique qui déplait aux gauches de Washington, donc, en ultime instance, à la NSA. L’antonyme de bellyfeel est, selon les règles hypersimplificatrices de la novlangue, unbellyfeel, soit un sentiment de non-adhésion viscéral: de “feel”, “sentir” ou “ressentir”, et de “belly”, le “ventre” ou les “tripes”, les “viscères”. L’antonyme se forme par l’adjonction du préfixe “un”. Ce qui peut donner la phrase suivante: Oldthinkers unbellyfeel Ingsoc. Trois mots qui, pour Orwell, traduisent la longue phrase suivante: “Those whose ideas were formed before the Revolution cannot have a full emotional understanding of the principles of English socialism” (= “Ceux dont les idées se sont formées avant la Révolution ne peuvent comprendre émotionnellement les principes du socialisme anglais”). En bref: le bon citoyen d’Oceania (ou des pays formant la “Communauté Atlantique des Valeurs”) doit adhérer avec émotion, avec compassion (la “République compassionnelle”) aux idées que distillent les médias, sinon il est posé comme un Oldthinker, dont l’espèce est condamnée au silence ou à la disparition.

Revenons aux différents aspects de la novlangue telle qu’elle a été imaginée par Orwell dans son 1984. Elle fourmille d’abréviations comme la langue soviétique ou, dans une moindre mesure, comme la langue de la NSDAP (cf. Klemperer). Les deux termes, “abréviés”, les plus connus sont l’Ingsoc (“English Socialism”) et le Minitrue (“The Ministry of Truth”, le “Ministère de la Vérité”). L’Ingsoc est l’idéologie officielle que l’on ne peut plus critiquer et le Minitrue est le ministère de la propagande qui fait triompher la vérité (mouvante selon les circonstances) de l’Ingsoc, même en cas de changement d’ennemi, de modification de la donne géopolitique (par exemple quand l’ennemi n’est plus l’Eurasia mais devient en un tournemain l’Eastasia). Il y a, dans la novlangue, produit de l’imagination romanesque d’Orwell, bien d’autres termes ou concepts révélateurs que l’on retient malheureusement un peu moins souvent malgré leur grande pertinence et leur réelle actualité. Ainsi le terme “bellyfeel”, à la fois verbe et substantif, qui désigne le sentiment d’adhésion viscéral que l’on peut ressentir à l’endroit de l’Ingsoc ou aujourd’hui à l’endroit de toutes les calembredaines hystériques de la “rectitude politique” ou des discours distillés par une gazette nauséabonde comme Le Soir à Bruxelles, spécialisé dans les discours haineux à l’endroit de la Flandre (sous tous ses aspects), de la Russie (sauf les oligarques), de l’Autriche, d’Israël, des militaires arabes, du Vatican, de l’archevêque de Malines, de la Syrie baathiste, de l’Arménie, du nazisme (imaginaire), des églises orthodoxes de Grèce, de Serbie, du monde slave ou de l’Orient, de la Chine ou de tout autre puissance ou fait social ou géopolitique qui déplait aux gauches de Washington, donc, en ultime instance, à la NSA. L’antonyme de bellyfeel est, selon les règles hypersimplificatrices de la novlangue, unbellyfeel, soit un sentiment de non-adhésion viscéral: de “feel”, “sentir” ou “ressentir”, et de “belly”, le “ventre” ou les “tripes”, les “viscères”. L’antonyme se forme par l’adjonction du préfixe “un”. Ce qui peut donner la phrase suivante: Oldthinkers unbellyfeel Ingsoc. Trois mots qui, pour Orwell, traduisent la longue phrase suivante: “Those whose ideas were formed before the Revolution cannot have a full emotional understanding of the principles of English socialism” (= “Ceux dont les idées se sont formées avant la Révolution ne peuvent comprendre émotionnellement les principes du socialisme anglais”). En bref: le bon citoyen d’Oceania (ou des pays formant la “Communauté Atlantique des Valeurs”) doit adhérer avec émotion, avec compassion (la “République compassionnelle”) aux idées que distillent les médias, sinon il est posé comme un Oldthinker, dont l’espèce est condamnée au silence ou à la disparition.

Aveuglement acquis et volontaire

Il y a ensuite le terme “blackwhite”, soit “penser en terme de tout blanc et tout noir”, de manière manichéenne et simplificatrice. Ce terme de la novlangue orwellienne recèle des connotations positives si la pensée manichéenne désignée correspond aux plans de l’Ingsoc; elle a des connotations négatives si elle contribue à rejeter les projets de l’Ingsoc. Le blackwhite est donc le contraire d’une pensée critique en adéquation avec le réel tel qu’il est, tel qu’il se présente extérieurement à nous. La présence ubiquitaire d’une pensée de type blackwhite entraîne un mécanisme, très actuel, de rejet du réel jugé incorrect (et qu’il faut corriger par des mesures coercitives ou par des appels pressants à une moralité “surréelle”). Ce rejet implique l’acceptation d’une pure fabrication irréelle laquelle doit être vue comme une “vérité” parce qu’elle est voulue telle par le pouvoir, par les médias, par le mainstream. Le blackwhite de la pensée officielle (et artificielle) fait émerger le doublethink, ou “double pensée”, soit une forme d’aveuglement acquis et volontaire vis-à-vis des contradictions contenues dans le système de pensée imposé. Le citoyen, dressé à penser de manière manichéenne (blackwhite) et émotionnelle (bellyfeel), ne perçoit plus, ne veut plus percevoir, à cause d’un processus insidieux de refoulement permanent, les contradictions du discours dominant (qui, aujourd’hui, par exemple, exalte un socialisme qui fait une politique néo-libérale ou un libéralisme soi-disant libre-penseur et dégagé de toute cangue religieuse mais qui accepte pour argent comptant toutes les dérives para-théologiennes du néo-conservatisme américain, etc.). Le réel est ainsi escamoté derrière un rideau de fumée médiatique, derrière un patchwork parfois contradictoire, tissé de brics et de brocs, présenté comme l’expression de la seule vérité vraie et acceptable, toute référence au réel concret étant assimilé à du oldthink ou à de la perversité émanant de Goldstein (ou d’un nazisme purement imaginaire ou d’un populisme mal défini mais voué d’office et a priori à devenir dangereux comme, par exemple, dans la Hongrie d’Orban).

Impostures intellectuelles

L’oldthink recèle la possibilité de tomber dans le crimethink, la pensée illicite et criminalisée, en contradiction avec les mots d’ordre du pouvoir. Le crimethink, dans le 1984 d’Orwell, est une pensée totalement incorrecte, en contradiction avec les directives du parti, des médias, de l’hegemon et de ses agences de presse chargées de faire l’opinion sur la planète entière. Toute voix critique de l’intervention de l’OTAN en Yougoslavie en 1999 commettait un crimethink, dûment réprimé à l’époque comme l’atteste l’inadmissible matraquage du Professeur Jean Bricmont à Bruxelles, qui protestait contre cette agression à proximité du Quartier Général de l’OTAN à Evere. Qui plus est, Bricmont était l’auteur d’un ouvrage intitulé Les impostures intellectuelles, lequel entendait démontrer que la fabrication d’un vocabulaire soi-disant philosophique et indirectement idéologique sur base de vocables tirés des disciplines scientifiques, dérivés des sciences physiques ou biologiques, relevait de l’imposture et donc de la manipulation médiatique et idéologique. Cette démonstration logique et réaliste avait déplu: Bricmont n’est presque plus nulle part en odeur de sainteté (ce qui l’honore). Il a aggravé son cas en 1999: il a donc ramassé une volée de coups de matraques. Le même scénario de diabolisation des adversaires de conflits inutiles et néo-impérialistes s’est répété lors de l’intervention contre l’Irak en 2003, où contrairement à l’intervention de 1990, l’opération n’avait pas reçu l’aval de l’ONU et d’alliés arabes de la coalition pro-américaine. Les machines propagandistes américaines ont alors fustigé l’Axe Paris-Berlin-Moscou, à leurs yeux, une alliance informelle de lâches, de passéistes et d’efféminés incapables de percevoir le danger, figés dans les complications de la diplomatie —celle-ci étant rejetée comme un vestige inutile et encombrant du passé— et tous fils de Vénus plutôt que du dieu Mars.

Novlangue et monde arabe contemporain

En Syrie, la machine s’est d’abord mise en branle pour charger Béchar El-Assad de tous les péchés du monde, selon le même mode de diabolisation administré en 1990 puis en 2003 contre Saddam Hussein. L’intervention de djihadistes incontrôlables en Syrie a forcé ces bellicistes en chambre à mettre un bémol à leurs excitations artificielles, les péchés véniels d’El-Assad apparaissant tout d’un coup bien pardonnables face aux atrocités commises par les salafistes et tafkiristes stipendiés par l’Arabie Saoudite et le Qatar, comme en Libye post-khadafiste d’ailleurs. Pour Khadafi, l’acharnement médiatique a conduit à une mort particulièrement hideuse. En Ukraine, où les techniques de diabolisation appliquées aux pays musulmans ne fonctionnent pas, on découvre que même Bernard-Henri Lévy trouve des vertus à des nationalistes ukrainiens qui, par antisoviétisme à une époque où le soviétisme n’existe même plus, se réclament du Troisième Reich hitlérien, parce que ce Troisième Reich a failli vaincre l’URSS de Staline, responsable de l’Holodomor, de la mort par famine de centaines de milliers de paysans des terres noires d’Ukraine! On constate dès lors que les syncrétismes raisonnables, participant d’une sorte de “rationalisme vitaliste” (Ortega y Gasset), sont pour l’Oceania occidentale actuelle des “pensées criminelles”, du crimethink, tandis que le fondamentalisme, sous toutes ses facettes, les plus bigotes comme les plus atroces, se voit parfaitement valorisé, du moins dans ses actions concrètes sur les terrains libyen et syrien, se muant du même coup en goodthink, parce que les wahhabites saoudiens incitent à la haine contre l’ennemi iranien, non seulement dans les pays du Proche et du Moyen Orient mais aussi dans les mosquées et centres “culturels” de nos banlieues ensauvagées mais les représentants de cet ensauvagement généralisé n’étant plus critiquables sous peine d’être taxé de crimethink, le système médiatique mainstream, —dont les stupides et hideux p’tits salauds haineux du Soir de Bruxelles— fait d’une pierre deux coups: sous prétexte de lutter contre le “racisme” (plus imaginaire que réel), il laisse la bride sur le coup aux prédicateurs de haine qui servent l’hegemon et ses alliés saoudiens.

Le système lutte contre le crimethink en imposant par la virulence propagandiste et par une terreur psychologique sournoise le réflexe du crimestop, soit un refoulement bien intériorisé, pareil aux refoulements sexuels de la société victorienne fustigés par David Herbert Lawrence, un refoulement qui empêche de recourir encore à l’oldthink ou à développer une pensée alternative qui serait automatiquement du crimethink. L’individu, comme le citoyen d’Oceania, combat, d’abord à l’intérieur de lui-même, dans ses propres cogitations, tout recours à un réel vrai car un tel recours serait du crimethink et le mettrait en marge de la société existante. Le citoyen formaté de toute Oceania, la fictive d’Orwell comme la “réellement existante” d’aujourd’hui, combat les expressions du crimethink, le dénonce chez ses concitoyens, est prêt à tuer toute personne qui émettrait des idées jugées criminelles par le pouvoir. Le crimestop, c’est-à-dire les réflexes inculqués qui permettent l’intériorisation viscérale des discours officiels, génère une abominable humanité de délateurs, de cloportes gris et visqueux, qu’Alexandre Zinoviev, dans Le communisme comme réalité, avait d’ailleurs très bien décrite, tout en précisant, surtout dans la suite de son oeuvre, que cette humanité déchue, ce “peuple-bête” (narod-zver), était certes formatée “communiste” dans sa patrie soviétique mais que l’Occidentisme était sur le point d’en générer une autre, sous le signe du libéralisme cette fois. Nous y sommes.

Duckspeak et oppositions inconsistantes