Author’s Note:

As we’ve come to appreciate with each passing year, World War Two was the most evil manifestation in human history. No other conflict even comes close in matching that war for its sweeping, sadistic and unspeakable crimes. Mass murder of surrendering soldiers, mass starvation of helpless civilians, mass rape of women and children, assembly-line style torture in the tens of thousands, uprooting and expulsion of millions to certain death, the deliberate, wanton destruction of ancient cultures–these atrocities and many more add to World War Two’s annual menu of beastly war crimes.

Also, with each passing year, it becomes clearer and clearer that virtually all the major crimes of the Second World War were committed by the Allied powers. Additionally, almost all these war crimes took place toward the end of the war. Why is this? Why were these terrible atrocities not only committed by the victorious Allied powers but why did almost all occur at the end of the war? Simply, late in the war the Allies knew very well they would win and they thus knew they had little to fear from retaliation or war crimes trials. The victors knew that they could unleash their sadism against a hated, helpless enemy with utter impunity, and they did.

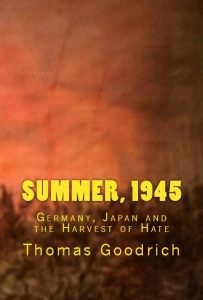

The following is a description of just one such major war crime as defined above. The account comes from my recent book, Summer, 1945—Germany, Japan and the Harvest of Hate. To this day, relatively little is actually known of this great atrocity. Of course, this is because war criminals not only commit such crimes expertly, but they cover up such crimes expertly, as well.

Just as Allied air armadas had mercilessly bombed, blasted and burned the cities and civilians of Germany during World War Two, so too was the US Air Force incinerating the women and children of Germany’s ally, Japan. As was the case with his peers in Europe, cigar-chewing, Jap-hating Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay had no compunction whatsoever about targeting non-combatants, including the very old and the very young.

Just as Allied air armadas had mercilessly bombed, blasted and burned the cities and civilians of Germany during World War Two, so too was the US Air Force incinerating the women and children of Germany’s ally, Japan. As was the case with his peers in Europe, cigar-chewing, Jap-hating Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay had no compunction whatsoever about targeting non-combatants, including the very old and the very young.

“We knew we were going to kill a lot of women and kids,” admitted the hard-nosed air commander without a blink. “Had to be done.”[1]

Originally, and although it would have been in direct violation of the Geneva Convention, Franklin Roosevelt had seriously considered gassing Japan. Much as British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had proposed doing to Germany earlier in the war, the American president had felt that flooding Japan with poison was not only a fine way to end the war he had personally instigated at Pearl Harbor, but it was a just punishment upon those who had continued the war into the spring of 1945. Unlike the Germans who had their own stock of deadly gas and who could have easily retaliated against the Allies had they been so attacked, Japan had virtually none of its own to reply in kind. To further the plan, Roosevelt ordered his staff to test the waters by discretely asking Americans, “Should we gas the Japs?” Since the plan was soon shelved, perhaps too many Americans remembered the horrors of trench warfare during WWI to want a repeat. The US Government then came up with the idea of unleashing “bat-bombs” on Japan. The brain-child of an American dentist, tiny incendiary time bombs were to be attached to thousands of bats which would then be dropped on Japan from aircraft. Soon after they sought shelter in Japanese homes, schools and hospitals the bat bombs would then explode thereby igniting fires all across the country. After spending months and millions of dollars on the project, the bat bombs, like poison gas, were also dropped. Ultimately, deadly incendiary bombs were developed and finally accepted as the most efficient way to slaughter Japanese civilians and destroy their nation.[2]

The Allies first created the firestorm phenomenon when the British in the summer of 1943 bombed Germany’s second largest city, Hamburg. After first blasting the beautiful city to splinters with normal high explosives, another wave of bombers soon appeared loaded with tens of thousands of firebombs. The ensuing night raid ignited numerous fires that soon joined to form one uncontrollable mass of flame. The inferno was so hot, in fact, that it generated its own hurricane-force winds that literally sucked oxygen from the air and suffocated thousands. Other victims were either flung into the hellish vortex like dried leaves or they became stuck in the melting asphalt and quickly burst into flames. LeMay hoped to use this same fiery force to scorch the cities of Japan. Tokyo would be the first test.

The Allies first created the firestorm phenomenon when the British in the summer of 1943 bombed Germany’s second largest city, Hamburg. After first blasting the beautiful city to splinters with normal high explosives, another wave of bombers soon appeared loaded with tens of thousands of firebombs. The ensuing night raid ignited numerous fires that soon joined to form one uncontrollable mass of flame. The inferno was so hot, in fact, that it generated its own hurricane-force winds that literally sucked oxygen from the air and suffocated thousands. Other victims were either flung into the hellish vortex like dried leaves or they became stuck in the melting asphalt and quickly burst into flames. LeMay hoped to use this same fiery force to scorch the cities of Japan. Tokyo would be the first test.

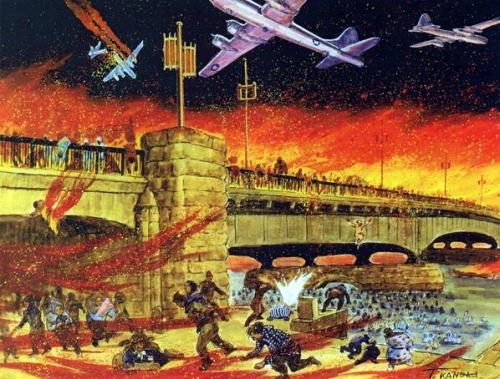

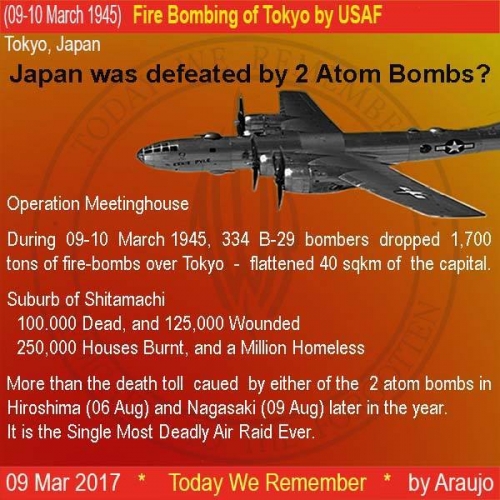

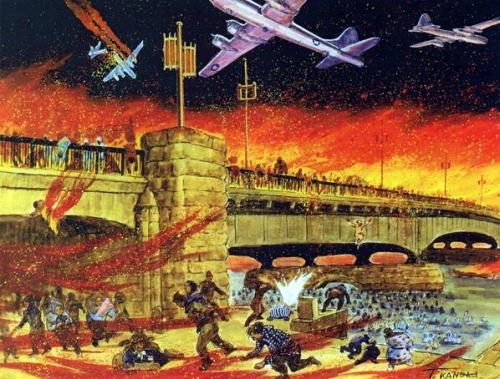

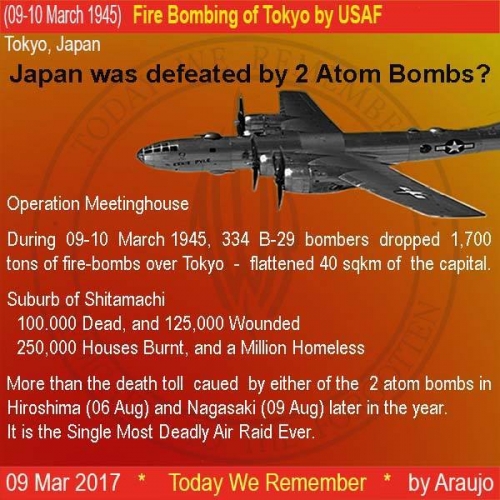

On the night of March 9-10, 1945, over three hundred B-29 bombers left their bases on the Mariana Islands. Once over Tokyo, advance scout planes dropped firebombs across the heart of the heavily populated city to form a large, fiery “X.” Other aircraft “painted” with fire the outer limits to be bombed, thereby encircling those living in the kill zone below.[3]

Soon, the remaining bombers appeared and easily followed the fires to their targets. When bomb bay doors opened tens of thousands of relatively small firebombs were released—some, made of white phosphorous, but most filled with napalm, a new gasoline-based, fuel-gel mixture. Within minutes after hitting the roofs and buildings below, a huge inferno was created. Since the raid occurred near midnight, most people were long in bed, thus ensuring a slow reaction. Also, the sheer number of firebombs—nearly half a million—and the great breadth of the targeted area—sixteen square miles—insured that Tokyo’s already archaic fire-fighting ability would be hopelessly inadequate to deal with such a blaze.

When the flames finally subsided the following morning, the relatively few survivors could quickly see that much of the Japanese capital had been burned from the face of the earth. In this raid on Tokyo alone, in one night, an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 people, mostly women and children, were, as Gen. LeMay announced proudly, “scorched and baked and boiled to death.”[4] Only the incineration of Dresden, Germany one month earlier, with an estimated death toll of 250,000-400,000, was greater.

“Congratulations,” wrote Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold to LeMay after hearing the news. “This mission shows your crews have got the guts for anything.”[5]

***

Following the resounding success with Tokyo, Gen. LeMay immediately turned his attention toward the similar immolation of every other city in Japan. As was the case with Germany, then later Tokyo, the aim of the US Air Force under Curtis LeMay was not so much to destroy Japanese military targets or factories so much as it was to transform all of Japan into a blackened waste, to kill as many men, women, and children as he could, and to terrorize those who survived to as great a degree as possible. In other words, under the command of LeMay the air attacks against Japan, just as with the air attacks against Germany, were “Terror Bombing,” pure and simple.[6]

To make this murderous plan as effective as possible, the US air commander and his aides studied the entire situation. Night raids were preferred, of course, since it would catch as many people in bed as possible. Also, dry, windy conditions were selected to accelerate the ensuing firestorm insuring few could escape. Additionally, since the Japanese air force had, for all intents and purposes, been destroyed in three years of war, there was little need for armament of the American bombers. Thus, the extra weight that ammunition, machine-guns and the men to fire them added to the aircraft was removed, making room for even more firebombs. But perhaps most important for Gen. LeMay was the decision to radically reduce the altitude for his bombing raids.

Prior to the Tokyo raid, standard bombing runs took place at elevations as high as 30,000 feet. At such great altitudes—nearly six miles up—it was insured that most enemy fighters and virtually all ground defenses would be useless. By 1945, however, with the virtual elimination of the Imperial Air Force and with normal anti-aircraft ground fire woefully inadequate or non-existent, enemy threats to American bomber waves was greatly reduced. Thus, the firebombing of Japan could be carried out by aircraft flying as low as 5,000 feet over the target. This last measure not only guaranteed that the US attacks would be carried out with greater surprise, but that the bombs would be dropped with deadlier accuracy. One final plus for the new tactics was the demoralizing terror caused by hundreds of huge B-29 bombers—“B-San,” the Japanese called them, “Mr. B”–suddenly roaring just overhead and each dropping tons of liquefied fire on those below. In a nation where most homes were made of paper and wood, the dread of an impending firebombing raid can well be imagined.

As one US intelligence officer sagely reported to a planning committee: “The panic side of the Japanese is amazing. Fire is one of the great things they are terrified at from childhood.”[7]

***

Following the destruction of Tokyo in which most of the city center was scorched black, and following the enthusiastic endorsement of American newspapers, including the curiously named Christian Century, Gen. LeMay swiftly sent his bomber fleets to attack virtually every other city in Japan. Osaka, Nagoya, Kobe, Yokohama, and over sixty more large targets were thus treated to the nightmare of firebombing. And simply because a city had been bombed once was not a guarantee that it would not be bombed again and again. Such was the terrible fate of Tokyo. Not content with the initial massacre, LeMay demanded that the Japanese capital be attacked until everyone and everything was utterly destroyed; “burned down,” demanded the US general, “wiped right off the map.”[8]

Unfortunately, no community was any better prepared to face the attacks than Tokyo had been. Fully expecting that if the US air craft ever attacked, it would be with typical high explosives, local and national authorities encouraged Japanese civilians earlier in the war to dig their own air raid shelters near or under their homes to withstand the blast and shrapnel of conventional bombs. Additionally, women were encouraged to wear heavy cloth hoods over their heads to cushion a bomb’s concussive force and prevent hearing loss. After Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, and other firebombing raids, however, it was clear that past defensive tactics were useless when facing the hellish firestorms.

Typically, first warning of a potential American air raid came with the city sirens. Like their German counterparts early in the war, the Japanese likewise sprang from their beds with every such alarm, either to join their various “bucket brigades” or to wet their mats and brooms and fill their water troughs just in case of fire. Most simply dashed to the holes in the ground they called “shelters.” But also like those in Germany, with numerous false alarms came predictable apathy on the part of the Japanese and an almost utter disregard of sirens. Often, when a few B-29s on reconnaissance flights were indeed spotted far above leaving their vapor trails, excited air raid wardens would run through the streets beating on buckets as a warning to laggards.[9] But soon, even these warnings were ignored.

“As the B-29’s came over us day in and day out, we never feared them,” admitted one woman weary of the alarms.[10]

That all changed dramatically following the firebombing of Tokyo. After that night, especially on dry, windy nights, in each Japanese city, in each Japanese heart, there was never any doubt that the war—a hellish, hideous war—had finally reached Japan.

***

First hint of an impending US air raid on a Japanese city came with a low, but ominous, rumble from afar. That menacing sound soon grew and grew to an approaching roar that caused the windows to rattle and the very air to vibrate. Finally, in one great burst, a terrifying, rolling thunder exploded just overhead. In no way, however, did the horrible sound prepare the people below for the horrible sight they then saw above. Usually at night, but sometimes even during the day, the sky was literally blotted out by the vision.

“I had heard that the planes were big,” said a stunned spectator, “but seen from so close, their size astounded me.”[11]

“Gigantic,” thought one spellbound viewer.[12]

“Enormous,” added another awe-struck witness. “It looked as if they were flying just over the telegraph poles in the street. . . . I was totally stupefied.”[13]

“They were so big,” remembered a young woman staring in disbelief. “It looked like you could reach out and grab them.”[14]

Then, amid the terrifying sights and sounds, the awe-struck people watched in utter amazement as the bomb bay doors of the frightening things sprang open as if on cue.

Falling not vertically, but diagonally, the objects which then began to shower down were at first thought to be pipes, or even sticks.[15] Within a few seconds, the true nature of the objects became known to all.

“They’re coming down,” the people screamed. “They’re coming down.”[16]

Almost immediately, as if a switch had been thrown, from every corner of the targeted city the night became light as day as each of the thousands of fire bombs ignited on impact. Quickly, the deadly liquid spread and in mere minutes the targeted city was totally engulfed.

“At that moment,” said 24-year-old Yoshiko Hashimoto, “we were caught in an inferno. The fire spread so quickly. The surroundings were seized with fire in a wink.”[17]

“The wind and flames seemed to feed into each other and both gained intensity,” described one teenager. “Pots and pans blew about on the ground and blankets flew through the air. People ran in all directions.”[18]

Since their homes and businesses made of wood and paper were mere “match boxes” ready to ignite, most people recognized instantly the futility of trying to fight the fire and they quickly fled into the streets.

“Roofs collapsed under the bombs’ impact,” said an eyewitness, “and within minutes the frail houses . . . were aflame, lighted from the inside like paper lanterns.”[19]

It was at that terrifying moment, when their entire world seemed on the verge of being consumed by smoke and flame, that single mothers, their husbands off at war or dead, were forced to make life and death decisions. To save small children, some were compelled to leave old, feeble relatives behind; others had to abandon beloved pets or needed animals. One mother, to save her two tiny tots, made the heart-breaking decision to leave her handicapped child to certain death.[20]

“The three of us dashed out into the panic and pandemonium of the streets,” recalled Masayoshi Nakagawa, a father of two little children and a man whose wife was in a local hospital expecting their third child. “People were carrying whatever they had managed to salvage: quilts, pillows, frying pans. Some of them had carts; others lugged bicycles on their backs.”[21]

Once in the streets, the refugees were greeted by a “red blizzard” of sparks. Unlike typical sparks, however, those created from incendiary bombs were large “chunks” of oily, wind-driven flame that would instantly ignite the clothes of those fleeing. 22 Another hazard was the “hail” of bombs themselves. So many of the relatively small bombs were dropped on any given city that many victims were actually struck by them. Most, of course, were instantly wrapped in a ball of fire and died in terrible agony. One woman watched in horror as her husband ran from their family business shouting “Air Raid! Air Raid!” and was immediately struck in the head by a firebomb.

“He was instantly wrapped in a sheet of bluish flame. . . ,” recounted the horrified wife. “I could not put out the fire. All my desperate efforts were of no avail. . . . His hair was still sizzling and giving off a blue light. His skin peeled away in sheets, exposing his flesh. I could not even wipe his body.”[23]

Just as with the man above, those victims who actually came in contact with the napalm found that such fire could not be extinguished and would burn and sizzle all the way to the bone.[24]

Desperately, those trapped within the encircled target zone searched for avenues of escape. Unfortunately, at every turn the victims met only more fleeing refugees and more smoke and flame. Those who had remained at their own air raid shelters near their homes were already dead, the holes acting like earthen bake ovens in the heat. Others met similar fates when they wrongly assumed that the few brick and concrete buildings in the city would protect them. They did the opposite. When the racing flames reached these buildings those inside were quickly incinerated. Iron rafters overhead sent down streams of molten metal on any still alive.[25]

Nor did parks prove to be havens. With temperatures reaching 1,800 degrees, the trees quickly dried, then burst into flames. Additionally, those who sought open spaces, or areas burned bare from previous raids, were easy targets for US fighter pilots who routinely machine-gunned fleeing refugees, just as they had done in Germany. Other American aircraft watched the streets for any Japanese fire companies bold enough to fight the fires, then attacked with high explosives.[26]

By the hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands, the people fled through the streets as the furnace became fiercer and fiercer.

“Hell could get no hotter,” thought French reporter, Robert Guillain, as he watched the crowds struggle against the murderous heat and the “hail” of huge, flaming sparks.

People soaked themselves in the water barrels that stood in front of each house before setting off again. A litter of obstacles blocked their way; telegraph poles and the overhead trolley wires that formed a dense net . . . [of] tangles across streets. . . . The fiery air was blown down toward the ground and it was often the refugees’ feet that began burning first: the men’s puttees and the women’s trousers caught fire and ignited the rest of their clothing.[27]

As noted, in the furious heat and wind it was often a victim’s shoes or boots which erupted in flames first, followed quickly by the pants, shirts, and air raid hoods that many women still wore.[28] As the horrified people stripped off one layer of burning clothing after another, many rolling on the ground to smother the fires, some simply burst into flames entirely—hair, head, skin, all. One witness watched as a child ran by screaming shrilly, “It’s hot! It hurts! Help me!” Before anyone could reach him, the child burst into flames “as if he’d been drenched in gasoline.”[29] In the midst of her own desperate bid to escape, one teenage girl saw a mother and father bravely place their own bodies between the killing heat and their small children. At last, when the father simply burst into flames he nevertheless struggled to remain upright as a shield for his children. Finally, the man teetered and fell.

“I heard him shouting to his wife,” recalled the witness, “‘Forgive me, dear! Forgive me!’”[30]

Likewise, thousands of victims in other Japanese cities could not bear the ferocious heat and simple exploded in flames from spontaneous combustion.[31]

The streets, remembered police cameraman, Ishikawa Koyo, were “rivers of fire . . . flaming pieces of furniture exploding in the heat, while the people themselves blazed like ‘matchsticks’. . . . Under the wind and the gigantic breath of the fire, immense incandescent vortices rose in a number of places, swirling, flattening, sucking whole blocks of houses into their maelstrom of fire.”[32]

Continues French visitor, Robert Guillain:

Wherever there was a canal, people hurled themselves into the water; in shallow places, people waited, half sunk in noxious muck, mouths just above the surface of the water. . . . In other places, the water got so hot that the luckless bathers were simply boiled alive. . . . [P]eople crowded onto the bridges, but the spans were made of steel that gradually heated; human clusters clinging to the white-hot railings finally let go, fell into the water and were carried off on the current. Thousands jammed the parks and gardens that lined both banks of the [river]. As panic brought ever fresh waves of people pressing into the narrow strips of land, those in front were pushed irresistibly toward the river; whole walls of screaming humanity toppled over and disappeared in the deep water.[33]

With two little children clutched under his arms, Masayoshi Nakagawa raced for the canals and rivers as everyone else, hoping to find a haven from the deadly heat.

Suddenly I heard a shout: “Your son’s clothes are on fire!” At the same instant, I saw flames licking the cotton bloomers my daughter was wearing. I put my son down and reached out to try to smother the flames on his back when a tremendous gust of wind literally tore me from him and threw me to the ground. Struggling to stand, I saw that I was now closer to my daughter than to the boy. I decided to put out the fire on her clothes first. The flames were climbing her legs. As I frantically extinguished the flames, I heard the agonized screams of my son a short distance away. As soon as my daughter was safe, I rushed to the boy. He had stopped crying. I bent over him. He was already dead.[34]

Grabbing his daughter and his son’s body, Masayoshi joined the fleeing crowds once again, trying to escape the “ever-pursuing inferno.”

“Once in the open space . . ,” continues the grieving father, “I stood, my daughter by my side, my dead son in my arms, waiting for the fire to subside.”[35]

Surprisingly, during days and nights such as these filled with horrors scripted in hell—children bursting into flames, glass windows melting, molten metal pouring down on people—often it was the small and seemingly trivial sights and sounds that sometimes stayed with survivors forever. One little girl, after watching a panicked mother run past with her baby totally ablaze on her back, after seeing children her own age rolling on the ground like “human torches,” after hearing the sounds of a man and a horse he was leading both burning to death, still, again and again, the little girl’s mind wandered back to the safety of her cherished doll collection, then on display at a local girl’s festival.[36]

“To my surprise,” recalled another survivor, “birds in mid-flight—sparrows and crows—were not sure where to go in such a situation. I was surprised to see that the sparrows and the crows would cling to the electric wire and stay there in a row. . . . You’d think they’d go into the bushes or something.”[37]

Amid all the horror, another woman never forgot the strange sight of a refugee standing in a large tank of water holding only a live chicken. Another young female, admittedly “numb to it all,” found as she passed a mound of dead bodies that her eyes became transfixed on a pair of nose holes that seemed to be peering up at her.[38]

Finally, on numerous occasions, because of the American “encirclement” of a targeted city, thousands of refugees fleeing from one direction collided head-on with thousands of refugees fleeing from another direction. In this case, the panicked multitude, now incapable of moving forward because of an equally panicked multitude in front, and incapable of moving backward because of the pursuing firestorm, simply became wedged so tightly that no one could move. Horrific as the ordeal had been thus far, it was nothing compared to this final act of the hellish horror. Since most refugees were fleeing instinctively toward water, many crowds became wedged on bridges. Thousands of victims were thus overtaken by the fury and were burned to a crisp by the fiery winds that to some resembled “flame throwers.” Thousands more, horribly burned, managed to leap or fall to their deaths into the rivers and canals below. Eventually, metal bridges became so hot that human grease from the victims above poured down on the bodies of victims below.[39]

And as for those far above, to those who had dropped millions of firebombs on the cities and towns of Japan, the horror show they had created below was now vivid in all its lurid detail. At such low altitudes, with night now day, those above had a front row seat to all the hellish drama below. Fleeing humans racing for life down streets now more “streams of fire” than streets, screaming horses engulfed in flames galloping insanely in all directions, bridges packed with doomed mothers and children, rivers and canals jammed with the dead and the dead to be. And for those US fighter pilots whose job was to massacre refugees who reached the open spaces, their view was even closer. In the red and white glare of the fires, these Americans could actually see the eyes of those they were machine-gunning to death, the women with babies, the children exploding from bullets, the old, the slow, the animals. The violent updrafts from the heat below was a much greater threat to US bombers than the almost non-existent Japanese anti-air defenses. Wafted on the heat thousands of feet up was the scattered debris from below—bits and pieces of homes, offices and schools; tatters of burnt clothing; feathers and fur from dead pets; and, of course, the pervasive smell of broiled human flesh.

“Suddenly, way off at 2 o’clock,” noted an awe-struck American pilot arriving on the scene, “I saw a glow on the horizon like the sun rising or maybe the moon. The whole city . . . was [soon] below us stretching from wingtip to wingtip, ablaze in one enormous fire with yet more fountains of flame pouring down from the B-29s. The black smoke billowed up thousands of feet . . . bringing with it the horrible smell of burning flesh.”[40]

Once the attacking force had loosed its bombs and banked for home, the red glow of the holocaust they had created could be seen for as far as 150 miles.[41]

***

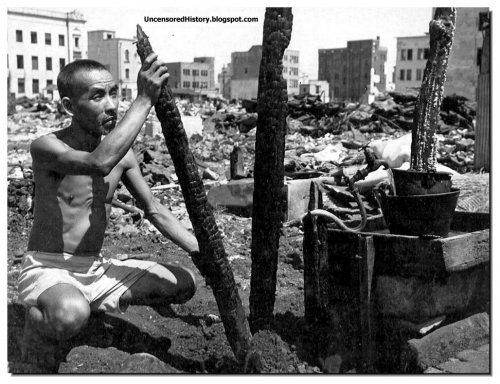

With the departure of enemy aircraft and the eventual subsiding of the fires, workers and volunteers from throughout the stricken region finally felt safe enough to venture in and begin rescue operations. Given the frail, flammable nature of most Japanese cities, virtually every structure in a targeted area—homes, shops, businesses—was utterly leveled. As a consequence, because there was seldom need to clear stone, brick, metal, and other rubble from a bombed area, as was the case in Germany, the search for bodies in Japan was made easier, if not easy.

By the thousands, by the tens of thousands, the charred victims lay everywhere. Many died alone, overcome in their flight by heat and exhaustion. It was common to find a single blackened mother laying upon a single blackened child that she was trying so desperately to protect. But many more victims seemed to have died en masse. Time and again rescue workers encountered “piles” and “mounds” of bodies, as if all suddenly found their way cut off or as if the people unsuspectingly entered areas vastly hotter than elsewhere and succumbed as one quickly. “I saw melted burnt bodies piled up on top of each other as high as a house,” remembered one ten-year-old.[42] In such areas, below the piles of blackened bodies, large puddles of dark human rendering was noticed.

“We saw a fire truck buried under a mountain of blackened bones,” wrote another witness. “It looked like some kind of terrifying artwork. One couldn’t help wondering just how the pile of bodies had been able to reach such a height.”[43]

“What I witnessed,” said one badly burned woman leading her blind parents, “was the heaps of bodies lying on the ground endlessly. The corpses were all scorched black. They were just like charcoal. I couldn’t believe my eyes. . . . We walked stepping over the bodies being careful not to tread on them.” Unfortunately, the woman’s parents tripped and stumbled over the corpses again and again.[44]

Many victims, it was noticed, had heads double and triple their normal size.[45]

Others gazed in wonder at the array of color the bodies displayed; many, of course, were scorched black, but some were brown, red or pink. “I particularly remember a child,” said one little girl, “whose upper half of the body was coal-black but its legs were pure white.”[46]

“I . . . saw a boy,” another child recalled. “He was stark naked, and had . . . burns all over the body. His body was spotted with black, purple, and dark red burns. Like a rabbit, the boy was hopping among the corpses . . . and looked into the dead persons’ faces. . . . He was probably searching for his family members.”[47]

Elsewhere in the stricken cities, before disease could spread, rescue workers began the grim task of disposing of the unclaimed bodies as quickly as possible. By the hundreds, then by the thousands, many scorched and shriveled victims were buried in common trenches with others.[48] Some survivors took it upon themselves to collect the remains of friends and neighbors. When the air raid began in her city, one woman was talking with a neighbor when an explosive bomb blew him to bits. Later, feeling compelled to do so, the lady returned and began the horrible recovery of the body parts, including the head. “I was suddenly struck with the terrifying thought,” the woman, who was on the verge of fainting, recalled, “that perhaps someday soon someone would have to do the same thing to me.”[49] Workers elsewhere simply did not have the time or patience for such concern and care and simply tossed body parts into rivers.[50]

Initially, when rescuers entered the few brick and concrete buildings in the stricken cities, they were mystified. Expecting heaps of bodies, they found only layer upon layer of ash and dust. Far from being points of refuge as the unsuspecting victims imagined, the buildings had served rather as super-heated ovens, not only killing everyone when the flames neared but baking each body so thoroughly that only a faint dry powder remained. Even with only a slight breeze, other such baked victims simply blew away “like sand.”[51]

Following such horrific attacks, many stunned survivors simply stumbled among the ruins aimlessly as if in a trance, dazed, disoriented, seemingly looking for something, but actually looking for nothing. With a new and unimaginable terror springing up at every turn during every second of the night before, time then seemed to have telescoped, then stopped. “It took seemingly forever to cover a distance that ordinarily would take two or three minutes,” noted one surprised survivor. And for those victims who gathered their wits and somehow managed to stagger from targeted cities with only minor injuries, such treks generally became terrifying odysseys unto themselves.

After escaping the inferno at Chiba the night before, and with a two-year-old sister in her arms and an eight-year-old sister on her back suffering from a terrible head wound, little Kazuko Saegusa finally reached the countryside the following morning in a drizzling rain. Finding a hand cart, the exhausted ten-year-old placed the two children inside then set off in hopes of finding a doctor or a hospital to help her injured sister. While pulling the cart between muddy rice paddies, the terrified little girl was repeatedly strafed by American fighter planes. Nevertheless, Kazuko refused to run for cover and leave her sisters behind. Eventually, and almost miraculously, the child reached a hospital. Unfortunately, there was no happy ending.

“The corridors of the hospital were packed with people burned past recognition,” remembered Kazuko. “There were many young people whose arms or legs had been amputated. . . . The screaming was beyond description. . . . Maggots wriggled from the bandages.”[52]

Conditions at the hospital were so bad that Kazuko and her sisters, along with many others, were moved to an open area near a church. But again, American aircraft soon made their appearance and strafed the victims, forcing the little girl to grab her sisters and finally seek safety in a stand of trees.[53]

Although the dead outnumbered the living following such nightmares, for many shattered survivors, like little Kazuko, the trials continued.

After losing his son the night before, with the dawn, Masayoshi Nakagawa and his tiny surviving child now set off to find his pregnant wife somewhere in the destroyed city.

My daughter and I, hand in hand, alone now, started off. Weary and emotionally drained, we had to force ourselves to struggle on through mounds of debris and corpses; among the foul, pungent odors, and the groans of the injured and dying. A man holding a frying pan gazed blankly at ashes that had been a house. Another squatted, dazed and helpless, in the middle of the street. Mothers frantically called for their children; small children screamed for their parents. I neither could nor wanted to do anything for the suffering people. My own suffering was too great. Probably all the others felt the same way.

Near [a] railway station, mounds of bodies clogged the track underpass. The walls were spattered with blood. A charred mother sat embracing her charred infant. The dead, burned beyond recognition, looked like grotesque bald dress-maker’s dummies. Those who were still alive moaned against the heat and called for water.[54]

Unbeknownst to Masayoshi, his wife, after a “difficult delivery,” had given birth to a healthy baby girl during the height of the firestorm the night before. Because of the approaching flames, everyone in the hospital had urged the mother to leave her newborn and flee while she could. Refusing to do so, the weakened woman wrapped her infant then fled into the inferno. Pale and bleeding, facing the flames and deadly sparks, the mother kept her baby covered tightly and sprinkled her with water throughout the hellish night. The following day, the utterly exhausted woman collapsed in the street and could go no further. Fortunately, a kind man, forgetting his own misfortune for the moment, carried the mother and child to a nearby hospital. After only the briefest of rests, the woman and her baby again set off in search of Masayoshi and the children.

Finally, after days and days of fruitless searching for a wife that he assumed was, like his son, dead, the husband learned from a mutual friend that the woman and their new child were yet alive and uninjured. For this husband and father, the news was the first reason to smile in what seemed a lifetime.

“I was overjoyed,” Masayoshi said simply, yet with a heart filled with emotion.[55]

***

Following the deadly firebombing of Japanese cities, the death toll in each continued to climb for days, even weeks as those terribly burned and maimed succumbed to injuries. With a sudden shortage of doctors, nurses and medicine, most victims were cared for by family and friends who coped as best they could. Some were successful, some were not.

When she first realized that her daughter’s badly burned legs had become infested with maggots, one horrified mother promptly fainted from shock. After she came to, the determined woman found a pair of chop sticks and immediately went to work picking out the maggots, one at a time.[56]

Others died in different ways. Two days after the raid upon their hometown in which her husband was killed, Fumie Masaki’s little son and other boys discovered an unexploded bomb while on a playground. When a fire warden arrived to dispose of it, the bomb exploded. Eight children were killed, including Fumie’s son.[57]

For a nation surrounded and blockaded, starvation was already a very real concern for Japan. In the bombed and burned cities with their rail, road and river traffic destroyed, it was an even greater threat. Adults soon noticed that children now suddenly grew gaunt and pale and looked “somehow older” than before. Many thin babies had escaped the firebombings only to starve in the days and weeks following. Dogs and cats were no longer seen in Japan. Even the Japanese government urged the people to supplement their diets with “rats, mice, snakes, saw dust, peanut shells, grasshoppers, worms, silkworms, and cocoons.”[58]

Added to starvation was chronic exhaustion from lack of sleep and rest. Those who somehow managed to remain in bombed cities did so with the constant dread of the nightmare’s repeat. Those who moved to undisturbed cities did so fully expecting the fire to fall at any hour.[59]

“I wish I could go to America for just one good night’s sleep,” groaned one exhausted postman.[60]

Exacerbating the daily stress and strain of Japanese civilians was the American “targets of opportunity” program. Just as they had done in Germany, US commanders ordered their fighter pilots aloft with orders to shoot anything in Japan that moved. Unfortunately, many young men obeyed their orders “to the letter.” Ferry boats, passenger trains, automobiles, farmers in fields, animals grazing, women on bicycles, children in school yards, orphanages, hospitals . . . all were deemed legitimate targets of opportunity and all were strafed again and again with machine-gun and cannon fire.[61]

“And not a single Japanese aircraft offered them resistance,” raged a man after one particular strafing incident. The angry comment could just as easily have been spoken after all American attacks, firebombings included. Certainly, the most demoralizing aspect of the war for Japanese civilians was the absolute American control of the air above Japan. During the nonstop B-29 attacks against the cities and towns, seldom was a Japanese aircraft seen to offer resistance.

“When . . . there was no opposition by our planes . . ,” offered one dejected observer, “I felt as if we were fighting machinery with bamboo.”[62]

Even members of the military had to agree. “Our fighters were but so many eggs thrown at the stone wall of the invincible enemy formations,” admitted a Japanese naval officer.[63]

And as for anti-aircraft guns. . . .

“Here and there, the red puffs of anti-aircraft bursts sent dotted red lines across the sky,” recounted one viewer, “but the defenses were ineffectual and the big B-29s, flying in loose formation, seemed to work unhampered.”[64]

Indeed, those guns that did fire at B-29s seemed more dangerous to those on the ground than to those in the air. Early in the bombing campaign, after a single B-29 on a reconnaissance mission flew away totally unscathed following a noisy anti-aircraft barrage, shrapnel falling to earth killed six people in Tokyo.[65]

“Our captain was a great gunnery enthusiast,” sneered a Japanese sailor. “He was always telling us that we could shoot Americans out of the sky. After innumerable raids in which our guns did not even scratch their wings, he was left looking pretty silly. When air attacks came in, there was nothing much we would do but pray.”[66]

In July, 1945, Curtis LeMay ordered US planes to shower with leaflets the few remaining Japanese cities that had been spared firebombing with an “Appeal to the People.”

As you know, America which stands for humanity, does not wish to injure the innocent people, so you had better evacuate these cities.

Within days of the fluttering leaflets, half of the warned cities were firebombed into smoking ruins.[67]

With the destruction of virtually every large Japanese city, LeMay kept his men busy by sending them to raid even the smaller cities and towns. After his own remote community was attacked, one resident knew the end was in sight. “When we were bombed,” admitted the man, “we all thought—if we are bombed, even in a small mountain place, the war must certainly be lost.”[68]

Others felt similarly, including a high-ranking civil servant:

It was the raids on the medium and smaller cities which had the worst effect and really brought home to the people the experience of bombing and a demoralization of faith in the outcome of the war…. It was bad enough in so large a city as Tokyo, but much worse in the smaller cities, where most of the city would be wiped out. Through May and June the spirit of the people was crushed. [When B-29s dropped propaganda pamphlets] the morale of the people sank terrifically, reaching a low point in July, at which time there was no longer hope of victory or a draw but merely a desire for ending the war.[69]

***

According to American sources, the first firebombing raid on Tokyo, the raid that was the most devastating of all raids and the raid that provided the blue print for all future firebombing raids on Japan, was a complete and utter success. Not only was the heart of the great city totally scorched from the face of the earth, but over 100,000 people were also killed. Furthermore, American sources also estimate that from that first raid on Tokyo to the end of the war approximately sixty Japanese cities were laid waste and that roughly 300,000-400,000 civilians were killed in Gen. Curtis LeMay’s firebombing raids.

The firebombing of Japan by the United States Air Force in the spring and summer of 1945 was simply one of the greatest war crimes in world history. Arguments that the operation helped speed Japanese defeat and surrender are little more than self-serving nonsense. For all intents and purposes Japan was already defeated, as the January, 1945 attempts to surrender already illustrate. In that month, peace offers to the Americans were being tendered. The mere fact that the vast majority of the estimated 300,000-400,000 deaths from firebombing were women, children, and the elderly should alone put the utter lie to the claim that such a crime added anything material to ultimate American victory. As was the case with the saturation bombing of Germany and the consequent firestorms that slaughtered countless women and children there, far from pushing a nation to surrender, the murder of helpless innocents in fact enraged and strengthened the resolve of the nation’s soldiers, sailors, and airmen to fight, if necessary, to the death.

“Seeing my home town ravaged in this way inspired me with patriotic zeal,” revealed one young Japanese speaking for millions. “I volunteered for military service soon after the . . . raid because I felt that in this way I could get even with the Americans and British, who . . . were nothing but devils and beasts.”[70]

And as for the American “estimates” of Japanese firebombing deaths. . . .

When the first B-29 raid took place in March, 1945, the targeted killing zone of Tokyo contained a population of roughly 1.5 million people. Given the fact that most living in this area were, as always, the most vulnerable—women, children, the old, the slow—and given the tactics used—saturation firebombing, dry conditions, gale force winds to accelerate the flames, encirclement, fighter aircraft machine-gunning those in parks or along rivers—and given the fact that the firestorm’s devastation was utter and succeeded even beyond Curtis LeMay’s most sadistic dreams, to suggest that out of a million and a half potential victims in the death zone only a mere 100,000 died while well over a million women and children somehow managed to escape the racing inferno is a deliberate attempt to reduce the number of slain and thereby, with an eye to future criticism and condemnation, a deliberate attempt to reduce the crime itself.

Additionally, although the greatest loss of Japanese life occurred during the Tokyo raids, hundreds of thousands of victims also perished in other large cities. To suggest, as modern American sources do, that even including the death toll in Tokyo the number killed in similar raids nationwide combined only came to 300,000-400,000 victims is, again, a deliberate attempt to reduce the number of victims in hope of reducing the extent of the crime. Indeed, any modern attempt that calculates the number of firebombing deaths in Japan at less than one million should not be taken seriously.

As one expert wrote:

The mechanisms of death were so multiple and simultaneous—oxygen deficiency and carbon monoxide poisoning, radiant heat and direct flames, debris and the trampling feet of stampeding crowds—that causes of death were later hard to ascertain.[71]

Accurate for the most part, one element left out of that death assessment is also that which seems the least likely—drowning. In one of the cruelest of ironies, more people may have actually died from drowning during the firestorm raids than from the flames themselves. In their frantic attempts to escape the torturous heat, even those who could not swim—the very old, the very young—sprang into any body of water available—reservoirs, rivers, canals, ponds, lakes, even large, deep water tanks—and took their chances there, drowning below being clearly preferable to burning above. Of the tens of thousands of drowning victims recovered, no doubt tens of thousands more were swept down rivers and streams and out to sea, never to be seen again.

Whether woman and children drowned or burned to death, it was all one and the same to Curtis LeMay.

“I’ll tell you what war is about,” explained the merciless US general, “you’ve got to kill people, and when you’ve killed enough they stop fighting.”[72]

Unfortunately, while a significant percentage of Americans felt just as LeMay, virtually all US leaders and opinion molders felt that way.

“Keep ‘Em Frying,” laughed the Atlanta (Ga) Constitution.[73]

And “keep ‘em frying” Curtis LeMay would.

***

Fortunately for the future of mankind, in the very midst of a merciless war waged by evil men and prolonged by equally evil politicians, many ordinary individuals nevertheless always remain true to their better selves.

In spite of the US firebombing massacre and the inhuman “targets of opportunity” slaughter taking place, when an injured American fighter pilot was forced to bail out over Japan, instead of being machine-gunned as he floated down or instead of being beaten to death by angry villagers when he touched ground, he was instead taken to a hospital that his serious wounds might be treated.

During his short stay, four young Japanese pilots, curious more than anything, visited the injured American. Whatever transpired during those brief moments of broken English, of eyes wide with wonder for an enemy pilot, and perhaps even of soft smiles of sympathy for a dying brother-at-arms—a bond was quickly formed.

Finally, as the Japanese airmen said their polite goodbyes and quietly turned to leave forever, the fast failing US pilot begged one of the young men to please wait for a moment. Working something free from his hand, the heavily bandaged American asked the visitor, only moments before his mortal enemy, for a first, and final, favor: When the madness was finally over, when reason had once more returned to the world, would the young man please carry the wedding ring to the United States? And once there would he please tell a young American widow how her young American pilot had fallen to earth one day and how he had died?[74]

Notes

1 Michael Bess, Choices Under Fire—Moral Dimensions of World War II (New York, Knopf, 2006), 105.

2 Goodrich, Hellstorm, 46; Edmund Russell, War and Nature—Fighting Human and Insects With Chemicals From World War I to Silent Spring, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001) 106-07,138; “FDR warns Japanese against using poison gas,” History, http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fdr-warns-japa... [2] ; “Old, Weird Tech: The Bat Bombs of World War II,” The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2011/04/ol... [3]

3 “The Tokyo Fire Raids, 1945—The Japanese View,” Eye Witness to History.com, http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/tokyo.htm

4 “Tokyo WWII firebombing, the single most deadly bombing raid in history, remembered 70 years on,” ABC News, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-03-09/tokyo-wwii-firebomb... [4]

5 Walter L. Hixson, ed., The American Experience in World War II (NY: Routledge, 2003), 184.

6 Russell, War and Nature, 138.

7 “FIRE BOMBING ATTACKS ON TOKYO AND JAPAN IN WORLD WAR II, Facts and Details, http://factsanddetails.com/asian/ca67/sub429/item2519.html

8 “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, http://apjjf.org/-Mark-Selden/2414/article.html [5]; Max Hastings, Retribution, 298. X-73

9 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Yoshiko Hashimoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/?feed=rss2

10 Ibid.

11 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Aiko Matani account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

12 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Teruo Kanoh interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

13 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Yoshiko Hashimoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

14 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Michiko Kiyo-Oka interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

15 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Haruyo Nihei interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

16 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Saotome Katsumoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

17 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Yoshiko Hashimoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

18 “The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived,” The Asia-Pacific Journal—Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/2011/9/3/Bret-Fisk/3471/article.html [8]

19 “The Tokyo Fire Raids, 1945—The Japanese View,” EyeWitness to History.com, http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/tokyo.htm

20 “The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, http://www.japanfocus.org/-Bret-Fisk/3471#sthash.xzZvfCe2... [9]

21 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Masayoshi Nakagawa account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

22 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Saotome Katsumoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived,” The Asia-Pacific Journal—Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/2011/9/3/Bret-Fisk/3471/article.html

23 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Fumie Masaki account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

24 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Saotome Katsumoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

25 “The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived,” The Asia-Pacific Journal—Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/2011/9/3/Bret-Fisk/3471/article.html [8]

26 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Teruo Kanoh interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Saotome Katsumoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

27 “The Tokyo Fire Raids, 1945—The Japanese View,” Eye Witness to History, http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/tokyo.htm [10]

28 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Aiko Matani interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Teruo Kanoh interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

29 “The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived,” The Asia-Pacific Journal—Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/2011/9/3/Bret-Fisk/3471/article.html

30 “The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived,” The Asia-Pacific Journal—Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/2011/9/3/Bret-Fisk/3471/article.html [8]

31 “The Tokyo Fire Raids, 1945—The Japanese View,” Eye Witness to History, http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/tokyo.htm [10]

32 “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/-Mark-Selden/2414/article.html [5]

33 “The Tokyo Fire Raids, 1945—The Japanese View,” Eye Witness to History, http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/tokyo.htm [10]

34 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Masayoshi Nakagawa account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

35 Ibid.

36 “Hitting Home—The Air Offensive Against Japan,” Air Force History and Museums Program, 1999, https://archive.org/details/HittingHome-nsia; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Haruyo Nihei interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

37 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Nobuyoshi Tan interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

38 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Tomie Akazawa account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6] ; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Michiko Kiyo-Oka interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

39 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Teruo Kanoh interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Yoshiko Hashimoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Michiko Kiyo-Oka interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ;”Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Haruyo Nihei interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “The Tokyo Fire Raids, 1945–The Japanese View,” Eye Witness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com

40 Hastings, Retribution, 297.

41 “Hitting Home—The Air Offensive Against Japan,” Air Force History and Museums Program, 1999, https://archive.org/details/HittingHome-nsia [11]

42 “Tokyo WWII firebombing, the single most deadly bombing raid in history, remembered 70 years on,” ABC News, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-03-09/tokyo-wwii-firebomb... [4]

43 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Masaharu Ohtake interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

44 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Haruyo Nihei interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

45 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Yoshiko Hashimoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

46 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Haruyo Nihei interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

47 Ibid.

48 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Teruo Kanoh interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

49 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Tai Kitamura account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

50 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Teruo Kanoh interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

51 “The Tokyo Fire Raids, 1945—The Japanese View,” Eye Witness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com [12]

52 “Women Against War—Personal Accounts of Forty Japanese Women” (Women’s Division of Soka Gakkai, Kodansha International, Ltd.,1986), 119-120

53 Ibid.

54 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Masayoshi Nakagawa account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

55 Ibid.

56 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Haruyo Nihei interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

57 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Fumie Masaki account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

58 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Yoshiko Hashimoto interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ;“The Tokyo Air Raids in the Words of Those Who Survived,” The Asia-Pacific Journal—Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/2011/9/3/Bret-Fisk/3471/article.html [8] ; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Nobuyoshi Tan interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Shigemasa Toda interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat—Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999), 91.

59 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Rie Kuniyasu account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

60 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Michiko Kiyo-Oka interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7]

61 “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Nobuyoshi Tan interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “Japan Air Raids.org—A Bilingual Historical Archive,” Shigemasa Toda interview, http://www.japanairraids.org/ [7] ; “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Eiji Okugawa account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]; “Air Raids on Japan,” Wkipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_raids_on_Japan [13]; “Women Against War—Personal Accounts of Forty Japanese Women,” Kazuko Saegusa account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40249017/Women-Against-War

62 “The Effects of Strategic Bombing on Japanese Morale,” The United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Morale Division, 1947), vi.

63 Hastings, Retribution, 133.

64 “The Tokyo Fire Raids, 1945–The Japanese View,” Eye Witness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com

65 Isaac Shapiro, Edokko—Growing Up A Foreigner in Wartime Japan (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 132.

66 Hastings, 138.

67 “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/-Mark-Selden/2414/article.html

68 “The Effects of Strategic Bombing on Japanese Morale,” United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Morale Division [14], https://archive.org/details/effectsofstrateg00unit55.

69 “Preparations for Invasion of Japan–14 Jul 1945–9 Aug 1945,” World War II Data Base, http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=54 [15]

70 “Cries For Peace—Experiences of Japanese Victims of World War II,” Tomio Yoshida account, https://www.scribd.com/document/40248814/Cries-for-Peace [6]

71 “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, http://apjjf.org/-Mark-Selden/2414/article.html

72 “Curtis LeMay,” Wikiquote, https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Curtis_LeMay [16]

73 “Firebombing of Japanese Cities during World War II,” Book Mice, http://www.bookmice.net/darkchilde/japan/fire.html [17]

74 Hastings, 313.

Thomas Goodrich is a professional writer now living in the US and Europe. His biological father was a US Marine in the Pacific War and his adoptive father was with the US Air Force during the war in Europe.

Summer, 1945—Germany, Japan and the Harvest of Hate can be purchased at Amazon.com, Barnesandnoble.com, Booksamillion.com, and through the author’s website at thomasgoodrich.com. For faster deliver, order via the author’s paypal at mtgoodrich@aol.com [18] ( $20 US / $25 Abroad )

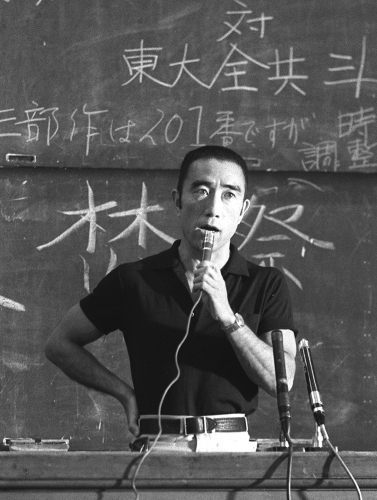

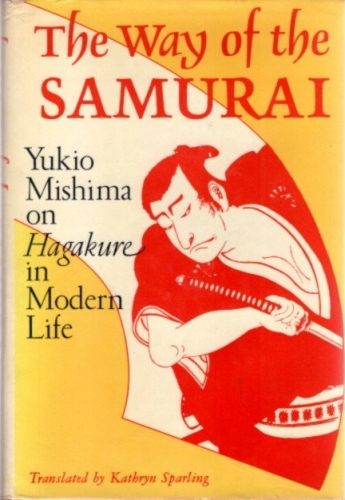

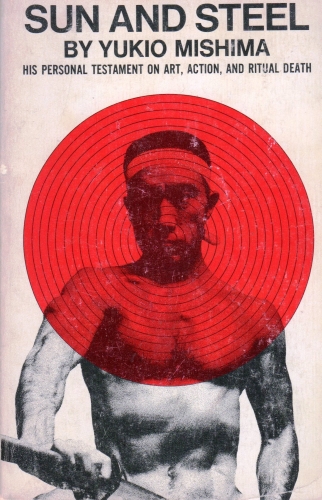

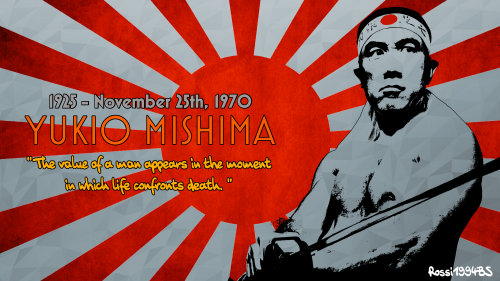

All this having been said, I still encourage people to watch Paul Schrader’s film on Mishima and to read Mishima’s guide to Hagakure (or better yet, Hagakure itself). I will myself, when time permits, try to read Mishima’s later more political fiction (e.g. Runaway Horses) and other nonfiction. A work of art is no less compelling, a logical argument no less persuasive, whatever the author’s personal deficiencies or proclivities.

All this having been said, I still encourage people to watch Paul Schrader’s film on Mishima and to read Mishima’s guide to Hagakure (or better yet, Hagakure itself). I will myself, when time permits, try to read Mishima’s later more political fiction (e.g. Runaway Horses) and other nonfiction. A work of art is no less compelling, a logical argument no less persuasive, whatever the author’s personal deficiencies or proclivities.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Jocho Yamamoto a « écrit » le traité Hagakure au début du siècle des Lumières, quand la crise européenne bat son plein. On passe en trente ans de Bossuet à Voltaire, comme a dit Paul Hazard, et cette descente cyclique est universelle, frappant France, Indes, catholicisme, Japon. J’ai beaucoup expliqué cette époque : retrouvez mes textes sur Voltaire ou sur Swift et la fin du christianisme (déjà…). Le monde moderne va se mettre en place. Mais c’est ce japonais qui alors a le mieux, à ma connaissance, décrit cette chute qui allait nous mener où nous en sommes. On pourra lire mes pages sur les 47 rônins (que bafoue Yamamoto !) dans un de mes livres sur le cinéma. Le Japon, comme dit notre génial Kojève, vit en effet une première Fin de l’Histoire avec cette introduction du shogunat et ce déclin des samouraïs, qui n’incarnèrent pas toujours une époque marrante comme on sait non plus. Voyez les films de Kobayashi, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi et surtout de mon préféré et oublié Iroshi Inagaki.

Jocho Yamamoto a « écrit » le traité Hagakure au début du siècle des Lumières, quand la crise européenne bat son plein. On passe en trente ans de Bossuet à Voltaire, comme a dit Paul Hazard, et cette descente cyclique est universelle, frappant France, Indes, catholicisme, Japon. J’ai beaucoup expliqué cette époque : retrouvez mes textes sur Voltaire ou sur Swift et la fin du christianisme (déjà…). Le monde moderne va se mettre en place. Mais c’est ce japonais qui alors a le mieux, à ma connaissance, décrit cette chute qui allait nous mener où nous en sommes. On pourra lire mes pages sur les 47 rônins (que bafoue Yamamoto !) dans un de mes livres sur le cinéma. Le Japon, comme dit notre génial Kojève, vit en effet une première Fin de l’Histoire avec cette introduction du shogunat et ce déclin des samouraïs, qui n’incarnèrent pas toujours une époque marrante comme on sait non plus. Voyez les films de Kobayashi, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi et surtout de mon préféré et oublié Iroshi Inagaki.

On pourra rappeler de belles analyses sur le roi Lear. On passe au métier de roi, dans la pièce de Shakespeare comme à la cour du roi de France (dixit Macluhan bien sûr au début de sa trop oubliée galaxie). Voyez aussi le Mondain de Voltaire.

On pourra rappeler de belles analyses sur le roi Lear. On passe au métier de roi, dans la pièce de Shakespeare comme à la cour du roi de France (dixit Macluhan bien sûr au début de sa trop oubliée galaxie). Voyez aussi le Mondain de Voltaire.

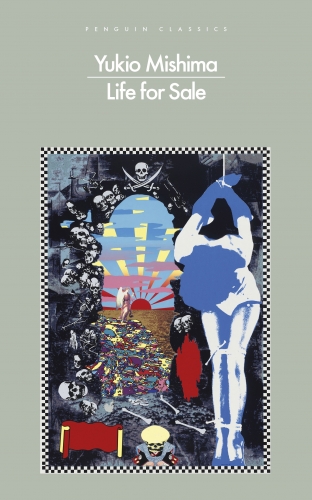

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

The Seven Principles

The Seven Principles No one is normal today. Everyone is a bit mad, with their mind working all the time: they see the world in a narrow, impoverished way. They are consumed by their ego. They think they see, but they are wrong: they are projecting their madness, their world, onto the world. No lucidity, no wisdom in that! That is why Socrates, like Buddha, like all sages, first says, “Know yourself and you will know the universe.” That is the spirit of traditional Zen and Bushido! For this, the observation of one’s behavior is very important. Behavior influences consciousness. With the right behavior, there is the right consciousness. Our attitude here, now, influences the entire environment: our words, our gestures, our bearings, all this influences what happens around us and within us. The actions of every moment, of every day, must be right. The behavior in the dojo will spill over in your daily life. Every gesture is important! How to eat, how to get dressed, how to wash, to go to the toilet, how to put things away, how to behave with others, with one’s family, one’s wife, how to work, how to be completely in each gesture. One must not dream one’s life! But one must be completely in everything we do. This is training in the kata.

No one is normal today. Everyone is a bit mad, with their mind working all the time: they see the world in a narrow, impoverished way. They are consumed by their ego. They think they see, but they are wrong: they are projecting their madness, their world, onto the world. No lucidity, no wisdom in that! That is why Socrates, like Buddha, like all sages, first says, “Know yourself and you will know the universe.” That is the spirit of traditional Zen and Bushido! For this, the observation of one’s behavior is very important. Behavior influences consciousness. With the right behavior, there is the right consciousness. Our attitude here, now, influences the entire environment: our words, our gestures, our bearings, all this influences what happens around us and within us. The actions of every moment, of every day, must be right. The behavior in the dojo will spill over in your daily life. Every gesture is important! How to eat, how to get dressed, how to wash, to go to the toilet, how to put things away, how to behave with others, with one’s family, one’s wife, how to work, how to be completely in each gesture. One must not dream one’s life! But one must be completely in everything we do. This is training in the kata.

Mais avant cela, il faut tout d’abord revenir sur quelques caractéristiques majeurs, ainsi que quelques grands thèmes présents,pour ne pas dire constitutifs, de l’œuvre de Lovecraft. Évidemment il y a tout d’abord ces entités primordiales monstrueuses, ces abominations répondant aux noms de Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep ou bien encore Cthulhu. A l’instar de nombreux éléments qui façonnent l’univers de l’auteur, son panthéon noir est sujet à l’intertextualité : le lecteur retrouvera ces monstruosités dans divers nouvelles indépendantes des unes des autres. Ces horreurs sont également citées dans des livres, le plus souvent des vieux grimoires comme le Necronomicon, les Manuscrits Pnakotiques, l’Unaussprechlichen Kulten,etc, eux-aussi présents dans la plupart des écrits de Lovecraft (et il en est de même pour certains lieux, bien réels ou imaginaires). L’intertextualité constitue une véritable toile de fond qui contribue à la création de l’univers « lovecraftien ».

Mais avant cela, il faut tout d’abord revenir sur quelques caractéristiques majeurs, ainsi que quelques grands thèmes présents,pour ne pas dire constitutifs, de l’œuvre de Lovecraft. Évidemment il y a tout d’abord ces entités primordiales monstrueuses, ces abominations répondant aux noms de Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep ou bien encore Cthulhu. A l’instar de nombreux éléments qui façonnent l’univers de l’auteur, son panthéon noir est sujet à l’intertextualité : le lecteur retrouvera ces monstruosités dans divers nouvelles indépendantes des unes des autres. Ces horreurs sont également citées dans des livres, le plus souvent des vieux grimoires comme le Necronomicon, les Manuscrits Pnakotiques, l’Unaussprechlichen Kulten,etc, eux-aussi présents dans la plupart des écrits de Lovecraft (et il en est de même pour certains lieux, bien réels ou imaginaires). L’intertextualité constitue une véritable toile de fond qui contribue à la création de l’univers « lovecraftien ». Cette dialectique s’accompagne ainsi d’une atmosphère anti-moderne palpable, voir d’un véritable retour à l’archaïque (type de sculptures, d’architectures, de sociétés humaines, etc). Mais, encore une fois, H.P.Lovecraft pouvait également s’intéresser à des « tendances » de son époque, comme l’eugénisme. Certes Lovecraft était raciste et antisémite – les pseudo-journalistes et autres écrivaillons n’oublient jamais de gloser là-dessus bien évidemment – mais c’est surtout la dégénérescence atavique qui est intéressant chez lui. Les nouvelles La peur qui rode et surtout Le cauchemar d’Innsmouth mettent horriblement en avant ces thèmes, voir aussi celui du Destin.

Cette dialectique s’accompagne ainsi d’une atmosphère anti-moderne palpable, voir d’un véritable retour à l’archaïque (type de sculptures, d’architectures, de sociétés humaines, etc). Mais, encore une fois, H.P.Lovecraft pouvait également s’intéresser à des « tendances » de son époque, comme l’eugénisme. Certes Lovecraft était raciste et antisémite – les pseudo-journalistes et autres écrivaillons n’oublient jamais de gloser là-dessus bien évidemment – mais c’est surtout la dégénérescence atavique qui est intéressant chez lui. Les nouvelles La peur qui rode et surtout Le cauchemar d’Innsmouth mettent horriblement en avant ces thèmes, voir aussi celui du Destin. En 1930, une expédition en Antarctique est organisée par l’Université Miskatonic. Celle-ci est composée de nombreux scientifiques et d’étudiants : biologistes, géologues, et physiciens. Ayant établi leur QG sur le mont Erebus, les premières découvertes ne tardent pas à voir le jour. Enthousiasmé, le Professeur Lake décide de poursuivre les recherches au nord-ouest. C’est en arrivant sur place qu’ils vont découvrir une chaîne de montagnes plus haute encore que l’Himalaya. Une fois leur camp installé, l’équipe met à jour une grotte abritant des restes de créatures inconnues, mi-animales, mi-végétales, que le Pr. Lake baptisera « les Anciens », en référence à la description de créatures semblables dans le Necronomicon. Une violente tempête s’abat sur la région et le contact entre les deux équipes est coupée. Le Professeur Dyer décide d’aller aider ses confrères partis au nord-ouest. Sur place, ils ne trouveront que les cadavres horriblement mutilés de l’équipe et des chiens de traîneau. Seul manque à l’appel Gedney, l’assistant de Lake, et un chien…

En 1930, une expédition en Antarctique est organisée par l’Université Miskatonic. Celle-ci est composée de nombreux scientifiques et d’étudiants : biologistes, géologues, et physiciens. Ayant établi leur QG sur le mont Erebus, les premières découvertes ne tardent pas à voir le jour. Enthousiasmé, le Professeur Lake décide de poursuivre les recherches au nord-ouest. C’est en arrivant sur place qu’ils vont découvrir une chaîne de montagnes plus haute encore que l’Himalaya. Une fois leur camp installé, l’équipe met à jour une grotte abritant des restes de créatures inconnues, mi-animales, mi-végétales, que le Pr. Lake baptisera « les Anciens », en référence à la description de créatures semblables dans le Necronomicon. Une violente tempête s’abat sur la région et le contact entre les deux équipes est coupée. Le Professeur Dyer décide d’aller aider ses confrères partis au nord-ouest. Sur place, ils ne trouveront que les cadavres horriblement mutilés de l’équipe et des chiens de traîneau. Seul manque à l’appel Gedney, l’assistant de Lake, et un chien…

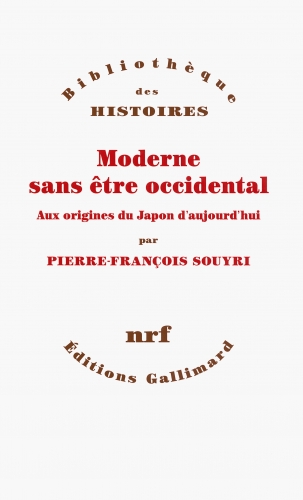

L’identité entre modernisation et occidentalisation du Japon est un des lieux communs les plus véhiculés. Les écrivains, les cinéastes, mais également, ce qui est plus grave, les historiens décrivent souvent un archipel féodal qui aurait embrassé la modernité occidentale en découvrant la puissance nouvelle des empires européens en pleine expansion au milieu du XIXe siècle. Les canonnières britanniques auraient suscité chez ce peuple de tradition isolationniste un sentiment d’urgence et de faiblesse, l’obligeant à rattraper son retard technique, économique et politique. Cette approche considère donc que la modernité japonaise est le produit de l’Occident, que les causes profondes de la transformation de la société japonaise sont exogènes et que ce changement radical peut se comprendre sur le mode de la pure et simple imitation, notamment à travers des tendances nouvelles comme le nationalisme, l’impérialisme ou encore le capitalisme à la japonaise.

L’identité entre modernisation et occidentalisation du Japon est un des lieux communs les plus véhiculés. Les écrivains, les cinéastes, mais également, ce qui est plus grave, les historiens décrivent souvent un archipel féodal qui aurait embrassé la modernité occidentale en découvrant la puissance nouvelle des empires européens en pleine expansion au milieu du XIXe siècle. Les canonnières britanniques auraient suscité chez ce peuple de tradition isolationniste un sentiment d’urgence et de faiblesse, l’obligeant à rattraper son retard technique, économique et politique. Cette approche considère donc que la modernité japonaise est le produit de l’Occident, que les causes profondes de la transformation de la société japonaise sont exogènes et que ce changement radical peut se comprendre sur le mode de la pure et simple imitation, notamment à travers des tendances nouvelles comme le nationalisme, l’impérialisme ou encore le capitalisme à la japonaise.

La modernité japonaise se caractérise également par l’émergence de nationalismes de nature différente. Si les premiers intellectuels de la période Meiji s’interrogèrent sur la possibilité d’un changement de régime pour permettre aux Japonais de disposer de plus de droits individuels (liberté de réunion, d’association, d’expression…) et de véritables libertés politiques, le débat s’est ensuite orienté sur la question de la définition de cette nouvelle identité japonaise. « À partir des années 1887-1888 […], les termes du débat évoluèrent et se cristallisèrent désormais sur la question des identités à l’intérieur de la nation, avec un balancement entre trois éléments, l’Occident et son influence toujours fascinante et menaçante, l’Orient (mais il s’agit surtout de la Chine) qui devint une sorte de terre d’utopie ou d’expansion, et le Japon enfin, dont il fallait sans cesse redéfinir l’essence entre les deux pôles précédents. » Ce qui est particulièrement intéressant dans le cas japonais, c’est que le nationalisme, qui est par excellence une doctrine politique moderne, ne s’est pas seulement constitué à partir du modèle occidental.

La modernité japonaise se caractérise également par l’émergence de nationalismes de nature différente. Si les premiers intellectuels de la période Meiji s’interrogèrent sur la possibilité d’un changement de régime pour permettre aux Japonais de disposer de plus de droits individuels (liberté de réunion, d’association, d’expression…) et de véritables libertés politiques, le débat s’est ensuite orienté sur la question de la définition de cette nouvelle identité japonaise. « À partir des années 1887-1888 […], les termes du débat évoluèrent et se cristallisèrent désormais sur la question des identités à l’intérieur de la nation, avec un balancement entre trois éléments, l’Occident et son influence toujours fascinante et menaçante, l’Orient (mais il s’agit surtout de la Chine) qui devint une sorte de terre d’utopie ou d’expansion, et le Japon enfin, dont il fallait sans cesse redéfinir l’essence entre les deux pôles précédents. » Ce qui est particulièrement intéressant dans le cas japonais, c’est que le nationalisme, qui est par excellence une doctrine politique moderne, ne s’est pas seulement constitué à partir du modèle occidental.

Just as Allied air armadas had mercilessly bombed, blasted and burned the cities and civilians of Germany during World War Two, so too was the US Air Force incinerating the women and children of Germany’s ally, Japan. As was the case with his peers in Europe, cigar-chewing, Jap-hating Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay had no compunction whatsoever about targeting non-combatants, including the very old and the very young.

Just as Allied air armadas had mercilessly bombed, blasted and burned the cities and civilians of Germany during World War Two, so too was the US Air Force incinerating the women and children of Germany’s ally, Japan. As was the case with his peers in Europe, cigar-chewing, Jap-hating Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay had no compunction whatsoever about targeting non-combatants, including the very old and the very young. The Allies first created the firestorm phenomenon when the British in the summer of 1943 bombed Germany’s second largest city, Hamburg. After first blasting the beautiful city to splinters with normal high explosives, another wave of bombers soon appeared loaded with tens of thousands of firebombs. The ensuing night raid ignited numerous fires that soon joined to form one uncontrollable mass of flame. The inferno was so hot, in fact, that it generated its own hurricane-force winds that literally sucked oxygen from the air and suffocated thousands. Other victims were either flung into the hellish vortex like dried leaves or they became stuck in the melting asphalt and quickly burst into flames. LeMay hoped to use this same fiery force to scorch the cities of Japan. Tokyo would be the first test.