Asie du Sud et de l'Est : tendances et perspectives pour 2022

par l'équipe de Katehon.com

Ex: https://www.geopolitica.ru/article/yugo-vostochnaya-aziya-tendencii-i-prognoz-na-2022-g

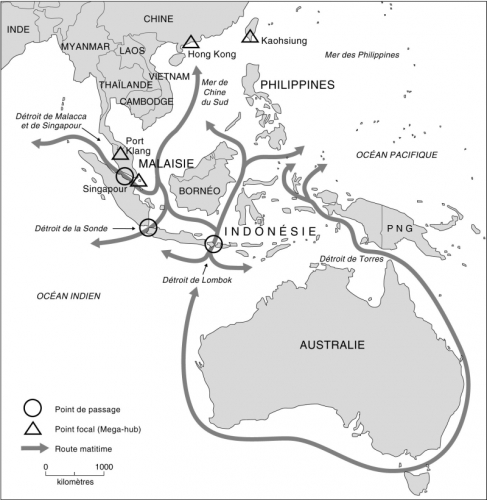

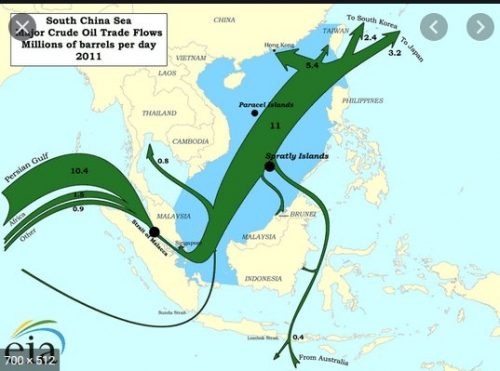

En 2021, le Rimland d'Asie a connu des processus actifs directement liés à la géopolitique mondiale. La Chine étant un pôle nouveau et activement émergent du futur ordre mondial, de nombreux événements étaient directement ou indirectement liés à ce pays. Le découplage, c'est-à-dire la rupture des liens économiques et politiques, a été clairement visible dans les relations avec les États-Unis. Les revendications de souveraineté en mer de Chine méridionale ainsi que la tentative d'unification avec Taïwan (que Pékin considère comme son territoire) ont encouragé les États-Unis et leurs satellites dans la région à intensifier leur coopération et à former ouvertement une coalition anti-chinoise. Le 24 septembre 2021, la première réunion en face à face du dialogue de sécurité quadrilatéral (États-Unis, Japon, Inde et Australie) s'est tenue à Washington et une nouvelle alliance (Australie, Royaume-Uni, États-Unis) a été formée - toutes deux dirigées contre la Chine. "Le Quatuor (Quad) a été créé il y a relativement longtemps - en 2007 - mais jusqu'à récemment, il était peu actif. Ce n'est qu'en 2020 que l'alliance a été relancée et que de nouvelles réunions et de nouveaux accords ont été prévus.

Certains médias ont décrit le Quad comme rien de moins qu'une "OTAN asiatique", bien que cette caractérisation soit plutôt exagérée. De toute évidence, le principal moteur de l'alliance est les États-Unis, qui exploitent habilement les craintes des autres membres à l'égard de la Chine. Mais si l'accord AUKUS est ajouté à ce quatuor, avec la présence du Pentagone dans l'Indo-Pacifique et un certain nombre d'accords bilatéraux, cela ressemble à un pilier supplémentaire pour renforcer la position de l'atlantisme. Et dans un tel format, le Quad sape la sécurité dans la région et la confiance entre les pays qui la composent.

En janvier 2021, l'USS Theodore Roosevelt, un groupe d'attaque centré sur un porte-avions, est entré dans la mer de Chine méridionale pour des opérations de routine, notamment des exercices navals et un entraînement tactique coordonné entre les unités de surface et aériennes.

La nouvelle loi chinoise sur les garde-côtes, qui est entrée en vigueur le 1er février, a été qualifiée par les experts occidentaux et les représentants des pays qui ont des différends territoriaux avec Pékin d'escalade inquiétante des conflits en mer de Chine méridionale.

Les tensions militaires dans la région du Pacifique autour de Taïwan, de Hong Kong et de la mer de Chine méridionale se sont intensifiées à la mi-2021. Les États-Unis ont lancé une série d'exercices dans la région. Les manœuvres, orchestrées par ce fer de lance du Pacifique, se sont déroulées à Guam et dans les îles Mariannes du Nord, avec une démonstration d'une impressionnante puissance aérienne, terrestre et maritime. Il y a également eu un exercice conjoint de deux ans en Australie, appelé Talisman Saber, auquel ont participé 17.000 soldats des États-Unis et de pays alliés.

À la fin de l'année, il était clair que Washington tentait d'inciter ses alliés et partenaires dans la région - Australie, Nouvelle-Zélande, Japon et Corée du Sud - à élaborer une stratégie commune pour contrer la Chine.

Chine

Le sommet du PCC et le plénum du comité central du PCC sont deux événements importants de la politique intérieure chinoise.

Le 6 juillet 2021, un sommet du Parti communiste chinois a été organisé. Lors de ce sommet ouvert du PCC, le 6 juillet, le président chinois Xi Jinping a affirmé la nécessité de s'opposer à une politique de force et d'unilatéralisme dans le monde, et de combattre l'hégémonisme et l'abus de pouvoir politique. "Alors que le monde est entré dans une période de grandes turbulences et de changements, l'humanité est confrontée à divers risques. L'étroite interaction sino-russe constitue un exemple à suivre et un modèle pour l'élaboration d'un nouveau type de relations internationales. Nous apprécions cela", a déclaré Xi Jinping.

Le 6e plénum du 19e Comité central du Parti communiste chinois s'est tenu à Pékin du 8 au 11 novembre 2021.

Selon le communiqué du plénum, le Parti a défini le rôle du camarade Xi Jinping en tant que noyau dirigeant du Comité central du PCC et de l'ensemble du Parti, et a affirmé le rôle directeur des idées de Xi Jinping sur le socialisme aux caractéristiques chinoises dans la nouvelle ère.

En politique étrangère, il y a tout d'abord le découplage avec les États-Unis, qui s'intensifie en raison des changements du modèle économique chinois ainsi que de la perception différente de l'ordre mondial par la RPC et les États-Unis. Tant que les États-Unis suppriment les droits de douane supplémentaires sur les produits chinois, les prix des produits manufacturés, fabriqués en Chine, se situent dans une fourchette de prix moyenne, mais peuvent également baisser de manière significative, ce qui ralentit l'inflation. Toutefois, les États-Unis restent une superpuissance et ne peuvent donc pas éliminer les droits de douane de manière unilatérale.

Dans le cas où l'administration Biden lève les droits de douane supplémentaires sans aucune condition pour la Chine, on peut considérer que Biden a capitulé devant la Chine. Le gouvernement américain exige donc que la Chine augmente ses achats de biens en provenance des États-Unis et mette en œuvre la première phase de l'accord commercial.

Dans le cas où l'administration Biden lève les droits de douane supplémentaires sans aucune condition pour la Chine, on peut considérer que Biden a capitulé devant la Chine. Le gouvernement américain exige donc que la Chine augmente ses achats de biens en provenance des États-Unis et mette en œuvre la première phase de l'accord commercial.

Sinon, l'administration actuelle de Biden aura à cœur de poursuivre les politiques de Trump. En d'autres termes, les États-Unis menacent la Chine. Si la Chine n'augmente pas ses achats de biens aux États-Unis conformément à l'accord, les États-Unis continueront à déclencher la guerre commerciale qui a débuté en 2015. Toutefois, si la Chine augmente ses achats de produits en provenance des États-Unis conformément à l'accord, les États-Unis lèveront les droits de douane déjà imposés sur certains produits chinois.

Les États-Unis utilisent également des tactiques de "propagation de rumeurs" contre la Chine. Il a été signalé publiquement et à plusieurs reprises que la Chine a restreint la production et l'exportation de matériel, produisant des équipements et des dispositifs médicaux de qualité inférieure. Cela a accru la méfiance à l'égard de la chaîne de fabrication chinoise dans de nombreux pays du monde, entraînant une "dé-sinisation de la chaîne de fabrication".

La Chine a également été blâmée pour la chaîne d'approvisionnement "hégémonique" des produits médicaux et de l'industrie automobile chinois, qui serait à l'origine de dommages sanitaires. Le 9 avril 2021, le conseiller économique de la Maison Blanche, Larry Kudlow, a exhorté toutes les entreprises américaines à quitter la Chine et à revenir aux États-Unis, proposant de "compléter" les entreprises pour leur retour dans leur pays d'origine.

Les États-Unis ont lancé une alliance de partenariat appelée Economic Prosperity Network, dont on parle depuis avant Trump. Il encourage la réorganisation des chaînes d'approvisionnement chinoises dans des domaines clés, tels que les infrastructures, etc., dans le but de se débarrasser complètement de la dépendance chinoise. Avec le soutien des États-Unis, le Japon a alloué 2,3 milliards de dollars américains et 108.000 milliards de yens (environ 989 milliards de dollars américains) pour financer des entreprises qui transfèrent des lignes de production de la Chine vers le Japon ou vers d'autres pays.

Cette année 2021 marque exactement les 20 ans de la signature du Traité de bon voisinage, d'amitié et de coopération entre la Fédération de Russie et la République populaire de Chine par Vladimir Poutine et Jiang Zemin à Moscou le 16 juillet 2001 (photo). Aujourd'hui encore, la coopération avec la Chine joue un rôle clé dans la politique étrangère de la Russie. De nombreux analystes et politiciens nationaux présentent la Chine comme un allié géopolitique important.

Lors d'une réunion en ligne entre les deux chefs d'État, Vladimir Poutine a souligné l'importance de la coopération conjointe : "Dans un contexte de turbulences géopolitiques croissantes, de rupture des accords de contrôle des armements et d'augmentation du potentiel de conflit dans diverses régions du monde, la coordination russo-chinoise joue un rôle stabilisateur dans les affaires mondiales. Y compris sur des questions urgentes de l'agenda international telles que la résolution de la situation dans la péninsule coréenne, en Syrie, en Afghanistan, et le renouvellement du plan d'action conjoint sur le programme nucléaire iranien".

Bien qu'il n'y ait pas de croissance particulière du commerce entre la Chine et la Russie. Et ce, malgré le nombre important de projets conjoints sino-russes dans le domaine de la sécurité énergétique, de la coopération dans le cadre de l'initiative "Une ceinture, une route", au sein de l'OCS, de la lutte conjointe contre le terrorisme, etc.

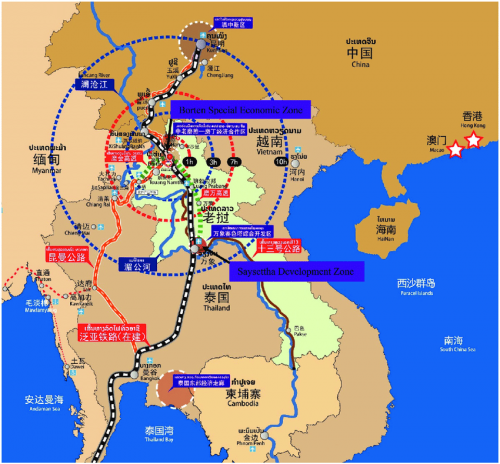

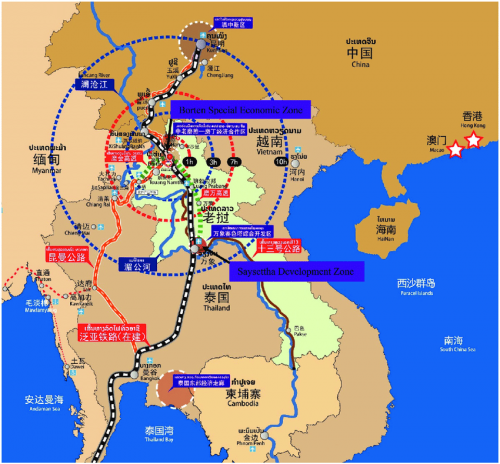

Dans le voisinage immédiat, la Chine a continué à mettre en œuvre des projets d'infrastructure. Au Laos, par exemple, la construction d'une voie ferrée à grande vitesse de 420 km de long, dirigée par la Chine, a été achevée. Les travaux ont commencé en 2016 pour relier la ville de Kunming, dans le sud de la Chine, à la capitale laotienne de Vientiane. Tout cela fait partie de la vision plus large de Pékin concernant un éventuel chemin de fer panasiatique qui s'étendrait au sud jusqu'à Singapour. En tant que projet central de l'initiative "Ceinture et Route", la route fait également partie de la vision stratégique du Laos, qui souhaite passer d'un pays enclavé à un pays "relié à la terre" et combler le fossé de développement dicté par le fait que le Laos est un pays montagneux intérieur.

Il existe une dépendance à l'égard de la Chine dans un contexte d'endettement croissant, mais Vientiane entend rattraper des décennies de développement rapide dans la région. Un autre projet, la construction du port sec de Thanaleng (TDP) et du parc logistique de Vientiane (VLP), est un exemple de la manière dont la dépendance excessive du Laos vis-à-vis de la Chine peut être réduite. Approuvé par une résolution de la Commission économique et sociale des Nations unies pour l'Asie et le Pacifique (CESAP) en 2013, le projet est financé principalement par des sponsors privés et vise à relier le Laos aux routes commerciales maritimes.

Inde

En 2021, l'Inde tente de manœuvrer entre les grands centres géopolitiques, comme auparavant, tout en essayant d'asseoir sa propre influence. Les problèmes de coronavirus freinent l'économie indienne.

Dans le même temps, la victoire des talibans (interdits en Russie) en Afghanistan a obligé New Delhi à modifier ses plans pour l'Asie centrale et l'endiguement du Pakistan. Tout le personnel diplomatique indien et les membres de leurs familles ont été évacués d'Afghanistan, qui avait auparavant été utilisé comme une plateforme pour étendre son influence, y compris dans les périphéries pakistanaises du Baloutchistan et des territoires majoritairement pachtounes.

En février 2021, le différend territorial avec la Chine dans la région montagneuse du Ladakh, où un conflit armé avait eu lieu la veille, a été temporairement résolu. Cependant, les deux parties ont continué à renforcer leur présence militaire à la frontière. À l'automne, un affrontement a eu lieu entre des patrouilles frontalières dans le secteur de Tawang, en Arunachal Pradesh. Le 12 janvier 2022, une nouvelle série de pourparlers a eu lieu entre les commandants de corps d'armée des forces armées indiennes et l'Armée populaire de libération de la Chine. Les tensions devraient se poursuivre tout au long de l'année 2022.

Dans le cadre de la stratégie indo-pacifique, les États-Unis ont continué à attirer l'Inde dans leur sphère d'influence. En septembre 2021, les forces aériennes américaines et indiennes ont signé un nouvel accord de coopération pour développer des véhicules aériens sans pilote. L'objectif de cette collaboration est de "concevoir, développer, démontrer, tester et évaluer des technologies, y compris des équipements physiques tels que des petits véhicules aériens sans pilote, des systèmes d'avionique, d'alimentation de charge utile, de propulsion et de lancement, par le biais du prototypage, qui répondent aux exigences opérationnelles des forces aériennes indiennes et américaines". Le coût prévu de ce projet est de 22 millions de dollars, qui seront répartis à parts égales. Le Pentagone a déjà qualifié l'accord de "plus important de l'histoire" des relations entre les deux pays.

Kelly Seybolt, sous-secrétaire américain de l'armée de l'air pour les affaires internationales, a déclaré : "Les États-Unis et l'Inde partagent une vision commune d'une région indo-pacifique libre et ouverte. Cet accord de développement conjoint renforce encore le statut de l'Inde en tant que partenaire majeur en matière de défense et s'appuie sur notre solide coopération existante dans ce domaine."

Le nouvel accord a été signé sous l'égide de l'initiative américano-indienne en matière de technologie et de commerce de la défense, ou DDTI. Ce projet a débuté en 2012 et était l'un des projets favoris du sous-secrétaire à la défense de l'époque, Ash Carter. Lorsque Carter est devenu ministre en 2015, il a intensifié ses efforts. Ellen Lord, qui a dirigé les achats du Pentagone pour l'administration Trump, a également été un grand défenseur du renforcement des liens de développement avec l'Inde.

Selon le SIPRI, l'Inde était le deuxième plus grand importateur d'équipements militaires et de systèmes d'armes en 2020 et représentait environ 9,5 % de tous les achats d'armes mondiaux. En 2018, les expéditions en provenance des États-Unis ont représenté 12 % de cette part.

Pour changer ce rapport, sous Donald Trump, une exception a même été faite pour que l'Inde coopère avec la Russie. La même année, les responsables du ministère indien ont déclaré qu'ils allaient abandonner les systèmes de défense aérienne russes Pechora et investir un milliard de dollars dans leur équivalent américain, le NASAMS-II.

Et en septembre 2018, les États-Unis et l'Inde ont signé un accord de coopération militaire spécial, l'accord de compatibilité et de sécurité des communications (COMCASA). Il implique le partage de données, l'intensification des exercices conjoints et la fourniture par les États-Unis de types d'armes spécifiques à l'Inde. Bien sûr, l'accord visait également à établir un monopole par les États-Unis. En décembre 2018, l'Inde a inauguré le centre d'information conjoint maritime avec l'aide des États-Unis.

Il est déjà évident que cet accord dans le domaine du développement des forces aériennes entre les deux pays mettait en péril les liens russo-indiens en matière de technologie militaire et de fourniture d'armes. L'Inde aurait pu justifier cela par la nécessité de passer à des produits nationaux.

A la fin de l'année, cependant, la Russie avait effectué une démarche en direction de l'Inde. La visite du président russe Vladimir Poutine en Inde le 6 décembre et les discussions parallèles dans le format 2+2 (ministres des affaires étrangères et de la défense des deux États) ont permis de renouveler plusieurs anciens traités et de signer de nouveaux accords. Alors que la coopération entre Moscou et New Delhi s'est ralentie ces dernières années, le nouveau paquet indique la volonté des deux parties de rattraper le temps perdu, tout en étendant considérablement l'ancien cadre.

Comme indiqué dans la déclaration conjointe sur la réunion, "les parties ont adopté une vision positive des relations multiformes entre l'Inde et la Russie, qui couvrent divers domaines de coopération, notamment la politique et la planification stratégique, l'économie, l'énergie, l'armée et la sécurité, la science et la technologie, la culture et l'interaction humanitaire.

Parmi les accords importants, il convient de mentionner le passage à des règlements mutuels en monnaie nationale, qui constitue une suite logique de la politique russe de sortie de la dépendance au dollar.

L'Inde a également invité la Russie dans le secteur de la défense. Auparavant, les retards dans la signature des contrats entre les parties ont été interprétés comme un désintérêt de New Delhi pour les armements russes et la crainte de sanctions américaines. Mais le sujet de la coopération militaro-technique est également présent dans le nouveau bloc d'accords. Il est révélateur qu'en dépit du programme indien de production de défense nationale, les entreprises russes ont également leur place dans ce secteur. L'expérience antérieure de la coopération entre l'Inde et Israël avait montré qu'une telle entrée sur le marché intérieur indien était possible.

Le Kremlin vise toutefois à trouver un format pratique et acceptable pour que la troïka Russie-Inde-Chine puisse coopérer activement à l'avenir. Il serait bon d'y associer le Pakistan, d'autant que les relations entre Islamabad et New Delhi s'améliorent : la veille, les deux parties ont commencé à s'accorder des visas pour le personnel diplomatique et ont opté pour une désescalade militaire.

Si l'on s'inquiète toujours de l'influence de l'Inde sur les États-Unis, notamment en ce qui concerne la stratégie indo-pacifique, Moscou doit être proactive et proposer elle-même de nouveaux formats d'engagement. En outre, il est nécessaire de surveiller les actions de Washington à cet égard. Jusqu'à présent, rien n'indique clairement qu'il y aura une forte influence sur New Delhi, mais dans le cadre de la politique anti-chinoise globale des États-Unis, ils tenteront de conserver leurs partenaires par le biais de diverses préférences et stratagèmes diplomatiques.

Pakistan

Le Pakistan a intensifié sa politique étrangère en 2021. À la suite du changement de régime en Afghanistan, le Pakistan a déployé des efforts considérables pour normaliser la situation et des responsables ont engagé des pourparlers avec les talibans. Les militaires, y compris l'Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) du Pakistan, ont également participé au processus. Il est important pour le Pakistan d'établir des liens amicaux avec les talibans en tant que force légitime afin de pouvoir influencer la politique pachtoune dans son propre pays. Les talibans pakistanais agissant comme une organisation autonome et étant interdits au Pakistan, Islamabad doit disposer de garanties et d'un levier fiable sur ses zones frontalières peuplées de Pachtounes.

À la fin de l'année, Islamabad a accueilli une réunion de l'Organisation de la coopération islamique, qui a également porté sur un règlement afghan.

Mais la percée la plus importante a été faite dans la direction de la Russie.

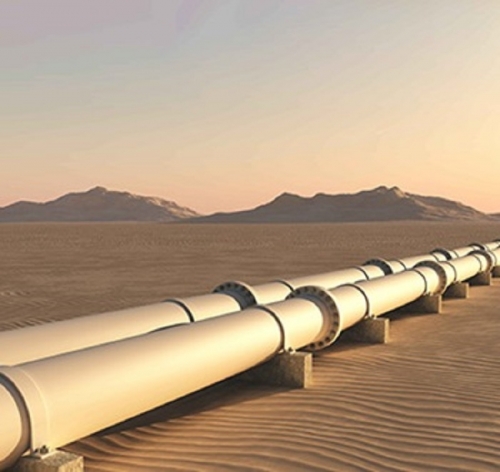

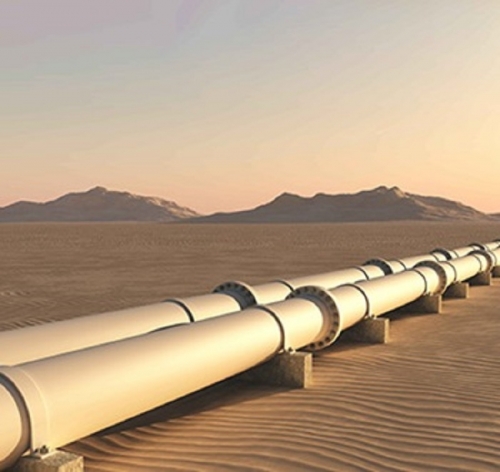

Début avril 2021, Sergey Lavrov s'est rendu à Islamabad pour discuter d'un large éventail de coopération entre les deux pays, allant des questions militaires et techniques à la résolution de la situation dans l'Afghanistan voisin. Évidemment, ce voyage a précipité la signature d'un accord sur un gazoduc (l'autre sujet dans le domaine énergétique était l'atome pacifique). Un message du président russe Vladimir Poutine a également été transmis aux dirigeants pakistanais, indiquant qu'ils étaient prêts à "faire table rase" dans les relations bilatérales.

Le 28 mai, un accord bilatéral sur la construction du gazoduc Pakistan Stream a été signé à Moscou. Du côté russe, le document a été signé par le ministre russe de l'énergie Nikolay Shulginov et, du côté pakistanais, par l'ambassadeur Shafqat Ali Khan.

L'accord est en préparation depuis 2015 sous le nom initial de gazoduc Nord-Sud et revêt une grande importance géopolitique pour les deux pays.

Le nouveau pipeline aura une longueur de 1 100 kilomètres. La capacité sera de 12,3 milliards de mètres cubes par an. Le coût est estimé à 2,5 milliards de dollars. Le gazoduc reliera les terminaux de gaz naturel liquéfié de Karachi et de Gwadar, dans les ports du sud du Pakistan, aux centrales électriques et aux installations industrielles du nord. Initialement, la Russie devait détenir une participation de 51 % et l'exploiter pendant 25 ans. Mais les sanctions occidentales ont bouleversé ces plans. La participation russe sera désormais de 26 %. Mais la partie russe aura un droit de regard décisif sur le choix des contractants, sur la conception, l'ingénierie, les fournitures et la construction.

Le Pakistan a encore deux projets potentiels, le gazoduc iranien, qui n'a pas encore été construit, et le gazoduc Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-Inde (TAPI), qui a fait l'objet d'une grande publicité mais n'a jamais été mis en service. Ce dernier projet a été gelé en raison de la situation instable en Afghanistan. Par conséquent, le Pakistan Stream est le plus prometteur en termes d'attente d'un retour immédiat une fois sa construction achevée.

Pour la Russie, la participation au projet procure un certain nombre d'avantages directs et indirects.

Premièrement, la participation même de la Russie au projet vise à obtenir certains dividendes.

Deuxièmement, la participation de la Russie doit également être considérée sous l'angle de la politique d'image.

Troisièmement, la Russie équilibrera la présence excessive de la Chine au Pakistan, car Pékin est le principal donateur et participant à ces projets d'infrastructure depuis de nombreuses années.

Quatrièmement, la Russie ferait mieux d'explorer les possibilités du corridor économique Chine-Pakistan pour y participer et l'utiliser comme une porte maritime méridionale pour l'UEE (le port en eau profonde de Gwadar). Le gazoduc Pakistan Stream suivrait essentiellement le même itinéraire.

Cinquièmement, étant donné les réserves de gaz naturel au Pakistan même (province du Baloutchistan), la Russie, qui s'est révélée être un partenaire fiable disposant de l'expertise technique nécessaire, pourra, dans un certain temps, participer au développement des champs de gaz nationaux également.

Sixièmement, la présence de la Russie facilitera automatiquement la participation à d'autres projets bilatéraux - avec l'économie dynamique et la croissance démographique du Pakistan, elle élargit les options en matière de commerce, d'industrie et d'affaires.

Septièmement, notre présence renforce la tendance à la multipolarité, en particulier dans une situation où l'Inde suit les États-Unis et s'engage dans divers projets suspects et déstabilisants de type quadrilatéral (comme l'a mentionné le ministre russe des affaires étrangères Sergey Lavrov).

L'amélioration et le développement des contacts avec ce pays sont importants pour la Russie en raison de sa position géostratégique. Tant dans le cadre de l'intégration eurasienne actuelle, y compris en liaison avec l'initiative chinoise "Une ceinture, une route", que dans le cadre de l'intégration continentale à venir.

En 2022, il y a des chances que les relations Pakistan-Russie se développent davantage. La coopération avec la Chine et les autres grands partenaires du Pakistan, la Turquie et l'Arabie saoudite, se poursuivra également.

Japon

En 2021, le Japon a continué à approfondir sa coopération avec les États-Unis en matière de défense et d'économie. Un accord a été conclu selon lequel les coûts d'entretien des bases américaines seront partiellement couverts par le budget du Japon.

À la mi-juillet 2021, le ministère japonais de la défense a publié un livre blanc, qui a suscité l'attention des responsables et des experts des pays voisins ainsi que des États-Unis. Un certain nombre de caractéristiques de ce document indiquent la dynamique de changement dans la planification politico-militaire de cette nation, indiquant que, tout en incitant Washington et en s'engageant dans des projets régionaux tels que le dialogue quadrilatéral sur la sécurité, le Japon reste un satellite fidèle des États-Unis, mettant l'accent sur des préoccupations identiques.

D'après l'introduction du Livre blanc, il semble que le Japon ait désormais deux menaces principales - la Chine et la Corée du Nord.

C'est la première fois que le ministère japonais de la défense supprime Taïwan de la carte de la Chine. Les années précédentes, le livre blanc regroupait Taïwan et la Chine dans un même chapitre et sur une même carte, ce qui suscitait des critiques de la part des Taïwanais vivant au Japon. Toutefois, la dernière version souligne la distinction entre les deux, ce qui indique un changement de politique de la part du ministre japonais de la Défense, Nobuo Kishi.

Le document souligne que "la stabilisation de la situation autour de Taïwan est importante pour la sécurité du Japon et la stabilité de la communauté internationale." Le document ajoute : "Il est donc plus que jamais nécessaire que nous accordions une attention particulière à la situation à l'approche de la crise."

En ce qui concerne les secteurs préoccupants, les préoccupations du Japon sont les suivantes :

- la défense d'îles éloignées ;

- organiser une réponse efficace à d'éventuelles attaques de missiles ;

- la possibilité d'agir dans l'espace ;

- sécuriser les cyber-systèmes ;

- le développement des capacités du spectre électromagnétique ;

- la réponse aux grandes catastrophes et aux calamités naturelles (y compris l'épidémie de coronavirus).

Il y a eu peu de changement dans la politique intérieure. Le 31 octobre 2021, des élections législatives ont eu lieu au Japon. Selon la procédure, un premier ministre a été nommé. Le Premier ministre sortant, Fumio Kishida, a conservé son poste, le parti qu'il dirige ayant conservé la majorité des sièges au Parlement.

Myanmar

Le 1er février 2021, un coup d'État au Myanmar a renversé un gouvernement civil dirigé par la Ligue nationale pour la démocratie (LND), conduite par Aung San Suu Kyi et Win Myint. Les militaires du pays, les Tatmadaw, ont instauré une dictature dans l'État. Le nouveau gouvernement militaire a promis d'organiser des élections générales dans un an ou deux, puis de remettre le pouvoir au vainqueur.

Les députés de la NLD, qui ont conservé leur liberté, ont formé un comité d'ici avril 2021 pour représenter le Parlement de l'Union, un organe parallèle au gouvernement, que le gouvernement militaire a déclaré association illégale et a accusé ses membres de haute trahison. Aung San Suu Kyi a été arrêtée et jugée.

En juin 2021, le généralissime Min Aung Hline a conduit une délégation du Myanmar en Russie pour assister à la conférence de Moscou sur la sécurité internationale.

Min Aung Hline s'est déjà rendu plusieurs fois en Russie, mais c'est la première fois en tant que chef d'État. Min Aung Hline a toujours soutenu le développement des relations avec notre pays, en particulier dans les domaines militaire et militaro-technique. Au début des années 2000, il a élaboré un programme de formation pour les militaires birmans de la Fédération de Russie (plus de 7000 officiers ont étudié dans les universités russes au cours de ces années). Sous sa direction, le Myanmar a commencé à acheter des avions d'entraînement au combat Yak-130, des chasseurs polyvalents Su-30SM, des véhicules blindés, etc.

Cette visite a coïncidé avec un regain de pression internationale sur le Myanmar : le vendredi 18 juin, l'Assemblée générale des Nations unies a condamné les actions de l'armée au Myanmar. 119 pays ont soutenu la proposition visant à rétablir la transition démocratique dans le pays, le Belarus s'y est opposé et 36 pays (dont la Russie et la Chine) se sont abstenus.

Pour la Russie elle-même, la coopération avec le Myanmar est bénéfique non seulement en termes de fourniture d'équipements militaires et de formation du personnel militaire du pays asiatique. Le soutien politique (ou la neutralité) de Moscou souligne la ligne générale de sa politique étrangère - non-ingérence dans les affaires intérieures des autres États et respect de la souveraineté - tout en rejetant le concept occidental de "protection des valeurs démocratiques". Le rôle d'une sorte d'équilibre, d'équilibrage de l'influence chinoise, est également assez commode pour Moscou. Et dans le contexte de la géopolitique mondiale, il suffit de regarder la carte pour comprendre l'importance stratégique de cet État d'une superficie de 678.000 kilomètres carrés, situé au centre de l'Asie du Sud-Est et ayant accès à l'océan Indien.

Projets régionaux-mondiaux

Le 9 janvier 2021, le site web du Conseil d'État de la République populaire de Chine a publié une annonce selon laquelle la Chine va étendre son réseau de libre-échange dans le monde. Selon le ministre du commerce Wang Wentao, la Chine intensifiera ses efforts pour accroître son réseau de zones de libre-échange avec ses partenaires du monde entier afin d'élargir son "cercle d'amis", tout en éliminant les droits de douane supplémentaires sur les marchandises et en facilitant les investissements et l'accès au marché pour le commerce des services.

Wang a déclaré à l'agence de presse Xinhua, dans une récente interview, que ces efforts favoriseraient l'ouverture à un niveau supérieur. Il a ajouté que le pays allait promouvoir les négociations sur un accord de libre-échange entre la Chine, le Japon et la République de Corée, les négociations avec le Conseil de coopération Chine-Golfe, ainsi que les accords de libre-échange (ALE) Chine-Norvège et Chine-Israël. En outre, l'adhésion à l'accord global et progressif de partenariat transpacifique sera envisagée.

Les chiffres officiels montrent que la Chine a signé des ALE avec 26 pays et régions, les ALE représentant 35 % du commerce extérieur total du pays.

La création d'un réseau de zones de libre-échange d'envergure mondiale est conforme à l'objectif de la Chine de créer un nouveau niveau d'ouverture à l'échelle mondiale, comme le soulignent les propositions de la direction du parti pour le 14e plan quinquennal (2021-2025) de développement économique et social national et les objectifs à long terme jusqu'en 2035.

La signature d'un plus grand nombre d'ALE aiderait la Chine à étendre et à stabiliser ses marchés étrangers et à atteindre un niveau d'ouverture plus élevé, surtout si le pays procède activement à des ajustements pour répondre aux exigences nécessaires, comme l'adoption de réglementations environnementales plus strictes et l'égalisation des conditions de concurrence pour tous les acteurs du marché.

En plus de faciliter le commerce des biens et des services, les ALE constituent également des plateformes permettant d'établir des règles largement acceptées et reconnues dans des domaines tels que l'économie numérique et la protection de l'environnement.

La Chine a fait des progrès notables dans la promotion du commerce multilatéral en 2020, en signant un partenariat économique global régional à la mi-novembre et en concluant les négociations sur le traité d'investissement Chine-UE plus tard dans l'année.

Le 1er janvier 2022, l'accord sur la plus grande zone de libre-échange du monde - le Partenariat économique global régional - est entré en vigueur (l'accord a été signé en novembre 2020). L'accord couvre 10 États membres de l'Association des nations de l'Asie du Sud-Est et 5 États avec lesquels l'ANASE a déjà signé des accords de libre-échange. Le RCEP comprend 3 pays développés et 12 pays en développement.

La région Asie-Pacifique est aujourd'hui la première région de croissance économique du monde, offrant de grandes possibilités de commerce et d'expansion. Certains pays pensent que leurs entreprises peuvent prendre de l'avance dans la course à la concurrence grâce à l'accord global et progressif sur le partenariat transpacifique (CPTPP) - un accord de libre-échange entre 11 pays de la région Asie-Pacifique : Australie, Brunei, Chili, Canada, Japon, Malaisie, Mexique, Nouvelle-Zélande, Pérou, Singapour et Vietnam.

En substance, le CPTPP est un accord de libre-échange ambitieux et de grande qualité qui couvre pratiquement tous les aspects du commerce et de l'investissement. L'accord comprend des engagements en matière d'accès au marché pour le commerce des biens et des services, des engagements en matière d'investissement, de mobilité de la main-d'œuvre et de marchés publics. L'accord établit également des règles claires pour aider à créer un environnement cohérent, transparent et équitable pour faire des affaires sur les marchés du CPTPP, avec des chapitres dédiés couvrant des questions clés telles que les obstacles techniques au commerce, les mesures sanitaires et phytosanitaires, l'administration douanière, la transparence et les entreprises d'État.

Un État qui souhaite adhérer doit en informer le gouvernement néo-zélandais (le dépositaire de l'accord), qui informera ensuite les autres membres. La Commission du CPTPP décide ensuite de lancer ou non le processus d'adhésion. S'il décide de lancer le processus, un groupe de travail sera formé. Dans les 30 jours suivant la première réunion du groupe de travail, le candidat devra soumettre ses propositions en matière d'accès au marché : réductions tarifaires ; listes des secteurs de services dont il a proposé d'exclure les membres du CPTPP ; et parties des marchés publics qui ne seront pas ouvertes aux propositions des autres membres du CPTPP. Le processus de négociation commencera alors. Une fois que tous les participants existants sont satisfaits, la Commission invitera officiellement un candidat à devenir membre.

Au début de l'année 2021, la Grande-Bretagne a demandé à adhérer au CPTPP. Cependant, on n'a toujours pas de nouvelles sur l'état d'avancement des aspirations de Londres. Tout ce que l'on sait, c'est que les négociations ont été lancées en juin.

En janvier 2021, la Corée du Sud a également déclaré son désir de rejoindre le CPTPP. Pour ce faire, une procédure a été lancée pour examiner ses propres règlements et lois afin de vérifier leur conformité avec le CPTPP. La Thaïlande a également manifesté son intérêt pour le partenariat.

Et en septembre 2021, la Chine s'est portée candidate. Cela s'est produit quelques jours seulement après la signature du traité AUKUS.

***

En 2022, la région restera une zone d'intérêts contradictoires entre les puissances mondiales. Le Cachemire continuera d'être un point de conflit (la zone de contrôle indienne est la plus problématique, car New Delhi ne permet à aucune tierce partie de participer au règlement), mais une escalade est peu probable sans provocations graves. Nous ne devons pas non plus nous attendre à une invasion chinoise de Taïwan, comme le disent les politiciens américains et leurs médias contrôlés. Les États-Unis et leurs partenaires poursuivront les exercices militaires de routine et tenteront de former une coalition anti-chinoise plus impressionnante.

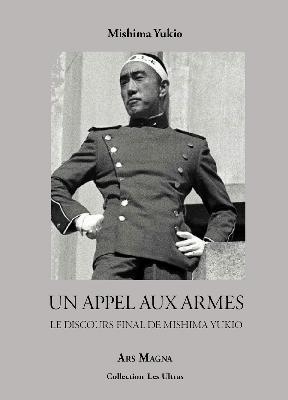

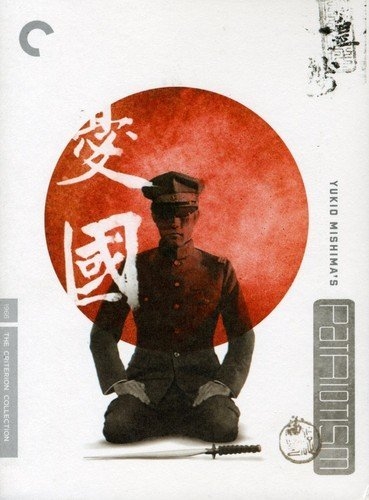

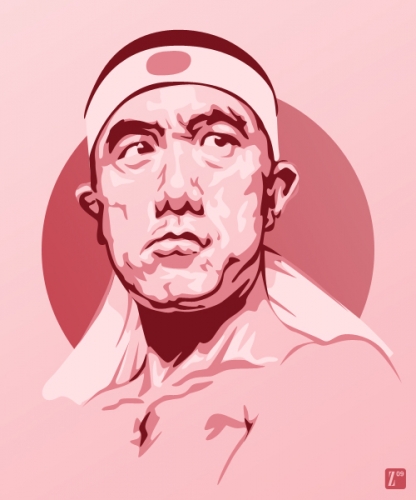

Par-delà le rôle moteur de l’armée, Mishima Yukio défend le rétablissement de la pleine souveraineté de Tokyo. Or, il sait que son pays sorti des ruines de l’après-guerre est une colonie de l’Occident anglo-saxon. « Le soi-disant contrôle par le pouvoir civil des militaires anglais et américains est uniquement un contrôle financier (p. 25). » Il dénonce que l’île méridionale d’Okinawa soit encore sous la tutelle de Washington. Il ignore que les États-Unis la rétrocéderont au Japon en 1972. Il s’offusque que le Japon signe le traité de non-prolifération nucléaire et renonce ainsi à la détention d’une force de frappe atomique. Clairvoyant, il prévient que la soumission du Jieitai aux vainqueurs de 1945 en fera, « comme les gauchistes l’ont remarqué, une force mercenaire de l’Amérique pour toujours (p. 27) ».

Par-delà le rôle moteur de l’armée, Mishima Yukio défend le rétablissement de la pleine souveraineté de Tokyo. Or, il sait que son pays sorti des ruines de l’après-guerre est une colonie de l’Occident anglo-saxon. « Le soi-disant contrôle par le pouvoir civil des militaires anglais et américains est uniquement un contrôle financier (p. 25). » Il dénonce que l’île méridionale d’Okinawa soit encore sous la tutelle de Washington. Il ignore que les États-Unis la rétrocéderont au Japon en 1972. Il s’offusque que le Japon signe le traité de non-prolifération nucléaire et renonce ainsi à la détention d’une force de frappe atomique. Clairvoyant, il prévient que la soumission du Jieitai aux vainqueurs de 1945 en fera, « comme les gauchistes l’ont remarqué, une force mercenaire de l’Amérique pour toujours (p. 27) ».

Dans le cas où l'administration Biden lève les droits de douane supplémentaires sans aucune condition pour la Chine, on peut considérer que Biden a capitulé devant la Chine. Le gouvernement américain exige donc que la Chine augmente ses achats de biens en provenance des États-Unis et mette en œuvre la première phase de l'accord commercial.

Dans le cas où l'administration Biden lève les droits de douane supplémentaires sans aucune condition pour la Chine, on peut considérer que Biden a capitulé devant la Chine. Le gouvernement américain exige donc que la Chine augmente ses achats de biens en provenance des États-Unis et mette en œuvre la première phase de l'accord commercial.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

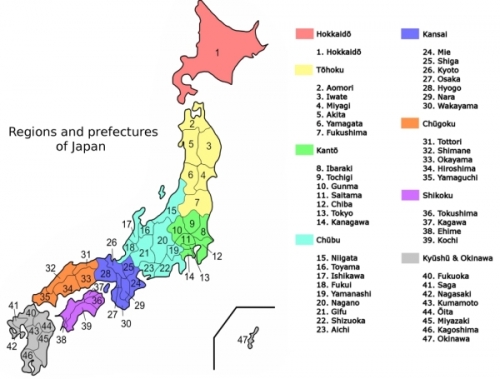

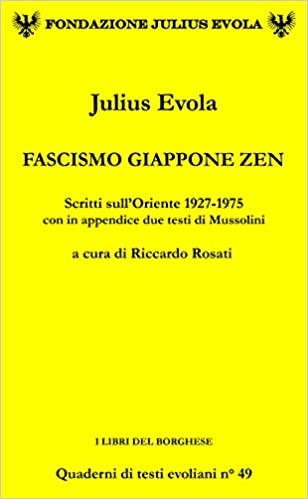

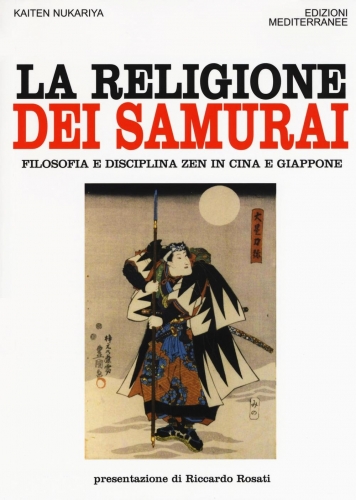

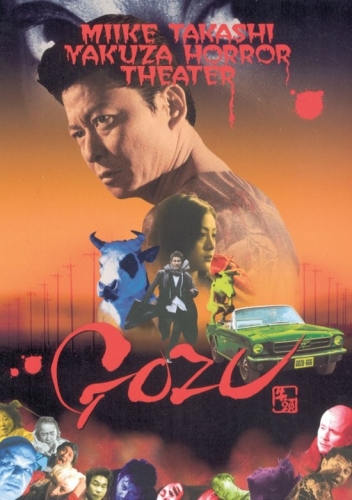

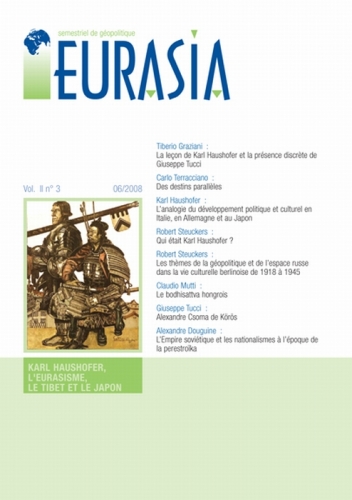

En résumé, nous pouvons constater qu'il y a de nombreuses cartes et graphiques dans cet intéressant numéro de Limes, comme pour réitérer la primauté de la géographie sur la philosophie politique si chère à Haushofer lui-même. Ce n'est pas pour rien qu'il est à l'origine de la création de l'école géopolitique japonaise, qui a fortement orienté les choix du gouvernement pendant la période du militarisme. Certains des principes fondateurs du Nippon Chiseigaku (chi/terre [地], sei/politique [政], gaku/étude [学]) visaient à dénoncer la "brutalité des Blancs", dont Julius Evola fut le premier à parler dans son article, comme toujours prophétique: Oracca all'Asia. Il tramonto dell'Oriente (initialement publié dans Il Nazionale, II, 41, 8 octobre 1950 et maintenant inclus dans Julius Evola, Fascismo Giappone Zen. Scritti sull'Oriente 1927 - 1975, Riccardo Rosati [ed.], Rome, Pages, 2016). Pour les Japonais, leur expansion imparable en Asie était une "guerre de libération de la domination coloniale blanche" (23). Et, comme le rapporte à juste titre l'Editorial cité ici, l'apport de la pensée de Haushofer a été d'une énorme importance dans la structuration d'une haute idée de l'impérialisme japonais: "Le pan-continentalisme de l'école haushoferienne a contribué à structurer le projet de la Grande Asie orientale [...]" (26).

En résumé, nous pouvons constater qu'il y a de nombreuses cartes et graphiques dans cet intéressant numéro de Limes, comme pour réitérer la primauté de la géographie sur la philosophie politique si chère à Haushofer lui-même. Ce n'est pas pour rien qu'il est à l'origine de la création de l'école géopolitique japonaise, qui a fortement orienté les choix du gouvernement pendant la période du militarisme. Certains des principes fondateurs du Nippon Chiseigaku (chi/terre [地], sei/politique [政], gaku/étude [学]) visaient à dénoncer la "brutalité des Blancs", dont Julius Evola fut le premier à parler dans son article, comme toujours prophétique: Oracca all'Asia. Il tramonto dell'Oriente (initialement publié dans Il Nazionale, II, 41, 8 octobre 1950 et maintenant inclus dans Julius Evola, Fascismo Giappone Zen. Scritti sull'Oriente 1927 - 1975, Riccardo Rosati [ed.], Rome, Pages, 2016). Pour les Japonais, leur expansion imparable en Asie était une "guerre de libération de la domination coloniale blanche" (23). Et, comme le rapporte à juste titre l'Editorial cité ici, l'apport de la pensée de Haushofer a été d'une énorme importance dans la structuration d'une haute idée de l'impérialisme japonais: "Le pan-continentalisme de l'école haushoferienne a contribué à structurer le projet de la Grande Asie orientale [...]" (26). Aujourd'hui, c'est un devoir pour un japonologue qui n'est pas esclave du globalisme de parler d'un Japon très différent, peut-être même meilleur et plus fort que celui que nous aimions quand nous étions enfants, puisqu'il est redevenu un Pays/Peuple, ce dont nous, Italiens, ne parvenons jamais à comprendre l'importance.

Aujourd'hui, c'est un devoir pour un japonologue qui n'est pas esclave du globalisme de parler d'un Japon très différent, peut-être même meilleur et plus fort que celui que nous aimions quand nous étions enfants, puisqu'il est redevenu un Pays/Peuple, ce dont nous, Italiens, ne parvenons jamais à comprendre l'importance.

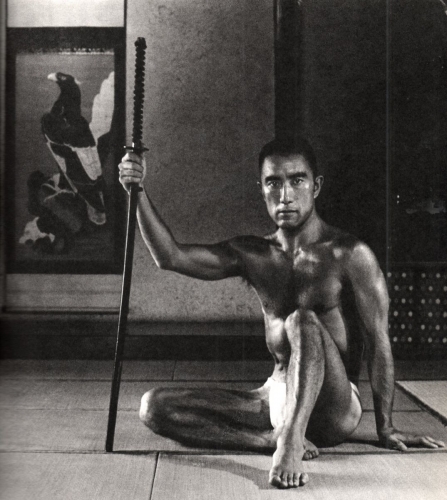

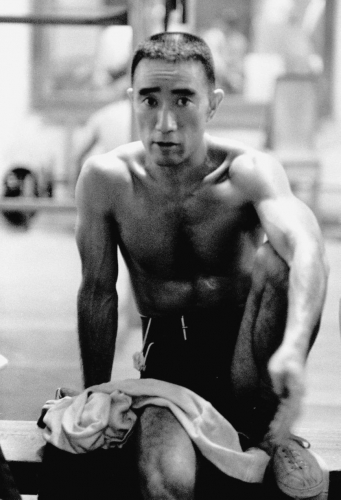

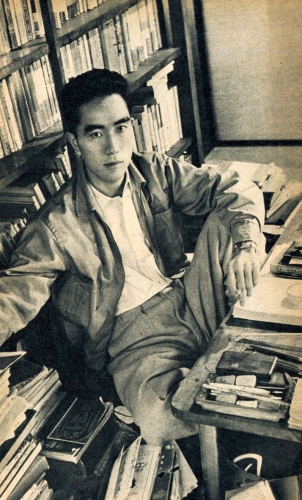

"Mishima, pour reprendre la précieuse définition qu'en donne Marguerite Yourcenar dans son excellent Mishima ou la Vision du vide (1980), est un "univers" dans lequel, en fait, le côté esthétique - je l'explique dans mon livre - joue un rôle prépondérant. À cet élément, le grand intellectuel et écrivain japonais a ajouté la discipline martiale/militaire, sous le signe de la redécouverte d'un héritage capital de cette culture japonaise traditionnelle à laquelle il s'est référé, dans la " deuxième partie " de sa vie, avec vigueur et rigueur ; à savoir le Bunbu Ryōdō (文武両道, la Voie de la vertu littéraire et guerrière), où la plume devient métaphoriquement une épée.

"Mishima, pour reprendre la précieuse définition qu'en donne Marguerite Yourcenar dans son excellent Mishima ou la Vision du vide (1980), est un "univers" dans lequel, en fait, le côté esthétique - je l'explique dans mon livre - joue un rôle prépondérant. À cet élément, le grand intellectuel et écrivain japonais a ajouté la discipline martiale/militaire, sous le signe de la redécouverte d'un héritage capital de cette culture japonaise traditionnelle à laquelle il s'est référé, dans la " deuxième partie " de sa vie, avec vigueur et rigueur ; à savoir le Bunbu Ryōdō (文武両道, la Voie de la vertu littéraire et guerrière), où la plume devient métaphoriquement une épée.

" Disons d'abord que Mishima était un admirateur du Vate, au point de traduire en 1965 l'une de ses œuvres : Le martyre de Saint Sébastien (1911). Outre la similitude immédiate de leurs personnalités, qui partagent une exaltation bien connue de l'action virile et de l'audace, il est utile de souligner qu'il existait également une proximité artistique entre les deux. Tous deux, bien qu'appartenant à des époques et des contextes culturels différents, relèvent de ce que les critiques littéraires appellent le "décadentisme". C'est-à-dire une déclinaison du romantisme où l'esthétique se greffe sur un "personnalisme" presque exagéré et, parfois, enclin à la désillusion, où apparaissent également des relents de dandysme.

" Disons d'abord que Mishima était un admirateur du Vate, au point de traduire en 1965 l'une de ses œuvres : Le martyre de Saint Sébastien (1911). Outre la similitude immédiate de leurs personnalités, qui partagent une exaltation bien connue de l'action virile et de l'audace, il est utile de souligner qu'il existait également une proximité artistique entre les deux. Tous deux, bien qu'appartenant à des époques et des contextes culturels différents, relèvent de ce que les critiques littéraires appellent le "décadentisme". C'est-à-dire une déclinaison du romantisme où l'esthétique se greffe sur un "personnalisme" presque exagéré et, parfois, enclin à la désillusion, où apparaissent également des relents de dandysme.

Au Japon, les arts martiaux ont des origines très anciennes et sont profondément ancrés dans la culture traditionnelle du pays. Parmi les disciplines qui, de ce point de vue, sont les plus éloignées dans le temps, il y a certainement le tir à l'arc, qui se pratiquait à pied ou à cheval. Dans ce dernier cas, on parle de yabusame alors que dans le premier cas, on parle de kyujutsu. C’est donc l'ancêtre du Kyudo, discipline plus moderne.

Au Japon, les arts martiaux ont des origines très anciennes et sont profondément ancrés dans la culture traditionnelle du pays. Parmi les disciplines qui, de ce point de vue, sont les plus éloignées dans le temps, il y a certainement le tir à l'arc, qui se pratiquait à pied ou à cheval. Dans ce dernier cas, on parle de yabusame alors que dans le premier cas, on parle de kyujutsu. C’est donc l'ancêtre du Kyudo, discipline plus moderne. Deux mots sur les instruments et la pratique du Kyudo: tout d'abord l'arc (yumi). Il est grand (environ 2 mètres) et il est fait d'éléments en bois et en bambou, ce qui le rend élastique et résistant à la fois. Les flèches étaient et sont de formes et de matériaux différents selon leur utilisation et leur lieu de fabrication. Quant aux compétitions, on lance généralement une cible à 28 ou 60 mètres et le vainqueur est décrété non seulement en fonction du nombre de flèches qui ont atteint la cible (efficacité du tir) mais aussi en fonction de l'exécution correcte des mouvements et des positions de base. En effet, le but du Kyudo n'est pas seulement de participer à des compétitions, mais de cultiver l'esprit et le corps comme une méthode d'amélioration de soi par la recherche de la perfection du tir combinée à la pureté de l'esprit et à l'harmonie intérieure et extérieure.

Deux mots sur les instruments et la pratique du Kyudo: tout d'abord l'arc (yumi). Il est grand (environ 2 mètres) et il est fait d'éléments en bois et en bambou, ce qui le rend élastique et résistant à la fois. Les flèches étaient et sont de formes et de matériaux différents selon leur utilisation et leur lieu de fabrication. Quant aux compétitions, on lance généralement une cible à 28 ou 60 mètres et le vainqueur est décrété non seulement en fonction du nombre de flèches qui ont atteint la cible (efficacité du tir) mais aussi en fonction de l'exécution correcte des mouvements et des positions de base. En effet, le but du Kyudo n'est pas seulement de participer à des compétitions, mais de cultiver l'esprit et le corps comme une méthode d'amélioration de soi par la recherche de la perfection du tir combinée à la pureté de l'esprit et à l'harmonie intérieure et extérieure.

Le maître ajoute :

Le maître ajoute :

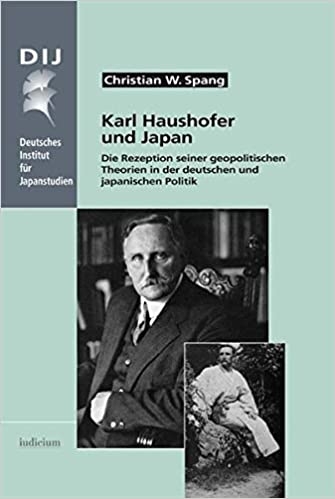

La maison d'édition de Parme, méritante et courageuse, All’Insegna del Veltro, dirigée par l'excellent traditionaliste Claudio Mutti, a publié, il y a déjà quelques années, plusieurs textes fondamentaux du savant et yamatologue (= japonologue) allemand Karl Haushofer (1869-1946), fondateur en 1924 de la prestigieuse Zeitschrift für Geopolitik ("Revue de géopolitique") et auteur de nombreux ouvrages liés à la géopolitique. Il était un défenseur tenace de la nécessité d’unir la masse continentale eurasienne. Dénoncé comme un idéologue du soi-disant expansionnisme d'Hitler, Haushofer était au contraire authentiquement anti-impérialiste. D'ailleurs, son plus grand connaisseur dans notre mouvance, le Belge Robert Steuckers, est profondément convaincu que la Géopolitique de Haushofer était précisément "non hégémonique", en opposition aux intrigues des puissances thalassocratiques anglo-saxonnes voulant une domination totale sur le monde, puisque ces dernières empêchaient le développement harmonieux des peuples qu'elles soumettaient et divisaient inutilement les continents.

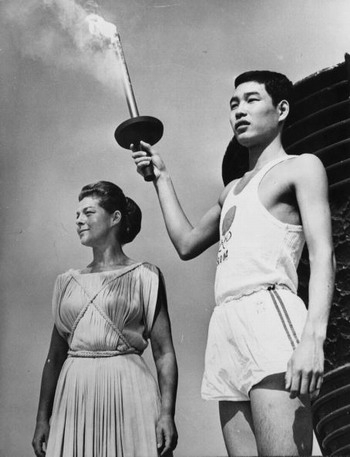

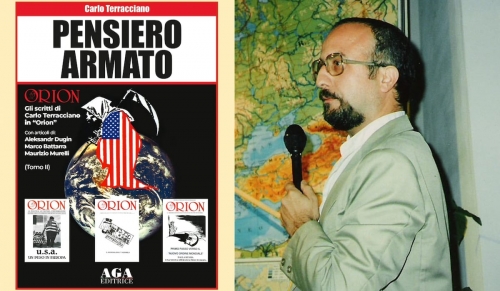

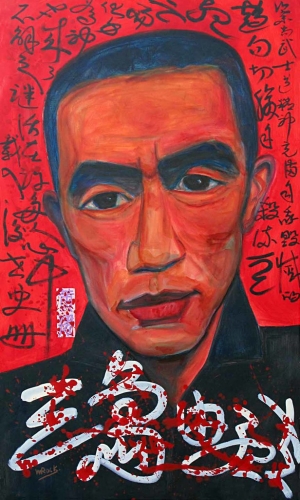

La maison d'édition de Parme, méritante et courageuse, All’Insegna del Veltro, dirigée par l'excellent traditionaliste Claudio Mutti, a publié, il y a déjà quelques années, plusieurs textes fondamentaux du savant et yamatologue (= japonologue) allemand Karl Haushofer (1869-1946), fondateur en 1924 de la prestigieuse Zeitschrift für Geopolitik ("Revue de géopolitique") et auteur de nombreux ouvrages liés à la géopolitique. Il était un défenseur tenace de la nécessité d’unir la masse continentale eurasienne. Dénoncé comme un idéologue du soi-disant expansionnisme d'Hitler, Haushofer était au contraire authentiquement anti-impérialiste. D'ailleurs, son plus grand connaisseur dans notre mouvance, le Belge Robert Steuckers, est profondément convaincu que la Géopolitique de Haushofer était précisément "non hégémonique", en opposition aux intrigues des puissances thalassocratiques anglo-saxonnes voulant une domination totale sur le monde, puisque ces dernières empêchaient le développement harmonieux des peuples qu'elles soumettaient et divisaient inutilement les continents. Outre la géopolitique, la plus grande passion intellectuelle du professeur et général bavarois était le Japon, qu'il a analysé, à son époque, avant la première guerre mondiale, d'un point de vue absolument original. Pour démontrer l’excellence et l'utilité des écrits de Haushofer sur le Pays du Soleil Levant, il faut mentionner un fait : il a été impliqué par le grand orientaliste italien Giuseppe Tucci (1894 - 1984) (photo) dans les activités de l'IsMEO (Institut italien pour le Moyen-Orient et l'Extrême-Orient). En effet, il a été invité à Rome par cet institut pour donner deux conférences. Son texte, Le développement de l'idée impériale japonaise, n'est qu’un extrait de la deuxième conférence donnée par Haushofer, le 6 mars 1941, en pleine Seconde Guerre mondiale ! Le texte est à insérer, historiquement, comme le souligne l'éditeur du "Cahier", le regretté Carlo Terracciano, dans le contexte des activités culturelles promues par Tucci lui-même.Celui-ci visait à informer et à sensibiliser l'intelligentsia italienne sur les opportunités et les nécessités, ainsi que sur les problèmes, de l'unité géopolitique de l'Eurasie, afin d'orienter la politique nationale vers la promotion d'une vision culturelle géopolitiquement centrée sur les relations entre l'Europe et le continent asiatique.

Outre la géopolitique, la plus grande passion intellectuelle du professeur et général bavarois était le Japon, qu'il a analysé, à son époque, avant la première guerre mondiale, d'un point de vue absolument original. Pour démontrer l’excellence et l'utilité des écrits de Haushofer sur le Pays du Soleil Levant, il faut mentionner un fait : il a été impliqué par le grand orientaliste italien Giuseppe Tucci (1894 - 1984) (photo) dans les activités de l'IsMEO (Institut italien pour le Moyen-Orient et l'Extrême-Orient). En effet, il a été invité à Rome par cet institut pour donner deux conférences. Son texte, Le développement de l'idée impériale japonaise, n'est qu’un extrait de la deuxième conférence donnée par Haushofer, le 6 mars 1941, en pleine Seconde Guerre mondiale ! Le texte est à insérer, historiquement, comme le souligne l'éditeur du "Cahier", le regretté Carlo Terracciano, dans le contexte des activités culturelles promues par Tucci lui-même.Celui-ci visait à informer et à sensibiliser l'intelligentsia italienne sur les opportunités et les nécessités, ainsi que sur les problèmes, de l'unité géopolitique de l'Eurasie, afin d'orienter la politique nationale vers la promotion d'une vision culturelle géopolitiquement centrée sur les relations entre l'Europe et le continent asiatique. L'Allemand, dans le rapport qu’il a exposé à Rome, propose un parallélisme continu entre l'histoire européenne et japonaise : "[...] les luttes sauvages entre Taira et Minamoto, semblables à la guerre des Deux Roses, [...]" (18). Il souligne ainsi ce destin commun de l'histoire européenne et japonaise. (18), destin commun auquel il croyait obstinément. Tucci a été très impressionné par le caractère non fictionnel de la spéculation de Haushofer, par le fait que le géopolitologue a reconnu la primauté de Rome et de l'Italie en général, afin de construire une alliance avec le Japon qui ne soit pas seulement politique, mais spirituelle ; par exemple, lorsqu'il compare Kitabatake Chikafusa (1293-1354) à Dante (19), puisque tous deux ont été les auteurs de grands "poèmes politiques". Cela l'amène à déclarer que la Divine Comédie a trouvé une grande résonance dans le Jinnoshiki contemporain (神皇正統記, "Jinnō shōtōki", ca. 1339) de Kitabatake, qui peut raisonnablement être considéré comme un classique de la pensée politique japonaise, où les principes de légitimité de la lignée impériale ont été établis, conformément à la tradition shintoïste. Un tel texte, dans son ancrage de la "légitimité politique" à une matrice religieuse, ne pouvait qu'attirer l'intérêt des Allemands, qui en appréciaient les valeurs, ce qui aurait pu être une inspiration pour les nations occidentales non asservies à l'Economie et à la recherche de formules éthico-politiques sur lesquelles modeler une nouvelle forme de société, tournée vers le passé, certes, mais non nostalgique.

L'Allemand, dans le rapport qu’il a exposé à Rome, propose un parallélisme continu entre l'histoire européenne et japonaise : "[...] les luttes sauvages entre Taira et Minamoto, semblables à la guerre des Deux Roses, [...]" (18). Il souligne ainsi ce destin commun de l'histoire européenne et japonaise. (18), destin commun auquel il croyait obstinément. Tucci a été très impressionné par le caractère non fictionnel de la spéculation de Haushofer, par le fait que le géopolitologue a reconnu la primauté de Rome et de l'Italie en général, afin de construire une alliance avec le Japon qui ne soit pas seulement politique, mais spirituelle ; par exemple, lorsqu'il compare Kitabatake Chikafusa (1293-1354) à Dante (19), puisque tous deux ont été les auteurs de grands "poèmes politiques". Cela l'amène à déclarer que la Divine Comédie a trouvé une grande résonance dans le Jinnoshiki contemporain (神皇正統記, "Jinnō shōtōki", ca. 1339) de Kitabatake, qui peut raisonnablement être considéré comme un classique de la pensée politique japonaise, où les principes de légitimité de la lignée impériale ont été établis, conformément à la tradition shintoïste. Un tel texte, dans son ancrage de la "légitimité politique" à une matrice religieuse, ne pouvait qu'attirer l'intérêt des Allemands, qui en appréciaient les valeurs, ce qui aurait pu être une inspiration pour les nations occidentales non asservies à l'Economie et à la recherche de formules éthico-politiques sur lesquelles modeler une nouvelle forme de société, tournée vers le passé, certes, mais non nostalgique. Une synthèse inestimable sur la ‘’japonicitié’’

Une synthèse inestimable sur la ‘’japonicitié’’ Il convient maintenant de proposer une petite clarification linguistique. En transcrivant le terme chinois susmentionné, Haushofer utilise étrangement, pour un Allemand, le système de transcription de l'EFEO (École française d'Extrême-Orient), au lieu du Wade-Giles alors plus populaire. Dans ce système de romanisation phonétique, "Ko" correspond au "Ge" de l'actuel pinyin, le mot devient donc "gémìng" (革命, "revolt/revolt"), terme également utilisé pour désigner la grande révolution culturelle maoïste (文化大革命, "Wénhuà dà gémìng"). Cela nous fait comprendre comment certains concepts enracinés en Chine depuis l'Antiquité ont survécu aux bouleversements politiques les plus dramatiques. Dans l'Empire du Milieu, en effet, lorsqu'une famine ou toute autre catastrophe naturelle se produisait, l'Empereur lui-même était responsable, puisqu'il avait perdu la bienveillance des Déités, et le Peuple se sentait autorisé à se rebeller contre lui et à le déposer de force. Cela explique l'alternance de tant de dynasties dans le pays. Tout le contraire, comme on l'a dit, pour le Japon traditionnel, où l'empereur est un Dieu intouchable.

Il convient maintenant de proposer une petite clarification linguistique. En transcrivant le terme chinois susmentionné, Haushofer utilise étrangement, pour un Allemand, le système de transcription de l'EFEO (École française d'Extrême-Orient), au lieu du Wade-Giles alors plus populaire. Dans ce système de romanisation phonétique, "Ko" correspond au "Ge" de l'actuel pinyin, le mot devient donc "gémìng" (革命, "revolt/revolt"), terme également utilisé pour désigner la grande révolution culturelle maoïste (文化大革命, "Wénhuà dà gémìng"). Cela nous fait comprendre comment certains concepts enracinés en Chine depuis l'Antiquité ont survécu aux bouleversements politiques les plus dramatiques. Dans l'Empire du Milieu, en effet, lorsqu'une famine ou toute autre catastrophe naturelle se produisait, l'Empereur lui-même était responsable, puisqu'il avait perdu la bienveillance des Déités, et le Peuple se sentait autorisé à se rebeller contre lui et à le déposer de force. Cela explique l'alternance de tant de dynasties dans le pays. Tout le contraire, comme on l'a dit, pour le Japon traditionnel, où l'empereur est un Dieu intouchable.

Quoi qu'il en soit, il faut préciser que le penseur allemand n'a pas simplement posé les prémisses d'une géopolitique qui n'était pas eurocentrique, c'est-à-dire encline à protéger les intérêts des puissances occidentales oppressives habituelles. Haushofer est allé beaucoup plus loin, à l'autre bout du globe, jusqu'au lointain Japon, en essayant de saisir des éléments structurels de valeur universelle. Comprenant que, pour déchiffrer ce Peuple, il est nécessaire de ne jamais séparer le politique du sacré, il nous apparaît comme le meilleur yamatologue (japonologue) du 20ème siècle, avec notre Père Mario Marega - missionnaire salésien très cultivé, auteur d'une indispensable traduction de Kojiki, publiée par Laterza en 1938 - et Fosco Maraini. Il faut également rappeler le principe très clair de Haushofer selon lequel le gouvernement du territoire doit être garanti par une appartenance éthico-politique dont le souverain est le symbole vivant, représentant la "dimension interne" : le kokoro (心) (21), son "cœur". Et cette frontière spirituelle - pas seulement dans le cas du Japon - doit être défendue à tout prix. Ce n'est pas pour rien qu'il utilise à plusieurs reprises le terme "marca", qui à l'époque des Carolingiens indiquait un territoire frontalier.

Quoi qu'il en soit, il faut préciser que le penseur allemand n'a pas simplement posé les prémisses d'une géopolitique qui n'était pas eurocentrique, c'est-à-dire encline à protéger les intérêts des puissances occidentales oppressives habituelles. Haushofer est allé beaucoup plus loin, à l'autre bout du globe, jusqu'au lointain Japon, en essayant de saisir des éléments structurels de valeur universelle. Comprenant que, pour déchiffrer ce Peuple, il est nécessaire de ne jamais séparer le politique du sacré, il nous apparaît comme le meilleur yamatologue (japonologue) du 20ème siècle, avec notre Père Mario Marega - missionnaire salésien très cultivé, auteur d'une indispensable traduction de Kojiki, publiée par Laterza en 1938 - et Fosco Maraini. Il faut également rappeler le principe très clair de Haushofer selon lequel le gouvernement du territoire doit être garanti par une appartenance éthico-politique dont le souverain est le symbole vivant, représentant la "dimension interne" : le kokoro (心) (21), son "cœur". Et cette frontière spirituelle - pas seulement dans le cas du Japon - doit être défendue à tout prix. Ce n'est pas pour rien qu'il utilise à plusieurs reprises le terme "marca", qui à l'époque des Carolingiens indiquait un territoire frontalier.

Le concept nodal de Lebensraum ("Espace de vie"), linteau de toute la géopolitique haushoférienne, ne pouvait pas manquer dans ce document. Cependant, dans l'exemple singulier du Japon, il est représenté par la mer, qui permet l'isolement, par lequel s'est développé le facteur ethnique du Japon spécifique : "Le simple fait que, contrairement à ce qui s'est passé pour toutes les autres émergences nationales, les migrations des peuples n'ont pas exercé d'influence sur l’émergence nationale japonaise : celle-ci est née indépendamment des migrations des tribus et suffirait à caractériser de façon absolue la genèse de l'État japonais" (14). Nous comprenons donc que l'expansionnisme voulu par le gouvernement militaire, et qui a conduit le pays à la guerre contre la Grande-Bretagne et les États-Unis, était à sa manière une trahison de cette doctrine que le scientifique allemand avait donnée aux nombreux officiers japonais qui furent ses étudiants : jeter une influence sur l'Asie pourrait également être une solution équitable pour le Japon, à condition toutefois de ne pas affaiblir ce chapelet d'identité et d'autodéfense qui, des siècles auparavant, à deux reprises, avec la force du vent et de l'eau, avait sauvé l'archipel de l'invasion mongole. Dit d'une manière plus "technico-militaire", l'armée japonaise était dispersée dans tout l'Extrême-Orient, laissant, après le désastre de Midway (3-6 juin 1942), le Peuple chez lui, pratiquement sans défense.

Le concept nodal de Lebensraum ("Espace de vie"), linteau de toute la géopolitique haushoférienne, ne pouvait pas manquer dans ce document. Cependant, dans l'exemple singulier du Japon, il est représenté par la mer, qui permet l'isolement, par lequel s'est développé le facteur ethnique du Japon spécifique : "Le simple fait que, contrairement à ce qui s'est passé pour toutes les autres émergences nationales, les migrations des peuples n'ont pas exercé d'influence sur l’émergence nationale japonaise : celle-ci est née indépendamment des migrations des tribus et suffirait à caractériser de façon absolue la genèse de l'État japonais" (14). Nous comprenons donc que l'expansionnisme voulu par le gouvernement militaire, et qui a conduit le pays à la guerre contre la Grande-Bretagne et les États-Unis, était à sa manière une trahison de cette doctrine que le scientifique allemand avait donnée aux nombreux officiers japonais qui furent ses étudiants : jeter une influence sur l'Asie pourrait également être une solution équitable pour le Japon, à condition toutefois de ne pas affaiblir ce chapelet d'identité et d'autodéfense qui, des siècles auparavant, à deux reprises, avec la force du vent et de l'eau, avait sauvé l'archipel de l'invasion mongole. Dit d'une manière plus "technico-militaire", l'armée japonaise était dispersée dans tout l'Extrême-Orient, laissant, après le désastre de Midway (3-6 juin 1942), le Peuple chez lui, pratiquement sans défense.

Mishima, dans la lignée de la tradition japonaise, a conçu l'existence comme un équilibre entre des hypothèses opposées, la liberté et la répression, la vie et la mort. La vie est mieux contemplée dans l'ombre de la mort ; sous la teinte mortelle, le vital est lumineux, rayonnant. Embrasser l'existence implique d'embrasser à la fois la vie et la mort, et de cette fusion découlera la vitalité. La vie doit nécessairement être équilibrée avec la mort, sinon la vie sera informe, grotesque, désordonnée.

Mishima, dans la lignée de la tradition japonaise, a conçu l'existence comme un équilibre entre des hypothèses opposées, la liberté et la répression, la vie et la mort. La vie est mieux contemplée dans l'ombre de la mort ; sous la teinte mortelle, le vital est lumineux, rayonnant. Embrasser l'existence implique d'embrasser à la fois la vie et la mort, et de cette fusion découlera la vitalité. La vie doit nécessairement être équilibrée avec la mort, sinon la vie sera informe, grotesque, désordonnée.

Assumant une « étiquette » de « réactionnaire », Yukio Mishima fonde en 1968 la Société du Bouclier. Dès février 1969, la nouvelle structure qui s’entraîne avec les unités militaires japonaises, dispose d’un « manifeste contre-révolutionnaire », le Hankakumei Sengen. Sa raison d’être ? Protéger l’Empereur (le tenno), le Japon et la culture d’un péril subversif communiste immédiat. Par-delà la disparition de l’article 9, il conteste le renoncement à l’été 1945 par le tenno lui-même de son caractère divin. Il critique la constitution libérale parlementaire d’émanation étatsunienne. Il n’accepte pas que la nation japonaise devienne un pays de second rang. Yukio Mishima s’inscrit ainsi dans des précédents héroïques comme le soulèvement de la Porte Sakurada en 1860 quand des samouraï scandalisés par les accords signés avec les « Barbares » étrangers éliminent un haut-dignitaire du gouvernement shogunal, la révolte de la Ligue du Vent Divin (Shimpûren) de 1876 ou, plus récemment, le putsch du 26 février 1936. Ce jour-là, la faction de la voie impériale (Kodoha), un courant politico-mystique au sein de l’armée impériale influencé par les écrits d’Ikki Kita (1883 – 1937), assassine les ministres des Finances et de la Justice ainsi que l’inspecteur général de l’Éducation militaire. Si la garnison de Tokyo et une partie de l’état-major se sentent proches des thèses développées par le Kodoha, la marine impériale, plus proche des rivaux de la Faction de contrôle (ou Toseiha), fait pression sur la rébellion. Les troupes loyalistes rétablissent finalement la légalité. Yukio Mishima tire de ces journées tragiques son récit Patriotisme.

Assumant une « étiquette » de « réactionnaire », Yukio Mishima fonde en 1968 la Société du Bouclier. Dès février 1969, la nouvelle structure qui s’entraîne avec les unités militaires japonaises, dispose d’un « manifeste contre-révolutionnaire », le Hankakumei Sengen. Sa raison d’être ? Protéger l’Empereur (le tenno), le Japon et la culture d’un péril subversif communiste immédiat. Par-delà la disparition de l’article 9, il conteste le renoncement à l’été 1945 par le tenno lui-même de son caractère divin. Il critique la constitution libérale parlementaire d’émanation étatsunienne. Il n’accepte pas que la nation japonaise devienne un pays de second rang. Yukio Mishima s’inscrit ainsi dans des précédents héroïques comme le soulèvement de la Porte Sakurada en 1860 quand des samouraï scandalisés par les accords signés avec les « Barbares » étrangers éliminent un haut-dignitaire du gouvernement shogunal, la révolte de la Ligue du Vent Divin (Shimpûren) de 1876 ou, plus récemment, le putsch du 26 février 1936. Ce jour-là, la faction de la voie impériale (Kodoha), un courant politico-mystique au sein de l’armée impériale influencé par les écrits d’Ikki Kita (1883 – 1937), assassine les ministres des Finances et de la Justice ainsi que l’inspecteur général de l’Éducation militaire. Si la garnison de Tokyo et une partie de l’état-major se sentent proches des thèses développées par le Kodoha, la marine impériale, plus proche des rivaux de la Faction de contrôle (ou Toseiha), fait pression sur la rébellion. Les troupes loyalistes rétablissent finalement la légalité. Yukio Mishima tire de ces journées tragiques son récit Patriotisme.

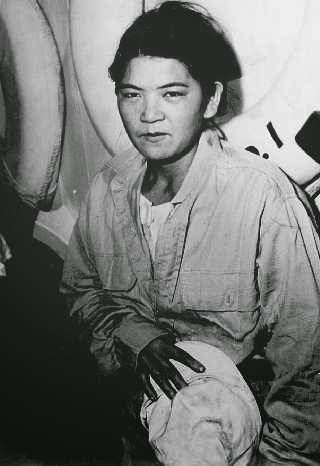

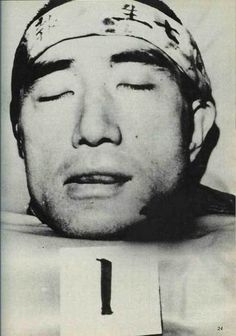

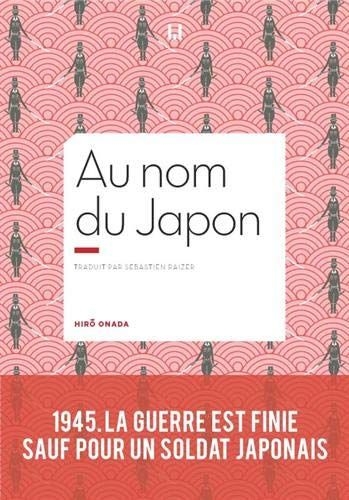

Jeune lieutenant à la fin du conflit, Hirô Onoda rejoint l’île occidentale de Lubang aux Philippines. Instruit auparavant dans une école de guérilla à Futamata, il reçoit des ordres explicites : 1) ne jamais se donner la mort, 2) désorganiser au mieux l’arrière des lignes ennemies une fois que l’armée impériale se sera retirée, 3) tout observer dans l’attente d’un prochain débarquement japonais.

Jeune lieutenant à la fin du conflit, Hirô Onoda rejoint l’île occidentale de Lubang aux Philippines. Instruit auparavant dans une école de guérilla à Futamata, il reçoit des ordres explicites : 1) ne jamais se donner la mort, 2) désorganiser au mieux l’arrière des lignes ennemies une fois que l’armée impériale se sera retirée, 3) tout observer dans l’attente d’un prochain débarquement japonais. Modèle d’abnégation patriotique totale, bel exemple d’impersonnalité active, Hirô Onoda est alors certain qu’en cas d’invasion du Japon, « les femmes et les enfants se battraient avec des bâtons en bambou, tuant un maximum de soldats avant de mourir. En temps de guerre, les journaux martelaient cette résolution avec les mots les plus forts possibles : “ Combattez jusqu’au dernier souffle ! ”, “ Il faut protéger l’Empire à tout prix ! ”, “ Cent millions de morts pour le Japon ! ” (pp. 177 – 178) ». Ce n’est que le 9 mars 1974 que le lieutenant Onoda arrête sa guerre dans des circonstances qu’il reviendra au lecteur de découvrir.

Modèle d’abnégation patriotique totale, bel exemple d’impersonnalité active, Hirô Onoda est alors certain qu’en cas d’invasion du Japon, « les femmes et les enfants se battraient avec des bâtons en bambou, tuant un maximum de soldats avant de mourir. En temps de guerre, les journaux martelaient cette résolution avec les mots les plus forts possibles : “ Combattez jusqu’au dernier souffle ! ”, “ Il faut protéger l’Empire à tout prix ! ”, “ Cent millions de morts pour le Japon ! ” (pp. 177 – 178) ». Ce n’est que le 9 mars 1974 que le lieutenant Onoda arrête sa guerre dans des circonstances qu’il reviendra au lecteur de découvrir.

Dr. Joyce maintained that “Mishima, of course, never explored the Emperor’s role in World War II in any depth, and his chief fixation appears solely to have been the decision of the Emperor to accede to Allied demands and ‘become human.’” This is a baffling statement which again simply betrays Dr. Joyce’s lack of knowledge. Besides rightfully decrying the Showa Emperor’s self-demotion to “become human” from his traditional status of “Arahitogami” (god in human form or demigod), Mishima also critically examined the Emperor’s role in politics before, during, and after the war, which revealed that what Mishima essentially venerated was not the individual Tennō but the Kōtō (the unique and time-honored Japanese monarchical system).

Dr. Joyce maintained that “Mishima, of course, never explored the Emperor’s role in World War II in any depth, and his chief fixation appears solely to have been the decision of the Emperor to accede to Allied demands and ‘become human.’” This is a baffling statement which again simply betrays Dr. Joyce’s lack of knowledge. Besides rightfully decrying the Showa Emperor’s self-demotion to “become human” from his traditional status of “Arahitogami” (god in human form or demigod), Mishima also critically examined the Emperor’s role in politics before, during, and after the war, which revealed that what Mishima essentially venerated was not the individual Tennō but the Kōtō (the unique and time-honored Japanese monarchical system).