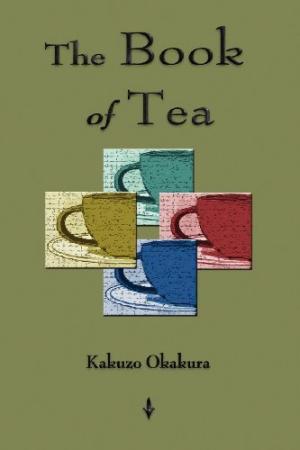

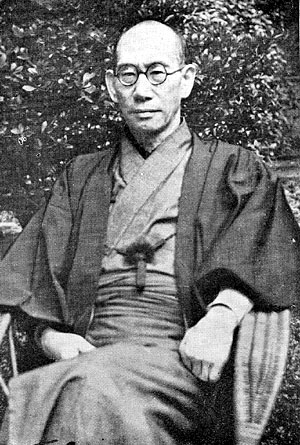

Despite his claim that the cultural crisis brought on by worldwide technological advancement could not be solved by a wholesale adoption of Eastern traditions such as Zen Buddhism, Martin Heidegger engaged in many conversations with… Japanese scholars throughout his philosophical career. His first and perhaps most significant encounter with the East took place as early as 1919, eight years before the publication of Being and Time. After having attended Heidegger’s 1918 lectures, one of his Japanese students, Tomonobu Imamichi, introduced Heidegger to the concept of “being in the world.” In The Book of Tea (1906), Tomonobu’s teacher, Okakura Kakuzo had used these words to describe an aspect of Zhuangzi’s spiritual vision.

Despite his claim that the cultural crisis brought on by worldwide technological advancement could not be solved by a wholesale adoption of Eastern traditions such as Zen Buddhism, Martin Heidegger engaged in many conversations with… Japanese scholars throughout his philosophical career. His first and perhaps most significant encounter with the East took place as early as 1919, eight years before the publication of Being and Time. After having attended Heidegger’s 1918 lectures, one of his Japanese students, Tomonobu Imamichi, introduced Heidegger to the concept of “being in the world.” In The Book of Tea (1906), Tomonobu’s teacher, Okakura Kakuzo had used these words to describe an aspect of Zhuangzi’s spiritual vision.

The Book of Tea uses the tea ceremony to explore the wabi-sabi aesthetic experience cultivated in Japanese Zen arts and crafts. The early German translation of The Book of Tea uses the words das-in-der-Welt-sein, which, via Imamichi, found their way into the heart and soul of Heidegger’s 1927 magnum opus. Interestingly, Heidegger’s philosophical career not only begins under Japanese influence, it also ends with it. One of the essays in his last work On the Way to Language is “A Dialogue on Language” between “a Japanese and an inquirer” who remain significantly unnamed…

The Book of Tea uses the tea ceremony to explore the wabi-sabi aesthetic experience cultivated in Japanese Zen arts and crafts. The early German translation of The Book of Tea uses the words das-in-der-Welt-sein, which, via Imamichi, found their way into the heart and soul of Heidegger’s 1927 magnum opus. Interestingly, Heidegger’s philosophical career not only begins under Japanese influence, it also ends with it. One of the essays in his last work On the Way to Language is “A Dialogue on Language” between “a Japanese and an inquirer” who remain significantly unnamed…

In his “Introduction to Heideggerian Existentialism”, Leo Strauss makes much of Heidegger’s ‘Eastern’ response to the crisis of world-enframing technology in the absence of a genuine global society. Strauss observes that modern technology is forcing the material conditions of a World Society upon us, without a common world culture as its basis. It is the unification of mankind on the basis of the lowest common denominator. This leads to “lonely crowds” suffering from a pervasive sense of alienation and anomie. Furthermore, Strauss recognizes that no genuine culture in the world has ever arisen without a religious basis, without addressing man’s need for something noble and great beyond himself. So the world society, being wrought largely as a consequence of apparently valueless technological forces, is ironically one in need, not merely of a universal ethics, but of one world religion. The world religion must emerge out of the deepest reflection on the crisis of cultural relativism, and on the essence of the technological forces bringing it about:

[Heidegger] called it the “night of the world.” It means indeed, as Marx had predicted, the victory of an ever more completely urbanized, ever more completely technological West over the whole planet – complete leveling and uniformity… unity of the human race on the lowest level, complete emptiness of life… How can there be hope? Fundamentally, because there is something in man which cannot be satisfied by the world society: the desire for the genuine, for the noble, for the great. The desire has expressed itself in man’s ideals, but all previous ideals have proved to be related to societies which were not world societies. The old ideals will not enable man to overcome the power, to weaken the power, of technology. We may also say: a world society can be human only if there is a world culture, a culture genuinely uniting all men. But there never has been a high culture without a religious basis: the world society can be human only if all men are genuinely united by a world religion.

Explicating Heidegger, Strauss explains that in order for it to be possible to overcome technology, which is not at all the same as rejecting it, there must be a sphere of thought or contemplation beyond the rationalism developed by the Greeks and forwarded in Western science and technology. This must be an understanding of the world from behind or beneath the will to mathematize all beings with a view to instrumental manipulation of them on demand (bestand). It must understand the difference between Being and beings, and that Being is no-thing that can be mastered. The to be which is always as present at hand, is taken by Rationalism as the standard of being – that which really is, is always present, available, accessible. Instead, Strauss thinks that: “a more adequate understanding of being is intimated by the assertion that to be means to be elusive or to be a mystery.” Strauss claims that “this is the Eastern understanding of Being” and he adds that: “We can hope beyond technological world society, we can hope for a genuine world society, only if we become capable of learning from the East… Heidegger is the only man who has an inkling of the dimensions of the problem of a world society.”

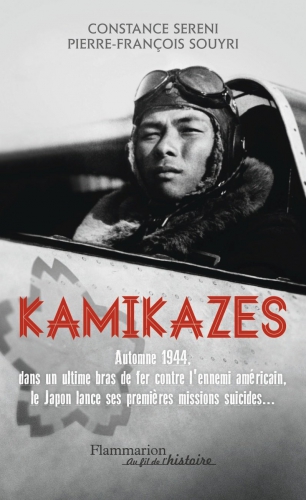

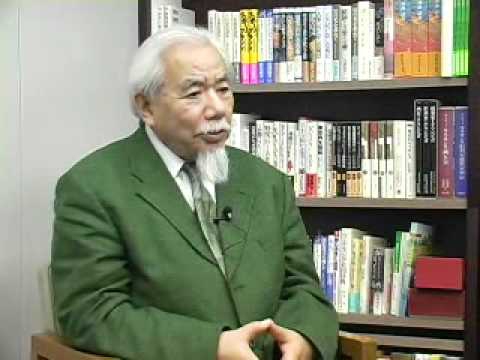

…The thinkers of the Kyoto School of Philosophy were in favor of the war and have been collectively referred to as the “philosophers of nothingness”. Some of them had a constructive vision of how the Buddhist understanding of the void could complement the techno-scientific thinking of the West in order to bring about a new global civilization. Key figures among them, such as Nishida Kitaro, were students of Heidegger as early as the 1920s, and like Heidegger they saw the world war as the means to bring about a global culture that would ground techno-scientific development in a spirituality transcending insular and traditional values.

…The thinkers of the Kyoto School of Philosophy were in favor of the war and have been collectively referred to as the “philosophers of nothingness”. Some of them had a constructive vision of how the Buddhist understanding of the void could complement the techno-scientific thinking of the West in order to bring about a new global civilization. Key figures among them, such as Nishida Kitaro, were students of Heidegger as early as the 1920s, and like Heidegger they saw the world war as the means to bring about a global culture that would ground techno-scientific development in a spirituality transcending insular and traditional values.

Remember that the Indian caste system that Nietzsche so admired, and that was based on regimented and hierarchically stratified class divisions, was a function of the Aryan conquest of the native Dravidian population of India. This origin is reflected in the Sanskrit name for the “caste” of the caste system, varna, which literally means “color” so that it was once a color-coding system. The four classes were: the Brahmins – the Vedic priests or scholars (including those who engaged in various proto-scientific practices); the Kshatriyas – the caste of knightly warriors, including feudal lords as chief amongst them; the Vaishyas – the business class, including both farmers and various types of merchants; and the Shudras – menial laborers, usually involved in undignified or hard labor. Finally, there were also “outcaste untouchables” that were relegated to an inhumanly low status. “Prince” Siddhartha Gotama belonged to the Kshatriya class.

The Buddha was a light-skinned blue eyed Aryan whose father was a feudal lord and who was expected to become a knight. In his late writings, Nishida Kitaro explains how it is that “Indian culture”, from which Japan inherited Buddhism (including the symbol of the swastika that is ubiquitous at Japanese temples) and which shares the Aryan or ‘Indo-European’ ethnic roots of European culture, “has evolved as an opposite pole to modern European culture… and may thereby be able to contribute to a global modern culture from its own vantage point.” What is the “global modern culture” that Nishida envisions?

Well, he certainly views it as having a religious basis and he thinks that the world war during which he is writing is a means to achieving it: “And does not the spirit of modern times seek a religion of infinite compassion rather than that of the Lord of ten thousand hosts? It demands reflection in the spirit of Buddhist compassion. This is the spirit which says that the present world war must be for the sake of negating world wars, for the sake of eternal peace.” In every true religion the divine is an absolute love that embraces its opposite, to the extent of even becoming Satan, and this is the meaning of the concept of upaya or shrewdly bringing to bear “skillful means” in Mahayana Buddhism so that “the miracles” of “this world may be said to be… the Buddha’s expedient means.” This all-embracing character of the divine, as that which encompasses what one would take to be its opposite, “is the basic reason why we are beings who can be compassionate to others and who can experience the compassion of others. Compassion always signifies that opposites are one in the dynamic reciprocity of their own contradictory identity.”

A God who is the Lord (Dominus) in the sense of an ultimately transcendent substance cannot be a truly creative God. Creation ex nihilo would be both arbitrary and superfluous; it must be out of love that God or Buddha creatively manifests the world from out of its own self-negation. Nishida believes that the school of Prajnaparamita thought in Mahayana Buddhism, established by Nagarjuna, has a deeper and more adequate understanding of this than pantheistic Western thinkers of dialectical synthesis, such as the Hegelians, who remain within the realm of reason even in their negative theologies. Nishida nevertheless refers to his ontology of the absolute’s self-expression and transformation as “Trinitarian” and compares it to Neo-Platonic thought.

However, Neo-Platonism and all pagan western thought falls short insofar as it fails to see Satan or “absolute evil” as an aspect of God. He adds: “The absolute God must include absolute negation within himself, and must be the God who descends into ultimate evil. The highest form must be one that transforms the lowest matter into itself. Absolute agape must reach even to the absolutely evil man. This is again the paradox of God: God is hidden even within the heart of the absolutely evil man. A God who merely judges the good and the bad is not truly absolute.” In passages such as these we see that Shunyata (in Sanskrit, Mu in Japanese) is not the Nothing of Descartes at all. Quite to the contrary of serving as an entirely distinct polar opposite of a Perfect Being that would exonerate the latter from being the source of any imperfection, this Nothingness is an inner dynamic tension within Being – as expressed in the spectral incompleteness and interdependent interpenetration of all beings. The battle between God and Nothingness in the heart of man, the “dynamic equilibrium” between “is” and “is not”, may be paradoxical but it is also the existential ‘ground’ of the volitional person. “Radical evil” lies ineradicably at the root of our freedom. We are always already “both satanic and divine.” Nishida claims that the Buddha – or any other conception of divinity – outside of one’s own existential potentiality is not the true Buddha:

Only in this existential experience of religious remorse does the self encounter what Rudolf Otto calls the numinous. Subjectively speaking, the encounter is a deep reflection upon the existential depths of the self itself; and as the Buddhists say, it means to see our essential nature, to see the true self. In Buddhism, this seeing means, not to see Buddha objectively outside, but to see into the bottomless depths of one’s own soul. If we see God externally, it is merely magic. …Illusion is the fountainhead of all evil. Illusion arises when we conceive of the objectified self as the true self. The source of illusion is in seeing the self in terms of object logic. It is for this reason that Mahayana Buddhism says that we are saved through enlightenment. But this enlightenment is generally misunderstood. For it does not mean to see anything objectively… It is rather an ultimate seeing of the bottomless nothingness of the self that is simultaneously a seeing of the fountainhead of sin and evil.

In this Zen injunction to kill any conception of a Buddha outside oneself, Nishida does not deny the cycle of birth and death or samsara as an empirical or phenomenological fact, he simply insists that the truly religious consciousness is one that has recognized the identity of samsara and nirvana. On his terms, and according to the sages of the esoteric Buddhist tradition, nirvana does not mean to attain some state distinct from and after samsara but to recognize that in every moment of the cycle of reincarnation the perfection beyond the impurity of karma is already present. This does not mean that the self “transcends its own historical actuality – it does not transcend its own karma – but rather that it realizes the bottomless bottom of its own karma.”

This relatively late Mahayanist view is anathema to the teaching of Siddhartha Gotama and the early Indian Buddhism founded on it. According to the Buddha Dharma, just as there are physical, biological, and psychological laws operative in the cosmos, there is also an ethical law. The law of karma is a lawful relationship between one’s actions, including verbal and unspoken mental acts that express one’s volition (cetana), and both the realm within which one is reborn as well as the conditions of life that one experiences within this realm. The ethical quality of one’s volition is supposed to resonate with the qualitative character of a certain realm of existence, and to tune into this realm, as it were, as a consequence of being on the same wavelength. Within these more general parameters what one experiences within a given realm of existence is conditioned by one’s actions both within the present life and in past lives. The fundamental presupposition here is that even if an action or intention does not appear to bear fruit (phala) presently, it reverberates in ways that one may remain unconscious of until it finally yields some tangible results (vipaka) – possibly later in one’s present life, but perhaps not until a future life.

While psychological research in the wake of the coming spectral revolution in Science might validate certain classes of phenomena associated with Buddhism as genuine natural phenomena, it is likely to reveal significant Buddhist misunderstandings of these very same phenomena and to profoundly challenge Buddhist codes of ethics. This is the case with the Reincarnation research of the late Dr. Ian Stevenson… What would disturb Buddhists most about Stevenson’s apparent validation of one of the central tenants of their religion is that the ethical idea of karma is untenable in light of his scientific research into the reality of Reincarnation as a natural phenomenon. What Stevenson found is that a person’s strong psychic impression of localized bodily injury at the time of a violent death or terrible accident, could affect fetal development of the body to be subsequently inhabited by that person to produce a birthmark or birth defect corresponding to the site of injury and even the shape or type of injury. In other words there are many cases of the following type: an innocent person is attacked and has his arm hacked off by a murderer and while the victim is reborn with that arm badly deformed, the murderer not only gets away scot free in his present incarnation, he also does not suffer any apparent ill effects in his subsequent incarnation.

Nirvana is the goal of the path, the aim of the Buddha Dharma. Yet, it is the most obscure element of Gotama’s teachings and, unlike karma, meditation, and the moral disciplines, it is one of the ideas most unique to his understanding of the Dharma as compared to the various pre-Buddhist forms of Sanatana Dharma (aka. ‘Hinduism). It is referred to at times as an element or a state, a state of supreme bliss, and yet it is supposed to be beyond any conditioned state, whether painful or even pleasurable. At times Siddhartha discusses Nirvana as if it were attainable amidst the present life and at other times it seems like a total annihilation that a perfectly enlightened person can pass into upon the disintegration of what will be his final body. What, then, is the difference between this annihilation and the so-called “annihilationism” that is one of the wrong views most destructive of an ethical life? Is the Buddha Dharma, in its original form, essentially a grand doctrine of suicide? Does it opt out of actual suicide because it will not do any good, since the underlying tendencies of the psyche are still active and will reorganize around a new physical aggregate, so that suicide can only be truly successful by unbinding the threads of this psyche – by disintegrating the soul?

Nirvana means “snuffing out” or “blowing out”, as in putting out a flame or fire. Orthodox Buddhists of the Theravada tradition most directly descended from the teachings of Gotama suggest that the answer to the perplexing question as to who attains Nirvana and where he attains it, namely as to whether a Buddha or arahant exists in Nirvana after death or is annihilated and passes into nothingness, can be simply answered by saying that the perfectly enlightened person simply “goes out” or is “put out.” He was a flame burning with the fire of life, but this fire of ceaseless suffering has been put out. Phew! Can there be a more pessimistic and nihilistic view of life? At least the man who actually commits suicide affirms a life that would be worth living by comparison to his own, which he judges intolerable only as compared to some ideal. He would also be affirming a sense of history wherein the future can be meaningfully different from any past epoch, an understanding of time that warrants a historical struggle – even if not one that he can personally bear to participate in here and now. It is above all in Japan where this early Buddhist nihilism gave way to the world-historical ethos of the fiery forge.

Nishida draws a distinction between physical, biological, and historical life. The teleological irreversibility of time in the course of organic development is key to his distinction between the first two. Whereas the world of biological life forms remains partially spatial and material, in the human world time negates space and the spatialized chronological ‘time’ relevant to inorganic physics. As Nishida puts it: “We can even say that there is no death for a merely biological being. For death entails that a self enter into eternal nothingness. It is because a self enters into eternal nothingness that it is historically irrepeatable, unique, and individual.” Only in the face of this “eternal death” qua nothingness is genuine individuation possible and only the real individual becomes agitated by the religious question. A being who carries out its moral duty for duty’s sake, in other words out of adherence to what Kant frames as the categorical imperative, would have no individuality; religion can have no meaning for such an abstract subject without any concrete will. Groundless nothingness (Shunyata) is the unstable and ghostly horizon of one’s finite existence, and existential awareness of this ultimate and inescapable negation of one’s self is not a merely noetic reflection.

Nishida approvingly attributes to Fyodor Dostoyevsky the “standpoint of freedom” which holds that: “There is nothing at all that determines the self at the very ground of the self.” From the vantage point of his own time, Nishida sees the spirit of Dostoyevsky as the closest point of contact between Japanese spirituality and the West. He admonishes the Japanese for having remained too insular and that the spiritual sense for the ordinary and everyday that Japan shares with Dostoyevsky has hitherto been too superficial. “At this juncture,” he says, “it must come to possess an acute Dostoievskian spirit in an eschatological sense, as the Japanese spirit participating in world history.” Nishida hopes that “in this way” the hybridized Japanese civilization “can become a point of departure for a new global culture.” Nishida sees the way that the Yahweh “folk religion of the Jewish race” evolved into a world religion, and one that served as the basis for a medieval European culture that he clearly admires, as a model for a potential globalizing evolution of Japanese tradition. The “scientific” secularization characteristic of modern Western civilization, wherein “old worlds lose their specific traditions”, is a necessary phase in the formation of “a global humanity.” It is, in a dialectical sense, a negatively determinative moment in “the world’s transformation.” However, it must be recognized that “science is also a form of culture” and that “the world of science may also be said to be religious.” The failure to recognize this has been chiefly responsible for the fact that “such a thing as the decline and fall of the West has been proclaimed.”

Dostoyevsky diagnosed the causes of this decline perspicaciously in Notes From Underground (1864), which is widely considered the first existentialist novel. It is a response to the situation of the Cartesian ego, which… is sadistically enmeshed in murderous machinery over which he takes himself to have no control. The underground man is crippled by his hyperconsciousness. He is unlike the common man of action insofar as he can trace all effects back to ever receding causes such that, for example, he is incapable of mistaking vengeance for justice, since the would-be target of a retributive act is not ultimately responsible for it. He is also unlike people who are cruel only out of stupidity, because he cannot even stop at the egoistic passions that they take to be primary causes. Under a more intensely rational scrutiny, comprehending these passions also dissolves them as any solid basis for action. The underground man challenges the claim that other materialistic rationalists make, to the effect that a person cannot but act in such a way as is to his advantage.

Dostoevsky asks us to suppose that we were able to arrive at a formulation of the laws of nature, including biological and psychological laws, so precise that we could calculate, in every case, what a man will do by knowing what is at that moment to his advantage – not as an individual – but as an organism that microcosmically expresses the survivalist egoism of Nature. A man who became aware of this calculation would spitefully do something else, anything else, just to prove that he was not “a piano key” or an “organ pedal” whose thoughts and passions could in principle be encompassed by a formula, tabulated, and predicted according to statistical probability. Dostoevsky equates the sum total of any comprehensive formula for the laws of nature, of the kind that physicists today are still searching for under the rubric of a theory of everything, with “an endlessly recurring zero” because it nullifies meaningful action.

Dostoevsky asks us to suppose that we were able to arrive at a formulation of the laws of nature, including biological and psychological laws, so precise that we could calculate, in every case, what a man will do by knowing what is at that moment to his advantage – not as an individual – but as an organism that microcosmically expresses the survivalist egoism of Nature. A man who became aware of this calculation would spitefully do something else, anything else, just to prove that he was not “a piano key” or an “organ pedal” whose thoughts and passions could in principle be encompassed by a formula, tabulated, and predicted according to statistical probability. Dostoevsky equates the sum total of any comprehensive formula for the laws of nature, of the kind that physicists today are still searching for under the rubric of a theory of everything, with “an endlessly recurring zero” because it nullifies meaningful action.

The underground man would act contrary to his advantage, he would humiliatingly sacrifice himself to others, to be beaten and brutalized, to be impoverished through impossible generosity, and in every other way to fail and suffer in life just so as to demonstrate that life “is not simply extracting square roots.” On the one hand, he knows that “two times two makes four”, in other words the laws of nature cannot be changed and so “there is nothing left for you to do or to understand.” On the other hand, he has a painful awareness that “Consciousness… is infinitely superior to two times two makes four.” The underground man decides that “if you stick to consciousness, even though you attain the same result, you can at least flog yourself at times, and that will, at any rate, liven you up. It may be reactionary, but corporal punishment is still better than nothing.”

If “natural science and mathematics” were able to prove to him that even this reaction were predictable in accordance with some “mathematical formula”, he “would purposely go mad in order to be rid of reason” and moreover, he would try to hurl the whole of the world into an abyss of “chaos and darkness and curses.” This is what the underground man is referring to when he admits:

The long and the short of it is, gentlemen, that it is better to do nothing! Better conscious inertia! And so hurrah for underground! …But after all, even now I am lying! I am lying because I know myself as surely as two times two makes four, that it is not at all underground that is better, but something different, quite different, for which I long but which I cannot find! Damn underground!

Nishida is in search of what the underground man could not find as a cure to the mechanistic materialism dominating science under the Cartesian paradigm, but what he believed that Dostoevsky himself did find – albeit in an overly Judeo-Christian form that would benefit from a deconstructive encounter with the abyssal void of Zen.

Consciousness always consists of both an extending out over oneself as one’s world and a determination of oneself by that world, so that ‘subjectivity’ and ‘objectivity’ are abstractions of a creative world-forming process that one can intuit in the abyssal or groundless inner depths of the self prior to the interpretation of it as an ego. Nishida thinks “discovery in the scientific domain exemplifies the same point”, namely “seeing by becoming things and hearing by becoming things.” Nishida goes so far as to proclaim the ontological priority of the religious form of life over both scientific practice and social mores: “Both science and morality have their basis in the religious form of life.” Nishida later repeats this point with respect to scientific practice: “Active intuition is fundamental even for science. Science itself is grounded in the fact that we see by becoming things and hear by becoming things. Active intuition refers to that standpoint which Dogen characterizes as achieving enlightenment ‘by all things advancing.’” According to Nishida, the religious form of life is more fundamental than scientific cognition and the knowledge gained by means of it; the quest for scientific knowledge is a mode of the essentially religious character of our existence:

I hold that even scientific cognition is grounded in this structure of spirituality. Scientific knowledge cannot be grounded in the standpoint of the merely abstract conscious self. As I have said in another place, it rather derives from the standpoint of the embodied self’s own self-awareness. And therefore, as a fundamental fact of human life, the religious form of life is not the exclusive possession of special individuals. The religious mind is present in everyone. One who does not notice this cannot be a philosopher.

Nishida proclaims that, “A new cultural direction has now to be sought. A new mankind must be born… a new global culture.” Although Nishida admits that “the new age must primarily be scientific”, he sees a radicalization of the immanent view of divinity in Dostoyevsky and Russian mysticism in general through an encounter with Japanese Buddhism as playing a key role in defining “the religion of the future.” Yet the Buddhism that contributes to the formation of the religion of the new age, the religion of the global culture, must transcend the racial character of the Japanese: “From the perspective of present-day global history, it will perhaps be Buddhism that contributes to the formation of the new historical age. But if it too is only the conventional Buddhism of bygone days, it will merely be a relic of the past. The universal religions, insofar as they are already crystallized, have distinctive features corresponding to the times and places of the races that formed them.” It is inevitable that our ethos reflects a national character, but “the nation does not save our souls.” A true nation or civilization must be based on a world religion, and not the other way around.

The has been an excerpt from “Kill A Buddha On The Way,” the tenth chapter of Prometheus and Atlas (Arktos, 2016).

Right On Radio: #8 – The Promethean Destiny of Man with Jason Reza Jorjani

Prometheus and Atlas

In Prometheus & Atlas, Dr. Jorjani endeavors to deconstruct the nihilistic materialism and rootless rationalism of the modern West by showing how it was grounded on a dishonest suppression of the spectral and why it has a parasitic relationship with Abrahamic religious fundamentalism. Rejecting the marginalization of ESP and psychokinesis as “paranormal,” Prometheus & Atlas […]

Price: $36.50

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

La técnica de manufactura de fusiles fue transmitida a Sakai (en aquella época era el centro comercial “industrial” de Japón; se ubica al lado de Osaka). Los herreros especializados en producir las famosas espadas japonesas dominaban los secretos de cómo forjar el acero y dar tratamiento térmico más adecuado para aumentar la resistencia del metal. Tenían sus talleres alrededor de Sakai y empezaron a manufacturar los fusiles con mejores resultados que los originales en cuanto a la calidad de la puntería y resistencia al calor.

La técnica de manufactura de fusiles fue transmitida a Sakai (en aquella época era el centro comercial “industrial” de Japón; se ubica al lado de Osaka). Los herreros especializados en producir las famosas espadas japonesas dominaban los secretos de cómo forjar el acero y dar tratamiento térmico más adecuado para aumentar la resistencia del metal. Tenían sus talleres alrededor de Sakai y empezaron a manufacturar los fusiles con mejores resultados que los originales en cuanto a la calidad de la puntería y resistencia al calor.

El desarrollo tecnológico japonés ha conocido muchos saltos así, uno de los cuales, por lo general, se considera como la fecha de nacimiento de la moderna industria del hierro de Japón: el primero de diciembre de 1857 vio encenderse el primer fuego en el alto horno de Kamaishi, un horno de carbón que una vez más se basó en el libro único mencionado arriba. Claro está que, fuera de estos saltos, hubo fracasos, pero también éstos fueron importantes, ya que prepararon a los ingenieros japoneses para su siguiente salto. Esta característica (es decir, una serie de saltos pequeños) del desarrollo tecnológico japonés es extremadamente importante para los países actualmente en desarrollo. En la medida que los países emergentes pretenden alcanzar el mismo nivel tecnológico que los países desarrollados en un período de tiempo más corto, sus planes de desarrollo necesariamente deben diseñarse como una serie de saltos.

El desarrollo tecnológico japonés ha conocido muchos saltos así, uno de los cuales, por lo general, se considera como la fecha de nacimiento de la moderna industria del hierro de Japón: el primero de diciembre de 1857 vio encenderse el primer fuego en el alto horno de Kamaishi, un horno de carbón que una vez más se basó en el libro único mencionado arriba. Claro está que, fuera de estos saltos, hubo fracasos, pero también éstos fueron importantes, ya que prepararon a los ingenieros japoneses para su siguiente salto. Esta característica (es decir, una serie de saltos pequeños) del desarrollo tecnológico japonés es extremadamente importante para los países actualmente en desarrollo. En la medida que los países emergentes pretenden alcanzar el mismo nivel tecnológico que los países desarrollados en un período de tiempo más corto, sus planes de desarrollo necesariamente deben diseñarse como una serie de saltos.

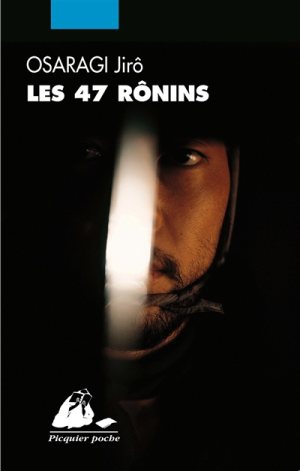

Auteur de fictions de cape et d’épées, de romans contemporains et de politique française (affaire dreyfus, boulangisme, Commune de Paris), l’écrivain est aussi connu pour son adaptation de l’histoire des 47 rônins. Osaragi Jirô publie cette histoire intitulée Akô Rôshi, sous forme de feuilletons paru dans le quotidien Tôkyô Nichinichi Shimbun en 1927. L’oeuvre sera réalisée pour le cinéma par Matsuda Sadatsugu en 1961.

Auteur de fictions de cape et d’épées, de romans contemporains et de politique française (affaire dreyfus, boulangisme, Commune de Paris), l’écrivain est aussi connu pour son adaptation de l’histoire des 47 rônins. Osaragi Jirô publie cette histoire intitulée Akô Rôshi, sous forme de feuilletons paru dans le quotidien Tôkyô Nichinichi Shimbun en 1927. L’oeuvre sera réalisée pour le cinéma par Matsuda Sadatsugu en 1961.

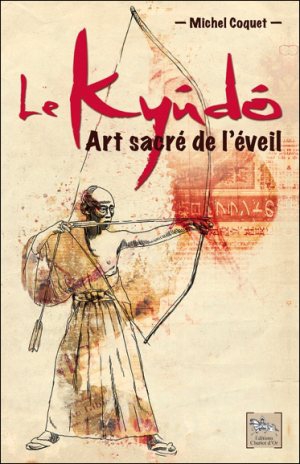

Loin du tape-à-l’oeil, Michel Coquet, né en 1944, a sincèrement voué sa vie à l’apprentissage des arts martiaux japonais (karaté, kenjutsu, ïaïdô, kyûdô, aïkidô, etc.), un apprentissage spirituel, car le budô, la voie du guerrier, ne peut être assimilée à un sport ou à une discipline olympique (tel le judô, et comme une partie de la fédération internationale de kendô le souhaiterait). Au Japon, une grande compagnie de sécurité sponsorise des lutteurs, des kendôkas, et les "matches de sumo" flairent bon le business... Actuellement le budô inclut de multiples disciplines, comme le judô, le kyudô, sumô, l’aïkidô, shôrinji kempô, naginata, jukendô : le guerrier de jadis est aujourd’hui éclaté en de multiples disciplines édulcorées. En somme, « budô » désigne les « arts martiaux » depuis l’ère Meiji (1868-1912). Avant cette date, on employait les termes de « bugei » et de « bujutsu », et même « l’ancienne voie du guerrier », ou « kobudô » est un néologisme. Bugei, ou l’ « art du guerrier » est une appellation caractéristique de la période d’Edô, où l’art militaire s’inspirait des autres domaines artistiques, comme le noh (pour les déplacements et les postures) ou la cérémonie du thé (les katas), ce qui manifestait une volonté d’esthétiser les techniques de combat.

Loin du tape-à-l’oeil, Michel Coquet, né en 1944, a sincèrement voué sa vie à l’apprentissage des arts martiaux japonais (karaté, kenjutsu, ïaïdô, kyûdô, aïkidô, etc.), un apprentissage spirituel, car le budô, la voie du guerrier, ne peut être assimilée à un sport ou à une discipline olympique (tel le judô, et comme une partie de la fédération internationale de kendô le souhaiterait). Au Japon, une grande compagnie de sécurité sponsorise des lutteurs, des kendôkas, et les "matches de sumo" flairent bon le business... Actuellement le budô inclut de multiples disciplines, comme le judô, le kyudô, sumô, l’aïkidô, shôrinji kempô, naginata, jukendô : le guerrier de jadis est aujourd’hui éclaté en de multiples disciplines édulcorées. En somme, « budô » désigne les « arts martiaux » depuis l’ère Meiji (1868-1912). Avant cette date, on employait les termes de « bugei » et de « bujutsu », et même « l’ancienne voie du guerrier », ou « kobudô » est un néologisme. Bugei, ou l’ « art du guerrier » est une appellation caractéristique de la période d’Edô, où l’art militaire s’inspirait des autres domaines artistiques, comme le noh (pour les déplacements et les postures) ou la cérémonie du thé (les katas), ce qui manifestait une volonté d’esthétiser les techniques de combat.

Lafcadio Hearn was born on the Ionian island of Santa Maura in either June or August 1850 and died in Okubo, Japan in 1904. His father was an Irish surgeon major stationed in Greece and his mother a Greek woman, famous for her beauty. It was she who named him Lafcadio, after Leudakia, the ancient name of Santa Maura, one of the islands connected with the legend of Sappho. In a relatively short lifespan of fifty-four years he managed to live several different literary lives.

Lafcadio Hearn was born on the Ionian island of Santa Maura in either June or August 1850 and died in Okubo, Japan in 1904. His father was an Irish surgeon major stationed in Greece and his mother a Greek woman, famous for her beauty. It was she who named him Lafcadio, after Leudakia, the ancient name of Santa Maura, one of the islands connected with the legend of Sappho. In a relatively short lifespan of fifty-four years he managed to live several different literary lives.  In spite of the incredible changes that have taken place in Japan since Hearn’s death in 1904, as an informant of Japanese life, literature, and religion he is still amazingly reliable, because beneath the effects of industrialization, war, population explosion, and prosperity much of Japanese life remains unchanged. For Hearn the old Japan — the art, traditions, and myths that had persisted for centuries — was the only Japan worth paying attention to. Two world wars and Japan’s astonishing emergence as a modern nation temporarily extinguished the credibility of Hearn’s vision of traditional Japanese culture. But both in the West and in Japan interest in the old forms of Japanese culture is increasing. In Tokyo there are still thousands of people living the old life by the traditional values alongside the most extreme effects of Westernization. Pet crickets, for example, still command high prices, and more people apply their new prosperity to learning tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arrangement and sumi-e painting than ever before. Ghost stories like those told by Hearn are popular on television; three of his own were recently combined to make a successful movie that preserves his title, Kwaidan.

In spite of the incredible changes that have taken place in Japan since Hearn’s death in 1904, as an informant of Japanese life, literature, and religion he is still amazingly reliable, because beneath the effects of industrialization, war, population explosion, and prosperity much of Japanese life remains unchanged. For Hearn the old Japan — the art, traditions, and myths that had persisted for centuries — was the only Japan worth paying attention to. Two world wars and Japan’s astonishing emergence as a modern nation temporarily extinguished the credibility of Hearn’s vision of traditional Japanese culture. But both in the West and in Japan interest in the old forms of Japanese culture is increasing. In Tokyo there are still thousands of people living the old life by the traditional values alongside the most extreme effects of Westernization. Pet crickets, for example, still command high prices, and more people apply their new prosperity to learning tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arrangement and sumi-e painting than ever before. Ghost stories like those told by Hearn are popular on television; three of his own were recently combined to make a successful movie that preserves his title, Kwaidan.  Buddha was born in Kapilavastu, now Rummimdei, Nepal, sometime around 563 BC and died about 483 BC in Kusimara, now Kasia, India. His personal name was Siddhartha Gautama. Buddha, The Enlightened One, is a title, not a name, as is Shakyamuni, the saint of the Shaka clan. In Japan, the historic Buddha is commonly known as Shakya. He was a member of the Kshatriya warrior caste, the son of the ruler of a small principality.

Buddha was born in Kapilavastu, now Rummimdei, Nepal, sometime around 563 BC and died about 483 BC in Kusimara, now Kasia, India. His personal name was Siddhartha Gautama. Buddha, The Enlightened One, is a title, not a name, as is Shakyamuni, the saint of the Shaka clan. In Japan, the historic Buddha is commonly known as Shakya. He was a member of the Kshatriya warrior caste, the son of the ruler of a small principality.  The story of the development of Mahayana as it spread from what is now Afghanistan and Russian Turkestan to Mongolia and Indonesia to Tibet, China and Japan, while it died out in India, would take many thousands of words to tell. There are traces of Buddhism in China two hundred years or more before the Christian era. Its official introduction is supposed to have occurred in the first century AD. From then until the Muslim conquest of India, Chinese pilgrims visited India and brought back caravan loads of statuaries and sutras (sacred texts) which were translated into Chinese.

The story of the development of Mahayana as it spread from what is now Afghanistan and Russian Turkestan to Mongolia and Indonesia to Tibet, China and Japan, while it died out in India, would take many thousands of words to tell. There are traces of Buddhism in China two hundred years or more before the Christian era. Its official introduction is supposed to have occurred in the first century AD. From then until the Muslim conquest of India, Chinese pilgrims visited India and brought back caravan loads of statuaries and sutras (sacred texts) which were translated into Chinese.

B

B

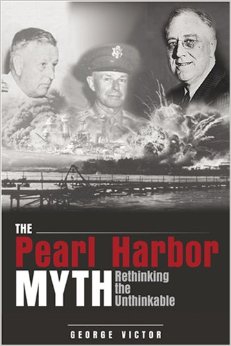

In this book, George Victor addresses the several questions regarding Pearl Harbor: did U.S. Intelligence know beforehand? Did Roosevelt know? If so, why weren’t commanders in Hawaii notified? It is a well-researched and documented volume, complete with hundreds of end-notes and references.

In this book, George Victor addresses the several questions regarding Pearl Harbor: did U.S. Intelligence know beforehand? Did Roosevelt know? If so, why weren’t commanders in Hawaii notified? It is a well-researched and documented volume, complete with hundreds of end-notes and references.